1. Introduction

The promotion of buildings’ energy performance, like other Green Deal (GD) initiatives, faces competitive interests. Although the global goal is shared [

1], the priorities of countries, international corporations, municipalities, entrepreneurs across various industries, households, and other stakeholders often conflict.

Neither global organizations, nor the EU have the resources necessary to finance achieving climate goals, including substantial reductions in building energy consumption and phasing out fossil fuels. Approach of the European Commission’s normative package “Fit for 55,” as set out in recent amendments to EU directives, have placed additional expenditures on household, business, and government budgets in the short and medium term. Entrepreneurs and households are expected to bear some of the costs of climate goals, while the mediating role of local governments (LG) is growing [

2]. The payback period for loans on energy performance improvements is expected in 20+ years, making it challenging to persuade the private sector to invest in building renovations in the short term.

The European Charter of Local Self-Governments [

3] has harmonized LG systems in Europe and their relationships with national governments and residents. Participation in GD initiatives depends on each country’s unique context, including energy supply, climate, and historical construction practices, as well as the division of responsibilities and rights between the national government and municipalities.

The amendments to directives [

4,

5,

6] under the “Fit for 55” package determine the energy efficiency responsibilities of sub-national governments. Municipalities play a dual role in GD policy: they act as agents in enforcing mandatory requirements under national climate and energy plans while also formulating and implementing their own plans autonomously, addressing local interest groups' concerns, which may, in some cases, take priority.

For municipalities spatial planning, demonstration of energy efficiency in public buildings, organization of heating services, and piloting new technologies within their territories are key socioeconomic activities to improve building energy performance. In most countries, responsibility for social welfare is shared between national governments and municipalities. The state establishes general guidelines and ensures uniform social support, while municipalities assess individual households' situations to provide tailored assistance.

LGs need to consider how their decisions align with both EU and national government positions and the interests of local residents and businesses. The local population expects both an improvement in the quality of life and alignment with the common ideals of society. However, residents’ preferences can vary widely, with diverse interest groups influencing socioeconomic development, legislating, and its implementation at all levels of governance. Organized civil society, especially business organizations and climate activists, actively lobby their interests to public authorities. Even passive citizens affect decision-making, as building performance policies may be evaluated in public/social communication.

The influence of interest groups on forming international climate policy has been studied, mainly by analyzing the impact of lobbying on national policy and positioning [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. However, research on how local interests affect climate and environmental policies is fragmented across themes, such as whether public participation leads to more ambitious, transformative local governance of climate policy [

12,

13,

14,

15]. The authors have found no study examining the influence of interest representation on LGs' autonomous decisions in climate policy.

Studying current and potential interactions between municipalities and various interest groups within a specific country is more effective. Latvia was chosen for this study due to its moderate level of LG system decentralization in comparison with other EU countries [

16], making it suitable for examining the environment for autonomous decision-making.

This study explores the competing challenges that LGs face due to geopolitical changes, ensuring the sustainable development of territory and GD initiatives. The purpose is to assess which interest groups are the primary beneficiaries or losers under the EU’s GD policy for building energy performance, and how LGs balance these interests locally. Naturally, with limited resources, any action that benefits certain interest groups may create unequal conditions for others. This study briefly analyzes several dilemmas and risks for municipalities implementing this policy:

The EU’s initial GD plans have been hampered by the Russian war in Ukraine, prompting a reevaluation of priorities. Northeast European countries bordering Russia, faces an increasing security threats. With limited budgets already stretched by education, social programs, and other mandatory functions prescribed by normative acts, LGs must choose between both new challenges – resilience to various security threats and building energy efficiency programs.

Building energy performance increasingly is increasingly associated not only with phasing out fossil primary resources, but also with limiting biomass use. Renewable woody biomass has been economically beneficial both in one- or two-apartment buildings, and in district heating (DH) systems, reducing heating costs. However, the new EU standards [

6] require costly restructuring to reduce use of woody biomass in favor of emission-free technologies, with insufficient funding currently available.

EU resources will be inadequate to fully address household energy poverty. LGs face a real dilemma: should they prioritize maximum possible socioeconomic development to reduce future poverty or redirect municipal resources towards immediate renovation of energy-poor households, potentially delaying socioeconomic development activities in the administrative territory.

Tension is emerging between DH customers and individuals or local energy communities who seek to optimize their own heating costs. While beneficial for some households, this would increase network costs for others. LGs must balance the benefits to individuals and energy communities against the need for equitable service pricing for all networked customers.

Transport is Latvia's largest source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Although municipalities are not involved in regulating air transport and shipping, they share responsibility for road transport with the state and the private sector. Linking building energy performance with the development of electric mobility presents a significant challenge for LGs’ budgets.

Success in improving building energy performance depends on the choice between two public management approaches at the municipal level: outsourcing versus re-municipalisation [

17], and between immediate partial compensation for those adversely affected and explaining long-term benefits without compensation [

18,

19].

The novelty of this research lies in applying Rational Choice Theory and methods of balancing group interests to enhance building energy performance, weighing the benefits for supporting groups against the losses for opponents.

