Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

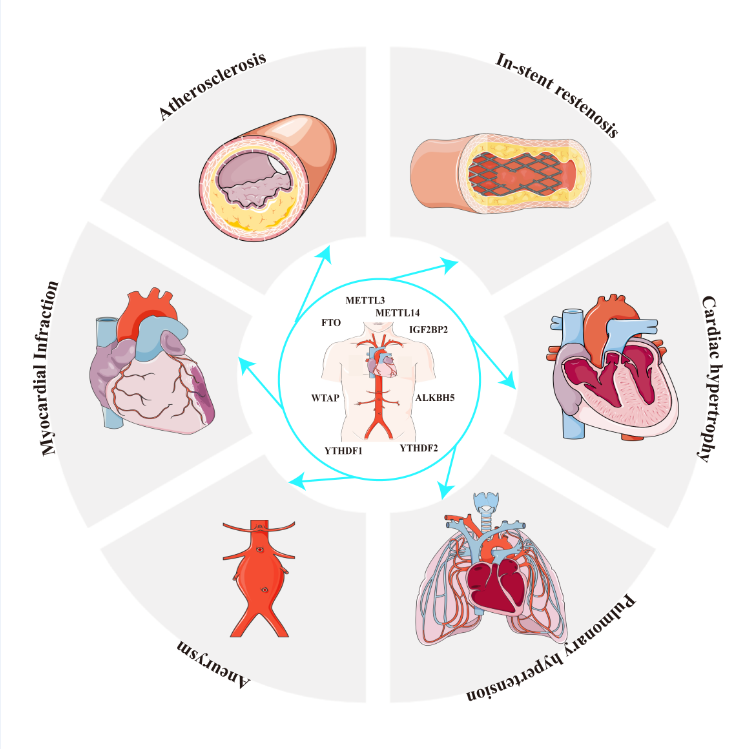

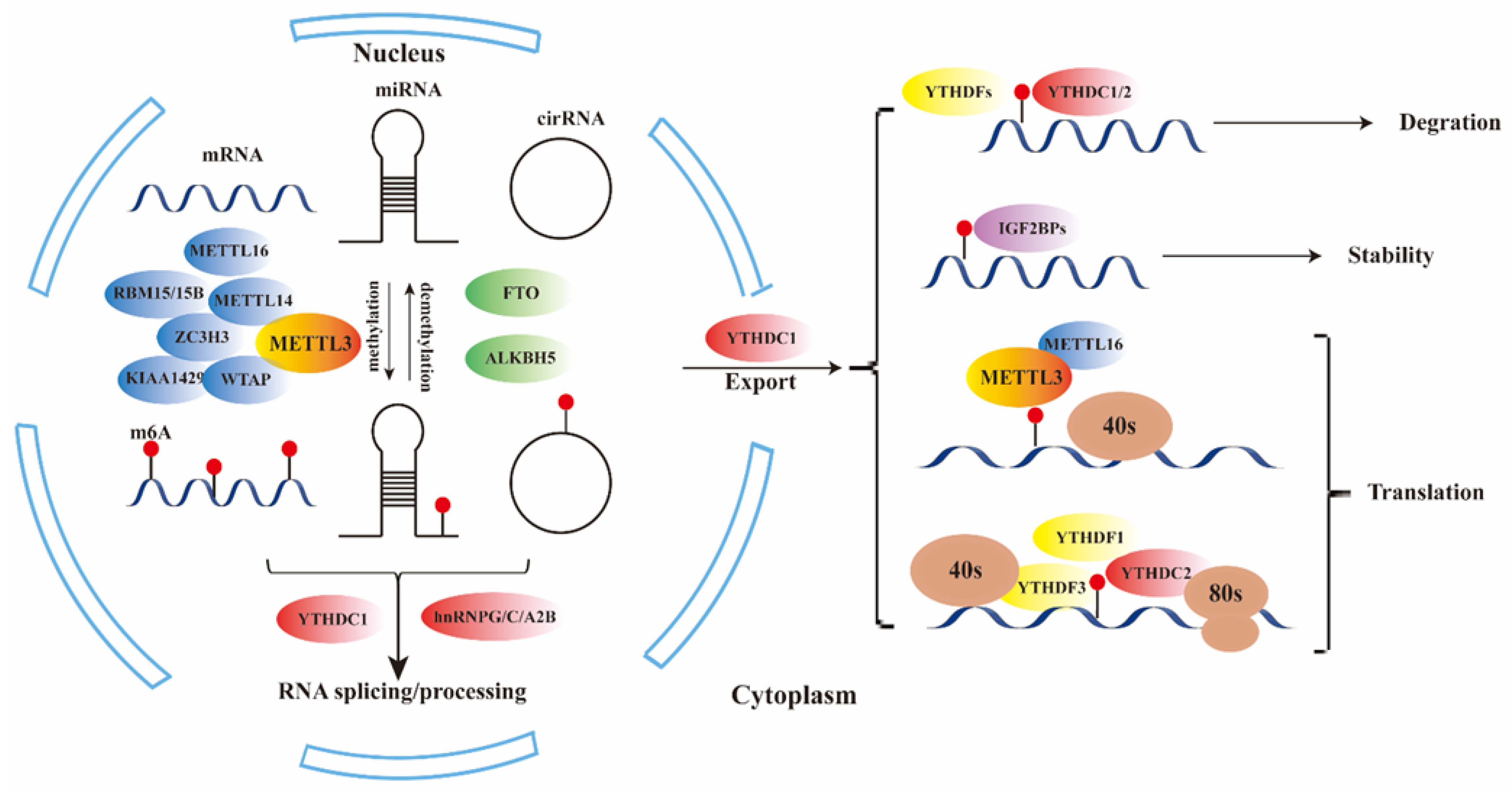

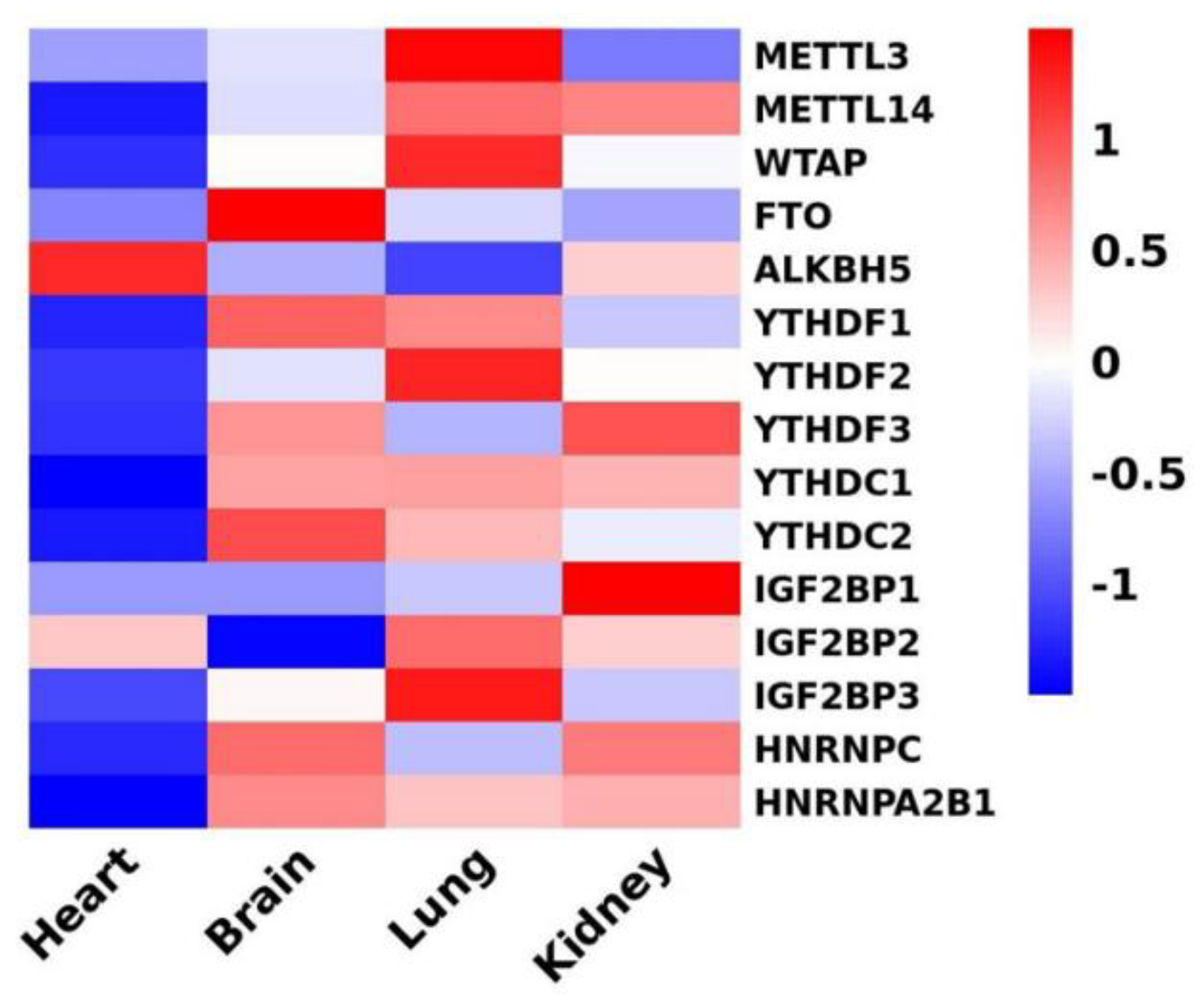

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most common and abundant internal co-transcriptional modification in eukaryotic RNAs. This modification is catalyzed by m6A methyltransferases, known as "writers," including METTL3/14 and WTAP, and removed by demethylases, or "erasers," such as FTO and ALKBH5. It is recognized by m6A-binding proteins, or "readers," such as YTHDF1/2/3, YTHDC1/2, IGF2BP1/2/3, and HNRNPA2B1. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Recent studies indicate that m6A RNA modification plays a critical role in both the physiological and pathological processes involved in the initiation and progression of CVDs. In this review, we will explore how m6A RNA methylation impacts both normal and disease states of the cardiovascular system. Our focus will be on recent advancements in understanding the biological functions, molecular mechanisms, and regulatory factors of m6A RNA methylation, along with its downstream target genes in various CVDs, such as atherosclerosis, ischemic diseases, metabolic disorders, and heart failure. We propose that the m6A RNA methylation pathway holds promise as a potential therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

