Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

15 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

2.2. Data Extraction From the FAERS Database

2.3. Data Handling, Analysis and Comparison to the LactMed Database

3. Results

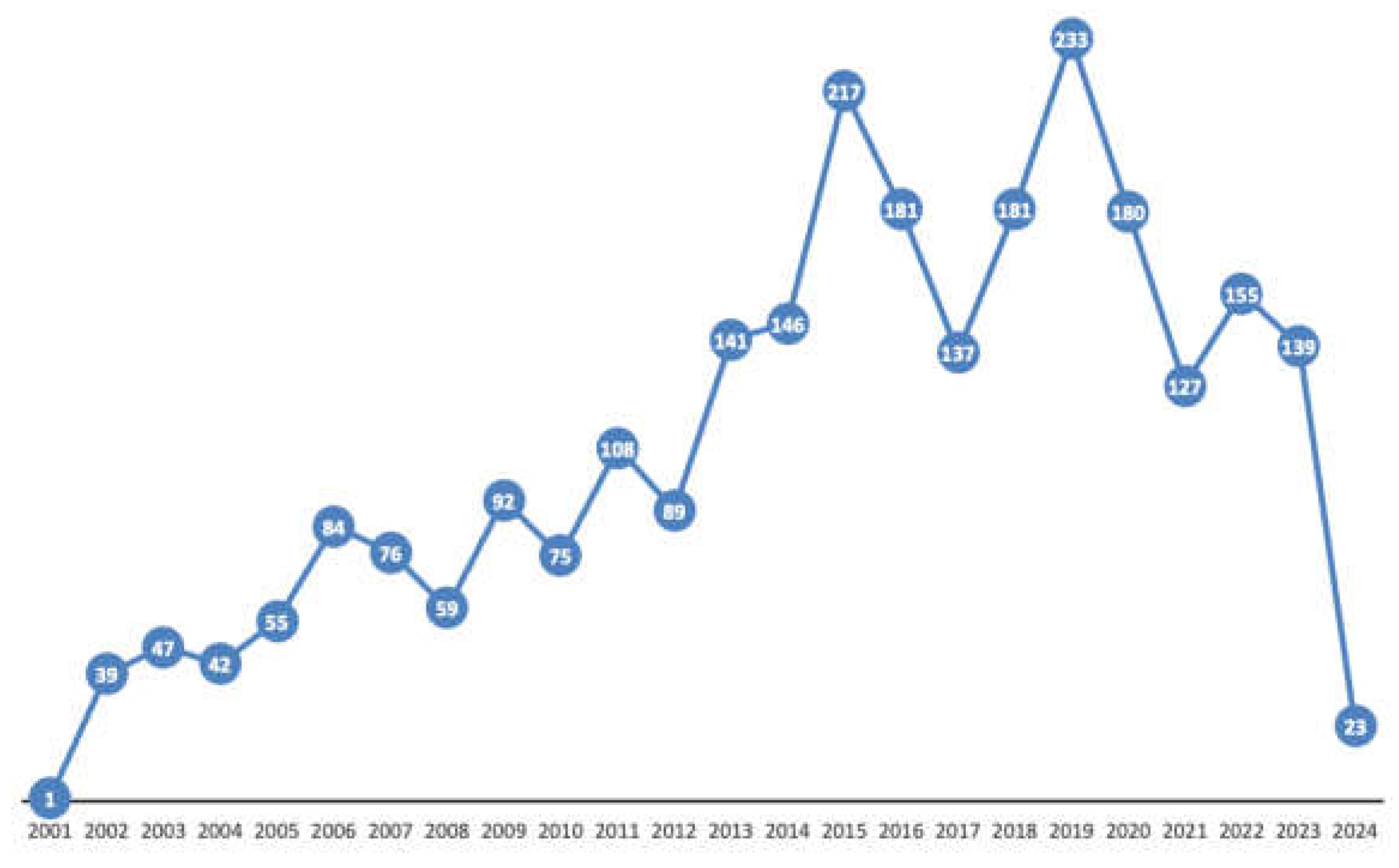

3.1. Number of Lactation-Related Adverse Events and Annual Trends

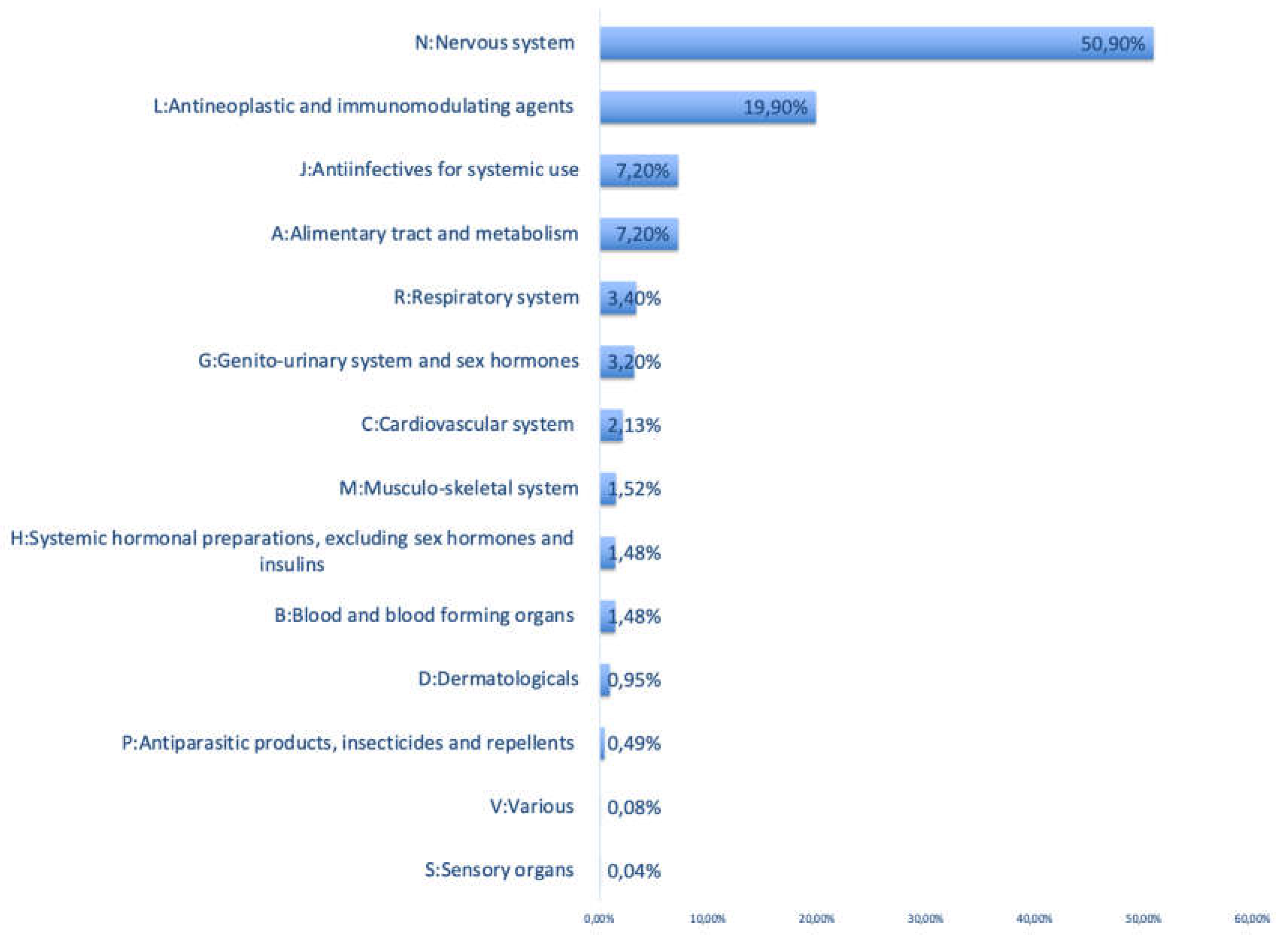

3.2. ATC Categories and Most Commonly Retrieved Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients

3.3. Comparison of the ADEs from the FAERS Database to the LactMed Database

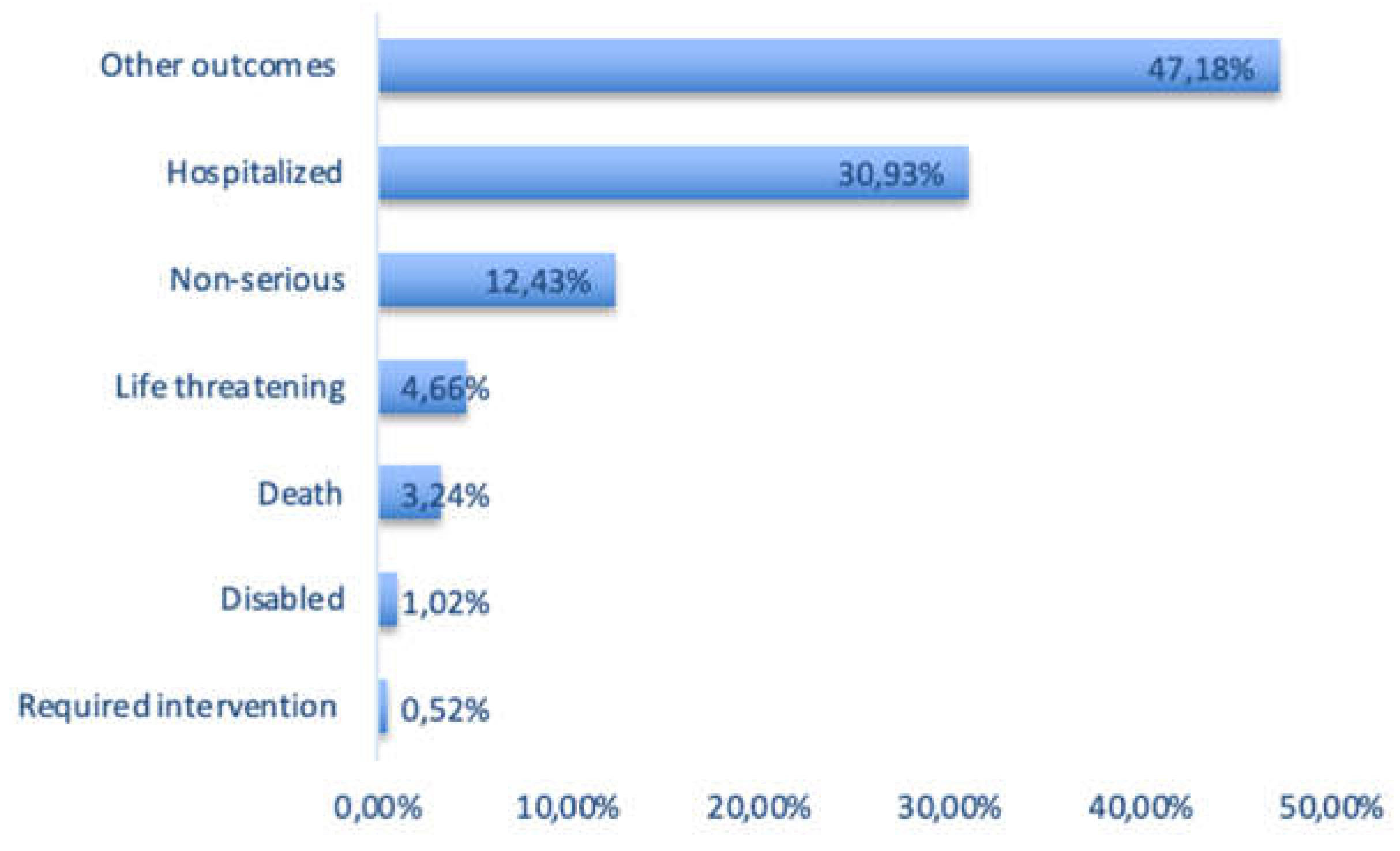

3.4. Outcome Categories of Lactation-Related ADEs in the FAERS Database

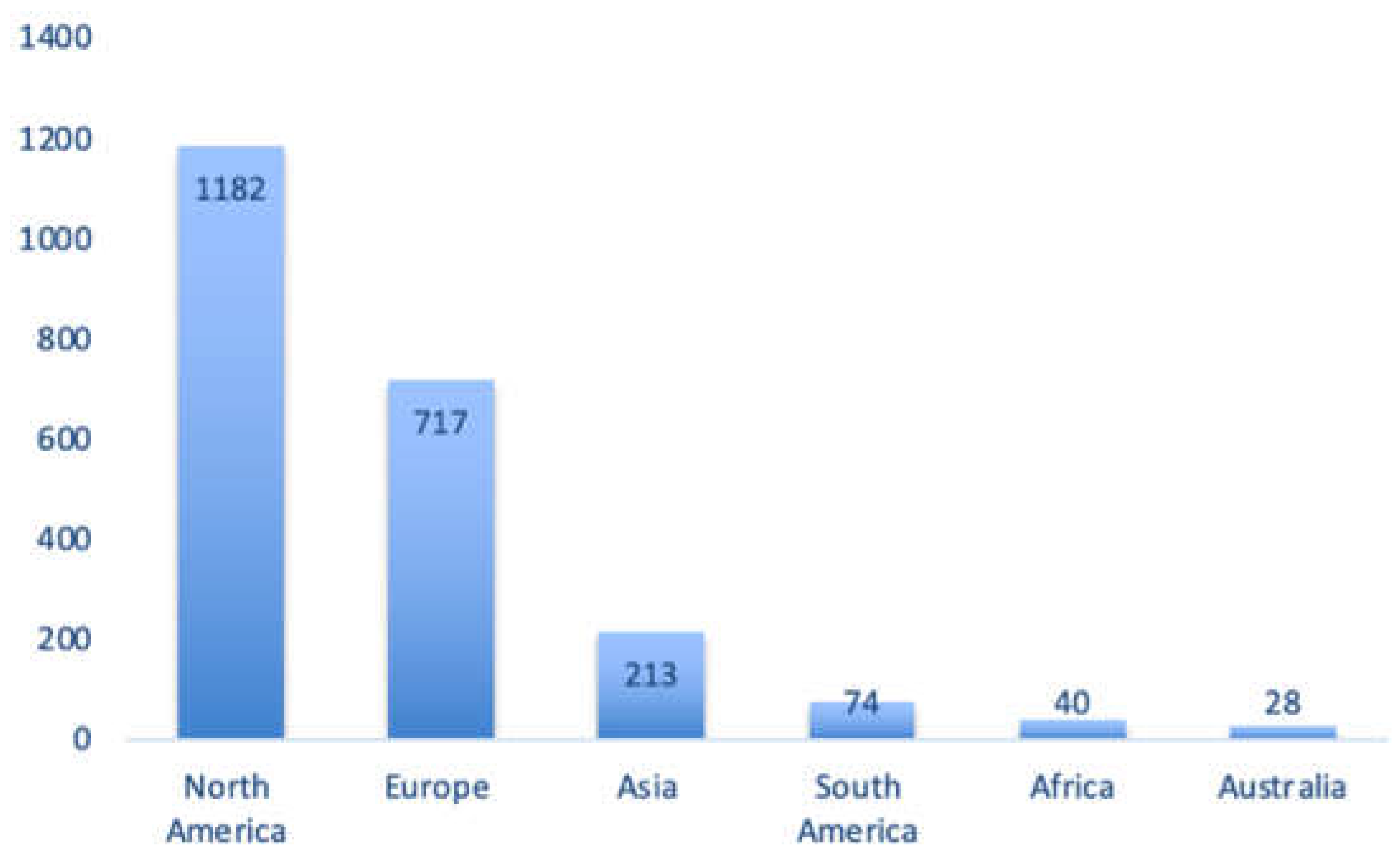

3.5. Regional Origin of the Lactation-Related Adverse Events Retrieved in the FAERS Database

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. New Methods for Future Strategies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gong, C.; Bertagnolli, L.N.; Boulton, D.W.; Coppola, P. A literature review of drug transport mechanisms during lactation. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meek, J.Y.; Noble, L.; Section on, B. Policy Statement: Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk. Pediatrics 2022, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masi, A.C.; Stewart, C.J. Role of breastfeeding in disease prevention. Microb Biotechnol 2024, 17, e14520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verstegen, R.H.J.; Anderson, P.O.; Ito, S. Infant drug exposure via breast milk. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2022, 88, 4311–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Johnson, T.; Sahin, L.; Tassinari, M.S.; Anderson, P.O.; Baker, T.E.; Bucci-Rechtweg, C.; Burckart, G.J.; Chambers, C.D.; Hale, T.W.; et al. Evaluation of the Safety of Drugs and Biological Products Used During Lactation: Workshop Summary. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2017, 101, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Saver, B.; Scanlan, J.M.; Gianutsos, L.P.; Bhakta, Y.; Walsh, J.; Plawman, A.; Sapienza, D.; Rudolf, V. Does Maternal Buprenorphine Dose Affect Severity or Incidence of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome? J Addict Med 2018, 12, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenup, A.J.; Tan, P.K.; Nguyen, V.; Glass, A.; Davison, S.; Chatterjee, U.; Holdaway, S.; Samarasinghe, D.; Jackson, K.; Locarnini, S.A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in pregnancy to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus. J Hepatol 2014, 61, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergeron, S.; Audousset, C.; Bourdon, G.; Garabedian, C.; Gautier, S. Elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor induced liver enzymes abnormalities in breastfed infants: A series of 3 cases. Therapie 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaiselvan, V.; Kumar, P.; Mishra, P.; Singh, G.N. System of adverse drug reactions reporting: What, where, how, and whom to report? Indian J Crit Care Med 2015, 19, 564–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Administration, U.S.F.a.D. FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Public Dashboard. 2024, 2024.

- Agency, E.M. EudraVigilance. 2024.

- Care, A.G.D.o.H.a.A. Database of Adverse Event Notifications (DAEN) - medicines. 2024.

- Development, B.M.N.I.o.C.H.a.H. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Ojo A, P.P., Boehning AP. Conversion Weights. