1. Introduction

Lassa virus (LASV), the causative agent of Lassa fever (LF), is endemic to large regions of Western Africa, where it is estimated to infect several hundred thousand people resulting in many cases of LF, a febrile disease associated with high morbidity and case-fatality rates (CFRs) of 15%‒20% among hospitalized LF patients [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Since 2018 there has been an unprecedented rise in the incidence of Lassa fever (LF) cases in Western African countries, including Nigeria. The CFR in confirmed cases of LF in Nigeria by November 2019 reached 21%. LF has been listed as one of the priority diseases for research and countermeasures development by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2018 [

6,

7,

8]. LF is a hemorrhagic fever disease with epidemic potential and for which no licensed vaccines or specific therapies are currently available. The off-label use of the nucleoside analog ribavirin has been reported to provide clinical benefits if treatment is initiated within six days of onset of symptoms. However, the efficacy of ribavirin remains controversial [

9,

10] and it can cause significant side effects [

11,

12]. Hence, the development of therapeutics to treat LF represents an unmet problem of clinical significance.

LASV is an enveloped virus with a bi-segmented negative stranded RNA genome [

13,

14]. Each genome segment uses an ambisense coding strategy to express two viral proteins from open reading frames separated by non-coding intergenic regions (IGR). The large (L) segment encodes the virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, L protein, and the matrix Z protein, whereas the small (S) segment encodes the nucleoprotein (NP) and the glycoprotein precursor GPC [

13,

15,

16]. GPC is co-translationally processed by cellular signal peptidase to generate a stable signal peptide (SSP) and a GPC precursor that is post-translationally cleaved by the cellular proprotein convertase, subtilisin kexin isozyme-1/site-1 protease (SKI-1/S1P), to generate GP1 and GP2 subunits. The GP1 and GP2 subunits together with the SSP form mature glycoprotein (GP) peplomers on the surface of the virion envelope that mediate virion cell entry via receptor-mediated endocytosis. LASV GP1 interacts with α-dystroglycan [

17,

18] and the lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP-1) [

19] to facilitate virus cell entry. GP2 is responsible for mediating the pH-dependent fusion of the virus and the host cell membranes to complete the entry process [

20,

21]. NP is the most abundant viral protein in virions and infected cells. As with other mammarenaviruses, LASV NP encapsidates the viral genome to generate the nucleocapsid (NC) template that in association with the virus RdRp, L protein, forms the viral ribonucleoprotein complex (vRNP) responsible for directing the biosynthetic processes of replication and transcription of the viral genome [

13]. The C-terminal region of NP contains a 3’-5’ exoribonuclease domain (ExoN) of the type DEDDH that has been implicated in NP’s anti-interferon activity and viral fitness [

22], as well as evading PKR kinase activity [

23]. The LASV matrix Z, a myristoylated, protein plays critical roles in the assembly and cell egress via budding of viral particles [

24,

25] and it can be a target for N-myristoyl transferases inhibitors [

26].

Several experimental drugs targeting different steps of LASV lifecycle are currently being investigated, or repurposed, as candidate therapeutics to treat mammarenavirus, including LASV, infections [

27], and the LASV GP-mediated fusion inhibitor LHF-535 is in phase I clinical trials [

28]. However, the uncertainty about their in vivo efficacy underscores the need of research aimed at expanding the number and diversity of candidate drugs to treat infections by human pathogenic mammarenaviruses, including LASV. In the present work, using in silico docking simulation methods we have identified five existing drugs with high binding affinities to LASV L, NP and Z proteins and tested their antiviral activity using LASV and LCMV cell-based minigenome systems and LCMV cell-based infection assays. We found that flunarizine (FLN) inhibited the activity of the LASV and LCMV MG and significantly reduced (≥ 1 log) peak titers of LCMV in a multi-step growth kinetics assay in human A549 cells. FLN inhibited GP2-mediated fusion required for completion of virus cell entry and the activity of the vRNP, findings consistent with the activity of FLN as a selective calcium-entry blocker antagonist [

29,

30] as Ca

2+ flow and signaling have been shown to contribute to different steps of multiplication of different viruses [

31,

32,

33,

34]. However, other selected calcium channel blockers including the combined L-/T-type (verapamil and nickel chloride) [

35,

36,

37,

38] , and L-type (nifedipine and gabapentin) [

39,

40,

41,

42] calcium channel blockers did not exhibit significant anti-LCMV activity, suggesting that FLN anti-mammarenaviral activity may not be related to its ability to block T-type calcium channels. FLN binds calmodulin, which could interfere with the role of calmodulin in low pH induced intracellular membrane fusion [

43], thus interfering with GP2-mediated, pH-induced fusion event required for mammarenavirus cell entry.

FLN is a selective calcium-entry blocker antagonist that is being used in many countries worldwide to treat vertigo and migraine, supporting the interest in exploring its repurposing as a candidate drug to treat LASV infections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Silico Screening

The 3D structures of LASV L polymerase (PDB, 5J1N), nucleoprotein (NP) (PDB, 3q7c), and Z matrix protein (PDB, 2M1S) were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), examined with PyMol-1.4.1 and appropriately prepared for molecular docking simulations using Chimera-1.9 [

44] and MGLTools-1.5.6 [

45]. A total of 2015 existing drugs were obtained from Drugbank and prepared for molecular docking simulations using MGLTools-1.5.6 [

46]. Briefly, all hydrogen and Gasteiger charges were added, roots were detected; torsions and all rotatable bonds were allowed in their natural states. Then outputs were generated as a pdbqt file extension and used for the virtual screening after validation of docking protocols.

To validate the molecular docking simulations protocol, the experimental complexes of the reference compounds and the respective targets were reproduced in silico. Briefly, the reference compounds and all hetero-molecules in the drug target were deleted using Chimera-1.9 [

44]. Polar hydrogen, Kollman charges, grid box sizes and centers at grid space of 1.0 Å were determined with MGLTools-1.5.6 [

45]. Before the validation, the reference compound was extracted from its receptor and subjected to 1000 steps of steepest descent and 100 steps of conjugate gradient energy minimization at step size of 0.02 using Chimera-1.9. Then, it was prepared for molecular docking simulations using MGLTools-1.5.6 [

45]. Briefly, all hydrogen and Kollman charges were added, roots were detected; torsions and all rotatable bonds were allowed in their natural states. Output was then generated as a pdbqt file extension.

The compounds library set was batched for molecular docking simulations against the three LASV protein targets using virtual screening scripts. Molecular docking simulations were implemented, in four replicates, on a Linux platform using AutoDockVina [

47] and associated tools after validation of docking protocols. Binding free energy values (kcal/mol ± SD) were ranked to identify the frontrunner compounds. The

inhibition constant (Ki) was obtained from the binding energy (ΔG) using the formula: Ki = exp(ΔG/RT), where R is the universal gas constant (1.985 × 10−3 kcal mol−1 K−1) and T is the temperature (298.15 K). Existing drugs with strong L, NP and Z binding affinities were selected as potential candidate therapeutics for the treatment of LF. Molecular descriptors of selected compounds were extracted from relevant databases.

To select existing drugs for possible treatment of mild infections of Lassa fever (early presenters), we first sorted out existing drugs with very strong polymerase binding affinities (with efavirenz as cut-off compound), then sorted the resulting list for good myristoylation binding affinities (with acyclovir as cut-off compound) before finally sorting the list for good nuclease binding affinities (with FMOC_D_Cha_OH as cut-off compound). Similarly, existing drugs with very strong nuclease binding affinities (with FMOC_D_Cha_OH as cut-off compound) were first sorted from the list. The resulting list was subsequently sorted for good myristoylation binding affinities (with lassamycin as cut-off compound) and finally the remaining existing drugs were sorted for good polymerase binding affinities (without any cut-off compound) to generate the list of drugs for possible treatment of severe infections of Lassa fever (late presenters).

The LF virus proteins residues responsible for interactions with some frontrunner existing drugs were also explored in the respective receptor-ligand complexes using Discovery Studio 2024.

2.2. Source of Compounds

FLN dihydrochloride (HY-B0358A, MedChemExpress), mefloquine (MEF) hydrochloride (HY-17437A MedChemExpress), Egorciferol (Vit D) (HY-76542 MedChemExpress), tadalafil (TAD) (HY-90009A MedChemExpress), dexamethasone (DEX) (D2915 Sigma-Aldrich).

2.3. Cells, and Viruses

HEK 293T (ATCC CRL-3216), Vero E6 (ATCC CRL-1586) and A549 (ATCC CCL-185) cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 100U/ml of penicillin. Recombinant viruses rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP [

48], r3JUNVCandid GFP/GFP [

49], rARMΔGPC/ZsG-P2A-NP [

50] have been described.

2.4. Virus Titration

Virus titers were determined by focus-forming assay (FFA) [

51] using Vero E6 cells. Briefly, cells were seeded in a 96-well plate (2 × 10

4 cells/well) and next day infected with 10-fold serial virus dilutions. At 20 h post infection (hpi), cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS and infected cells were identified by epifluorescence based on their GFP expression.

2.5. Cell-Based Minigenome (MG) Assays

The LASV and LCMV MG systems have been described [

50,

52] and were used to assess the anti-vRNP activity of hits identified by in silico docking.

2.5.1. LASV MG Assay

HEK293T cells were seeded onto poly-L-lysine coated 12 well plates (3.0 x 105 cells/well) the day before transfection. Cells were transfected with pCAGGS-T7 Cyt (0.5 μg), pT7MG-ZsGreen (0.5 μg), pCAGGS-NP (0.3 μg) and pCAGGS-L (0.6 μg) using Lipofectamine 2000 (2.5 μl/μg of DNA) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 0.6 µg pCAGGS-Empty in place of pCAGGS L as a negative control. After 5 h, the transfection mixture was replaced with fresh medium containing test compounds at 20 µM. At 72 h post-transfection, whole cell lysates were prepared to determine levels of ZsGreen expression. Briefly whole cell lysates were prepared with 0.2 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl) and ZsGreen levels were measured using a Synergy H4 Hybrid MultiMode Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, Vermont) using equivalent amounts of the clarified lysate. ZsGreen level were normalized for total cell protein in the lysate (Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Scientific). Mean values were normalized to vehicle (DMSO) treated control that was adjusted to 100%.

2.5.2. LCMV MG Assay

HEK293T cells were cultured on poly-L-lysine coated 12 well plates (3.0 x 105 cells/well) the day before transfection. Cells were transfected with plasmids pCAGGS T7 Cyt (0.5 µM), pT7MG-GFP (0.5 µM), pCAGGS NP (0.6 µM), and pCAGGS L (0.3 µM) using Lipofectamine 2000 (2.5 μl/μg of DNA) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 0.6 µg pCAGGS-Empty in place of pCAGGS L for Negative control. After 5 h, the transfection mixture was replaced with fresh medium containing test compounds at 20µm followed by 72 h incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2. At 72 h post-transfection, whole cell lysates were harvested to determine levels of GFP expression. Briefly whole cell lysates were prepared with 0.2 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl) and GFP levels were measured in equivalent amounts of the clarified lysate using a Synergy H4 reader. GFP level were normalized for total cell protein in the lysate (Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Scientific). Mean values were normalized to vehicle (DMSO) treated control that was adjusted to 100%.

2.6. Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution reagent (Promega, CAT#: G3580). This method determines the number of viable cells based on the level of formazan product converted from MTS [3-(4,5-dimethylthazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolim] by NADPH or NADH generated in living cells. Cells were seeded onto a 96 well optical plate at 3.0 x104 cells/well. After 20 h of incubation, compounds (at indicated concentrations in four replicates) or vehicle control were added to the cells in a final volume of 100 µl. At 48 h post compound treatment, CellTiter 96 AQueous One solution reagent (Promega) was added to each well and the plate incubated for 15 min at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader (SPECTRA max plus 384, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Values were normalized to vehicle control group (DMSO) that was assigned a value of 100%.

