Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

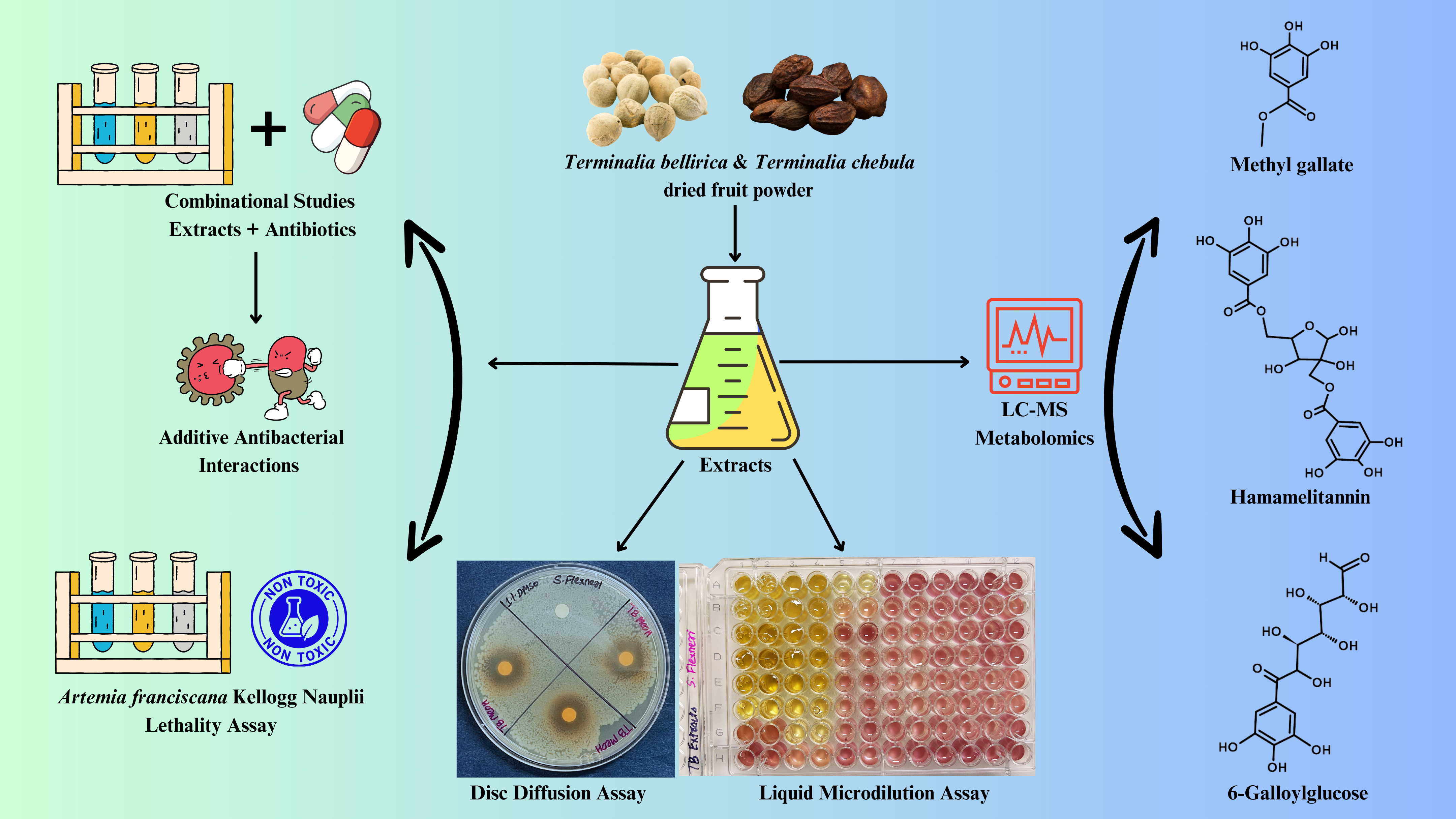

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sources of Plant Samples

2.2. Preparation of Extracts

2.3. Antibiotics and Bacterial Strains

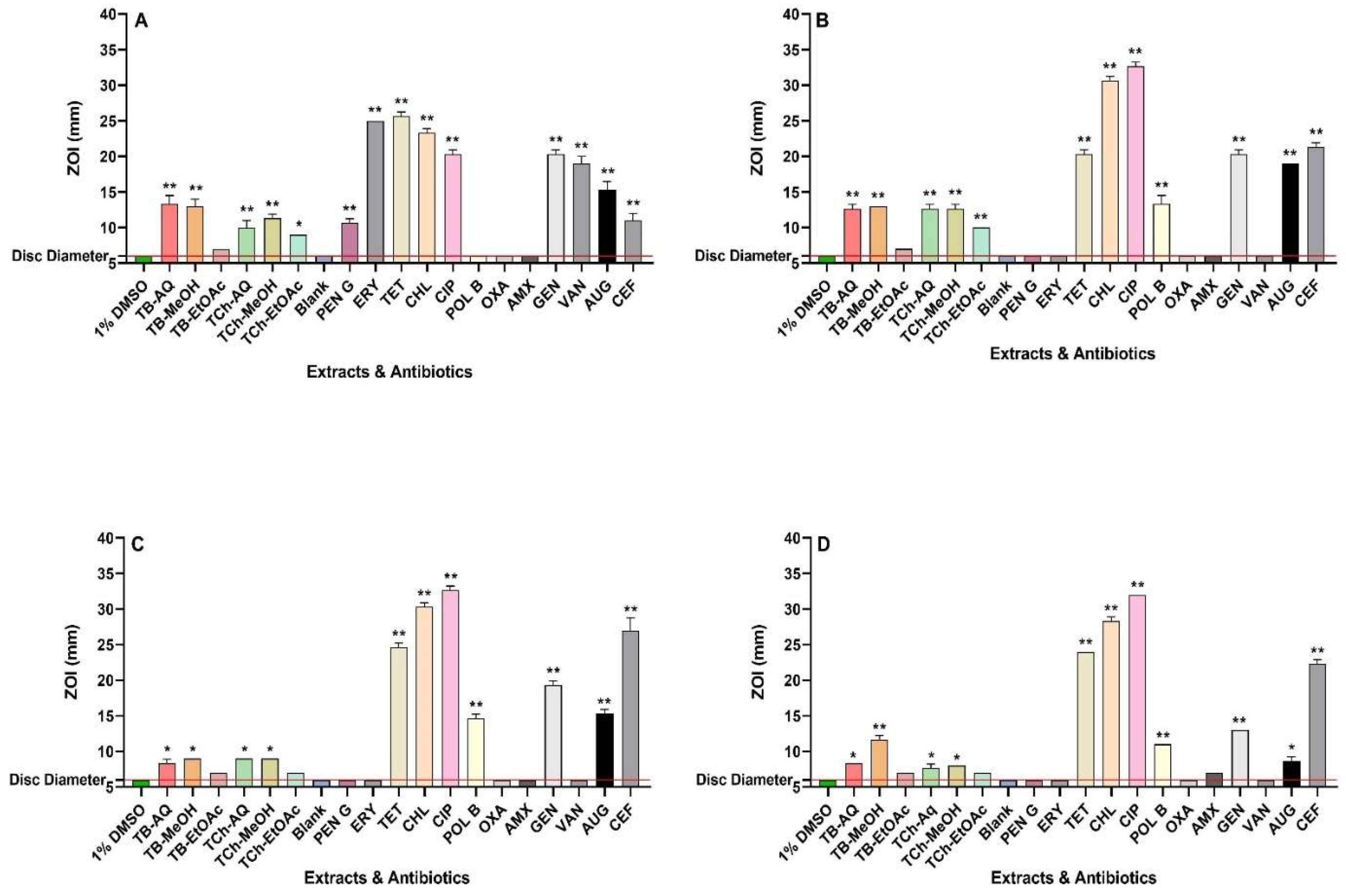

2.4. Antibacterial Susceptibility Screening

2.5. Minimum Inhibitory and Fractional Ihibitory Concentrations

2.7. Toxicity Assays

2.8. Non-Targeted Headspace LC-MS Workflow for Quantitative Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Antibacterial Assays

