Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Determination of the Thermodynamic Properties

2.1.1. Isosteric Sorption Heat (kJ ⋅ mol-1)

2.1.2. Spreading Pressure (Φ) (J ⋅ m-2)

2.1.3. Differential Entropy (ΔS) (J ⋅ mol-1 ⋅ K-1)

2.1.4. Net Integral Sorption Enthalpy (qeq) (J ⋅ mol-1 ⋅ K-1)

2.1.5. Net Integral Sorption Entropy (ΔSeq) (J ⋅ mol-1 ⋅ K-1)

2.2. Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) in the CP+FAC

2.3. Plasticizer Behavior of Water

2.4. Particle Size Distribution

2.5. Particle Morphology

3. Results and Discussion

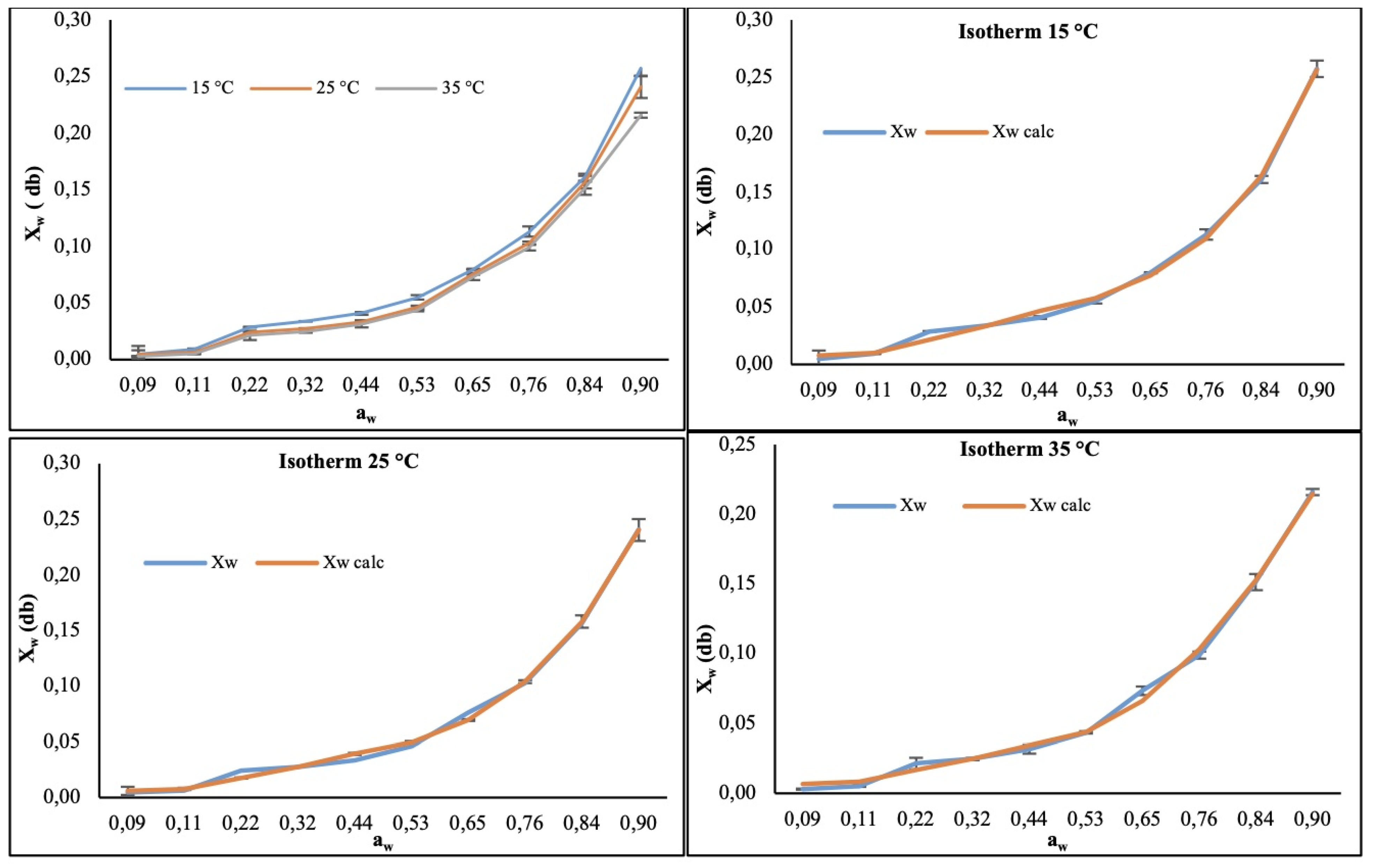

3.1. Water Sorption Isotherms of the CP+FAC

