Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

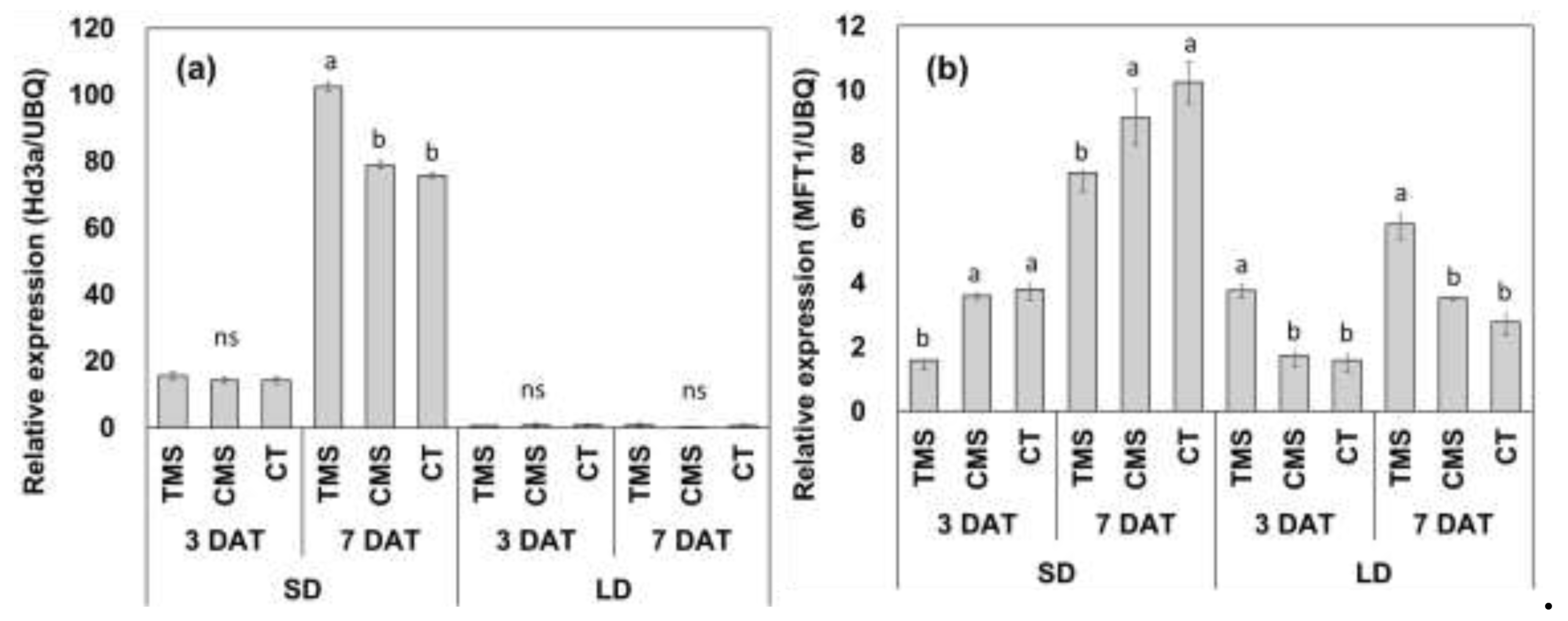

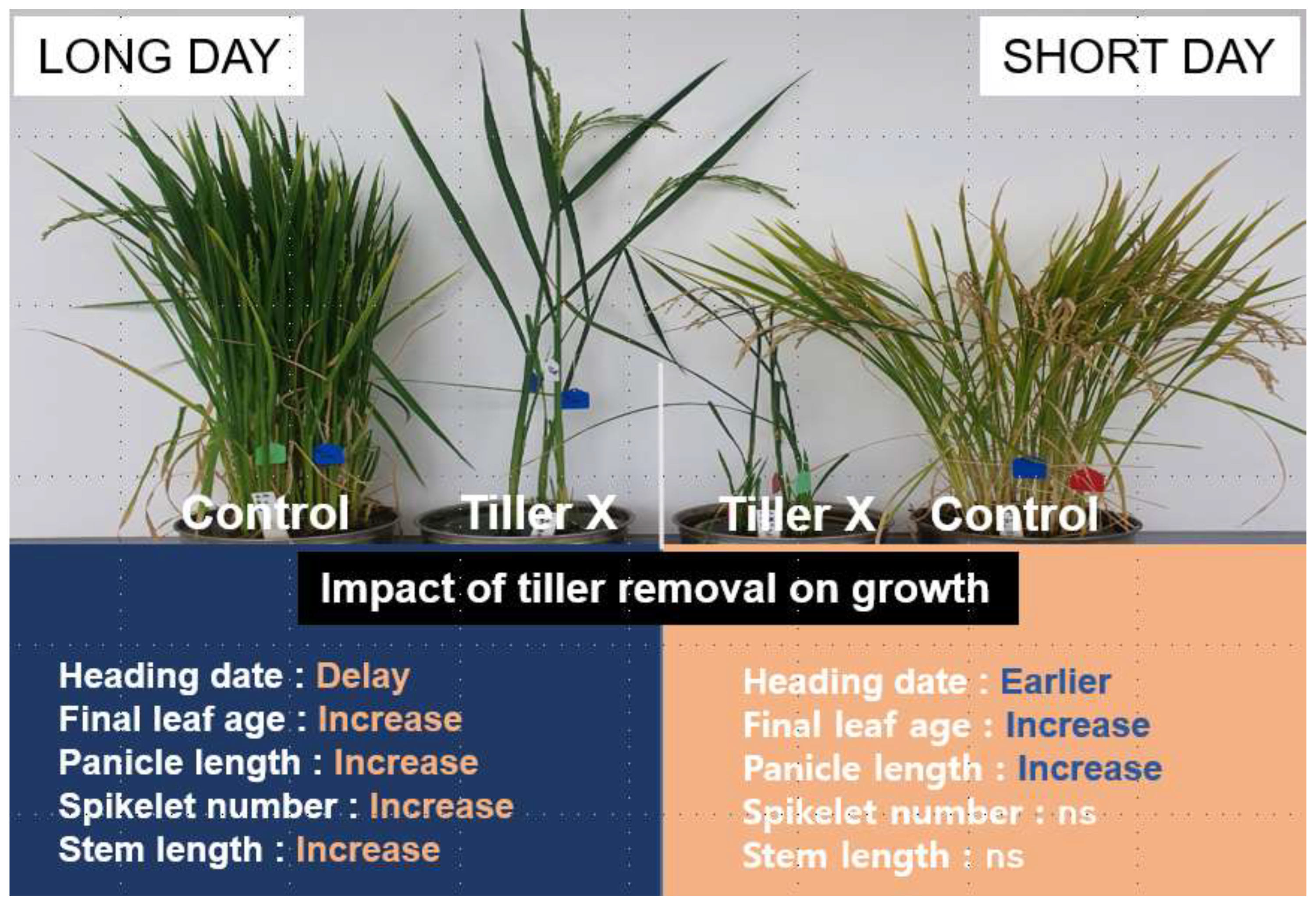

Control of rice tillering and flowering is crucial for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from paddy fields, a key goal of climate-smart agriculture. However, the interaction between tillering and flowering remains debated and poorly understood. We subjected plants of the rice cultivars ‘Saenuri’ and ‘Odae,’ to short- and long-day conditions after removing their tillers, and observed growth and flowering responses. Different daylength conditions yielded contrasting results. Plants in tiller-removal groups grown under short days flowered early compared to controls, whereas the opposite was observed under long days. Further, the expression of the florigen gene, Hd3a, which promotes flowering, increased in the tiller-removal group under short days compared to the control. Conversely, the expression of the OsMFT1 gene, which delays flowering and increases the number of spikelets per panicle, was upregulated under long days, and the phenotypic results were consistent. The number of spikelets per panicle in ‘Saenuri’ and ‘Odae’ plants in the tiller-removal groups under long day conditions increased approximately 3.4 and 2.2 times, respectively, compared to the corresponding control groups. Our findings on tillering and flowering responses to daylength provide a new perspective for the interpretation of studies related to the interaction between tillering and flowering in rice.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Experimental Materials and Design

