Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

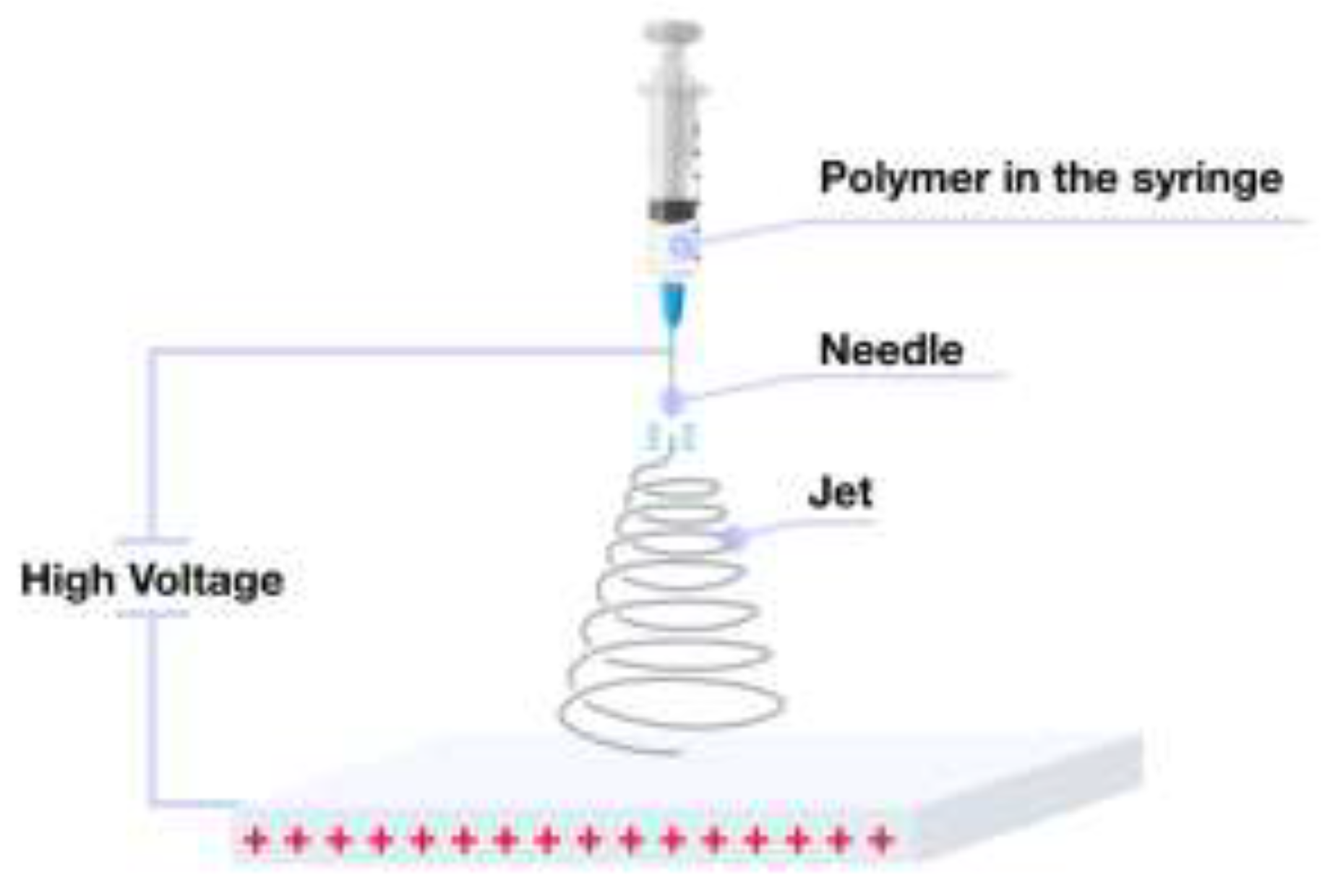

2. Instrumentation and Technical Setup of the Electrospinning Process

2.1. Electrospinning Apparatus for Fiber Fabrication

2.2. Properties of the Polymer Solution

2.3. Optimizing Electrospinning Parameters

2.4. Influence of Environmental Conditions on Electrospinning

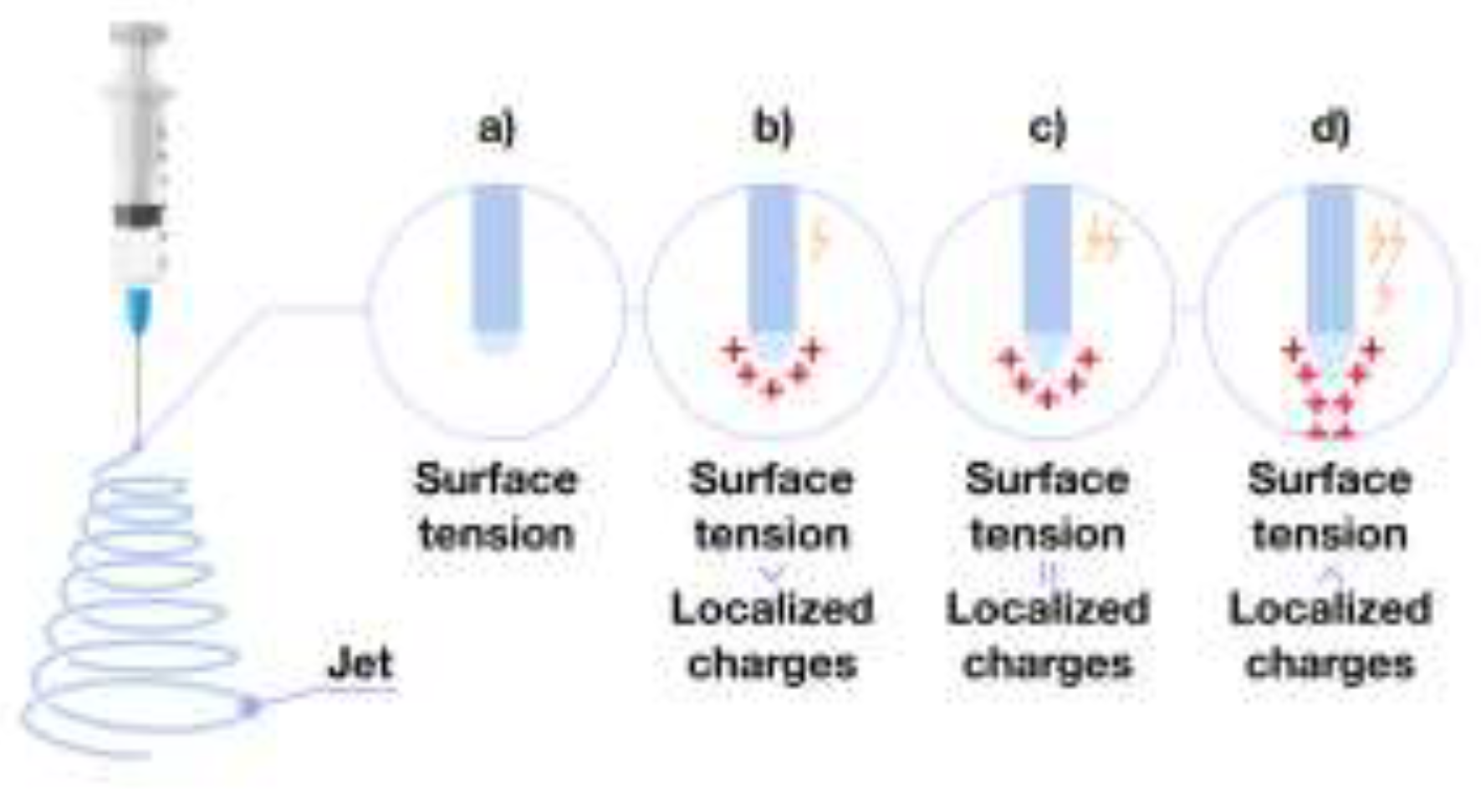

3. Electrospinning

3.1. Polymer Fiber Formation Process

