Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

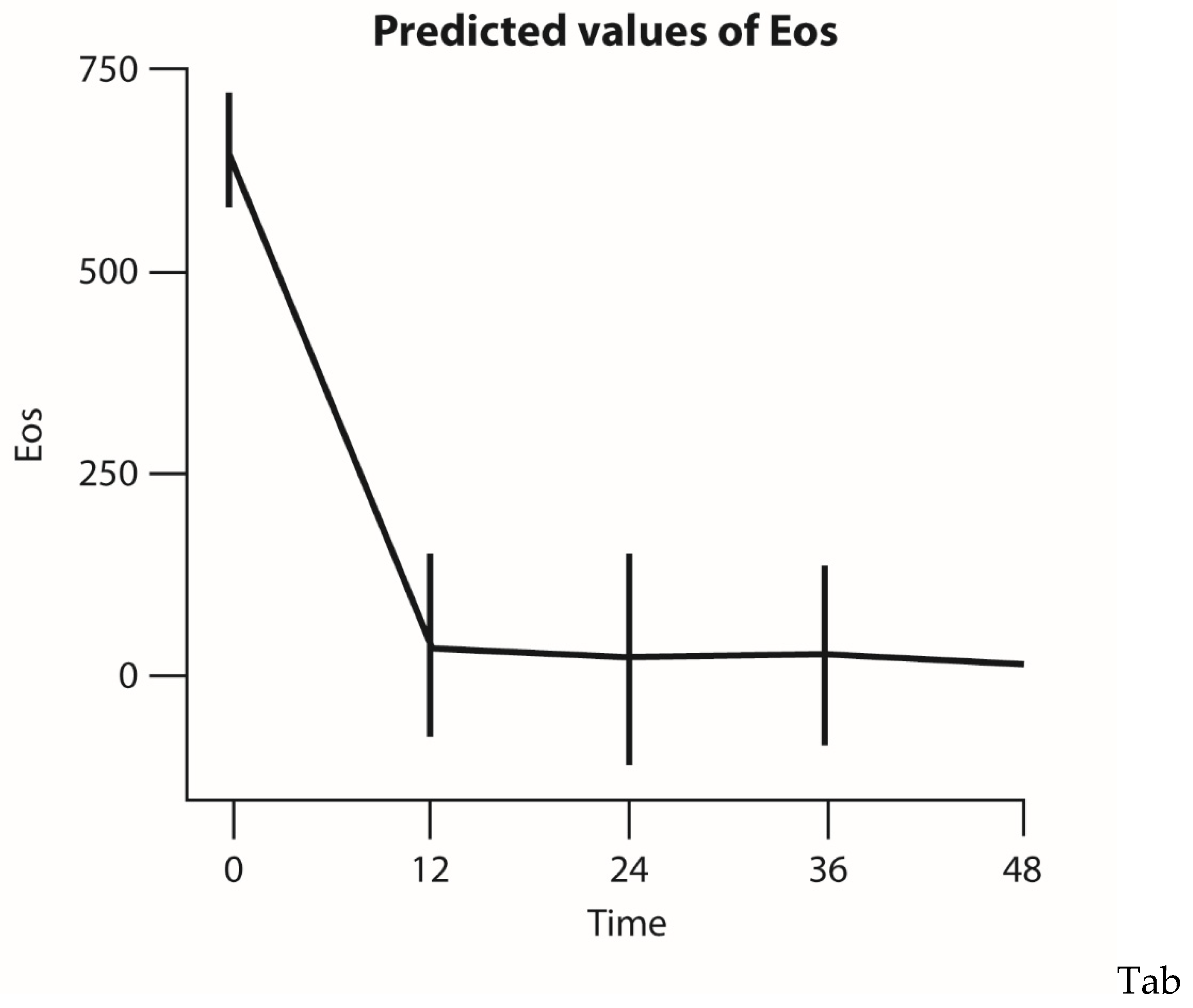

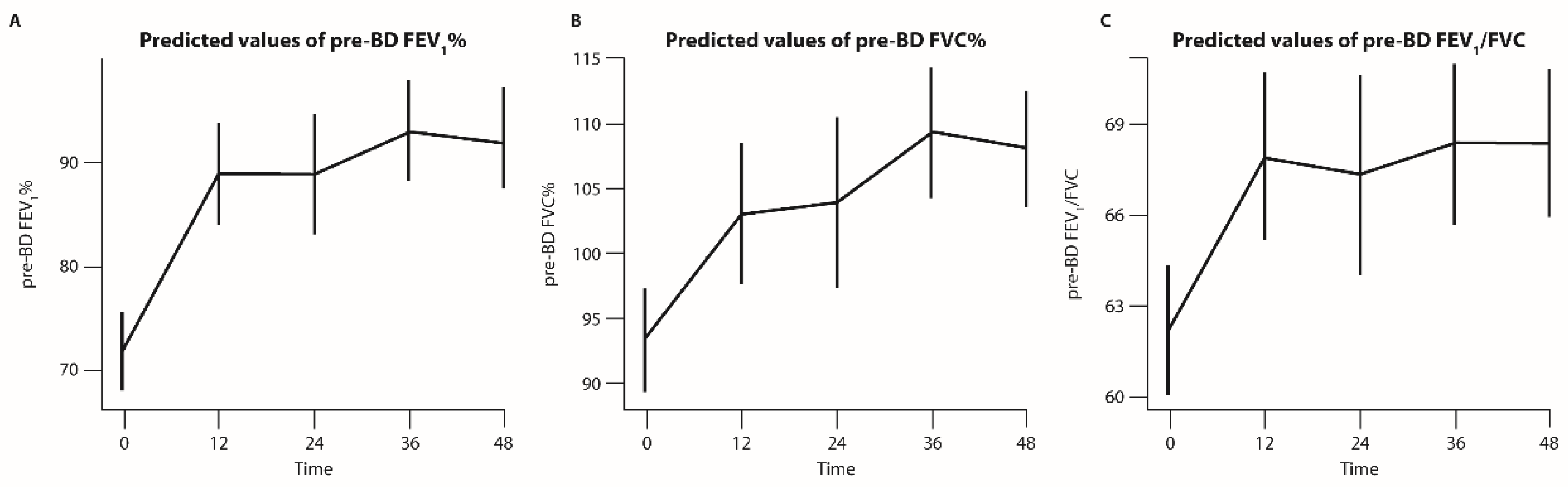

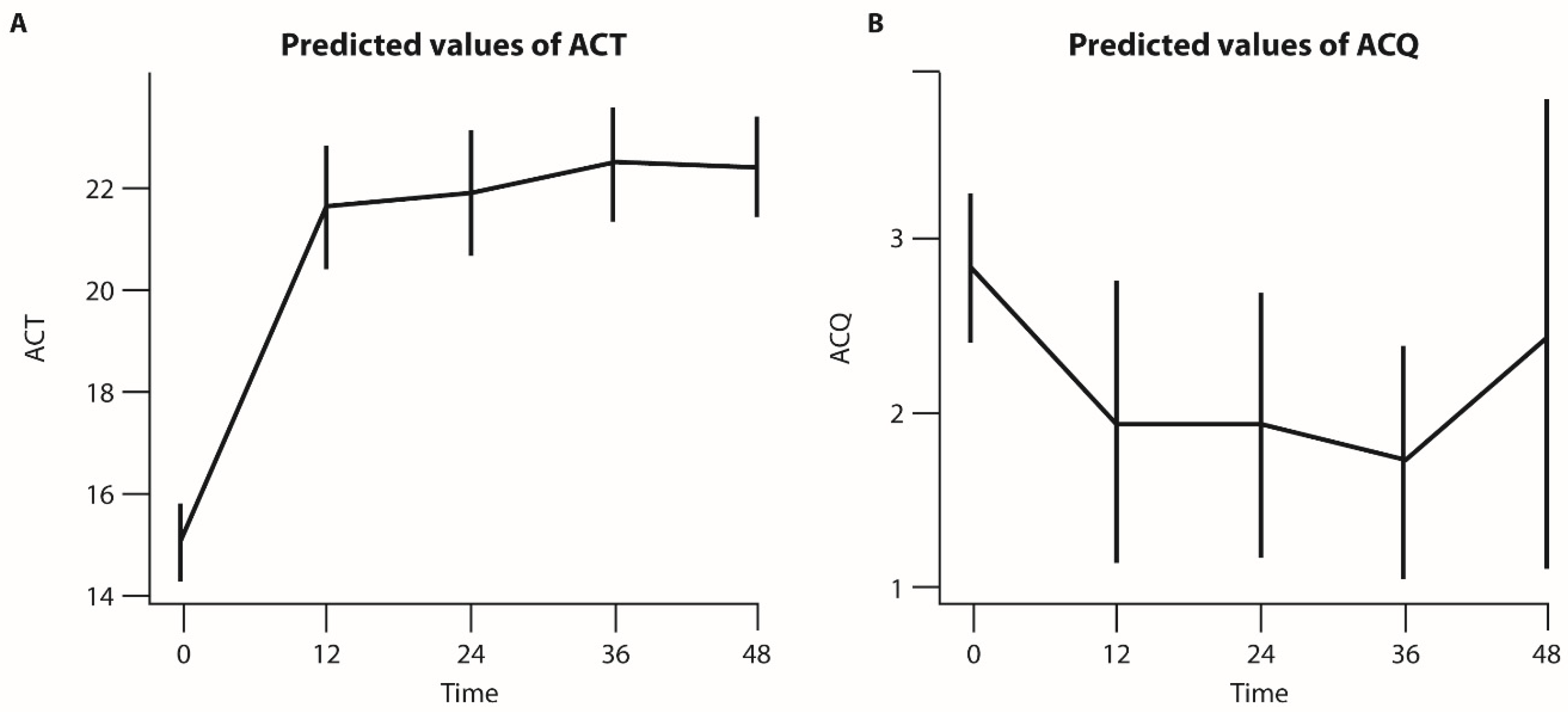

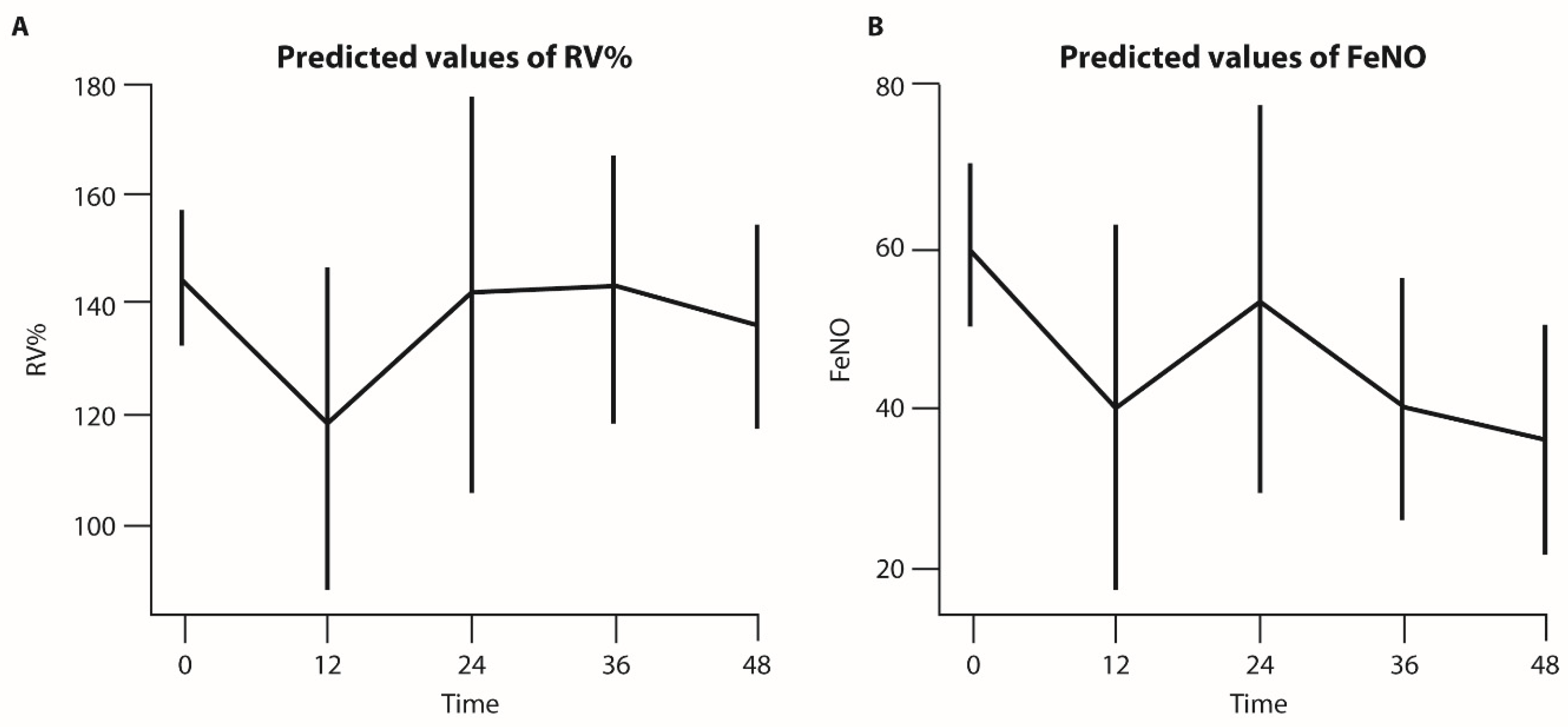

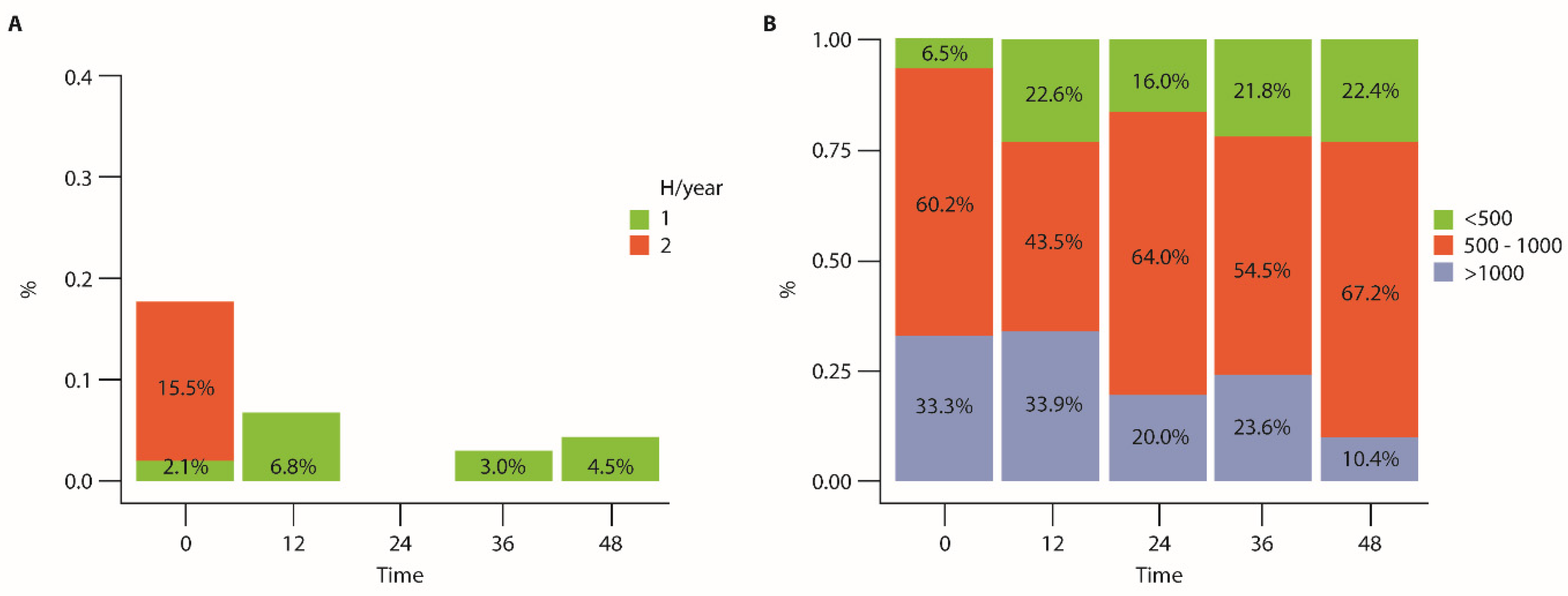

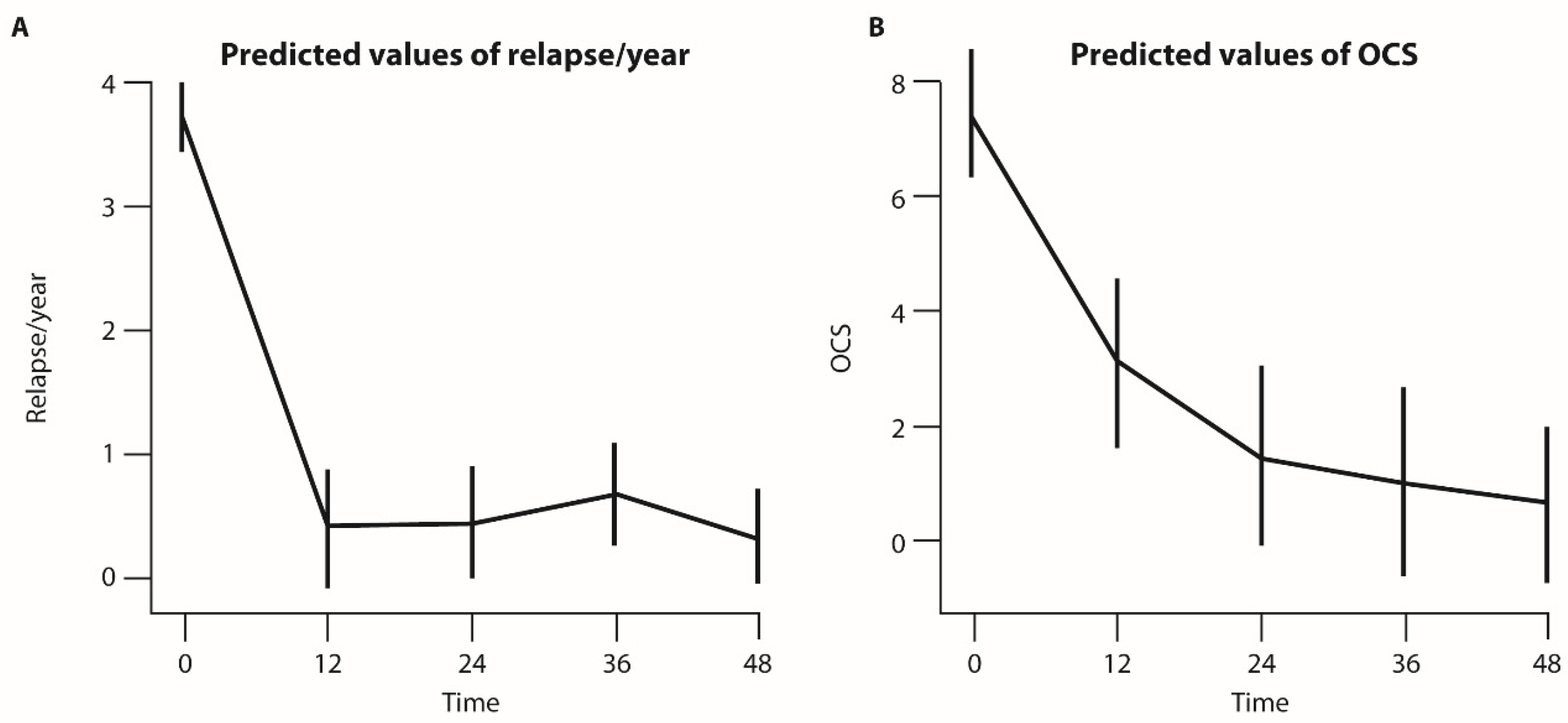

Background/Objectives: Benralizumab is an anti-IL-5 receptor alpha monoclonal antibody that induces near-complete depletion of eosinophils. This study aimed to evaluate the long-term safety and effectiveness of benralizumab in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma (SEA) over a 48-month period. Methods: This was a single-arm, retrospective, observational, multicenter study involving 123 SEA patients treated with benralizumab at a dosage of 30 mg every 4 weeks for the first three doses and then every 8 weeks. The safety endpoints focused on the frequency and nature of adverse events and the likelihood that they were induced by benralizumab. The efficacy endpoints focused on lung function, asthma exacerbations and control, and oral corticosteroid use. Results: Benralizumab, consistent with its mechanism of action, led to rapid and nearly complete depletion of eosinophils. In total, 26 adverse events (21.1%) were