Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

3. Results & Discussions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flavell, S.W. , et al., The emergence and influence of internal states. Neuron, 2022. 110(16): p. 2545-2570.

- Brand, M.D. , et al., The role of mitochondrial function and cellular bioenergetics in ageing and disease. Br J Dermatol, 2013. 169 Suppl 2(0 2): p. 1-8.

- Eaton, A.F. M. Merkulova, and D. Brown, The H(+)-ATPase (V-ATPase): from proton pump to signaling complex in health and disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 2021. 320(3): p. C392-c414. [CrossRef]

- Muench, S.P., J. Trinick, and M.A. Harrison, Structural divergence of the rotary ATPases. Q Rev Biophys, 2011. 44(3): p. 311-56.

- Kellokumpu, S. , Golgi pH, ion and redox homeostasis: how much do they really matter? Frontiers in cell and developmental biology, 2019. 7: p. 93.

- Colacurcio, D.J. and R.A. Nixon, Disorders of lysosomal acidification—The emerging role of v-ATPase in aging and neurodegenerative disease. Ageing Research Reviews, 2016. 32: p. 75-88.

- Mindell, J.A. , Lysosomal Acidification Mechanisms*. Annual Review of Physiology, 2012. 74(Volume 74, 2012): p. 69-86.

- Hnasko, T.S. and R.H. Edwards, Neurotransmitter Corelease: Mechanism and Physiological Role. Annual Review of Physiology, 2012. 74(Volume 74, 2012): p. 225-243.

- Breton, S. and D. Brown, Regulation of Luminal Acidification by the V-ATPase. Physiology, 2013. 28(5): p. 318-329. [CrossRef]

- Casey, J.R., S. Grinstein, and J. Orlowski, Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2010. 11(1): p. 50-61.

- Paroutis, P., N. Touret, and S. Grinstein, The pH of the secretory pathway: Measurement, determinants, and regulation. Physiology, 2004. 19(4): p. 207-215.

- Maxfield, F.R. and T.E. McGraw, Endocytic recycling. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2004. 5(2): p. 121-132.

- Naslavsky, N. and S. Caplan, The enigmatic endosome - Sorting the ins and outs of endocytic trafficking. Journal of Cell Science, 2018. 131(13).

- Forgac, M. , Vacuolar ATPases: rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2007. 8(11): p. 917-929.

- Williamson, W.R. and P.R. Hiesinger, On the role of v-ATPase V0a1-dependent degradation in Alzheimer disease. Commun Integr Biol, 2010. 3(6): p. 604-7.

- Bagh, M.B. , et al., Misrouting of v-ATPase subunit V0a1 dysregulates lysosomal acidification in a neurodegenerative lysosomal storage disease model. Nature Communications, 2017. 8.

- Dow, J.A. , The multifunctional Drosophila melanogaster V-ATPase is encoded by a multigene family. J Bioenerg Biomembr, 1999. 31(1): p. 75-83.

- Lee, S.-K. , et al., Vacuolar (H+)-ATPases in Caenorhabditis elegans: What can we learn about giant H+ pumps from tiny worms? Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics, 2010. 1797(10): p. 1687-1695.

- Dow, J. , et al., Molecular genetic analysis of V-ATPase function in Drosophila Melanogaster. The Journal of experimental biology, 1997. 200: p. 237-45.

- Wieczorek, H. , et al., Vacuolar-type proton pumps in insect epithelia. Journal of Experimental Biology, 2009. 212(11): p. 1611-1619.

- Sun-Wada, G.-H. and Y. Wada, Role of vacuolar-type proton ATPase in signal transduction. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics, 2015. 1847(10): p. 1166-1172.

- Ramsay, J.A. , Active Transport of Potassium by the Malpighian Tubules of Insects. Journal of Experimental Biology, 1953. 30(3): p. 358-369.

- Wolfersberger, M.G., W. R. Harvey, and M. Cioffi, Chapter 6 Transepithelial Potassium Transport in Insect Midgut by an Electrogenic Alkali Metal Ion Pump, in Current Topics in Membranes and Transport, A. Kleinzeller, F. Bronner, and C.L. Slayman, Editors. 1982, Academic Press. p. 109-133.

