Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Santodomingo-Rubido, J.; Carracedo, G.; Suzaki, A.; Villa-Collar, C.; Vincent, S.J.; Wolffsohn, J.S. Keratoconus: An updated review. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2022, 45, 101559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borderie, V.M.; Laroche, L. Measurement of irregular astigmatism using semi meridian data from videokeratography. J Refract Surg. 1996, 12, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, J.A.P.; Rodrigues, P.F.; Lamazales, L.L. Keratoconus epidemiology: A review. Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology 2022, 36, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.R.; Soneji, B.; Sarvananthan, N.; Sandford-Smith, J.H. Does ethnic origin influence the incidence or severity of keratoconus? Eye (Lond). 2000, 14 Pt 4, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, J.B.; Nangia, V.; Matin, A.; Kulkarni, M.; Bhojwani, K. Prevalence and associations of keratoconus in rural Maharashtra in central India: the central India eye and medical study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009, 148, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharini, B.; Sahebjada, S.; Borrone, M.A.; Vaddavalli, P.; Ali, H.; Reddy, J.C. Keratoconus in pre-teen children: Demographics and clinical profile. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022, 70, 3508–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Shaag, A.; Millodot, M.; Shneor, E.; Liu, Y. The genetic and environmental factors for keratoconus. Biomed Res Int. 2015, 2015, 795738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Rana, J.; Kataria, S.; Bhan, C.; Priya, P. Demographic and clinical characteristics of childhood and adult-onset Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis in a tertiary care center during Covid pandemic: A prospective study. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2022, 66, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohaghegh, S.; Kangari, H.; Masoumi, S.J.; Bamdad, S.; Rahmani, S.; Abdi, S.; Fazil, N.; Shahbazi, S. Prevalence and risk factors of keratoconus (including oxidative stress biomarkers) in a cohort study of Shiraz university of medical science employees in Iran. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023, 23, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, S.E.M.; Burdon, K.P. Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors for Keratoconus. Annu Rev Vis Sci. 2020, 6, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, H.; Heydarian, S.; Hooshmand, E.; Saatchi, M.; Yekta, A.; Aghamirsalim, M.; Valadkhan, M.; Mortazavi, M.; Hashemi, A.; Khabazkhoob, M. The Prevalence and Risk Factors for Keratoconus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cornea. 2020, 39, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temaj, G.; Nuhii, N.; Sayer, J.A. The impact of consanguinity on human health and disease with an emphasis on rare diseases. J Rare Dis 2022, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, T.B.; Priyadarsini, S.; Karamichos, D. Mechanisms of Collagen Crosslinking in Diabetes and Keratoconus. Cells. 2019, 8, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unni, P.; Lee, H.J. Systemic Associations with Keratoconus. Life (Basel). 2023, 13, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, T.T.; Kim, L.S.; Fishman, G.A.; Stone, E.M.; Zhao, X.C.; Yee, R.W.; Malicki, J. CRB1 gene mutations are associated with keratoconus in patients with Leber congenital amaurosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009, 50, 3185–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas Tur, V.; MacGregor, C.; Jayaswal, R.; O’Brart, D.; Maycock, N. A review of keratoconus: Diagnosis, pathophysiology, and genetics. Vol. 62, Survey of Ophthalmology. Elsevier USA; 2017. p. 770–83. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Gu, Y.; Xu, L.; Fan, Q.; Zhu, M.; Wang, Q.; Yin, S.; Zhang, B.; Pang, C.; Ren, S. Distribution of pediatric keratoconus by different age and gender groups. Front Pediatr. 2022, 10, 937246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, S.; Chaudhary, M.; Mishra, S.K.; Joshi, N.D.; Subedi, M.; Puri, P.R.; et al. Evaluation of corneal topography, pachymetry, and higher order aberrations for detecting subclinical keratoconus. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2022, 42, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feizi, S.; Yaseri, M.; Kheiri, B. Predictive ability of Galilei to distinguish subclinical keratoconus and keratoconus from normal corneas. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2016, 11, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanavare, R.T. Impact of air pollution on respiratory health: A case study in Mumbai, India. International Journal of Medical and Health Research [Internet]. 2024. Available from: www.medicalsciencejournal.com.