observed, with 1.6% related to the treatment and 0.8% categorized as serious (vagal hypotension). Bronchitis was the most common unrelated adverse event (15.4%), occurring between months 36 and 38. Of note, benralizumab maintained its effectiveness over the 48-month period, resulting in significant improvements in lung function and reductions in oral corticosteroid use and exacerbation frequency. Conclusions: Benralizumab demonstrated a favorable safety profile comparable to previously published studies with perdurable effectiveness in controlling SEA and reducing oral corticosteroid use. Finally, this study provides evidence that near-complete eosinophil depletion does not increase long-term safety risks and supports benralizumab as a reliable treatment option for SEA patients.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Study Design and Study Intervention

2.3. Patients

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Analysis of Safety and Efficacy Endpoints

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Population Enrolled in the Study

3.2. Safety Outcomes of Depleting Eosinophils with Benralizumab

3.3. Comparison of Safety Data from Clinical Trials and Pharmacovigilance

3.4. Effectiveness Endpoints

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments and funding

Ethics and consent

Data availability statement

Competing interests

References

- Akenroye A, Shen L, Namazy JA. Comparative efficacy of mepolizumab, benralizumab, and dupilumab in eosinophilic asthma: A Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;150(5):1097–1105.e12. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Benralizumab SPC. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2018/20180108139598/anx_139598_en.pdf [Accessed 2024 Sep 8].

- Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, Chanez P, Papi A, Weinstein SF, Barker P, Sproule S, Gilmartin G, Aurivillius M, Werkström V, Goldman M. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β2-agonists (SIROCCO): A randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2115–2127. [CrossRef]

- Boada-Fernández-Del-Campo C, García-Sánchez-Colomer M, Fernández-Quintana E, Poza-Guedes P, Rolingson-Landaeta JL, Sánchez-Machín I, González-Pérez R. Real-world safety profile of biologic drugs for severe uncontrolled asthma: A descriptive analysis from the Spanish Pharmacovigilance Database. J Clin Med. 2024;13(13):4192. [CrossRef]