3.2. Thermodynamic Properties of the CP+FAC

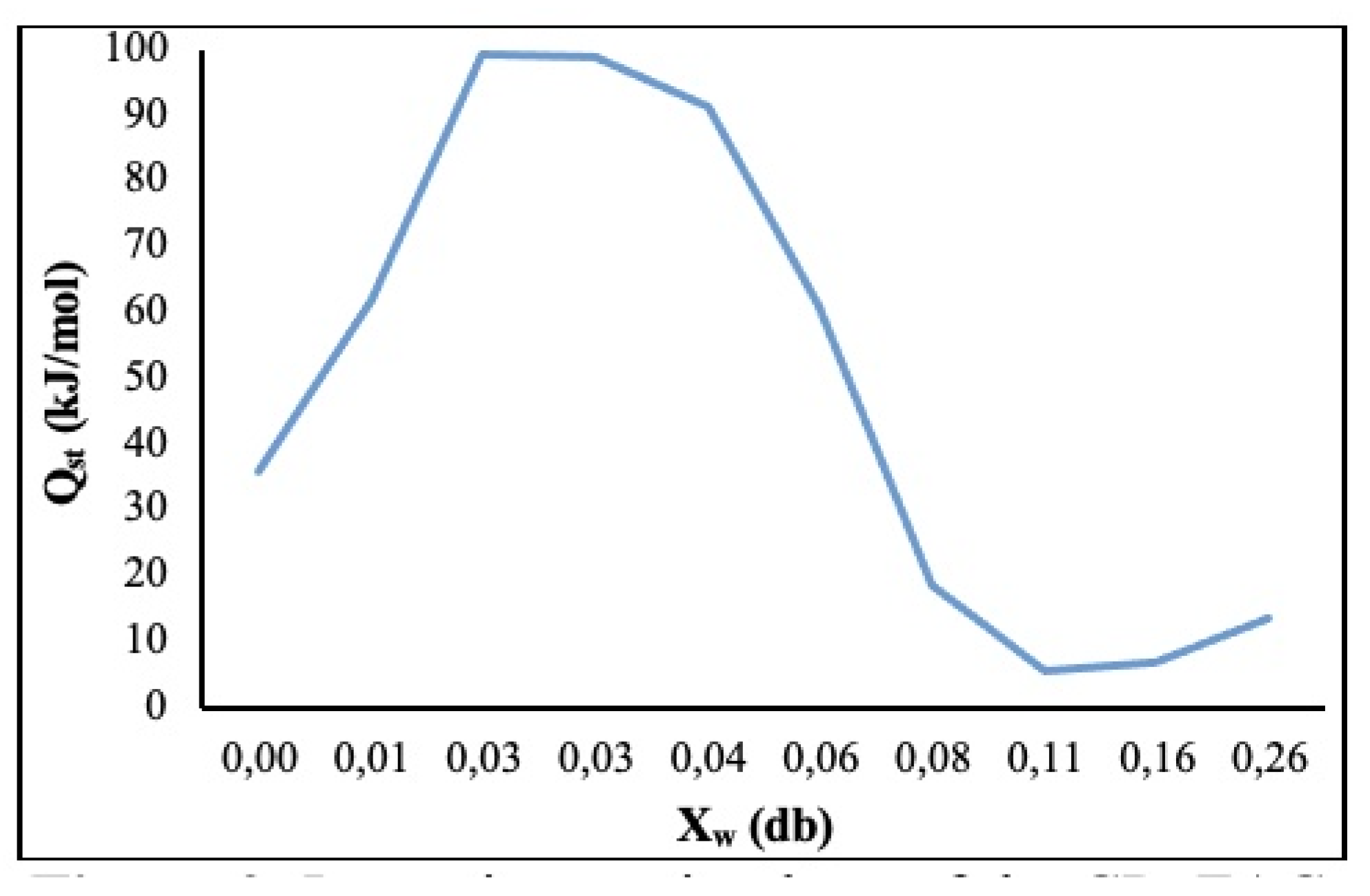

3.2.1. Isosteric Sorption Heat (Qst)

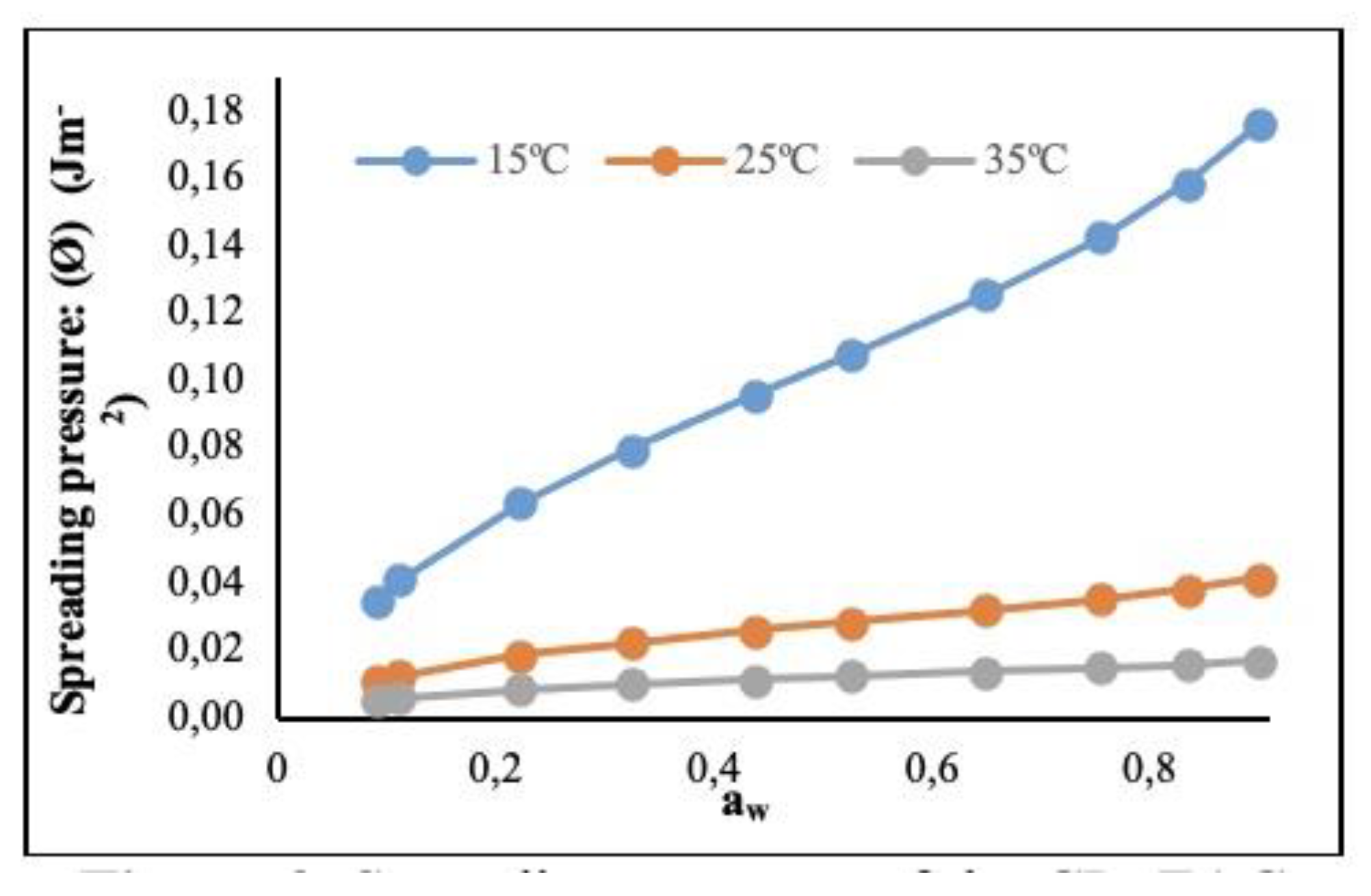

3.2.2. Spreading Pressure (Φ) (J ⋅ m-2)

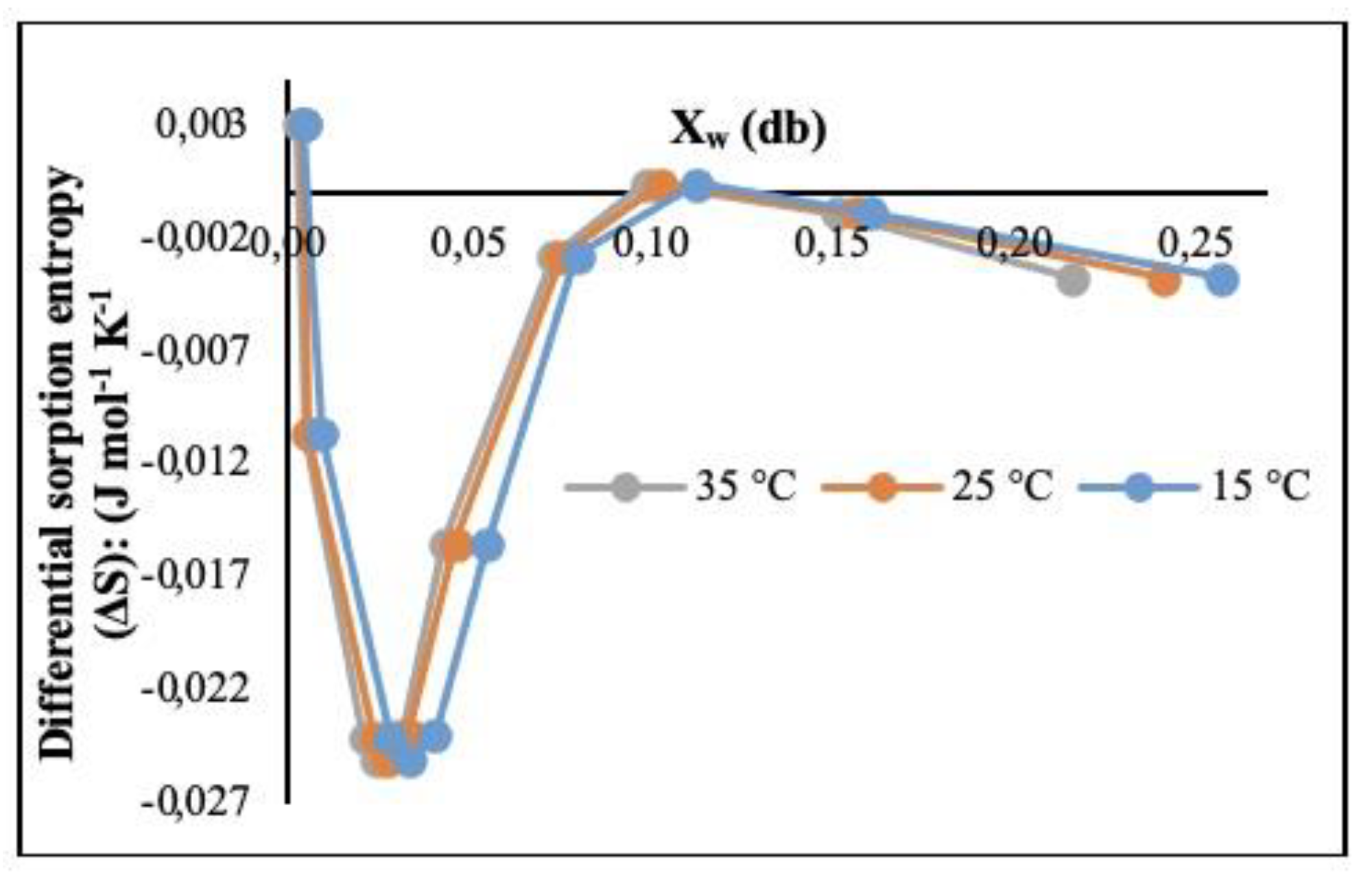

3.2.3. Differential Sorption Entropy (ΔS) (J ⋅ mol-1 ⋅ K-1)

