1. Introduction

Hyperacusis is a symptom where sounds that are normally perceived as moderately loud are experienced as excessively loud [

1]. It is included in the ICD-11 and is defined as “the experience of excessive loudness of sound that most people tolerate well, often accompanied by discomfort” [

2]. People with hyperacusis have reduced tolerance to everyday/environmental sounds [

3]. It is often associated with discomfort or even pain in the ears when sounds reach a certain loudness level that is typically tolerable for most people without the disorder [

4]. Other types of reduced sound tolerance include misophonia and phonophobia [

5]. Hyperacusis typically involves discomfort with sounds reaching a specific loudness level, while misophonia involves strong emotional reactions to specific sounds (often bodily sounds, such as chewing) without the discomfort being related to the loudness of the sound [

4,

5]. Emotional reactions in both conditions can be similar, but their aetiologies differ significantly [

4,

6]. Patients with hyperacusis may experience auditory discomfort in social gatherings, interactions with children, professional meetings, and in restaurants [

7].

The relationship between hyperacusis and Auditory Processing Disorder (APD) has been studied in the literature. In one study conducted with young adults aged 18-24, the Khalfa Hyperacusis Questionnaire and the University of Cincinnati Auditory Processing Inventory (UCAPI) were administered online. It was found that 26.43% of the young adults had high scores on the hyperacusis questionnaire administered to them and 36.04% had high scores on rhe UCAPI [

8]. Another study found that patients diagnosed with APD had significantly worse scores on the Hyperacusis test [

9]. In children suspected of having APD without hearing loss, 62% had hyperacusis, while 35% of children with hearing loss had symptoms of hyperacusis [

10].

The exact cause of hyperacusis is not known. However, several mechanisms have been investigated to explain its existence. One model suggests that increased spontaneous firing rates of nerve fibres due to plasticity and the enhancement of medium-intensity sounds could lead to the development of hyperacusis [

11]. Another possible explanation is increased neural synchronization. Experiments on the auditory cortex of animals have shown that increased synchronization of spontaneous firing rates worsened after exposure to high-intensity sound, similar to findings in humans with tinnitus based on electroencephalogram results. Additionally, changes in the tonotopic organization of the auditory cortex have been suggested due to damage to parts of the epithelium. Thus, some neurons become "tuned" to adjacent tones, where neurons might have been damaged, such as in cases of hearing loss. The unpleasant emotional reactions and discomfort experienced by people with hyperacusis suggest that not only the auditory system’s enhancement of sound is responsible, but also the activation of the limbic system [

12]. In their study with animals, Chen et al. found that acoustic trauma in the low and high-frequency regions of the cochlea, after noise exposure, caused hyperactivity in the auditory cortex and amygdala, leading to increased loudness perception of high and low frequencies (hyperacusis).

There is no consensus yet on how to evaluate and diagnose patients with suspected hyperacusis due to methodological differences in studies [

6]. It is important to take a detailed medical history initially for differential diagnosis and accurate evaluation [

11]. What is commonly accepted is the reduced Loudness Discomfort Levels (LDL) in patients with hyperacusis compared to those without the disorder. LDL values refer to the loudness level at which the signal begins to be uncomfortable for the patient. The signal is presented to the patient at an intensity of 60-70 dB HL, and the clinician increases the intensity gradually by 5 dB HL until the discomfort level is found )[

9]. These values, even if found at low levels indicating greater discomfort, are not sufficient on their own to confirm hyperacusis, and a detailed examination is necessary [

6,

11]. Many studies support that LDL values for the typical population range between 90-100 dB HL (Sherlock & Formby, 2005 ΝA ΤHΝ ΠΡOΣΘΕΣΩ). Under the presence of hyperacusis, LDL values are lower, typically within the range of 60-85 dB HL [

14,

15].

In addition to LDL values, questionnaires can be used to assess the presence of hyperacusis. The Khalfa Hyperacusis Questionnaire and the Multiple Activity Scale for Hyperacusis (MASH) are two questionnaires that have been researched for their effectiveness [

13,

15]. The evaluation and diagnosis of hyperacusis are based on the patient’s subjective experience and the symptoms they report.

Regarding treatment, there is no specific therapeutic method found yet to address hyperacusis (Pienkowski et al., 2014 ; Jastreboff & Jastreboff, 2003). Therapeutic methods used for patients with tinnitus to improve their symptoms are also used for hyperacusis, such as counseling/psychological support (Pienkowski et al., 2014), Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) (Baguley & Andersson, 2007), and sound therapy (Jastreboff, 2007, Formby et al., 2003). CBT has been shown to benefit participants with tinnitus, hyperacusis, and misophonia by reducing stress levels (Aazh et al., 2019). For patients with hyperacusis and tinnitus, a CBT program that included music therapy showed significant results in standardized questionnaires administered before and after therapy (Nolan et al., 2020).

For sound therapy, exposure to white noise can minimize hyperacusis symptoms with or without tinnitus (Jastreboff, 2007). It is also suggested that patients be exposed to a broad-spectrum sound at continuously low intensity for months, with benefits observed in some but not all patients (Jastreboff&Jastreboff, 2003; Formby et al., 2003; Formby & Gold, 2002). Exposure to broad-spectrum sound with a gradual increase in intensity and duration is recommended, with the use of pink noise in this case. Another auditory method involves listening to the annoying sounds for each patient, with a gradual increase in the duration and intensity of the stimulus, and the patient’s decision on when to be exposed to the real sound (Tyler et al., 2014), which forms the basis of the present study.

