Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common cause of hormonal dysregulation affecting 8-13% of women of reproductive age. Polycystic ovary syndrome is complex disease with hormonal, metabolic also cardiovascular components such as coronary artery disease and long-term risks such as diabetes mellitus. Despite the complex pathogenesis of PCOS associations between hormonal and metabolic disorders and gut microbiota have been emphasized. Many factors play a role in its etiology. Increased visceral adipose tissue is related with hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia and insulin resistance comorbidities as mentioned above [

1].

The presence of prolonged, low-level inflammation is observed and increased proinflammatory factors may cause systemic inflammation [

2,

3]. Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with a marked increase in inflammation biomarkers C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-18, MCP-1, it’s also associated with other inflammation-related disorders such as increased oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, supporting the presence of a chronic inflammatory state in most women with PCOS, but the relationship between infections/inflammation and PCOS has been the least studied [

4]. Studies have been carried out to identify factors such as the presence of certain pathogens associated with this low-grade chronic inflammation in PCOS. Although there are rare studies in the literature investigating the relationship between PCOS and pathogens, it is thought that there is a relationship between PCOS and some infections [

5,

7,

12]. Since Chlamydia and Helicobacter pylori infections are thought to be associated with many diseases in chronic inflammatory, it suggests that there may be a relationship between inflammation in PCOS and microorganisms causing chronic low-grade infection such as Chlamydia pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori and pathogens causing periodontal inflammation [

5]. However, it has not been clarified yet. Chlamydia and Helicobacter pylori infections are very common worldwide. Studies on these two pathogens have been of interest. In this study, Chlamydia and Helicobacter pylori infections were preferred because of their widespread prevalence in the community, their silent course and their strong stimulant for chronic inflammation.

Chlamydia trachomatis infection is particularly common and is known to be strongly associated with infertility. It is an obligate intracellular pathogen and has a slow growth cycle and tends to be chronic and silent [

6]. Case-control studies have suggested that Chlamydia trachomatis antibodies may contribute to pathogenetic processes leading to chronic inflammation, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic and hormonal disorders of PCOS [

7,

8,

9].

In particular,

Chlamydia pneumonia seropositivity has been associated with atherosclerosis and acute myocardial infarction [

10]. Similarly,

H. pylori is associated with local, gastric and chronic systemic inflammation. Coronary heart disease, stroke, aneurysm, migraine, idiopathic arrhythmia, and endocrine system disorders are among the most common non-digestive system diseases and syndromes associated with Helicobacter pylori infection [

11,

12].

Regardless of all these factors, PCOS itself causes metabolic dysfunction such as dyslipidaemia, endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, obesity, fatty liver disease, coagulation disorders, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease and is associated with polycystic ovary syndrome [

13].

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between serum Chlamydia trachomatis and Helicobacter pylori infection and inflammatory processes in patients with PCOS and healthy controls and to analyse the factors associated with PCOS.

Materials & Methods

In this comparative cross-sectional clinical study conducted at Balıkesir University Faculty of Medicine, 40 female patients between the ages of 15-35 diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome in the gynecology and obstetrics clinic and 40 healthy female controls were included.

Ethics approval was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Balıkesir University Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (number: 2017/50 date: 05/07/2017).

The diagnosis was defined according to the 2003 Rotterdam PCOS diagnostic criteria. We included women in the PCOS group who had at least two of the following criteria: (1) oligo or anovulation; (2) clinical and/or biological hyperandrogenism; (3) Polycystic morphology of the ovary on ultrasound examination (at least 12 follicles with a diameter of 2-9 mm and/or volume ≥10 mL per ovary)) [

14].

Control subjects were healthy volunteers recruited from the community with no clinical menstrual cycle disorders and no clinical evidence of hyperandrogenism. We did not include women with any of the following conditions: pregnancy or lactation, known diabetes mellitus, acute infection within the last 3 weeks. Patients with active infections in any part of the site, patients receiving anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, corticosteroid therapy, advanced age, immunosuppression, and autoimmune diseases were not included in the study. Known chronic diseases (hepatic, renal, autoimmune, neoplasia, Human Immunodeficiency Virus), very high levels of CRP or other known hyperandrogenemia conditions (late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing’s syndrome and androgen-releasing tumors).