- Manya Rathore Population of Mumbai India 1960-2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/911012/india-population-in-mumbai/#statistic.

- Das, A.V.; Deshmukh, R.S.; Reddy, J.C.; Joshi, V.P.; Singh, V.M.; Gogri, P.Y.; et al. Keratoconus in India: Clinical presentation and demographic distribution based on big data analytics. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2024, 72, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayukotang, E.N.; Moodley, V.R.; Mashige, K.P. Risk Profile of Keratoconus among Secondary School Students in the West Region of Cameroon. Vision (Basel). 2022, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelliah, R.; Rangasamy, R.; Veeraraghavan, G.; et al. Screening for Keratoconus among Students in a Medical College in South India: A Pilot Study. TNOA Journal of Ophthalmic Science and Research 2023, 61, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Netto, E.A.; Al-Otaibi, W.M.; Hafezi, N.L.; Kling, S.; Al-Farhan, H.M.; Randleman, J.B.; et al. Prevalence of keratoconus in pediatric patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2018, 102, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapeyre, G.; Fournie, P.; Vernet, R.; Roseng, S.; Malecaze, F.; Bouzigon, E.; Touboul, D. Keratoconus Prevalence in Families: A French Study. Cornea. 2020, 39, 1473–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Léoni-Mesplié, S.; Mortemousque, B.; Touboul, D.; Malet, F.; Praud, D.; Mesplié, N.; Colin, J. Scalability and severity of keratoconus in children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012, 154, 56–62.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzis, N.; Hafezi, F. Progression of keratoconus and efficacy of pediatric [corrected] corneal collagen cross-linking in children and adolescents. J Refract Surg. 2012, 28, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Guillén, L.; Argente, J. Central precocious puberty, functional and tumor-related. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019, 33, 101262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadgawat, R.; Marwaha, R.K.; Mehan, N.; Surana, V.; Dabas, A.; Sreenivas, V.; Gaine, M.A.; Gupta, N. Age of Onset of Puberty in Apparently Healthy School Girls from Northern India. Indian Pediatr. 2016, 53, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; et al. Associations Between Keratoconus and the Level of Sex Hormones: A Cross-Sectional Study. Frontiers in medicine 2022, 9, 828233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latronico, A.C.; et al. Causes, diagnosis, and treatment of central precocious puberty. The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology 2016, 4, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, T.B.; et al. Sex Hormones, Growth Hormone, and the Cornea. Cells 2022, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad-Rabei, H.; et al. Risk Factors Associated with Keratoconus in an Iranian Population. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research 2023, 18, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, H.; Beigi, V. Sadeghi-Sarvestani Consanguineous Marriage as a Risk Factor for Developing Keratoconus. Discovery &Innovation Ophthalmology Journal. 2018, 11, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bittles, A.H.; Hussain, R. An analysis of consanguineous marriage in the Muslim population of India at regional and state levels. Ann Hum Biol. 2000, 27, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bykhovskaya, Y.; Rabinowitz, Y.S. Update on the genetics of keratoconus. Exp Eye Res. 2021, 202, 108398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, D.M.; Gajecka, M. The genetics of keratoconus. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology 2011, 18, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Genetic epidemiological study of keratoconus: evidence for major gene determination. American journal of medical genetics 2000, 93, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmi, H.; et al. The correlation between keratoconus and eye rubbing: a review. International journal of ophthalmology 2019, 12, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; et al. Effect of eye rubbing on corneal biomechanical properties in myopia and emmetropia. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 2023, 11, 1168503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, E.; Nanavaty, M.A. Eye Rubbing and Keratoconus: A Literature Review. Int J Keratoconus Ectatic Corneal Dis. 2014, 3, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafezi, F.; Hafezi, N.L.; Pajic, B.; Gilardoni, F.; Randleman, J.B.; Gomes, J.A.P.; Kollros, L.; Hillen, M.; Torres-Netto, E.A. Assessment of the mechanical forces applied during eye rubbing. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, V.; Vanathi, M.; Raghavan, A.; Rajaraman, R.; Ravindran, M.; Tandon, R. Pediatric keratoconus - Current perspectives and clinical challenges. Vol. 69, Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. Wolters Kluwer Medknow Publications; 2021. p. 214–25. [CrossRef]

