1. Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF), a prevalent supraventricular tachyarrhythmia, is responsible for one-third of hospitalizations due to arrhythmic diseases [

1]. While hypertensive heart disease, coronary artery disease, and rheumatic heart disease are often found in AF patients, obesity has recently become a pervasive issue. Nearly one in seven people have a body mass index (BMI) exceeding 30 kg/m2, placing them at risk for numerous cardiac diseases, including AF [

2,

3]. A 5-unit increase in BMI leads to an additional risk of AF of up to 29% [

4], with obesity being a factor in 20% of AF cases [

5]. Obesity is linked with mortality, hospitalization, heart failure, and thromboembolic events.

Most AF patients undergo long-term oral anticoagulation to minimize the threat of ischemic stroke and other embolic events. Recently, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) demonstrated equal or superior efficacy to warfarin due to their specific modes of action, including selective factor Xa inhibitors and direct thrombin/factor IIa inhibitors [

6]. However, DOAC use is limited or prohibited in certain scenarios such as mechanical mitral valve irregularities, end-stage renal disease [

7], and conditions that increase prothrombotic states like obesity. Obesity can influence the clinical pharmacology of anticoagulants, leading to heightened thrombotic risk or bleeding incidents. In 2016, the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) suggested avoiding the use of DOACs in obese or overweight patients unless drug levels are monitored [

8].

There is insufficient data on the efficacy and safety of DOACs in obese patients. Our research seeks to address this knowledge gap by comparing the clinical efficacy and safety of DOACs and warfarin in obese adults diagnosed with AF or Venous Thromboembolism (VTE).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Settings

This retrospective cohort study involved patients with a BMI exceeding 30 kg/m2 who were diagnosed with AF or VTE. These patients were started on either DOACs or warfarin to prevent thromboembolic events in both inpatient and outpatient settings. The study took place from January 2015 to December 2021 at King Abdulaziz Medical City, a tertiary care centre under the Ministry of National Guard-Health Affairs (MNGHA) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The research received approval from the Institutional Review Board at the joint institution, the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, with approval number RC22R/130/02.

2.2. Identification of Study Participants

We included patients over 18 years of age with a BMI exceeding 30 kg/m2 who were diagnosed with atrial AF or VTE and initiated on direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) or warfarin. The AF or VTE diagnosis was identified by the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, and Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes: I48.0, I48.1, I48.2, and I48.9 for AF and I26.0, I80.x, I82.x, and T81.72 for VTE. The first appointment following medication initiation was deemed the index visit. We excluded patients with mechanical valves, valvular AF, left ventricular clots, or severe heart failure with an ejection fraction below 30%. We used a non-probability consecutive technique to sample the target population. Patients were sorted into categories based on the type of oral anticoagulant prescribed: DOACs (including dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban) or warfarin. They were further stratified into three BMI groups: group 1 (30 to <35 kg/m2), group 2 (35 to <40 kg/m2), and group 3 (40 kg/m2 or greater).

2.3. Data Collection and Study Outcomes

We collected demographic, clinical, and outcome data for all patients from electronic medical records, encompassing inpatient, outpatient, and emergency department visits. Information on patient comorbidities, such as chronic kidney disease, stroke history, and cancer, as well as concurrent medications like antiplatelets and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), were noted to evaluate their influence on clinical outcomes. All data were obtained from Electronic Health Records, and patients were monitored until their last follow-up in December 2022.