Patients’ presenting complaints, age, comorbidities, laboratory results, body mass index (BMI) and ultrasonographic findings were recorded. The overweight limit was accepted as 25 kg/m2 and above. Blood hormone profiles (follicle simulular hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and biochemical parameters; low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), triglycerides, cholesterol, fasting blood glucose (FBS), CRP values were analyzed. Venous blood samples taken from all patients between 09:00 and 10:00 after fasting overnight were sent to the laboratory for hormonal and biochemical analysis. All samples were centrifuged at 825 g for 10 min and stored at -40 °C until analysis. Commercially available kits (Cobas Integra 800; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, German) was used in a chemistry autoanalyzer to measure glucose, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), total cholesterol, and triglycerides. In a hormone autoanalyzer, we measured fasting insulin levels with Access Kits. (Beckman Coulter; Unicel DXI 600; Access Immunoassay, Brea, CA). C-Reactive Protein (CRP) concentration was determined by laser nephrometry.

All blood samples were sent to the same laboratory. A tube of blood was taken from the PCOS and control groups and analyzed in a biochemistry tube for H. pylori IgG and Clamidydia trachomatis IgG. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent test kit was used to measure H. pylori IgG and Clamidydia trachomatis IgG (ELISA) method (NovaTec, Immundiagnostica GmbH, NovaLisa®, Germany). In the method, approximately 10µl of the participant’s serum was taken and diluted, each well was incubated at 37ºC for one hour and then washed with washing solution. After the conjugate was added, the plates were washed again after incubation at room temperature for another 30 minutes and TMB substrate was added. Incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 minutes. Finally, stop solution into all wells in the same order and at the same rate as for the TMB. 10% higher than the cut-off values and those with,10% less than cut-off are negative. Those in the, are in Grey zone and were repeated. Results were for H.pylori IgG interpreted as reactive if the absorbance value is >20NTU/ml, Non-Reactive if value is <15 NTU/ml and in Grey zone if value is between 15-20NTU/ml. For the Chlamydia trachomatis İgG, above 11 NTU (NovaTec units) were considered as positive and those below 9 NTU were taken as negative. Borderline samples with 9-11 NTU were interpreted in the gray zone.

SPSS statistical software (SPSS, version 20.0, Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analyses. Comparison between the groups was made with the Student T test. Correlation between data; those with no normal distribution (non-parametric) were evaluated with Spearman rho, and those with normal distribution (parametric) were evaluated with Pearson Correlation. p< 0.05 value was statistically accepted.

Results

Forty patients with PCOS with a mean age of 27 (range, 21 to 38) years were included in the study. The control group consisted of 40 healthy individuals with a mean age of 27.5 (range, 19 to 35) years. Among comorbid diseases, diabetes mellitus (DM) and BMI were significantly associated with PCOS (

p=0.005, p=0.000). The rate of smoking was significantly higher in the control group than in the PCOS group (

p=0.036). The distribution of descriptive features and operating parameters is listed in

Table 1.

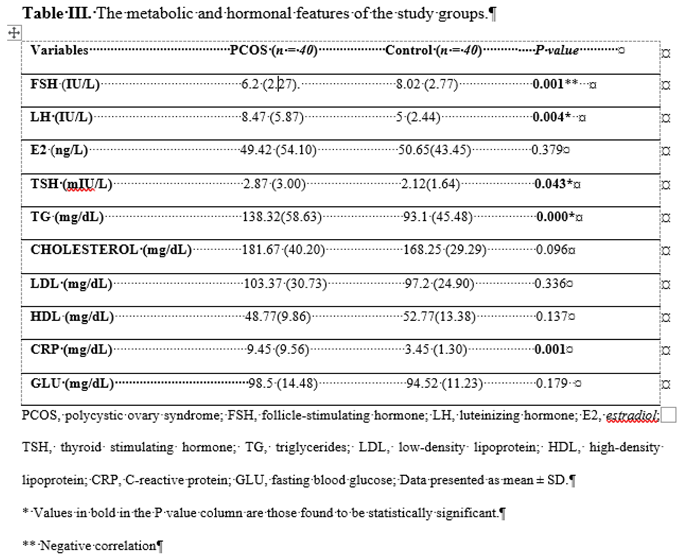

Compared with the control group; BMI, LH, HOMA-IR, CRP, TSH, TG were significantly higher in subjects with PCOS (p=004; p=001; p=001; p=043; p=000). FSH was lower in PCOS patients than in controls (p=001).