- Harvey, W.R., M. Cioffi, and M.G. Wolfersberger, Chemiosmotic potassium ion pump of insect epithelia. Am J Physiol, 1983. 244(2): p. R163-75.

- Harvey, W.R. , et al., H + V-ATPases Energize Animal Plasma Membranes for Secretion and Absorption of Ions and Fluids'. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 1998. 38: p. 426-441.

- Wieczorek, H. , et al., A vacuolar-type proton pump energizes K+/H+ antiport in an animal plasma membrane. J Biol Chem, 1991. 266(23): p. 15340-7.

- Klein, U. and B. Zimmermann, The vacuolar-type ATPase from insect plasma membrane: immunocytochemical localization in insect sensilla. Cell and Tissue Research, 1991. 266(2): p. 265-273.

- Klein, U., G. Löffelmann, and H. Wieczorek, The Midgut as a Model System for Insect K+-Transporting Epithelia: Immunocytochemical Localization of a Vacuolar-Type H+ Pump. Journal of Experimental Biology, 1991. 161(1): p. 61-75.

- Thurm, U. and J. Küppers, Epithelial physiology of insect sensilla, in Insect biology in the future. 1980, Elsevier. p. 735-763.

- Wieczorek, H. , et al., A Vacuolar-type Proton Pump in a Vesicle Fraction Enriched with Potassium Transporting Plasma Membranes from Tobacco Hornworm Midgut. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1989. 264(19): p. 11143-11148.

- Küppers, J. and I. Bunse, A Primary Cation Transport by a V-Type Atpase of Low Specificity. Journal of Experimental Biology, 1996. 199(6): p. 1327-1334.

- Weng, X.-H. , et al., The V-type H+-ATPase in Malpighian tubules of Aedes aegypti: localization and activity. Journal of Experimental Biology, 2003. 206: p. 2211 - 2219.

- Davies, S.A. , et al., Analysis and inactivation of vha55, the gene encoding the vacuolar ATPase B-subunit in Drosophila melanogaster reveals a larval lethal phenotype. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1996. 271(48): p. 30677-30684.

- Nava Gonzales, C. , et al., Systematic morphological and morphometric analysis of identified olfactory receptor neurons in Drosophila melanogaster. eLife, 2021. 10: p. e69896.

- Shanbhag, S.R., B. Müller, and R.A. Steinbrecht, Atlas of olfactory organs of Drosophila melanogaster: 1. Types, external organization, innervation and distribution of olfactory sensilla. International Journal of Insect Morphology and Embryology, 1999. 28(4): p. 377-397.

- Shanbhag, S.R., B. Müller, and R.A. Steinbrecht, Atlas of olfactory organs of Drosophila melanogaster: 2. Internal organization and cellular architecture of olfactory sensilla. Arthropod Structure & Development, 2000. 29(3): p. 211-229.

- Shanbhag, S.R., B. Müller, and R.A. Steinbrecht, Atlas of olfactory organs of Drosophila melanogaster 2. Internal organization and cellular architecture of olfactory sensilla. Arthropod Struct Dev, 2000. 29(3): p. 211-29.

- Vosshall, L.B. and R.F. Stocker, Molecular architecture of smell and taste in Drosophila. Annu Rev Neurosci, 2007. 30: p. 505-33.

- Prelic, S. , et al., Functional Interaction Between Drosophila Olfactory Sensory Neurons and Their Support Cells. Front Cell Neurosci, 2021. 15: p. 789086.

- Neuhaus, E.M. , et al., Odorant receptor heterodimerization in the olfactory system of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature Neuroscience, 2005. 8(1): p. 15-17.

- Vosshall, L.B. and B.S. Hansson, A Unified Nomenclature System for the Insect Olfactory Coreceptor. Chemical Senses, 2011. 36(6): p. 497-498.

- Dow, J.A.T. , V-ATPases in Insects, in Organellar Proton-ATPases. 1995, Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg. p. 75-102.