2. Materials and Methods

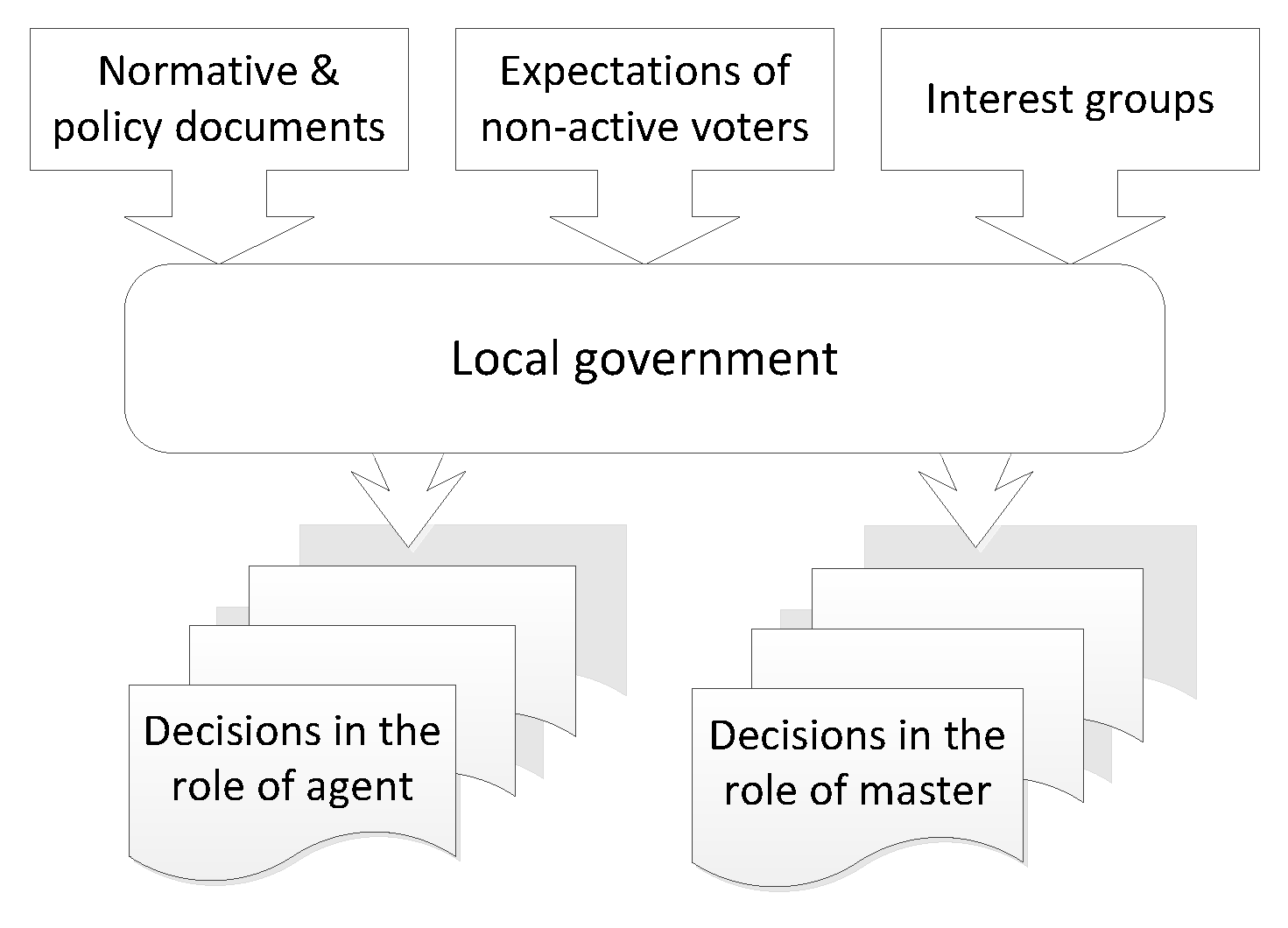

LGs operate to benefit their residents both autonomously (as masters) and in delegated capacities (as agents). The dual nature of municipalities is illustrated in