There was no significant relationship between PCOS and non-PCOS groups

in terms of the presence of H. pylori IgG (

p=0.1) and Clamidydia trachomatis IgG (

p=0.338).The metabolic and hormonal characteristics of the study groups are listed in

Table 2.

Discussion

It has been suggested that chronic systemic inflammation plays a role in the development of PCOS. PCOS, which is characterized by hyperandrogenemia and chronic oligo/anovulation, is also associated with metabolic disorders. Some researchers have argued that PCOS represents the female subtype of metabolic syndrome with a potential atherogenic risk [

15]. Increased markers such as CRP, leucocytosis, and detection of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and interleukin-18 in patients with PCOS indicate a low level of chronic inflammation [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

In the study of Kanber et al. CRP, sICAM-1 and sE-selectin levels, which are markers of chronic inflammation, were found to be significantly higher in patients with PCOS than in the control group [

21]. In our study, the mean CRP levels were 9.45 [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,35,36,37,38,39,40] in patients with PCOS and 3.45 [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] in the healthy group. It was found to be significantly higher in the PCOS group and found to be consistent as a marker of inflammation.

Insulin resistance is defined as the failure of normal biological response to endogenous and exogenous insulin. Insulin resistance has been detected in 43-76% of cases with PCOS. In these women, an increase in the frequency of Type 2 DM and 5-30% glucose intolerance have been found [

22]. In our study, DM was the most common comorbidity in the PCOS patient group. (

p=0.005) In women with PCOS, dyslipidaemia and dysfibrinogenemia may develop due to hyperandrogenism and obesity and the risk of coronary artery disease increases. Insulin resistance also contributes to dyslipidaemia. HDL/LDL ratio decreases and triglycerides increase. In studies, it has been found that lipid levels are borderline high in approximately 70% of women with PCOS [

23,

24]. Our study also supports this; BMI, HOMA-IR, TG (

p=0.000,

p=0.001,

p=0.000) were significantly higher in subjects with PCOS compared with those of the control group. The significant presence of these factors associated with elevated CRP and low-grade chronic inflammation in the PCOS group may explain inflammation even in the absence of an association with infection.

In previous studies, have been reported to be associated with myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis and

Chlamydia pneumoniae seropositivity [

5,

10]. The significant association between

C. pneumoniae seropositivity and higher BMI and metabolic syndrome has also suggested that CRP plays an active role in the development of insulin resistance. Similarly, an association between

Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and arterial stiffness and unstable angina has been reported [

25,

26].

Studies have been carried out to identify factors such as the presence of certain pathogens associated with this low-grade chronic inflammation in PCOS. It has also been hypothesised that this syndrome may be caused by infectious agents, although the exact pathogenic mechanisms are still unclear. It was anticipated that useful information would be gained from research into the infectious/inflammatory component of this chronic and multifactorial disease. Studies have suggested a relationship between the presence of low-grade chronic inflammation and

Chlamydia trachomatis or

Helicobacter pylori [

5,

7,

12]. However, there are a limited number of studies investigating the relationship with PCOS and it has not been sufficiently elucidated. In particular, although the study by Morin-Papunen et al. on the association between Chlamydia trachomatis and PCOS has been cause a sensation, no supporting study has been found and there are not many studies in the literature on this subject. In our study, 10% of 40 women with PCOS were positive for

Chlamydia trachomatis antibodies, whereas this rate was 5% in a healthy group of 40 women. No significant difference was found between both groups. (

p=0.338)

Helicobacter pylori has been shown to cause both local gastric and chronic systemic inflammation. There are studies finding a relationship between PCOS and infertility. In the study of Yavasoglu et al., while

H. pylori antibodies were positive in 40% of women with PCOS, this rate was 22% in the healthy group and

H. pylori was associated with PCOS [

11]. In another study, in contrast, no difference was found between

H. pylori Ig G seroprevalence between PCOS and non-PCOS groups (

p=0.924) [

27]. In our study, 70% of 40 women with PCOS were positive for

H. Pylori antibodies, whereas this rate was 50% in a healthy group of 40 women. No significant difference was found between both groups. (

p=0,110)

In another study, the relationship between CMV and EBV latent infection and PCOS was investigated by anti-CMV and anti-EBV IgG specific antibodies in serum samples. CMV was found to be positive in 16.7% of 60 women with PCOS and only one case (3.3%) in the control group. On the other hand, in the group with PCOS, 27 (45%) were positive for anti-EBV IgG Ab, whereas none of the 30 women (0%) in the control group tested positive. With these results, it has been suggested that these viruses may be involved in one aspect of the causal events behind PCOS [

28]. No other study has been conducted to support this.