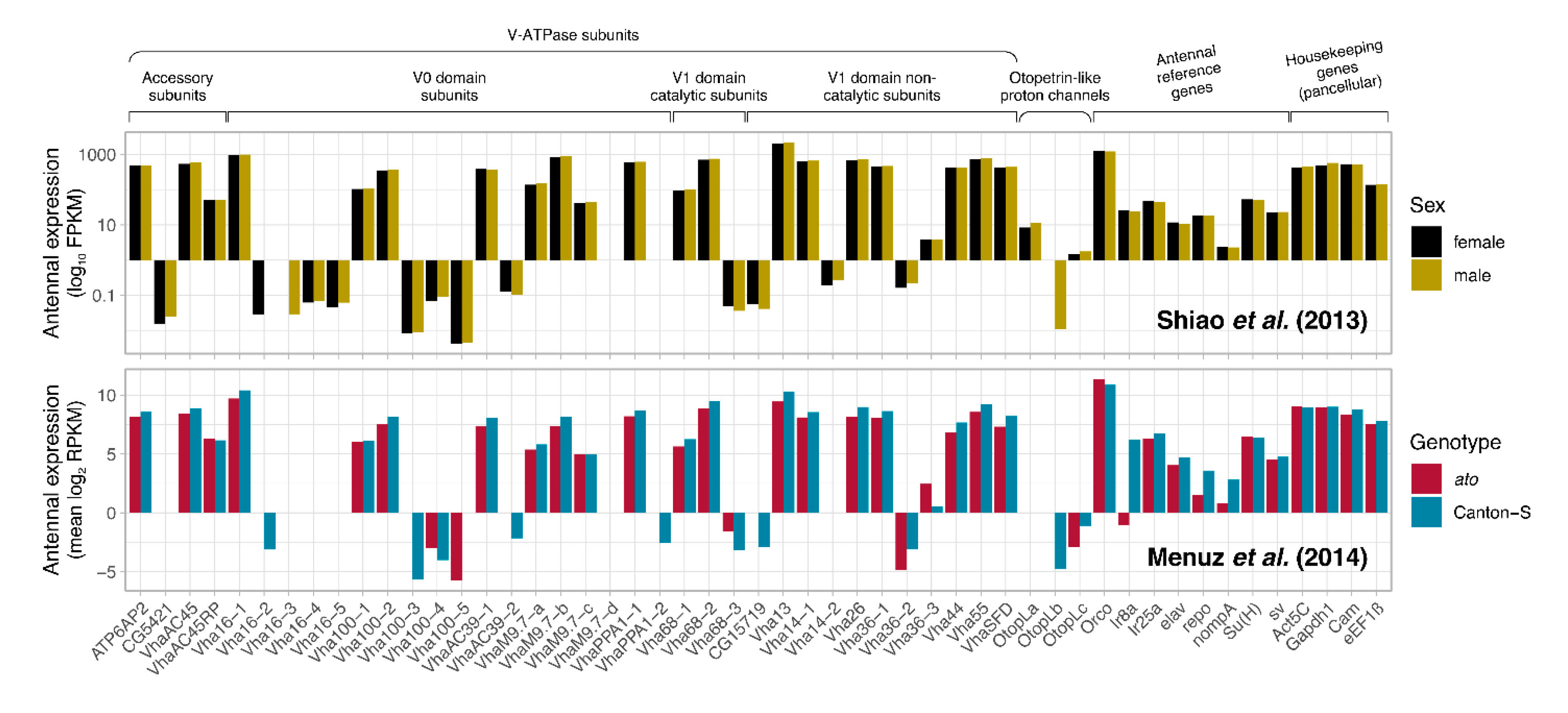

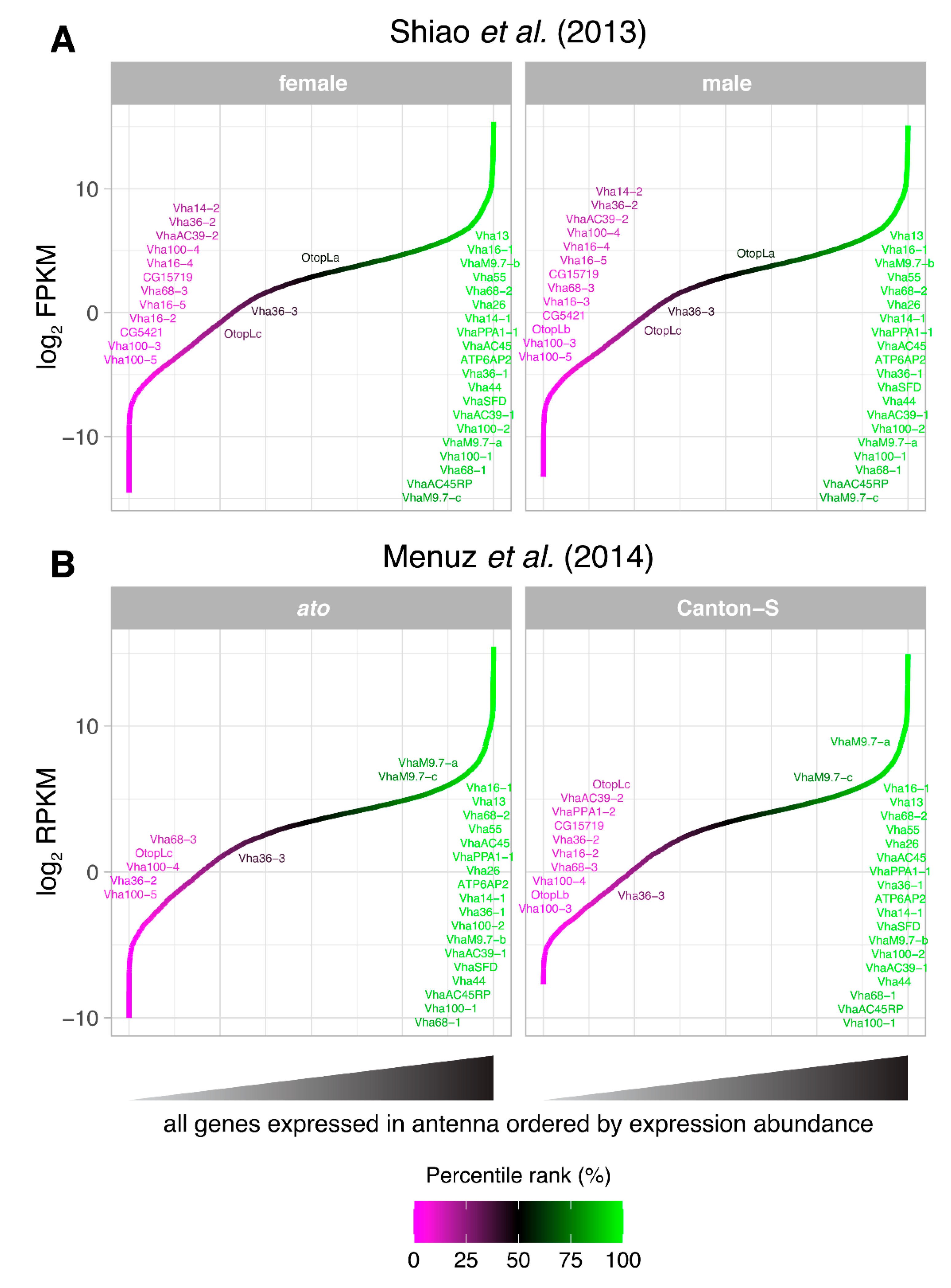

- Shiao, M.-S. , et al., Transcriptional profiling of adult Drosophila antennae by high-throughput sequencing. Zoological Studies, 2013. 52(1): p. 42.

- Menuz, K. , et al., An RNA-Seq Screen of the Drosophila Antenna Identifies a Transporter Necessary for Ammonia Detection. PLOS Genetics, 2014. 10(11): p. e1004810.