Regarding protocols combining counselling methods with auditory training, Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (TRT) is widely used to reduce tinnitus symptoms and seems to benefit patients with hyperacusis as well (Jastreboff, 2015 ; Pienkowski et al., 2014; Jastreboff, 2007; Jastreboff&Jastreboff, 2003;). Hyperacusis Activities Treatment (HAT) is a modification of Tinnitus Activities Treatment (TAT) and focuses on various counselling areas such as emotion, communication, and sleep. Counselling is combined with specialized auditory training, relaxation exercises, and medication (Pienkowski et al., 2014).

These findings highlight that hyperacusis affects many individuals, and its impact on daily life is detrimental. Thus, further investigation of therapeutic methods for patients with the disorder is important. This study choses the therapeutic method of focusing on an annoying sound and gradually increasing the stimulus intensity, while keeping the exposure duration constant, aiming to investigate the potential improvement of hyperacusis symptoms. According to the research data mentioned earlier on the positive relationship between hyperacusis and APD and the absence of literature on temporal resolution and hyperacusis, the second purpose of this study is first set the baseline on the performance of people with hyperacusis on the temporal analysis assessment test and then to investigate whether temporal resolution in individuals with hyperacusis can be improved.

The research questions are as follows:

Can hyperacusis be improved through systematic exposure to annoying sounds under experimental controlled conditions?

Can there be an improvement in temporal resolution in individuals with hyperacusis who have undergone auditory training?

2. Materials and Methods

Approval for this survey was obtained from the ethics committee of the Aristotle University, Department of Medicine with the approval code 218/2023. The study involved 33 participants, 17 in the experimental group (3 men and 14 women, aged 29-49) and 16 in the control group (1 man and 15 women, aged 23-57). Participants were recruited via social media platforms and various online communities, particularly those with an interest in sound sensitivity (e.g., musicians, educators). The researcher published the survey and the questionnaire and invited those interested to complete it. After scoring the questionnaire for each person, she sent an email with the consent forms for the survey and all the details for participation. The interested parties signed the documents and an online meeting was scheduled. In this interview, annoyance to sounds was informally assessed and participants selected an annoying sound, based on which the researcher would design the personalized auditory program. For the purposes of establishing a baseline GIN and the Unitron hearing detection test were administered.

Participants were divided into experimental and control groups after completing the Khalfa Hyperacusis Questionnaire. The experimental group included 17 participants with scores above 16 (Fioretti et al., 2015). Four participants withdrew from the therapeutic process for personal reasons, three did not complete their interview, one participant was rejected due to sensorineural hearing loss and non-compliance with the doctor’s instructions to use a hearing aid (the initial number of the experimental group was 25 participants).

Additionally, the data of one participant in the control group were not included in the statistical analysis as she did not follow the therapeutic process correctly regarding the recommended frequency and the instruction to listen to the auditory training sounds with headphones (the initial number of participants on the control group was 17).In the experimental group, 3 participants were musicians with thresholds above 20 dB for some frequencies, 2 of whom had a history of high-frequency hearing loss. Two participants reported tinnitus in their history, and three female participants had thresholds greater than 20 dB HL.

Tools used:

1. Khalfa Hyperacusis Questionnaire: This questionnaire was developed by Khalfa et al. (2002) and consists of 14 questions that evaluate the extent of hyperacusis. Participants rate their responses on a scale from 0 (never) to 3 (always), with higher scores indicating greater sensitivity to sounds [

27]. The questionnaire is divided into three subscales: attentional, social, and emotional, assessing how hyperacusis affects different aspects of daily life. In our study, a Greek adaptation of the questionnaire was given to the participants, which was standardized at MSc in APD, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece.

2. Unitron Online Hearing Screener: This test screens the hearing acuity of participants and assists in screening for hearing loss (23). There were no exclusion criteria for the survey due to hearing loss. To start the test, the user must be wearing headphones. First they fill in their age and answer five questions about various everyday listening conditions. The test is then started. The test taker listens to 6 tones (500Hz, 1kHz, 2kHz, 4 kHz, 6kHz, 8kHz) starting at 100% of the volume of his/her loudspeaker and gradually lowering the volume, stopping at the hearing threshold for each tone. At the end, it stores the results for each of the tones.

3. Gaps In Noise (GIN) Test: The gaps in noise (GIN) involves the monaural presentation of gaps of varying duration interspersed in white noise at 50 dB HL [

21,

22,

25]. The GIN is composed of four lists with 32–36 trials each: list 1 has 35 trials, list 2 has 32, list 3 has 29, and list 4 contains 36 trials. Each trial consists of 6 sec of white noise with a 5-sec intertrial interval. Each gap duration (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, and 20 msec) occurs six times within each list. Instructions are given that noise heard might include short gaps, that some gaps might be shorter than others, and that in some cases no gaps are present. Perceived gaps are announced by the subject examined. Ten practice items precede the test. Gap detection threshold is calculated as the shortest gap duration detected on >= 4 of 6 gaps with an added consistency of identification for longer gaps.