- Nemet, A.Y.; Vinker, S.; Bahar, I.; Kaiserman, I. The association of keratoconus with immune disorders. Cornea. 2010, 29, 1261–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemet, A.Y.; et al. The association of keratoconus with immune disorders. Cornea 2010, 29, 1261–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, I.; et al. The association between keratoconus and allergic eye diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 2022, 50, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazeer, A.M.; Hodge, W.G.; Lorimer, B. Atopy and keratoconus: a multivariate analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000, 84, 834–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, V.; Karakaya, M.; Utine, C.A.; Albayrak, S.; Oge, O.F.; Yilmaz, O.F. Evaluation of the corneal topographic characteristics of keratoconus with orbscan II in patients with and without atopy. Cornea. 2007, 26, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadnik, K.; Barr, J.T.; Edrington, T.B.; Everett, D.F.; Jameson, M.; McMahon, T.T.; Shin, J.A.; Sterling, J.L.; Wagner, H.; Gordon, M.O. Baseline findings in the Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Keratoconus (CLEK) Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998, 39, 2537–2546. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, D.; Sahay, P.; Maharana, P.K.; Raj, N.; Sharma, N.; Titiyal, J.S. Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis. Vol. 64, Survey of Ophthalmology. Elsevier USA; 2019. p. 289–311.

- Assiri, A.A.; Yousuf, B.I.; Quantock, A.J.; Murphy, P.J.; Assiri, A.A. Incidence and severity of keratoconus in Asir province, Saudi Arabia. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2005, 89, 1403–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millodot, M.; Shneor, E.; Albou, S.; Atlani, E.; Gordon-Shaag, A. Prevalence and associated factors of keratoconus in Jerusalem: a cross-sectional study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2011, 18, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nita, M.; Grzybowski, A. The Role of the Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Stress in the Pathomechanism of Age-related Ocular Diseases and Other Pathologies of the Anterior and Posterior Eye Segments in Adults. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, 3164734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.G.; Bailey, A.J. Glycation of collagen: the basis of its central role in the late complications of aging and diabetes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1996, 28, 1297–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderan, M.; et al. Association between diabetes and keratoconus: a case-control study. Cornea 2014, 33, 1271–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathan, J.J.; Gokul, A.; Simkin, S.K.; Meyer, J.J.; Patel, D.V.; McGhee, C.N.J. Topographic screening reveals keratoconus to be extremely common in Down syndrome. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020, 48, 1160–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbanikhah, Z.; Javadi, M.A.; Rostami, P.; Aghdaie, A.; Yaseri, M.; Yahyapour, F.; Katibeh, M. Association between acute corneal hydrops in patients with keratoconus and mitral valve prolapse. Cornea. 2011, 30, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeigler, S.M.; Sloan, B.; Jones, J.A. Pathophysiology and Pathogenesis of Marfan Syndrome. In: Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Springer; 2021. p. 185–206. [CrossRef]

- Burnei, G.; Vlad, C.; Georgescu, I.; Gavriliu, T.S.; Dan, D. Osteogenesis imperfecta: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008, 16, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, T.R.; Turner, M.L.; Hoppe, C.; Kong, A.W.; Barnett, J.S.; Kaur, G.; et al. Parental Keratoconus Literacy: A Socioeconomic Perspective. Clinical Ophthalmology. 2022, 16, 2505–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, H.; Rabinowitz, Y.S. Keratoconus: Classification scheme based on videokeratography and clinical signs. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009, 35, 1597–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastang, P.J.; Borderie, V.M.; Carvajal-Gonzalez, S.; Rostène, W.; Laroche, L. Automated keratoconus detection using the EyeSys videokeratoscope. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000, 26, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourmaux, E.; Riss, I.; Dupuy, B.; Le Rebeller, M.J. Fiabilité et reproductibilité du système d’analyse topographique cornéenne Eyesys [Accuracy and reproducibility of the Eyesys corneal topographic analysis system]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1994, 17, 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, D.D.; Foulks, G.N.; Moran, C.T.; Wakil, J.S. The Corneal EyeSys System: accuracy analysis and reproducibility of the first-generation prototype. Refract Corneal Surg. 1989, 5, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. Cornea and anterior eye assessment with placido-disc keratoscopy, slit scanning evaluation topography and scheimpflug imaging tomography. Vol. 66, Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. Medknow Publications; 2018. p. 360–6. [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, J.; Mahajan, P. Asia’s largest urban slum-Dharavi: A global model for management of COVID-19. Cities (London, England) 2021, 111, 103097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.census2011.co.in/census/metropolitan/305-mumbai.html#google_vignette.