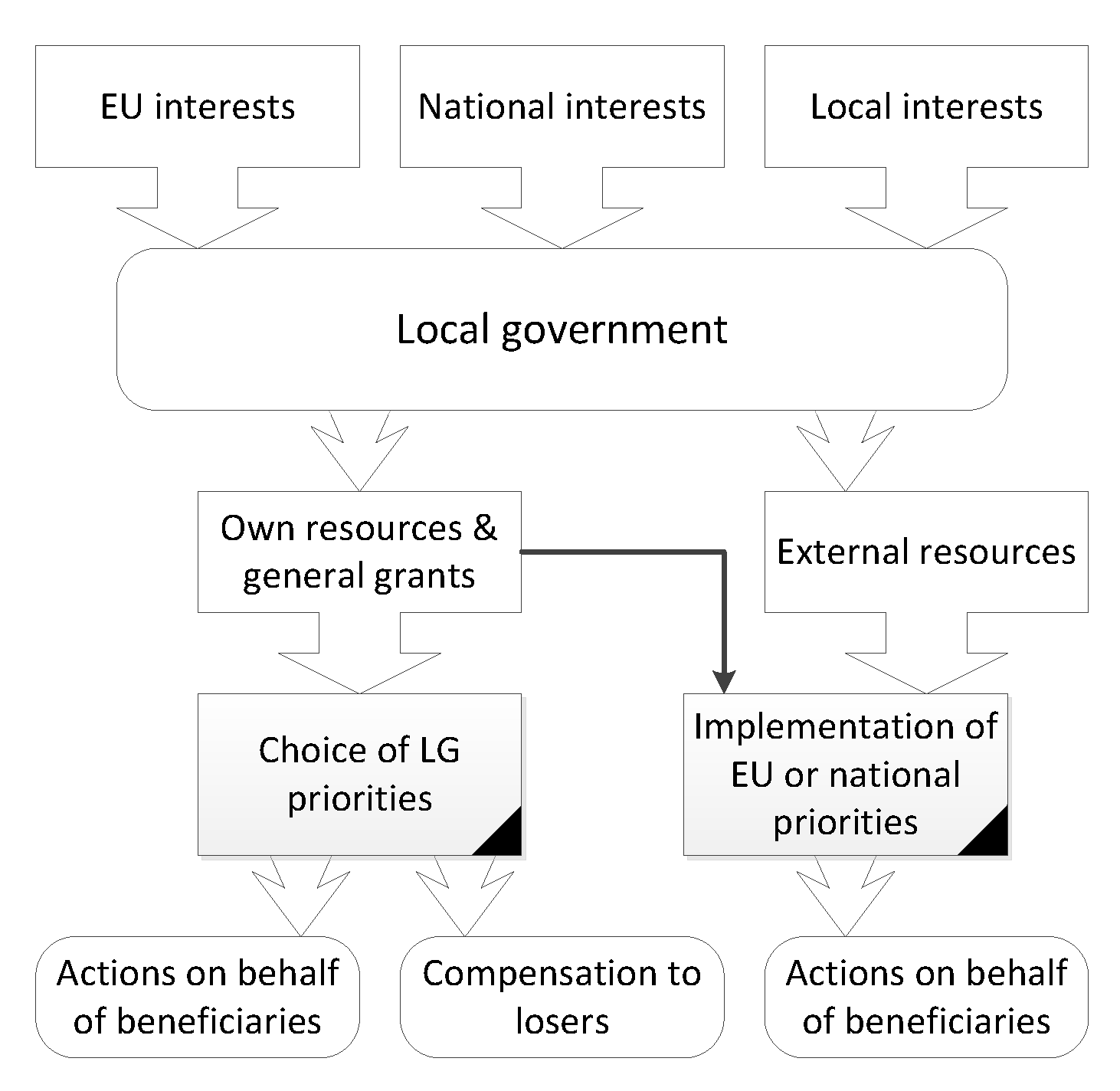

Figure 1. In both roles, municipalities are bound by EU and national regulations and policy documents; however, in areas of autonomous competence, locally adopted regulations also apply. Local priorities are shaped by EU, national, and local interests, many of which conflict (

Figure 2). The views of active members of organized civil society are considered in dialogues with interest groups and influence municipal actions’ policy documents. The expectations of less active citizens are also decisive, because in public communication (e.g. in social media) they can speak out against trends that do not correspond to their wishes.

In LGs’ role as masters, they must weigh benefits against losses. Limited funding means that LGs must make choices, which create both winners and losers, making municipalities responsible for actions that benefit somebody, while asking proportional compensation to those disadvantaged.

In matters of delegated authority, LGs have minimal flexibility, with only national policy documents being binding [

3]. For instance, municipalities generally support climate policy initiatives funded by the EU or national resources, as these actions increase local employment and welfare in the short term. However, if substantial local resources are required, LGs undertake more thorough evaluations. Misconceptions and stereotypes within the population, which can provoke resistance, are also frequent obstacles.

LG's degree of autonomy depends on the amount of finances in its revenues (in Latvia percentage of personal income tax and real estate tax, a general grant from the LG equalization fund, and several minor sources), that has remained after the performance of mandatory functions in the quality specified by law [

20,

21]. After allocation to mandatory services, finances may be used for discretionary functions not prohibited by law, including support for EU-driven GD activities.

Variations in per capita revenue among municipalities lead to different levels of voluntary LG initiatives compared to mandates regulated by national primary and secondary legislation. Currently, Latvia has 1,700+ consolidated national primary laws (not including amendments) and 4,500+ Cabinet of Ministers Regulations (secondary legislation) [

22]. Approximately 40-45% of these normative acts contain provisions binding on municipalities.

When balancing competing group preferences, LGs clarify key interests, their relation to energy performance measures, and expected outcomes relative to expectations. Municipal actions and decisions are based on these assessments.

Assumptions about group interests are based on the Rational Choice Theory [

23]. Each group member’s priorities contribute to the group’s collective opinion. Rational choice may align with altruism, where individuals willingly accept short-term sacrifices to advance global climate goals; it is not identical to self-interest. Group’s position emerges through a complex interplay of calculations and ideology.

The publicly available records of the Cabinet of Ministers' discussions on national draft laws (including those that transpose EU directives) were analyzed to understand the influence of organized civil society. In this study, reactions to the drafts of Climate Law [

24] and Transport Energy Law [

25] were assessed. Reviews and opinions submitted during these discussions by ministries, public agencies, business associations, trade unions, municipal associations, and individual activists (such as entrepreneurs and environmental advocates) collectively represent the stance of organized civil society on GD initiatives.

The nature of interests expressed in these reviews and opinions is summarized in

Table 1. Opinions are divided into two categories: those rooted in material interests of the group (e.g., commercial gains, preserving level of prosperity achieved) and those based on belief or skepticism regarding GD ideology or methods.

