1. Introduction

Banks play the role of catalysts for economic development and growth by providing a wide range of financial services for investments (Rundassa & Berta, 2016:108; Mutava & Ali, 2016:15). In the process of financial intermediary, banks are exposed to both financial and non-financial risks (Attarwala & Balasubramaniam, 2015:10). Risk management is fundamental for the sustainable growth of organisations (Abdullah, Shukor & Rahmat, 2017:2).

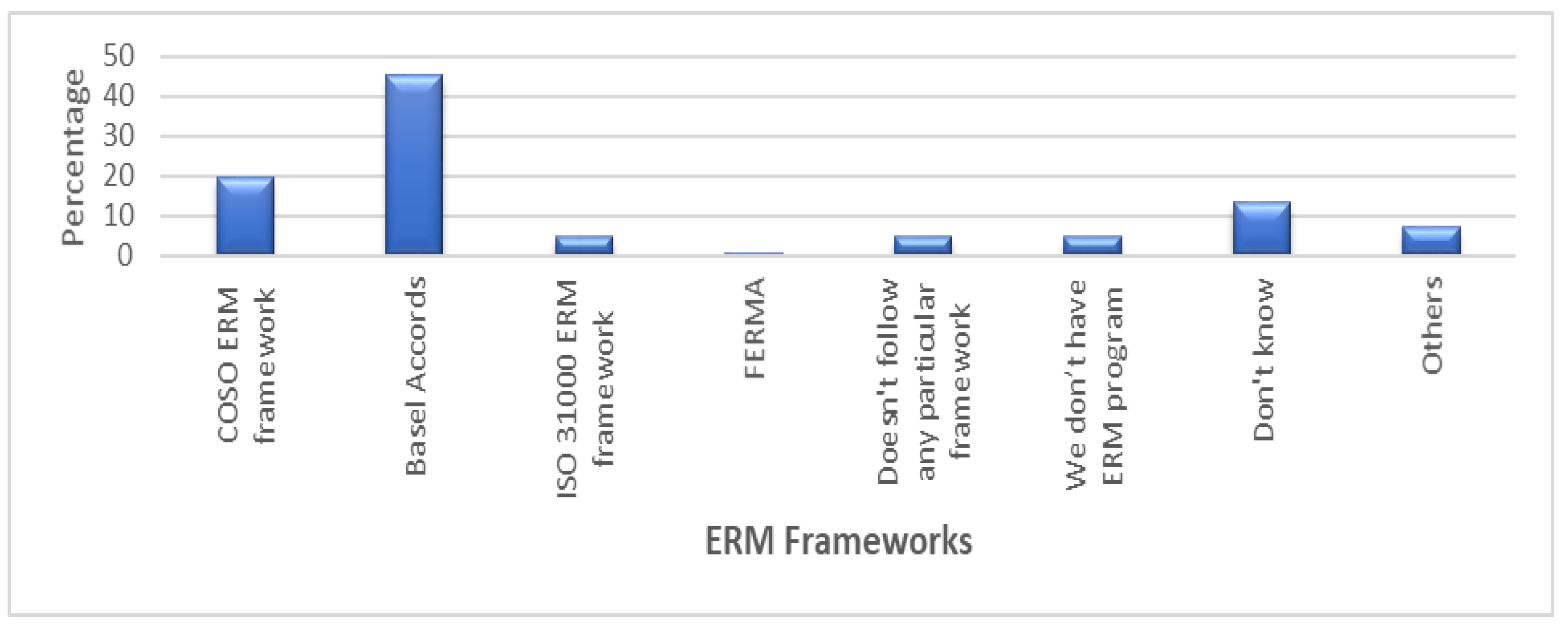

The function of risk management in the banking sector has been improved in recent years, mainly to comply with the regulations that resulted from the global financial crisis and the measures taken to improve the resilience of the financial institutions (Harele, Havas & Samandri, 2016:5). Lately, the concept of risk management has further improved. It has transformed from the traditional silo approach to the holistic one. Enterprise risk management (ERM) has become a global standard across the world to manage organisational risks due to the failure of the traditional risk-based approach (Olayinka, Emoarehi, Jonah & Ame, 2017:938). Harele, Havas and Samandri (2016:3) also noted that the transformation of bank risk management is afoot, which implies risk management will be practiced even more widely in the future.