3.2. Combination Assays: Sum of Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (ƩFIC) Determinations

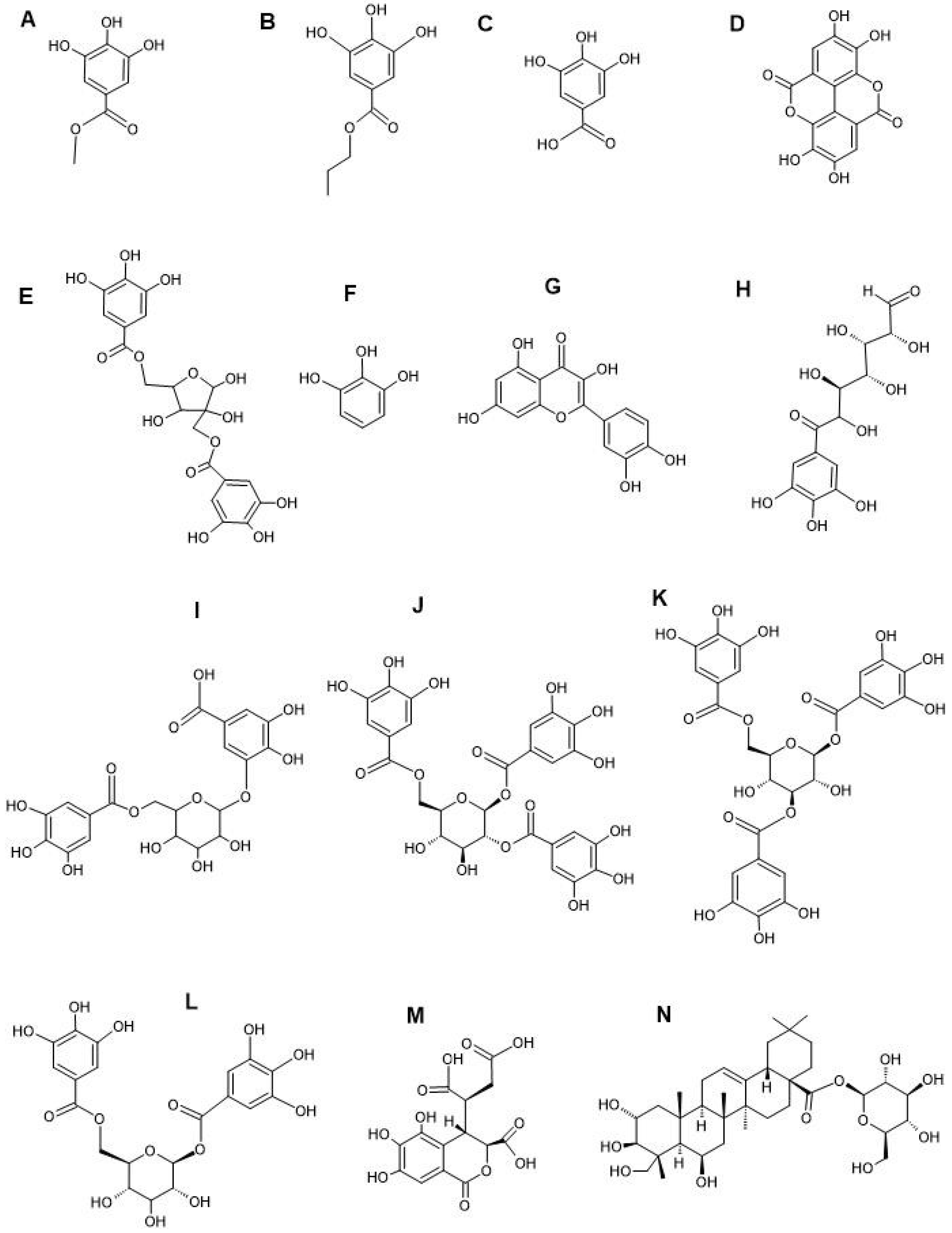

3.3. Compound Identification by LC-MS Metabolomics Profiling

3.4. Toxicity Quantification

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Diarrhoeal disease. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Troeger, C.; Blacker, B.F.; Khalil, I.A.; Rao, P.C.; Cao, S.; Zimsen, S.R.; Albertson, S.B.; Stanaway, J.D.; Deshpande, A.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1211–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raso, M.M.; Arato, V.; Gasperini, G.; Micoli, F. Toward a Shigella vaccine: opportunities and challenges to fight an antimicrobial-resistant pathogen. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wotzka, S.Y.; Nguyen, B.D.; Hardt, W.D. Salmonella Typhimurium diarrhea reveals basic principles of enteropathogen infection and disease-promoted DNA exchange. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Arabi, T.F.; Griffiths, M.W. Bacillus cereus. Foodborne Infections and Intoxications 2021, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzari, M.; Sharma, M.; Chetia, P. Emergence of antibiotic resistant Shigella species: A matter of concern. J. Infect. Public Health 2018, 11, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung The, H.; Bodhidatta, L.; Pham, D.T.; Mason, C.J.; Ha Thanh, T.; Voong Vinh, P.; Turner, P.; Hem, S.; Dance, D.A.B.; Newton, P.N.; et al. Evolutionary histories and antimicrobial resistance in Shigella flexneri and Shigella sonnei in Southeast Asia. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Biswas, S.; Paudyal, N.; Pan, H.; Li, X.; Fang, W.; Yue, M. Antibiotic resistance in Salmonella Typhimurium isolates recovered from the food chain through national antimicrobial resistance monitoring system between 1996 and 2016. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 450730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, G.; Schneider, C.; Igbinosa, E.O.; Kabisch, J.; Brinks, E.; Becker, B.; Stoll, D.A.; Cho, G.S.; Huch, M.; Franz, C.M.A.P. Antibiotics resistance and toxin profiles of Bacillus cereus-group isolates from fresh vegetables from German retail markets. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, J.W.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.J.; Hyeon, J.Y.; Seo, K.H. Toxin profile, antibiotic resistance, and phenotypic and molecular characterization of Bacillus cereus in Sunsik. Food Microbiol. 2012, 32, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, H.; Bishnoi, P.; Yadav, A.; Patni, B.; Mishra, A.P.; Nautiyal, A.R. Antimicrobial resistance and the alternative resources with special emphasis on plant-based antimicrobials—A review. Plants 2017, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwana, G.; Cock, I.E.; Cheesman, M.J. A Review of Ayurvedic principles and the use of Ayurvedic plants to control diarrhoea and gastrointestinal infections. Pharmacogn. Commun. 2023, 13, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.; Singh, P.K.; Kumar, V. Evidence based traditional anti-diarrheal medicinal plants and their phytocompounds. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 96, 1453–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikumar, R.; Jeya Parthasarathy, N.; Shankar, E.M.; Manikandan, S.; Vijayakumar, R.; Thangaraj, R.; Vijayananth, K.; Sheeladevi, R.; Rao, U.A. Evaluation of the growth inhibitory activities of Triphala against common bacterial isolates from HIV infected patients. Phytother. Res. 2007, 21, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, P.; Devi, P.N.; Kaleeswari, S.; Poonkothai, M. Antimicrobial activity and phytochemical analysis of fruit extracts of Terminalia Bellerica. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 43, 364. [Google Scholar]