2.3. Experiment 1: Preliminary test of Growth And Heading Responses To Tiller Removal Under Short-Day Conditions

2.4. Experiment 2: Analysis of Growth And Heading Upon Tiller Removal Under Short- And Long-Day Conditions

2.5. Growth and Development Measurements

2.6. RNA Extraction and Gene Expression

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

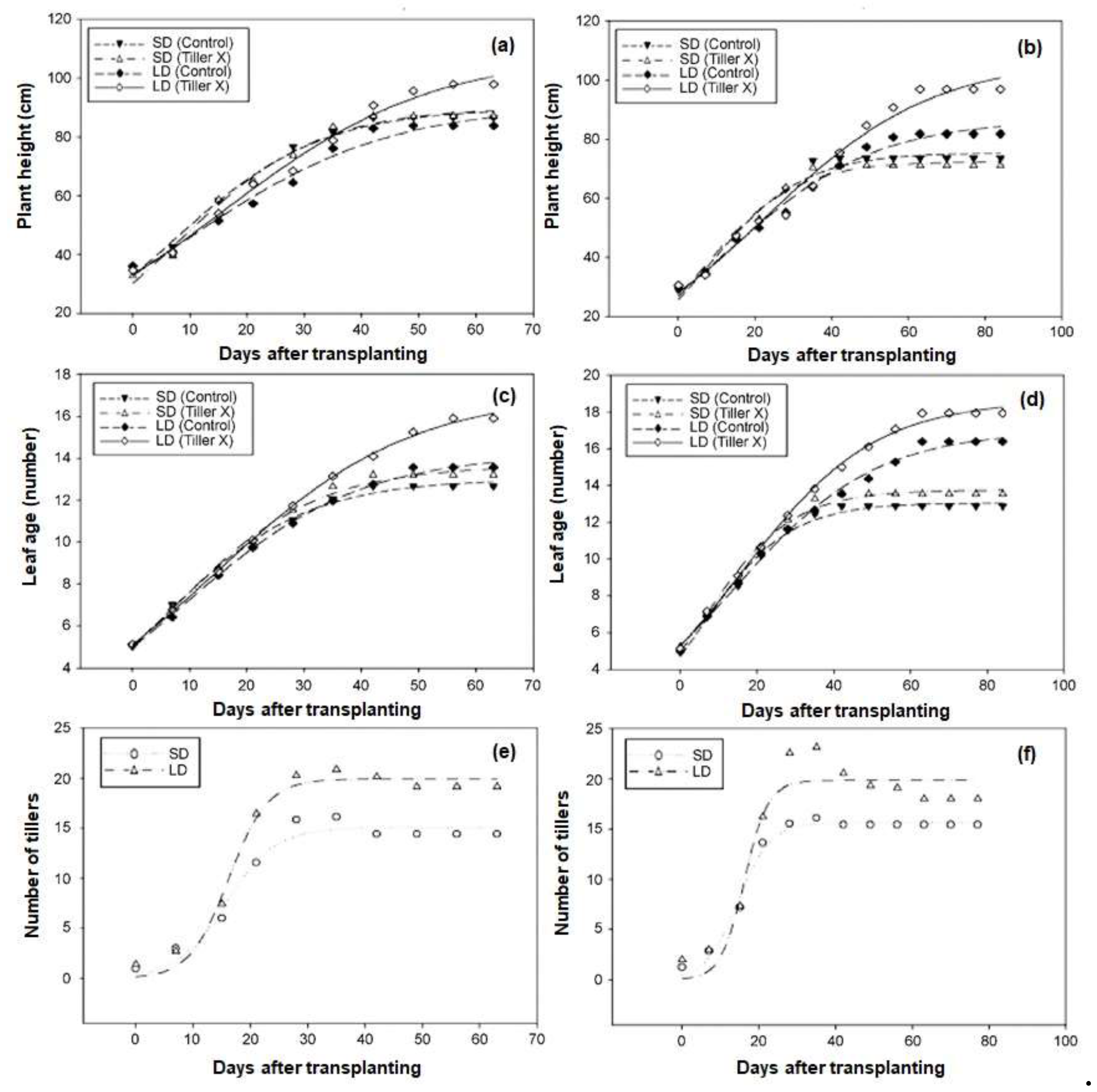

3.1. Daylength-Mediated Effects of Tiller Removal On Plant Growth and Development

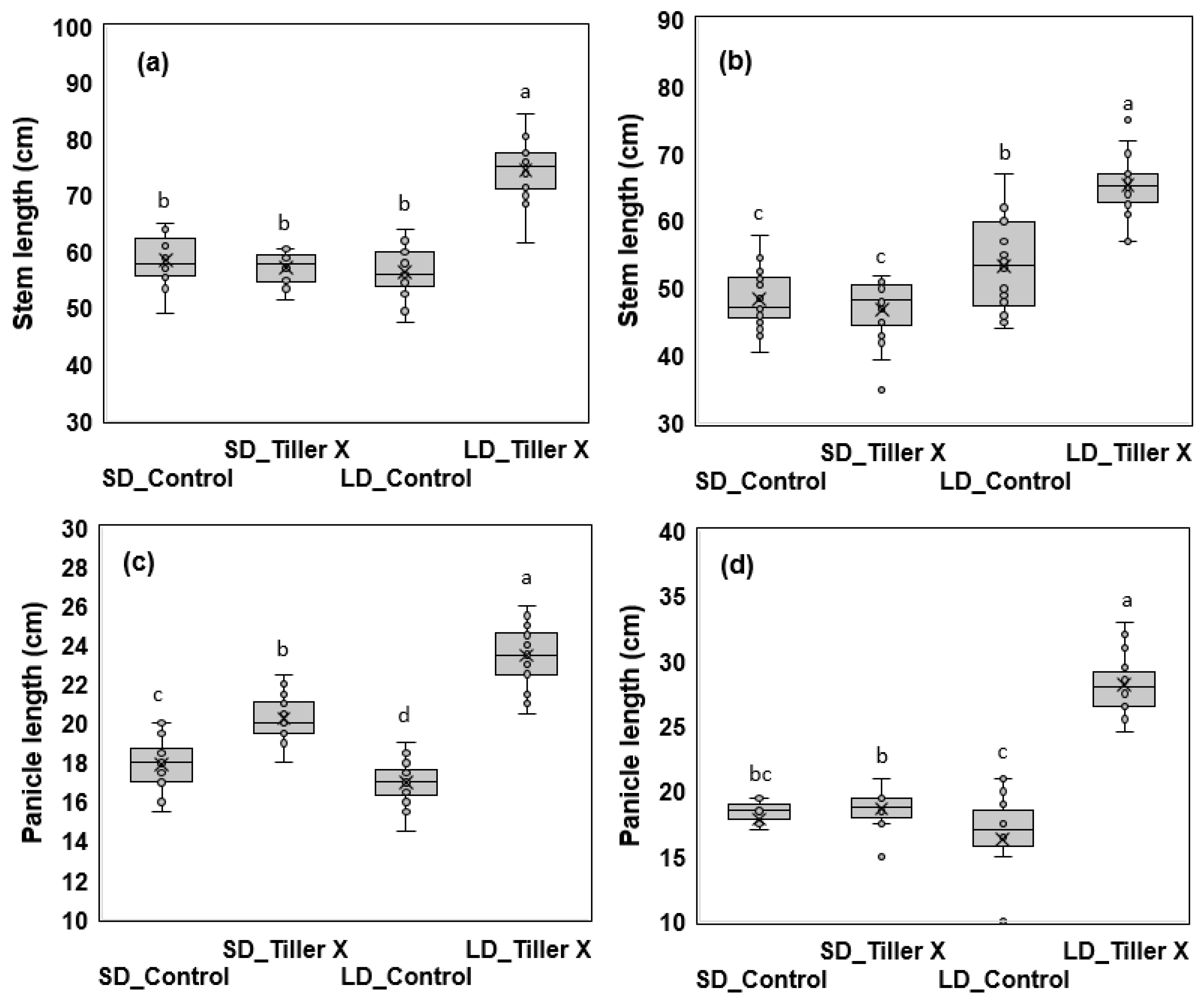

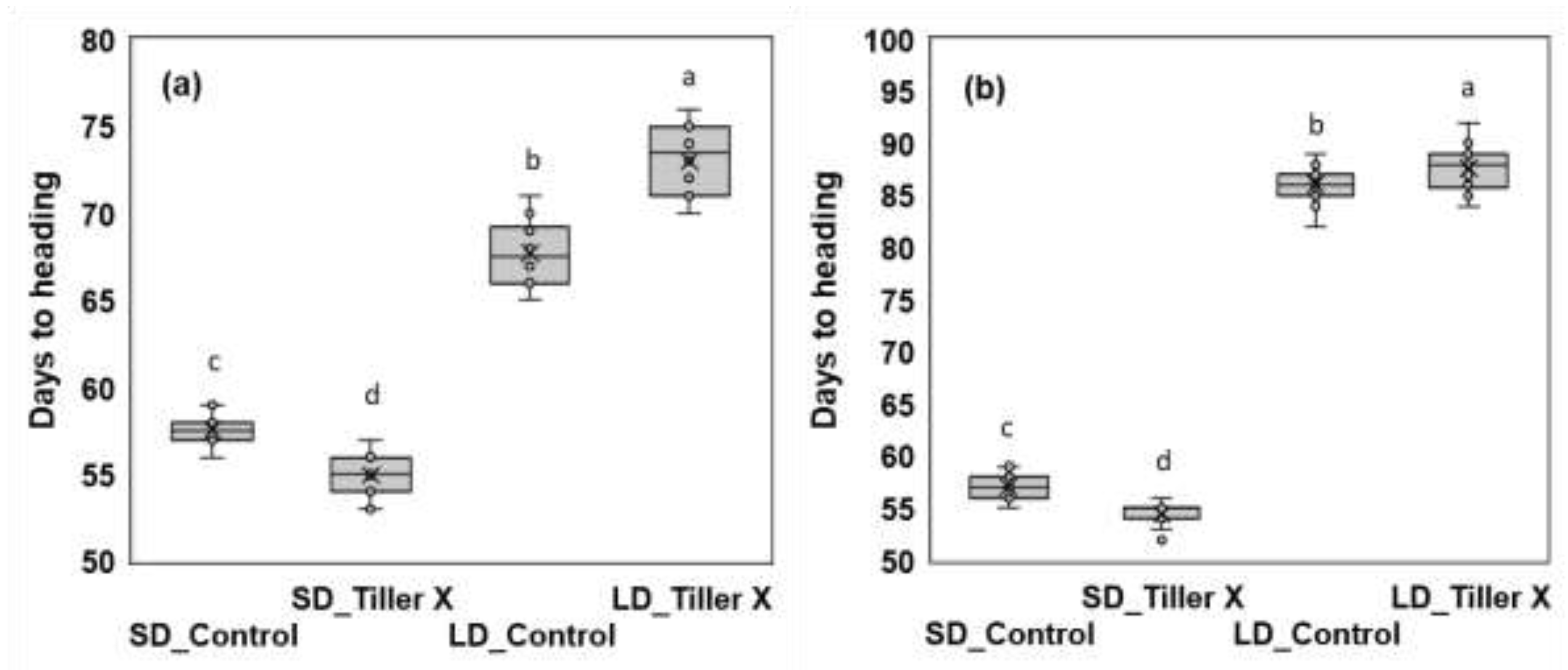

3.2. Effect of Tiller Removal on Heading Response and Yield Components

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Milich, L. The role of methane in global warming: Where might mitigation strategies be focused? Glob. Environ. Change 1999, 9, 179–201. [CrossRef]

- Broucek, J. Production of methane emissions from ruminant husbandry: A review. J. Environ. Prot. 2014, 5, 1482–1493. [CrossRef]