Periodontal infections have been suggested to be related with the development of inflammation and chronic processes [

12,

29]. Low interleukin IL-10 and genetic predisposition to high TNF-α strongly stimulate the infectious response and increase the risk of tubal damage and fibrosis [

30].

Many factors contribute to chronic low-grade inflammation in PCOS pathogenesis. in PCOS pathogenesis. In our study, there was no significant difference in microbial/infectious etiology between the PCOS and non-PCOS groups, which makes it important to investigate other factors.

For example, abdominal obesity has been shown to cause metabolic and hormonal deterioration in PCOS, and visceral obesity has been shown to cause chronic low-grade inflammation [

31,

32]. Chronic inflammation and impaired endothelial function are thought to be effective in insulin resistance and asymptomatic coronary atherosclerosis has been shown to be high [

32,

33].

Adipocytes secrete proinflammatory cytokines that facilitate the chronic inflammatory response. In our study, BMI was significantly higher in the PCOS group, and the contribution of metabolic states associated with high HOMA-IR and triglyceride levels to inflammation seems to be significant.

Intestinal microbiota and gut microbiota is an endocrine organ and the relationship between it and the pathogenesis of PCOS is also important; it affects reproductive endocrinology by interacting with hormones such as androgen and insulin. It is expected that future studies will be directed towards investigating PCOS and microbiota [

34].

In the course of PCOS, inflammation is observed. The relationship between inflammation and infections is controversial and understudied. In recent years, studies have been published showing a link between inflammation in PCOS and infectious agents as in Chlamydia pneumoniae and Helicobacter pylori. However, there are studies that do not support this, it has not been clarified. Our study aimed to investigate the relationship between infection and inflammatory processes by investigating serum Chlamydia trachomatis and Helicobacter pylori antibodies in female patients with PCOS and healthy controls in the same age group. There was no significant association between PCOS and non-PCOS groups in terms of the presence of Helicobacter pylori IgG and Clamidydia trachomatis IgG. It is a mystery whether infections somehow contribute to polycystic ovary syndrome problems. This topic is open to further research.

PCOS is characterised by chronic nonspecific low-grade inflammation as described in the study by Ruan et al. [35]. Inflammation without infection is observed in the pathogenesis of PCO

Conclusion

In our study, no significant relationship was found between the groups with and without PCOS in terms of the presence of Helicobacter pylori IgG and Clamidydia trachomatis IgG. Inflammation can also occur for non-infectious reasons. Chronic inflammation contributes to the processes leading to the metabolic and hormonal disorders of PCOS. Increased visceral adipose tissue, insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance and disturbances in lipid metabolism are associated with PCOS. The role of inflammation and infections in the aetiology of multifactorial diseases is always open to investigation. More studies are needed in PCOS and similar diseases. Investigation of the relationship with microbiota may bring important results.

The limitation of our study is its cross-sectional design. Replication in a large multicentre cohort would be desirable, but experimental studies are needed to clarify the pathways underlying the effects of multiple inflammatory cytokines in PCOS. The direction towards investigating PCOS and intestinal microbiota may be informative.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. *The revised manuscript is within the knowledge of all participants and all authors have given their consent.

Funding

The study was supported by the Balikesir University Scientific Investigations Foundation (project number:2017/119).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Balıkesir University Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (2017/50 ).

