Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

24 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

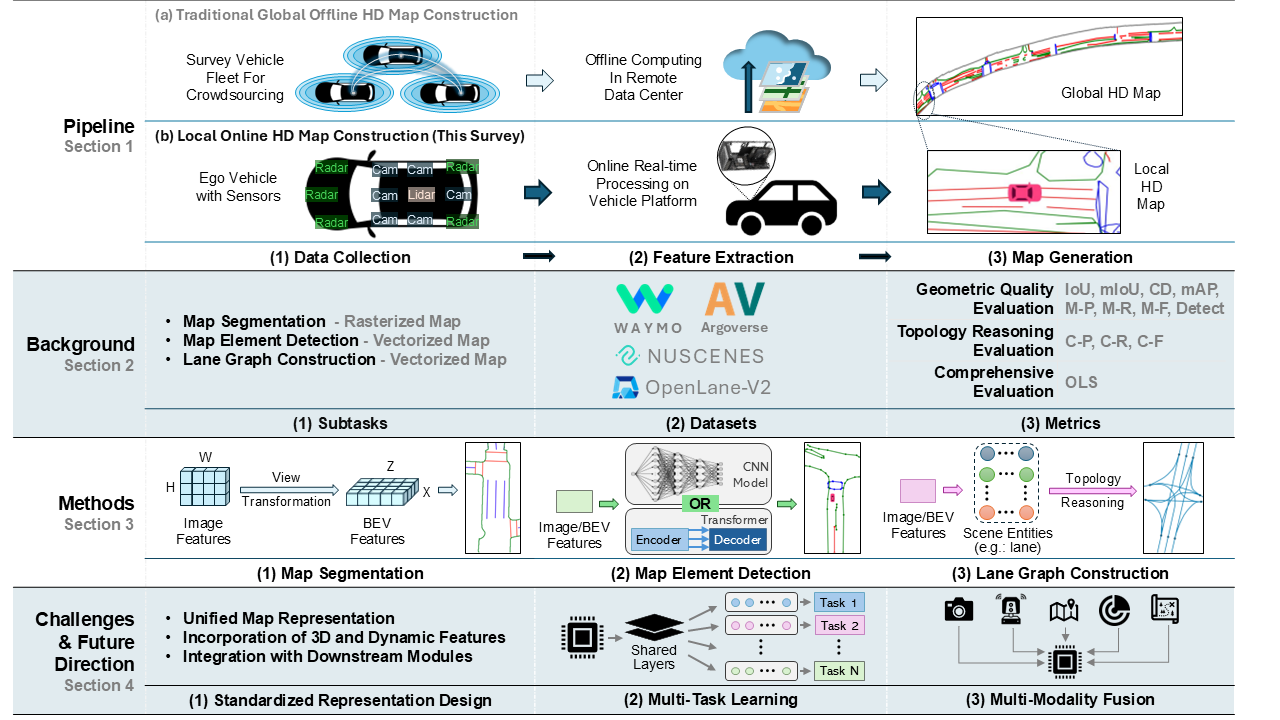

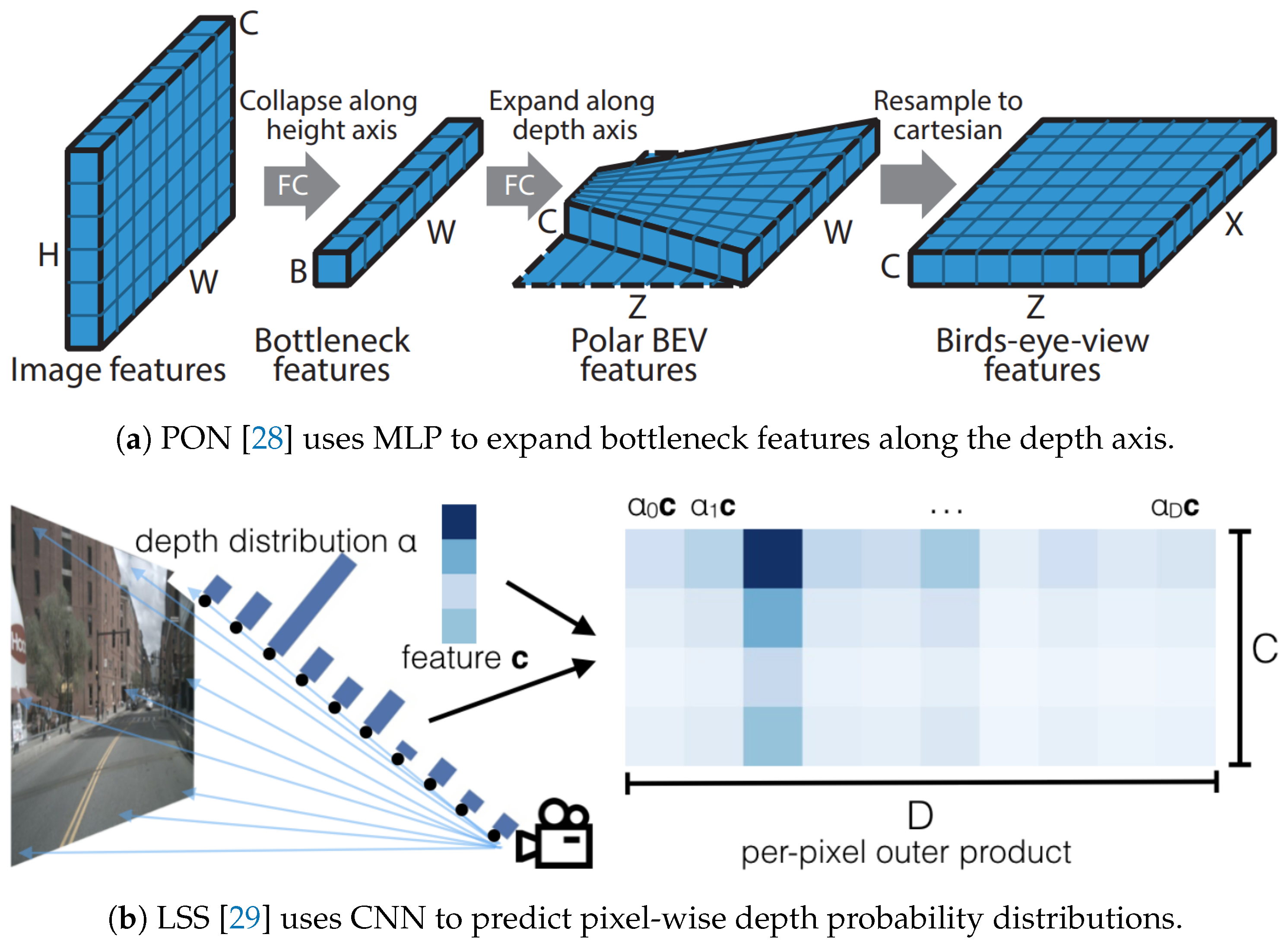

1. Introduction

1.1. Comparison to Related Surveys

1.2. Contributions

- We provide background knowledge on online HD map construction, including key aspects such as task definitions, commonly used datasets, and prevalent evaluation metrics.

- We review the latest methods for online HD mapping, categorizing them based on the formats of local HD maps they produce. This review includes a comparative analysis and a detailed discussion of the strengths and limitations of methods within each category.

- We explore the current challenges, open problems, and future trends in this cutting-edge and promising research field. We offer insights to help readers understand the existing obstacles and identify areas needing further development.

1.3. Overview

2. Background

2.1. Task Definitions

- Representation 1: Each vertex represents a point on the lane graph, defined by a vectorized sequence that encodes its coordinates and attributes. Each edge is a directed line segment connecting two vertices and is characterized by an ordered point sequence describing its geometric shape.