4. Methods for the Production of Polymer Nonwoven Materials

4.1. Melt Electrospinning

4.2. Electrospinning of Multicomponent Systems

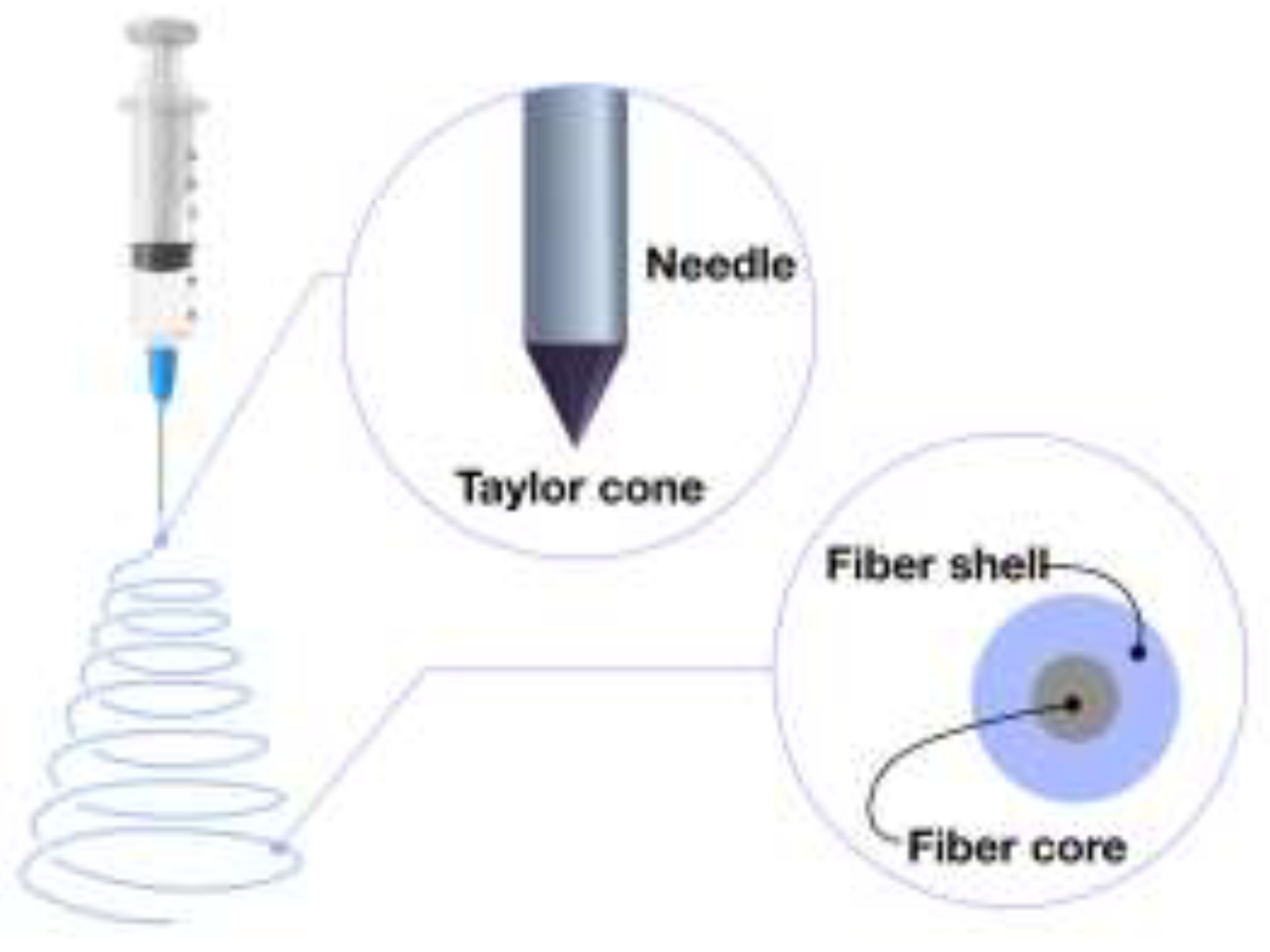

4.3. Coaxial Electrospinning: Advanced Fiber Formation Technique

4.4. Emulsion–Based Electrospinning Techniques

5. Polymers Utilized in Electrospinning for Tissue Engineering Applications

5.1. Applications of Natural and Plant–Based Polymers in Electrospinning for Tissue Engineering Applications

5.1.1. Silk Fibroin