The primary outcomes evaluated were incidences of stroke, recurrence of VTE, and all-cause mortality. The secondary outcomes assessed for safety were major or minor bleeding events defined by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) criteria, emergency department visits, and transfusions.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Patients were divided into two groups; DOACs and warfarin. To adjust for the influence of differences in the patients' baseline characteristics and comorbidities on the study outcomes, propensity score matching technique was used. A propensity score for each patient was generated using a logistic regression model predicting treatment received on the demographic, clinical, and procedural characteristics. We matched patients on DOACs with warfarin by performing a 1:1 nearest neighbor match with a caliper width of 0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score. For continuous variables, results were presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile), and categorical variables were shown as frequencies and percentages. The study groups were compared using chi-square or fisher exact test for categorical variables and Student's t-test or Wilcoxon rank as appropriate before and after matching. Hazard ratios were calculated using Cox proportional hazard models. Stepwise models were generated as follow: model 1: unadjusted, model 2: adjusted for age, gender and BMI category, model 3: adjusted for age, gender, BMI continuous, and model 4: adjusted for age, gender, BMI continuous, risk factors (Chronic Kidney Disease, Cancer, hypertension, previous history of venous thromboembolism). Time-to-event curves were generated using Kaplan-Meier methods and compared with the log-rank test for different study outcomes including: bleeding, mortality, stroke and VTE. A 2-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was the determination of statistical significance in baseline comparisons. Statistical analyses were conducted on Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) and match it package.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

The study included 959 patients (median age 76.0 (66.0, 84.0) years; 65% were females) diagnosed with AF or VTE, treated with either DOAC (apixaban, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban) or warfarin. The average CHA2DS2VASc score was 4.9 ± 1.97, the median BMI was 33.3 (31.0, 37.5) kg/m2, and 95% were AF patients. The majority (61.9%) had a BMI ranging from 30 to <35, while 21.6% had a BMI between 35 and <40, and only 16.5% had a BMI over 40 kg/m2. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors like hypertension (77.9%), diabetes (65.0%), and dyslipidemia (47.4%) were prevalent in the cohort. DOACs were administered to 519 (54.1%) patients during the study, while the rest, 440 (45.9%), received warfarin. In the DOAC group, apixaban was the most used drug (480 patients, 92.5%), followed by dabigatran (32 patients, 6.2%) and rivaroxaban (7 patients, 1.3%).

Table 1 presents the baseline clinical characteristics of the cohort, stratified by the anticoagulant used.

3.2. Propensity Matching

We utilized 1:1 propensity matching to adjust for discrepancies between the two groups, resulting in a final sample of 850 patients. After matching, the median ages between groups were comparable. The DOAC group consisted of 64.2% females, while the warfarin group constituted 62.8% females. The BMI distribution also showed similarity post-matching; the median BMI was 33.2 (31.1, 37.7) and 32.9 (30.8, 36.7) for the DOACs and warfarin groups, respectively. All factors, including risk factors, past medical history (with the exception of previous cardiac catheterization), and use of evidence-based medication, showed robust matching with hardly any significant remaining differences between the two groups. The incidence rates of stroke, VTE, and bleeding were found to be 4.5%, 2.5%, and 5.5% respectively (

Table 2).

3.3. Safety and Efficacy of DOAC

After a median follow-up of 1.3 years (interquartile 0.6–2.3 years), 230 deaths were recorded. Of these, 90 out of 425 deaths (21.2%) were in the DOAC group, versus 140 out of 425 patients (32.9%) in the warfarin group. The rate of stroke, VTE and bleeding was not statistically significant in between the groups as shown in