3. Role of m6A in cardiovascular disease

3.1. Risk factors associated with CVDs

3.1.1. Glucose Metabolism

3.1.2. Adipogenesis and Obesity

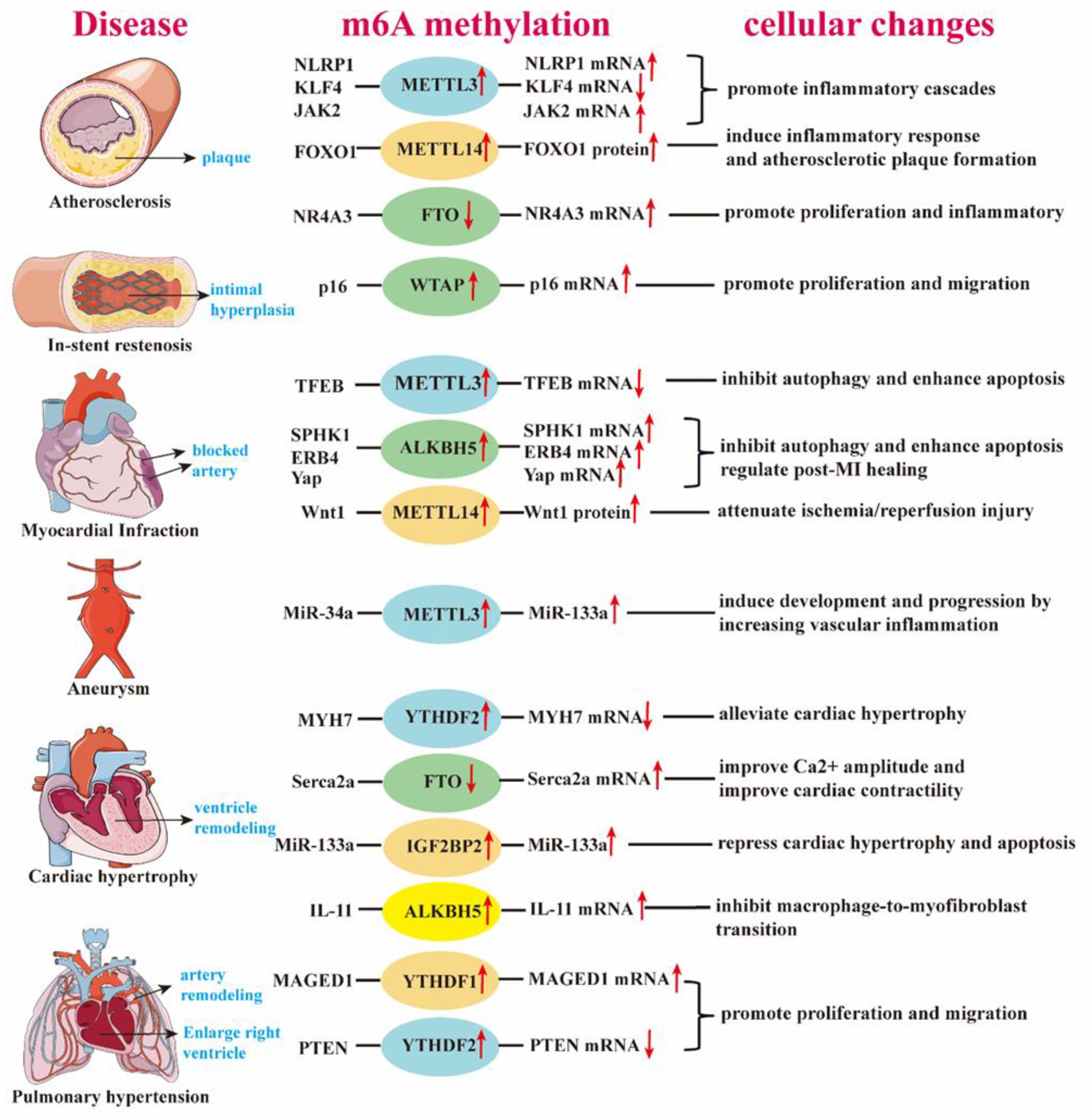

3.2. Function of m6a in CVDs

3.2.1. m6A and Ischemia/Hypoxia Injury

3.2.2. m6A and Atherosclerosis

3.2.2.1. m6A in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell (VSMC) Differentiation and Angiogenesis

3.2.2.2. m6A and Calcification

3.2.2.3. m6A in Atherosclerosis

3.2.3. m6A and Acute Myocardial Infarction

3.2.4. m6A and Heart Failure (HF)