4. Auditory Training Program based on an annoying sound: Individuals’ auditory training programs was created by the researcher using the software Audacity (version 3.3.3).These programs included an identified annoying sound for each participant. The audio of the auditory training program had a total duration of 34 minutes and every participant had to hear with headphones. The first minute was relaxing music, the next 10 minutes was the annoying sound and this pattern was repeated until the total time was completed.

All participants were given the same instructions. The minimum weekly frequency suggested (minimum was 3 times a week and maximum was 5 times) and the need for self-monitoring and gradual increase in volume was emphasized to all participants. First week was familiarization with the training program. Then they were exposed to the whole audio. Another instruction was to avoid exposure to loud music and to wear earplugs if they were to be exposed during their everyday activities. In addition to the above guidelines, individualised advices and guidance was given where necessary.

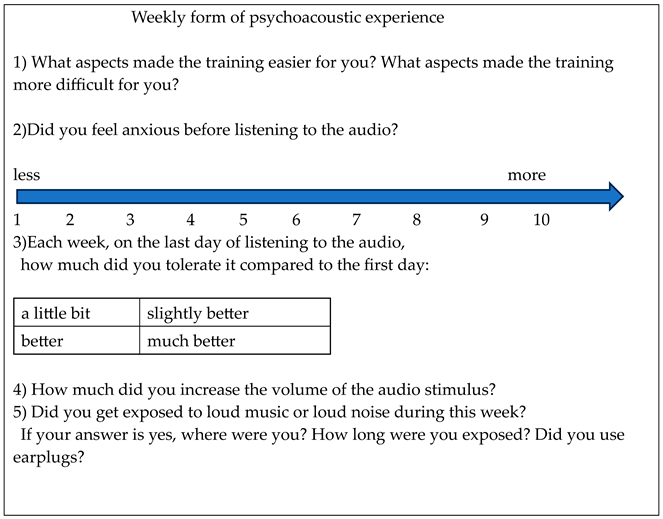

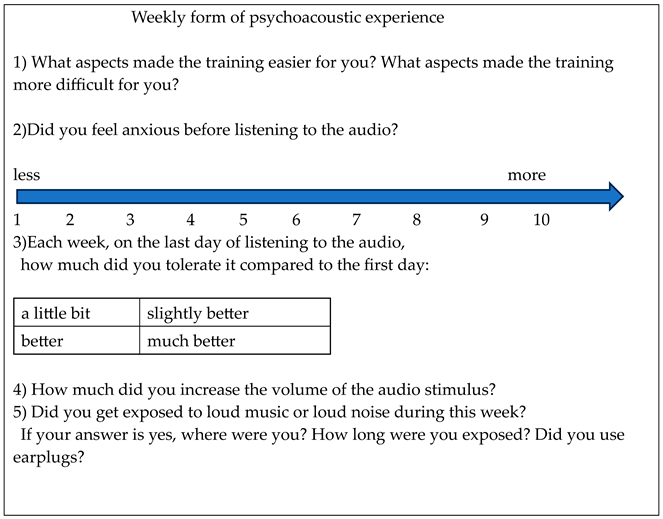

At the end of each week, the researcher communicated with each participant about the progress of the training. As part of their supervision, each week they were required to send in a completed form recording their psychoacoustic experience (Appendix). For some it was necessary to have an online meeting, while for others it was necessary to communicate by telephone, depending on their personal needs.

Both the experimental and the control group underwent auditory training for two months (1 week of familiarisation, 7 weeks of auditory training).

After completing the two-month training period, a final interview was conducted. During this interview, GIN test and the Khalfa Hyperacusis Questionnaire were administered again to assess any changes in auditory processing and hyperacusis symptoms.

3. Results

Data analysis according to the criterion of skewness and kurtosis of z values ranging between -1.96 and +1.96 showed that the results did not follow normal distribution (19,20). The non parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used and statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software program version 28. Regarding the first research question of whether or not there was a benefit in the experimental group after auditory training, there appeared to be a statistically significant difference in the questionnaire results before and after treatment (PRE p= 0.001, mean= 22.2 , SD= 5.17 vs. POST Mean= 18.1, SD=6.40). The results for the control group before and after treatment were not statistically significant (PRE p= 0.115, mean= 10.3, SD=4.04 vs. POST mean=8.8, SD=5.43).

For the experimental group, statistically significant results were obtained for question 7: "Are you particularly sensitive or bothered by road noise?" ( PRE p= 0.34, mean=1.5, SD=0.87 vs. POST mean=1.2, SD=0.88) and question 13 of the hyperacousis questionnaire: "Are you less able to concentrate when there is noise towards the end of the day?" (PRE p=0.010, mean=2.1, SD=0.93, vs. POST mean=1.4, SD=0.93).