- Madani, A.; Jain, S.K. Anti-Salmonella activity of Terminalia belerica: In vitro and in vivo studies. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2008, 46, 817–821. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Q.; Shang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Fakhar-e-Alam Kulyar, M.; Suo-lang, S.; Xu, Y.; Tan, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, S. Preventive effect of Terminalia bellirica (Gaertn.) Roxb. extract on mice infected with Salmonella Typhimurium. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwana, G.; Cock, I.E.; White, A.; Cheesman, M.J. Use of specific combinations of the triphala plant component extracts to potentiate the inhibition of gastrointestinal bacterial growth. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 260, 112937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwana, G.; Cock, I.E.; Cheesman, M.J. Phyllanthus niruri Linn.: Antibacterial activity, phytochemistry, and enhanced antibiotic combinatorial strategies. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doern, C.D. When does 2 plus 2 equal 5? A review of antimicrobial synergy testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 4124–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruebhart, D.R.; Wickramasinghe, W.; Cock, I.E. Protective efficacy of the antioxidants vitamin E and Trolox against Microcystis aeruginosa and microcystin-LR in Artemia franciscana Nauplii. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2009, 72, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwana, G.; Cock, I.E.; Cheesman, M.J. Combinations of Terminalia bellirica (Gaertn.) Roxb. and Terminalia chebula Retz. extracts with selected antibiotics against antibiotic-resistant bacteria: Bioactivity and phytochemistry. Antibiotics 2024, 13(10), 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cajka, T.; Hricko, J.; Rudl Kulhava, L.; Paucova, M.; Novakova, M.; Kuda, O. Optimization of mobile phase modifiers for fast LC-MS-based untargeted metabolomics and lipidomics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 31987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altemimi, A.; Lakhssassi, N.; Baharlouei, A.; Watson, D.G.; Lightfoot, D.A. Phytochemicals: Extraction, isolation, and identification of bioactive compounds from plant extracts. Plants 2017, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonev, B.; Hooper, J.; Parisot, J. Principles of assessing bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics using the agar diffusion method. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 61, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, J.N.; Steck, T.R. The relationship between agar thickness and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Indian J. Microbiol. 2017, 57, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Patel, N.; Lin, S. Solubility and dissolution enhancement strategies: Current understanding and recent trends. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2015, 41, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.; Flores, V.; Cabrera, R.; Soto-Guzmán, A.; Granados, G.; Juaristi, E.; Guarneros, G.; De La Torre, M. Evolution and some functions of the NprR-NprRB quorum-sensing system in the Bacillus cereus group. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 94, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceuppens, S.; Rajkovic, A.; Heyndrickx, M.; Tsilia, V.; Van De Wiele, T.; Boon, N.; Uyttendaele, M. Regulation of toxin production by Bacillus cereus and its food safety implications. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 37, 188–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stårsta, M.; Hammarlof, D.L.; Waneskog, M.; Schlegel, S.; Xu, F.; Gynnå, A.H.; Borg, M.; Herschend, S.; Koskiniemi, S. RHS-elements function as type II toxin-antitoxin modules that regulate intra-macrophage replication of Salmonella Typhimurium. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakbin, B.; Amani, Z.; Allahyari, S.; Mousavi, S.; Mahmoudi, R.; Brück, W.M.; Peymani, A. Genetic diversity and antibiotic resistance of Shigella spp. isolates from food products. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 6362–6371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzari, M.; Sharma, M.; Chetia, P. Emergence of antibiotic resistant Shigella species: A matter of concern. J. Infect. Public Health 2018, 11, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slingerland, C.J.; Kotsogianni, I.; Wesseling, C.M.J.; Martin, N.I. Polymyxin stereochemistry and its role in antibacterial activity and outer membrane disruption. ACS Infect. Dis. 2022, 8, 2396–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehling-Schulz, M.; Koehler, T.M.; Lereclus, D. The Bacillus cereus group: Bacillus species with pathogenic potential. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berbers, B.; Vanneste, K.; Roosens, N.H.C.J.; Marchal, K.; Ceyssens, P.J.; De Keersmaecker, S.C.J. Using a combination of short-and long-read sequencing to investigate the diversity in plasmid and chromosomally encoded extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) in clinical Shigella and Salmonella isolates in Belgium. Microb. Genom 2023, 9, 000925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, K.; Bradford, P.A. Epidemiology of β-lactamase-producing pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auda, I.G.; Ali Salman, I.M.; Odah, J.G. Efflux pumps of gram-negative bacteria in brief. Gene Rep. 2020, 20, 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenazy, R. Antibiotic Resistance in Salmonella: Targeting multidrug resistance by understanding efflux pumps, regulators, and the inhibitors. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stogios, P.J.; Savchenko, A. Molecular mechanisms of vancomycin resistance. Protein Sci. 2020, 29, 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheesman, M.; Ilanko, A.; Blonk, B.; Cock, I.E. Developing new antimicrobial therapies: Are synergistic combinations of plant extracts/compounds with Conventional antibiotics the solution? Pharmacogn. Rev. 2017, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttner, A.; Bielicki, J.; Clements, M.N.; Frimodt-Møller, N.; Muller, A.E.; Paccaud, J.P.; Mouton, J.W. Oral amoxicillin and amoxicillin–clavulanic Acid: Properties, indications, and usage. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelschlaeger, P. β-Lactamases: Sequence, structure, function, and inhibition. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khameneh, B.; Eskin, N.A.M.; Iranshahy, M.; Fazly Bazzaz, B.S. Phytochemicals: A promising weapon in the arsenal against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Gupta, V.K.; Pathania, R. Efflux pump inhibitors for bacterial pathogens: From bench to bedside. Indian J. Med. Res. 2019, 149, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehrenberg, C.; Schwarz, S.; Jacobsen, L.; Hansen, L.H.; Vester, B. A new mechanism for chloramphenicol, florfenicol and clindamycin resistance: Methylation of 23S ribosomal RNA at A2503. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 57, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; He, J.; Bai, L.; Ruan, S.; Yang, T.; Luo, Y. Ribosome-targeting antibacterial agents: Advances, challenges, and opportunities. Med. Res. Rev. 2021, 41, 1855–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Javor, S.; Gan, B.H.; Köhler, T.; Reymond, J.L. The antibacterial activity of peptide dendrimers and polymyxin B increases sharply above pH 7.4. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 5654–5657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavascki, A.P.; Goldani, L.Z.; Li, J.; Nation, R.L. Polymyxin B for the treatment of multidrug-resistant pathogens: A critical review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, 1206–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, I.E. The medicinal properties and phytochemistry of plants of the genus Terminalia (Combretaceae). Inflammopharmacology 2015, 23, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Krishna, M.J.; Joshi, A.B.; Gurav, S.; Bhandarkar, A. V; Agarwal, A.; Mythili Krishna, C.J. A pharmacognostic, phytochemical and pharmacological review of Terminalia bellerica. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2017, 6, 368–376. [Google Scholar]

