1. Introduction

Interoception refers to the processes of perception, integration, and regulation of internal bodily signals [

1]. A common approach to testing an interoceptive process is to assess cardiac interoception (or cardioception). Cardiac interoceptive accuracy (IA) can be probed in behavioral tests, which are various modifications of heartbeat counting/detection tasks. However, these tests have certain limitations [

2], therefore a neurophysiological measure of interoceptive processing, heartbeat-evoked potentials (HEP), is of particular interest [

3]. Interoception is gaining increasing attention in various fields of research, as its dysfunction may be involved in the expression of various disorders [

4]. In addition, the role of interoception in symptom experience has recently been discussed. Studies summarized in the systematic review by Locatelli et al. [

5] showed conflicting results regarding the relationship between IA and symptom severity. However, data on interoception and cardiac symptom severity are limited. In a recent study by Lee et al. [

6], findings indicated that interoceptive awareness, measured using the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness questionnaire, was linked to improved self-care management of symptoms in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Conversely, tendencies to ignore or distract oneself from discomfort were associated with poorer self-care practices. The authors suggest that interoception could serve as a valuable target for interventions aimed at improving self-care management behaviors in patients with cardiovascular disease. However, IA is only partially related to interoceptive awareness [

7]. Further investigations are required to establish the associations between IA and cardiological symptoms.

One of the most common cardiac symptoms is palpitations, and its possible relationship with cardioception has recently been discussed [

8]. Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) are a common cause of palpitations, while in asymptomatic individuals, they could also be detected as an accidental finding. On the one hand, arrhythmias may be asymptomatic [

9,

10]. On the other hand, the feeling of palpitations may not be caused by actual heart rhythm disturbances with a psychiatric or somatoform disorder being an underlying cause [

11,

12,

13]. In case of the absence of cardiopulmonary etiology, PVCs are often benign. However, they can cause symptoms that significantly impair the quality of life [Klewer 2022]. Thus, for benign PVCs the clinical decision about treatment strategy depends on the severity of the symptoms. In asymptomatic individuals, no treatment may be required. Nevertheless, for patients who experience palpitations that drastically affect their quality of life, antiarrhythmic drugs or even surgical treatment (ablation) may be used [

14]. These treatments, though, only aim to improve quality of life but do not affect the risk of future cardiovascular events and may have side effects. Currently, only a few studies evaluated cardiac interoception in palpitation patients and demonstrated higher IA in behavioral tests in comparison with healthy control subjects [

15,

16]. We suggest that understanding the mechanisms underlying the experience of symptoms in patients with benign PVCs would pave the way for the development of new therapeutic approaches.

In our study, we proposed that the intensity of symptoms of PVC may be associated with interoception. To test this hypothesis, we have explored interoception in patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic PVCs using two approaches (1) behavioral: we evaluated IA in two commonly used behavioral tasks: mental tracking (MT) [

17] and heartbeat detection (HBD) [

18]; (2) neurophysiological: we studied the neural marker of cardiac interoceptive processing [

19] – the HEP amplitude and its modulation (ΔHEP). Studies have demonstrated that disturbances in interoceptive signaling are linked to the regulation of emotions and stress [

20], contributing to the development of various mental health conditions, including anxiety, depression, and somatic symptom disorders [

21]. Moreover, interoceptive training has been shown to improve IA, reduce anxiety, and alleviate somatic symptoms. These effects are associated with enhanced neural activity in the anterior insular cortex [

22]. The insula cortex is involved in interoceptive [

23] and emotional processing [

24] and is also a key component of central autonomous system network [

25,

26]. At the same time, stress and imbalance in autonomic regulation are among predisposing factors for PVC [

27]. Considering the research mentioned above, to explore the potential contributions of anxiety and alexithymic traits to symptom severity in patients with PVCs, we administered the State Trait Anxiety Inventory–Trait Inventory [

28] and the Toronto Alexithymia Scale [

29] questionnaires.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants.

We calculated the sample size required to detect a within-group difference between conditions (power of 0.8, significance level of 0.05) using G*Power. An effect size of d = 0.74 was used based on the difference in HEP amplitudes between resting state and perceptual task performance in high symptom reporters as described in the literature [

30]. A paired permutation t-test (from the family of t-tests accounting for mean difference) indicated that N = 17 per group is required. A priori analyses of the required sample size for between-group comparisons were not possible due to the novelty of the design for such clinical groups, and articles with similar designs either lack an effect [

30] or the required measures of the effect size [

15]. Thus, we included 34 participants (20 females; Me [Q1; Q3] = 42 [38.25; 44.75] years old; body mass index (BMI) Me [Q1; Q3] = 24.4 [21.95; 26.65]; 17 participants had asymptomatic PVCs) who were either seeking medical care or undergoing a routine health check-up . All participants provided written informed consent, approved by the local Ethics Committee at the National Medical Research Center for Therapy and Preventive Medicine, Moscow, Russian Federation. The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

The inclusion criteria were the following: 20-50 years old, with 720-20,000 PVCs during 24-h Holter monitoring. We included only young and middle-aged patients to reduce the risk of comorbidities and cognitive impairment. Patients scoring >11 on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS, [

31]) were excluded, as depression may affect interoception [

32,

33,

34]. Additionally, participants with >20,000 PVCs during 24-hour Holter monitoring were excluded to preclude the possibility of undiagnosed structural heart pathology. Structural heart pathology in the included participants was ruled out based on their previous medical examinations, including echocardiography, stress testing, and in some cases, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.

To eliminate potential confounding factors in interoception measurements, stringent exclusion criteria were applied. The exclusion criteria were as follows: uncontrolled arterial hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg) based on office, home, or ambulatory monitoring; other arrhythmias observed using ECG or Holter monitoring; organic cardiac pathologies (e.g., heart hypertrophy, prior myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathies of various etiologies, unknown scarring, congenital heart defects); obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; significant atherosclerosis (arterial stenosis ≥50%); neurological or psychiatric disorders; thyroid dysfunction; systemic or autoimmune diseases; significant liver, kidney, or lung pathologies; epilepsy; head trauma in the past year; use of drugs crossing the blood-brain barrier; complications from viral/infectious diseases; endocrine disorders (e.g., diabetes, obesity [>30 kg/m²]); and pregnancy.

2.2. Data acquisition.

2.2.1. Symptom score

Patients were divided into symptomatic and asymptomatic groups based on the results of a cardiologist consultation and confirmed by Holter ECG monitoring results prior to EEG administration, supplemented by patient diaries documenting their sensations during the monitoring period. Patients in whom PVCs were an incidental finding and not associated with any complaints, were assigned to the asymptomatic group. In case complaints in the diary (such as irregular heartbeat, stopping, jumping, feeling of extra or skipped heartbeats, pounding or vigorous heartbeats) corresponded to PVCs on the ECG, patients were assigned to the symptomatic group. Participants in this group were then asked to rate the intensity of their PVC complaints on a scale of 1 to 10. Patients in the asymptomatic group were assigned a symptom score 0. Patients in the symptomatic group were assigned a symptom score of 1, 2, 3 for the first, second and third tertiles of the reported symptom severity, respectively.

2.2.2. Questionnaires

We used The Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) [

29] ( Russian language adaptation [

35] for alexithymia assessment to evaluate difficulties in recognising and expressing emotional experiences and bodily sensations. The scale consists of 20 questions rated from 1 to 5 points, with higher scores indicating higher levels of various aspects of alexithymia. The total alexithymia index was calculated as the sum of three subscales: difficulties identifying feelings, difficulties describing feelings, and externally oriented thinking. To assess anxiety, we used the State Trait Anxiety Inventory–Trait Inventory (STAI-T) [[

28]](Russian language adaptation by Нanin [

36]). We used the trait anxiety subscale, containing 20 statements rated from 1 to 4 points.

2.2.3. Electrophysiological data

Electrophysiological data were collected using the NVX-52 EEG amplifier (Medical Computer Systems, Ltd. [MCS]) with 36 Ag/AgCl electrodes positioned on elastic EEG caps following the international 10-20 system. Channels T3 and T4 served as ipsilateral online references, following the company recommendations. During the recordings, the impedance across all channels was maintained at around 10 kΩ and never exceeded 20 kΩ. Surface electromyography (EMG) was recorded from the first dorsal interosseous muscle using a belly-tendon montage. ECG data were obtained using three pairs of electrodes in a bipolar configuration: one pair was placed on the anterior forearm, another on the chest 2 cm below the clavicles in the infraclavicular fossae [

37]. Additionally, two EOG electrodes were placed on the lateral sides of the eyes. Data were sampled at a frequency of 500 Hz and filtered between 0.1 and 70 Hz with a 50 Hz notch filter.

2.2.4. Other variables

Body fat percentage, a more precise indicator of body composition than BMI, was assessed using bioimpedance analysis (Medass, Russia). For the maximum PVC count during 24-hour Holter monitoring, we report the results from the Holter monitoring session that recorded the highest PVC count from the six months before the experiment.

2.3. Experimental procedures

The participants were sitting quietly, with their eyes open. At the onset, five minutes of resting EEG data were recorded, during which participants were instructed to focus on the fixation cross in the middle of the screen in front of them and to avoid moving and excessive blinking. Before each of the behavioral tests, presented in random order, participants had a training session and were instructed to focus on their internal sensations.