2.7. Determination of Compounds EC50 and CC50 in an LCMV Cell-Based Infection Assay

Cells were seeded onto a 96 well optical plate at 3.0 x104 cells/well and incubated for 16 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were infected with rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP at an MOI of 0.03 and treated with 2-fold serial dilutions of each compound (2-fold serial dilutions starting at 100 µM, four replicates for each compound and dilution concentration) for 48hrs prior CC50 and EC50 determinations. CellTiter 96 Aqueous solution was used to determine the CC50 with values normalized to vehicle treated control (0.2% DMSO) that was adjusted to 100%. To determine EC50 values, the cell titer 96 aqueous One Solution and media was aspirated, and the cells fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. GFP expression levels were determined by fluorescence using the Cytation 5 plate reader. Mean values were normalized to infected and vehicle (DMSO) treated control that was adjusted to 100%. EC50 and CC50 values were determined using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

2.8. Virus Multi-Step Growth Kinetics

A549 cells were seeded at 2.0 x 105 cells per well in a 12-well plate and next day infected with rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP an MOI of 0.03. After 90 minutes adsorption, the inoculum was removed and cells treated with VC (0.5% DMSO) or FLN (50 µM) or Rib (100 µM) as a positive control. Tissue culture supernatants (TCS) were collected at 24, 48 and 72 hpi. At the experimental endpoint (72 hpi) cells were stained with Hoechst dye solution. Live cell images were captured using a Keyence All-in-One Fluorescence Microscope BZ-X710 series. Cells were washed and RNA isolated using TRI Reagent (TR 118, Molecular Research Centre, Cincinnati, OH, USA). The titers of the TCS were determined by FFA using Vero E6 cells (four replicates) with values presented as mean ± SD. Data was plotted using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

2.9. RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR was done as described [

23]. RNA was isolated using TRI Reagent according to manufacturer’s instruction, the isolated RNA was resuspended in RNA storage Solution (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA. AM 7000) and quantified using NanoDrop™ 2000 Spectrophotometer (ND-2000 Thermo Scientific™) RNA (1 µg) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the SuperScript IV first-strand synthesis system (18091050, Life Technologies). Powerup SYBR (A25742, Life Technologies) was used to amplify LCMV NP and the housekeeping gene

GAPDH using the following primers: NP forward (F): 5′ CAGAAATGTTGATGCTGGACTGC-3′ and NP reverse (R): 5′-CAGACCTTGGCTTGCTTTACACAG-3′;

GAPDH F: 5′-CATGAGAAGTATGACAACAGCC-3′ and GAPDH R: 5′-TGAGTCCTTCCACGATACC-3′.

2.10. Time of Addition Assay

A549 cells were seeded at 3x104 cells per 96 well (black walled optical) plates (353219, Falcon) and grown for 16 h at 37oC and 5% CO2. Cells were treated with VC (0.25%DMSO), FLN (50 µM), F3406 (5 µM) (four replicates for each treatment) starting 2 h prior infection or 2 h post-infection with the single cycle infectious rARMΔGPC/ZsG-P2A-NP (MOI of 1.0) which eliminated the need for NH4Cl treatment to prevent the confounding factor introduced by multiple rounds of infection. At 24 hpi cells were fixed with 4% PFA and ZsGreen expression levels were measured using BioTek Cytation 5 Imaging Reader (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara CA).

2.11. Budding Assay

Budding Assay using Z-Gaussia Luciferase based assay (LASV-Z-GLuc plasmid) [

53]. Briefly 293T cells (1.75 × 10

5 cells/M12-well) were transfected with 0.5 μg of pC.LASV-Z_Gluc or pC.LASV-Z-G2A-GLuc (mutant control) or pCAGGS-Empty (pC-E) using Lipofectamine 2000. After 5 h transfection, cells were washed three times and treated with FLN (50µM), VC and Ribavirin (100µM). After 48 h of treatment cell culture supernatants (CCS) containing virus-like particle (VLP) and cells were collected. CCS samples were clarified from cell debris by centrifugation (13000rpm/4 °C/10 min) and aliquots (20 µl each) from CCS samples were added to 96-well black plates (VWR, West Chester, PA, USA), and 50 µl of SteadyGlo luciferase reagent (Promega) was added to each well. Cells lysates were prepared using 250 µl of lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 62.5 mM EDTA, 0.4% sodium deoxycholate). The Lysate was clarified from cell debris by centrifugation (13000rpm/4 °C/10 min). GLuc activity in Z-containing VLP and whole cell lysates (WCL) was determined using Steady-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, US) according to manufacturer’s protocol using the Berthold Centro LB 960 luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Oak Ridge, TN, USA). The GLuc activity in CCS and WCL served as a surrogate for Z protein levels. Z budding efficiency (in %) was determined by the ratio VLP-associated GLuc levels (Z

VLP) and total GLuc levels (Z

VLP + Z

WCL) times 100.

2.12. GPC-Mediated Cell Fusion Assay

HEK293T cells were seeded onto poly-L-lysine coated wells in a 24-well plate (1.25 x 105 cells/well). Following an incubation period of 20 hours, cells were transfected with plasmids expressing LCMV GPC together with a plasmid expressing GFP, or with a plasmid expressing GFP alone using Lipofectamine 3000. At 18 hours post-transfection, the transfection mixture was removed and replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS and FLN (50 µM) or VC. At 5 h post-treatment, 0.5 mL of acidic (pH 5.0), or neutral (pH 7.2) DMEM was added to the cells and incubated for 15 minutes (370C/5%CO2), washed once with DMEM +10% FBS, and 0.5 mL of DMEM containing 10% FBS and FLN (50 µM) or VC was added per well. Cells were fixed after 2 h with 4% PFA and stained with DAPI. Syncytium formation was visualized and imaged using a Keyence BZ-X710 microscope to record the GFP expression.

2.13. Virucidal Assay

rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP (105 FFU) was treated with FLN at 1, 50 and 100 µM, or VC, for 30 min at room temperature. The Infectivity of the virus after treatment was determined by FFA using Vero E6 cells. Infected cells were identified based on their GFP expression and presented as mean ± SD (four replicates). The counts were normalized (%) to vehicle treated infected cells which was set at 100%.

2.14. Epifluorescence

Images were collected using the Keyence BZ-X710 microscope. Images were transferred to a laptop for data processing purposes. Microsoft PowerPoint 2019 was used to assemble and arrange the images, with each one being imported separately and arranged in a cohesive manner within its respective composite. The canvas size was adjusted to ensure a harmonious layout.

2.15. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software v.10.2.3 (403) (GraphPad).

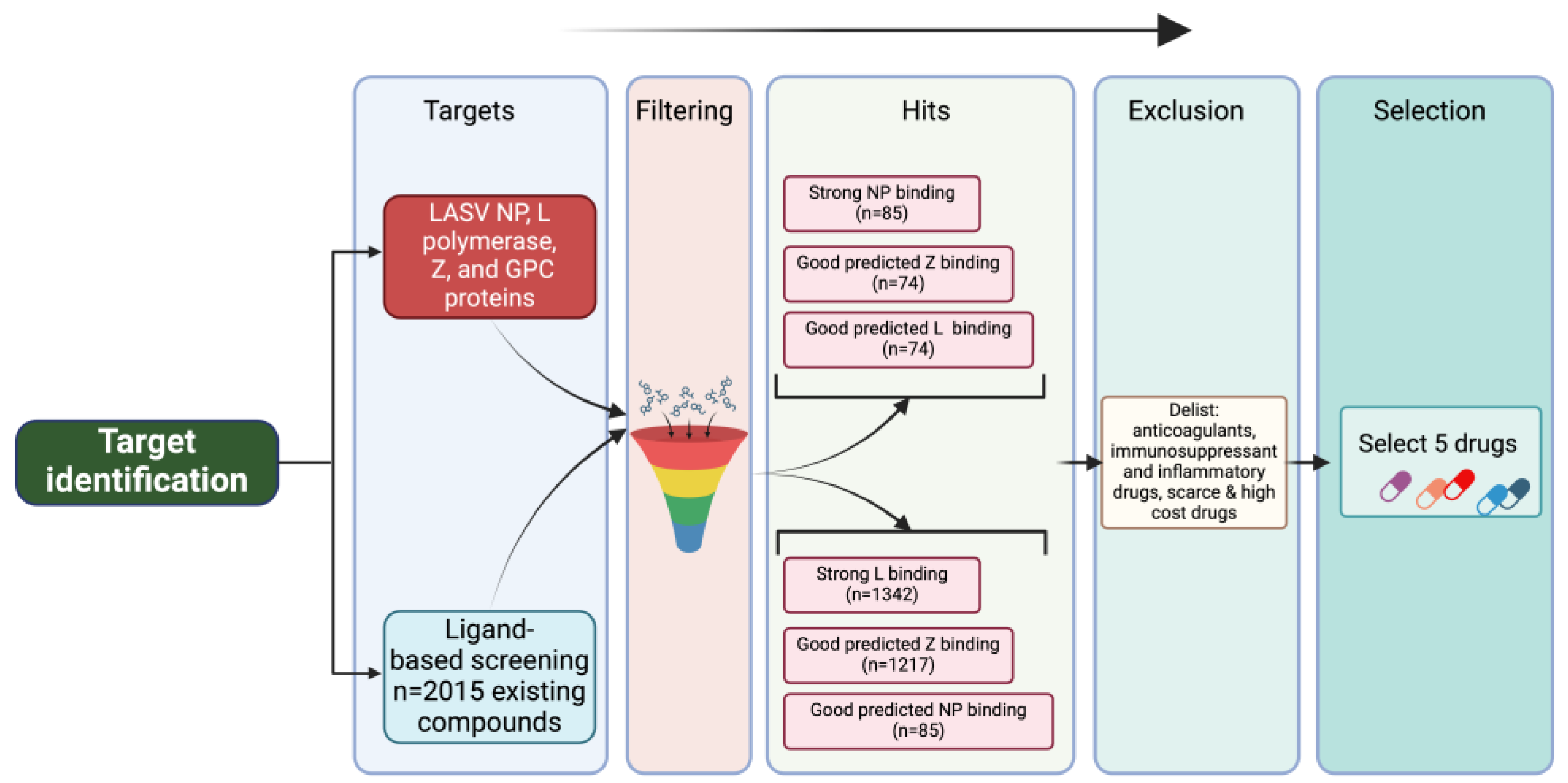

3. Results

3.1. In Silico Docking Screen to Identify Candidate Drug Inhibitors of LASV Multiplication

To identify potential anti-LASV compounds, we conducted an in silico screen of 2015 approved drugs potentially binding to LASV protein (polymerase, matrix Z, nucleoprotein) structures (

Figure 1). Our in silico docking screen identified five [

5] approved drugs with favorable docking scores (

Table 1 and

Table 2). The five approved drugs were further subjected to in vitro validations.

Table 1: The binding affinities (expressed as Gibbs free energy changes, ΔG) of selected hits. Five drugs were selected by ranking the binding energy (ΔG) of 2015 existing drugs obtained from Drugbank to LASV target proteins. Molecular docking simulations were implemented, in four replicates, on a Linux platform using AutoDockVina and associated tools after validation of docking protocols. Binding free energy values (kcal/mol ± SD) were ranked, and Dexamethasone (DEX), Flunarizine (FLN), Tadalafil (TAD), Egorciferol (Vit D) and Mefloquine (MEF) were selected based on the potency of its binding activities to the Polymerase, Z-Protein and Nucleoprotein of LASV.

Table 2. Predicted interacting amino acid residues in LASV proteins targeted by selected drugs. Using Discovery Studio, interactions were analyzed to identify specific residues in the Polymerase, Z-preotein, and Nucleoprotein proteins of LASV that are likely to interact and serve as binding sites for the selected drugs: Dexamethasone (DEX), Flunarizine (FLN), Tadalafil (TAD), Egorciferol (Vit D) and Mefloquine (MEF). These residues represent potential targets for therapeutic intervention, as they suggest where each drug may exert its effect on viral structure or function. The findings are particularly useful in understanding drug-protein interactions and advancing LASV treatment strategies.