3.2.5. m6a and other CVDs

4. Discussion

Funding

References

- Kottakis, F.; Nicolay, B.N.; Roumane, A.; Karnik, R.; Gu, H.; Nagle, J.M.; Boukhali, M.; Hayward, M.C.; Li, Y.Y.; Chen, T.; et al. LKB1 loss links serine metabolism to DNA methylation and tumorigenesis. Nature 2016, 539, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaccara, S.; Ries, R.J.; Jaffrey, S.R. Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 608–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hou, X.; Guan, Q.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, L.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Li, F.; Li, W.; Liu, H. RNA modification in cardiovascular disease: implications for therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motorin, Y.; Helm, M. RNA nucleotide methylation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2011, 2, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desrosiers, R.; Friderici, K.; Rottman, F. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1974, 71, 3971–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davalos, V.; Blanco, S.; Esteller, M. SnapShot: Messenger RNA Modifications. Cell 2018, 174, 498–498 e491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominissini, D.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Schwartz, S.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Ungar, L.; Osenberg, S.; Cesarkas, K.; Jacob-Hirsch, J.; Amariglio, N.; Kupiec, M.; et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 2012, 485, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wang, J.Z.; Yang, X.; Yu, H.; Zhou, R.; Lu, H.C.; Yuan, W.B.; Lu, J.C.; Zhou, Z.J.; Lu, Q.; et al. METTL3 promote tumor proliferation of bladder cancer by accelerating pri-miR221/222 maturation in m6A-dependent manner. Mol Cancer 2019, 18, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Molinie, B.; Daneshvar, K.; Pondick, J.V.; Wang, J.; Van Wittenberghe, N.; Xing, Y.; Giallourakis, C.C.; Mullen, A.C. Genome-Wide Maps of m6A circRNAs Identify Widespread and Cell-Type-Specific Methylation Patterns that Are Distinct from mRNAs. Cell Rep 2017, 20, 2262–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Qiao, J.; Wang, G.; Lan, Y.; Li, G.; Guo, X.; Xi, J.; Ye, D.; Zhu, S.; Chen, W.; et al. N6-Methyladenosine modification of lincRNA 1281 is critically required for mESC differentiation potential. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, 3906–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noale, M.; Limongi, F.; Maggi, S. Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Diseases in the Elderly. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020, 1216, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, K.D.; Saletore, Y.; Zumbo, P.; Elemento, O.; Mason, C.E.; Jaffrey, S.R. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3' UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 2012, 149, 1635–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Y.; Liu, J.; He, C. RNA N6-methyladenosine methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation. Genes Dev 2015, 29, 1343–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, K.D.; Jaffrey, S.R. Rethinking m(6)A Readers, Writers, and Erasers. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2017, 33, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; He, X.; Zhang, W.; Chu, D.; Feng, C. Alleviation Effect of Grape Seed Proanthocyanidins on Neuronal Apoptosis in Rats with Iron Overload. Biol Trace Elem Res 2020, 194, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yue, Y.; Han, D.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jia, G.; Yu, M.; Lu, Z.; Deng, X.; et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol 2014, 10, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ping, X.L.; Sun, B.F.; Wang, L.; Xiao, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.J.; Adhikari, S.; Shi, Y.; Lv, Y.; Chen, Y.S.; et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res 2014, 24, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.; Mumbach, M.R.; Jovanovic, M.; Wang, T.; Maciag, K.; Bushkin, G.G.; Mertins, P.; Ter-Ovanesyan, D.; Habib, N.; Cacchiarelli, D.; et al. Perturbation of m6A writers reveals two distinct classes of mRNA methylation at internal and 5' sites. Cell Rep 2014, 8, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, D.P.; Chen, C.K.; Pickering, B.F.; Chow, A.; Jackson, C.; Guttman, M.; Jaffrey, S.R. m(6)A RNA methylation promotes XIST-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature 2016, 537, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Lv, R.; Ma, H.; Shen, H.; He, C.; Wang, J.; Jiao, F.; Liu, H.; Yang, P.; Tan, L.; et al. Zc3h13 Regulates Nuclear RNA m(6)A Methylation and Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell Self-Renewal. Mol Cell 2018, 69, 1028–1038 e1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Liu, J.; Cui, X.; Cao, J.; Luo, G.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, T.; Gao, M.; Shu, X.; Ma, H.; et al. VIRMA mediates preferential m(6)A mRNA methylation in 3'UTR and near stop codon and associates with alternative polyadenylation. Cell Discov 2018, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Dai, Q.; Zheng, G.; Yang, Y.; Yi, C.; Lindahl, T.; Pan, T.; Yang, Y.G.; He, C. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol 2011, 7, 885–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, G.; Dahl, J.A.; Niu, Y.; Fedorcsak, P.; Huang, C.M.; Li, C.J.; Vagbo, C.B.; Shi, Y.; Wang, W.L.; Song, S.H.; et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell 2013, 49, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, B.S.; Roundtree, I.A.; Lu, Z.; Han, D.; Ma, H.; Weng, X.; Chen, K.; Shi, H.; He, C. N(6)-methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell 2015, 161, 1388–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Zhao, B.S.; Ma, H.; Hsu, P.J.; Liu, C.; He, C. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N(6)-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res 2017, 27, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Gomez, A.; Hon, G.C.; Yue, Y.; Han, D.; Fu, Y.; Parisien, M.; Dai, Q.; Jia, G.; et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 2014, 505, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roundtree, I.A.; Luo, G.Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, T.; Cui, Y.; Sha, J.; Huang, X.; Guerrero, L.; Xie, P.; et al. YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N(6)-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, P.J.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, H.; Guo, Y.