The MT task involved counting the heartbeats during six randomly presented time intervals (25, 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50 s) [

7]. The participants had to count the number of perceived heartbeats without palpating the pulse anywhere on the body or trying to guess it.

The HBD task [

38] required participants to detect the sensation of their heartbeat and indicate it by pressing a button. The test consisted of two conditions: (1) an interoceptive condition where participants had to press the "space" button when they felt a heartbeat, and (2) an exteroceptive condition where participants were required to press the button every time they heard a 1 Hz sound signal with 500 ms duration. Both conditions consisted of a 2.5-minute trial and a 10-second training trial before it. Participants were instructed to report/press only perceived heartbeats, which helps to reduce the influence of estimation and better capture interoceptive ability [

39,

40,

41], in contrast to earlier studies, where participants were asked to rely on their intuition in case they did not feel heartbeats [

42,

43].

2.4. Data preprocessing

2.4.1. Behavioral interoceptive accuracy (IA)

IA in the HBD task (IA

HBD) was a metric of the mean difference (mean distance, md) between the pressing frequency and heartbeat frequency in the overlapping time windows [

44,

45] (Equation 1). As it was demonstrated previously [46, personal unpublished data], personal unpublished data] this metric for HBD task was more reliable than the other metrics (modified Schandry index, sensitivity d). Participants who did not make any presses were assigned IA

HBD of 0. ECG recording was divided into overlapping windows of 10-s duration beginning with the R-peak. The press-to-press intervals (PP intervals) and R-peak intervals (RR intervals) were evaluated in each window. The variation was calculated as the ratio of the standard deviation of PP intervals to their mean in the window. The window was included in the analysis if the variation of PP intervals was <0.5. The formula is:

IA in the MT task (IAMT) was assessed using a modified Schandry index (SI) formula proposed by Garfinkel et al. [

7] (Equation 2). SI corrects the IA

MT if the number of heartbeats counted by the participant (HBreport) is significantly higher than the actual number of heartbeats recorded by the ECG (HBrecord).

IAMT and IAHBD equal to 1 indicate high interoception.

2.4.2. ECG, EMG processing

The first processing step was to calculate the difference in activity between the left and right electrodes for each pair of ECG electrodes. The ECG data were then filtered between 0.5-45 Hz. The ECG signal from the pair of electrodes below the clavicles was used to calculate R-peaks, as they were the least affected by motor activity. R-peaks and PVCs were determined semi-automatically using the MNE-Python package [

47], followed by visual inspection by a cardiologist. Both sinus rhythm peaks and PVC were included in the IA calculation.

EMG data were used to assess the precise timing of the button press. Teager Kaiser Energy operator was applied to EMG to detect movement onset.

2.4.3. EEG processing

EEG was processed using the MNE-Python package [

47]. EEG was notch-filtered at 50 Hz, and then bandpass filtered from 0.5 to 45 Hz using a zero-phase FIR filter with a Hamming window. EEG data were cleaned from the eye movement and cardiac field artifacts (CFA). The independent component analysis (fastica algorithm) was used on the top of PCA components explaining 99% of the variance. We selected no more than three eye movement-related components and no more than two CFA components. EEG data were then filtered between 0.5-20 Hz. Channels affected by motor and technical artifacts were removed and then interpolated.

2.4.4. Heartbeat-evoked potentials (HEPs)

EEG data were segmented into epochs 200 ms before and 600 ms after the R-peaks in the ECG, and the average amplitude over the interval from 200 to 100 ms before the R-peak was subtracted for baseline correction. HEP amplitudes for each channel were obtained from epoch-wise averaging. We excluded epochs time-locked to PVC (two epochs before and one after), and epochs with R-peak intervals shorter than 600 ms. The AutoReject algorithm was applied to remove or interpolate noisy epochs. After automatic artifact removal, additional visual inspection of the epochs was performed. Recordings with more than 20% of epochs removed were excluded from the analysis. Thus, out of 37 subjects, 2 were excluded from the analysis (more than 20% were removed due to frequent (838 and 820 PVCs) PVCs during recordings), and data from 1 subject were missing due to technical problems during the recording. Channels were combined into spatial ROIs as previously described [

43,

48]: left frontal - LF (LF: Fp1, F3, FC3, C3, F7, FT7), central frontal -CF ( Fpz, Fz, FCz, Cz), right frontal - RF (Fp2, F4, FC4, C4, F8, FT8), left temporal - LT (TP7, CP3, P3, T5, P5, PO7), central occipital - CO (CPz, Pz, POz, Oz, PO3, O1, PO4, O2), and right temporal - RT (TP8, CP4, P4, T6, P6, PO8). HEP amplitudes among ROIs were obtained from the within-ROI epoch-wise averaging of the HEP amplitude in the range of 200-600 ms after the R peak.

2.5. Statistical analyses

2.5.1. Between-group analysis of behavioral data

The analysis was performed using the open-source R 4.3.1 environment. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Data were tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk criterion before analysis. The Wilcoxon rank sum test for independent samples with Bonferroni correction was used to compare IA between groups. Two-sided Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to investigate the relationships between IA within groups.

2.5.2. HEP statistical analyses

HEP amplitudes were compared using a nonparametric spatiotemporal permutation test based on the Monte Carlo method. The test was performed using Python 3.11 and the MNE-Python [

47]. First, HEP amplitudes were randomly assigned to groups, and t-values were calculated at each time point across channels. Next, the cluster with the largest sum of t-values was selected from the points where t-values exceeded a threshold. These steps were repeated 1000 times to form a distribution of t-values and test the null hypothesis. Based on the statistics, areas in the original data where t-values exceeded the threshold by more than 5% were selected and grouped into clusters, considering the spatial connectivity of the channels. HEP amplitude between groups were compared for six conditions (summarized in

Table 1). Within-group comparison were performed for 1) HEP

HBD compared to HEP

REST, 2) HEP

MT compared to HEP

REST and 3) HEP

HBD compared to exteroceptive conditions in the HBD task. The window of examination was from -200 to 600 ms.

Individually, for all 6 conditions, a binary logistic regression model was fitted to predict symptoms - 1 for symptoms` presence and 0 for symptoms` absence - on the basis of the 6 averaged HEP amplitudes registered in the given condition in ROIs over a window of 200-600 ms. The significance of the models was tested by likelihood ratio test (LRT).

A nonparametric Wilcoxon test for dependent samples was used to compare HEPREST and HEPHBD, HEPREST and HEPMT, and the interoceptive and exteroceptive conditions in the HBD task in ROI ∈ {LF, CF, RF, LT, RT, CO} (Section 4.3) within groups. The Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) correction was applied to the p values obtained for ROI within each of the three conditions.

2.5.3. Correlation between HEP amplitude and IA

We assessed the link between the behaviorally assessed IA and the neurophysiologic measure of interoception - the HEP amplitudes in these tasks (IA

HBD and HEP

HBD, IA

MT and HEP

MT, IA

HBD and ΔHEP

HBD-REST, IA

MT and ΔHEP

MT-REST, IA

HBD, and ΔHEP

HBD-EX). The previously described permutation test was applied with some modifications in Matlab using the Fieldtrip library [

49]. First, IA were shuffled between participants rather than HEP amplitudes. Second, t-statistics were calculated in steps. Initially, a two-sided Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between HEP amplitude and IA was calculated in the randomized data from each permutation and the observed data. The coefficient was then converted to a t-statistic.

2.5.4. Exploratory regression analysis

The analysis was performed using the open-source R 4.3.1 environment. Firstly, to explore how confounding variables (sex, age, percent body fat, STAI-T score, TAS-20 total score) influenced symptom score, we implemented Poisson Generalized Linear Models (GLM) (Model A0). Secondly, we explored how symptom score was predicted in GLM separately by behavioral and electrophysiological metrics (IA in tasks, HEP amplitude in ROI ∈ {LF, CF, RF, LT, CO, RT} (simple Models A1-A5):

A1. Symptom score ~ IAHBD

A2. Symptom score ~ IAMT

A3. Symptom score ~ ΔHEPMT-REST in ROI ∈ {LF, CF, RF, LT, CO, RT}

A4. Symptom score ~ ΔHEPHBD-REST in ROI ∈ {LF, CF, RF, LT, CO, RT}

A5. Symptom score ~ ΔHEPHBD-EX in ROI ∈ {LF, CF, RF, LT, CO, RT}

Then, to explore how confounding variables influenced the predictions, for models 1-5, we implemented multiple models adding confounding variables (Models B1-B5). Covariates in each model were tested for the lack of multicollinearity (variance inflation factor (VIF) did not exceed the threshold of 5). For simple and multiple models 3-5, we used BH correction on the p-values obtained for ROI within each of the three conditions.

Finally, we performed a data-driven analysis using behavioral and electrophysiological interoception metrics that yielded significant associations with the symptom scores (Models A6-A7, B6-B7). We used the akaike information criterion (AIC) to estimate the relative quality of GLM models.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Table 2 presents the clinical parameters of the study groups. The groups were comparable in age, but the asymptomatic group had significantly more males, significantly higher BMI (but within the normal range for both groups), and the number of PVCs during 24-hour Holter. The groups did not differ in anxiety and alexithymia. 7 (41%) participants from the symptom group had symptom severity <6 and were assigned a symptom score of 1, 4 (24%) participants had a severity between 6 and 7.83 and, respectively, a symptom score of 2, and 6 (35%) participants had a severity >7.83 and a symptom score of 3.