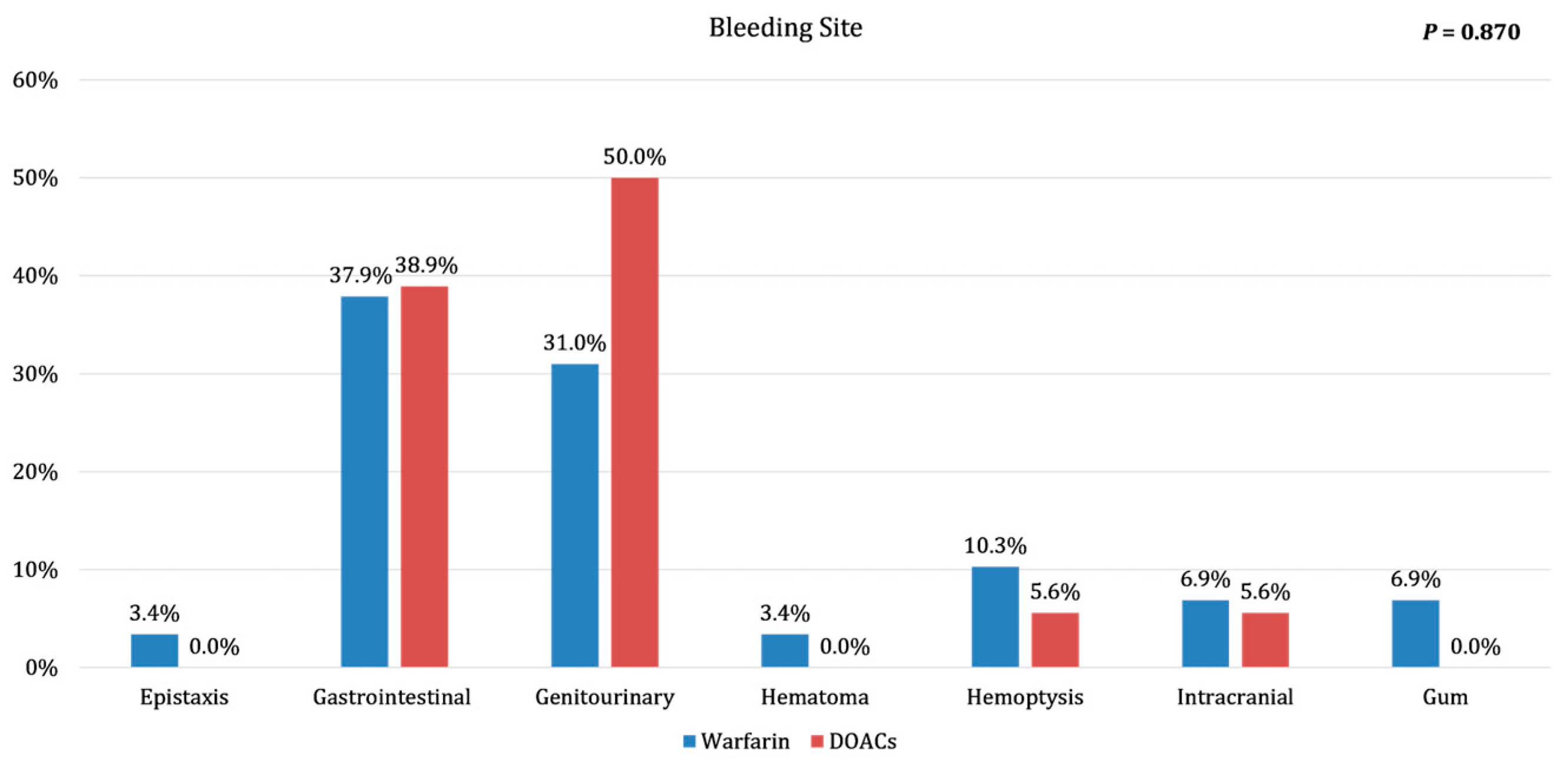

Table 2. Although there was a trend to a lower bleeding rate in DOACs group. The locations of bleeding instances are detailed in

Figure 1.