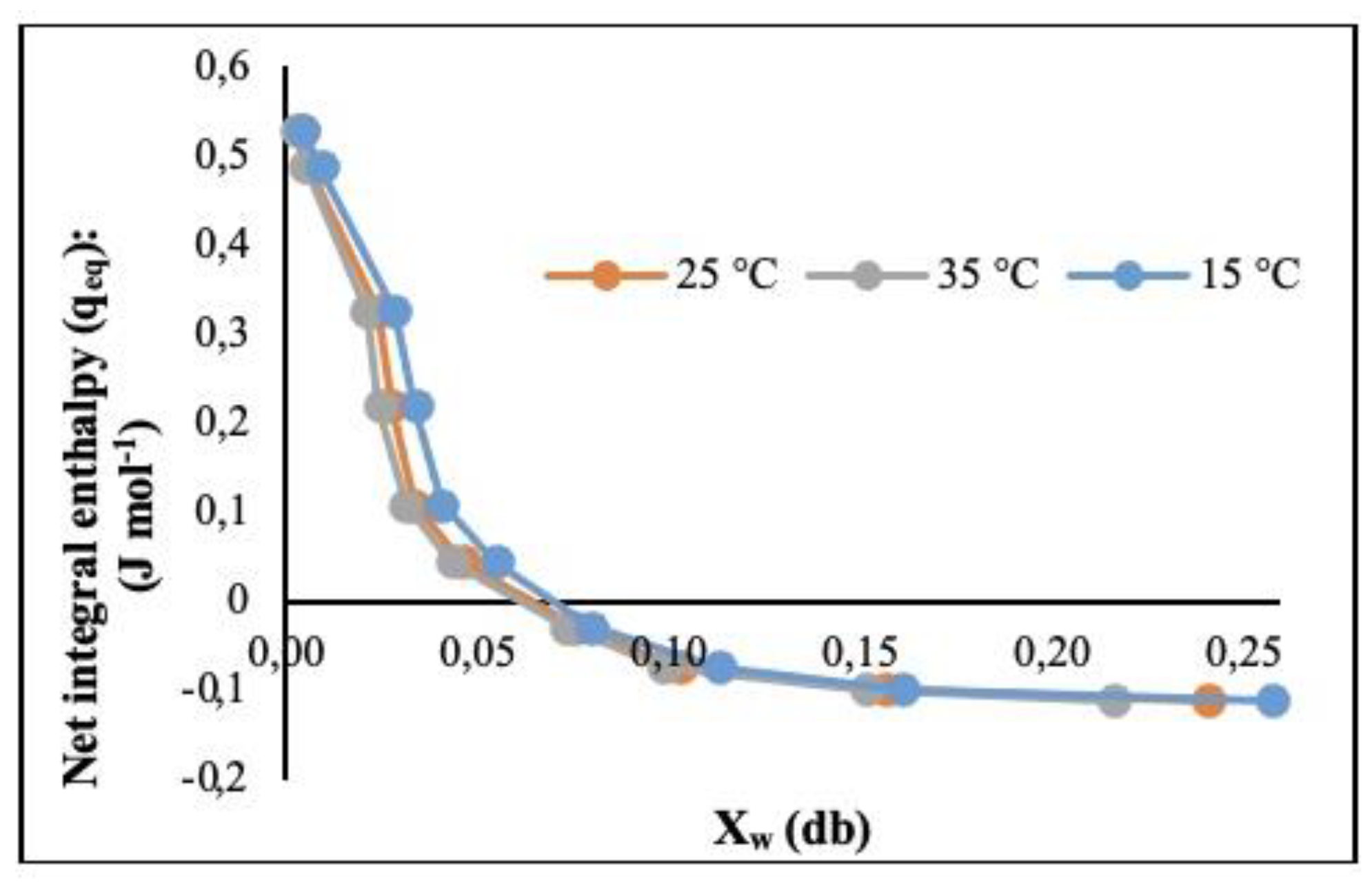

3.2.4. Net Integral Sorption Enthalpy (qeq) (J ⋅ mol-1)

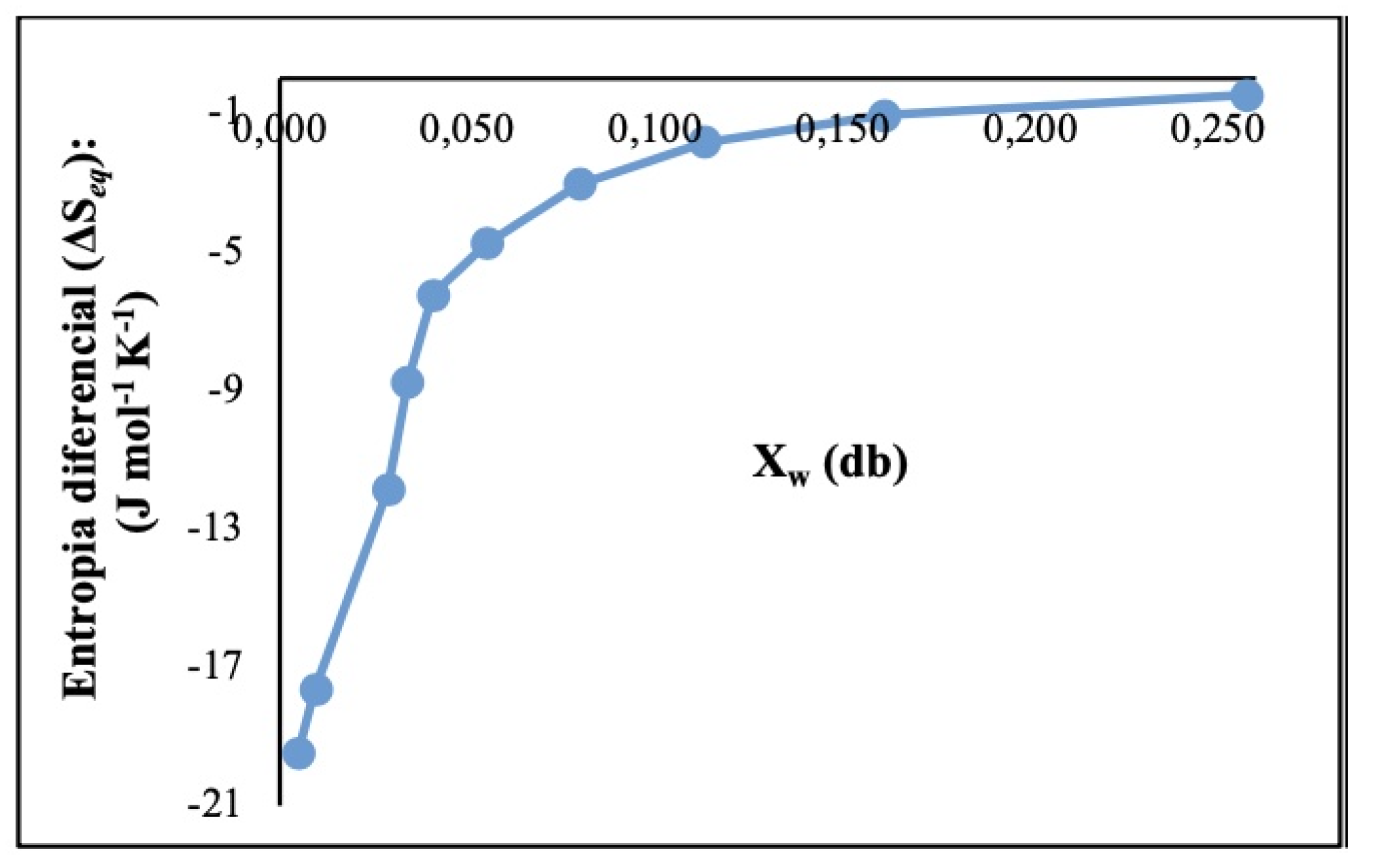

3.2.5. Net Integral Sorption Entropy (ΔSeq) (J ⋅ mol-1 ⋅ K-1)

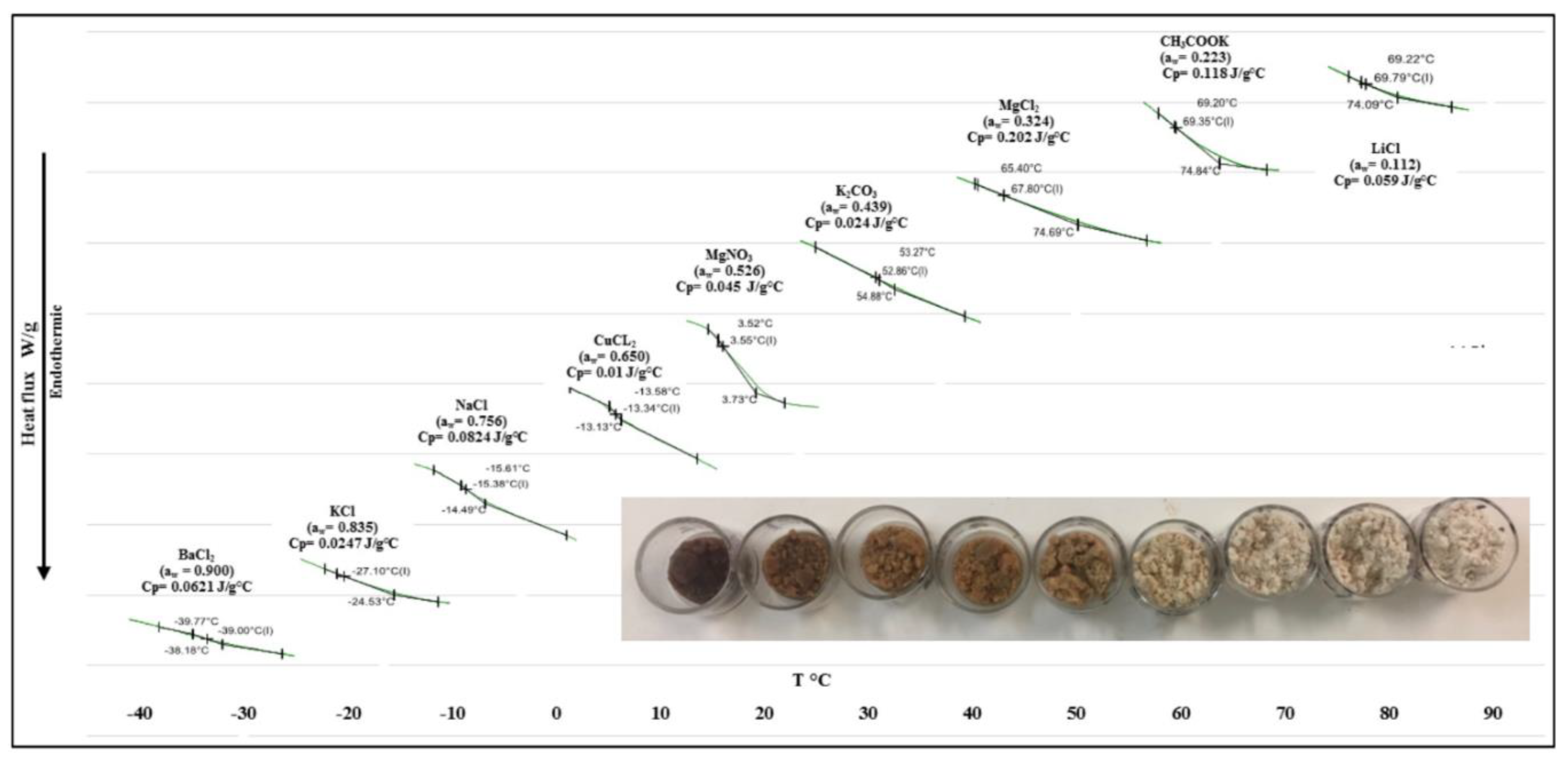

3.3. Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) and Its Relation with the Composition