Interoceptive accuracy (IA)

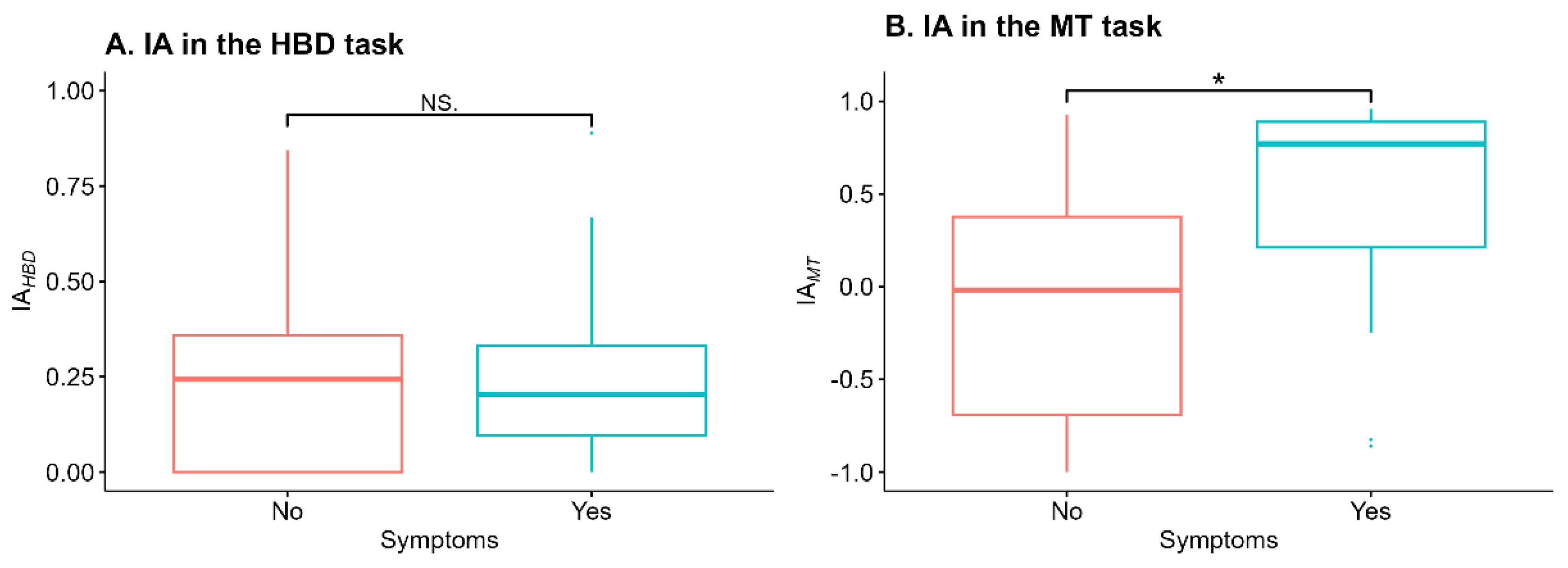

IA

HBD did not differ between groups (W = 138.5, p = .84). IA

MT in the symptomatic group (n = 17, Me [Q1; Q3]) = 0.77 [0.21; 0.89]) was significantly higher (W = 78, p = .021, after applying the Bonferroni correction p

corrected = .042) than in the asymptomatic group (n = 17, Me [Q1; Q3]) = 0.22 [0; 0.35]) (

Figure 1).

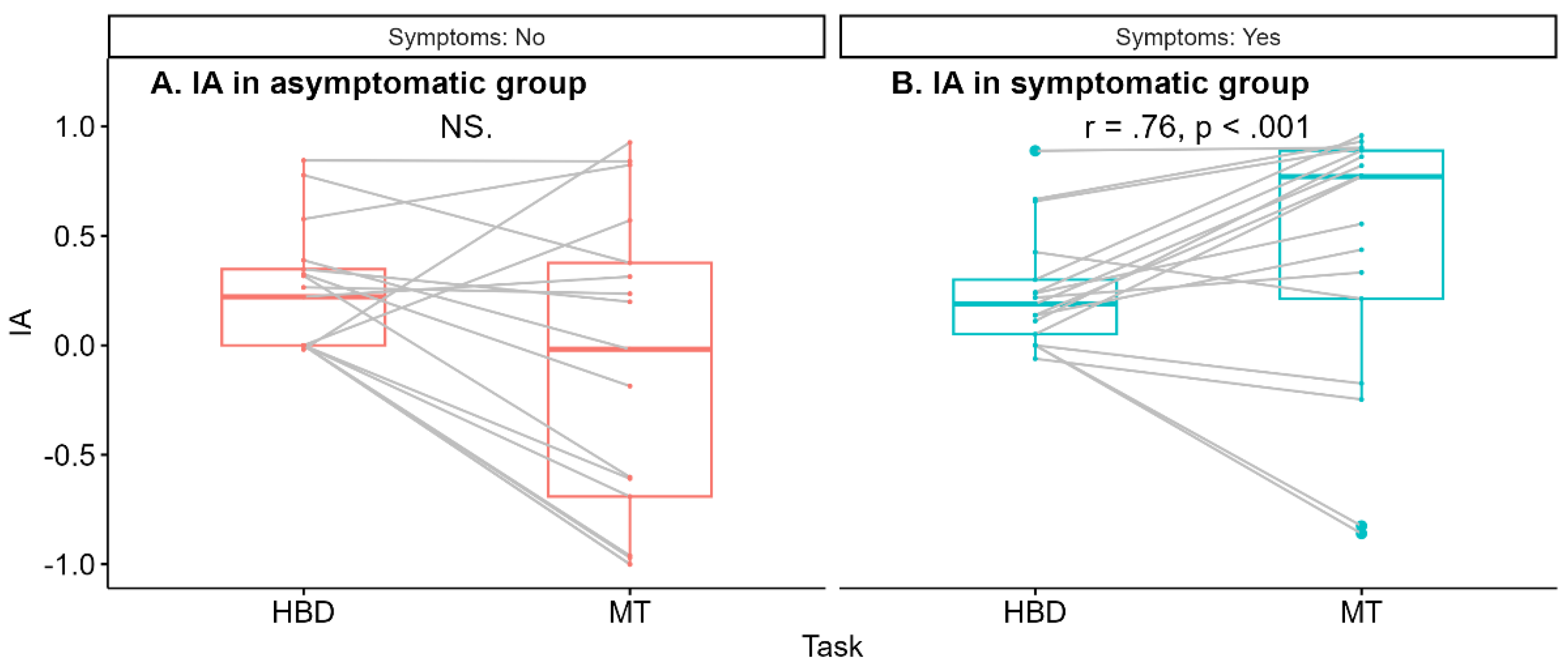

The Spearman correlation between IA

HBD and IA

MT was significant for the symptomatic group (r = .76, p < .001) in contrast to the asymptomatic group (r = .42, p = .09) (

Figure 2).

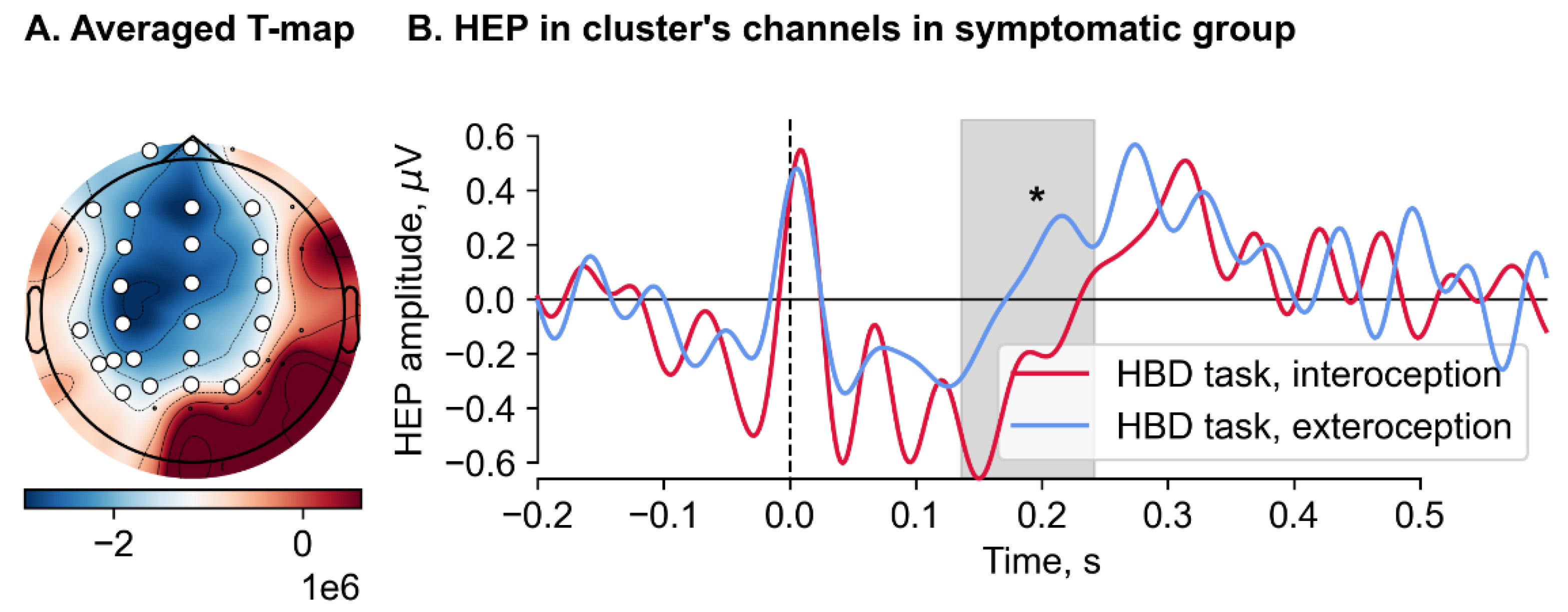

Heartbeat-evoked potential (HEPs).