- Representation 2: Each vertex represents a lane, capturing its geometric shape with an ordered point sequence S. The edges are represented by an adjacency matrix I, where indicates that lane connects to lane , with the termination of lane aligned to the beginning of lane . Here, i and j are the indices of the lane vertices.

- Representation 3: Each vertex represents a lane or a traffic element, capturing its geometric shape with an ordered point sequence S. The edges are represented by two adjacency matrices: the first, , denotes the connectivity between lanes, where indicates that lane connects to lane , with the termination of lane aligned to the beginning of lane . The second adjacency matrix, , describes the correspondence between lanes and traffic elements, where signifies that lane is related to traffic element . Here, i and j are the indices of the lanes, and k is the index of the traffic elements.

2.2. Datasets

2.3. Evaluation Metrics

2.3.1. Geometric Quality Evaluation

2.3.2. Topology Reasoning Evaluation

2.3.3. Comprehensive Evaluation

3. Methods

3.1. Map Segmentation for Rasterized Maps

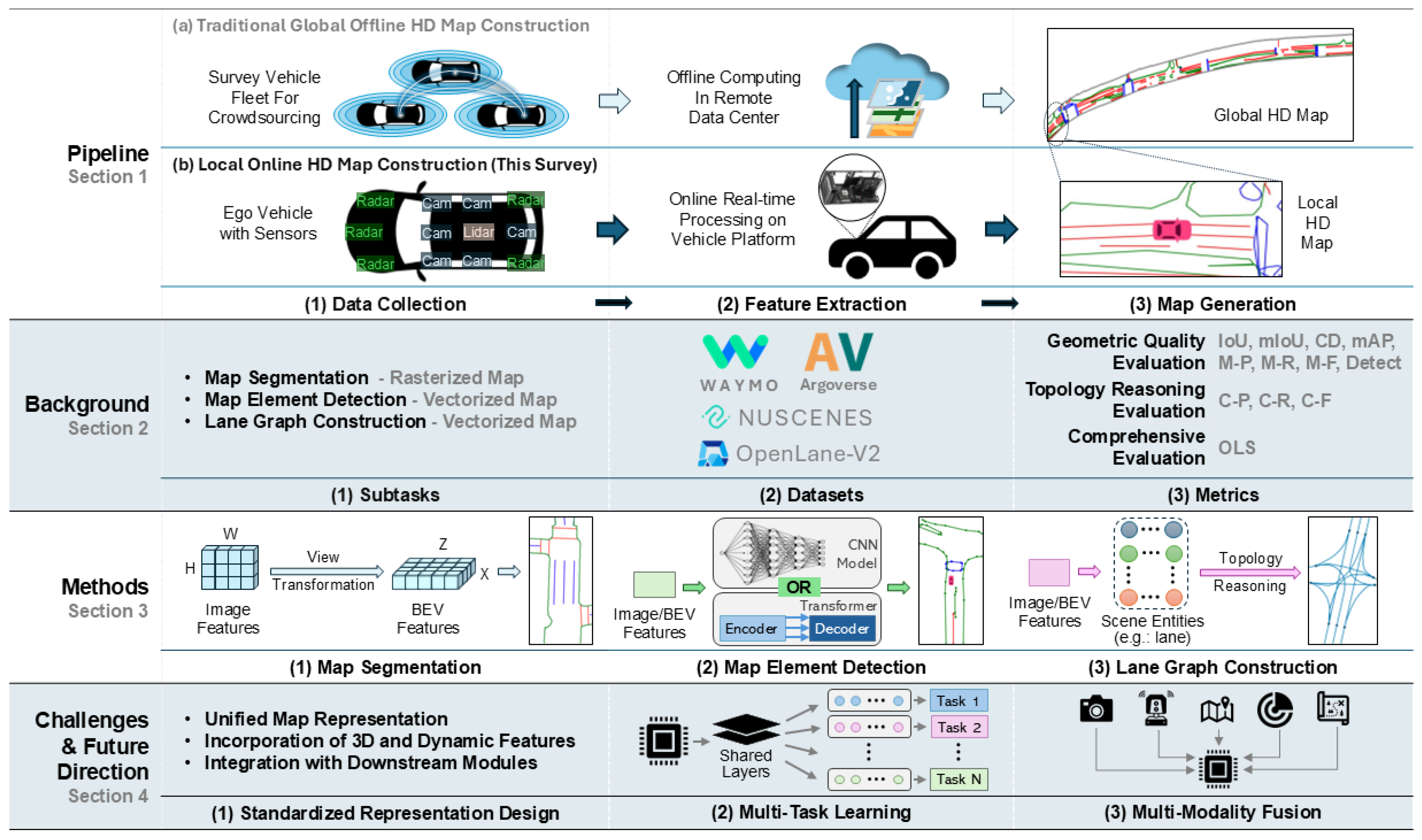

3.1.1. Projection-Based VT for Map Segmentation

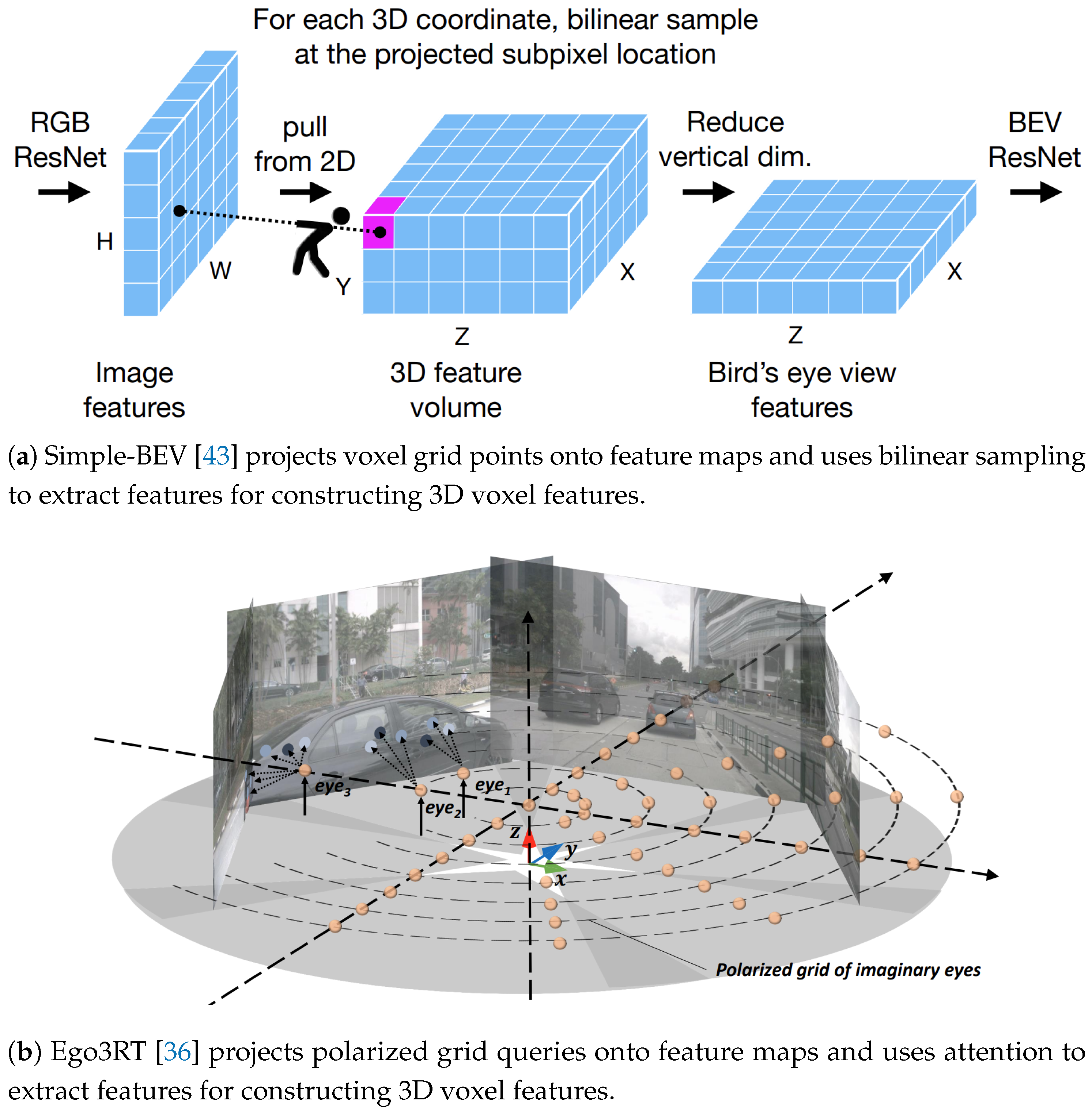

3.1.2. Lift-Based VT for Map Segmentation

3.1.3. Network-Based VT for Map Segmentation

3.1.4. Discussion on Map Segmentation Methods

3.2. Map Element Detection for Vectorized Maps

3.2.1. CNN-Based MD for Map Element Detection

3.2.2. Transformer-Based MD for Map Element Detection

3.2.3. Discussion on Map Element Detection Methods

3.3. Lane Graph Construction for Vectorized Maps

3.3.1. Single-Step-Based TR for Lane Graph Construction

3.3.2. Iteration-Based TR for Lane Graph Construction

3.3.3. Discussion on Lane Graph Construction Methods

4. Challenges and Future Trends

4.1. Standardized Representation Design

4.2. Multi-Task Learning

4.3. Multi-Modality Fusion

5. Conclusion

References

- Liu, R.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B. High definition map for automated driving: Overview and analysis. The Journal of Navigation 2020, 73, 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghazaly, G.; Frank, R.; Harvey, S.; Safko, S. High-definition maps: Comprehensive survey, challenges and future perspectives. IEEE Open Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Hossain, S.; Lang, H.; Lin, X. A review of high-definition map creation methods for autonomous driving. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 122, 106125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Singh, S. LOAM: Lidar odometry and mapping in real-time. Robotics: Science and systems. Berkeley, CA, 2014, Vol. 2, pp. 1–9.

- Shan, T.; Englot, B.; Meyers, D.; Wang, W.; Ratti, C.; Rus, D. Lio-sam: Tightly-coupled lidar inertial odometry via smoothing and mapping. 2020 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems (IROS). IEEE, 2020, pp. 5135–5142. [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Worrall, S.; Nebot, E. Geographical map registration and fusion of lidar-aerial orthoimagery in gis. 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 128–134. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Mei, G.; Zhang, J. Feature-metric registration: A fast semi-supervised approach for robust point cloud registration without correspondences. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 11366–11374. [CrossRef]

- Shan, M.; Narula, K.; Worrall, S.; Wong, Y.F.; Perez, J.S.B.; Gray, P.; Nebot, E. A Novel Probabilistic V2X Data Fusion Framework for Cooperative Perception. 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC). IEEE, 2022, pp. 2013–2020. [CrossRef]

- Berrio, J.S.; Shan, M.; Worrall, S.; Nebot, E. Camera-LIDAR integration: Probabilistic sensor fusion for semantic mapping. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 23, 7637–7652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrio, J.S.; Zhou, W.; Ward, J.; Worrall, S.; Nebot, E. Octree map based on sparse point cloud and heuristic probability distribution for labeled images. 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2018, pp. 3174–3181. [CrossRef]

- Berrio, J.S.; Worrall, S.; Shan, M.; Nebot, E. Long-term map maintenance pipeline for autonomous vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 23, 10427–10440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, Y.B.; Liniger, A.; Paudel, D.P.; Van Gool, L. Structured bird’s-eye-view traffic scene understanding from onboard images. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021, pp. 15661–15670. [CrossRef]

