Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- In this study, we aim to develop a robust Step Length Estimation (SLE) technique by employing a sequential neural network due to its significant potential to address challenges arising from variations in human gait and waking modes, while also reducing the need for extensive training using large datasets.

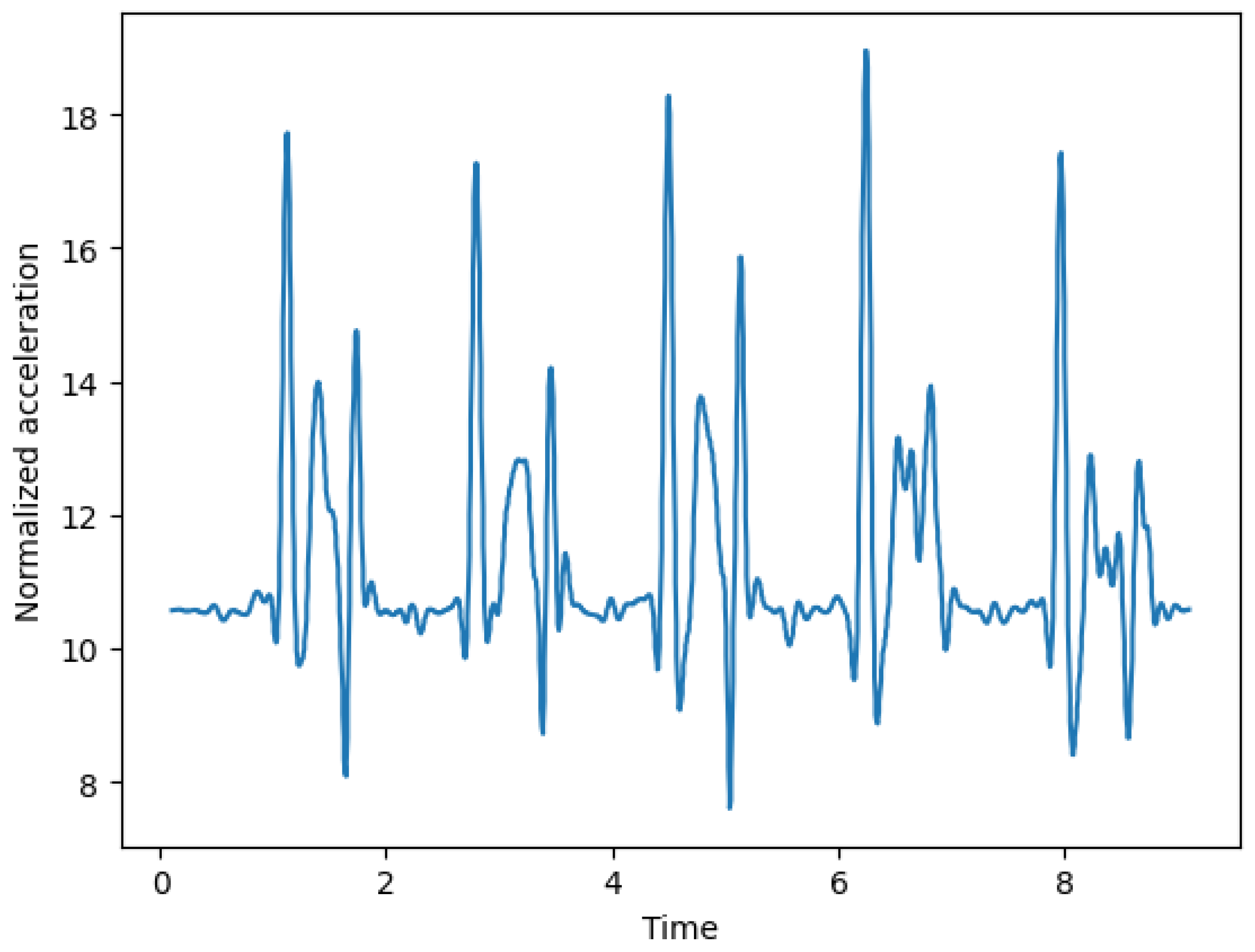

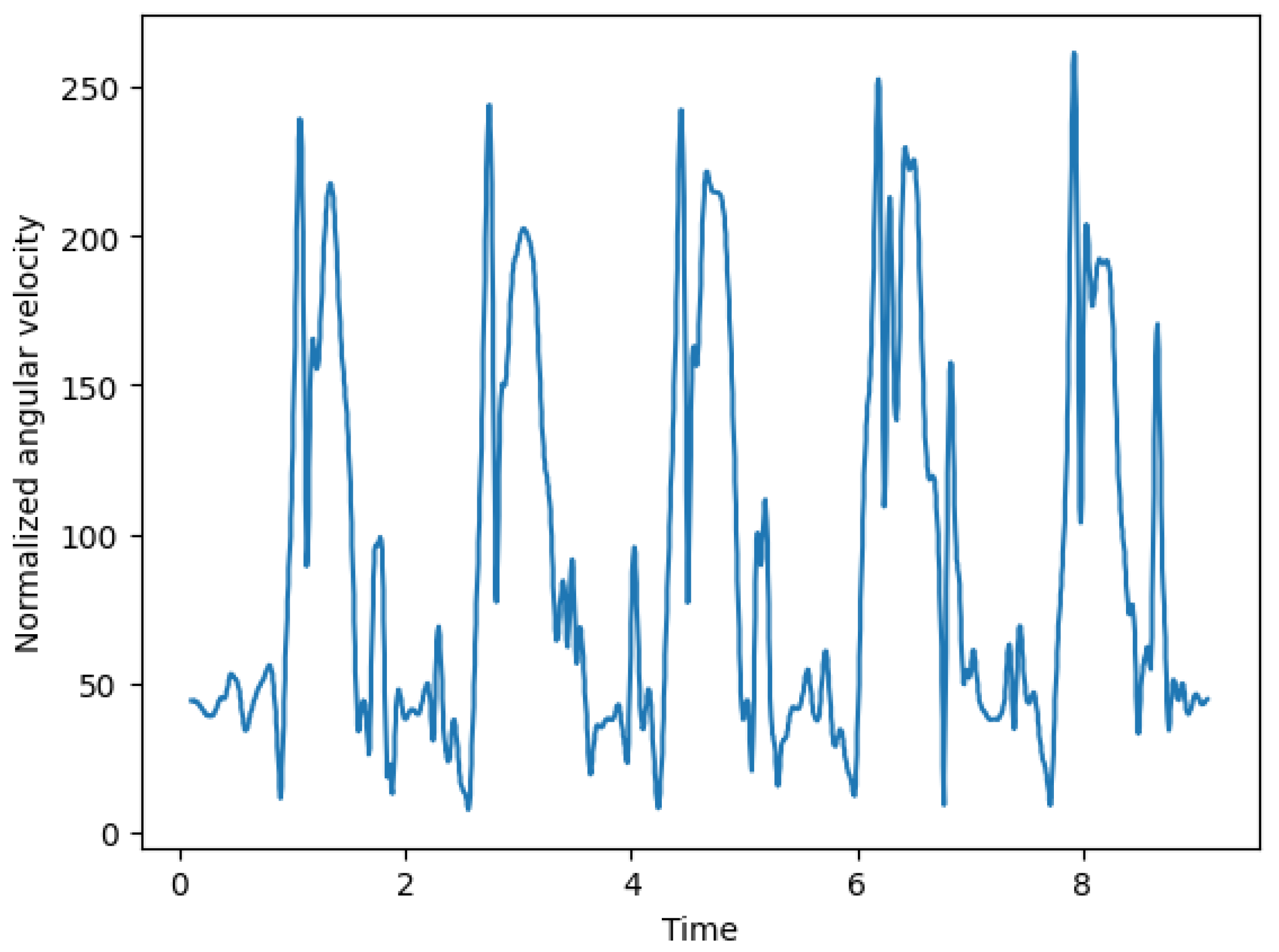

- The proposed SLE model uses a single foot-mounted inertial measurement unit equipped with only a 3D accelerometer and a 3D gyroscope sensor.

- Performance analysis comparing the proposed SLE model to the previously developed traditional SLE method demonstrates that the SNN based proposed SLE model achieves superior performance results [48].