5.1.2. Collagen

5.1.3. Gelatin

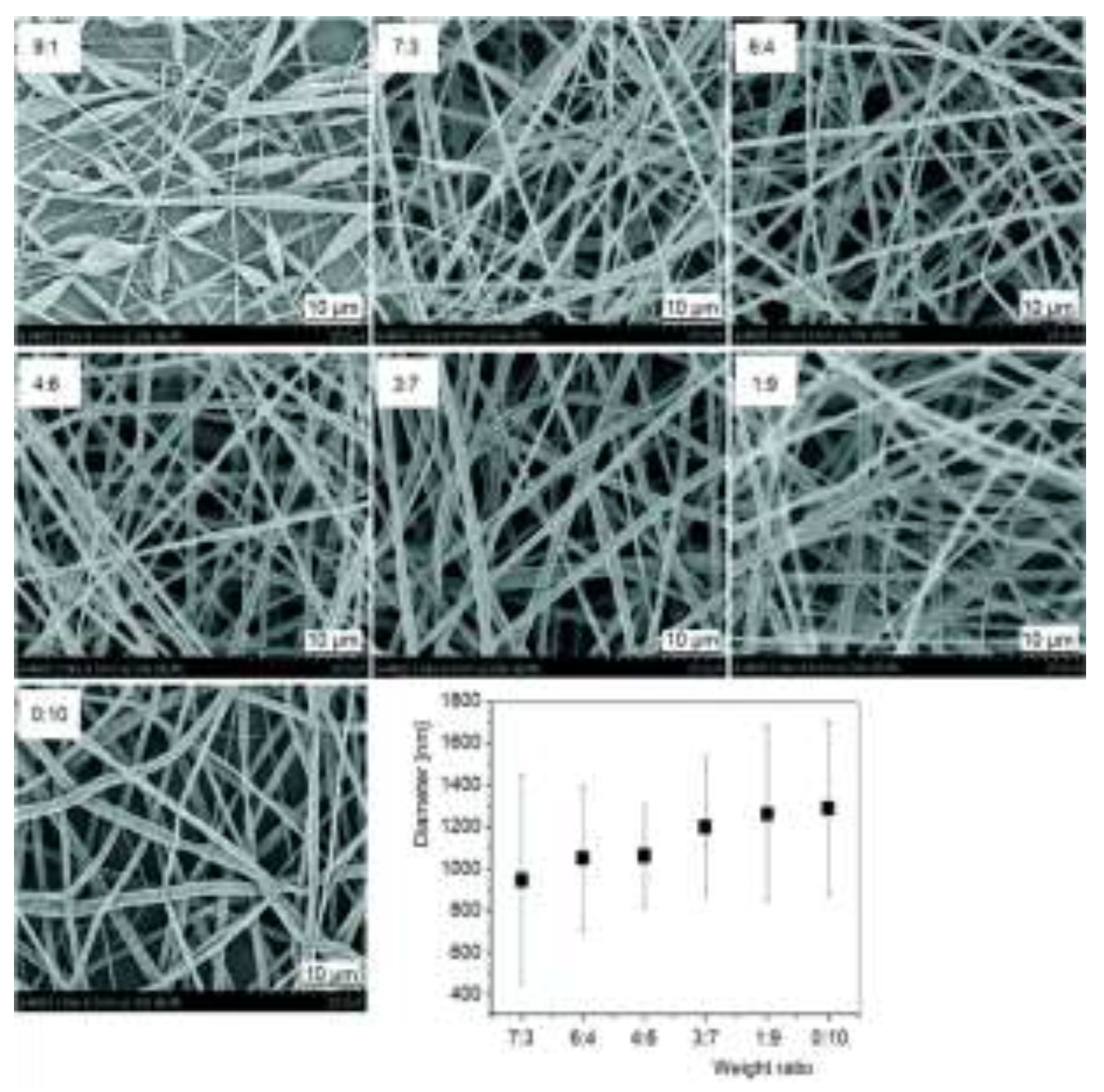

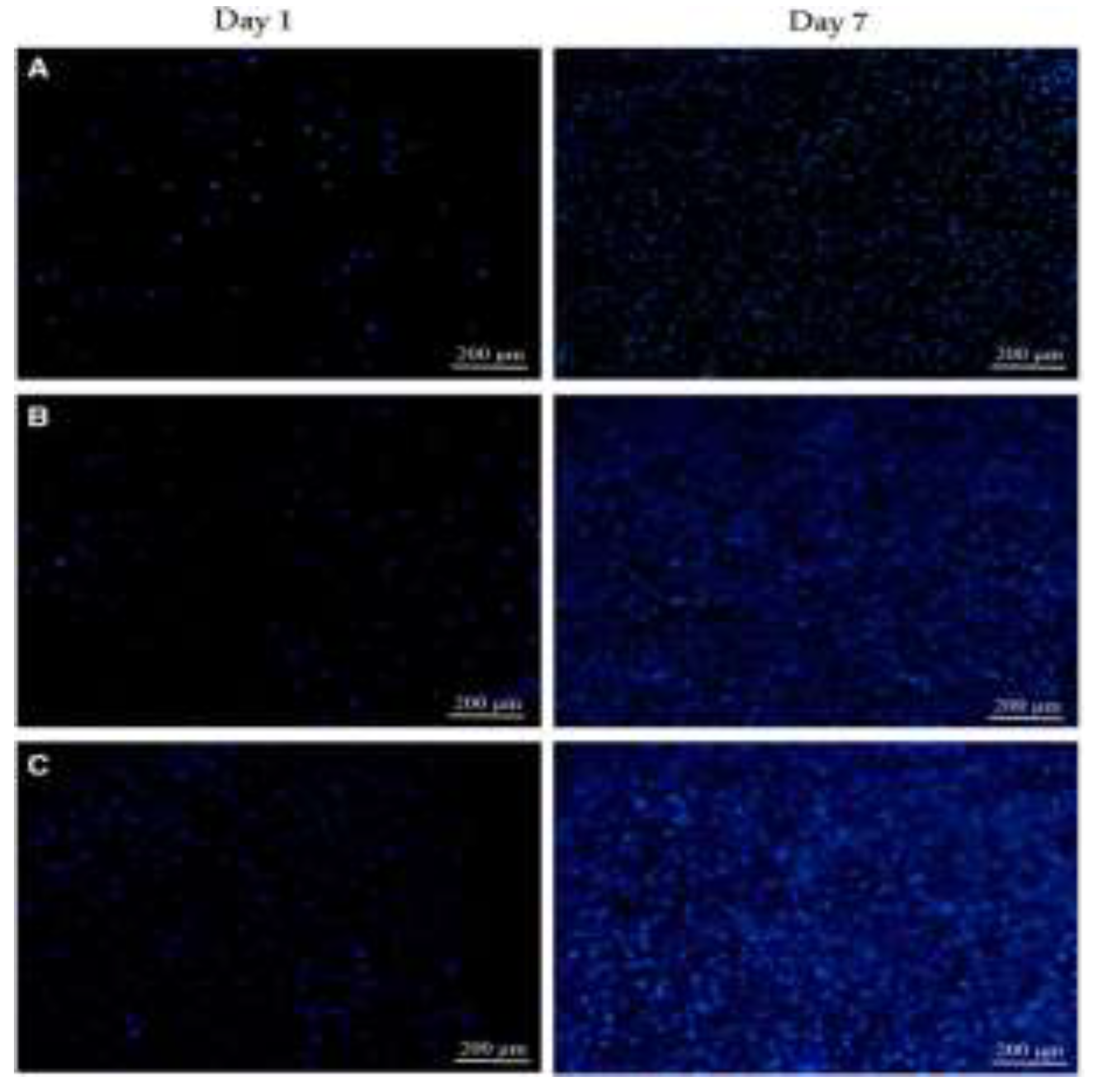

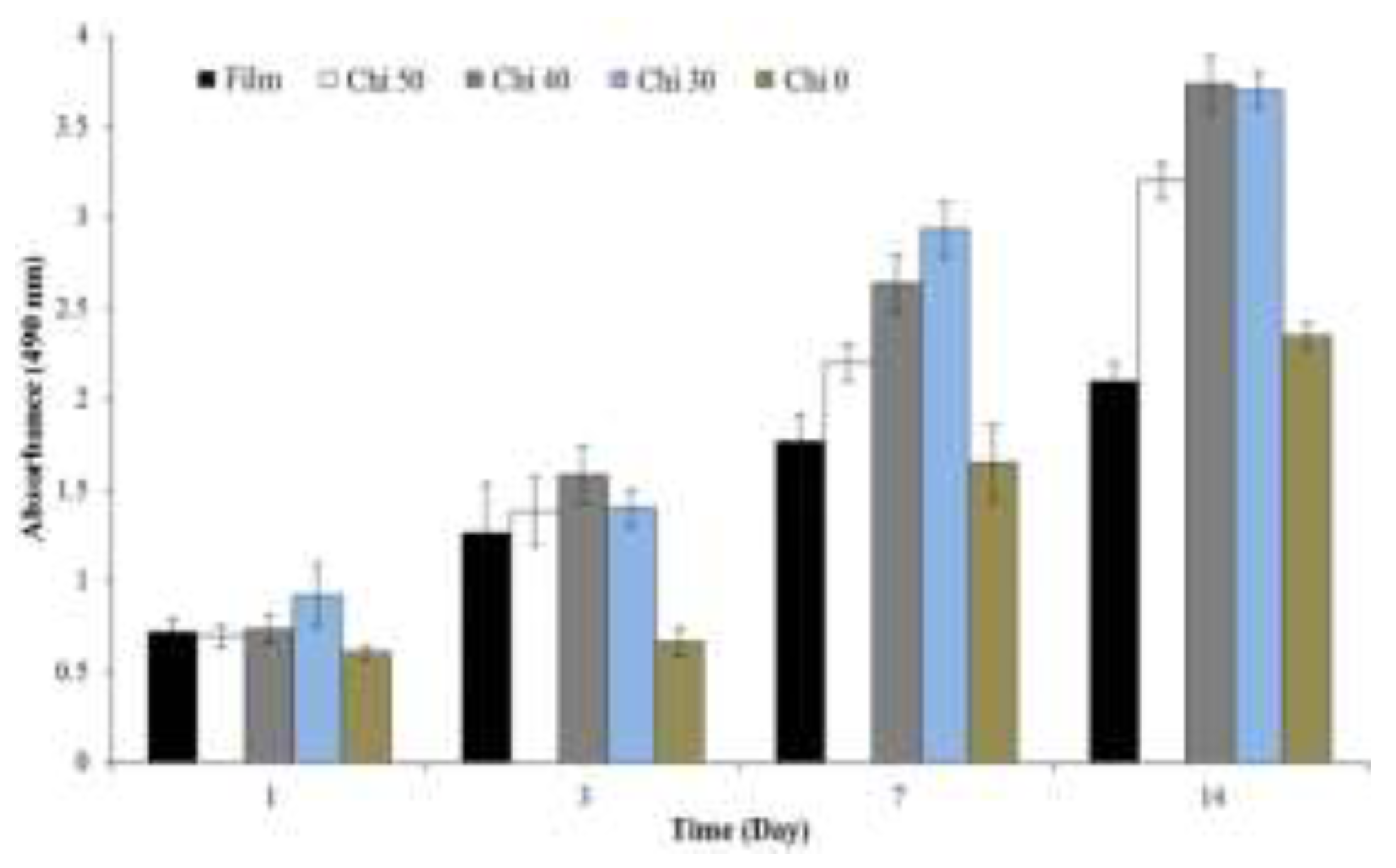

5.1.4. Chitosan

5.1.4. Alginate and Its Derivatives

5.2. Applications of Synthetic Polymers in Electrospinning for Tissue Engineering

5.2.1. Polylactic Acid (PLA)

5.2.2. Poly(ε–Caprolactone) (PCL)

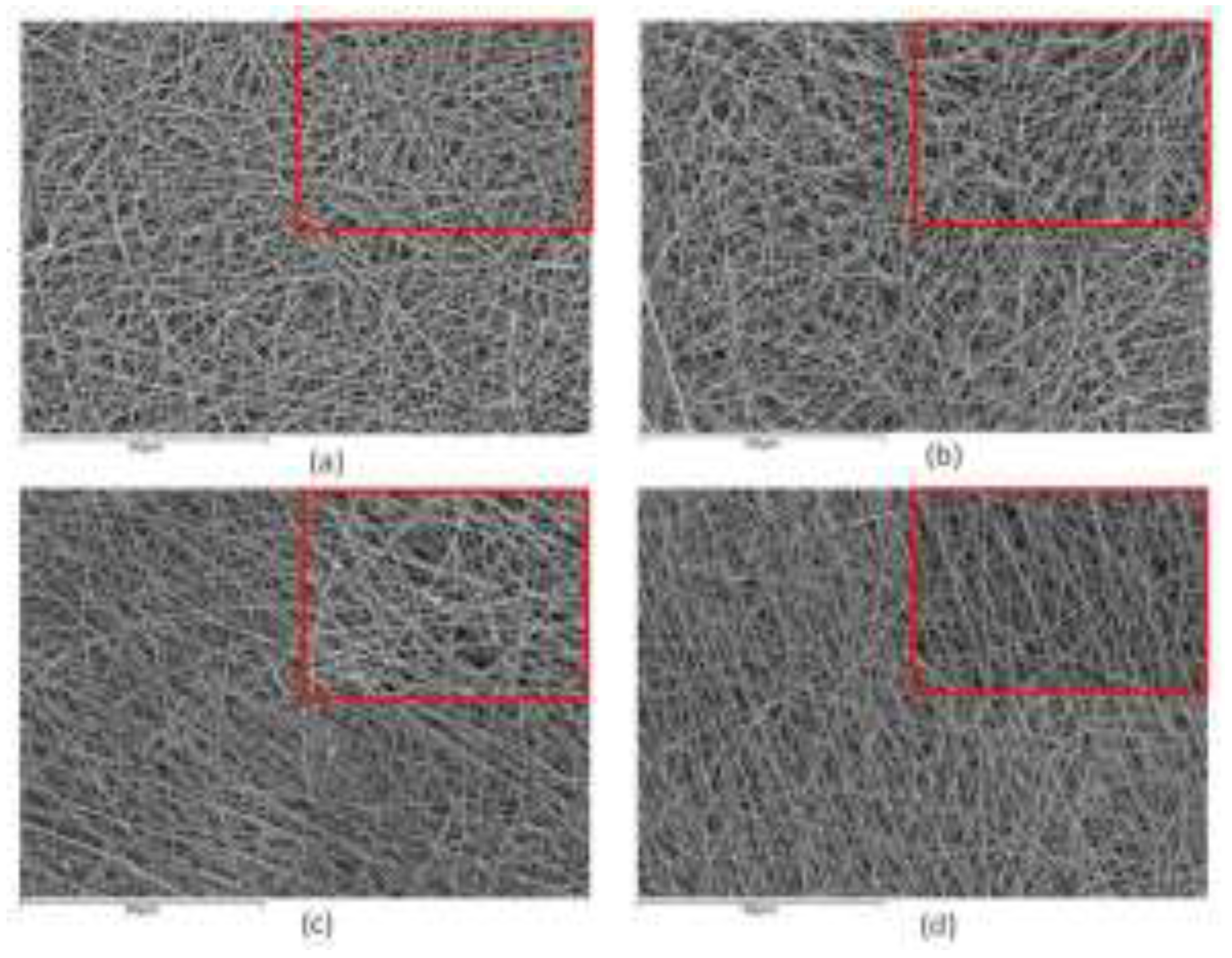

5.2.3. Polyamide–6 (PA6)

5.2.4. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA)