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; Qi, M.; Lu, Z.; Shi, H.; Wang, J.; et al. Ythdc2 is an N(6)-methyladenosine binding protein that regulates mammalian spermatogenesis. Cell Res 2017, 27, 1115–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrauwe, N.; Suva, M.L.; Janiszewska, M.; Riggi, N.; Stamenkovic, I. IMPs: an RNA-binding protein family that provides a link between stem cell maintenance in normal development and cancer. Genes Dev 2016, 30, 2459–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Su, S.; Patil, D.P.; Liu, H.; Gan, J.; Jaffrey, S.R.; Ma, J. Molecular basis for the specific and multivariant recognitions of RNA substrates by human hnRNP A2/B1. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, K.; Song, B.; Ma, J.; Wu, X.; Xu, Q.; Wei, Z.; Su, J.; Liu, G.; Rong, R.; et al. m6A-Atlas: a comprehensive knowledgebase for unraveling the N6-methyladenosine (m6A) epitranscriptome. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, D134–D143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Gao, Y.; Jin, X.; Wang, H.; Lan, T.; Wei, M.; Yan, W.; Wang, G.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, X. Comprehensive analysis of N6-methylandenosine regulators and m6A-related RNAs as prognosis factors in colorectal cancer. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2022, 27, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Toth, J.I.; Petroski, M.D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.C. N6-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 2014, 16, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Adhikari, S.; Dahal, U.; Chen, Y.S.; Hao, Y.J.; Sun, B.F.; Sun, H.Y.; Li, A.; Ping, X.L.; Lai, W.Y.; et al. Nuclear m(6)A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Mol Cell 2016, 61, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Shen, F.; Huang, W.; Qin, S.; Huang, J.T.; Sergi, C.; Yuan, B.F.; Liu, S.M. Glucose Is Involved in the Dynamic Regulation of m6A in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019, 104, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jesus, D.F.; Zhang, Z.; Kahraman, S.; Brown, N.K.; Chen, M.; Hu, J.; Gupta, M.K.; He, C.; Kulkarni, R.N. m(6)A mRNA Methylation Regulates Human beta-Cell Biology in Physiological States and in Type 2 Diabetes. Nat Metab 2019, 1, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, N.; Biwer, L.A.; Good, M.E.; Ruddiman, C.A.; Wolpe, A.G.; DeLalio, L.J.; Murphy, S.; Macal, E.H., Jr.; Ragolia, L.; Serbulea, V.; et al. Loss of Endothelial FTO Antagonizes Obesity-Induced Metabolic and Vascular Dysfunction. Circ Res 2020, 126, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Guo, G.; Bi, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, N.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. m(6)A methylation modulates adipogenesis through JAK2-STAT3-C/EBPbeta signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 2019, 1862, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, B.F.; Shi, Y.; Yang, X.; Xiao, W.; Hao, Y.J.; Ping, X.L.; Chen, Y.S.; Wang, W.J.; et al. FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Res 2014, 24, 1403–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Bi, Z.; Yao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shi, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y. m(6)A mRNA methylation controls autophagy and adipogenesis by targeting Atg5 and Atg7. Autophagy 2020, 16, 1221–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Jiang, H.; Wu, J.; Cai, Y.; Dong, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, Q.; Hu, K.; Sun, A.; Ge, J. m6A demethylase FTO attenuates cardiac dysfunction by regulating glucose uptake and glycolysis in mice with pressure overload-induced heart failure. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birsoy, K.; Chen, Z.; Friedman, J. Transcriptional regulation of adipogenesis by KLF4. Cell Metab 2008, 7, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, T.; Yang, Y.; Wei, H.; Xie, X.; Lu, J.; Zeng, Q.; Peng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, S.; Peng, J. Zfp217 mediates m6A mRNA methylation to orchestrate transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation to promote adipogenic differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, 6130–6144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Han, D.; Liu, J.; Shi, J.; Zhu, P.; Wang, Y.; Dong, N. Factors influencing osteogenic differentiation of human aortic valve interstitial cells. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021, 161, e163–e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Ning, Y.; Zhang, H.; Song, N.; Gu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Cai, J.; Ding, X.; Zhang, X. METTL14-dependent m6A regulates vascular calcification induced by indoxyl sulfate. Life Sci 2019, 239, 117034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Feng, X.; Zhang, H.; Luo, Y.; Huang, J.; Lin, M.; Jin, J.; Ding, X.; Wu, S.; Huang, H.; et al. METTL3 and ALKBH5 oppositely regulate m(6)A modification of TFEB mRNA, which dictates the fate of hypoxia/reoxygenation-treated cardiomyocytes. Autophagy 2019, 15, 1419–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Dutta, R.; Ranjan, P.; Suleiman, Z.G.; Goswami, S.K.; Li, J.; Pal, H.C.; Verma, S.K. ALKBH5 Regulates SPHK1-Dependent Endothelial Cell Angiogenesis Following Ischemic Stress. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 817304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Gong, R.; Yu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, S.; Yu, M.; et al. ALKBH5 regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration by demethylating the mRNA of YTHDF1. Theranostics 2021, 11, 3000–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Hu, J.; Sun, X.; Yang, K.; Yang, L.; Kong, L.; Zhang, B.; Li, F.; Li, C.; Shi, B.; et al. Loss of m6A demethylase ALKBH5 promotes post-ischemic angiogenesis via post-transcriptional stabilization of WNT5A. Clin Transl Med 2021, 11, e402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Li, H.; Su, H.; Chen, K.; Yan, J. FTO overexpression inhibits apoptosis of hypoxia/reoxygenation-treated myocardial cells by regulating m6A modification of Mhrt. Mol Cell Biochem 2021, 476, 2171–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, T.; Wang, N.; Jia, F.; Wu, Y.; Gao, L.; Zhang, J.; Hou, R. Exosome-based WTAP siRNA delivery ameliorates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2024, 197, 114218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, C.S.; Li, J.Y.; Chien, Y.; Wang, M.L.; Yarmishyn, A.A.; Tsai, P.H.; Juan, C.C.; Nguyen, P.; Cheng, H.M.; Huo, T.I.; et al. METTL3-dependent N(6)-methyladenosine RNA modification mediates the atherogenic inflammatory cascades in vascular endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, D.; Wang, Y.; Jian, L.; Tang, H.; Rao, L.; Chen, K.