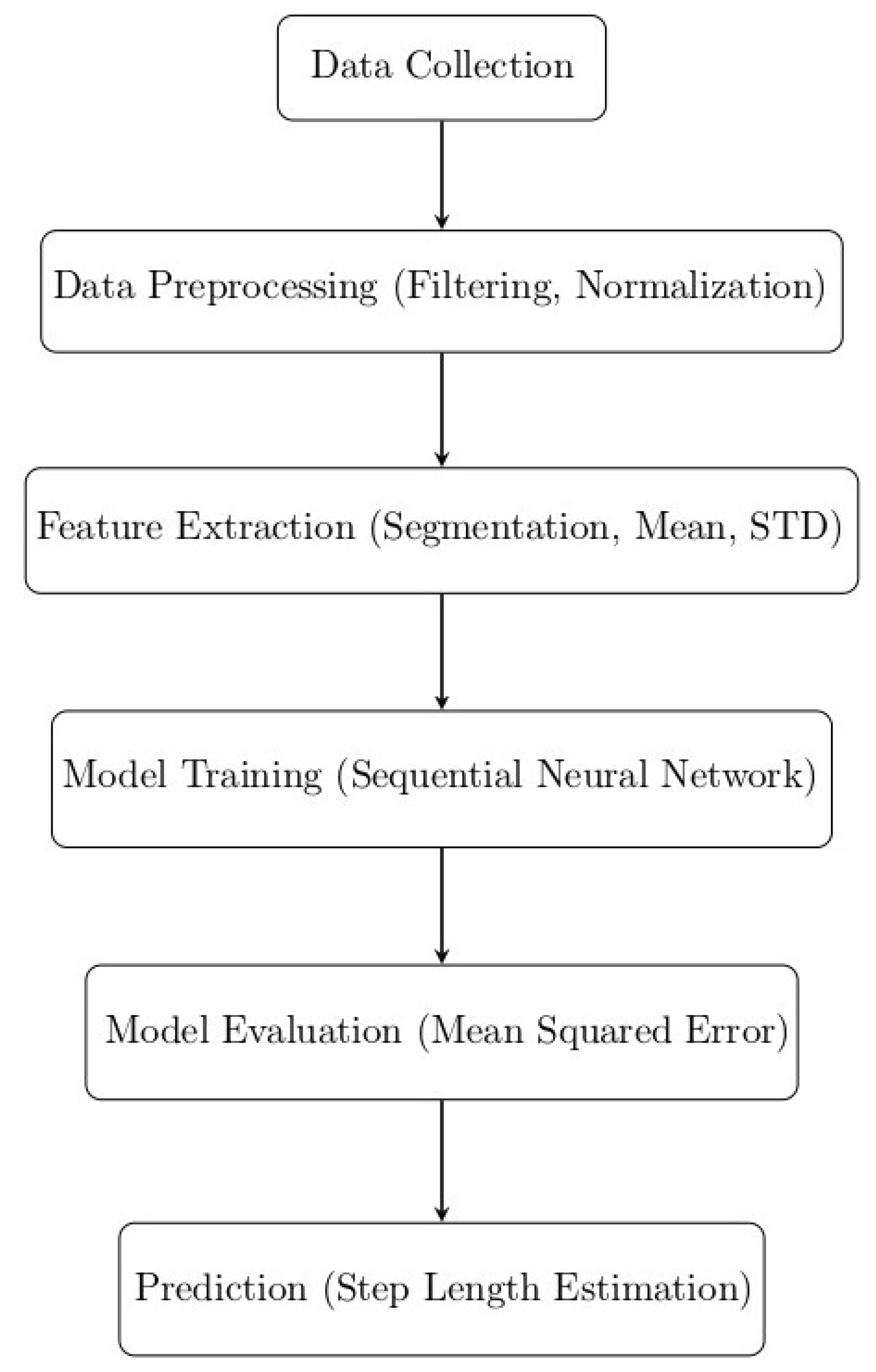

2. Proposed Methodology

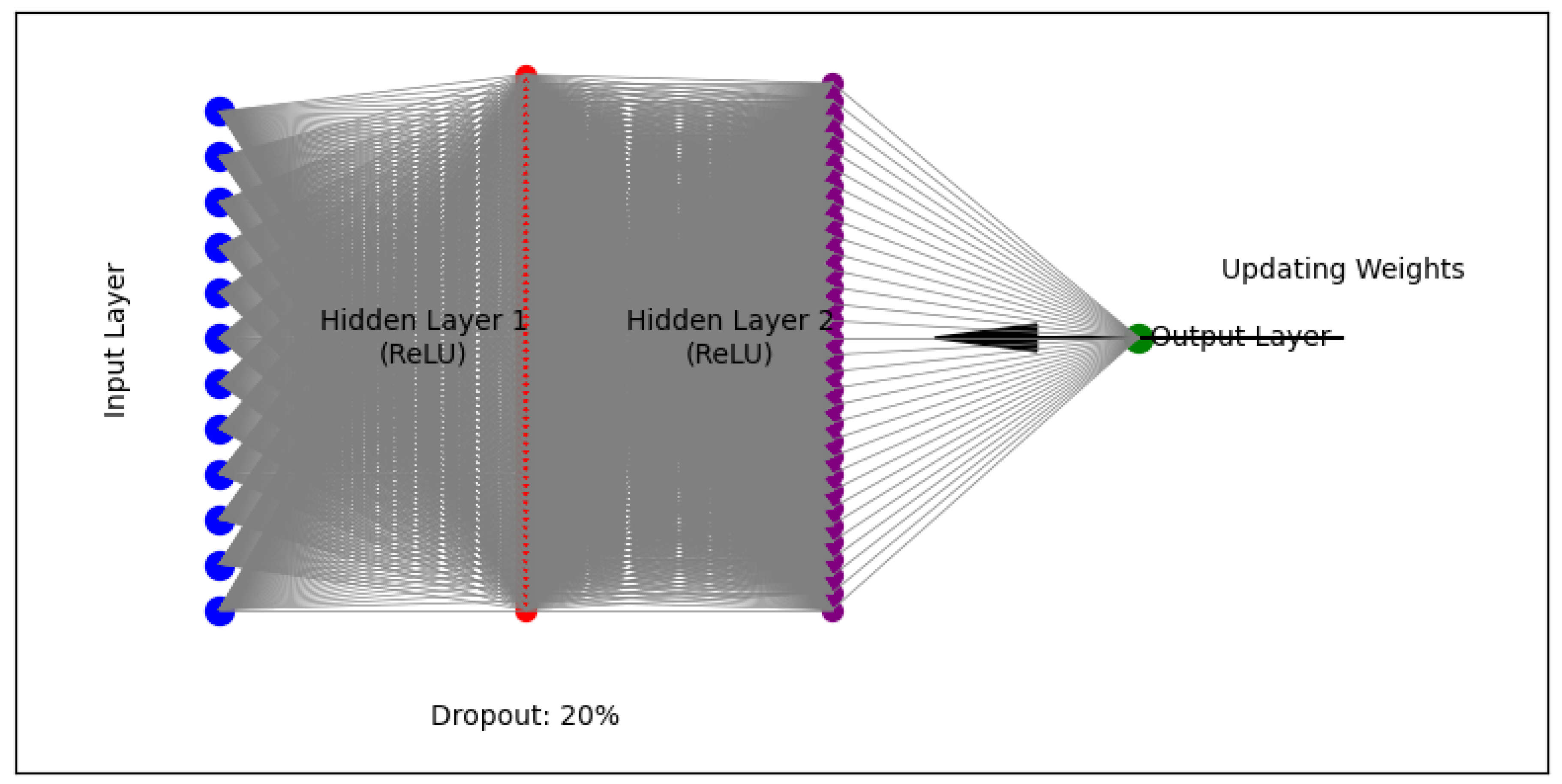

2.1. Functional Architecture of Sequential Neural Network (SNN)

2.1.1. Input Layer

- i.

- Mean acceleration in the x-axis direction denoted by .

- ii.

- Mean acceleration in the y-axis direction denoted by .

- iii.

- Mean acceleration in the z-axis direction denoted by .

- iv.

- Mean angular velocity in the x-axis direction denoted by .

- v.

- Mean angular velocity in the y-axis direction denoted by .

- vi.

- Mean angular velocity in the z-axis direction denoted by .

- vii.

- Standard deviation of acceleration in the x-axis direction denoted by .

- viii.

- Standard deviation of acceleration in the y-axis direction denoted by .

- ix.

- Standard deviation of acceleration in the z-axis direction denoted by .

- x.

- Standard deviation of angular velocity in the x-axis direction denoted by .

- xi.

- Standard deviation of angular velocity in the y-axis direction denoted by .

- xii.

- Standard deviation of angular velocity in the z-axis direction denoted by .

- xiii.