- Manasi, D.; Ashish, N.; Amit, G. Evolution of Heat Index (HI) and Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) Index at Mumbai and Pune Cities, India. MAUSAM 2021, 72, 915–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, M.A.; Blachley, T.S.; Stein, J.D. The association between sociodemographic factors, common systemic diseases, and keratoconus an analysis of a nationwide heath care claims database. Ophthalmology. 2016, 123, 457–465.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| KC criteria | Objective parameter | Cut off value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topography | Mean K | >47.2 D | Mean of flat and steep meridians (Modified Rabinowitz/McDonnell index) (18) |

| I-S value | ≥1.4 D | Power difference between the superior and inferior cornea. (Modified Rabinowitz/McDonnell index) (18) | |

| SAI value | 1.25 | Average corneal power derived from 128 corneal meridians (19). | |

| Asymmetric bow tie pattern | Present | Topographic pattern in KC and subclinical KC. (Huseynli and Abdulaliyeva) (20). | |

| Keratometry (K) | Mean K | ≥47 | Rabinowitz criteria (16) |

| Retinoscopy | Scissor Reflex | Present | A scissoring retinoscopy reflex; (Al-Mahrouqi et al.) (21). |

| Refractive profile | Refractive error | >-5D Myopia and/or Astigmatism | [Amsler’s Krumeich criteria (22). |

| Irregular Astigmatism | >1.5 dioptres(D) | (Huseyin et al.) (23). |

| Demographic profile | Predictor | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 9-12 | 1038 (11.08 ± 0.88) | 51 |