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557608/ (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- UNICEF, W. Global Breastfeeding Scorecard 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/documents/global-breastfeeding-scorecard-2023#:~:text=For%202023%20the%20scorecard%20demonstrates,target%20of%2050%25%20by%202025 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Hotham, N.; Hotham, E. Drugs in breastfeeding. Aust Prescr 2015, 38, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A.A.A.; Rahim, R.; Teo, S.P. Pharmacovigilance and Its Importance for Primary Health Care Professionals. Korean J Fam Med 2022, 43, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kugener, V.F.; Freedland, E.S.; Maynard, K.I.; Aimer, O.; Webster, P.S.; Salas, M.; Gossell-Williams, M. Enhancing Pharmacovigilance from the US Experience: Current Practices and Future Opportunities. Drug Saf 2021, 44, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abduljalil, K.; Pansari, A.; Ning, J.; Jamei, M. Prediction of drug concentrations in milk during breastfeeding, integrating predictive algorithms within a physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 2021, 10, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P.O.; Pochop, S.L.; Manoguerra, A.S. Adverse drug reactions in breastfed infants: less than imagined. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2003, 42, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P.O.; Manoguerra, A.S.; Valdes, V. A Review of Adverse Reactions in Infants From Medications in Breastmilk. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2016, 55, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegaert, K.; van den Anker, J.N. Adverse drug reactions in neonates and infants: a population-tailored approach is needed. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015, 80, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro-Ramos, T.; Paley, C.; Pi-Sunyer, F.X.; Gallagher, D. Body composition during fetal development and infancy through the age of 5 years. Eur J Clin Nutr 2015, 69, 1279–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, A.; Ariano, A.; Triarico, S.; Capozza, M.A.; Ferrara, P.; Attina, G. Neonatal pharmacology and clinical implications. Drugs Context 2019, 8, 212608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food; Drug Administration, H.H.S. Content and format of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products; requirements for pregnancy and lactation labeling. Final rule. Fed Regist 2014, 79, 72063–72103.