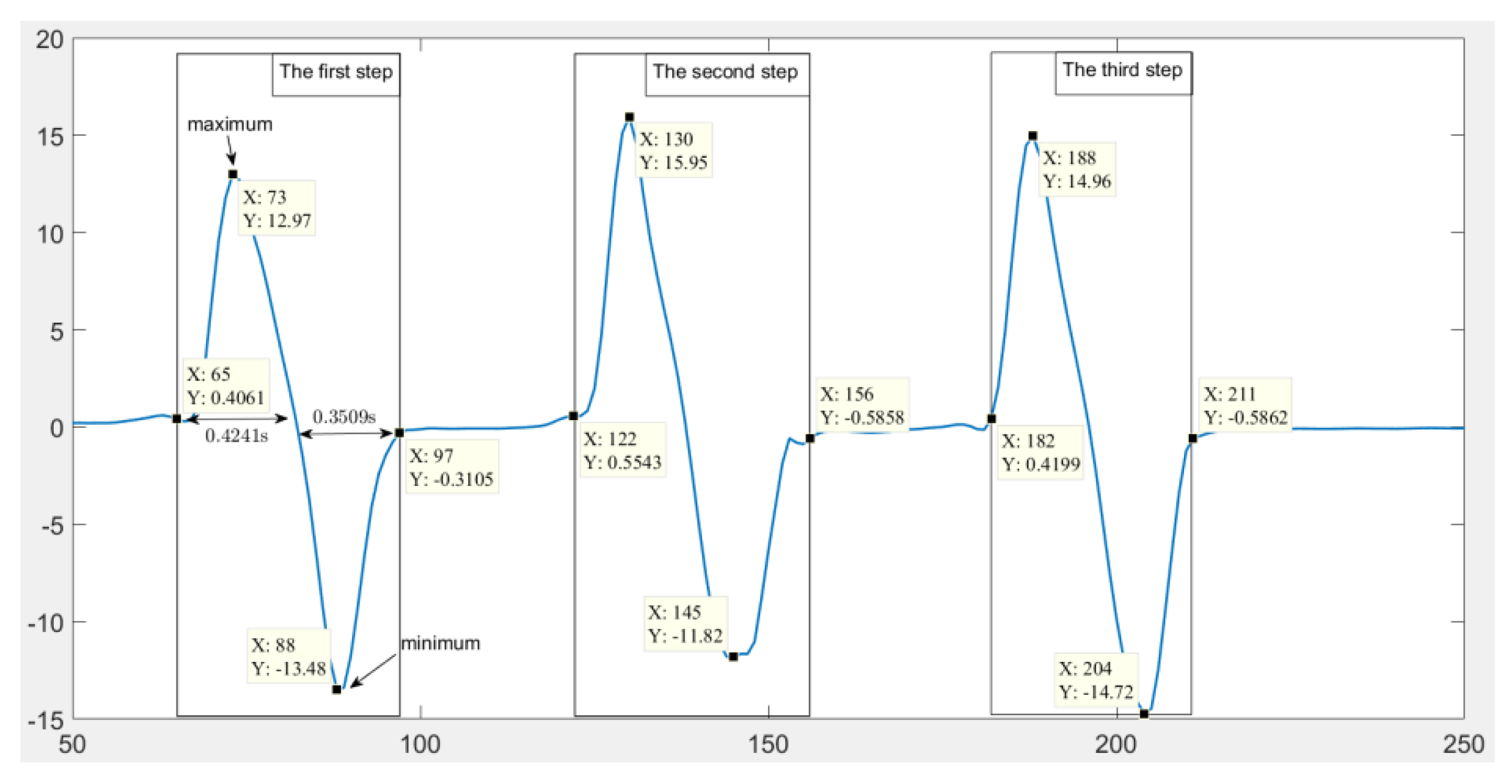

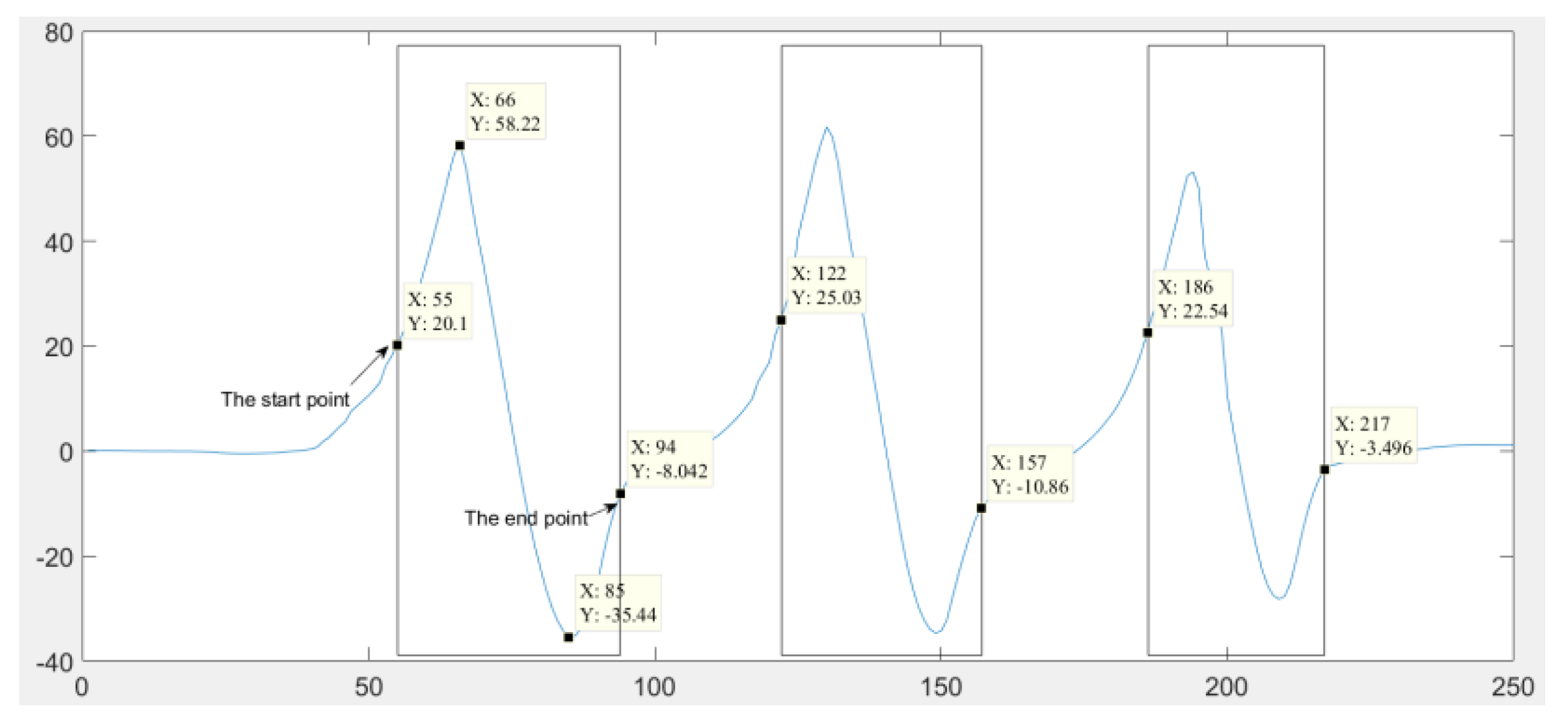

- Stride duration () - it represents the duration of each stride segment in seconds and is calculated as follows.where is the number of samples in the current stride segment and is the sampling frequency of the data, which is the number of samples per second.