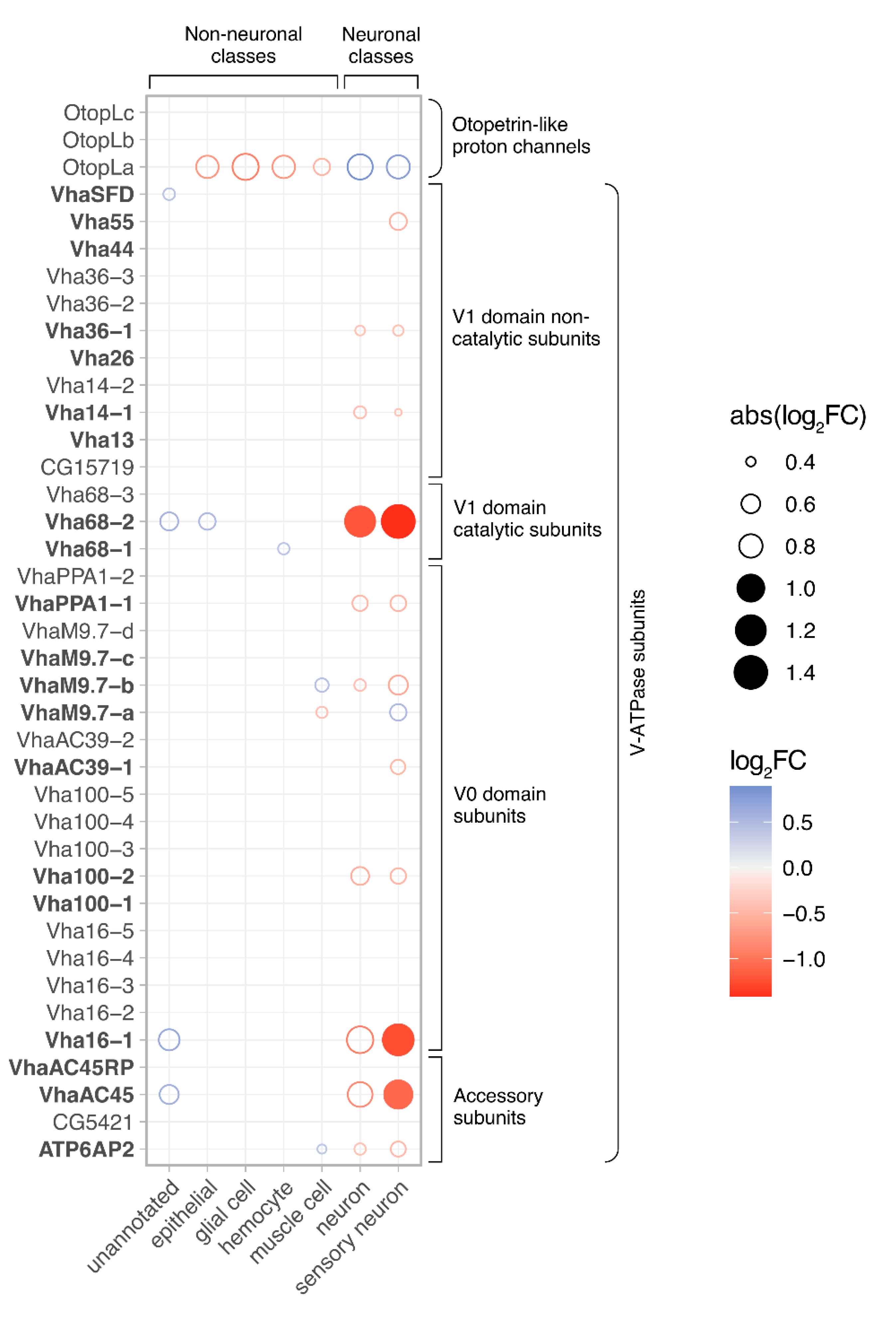

- Li, H. , et al., Fly Cell Atlas: A single-nucleus transcriptomic atlas of the adult fruit fly. Science, 2022. 375(6584): p. eabk2432.

- Chen, W. , et al., Profiling of Single-Cell Transcriptomes. Current Protocols in Mouse Biology, 2017. 7(3): p. 145-175.