The banking business in Ethiopia started during the reign of Emperor Menelik II in 1905. The Bank of Abyssinia, the first bank in Ethiopia, stared its operation on February 17, 1905, to issue currency notes and engage in commercial banking (Alemayehu & Teklemedhin, 2012:1; Chanie, 2015:130). Later in 1932, the Bank of Abyssinia changed to the Bank of Ethiopia. Formerly, it was owned by Egyptian investors, and now it is owned by Ethiopian shareholders. During 1974-1991, the government nationalised financial institutions and the banking sector became a fragile and fully government-owned industry. Especially, up to the mid-1990s, mismanagement, poor monitoring and supervision, and higher political intervention made the sector under developed (Ayalew & Xianzhi, 2017:6).

The newly replaced government in 1991 embarked on a new economic reform to replace centrally planned economic policy with a market-oriented system in 1994 and opened the banking industry to private domestic investors. The government has taken many structural measures to handle problems in the financial sector and to improve competition and efficiency. The newly introduced monetary and banking proclamation no. 83/1994 provide more autonomy to National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) and the industry is opened for domestic private investment (Ayalew & Xianzhi, 2017:6). In 1994, the first private commercial bank was licensed to operate in Ethiopia (Kannan & Sudalaimuthu, 2016:7). In 2021, the number of private commercial banks operating in Ethiopia reached 17, up from the only one in 1994 (NBE, 2021:69). Furthermore, following the new home-grown economic reform agenda, the government has opened the sector to full-fledged interest free banks and allowed the foreign nationals of Ethiopian origin to own the share in Ethiopian banks and insurances. Accordingly, 14 banks joined the sector between 2020 and 2023, bringing the total number of commercial banks operating in Ethiopia to 30.

Even though the banking business has a long history in Ethiopia, it is still in its infancy, has emerging intermediary sector and the financial system is underdeveloped (Fanta & Makina, 2016:152; Fanta, 2016:310). It is not yet competitive and efficient, nor is it capable of accelerating the economic growth of the country, which remains marginal (Dido, 2020:60). The Ethiopian population access to bank is the lowest, even from sub-Saharan standard. The percentile of Ethiopian adults with an account is 35%, which is lower than the average percentile of the sub-Saharan region of 43% (Mengistu, 2018:1).

The structure of the Ethiopian financial sector shows that more than 76% of the sector’s asset is controlled by the three largest banks (NBE, 2019). This higher degree of concentration indicates a lower degree of competition (Fanta & Makina, 2016:153). The performance of Ethiopian commercial banks is mainly determined by macroeconomic performance rather than competition (Guruswamy & Hedo, 2014:20). Tewodros (2019:51) also argued that macroeconomic factors are the key determinants of the financial performance of Ethiopian commercial banks. In general, the Ethiopian banking industry is characterised by less efficiency and little or insufficient competition (Ijara & Sharma, 2020:171; Dido, 2020:60).