- Can, Y.B.; Liniger, A.; Paudel, D.P.; Van Gool, L. Topology preserving local road network estimation from single onboard camera image. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 17263–17272. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. Hdmapnet: An online hd map construction and evaluation framework. 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 4628–4634. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yuan, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. Vectormapnet: End-to-end vectorized hd map learning. International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 22352–22369.

- Tang, X.; Jiang, K.; Yang, M.; Liu, Z.; Jia, P.; Wijaya, B.; Wen, T.; Cui, L.; Yang, D. High-Definition Maps Construction Based on Visual Sensor: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, T.; Bai, X.; Yang, H.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Yang, R.; Manocha, D.; Zhu, X. Vision-centric bev perception: A survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.02797 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Sima, C.; Dai, J.; Wang, W.; Lu, L.; Wang, H.; Zeng, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Deng, H.; others. Delving into the devils of bird’s-eye-view perception: A review, evaluation and recipe. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Kretzschmar, H.; Dotiwalla, X.; Chouard, A.; Patnaik, V.; Tsui, P.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chai, Y.; Caine, B.; others. Scalability in perception for autonomous driving: Waymo open dataset. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 2446–2454. [CrossRef]

- Caesar, H.; Bankiti, V.; Lang, A.H.; Vora, S.; Liong, V.E.; Xu, Q.; Krishnan, A.; Pan, Y.; Baldan, G.; Beijbom, O. nuscenes: A multimodal dataset for autonomous driving. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 11621–11631. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.F.; Lambert, J.; Sangkloy, P.; Singh, J.; Bak, S.; Hartnett, A.; Wang, D.; Carr, P.; Lucey, S.; Ramanan, D.; others. Argoverse: 3d tracking and forecasting with rich maps. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 8748–8757. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.; Qi, W.; Agarwal, T.; Lambert, J.; Singh, J.; Khandelwal, S.; Pan, B.; Kumar, R.; Hartnett, A.; Pontes, J.K.; others. Argoverse 2: Next generation datasets for self-driving perception and forecasting. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2301.00493 2023.

- Wang, H.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Sima, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Jia, P.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S.; others. Openlane-v2: A topology reasoning benchmark for unified 3d hd mapping. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36.

- Blaschko, M.B.; Lampert, C.H. Learning to Localize Objects with Structured Output Regression. Computer Vision – ECCV 2008; Forsyth, D., Torr, P., Zisserman, A., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008; pp. 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Bian, C.; Xia, J.; Shi, S.; Yan, Z.; Song, Q.; Xing, G. VI-Map: Infrastructure-Assisted Real-Time HD Mapping for Autonomous Driving. Proceedings of the 29th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ACM MobiCom ’23. [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Cai, X.; Xu, H.; Lu, J.; Wen, F.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L. LaneGraph2Seq: Lane Topology Extraction with Language Model via Vertex-Edge Encoding and Connectivity Enhancement. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2401.17609 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.; Xie, J.; Geiger, A. Kitti-360: A novel dataset and benchmarks for urban scene understanding in 2d and 3d. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2022, 45, 3292–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roddick, T.; Cipolla, R. Predicting semantic map representations from images using pyramid occupancy networks. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2020, pp. 11138–11147. [CrossRef]

- Philion, J.; Fidler, S. Lift, splat, shoot: Encoding images from arbitrary camera rigs by implicitly unprojecting to 3d. Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XIV 16. Springer, 2020, pp. 194–210. [CrossRef]