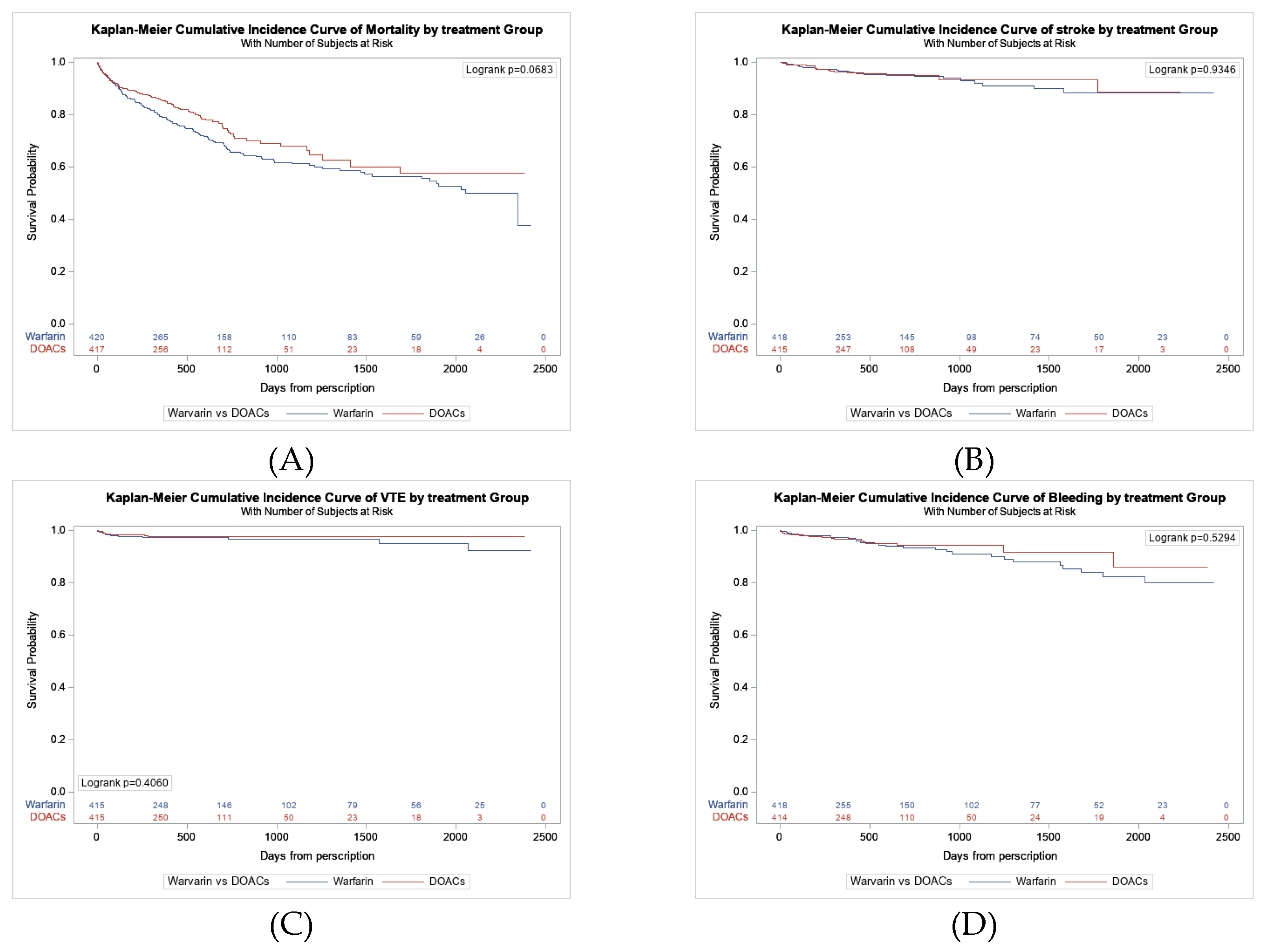

Figure 2A presents the Kaplan-Meier survival curves, which show that DOAC was linked to a lower risk of mortality than warfarin, with an unadjusted hazard ratio of 0.780 (95% CI: 0.60–1.02; p=0.069). The lower mortality risk associated with DOAC persisted after adjusting for the propensity score and several other risk factors, although the results were statistically insignificant (

Table 3). When examining different safety outcomes such as stroke, VTE, and bleeding, Kaplan-Meier survival curves indicated no difference between DOAC and warfarin (

Figure 2B, C, and D).

4. Discussion

Direct oral anticoagulants offer significant advantages over warfarin, simplifying the choice for many patients. However, they are not as beneficial for a considerable number of AF patients - particularly those with a high BMI - who face an increased risk of adverse thromboembolic events and are often overlooked in existing research studies. Our analysis of real-world data revealed that obese AF patients on direct oral anticoagulants had a lower overall incidence of efficacy and safety outcomes compared to those on warfarin. Notably, these patients demonstrated significantly reduced all-cause mortality rates, and this trend persisted even after PSM and adjusting for known confounders.