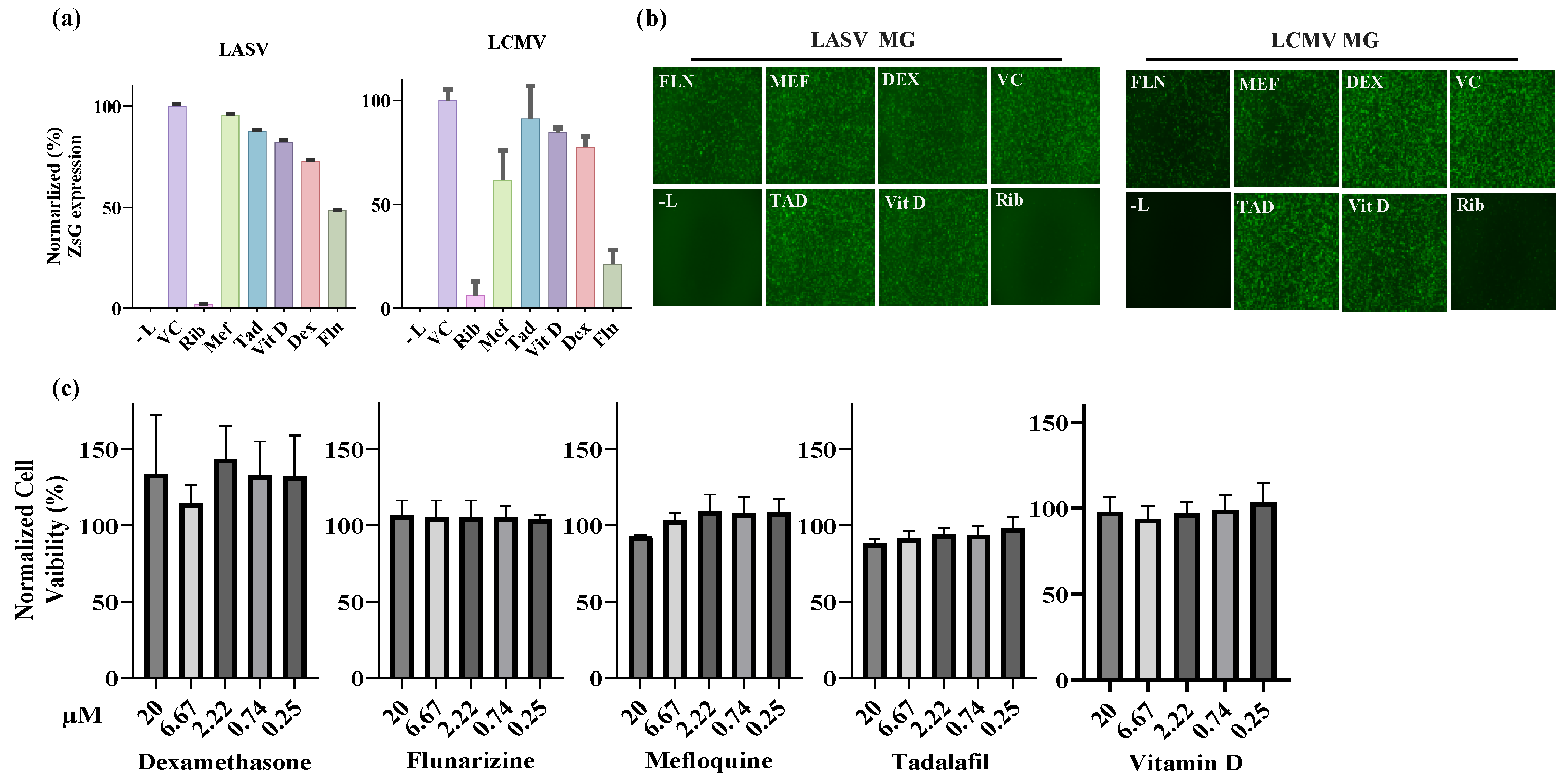

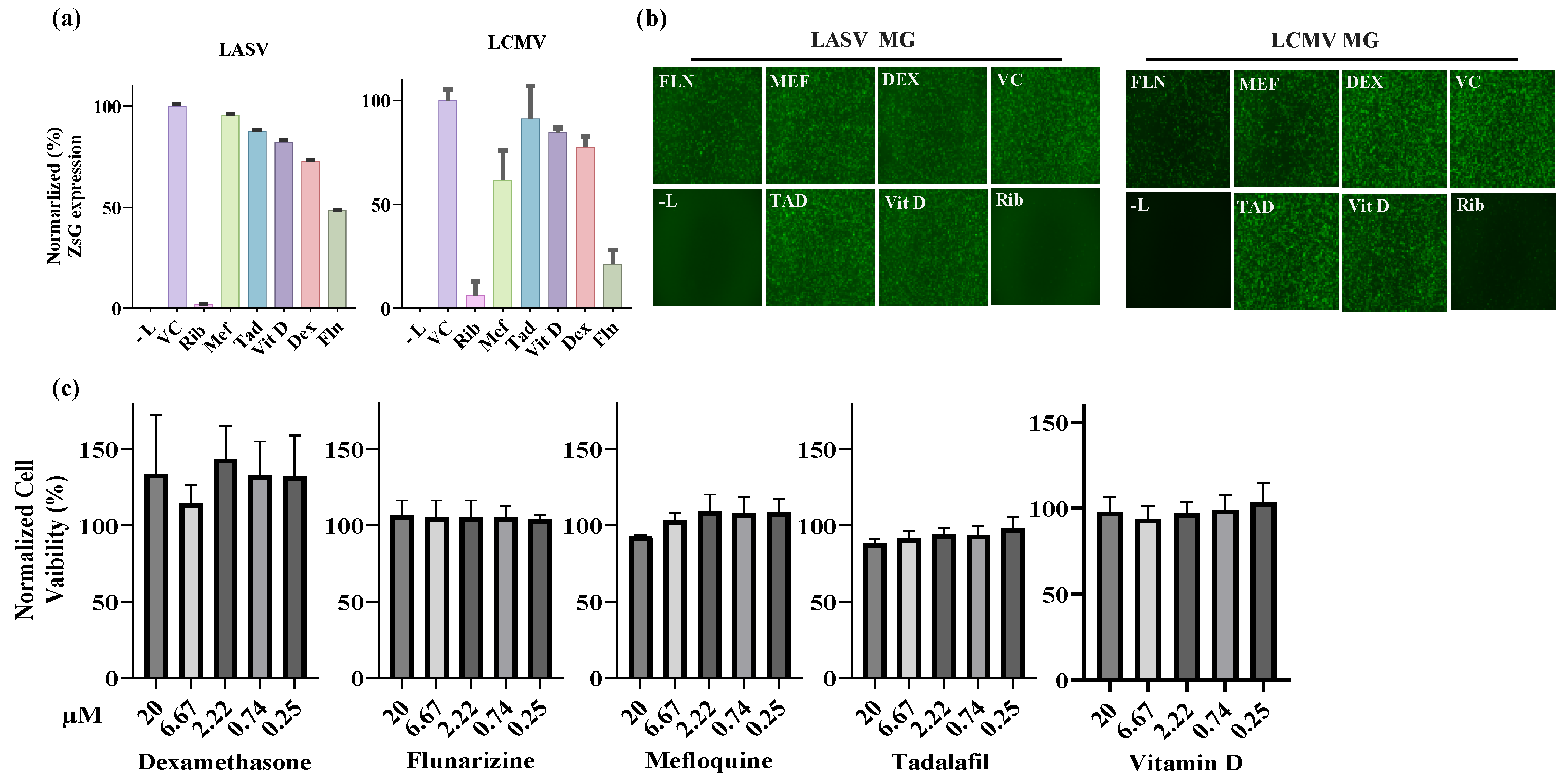

3.2. Effect of Selected Hits on the Activity of LASV and LCMV vRNPs

Based on the parameters of the in silico docking screen we selected MEF, TAD, DEX, Vit D, and FLN as the top candidate hits for testing their ability to inhibit the activity of LASV and the closely related mammarenavirus LCMV vRNPs. For this we used described LASV [

52] and LCMV [

52] cell-based minigenome (MG) assays. These MG systems recapitulate the steps involved in LASV and LCMV RNA synthesis using an intracellular reconstituted vRNP that directs expression of a reporter gene (ZsGreen for LASV-MG and GFP for LCMV-MG) whose expression levels serve as an accurate surrogate of the vRNP activity. Intracellular reconstitution of LASV and LCMV vRNP requires co-expression of the corresponding viral L and NP proteins, as well as a plasmid to launch intracellular synthesis of the viral MG vRNA. In these experiments, expression levels of the MG reporter serve as a comprehensive measurement of LASV and LCMV MG replication, transcription, and translation of the MG encoded reporter gene. We first assessed the effect of each compound on the viability of HEK293T cells and found that none of the 5 tested compounds had noticeable effects on cell viability when used up to 20 µM, the concentration we selected for the cell-based MG assay (

Figure 2C). We then transfected HEK293T cells with the components of the LASV or LCMV MG system and treated them with the indicated compounds (20 µM) or vehicle control (VC), or ribavirin (Rib: 100 µM), a validated inhibitor of LASV and LCMV replication (

Figure 2A). At 48 h post-transfection whole cell lysates were prepared and expression levels of ZsGreen (LASV-MG) and GFP (LCMV-MG) determined and normalized to the amount of total protein in the corresponding sample. Mean values (four replicates) of reporter gene expression were normalized by assigning the value of 100% to vehicle control (VC) treated control sample. In parallel, cells transfected with the same combination of plasmids were fixed with 4% PFA at 48 h post-transfection and representative fields imaged using Keyence BZ-X710 imaging system (

Figure 2B). Compared to VC treated cells, we observed a significant (~ 50%) reduction in LASV MG directed ZsGreen expression levels in cells treated with FLN. We observed a much lower effect on LASV MG activity in cells treated with any of the other selected hits, dexamethasone (~ 28% reduction), VIT D2 (~18% reduction), TAD (~ 12% reduction) and MEF (5% reduction) (

Figure 2A). We observed a similar pattern of compound mediated inhibition of the LCMV MG activity, with FLN exhibiting the strongest inhibitory effect (

Figure 2A).

3.3. Dose-Dependent Inhibitory Effect of Selected Drugs on LCMV Multiplication in Cultured Cells

Selected hits from the in silico docking screen exhibited similar activity patterns against LASV and LCMV vRNP, suggesting that these drugs may have a similar inhibitory effect on multiplication of LASV and LCMV. We therefore used the BSL2 agent LCMV to test the compounds in a cell-based infection assay avoiding the need of the highest BSL4 containment required for the use of live LASV [

54].

We determined the dose-dependent effect of MEF, TAD, DEX, Vit D, and FLN on rLCMV/GFP multiplication in A549 cells. For this, we infected A549 cells with rLCMV/GFP (MOI = 0.05) and treated them with 3-fold serial dilutions of each compound. At 48 hours post-infection (hpi) CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Reagent was added to the cells and after incubation for 35 min (37°C and 5% CO

2) absorbance values were collected, cells were then fix (4% PFA/PBS) and GFP expression levels measured using a fluorescent plate reader (

Figure 3). Normalized cell viability values and GFP expression levels were used to determine drugs CC

50 and EC

50 values using GraphPad Prism software v10 (

Figure 3). Consistent with the cell-based MG assay results, FLN was the drug with the best antiviral profile in the LCMV cell-based infection assay with EC

50 of 27.91µM and a CC

50 of above 100 µM. MEF exhibited a moderated anti-LCMV activity in Vero cells (EC

50 of 15.51 µM) but due to toxicity (CC

50 of 29.12 µM) resulted in a very low selective index (SI) of 1.87. DEX, Vit D and TAD had minimal toxicity on Vero cells but exhibited very poor inhibitory activity on LCMV multiplication.