7. Tissue Engineering Using Electrospun Polymeric Matrices

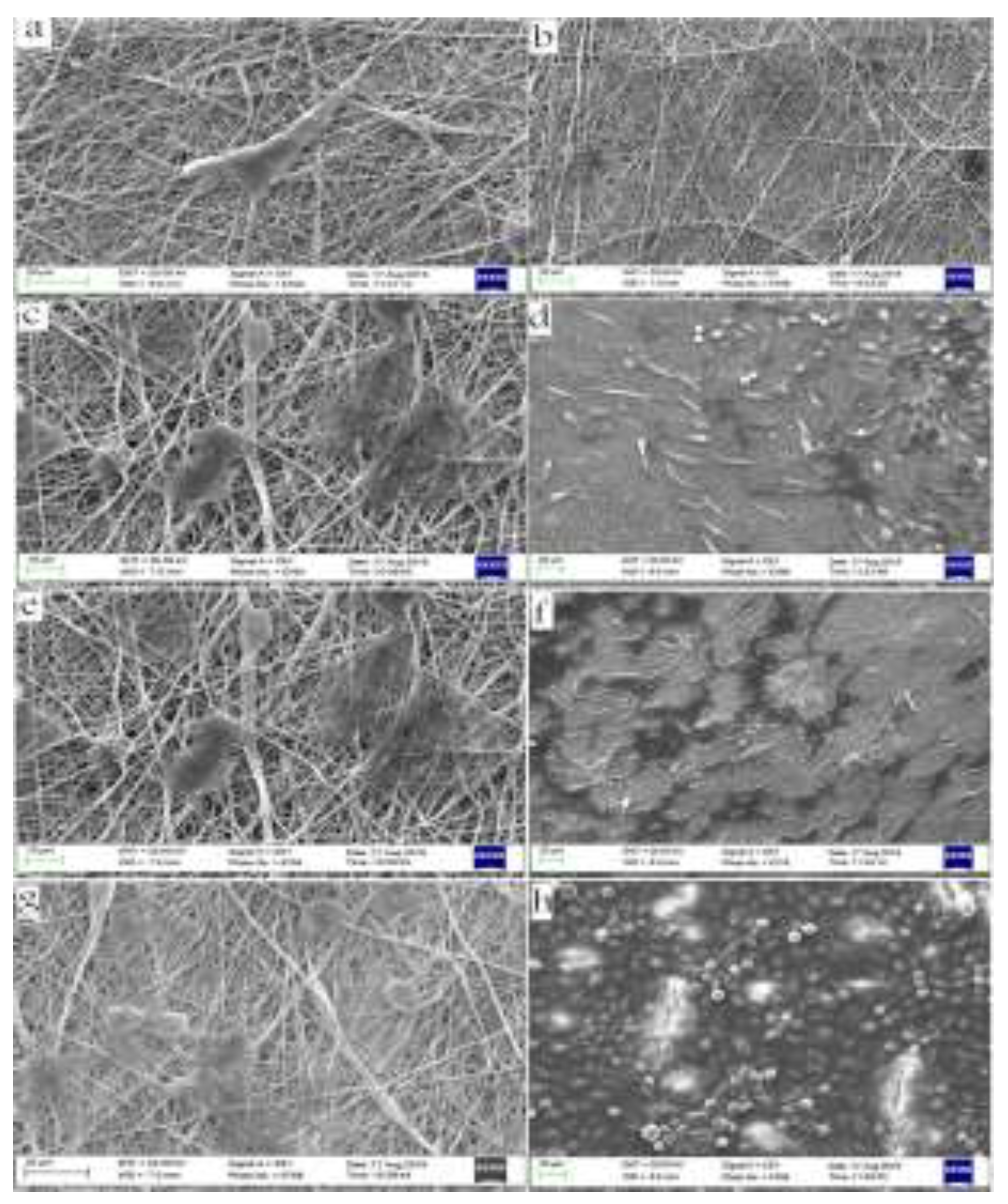

7.1. Wound healing

7.2. Nerve Tissue Engineering

7.3. Bone Tissue Engineering

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cooley, J.F. Apparatus for Electrically Dispersing Fluids. U.S. Patent No. 692,631, 4 February 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.; Cheng, Y.; Niu, X.; Hu, Y. Application of Electrospun Nanofibers in Bone, Cartilage and Osteochondral Tissue Engineering. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2020, 32, 536–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiffrin, R.; Razak, S.I.A.; Jamaludin, M.I.; Hamzah, A.S.A.; Mazian, M.A.; Jaya, M.A.T.; Nasrullah, M.Z.; Majrashi, M.; Theyab, A.; Aldarmahi, A.A.; et al. Electrospun Nanofiber Composites for Drug Delivery: A Review on Current Progresses. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14, 3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulholland, E.J. Electrospun Biomaterials in the Treatment and Prevention of Scars in Skin Wound Healing. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hao, M.; Chen, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, W.; Ramakrishna, S. A Review on Recent Advances in Application of Electrospun Nanofiber Materials as Biosensors. Curr Opin Biomed Eng 2020, 13, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretov, E.I.; Zapolotsky, E.N.; Tarkova, A.R.; Prokhorikhin, A.A.; Boykov, A.A.; Malaev, D.U. Electrospinning for the Design of Medical Supplies. Bulletin of Siberian Medicine 2020, 19, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Min, B.M.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, T.S.; Park, W.H. In Vitro Degradation Behavior of Electrospun Polyglycolide, Polylactide, and Poly(Lactide–Co–Glycolide). J Appl Polym Sci 2005, 95, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, H.; Shin, Y.M.; Terai, H.; Vacanti, J.P. A Biodegradable Nanofiber Scaffold by Electrospinning and Its Potential for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 2077–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, S.K.; Prasath Mani, M.; Ayyar, M.; Rathanasamy, R. Biomimetic Electrospun Polyurethane Matrix Composites with Tailor Made Properties for Bone Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Polym Test 2019, 78, 105955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, L.P.; Rodrigues, A.A.; Macedo, M.; Jardini, A.L.; Maciel Filho, R. Electrospun Polyurethane Membranes for Tissue Engineering Applications. Materials Science and Engineering C 2017, 72, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, M.; Mills, D.K.; Urbanska, A.M.; Saeb, M.R.; Venugopal, J.R.; Ramakrishna, S.; Mozafari, M. Electrospinning for Tissue Engineering Applications. Prog Mater Sci 2021, 117, 100721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, S.A.; Wolfe, P.S.; Garg, K.; McCool, J.M.; Rodriguez, I.A.; Bowlin, G.L. The Use of Natural Polymers in Tissue Engineering: A Focus on Electrospun Extracellular Matrix Analogues. Polymers (Basel) 2010, 2, 522–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.; Huang, Y.; Agarwal, S.; Lannutti, J. Improved Cellular Infiltration in Electrospun Fiber via Engineered Porosity. Tissue Eng 2007, 13, 2249–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

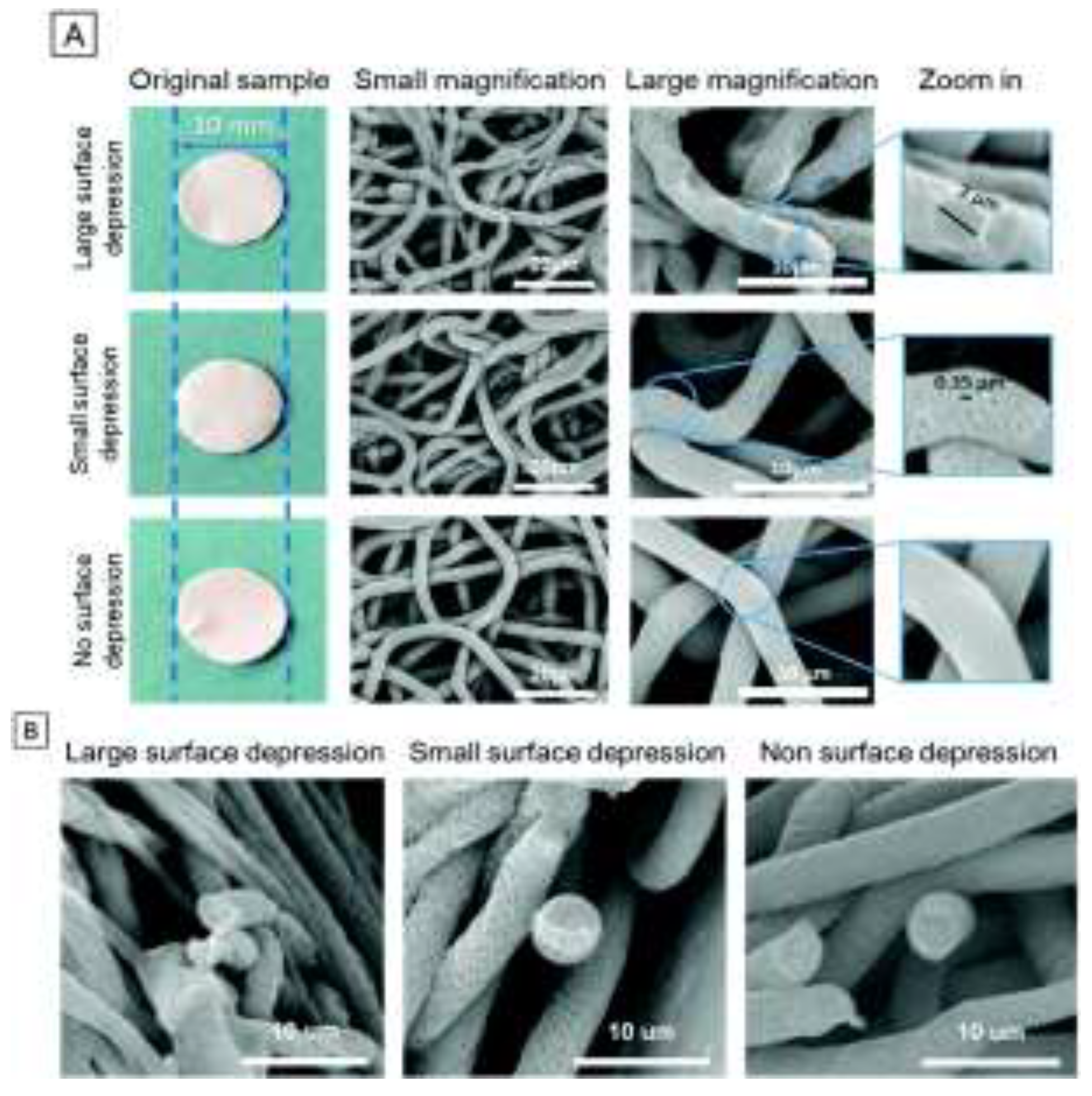

- Şimşek, M. Tuning Surface Texture of Electrospun Polycaprolactone Fibers: Effects of Solvent Systems and Relative Humidity. J Mater Res 2020, 35, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannutti, J.; Reneker, D.; Ma, T.; Tomasko, D.; Farson, D. Electrospinning for Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Materials Science and Engineering C 2007, 27, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.Y.; Suye, S.I.; Fujita, S. Cell Trapping via Migratory Inhibition within Density–Tuned Electrospun Nanofibers. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2021, 4, 7456–7466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sill, T.J.; von Recum, H.A. Electrospinning: Applications in Drug Delivery and Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 1989–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, B.; Park, M.; Park, S.J. Drug Delivery Applications of Core–Sheath Nanofibers Prepared by Coaxial Electrospinning: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicka, K.; Gouma, P.; Simon, S. Electrospun Biocomposite Nanofibers for Urea Biosensing. In Proceedings of the Sensors and Actuators, B: Chemical 2005; 108, 585–588. [CrossRef]

- Halicka, K.; Cabaj, J. Electrospun Nanofibers for Sensing and Biosensing Applications—a Review. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhang, X.; Lu, T.J.; Xu, F. Recent Advances in Electrospun Nanofibrous Scaffolds for Cardiac Tissue Engineering. Adv Funct Mater 2015, 25, 5726–5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