- The European Medicines Agency. Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) Product- or Population-Specific Considerations III: Pregnant and breastfeeding women. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/post-authorisation/pharmacovigilance-post-authorisation/good-pharmacovigilance-practices-gvp (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Barrau, M.; Roblin, X.; Andromaque, L.; Rozieres, A.; Faure, M.; Paul, S.; Nancey, S. What Should We Know about Drug Levels and Therapeutic Drug Monitoring during Pregnancy and Breastfeeding in Inflammatory Bowel Disease under Biologic Therapy? J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franssen, E.J.; Meijs, V.; Ettaher, F.; Valerio, P.G.; Keessen, M.; Lameijer, W. Citalopram serum and milk levels in mother and infant during lactation. Ther Drug Monit 2006, 28, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulzen, M.; Schoretsanitis, G. [Psychopharmacotherapy during pregnancy and breastfeeding-Part II: focus on breastfeeding : Support options by using therapeutic drug monitoring]. Nervenarzt 2023, 94, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalcin, N.; van den Anker, J.; Samiee-Zafarghandy, S.; Allegaert, K. Drug related adverse event assessment in neonates in clinical trials and clinical care. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2024, 17, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; Lehr, V.T.; Lieh-Lai, M.; Koo, W.; Ward, R.M.; Rieder, M.J.; Van Den Anker, J.N.; Reeves, J.H.; Mathew, M.; Lulic-Botica, M.; et al. An algorithm to detect adverse drug reactions in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Clin Pharmacol 2013, 53, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leopoldino, R.W.D.; de Oliveira, L.V.S.; Fernandes, F.E.M.; de Lima Costa, H.T.M.; Vale, L.M.P.; Oliveira, A.G.; Martins, R.R. Causality assessment of adverse drug reactions in neonates: a comparative study between Naranjo’s algorithm and Du’s tool. Int J Clin Pharm 2023, 45, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, B.; Sharma, D.; Farahbakhsh, N. Assessment of sickness severity of illness in neonates: review of various neonatal illness scoring systems. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018, 31, 1373–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, N.; Kasikci, M.; Celik, H.T.; Allegaert, K.; Demirkan, K.; Yigit, S.; Yurdakok, M. An Artificial Intelligence Approach to Support Detection of Neonatal Adverse Drug Reactions Based on Severity and Probability Scores: A New Risk Score as Web-Tool. Children (Basel) 2022, 9, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauwelaerts, N.; Macente, J.; Deferm, N.; Bonan, R.H.; Huang, M.C.; Van Neste, M.; Bibi, D.; Badee, J.; Martins, F.S.; Smits, A.; Allegaert, K.; Bouillon, T.; Annaert, P. Generic workflow to predict medicine concentrations in human milk using physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modelling-A contribution from the ConcePTION project. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, N.D.; Smith, D.; Kinrade, S.A.; Sullivan, M.T.; Rayner, C.R.; Wesche, D.; Patel, K.; Rowland-Yeo, K. The use of quantitative clinical pharmacology approaches to support moxidectin dosing recommendations in lactation. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2024, 18, e0012351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauwelaerts, N.; Macente, J.; Deferm, N.; Bonan, R.H.; Huang, M.C.; Van Neste, M.; Bibi, D.; Badee, J.; Martins, F.S.; Smits, A.; et al. Generic Workflow to Predict Medicine Concentrations in Human Milk Using Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modelling-A Contribution from the ConcePTION Project. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katritzky, A.R.; Dobchev, D.A.; Hur, E.; Fara, D.C.; Karelson, M. QSAR treatment of drugs transfer into human breast milk. Bioorg Med Chem 2005, 13, 1623–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayaraghavan, S.; Lakshminarayanan, A.; Bhargava, N.; Ravichandran, J.; Vivek-Ananth, R.P.; Samal, A. Machine Learning Models for Prediction of Xenobiotic Chemicals with High Propensity to Transfer into Human Milk. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 13006–13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ATC Class | Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient | Percentage* |