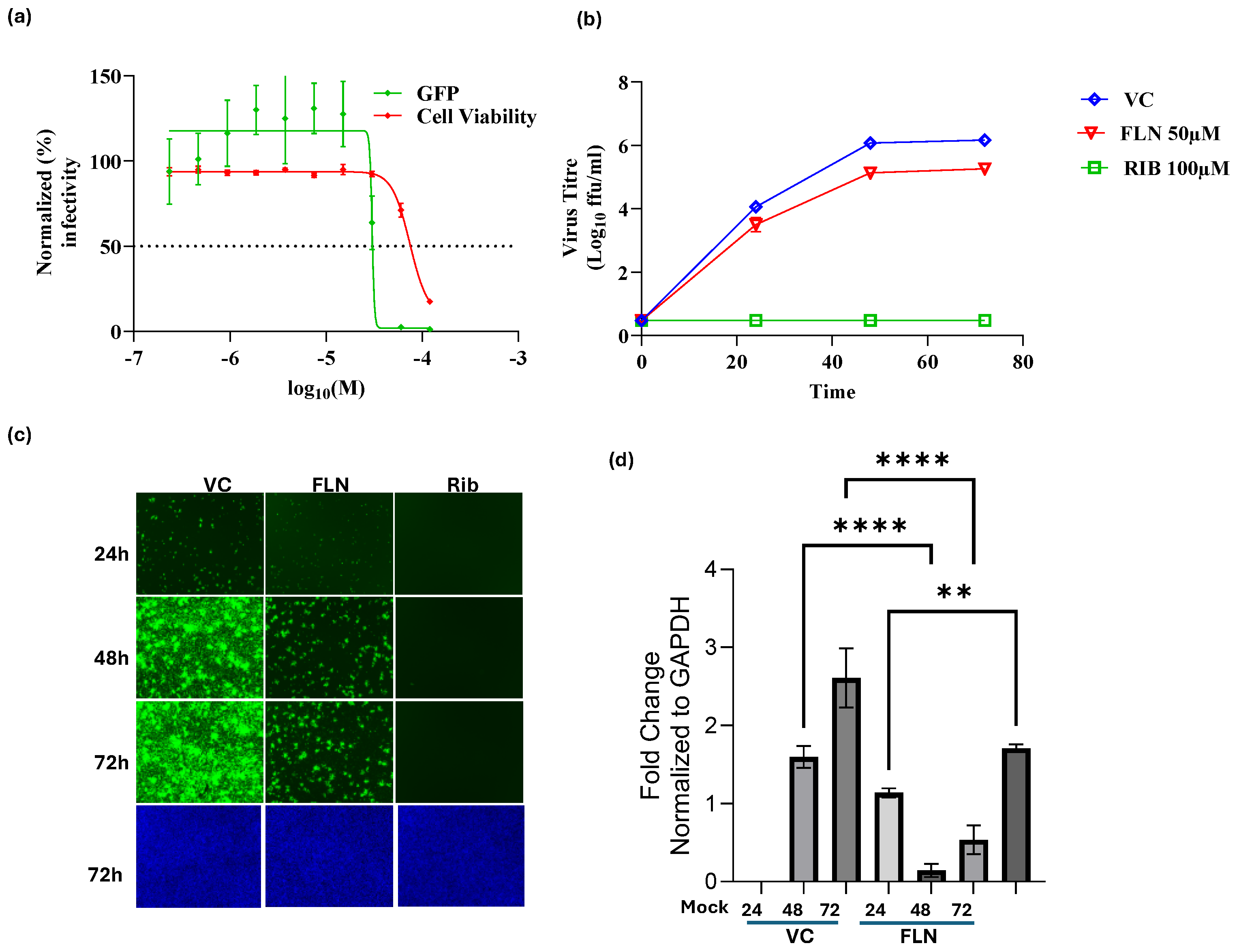

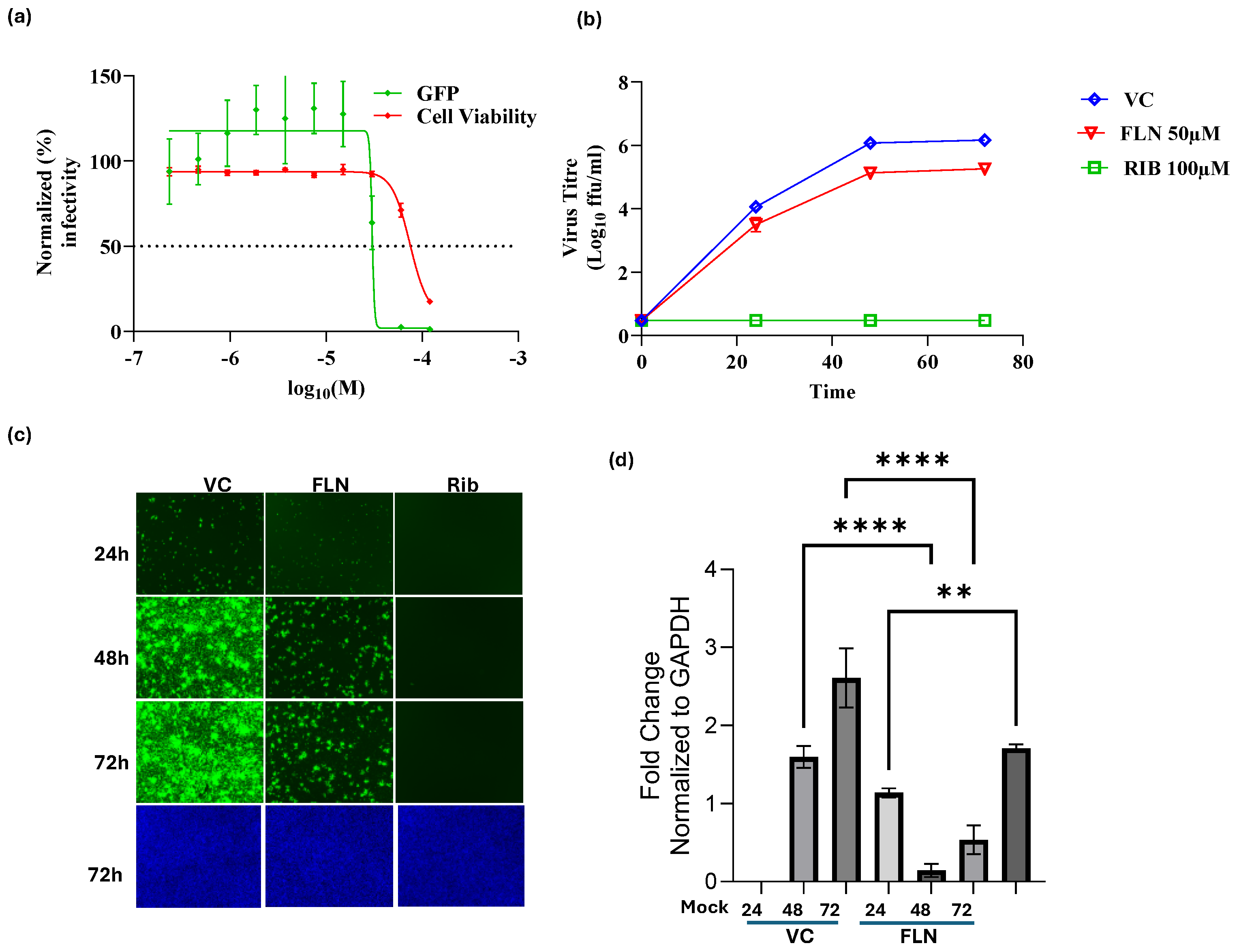

3.4. Characterization of the Effect FLN on LCMV Multi-Step Growth Kinetics in A549 Cells

FLN exhibited the highest potency among all the compounds assessed, warranting further investigation. We first examined the dose-dependent effect of FLN on LCMV multiplication (

Figure 4A) in A549 cells.

A549 cells were seeded (3.0 x 10

4 cells/well) in 96-well plate and 16 h later infected with rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP at MOI of 0.03. After 90 min adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and infected cells treated with the indicated concentrations (different doses) of FLN (four replicates per concentration). At 72 hpi, cells were fixed with 4% PFA and stained with DAPI. GFP expression levels and DAPI staining were used to determine virus infectivity and cell viability, respectively. Values correspond to the mean ± SD of four replicates. Levels of GFP expression and DAPI staining were normalized assigning a value of 100% to GFP expression levels and DAPI staining VC-treated and infected cells. Normalized values were used to determine the EC

50 and CC

50. FLN had a EC

50 of 30.11µM, CC

50 of 74.3µM and an SI of 2.5. We next examined the effect of FLN on production of infectious viral progeny (

Figure 4B) and virus cell propagation (

Figure 4C) in A549 following infection with rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP at MOI of 0.05. We used treatment with Rib (100 µM) as a benchmark for a validated inhibitor of mammarenavirus multiplication. At the indicated hpi cell culture supernatants (CCS) were collected and the media replaced with FluoroBrite-DMEM, and cells stained with Hoechst. Virus titers in CCS samples were determined using a FFA and Vero E6 as cell substrate (

Figure 4B). Representative images of each sample were obtained using live cell fluorescent microscopy (

Figure 4C). After images were collected, total cellular RNA was isolated from each sample and levels of LCMV NP RNA determined by RT-qPCR (

Figure 4D) for each treatment and normalized to levels of GAPDH. Relative Quantification was calculated using the untreated sample as the calibrator and the mean ± SD were plotted with statistical significance of P < 0.05. FLN (50 µM) caused 1 log reduction in virus peak titers (

Figure 4B) that correlated with reduced virus cell propagation (

Figure 4C), as well as levels of viral RNA as determined by RT-qPCR (

Figure 4D).

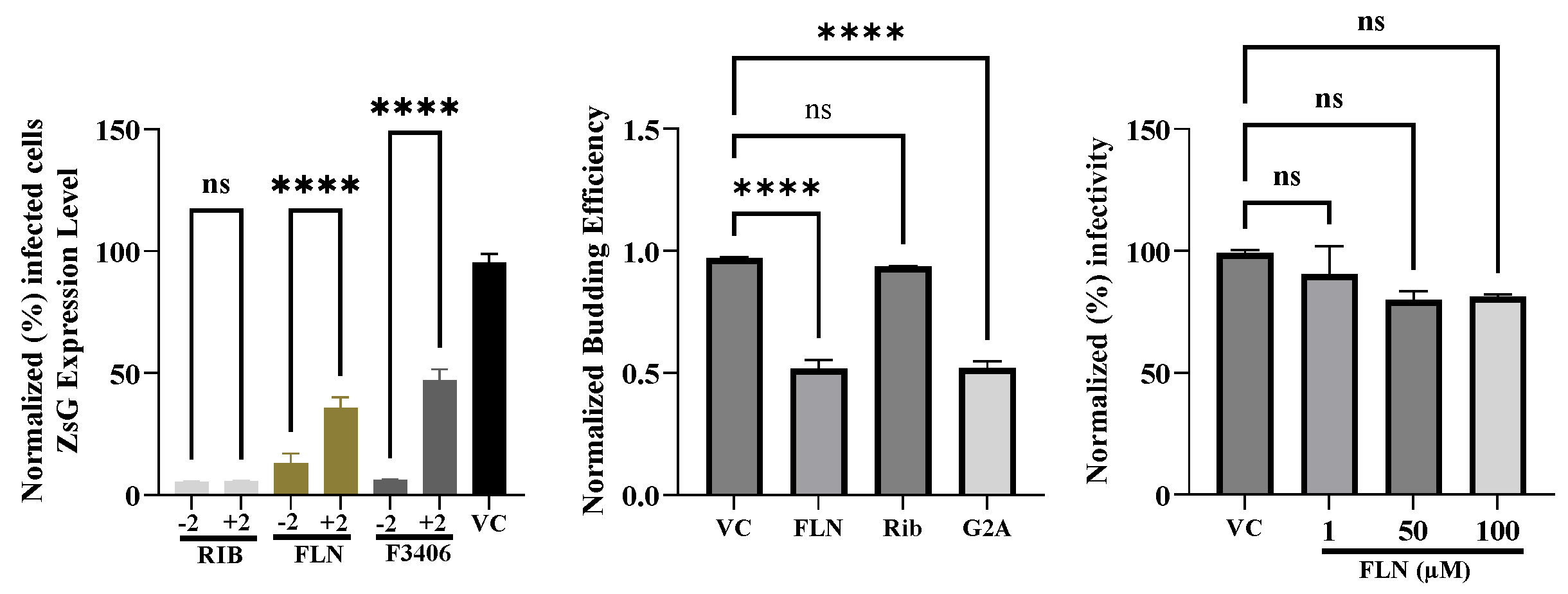

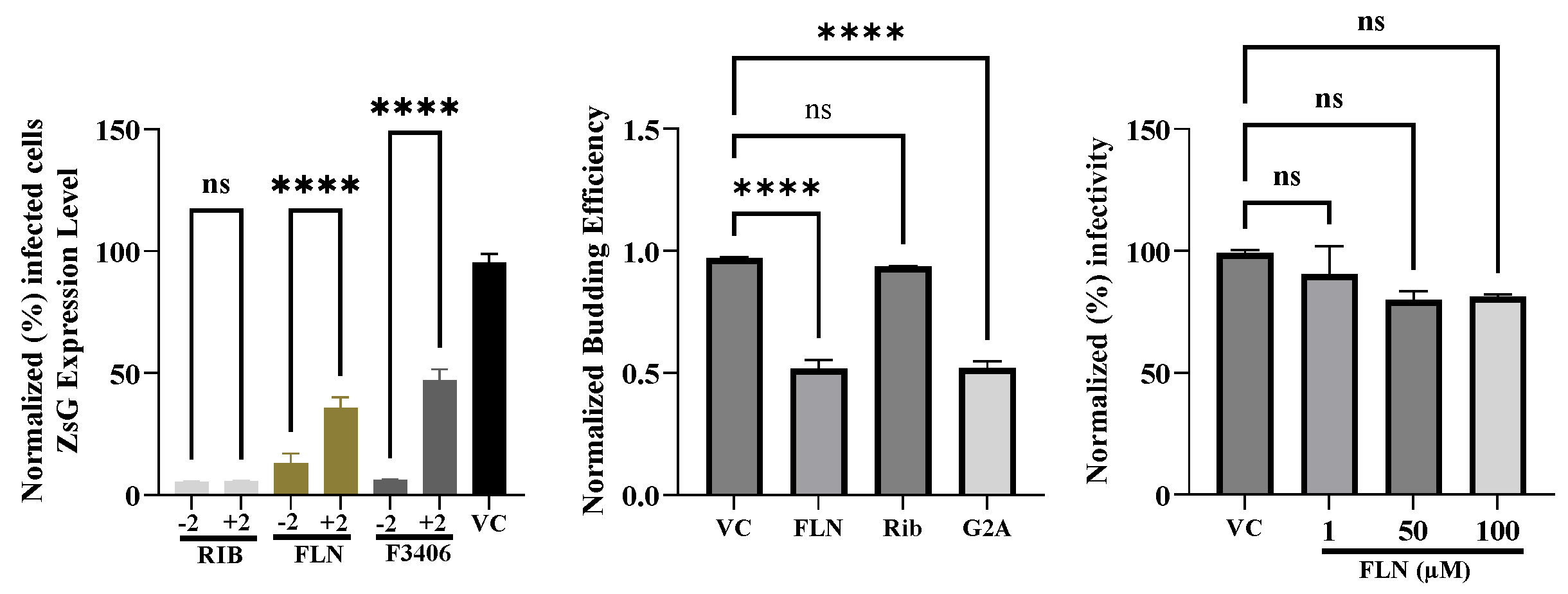

3.5. Effect of FLN Treatment on Different Steps of LCMV Life Cycle

To gain further insights about the mechanism by which FLN exerted its antiviral activity against LCMV, we examined which steps of the virus life cycle were affected in the presence of FLN. To examine whether FLN affected a cell entry, or post-entry, step of the LCMV life cycle we conducted a time of addition experiment using the single-cycle infectious rLCMV∆GPC/ZsG to prevent the confounding factor introduced by multiple rounds of infection (