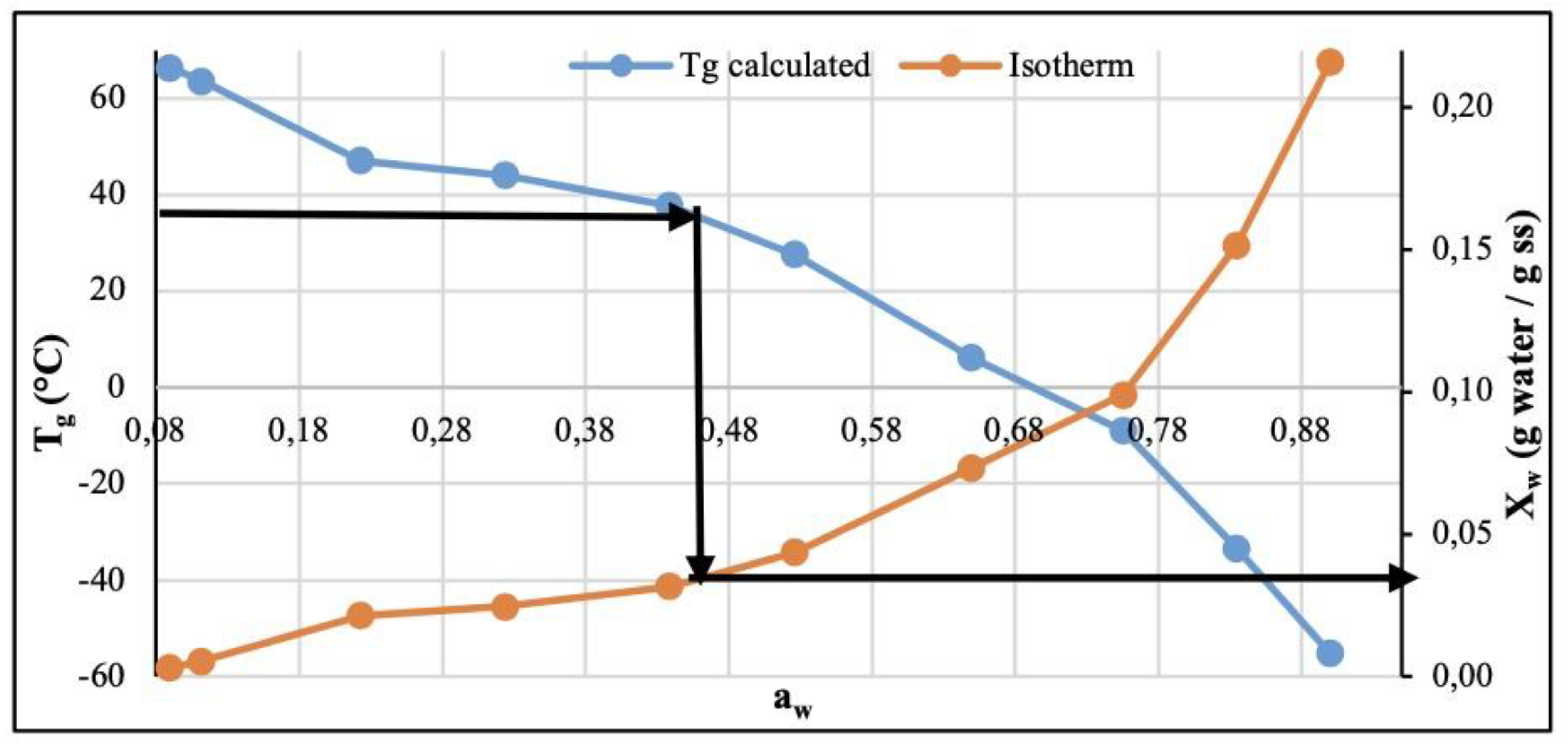

3.4. Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) – Water Activity (aw) Relation and Content in Moisture (Xw – Water Activity (aw) in the CP+FAC