- Bag, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.K.; Chattopadhyay, R.R. The development of Terminalia chebula Retz. (Combretaceae) in clinical research. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhanu, B.T.; Park, N.H.; Lee, S.J.; Hossain, M.A.; Park, S.C. Inhibition of Salmonella Typhimurium adhesion, invasion, and intracellular survival via treatment with methyl gallate alone and in combination with marbofloxacin. Vet. Res. 2018, 49, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharyya, S.; Sarkar, P.; Saha, D.R.; Patra, A.; Ramamurthy, T.; Bag, P.K. Intracellular and membrane-damaging activities of methyl gallate isolated from Terminalia chebula against multidrug-resistant Shigella spp. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015, 64, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiamboonsri, P.; Eurtivong, C.; Wanwong, S. Assessing the potential of gallic acid and methyl gallate to enhance the efficacy of β-lactam antibiotics against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by targeting β-lactamase: In silico and in vitro studies. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.G.; Mun, S.H.; Chahar, H.S.; Bharaj, P.; Kang, O.H.; Kim, S.G.; Shin, D.W.; Kwon, D.Y. Methyl gallate from Galla rhois successfully controls clinical isolates of Salmonella infection in both in vitro and in vivo systems. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.G.; Kang, O.H.; Lee, Y.S.; et al. Antibacterial activity of methyl gallate isolated from Galla Rhois or carvacrol combined with nalidixic acid against nalidixic acid resistant bacteria. Molecules 2009, 14, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, M.; Wu, X.; Li, J. Antibacterial activity of gallic acid against Shigella flexneri and its effect on biofilm formation by repressing mdoH gene expression. Food Control 2018, 94, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Park, H.C.; Lee, K.J.; Park, S.W.; Park, S.C.; Kang, J. In vitro synergistic potentials of novel antibacterial combination therapies against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuelsaad, A.S.A.; Mohamed, I.; Allam, G.; Al-Solumani, A.A. Antimicrobial and immunomodulating activities of hesperidin and ellagic acid against diarrheic Aeromonas hydrophila in a murine model. Life Sci. 2013, 93, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuete, V.; Wabo, G.F.; Ngameni, B.; Mbaveng, A.T.; Metuno, R.; Etoa, F.X.; Ngadjui, B.T.; Beng, V.P.; Meyer, J.J.M.; Lall, N. Antimicrobial activity of the methanolic extract, fractions and compounds from the stem bark of Irvingia gabonensis (Ixonanthaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 114, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhanu, B.T.; Lee, E.B.; Lee, S.J.; Park, S.C. Targeting Salmonella Typhimurium invasion and intracellular survival using pyrogallol. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 631426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirudkar, J.R.; Parmar, K.M.; Prasad, R.S.; Sinha, S.K.; Jogi, M.S.; Itankar, P.R.; Prasad, S.K. Quercetin a major biomarker of Psidium guajava L. inhibits SepA protease activity of Shigella flexneri in treatment of infectious diarrhoea. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 138, 103807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, P.K.; Song, M.G.; Park, S.Y. Impact of quercetin against Salmonella Typhimurium biofilm formation on food–contact surfaces and molecular mechanism pattern. Foods 2022, 11, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.Y.; Sohn, M.J.; Lee, J.; Kim, W.G. Isolation and identification of pentagalloylglucose with broad-spectrum antibacterial activity from Rhus trichocarpa Miquel. Food Chem. 2010, 123, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extract type or Antibiotic | Bacterial species & MIC (µg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. cereus | S. flexneri | S. sonnei | S. typhimurium | |

| TB-AQ | 392 | 392 | 1569 | 3138 |

| TB-MeOH | 94 | 377 | 755 | 755 |

| TB-EtOAc | 450 | 450 | >10000 | >10000 |

| TCh-AQ | 556 | 278 | 2225 | 2225 |

| TCh-MeOH | 377 | 377 | 1509 | 3019 |

| TCh-EtOAC | 306 | 306 | 1225 | >10000 |

| PENG | 0.625 | >2.5 | >2.5 | >2.5 |

| ERY | 0.08 | >2.5 | >2.5 | >2.5 |

| TET | 0.08 | 0.625 | 0.31 | 0.625 |

| CHL | 1.25 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| CIP | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| POL | >2.5 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.31 |

| OXA | 1.25 | >2.5 | >2.5 | >2.5 |

| AMX | 0.625 | >2.5 | >2.5 | >2.5 |

| GEN | 0.16 | 0.625 | 2.5 | 0.625 |

| VAN | 0.625 | >2.5 | >2.5 | >2.5 |

| Bacteria | Extract | PENG | ERY | TET | CHL | CIP | POLB | OXA | AMX | GEN | VAN |

| B. cereus | TB-AQ | 0.56 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 2.00 | - | 1.03 | 0.56 | 1.50 | 0.56 |

| TB-MeOH | 1.03 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.02 | 1.25 | - | 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.13 | 2.07 | |