Figure 5A). A549 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate (3.0 x 10

4 cells/well), and after overnight incubation treated with FLN (50 µM), or VC, starting 2 h prior (-2) or 2 h post (+2) infection (MOI of 1) with rARMΔGPC/ZsG-P2A-NP. ZsG expression level were determined at 48 hpi and mean values normalized to VC treated cells that were assigned a value of 100%. Rib and the LCMV cell entry inhibitor F3406 (5 µM) were used as controls. The results showed that FLN exerted a much stronger inhibitory effect on ZsG expression levels when added 2 h prior infection with rARMΔGPC/ZsG-P2A-NP. The mammarenavirus matrix protein Z has been shown to be the main driving force of virion budding [

50]. To assess whether FLN affected the Z-mediated budding process we used a published cell-based Z budding assay where the activity of the Gaussia luciferase (Gluc) reporter gene serves as a surrogate of Z budding activity [

53]. We transfected HEK293T cells with a plasmid expressing LASV Z-GLuc and treated them with FLN (50 µM) or vehicle control and 48 h later measured levels of GLuc activity associated with VLPs present in CCS, and in WCLs (

Figure 5B). Mutation G2A in Z protein has been shown to dramatically affect its budding activity [

55]. We therefore used transfection with a plasmid expressing LASV Z(G2A)-GLuc, and treatment with Rib, known not to inhibit Z budding, as controls. Budding efficiency (in %) was determined by the ratio VLP-associated GLuc levels (Z

VLP) and total GLuc levels (Z

VLP + Z

WCL) X 100. FLN had a significant inhibitory effect (50% reduction, ***

p < 0.0001) on LASV Z-mediated budding. We also examined whether DDD85646 exerted any virucidal activity on infectious LCMV virions. For this, rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP (1x10

5 ffu in a volume of 1ml) was treated with FLN at 1µM, 50 µM and 100 µM for 30 min at room temperature. After treatment samples were diluted 100-fold, resulting in FLN concentrations lacking anti-LCMV activity, and virus infectivity determined by FFA. Treatment with 50 or 100 µM FLN, which caused > 1 log reduction in production of LCMV infectious progeny (

Figure 5B) did not significantly affect virion infectivity compared to VC treated sample (

p = 0.0965) (

Figure 5C).

3.6. Effect of FLN on LCMV GPC Mediated Cell Fusion

Mammarenaviruses enter cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis [

56]. In the acidic environment of the endosome, GP2 mediates a pH-dependent fusion event between viral and cellular membranes to complete the cell entry process resulting in the release of the vRNP into the cell cytoplasm where vRNP directs replication and transcription of the viral genome. To examine whether FLN interfered with the GP2 mediated fusion event, we transfected HEK293T cells with plasmids expressing LCMV (pC-LCMV-GPC) or an empty plasmid (pC-E) as control, together with a plasmid expressing GFP (pC-GFP) (

Figure 6). At 18 h post transfection, cells were treated with VC or FLN (50 µM). After 5 h treatment with FLN, cells were exposed to acidic (pH 5.), or neutral (pH 7.2), medium for 15 min, followed by returning cells to regular medium (pH 7.2) and 2 h later cells were fixed with 4% PFA, stained with DAPI and syncytium formation visualized based on GFP expression. Cells transfected with plasmids expressing LCMV GPC and exposed to pH 5 exhibited very strong fusion activity as determined by syncytial formation revealed by the pattern of GFP expression. In contrast, treatment with FLN resulted in abrogation of GP2 mediated fusion upon exposure to low pH.

3.7. Effect of FLN on Multiplication of JUNV

To examine whether FLN exhibited a broad-spectrum anti-mammareanvirus activity, we examined its effect on multiplication of the New World mammarenavirus JUNV, which is genetically distantly related to the Old World mammarenaviruses LCMV and LASV. For this experiment we used a tri-segmented version of the live-attenuated vaccine strain Candid#1 (r3Can) of JUNV expressing the GFP reporter gene (r3Can-GFP). This allowed us to avoid the need of BSL4 biocontainment required for the use of live forms of pathogenic strains of JUNV. FLN (50 µM) inhibited multiplication of r3Can-GFP to similar levels to that we observed with LCMV (

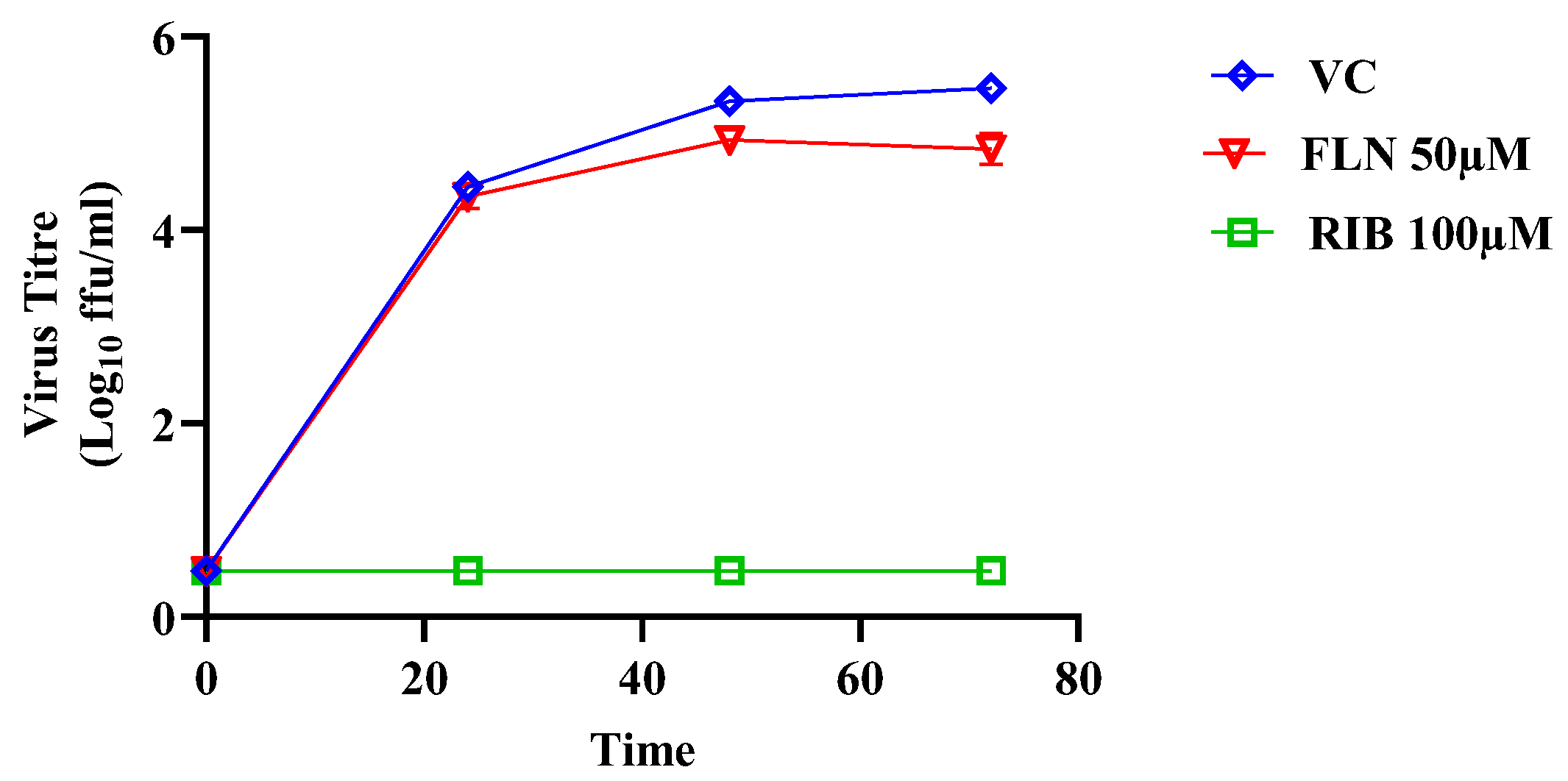

Figure 7) (> 1 log reduction in virus peak titers compared to VC treated and infected cells).

3.8. Inhibitory Effect of Selected Calcium Channel Inhibitors on LCMV Multiplication in A549 Cells

FLN has been shown to block the activity of low voltage-activated T-type calcium channels. To assess whether calcium channel blockade was associated with the anti-LCMV activity of FLN, we examined the effect on LCMV multiplication of other selected calcium channel blockers including the combined L-/T-type (verapamil and nickel chloride) and L-type (nifedipine and gabapentin) calcium channel blockers (

Figure 8).

3.9. Effect of Serum on the Anti-Mammarenaviral Activity of FLN

More than 99% of FLN can be found bound to plasma proteins [

57,

58], raising the question whether the full magnitude of FLN’s anti-mammarenaviral activity was masked in our experiments done in the presence of 10% FBS. To address this issue, we compared the effect of FLN on the multi-step growth kinetics of LCMV in the presence (10%) or absence of FBS. We found that FLN anti-LCMV activity was 100-fold higher in the absence than in the presence of 10% serum (

Figure 9).

4. Discussion

The current standard of care for LF cases is limited, besides supportive care, to an off-label use of the nucleoside analog Rib, for which efficacy remains controversial [

9,

12]. Significant efforts are being dedicated to the discovery of antiviral drugs against LASV, which has resulted in the identification of several candidates with potent activity in cell-based infection assays. Notably, the broad-spectrum inhibitor favipiravir (T-705) [

59,

60] and the LASV GPC-mediated fusion inhibitor ST-193 [

61] have shown promising results in animal models of arenaviral hemorrhagic fever (HF) disease, and the ST-193 analog LHF-535 is in phase I clinical trials [

28]. Nevertheless, the development of additional antivirals against LASV can facilitate the implementation of combination therapy against LF, an approach known to counteract the emergence of drug-resistant variants often observed with mono therapy strategies [

62]. Limited market opportunities pose significant obstacles for the development and licensing of new drugs against emerging viral diseases endemic to countries with limited resources. Drug repurposing strategies that can significantly reduce the time required to advance a candidate antiviral drug into the clinic by reducing the labor and resource-intensive efforts involved in preclinical optimization of newly discovered hits in traditional drug-discovery approaches [

63,

64]. Moreover, information obtained from drug repurposing efforts can reveal novel insights on virus biology by identifying novel pathways and host cell factors involved in different steps of the virus life cycle, which could uncover new targets and therapeutics. In the present work we used an in silico docking approach to screen 2015 existing drugs for candidates predicted to bind and functionally affect LASV proteins, as well as two host cell proteins, α-dystroglycan and lysosomal associated membrane protein, known to play critical roles in LASV cell entry. We found that DEX, TAD, MEF, Vit D, and FLN had in silico docking parameters that supported their potential antiviral activity against LASV via targeting components of the LASV vRNP. We evaluated these candidates for their antiviral activity in cell-based MG and cell-based infection assays.

DEX has been reported to have some benefit in the treatment of LF, potentially due to its ability to modulate inflammatory-mediated tissue damage associated with LF [

54]. TAD, a phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitor, has been found to bind to the viral RNA dependent RNA Polymerase of SARS-CoV-2 [

65]. MEF has been suggested to inhibit cell entry of MPOX virus [

66]. The role of Vit D in the immune system has come under increasing scrutiny, with research indicating its potential to protect against bacterial and viral invaders via stimulation of production of cytokines, antimicrobial proteins, and pattern recognition receptors, all of which are important for innate immunity. Some studies have suggested that Vit D may offer protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection and be beneficial in the treatment of viral respiratory tract infections [

67]. However, we found that DEX, TAD, MEF and Vit D had minimal inhibitory activities in both LASV and LCMV cell-based MG assays, as well as in LCMV cell-based infection assays. In contrast, the neuroleptic FLN, commonly prescribed in many countries across the world for migraines and vertigo, significantly inhibited LASV and LCMV vRNP activity in cell-based MG assays, and LCMV multiplication in cell-based infection assay.

FLN is classified as a Ca

2+ antagonist that blocks influx of extracellular Ca2+, whereas it exerts minimal antagonistic action against dopamine receptors [

68](Pietschmann, 2017). Ca2+ metabolism and signaling having been implicated in different steps of the life cycle of different viruses including Ebola and Marburg viruses [

69], and importantly the mammarenaviruses LASV and JUNV [

69]. Notably, FLN has been shown to inhibit hepatitis C virus cell entry by inhibiting HCV E1 mediated pH-dependent fusion [

30,

68,

70], and cell entry inhibitors that target viral components or cellular factors have emerged as an interesting class of inhibitors in HCV [

71] , as their use in combination with direct acting antivirals targeting virus replication can prevent breakthrough of antiviral-resistant HCV [

72]. Our finding that other selected L-and T-type calcium channel blockers did not exhibit anti-LCMV activity suggests that FLN anti-mammarenaviral activity may not be related to its ability to block T-type calcium channels. FLN also exhibits antihistaminic activity via blocking H1 histamine receptors [

73,

74], and several antihistaminic drugs have been shown to exert antiviral activity [

68,

75]. However, the strong H1 histamine receptor clemizole does not exhibit anti-mammarenavirus activity [

76] . FLN has been shown to bind calmodulin, which could interfere with the role of calmodulin in low pH induced fusion of late endosomes and lysosomes [

43]. It is plausible that the calmodulin biding properties of FLN contributed to its inhibitory effect on GP2-mediated, pH-induced fusion event required for mammarenavirus cell entry.