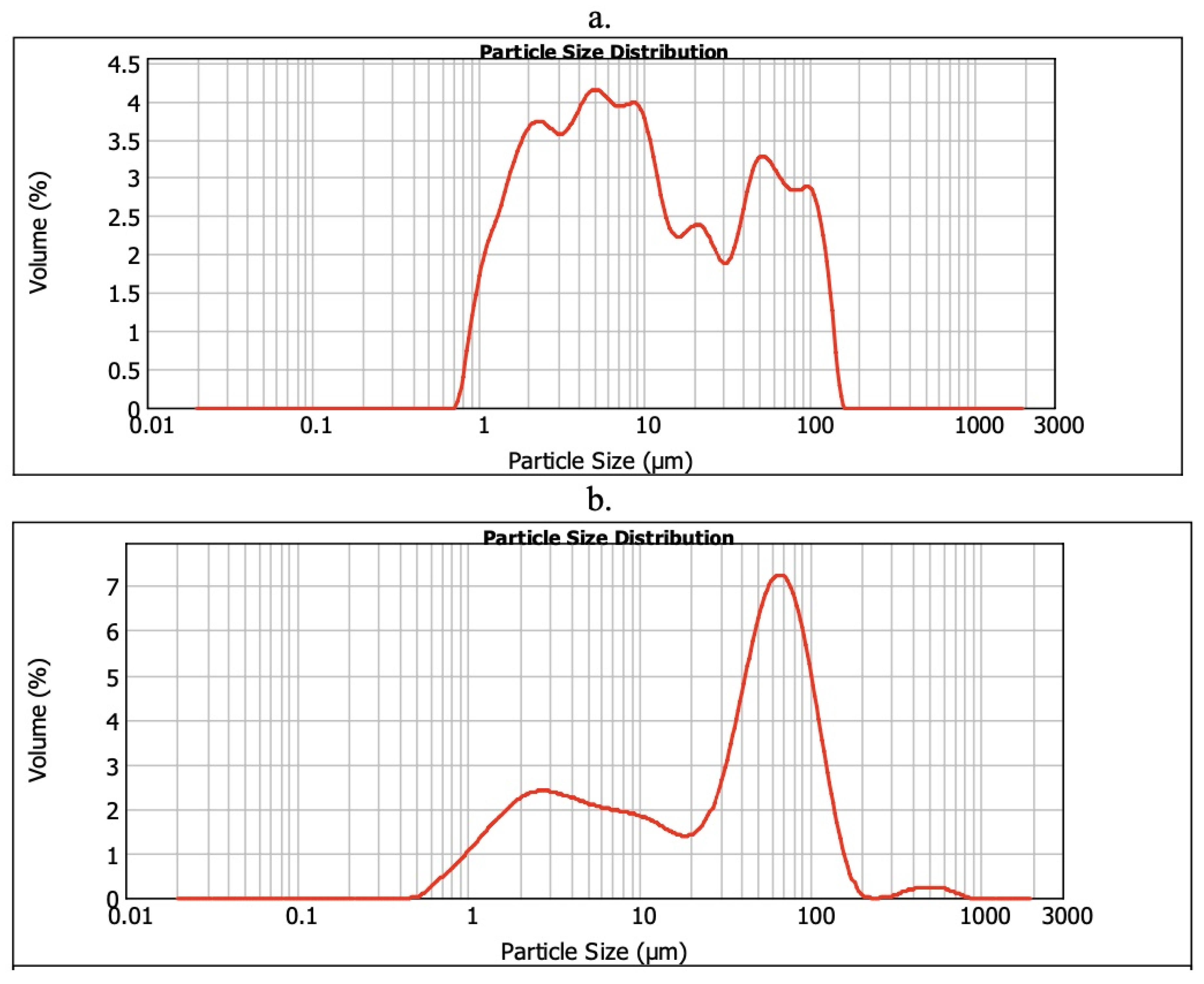

3.5. Particle Size Distribution (D10, D50, and D90) in the CP+FAC

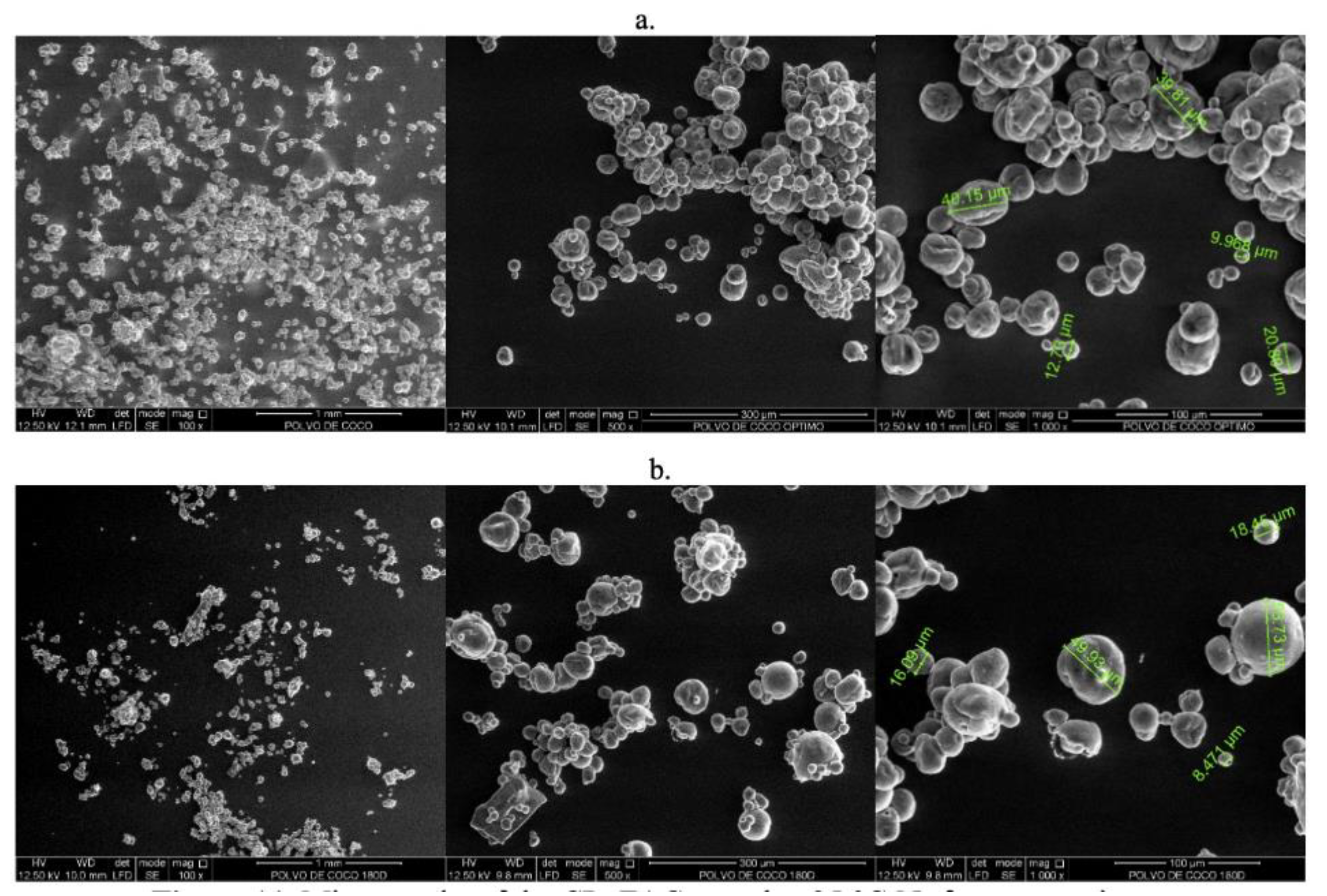

3.6. CP+FAC Morphology

4. Conclusions

- CRediT authorship contribution statement: Juan Carlos Lucas and Misael Cortes, Formal analysis. Conceptualization: Writing - review & editing. German Antonio Giraldo and Juan Carlos Lucas: Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Misael Cortes and Juan Carlos Lucas: Methodology, Resources, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

Declaration of Competing Interest

Nomenclature

| aw | water activity |

| awc | critical water activity |

| Am | area of water molecule: (1.06 x 10-19 m2) |

| a, b, c1, c2, m1, m2, n1, n2, A, B, C, K | are fit parameters of each model |

| b and b0 | constants of Dent’s sorption isotherm |

| db | dry base |

| Xw | moisture content |

| mo | humidity of the monolayer |

| EMC | equilibrium moisture content |

| CP+FAC | coconut powder fortified with vitamins C, D3, E and calcium |

| SD | spray dried |

| RH | relative humidity |

| R | constant of ideal gases (KJ ⋅ mol-1 ⋅ K-1) |

| R2 | coefficient of determination |

| RMSE | minimum root of mean square error |

| Qst | Isosteric sorption heat (kJ mol-1) |

| ΔS | differential sorption entropy (J ⋅ mol-1 ⋅ K-1) |

| Φ | spreading pressure (J ⋅ m-2) |

| qeq | net integral sorption enthalpy (J ⋅ mol-1) |

| ΔSeq | Net integral sorption entropy (J ⋅ mol-1 ⋅ K-1) |

| Tg | glass transition temperature |

| Xwc | critical moisture content |

| DSC | differential scanning calorimetry |

| λvap | latent vaporization heat of pure water (kJ ⋅ mol-1) |

| T | absolute temperature (K) |

| Xeq | equilibrium moisture content (Kg ⋅ Kg-1 db) |

| KB | Boltzmann’s constant (1.380 x 10-23 J ⋅ K-1) |

| Tgw | water glass transition temperature: -135.15 °C (138.15 K) |

| Tgs | glass transition temperature of the anhydrous solids |

| xw | mass fraction of water |

| k | constant of the Gordon-Taylor model |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| BET | Brunauer, Emmett and Teller mathematical model for modeling sorption isotherms |

| GAB | Guggenheim, Anderson and de Boer model for water sorption isotherm analysis |