- Reiher, L.; Lampe, B.; Eckstein, L. A sim2real deep learning approach for the transformation of images from multiple vehicle-mounted cameras to a semantically segmented image in bird’s eye view. 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Sun, J.; Leung, H.Y.T.; Andonian, A.; Zhou, B. Cross-view semantic segmentation for sensing surroundings. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2020, 5, 4867–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, Q.; Liu, W.; Yu, Y.; Ma, Y.; He, S.; Pan, J. Projecting your view attentively: Monocular road scene layout estimation via cross-view transformation. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 15536–15545. [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Mendez, O.; Russell, C.; Bowden, R. Enabling spatio-temporal aggregation in birds-eye-view vehicle estimation. 2021 ieee international conference on robotics and automation (icra). IEEE, 2021, pp. 5133–5139. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Krähenbühl, P. Cross-view transformers for real-time map-view semantic segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 13760–13769. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Xie, E.; Sima, C.; Lu, T.; Qiao, Y.; Dai, J. Bevformer: Learning bird’s-eye-view representation from multi-camera images via spatiotemporal transformers. European conference on computer vision. Springer, 2022, pp. 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L. Learning ego 3d representation as ray tracing. European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2022, pp. 129–144. [CrossRef]

- Bartoccioni, F.; Zablocki, É.; Bursuc, A.; Pérez, P.; Cord, M.; Alahari, K. Lara: Latents and rays for multi-camera bird’s-eye-view semantic segmentation. Conference on Robot Learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 1663–1672. [CrossRef]

- Gosala, N.; Valada, A. Bird’s-eye-view panoptic segmentation using monocular frontal view images. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2022, 7, 1968–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Yu, Z.; Zhou, D.; Philion, J.; Anandkumar, A.; Fidler, S.; Luo, P.; Alvarez, J.M. BEV: Multi-Camera Joint 3D Detection and Segmentation with Unified Birds-Eye View Representation. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2204.05088 2022. [Google Scholar]

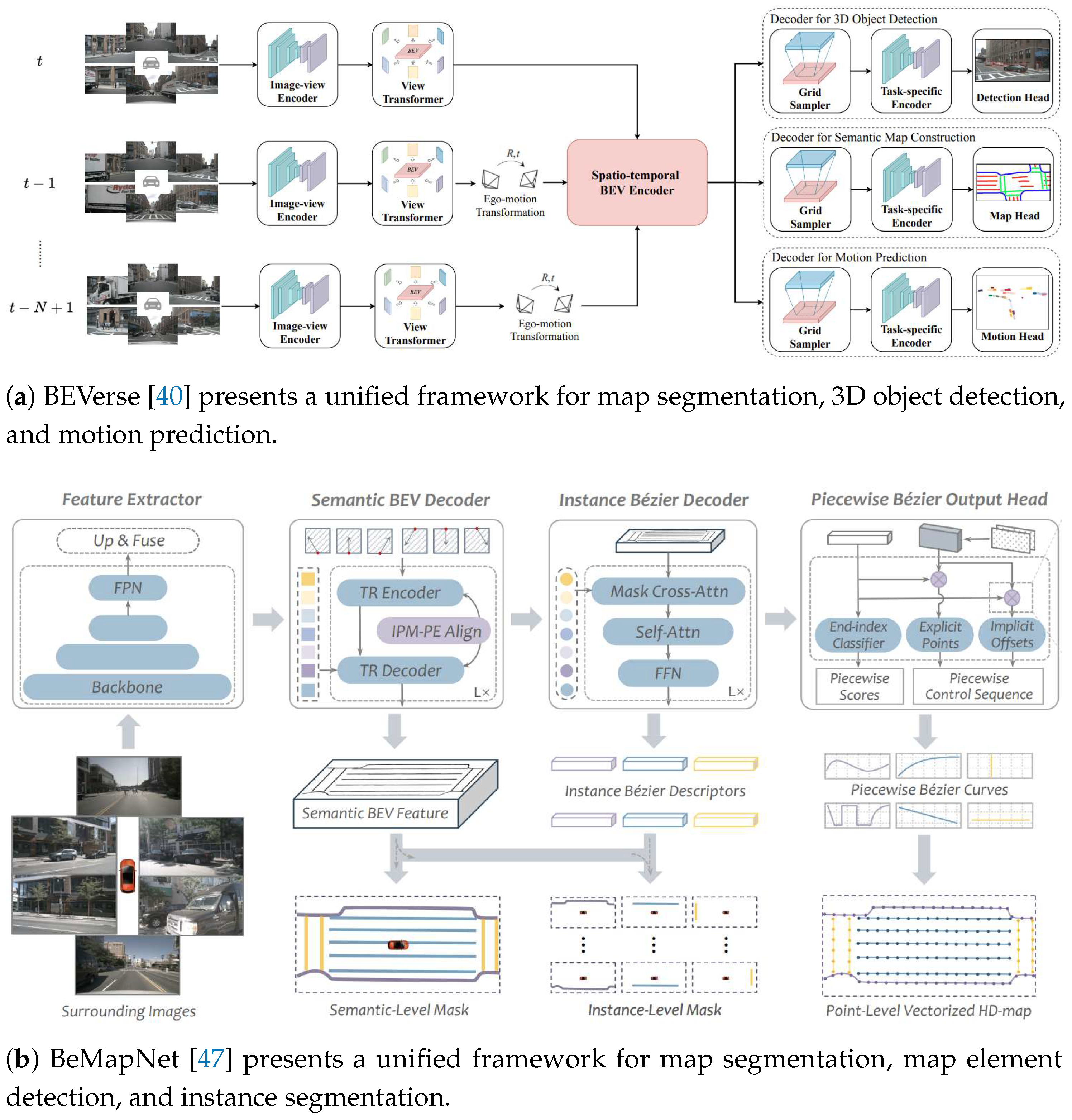

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, W.; Huang, J.; Huang, G.; Zhou, J.; Lu, J. Beverse: Unified perception and prediction in birds-eye-view for vision-centric autonomous driving. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2205.09743 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.; Chen, Z.; Fu, Z.; Liang, P.; Cheng, E. BEVSegFormer: Bird’s Eye View Semantic Segmentation From Arbitrary Camera Rigs. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 5935–5943. [CrossRef]