As shown, interest groups participating in national discussions primarily focus on leveraging GD measures to serve their material interests, such as gaining support for their businesses or households. It is reasonable to assume that this "homo economicus" model also applies at the local level. Values-based actions, ideological reasons only matter to climate activists and organizations.

LGs face serious dilemmas to make adequate decisions; short- and medium-term popular decisions made by municipalities often lead to a loss of competitiveness with other municipalities over the long term. The research analyzes a series of dilemmas, for each of them the interests, which unite supporters and detractors groups, are identified. Each dilemma is analyzed according to requirements set by EU normative acts under the "Fit for 55" framework. Key beneficiaries and affected parties are assessed qualitatively to identify apparent economic or social impacts.

3. Results

3.1. Dilemma: Resilience Against the Security Threats vs "Energy Efficiency First”

The revised Energy Efficiency Directive [

4] introduced a legal basis for the “energy efficiency first” principle, making it a binding obligation for EU Member States. The principle must be integrated into National Climate and Energy Plans, with performance regularly reported. Related issues such as territorial planning (including construction and operational considerations), centralized heat supply, and assistance to vulnerable populations (like support with housing maintenance) are designated as autonomous competences of LGs.

Russian war in Ukraine has drastically shifted the geopolitical landscape since 2022, creating a potential military threat to EU and NATO Member States. In particular, Northeast European countries bordering Russia, including Latvia, face new security challenges. Many European countries have prioritized strengthening their defence capabilities. However, researchers examining the impact of the war in Ukraine on LG actions often focus narrowly on reducing the overall EU’s energy dependence on Russian oil and gas. Ukraine’s experience shows that in the event of military conflict any municipality could become a direct target of missile and drone strikes, which challenges the civil protection system to ensure residents’ security and maintain operations even if energy infrastructure is damaged. Civil protection, as part of the national security system, became an autonomous responsibility of Latvian municipalities in 2021.

In 2024, the Latvian Cabinet of Ministers set the strengthening of defence capabilities and security as the only development and funding priority for the next three years [

26]. Higher geopolitical risks are expected to reduce investments and increase economic risks (such as stagnation and stagflation). Consequently, LGs face constrained resources, limiting their ability to maintain accustomed services for citizens and raising the issue of prioritization. Among other responsibilities, this dilemma includes two new and costly but essential functions: protecting residents during potential military conflict (e.g., building shelters, safeguarding energy networks) and fulfilling obligations to combat climate change. Local interest groups’ perspectives play a significant role in LG decision-making (

Table 2).

The interest in maximum security in the event of a military conflict is an extremely important factor for everyone. Families and organizations expect decisive actions from LGs if hostilities spread. However, part of the community rely on NATO membership as a deterrent, believing that Russia will not initiate a military conflict with NATO Member States, and thus prioritize energy efficiency over civil protection. This split in priorities reveals substantial risks for LGs, regardless of the path chosen.

3.2. Dilemma: Preserving Woody Biomass as a Primary Resource for Heat Supply vs Abandoning It

Between 2000 and 2022, woodfuel production in Europe grew by 68%, with wood pellet production doubling since 2012. This expansion has spurred the EU to reconsider support for biomass as a primary energy source. Amendments to the Directive on Renewable Energy Resources [

6] introduced the principle of cascading use of woody biomass, recommending low priority for combustion. Member States should provide that the threshold for biomass combustion plant capacity, beyond which biomass ceases to qualify as a renewable resource, is to be lowered from 20 MW to 7 MW.

Woody biomass is counted as a renewable resource under the Kyoto Protocol [

27] in Latvia. Wood pellet production doubled in 2023 compared to 2012, with wood chip production tripling. Over the past 20 years, LGs have supported gradual transition from natural gas to wood chips for DH to reduce usage of fossil primary energy sources. Woody biomass accounted for 25% of overall wood uses in 2022, remaining the main heat resource for individual buildings. However, the use of woody biomass now faces scrutiny, with an indefinite transitional period from fossil to renewable resources.

The Directive [

6] permits Member States to derogate from the principle of the cascading use of biomass, where needed to ensure security of energy supply. Accordingly, the draft of the National Energy and Climate Plan [

28] envisages a long term reduction in solid biomass use and introduction of the principle of cascading in the usage of timber after 2030-2040. The Plan includes transitioning existing solid biomass plants with installed thermal power >7.5 MW to emission-free technologies; electricity currently appears the most feasible primary resource alternative. Ministry of Climate and Energy, the Public Utilities Commission, the Heat Companies Association and power supply company "Sadales tīkls" have concluded a memorandum [

29] to coordinate the electrification of the DH sector, development of the power and heat supply infrastructure, reducing the costs of heat supply.

In Latvia, many residents, especially seniors in rural areas favour maintaining inexpensive heat via woody biomass combusting in both DH and local heat sources, and see little value in even a slow, gradual switch to alternative primary energy resources (

Table 3). Replacing woody biomass with electricity as a primary energy resource would lead even to a higher overall GHG emissions if fossil energy resources will be partially used for power generation for years. LGs and local entrepreneurs are interested in lower formally calculated level of GHG emissions, because fully green electricity could be unacceptable by its high cost. Heat producers and households may prefer to retain woody biomass as a green primary energy source for as long as possible.

Higher-income households and entrepreneurs may prioritize reducing local pollution near their households, favoring a shift to electricity. Individuals and energy communities, generating wind or solar energy, may support this transition. Directives [

4,

6] urge Member States to encourage such individual and community initiatives.