We found no significant difference in the HEP amplitude during all 6 conditions between symptomatic and asymptomatic groups. A significant effect of condition was observed in the symptomatic group when comparing the HEP amplitudes recorded during the interoceptive and exteroceptive conditions in the HBD task (Monte Carlo p = .029) (

Figure 3). A significant cluster, spanned from 136 to 244 ms, included the following channels: Fp1, Fpz, F7, F3, Fz, F4, FC3, FCz, FC4, C3, Cz, C4, TP7, CP3, CPz, CP4, T5, P3, Pz, P4, P5, PO3, POz, PO4 and PO7. Cluster-averaged HEP amplitudes for the interoception (M = -0.39, SD = 0.4) were significantly less than for exteroception (M = 0.03, SD = 0.54). After restricting the time window from 200 to 600 ms, this result became nonsignificant.

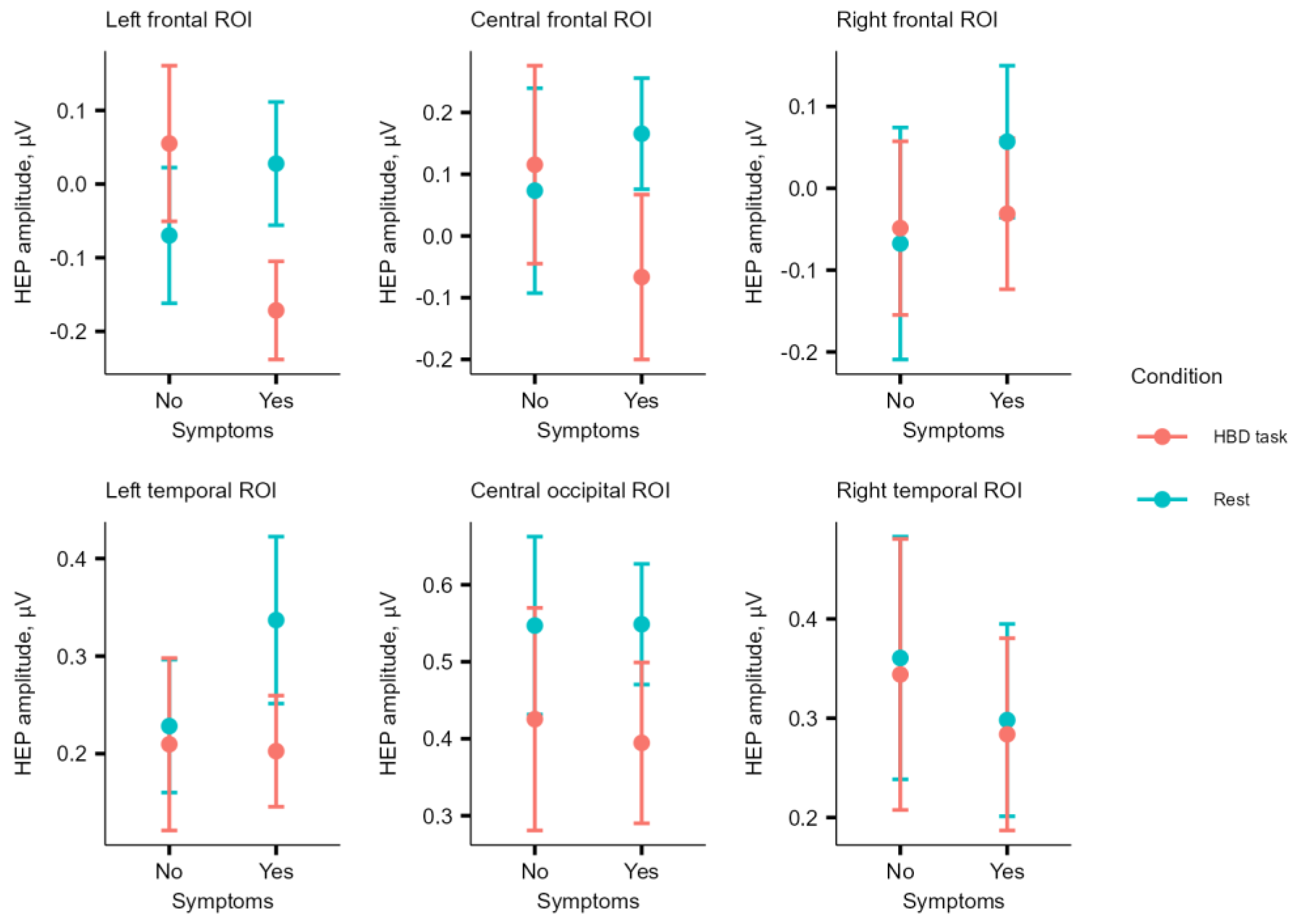

The amplitude of HEP in ROIs did not differ between conditions in the asymptomatic group. HEP

REST in CF ROI (M = 0.17, SD = 0.37) was higher (W = 33, p = .04) than HEP

HBD (M = -0.07, SD = 0.55) in the symptomatic group; however, the result did not survive BH correction (p

BH = .12) (

Figure 4).

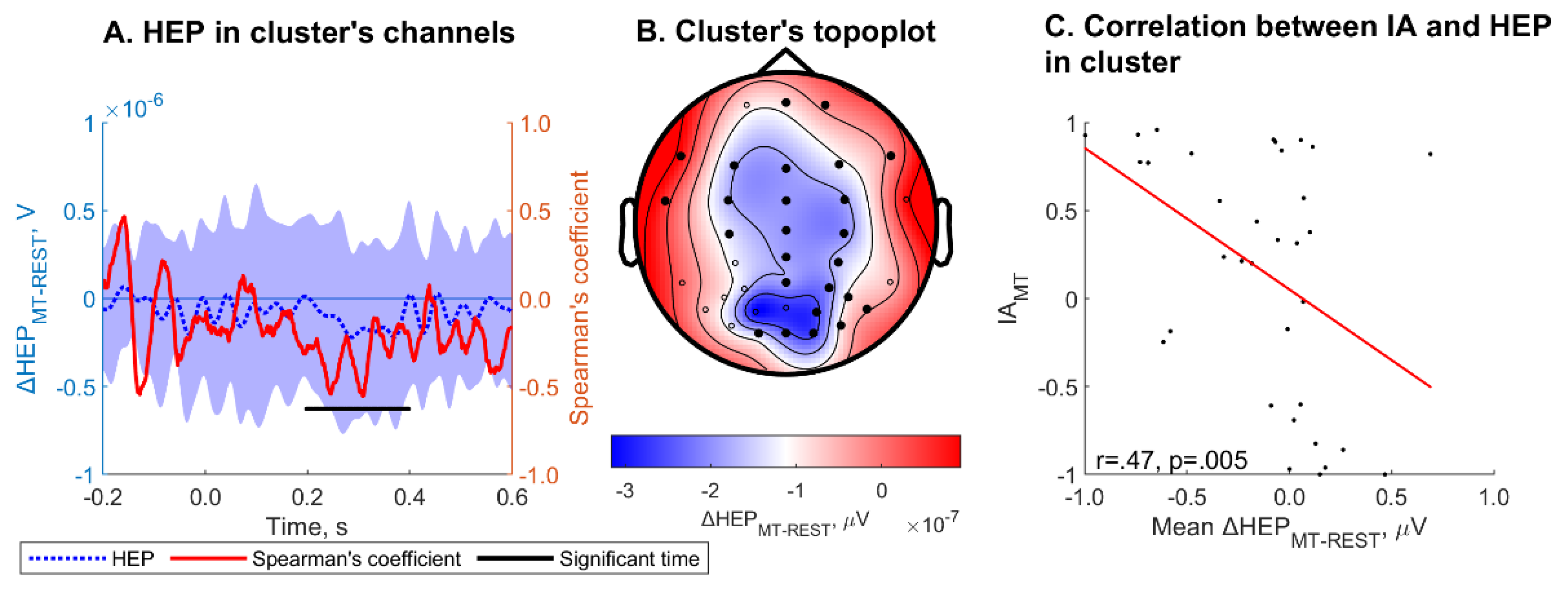

ΔHEP

MT-REST averaged within channels and over cluster time was significantly correlated with IA

MT (r = .47, p = .005) within one cluster (Monte Carlo cluster p = .005 (

Figure 5)). The cluster spanning channels Fpz, Fp2, F7, F3, Fz, F4, F8, FT7, FC3, FCz, FC4, C3, Cz, C4, CPz, CP4, Pz, P4, T6, PO4, P6, O1, Oz, O2 and PO8 and a time period ranging from 198 to 398 ms. ΔHEP

MT-REST was significantly correlated with IA

MT. HEP

HBD, HEP

MT, ΔHEP

HBD-REST, ΔHEP

HBD-EX did not correlate with IA for corresponding task.