- Bumbacea D, Campbell D, Nguyen N, Barnes PJ, Robinson D. Parameters associated with persistent airflow obstruction in chronic severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2004;24(1):122–8. [CrossRef]

- Busse WW, Korn S, Brockhaus F, Lombard L, Newbold P, McDonald M, Wehrman A, Goldman M. Long-term safety and efficacy of benralizumab in patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma: 1-year results from the BORA phase 3 extension trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(1):46–59. [CrossRef]

- Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, Bush A, Castro M, Sterk PJ, Adcock IM, Bateman ED, Bel EH, Bleecker ER, Boulet LP, Brightling C, Chanez P, Dahlen SE, Djukanovic R, Frey U, Gaga M, Gibson P, Hamid Q, Jajour NN, Mauad T, Sorkness RL, Teague WG. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):343–73. [CrossRef]

- Contoli M, Papi A, Brindicci C, Caminati M, Guerriero M, Licini A, Scurati S, Panico S, Fabbri L, Bagnasco D, Canonica GW. Effects of anti-IL5 biological treatments on blood IgE levels in severe asthmatic patients: A real-life multicentre study (BIONIGE). Clin Transl Allergy. 2022;12. [CrossRef]

- Couillard S, Boulet LP, Bergeron C, Laviolette M, Brault C, Bélanger A, Rousseau S, Chakir J. Choosing the right biologic for the right patient with severe asthma. Chest. 2024;S0012-3692. [CrossRef]

- Cutroneo PM, Bendandi B, D'Angelo V, Foti C, Casciaro M, Crimi C, Ventura MT, Vitiello P, Colombo P. Safety of biological therapies for severe asthma: An analysis of suspected adverse reactions reported in the WHO pharmacovigilance database. BioDrugs. 2024;38(5):425–48. [CrossRef]

- Dunican EM, Fahy JV. Asthma and corticosteroids: Time for a more precise approach to treatment. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(5):1701167. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo RT, Neves JS. Eosinophils in fungal diseases: An overview. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;104(1):49–60. [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, Korn S, Ohta K, O'Byrne PM, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Seibold W, Katelaris CH, Ohta K, Werkström V, Aurivillius M, Goldman M, Lee J. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2128–41. [CrossRef]

- Ghazi A, Trikha A, Calhoun WJ. Benralizumab—A humanized mAb to IL-5Rα with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity—A novel approach for the treatment of asthma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12(1):113–8. [CrossRef]