The risk of delaying woody biomass phase-out is related to the threat of rapid introduction of emission trading and sanctions for heat producers. The risk of orientation to electricity in short term is related to unforeseen increases of green electricity costs. Balancing interests must be done under conditions of high uncertainty.

3.3. Dilemma: Fighting Energy Poverty Now vs Promoting Productive Employment

One of the GD key problems is how to transform the slogan "no one will be left behind" into reality. There are two approaches to this: providing energy allowances to low-income households now, or promoting high-value-added manufacturing and knowledge-based service providing in the municipality, creating good jobs, which will eliminate energy poverty for the long term. Both financial and legal challenges complicate this decision for the municipality.

Addressing energy poverty, particularly within the context of building renovations, is inseparable from the interests of all household types. Households experiencing energy poverty (about 10% of households in apartment buildings) are integrated into mixed-income communities. Even if funding is available to support energy-poor households in renovation projects, gaining consent from the other apartment owners could prove challenging.

Draft of the National Climate and Energy Plan [

28] aims to renovate less than 10% of apartment buildings by 2030. According to renovation cost estimates, which are provided by the Ministry of Economy [

30], only a small portion of the required investment is earmarked in upcoming budgets, leaving many buildings underfunded. If EU programs or national funds are used to combat energy poverty, other apartment owners may face pressure to take out bank loans. For households that make rational financial decisions, the benefits of reduced energy consumption should exceed the annual loan payments. Assuming a 10-year loan payback period at current DH tariffs, heat energy consumption would need to decrease by at least 60 kWh/m² per year to be financially viable. Achieving this substantial reduction would require deep renovations, for which cost forecasts may be underestimated, potentially discouraging households from taking on long-term loans.

The Ministry of Economy has proposed a legislative amendment [

31] that would prevent the majority of apartment owners from blocking renovation efforts desired by an active minority. This amendment would allow as few as 17% of households to initiate renovations on behalf of the entire building community. Under this scenario, energy-poor households, who are neither able nor willing to cover higher heating costs or take on renovation loans, would be the main beneficiaries. However, the majority of apartment owners are unlikely to support this approach; instead, they may prefer allocation of funding for all types of indirect support to businesses and sectors with high growth potential and high-value-added products (

Table 4). Moreover, discussions within the Parliamentary Commission have revealed that banks would likely not approve loans based solely on the consent of 17% of apartment owners.

In considering this dilemma through the lens of rational choice theory, both the material gains and losses of each group, as well as their beliefs and values, must be weighed. The proportion of households experiencing energy poverty varies significantly between municipalities. In Latvian social policy a strong emphasis has consistently been placed on reducing inequality. The primary risk of focusing on energy poverty is that it may inadvertently encourage households, which are not classified as poor, to seek similar benefits. Conversely, prioritizing productive employment could conflict with legislative restrictions on addressing inequality. Municipal leaders must therefore carefully evaluate public sentiment, balancing the use of local government funds for long-term economic growth and future benefits against short-term material support to reduce inequality today.

3.4. Dilemma: Energy Efficiency for Individuals or Community vs the Interests of All DH Users

GD regulatory framework aim to balance in sustainable development planning centralized and decentralized heating, supporting both efficient DH systems and independent, individualized heating solutions. Individualized approaches foster innovation and can be tested on a smaller scale, potentially providing successful examples for municipal companies and private households to follow.

The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive [

5] mandates the inclusion of measures in renovation projects that prioritize "energy efficiency first" at the individual household level, minimizing reliance on the DH network. These measures include:

local heat generation using solar and wind energy;

use of heat pumps;

separate heating energy management systems for each household;

transition to a lower temperature for the heat carrier.

Both the Energy Efficiency Directive [

4] and the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive [

5] encourage the formation of energy communities that pursue autonomous energy sources, including independent heating solutions. However, such scenarios conflict with the shared interests of DH system users. Lower overall heat consumption does not reduce heat losses in the DH pipeline system, meaning that reduced usage raises heat loss costs per unit of consumed heat (see

Table 5). Additionally, lowering the temperature of the heat carrier can increase the risk of Legionnaires' disease.

Latvian local governments have prior experience [

32,

33] with integrating individual solutions within the DH framework. Individual solutions should continue to be seen as complementary activities, while retrofitting DH systems remains the most cost-effective path toward decarbonization [

34,

35].

However, as autonomous systems develop, the efficiency risks (e.g., in terms of upgrades and costs) to DH systems increase. The ability to effectively integrate individual or community heating solutions depends on accurately anticipating and managing these risks.

3.5. Dilemma: Transport Electrification vs Efficient Urban Heating System

Transport is the largest source of GHG emissions in Latvia. While air and sea transport are beyond municipal control, road transport responsibility is shared by the state, municipalities, and the private sector. The draft of National Climate and Energy Plan envisions limited support for municipalities in transitioning to electric transport, with several local initiatives planned, including:

construction of slow charging points (including for e-bikes and e-scooters) near apartment buildings, public buildings, parking lots, etc.;

electric mobility support measures (e.g., use of public transport lanes, costless parking spaces);

development of micro-mobility infrastructure, such as bicycle paths and surveillance cameras in bicycle parking areas.