- Minami, K.; Neue, H.U. Rice paddies as a methane source. Clim. Change 1994, 27, 13–26. [CrossRef]

- Ly, P.; Jensen, L.S.; Bruun, T.B.; de Neergaard, A. Methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2) emissions from the system of rice intensification (SRI) under a rain-fed lowland rice ecosystem in Cambodia. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2013, 97, 13–27.

- Setyanto, P.; Pramono, A.; Adriany, T.A.; Susilawati, H.L.; Tokida, T.; Padre, A.T.; Minamikawa, K. Alternate wetting and drying reduces methane emission from a rice paddy in Central Java, Indonesia without yield loss. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2018, 64, 23–30. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Choi, J.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, D.; Cha, J.K.; Park, H.; Kang, J.W.; Kim, T.H.; Chae, H.G.; Kabange, N.R.; Oh, K.W.; Kim, P.J.; Kwak, Y.S.; Lee, J.H.; Ryu, C.M. Loss-of-function gs3 allele decreases methane emissions and increases grain yield in rice. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 1329–1333. [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.H.; Shang, F.; Lin, Q.T.; Lou, C.; Zhang, J. Tillering and panicle branching genes in rice. Gene 2014, 537, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Yan, M.; Zhang, J.; Yu, M.; Tang, S.; Wang, L.; Qu, H.; Luo, L.; Xuan, W.; Xu, G. Nitrogen mediates flowering time and nitrogen use efficiency via floral regulators in rice. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 671–683.e5. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Ren, T.; Hussain, S.; Guo, C.; Wang, S.; Cong, R.; Li, X. Effects of nitrogen and tiller type on grain yield and physiological responses in rice. AoB Plants 2017, 9, plx012. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S. Effects of temperature on growth of the rice plant (Oryza sativa L.) in a controlled environment. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1973, 19, 299–310. [CrossRef]