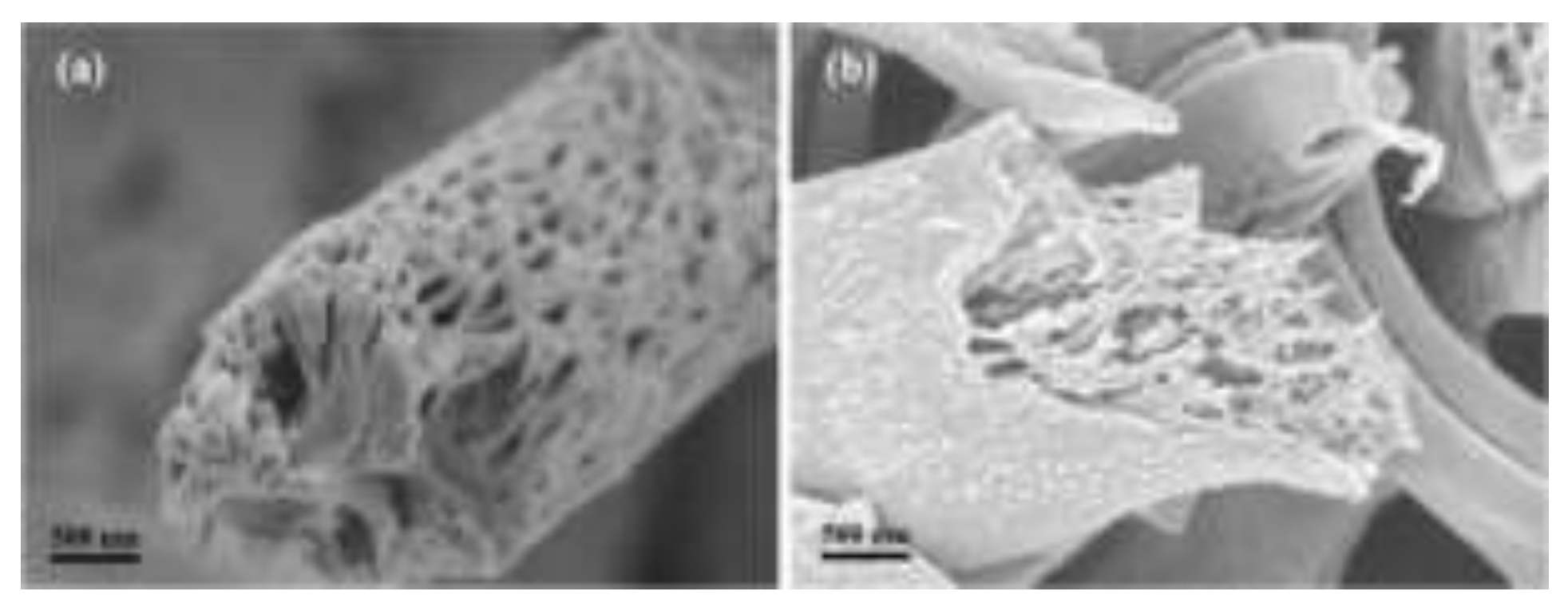

- Nguyen, T.H.; Bao, T.Q.; Park, I.; Lee, B.T. A Novel Fibrous Scaffold Composed of Electrospun Porous Poly(ε–Caprolactone) Fibers for Bone Tissue Engineering. J Biomater Appl 2013, 28, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrigo, M.; McArthur, S.L.; Kingshott, P. Electrospun Nanofibers as Dressings for Chronic Wound Care: Advances, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Macromol Biosci 2014, 14, 772–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, C.G.; Lagerwall, J.P.F. Disruption of Electrospinning Due to Water Condensation into the Taylor Cone. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12, 26566–26576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheideler, W.J.; Chen, C.H. The Minimum Flow Rate Scaling of Taylor Cone–Jets Issued from a Nozzle. Appl Phys Lett 2014, 104, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S.; Becker, A.; Glasmacher, B. Impact of Apparatus Orientation and Gravity in Electrospinning—a Review of Empirical Evidence. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghoraibi, I.; Alomari, S. Different Methods for Nanofiber Design and Fabrication. In Handbook of Nanofibers. Springer International Publishing 2018, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas Munir, M.; Ali, U. Classification of Electrospinning Methods. Nanorods and nanocomposites 2020, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Latifi, M.; Amani–Tehran, M.; Mathur, S. Electrospun Core–Shell Nanofibers for Drug Encapsulation and Sustained Release. Polym Eng Sci 2013, 53, 1770–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhi, S.; Ghassemi, A.; Sajadi, S.M.; Hashemian, M. Comparison of the Mechanical Characteristics of Produced Nanofibers by Electrospinning Process Based on Different Collectors. Heliyon 2024, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro De Prá, M.A.; Ribeiro–do–Valle, R.M.; Maraschin, M.; Veleirinho, B. Effect of Collector Design on the Morphological Properties of Polycaprolactone Electrospun Fibers. Mater Lett 2017, 193, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DN, M.; A, S.; Mavrilas, D. Tuning Fiber Alignment to Achieve Mechanical Anisotropy on Polymeric Electrospun Scaffolds for Cardiovascular Tissue Engineering. Journal of Material Science & Engineering 2018, 07, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, S. An Introduction to Electrospinning and Nanofibers; Singapore: World Scientific, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Angammana, C.J.; Jayaram, S.H. Analysis of the Effects of Solution Conductivity on Electrospinning Process and Fiber Morphology. IEEE Trans Ind Appl 2011, 47, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.J.; Stride, E.; Edirisinghe, M. Mapping the Influence of Solubility and Dielectric Constant on Electrospinning Polycaprolactone Solutions. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 4669–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Lee, S.J.; Min, B.M.; Park, W.H. Effect of Solution Properties on Nanofibrous Structure of Electrospun Poly(Lactic–Co–Glycolic Acid). J Appl Polym Sci 2006, 99, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Deitzel, J.M.; Knopf, J.; Chen, X.; Gillespie, J.W. The Effect of Solvent Dielectric Properties on the Collection of Oriented Electrospun Fibers. J Appl Polym Sci 2012, 125, 2585–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.G.; He, J.H. Solvent Evaporation in a Binary Solvent System for Controllable Fabrication of Porous Fibers by Electrospinning. Thermal Science 2017, 21, 1821–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, H.; Chun, I.; Reneker, D.H. Beaded Nanofibers Formed during Electrospinning. Polymers 1999, 40, 4585–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.M.; Chiou, H.G.; Lin, S.L.; Lin, J.M. Effects of Electrostatic Polarity and the Types of Electrical Charging on Electrospinning Behavior. J Appl Polym Sci 2012, 126, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H. –W.; wang, M. Negative voltage electrospinning and positive voltage electrospinning of tissue engineering scaffolds: a comparative study and charge retention on scaffolds. Nano Life 2012, 02, 1250004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarin, A.L.; Kataphinan, W.; Reneker, D.H. Branching in Electrospinning of Nanofibers. J Appl Phys 2005, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Wu, T.; Dai, Y.; Xia, Y. Electrospinning and Electrospun Nanofibers: Methods, Materials, and Applications. Chem Rev 2019, 119, 5298–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.P.; Si, N.; Xu, L.; Liu, H.Y. Effect of Flow Rate on Diameter of Electrospun Nanoporous Fibers. Thermal Science 2014, 18, 1447–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogina, A. Electrospinning Process: Versatile Preparation Method for Biodegradable and Natural Polymers and Biocomposite Systems Applied in Tissue Engineering and Drug Delivery. Appl Surf Sci 2014, 296, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mit–Uppatham, C.; Nithitanakul, M.; Supaphol, P. Ultrafine Electrospun Polyamide–6 Fibers: Effect of Solution Conditions on Morphology and Average Fiber Diameter. Macromol Chem Phys 2004, 205, 2327–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vrieze, S.; Camp, T.; Nelvig, A.; Hagström, B.; Westbroek, P.; Clerck, K. The Effect of Temperature and Humidity on Electrospinning. J Mater Sci 2009, 44, 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.; Federici, J.; Imura, Y.; Catalani, L.H. Charge Generation, Charge Transport, and Residual Charge in the Electrospinning of Polymers: A Review of Issues and Complications. J Appl Phys 2012, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reneker, D.H.; Yarin, A.L.; Fong, H.; Koombhongse, S. Bending Instability of Electrically Charged Liquid Jets of Polymer Solutions in Electrospinning. J Appl Phys 2000, 87, 4531–4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhljar, L.É.; Ambrus, R. Electrospinning of Potential Medical Devices (Wound Dressings, Tissue Engineering Scaffolds, Face Masks) and Their Regulatory Approach. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reneker, D.H.; Yarin, A.L. Electrospinning Jets and Polymer Nanofibers. Polymer (Guildf) 2008, 49, 2387–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Steckl, A.J. Coaxial Electrospinning Formation of Complex Polymer Fibers and Their Applications. Chempluschem 2019, 84, 1453–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.H.; Wu, Y.; Zuo, W.W. Critical Length of Straight Jet in Electrospinning. Polymer (Guildf) 2005, 46, 12637–12640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzgo, M.; Mickova, A.; Doupnik, M.; Rampichova, M. Blend Electrospinning, Coaxial Electrospinning, and Emulsion Electrospinning Techniques. In Core–Shell Nanostructures for Drug Delivery and Theranostics: Challenges, Strategies and Prospects for Novel Carrier Systems. Elsevier 2018; 325–347. ISBN 9780081021989. [CrossRef]

- Cornejo Bravo, J.M.; Villarreal Gómez, L.J.; Serrano Medina, A. Electrospinning for Drug Delivery Systems: Drug Incorporation Techniques. In Electrospinning – Material, Techniques, and Biomedical Applications. InTech 2016, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, C.B.; Afghah, F.; Okan, B.S.; Yıldız, M.; Menceloglu, Y.; Culha, M.; Koc, B. Modeling 3D Melt Electrospinning Writing by Response Surface Methodology. Mater Des 2018, 148, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.H.; Duan, X.P.; Yan, X.; Yu, M.; Ning, X.; Zhao, Y.; Long, Y.Z. Recent Advances in Melt Electrospinning. RSC Adv 2016, 6, 53400–53414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.D.; Dalton, P.D.; Hutmacher, D.W. Melt Electrospinning Today: An Opportune Time for an Emerging Polymer Process. Prog Polym Sci 2016, 56, 116–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachs–Herrera, A.; Yousefzade, O.; Del Valle, L.J.; Puiggali, J. Melt Electrospinning of Polymers: Blends, Nanocomposites, Additives and Applications. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2021, 11, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, C. Preparation and Properties of PET/SiO 2 Composite Micro/Nanofibers by a Laser Melt–Electrospinning System. J Appl Polym Sci 2012, 125, 2050–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengsawas Surasarang, S.; Keen, J.M.; Huang, S.; Zhang, F.; McGinity, J.W.; Williams, R.O. Hot Melt Extrusion versus Spray Drying: Hot Melt Extrusion Degrades Albendazole. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 2017, 43, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, E.; Mros, S.; McConnell, M.; Cabral, J.D.; Ali, A. Melt–Electrowriting with Novel Milk Protein/PCL Biomaterials for Skin Regeneration. Biomedical Materials (Bristol) 2019, 14, 055013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutmacher, D.W.; Dalton, P.D. Melt Electrospinning. Chem Asian J 2011, 6, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, M.; Siamidi, A.; Kyriakou, S. Electrospinning and Drug Delivery. Electrospinning and electrospraying–techniques and applications 2019, 1–22, www.intechopen.com.