HEPHBD in LF ROI was a significant negative predictor of symptoms presence (n = 34, β = -7.35, p = .022), LRT in logistic regression model showed a significance (p = .047) (Fig. 4). HEPMT in RT ROI was a significant negative predictor of symptoms presence (β = -7.2, p = .035), but LRT in logistic regression model showed a non-significance (p = .21). HEPREST, ΔHEPHBD-REST, ΔHEPMT-REST and ΔHEPHBD-EX were not significant predictors of symptoms presence.

Regression analyses.

Male sex in Model A0 emerged as a significant factor for lower symptom scores (β = -1.22, p = .028). IAMT, but not IAHBD, showed a significant positive effect on the symptom score (β = .82, p = .01) in a simple model, which was sustained when adding clinical parameters (β = .77, p = .025) in a multiple model.

ΔHEP

HBD-REST in LF (p = .017, p

BH = .037), CF (p = .016, p

BH = .033) ROIs and ΔHEP

HBD-EX in LF (p = .025, p

BH = .037), CF (p = .022, p

BH = .033) ROIs were significant negative predictors of symptom score in a simple model. The result for ΔHEP

HBD-REST in LT (p = .037, p

BH = .112) ROI did not survive BH correction. Adding clinical parameters to the model made nonsignificant the effect of ΔHEP

HBD-EX on the symptom score in LF and CF ROIs, and reduced to tendency the effect of ΔHEP

HBD-REST in CF (p = .019, p

BH = .058) ROI. A trend toward a significant association for ΔHEP

HBD-REST in LT (p = .019, p

BH = .058) and CO (p = .018, p

BH = .055) was observed only in the multiple models. ΔHEP

MT was not associated with the symptom score (

Table 3).

The final models included ΔHEP

HBD-REST in ROI ∈ {LF, CF, LT} and IA

MT, ΔHEP

HBD-EX in ROI ∈ {LF, CF} and IA

MT as predictors on the interoception aspect. The best model based on AIC was model B6 where ΔHEP

CONDITION is ΔHEP

HBD-REST in LT ROI (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

We hypothesized that the intensity of symptoms in PVC may be associated with interoception. To test this hypothesis, we compared IA in two behavioral tests (MT and HBD) and a neurophysiological marker of cardiac interoceptive processing - the HEP - between symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals with PVC. Interestingly, patients in the asymptomatic group had significantly higher PVC both during the experimental procedure and 24-hour Holter monitoring. This precludes discussing the results regarding symptom severity just in the context of the total number of PVC. An important methodological aspect of the HEP analysis we used is the exclusion of epochs with PVC and epochs time-locked to PVC (two before and one after the PVC) to avoid the influence of PVC on HEP and evaluated only basal HEP, which can be considered as a marker of interoception as a personal trait.

Currently, there are no broadly accepted theories that explain symptom intensity in cardiac diseases. However, some models address medically unexplained symptoms. One of these models is a perception-filter model [

50]. Schulz et al. [

30] tested the assumptions of this model to investigate alterations in the neurophysiological processing of the interoceptive signals in individuals with medically unexplained symptoms (not exteroceptive, as in previous studies [

51,

52], on which the perception-filter model was mainly based). The authors tested all three levels of this model: afferent bodily signals (evaluated via heart rate and heart rate variability), filter system activity (evaluated via ΔHEP), and perception (evaluated via IA in the behavioral tests - the MT and heartbeat discrimination tasks). The authors hypothesized that high symptom reporters would have 1) higher heart rate and relative sympathetic tone, 2) higher IA than low symptom reporters, and 3) lower filter activity, indicated by lower ΔHEP. Our results are in accordance with their hypothesis.

Interoceptive accuracy (IA) and symptoms

Hypervigilance models predict higher IA, which aligns with our findings of greater IA

MT in symptomatic patients [

53]. It could be argued, however, that the higher IA

MT in symptomatic individuals does not necessarily reflect true heartbeat perception. Instead, it may stem from symptomatic individuals' belief that they perceive their heartbeats, leading them to report a higher number, which incidentally matches the actual heartbeat count. Indeed, one of the limitations of the MT task is its inability to distinguish between true sensitivity and response bias [

54]. To explore this further, we calculated the modified Schandry index for HBD [

44,

45,

46], where a higher score indicates more frequent tapping during HBD. No difference in this index was found between groups. This result could be extrapolated to some extent to the results of MT in the sense, that patients from symptomatic group are not characterized by reporting higher numbers independent of actual perception. Additionally, IA

MT and IA

HBD correlated only in the group of symptomatic individuals, consistent with findings by Kormendi et al. [

55]. Furthermore, in contrast to the findings of Schulz et al. 2020 [

30], our results demonstrated a correlation between IA and ΔHEP, but only for MT, not HBD task. This suggests that increased attentional resources directed towards bodily sensations may enhance perceptual accuracy. These findings further support the fact that the difference in IA

MT between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with PVC reflects actual differences in interoception. Our results of higher perception are in line with a previous study by Petersen et al. [

56], who found that individuals reporting more frequent symptoms and higher levels of negative affect also showed greater accuracy in an interoceptive classification task, where they were asked to discriminate between various respiratory stimuli.

Heartbeat-evoked potential (HEPs) and symptoms.

Attention to heartbeats has previously been shown to modulate HEP amplitude [

57,

58,

59]. We initially hypothesized that symptomatic individuals would have a higher HEP

REST, an indicator of hypervigilance to internal signals, consistent with cognitive-behavioral models (for review, see [

53,

60]). In this case, due to this permanent heightened attention to the body, ΔHEP during the interoceptive test should be lower than in asymptomatic individuals. However, we found no differences in HEP

REST between the two groups. This may be due to the small sample size, as the regression analysis did capture the association between ΔHEP and symptom severity.

Within-group analyses of ΔHEP showed a significant difference between exteroceptive and interoceptive tasks in the time window from 136 ms to 244 ms for the symptomatic group, with more negative HEP observed in the interoceptive condition. However, when the analyses were restricted to the 200-600 ms time window, this result was no longer significant. While some studies selected a time window of 200 ms or more after the R-peak to avoid contamination of the HEP with cardiac artifacts [

20,

38,

57], other studies did not impose such limitations after removing cardiac field artifacts [

42,

58,

61]. These studies demonstrated HEP differences beginning before 200 ms, which aligns with our findings.

Results regarding the direction (positive or negative) of HEP deflection during cardiac interoceptive tasks vary across studies. Our results indicated that a lower ΔHEP in HBD task ( both ΔHEP

HBD-REST and ΔHEP

HBD-EX) was associated with higher symptom intensity. In the study by Couto et al. [

42], a positive deflection of ΔHEP

HBD-REST ,but not of ΔHEP

HBD-EX, was observed in control subjects. In contrast, other studies demonstrated both negative ΔHEP

HBD-REST [

61] and ΔHEP

HBD-EX deflection [

61,

62] in control subjects as well as in patients with hypertension [

38] and obsessive–compulsive disorder [

61], but not in patients with panic disorder [

61]. Additionally, the study by Leopold et al. [

63] showed no difference in HEP

HBD compared to the exteroceptive condition. For the MT task, higher HEP

MT were observed compared to both the exteroceptive condition [

59] and the HEP

REST in control subjects [

20], although this was not the case for patients with depersonalization disorders [

20]. Furthermore, higher HEP

MT were reported in high symptom reporters, but not in low symptom reporters [

30]. In another study, participants did not perform any cardiac interoceptive tasks but were instructed to focus their attention either on their own heartbeat or on white noise emitted through headphones. HEP was significantly higher during attention to the heartbeat [

57].

The insular cortex, prefrontal cortex and left somatosensory cortex [

23,

64] as well as the frontal-temporal cortex [

65] were described as one of the sources of HEP generation. Previous studies in the sensor domain showed that there is an effect of attention to heartbeat pronounced in the modulation of HEP in frontal-central regions [

3], as well as an effect of AF presence in patients characterized by modulation of HEP in the frontal-temporal regions [

66]. The left lateralization of insular involvement during HBD task was demonstrated by Fittiapldi et.al [

46]. We found modulation in left-frontal, fronto-central and left temporal regions, which is in line with previous studies. We hypothesize that HEP modulation in these regions may indicate a role of interoception in the formation of symptoms associated with cardiovascular pathology.