- Kakizaki, Y. Effect of different temperatures given to the culm-base of rice plant on the emergence and elongation of its tiller under controlled environment. Jpn. J. Crop Sci. 1991, 60, 82–90. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.D. Plant responses to photoperiod. New Phytol. 2009, 181, 517–531. [CrossRef]

- Rameau, C.; Bertheloot, J.; Leduc, N.; Andrieu, B.; Foucher, F.; Sakr, S. Multiple pathways regulate shoot branching. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 741. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Choi, M.; Lee, Y.; Hwang, W.; Jeong, J.; Yang, S.; Lim, Y.; Lee, C.; Choi, K. Temperature-dependent differences in heading response at different growth stages of rice. Korean J. Crop Sci. 2019, 64, 213–224. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Hwang, W.; Jeong, J.; Yang, S.; Jeong, N.; Lee, C.; Choi, M. Physiological causes of transplantation shock on rice growth inhibition and delayed heading. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16818. [CrossRef]

- Hussien, A.; Tavakol, E.; Horner, D.S.; Muñoz-Amatriaín, M.; Muehlbauer, G.J.; Rossini, L. Genetics of tillering in rice and barley. Plant Genome 2014, 7. [CrossRef]

- Nakamichi, N. Adaptation to the local environment by modifications of the photoperiod response in crops. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 594–604. [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, V.; Martignago, D.; Goretti, D.; Cerise, M.; Somssich, M.; de Rosa, M.; Galbiati, F.; Shrestha, R.; Lazzaro, F.; Simon, R.; Fornara, F. Antagonistic transcription factor complexes modulate the floral transition in rice. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 2801–2816. [CrossRef]

- Cho, L.-H.; Yoon, J.; An, G. The control of flowering time by environmental factors. Plant J. 2017, 90, 708–719. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Kang, S.; Choi, J.-S.; Lee, D.-W.; Lee, S.-K.; Chae, M.-J. Heading response of rice varieties under temperature and day-length conditions of low-temperature regions in North Korea. Korean J. Crop Sci. 2021, 66, 190–200.

- Nishida, H.; Okumoto, Y.; Nakagawa, H.; Ichitani, K.; Inoue, H.; Tanisaka, T. Analysis of tester lines for rice (Oryza sativa L.) heading-time genes using reciprocal photoperiodic transfer treatments. Ann. Bot. 2001, 88, 527–536. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Gao, Z.; Luan, W. Interaction between temperature and photoperiod in regulation of flowering time in rice. Sci. China Life Sci. 2012, 55, 241–249. [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, S.; Matsuo, S.; Wong, H.L.; Yokoi, S.; Shimamoto, K. Hd3a protein is a mobile flowering signal in rice. Science 2007, 316, 1033–1036. [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, S.; Tsuji, H.; Matsumoto, A.; Fujita, A.; Shimatani, Z.; Terada, R.; Sakamoto, T.; Kurata, T.; Shimamoto, K. FT-like proteins induce transposon silencing in the shoot apex during floral induction in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015, 112, E901–E910. [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Taoka, K.I.; Shimamoto, K. Regulation of flowering in rice: Two florigen genes, a complex gene network, and natural variation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Andrés, F.; Coupland, G. The genetic basis of flowering responses to seasonal cues. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 627–639. [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, A.; Richter, R. Genetic and molecular basis of floral induction in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 2490–2504. [CrossRef]

- Martignago, D.; Siemiatkowska, B.; Lombardi, A.; Conti, L. Abscisic acid and flowering regulation: Many targets, different places. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9700. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.E.; Farré, A.; Finnegan, E.J.; Orford, S.; Griffiths, S.; Boden, S.A. Developmental responses of bread wheat to changes in ambient temperature following deletion of a locus that includes FLOWERING LOCUS T1. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 1715–1725. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qian, Q.; Fu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, G.; Zeng, D.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Teng, S.; Hiroshi, F.; Yuan, M.; Luo, D.; Han, B.; Li, J. Control of tillering in rice. Nature 2003, 422, 618–621. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Yu, H.; Duan, J.; Yuan, K.; Yu, C.; Meng, X.; Kou, L.; Chen, M.; Jing, Y.; Liu, G.; Smith, S.M.; Li, J. SLR1 inhibits MOC1 degradation to coordinate tiller number and plant height in rice. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2738. [CrossRef]