Informed Consent Statement

The authors declare that they are responsible for the article’s scientific content including study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing, some of the main line, or all of the preparation and scientific review of the contents and approval of the final version of the article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- Duleba, A.J.; Dokras, A. Is PCOS an inflammatory process? Fertil Steril. 2012, 97, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witchel, S.F.; Oberfield, S.E.; Peña, A.S. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Pathophysiology, Presentation, and Treatment with Emphasis on Adolescent Girls. J Endocr Soc. 2019, 14, 1545–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azziz, R.; Carmina, E.; Chen, Z.; Dunaif, A.; Laven, J.S.; Legro, R.S.; et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016, 11, 16057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, O.̈.; Temur, M.; Küme, T.; Karas, C.̧.A.; Kelekçi, S.; Öztürk, Y.K. C-Reactive Protein Levels in Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome and Healthy Controls. TJFMPC 2017, 11, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, M.; Kiechl, S.; Willeit, J.; Wick, G.; Xu, Q. Infections, immunity, and atherosclerosis: Associations of antibodies to Chlamydia pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori, and cytomegalovirus with immune reactions to heat-shock protein 60 and carotid or femoral atherosclerosis. Circulation 2000, 22, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavonen, J. Chlamydia trachomatis infections of the female genital tract: State of the art. Ann Med. 2012, 44, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin-Papunen, L.C.; Duleba, A.J.; Bloigu, A.; Järvelin, M.R.; Saikku, P.; Pouta, A. Chlamydia antibodies and self-reported symptoms of oligo-amenorrhea and hirsutism: A new etiologic factor in polycystic ovary syndrome? Fertil Steril. 2010, 94, 1799–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morré, S.A.; Rozendaal, L.; van Valkengoed, I.G.; Boeke, A.J.; van Voorst Vader, P.C.; Schirm, J.; et al. Urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis serovars in men and women with a symptomatic or asymptomatic infection: An association with clinical manifestations? J Clin Microbiol. 2000, 38, 2292–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B.; Olesen, F.; Moller, J.K.; Ostergaard, L. Population-based strategies for outreach screening of uro- genital Chlamydia trachomatis infections: A randomized, controlled trial. J Infect Dis. 2002, 185, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikku, P.; Leinonen, M.; Mattila, K.; Ekman, M.R.; Nieminen, M.S.; Mäkelä, P.H.; et al. Serological evidence of an association of a novel Chlamydia, TWAR, with chronic coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1988, 2, 983–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavasoglu, I.; Kucuk, M.; Cildag, B.; Arslan, E.; Gok, M.; Kafkas, S. A novel association between polycystic ovary syndrome and Helicobacter pylori. Am J Med Sci. 2009, 338, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, E.; Akalin, F.A.; Guncu, G.N.; Cinar, N.; Aksoy, D.Y.; Tozum, T.F.; et al. Periodontaldisease in polycystic ovarysyndrome. Fertil Steril. 2011, 95, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inci Coskun, E.; Omma, T.; Taskaldiran, I.; Firat, S.N.; Culha, C. Metabolic role of hepassocin in polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023, 27, 5175–5183. [Google Scholar]

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2003, 81, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Karatzis, E.N. The role of inflammatory agents in endothelial function and their contribution to atherosclerosis. Hell J Cardiol 2005, 46, 232–239. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, C.C.; Lyall, H.; Petrie, J.R.; Gould, G.W.; Connell, J.M.; Sattar, N. Low grade chronic inflammation in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001, 86, 2453–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulman, N.; Levy, Y.; Leiba, R.; Shachar, S.; Linn, R.; Zinder, O.; et al. C-reactive protein levels in the polycystic ovary syndrome: A marker of cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004, 89, 2160–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesh, J.; Wheeler, J.G.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Eda, S.; Eiriksdottir, G.; Rumley, A.; et al. C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2004, 350, 1387–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orio, F., Jr.; Palomba, S.; Cascella, T.; Di Biase, S.; Manguso, F.; Tauchmanovà, L.; et al. The increase of leukocytes as a new putative marker of low-grade chronic inflammation and early cardiovascular risk in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003, 90, 2–5, Escobar-Morreale HF, Calvo RM, Villuendas G, Sancho J, San Millán JL. Association of polymorphisms in the interleukin 6 receptor complex with obesity and hyperandrogenism. Obes Res. 2003;11: 987-996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanber Açar, D.; Vural, P.; Akgül, C. Polikistik over sendromlu hastalarda kronik inflammasyon belirteçleri olan hS -CRP, sICAM-1, sVCAM-1 VE sE-Selektin düzeyleri. İst Tıp Fak Derg. 2011, 73, 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Witchel, S.F. Puberty and polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006, 25, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbott, E.; Guzick, D.; Clerici, A.; Berga, S.; Detre, K.; Weimer, K.; et al. Coronary heart disease risk factors in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995, 15, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbott, E.O.; Zborowski, J.V.; Sutton-Tyrrell, K.; McHugh-Pemu, K.P.; Guzick, D.S. Cardiovascular risk in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2001, 28, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, M.; Fukui, M.; Ishikawa, T.; Ohnishi, N.; Ishigami, N.; Yoshioka, K.; et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and arterial stiffness in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2008, 57, 1760–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicano, R.; Mazzarello, M.G.; Morelloni, S.; Ferrari, M.; Angelino, P.; Berrutti, M.; et al. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in patients with unstable angina. J Cardiovasc Surg. 2003, 44, 605–609. [Google Scholar]