- Harrison TW, Jackson DJ, Wenzel SE, FitzGerald JM, Bourdin A, Zangrilli JG, Gilmartin G, Goldman M, Aurivillius M. Onset of effect and impact on health-related quality of life, exacerbation rate, lung function, and nasal polyposis symptoms for patients with severe eosinophilic asthma treated with benralizumab (ANDHI): A randomised, controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(3):260–74. [CrossRef]

- Hekking PW, Wener RR, Amelink M, Zwinderman AH, Bouvy ML, Bel EH. The prevalence of severe refractory asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(4):896–902. [CrossRef]

- Jackson DJ, Korn S, Mathur SK, Barker P, Meka VG, Martin UJ, Zangrilli JG. Safety of eosinophil-depleting therapy for severe eosinophilic asthma: Focus on benralizumab. Drug Saf. 2020;43(5):409–25. [CrossRef]

- Jackson DJ, Pavord ID. Living without eosinophils: Evidence from mouse and man. Eur Respir J. 2023;61(1):2201217. [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen EA, Jackson DJ, Heffler E, Mathur S, Pavord ID. Eosinophil knockout humans: Uncovering the role of eosinophils through eosinophil-directed biological therapies. Annu Rev Immunol. 2021;39:719–57. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh JE, Hearn AP, Dhariwal J, d'Ancona G, Douiri A, Roxas C, Fernandes M, Green L, Thomson L, Nanzer AM, Kent BD, Jackson DJ. Real-world effectiveness of benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma. Chest. 2021;159(2):496–506. [CrossRef]

- Klion AD, Ackerman SJ, Bochner BS. Contributions of eosinophils to human health and disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2020;15:179–209. [CrossRef]

- Korn S, Bourdin A, Chupp G, Cosio BG, Heffler E, Gibson PG, Goldman M. Integrated safety and efficacy among patients receiving benralizumab for up to 5 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(12):4381–92.e4. [CrossRef]

- Kuang FL, Legrand F, Makiya MA, Langford CA, Gilliland WR, Fay MP, Klion AD. Benralizumab for PDGFRA-negative hypereosinophilic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(14):1336–46. [CrossRef]

- Langton D, Bourke P, Wright GM, Green J, Radhakrishna N, Wood-Baker R, Plummer V, Hew M. Benralizumab and mepolizumab treatment outcomes in two severe asthma clinics. Respirology. 2023;28(12):1117–25. [CrossRef]

- Lee JJ, Jacobsen EA, Ochkur SI, McGarry MP, Condjella RM, Doyle AD, Luo H, Wynn TA, Rosenberg HF, Epx KO. Human versus mouse eosinophils: "That which we call an eosinophil, by any other name would stain as red". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(3):572–84. [CrossRef]

- Maio S, Baldacci S, Bresciani M, Simoni M, Latorre M, Murgia N, Spinozzi F, Braschi M, Antonicelli L, Brunetto B; et al. RItA: The Italian severe/uncontrolled asthma registry. Allergy. 2018;73(4):683–95. [CrossRef]

- Marichal T, Mesnil C, Bureau F. Homeostatic eosinophils: Characteristics and functions. Front Med. 2017;4:101. [CrossRef]

- Menzies-Gow A, Wechsler ME, Brightling CE, Korn S, Sher L, Martin UJ, Aurivillius M, Goldman M. Oral corticosteroid elimination via a personalised reduction algorithm in adults with severe eosinophilic asthma treated with benralizumab (PONENTE): A multicentre, open-label, single-arm study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(1):47–58. [CrossRef]

- Moran AM, Meka VG, Zangrilli JG. Blood eosinophil depletion with mepolizumab, benralizumab, and prednisolone in eosinophilic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(9):1314–6. [CrossRef]

- Nair P, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, Bourdin A, Lugogo NL, Kuna P, Chanez P, Papi A, Khatri S, Gilmartin G; et al. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of benralizumab in severe asthma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(25):2448–58. [CrossRef]

- Ondari, E.; Calvino-Sanles, E.; First, N.J.; et al. Eosinophils and bacteria, the beginning of a story. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8004. [CrossRef]

- Ondari E, Calvino-Sanles E, First NJ, Russell REK, Bafadhel M, Pavord ID, Russell TL, Wark PAB. Eosinophils and bacteria, the beginning of a story. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(15):8004. [CrossRef]

- Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, Brusselle GG, FitzGerald JM, Chetta A, Humbert M, Katz LE, Keene ON, Yancey SW, Chanez P. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1198–207. [CrossRef]

- Park YM, Bochner BS. Eosinophil survival and apoptosis in health and disease. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2(2):87–101. [CrossRef]

- Perez-de-Llano L, Tran TN, Al-Ahmad M, Alacqua M, Bulathsinhala L, Busby J, Canonica GW, Carter V, Chaudhry I, Christoff GC; et al. Characterization of eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic severe asthma phenotypes and proportion of patients with these phenotypes in the International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR). Am Thorac Soc. 2020;C21.

- Piano Terapeutico AIFA per la Prescrizione SSN di Fasenra (Benralizumab) Nell’asma Grave Eosinofilico Refrattario [Internet]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Available from: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2019-02-12&atto.codiceRedazionale=19A00829&elenco30giorni=false [Accessed 2024 Sep 8].