| TB-EtOAc | 1.50 | 2.12 | 2.12 | 2.00 | 1.06 | - | 1.50 | 1.50 | 8.81 | 1.50 | |

| TCh-AQ | 0.56 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.13 | 1.50 | - | 0.53 | 0.81 | 2.00 | 1.26 | |

| TCh-MeOH | 0.78 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 2.00 | - | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.75 | 1.13 | |

| TCh-EtOAc | 0.51 | 2.25 | 2.25 | 1.50 | 2.25 | - | 0.62 | 1.00 | 2.44 | 1.50 | |

| S. flexneri | TB-AQ | - | - | 1.13 | 1.06 | 2.00 | 5.00 | - | - | 0.56 | - |

| TB-MeOH | - | - | 1.13 | 1.06 | 1.50 | 5.00 | - | - | 1.13 | - | |

| TB-EtOAc | - | - | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 15.75 | - | - | 3.00 | - | |

| TCh-AQ | - | - | 1.13 | 1.06 | 1.50 | 5.00 | - | - | 1.13 | - | |

| TCh-MeOH | - | - | 1.13 | 1.06 | 2.00 | 5.00 | - | - | 1.13 | - | |

| TCh-EtOAc | - | - | 1.00 | 1.50 | 2.25 | 16.00 | - | - | 4.00 | - | |

| S. sonnei | TB-AQ | - | - | 1.00 | 0.56 | 1.25 | 8.50 | - | - | 1.12 | - |

| TB-MeOH | - | - | 0.75 | 1.06 | 3.00 | 9.00 | - | - | 0.53 | - | |

| TB-EtOAc | - | - | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 4 | - | - | 4 | - | |

| TCh-AQ | - | - | 0.75 | 0.62 | 1.12 | 32.25 | - | - | 0.62 | - | |

| TCh-MeOH | - | - | 1.00 | 1.12 | 2.50 | 16.50 | - | - | 0.56 | - | |

| TCh-EtOAc | - | - | 1.12 | 1.00 | 2.06 | 63.00 | - | - | 4 | - | |

| S. typhimurium | TB-AQ | - | - | 1.00 | 1.25 | 2.44 | 3.00 | - | - | 1.50 | - |

| TB-MeOH | - | - | 0.75 | 1.12 | 2.00 | 2.00 | - | - | 0.75 | - | |

| TCh-AQ | - | - | 1.00 | 1.25 | 2.44 | 6.03 | - | - | 2.00 | - | |

| TCh-MeOH | - | - | 1.00 | 1.25 | 2.44 | 3.00 | - | - | 2.00 | - |

| Retention Time (min) | Molecular Weight | Empirical Formula | Putative Compounds | % Relative Abundance (TB) | % Relative Abundance (TCh) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQ | MeOH | EtOAc | AQ | MeOH | EtOAc | ||||

| 1.496 | 192.06305 | C7H12O6 | Quinic acid | 3.13 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.39 | - | 1.53 |

| 1.573 | 344.07409 | C14H16O10 | Theogallin | - | 3.47 | - | - | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| 1.784 | 302.06328 | C12H14O9 | Pyrogallol-2-O-glucuronide | - | 0.21 | - | 0.07 | - | - |

| 2.045 | 294.03749 | C13H10O8 | Banksiamarin B | - | - | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.13 |

| 2.058 | 174.05268 | C7H10O5 | Shikimic acid | - | 0.41 | 0.67 | 2.64 | 3.14 | 4.80 |

| 2.237 | 154.02646 | C7H6O4 | Gentisic acid | 0.02 | 0.05 | - | 0.01 | - | 0.09 |

| 2.296 | 448.15769 | C19H28O12 | 8-O-Acetyl shanzhiside methyl ester | - | - | - | 0.19 | 0.18 | - |

| 2.356 | 332.07411 | C13H16O10 | 6-Galloylglucose | 6.06 | 3.97 | 3.39 | 3.74 | 0.68 | - |

| 2.444 | 448.06386 | C20H16O12 | Ellagic acid 2-rhamnoside | 0.11 | 1.44 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.33 |

| 2.51 | 292.02177 | C13H8O8 | Brevifolincarboxylic acid | 0.09 | - | - | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.61 |

| 2.56 | 288.0844 | C12H16O8 | Phlorin | - | 0.02 | - | 0.03 | 0.02 | - |

| 3.11 | 484.0848 | C20H20O14 | Gallic acid 3-O-(6-galloylglucoside) | 0.74 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3.158 | 212.06824 | C10H12O5 | Propyl gallate | - | - | - | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.12 |

| 4.4 | 277.05821 | C13H11NO6 | Salfredin C1 | - | - | - | 0.14 | - | 0.03 |

| 4.847 | 184.03703 | C8H8O5 | Methyl gallate | 0.25 | 11.39 | - | 0.04 | 1.05 | - |

| 8.44 | 484.0855 | C20H20O14 | 1,6-Bis-O-(3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoyl) hexopyranose | 5.13 | 5.19 | 2.52 | 6.52 | 2.16 | 3.78 |

| 9.316 | 470.01176 | C21H10O13 | Sanguisorbic acid dilactone | - | 0.08 | - | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.19 |

| 9.567 | 634.08082 | C27H22O18 | Sanguiin H4 | 0.84 | - | 0.07 | - | 5.63 | 0.54 |

| 9.811 | 478.07452 | C21H18O13 | Miquelianin | 0.04 | 0.42 | - | 0.37 | 0.60 | 0.39 |