Multimodality of symptom intensity

The multimodal nature of interoception is known to be influenced by factors such as sex and age [

67,

68]. Studies on the contribution of clinical factors to cardiac disease symptomatology have mainly focused on patients with atrial fibrillation . According to them it can be concluded that female sex, young age were associated with symptomatic AF [

69,

70,

71], while male sex and older age were associated with asymptomatic atrial fibrillation [

72,

73]. In studies with gut interoception, female sex was also associated with gastrointestinal symptom severity [

74]. Similarly, patients with palpitation caused by awareness of sinus rhythm were significantly more likely to be women than those with palpitation due to arrhythmias [

75]. The distribution of sex in our groups is consistent with this (with female preponderance in symptomatic group), and regression analyses showed that male sex predicted a low symptom score. However, there is a study showing that patients who under-estimated the length and frequency of atrial fibrillation episodes could be predicted by female sex [

76], and a study where older patients had better matching of symptoms with ECG activity [

10]. The lack of influence of age on the symptom score in our work is consistent with a study in which asymptomatic patients with atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter/atrial tachycardia after ablation were not predicted by age [

9].

Rouse et al. (1988) showed a negative relationship between IA and BMI and percentage of fat mass in healthy individuals. Patients with higher BMI also demonstrated interoceptive deficits [

77]. Studies on other clinical groups with comorbid overweight and obesity have shown a direct association between increased BMI and greater symptom severity. For instance, higher BMI was linked to more severe symptoms in women with fibromyalgia syndrome, as measured by the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ-R) [

78]. Similarly, in patients with atrial fibrillation, elevated BMI was associated with higher symptom burden scores, assessed using the Toronto Atrial Fibrillation Severity Scale (AFSS) [

79]. Additionally, in patients with metabolic syndrome, body fat percentage was correlated with increased severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms [

80]. In our study, the lack of influence of body composition on symptom scores can be explained by the fact that (1) there was no variability in body fat percentage in the non-obese sample, which did not allow testing associations; (2) body composition is not involved in the formation of PVC symptomatology.

Alexithymia, defined as difficulties in identifying and describing one's own feelings, is characterised by impaired interoception [

81], which, in its turn, is related to emotional processing [

82]. Previous research has demonstrated a higher prevalence of alexithymia in patients with medically unexplained symptoms, with a correlation between alexithymia and symptom severity [

83]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the presence or absence of symptoms of PVC may be associated with alexithymia. However, multiple regression models identified no associations of alexithymia and symptom intensity as the response variable. Although inverse associations between IA

MT and alexithymic traits in a group of healthy subjects have been demonstrated [

81,

84], recent meta-analyses by Desmedt [

67] have revealed no significant associations between IA

MT and trait anxiety or alexithymia. The authors hypothesized that this may be due to the inability of the IA

MT to adequately capture individual differences in interoception. Indeed, the existing literature on the relationship between interoception and alexithymia is inconclusive, with findings varying depending on the methodological approach employed. In the study by Flasbeck et al. [

85], there was a positive correlation between HEP amplitudes over frontal electrodes and alexithymia for the entire study sample (control subjects and patients with borderline personality disorder), but not within the aforementioned groups. This may explain the absence of associations between alexithymia and symptom severity in our study, because participants did not have any psychological or psychiatric disorders and exhibited low alexithymia. Consequently, the TAS-20 score may not have been sufficiently sensitive to detect subtle differences in emotional processing.

Palser et al. [

86] demonstrated that the combination of altered interoceptive processing and alexithymia is linked to a higher risk of developing anxiety disorders compared to altered interoception alone. Notably, palpitations are among the common symptoms reported by patients with anxiety disorders [

13]. Conversely, the presence of an actual arrhythmia may be associated with anxiety, resulting in misdiagnosis as anxiety or panic disorder [

87,

88,

89]. The study by Rutledge et al. demonstrated that women's perceptions of their risk for coronary artery disease were more closely linked to symptoms of anxiety than to their actual coronary artery disease status [

90]. Moreover, studies have shown an association between anxiety and the severity of symptoms in chronic gastrointestinal diseases [

91,

92] as well as in functional somatic syndromes [

93]. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that the inclusion of trait anxiety into the regression models would contribute to an improvement in their quality. However, no association with symptom intensity was identified. Our negative results may be attributed to the non-uniform relationship between anxiety and symptom perception, as previously demonstrated by Chen et al. [

94].

Interoceptive metrics for predicting symptom score

One of the aims of the current study was to evaluate which of the interoceptive metrics discussed above would result in a better model for predicting symptom scores. Results from simple GLM models showed that 1) the behavioral interoceptive metric IAMT, but not IAHBD, and 2) the electrophysiological metric ΔHEPHBD-REST, but not ΔHEPMT-REST, showed associations with symptom score. Association for ΔHEPHBD-EX became not significant after inclusion of clinical parameters in the model. Despite the correlation between IAMT and ΔHEPMT-REST, models including ΔHEPMT-REST showed no associations with symptom score. This may indicate complex interactions between symptom perception, IA and HEP amplitude. Probably, ΔHEP represents individual perceptive ability, and IA may be just an indicator of this ability. As IAMT did not correlate with ΔHEPHBD-REST we performed data-driven multivariate regression including these metrics as predictors in a joint regression model, which yielded the best result for predicting symptom score. It was quite unexpected that in binary logistic regression models HEPHBD, but not ΔHEPHBD-REST (as in GLM models), was a significant negative predictor of symptom presence. It can be suggested that for robust prediction (presence or absence of symptoms) the absolute HEP value during the HBD task is sufficient, but for more accurate prediction (the intensity of symptoms) the HEP modulation (difference between resting state and interoceptive task) should be used.

A limitation of this study is that the sample size may have been insufficient to detect differences in HEP amplitudes (rather than modulation) across different conditions between groups.

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between interoception and symptom severity in PVC. By applying strict exclusion criteria and selecting only young patients without comorbidities, we aimed to minimize confounding effects, allowing a clearer analysis of the association between interoception and symptom intensity. Our findings confirm that interoception is significantly associated with PVC symptom severity, supporting our initial hypothesis. The results suggest that integrating both approaches (behavioral and neurophysiological) to assess interoception improves the accuracy of predicting symptom intensity. This insight opens promising avenues for the development of novel diagnostic strategies for PVC, with interoception emerging as a potential target for non-invasive and non-pharmacological treatment approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L., A.E., M.N.; Methodology, A.L., A.S., I.M., A.E., K.D.; Software, I.M. ; Formal Analysis, I.M., S.K., V.K. ; Investigation, A.L., I.M., A.S.; Data Curation, A.L., I.M., A.S., K.D. ; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, A.L., I.M.; Writing – Review & Editing, A.E., M.N., A.S., V.K.; Visualization, I.M.; Supervision, A.E., O.D.; Project Administration, A.L., A.E.; Funding Acquisition, A.L., A.E., M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, grant number 22-15-00507, https://rscf.ru/en/project/22-15-00507/

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the local Ethics Committee of the National Medical Research Center for Therapy and Preventive Medicine (protocol code 02-02/21, date of approval 25.02.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified - not applicable (patients` data can not be identified).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Nikulin V.V. for counseling during the study conduction, data analyses and manuscript preparation