FLN has not received FDA approval, but its safety is strongly supported by its current use in many countries to treat migraines and vertigo. Moreover, the characterization of novel FLN analogs focused on structural changes in the allylic element and the adjacent arene substituent, has resulted in the identification of p-methoxy-FLN with an IC50 ca. 8-fold lower than FLN against HCV, and a SI 335, which is a 8.8-fold improvement relative to FLN [

70]. These findings together with our results support the interest in exploring its repurposing as a candidate drug to treat LASV, and other human pathogenic mammarenavirus, infections.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, C.A.O., I.C.U., and J.C.T.; methodology, C.A.O., I.C.U.,F.C.E.,B.C., N.O., and J.C.T.; software, C.A.O., F.C.E., I.E., and H.W.; validation, C.A.O., I.C.U., and B.C.; formal analysis, C.A.O., H.W., I.C.U., and J.C.T.; investigation, C.A.O.; resources, I.C.U., and J.C.T.; data curation, C.A.O., M.A., I.O., and C.B.O .; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.O., I.C.U., F.C.E., and J.C.T.; writing—review and editing, C.A.O., H.W., B.C., I.C.U., N.O., I.E., and J.C.T.; visualization, C.A.O.; supervision, I.C.U and J.C.T.; project administration, C.A.O and I.C.U.; funding acquisition, I.C.U., and J.C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. This is manuscript 30296 from The Scripps Research Institute.

Funding

This research was supported by TETFUND/NRF, grant number TETFund/DR&D/CE/NRF/STI/24/Vol1, and by NIH/NIAID grants AI125626 and AI128556.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Buba MI, Dalhat MM, Nguku PM, Waziri N, Mohammad JO, Bomoi IM, Onyiah AP, Onwujei J, Balogun MS, Bashorun AT, Nsubuga P, Nasidi A. 2018. Mortality Among Confirmed Lassa Fever Cases During the 2015–2016 Outbreak in Nigeria. Am J Public Health 108:262–264. [CrossRef]

- Fichet-Calvet E, Rogers DJ. 2009. Risk Maps of Lassa Fever in West Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3:e388. [CrossRef]

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. https://ncdc.gov.ng/diseases/sitreps/?cat=5&name=An%20update%20of%20Lassa%20fever%20outbreak%20in%20Nigeria. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- Richmond JK, Baglole DJ. 2003. Lassa fever: epidemiology, clinical features, and social consequences. BMJ 327:1271–1275. [CrossRef]

- Yun NE, Walker DH. 2012. Pathogenesis of Lassa Fever. Viruses 4:2031–2048. [CrossRef]

- Mehand MS, Al-Shorbaji F, Millett P, Murgue B. 2018. The WHO R&D Blueprint: 2018 review of emerging infectious diseases requiring urgent research and development efforts. Antiviral Research 159:63–67. [CrossRef]

- Prioritizing diseases for research and development in emergency contexts. https://www.who.int/activities/prioritizing-diseases-for-research-and-development-in-emergency-contexts. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- Sweileh WM. 2017. Global research trends of World Health Organization’s top eight emerging pathogens. Global Health 13:9. [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt KA, Mischlinger J, Jordan S, Groger M, Günther S, Ramharter M. 2019. Ribavirin for the treatment of Lassa fever: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 87:15–20. [CrossRef]

- Garry RF. 2023. Lassa fever — the road ahead. Nat Rev Microbiol 21:87–96.

- Bausch DG, Hadi CM, Khan SH, Lertora JJL. 2010. Review of the Literature and Proposed Guidelines for the Use of Oral Ribavirin as Postexposure Prophylaxis for Lassa Fever. Clinical Infectious Diseases 51:1435–1441. [CrossRef]

- Salam AP, Cheng V, Edwards T, Olliaro P, Sterne J, Horby P. 2021. Time to reconsider the role of ribavirin in Lassa fever. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 15:e0009522. [CrossRef]

- Buchmeier MJ, De La Torre JC, Peters CJ. 2007. Fields virologyArenaviridae: the viruses and their replication, 4th edn. Lippincott-Raven Philadelphia.

- Klitting R, Mehta SB, Oguzie JU, Oluniyi PE, Pauthner MG, Siddle KJ, Andersen KG, Happi CT, Sabeti PC. 2023. Lassa Virus Genetics. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 440:23–65.

- Arenaviridae: the viruses and their replication – ScienceOpen. https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=4cfb6de1-1bb9-44e9-8e72-f49898d3007c. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- Radoshitzky SR, de la Torre JC. 2019. Human Pathogenic Arenaviruses (Arenaviridae), p. 507–517. In Encyclopedia of Virology. Elsevier.

- Acciani M, Alston JT, Zhao G, Reynolds H, Ali AM, Xu B, Brindley MA. 2017. Mutational Analysis of Lassa Virus Glycoprotein Highlights Regions Required for Alpha-Dystroglycan Utilization. J Virol 91:e00574-17. [CrossRef]

- Bederka LH, Bonhomme CJ, Ling EL, Buchmeier MJ. 2014. Arenavirus stable signal peptide is the keystone subunit for glycoprotein complex organization. mBio 5:e02063. [CrossRef]

- Jae LT, Raaben M, Herbert AS, Kuehne AI, Wirchnianski AS, Soh TK, Stubbs SH, Janssen H, Damme M, Saftig P, Whelan SP, Dye JM, Brummelkamp TR. 2014. Lassa virus entry requires a trigger-induced receptor switch. Science 344:1506–1510. [CrossRef]

- Burri DJ, da Palma JR, Kunz S, Pasquato A. 2012. Envelope Glycoprotein of Arenaviruses. Viruses 4:2162–2181.

- Keating PM, Schifano NP, Wei X, Kong MY, Lee J. 2024. pH-dependent conformational change within the Lassa virus transmembrane domain elicits efficient membrane fusion. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1866:184233.

- Hastie KM, Kimberlin CR, Zandonatti MA, MacRae IJ, Saphire EO. 2011. Structure of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein reveals a dsRNA-specific 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity essential for immune suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:2396–2401.

- Witwit H, Khafaji R, Salaniwal A, Kim AS, Cubitt B, Jackson N, Ye C, Weiss SR, Martinez-Sobrido L, de la Torre JC. 2024. Activation of protein kinase receptor (PKR) plays a pro-viral role in mammarenavirus-infected cells. Journal of Virology 98:e01883-23. [CrossRef]

- Capul AA, de la Torre JC, Buchmeier MJ. 2011. Conserved Residues in Lassa Fever Virus Z Protein Modulate Viral Infectivity at the Level of the Ribonucleoprotein. J Virol 85:3172–3178. [CrossRef]

- Wolff S, Ebihara H, Groseth A. 2013. Arenavirus Budding: A Common Pathway with Mechanistic Differences. Viruses 5:528–549. [CrossRef]

- Witwit H, Betancourt CA, Cubitt B, Khafaji R, Kowalski H, Jackson N, Ye C, Martinez-Sobrido L, de la Torre JC. 2024. Cellular N-Myristoyl Transferases Are Required for Mammarenavirus Multiplication. 9. Viruses 16:1362. [CrossRef]

- Joseph AA, Fasipe OJ, Joseph OA, Olatunji OA. 2022. Contemporary and emerging pharmacotherapeutic agents for the treatment of Lassa viral haemorrhagic fever disease. J Antimicrob Chemother 77:1525–1531. [CrossRef]

- Amberg SM, Snyder B, Vliet-Gregg PA, Tarcha EJ, Posakony J, Bedard KM, Heald AE. 2022. Safety and Pharmacokinetics of LHF-535, a Potential Treatment for Lassa Fever, in Healthy Adults. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 66:e00951-22.

- Flunarizine - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/flunarizine. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- Perin PM, Haid S, Brown RJP, Doerrbecker J, Schulze K, Zeilinger C, von Schaewen M, Heller B, Vercauteren K, Luxenburger E, Baktash YM, Vondran FWR, Speerstra S, Awadh A, Mukhtarov F, Schang LM, Kirschning A, Müller R, Guzman CA, Kaderali L, Randall G, Meuleman P, Ploss A, Pietschmann T. 2016. Flunarizine prevents hepatitis C virus membrane fusion in a genotype-dependent manner by targeting the potential fusion peptide within E1. Hepatology 63:49–62. [CrossRef]

- Panda S, Behera S, Alam MF, Syed GH. 2021. Endoplasmic reticulum & mitochondrial calcium homeostasis: The interplay with viruses. Mitochondrion 58:227–242. [CrossRef]

- Qu Y, Sun Y, Yang Z, Ding C. 2022. Calcium Ions Signaling: Targets for Attack and Utilization by Viruses. Front Microbiol 13. [CrossRef]

- Urata S, Yoshikawa R, Yasuda J. 2023. Calcium Influx Regulates the Replication of Several Negative-Strand RNA Viruses Including Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus. Journal of Virology 97:e00015-23. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Frey TK, Yang JJ. 2009. Viral calciomics: interplays between Ca2+ and virus. Cell Calcium 46:1–17. [CrossRef]

- Lee JH, Gomora JC, Cribbs LL, Perez-Reyes E. 1999. Nickel block of three cloned T-type calcium channels: low concentrations selectively block alpha1H. Biophys J 77:3034–3042. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee A, Whitehurst RM, Zhang M, Wang L, Li M. 1997. T-Type Calcium Channels Facilitate Insulin Secretion by Enhancing General Excitability in the Insulin-Secreting β-Cell Line, INS-1*. Endocrinology 138:3735–3740. [CrossRef]

- Verapamil. https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00661. Retrieved 5 September 2024.

- Bergson P, Lipkind G, Lee SP, Duban M-E, Hanck DA. 2011. Verapamil Block of T-Type Calcium Channels. Mol Pharmacol 79:411–419. [CrossRef]

- Maneuf YP, Luo ZD, Lee K. 2006. α2δ and the mechanism of action of gabapentin in the treatment of pain. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 17:565–570.

- Kukkar A, Bali A, Singh N, Jaggi AS. 2013. Implications and mechanism of action of gabapentin in neuropathic pain. Arch Pharm Res 36:237–251. [CrossRef]

- Gabapentin. https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00996. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- Khan KM, Patel JB, Schaefer TJ. 2024. NifedipineStatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL).

- Pryor PR, Mullock BM, Bright NA, Gray SR, Luzio JP. 2000. The Role of Intraorganellar Ca2+In Late Endosome–Lysosome Heterotypic Fusion and in the Reformation of Lysosomes from Hybrid Organelles. Journal of Cell Biology 149:1053–1062. [CrossRef]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. 2004. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of Computational Chemistry 25:1605–1612. [CrossRef]

- Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. 2009. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. J Comput Chem 30:2785–2791. [CrossRef]

- Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. 2009. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. Journal of Computational Chemistry 30:2785–2791. [CrossRef]

- Trott O, Olson AJ. 2010. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. J Comput Chem 31:455–461. [CrossRef]

- Miranda PO, Cubitt B, Jacob NT, Janda KD, de la Torre JC. 2018. Mining a Kröhnke Pyridine Library for Anti-Arenavirus Activity. ACS Infect Dis 4:815–824. [CrossRef]

- Emonet SF, Seregin AV, Yun NE, Poussard AL, Walker AG, de la Torre JC, Paessler S. 2011. Rescue from Cloned cDNAs and In Vivo Characterization of Recombinant Pathogenic Romero and Live-Attenuated Candid #1 Strains of Junin Virus, the Causative Agent of Argentine Hemorrhagic Fever Disease. J Virol 85:1473–1483.

- Iwasaki M, de la Torre JC. 2018. A Highly Conserved Leucine in Mammarenavirus Matrix Z Protein Is Required for Z Interaction with the Virus L Polymerase and Z Stability in Cells Harboring an Active Viral Ribonucleoprotein. Journal of Virology 92:e02256-17.

- Battegay M. 1993. [Quantification of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus with an immunological focus assay in 24 well plates] [Article in German]. 1. ALTEX - Alternatives to animal experimentation 10:6–14.

- Cubitt B, Ortiz-Riano E, Cheng BYH, Kim Y-J, Yeh CD, Chen CZ, Southall NOE, Zheng W, Martinez-Sobrido L, de la Torre JC. 2020. A cell-based, infectious-free, platform to identify inhibitors of lassa virus ribonucleoprotein (vRNP) activity. Antiviral Res 173:104667. [CrossRef]

- Capul AA, de la Torre JC. 2008. A cell-based luciferase assay amenable to high-throughput screening of inhibitors of arenavirus budding. Virology 382:107–114.