| 9.902 | 152.04703 | C8H8O3 | Vanillin | - | - | - | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| 9.921 | 126.03146 | C6H6O3 | Phloroglucinol | 0.10 | 1.93 | - | 0.07 | 0.24 | 0.27 |

| 10.043 | 636.09614 | C27H24O18 | 1,2,6-Trigalloyl-β-D-glucopyranose | 0.09 | 5.44 | 2.85 | 0.11 | 1.42 | 2.22 |

| 10.419 | 484.08522 | C20H20O14 | Hamamelitannin | 2.10 | 0.02 | 0.62 | 0.02 | 0.11 | - |

| 10.421 | 126.0316 | C6H6O3 | Pyrogallol | 6.28 | 5.28 | 2.19 | 6.29 | 3.82 | 4.87 |

| 10.422 | 296.05248 | C13H12O8 | cis-Coutaric acid | 0.33 | 0.86 | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.93 | 1.05 |

| 10.55 | 601.99658 | C28H10O16 | Diellagilactone | - | - | - | 1.13 | 0.60 | - |

| 10.703 | 372.1055 | C16H20O10 | Veranisatin C | 0.02 | 0.04 | - | - | - | - |

| 10.754 | 636.09608 | C27H24O18 | 1,3,6-Tri-O-galloyl-β-D-glucose | - | 0.25 | 0.93 | 0.64 | - | - |

| 11.305 | 170.02138 | C7H6O5 | Phloroglucinic acid | 0.98 | 2.80 | 4.33 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 1.24 |

| 11.091 | 610.1535 | C27H30O16 | Rutin | - | 0.14 | 0.10 | - | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| 11.176 | 432.10539 | C21H20O10 | Vitexin | - | - | - | - | 0.05 | - |

| 11.448 | 302.04213 | C15H10O7 | Quercetin | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.02 | - | - |

| 11.473 | 464.0951 | C21H20O12 | Myricitrin | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.19 | - | - | - |

| 11.589 | 170.02147 | C7H6O5 | Gallic acid | 26.23 | 8.64 | 2.60 | 23.90 | 1.90 | 1.56 |

| 11.822 | 462.07961 | C21H18O12 | Aureusidin 6-glucuronide | - | - | 2.52 | - | - | 0.04 |

| 11.905 | 286.04729 | C15H10O6 | Maritimetin | - | - | - | T | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 12.183 | 448.0996 | C21H20O11 | Maritimein | - | 0.01 | 0.02 | - | - | - |

| 12.185 | 302.00627 | C14H6O8 | Ellagic acid | 2.45 | 10.74 | 33.49 | 8.39 | 10.46 | 11.96 |

| 12.233 | 262.0476 | C13H10O6 | Maclurin | - | 0.02 | - | 0.04 | - | - |

| 12.254 | 148.05223 | C9H8O2 | trans-Cinnamic acid | - | - | - | 0.76 | 0.96 | 0.87 |

| 12.503 | 192.07847 | C11H12O3 | (R)-Shinanolone | - | - | - | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| 12.509 | 610.1894 | C28H34O15 | Neohesperidin | - | - | 0.16 | - | - | - |

| 12.584 | 498.1741 | C23H30O12 | Eucaglobulin | - | 0.02 | - | - | - | - |

| 12.593 | 436.13688 | C21H24O10 | Nothofagin | - | - | - | - | - | 0.12 |

| 12.721 | 680.37692 | C36H56O12 | Tenuifolin | - | - | - | - | 0.11 | 0.37 |

| 12.8 | 486.33397 | C30H46O5 | Bassic acid | - | - | - | - | - | 0.05 |

| 12.844 | 518.1785 | C26H30O11 | Phellodensin E | - | - | 0.05 | - | - | - |

| 12.889 | 346.1052 | C18H18O7 | Hamilcone | - | - | - | 0.02 | - | 0.01 |

| 12.914 | 190.13544 | C13H18O | β-Damascenone | - | - | - | - | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| 12.915 | 666.39739 | C36H58O11 | Chebuloside II | - | - | - | - | 3.85 | - |

| 12.924 | 302.1152 | C17H18O5 | Lusianin | 0.01 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 12.929 | 356.03763 | C14H12O11 | (+)-Chebulic acid | 0.54 | - | - | 3.98 | 1.40 | 2.88 |

| 12.969 | 504.34417 | C30H48O6 | Madecassic acid | - | - | - | - | - | 1.42 |

| 12.971 | 202.13522 | C14H18O | (±)-Anisoxide | - | - | - | - | - | 0.05 |

| 12.973 | 244.14583 | C16H20O2 | Lahorenoic acid C | - | - | - | - | - | 0.02 |

| 13.208 | 288.06318 | C15H12O6 | Eriodictyol | - | - | - | - | - | 0.27 |

| 13.428 | 442.1992 | C25H30O7 | Exiguaflavanone M | - | - | 0.13 | - | - | - |

| 13.451 | 274.08371 | C15H14O5 | Phloretin | - | - | - | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 13.536 | 462.11641 | C22H22O11 | Leptosin | - | 0.01 | - | 0.01 | 0.06 | - |

| 13.59 | 302.04255 | C15H10O7 | Bracteatin | - | - | - | 0.01 | 0.01 | - |

| 13.593 | 502.1836 | C26H30O10 | Flavaprin | - | - | 0.07 | - | - | - |

| 13.678 | 568.12178 | C28H24O13 | Isoorientin 2"-p-hydroxybenzoate | - | - | - | - | - | 0.04 |