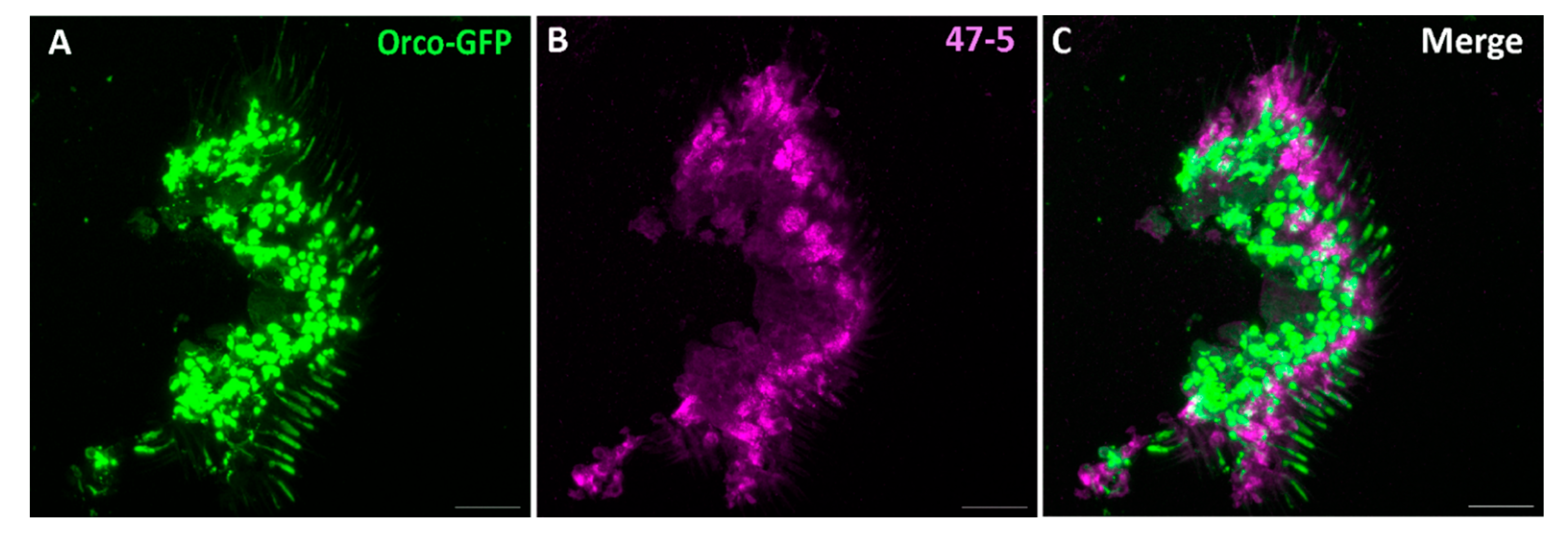

- Jain, K. , et al., A new Drosophila melanogaster fly that expresses GFP-tagged Orco. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 2023. 11.

- Chintapalli, V.R. , et al., Data-mining the FlyAtlas online resource to identify core functional motifs across transporting epithelia. BMC Genomics, 2013. 14(1): p. 518.

- Allan, A.K. , et al., Genome-wide survey of V-ATPase genes in Drosophila reveals a conserved renal phenotype for lethal alleles. Physiological Genomics, 2005. 22(2): p. 128-138.

- Mohapatra, P. and K. Menuz, Molecular Profiling of the Drosophila Antenna Reveals Conserved Genes Underlying Olfaction in Insects. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics, 2019. 9(11): p. 3753-3771.

- Ganguly, A. , et al., Requirement for an Otopetrin-like protein for acid taste in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2021. 118(51): p. e2110641118.

- Chung, Y.D. , et al., nompA Encodes a PNS-Specific, ZP Domain Protein Required to Connect Mechanosensory Dendrites to Sensory Structures. Neuron, 2001. 29(2): p. 415-428.

- Barolo, S. , et al., A Notch-Independent Activity of Suppressor of Hairless Is Required for Normal Mechanoreceptor Physiology. Cell, 2000. 103(6): p. 957-970.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).