- Suganya, S.; Senthil Ram, T.; Lakshmi, B.S.; Giridev, V.R. Herbal Drug Incorporated Antibacterial Nanofibrous Mat Fabricated by Electrospinning: An Excellent Matrix for Wound Dressings. J Appl Polym Sci 2011, 121, 2893–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Bai, Y.; Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Du, Y.; Xu, L.; Yu, D.G.; Bligh, S.W.A. Recent Progress of Electrospun Herbal Medicine Nanofibers. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Song, W.; Xu, L.; Yu, D.G.; Bligh, S.W.A. A Review on Electrospun Poly(Amino Acid) Nanofibers and Their Applications of Hemostasis and Wound Healing. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El–Aassar, M.R.; Ibrahim, O.M.; Fouda, M.M.G.; El–Beheri, N.G.; Agwa, M.M. Wound Healing of Nanofiber Comprising Polygalacturonic/Hyaluronic Acid Embedded Silver Nanoparticles: In–Vitro and in–Vivo Studies. Carbohydr Polym 2020, 238, 116175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehetmeyer, G.; Meira, S.; Scheibel, J.; Silva, C.; Rodembusch, F.; Brandelli, A.; Soares, R. Biodegradable and Antimicrobial Films Based on Poly(Butylene Adipate–Co–Terephthalate) Electrospun Fibers. Polymer Bulletin 2017, 74, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yue, T.; Lee, T. ching Development of Pleurocidin–Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Electrospun Antimicrobial Nanofibers to Retain Antimicrobial Activity in Food System Application. Food Control 2015, 54, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, F.T.G.; Rempel, S.P.; Agnol, L.D.; Bianchi, O. The Main Blow Spun Polymer Systems: Processing Conditions and Applications. Journal of Polymer Research 2020, 27, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heseltine, P.L.; Hosken, J.; Agboh, C.; Farrar, D.; Homer–Vanniasinkam, S.; Edirisinghe, M. Fiber Formation from Silk Fibroin Using Pressurized Gyration. Macromol Mater Eng 2019, 304, 1800577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zussman, E.; Yarin, A.L.; Wendorff, J.H.; Greiner, A. Compound Core–Shell Polymer Nanofibers by Co–Electrospinning. Advanced Materials 2003, 15, 1929–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Huang, C.; Ke, Q.; He, C.; Wang, H.; Mo, X. Preparation and Characterization of Coaxial Electrospun Thermoplastic Polyurethane/Collagen Compound Nanofibers for Tissue Engineering Applications. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2010, 79, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelipenko, J.; Kocbek, P.; Kristl, J. Critical Attributes of Nanofibers: Preparation, Drug Loading, and Tissue Regeneration. Int J Pharm 2015, 484, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalf, A.; Madihally, S.V. Recent Advances in Multiaxial Electrospinning for Drug Delivery. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2017, 112, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, K.; Le, Y.; Mengen, H.; Zhongbo, L.; Zhulin, H. Effect of Solution Miscibility on the Morphology of Coaxial Electrospun Cellulose Acetate Nanofibers. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avossa, J.; Herwig, G.; Toncelli, C.; Itel, F.; Rossi, R.M. Electrospinning Based on Benign Solvents: Current Definitions, Implications and Strategies. Green Chemistry 2022, 24, 2347–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. X. Zhang D. Chen, S.J.W.; Zhu, K.J. Optimizing Double Emulsion Process to Decrease the Burst Release of Protein from Biodegradable Polymer Microspheres. J Microencapsul 2005, 22, 413–422. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.M.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Kotaki, M.; Ramakrishna, S. A Review on Polymer Nanofibers by Electrospinning and Their Applications in Nanocomposites. Compos Sci Technol 2003, 63, 2223–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinatangkul, N.; Limmatvapirat, C.; Limmatvapirat, S. Electrospun Nanofibers from Natural Polymers and Their Application. Science, Engineering and Health Studies. Science, Engineering and Health Studies 2021, 21010005–21010005.

- Wray, L.S.; Hu, X.; Gallego, J.; Georgakoudi, I.; Omenetto, F.G.; Schmidt, D.; Kaplan, D.L. Effect of Processing on Silk–Based Biomaterials: Reproducibility and Biocompatibility. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2011, 99 B, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Baughman, C.B.; Kaplan, D.L. In Vitro Evaluation of Electrospun Silk Fibroin Scaffolds for Vascular Cell Growth. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2217–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Cao, C.; Ma, X.; Lin, J. Electrospinning of Silk Fibroin and Collagen for Vascular Tissue Engineering. Int J Biol Macromol 2010, 47, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, H.; Fan, Y. Silk Fibroin for Vascular Regeneration. Microsc Res Tech 2017, 80, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalamak, S.; Erdoǧdu, C.; Özalp, M.; Ulubayram, K. Silk Fibroin Based Antibacterial Bionanotextiles as Wound Dressing Materials. Materials Science and Engineering C 2014, 43, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.P.; Reagan, M.R.; Bohara, R.A. Silk Fibroin and Silk–Based Biomaterial Derivatives for Ideal Wound Dressings. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 164, 4613–4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.J.; Gogoi, D.; Chutia, J.; Kandimalla, R.; Kalita, S.; Kotoky, J.; Chaudhari, Y.B.; Khan, M.R.; Kalita, K. Controlled Antibiotic–Releasing Antheraea Assama Silk Fibroin Suture for Infection Prevention and Fast Wound Healing. Surgery (United States) 2016, 159, 539–547. [CrossRef]

- Tuwalska, A.; Grabska–Zielińska, S.; Sionkowska, A. Chitosan/Silk Fibroin Materials for Biomedical Applications— A Review. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonesi, M.; Garcia–Nieto, M.; Guinea, G.V.; Panetsos, F.; Pérez–Rigueiro, J.; González–Nieto, D. Silk Fibroin: An Ancient Material for Repairing the Injured Nervous System. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadpour, S.; Kargozar, S.; Moradi, L.; Ai, A.; Nosrati, H.; Ai, J. Natural Biomacromolecule Based Composite Scaffolds from Silk Fibroin, Gelatin and Chitosan toward Tissue Engineering Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 154, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farokhi, M.; Mottaghitalab, F.; Samani, S.; Shokrgozar, M.A.; Kundu, S.C.; Reis, R.L.; Fatahi, Y.; Kaplan, D.L. Silk Fibroin/Hydroxyapatite Composites for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biotechnol Adv 2018, 36, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.S.; Rather, A.H.; Wani, T.U.; Rather, S. ullah; Abdal–hay, A.; Sheikh, F.A. A Comparative Review on Silk Fibroin Nanofibers Encasing the Silver Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agents for Wound Healing Applications. Mater Today Commun 2022, 32, 103914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phamornnak, C.; Han, B.; Spencer, B.F.; Ashton, M.D.; Blanford, C.F.; Hardy, J.G.; Blaker, J.J.; Cartmell, S.H. Instructive Electroactive Electrospun Silk Fibroin–Based Biomaterials for Peripheral Nerve Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials Advances 2022, 141, 213094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoulders, M.; Raines, R. Collagen Structure and Stability. Annu Rev Biochem 2009, 78, 929–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, F. 0; Levine, L.; Drake, M.P.; Rubin, A.L.; Pfahl, $ D.; Davison, P.F. The antigenicity of tropocollagen. Bull. Soc. Chim. Biol. (France) 1964, 51; 493–497, https://www.pnas.org.

- Parenteau–Bareil, R.; Gauvin, R.; Berthod, F. Collagen–Based Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering Applications. Materials 2010, 3, 1863–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, A.K.; Yannas, I.V.; Bonfield, W. Antigenicity and Immunogenicity of Collagen. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2004, 71, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Singla, A.; Lee, Y. Biomedical Applications of Collagen. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2001, 221, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.V.M.; Serricella, P.; Linhares, A.B.R.; Guerdes, R.M.; Borojevic, R.; Rossi, M.A.; Duarte, M.E.L.; Farina, M. Characterization of a Bovine Collagen–Hydroxyapatite Composite Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4987–4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Yoo, J.J.; Atala, A. ACELLULAR COLLAGEN MATRIX AS A POSSIBLE “OFF THE SHELF” BIOMATERIAL FOR URETHRAL REPAIR. Urology 1999, 54, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Raines, R.T. Review Collagen–Based Biomaterials for Wound Healing. Biopolymers 2014, 101, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doillon, C.J.; Whyne, C.F.; Brandwein, S.; Silver, F.H. Collagen-based Wound Dressings: Control of the Pore Structure and Morphology. J Biomed Mater Res 1986, 20, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, D.W. A Review of Collagen and Collagen–Based Wound Dressings. Wounds 2008, 20, 347–356. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281848414.