VTE and Stroke Literature of DOACs vs. Warfarin in Obesity

Our results align with those of Perales et al., who found similar rates of stroke, VTE recurrence, and mortality in morbidly obese patients using rivaroxaban and warfarin

[9]. Similar findings were reported by Coons et al., who found no significant variance in VTE recurrence between DOACs and warfarin in a comprehensive clinical study

[10]. In a study using an ICD code for morbid obesity, comparable VTE recurrence rates were observed for DOACs and warfarin

[11]. Aloi KG (2021), a retrospective analysis of patients with VTE treated in the Veterans Integrated Service Network showed that those weighing ≥120 kg and treated with DOACs had a higher, but statistically insignificant, VTE recurrence than those weighing <120 kg

[12].

A retrospective cohort study done by Barakat AF. Et al. demonstrated that DOAC patients in all BMI categories, including underweight and obese, had a significantly lower risk of both types of strokes. Notably, this study also revealed that DOAC patients with BMIs of 40 or higher had a 25% and 50% reduced risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, respectively. It is worth noting that this study used ICD 9 and ICD 10 codes to identify outcomes in a large US hospital system, whereas we derived our outcomes from a thorough review of each patient’s Electronic Medical Record

[13].

A retrospective clinical study done by Kushnir M. et al. highlighted that morbidly obese DOAC patients, including those with a BMI over 50 kg/m², exhibited stroke, recurrent venous thromboembolism, and major bleeding rates comparable to those on warfarin

[14].

The recent ISTH SSC Subcommittee and Expert Consensus Panel updates on DOACs in obese VTE patients highlighted the need for clearer therapeutic targets, noting that efficacy gaps persist, especially in severe obesity and post-bariatric surgery. Indeed, it looks mostly at VTE treatment and prevention but not including Atrial fibrillation group. Despite the 2021 removal of BMI limitations, which had previously advised against DOAC use in patients with severe obesity, hesitancy remains among healthcare providers due to limited data on efficacy and safety in high-BMI populations. These findings underscore the importance of our real-world investigation into DOAC outcomes in obese VTE and AF patients, broadening insights into treatment efficacy in high-risk populations. [

15,

16]

Bleeding Literature of DOACs vs. Warfarin in Obesity

Coons et al. found no significant discrepancy in major bleeding incidence rates between DOACs and warfarin, aligning with our results [

10]. Several other studies also noted that DOACs had a lower association with bleeding events [

11,

13]. Barakat et al. observed a strong trend towards lower risks of bleeding events with DOAC usage, although this did not achieve statistical significance. Their research also revealed a reduction in bleeding risk by about 60% in morbidly obese patients on DOACs [

13]. Interestingly, genitourinary bleeding was seen more commonly among DOAC-treated patients, whereas gastrointestinal bleeding occurred more frequently in warfarin-treated patients [

10]. Although this distribution of bleeding aligns with our study, the difference in gastrointestinal bleeding risk remains non-significant, as reported in past studies (17,18). An observational meta-analysis involving 1,332,956 non-valvular AF patients found no significant difference in gastrointestinal bleeding rates between rivaroxaban and warfarin [

17]. Additionally, a review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), retrospective database studies, and large-scale prospective cohort studies reported no substantial difference in major gastrointestinal bleeding risk between DOACs and warfarin, although they noted that DOAC-treated patients experienced less severe gastrointestinal bleeding and required less intensive management [

18]. Our findings are consistent with a recent meta-analysis by Karakasis et al., which showed that DOACs are equally effective as warfarin and offer a better safety profile in obese patients (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m²), including a lower risk of bleeding. In addition to the findings from the meta-analysis, our study adds real-world data and employs propensity score matching to adjust for baseline characteristics that further support the use of DOACs in obese patients. [

19]

Mortality Literature of DOACs vs Warfarin in Obesity

Our results showed a statistically significant reduction of mortality risk in AF patients treated with DOACs; a finding mirrored by Barakat et al. They found that all BMI groups, except for the underweight, experienced lower mortality rates with DOACs compared to warfarin, with a 34% reduction in all-cause mortality in patients with a BMI of 40 or above