- Barbier, F.F.; Dun, E.A.; Kerr, S.C.; Chabikwa, T.G.; Beveridge, C.A. An update on the signals controlling shoot branching. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 220–236. [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Li, W.; Miura, K.; Ashikari, M.; Kyozuka, J. Control of tiller growth of rice by OsSPL14 and strigolactones, which work in two independent pathways. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, 1793–1801. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Han, T.; Song, Q.; Ye, W.; Song, X.; Chu, J.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.J. The rice circadian clock regulates tiller growth and panicle development through strigolactone signaling and sugar sensing. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 3124–3138. [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.N.; Prasad, K.; Kumar, P.R.; Vijayraghavan, U. Distinct regulatory role for RFL, the rice LFY homolog, in determining flowering time and plant architecture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 3646–3651. [CrossRef]

- Purwestri, Y.A.; Susanto, F.A.; Tsuji, H. Hd3a florigen recruits different proteins to reveal its function in plant growth and development. In: Jurić, S. (Ed.), Plant Engineering; INTECH Press: Philippines, Pennsylvania, 2017; pp. 49–67.

- Tsuji, H. Molecular function of florigen. Breed. Sci. 2017, 67, 327–332. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Wang, S.; Jiang, H.; Cheng, B.; Wu, K.; Ding, Y. The COMPASS-like complex promotes flowering and panicle branching in rice. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 2761–2771. [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.B.; Barbier, F.F.; Zhao, J.; Zafar, S.A.; Uzair, M.; Sun, Y.; Fang, J.; Perez-Garcia, M.D.; Bertheloot, J.; Sakr, S.; Fichtner, F.; Chabikwa, T.G.; Yuan, S.; Beveridge, C.A.; Li, X. Sucrose promotes D53 accumulation and tillering in rice. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 122–136. [CrossRef]

- Ku, B.-I.; Kang, S.-K.; Sang, W.-G.; Choi, M.-K.; Lee, K.-J.; Park, H.-K.; Kim, Y.-D.; Kim, B.-K.; Lee, J.-H. Variation of panicle differentiation stage by leaf growth according to rice cultivars and transplanting time. Korean J. Crop Sci. 2013, 58, 353–361. [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Tachibana, C.; Tamaki, S.; Taoka, K.-I.; Kyozuka, J.; Shimamoto, K. Hd3a promotes lateral branching in rice. Plant J. 2015, 82, 256–266. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, W.; Chen, X.; Lin, C.; Liu, Y.; Ye, Y.; Wu, W.; Duan, Y. LUX arrhythmo interacts with ELF3a and ELF4a to coordinate vegetative growth and photoperiodic flowering in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 853042. [CrossRef]

- Nagalla, A.D.; Nishide, N.; Hibara, K.-I.; Izawa, T. High ambient temperatures inhibit Ghd7-mediated flowering repression in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 1745–1759. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; An, G. OsGI controls flowering time by modulating rhythmic flowering time regulators preferentially under short day in rice. J. Plant Biol. 2015, 58, 137–145. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Puryear, J.; Cairney, J. A simple and efficient method for isolating RNA from pine trees. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 1993, 11, 113–116. [CrossRef]

- Black, J.W.; Leff, P. Operational models of pharmacological agonism. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1983, 220, 141–162. [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, G.; Hu, Y.; Liu, H.; Bai, X.; Qin, R.; Xing, Y. OsMFT1 increases spikelets per panicle and delays heading date in rice by suppressing Ehd1, FZP, and SEPALLATA-like genes. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 4283–4293. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Han, J.; Li, R.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, C.; Lu, M.; Huang, R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Xie, H.; Li, S.; Huang, X.; Ouyang, X. Gradual daylength sensing coupled with optimum cropping modes enhances multilatitude adaptation of rice and maize. Plant Commun. 2023, 4, 100433. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Vergara, V.S. Studies on responses of the rice plant to photoperiod III. Response of Korean varieties. Korean J. Crop Sci. 1969, 5, 45–50.