- Pini L, Bagnasco D, Beghè B, Braido F, Cameli P, Caminati M, Caruso C, Crimi C, Guarnieri G, Latorre M, Menzella F, Micheletto C, Vianello A, Visca D, Bondi B, El Masri Y, Giordani J, Mastrototaro A, Maule M, Pini A, Piras S, Zappa M, Senna G, Spanevello A, Paggiaro P, Blasi F, Canonica GW; on behalf of the SANI Study Group. Unlocking the long-term effectiveness of benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma: A three-year real-life study. J Clin Med. 2024;13(10):3013. [CrossRef]

- Price DB, Rigazio A, Campbell JD, Bleecker ER, Corrigan CJ, Thomas M, Wenzel SE, Wilson AM, Yancey SW, Bowman G; et al. Blood eosinophil count and prospective annual asthma disease burden: A UK cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(11):849–58. [CrossRef]

- Price DB, Trudo F, Voorham J, Xu X, Kerkhof M, Ling ZJ, Tran TN. Adverse outcomes from initiation of systemic corticosteroids for asthma: Long-term observational study. J Asthma Allergy. 2018;11:193–204. [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan S, Camp JR, Vijayakumar B, Hardinge FM, Downs ML, Russell REK, Pavord ID, Bafadhel M. The use of benralizumab in the treatment of near-fatal asthma: A new approach. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(12):1441–3. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Munoz JM, Sastre B, Canas JA, Del Pozo V. Eosinophil response against classical and emerging respiratory viruses: COVID-19. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2021;31(1):94–107. [CrossRef]

- Sakkal S, Hughes JM, Haynes DR, Fox SA, Pollock JA, Szer J. Eosinophils in cancer: Favourable or unfavourable? Curr Med Chem. 2016;23(6):650–66. [CrossRef]

- Schleich F, Manise M, Sousa AR, Louis R. Benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma in real life: Confirmed effectiveness and contrasted effect on sputum eosinophilia versus exhaled nitric oxide fraction – PROMISE. ERJ Open Res. 2023;9(1):00383-2023. [CrossRef]

- Vultaggio A, Aliani M, Altieri E, Petroni V, Virchow JC. Long-term effectiveness of benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma patients treated for 96 weeks: Data from the ANANKE study. Respir Res. 2023;24(1):135. [CrossRef]

- Wen T, Rothenberg ME. The regulatory function of eosinophils. Microbiol Spectrum. 2016;4(6). [CrossRef]

- Jackson DJ, Pelaia G, Emmanuel B, Tran TN, Cohen D, Shih VH, Shavit A, Arbetter D, Katial R, Rabe APJ, Garcia Gil E, Pardal M, Nuevo J, Watt M, Boarino S, Kayaniyil S, Chaves Loureiro C, Padilla-Galo A, Nair P. Benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma by previous biologic use and key clinical subgroups: Real-world XALOC-1 programme. Eur Respir J. 2024;64(1):2301521. [CrossRef]

| Baseline characteristics | Overall (N=123), median (IQR)/mean (SD)/n (%) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 43.5 (30.5–55.6) |

| Starting therapy age (years) | 61.0 (54.0–70.0) |

| BMI (units) | 26.0 (23.2–29.8) |

| Smoking status (N=122) | |

| ex | 36 (29.3%) |

| no | 83 (67.5%) |

| yes | 3 (2.4%) |

| Pre-BD FEV1 (% pred.) | 71.61 (21.75) |

| Pre-BD FVC (% pred.) | 93.41 (22.28) |

| Pre-BD FEV1/FVC (% pred.) | 62.19 (12.60) |

| Pre-BD FEF% (% pred.) | 15.04 (4.68) |

| ACT score | 59.72 (52.52) |

| FeNO (ppb) | 646.54 (636.95) |

| Eosinophils (cells/mm3) | 7.46 (8.29) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 41 (33.3%) |

| CRSwNP | 70 (56.9%) |

| Bronchiectasis (n=119) | 32 (26.0%) |

| Atopy (n=122) | 51 (41.5%) |

| ASA NSAID hypersensitivity | 15 (12.2%) |

| GERD | 45 (36.6%) |

| EGPA (n=122) | 7 (5.7%) |

| Cardiovascular comorbidities | 50 (40.7%) |

| Metabolic comorbidities | 34 (27.6%) |

| Neuropsychiatric comorbidities (n=122) | 10 (8.1%) |

| Adverse events | Baseline, n (%) | Month 12, n (%) | Month 24, n (%) | Month 36, n (%) | Month 48, n (%) | Overall, n (%) |

| Related | ||||||

| Nausea | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Urticaria | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Likely | ||||||

| Vagal hypotension | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Not related | ||||||

| Altered coagulative diathesis | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Bronchitis | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (1.6%) | 4 (3.3%) |

| Asthma exacerbation | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (2.4%) | 4 (3.3%) | 2 (1.6%) | 5 (4.1%) | 14 (11.4%) |

| Influenza | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Polyarthritis | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Pneumonia | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (1.6%) |

| Study | Design | Population | Duration | Key safety findings | Types of adverse events |

| SIROCCO [Beecker ER, 2016] | Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 1,205 patients | 48 weeks (12 months) | AEs: 71–73% in benralizumab vs 78% in placebo. SAEs: 12–13% (benralizumab) vs 14% (placebo) Low discontinuation due to AEs (2%) |