As part of the “Fit for 55” initiative, municipalities of large cities should become an example in development of electric mobility. These municipalities are required to ensure that at least 30% of energy used by public and municipal vehicles comes from electricity or renewable sources like hydrogen; in Latvia it is applied to 10 largest cities. These requirements mean increased demand for municipal activities and funding for GHG reduction in transport, potentially competing with investments needed for building heating system efficiency improvements (

Table 6).

The shift from fossil fuels to electricity for transport will require significant increases in electricity generation and demand. Various groups — including electric vehicle manufacturers, dealers, service providers, power producers, and energy prosumers—are advocating for this shift. However, transport electrification does not automatically reduce GHG emissions, as this depends on the composition of primary energy sources for power generation. Electric transport also faces vulnerabilities in crises (such as recent floods in the Czech Republic and Spain in 2024, or the military conflict in Ukraine), when power supply may be disrupted. The cost of green electricity adds further risk. Meanwhile, even moderate growth in electric transport could reduce demand for housing that lacks slow-charging options, even if those buildings have low heat consumption

If LGs actively support building renovations, which serve the interests of all residents by reducing heating costs and loan needs, DH providers may struggle to secure the necessary subsidies to shift to renewable primary energy sources, as these also require substantial investment. This creates a reasonable risk of incomplete retrofitting of urban heating systems.

The risks associated with this dilemma are significant. To balance interests, municipalities must consider whether more robust and cost-effective solutions for GHG reduction may be preferable.

3.6. Dilemma: Outsourcing vs Re-Municipalisation

Municipalities manage and promote the retrofitting of urban heating systems through various means: by planning the territory, issuing permits and establishing prohibitions, analyzing and explaining the profitability or shortcomings of projects, helping to choose the most profitable projects and choosing the best borrowing strategy and even performing various construction works. The last in principle can be completed either by a privately-owned enterprise or by a municipally owned enterprise, with public-private partnership as a possible alternative.

Retrofitting projects typically are outsourced to private businesses, which are motivated by profit and tend to focus on projects with sufficiently high profit margins. LGs generally support local private businesses, as this promotes regional development and increases tax revenues.

However, residents prioritize timely, affordable implementation of retrofitting projects with good construction quality. Cost overruns and delays are common issues with private construction companies, which create additional risk for meeting climate action requirements. By contrast, municipalities have more control over their own enterprises, allowing for direct management, projects’ coordination and intervention if necessary (see

Table 7). Ideological interest groups are already emerging, which are not convinced of the effectiveness and advantages of the private sector.

The substantial obstacle to optimal decision is the traditional approach to competition neutrality principle [

36]. Majority of legislators, scholars and administrators are convinced that the advantages, which the LGs potentially could provide to their owned enterprises (e.g., satisfaction with a low/zero profit margin or even financial support in the common interests of society), should be preventively combated. Not enough attention is paid to overregulation of the municipally owned enterprises, equating the regulation of them with the requirements to the public administration and so reducing their performance.

A study of motivation behind ongoing re-municipalisation since 2000 in 56 countries [

37] shows emerging “basic trends for why re-municipalisation is happening” – business issues (cost reduction and quality of service provision) are the dominant reason “to bring more sectors and activities into public ownership”. Currently the authors found the trend as particularly strong in the sectors of energy, water, telecoms and health, which were actively privatized in the last decades. They recommend opening “critical policy debates about how local and municipal governments around the world and across a diverse range of sectors are returning to forms of public ownership to deliver more effective and equitable local public services”. Given the critical role of urban heating systems’ efficiency for achieving the GD goals, the re-municipalisation of related construction works could be included in the “Fit for 55” framework.

Municipalities must also consider the increasing likelihood of natural disasters and geopolitical instability. To reduce the impact of such crises, municipalities should carefully plan the retrofitting program of the urban heating system and monitor its implementation, paying great attention to contingency planning issues. For sustainable regional development, LGs must balance these conflicting options effectively.

4. Discussion

Citizens of EU Member States have collectively voiced their support for global GD policies, during European Parliament elections [

38], including enhancing the energy performance of buildings. In fact, the previous parliamentary term demonstrated an even more radical stance on certain GD settings than the European Commission’s proposals. The issue at hand involves reconciling the priorities of local communities at the municipal level with global goals, as well as examining the popularity of views such as, “wind power generators are essential, just not in my backyard”.

Local issues often diverge from international agendas, and in these cases, LGs must employ diplomatic skills to adapt EU and national legislation to local contexts. This primarily concerns LGs in their capacity as regulatory agents, and is not so important in cases of voluntary initiatives.

Rational decision-making in this context means summing up the expectations of individuals. These individuals anticipate both improvements in the EU’s overall situation (relative to other regions and countries, such as, e.g., Southeast Asia, China, India, Brazil, and Japan) and progress in the sustainable development of their own local areas compared to neighboring municipalities. This study underscores the challenging dilemmas faced by LGs, as differing perspectives among interest groups lead to varied understandings of the goals, direction, and priorities of sustainable development. The success of LGs depends on their ability to address these dilemmas by balancing expectations across diverse interest groups.

The Energy Efficiency [

4] and Building Energy Performance [

5] directives call for immediate and specific actions to be implemented at national and municipal levels, though without providing funding from the EU or the national budgets for these initiatives. Municipalities currently lack, and will continue to lack the resources to meet these requirements in full. However, if LGs could focus on gradual implementing these policies within their operational scope, and align them with other priorities important to the local community, the outcomes would be much more tangible and impactful.