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, W.G.; Schloesser, D.; Arensdorf, A.M.; Simmons, J.M.; Cui, C.; Valentino, R.; Gnadt, J.W.; Nielsen, L.; Hillaire-Clarke, C.S.; Spruance, V.; et al. The Emerging Science of Interoception: Sensing, Integrating, Interpreting, and Regulating Signals within the Self. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmedt, O.; Luminet, O.; Walentynowicz, M.; Corneille, O. The New Measures of Interoceptive Accuracy: A Systematic Review and Assessment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 153, 105388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coll, M.P.; Hobson, H.; Bird, G.; Murphy, J. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between the Heartbeat-Evoked Potential and Interoception. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 122, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaz, B.; Lane, R.D.; Oshinsky, M.L.; Kenny, P.J.; Sinha, R.; Mayer, E.A.; Critchley, H.D. Diseases, Disorders, and Comorbidities of Interoception. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, G.; Matus, A.; James, R.; Salmoirago-Blotcher, E.; Ausili, D.; Vellone, E.; Riegel, B. What Is the Role of Interoception in the Symptom Experience of People with a Chronic Condition? A Systematic Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Chu, S.H.; Dunne, J.; Spintzyk, E.; Locatelli, G.; Babicheva, V.; Lam, L.; Julio, K.; Chen, S.; Jurgens, C.Y. Body Listening in the Link between Symptoms and Self-Care Management in Cardiovascular Disease: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Descriptive Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024, 156, 104809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, S.N.; Seth, A.K.; Barrett, A.B.; Suzuki, K.; Critchley, H.D. Knowing Your Own Heart: Distinguishing Interoceptive Accuracy from Interoceptive Awareness. Biol. Psychol. 2015, 104, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandiah, J.W.; Blumberger, D.M.; Rabkin, S.W. The Fundamental Basis of Palpitations: A Neurocardiology Approach. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2021, 18, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Champagne, J.; Sapp, J.; Essebag, V.; Novak, P.; Skanes, A.; Morillo, C.A.; Khaykin, Y.; Birnie, D. Discerning the Incidence of Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Episodes of Atrial Fibrillation before and after Catheter Ablation (DISCERN AF): A Prospective, Multicenter Study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsky, A.J.; Cleary, P.D.; Barnett, M.C.; Christiansen, C.L.; Ruskin, J.N. The Accuracy of Symptom Reporting by Patients Complaining of Palpitations. Am. J. Med. 1994, 97, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsbu, E.; Dammen, T.; Morken, G.; Lied, A.; Vik-Mo, H.; Martinsen, E.W. Cardiac and Psychiatric Diagnoses among Patients Referred for Chest Pain and Palpitations. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2009, 43, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsky, A.J.; Cleary, P.D.; Sarnie, M.K.; Ruskin, J.N. Panic Disorder, Palpitations, and the Awareness of Cardiac Activity. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1994, 182, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsky, A.J.; Delamater, B.A.; Clancy, S.A.; Antman, E.M.; Ahern, D.K. Somatized Psychiatric Disorder Presenting as Palpitations. Arch. Intern. Med. 1996, 156, 1102–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeppenfeld, K.; Tfelt-Hansen, J.; de Riva, M.; Winkel, B.G.; Behr, E.R.; Blom, N.A.; Charron, P.; Corrado, D.; Dagres, N.; de Chillou, C.; et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3997–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsky, A.; Cleary, P.; Brener, J.; Ruskin, J. The Perception of Cardiac Activity in Medical Outpatients. Cardiology 1993, 83, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehlers, A.; Mayou, R.A.; Sprigings, D.C.; Birkhead, J. Psychological and Perceptual Factors Associated with Arrhythmias and Benign Palpitations. Psychosom. Med. 2000, 62, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schandry, R. Heart Beat Perception and Emotional Experience. Psychophysiology 1981, 18, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, R.A. Heart Rate Perception and Heart Rate Control. Psychophysiology 1975, 12, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.D.; Blanke, O. Heartbeat-Evoked Cortical Responses: Underlying Mechanisms, Functional Roles, and Methodological Considerations. Neuroimage 2019, 197, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, A.; Köster, S.; Beutel, M.E.; Schächinger, H.; Vögele, C.; Rost, S.; Rauh, M.; Michal, M. Altered Patterns of Heartbeat-Evoked Potentials in Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder: Neurophysiological Evidence for Impaired Cortical Representation of Bodily Signals. Psychosom. Med. 2015, 77, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalsa, S.S.; Lapidus, R.C. Can Interoception Improve the Pragmatic Search for Biomarkers in Psychiatry? Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, A.; Katsunuma, R.; Terasawa, Y.; Sekiguchi, A. Interoceptive Training Impacts the Neural Circuit of the Anterior Insula Cortex. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critchley, H.D.; Wiens, S.; Rotshtein, P.; Öhman, A.; Dolan, R.J. Neural Systems Supporting Interoceptive Awareness. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, J.; Davis, J.I.; Ochsner, K.N. Overlapping Activity in Anterior Insula during Interoception and Emotional Experience. Neuroimage 2012, 62, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Wittbrodt, M.; Bremner, J.; Vaccarino, V. Cardiovascular Pathophysiology from the Cardioneural Perspective and Its Clinical Applications. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, M.; Hoshide, S.; Kario, K. The Insular Cortex and Cardiovascular System: A New Insight into the Brain-Heart Axis. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2010, 4, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungar, I.M.; Rama Krishna Reddy, M.M.; Flores, S.M.; Pokhrel, P.; Ibrahim, A.D. The Influence of Lifestyle Factors on the Occurrence and Severity of Premature Ventricular Contractions: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.; Gorsuch, R.; Lushene, R. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consult. Psychol. Press: Palo Alto, CA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Bagby, R.M.; Parker, J.D.A.; Taylor, G.J. The Twenty-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale—I. Item Selection and Cross-Validation of the Factor Structure. J. Psychosom. Res. 1994, 38, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, A.; Rost, S.; Flasinski, T.; Dierolf, A.M.; Lutz, A.P.C.; Münch, E.E.; Mertens, V.C.; Witthöft, M.; Vögele, C. Distinctive Body Perception Mechanisms in High versus Low Symptom Reporters: A Neurophysiological Model for Medically-Unexplained Symptoms. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 137, 110223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhaar, J.; Viola, F.C.; Bär, K.J.; Debener, S. Heartbeat Evoked Potentials Mirror Altered Body Perception in Depressed Patients. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 123, 1950–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkinson, P.M.; Fotopoulou, A.; Ibañez, A.; Rossell, S. Interoception in Anxiety, Depression, and Psychosis: A Review. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 73, 102673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harshaw, C. Interoceptive Dysfunction: Toward an Integrated Framework for Understanding Somatic and Affective Disturbance in Depression. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 311–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starostina, Е.G.; Taylor, G.D.; Quilty, L.; Bobrov, A.Е.; Мoshnyaga, Е.N.; Puzyrevа, N. V.; Bobrovа, М.А.; Ivashkina, М.G.; Krivchikova, М.N.; Shavrikova, Е.P.; et al. A New 20-Item Version of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale: Validation of the Russian Language Translation in a Sample of Medical Patients. Soc. Clin. psychiatry (In Russ.) 2010, 20, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hanin, Y. A Brief Guide for the Spielberger C.D. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (In Russ.); LNI-ITEK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M.A.; Taggart, P.; Sutton, P.M.; Groves, D.; Holdright, D.R.; Bradbury, D.; Brull, D.; Critchley, H.D. A Cortical Potential Reflecting Cardiac Function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 6818–6823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoris, A.; Abrevaya, S.; Esteves, S.; Salamone, P.; Lori, N.; Martorell, M.; Legaz, A.; Alifano, F.; Petroni, A.; Sánchez, R.; et al. Multilevel Convergence of Interoceptive Impairments in Hypertension: New Evidence of Disrupted Body–Brain Interactions. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018, 39, 1563–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccaro, A.; della Penna, F.; Mussini, E.; Parrotta, E.; Perrucci, M.G.; Costantini, M.; Ferri, F. Attention to Cardiac Sensations Enhances the Heartbeat-Evoked Potential during Exhalation. iScience 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.C.; Gentsch, A.; Jelinčić, V.; Schütz-Bosbach, S. Exteroceptive Expectations Modulate Interoceptive Processing: Repetition-Suppression Effects for Visual and Heartbeat Evoked Potentials. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmedt, O.; Luminet, O.; Corneille, O. The Heartbeat Counting Task Largely Involves Non-Interoceptive Processes: Evidence from Both the Original and an Adapted Counting Task. Biol. Psychol. 2018, 138, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, B.; Salles, A.; Sedeño, L.; Peradejordi, M.; Barttfeld, P.; Canales-Johnson, A.; Vidal, Y.; Santos, D.; Huepe, D.; Bekinschtein, T.; et al. The Man Who Feels Two Hearts: The Different Pathways of Interoception. SCAN 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollatos, O.; Schandry, R. Accuracy of Heartbeat Perception Is Reflected in the Amplitude of the Heartbeat-Evoked Brain Potential. Psychophysiology 2004, 41, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrevaya, S.; Fittipaldi, S.; García, A.M.; Dottori, M.; Santamaria-Garcia, H.; Birba, A.; Yoris, A.; Hildebrandt, M.K.; Salamone, P.; De la Fuente, A.; et al. At the Heart of Neurological Dimensionality: Cross-Nosological and Multimodal Cardiac Interoceptive Deficits. Psychosom. Med. 2020, 82, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoris, A.; Legaz, A.; Abrevaya, S.; Alarco, S.; López Peláez, J.; Sánchez, R.; García, A.M.; Ibáñez, A.; Sedeño, L. Multicentric Evidence of Emotional Impairments in Hypertensive Heart Disease. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fittipaldi, S.; Abrevaya, S.; Fuente, A. de la; Pascariello, G.O.; Hesse, E.; Birba, A.; Salamone, P.; Hildebrandt, M.; Martí, S.A.; Pautassi, R.M.; et al. A Multidimensional and Multi-Feature Framework for Cardiac Interoception. Neuroimage 2020, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramfort, A. MEG and EEG Data Analysis with MNE-Python. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A.P.C.; Schulz, A.; Voderholzer, U.; Koch, S.; van Dyck, Z.; Vögele, C. Enhanced Cortical Processing of Cardio-Afferent Signals in Anorexia Nervosa. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019, 130, 1620–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostenveld, R.; Fries, P.; Maris, E.; Schoffelen, J.-M. FieldTrip: Open Source Software for Advanced Analysis of MEG, EEG, and Invasive Electrophysiological Data. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2011, 2011, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rief, W.; Barsky, A.J. Psychobiological Perspectives on Somatoform Disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005, 30, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, E.; Kraiuhin, C.; Meares, R.; Howson, A. Auditory Evoked Response Potentials in Somatization Disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1986, 20, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.; Gordon, E.; Kraiuhin, C.; Howson, A.; Meares, R. Augmentation of Auditory Evoked Potentials in Somatization Disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1990, 24, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, C.; Gerlach, A.L.; Pohl, A. Interoceptive Accuracy and Bias in Somatic Symptom Disorder, Illness Anxiety Disorder, and Functional Syndromes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körmendi, J.; Ferentzi, E.; Köteles, F. Expectation Predicts Performance in the Mental Heartbeat Tracking Task. Biol. Psychol. 2021, 164, 108170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körmendi, J.; Ferentzi, E.; Petzke, T.; Gál, V.; Köteles, F. Do We Need to Accurately Perceive Our Heartbeats? Cardioceptive Accuracy and Sensibility Are Independent from Indicators of Negative Affectivity, Body Awareness, Body Image Dissatisfaction, and Alexithymia. PLoS One 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, S.; Van Staeyen, K.; Vögele, C.; von Leupoldt, A.; Van den Bergh, O. Interoception and Symptom Reporting: Disentangling Accuracy and Bias. Front. Psychol. 2015, 06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzschner, F.H.; Weber, L.A.; Wellstein, K. V.; Paolini, G.; Do, C.T.; Stephan, K.E. Focus of Attention Modulates the Heartbeat Evoked Potential. Neuroimage 2019, 186, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Yan, H.-M.; Xu, X.-G.; Han, F.; Yan, Q. Effect of Heartbeat Perception on Heartbeat Evoked Potential Waves. Neurosci. Bull. 2007, 23, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, P.; Schandry, R.; Müller, A. Heartbeat Evoked Potentials (HEP): Topography and Influence of Cardiac Awareness and Focus of Attention. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. Potentials Sect. 1993, 88, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rief, W.; Broadbent, E. Explaining Medically Unexplained Symptoms-Models and Mechanisms. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 821–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoris, A.; García, A.M.; Traiber, L.; Santamaría-García, H.; Martorell, M.; Alifano, F.; Kichic, R.; Moser, J.S.; Cetkovich, M.; Manes, F.; et al. The Inner World of Overactive Monitoring: Neural Markers of Interoception in Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 1957–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cordero, I.; Esteves, S.; Mikulan, E.P.; Hesse, E.; Baglivo, F.H.; Silva, W.; García, M. del C.; Vaucheret, E.; Ciraolo, C.; García, H.S.; et al. Attention, in and Out: Scalp-Level and Intracranial EEG Correlates of Interoception and Exteroception. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, C.; Schandry, R. The Heartbeat-Evoked Brain Potential in Patients Suffering from Diabetic Neuropathy and in Healthy Control Persons. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2001, 112, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollatos, O.; Kirsch, W.; Schandry, R. Brain Structures Involved in Interoceptive Awareness and Cardioafferent Signal Processing: A Dipole Source Localization Study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2005, 26, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.D.; Bernasconi, F.; Salomon, R.; Tallon-Baudry, C.; Spinelli, L.; Seeck, M.; Schaller, K.; Blanke, O. Neural Sources and Underlying Mechanisms of Neural Responses to Heartbeats, and Their Role in Bodily Self-Consciousness: An Intracranial EEG Study. Cereb. cortex 2018, 28, 2351–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumral, D.; Al, E.; Cesnaite, E.; Kornej, J.; Sander, C.; Hensch, T.; Zeynalova, S.; Tautenhahn, S.; Hagendorf, A.; Laufs, U.; et al. Attenuation of the Heartbeat-Evoked Potential in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmedt, O.; Van Den Houte, M.; Walentynowicz, M.; Dekeyser, S.; Luminet, O.; Corneille, O. How Does Heartbeat Counting Task Performance Relate to Theoretically-Relevant Mental Health Outcomes? A Meta-Analysis. Collabra Psychol. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalsa, S.S.; Rudrauf, D.; Tranel, D. Interoceptive Awareness Declines with Age. Psychophysiology 2009, 46, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, C.; Boone, J.; Connolly, S.; Greene, M.; Klein, G.; Sheldon, R.; Talajic, M. Follow-up of Atrial Fibrillation: The Initial Experience of the Canadian Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 1996, 17, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, M.; Roy, D.; Talajic, M.; Newman, D.; Couturier, A.; Yang, C.; Dorian, P. Role of Gender and Personality on Quality-of-Life Impairment in Intermittent Atrial Fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2000, 86, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.R.; Lavelle, T.; Essebag, V.; Cohen, D.J.; Zimetbaum, P. Influence of Age, Sex, and Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence on Quality of Life Outcomes in a Population of Patients with New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation: The Fibrillation Registry Assessing Costs, Therapies, Adverse Events and Lifestyle (FRACTAL) Study. Am. Heart J. 2006, 152, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, F.N. Characteristics and Prognosis of Lone Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 1985, 254, 3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaker, G.C.; Belew, K.; Beckman, K.; Vidaillet, H.; Kron, J.; Safford, R.; Mickel, M.; Barrell, P. Asymptomatic Atrial Fibrillation: Demographic Features and Prognostic Information from the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Study. Am. Heart J. 2005, 149, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavroudis, G.; Strid, H.; Jonefjäll, B.; Simrén, M. Visceral Hypersensitivity Is Together with Psychological Distress and Female Gender Associated with Severity of IBS-like Symptoms in Quiescent Ulcerative Colitis. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayou, R.; Sprigings, D.; Birkhead, J.; Price, J. Characteristics of Patients Presenting to a Cardiac Clinic with Palpitation. QJM - Mon. J. Assoc. Physicians 2003, 96, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garimella, R.S.; Chung, E.H.; Mounsey, J.P.; Schwartz, J.D.; Pursell, I.; Gehi, A.K. Accuracy of Patient Perception of Their Prevailing Rhythm: A Comparative Analysis of Monitor Data and Questionnaire Responses in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Hear. Rhythm 2015, 12, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Foote, G.; Smith, J.; Higgs, S.; Jones, A. Interoception and Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Interoception and BMI. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 45, 2515–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Rodríguez, M.; El Mansouri-Yachou, J.; Casas-Barragán, A.; Molina, F.; Rueda-Medina, B.; Aguilar-Ferrándiz, M.E. The Association of Body Mass Index and Body Composition with Pain, Disease Activity, Fatigue, Sleep and Anxiety in Women with Fibromyalgia. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalazan, B.; Dickerman, D.; Sridhar, A.; Farrell, M.; Gayle, K.; Samuels, D.C.; Shoemaker, B.; Darbar, D. Relation of Body Mass Index to Symptom Burden in Patients WithAtrial Fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2018, 122, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, E.P.; Madeira, E.; Mafort, T.T.; Madeira, M.; Moreira, R.O.; Mendonça, L.M.; Godoy-Matos, A.F.; Lopes, A.J.; Farias, M.L.F. Body Composition and Depressive/Anxiety Symptoms in Overweight and Obese Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2013, 5, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Catmur, C.; Bird, G. Alexithymia Is Associated with a Multidomain, Multidimensional Failure of Interoception: Evidence from Novel Tests. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2018, 147, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamone, P.C.; Legaz, A.; Sedeño, L.; Moguilner, S.; Fraile-Vazquez, M.; Campo, C.G.; Fittipaldi, S.; Yoris, A.; Miranda, M.; Birba, A.; et al. Interoception Primes Emotional Processing: Multimodal Evidence from Neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 4276–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rady, A.; Alamrawy, R.G.; Ramadan, I.; El Raouf, M.A. Prevalence of Alexithymia in Patients with Medically Unexplained Physical Symptoms: A Cross-Sectional Study in Egypt. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Heal. 2021, 17, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, B.M.; Herbert, C.; Pollatos, O. On the Relationship between Interoceptive Awareness and Alexithymia: Is Interoceptive Awareness Related to Emotional Awareness? J. Pers. 2011, 79, 1149–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flasbeck, V.; Popkirov, S.; Ebert, A.; Brüne, M. Altered Interoception in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder: A Study Using Heartbeat-Evoked Potentials. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregulation 2020, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palser, E.R.; Palmer, C.E.; Galvez-Pol, A.; Hannah, R.; Fotopoulou, A.; Kilner, J.M. Alexithymia Mediates the Relationship between Interoceptive Sensibility and Anxiety. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0203212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frommeyer, G.; Eckardt, L.; Breithardt, G. Panic Attacks and Supraventricular Tachycardias: The Chicken or the Egg? Netherlands Hear. J. 2013, 21, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnlöf, C.; Iwarzon, M.; Jensen-Urstad, M.; Gadler, F.; Insulander, P. Women with PSVT Are Often Misdiagnosed, Referred Later than Men, and Have More Symptoms after Ablation. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2017, 51, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessmeier, T.J.; Gamperling, D.; Johnson-Liddon, V.; Fromm, B.S.; Steinman, R.T.; Meissner, M.D.; Lehmann, M.H. Unrecognized Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia. Potential for Misdiagnosis as Panic Disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 1997, 157, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, T.; Kenkre, T.S.; Bittner, V.; Krantz, D.S.; Thompson, D. V.; Linke, S.E.; Eastwood, J.-A.; Eteiba, W.; Cornell, C.E.; Vaccarino, V.; et al. Anxiety Associations with Cardiac Symptoms, Angiographic Disease Severity, and Healthcare Utilization: The NHLBI-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 2335–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Tang, J.; Wang, W.; Lu, L. Relationship Between Severity of Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Anxiety Symptoms in Patients with Chronic Gastrointestinal Disease: The Mediating Role of Illness Perception. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, Volume 16, 4921–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reigada, L.C.; Hoogendoorn, C.J.; Walsh, L.C.; Lai, J.; Szigethy, E.; Cohen, B.H.; Bao, R.; Isola, K.; Benkov, K.J. Anxiety Symptoms and Disease Severity in Children and Adolescents With Crohn Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 60, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henningsen, P.; Zimmermann, T.; Sattel, H. Medically Unexplained Physical Symptoms, Anxiety, and Depression. Psychosom. Med. 2003, 65, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Hermann, C.; Rodgers, D.; Oliver-Welker, T.; Strunk, R.C. Symptom Perception in Childhood Asthma: The Role of Anxiety and Asthma Severity. Heal. Psychol. 2006, 25, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).