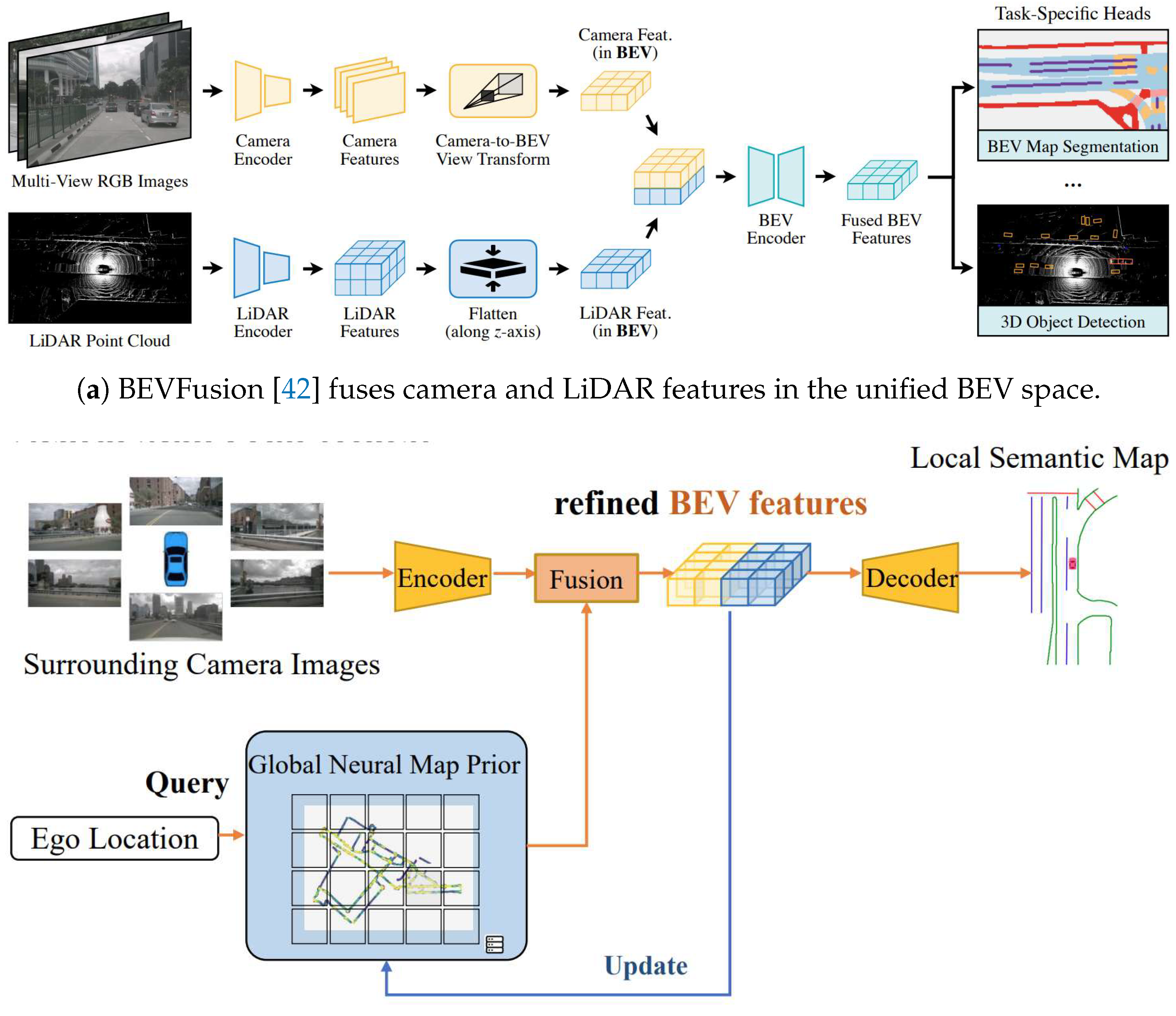

- Liu, Z.; Tang, H.; Amini, A.; Yang, X.; Mao, H.; Rus, D.L.; Han, S. Bevfusion: Multi-task multi-sensor fusion with unified bird’s-eye view representation. 2023 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2023, pp. 2774–2781. [CrossRef]

- Harley, A.W.; Fang, Z.; Li, J.; Ambrus, R.; Fragkiadaki, K. Simple-bev: What really matters for multi-sensor bev perception? 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2023, pp. 2759–2765. [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zhu, Z.; Huang, J.; Yang, T.; Huang, G.; Wang, X. HFT: Lifting Perspective Representations via Hybrid Feature Transformation for BEV Perception. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2023, pp. 7046–7053. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, J.; Jia, F.; Li, S.; Gao, A.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X. Petrv2: A unified framework for 3d perception from multi-camera images. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 3262–3272. [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Huang, C. Maptr: Structured modeling and learning for online vectorized hd map construction. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2208.14437 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, L.; Ding, W.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, C. End-to-End Vectorized HD-Map Construction With Piecewise Bezier Curve. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 13218–13228. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. Neural map prior for autonomous driving. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 17535–17544. [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Rameau, F.; Jeong, H.; Kum, D. Instagram: Instance-level graph modeling for vectorized hd map learning. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2301.04470 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.; Qiao, L.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, C. Pivotnet: Vectorized pivot learning for end-to-end hd map construction. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 3672–3682. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, S.; Sang, J. ScalableMap: Scalable Map Learning for Online Long-Range Vectorized HD Map Construction. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2310.13378 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Lin, J.; Wu, S.; Song, Y.; Luo, Z.; Xue, Y.; Lu, S.; Wang, Z. Online Map Vectorization for Autonomous Driving: A Rasterization Perspective. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2306.10502 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. Streammapnet: Streaming mapping network for vectorized online hd map construction. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2024, pp. 7356–7365. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yuan, Z. Compact HD Map Construction via Douglas-Peucker Point Transformer. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol. 38, pp. 3702–3710. [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Ai, R.; Gu, W.; Lu, H.; Kannala, J.; Chen, X. Superfusion: Multilevel lidar-camera fusion for long-range hd map generation. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2211.15656 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yu, J.; Yang, Y.; Jung, S.; Park, S.I.; Yoo, B. HIMap: HybrId Representation Learning for End-to-end Vectorized HD Map Construction. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2403.08639 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Li, W.; Yang, R.; Chen, J.; Zhu, J. MGMap: Mask-Guided Learning for Online Vectorized HD Map Construction. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2404.00876 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Wong, K.K.; Zhao, H. InsightMapper: A Closer Look at Inner-instance Information for Vectorized High-Definition Mapping. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2308.08543 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, X.; Jin, F.; Yue, X. Online vectorized hd map construction using geometry. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2312.03341 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Liu, Z.; Xu, N.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J. Enhancing vectorized map perception with historical rasterized maps. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2409.00620 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, H.; Li, D.; Yin, R.; Jung, S.; Park, S.I.; Yoo, B.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, J. MapDistill: Boosting Efficient Camera-based HD Map Construction via Camera-LiDAR Fusion Model Distillation. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2407.11682 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Jia, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, F. Stream Query Denoising for Vectorized HD Map Construction. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2401.09112 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; Tan, J.; Ma, H.; Furukawa, Y. Maptracker: Tracking with strided memory fusion for consistent vector hd mapping. European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2025, pp. 90–107. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Hu, L.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z. ADMap: Anti-disturbance framework for reconstructing online vectorized HD map. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2401.13172 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Zhao, J.; Xu, N. Leveraging enhanced queries of point sets for vectorized map construction. European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2025, pp. 461–477. [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Huang, C.; Wang, X. Maptrv2: An end-to-end framework for online vectorized hd map construction. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2308.05736 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Lin, J.; Shi, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Yao, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, K. DTCLMapper: Dual Temporal Consistent Learning for Vectorized HD Map Construction. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2405.05518 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Li, P.; Gao, H.a.; Yuan, T.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, H. P-MapNet: Far-seeing Map Constructer Enhanced by both SDMap and HDMap Priors 2023. [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Zhou, X.; Wang, M.; Yang, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, G. PrevPredMap: Exploring Temporal Modeling with Previous Predictions for Online Vectorized HD Map Construction. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2407.17378 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, L. Centerlinedet: Centerline graph detection for road lanes with vehicle-mounted sensors by transformer for hd map generation. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2023, pp. 3553–3559. [CrossRef]

- Can, Y.B.; Liniger, A.; Paudel, D.; Van Gool, L. Online Lane Graph Extraction from Onboard Video. 2023 IEEE 26th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1663–1670. [CrossRef]

- Can, Y.B.; Liniger, A.; Paudel, D.; Van Gool, L. Prior Based Online Lane Graph Extraction from Single Onboard Camera Image. 2023 IEEE 26th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1671–1678. [CrossRef]

- Can, Y.B.; Liniger, A.; Paudel, D.P.; Van Gool, L. Improving online lane graph extraction by object-lane clustering. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 8591–8601. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Peng, R.; Cai, X.; Xu, H.; Li, H.; Wen, F.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L. Translating Images to Road Network: A Non-Autoregressive Sequence-to-Sequence Approach. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 23–33. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Geng, X.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Xu, C.; others. Graph-based topology reasoning for driving scenes. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2304.05277 2023.