- xiv.

- Stride frequency () - it represents the frequency of the stride segment, i.e., the number of strides per second. It is the reciprocal of the stride duration and thus, is calculated as

2.1.2. Hidden Layer

2.1.3. Output Layer

2.2. Working Procedure of Proposed SLE

2.2.1. Step 1: Data Collection

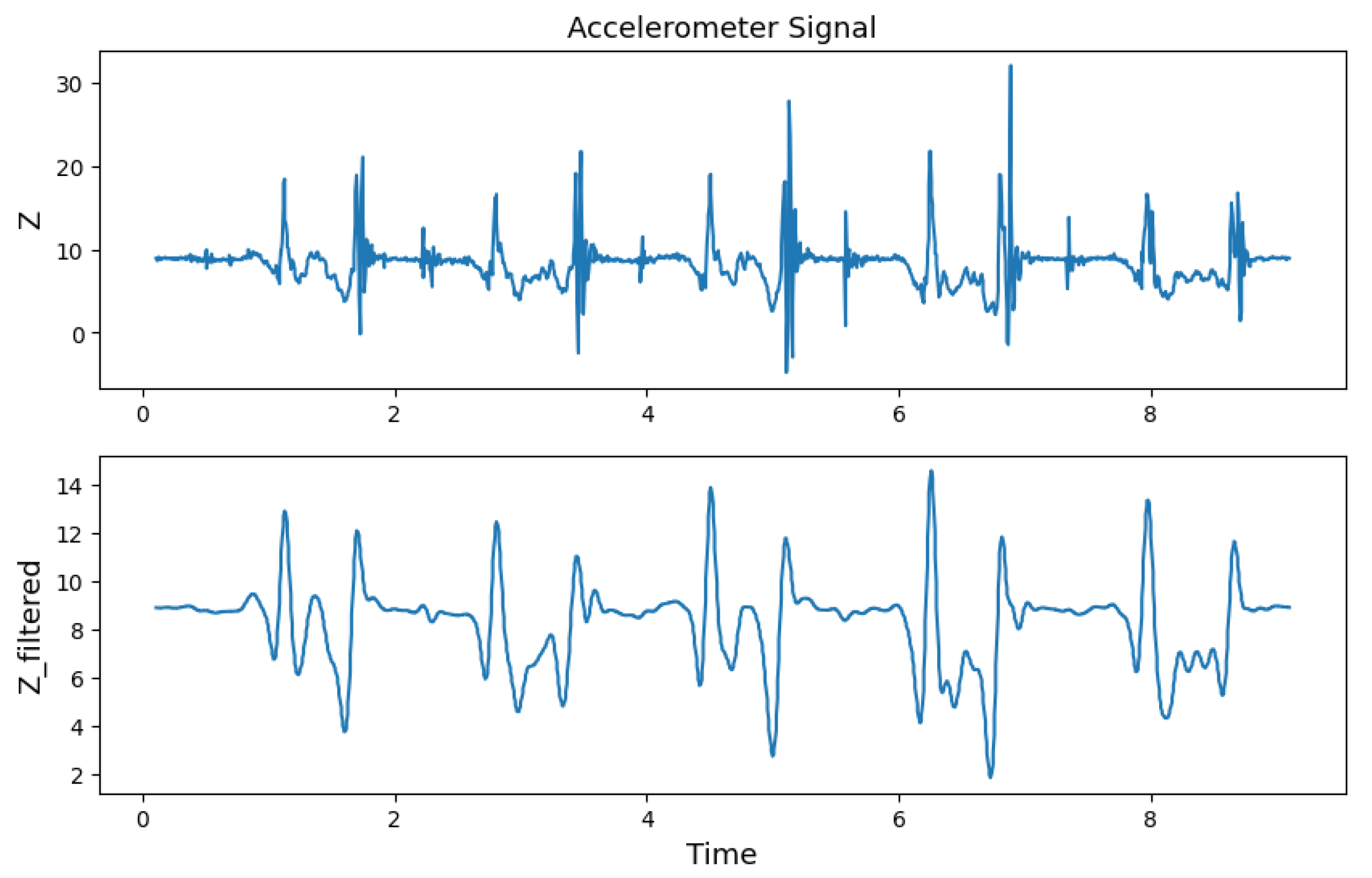

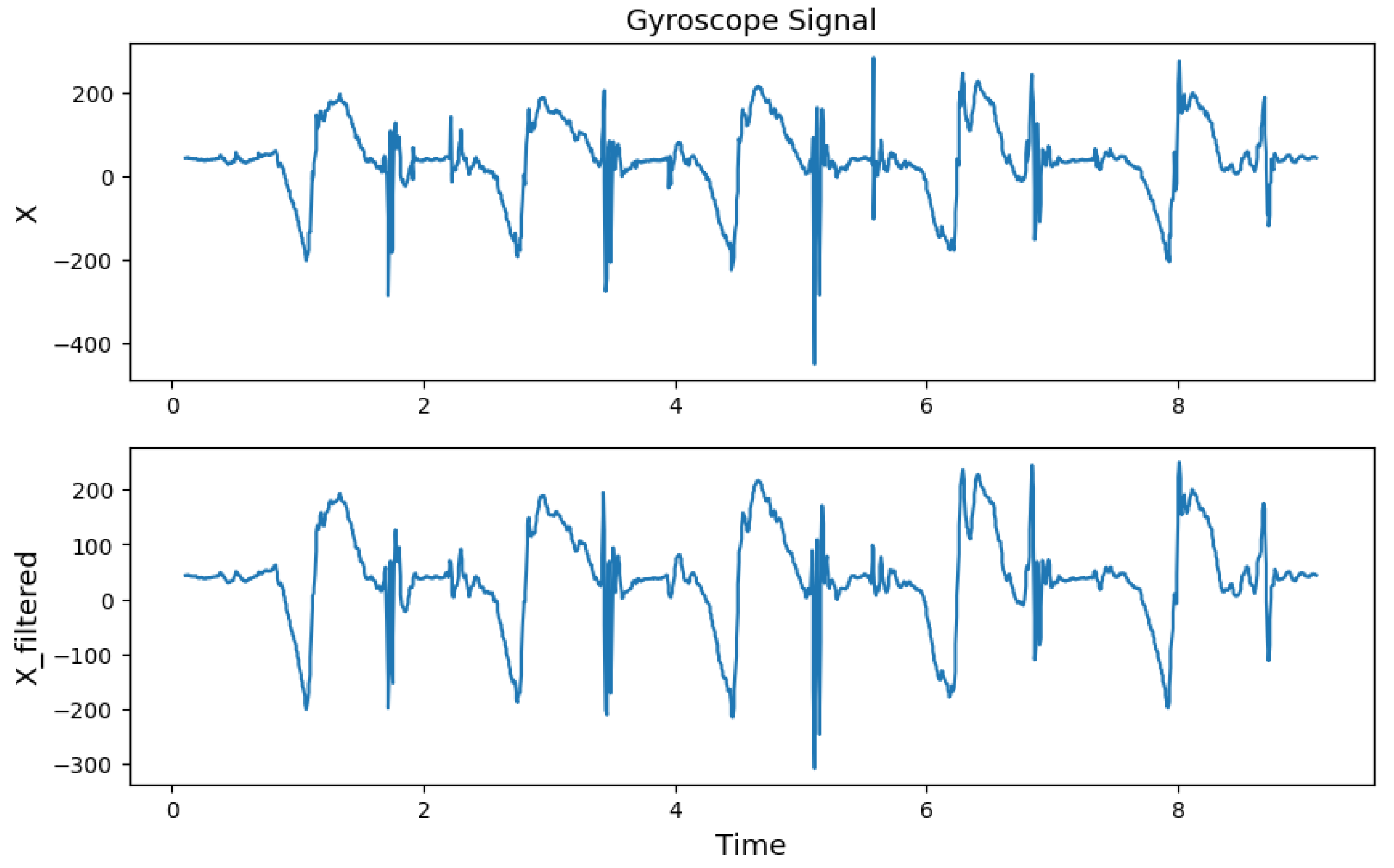

2.2.2. Step 2: Data Preprocessing

2.2.3. Step 3: Feature Extraction

2.2.4. Step 4: Model Training

2.2.5. Step 5: Model Evaluation

2.2.6. Step 6: Prediction of Step Length

3. Experimental Results and Discussions

| Participant | Walking | Average Step | Average | Height (m) | Weight (kg) | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Distance (m) | Length (m) | MSE loss | |||

| 1 | 60.2 | 0.599 | 0.03 | 1.706 | 80 | M |

| 2 | 60.2 | 0.593 | 0.03 | 1.706 | 67 | M |

| 3 | 60.4 | 0.667 | 0.06 | 1.803 | 75 | M |

| 4 | 60.1 | 0.628 | 0.04 | 1.803 | 57 | M |

| 5 | 59.8 | 0.609 | 0.07 | 1.706 | 58 | M |

| 6 | 60.3 | 0.591 | 0.06 | 1.706 | 60 | M |

| 7 | 60.4 | 0.612 | 0.04 | 1.625 | 56 | M |

| 8 | 60.6 | 0.552 | 0.03 | 1.574 | 40 | F |

| 9 | 59.9 | 0.562 | 0.08 | 1.752 | 70 | M |

| 10 | 60.8 | 0.588 | 0.02 | 1.706 | 70 | M |

| Participant | Walking | Average Step | Average | Height (m) | Weight (kg) | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Distance (m) | Length (m) | MSE loss | |||

| 1 | 60.4 | 0.703 | 0.07 | 1.706 | 80 | M |

| 2 | 60.7 | 0.666 | 0.08 | 1.706 | 67 | M |

| 3 | 60.3 | 0.701 | 0.08 | 1.803 | 75 | M |

| 4 | 60.9 | 0.738 | 0.04 | 1.803 | 57 | M |

| 5 | 60.4 | 0.679 | 0.07 | 1.706 | 58 | M |

| 6 | 60.8 | 0.612 | 0.06 | 1.706 | 60 | M |

| 7 | 60.7 | 0.674 | 0.08 | 1.625 | 56 | M |

| 8 | 59.8 | 0.601 | 0.07 | 1.574 | 40 | F |

| 9 | 59.6 | 0.672 | 0.08 | 1.752 | 70 | M |

| 10 | 60.7 | 0.702 | 0.09 | 1.706 | 70 | M |