Each dilemma involves practical considerations of both sides, and the ideal balance varies from one administrative area to another. As shown in the analysis, every public management decision produces both winners and losers. Providing compensation for those adversely affected can be seen as an ethical principle within organizations. The Kaldor-Hicks compensation principle, for example, suggests that while direct compensation may be provided to those who lose out, "theoretical compensation" could also flow from winners to losers in certain scenarios [

39,

40,

41].

5. Conclusions

- 1.

-

Achieving the GD goals, which relate to the energy performance of buildings and urban heating systems, largely depends on the decisions made by owners of buildings and DH systems — households, businesses, and municipalities. LGs’ voluntary initiatives will significantly influence these owners' choices regarding retrofitting buildings and infrastructure. Various local resident groups support also alternative approaches to the essential EU standards for building energy performance, tailored to local priorities. In some cases, these priorities even shift from complementary to fully alternative solutions:

prioritization of municipal resources for security of population in the event of military or other crises rather than for initiatives to enhance building energy efficiency;

continuation of the use of woody biomass for buildings’ heating, while planning gradual electrification of heating systems as green electricity prices decrease to affordable ones;

focus on promotion of productive entrepreneurship and the gradual reduction of energy poverty as household incomes rise;

maintenance of a uniform approach to all municipal residents in DH development, when supporting individual or community energy solutions;

concentration of municipal resources on improving the thermal efficiency of buildings in the interests of all residents, minimizing immediate public support measures for electric mobility, until green electricity prices decrease to an adequate level.

conduction of partial re-municipalisation of building renovation work to reduce the outsourcing monopoly.

- 2.

To implement the energy efficiency measures outlined in the “Fit for 55” legislative package, municipalities require appropriate co-financing through national fiscal policies. Decentralized funding would enhance decision-making and implementation at the local level.

- 3.

Since every initiative aimed at building energy performance creates both beneficiaries and those adversely affected, LGs need resources to compensate those impacted in the short and medium term. Potential long-term gains alone may not be sufficient to ensure social and economic stability.

- 4.

To balance the interests of various local resident groups, LGs must carefully evaluate relevant risks, particularly under conditions of high uncertainty.

- 5.

Recommendation for national governments: development of institutional and regulatory platform that brings together all stakeholders — including national governments, LGs, businesses, and residents — to collaboratively assess, plan, implement, and monitor GD progress. This approach would enhance activities’ coordination, mutual consultations, and joint decision-making.

- 6.

Recommendation for LGs: strengthening cooperation with private-sector interest groups by providing guidance, fostering collaboration, and making balanced decisions on buildings’ energy performance and other GD-related matters

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.; methodology, M.P. and E.K.; software, E.D.; validation, M.P. and J.B.; formal analysis, S.G.; investigation, U.S.; resources, G.K.; data curation, E.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, E.K.; visualization, J.B.; project administration, G.K.; funding acquisition, E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UNFCCC. Paris Agreement. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Pukis, M.; Bicevskis, J.; Gendelis, S.; Karnitis, E.; Karnitis, G.; Eihmanis, A.; Sarma, U. Role of Local Governments in Green Deal Multilevel Governance: The Energy Context. Energies 2023, 16(12), 4759. [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. European Charter of Local Self Government, Treaties No.122; Strasbourg, France, 1985. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/impact-convention-human-rights/european-charter-of-local-self-government#/ (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- EU (2023/1791). Directive of 13 September 2023 on energy efficiency and amending Regulation (EU) 2023/955. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2023/1791/oj (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- EU (2024/1275). Directive of 24 April 2024 on the energy performance of buildings. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1275/oj (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- EU(2023/2413). Directive of 18 October 2023 amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001, Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 and Directive 98/70/EC as regards the promotion of energy from renewable sources, and repealing Council Directive (EU) 2015/652. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2023/2413/oj (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Truijens, D.; Hanegraaff, M. It ain’t over ‘til it’s over: Interest-group influence in policy implementation. Political Studies Review, 2024, 22(2), pp. 387-401. [CrossRef]

- Hagen, A. ; Altamirano-Cabrera, J.C. ; Weikard, H.P. National political pressure groups and the stability of international environmental agreements. Int Environ Agreements 2021, 21, pp. 405–425. [CrossRef]

- Anger, N.; Asane-Otoo, E.; Böhringer, C.; Oberndorfer, U. Public interest versus interest groups: A political economy analysis of allowance allocation under the EU emissions trading scheme. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 2016, 16(5), 621–638. [CrossRef]

- Marchiori, C.; Dietz, S.; Tavoni, A. Domestic politics and the formation of international environmental agreements. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 2017, 81(1), pp. 115–131. [CrossRef]

- Marris, E. Why young climate activists have captured the world’s attention. Nature, 2019, 573(7775), pp. 471–472. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P. M.; Ocelík, P.; Gronow, A.; Ylä-Anttila, T.; Schmidt, L.; Delicado, A. Network ties, institutional roles and advocacy tactics: Exploring explanations for perceptions of influence in climate change policy networks. Social Networks, 2023. Vol. 75, pp. 78-87. [CrossRef]

- Cattino, M.; Reckien, D. Does public participation lead to more ambitious and transformative local climate change planning? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 2021, 52, pp. 100-110. [CrossRef]

- Bick, N. Citizen involvement in local sustainability policymaking: an in-depth analysis of staff activities and motivations. Sustain Science, 2024, September. [CrossRef]