|---|---|---|

| N: Nervous system | Buprenorphine | 16.00% |

| Lamotrigine | 14.20% | |

| Levetiracetam | 10.10% | |

| Acetaminophen | 9.63% | |

| Nicotine | 7.62 | |

| L: Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | Certolizumab pegol | 32.76% |

| Adalimumab | 19.62% | |

| Etanercept | 11.24% | |

| Infliximab | 10.48% | |

| Tacrolimus | 5.33% | |

| A: Alimentary tract and metabolism | Insulin | 50% |

| Omeprazole | 7.45% | |

| Ondansetron hydrochloride | 6.92% | |

| Mesalamine | 6.38% | |

| Metformin hydrochloride | 4.79% | |

| J: Antiinfectives for systemic use | Zanamivir | 17.55% |

| Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid | 13.30% | |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | 12.23% | |

| Lamivudine | 9.57% | |

| Emtricitabine\Tenofovir | 7.45% | |

| R: Respiratory system | Omalizumab | 24.72% |

| Cetirizine hydrochloride | 15.73% | |

| Fluticasone propionate/Salmeterol xinafoate | 13.48% | |

| Elexacaftor\Ivacaftor\Tezacaftor | 10.11% | |

| Budesonide | 7.87% |

| N: Nervous system | FAERS | LactMed® |

|---|---|---|

| Buprenorphine | Bradycardia Coma scale abnormal Drug withdrawal syndrome Neonatal Hypoglycemia Hypotension Irritability Lethargy Miosis Poor feeding infant Selective eating disorder Somnolence Sudden death |

Agitation Drowsiness Drug withdrawal Frequent yawning Hyperactive Moro reflex Insomnia Lower milk intake Lower weight gain Myoclonic jerks Opioid abstinence Poor feeding Pupillary dilation Sneezing Sweating Tremors |

| Lamotrigine | Abdominal pain Abnormal loss of weight Apathy Bradyarrhythmia Cyanosis neonatal Ecchymosis Eczema Failure to thrive Fatigue Feeding disorder Fluid intake reduced Hepatic enzyme increased Hyperbilirubinemia neonatal Hypotonia neonatal Hypovolemic shock Infantile apnea Irritability Jaundice Laryngomalacia Lethargy Liver disorder Malnutrition Nausea Neonatal hypoxia Neutropenia Normochromic normocytic Anemia Poor feeding infant Poor weight gain neonatal Rash Rash maculo-papular Rhinorrhea Selective eating disorder Skin discoloration Sleep disorder Somnolence Stridor Supraventricular Extrasystoles Thrombocytosis Urticaria Vomiting |

Anemia Apneic episode Drowsiness Drug withdrawal Elevated liver enzymes Elevated platelet counts Feeding problems Gangrene Gastrointestinal symptoms Heart murmur Hypotonia Icterus prolongatus Irritability Jaundice Liver damage Loss of appetite Neuromotor hyperexcitability Persistent crying Rash Retractive breathing Sedation Transient neutropenia Weight loss |

| Levetiracetam | Anemia neonatal Heart rate increased Infantile apnea Cyanosis neonatal Blood bilirubin increased Failure to thrive |

Drowsiness Hypotonia Poor feeding infant Poor weight gain Sedation Vomiting Weight loss Withdrawal seizures |

| Acetaminophen | Abdominal distension Acute hepatic failure Asthma Blood pressure abnormal Capillary nail refill test abnormal Coagulopathy Crying Drug-induced liver injury Erythema Gastrointestinal hemorrhage Hemoglobin decreased Heart rate increased Hepatomegaly Hypoglycemia Irritability Jaundice Livedo reticularis Metabolic acidosis Poor feeding infant Pulse abnormal Pyrexia Respiratory distress Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis Selective eating disorder Shock Skin exfoliation Staphylococcal infection Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage Vomiting Wheezing |