| Participant No. | Peak-Valley detection method (%) | SNN based method (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 92.03 | 99.61 |

| 2 | 92.27 | 99.52 |

| 3 | 98.29 | 99.76 |

| 4 | 97.44 | 99.55 |

| 5 | 96.54 | 99.78 |

| 6 | 93.83 | 99.68 |

| 7 | 98.31 | 99.46 |

| 8 | 88.35 | 99.78 |

| 9 | 93.68 | 99.52 |

| 10 | 98.29 | 99.67 |

| Participant No. | Peak-Valley detection method (%) | SNN based method (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 96.62 | 99.52 |

| 2 | 96.4 | 99.55 |

| 3 | 93.43 | 99.46 |

| 4 | 98.37 | 99.61 |

| 5 | 97.6 | 99.52 |

| 6 | 92.77 | 99.56 |

| 7 | 97.79 | 99.67 |

| 8 | 93.94 | 99.61 |

| 9 | 96.3 | 99.46 |

| 10 | 94.78 | 99.52 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- N. A. Abiad, Y. Kone, V. Renaudin and T. Robert, "Smartstep: A Robust STEP Detection Method Based on SMARTphone Inertial Signals Driven by Gait Learning," in IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 22, no. 12, pp. 12288-12297, 15 June15, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nahime Al Abiad, Enguerran Houdry, Carlos El Khoury, Valerie Renaudin, Thomas Robert, A method for calculating fall risk parameters from discrete stride time series regardless of sensor placement, Gait & Posture, Volume 111, 2024, Pages 182-184, ISSN 0966-6362. [CrossRef]

- Kelly A. Hawkins, Emily J. Fox, Janis J. Daly, Dorian K. Rose, Evangelos A. Christou, Theresa E. McGuirk, Dana M. Otzel, Katie A. Butera, Sudeshna A. Chatterjee, David J. Clark, Prefrontal over-activation during walking in people with mobility deficits: Interpretation and functional implications, Human Movement Science, Volume 59, 2018, Pages 46-55, ISSN 0167-9457. [CrossRef]

- Poleur M, Markati T, Servais L. The use of digital outcome measures in clinical trials in rare neurological diseases: a systematic literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023 Aug 2;18(1):224. doi: 10.1186/s13023-023-02813-3. PMID: 37533072; PMCID: PMC10398976.