- Pennacchioni, G. Harnessing Collective Intentionality for Climate Action: An Institutional Perspective on Sustainability, Topoi, 2024, August. [CrossRef]

- Peteri, G. Local Finances and the Green Transition Managing Emergencies and Boosting Local Investments for a Sustainable Recovery in CEMR Member Countries. 2022, CEMR. Available online: https://www.kdz.eu/sites/default/files/2022-11/CCE-Local%20finance%20UK%20v2-1.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Pukis, M. Local Dilemma about Liberalisation or Intervention. International Journal of Management Science and Business Administration, 2016, 2(10), pp. 17-24. [CrossRef]

- Hicks, J. The Foundations of Welfare Economics. The Economic Journal, 1939, 49(196), pp.606-712. JSTOR 2224835. [CrossRef]

- Kaldor, N. Welfare Propositions in Economics and Interpersonal Comparisions of Utility. The Economic Journal, 1939, 49(195), pp. 549-552. JSTOR 2224835 . [CrossRef]

- Saeima. Local Government Law, 2021. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/336956 (accessed on12 November 2024).

- Saeima . Law “On Local Government Budgets”, 1995. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/34703 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Data base of Latvian legislation. Available online: www.likumi.lv (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Herfeld, C. Revisiting the criticisms of rational choice theories, Philosophy Compass, 2021, 17(4). [CrossRef]

- Cabinet of Ministers. Likumprojekts Klimata likums, 2024, 21-TA-62, in Latvian. Available online: https://tapportals.mk.gov.lv/legal_acts/7987de45-93fd-45e3-ac4c-948251c622d9 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Cabinet of Ministers. Likumprojekts Transporta enerģijas likums, 2024, 23-TA-1451, in Latvian. Available online: https://tapportals.mk.gov.lv/legal_acts/042cde65-37a0-4e35-a005-109648ea5037 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Cabinet of Ministers. Informatīvais ziņojums "Par vidēja termiņa budžeta prioritārajiem attīstības virzieniem", 2024, 24-TA-1428, in Latvian. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/352968-ministru-kabineta-sedes-protokols (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- UNFCC. Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 1998. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpeng.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Ministry of Climate and Energetics. Latvijas nacionālais enerģētikas un klimata plāns 2021.-2030.gadam, projekts, in Latvian. Available online: https://www.kem.gov.lv/sites/kem/files/media_file/kemplans_nekp_08072024.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Ministry of Climate and Energetics. Memorandā vienojas veicināt centralizētās siltumapgādes jomas elektrifikāciju, 2024, in Latvian. Available online: https://www.kem.gov.lv/lv/jaunums/memoranda-vienojas-veicinat-centralizetas-siltumapgades-jomas-elektrifikaciju?utm_source=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Ministry of Economics. Ēku atjaunošanas ilgtermiņa stratēģija, Informatīvais ziņojums, 2020, in Latvian. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/342294-eku-atjaunosanas-ilgtermina-strategija (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Saeima. Law on Residential Properties, 2010. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/ne/ne/id/221382-law-on-residential-properties (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Balode, L.; Zlaugotne, B.; Gravelsins, A.; Svedovs, O.; Pakere, I.; Kirsanovs, V.; Blumberga, D. Carbon Neutrality in Municipalities: Balancing Individual and District Heating Renewable Energy Solutions. Sustainability, 2023, 15, 8415. [CrossRef]

- Balode, L.; Dolge, K.; Blumberga, D. The Contradictions between District and Individual Heating towards Green Deal Targets. Sustainability, 2021, 13, 3370. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T.; Ma, Y.; Rhodes, C. Individual Heating Systems vs. District Heating systems: What will Consumers Pay for Convenience? Energy Policy 2015, 86, pp. 73–81. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.H.; Harmsen, R.; Menkveld, M.; Faaij, A.; Kramer, G.J. Municipalities as key actors in the heat transition to decarbonise buildings: Experiences from local planning and implementation in a learning context. Energy policy, Vol. 169, October 2022, 113169. [CrossRef]

- Pukis M.; Vircavs I. Opportunity for Symmetric Approach to the Competition Neutrality – Case of Latvia. IEEE International Conference on Technology and Entrepreneurship, Kaunas 2023. Conference Proceedings, pp. 92-97. [CrossRef]

- Cumbers A.; Pearson B.; Stegemann L.; Paul F. Mapping Remunicipalisation: Emerging Trends in the Global De-privatization Process, Adam Smith Business School University of Glasgow, 2022. Available online: https://eprints.gla.ac.uk/272257/1/272257.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- EU. Consolidated version of the Treaty on the functioning of the European Union, 2007. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT:en:PDF (Accessed 12 November 2024).

- Mukoyama, T. In defence of the Kaldor-Hicks criterion, Economics Letters, 2023, 224, 111031. [CrossRef]

- Wight, J. B. The Ethics behind Efficiency. University of Richmond Economics Faculty Publications, 2017, 52. Available online: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/economics-faculty-publications/52 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Bostani, M.; Malekpoor, A. Critical Analysis of Kaldor-Hicks Efficiency Criterion, with Respect to Moral Values, Social Policy Making and Incoherence. Advances in Environmental Biology, 2012, 6(7), pp. 2032-2038. Available online: https://www.aensiweb.com/old/aeb/2012/2032-2038.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).