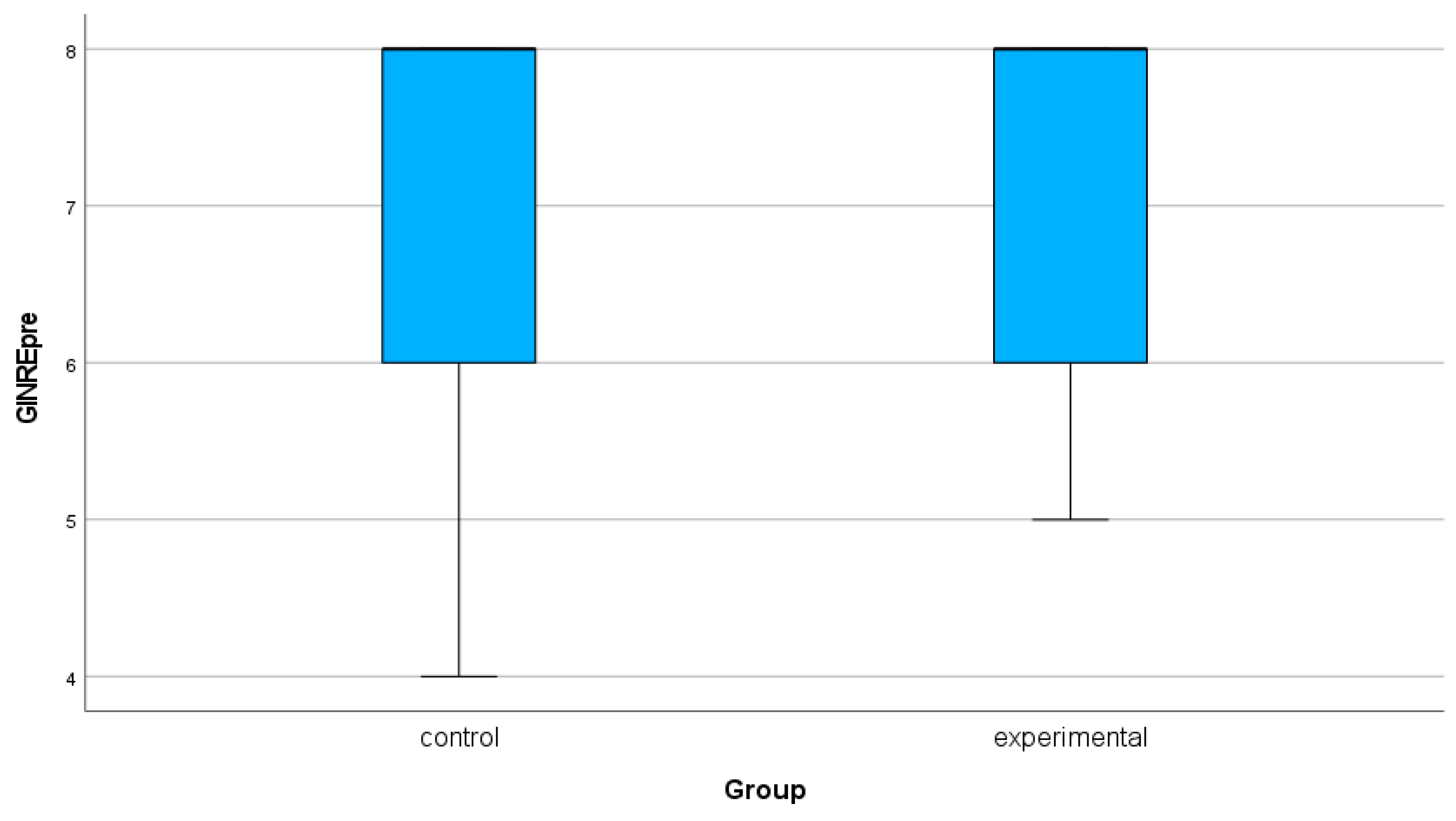

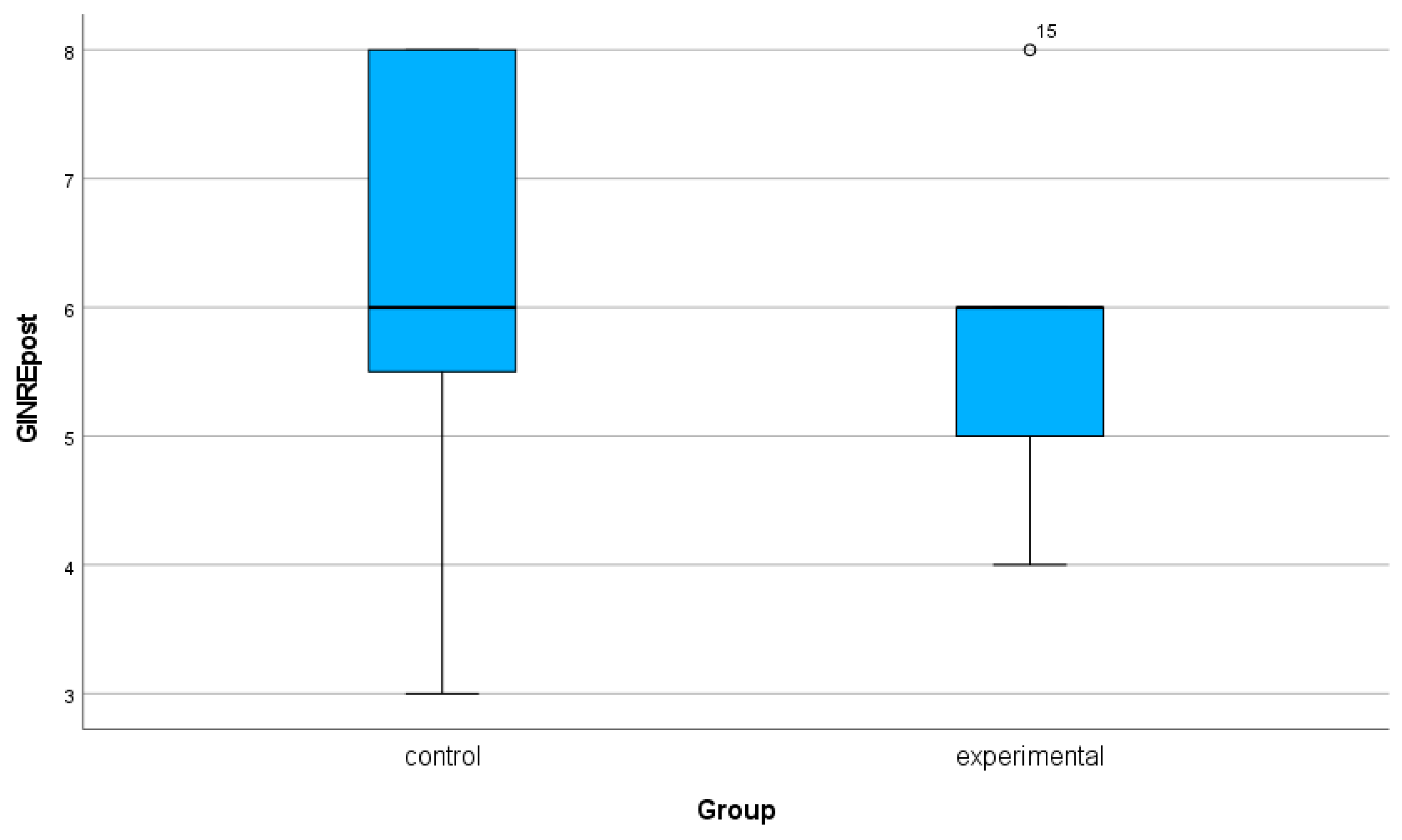

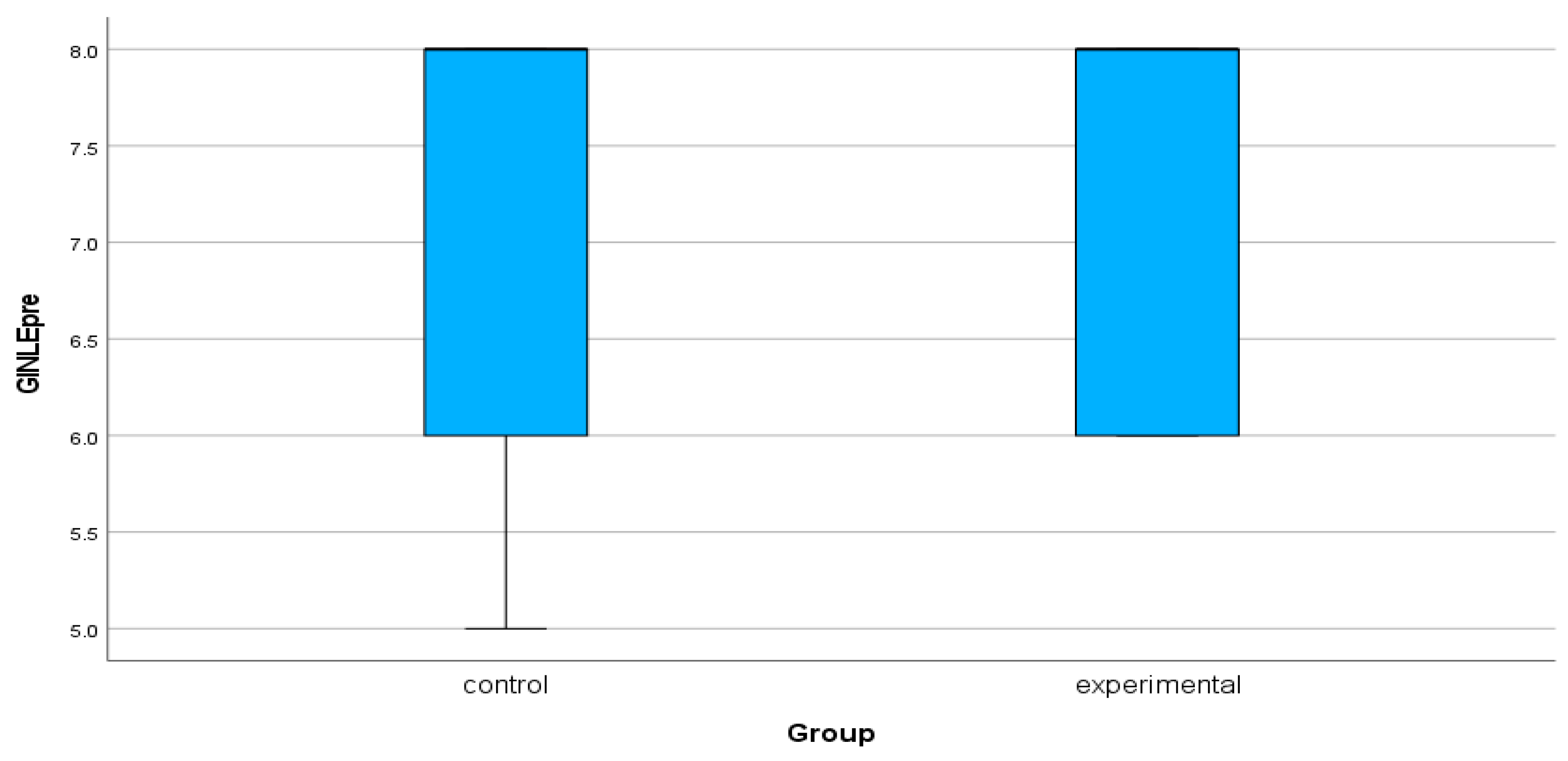

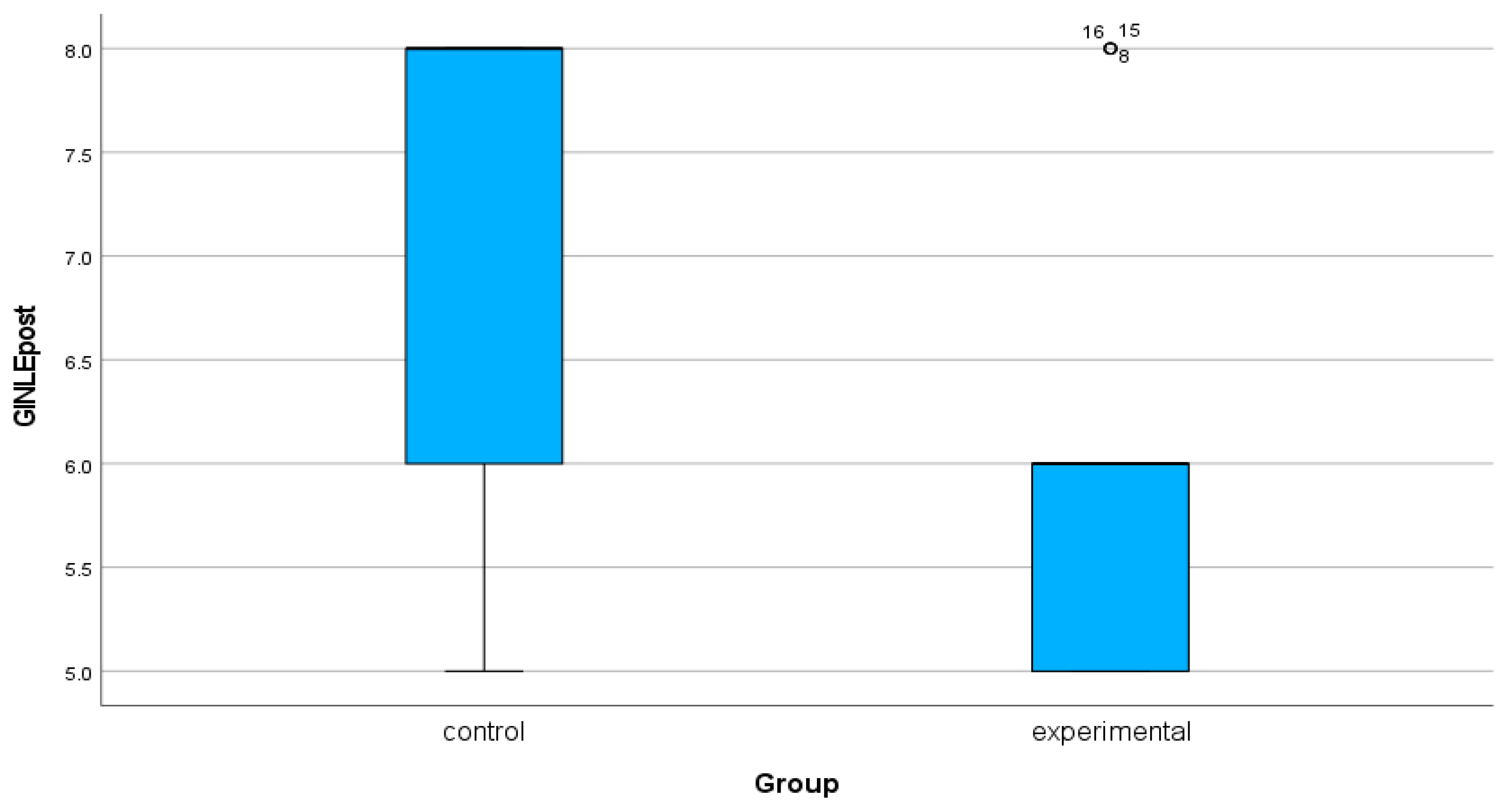

Regarding the second research question, results shown in the boxplots below (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). For the experimental group it appeared that before the auditory training the minimum gap detected in the right ear was 5 msec and after the auditory training 4 msec. For the left ear before auditory training the minimum gap was 6 msec and after training 5 msec. For the control group the corresponding values were for the right ear 4 msec before treatment and 3 msec after it. For the left ear the minimum gap of 5msec remained constant before and after treatment.

4. Discussion

The results of this study are consistent with previous research that has shown the benefits of auditory training and sound therapy for individuals with hyperacusis. Similar to the findings of Jastreboff and Jastreboff (2015), the current study supports the use of gradual exposure to sound as an effective therapeutic approach.

The findings of this study present several important benefits and potential applications for both individuals suffering from hyperacusis and clinicians working to deal with the condition. First, the research demonstrates that systematic exposure to annoying sounds under controlled conditions can effectively reduce the symptoms of hyperacusis, leading to an increased tolerance to everyday sounds. This has profound implications for improving the quality of life for individuals with hyperacusis, allowing them to participate more fully in social and professional environments without experiencing the discomfort or pain typically caused by sound intolerance.