- Kon, E.; Delcogliano, M.; Filardo, G.; Busacca, M.; Di Martino, A.; Marcacci, M. Novel Nano–Composite Multilayered Biomaterial for Osteochondral Regeneration: A Pilot Clinical Trial. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2011, 39, 1180–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankajakshan, D.; Voytik–Harbin, S.L.; Nör, J.E.; Bottino, M.C. Injectable Highly Tunable Oligomeric Collagen Matrices for Dental Tissue Regeneration. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2020, 3, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García–Hernández, A.B.; Morales–Sánchez, E.; Berdeja–Martínez, B.M.; Escamilla–García, M.; Salgado–Cruz, M.P.; Rentería–Ortega, M.; Farrera–Rebollo, R.R.; Vega–Cuellar, M.A.; Calderón–Domínguez, G. PVA–Based Electrospun Biomembranes with Hydrolyzed Collagen and Ethanolic Extract of Hypericum Perforatum for Potential Use as Wound Dressing: Fabrication and Characterization. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodjo Boady Djagny, Z.W.; Xu, S. Gelatin: A Valuable Protein for Food and Pharmaceutical Industries: Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2001, 41, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzoghby, A.O. Gelatin–Based Nanoparticles as Drug and Gene Delivery Systems: Reviewing Three Decades of Research. Journal of Controlled Release 2013, 172, 1075–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echave, M.C.; Sánchez, P.; Pedraz, J.L.; Orive, G. Progress of Gelatin–Based 3D Approaches for Bone Regeneration. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2017, 42, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, A.; Madjd, Z.; Pezeshki–Modaress, M.; Khosrowpour, Z.; Farshi, P.; Eini, L.; Kiani, J.; Seifi, M.; Kundu, S.C.; Ghods, R.; et al. Bioengineering of Fibroblast–Conditioned Polycaprolactone/Gelatin Electrospun Scaffold for Skin Tissue Engineering. Artif Organs 2022, 46, 1040–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, S.; Sharma, C.; Purohit, S.D.; Singh, H.; Dinda, A.K.; Potdar, P.D.; Chou, C.F.; Mishra, N.C. Gelatin–Polycaprolactone–Nanohydroxyapatite Electrospun Nanocomposite Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering. Materials Science and Engineering C 2021, 119, 111588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Shafiei, S.S.; Sabouni, F. Electrospun Nanofibrous Scaffolds of Polycaprolactone/Gelatin Reinforced with Layered Double Hydroxide Nanoclay for Nerve Tissue Engineering Applications. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 28351–28360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhuang, S. Chitosan–Based Materials: Preparation, Modification and Application. J Clean Prod 2022, 355, 131825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K. Chitin, Chitosan, Oligosaccharides and Their Derivatives: Biological Activities and Applications. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Arbia, W.; Arbia, L.; Adour, L.; Amrane, A. Chitin Extraction from Crustacean Shells Using Biological Methods –A Review. Food Technol Biotechnol 2013, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Meng, Q.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhou, M.; Jin, Z.; Zhao, K. Chitosan Derivatives and Their Application in Biomedicine. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavoni, J.M.F.; Luchese, C.L.; Tessaro, I.C. Impact of Acid Type for Chitosan Dissolution on the Characteristics and Biodegradability of Cornstarch/Chitosan Based Films. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 138, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, B.; Owczarek, A.; Nadolna, K.; Sionkowska, A. The Film–Forming Properties of Chitosan with Tannic Acid Addition. Mater Lett 2019, 245, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritchenkov, A.S.; Egorov, A.R.; Kurasova, M.N.; Volkova, O.V.; Meledina, T.V.; Lipkan, N.A.; Tskhovrebov, A.G.; Kurliuk, A.V.; Shakola, T.V.; Dysin, A.P.; et al. Novel Non–Toxic High Efficient Antibacterial Azido Chitosan Derivatives with Potential Application in Food Coatings. Food Chem 2019, 301, 125247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balagangadharan, K.; Dhivya, S.; Selvamurugan, N. Chitosan Based Nanofibers in Bone Tissue Engineering. Int J Biol Macromol 2017, 104, 1372–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.M.; Shahruzzaman, M.; Biswas, S.; Nurus Sakib, M.; Rashid, T.U. Chitosan Based Bioactive Materials in Tissue Engineering Applications–A Review. Bioact Mater 2020, 5, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Jia, C.; Qiao, X.; Liu, T.; Sun, K. Silk Fibroin Microfibers and Chitosan Modified Poly (Glycerol Sebacate) Composite Scaffolds for Skin Tissue Engineering. Polym Test 2017, 62, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanath, V.; Pramanik, K.; Biswas, A. Optimization and Evaluation of Silk Fibroin–Chitosan Freeze–Dried Porous Scaffolds for Cartilage Tissue Engineering Application. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2016, 27, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezeshki–Modaress, M.; Zandi, M.; Rajabi, S. Tailoring the Gelatin/Chitosan Electrospun Scaffold for Application in Skin Tissue Engineering: An in Vitro Study. Prog Biomater 2018, 7, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, D.R.; Biswal, T. Alginate and Its Application to Tissue Engineering. SN Appl Sci 2021, 3, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarsan, S.; Franklin, D.S.; Guhanathan, S. Imbibed Salts and PH–Responsive Behaviours of Sodium Alginate Based Eco–Friendly Biopolymeric Hydrogels–A Solventless Approach. MMAIJ 2015, 11, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Clementi, F. Alginate Production by Azotobacter Vinelandii. Crit Rev Biotechnol 1997, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govan, J.R.W.; Fyfe, J.A.M.; Jarman, T.R. Isolation of Alginate–Producing Mutants of Pseudomonas Fluorescens, Pseudomonas Putida and Pseudomonas Mendocina. J Gen Microbiol 1981, 125, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, M.Y.; Shafiq, M.; Li, H.Y.; Hashim, R.; EL–Newehy, M.; EL–Hamshary, H.; Morsi, Y.; Mo, X. Synthesis of Oxidized Sodium Alginate and Its Electrospun Bio–Hybrids with Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles to Promote Wound Healing. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 232, 123480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiabbas, M.; Alemzadeh, I.; Vossoughi, M. A Porous Hydrogel–Electrospun Composite Scaffold Made of Oxidized Alginate/Gelatin/Silk Fibroin for Tissue Engineering Application. Carbohydr Polym 2020, 245, 116465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.T.; Auras, R.; Rubino, M. Processing Technologies for Poly(Lactic Acid). Progress in Polymer Science (Oxford) 2008, 33, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, R.P.; Tekale, S.U.; Shisodia, S.U.; Totre, J.T.; Domb, A.J. Biomedical Applications of Poly(Lactic Acid). Recent Pat Regen Med 2014, 4, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Zhang, J.X.; Song, Z.; Varshney, S.K. Thermal Properties of Polylactides: Effect of Molecular Mass and Nature of Lactide Isomer. In Proceedings of the Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2009, 95, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wang, W.; Hu, J.; Wan, J.; Cui, L. Effect of Mixed Solvents on the Structure and Properties of PLLA/PDLA Electrospun Fibers. Fibers and Polymers 2020, 21, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Huang, X.B.; Cai, X.M.; Lu, J.; Yuan, J.; Shen, J. The Influence of Fiber Diameter of Electrospun Poly(Lactic Acid) on Drug Delivery. Fibers and Polymers 2012, 13, 1120–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Mele, E. Effect of Antibacterial Plant Extracts on the Morphology of Electrospun Poly(Lactic Acid) Fibres. Materials 2018, 11, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.P.; López, J.; López, D.; Kenny, J.M.; Peponi, L. Development of Flexible Materials Based on Plasticized Electrospun PLA–PHB Blends: Structural, Thermal, Mechanical and Disintegration Properties. Eur Polym J 2015, 73, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, L.; New, J.; Dasari, A.; Yu, S.; Manan, M.A. Surface Morphology of Electrospun PLA Fibers: Mechanisms of Pore Formation. RSC Adv 2014, 4, 44082–44088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Xu, L.; Ahmed, A. Batch Preparation and Characterization of Electrospun Porous Polylactic Acid–Based Nanofiber Membranes for Antibacterial Wound Dressing. Advanced Fiber Materials 2022, 4, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Ghosh, C.; Hwang, S.G.; Chanunpanich, N.; Park, J.S. Porous Core/Sheath Composite Nanofibers Fabricated by Coaxial Electrospinning as a Potential Mat for Drug Release System. Int J Pharm 2012, 439, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casasola, R.; Thomas, N.L.; Trybala, A.; Georgiadou, S. Electrospun Poly Lactic Acid (PLA) Fibres: Effect of Different Solvent Systems on Fibre Morphology and Diameter. Polymer (Guildf) 2014, 55, 4728–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, F.S.; Khoddami, A.; Avinc, O. Poly (Lactic Acid) Nano–Fibers as Drug–Delivery Systems: Opportunities and Challenges. Nanomedicine Research Journal 2019, 4, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumine, H.; Sasaki, R.; Yamato, M.; Okano, T.; Sakurai, H. A Polylactic Acid Non–Woven Nerve Conduit for Facial Nerve Regeneration in Rats. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2014, 8, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgia, D.; Mauceri, R.; Campisi, G.; De Caro, V. Advance on Resveratrol Application in Bone Regeneration: Progress and Perspectives for Use in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, H.; Azimi, B.; Ismaeilimoghadam, S.; Danti, S. Poly(Lactic Acid)–Based Electrospun Fibrous Structures for Biomedical Applications. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2022, 12, 3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samokhin, Y.; Varava, Y.; Diedkova, K.; Yanko, I.; Husak, Y.; Radwan–Pragłowska, J.; Pogorielova, O.; Janus, Ł.; Pogorielov, M.; Korniienko, V. Fabrication and Characterization of Electrospun Chitosan/Polylactic Acid (CH/PLA) Nanofiber Scaffolds for Biomedical Application. J Funct Biomater 2023, 14, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.F.; Andriyana, A.; Muhamad, F.; Ang, B.C. Fabrication of Poly(Lactic Acid)–Cellulose Acetate Core–Shell Electrospun Fibers with Improved Tensile Strength and Biocompatibility for Bone Tissue Engineering. Journal of Polymer Research 2023, 30, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachewicz, U.; Qiao, T.; Rawlinson, S.C.F.; Almeida, F.V.; Li, W.Q.; Cattell, M.; Barber, A.H. 3D Imaging of Cell Interactions with Electrospun PLGA Nanofiber Membranes for Bone Regeneration. Acta Biomater 2015, 27, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisson, A.L.; Ekinci, D.; Lendlein, A. The Contemporary Role of ε–Caprolactone Chemistry to Create Advanced Polymer Architectures. Polymer 2013, 54, 4333–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neppalli, R.; Marega, C.; Marigo, A.; Bajgai, M.P.; Kim, H.Y.; Causin, V. Poly(ε–Caprolactone) Filled with Electrospun Nylon Fibres: A Model for a Facile Composite Fabrication. Eur Polym J 2010, 46, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghomi, E.R.; Lakshminarayanan, R.; Chellappan, V.; Verma, N.K.; Chinnappan, A.; Neisiany, R.E.; Amuthavalli, K.; Poh, Z.S.; Wong, B.H.S.; Dubey, N.; et al. Electrospun Aligned PCL/Gelatin Scaffolds Mimicking the Skin ECM for Effective Antimicrobial Wound Dressings. Advanced Fiber Materials 2023, 5, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shie Karizmeh, M.; Poursamar, S.A.; Kefayat, A.; Farahbakhsh, Z.; Rafienia, M. An in Vitro and in Vivo Study of PCL/Chitosan Electrospun Mat on Polyurethane/Propolis Foam as a Bilayer Wound Dressing. Biomaterials Advances 2022, 135, 112667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, D.; Xia, D.; Liang, C.; Li, N.; Xu, R. Synergistic Effect of Co–Delivering Ciprofloxacin and Tetracycline Hydrochloride for Promoted Wound Healing by Utilizing Coaxial PCL/Gelatin Nanofiber Membrane. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitxelena–Iribarren, O.; Riera–Pons, M.; Pereira, S.; Calero–Castro, F.J.; Castillo Tuñón, J.M.; Padillo–Ruiz, J.; Mujika, M.; Arana, S. Drug–Loaded PCL Electrospun Nanofibers as Anti–Pancreatic Cancer Drug Delivery Systems. Polymer Bulletin 2023, 80, 7763–7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroosh, H.J.; Dong, Y.; Jasim, S.; Ramakrishna, S. Morphological Structures and Drug Release Effect of Multiple Electrospun Nanofibre Membrane Systems Based on PLA, PCL, and PCL/Magnetic Nanoparticle Composites. J Nanomater 2022, 5190163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskitoros–Togay, M.; Bulbul, Y.E.; Tort, S.; Demirtaş Korkmaz, F.; Acartürk, F.; Dilsiz, N. Fabrication of Doxycycline–Loaded Electrospun PCL/PEO Membranes for a Potential Drug Delivery System. Int J Pharm 2019, 565, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbasizadeh, B.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Kobarfard, F.; Jaafari, M.R.; Hashemi, A.; Farhadnejad, H.; Feyzi–barnaji, B. Electrospun Doxorubicin–Loaded PEO/PCL Core/Sheath Nanofibers for Chemopreventive Action against Breast Cancer Cells. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2021, 64, 102576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, Z.; Mohebbi–Kalhori, D.; Afarani, M.S. Engineered Electrospun Polycaprolactone (PCL)/Octacalcium Phosphate (OCP) Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering. Materials Science and Engineering C 2017, 81, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shi, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, K.; Ullah, I.; Cheng, P. Electrospinning of Polycaprolactone Nanofibers Using H2O as Benign Additive in Polycaprolactone/Glacial Acetic Acid Solution. J Appl Polym Sci 2018, 135, 45578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsogiannis, K.A.G.; Vladisavljević, G.T.; Georgiadou, S. Porous Electrospun Polycaprolactone (PCL) Fibres by Phase Separation. Eur Polym J 2015, 69, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