- S. V. Perumal and R. Sankar, "Gait monitoring system for patients with Parkinson’s disease using wearable sensors," 2016 IEEE Healthcare Innovation Point-Of-Care Technologies Conference (HI-POCT), Cancun, Mexico, 2016, pp. 21-24, doi: 10.1109/HIC.2016.7797687.

- Helena R. Gonçalves, Ana Rodrigues, Cristina P. Santos, Gait monitoring system for patients with Parkinson’s disease, Expert Systems with Applications, Volume 185, 2021, 115653, ISSN 0957-4174. [CrossRef]

- Hopin Lee, S. John Sullivan, Anthony G. Schneiders, The use of the dual-task paradigm in detecting gait performance deficits following a sports-related concussion: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, Volume 16, Issue 1, 2013, Pages 2-7, ISSN 1440-2440. [CrossRef]

- Angkoon Phinyomark, Sean Osis, Blayne A. Hettinga, Reed Ferber, Kinematic gait patterns in healthy runners: A hierarchical cluster analysis, Journal of Biomechanics, Volume 48, Issue 14, 2015, Pages 3897-3904, ISSN 0021-9290. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tong, H. Liu and Z. Zhang, "Advancements in Humanoid Robots: A Comprehensive Review and Future Prospects," in IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 301-328, February 2024, doi: 10.1109/JAS.2023.124140.

- Alexander Kvist, Fredrik Tinmark, Lucian Bezuidenhout, Mikael Reimeringer, David Moulaee Conradsson, Erika Franzén, Validation of algorithms for calculating spatiotemporal gait parameters during continuous turning using lumbar and foot mounted inertial measurement units, Journal of Biomechanics, Volume 162, 2024, 111907, ISSN 0021-9290.

- Guimarães, Vânia, Inês Sousa, and Miguel Velhote Correia. 2021. "A Deep Learning Approach for Foot Trajectory Estimation in Gait Analysis Using Inertial Sensors" Sensors 21, no. 22: 7517. [CrossRef]

- Hyang Jun Lee, Ji Sun Park, Hee Won Yang, Jeong Wook Shin, Ji Won Han, Ki Woong Kim, A normative study of the gait features measured by a wearable inertia sensor in a healthy old population, Gait & Posture, Volume 103, 2023, Pages 32-36, ISSN 0966-6362. [CrossRef]

- Rampp, A.; Barth, J.; Schülein, S.; Gaßmann, K.G.; Klucken, J.; Eskofier, B.M. Inertial Sensor-Based Stride Parameter Calculation From Gait Sequences in Geriatric Patients. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 62, 1089–1097.

- Chen, B.R.; Patel, S.; Buckley, T.; Rednic, R.; McClure, D.J.; Shih, L.; Tarsy, D.; Welsh, M.; Bonato, P. A web-based system for home monitoring of patients with Parkinson’s disease using wearable sensors. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 58, 831–836.

- Kluge, F.; Gaßner, H.; Hannink, J.; Pasluosta, C.; Klucken, J.; Eskofier, B.M. Towards Mobile Gait Analysis: Concurrent Validity and Test-Retest Reliability of an Inertial Measurement System for the Assessment of Spatio-Temporal Gait Parameters. Sensors 2017, 17, 1522.

- H. Xu, F. Meng, H. Liu, H. Shao and L. Sun, "An Adaptive Multi-Source Data Fusion Indoor Positioning Method Based on Collaborative Wi-Fi Fingerprinting and PDR Techniques," in IEEE Sensors Journal, doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2024.3443096.

- P. Sadhukhan et al., "IRT-SD-SLE: An Improved Real-Time Step Detection and Step Length Estimation Using Smartphone Accelerometer," in IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 23, no. 24, pp. 30858-30868, 15 Dec.15, 2023, doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2023.3330097.

- Y. Jiang, Z. Li and J. Wang, "PTrack: Enhancing the Applicability of Pedestrian Tracking with Wearables," 2017 IEEE 37th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017, pp. 2193-2199, doi: 10.1109/ICDCS.2017.111.

- J. -S. Hu, K. -C. Sun and C. -Y. Cheng, "A Kinematic Human-Walking Model for the Normal-Gait-Speed Estimation Using Tri-Axial Acceleration Signals at Waist Location," in IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, vol. 60, no. 8, pp. 2271-2279, Aug. 2013, doi: 10.1109/TBME.2013.2252345.

- D. Alvarez, R. C. Gonzalez, A. Lopez and J. C. Alvarez, "Comparison of Step Length Estimators from Weareable Accelerometer Devices," 2006 International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, New York, NY, USA, 2006, pp. 5964-5967, doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2006.259593.

- R. C. Gonzalez, D. Alvarez, A. M. Lopez and J. C. Alvarez, "Modified Pendulum Model for Mean Step Length Estimation," 2007 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Lyon, France, 2007, pp. 1371-1374, doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2007.4352553.

- S. H. Shin, C. G. Park, J. W. Kim, H. S. Hong and J. M. Lee, "Adaptive Step Length Estimation Algorithm Using Low-Cost MEMS Inertial Sensors," 2007 IEEE Sensors Applications Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 2007, pp. 1-5, doi: 10.1109/SAS.2007.374406.

- Zhang, Honghui, Jinyi Zhang, Duo Zhou, Wei Wang, Jianyu Li, Feng Ran and Yuan Ji. “Axis-Exchanged Compensation and Gait Parameters Analysis for High Accuracy Indoor Pedestrian Dead Reckoning.” J. Sensors 2015 (2015): 915837:1-915837:13.