- Li, T.; Jia, P.; Wang, B.; Chen, L.; Jiang, K.; Yan, J.; Li, H. LaneSegNet: Map Learning with Lane Segment Perception for Autonomous Driving. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2312.16108 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Chang, J.; Jia, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T.; Shen, J. TopoMLP: An Simple yet Strong Pipeline for Driving Topology Reasoning. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2310.06753 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, K.Z.; Weng, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Li, J.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Wang, Y.; Pavone, M. Augmenting lane perception and topology understanding with standard definition navigation maps. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 4029–4035. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Leng, J.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, C. Lanemapnet: Lane network recognization and hd map construction using curve region aware temporal bird’s-eye-view perception. 2024 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV). IEEE, 2024, pp. 2168–2175. [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Chen, S.; Jiang, B.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Huang, C.; Wang, X. Lane graph as path: Continuity-preserving path-wise modeling for online lane graph construction. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2303.08815 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Yu, K.; Li, Z. Continuity Preserving Online CenterLine Graph Learning. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2407.11337 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Liao, W.; Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Dai, F.; Zhang, Y.; others. TopoLogic: An Interpretable Pipeline for Lane Topology Reasoning on Driving Scenes. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2405.14747 2024.

- Kalfaoglu, M.; Ozturk, H.I.; Kilinc, O.; Temizel, A. TopoMaskV2: Enhanced Instance-Mask-Based Formulation for the Road Topology Problem. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2409.11325 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Liang, S.; Wen, Y.; Lu, W.; Wan, G. RoadPainter: Points Are Ideal Navigators for Topology transformER. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2407.15349 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, J.; Shi, S.; Wang, X.; Li, H. 3D object detection for autonomous driving: A comprehensive survey. International Journal of Computer Vision 2023, 131, 1909–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Li, S.; Liu, P. A review of lane detection methods based on deep learning. Pattern Recognition 2021, 111, 107623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallot, H.A.; Bülthoff, H.H.; Little, J.; Bohrer, S. Inverse perspective mapping simplifies optical flow computation and obstacle detection. Biological cybernetics 1991, 64, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.; Santos, V.; Sappa, A.D. Multimodal inverse perspective mapping. Information Fusion 2015, 24, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertozz, M.; Broggi, A.; Fascioli, A. Stereo inverse perspective mapping: theory and applications. Image and vision computing 1998, 16, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Yang, M.; Li, H.; Li, T.; Hu, B.; Wang, C. Restricted deformable convolution-based road scene semantic segmentation using surround view cameras. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2019, 21, 4350–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sämann, T.; Amende, K.; Milz, S.; Witt, C.; Simon, M.; Petzold, J. Efficient semantic segmentation for visual bird’s-eye view interpretation. Intelligent Autonomous Systems 15: Proceedings of the 15th International Conference IAS-15. Springer, 2019, pp. 679–688. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable detr: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv, 2020; arXiv:2010.04159 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tesla. Tesla AI Day 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j0z4FweCy4M, 2021. [Online].

- Lu, C.; van de Molengraft, M.J.G.; Dubbelman, G. Monocular semantic occupancy grid mapping with convolutional variational encoder–decoder networks. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2019, 4, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddick, T.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. Orthographic feature transform for monocular 3d object detection. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:1811.08188 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015, pp. 3431–3440.

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. European conference on computer vision. Springer, 2020, pp. 213–229. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2019, pp. 6105–6114.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778. [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.H.; Vora, S.; Caesar, H.; Zhou, L.; Yang, J.; Beijbom, O. Pointpillars: Fast encoders for object detection from point clouds. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 12697–12705. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Mao, Y.; Li, B. Second: Sparsely embedded convolutional detection. Sensors 2018, 18, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J. Petr: Position embedding transformation for multi-view 3d object detection. European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2022, pp. 531–548. [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Song, G.; Gilitschenski, I.; Pavone, M.; Ivanovic, B. Producing and Leveraging Online Map Uncertainty in Trajectory Prediction. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2403.16439 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana, R. Multitask learning. Machine learning 1997, 28, 41–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrio, J.S.; Zhou, W.; Ward, J.; Worrall, S.; Nebot, E. Octree map based on sparse point cloud and heuristic probability distribution for labeled images. 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2018, pp. 3174–3181. [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Year | Region | Sensor Data | Map Annotation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Scenes | # Images | # Scans | # Cities | # Layers | Resolution | 3D | |||

| Waymo [19] | 2019 | NA | 1,150 | 12M | 230k | 6 | 7 | – | 55 |

| NuScenes [20] | 2019 | NA/AS | 1000 | 1.4M | 390k | 2 | 11 | 10px/m | 55 |

| Argoverse 1 [21] | 2019 | NA | 113 | 490k | 22k | 2 | 3 | – | |

| Argoverse 2 [22] | 2023 | NA | 1000 | 2.7M | 150k | 6 | 4 | 100px/m | |

| OpenLane-V2 [23] | 2023 | NA/AS | 2000 | 466K | – | 8 | 3 | – | |

| Method | Venue | Modality | Task | Dataset | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PON [28] | CVPR 2020 | SC | MapSeg | nuS/AV | MLP for Depth Axis Expansion |

| LSS [29] | ECCV 2020 | MC | MapSeg | nuS | CNN for Pixel-Wise Depth Prediction |

| Cam2BEV [30] | ITSC 2020 | MC | MapSeg | Synthetic | IPM for VT on 2D Feature Maps |

| VPN [31] | RA-L 2020 | MC | MapSeg | Synthetic | MLP to Learn Projection for VT |

| PYVA [32] | CVPR 2021 | SC | MapSeg | AV | Cycled View Projection for VT |

| STA-ST [33] | ICRA 2021 | SC | MapSeg | nuS | Temporal Fusion after VT |

| CVT [34] | CVPR 2022 | MC | MapSeg | nuS | Camera-aware Embedding to Enhance VT |

| BEVFormer [35] | ECCV 2022 | MC | MapSeg | nuS | Transformer and Projection for VT |

| Ego3RT [36] | ECCV 2022 | MC | MapSeg | nuS | Ego 3D Representation to Enhance VT |

| LaRa [37] | CoRL 2022 | MC | MapSeg | nuS | Ray Embedding to Enhance VT |

| PanopticSeg [38] | RA-L 2022 | SC | MapSeg | nuS/K360 | Hybrid VT with IPM and Depth Expansion |

| MBEV [39] | arXiv 2022 | MC | MapSeg | nuS | 3D Voxel Grid Projected onto 2D Features |

| BEVerse [40] | arXiv 2022 | MC | MapSeg | nuS | Spatio-temporal Fusion after VT |

| BEVSegFormer [41] | WACV 2023 | MC | MapSeg | nuS | Transformer to Learn Projection for VT |

| BEVFusion [42] | ICRA 2023 | MC/L | MapSeg | nuS | Camera-Lidar Fusion on BEV after VT |

| Simple-BEV [43] | ICRA 2023 | MC/L/R | MapSeg | nuS | Bilinear Sampling for Voxel Quality |

| HFT [44] | ICRA 2023 | SC | MapSeg | nuS/AV | Mutual Learning to Enhance Hybrid VT |

| PETRv2 [45] | ICCV 2023 | MC | MapSeg | nuS | 3D Position Embedding to Enhance VT |

| HDMapNet [14] | ICRA 2022 | MC/L | MapEle | nuS | FCN with Post-processing for MD |