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. METTL14 aggravates endothelial inflammation and atherosclerosis by increasing FOXO1 N6-methyladeosine modifications. Theranostics 2020, 10, 8939–8956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, G.; Yu, J.; Shan, G.; Su, L.; Yu, N.; Yang, S. N6-Methyladenosine Methyltransferase METTL3 Promotes Angiogenesis and Atherosclerosis by Upregulating the JAK2/STAT3 Pathway via m6A Reader IGF2BP1. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 731810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.Y.; Han, L.; Tang, Y.F.; Zhang, G.X.; Fan, X.L.; Zhang, J.J.; Xue, Q.; Xu, Z.Y. METTL14 regulates M6A methylation-modified primary miR-19a to promote cardiovascular endothelial cell proliferation and invasion. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020, 24, 7015–7023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, Y.B.; Gao, X.; Peng, Q.; Nie, Q.; Bi, W. Dihydroartemisinin alleviates AngII-induced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and inflammatory response by blocking the FTO/NR4A3 axis. Inflamm Res 2022, 71, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Gong, Y.; Shen, L.; Li, J.; Han, J.; Song, B.; Hu, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z. Total Panax notoginseng saponin inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration and intimal hyperplasia by regulating WTAP/p16 signals via m(6)A modulation. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 124, 109935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, R.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, Y.; Han, Z.; Yu, Y.; Dong, C.; et al. Loss of m(6)A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes heart regeneration and repair after myocardial injury. Pharmacol Res 2021, 174, 105845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, P.; Han, H.; Chen, F.; Cheng, L.; Ma, C.; Huang, H.; Chen, C.; Li, H.; Cai, H.; Huang, H.; et al. Amelioration of acute myocardial infarction injury through targeted ferritin nanocages loaded with an ALKBH5 inhibitor. Acta Biomater 2022, 140, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, J.; Gao, R.; Shi, J.; Wei, X.; Chen, J.; Hu, K.; Sun, A.; Ge, J. ALKBH5 induces fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transformation during hypoxia to protect against cardiac rupture after myocardial infarction. J Adv Res 2024, 61, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, P.; Qu, Z.; Yu, S.; Pang, X.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, K.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Bian, Y.; et al. Mettl14 Attenuates Cardiac Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Regulating Wnt1/beta-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 762853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiyalagan, P.; Adamiak, M.; Mayourian, J.; Sassi, Y.; Liang, Y.; Agarwal, N.; Jha, D.; Zhang, S.; Kohlbrenner, E.; Chepurko, E.; et al. FTO-Dependent N(6)-Methyladenosine Regulates Cardiac Function During Remodeling and Repair. Circulation 2019, 139, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhao, W.; Tao, T.; Ma, L.; Ni, Y.; Li, W. YTHDF2 alleviates cardiac hypertrophy via regulating Myh7 mRNA decoy. Cell Biosci 2021, 11, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, B.; Wang, P.; Zhang, D.; Wu, L. m6A modification promotes miR-133a repression during cardiac development and hypertrophy via IGF2BP2. Cell Death Discov 2021, 7, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Chen, M.H.; Wu, R.X.; Wang, J.; Hu, X.D.; Meng, T.; Wu, A.H.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.F.; Lei, Y.; et al. ALKBH5-mediated m6A modification of IL-11 drives macrophage-to-myofibroblast transition and pathological cardiac fibrosis in mice. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Li, L.; Luo, E.; Wang, D.; Yao, Y.; Tang, C.; Yan, G. The m(6)A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes hypoxic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Life Sci 2021, 274, 119366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wang, J.; Huang, H.; Yu, Y.; Ding, J.; Yu, Y.; Li, K.; Wei, D.; Ye, Q.; Wang, F.; et al. YTHDF1 Regulates Pulmonary Hypertension through Translational Control of MAGED1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021, 203, 1158–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.; He, X.; Song, H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, G.; Si, X.; Sun, J.; Chen, X.; Liao, W.; Liao, Y.; Bin, J. METTL3 Induces AAA Development and Progression by Modulating N6-Methyladenosine-Dependent Primary miR34a Processing. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2020, 21, 394–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Wang, F. Mechanism of METTL3-Mediated m(6)A Modification in Cardiomyocyte Pyroptosis and Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2023, 37, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroemer, G. Autophagy: a druggable process that is deregulated in aging and human disease. J Clin Invest 2015, 125, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zhang, X.; Miao, Y.; Liang, P.; Zhu, K.; She, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, D.A.; Huang, J.; Ren, J.; Cui, J. m(6)A RNA modification controls autophagy through upregulating ULK1 protein abundance. Cell Res 2018, 28, 955–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frismantiene, A.; Philippova, M.; Erne, P.; Resink, T.J. Smooth muscle cell-driven vascular diseases and molecular mechanisms of VSMC plasticity. Cell Signal 2018, 52, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Zhu, Q.; Huang, J.; Cai, R.; Kuang, Y. Hypoxia Promotes Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell (VSMC) Differentiation of Adipose-Derived Stem Cell (ADSC) by Regulating Mettl3 and Paracrine Factors. Stem Cells Int 2020, 2020, 2830565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Xue, Y.; Lu, Z.; Gan, J. YTHDC2-Mediated circYTHDC2 N6-Methyladenosine Modification Promotes Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Dysfunction Through Inhibiting Ten-Eleven Translocation 2. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 686293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parial, R.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Archacki, S.; Yang, Z.; Wang, I.Z.; Chen, Q.; Xu, C.; Wang, Q.K. Role of epigenetic m(6) A RNA methylation in vascular development: mettl3 regulates vascular development through PHLPP2/mTOR-AKT signaling. FASEB J 2021, 35, e21465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.D.; Jiang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhu, C.Y.; Sun, Y.N.; Shan, K.; Ge, H.M.