- Tokmak, A.; Doğan, Z.; Sarıkaya, E.; Timur, H.; Kekilli, M. Helicobacter pylori infection and polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescent and young adult patients. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016, 42, 1768–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabassi, H.M.; Kadri, Z.H.M.; Mahmood, M.M.; AL-Kubisi, M.I. The Possible Etiological Role of CMV & EBV Latent Infections in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Iraqi patients. SRP. 2020, 11, 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tanguturi, S.C.; Nagarakanti, S. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Periodontal disease: Underlying Links- A Review. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2018, 22, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohman, H.; Tiitinen, A.; Halttunen, M.; Lehtinen, M.; Paavonen, J.; Surcel, H.M. Cytokine polymorphisms and severity of tubal damage in women with Chlamydia-associated infertility. J Infect Dis. 2009, 199, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franik, G.; Bizoń, A.; Włoch, S.; Pluta, D.; Blukacz, Ł.; Milnerowicz, H.; et al. The effect of abdominal obesity in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome on metabolic parameters. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017, 21, 4755–4761. [Google Scholar]

- Lisko, I.; Tiainen, K.; Stenholm, S.; Luukkaala, T.; Hurme, M.; Lehtimäki, T.; et al. Inflammation, adiposity, and mortality in the oldest old. Rejuvenation Res. 2012, 15, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, S.; Choudhuri, S.; Bhattacharya, B.; Bhattacharjee, R.; Roy, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; et al. Chronic inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome: A case-control study using multiple markers. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2021, 19, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremellen, K.; Pearce, K. Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota (DOGMA) a novel theory for the development of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Med Hypotheses. 2012, 79, 104–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, X.; Dai, Y. Study on chronic low-grade inflammation and influential factors of polycystic ovary syndrome. Med Princ Pract. 2009, 18, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Distribution of Descriptive Features.

Table 1.

Distribution of Descriptive Features.

| |

PCOS |

P value

|

| Positive (n=40) |

Negative (n=40) |

| Age (year) |

Min-Max (Median) |

21-38 (27) |

19-35 (27.5) |

0.919 |

| Mean±SD |

27.52±4.14 |

27.42±4.53 |

| Comorbidity (%) |

None |

23 |

38 |

|

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) |

8 |

0 |

0.005* |

| Hypertension (HT) |

1 |

0 |

|

| Thyroid disease |

4 |

0 |

|

| FMF |

1 |

0 |

|

| |

Anemia |

1 |

0 |

|

| Marital status (%) |

Married |

15 |

25 |

0.127 |

| Single |

7 |

33 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

18.5-24,9 |

9 |

40 |

|

| |

25-29.9 |

15 |

0 |

0.000* |

| |

30≤ |

16 |

0 |

|

| Smoking |

Yes |

5 |

14

26 |

0.036* |

| |

No |

35 |

|

Table 2.

H. pylori Ig G and C.Trachomatis IgG seroprevalence in PCOS and non-PCOS groups.

Table 2.

H. pylori Ig G and C.Trachomatis IgG seroprevalence in PCOS and non-PCOS groups.

| |

PCOS |

P value

|

| Positive (n=40) |

Negative (n=40) |

| H.pylori IgG |

Positive |

28 |

20 |

0,110 |

| |

Negative |

12 |

20 |

|

| C.Trachomatis IgG |

Positive |

4 |

2 |

0.338 |

| |

Negative |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).