| VectorMapNet [15] | ICML 2023 | MC/L | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Transformer for Vectorized MD |

| MapTR [46] | ICLR 2023 | MC | MapEle | nuS | Single-stage Transformer for Parallel MD |

| BeMapNet [47] | CVPR 2023 | MC | MapEle | nuS | Piecewise Bezier Curve for MD |

| NMP [48] | CVPR 2023 | MC | MapEle | nuS | Global Neural Map Prior for MD |

| InstaGraM [49] | CVPRW 2023 | MC | MapEle | nuS | CNNs and GNN for Graph-based MD |

| PivotNet [50] | ICCV 2023 | MC | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Pivot-based Representation for MD |

| ScalableMap [51] | CoRL 2023 | MC | MapEle | nuS | Hierarchical Sparse Map Representation |

| MapVR [52] | NeurIPS 2023 | MC/L | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Rasterization for Geometric Supervision |

| StreamMapNet [53] | WACV 2024 | MC | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Streaming Temporal Fusion for MD |

| DPFormer [54] | AAAI 2024 | MC | MapEle | nuS | Douglas-Peucker Point Representation |

| SuperFusion [55] | ICRA 2024 | MC/L | MapEle | nuS | Multi-level LiDAR-camera Fusion for MD |

| HIMap [56] | CVPR 2024 | MC | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Integrated HIQuery for MD |

| MGMap [57] | CVPR 2024 | MC/L | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Mask-Guided Learning for MD |

| InsMapper [58] | ECCV 2024 | MC/L | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Inner-instance Information for MD |

| GeMap [59] | ECCV 2024 | MC | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Geometric Invariant Representation |

| HRMapNet [60] | ECCV 2024 | MC | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Global Historical Rasterized Map for MD |

| MapDistill [61] | ECCV 2024 | MC | MapEle | nuS | Cross-modal Knowledge Distillation |

| SQD-MapNet [62] | ECCV 2024 | MC | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Stream Query Denoising for Consistency |

| MapTracker [63] | ECCV 2024 | MC | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Strided Memory Fusion for MD |

| ADMap [64] | ECCV 2024 | MC/L | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Anti-disturbance MD Framework |

| MapQR [65] | ECCV 2024 | MC | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Scatter-and-Gather Query for MD |

| MapTRv2 [66] | IJCV 2024 | MC/L | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Advanced Baseline Method for MD |

| DTCLMapper [67] | T-ITS 2024 | MC | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Dual-stream Temporal Consistency Learning |

| P-MapNet [68] | RA-L 2024 | MC/L | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | SD and HD Map Priors for MD |

| PrevPredMap [69] | WACV 2025 | MC | MapEle | nuS/AV2 | Temporal Fusion with Previous Predictions |

| STSU [12] | ICCV 2021 | SC | LaneGra | nuS | MLP to Infer Lane Connectivity |

| TPLR [13] | CVPR 2022 | SC | LaneGra | nuS/AV | Minimal Cycles for Lane Graph Topology |

| CenterLineDet [70] | ICRA 2023 | MC | LaneGra | nuS | Transformer for Iterative TR |

| VideoLane [71] | ITSC 2023 | SC | LaneGra | nuS/AV | Temporal Aggregation to Enhance TR |

| LaneWAE [72] | ITSC 2023 | SC | LaneGra | nuS/AV | Dataset Prior Distribution to Enhance TR |

| ObjectLane [73] | ICCV 2023 | SC | LaneGra | nuS/AV | Object-Lane Clustering to Enhance TR |

| RoadNetTransformer [74] | ICCV 2023 | MC | LaneGra | nuS | RoadNet Sequence Representation for TR |

| TopoNet [75] | arXiv 2023 | MC | LaneGra | OL2 | GNN to Refine Lane Graph Topology |

| LaneGraph2Seq [26] | AAAI 2024 | MC | LaneGra | nuS/AV2 | Graph Sequence Representation for TR |

| LaneSegNet [76] | ICLR 2024 | MC | LaneGra | OL2 | Lane Segment Representation for TR |

| TopoMLP [77] | ICLR 2024 | MC | LaneGra | OL2 | Robust Detectors to Enhance TR |

| SMERF [78] | ICRA 2024 | MC | LaneGra | OL2 | SD Maps to Enhance TR |

| LaneMapNet [79] | IV 2024 | MC | LaneGra | nuS | Curve Region-aware Attention |

| LaneGAP [80] | ECCV 2024 | MC | LaneGra | nuS/AV2/OL2 | Post-processing to Restore Lane Topology |

| CGNet [81] | ECCV 2024 | MC | LaneGra | nuS/AV2 | GNN and GRU to Optimize Lane Graph |

| TopoLogic [82] | NeurIPS 2024 | MC | LaneGra | OL2 | Lane Geometry and Query Similarity for TR |

| TopoMaskV2 [83] | arXiv 2024 | MC | LaneGra | OL2 | Mask-based Formulation to Enhance TR |

| RoadPainter [84] | arXiv 2024 | MC | LaneGra | OL2 | Points-mask Optimization |

| Method | Modality | VT Type | Drivable | Ped. Cross. | Walkway | Stop Line | Carpark | Divider | mIoU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VED* [94] | SC | Network | 54.7 | 12.0 | 20.7 | – | 13.5 | – | 25.2 |

| VPN* [31] | SC | Network | 58.0 | 27.3 | 29.4 | – | 12.3 | – | 31.8 |

| PON* [28] | SC | Lift | 60.4 | 28.0 | 31.0 | – | 18.4 | – | 34.5 |

| STA-ST* [33] | SC | Lift | 71.1 | 31.5 | 32.0 | – | 28.0 | – | 40.7 |

| CVT† [34] | MC | Network | 74.3 | 36.8 | 39.9 | 25.8 | 35.0 | 29.4 | 40.2 |

| OFT† [95] | MC | Projection | 74.0 | 35.3 | 45.9 | 27.5 | 35.9 | 33.9 | 42.1 |

| LSS† [29] | MC | Lift | 75.4 | 38.8 | 46.3 | 30.3 | 39.1 | 36.5 | 44.4 |

| MBEV† [39] | MC | Projection | 77.2 | – | – | – | – | 40.5 | – |

| BEVFusion† [42] | MC | Lift | 81.7 | 54.8 | 58.4 | 47.4 | 50.7 | 46.4 | 56.6 |

| BEVFusion† [42] | MC & L | Lift | 85.5 | 60.5 | 67.6 | 52.0 | 57.0 | 53.7 | 62.7 |

| Method | Backbone | Epochs | Modality | MD Type | AP | AP | AP | mAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDMapNet† [14] | EB0 | 30 | MC | CNN | 14.4 | 21.7 | 33.0 | 23.0 |