Common AEs: headaches (7–9%), nasopharyngitis (12%), upper respiratory tract infections (8–11%) Infusion-related reactions: rare (2–4%) |

| CALIMA [Fitzgerald JM, 2016] | Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 1,306 patients | 56 weeks (13 months) | AEs: 74–75% in benralizumab vs 78% in placebo Drug-related AE: 12–13% vs 8% in placebo SAEs: 9–10% (benralizumab) vs 14% (placebo) Similar rates of AEs between groups |

Common AEs: nasopharyngitis (18–21%), headaches (8%), upper respiratory infections (7–8%) Infusion-related reactions: low incidence (2–3%) |

| ZONDA [Nair P, 2017] | Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 220 patients requiring chronic OCS | 28 weeks (7 months) | AEs: 68–75% in benralizumab vs 83% in placebo SAEs: 10% (benralizumab) vs 19% (placebo) No increase in AEs during OCS reduction |

Common AEs: nasopharyngitis (17%), worsening asthma (13%), and bronchitis (10%) |

| ANDHI [Harrison TW, 2021] | Phase IIIb, open-label, observational | 660 patients | 24–32 weeks (6–8 months) | AEs: 62% in benralizumab SAEs: 8% in benralizumab Long-term safety was confirmed with no new signals |

Common AEs: similar to SIROCCO and CALIMA Most frequent: infection-related AEs and headaches |

| MELTEMI [Korn S, 2021] | Open-label extension study (2+ years of treatment) | 1,025 patients previously treated with benralizumab in prior trials | 2 years | AEs: 64.6–84.6% in the benralizumab group vs 45.9–87.7% in the placebo SAEs: 2.4–13.3% (benralizumab) vs 4.5–14.2% in placebo Safety profile consistent, confirming long-term safety |

Common AEs: nasopharyngitis (11.1–19.3%), headaches (5–12.6%), upper respiratory infections (1.6–8.9%), and bronchitis (3.6–9.2%) Infection-related AEs similar to previous studies |

| ANANKE [Vultaggio A, 2023] | Observational retrospective | 162 patients | 96 weeks | No new safety concerns reported | Not specifically reported |

| XALOC -1 [Jackson DJ, 2024] | Observational real-world study | 1,002 patients (380 biologic-experienced) | 48 weeks (12 months) | No new safety concerns reported. Not specifically detailed, but consistent with prior studies in safety profile. | Not specifically reported |

| Long-term eosinophil depletion: a real-life perspective on safety and durability of benralizumab treatment in severe eosinophilic asthma | Long-term real-world study | 123 patients previously treated with benralizumab | 48 months (4 years) | AEs: 21.1% (26 total); only 1.6% related to treatment SAEs: 0.8% due to vagal hypotension, leading to discontinuation Bronchitis in 15.4% of infections, unrelated to treatment |

Common AEs: bronchitis (15.4%), mostly between 36 and 38 months Related to infusion: nausea (0.8%) and urticaria (0.8%) SAE: vagal hypotension (0.8%), leading to discontinuation |

| Category | WHO Pharmacovigilance Database [Cutroneo PM, 2024] | Spanish Pharmacovigilance Database [Boada-Fernández-Del-Campo C, 2024] | Post-marketing surveillance and spontaneous AE reporting [Jackson DJ, 2020] | Long-term eosinophil depletion: a real-life perspective on safety and durability of benralizumab treatment in severe eosinophilic asthma |

| Total cases reported | Over 5,512 individual case safety reports (ICSRs) | 588 reports in Spain | ~36,680 patient-years (post-marketing exposure globally) | 26 cases (21.1% of patients) |

| SAEs | SAEs in 29.5% and 1.3% of cases were life-threatening | 18% of total cases categorized as serious | ~11.5% (SIROCCO/CALIMA trials) and 16.9% in long-term studies (up to 2 years) | 0.8%: vagal hypotension |

| Common AEs | General disorders (e.g., malaise, fatigue), injection-site reactions, nasopharyngitis, headaches and hypersensitivity | Headaches (14.6%), pharyngitis (16.15%), fatigue (55 cases), pneumonia | Nasopharyngitis (16%), headaches (8.1%), bronchitis (7.9%) | Bronchitis (15.4%), nausea (0.8%), urticaria (0.8%) |

| Malignancies | Very low malignancy risk (<1%) noted in long-term data | Not emphasized | 0.8% malignancy risk during 2-year trials (BORA) | No malignancies reported |

| Immune system reactions | Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) risk noted | Anaphylaxis and hypersensitivity reactions noted | Hypersensitivity reactions (e.g., injection-site reactions) included in labeling | Vagal hypotension (0.8%) |

| Discontinuation rates | Not specifically reported | Not reported | ~2% discontinuation due to AEs (SIROCCO/CALIMA trials), mostly mild reactions | None |

| Death reports | ~3.2% related to serious adverse events | No specific death reports linked directly to benralizumab therapy | Deaths related to severe asthma complications in ~0.3% of long-term trial participants (BORA) | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).