Moreover, the improvement in temporal resolution observed in participants who underwent auditory training suggests that their overall auditory processing abilities can be enhanced, further benefiting their ability to function in noisy or sound-intensive environments. This can be especially useful in educational or professional contexts where concentration in noisy settings is essential. Additionally, the individualized approach to sound therapy in this study highlights the potential for personalized treatment plans, allowing clinicians to tailor interventions to each patient’s unique sound sensitivities. This customization could accelerate symptom management and lead to quicker, more lasting improvements.

An innovative aspect of this study is the incorporation of relaxing music alongside the annoying sound in the auditory training program, a combination that has not been widely used in existing hyperacusis treatment protocols. This approach not only helps to desensitize individuals to the annoying sounds but also creates positive behavioural associations, helping to form a pleasant memory of the annoying sound. The relaxing music acts as a form of reward, contributing to the patient’s relaxation—something that most people suffering from hyperacusis greatly need. This combination provides a psychological and emotional benefit that reinforces the training process. In both the experimental and control groups, most participants emphasized that they felt relief and relaxation during the duration of relaxing music. The fact that sounds were the same the whole time and the intensity parameter changed was commented positively by most of them, with some exceptions. In particular, they expressed that they felt safe and in control of the sound. They were still aware of what would follow each time, therefore they could focus their attention on increasing the volume gradually and experimenting. After approximately 3 weeks, they commented that they no longer noticed the annoying sound in the audio. While they initially felt uncomfortable with the process, they eventually became more comfortable and relaxed.

Furthermore, this method could be applied by therapists to minimize symptoms of hyperacusis in both children and adults, as well as in a wide range of disorders that present hyperacusis as a symptom. In contrast to other programs that require lengthy auditory training sessions, this study’s program, with sessions lasting only 34 minutes, proved highly effective for the experimental group. This shorter session duration could enhance patient compliance and lead to more efficient treatments. Additionally, the study offers a novel contribution to the scientific community by addressing not only hyperacusis symptoms but also improvements in temporal resolution, a topic that has not been extensively studied in relation to hyperacusis. Previous research has focused primarily on tinnitus, making this study’s findings about temporal resolution in hyperacusis a valuable new insight.

Another key advantage of this approach is its non-pharmaceutical nature, offering a sustainable and natural treatment method that reduces the need for medications to manage the emotional and physical distress caused by hyperacusis. Regarding the second research question, for people with hyperacusis there is no literature on temporal resolution, so the gaps identified by the experimental team can be used as a basis for future research, but also to strengthen the therapeutic treatment by having more research data on their auditory processing. The present study is in agreement with others regarding the minimum gap detected by people with normal auditory processing on temporal resolution tests, which is 4.19 msc[

24]. In this study it appeared that the experimental group benefited both ears in terms of temporal resolution. The control group, however, only in the right ear. But the fact that the experimental group also benefited in the left ear, while the control group did not, cannot be explained with certainty. In particular, listening to the auditory program at a higher frequency by the experimental group versus the control could be a factor that influenced the improvement in temporal resolution. Directions were the same for the two groups, but experimental was more focus and willing to try harder than the control group.

Despite the positive findings, the study has some limitations. The study relied on self-reported data, which may be subject to bias. Future research should aim to explore these findings further by involving larger sample sizes and including LDL values for each participant, along with questionnaires to guide the selection of participants for the experimental and control groups.

Regarding the frequency of listening to the audios, participants in the experimental group listened to the audios for an average of 3-4 days per week, while the control group averaged 2-3 days a week, according to their recordings on the form. The difference in listening frequency may be justified by the lack of motivation in the control group and on the other hand the experimental group’s need for benefit. The higher listening frequency in the experimental group could have influenced their positive improvement over the controls. Finally, in some participants from both the experimental and the control groups, the consecutive 8-week interval was not maintained and the period of training was extended. The auditory training began in the fall and was extended until early spring, until the required sample was collected. Several common infections (sinusitis, upper respiratory tract infections and otitis media) were recorded during that time. Therefore, during the period of illness, no training was carried out. This understandably affected their willingness and readiness to continue with their hearing training, with some reporting that they wanted some time to get back on track.

Additional investigation into the parameters for selecting the type and duration of relaxing music, as well as the frequency of exposure, could refine the program’s effectiveness. In conclusion, this study provides a practical, evidence-based approach that can be widely applied in clinical settings, helping patients develop greater tolerance to sounds and improve their overall auditory processing abilities. These findings open the door for more targeted interventions and future research in this field.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Aristotle University, Department of Medicine (218, 14/07/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The survey data cannot be disclosed publicly due to the protection of personal data. Interested should contact in the correspondence email.

Appendix

References

- Sheldrake J., Diehl, P.U., Schaette, R. (2015). Audiometric characteristics of hyperacusis patients. Frontiers in Neurology. 6, 105. [CrossRef]

- International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision (ICD-11), World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases.

- Baguley, D. M., .Baguley, D. M., Andersson, G. (2007). Hyperacusis: Mechanisms, diagnosis, and therapies. SanDiego, CA: Plural.

- Henry, J.A., Theodoroff, S.M., Edmonds, C., Martinez, I., Myers, P.J., Zaugg, T.L.,.