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Zhang, H.Y.; et al. Role of METTL3-Dependent N(6)-Methyladenosine mRNA Modification in the Promotion of Angiogenesis. Mol Ther 2020, 28, 2191–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geovanini, G.R.; Libby, P. Atherosclerosis and inflammation: overview and updates. Clin Sci (Lond) 2018, 132, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J.J.; Chien, S. Effects of disturbed flow on vascular endothelium: pathophysiological basis and clinical perspectives. Physiol Rev 2011, 91, 327–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miano, J.M.; Fisher, E.A.; Majesky, M.W. Fate and State of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Atherosclerosis. Circulation 2021, 143, 2110–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapouri-Moghaddam, A.; Mohammadian, S.; Vazini, H.; Taghadosi, M.; Esmaeili, S.A.; Mardani, F.; Seifi, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Afshari, J.T.; Sahebkar, A. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233, 6425–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tang, H.; Shen, Y.; Gong, Z.; Xie, N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Kong, W.; Zhou, Y.; Fu, Y. The N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A)-forming enzyme METTL3 facilitates M1 macrophage polarization through the methylation of STAT1 mRNA. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2019, 317, C762–C775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Hu, X.; Huang, M.; Liu, J.; Gu, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhou, Q.; Cao, X. Mettl3-mediated mRNA m(6)A methylation promotes dendritic cell activation. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Gan, X.; Jiang, X.; Diao, S.; Wu, H.; Hu, J. ALKBH5 inhibited autophagy of epithelial ovarian cancer through miR-7 and BCL-2. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2019, 38, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Writing Committee, M.; Yancy, C.W.; Jessup, M.; Bozkurt, B.; Butler, J.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Drazner, M.H.; Fonarow, G.C.; Geraci, S.A.; Horwich, T.; et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2013, 128, e240–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, V.L.; Weston, S.A.; Redfield, M.M.; Hellermann-Homan, J.P.; Killian, J.; Yawn, B.P.; Jacobsen, S.J. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA 2004, 292, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xu, Y.; Cui, X.; Jiang, H.; Luo, W.; Weng, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, A.; Ge, J. Alteration of m6A RNA Methylation in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 647806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berulava, T.; Buchholz, E.; Elerdashvili, V.; Pena, T.; Islam, M.R.; Lbik, D.; Mohamed, B.A.; Renner, A.; von Lewinski, D.; Sacherer, M.; et al. Changes in m6A RNA methylation contribute to heart failure progression by modulating translation. Eur J Heart Fail 2020, 22, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinger, S.A.; Wei, J.; Dorn, L.E.; Whitson, B.A.; Janssen, P.M.L.; He, C.; Accornero, F. Remodeling of the m(6)A landscape in the heart reveals few conserved post-transcriptional events underlying cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2021, 151, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhuang, Y.; Yang, W.; Xie, Y.; Shang, W.; Su, S.; Dong, X.; Wu, J.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Silencing of METTL3 attenuates cardiac fibrosis induced by myocardial infarction via inhibiting the activation of cardiac fibroblasts. FASEB J 2021, 35, e21162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Deng, J.; Zhou, Q.; Hu, Z.; Yang, L. Maslinic acid protects against pressure-overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy by blocking METTL3-mediated m(6)A methylation. Aging (Albany NY) 2022, 14, 2548–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, L.E.; Lasman, L.; Chen, J.; Xu, X.; Hund, T.J.; Medvedovic, M.; Hanna, J.H.; van Berlo, J.H.; Accornero, F. The N(6)-Methyladenosine mRNA Methylase METTL3 Controls Cardiac Homeostasis and Hypertrophy. Circulation 2019, 139, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmietczyk, V.; Riechert, E.; Kalinski, L.; Boileau, E.; Malovrh, E.; Malone, B.; Gorska, A.; Hofmann, C.; Varma, E.; Jurgensen, L.; et al. m(6)A-mRNA methylation regulates cardiac gene expression and cellular growth. Life Sci Alliance 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Hu, Y.; Hou, L.; Ju, J.; Li, X.; Du, N.; Guan, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Qin, W.; et al. beta-Blocker carvedilol protects cardiomyocytes against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis by up-regulating miR-133 expression. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2014, 75, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Bezprozvannaya, S.; Williams, A.H.; Qi, X.; Richardson, J.A.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. microRNA-133a regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and suppresses smooth muscle gene expression in the heart. Genes Dev 2008, 22, 3242–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcadenti, A.; Fuchs, F.D.; Matte, U.; Sperb, F.; Moreira, L.B.; Fuchs, S.C. Effects of FTO RS9939906 and MC4R RS17782313 on obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus and blood pressure in patients with hypertension. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2013, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, X.B.; Lei, S.F.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhang, H. Examination of the associations between m(6)A-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms and blood pressure. Hypertens Res 2019, 42, 1582–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wang, G.; Wu, L.; Ma, X.; Ying, K.; Zhang, R. Transcriptome-wide map of m(6)A circRNAs identified in a rat model of hypoxia mediated pulmonary hypertension. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhao, J.J.; Xiong, Y.J.; Chang, Q.; Wang, H.Y.; Su, P.; Meng, J.; Zhao, Y.B. Vascular Smooth Muscle FTO Promotes Aortic Dissecting Aneurysms via m6A Modification of Klf5. Front Cardiovasc Med 2020, 7, 592550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Jing, J.; Ma, C.; Sun, L. N6-methyladenosine-associated genetic variants in NECTIN2 and HPCAL1 are risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm. iScience 2024, 27, 109419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| type | regulator | Function of RNA modification | reference |