| 13-17 | 1004 (13.81 ± 0.9) | 49 | |

| Total | 2042 (12.46±1.7) | 100 | |

| Sex | Female | 1348 | 66 |

| Male | 694 | 34 | |

| Religion | Muslim | 1043 | 51 |

| Hindu | 982 | 48 | |

| Christian | 3 | 0.15 | |

| Buddhist | 6 | 0.3 | |

| Jain | 7 | 0.34 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.05 |

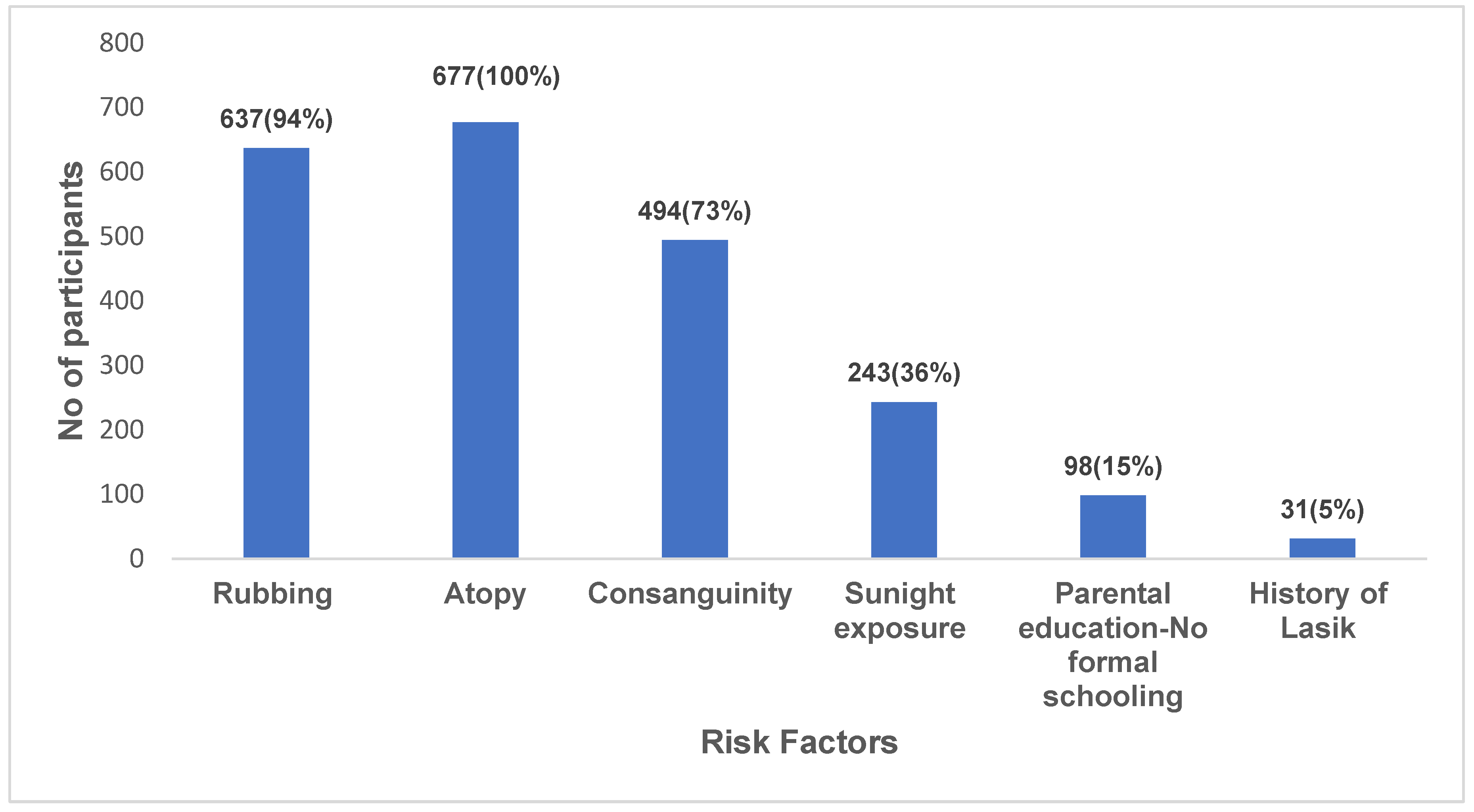

| Risk Factors | Variable | KRIS | Prevalence (%) | Clinical | Prevalence (%) | p-value | Spearman |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=728) | (n=51) | ||||||