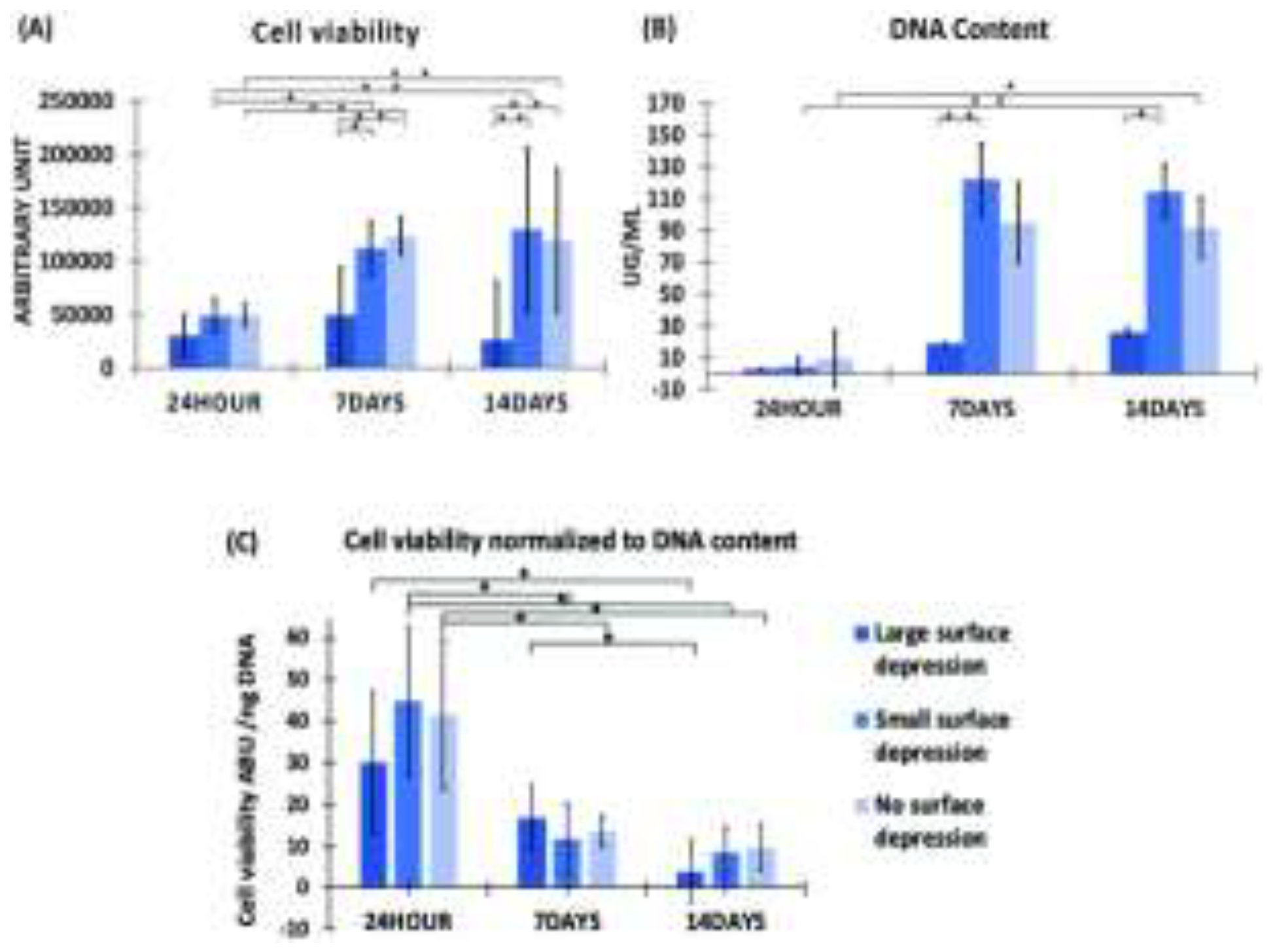

- Gao, Y.; Callanan, A. Influence of Surface Topography on PCL Electrospun Scaffolds for Liver Tissue Engineering. J Mater Chem B 2021, 9, 8081–8093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heikkilä, P.; Harlin, A. Parameter Study of Electrospinning of Polyamide–6. Eur Polym J 2008, 44, 3067–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, S.Y.; Lin, H.S.; Cheng, P.J.; Huang, C.L.; Wu, J.Y.; Wang, C. Rheological Aspect on Electrospinning of Polyamide 6 Solutions. Eur Polym J 2013, 49, 3619–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Wang, L.; Xu, M.; Qin, M.; Zhao, L.; Wei, Y.; Hu, Y.; Lian, X.; Liang, Z.; Chen, S.; et al. Electrospun Polyamide–6/Chitosan Nanofibers Reinforced Nano–Hydroxyapatite/Polyamide–6 Composite Bilayered Membranes for Guided Bone Regeneration. Carbohydr Polym 2021, 260, 117769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma Nur, P.; Pınar, T.; Uğur, P.; Ayşenur, Y.; Murat, E.; Kenan, Y. Fabrication of Polyamide 6/Honey/Boric Acid Mats by Electrohydrodynamic Processes for Wound Healing Applications. Mater Today Commun 2021, 29, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X. Preparation of Polyamide 6/CeO2 Composite Nanofibers through Electrospinning for Biomedical Applications. Int J Polym Sci 2019, 2494586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.K.S.; Sandeep, K.; Singh, M.; Singh, G.P.; Lee, J.K.; Bhatia, S.K.; Kalia, V.C. Biotechnological Application of Polyhydroxyalkanoates and Their Composites as Anti–Microbials Agents. In Biotechnological Applications of Polyhydroxyalkanoates 2019, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urtuvia, V.; Villegas, P.; Fuentes, S.; González, M.; Seeger, M. Burkholderia Xenovorans LB400 Possesses a Functional Polyhydroxyalkanoate Anabolic Pathway Encoded by the Pha Genes and Synthesizes Poly(3–Hydroxybutyrate) under Nitrogen–Limiting Conditions. International Microbiology 2018, 21, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.; Cao, R.; Hua, D.H.; Li, P. Study of Class i and Class III Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Synthases with Substrates Containing a Modified Side Chain. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudhoo, A.; Sharma, S.K. A Handbook of Applied Biopolymer Technology: Synthesis, Degradation and Applications. RSC Green Chemistry 2011; 12.

- Chen, G.Q.; Wu, Q. The Application of Polyhydroxyalkanoates as Tissue Engineering Materials. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 6565–6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, R.; Keshavarz, T.; Roether, J.A.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Roy, I. Medium Chain Length Polyhydroxyalkanoates, Promising New Biomedical Materials for the Future. Materials Science and Engineering R: Reports 2011, 72, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudesh, K.; Lee, Y. –F.; Sridewi, N.; Ramanathan, S. The Influence of Electrospinning Parameters and Drug Loading on Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Nanofibers for Drug Delivery. Int J Biotechnol Wellness Ind 2016, 4, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cicek, N.; Levin, D.B.; Logsetty, S.; Liu, S. Bacteria–Triggered Release of a Potent Biocide from Core–Shell Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA)–Based Nanofibers for Wound Dressing Applications. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2020, 31, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandayuthapani, B.; Yoshida, Y.; Maekawa, T.; Kumar, D.S. Polymeric Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering Application: A Review. Int J Polym Sci 2011, 290602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdil, D.; Aydin, H.M. Polymers for Medical and Tissue Engineering Applications. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology 2014, 89, 1793–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Chantre, C.O.; Gannon, A.R.; Lind, J.U.; Campbell, P.H.; Grevesse, T.; O’Connor, B.B.; Parker, K.K. Soy Protein/Cellulose Nanofiber Scaffolds Mimicking Skin Extracellular Matrix for Enhanced Wound Healing. Adv Healthc Mater 2018, 7, 1701175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, D.; Janani, G.; Chakraborty, B.; Nandi, S.K.; Mandal, B.B. Functionalized PVA–Silk Blended Nanofibrous Mats Promote Diabetic Wound Healing via Regulation of Extracellular Matrix and Tissue Remodelling. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2018, 12, e1559–e1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Tian, L.; Prabhakaran, M.P.; Ding, X.; Ramakrishna, S. Fabrication of Nerve Growth Factor Encapsulated Aligned Poly(ε–Caprolactone) Nanofibers and Their Assessment as a Potential Neural Tissue Engineering Scaffold. Polymers (Basel) 2016, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijeńska, E.; Prabhakaran, M.P.; Swieszkowski, W.; Kurzydlowski, K.J.; Ramakrishna, S. Electrospun Bio–Composite P(LLA–CL)/Collagen I/Collagen III Scaffolds for Nerve Tissue Engineering. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2012, 100 B, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Tang, D.; Liu, X.; Meng, J.; Wei, W.; Gong, R.H.; Li, J. Heterogeneous Porous PLLA/PCL Fibrous Scaffold for Bone Tissue Regeneration. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 235, 123781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethinam, S.; Basaran, B.; Vijayan, S.; Mert, A.; Bayraktar, O.; Aruni, A.W. Electrospun Nano–Bio Membrane for Bone Tissue Engineering Application– a New Approach. Mater Chem Phys 2020, 249, 123010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).