[13]. Law et al. also found an association between lower all-cause mortality rates in females and DOAC use compared to warfarin, although the BMI of the population was unspecified

[16]. This association persisted changed to statistically insignificant results after PSM. The superior efficacy of DOACs over warfarin remains to be explained. Some studies suggest that warfarin-treated patients may be less compliant, while others posit that warfarin’s inconsistent therapeutic range could affect its safety and effectiveness. These factors were not measured in our study, but the consistent link between DOACs and less adverse outcomes remains clinically significant.

Strengths and Limitation

Our study boasts several noteworthy strengths. First, we utilized PSM to address possible confounding factors, thus heightening the credibility of our results. Second, our observational study provided the opportunity to examine the efficacy and safety of DOACs within a real-world context, offering useful insights. Lastly, our findings can influence clinical decisions and enhance patient outcomes, as they present evidence of DOACs’ efficacy and safety within a population that has not been thoroughly studied.

As the study is a retrospective observational study, there was a selection bias, which we addressed by adjusting for potential confounders. Another limitation is the reliance on electronic medical records, which were only available in our center since 2015, resulting in a short follow-up period. The generalizability of our findings was limited, as most of the patients in our cohort received apixaban. Nevertheless, this limitation offers an opportunity for further research on other types of DOACs. Finally, it should be noted that we did not account for possible medication switchovers during the study period.