| Age | 9-12 13-17 |

415 313 |

57 43 |

26 25 |

51 49 |

<0.001* | 1 |

| Gender | Male Female |

199 529 |

27 73 |

15 36 |

29 71 |

<0.001* | 0.92 |

| Religion | Hindu Muslim |

192 531 |

26 72 |

28 22 |

55 43 |

0.06 | 0.36 |

| Socio--economic Status | <1 lac 1-3 lac > 3lac |

402 265 61 |

55.2 36.4 8.38 |

16 27 8 |

31.3 53 16 |

0.5 | 0.1 |

| Consanguinity | Yes No |

514 214 |

70.6 29.4 |

21 30 |

41 59 |

<0.001* | -0.09 |

| Eye rubbing | Yes No |

688 40 |

94.5 5.5 |

51 0 |

100 | 0.04* | 0.24 |

| Atopy | Yes No |

715 13 |

98.2 1.8 |

51 0 |

100 | <0.001* | 0.49 |

| > 8 hours of sunlight exposure | Yes No |

251 477 |

34.5 65.5 |

5 46 |

9.8 | 0.002* | 0.11 |

| Diabetes and other medical conditions | Yes No |

51 677 |

7 93 |

1 50 |

2 98 |

<0.001* | 0.14 |

|

Parental education |

No formal schooling Formal schooling |

102 626 |

14 86 |

3 48 |

6 94 |

<0.001* |

0.16 |

| Lasik | Yes No |

33 695 |

5 95 |

1 50 |

2 98 |

< 0.001* | 0.17 |

| Family history | Yes No |

27 701 |

4 96.28 |

0 51 |

0 100 |

1 | 0 |

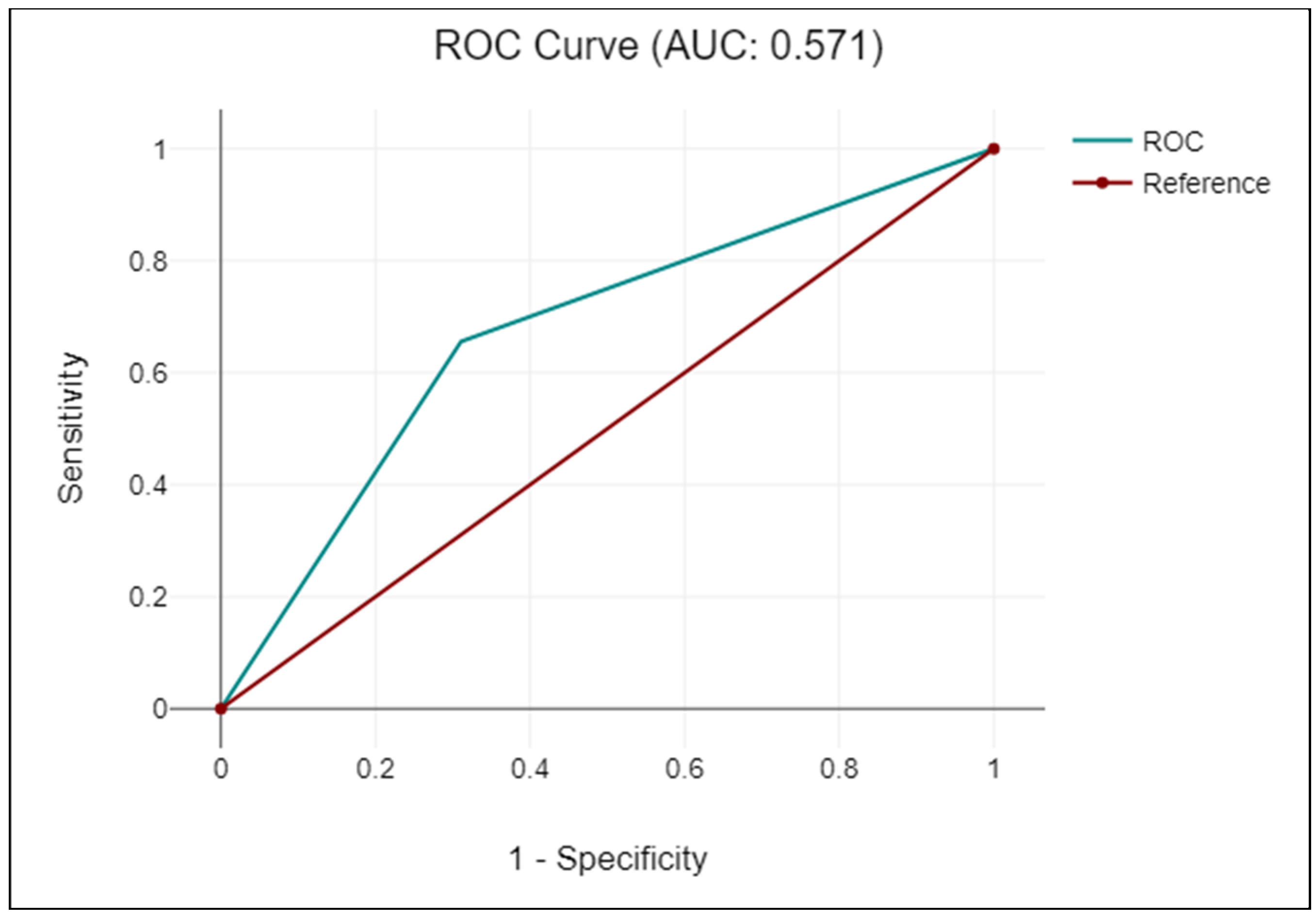

| KRIS | KC | Non-KC | Sensitivity | Specificity | PLR | NLR | Accuracy | Kappa-coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | 51 | 677 | 69 | 66 | 2 | 0.47 | 66 | 0.1 |

| Negative | 23 | 1291 | (95% CI: 57.1 -79.7) | (95% CI: 63.5 -67.7) | (95% CI: 1.7 -2.3) | (95% CI: 0.34 -0.67) | (95% CI: 63.6 -67.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).