| InstaGraM* [49] | EB0 | 30 | MC | CNN | 40.8 | 30.0 | 39.2 | 36.7 |

| InsMapper* [58] | R50 | 24 | MC | Transformer | 44.4 | 53.4 | 52.8 | 48.3 |

| MapTR* [46] | R50 | 24 | MC | Transformer | 46.3 | 51.5 | 53.1 | 50.3 |

| MapVR* [52] | R50 | 24 | MC | Transformer | 47.7 | 54.4 | 51.4 | 51.2 |

| PivotNet* [50] | R50 | 30 | MC | Transformer | 53.8 | 55.8 | 59.6 | 57.4 |

| BeMapNet* [47] | R50 | 30 | MC | Transformer | 57.7 | 62.3 | 59.4 | 59.8 |

| MapTRv2* [66] | R50 | 24 | MC | Transformer | 59.8 | 62.4 | 62.4 | 61.5 |

| ADMap* [64] | R50 | 24 | MC | Transformer | 63.5 | 61.9 | 63.3 | 62.9 |

| SQD-MapNet* [62] | R50 | 24 | MC | Transformer | 63.0 | 62.5 | 63.3 | 63.9 |

| MGMap* [57] | R50 | 30 | MC | Transformer | 61.8 | 65.0 | 67.5 | 64.8 |

| MapQR* [65] | R50 | 30 | MC | Transformer | 63.4 | 68.0 | 67.7 | 66.4 |

| HIMap* [56] | R50 | 30 | MC | Transformer | 62.6 | 68.4 | 69.1 | 66.7 |

| HDMapNet† [14] | EB0 & PP | 30 | MC & L | CNN | 16.3 | 29.6 | 46.7 | 31.0 |

| InsMapper* [58] | R50 & Sec | 24 | MC & L | Transformer | 56.0 | 63.4 | 71.6 | 61.0 |

| MapVR* [52] | R50 & Sec | 24 | MC & L | Transformer | 60.4 | 62.7 | 67.2 | 63.5 |

| MapTRv2* [66] | R50 & Sec | 24 | MC & L | Transformer | 65.6 | 66.5 | 74.8 | 69.0 |

| ADMap* [64] | R50 & Sec | 24 | MC & L | Transformer | 69.0 | 68.0 | 75.2 | 70.8 |

| MGMap* [57] | R50 & Sec | 24 | MC & L | Transformer | 67.7 | 71.1 | 76.2 | 71.7 |

| Method | TR Type | M-Prec | M-Recall | M-F-score | Detect | C-Prec | C-Recall | C-F-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STSU* [12] | Single-step | 60.7 | 54.7 | 57.5 | 60.6 | 60.5 | 52.2 | 56.0 |

| TPLR* [13] | Single-step | – | – | 58.2 | 60.2 | – | – | 55.3 |

| ObjectLane* [73] | Single-step | – | – | 64.2 | 70.6 | – | – | 57.2 |

| VideoLane* [71] | Single-step | – | – | 59.0 | 60.3 | – | – | 61.7 |

| LaneWAE* [72] | Single-step | – | – | 57.0 | 61.2 | – | – | 62.9 |

| LaneMapNet* [79] | Single-step | 71.5 | 64.8 | 67.9 | – | 63.2 | 62.9 | 63.0 |

| LaneGraph2Seq* [26] | Iteration | 64.6 | 63.7 | 64.1 | 64.5 | 69.4 | 58.0 | 63.2 |

| Data | Method | TR Type | SD Map | DET | DET | TOP | TOP | OLS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| subset_A | STSU† [12] | Single-step | ✗ | 12.7 | 43.0 | 0.5 | 15.1 | 25.4 |

| TopoNet* [75] | Iteration | ✗ | 28.5 | 48.1 | 4.1 | 20.8 | 35.6 | |

| TopoMLP* [77] | Single-step | ✗ | 28.3 | 50.0 | 7.2 | 22.8 | 38.2 | |

| RoadPainter* [84] | Single-step | ✗ | 30.7 | 47.7 | 7.9 | 24.3 | 38.9 | |

| TopoLogic* [82] | Iteration | ✗ | 29.9 | 47.2 | 18.6 | 21.5 | 41.6 | |

| TopoMaskV2* [83] | Iteration | ✗ | 34.5 | 53.8 | 10.8 | 20.7 | 41.7 | |

| SMERF* [78] (TopoNet) | Iteration | 33.4 | 48.6 | 7.5 | 23.4 | 39.4 | ||

| RoadPainter* [84] | Single-step | 36.9 | 47.1 | 12.7 | 25.8 | 42.6 | ||

| TopoLogic* [82] | Iteration | 34.4 | 48.3 | 23.4 | 24.4 | 45.1 | ||

| subset_B | STSU† [12] | Single-step | ✗ | 8.2 | 43.9 | 0.0 | 9.4 | 21.2 |

| TopoNet* [75] | Iteration | ✗ | 24.3 | 55.0 | 2.5 | 14.2 | 33.2 | |

| TopoMLP* [77] | Single-step | ✗ | 26.6 | 58.3 | 7.6 | 17.8 | 38.7 | |

| RoadPainter* [84] | Single-step | ✗ | 28.7 | 54.8 | 8.5 | 17.2 | 38.5 | |

| TopoLogic* [82] | Iteration | ✗ | 25.9 | 54.7 | 15.1 | 15.1 | 39.6 | |

| TopoMaskV2* [83] | Iteration | ✗ | 41.6 | 61.1 | 12.4 | 14.2 | 43.9 |

| Method | Task Head | Map Segmentation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MapSeg | ObjDet | MotPre | Drivable | Lane | Ped. Cross. | Walkway | Carpark | Divider | Boundary | mIoU | |

| MBEV* [39] | ✗ | ✗ | 77.2 | 40.5 | – | – | – | – | – | 58.9 | |

| MBEV* [39] | ✗ | 75.9 | 38.0 | – | – | – | – | – | 57.0 | ||

| BEVFormer* [35] | ✗ | ✗ | 80.1 | 25.7 | – | – | – | – | – | 52.9 | |

| BEVFormer* [35] | ✗ | 77.5 | 23.9 | – | – | – | – | – | 50.7 | ||

| PETRv2† [45] | ✗ | ✗ | 80.5 | 47.4 | – | – | – | – | – | 64.0 | |

| PETRv2† [45] | ✗ | 79.1 | 44.3 | – | – | – | – | – | 61.7 | ||

| Ego3RT* [36] | ✗ | ✗ | 74.6 | – | 33.0 | 42.6 | 44.1 | 36.6 | – | 46.2 | |

| Ego3RT* [36] | ✗ | 79.6 | – | 48.3 | 52.0 | 50.3 | 47.5 | – | 55.5 | ||

| BEVerse* [40] | ✗ | ✗ | – | – | 44.9 | – | – | 56.1 | 58.7 | 53.2 | |

| BEVerse* [40] | – | – | 39.0 | – | – | 53.2 | 53.9 | 48.7 | |||

| Method | Task Head | Map Element Detection | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MapEle | DepEst | MapSeg | SemSeg | AP | AP | AP | mAP | |

| MapTRv2* [66] | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 44.9 | 51.9 | 53.5 | 50.1 | |

| MapTRv2* [66] | ✗ | ✗ | 49.6 | 56.6 | 59.4 | 55.2 | ||

| MapTRv2* [66] | ✗ | 52.1 | 57.6 | 59.9 | 56.5 | |||

| MapTRv2* [66] | 53.2 | 58.1 | 60.0 | 57.1 | ||||

| Method | Prior Map | Map Element Detection | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD Map | NMP | HRMap | AP | AP | AP | mAP | |

| HDMapNet‡ [14] | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 10.3 | 27.7 | 45.2 | 27.7 |

| HDMapNet‡ [14] | ✗ | ✗ | 11.3 | 32.1 | 48.7 | 30.7 | |

| VectorMapNet* [15] | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 36.1 | 47.3 | 39.3 | 40.9 |

| VectorMapNet* [15] | ✗ | ✗ | 42.9 | 49.6 | 41.9 | 44.8 | |

| StreamMapNet† [53] | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 60.4 | 61.9 | 58.9 | 60.4 |

| StreamMapNet† [53] | ✗ | ✗ | 63.8 | 69.5 | 65.5 | 66.3 | |

| MapTRv2† [66] | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 59.8 | 62.4 | 62.4 | 61.5 |

| MapTRv2† [66] | ✗ | ✗ | 65.8 | 67.4 | 68.5 | 67.2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).