References

- Alpizar-Reyes, E.; Carrillo-Navas, H.; Romero-Romero, R.; V Varela-Guerrero, V.; Álvarez-Ramírez, J.; Pérez-Alonso, C. Thermodynamic sorption properties and glass transition temperature of tamarind seed mucilage (Tamarindus indica L.). Food and Bioproducts Processing 2017, 101, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile, F.E.; Judis, M.A.; Mazzobre, M.F. Moisture sorption properties and glass transition temperature of a non- conventional exudate gum (Prosopis alba) from northeast Argentine. Food Research International 2020, 131, 109033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.P.; Schmidt, S.J. Developments in glass transition determination in foods using moisture sorption isotherms. Food Chemistry 2012, 132, 1693–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Gutiérrez, S.K.; Figueira, A.C.; Rodríguez-Huezo, M.E.; Román-Guerrero, A.; Carrillo-Navas, H.; Pérez-Alonso, C. Sorption isotherms, thermodynamic properties and glass transition temperature of mucilage extracted from chia seeds (Salvia hispanica L. ). Carbohydrate Polymers 2015, 121, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, S.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, D.W. Glass transitions as affected by food compositions and by conventional and novel freezing technologies: A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2019, 94, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdia, S.; Hong, Y.K.; Qu, Z.; Sablani, S.S. State diagram, water sorption isotherms and color stability of pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L. ). Journal of Food Engineering 2020, 273, 109820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Muñoz, D.P.; Neves-deOliveira, L.A.; Cardoso-daSilva, L.; Teixeira-Godoy, H.; Emy-Kurozawa, L. Storage stability of 5-caffeoylquinic acid in powdered cocona pulp microencapsulated with hydrolyzed collagen and maltodextrin blend. Food Research International 2020, 137, 109652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stępién, A.; Witczak, M.; Witczak, T. Sorption properties, glass transition and state diagrams for pumpkin powders containing maltodextrins. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2021, 134, 110192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Talukdar, P. Determination of thermophysical and desorption properties of elephant foot yam using composition based and fast sorption method. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 2020, 18, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; McMinn, W.A.M.; Magee, T.R.A. Water sorption isotherms of starch powders. Part 2: Thermodynamic characteristics. Journal of Food Engineering 2004, 62, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Aponte, A. Determinación de las isotermas de sorción y del calor isosterico en harina de yuca. Biotecnología en el Sector Agropecuario y Agroindustrial 2011, 9, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Aponte, A. Thermodynamic properties of moisture sorption in cassava flour. DYNA 2016, 83, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Gutiérrez, B.L.; Márquez-Cardozo, C.J.; Ciro-Velásquez, H.J. Thermodynamic Study of Adsorption Properties of Rocoto Pepper (Capsicum pubescens) Obtained by Freeze-Drying. Advance Journal of Food Science and Technology 2018, 15, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussaoui, H. , Bahammoua, Y., Idlimama, A., Lamharrar, Abdenouri, N. Investigation of hygroscopic equilibrium and modeling sorption isotherms of the argan products: A comparative study of leaves, pulps, and fruits. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2019, 114, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largo-Ávila, E.; Cortes-Rodríguez, M.; Ciro-Velásquez, H.J. The adsorption thermodynamics of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) powder obtained by spray dryig technology. VITAE 2014, 21, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Aguirre, J.C.; Tobón-Castrillón, C.; Cortes-Rodríguez, M. Influence of the composition of coconut-based emulsions on the stability of the colloidal system. Advance Journal of Food Science and Technology 2018, 14, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Aguirre, J.C.; Giraldo- Giraldo, G.A.; Cortes-Rodríguez, M. Effect of the Spray Drying Process on the Quality of Coconut Powder Fortified with Calcium and Vitamins C, D3 and E. Advance Journal of Food Science and Technology 2018, 16, 102–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo-Giraldo, G.A.; Cortes-Rodríguez, M. Modelling of Moisture Sorption Isotherm and Evaluation of Net Isosteric Heat for Spray-Dried Fortified Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) Powder. British Food Journal 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, C.; Bruin, S. Water activity and its estimation in food systems. In Water Activity: Influences on Food Quality; Rockland, L.B., Stewart, G.F., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, 1981; pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of gases in multi-molecular layers. Journal of American Chemistry Society 1938, 60, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswin, C.R. The kinetics of package life III. The isotherm. Journal of Chemical Industry 1946, 65, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E. The sorption of water vapor by high polymers. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1947, 69, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsey, G. Physical adsorption on non-uniform surfaces. Journal of Chemistry Physics 1948, 16, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, S. A basic concept of equilibrium moisture. Agricultural Engineering 1952, 33, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, D.S.; Pfost, H. Adsorption and desorption of water by cereal grains and their products. Transactions of the American Society of Agricultural Engineering 1967, 10, 52–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, M. Assessment of a semi-empirical four parameter general model for sigmoid moisture sorption isotherms. Journal of Food Process Engineering 1993, 16, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caurie, M. A new model equation for predicting safe storage moisture levels for optimum stability of dehydrated foods. Journal of Food Technology 1970, 5, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, S.; Kahyaoglu, T. Thermodynamic properties and sorption equilibrium of pestil (grape leather). Journal of Food Engineering 2005, 71, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, N.; Toğrul, H. Modelling of water sorption isotherms of macaroni stored in a chamber under controlled humidity and thermodynamic approach. Journal of Food Engineering 2005, 69, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamau, E.; C Mutungi, C.; Kinyuru, J.; Imathiu, S.; Tanga, C.; Affognon, H.; Ekesi, S.; Nakimbugwe, D.; Fiaboe, K.K.M. Moisture adsorption properties and shelf-life estimation of dried and pulverised edible house cricket Acheta domesticus (L.) and black soldier fly larvae Hermetia illucens (L.). Food Research International 2018, 106, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, R.W. A multilayer theory for gas sorption. Part 1: Sorption of a single gas. Textile Research Journal 1977, 47, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, J.A.; Truong, V.D.; Daubert, D.R. Spray drying of amylase hydrolyzed sweetpotato puree and physicochemical properties of powder. Journal of Food Science 2006, 71, E209–E217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.Z.; Kitamura, Y.; Yamano, Y.; Kitamura, M. Effect of vacuum spray drying on the physicochemical properties, water sorption and glass transition phenomenon of orange juice powder. Journal of Food Engineering 2016, 139, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goula, A.M.; Karapantsios, T.D.; Achilias, D.S.; Adamopoulos, K.G. Water sorption isotherms and glass transition temperature of spray dried tomato pulp. Journal of Food Engineering 2008, 85, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirhosseini, H.; Ping Tan, C.; Hamid, N.S.A.; Yusof, S. Effect of Arabic gum, xanthan gum and orange oil contents on ζ-potential, conductivity, stability, size index and pH of orange beverage emulsion. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2008, 315, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Chauca, M.; Stringheta, P.C.; Ramos, A.M.; Cal-Vidal, J. Effect of the carriers on the microstructure of mango powder obtained by spray drying and its functional characterization. Innov. Food. Sci. Emerg. 2005, 6, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, H.A.; Chirife, J.; Ferro-Fontan, C. On the temperature dependence of isosteric heats of water sorption in dehydrated foods. Journal of Food Science 1989, 54, 1620–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syamaladevi, R.M.; Sablani, S.S.; Tang, J.; Powers, J.; Swanson, B.G. State diagram and water adsorption isotherm of raspberry (Rubus idaeus). Journal of Food Engineering 2009, 91, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Marques, R.C.; Resende-Oliveira, É.; Mendes-Coutinho, G.S.; Chaves-Ribeiro, A.E.; Souza-Teixeira, C.; Soares-Júnior, M.S.; Caliari, M. Modeling sorption properties of maize by-products obtained using the Dynamic Dewpoint Isotherm (DDI) method. Food Bioscience 2020, 38, 100738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibola, O.O.; Aviara, N.A.; Ajetumobi, O.E. Sorption equilibrium and thermodynamic properties of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata). Journal of Food Engineering 2003, 58, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMinn, W.; Magee, T. Thermodynamic properties of moisture sorption of potato. Journal of Food Engineering 2003, 60, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuara, E.; Beristain, C.I. Enthalpic and entropic mechanisms related to water sorption of yogurt. Drying Technology 2006, 24, 1501–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viganó, J.; Azuara, E.; Telis, V.R.N.; Beristain, C.I.; Jiménez, M.; Telis-Romero, J. Role of enthalpy and entropy in moisture sorption behavior of pineapple pulp powder produced by different drying methods. Thermochimica Acta 2012, 528, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotarelli, M.F.; Martins-da Silva, V.; Durigon, A.; Dupas-Hubinger, M.; Borges-Laurindo, J. Production of mango powder by spray drying and cast-tape drying. Powder Technology 2017, 305, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelker, A.L.; Sommer, A.A.; Mauer, L.J. Moisture sorption behaviors, water activity-temperature relationships, and physical stability traits of spices, herbs, and seasoning blends containing crystalline and amorphous ingredients. Food Research International 2020, 136, 109608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.H.; Liu, F.; Wen, X.; Xiao, H.W.; Ni, Y.Y. ; () State diagram for freeze–dried mango: freezing curve glass transition line maximal–freeze–concentration condition, J. Food Eng. 2015, 157, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djendoubi-Mrad, N.; Bonazzi, C.; Courtois, F.; Kechaou, N.; Boudhrioua-Mihoubid, N. Moisture desorption isotherms and glass transition temperatures of osmo-dehydrated apple and pear. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2103, 91, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonon, R.V.; Baroni, A.F.; Brabet, C.; Gibert, O.; Pallet, D.; Hubinger, M.D. Water sorption and glass transition temperature of spray dried açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) juice. Journal of Food Engineering 2009, 94, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pua, C.K.; Hamid, N.S.A.; Tan, C.P.; Mirhosseini, H.; Rahman, R.A.; Rusul, G. Storage stability of jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) powder packaged in aluminium laminated polyethylene and metallized co-extruded biaxially oriented polypropylene during storage. Journal of Food Engineering 2008, 89, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera-Mosquera, L.H. Influencia de la humedad y de la adición de solutos (maltodextrina o goma arábiga) en las propiedades fisicoquímicas de borojó y fresa en polvo. Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, 2010; p. 219. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Cao, X.; Wang, H.; Lia, X. Changes of tomato powder qualities during storage. Powder Technology 2010, 204, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frascareli, E.C.; Silva, V.M.; Tonon, R.V.; Hubinger, M.D. Effect of process conditions on the microencapsulation of coffee oil by spray drying. Food Bioprod. Process 2012, 90, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.M.; Ghalenoei, M.G.; Dehnad, D. Influence of spray drying on water solubility index, apparent density, and anthocyanin content of pomegranate juice powder. Powder Technology 2016, 311, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.K.; Tan, C.P.; Manap, Y.A.; Alhelli, A.M.; Hussin, A.S.M. Process conditions of spray drying microencapsulation of Nigella sativa oil. Powder Technology 2017, 315, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal GKr Kumar-Singh, A.; Kumar, D.; Sharma, H. Effect of spray and freeze drying on physico-chemical, functional, moisture sorption and morphological characteristics of camel milk powder. LWT – Food Science and Technology 2020, 134, 110117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qiu, J.; Cao, X.; Zeng, X.; Tang, X.; Sun, Y.; Lin, L. Drying methods, carrier materials, and length of storage affect the quality of xylooligosaccharides. Food Hydrocolloids 2019, 94, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, C.; Koç, A.; Erbaş, M. Some physical properties and adsorption isotherms of vacuum-dried honey powder with different carrier materials. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2020, 134, 110166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam-Shishir, M.R.; Taip, F.S.; Saifullah, Md.; Aziz, N.Ab.; Talib, R.A. Effect of packaging materials and storage temperature on the retention of physicochemical properties of vacuum-packed pink guava powder. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2017, 12, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Mathematical expression |

|---|---|

| GAB [19] | |

| BET [20] | |

| OSWIN [21] | |

| SMITH [22] | |

| HALSEY [23] | |

| HENDERSON [24] | |

| CHUNG and PFOST [25] | |

| PELEG [26] | |

| CAURIE [27] |

| Model | Variable | 15 °C | 25 °C | 35 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAB | C | 2.64 | 4.261 | 1.811 |

| mo | 0.0715 | 0.0573 | 0.0364 | |

| K | 0.921 | 0.93 | 0.941 | |

| R2 | 0.988 | 0.994 | 0.997 | |

| ERSM | 0.53 | 0.415 | 0.266 | |

| BET | C | 6.555 | 5.921 | 6.365 |

| mo | 0.0254 | 0.0254 | 0.0234 | |

| R2 | 0.987 | 0.994 | 0.984 | |

| ERSM | 0.296 | 0.294 | 0.347 | |

| PELEG | A | 0.467 | 0.103 | 0.076 |

| B | 1.308 | 1.18 | 1.009 | |

| C | 0.118 | 0.395 | 0.294 | |

| D | 10.668 | 9.249 | 6.639 | |

| R2 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.997 | |

| ERSM | 0.198 | 0.199 | 0.276 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).