5. Conclusions

The study concluded that DOACs were associated similar efficacy and safety compared to warfarin in obese patients. There is a trend to lower rates of all-cause mortality in AF patients with high BMI compared to warfarin. This suggests that DOACs may be a safer alternative. More research is needed to endorse these findings and develop guidelines for DOACs use in this demographic. In essence, the study provides useful insight into DOACs in obese AF patients, aiding clinicians in making informed decisions about anticoagulation therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., A.M.A., H.A., S.A., G.A., G.A.F., S.A., and H.A.; methodology, A.A., A.M.A., H.A., S.A., G.A., G.A.F., S.A., and H.A.; software, A.A., A.M.A., H.A., S.A., G.A., G.A.F., S.A., and H.A.; validation, A.A., A.M.A., H.A., S.A., G.A., G.A.F., S.A., and H.A.; formal analysis, A.A., A.M.A., and H.A.; investigation, A.A., A.M.A., H.A., S.A., G.A., G.A.F., S.A., and H.A.; resources, A.A., A.M.A., H.A., S.A., G.A., G.A.F., S.A., and H.A.; data curation, S.A., G.A., G.A.F., S.A., and H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A., G.A., G.A.F., S.A., and H.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A., A.M.A., H.A., S.A., G.A., G.A.F., S.A., and H.A.; visualization, A.A., A.M.A., H.A., S.A., G.A., G.A.F., S.A., and H.A.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, A.A. and S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (protocol code NRC22R-130-02, approved on 24 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study, the use of anonymized data, and the absence of any identifying information, as approved by the IRB.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions but can be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC) for their support and to the team members who contributed to the administrative and technical aspects of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fuster, V.; Rydén, L.E.; Cannom, D.S.; Crijns, H.J.; Curtis, A.B.; Ellenbogen, K.A.; Halperin, J.L.; Le Heuzey, J.-Y.; Kay, G.N.; Lowe, J.E.; et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2006, 114, e257–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavie, C.J.; De Schutter, A.; Parto, P.; Jahangir, E.; Kokkinos, P.; Ortega, F.B.; Arena, R.; Milani, R.V. Obesity and prevalence of cardiovascular diseases and prognosis—the obesity paradox updated. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 58, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavie, C.J.; Sharma, A.; Alpert, M.A.; De Schutter, A.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Milani, R.V.; Ventura, H.O. Update on obesity and obesity paradox in heart failure. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 58, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.X.; Sullivan, T.; Sun, M.T.; Mahajan, R.; Pathak, R.K.; Middeldorp, M.; Twomey, D. Obesity and the risk of incident, post-operative, and post-ablation atrial fibrillation: A metaanalysis of 626,603 individuals in 51 studies. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2015, 1, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxley, R.R.; Lopez, F.L.; Folsom, A.R.; Agarwal, S.K.; Loehr, L.R.; Soliman, E.Z.; Maclehose, R.; Konety, S.; Alonso, A. Absolute and attributable risks of atrial fibrillation in relation to optimal and borderline risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation 2011, 123, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, G.D.; Mouland, E. Peri-Procedural Management of Oral Anticoagulants in the DOAC Era. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 60, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekaj, A.Y.; Mekaj, Y.H.; Duci, S.B.; Miftari, E. New oral anticoagulants: their advantages and disadvantages compared with vitamin K antagonists in the prevention and treatment of patients with thromboembolic events. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2015, ume 11, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Beyer-Westendorf, J.; Davidson, B.L.; Huisman, M.V.; Sandset, P.M.; Moll, S. Use of the direct oral anticoagulants in obese patients: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2016, 14, 1308–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perales, I.J.; Agustin, K.S.; DeAngelo, J.; Campbell, A.M. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin for stroke prevention and venous thromboembolism treatment in extreme obesity and high body weight. Ann. Pharmacother. 2019, 54, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coons, J.C.; Albert, L.; Bejjani, A.; Iasella, C.J. Effectiveness and safety of direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in obese patients with acute venous thromboembolism. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2020, 40, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spyropoulos, A.C.; Ashton, V.; Chen, Y.-W.; Wu, B.; Peterson, E.D. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin treatment among morbidly obese patients with venous thromboembolism: Comparative effectiveness, safety, and costs. Thromb. Res. 2019, 182, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloi, K.G.; Fierro, J.J.; Stein, B.J.; Lynch, S.M.; Shapiro, R.J. Investigation of direct-acting oral anticoagulants and the incidence of venous thromboembolism in patients weighing≥ 120 kg compared to patients weighing< 120 kg. J. Pharm. Pr. 2019, 34, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.F.; Jain, S.; Masri, A.; Alkukhun, L.; Senussi, M.; Sezer, A.; Wang, Y.; Thoma, F.; Bhonsale, A.; Saba, S.; et al. Outcomes of direct oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation patients across different body mass index categories. JACC: Clin. Electrophysiol. 2021, 7, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushnir, M.; Choi, Y.; Eisenberg, R.; Rao, D.; Tolu, S.; Gao, J.; Mowrey, W.; Billett, H.H. Efficacy and safety of direct oral factor Xa inhibitors compared with warfarin in patients with morbid obesity: a single-centre, retrospective analysis of chart data. Lancet Haematol. 2019, 6, e359–e365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.A.; Beyer-Westendorf, J.; Davidson, B.L.; Huisman, M.V.; Sandset, P.M.; Moll, S. Use of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with obesity for treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism: Updated communication from the ISTH SSC Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 1874–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosovsky, R.P.; Kline-Rogers, E.; Lake, L.; Minichiello, T.; Piazza, G.; Ragheb, B.; Waldron, B.; Witt, D.M.; Moll, S. Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Obese Patients with Venous Thromboembolism: Results of an Expert Consensus Panel. Am. J. Med. 2023, 136, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, H.; Zeng, H.; Lv, J. Effects of rivaroxaban and warfarin on the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Cardiol. 2021, 44, 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benamouzig, R.; Guenoun, M.; Deutsch, D.; Fauchier, L. Review Article: Gastrointestinal Bleeding Risk with Direct Oral Anticoagulants. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2021, 36, 973–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakasis, P.; Ktenopoulos, N.; Pamporis, K.; Sagris, M.; Soulaidopoulos, S.; Gerogianni, M.; Leontsinis, I.; Giannakoulas, G.; Tousoulis, D.; Fragakis, N.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Direct Oral Anticoagulants versus Warfarin in Obese Patients (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) with Atrial Fibrillation or Venous Thromboembolism: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).