- Okogbenin S, Erameh C, Okoeguale J, Edeawe O, Ekuaze E, Iraoyah K, Agho J, Groger M, Kreuels B, Oestereich L, Babatunde FO, Akhideno P, Günther S, Ramharter M, Omansen T. 2022. Two Cases of Lassa Fever Successfully Treated with Ribavirin and Adjunct Dexamethasone for Concomitant Infections. Emerg Infect Dis 28:2060–2063. [CrossRef]

- Urata S, Yasuda J, de la Torre JC. 2009. The Z Protein of the New World Arenavirus Tacaribe Virus Has Bona Fide Budding Activity That Does Not Depend on Known Late Domain Motifs. Journal of Virology 83:12651–12655. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y-J, Venturini V, de la Torre JC. 2021. Progress in Anti-Mammarenavirus Drug Development. 7. Viruses 13:1187. [CrossRef]

- Flunarizine. https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB04841. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- Lin ZJ, Musiano D, Abbot A, Shum L. 2005. In vitro plasma protein binding determination of flunarizine using equilibrium dialysis and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 37:757–762. [CrossRef]

- Gowen BB, Juelich TL, Sefing EJ, Brasel T, Smith JK, Zhang L, Tigabu B, Hill TE, Yun T, Pietzsch C, Furuta Y, Freiberg AN. 2013. Favipiravir (T-705) Inhibits Junín Virus Infection and Reduces Mortality in a Guinea Pig Model of Argentine Hemorrhagic Fever. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 7:e2614. [CrossRef]

- Safronetz D, Rosenke K, Westover JB, Martellaro C, Okumura A, Furuta Y, Geisbert J, Saturday G, Komeno T, Geisbert TW, Feldmann H, Gowen BB. 2015. The broad-spectrum antiviral favipiravir protects guinea pigs from lethal Lassa virus infection post-disease onset. 1. Sci Rep 5:14775. [CrossRef]

- Cashman KA, Smith MA, Twenhafel NA, Larson RA, Jones KF, Allen RD, Dai D, Chinsangaram J, Bolken TC, Hruby DE, Amberg SM, Hensley LE, Guttieri MC. 2011. Evaluation of Lassa antiviral compound ST-193 in a guinea pig model. Antiviral Res 90:70–79. [CrossRef]

- Domingo E, Martin V, Perales C, Grande-Pérez A, García-Arriaza J, Arias A. 2006. Viruses as quasispecies: biological implications. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 299:51–82.

- Ashburn TT, Thor KB. 2004. Drug repositioning: identifying and developing new uses for existing drugs. 8. Nat Rev Drug Discov 3:673–683. [CrossRef]

- Pushpakom S, Iorio F, Eyers PA, Escott KJ, Hopper S, Wells A, Doig A, Guilliams T, Latimer J, McNamee C, Norris A, Sanseau P, Cavalla D, Pirmohamed M. 2019. Drug repurposing: progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Drug Discov 18:41–58.

- Daghir Janabi AH. 2020. Effective Anti-SARS-CoV-2 RNA Dependent RNA Polymerase Drugs Based on Docking Methods: The Case of Milbemycin, Ivermectin, and Baloxavir Marboxil. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol 12:246–250.

- Akazawa D, Ohashi H, Hishiki T, Morita T, Iwanami S, Kim KS, Jeong YD, Park E-S, Kataoka M, Shionoya K, Mifune J, Tsuchimoto K, Ojima S, Azam AH, Nakajima S, Park H, Yoshikawa T, Shimojima M, Kiga K, Iwami S, Maeda K, Suzuki T, Ebihara H, Takahashi Y, Watashi K. 2023. Potential Anti-Mpox Virus Activity of Atovaquone, Mefloquine, and Molnupiravir, and Their Potential Use as Treatments. J Infect Dis 228:591–603. [CrossRef]

- Ismailova A, White JH. 2022. Vitamin D, infections and immunity. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 23:265–277.

- Pietschmann T. 2017. Clinically Approved Ion Channel Inhibitors Close Gates for Hepatitis C Virus and Open Doors for Drug Repurposing in Infectious Viral Diseases. J Virol 91:e01914-16. [CrossRef]

- Han Z, Madara JJ, Herbert A, Prugar LI, Ruthel G, Lu J, Liu Y, Liu W, Liu X, Wrobel JE, Reitz AB, Dye JM, Harty RN, Freedman BD. 2015. Calcium Regulation of Hemorrhagic Fever Virus Budding: Mechanistic Implications for Host-Oriented Therapeutic Intervention. PLOS Pathogens 11:e1005220. [CrossRef]

- Banda DH, Perin PM, Brown RJP, Todt D, Solodenko W, Hoffmeyer P, Kumar Sahu K, Houghton M, Meuleman P, Müller R, Kirschning A, Pietschmann T. 2019. A central hydrophobic E1 region controls the pH range of hepatitis C virus membrane fusion and susceptibility to fusion inhibitors. J Hepatol 70:1082–1092. [CrossRef]

- Colpitts CC, Chung RT, Baumert TF. 2017. Entry Inhibitors: A Perspective for Prevention of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Organ Transplantation. ACS Infect Dis 3:620–623. [CrossRef]

- Vercauteren K, Brown RJP, Mesalam AA, Doerrbecker J, Bhuju S, Geffers R, Van Den Eede N, McClure CP, Troise F, Verhoye L, Baumert T, Farhoudi A, Cortese R, Ball JK, Leroux-Roels G, Pietschmann T, Nicosia A, Meuleman P. 2016. Targeting a host-cell entry factor barricades antiviral-resistant HCV variants from on-therapy breakthrough in human-liver mice. Gut 65:2029–2034. [CrossRef]

- Cheng H, Schafer A, Soloveva V, Gharaibeh D, Kenny T, Retterer C, Zamani R, Bavari S, Peet NP, Rong L. 2017. Identification of a coumarin-based antihistamine-like small molecule as an anti-filoviral entry inhibitor. Antiviral research 145:24. [CrossRef]

- How many drug targets are there? | Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrd2199. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- He S, Lin B, Chu V, Hu Z, Hu X, Xiao J, Wang AQ, Schweitzer CJ, Li Q, Imamura M, Hiraga N, Southall N, Ferrer M, Zheng W, Chayama K, Marugan JJ, Liang TJ. 2015. Repurposing of the antihistamine chlorcyclizine and related compounds for treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Science translational medicine 7:282ra49. [CrossRef]

- Witwit H, Betancourt CA, Cubitt B, Khafaji R, Kowalski H, Jackson N, Ye C, Martinez-Sobrido L, de la Torre JC. 2024. Cellular N-Myristoyl Transferases Are Required for Mammarenavirus Multiplication. 9. Viruses 16:1362. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

In silico docking flowchart. To identify existing drugs that could be potentially repurposed to treat cases of LF, we performed an in silico docking screen of 2015 existing drugs from drugbank to identify those predicted to target LASV proteins and their activities (

Figure 1). We specifically focus on candidate drugs targeting activities associated with LASV L, NP and Z proteins. Our

in-silico screen identified five drugs with high predicted binding affinities to one or more of the LASV target proteins (

Table 1). Amino acid residues in LASV proteins predicted to be responsible for interactions with the selected drugs were explored in the respective receptor-ligand complexes using Discovery Studio 2024 (

Table 2).

Figure 1.

In silico docking flowchart. To identify existing drugs that could be potentially repurposed to treat cases of LF, we performed an in silico docking screen of 2015 existing drugs from drugbank to identify those predicted to target LASV proteins and their activities (

Figure 1). We specifically focus on candidate drugs targeting activities associated with LASV L, NP and Z proteins. Our

in-silico screen identified five drugs with high predicted binding affinities to one or more of the LASV target proteins (

Table 1). Amino acid residues in LASV proteins predicted to be responsible for interactions with the selected drugs were explored in the respective receptor-ligand complexes using Discovery Studio 2024 (

Table 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of selected compounds on the LASV and LCMV vRNP activity in cell-based MG assays. (a). Compound effect on MG directed ZsG (LASV-MG) or GFP (LCMV-MG) expression. HEK293T cells were seeded in 96-well plate (3.0 x 104 cells/M96well) and 16 h later overnight transfected with plasmids (pCAGGS) expressing LASV or LCMV trans-acting factors NP and L trans-acting factor and a plasmid that allowed for intracellular T7 RNA polymerase mediate synthesis of the LASV or LCMV MG RNAs. At 5 h post transfection, the transfecting medium was replaced with media containing the indicated compounds at 20µM. At 48 h post-transfection, whole cell lysates were harvested to determine levels of ZsGreen (LASV-MG) or GFP (LCMV MG). ZsGreen and GFP measurements were normalized to total protein in lysate and all samples were normalized to vehicle control. The experiment was done in four replicate and indicated values represents the mean ± Standard Deviation (SD). (b). Epifluorescence images of cells expressing the LASV-MG (ZsG) or LCMV-MG (GFP) in the presence of the indicated compounds were collected after fixing with 4% PFA at 48 h post-transfection using Keyence BZ-X710 imaging system. (c). Compound effect on cell viability. The dose-dependent effect of the indicated compounds on HEK293T cells viability was determined using CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay. Results correspond to the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of four biological replicates.

Figure 2.

Effect of selected compounds on the LASV and LCMV vRNP activity in cell-based MG assays. (a). Compound effect on MG directed ZsG (LASV-MG) or GFP (LCMV-MG) expression. HEK293T cells were seeded in 96-well plate (3.0 x 104 cells/M96well) and 16 h later overnight transfected with plasmids (pCAGGS) expressing LASV or LCMV trans-acting factors NP and L trans-acting factor and a plasmid that allowed for intracellular T7 RNA polymerase mediate synthesis of the LASV or LCMV MG RNAs. At 5 h post transfection, the transfecting medium was replaced with media containing the indicated compounds at 20µM. At 48 h post-transfection, whole cell lysates were harvested to determine levels of ZsGreen (LASV-MG) or GFP (LCMV MG). ZsGreen and GFP measurements were normalized to total protein in lysate and all samples were normalized to vehicle control. The experiment was done in four replicate and indicated values represents the mean ± Standard Deviation (SD). (b). Epifluorescence images of cells expressing the LASV-MG (ZsG) or LCMV-MG (GFP) in the presence of the indicated compounds were collected after fixing with 4% PFA at 48 h post-transfection using Keyence BZ-X710 imaging system. (c). Compound effect on cell viability. The dose-dependent effect of the indicated compounds on HEK293T cells viability was determined using CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay. Results correspond to the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of four biological replicates.

Figure 3.

Dose-response curves of selected compounds on LCMV multiplication in Vero cells. Vero cells were seeded (3.0 x 104 cells/well) in 96-well plate and 16 h later infected with rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP at an MOI of 0.03. After 90 min adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and infected cells treated with the indicated compounds at different concentrations. At 48 h post-infection, cell viability was evaluated using CellTiter 96 Aqueous One solution reagent (Promega), the cells were washed and fixed, and GFP expression levels were measured using a fluorescent plate reader. The dose response assay was performed in four replicates for each compound, and the mean values were normalized to the Vehicle Control. EC50, CC50, and SI values are shown. ND, no determine.

Figure 3.

Dose-response curves of selected compounds on LCMV multiplication in Vero cells. Vero cells were seeded (3.0 x 104 cells/well) in 96-well plate and 16 h later infected with rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP at an MOI of 0.03. After 90 min adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and infected cells treated with the indicated compounds at different concentrations. At 48 h post-infection, cell viability was evaluated using CellTiter 96 Aqueous One solution reagent (Promega), the cells were washed and fixed, and GFP expression levels were measured using a fluorescent plate reader. The dose response assay was performed in four replicates for each compound, and the mean values were normalized to the Vehicle Control. EC50, CC50, and SI values are shown. ND, no determine.

Figure 4.