Asthma Maculopapular rash on the upper trunk and face Wheezing |

| Nicotine | Dyspnea | Reduction in the heart rate Sudden infant death syndrome |

| L: Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | ||

| Certolizumab pegol | Agitation Fungal infection Hematochezia Hematoma Irritability Nervousness Rash Restlessness Selective eating disorder Tongue disorder Wound |

Candida infection Upper respiratory infection Vomiting |

| Adalimumab | Nasopharyngitis Irritability Intestinal hemorrhage Gastrointestinal disorder |

None reported |

| Etanercept | Blood bilirubin abnormal Blood glucose decreased Death Dermatitis atopic Diarrhea Disturbance in attention Dyslexia Enterocolitis Feeding intolerance Gastroesophageal reflux Disease Gross motor delay Hemoglobin decreased Jaundice neonatal Lung disorder Nasopharyngitis Pneumonia Rash macular Respiratory tract congestion Seborrheic dermatitis Selective eating disorder Viral infection Weight decreased Weight gain poor White blood cell count increased |

High-pitched crying Rash |

| Infliximab | Hematochezia Jaundice Lactose intolerance Lower respiratory tract infection Lymph gland infection Malaise Poor feeding infant Selective eating disorder |

None reported |

| Tacrolimus | Diarrhea Intraventricular hemorrhage neonatal Neonatal asphyxia Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome Pneumothorax |

None reported |

|

A: Alimentary tract and metabolism |

||

| Insulin | Gastroesophageal reflux disease Hematochezia Necrotizing colitis |

None reported |

| Omeprazole | Diarrhea Faeces discolored Zinc deficiency |

None reported |

| Ondansetron hydrochloride | Crying Insomnia Irritability Sluggishness |

None reported |

| Mesalamine | Abdominal pain upper Blood albumin abnormal Candida infection Colitis Diarrhea Hematochezia Hemoglobin abnormal Pyrexia White blood cell count increased |

Diarrhea Thrombocytosis Thrombosis |

| Metformin hydrochloride | Tremor | None reported |

|

J: Antiinfectives for systemic use |

||

| Zanamivir | Abnormal faeces Decreased appetite |

No information |

| Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid | Agitation Clostridium difficile colitis Conversion disorder Diarrhea Enterocolitis Eye swelling Gastrointestinal pain Hematochezia Oral candidiasis Pyrexia Rash maculo-papular Rectal hemorrhage Vomiting |

Constipation Diarrhea Elevated liver enzymes (AST and ALT) Generalized urticaria Rash Restlessness |

| Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate | Thrombocytopenia | Diarrhea |

| Lamivudine | Sudden infant death syndrome | Sudden infant death syndrome |

| Emtricitabine/Tenofovir | - | Diarrhea |

| R: Respiratory system | ||

| Omalizumab | Anemia Anaphylactic reaction Cough Decreased appetite Eczema Eye oedema Gastroesophageal reflux disease Nasopharyngitis Oral fungal infection Otitis externa Poor quality sleep Pyrexia Rash erythematous Seborrheic dermatitis Swelling face |

None reported |

| Fluticasone propionate/Salmeterol xinafoate | Middle insomnia Poor feeding infant |

None reported |

| Cetirizine hydrochloride | Abnormal faeces Cyanosis Floppy infant Lethargy Oxygen saturation decreased Rash Respiratory arrest Somnolence |

Bruising Colicky symptoms Constipation Drowsiness Fever Irritability Poor feeding Rash Refusing of the breast Sedation |

| Elexacaftor\Ivacaftor\Tezacaftor | Alanine aminotransferase increased Aspartate aminotransferase increased Bronchiolitis Hyperinsulinemia Hypoglycemia neonatal Jaundice neonatal Neonatal respiratory distress Pancreatic failure Sepsis neonatal Sweat test abnormal Transient tachypnoea of the newborn Viral infection |

Bilirubin abnormalities Liver enzyme abnormalities Low sweat chloride |

| Budesonide | Adrenocortical insufficiency neonatal Dermatitis Eczema Neutropenia |

None reported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).