- Y. Yao, L. Pan, W. Fen, X. Xu, X. Liang and X. Xu, "A Robust Step Detection and Stride Length Estimation for Pedestrian Dead Reckoning Using a Smartphone," in IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 20, no. 17, pp. 9685-9697, 1 Sept.1, 2020, doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2020.2989865.

- Kim, Jeong Won, Han Jin Jang, Dong-Hwan Hwang and Chansik Park. “A Step, Stride and Heading Determination for the Pedestrian Navigation System.” Journal of Global Positioning Systems 01 (2004): 0-0.

- I. Bylemans, M. Weyn and M. Klepal, "Mobile Phone-Based Displacement Estimation for Opportunistic Localisation Systems," 2009 Third International Conference on Mobile Ubiquitous Computing, Systems, Services and Technologies, Sliema, Malta, 2009, pp. 113-118, doi: 10.1109/UBICOMM.2009.23.

- Wang, Qu, Langlang Ye, Haiyong Luo, Aidong Men, Fang Zhao, and Changhai Ou. 2019. "Pedestrian Walking Distance Estimation Based on Smartphone Mode Recognition" Remote Sensing 11, no. 9: 1140. [CrossRef]

- T. Cover and P. Hart, "Nearest neighbor pattern classification," in IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 21-27, January 1967, doi: 10.1109/TIT.1967.1053964.

- Cortes, C., Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach Learn 20, 273–297 (1995). [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of decision trees. Mach Learn 1, 81–106 (1986). [CrossRef]

- Freund, Yoav and Robert E. Schapire. “Experiments with a New Boosting Algorithm.” International Conference on Machine Learning (1996).

- Ke, Guolin, Qi Meng, Thomas Finley, Taifeng Wang, Wei Chen, Weidong Ma, Qiwei Ye and Tie-Yan Liu. “LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree.” Neural Information Processing Systems (2017).

- Tianqi Chen and Carlos Guestrin. 2016. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’16). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 785–794. [CrossRef]

- N. -y. Liang, G. -b. Huang, P. Saratchandran and N. Sundararajan, "A Fast and Accurate Online Sequential Learning Algorithm for Feedforward Networks," in IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 1411-1423, Nov. 2006, doi: 10.1109/TNN.2006.880583.

- M. Zhang, Y. Wen, J. Chen, X. Yang, R. Gao and H. Zhao, "Pedestrian Dead-Reckoning Indoor Localization Based on OS-ELM," in IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 6116-6129, 2018, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2791579.

- Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P., Brox, T. (2015). U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In: Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W., Frangi, A. (eds) Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015. MICCAI 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 9351. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- J. -D. Sui and T. -S. Chang, "IMU Based Deep Stride Length Estimation With Self-Supervised Learning," in IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 7380-7387, 15 March 15, 2021, doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2021.3049523.

- Paper, D. (2021). Stacked Autoencoders. In: State-of-the-Art Deep Learning Models in TensorFlow. Apress, Berkeley, CA. [CrossRef]

- F. Gu, K. Khoshelham, C. Yu and J. Shang, "Accurate Step Length Estimation for Pedestrian Dead Reckoning Localization Using Stacked Autoencoders," in IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 68, no. 8, pp. 2705-2713, Aug. 2019, doi: 10.1109/TIM.2018.2871808.

- S. Hochreiter and J. Schmidhuber, "Long Short-Term Memory," in Neural Computation, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 1735-1780, 15 Nov. 1997, doi: 10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735.

- Z. Ping, M. Zhidong, W. Pengyu and D. Zhihong, "Pedestrian Stride-Length Estimation Based on Bidirectional LSTM Network," 2020 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Shanghai, China, 2020, pp. 3358-3363, doi: 10.1109/CAC51589.2020.9327734.

- Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey E. Hinton. 2017. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 60, 6 (June 2017), 84–90. [CrossRef]

- H. Jin, I. Kang, G. Choi, D. D. Molinaro and A. J. Young, "Wearable Sensor-Based Step Length Estimation During Overground Locomotion Using a Deep Convolutional Neural Network," 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Mexico, 2021, pp. 4897-4900, doi: 10.1109/EMBC46164.2021.9630060.

- Wang, Qu, Langlang Ye, Haiyong Luo, Aidong Men, Fang Zhao, and Yan Huang. 2019. "Pedestrian Stride-Length Estimation Based on LSTM and Denoising Autoencoders" Sensors 19, no. 4: 840. [CrossRef]

- Pascal Vincent, Hugo Larochelle, Yoshua Bengio, and Pierre-Antoine Manzagol. 2008. Extracting and composing robust features with denoising autoencoders. In Proceedings of the 25th international conference on Machine learning (ICML ’08). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1096–1103. [CrossRef]

- J. Park, J. Hong Lee and C. Gook Park, "Pedestrian Stride Length Estimation Based on Bidirectional LSTM and CNN Architecture," in IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 124718-124728, 2024, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3454049.

- Sutskever, I., Vinyals, O., & Le, Q. V. (2014). Sequence to Sequence Learning with Neural Networks. Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2014), 3104-3112.

- Sadhukhan, Pampa, Bibhas Gayen, Chandreyee Chowdhury, Nandini Mukherjee, Xinheng Wang, and Pradip K. Das. "Human Gait Modeling with Step Length Estimation based on Single Foot Mounted Inertial Sensors." Available at SSRN 4830580 (2024), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4830580.

- S. Butterworth, "On the Theory of Filter Amplifiers," Wireless Engineer, vol. 7, no. 10, pp. 536-541, 1930.

- T. Hastie, R. Tibshirani, and J. Friedman, The Elements of Statistical Learning, Springer, 2009.

- S. B. Kotsiantis. 2007. Supervised Machine Learning: A Review of Classification Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2007 conference on Emerging Artificial Intelligence Applications in Computer Engineering: Real Word AI Systems with Applications in eHealth, HCI, Information Retrieval and Pervasive Technologies. IOS Press, NLD, 3–24.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).