Effect of FLN on LCMV multiplication in human A549 cells. (a). Dose-dependent effect of FLN on LCMV multiplication. A549 cells were seeded (3.0 x 10^4 cells/well) in 96-well plate and 16 h later infected with rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP at MOI of 0.03. After 90 min adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and infected cells treated with the indicated concentrations of FLN (four replicates per concentration). At 72 h post infection, cells were fixed and stained with DAPI. GFP expression levels and DAPI staining were used to determine EC50 and CC50, respectively, values. Values correspond to the mean ± SD of four replicates. (b). Effect of FLN (50 µM) on LCMV multi-step growth kinetics and peak titers. A549 cells were seeded (2.0 x 105 cells / M12well) and 16 h later infected with rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP at MOI of 0.03. After 90 min adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and infected cells treated with FLN (50 µM), or ribavirin (100 µM) as a control. At the indicated h post-infection tissue culture supernatants were collected and virus titers determined by FFA using Vero cells. Virus titers shown correspond to the mean ± SD of six biological replicates. (c). Effect of FLN on virus cell propagation of LCMV. After collection of CCS, cells were washed and subjected to Hoechst staining, and images were taken using Keyence BZ-X710 at x4 magnification. (d). Effect of FLN on levels of viral RNA as determined by RT-qPCR. After images of live cells were collected (c), cells were washed and total RNA isolated from each sample using TRI Reagent, and RT-qPCR was used to determine levels of NP gene expression for each treatment normalized to GAPDH. Relative Quantification was calculated using the untreated sample as the calibrator and the mean ± SD were plotted with statistical significance of P < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Effect of FLN on LCMV multiplication in human A549 cells. (a). Dose-dependent effect of FLN on LCMV multiplication. A549 cells were seeded (3.0 x 10^4 cells/well) in 96-well plate and 16 h later infected with rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP at MOI of 0.03. After 90 min adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and infected cells treated with the indicated concentrations of FLN (four replicates per concentration). At 72 h post infection, cells were fixed and stained with DAPI. GFP expression levels and DAPI staining were used to determine EC50 and CC50, respectively, values. Values correspond to the mean ± SD of four replicates. (b). Effect of FLN (50 µM) on LCMV multi-step growth kinetics and peak titers. A549 cells were seeded (2.0 x 105 cells / M12well) and 16 h later infected with rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP at MOI of 0.03. After 90 min adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and infected cells treated with FLN (50 µM), or ribavirin (100 µM) as a control. At the indicated h post-infection tissue culture supernatants were collected and virus titers determined by FFA using Vero cells. Virus titers shown correspond to the mean ± SD of six biological replicates. (c). Effect of FLN on virus cell propagation of LCMV. After collection of CCS, cells were washed and subjected to Hoechst staining, and images were taken using Keyence BZ-X710 at x4 magnification. (d). Effect of FLN on levels of viral RNA as determined by RT-qPCR. After images of live cells were collected (c), cells were washed and total RNA isolated from each sample using TRI Reagent, and RT-qPCR was used to determine levels of NP gene expression for each treatment normalized to GAPDH. Relative Quantification was calculated using the untreated sample as the calibrator and the mean ± SD were plotted with statistical significance of P < 0.05.

Figure 5.

Effect of FLN on different steps of the LCMV life cycle. (a). Time of addition Assay. A549 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate (3.0 x 104 cells/well). After overnight incubation, cells were treated with FLN (50 µM), VC, and the LCMV cell entry inhibitor F3406 (5 µM) starting 2 h prior (-2) or 2 h post (+2) infection with the single-cycle infectious rARMΔGPC/ZsG-P2A-NP at an MOI of 1.0. ZsGreen expression level were determined at 48 h post-infection and mean values normalized to VC treated well which was set at 100%. Values of ZsG from -2 and +2 samples of each treatment were analyzed by the ordinary One-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism. P < 0.0001. (b). Budding assay. HEK293T cells were seeded (1.75x105 cells/well) into poly-l-lysine-coated wells in a 12-well plate. The next day, cells were transfected with either pC.LASV-Z-GLuc, pC.LASV-Z-G2A-GLuc (mutant control), or pCAGGS-Empty (pC-E). After 5 h transfection, cells were washed three times and treated with FLN (50µM), VC and Ribavirin (100µM). At 48 h post-transfection, tissue culture supernatants (TCSs) were collected, the cells washed and whole-cell lysis (WCL) collected. GLuc activity was measured in the TCS (ZVLP) and WCL (the WCL values were normalized with the total protein in the lysate (ZWCL) using the SteadyGlo Luciferase Pierce: Gaussia Luciferase Glow assay kit on a Cytation5 reader. Budding efficiency defined as ratio ZVLP/(ZVLP+ZWCL) was normalized then plotted and analyzed (One-way Anova) using GraphPad Prism software (v.10). P < 0.0001. (c). Virucidal assay. rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP (1x105 ffu/ml) was treated with FLN at the indicated concentrations for 30 min at room temperature. The Infectivity of the virus after treatment was determined by FFA using Vero E6 cells. 10-fold dilutions of treated virus were used to infect Vero cells in quadruplicates, and foci identified based on GFP expression. Infectious titers were normalized (%) to vehicle treated infected cells which was set at 100%. Results are presented as mean ± SD (four replicates). Results were analysed (ANOVA) using GraphPad Prism software (v.10). p = 0.0965.

Figure 5.

Effect of FLN on different steps of the LCMV life cycle. (a). Time of addition Assay. A549 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate (3.0 x 104 cells/well). After overnight incubation, cells were treated with FLN (50 µM), VC, and the LCMV cell entry inhibitor F3406 (5 µM) starting 2 h prior (-2) or 2 h post (+2) infection with the single-cycle infectious rARMΔGPC/ZsG-P2A-NP at an MOI of 1.0. ZsGreen expression level were determined at 48 h post-infection and mean values normalized to VC treated well which was set at 100%. Values of ZsG from -2 and +2 samples of each treatment were analyzed by the ordinary One-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism. P < 0.0001. (b). Budding assay. HEK293T cells were seeded (1.75x105 cells/well) into poly-l-lysine-coated wells in a 12-well plate. The next day, cells were transfected with either pC.LASV-Z-GLuc, pC.LASV-Z-G2A-GLuc (mutant control), or pCAGGS-Empty (pC-E). After 5 h transfection, cells were washed three times and treated with FLN (50µM), VC and Ribavirin (100µM). At 48 h post-transfection, tissue culture supernatants (TCSs) were collected, the cells washed and whole-cell lysis (WCL) collected. GLuc activity was measured in the TCS (ZVLP) and WCL (the WCL values were normalized with the total protein in the lysate (ZWCL) using the SteadyGlo Luciferase Pierce: Gaussia Luciferase Glow assay kit on a Cytation5 reader. Budding efficiency defined as ratio ZVLP/(ZVLP+ZWCL) was normalized then plotted and analyzed (One-way Anova) using GraphPad Prism software (v.10). P < 0.0001. (c). Virucidal assay. rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP (1x105 ffu/ml) was treated with FLN at the indicated concentrations for 30 min at room temperature. The Infectivity of the virus after treatment was determined by FFA using Vero E6 cells. 10-fold dilutions of treated virus were used to infect Vero cells in quadruplicates, and foci identified based on GFP expression. Infectious titers were normalized (%) to vehicle treated infected cells which was set at 100%. Results are presented as mean ± SD (four replicates). Results were analysed (ANOVA) using GraphPad Prism software (v.10). p = 0.0965.

Figure 6.

Effect of FLN on GP2 mediated pH-dependent fusion. HEK293T cells were seeded (1.25 x 105 cells/M24well). Next day, cells were transfected with pC-LCMV-GPC + pC-GFP + pC-E or pC-GFP + pC-E using Lipofectamine 3000. At 18 h post transfection, transfection mixture was removed and replaced with fresh media containing VC or drug. After 5 h, cells were exposed to acidified (pH = 5.2) medium for 15 minutes. Acidified medium was removed, and wells washed, Cells were fixed after 2 h, Stained with DAPI and syncytium formation visualized based on GFP expression.

Figure 6.

Effect of FLN on GP2 mediated pH-dependent fusion. HEK293T cells were seeded (1.25 x 105 cells/M24well). Next day, cells were transfected with pC-LCMV-GPC + pC-GFP + pC-E or pC-GFP + pC-E using Lipofectamine 3000. At 18 h post transfection, transfection mixture was removed and replaced with fresh media containing VC or drug. After 5 h, cells were exposed to acidified (pH = 5.2) medium for 15 minutes. Acidified medium was removed, and wells washed, Cells were fixed after 2 h, Stained with DAPI and syncytium formation visualized based on GFP expression.

Figure 7.

Effect of FLN on JUNV multiplication in Vero cells. Effect of FLN (50 µM) on LCMV multi-step growth kinetics and peak titers. A549 cells were seeded (2.0 x 10^5 cells / M12well) and 16 h later infected with r3JUNVCandid GFP/GFP at MOI of 0.2. After 90 min adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and infected cells treated with FLN (50 µM), or ribavirin (100 µM) as a control. At the indicated h post-infection tissue culture supernatants were collected and virus titers determined by FFA using Vero cells. Virus titers shown correspond to the mean ± SD.

Figure 7.

Effect of FLN on JUNV multiplication in Vero cells. Effect of FLN (50 µM) on LCMV multi-step growth kinetics and peak titers. A549 cells were seeded (2.0 x 10^5 cells / M12well) and 16 h later infected with r3JUNVCandid GFP/GFP at MOI of 0.2. After 90 min adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and infected cells treated with FLN (50 µM), or ribavirin (100 µM) as a control. At the indicated h post-infection tissue culture supernatants were collected and virus titers determined by FFA using Vero cells. Virus titers shown correspond to the mean ± SD.

Figure 8.

Effect of selected calcium channel blockers on LCMV multiplication in A549 cells. A549 cells were seeded (3.0 x 104 cells/well) in 96-well plate and 16 h later infected with rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP at MOI of 0.03. After 90 min adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and infected cells treated with 2-fold dilutions of gabapentin(100µM), nifedipine(100µM), verapamil(100µM), and nickel chloride(500µM) (four replicates per concentration. At 72 h post-infection, cells were fixed with 4% PFA and stained with DAPI. GFP expression levels and DAPI staining were used to determine virus infectivity and cell viability, respectively. Values correspond to the mean ± SD of four replicates. Levels of GFP expression and DAPI staining were normalized assigning a value of 100% to GFP expression levels and DAPI staining VC-treated and infected cells. Normalized values were used to determine the EC50 and CC50.

Figure 8.

Effect of selected calcium channel blockers on LCMV multiplication in A549 cells. A549 cells were seeded (3.0 x 104 cells/well) in 96-well plate and 16 h later infected with rLCMV/GFP-P2A-NP at MOI of 0.03. After 90 min adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and infected cells treated with 2-fold dilutions of gabapentin(100µM), nifedipine(100µM), verapamil(100µM), and nickel chloride(500µM) (four replicates per concentration. At 72 h post-infection, cells were fixed with 4% PFA and stained with DAPI. GFP expression levels and DAPI staining were used to determine virus infectivity and cell viability, respectively. Values correspond to the mean ± SD of four replicates. Levels of GFP expression and DAPI staining were normalized assigning a value of 100% to GFP expression levels and DAPI staining VC-treated and infected cells. Normalized values were used to determine the EC50 and CC50.

Figure 9.

Effect of FLN in the absence of serum on LCMV multi-step growth kinetics and peak titers. A549 cells were seeded (2.0 x 10^5 cells / M12well) and 16 h later infected with LCMV/GFP-P2A-NP at MOI of 0.03. After 90 min adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and infected cells treated with FLN in Optimum (50 µM, 25µM, 12.5µM), or ribavirin (100 µM) as a control. At the indicated h post-infection tissue culture supernatants were collected and virus titers determined by FFA using Vero cells. Virus titers shown correspond to the mean ± SD.

Figure 9.

Effect of FLN in the absence of serum on LCMV multi-step growth kinetics and peak titers. A549 cells were seeded (2.0 x 10^5 cells / M12well) and 16 h later infected with LCMV/GFP-P2A-NP at MOI of 0.03. After 90 min adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and infected cells treated with FLN in Optimum (50 µM, 25µM, 12.5µM), or ribavirin (100 µM) as a control. At the indicated h post-infection tissue culture supernatants were collected and virus titers determined by FFA using Vero cells. Virus titers shown correspond to the mean ± SD.

Table 1.

Binding affinities of selected existing drugs predicted to target LASV proteins.

Table 1.

Binding affinities of selected existing drugs predicted to target LASV proteins.

| Drug |

Polymerase

|

Z-Protein |

Nucleoprotein

|

|

| DEX |

-7.60 ±0.00 |

-6.63 ±0.05 |

-8.20 ±0.00 |

|

| FLN |

-8.20 ±0.12 |

-6.35 ±0.06 |

-8.08 ±0.13 |

|

| TAD |

-7.83 ±0.05 |

-7.50 ±0.00 |

-8.90 ±0.00 |

|

| Vit D |

-7.55 ±0.06 |

-6.80 ±0.00 |

-7.58 ±0.39 |

|

| MEFFm |

-9.85 ±0.05 |

-6.15 ±0.24 |

-7.20 ±0.00 |

|

Table 2.

Discovery Studio predicted interacting amino acid residues in LASV proteins targeted by selected drugs.

Table 2.

Discovery Studio predicted interacting amino acid residues in LASV proteins targeted by selected drugs.

| Drug |

Polymerase |

Z-Protein |

Nucleoprotein |

| DEX |

R24, L48 |

Y48, K32, H47, L26 |

L505 A552, H412, H507, V559, F414, R556, Y410 |

| FLN |

V87, E102, F104, D66, V105, I50, E51, D89, N63, D119 |

K74, L31, V60, C64, C44 |

L505 A552, H412, H507, V559, M508, R556, L554 |

| TAD |

V105, F104 |

K71, S59, C44, C67, N45 |

L505, A552, C506, M508 |

| Vit D |

K44, L48, V105 |