- Tsuji, H.; Nakamura, H.; Taoka, K.-I.; Shimamoto, K. Functional diversification of FD transcription factors in rice, components of florigen activation complexes. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 385–397. [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; You, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, S.; Ding, Y. Nitrogen fertilizer increases spikelet number per panicle by enhancing cytokinin synthesis in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2014, 33, 363–371. [CrossRef]

| Varieties | Treatment | Plant height (cm) |

Leaf age (ea) |

Tiller number (ea) |

||||||||||

| Hmax † | rF†† | tm††† | R2 | Lmax † | rF | tm | R2 | Tmax† | rF | tm | R2 | |||

| ‘Odae’ | SD | Control | 89.8 (1.74) |

0.078 (0.007) |

7.2 (0.89) |

0.98 | 13.0 (0.14) |

0.081 (0.005) |

5.6 (0.51) |

0.99 | 15.1 (0.49) |

0.232 (0.051) |

15.7 (1.04) |

0.96 |

| Tiller X | 89.9 (1.71) |

0.082 (0.007) |

8.3 (0.86) |

0.98 | 13.6 (0.19) |

0.079 (0.005) |

7.0 (0.65) |

0.99 | - | - | - | - | ||

| LD | Control | 91.0 (3.89) |

0.057 (0.008) |

9.7 (1.90) |

0.97 | 14.2 (0.17) |

0.066 (0.003) |

9.3 (0.54) |

0.99 | 19.9 (0.47) |

0.294 (0.056) |

16.2 (0.66) |

0.98 | |

| Tiller X | 108.3 (4.29) |

0.054 (0.006) |

15.4 (1.84) |

0.98 | 17.1 (0.21) |

0.058 (0.002) |

14.5 (0.54) |

0.99 | - | - | - | - | ||

| ‘Saenuri’ | SD | Control | 75.3 (1.27) |

0.081 (0.008) |

8.1 (1.06) |

0.97 | 13.1 (0.10) |

0.090 (0.005) |

6.2 (0.52) |

0.99 | 15.7 (0.23) |

0.239 (0.029) |

14.6 (0.56) |

0.98 |

| Tiller X | 72.4 (1.03) |

0.084 (0.008) |

6.4 (0.94) |

0.97 | 13.8 (0.13) |

0.089 (0.006) |

6.4 (0.63) |

0.98 | - | - | - | - | ||

| LD | Control | 86.4 (1.89) |

0.053 (0.004) |

13.8 (1.25) |

0.98 | 16.9 (0.23) |

0.054 (0.003) |

14.3 (0.79) |

0.99 | 19.9 (0.77) |

0.324 (0.123) |

16.2 (1.21) |

0.91 | |

| Tiller X | 107.0 (4.41) |

0.046 (0.005) |

22.6 (2.41) |

0.98 | 18.6 (0.17) |

0.058 (0.002) |

16.0 (0.54) |

0.99 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Varieties | Treatment | Panicle number (ea) |

Spikelet number per panicle (ea) |

Ripened Grain (%)††† |

1000- Grain weight (g)††† |

||||

| ‘Odae’ |

SD |

Control | 13.0a | 56.9c | 95.6a | 28.1a | |||

| Tiller X | 1.0b | 74.1b | 84.3b | 28.1a | |||||

|

LD |

Control | 13.5a | 58.2c | 95.6a | 28.4a | ||||

| Tiller X | 1.0b | 127.1a | 78.5c | 28.4a | |||||

| ‘Saenuri’ |

SD |

Control | 13.8a | 62.2b | 93.8a | 28.9a | |||

| Tiller X | 1.0b | 59.3b | 72.6c | 30.3a | |||||

|

LD |

Control | 14.0a | 69.1b | 89.7a | 28.0a | ||||

| Tiller X | 1.0b | 235.0a | 79.7b | 28.3a | |||||

| Analysis of variance (ANOVA) | |||||||||

| Variety (V) | ns | *** | *** | ns | |||||

| Daylength (D) | ns | *** | ns | ns | |||||

| Tiller (R) | *** | *** | ** | ns | |||||

| Interaction (V*D) | ns | *** | ns | ns | |||||

| Interaction (V*R) | ns | *** | *** | ns | |||||

| Interaction (D*R) | ns | *** | *** | ns | |||||

| Interaction (V*D*R) | ns | *** | *** | ns | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).