- Goodworth, M.C. (2022). Sound Tolerance Conditions (Hyperacusis, Misophonia, Noise Sensitivity, and Phonophobia): Definitions and Clinical Management. American Journal of Audiology. 31(3), 513-527. [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff P.J. (2007) Tinnitus Retraining Therapy. Progress in brain research. 166, 415-23.

- Jastreboff P.J., Jastreboff, M.M. (2015). Decreased sound tolerance: hyperacusis, misophonia, diplacusis, and polyacusis. Handbook of Clinical Neurology.129, 37587.

- Tyler, R.S., Ji, H., Perreau, A., Witt, S., Noble, W., Coelho, C. (2014). Development and validation of the tinnitus primary function questionnaire. American Journal of Audiology. 23(3), 260-72. [CrossRef]

- Cogen, T., Cetin, Kara, H., Kara, E., Telci, F., Yener, H.M. (2023). Investigation of the relationship between hyperacusis and auditory processing difficulties in individuals with normal hearing. European Archives of Otorhinolaryngol. [CrossRef]

- Spyridakou, C., Luxon, L.M., Bamiou, D.E. (2012). Patient-reported speech in noise difficulties and hyperacusis symptoms and correlation with test results. Laryngoscope 122(7), 1609–1614. [CrossRef]

- Rashid S.M.U., Mukherjee, D., Ahmmed, A.U. (2018).Auditory processing and neuropsychologicalprofiles of childrenwithfunctionalhearingloss. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 114, 51-60.

- Pienkowski M., Tyler, R.S., Roncancio, E.R., Jun, H.J., Brozoski, T., Dauman, N., Coelho, C.B., Andersson, G., Keiner, A.J., Cacace, A.T., Martin, N., Moore, B.C. (2014). A review of hyperacusis and future directions: part II. Measurement, mechanisms, and treatment. American Journal of Audiology. 23(4), 420-36. [CrossRef]

- Sherlock LP, Formby C. Estimates of loudness, loudness discomfort, and the auditory dynamic range: normative estimates, comparison of procedures, and test-retest reliability. J Am Acad Audiol. 2005 Feb;16(2):85-100. [CrossRef]

- Dauman R., Bouscau-Faure, F. (2005). Assessment and amelioration of hyperacusis in tinnitus patients. Acta Otolaryngologica. 125(5), 503-9. [CrossRef]

- AazhAazh H., Landgrebe, M., Danesh, A.A., Moore, B.C. (2019). Cognitive BehavioralTherapy For Alleviating The Distress Caused By Tinnitus, Hyperacusis And Misophonia: Current Perspectives. Psycholοgy Research and Behavior Management. 12, 991-1002. [CrossRef]

- Nolan D.R., Gupta, R., Huber, C.G., Schneeberger, A.R. (2020). An Effective Treatment for Tinnitus and Hyperacusis Based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in an Inpatient Setting: A 10-Year Retrospective Outcome Analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 7,11, 25. [CrossRef]

- Formby, C., Sherlock, L. P., &Gold, S. L. (2003). Adaptive plasticity of loudness induced by chronic attenuation and enhancement of the acoustic back ground. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 114, 55–58.

- Formby, C., Gold, S. L. (2002). Modification of loudness discomfort levels: Evidence for adaptive chronic auditory gain and its clinical relevance. Seminars in Hearing, 23, 21–34. [CrossRef]

- Fioretti A., Tortorella, F., Masedu, F., Valenti, M., Fusetti, M., Pavaci, S. (2015). Validity of the Italian version of Khalfa’s questionnaire on hyperacusis. Acta OtorhinolaryngologicaItalica. 35(2), 110-5.

- Cramer, D.,Cramer, D.,Cramer, D.,Howitt, D. (2004). The SAGE Dictionary of Statistics. London: SAGE.

- Doane, D. P., and Seward, L. E. (2011). Measuring skewness: A forgotten statistic? J. Stat. Educ. 19, 1–18.

- Iliadou V.V., Eleftheriadis, N. (2017). Auditory Processing Disorder as the Sole Manifestation of a Cerebellopontine and Internal Auditory Canal Lesion. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 28(1), 91-101. [CrossRef]

- Musiek F.E., Shinn, J.B., Jirsa, R., Bamiou, D.E., Baran, J.A., Zaida, E. (2005). GIN (Gaps-In-Noise) test performance in subjects with confirmed central auditory nervous system involvement. Ear & Hearing. 26(6), 608-18. [CrossRef]

- Unitron Online Hearing Screener, https://hearing-screener.beyondhearing.org/hearingtest/ZRYJEt/welcome.

- Samelli, A.G., Schochat, E. (2008). The gaps-in-noise test: gap detection thresholds in normal-hearing young adults. International Journal of Audiology. 47(5), 238-45. [CrossRef]

- Shinn, J.B., Chermak, G.D., Musiek, F.E. (2009). GIN (Gaps-In-Noise) performance in the pediatric population. Journal of the american academy of audiology. 20(4), 229-38. [CrossRef]

- Sulakhe, N., Elias, L.J, Lejbak, L., (2003). Hemispheric asymmetries for gap detection depend on noise type. Brain and Cognition. 372-375. [CrossRef]

- Brennan CR, Lindberg RR, Kim G, Castro AA, Khan RA, Berenbaum H, Husain FT. Misophonia and Hearing Comorbidities in a Collegiate Population. Ear Hear. 2024 Mar-Apr 01;45(2):390-399. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).