| writers | METTL3 | main catalytic subunit of m6A | [16] |

| METTL14/16 | activate METTL3 through allosteric and RNA substrate recognition | [16] | |

| WTAP | the third subunit of METTL3-METTL14 complex | [17,18] | |

| ZC3H3 | assist the localization of the methyltransferase complex in nuclear speckles and U-rich regions adjacent to the m6A sites in mRNAs | [19] | |

| RBM15/15B | [20] | ||

| KIAA1429 | [21] | ||

| erasers | FTO | demethylation of m6a | [2,22,23] |

| ALKBH5 | |||

| readers | YTHDF1 | promote mRNA translation | [24,25] |

| YTHDF2 | accelerates the decay of m6A-modified transcripts | ||

| YTHDF3 | promote mRNA translation or enhance RNA decay | ||

| YTHDC1 | promote mRNA translation and splicing and nuclear export | [26,27] | |

| YTHDC2 | enhance translation | [28] | |

| IGF2BP1/2/3 | regulate RNA localization, translation, and stability | [29] | |

| hnRNPG/C/A2B | Promote RNA stability and mediate RNA splicing and microRNA process | [30] |

| Risk factors | regulators | Cell | Regulation | signaling | function | reference |

| Glucose metabolism | FTO↑ | hepatoellular cell | up-regulate mRNA |

FOXO1/FASN/ G6PC/ DGAT2 |

improve the production of serum glucose and lipids | [35] |

|

diabetes |

METTL14↓ | β-cell | promote mRNA translation | AKT/ PDX1 | induce cell-cycle arrest and impair insulin secretion | [36] |

| obesity | FTO↑ | endothelial cell | down-regulate mRNA | AKT/ prostaglandinD2 |

aggravate vascular dysfunction | [37] |

| FTO↑ | preadipocyte | up-regulate mRNA | JAK2-STAT3-C/EBPβ | promote adipogenesis | [38] | |

| FTO↑ | preadipocyte | control exonic splicing | RUNX1T1 | modulate differentiation to promote adipogenesis | [39] | |

| FTO↑ | preadipocytes | improve mRNA stability | Atg5/Atg7 | promote autophagy and adipogenesis | [40] |

| Diseases | regulators | Cell | Regulation | signaling | function | reference |

| calcification | METTL3↑ | valve interstitial cell | up-regulate mRNA | TWIST1 | promote osteogenic differentiation process | [44] |

| calcification | METTL14↑ | smooth muscle cell | down-regulate mRNA | Klotho | promote calcification | [45] |

| hypoxia/reoxygenation | METTL3↑ | cardiomyocyte | down-regulate mRNA | TFEB | inhibit autophagy and enhance apoptosis | [46] |

| ischemic injury | ALKBH5↑ | endothelial cell | up-regulate mRNA | SPHK1/eNOS-AKT | maintain angiogenesis | [47] |

| heart regeneration | ALKBH5↑ | cardiomyocyte | improve mRNA stability | YAP | promote proliferation | [48] |

| post-ischemic | ALKBH5↑ | endothelial cell | decrease mRNA stability | WNT5A | exacerbate dysfunction of CMECs | [49] |

| hypoxia/reoxygenation | FTO↑ | cardiomyocyte | up-regulate mRNA | Mhrt | inhibit apoptosis | [50] |

| hypoxia/reoxygenation | WTAP↑ | cardiomyocyte | up-regulate mRNA | TXNIP | enhance apoptosis | [51] |

| atherosclerosis | METTL3↑ | endothelial cell | up/down-regulate mRNA | NLRP1/KLF4 | promote inflammatory cascades | [52] |

| atherosclerosis | METTL14↑ | endothelial cell | promote translation | FOXO1/VCAM-1/ICAM-1 | induce inflammatory response and promote atherosclerotic plaque formation | [53] |

| atherosclerosis | METTL3↑ | endothelial cell | up-regulate mRNA |

JAK2/STAT3 |

promote atherosclerosis progression | [54] |

| atherosclerosis | METTL14↑ | endothelial cell | up-regulate miRNA |

pri-miR-19a /DGCR8 |

promote proliferation and invasion of ASVEC | [55] |

| atherosclerosis | FTO↓ | smooth muscle cell | up-regulate mRNA | NR4A3 | promote proliferation and inflammatory | [56] |

| intimal hyperplasia | WTAP↓ | smooth muscle cell | up-regulate mRNA | p16 | promote proliferation and migration of VSMC | [57] |

| heart regeneration | METTL3↓ | cardiomyocyte | up-regulate miRNA |

miR-143 /Yap/Ctnnd1 |

Inhibit heart regeneration | [58] |

| AML | ALKBH5↑ | cardiomyocyte | not mention | TCA cycle | affect cell metabolism and survival | [59] |

| AML | ALKBH5↑ | fibroblast | improve mRNA stability | ErbB4 | regulate post-MI healing | [60] |

| ischemia/reperfusion Injury | METTL14↑ | cardiomyocyte | promote translation efficiency | Wnt1 | attenuate ischemia/reperfusion Injury | [61] |

| Heart failure | FTO↓ | cardiomyocyte | improve mRNA stability | Serca2a | improve Ca2+ amplitude | [62] |

| Heart failure | YTHDF2↑ | cardiomyocyte | promote mRNA degradation |

Myh7 | alleviate cardiac hypertrophy | [63] |

| Heart failure | IGF2BP2↑ | cardiomyocyte | promote miRNA accumulation on its target site | miR-133a | repress cardiac hypertrophy and apoptosis | [64] |

| Heart failure | FTO↓ | cardiomyocytes | improve mRNA stability | Pgam2 | regulating glucose uptake | [41] |

| Heart failure | ALKBH5↑ | macrophage | improve mRNA stability | IL-11 | Inhibit macrophage-to-myofibroblast transition | [65] |

| pulmonary hypertension | YTHDF2↑ | smooth muscle cell | promote mRNA degradation |

PTEN /PI3K/Akt | enhance proliferation | [66] |

| pulmonary hypertension | YTHDF1↑ | smooth muscle cell | promote translation efficiency | MAGED1 | promote proliferation | [67] |

| aneurysm | METTL3↑ | smooth muscle cell | up-regulate miRNA | DGCR8/ miR-34a |

induce development and progression | [68] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).