| 13.703 | 280.13067 | C15H20O5 | Artabsinolide A | - | - | - | - | - | 0.02 |

| 13.805 | 444.10499 | C22H20O10 | 3'-O-Methylderhamnosylmaysin | - | - | - | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| 13.805 | 292.09447 | C15H16O6 | (S)-Angelicain | - | - | - | 0.05 | - | - |

| 14.024 | 500.1674 | C26H28O10 | Ikarisoside A | - | - | 0.03 | - | - | - |

| 14.078 | 534.28285 | C29H42O9 | Corchoroside A | - | - | - | - | - | 0.02 |

| 14.358 | 272.06832 | C15H12O5 | Naringenin | - | - | - | - | - | 0.18 |

| 14.367 | 470.33907 | C30H46O4 | Glycyrrhetinic acid | - | - | - | - | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| 14.783 | 234.16167 | C15H22O2 | Valerenic acid | - | - | - | - | - | 0.13 |

| 14.928 | 202.17175 | C15H22 | Rulepidadiene B | - | - | - | - | - | 0.08 |

| 14.93 | 222.16153 | C14H22O2 | Rishitin | - | - | - | - | - | 0.04 |

| 15.046 | 426.09477 | C22H18O9 | Epiafzelechin 3-O-gallate | - | - | - | - | - | 0.01 |

| 15.454 | 650.4026 | C36H58O10 | Pedunculoside | - | - | - | - | 1.18 | 2.61 |

| 16.257 | 738.41926 | C39H62O13 | Isonuatigenin 3-[rhamnosyl-(1->2)-glucoside] | - | - | - | - | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| 16.301 | 470.1941 | C26H30O8 | Limonin | - | - | 0.14 | - | - | - |

| 16.478 | 540.1663 | C25H32O11S | Sumalarin B | - | - | 0.02 | - | - | - |

| 16.532 | 316.1308 | C18H20O5 | Methylodoratol | - | - | 0.02 | - | - | - |

| 16.787 | 472.2097 | C26H32O8 | Kushenol H | - | - | 0.07 | - | - | - |

| 16.844 | 344.0532 | C17H12O8 | 3,4,3'-Tri-O-methylellagic acid | - | - | 0.01 | - | - | - |

| 16.876 | 252.20856 | C16H28O2 | Isoambrettolide | - | - | - | - | - | 0.32 |

| 17.064 | 440.1828 | C25H28O7 | Lonchocarpol E | - | - | 0.15 | - | - | - |

| 17.209 | 544.2668 | C30H40O9 | Physagulin F | - | - | 0.10 | - | - | - |

| 17.276 | 180.11471 | C11H16O2 | Jasmolone | - | 0.61 | 1.48 | 0.05 | - | - |

| 17.31 | 504.34409 | C30H48O6 | Protobassic acid | - | - | - | 1.26 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 17.33 | 468.32326 | C30H44O4 | Glabrolide | - | - | - | 0.87 | - | 3.19 |

| 17.33 | 502.32964 | C30H46O6 | Medicagenic acid | - | - | - | - | T | 0.07 |

| 17.331 | 200.15605 | C15H20 | (S)-gamma-Calacorene | - | - | - | 0.02 | - | 0.29 |

| 17.363 | 696.40877 | C37H60O12 | Momordicoside E | - | - | - | - | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| 17.626 | 286.08357 | C16H14O5 | Homobutein | - | T | 0.01 | - | - | 0.01 |

| 17.635 | 282.12541 | C18H18O3 | Ohobanin | 0.01 | T | 0.09 | T | - | 0.06 |

| 17.671 | 652.27302 | C32H44O14 | Dicrocin | - | - | - | - | - | 0.03 |

| 17.902 | 424.1881 | C25H28O6 | Paratocarpin G | T | - | - | - | - | - |

| 17.949 | 456.2144 | C26H32O7 | Antiarone J | - | 0.54 | - | - | - | - |

| 18.124 | 372.2509 | C20H36O6 | Sterebin Q4 | - | - | 0.01 | - | - | - |

| 18.237 | 428.1831 | C24H28O7 | Heteroflavanone B | - | - | 0.05 | - | - | - |

| 18.237 | 312.13615 | C19H20O4 | Desmosdumotin C | T | - | 0.02 | T | - | 0.02 |

| 18.292 | 546.35535 | C32H50O7 | Hovenidulcigenin B | - | - | - | 0.04 | - | - |

| 18.339 | 236.1776 | C15H24O2 | Capsidiol | - | - | - | - | - | 0.02 |

| 18.346 | 268.13069 | C14H20O5 | Kamahine C | 0.02 | 0.01 | - | - | 0.01 | 0.15 |

| 18.363 | 336.0994 | C20H16O5 | Ciliatin A | - | - | - | - | 0.01 | - |

| 18.498 | 340.09447 | C19H16O6 | Ambanol | - | - | - | - | 0.01 | - |

| 18.507 | 484.31803 | C30H44O5 | Liquoric acid | - | - | - | T | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| 18.623 | 488.35017 | C30H48O5 | Pitheduloside I | - | - | - | T | 0.06 | 0.11 |

| 19.641 | 226.09903 | C15H14O2 | 7-Hydroxyflavan | - | 0.84 | - | 0.03 | - | 0.05 |

| 18.748 | 208.1096 | C12H16O3 | Isoelemicin | 0.01 | - | 0.19 | - | - | - |

| 18.767 | 526.2565 | C30H38O8 | Kosamol A | - | 0.52 | - | - | - | - |

| 18.987 | 372.1208 | C20H20O7 | Tangeretin | - | - | 0.03 | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).