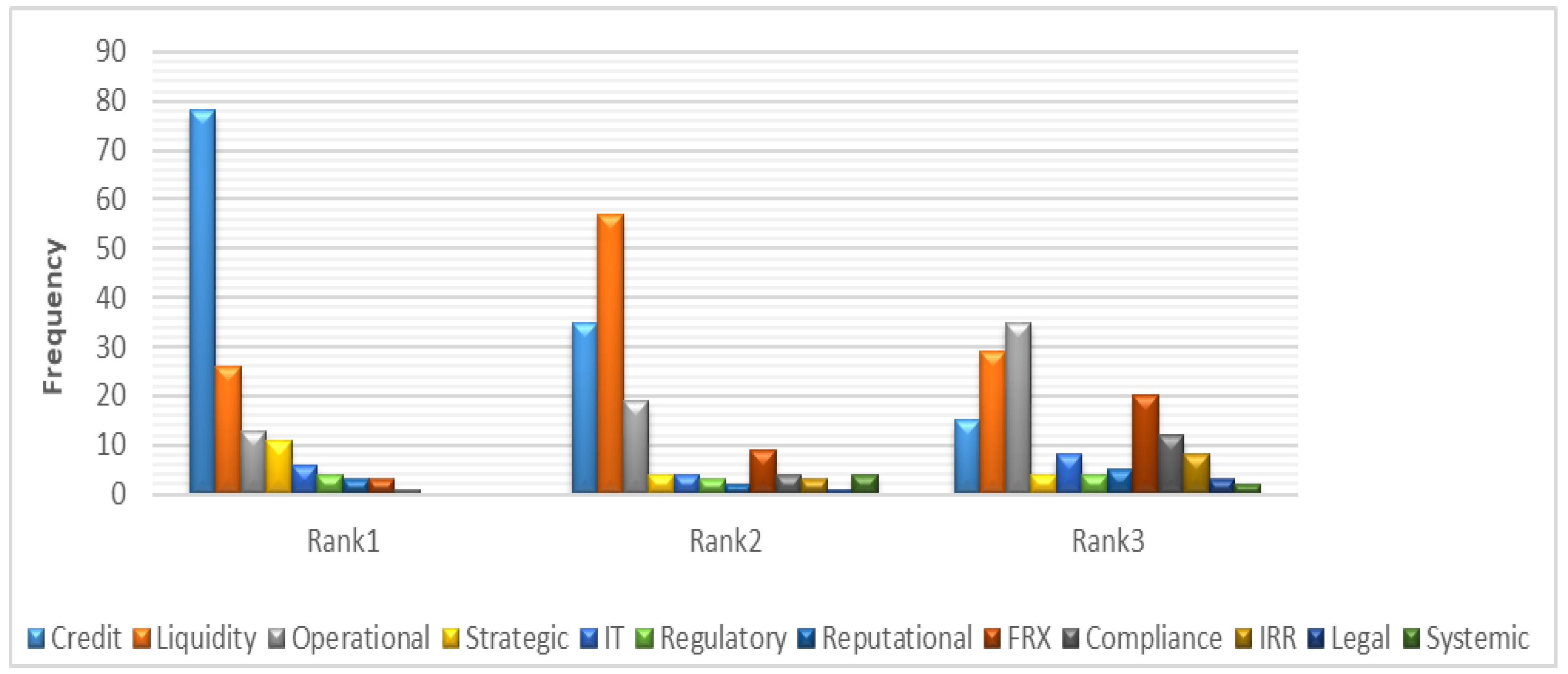

Regulators are responsible for ensuring the existence of a strong risk management systems and practices in banks to enhance reliance on the banking industry. The NBE has revised the Bank Risk Management Guidelines, which was established in 2003. In the revised guideline, the NBE requires all banks operating in Ethiopia to establish a comprehensive risk management programme by focusing on credit, liquidity, market and operational risks (NBE, 2010). The large stock of provisions held by Ethiopian banks set aside for problem loans, which largely exceeds the provisions required for regular loans, confirms that credit risk has been a major concern of the Ethiopian banking industry (Lelissa, 2014a:141). Over recent years, provisions for non-performing loans (NPLs) have consistently increased. Provisions held by Ethiopian commercial banks rose from 70% of NPLs in 2021 to 122.9% in 2022, and further climbed to 132.5% by the end of June 2023 (NBE, 2024:24). Furthermore, the NPL ratio of the banks increased consecutively from 2019 to 2022, rising from 2.3% to 3%, then to 3.5%, and finally to 3.9%. However, there was a declining trend in 2023, with the NPL ratio decreasing to 3.6%. Nevertheless, it is not only the result of poor credit risk management function; due to the interdependence of risks, other risk types could also contribute to the weakness of this function. It needs an integrated approach to risk management to handle all risks holistically encountered by the banks.

Ethiopia aims to join the World Trade Organisation (WTO) by opening up the local market in all sectors for foreign investors, including foreign banks. At that juncture, stiff competition will ensue in the market between the existing banks and the new entrants. The competition is likely to be followed by the subsequent introduction of innovative products and operational and IT risks coming from the innovative products. If it is not managed effectively, it could adversely affect the operation and profitability of the overall Ethiopian banking sector. Establishing an effective ERM function is essential to compete and survive in the global market (Setapa et al., 2020:498). Embedding of strong risk management systems will enable the banks to manage the aforementioned issues proactively. Therefore, there is a pressing need to assess the current ERM practices of Ethiopian commercial banks, pinpointing any gaps in the existing approach to ERM, in order to integrate a robust risk management system tailored to the Ethiopian banking sector.

Despite the growing literature on the issue of ERM in the financial sector, there is a lack of literature focusing on Ethiopia that examines the implementation of ERM in the Ethiopian banking industry. Only a few studies (Guruswamy & Hedo, 2014; Lelissa, 2014a; Gizaw, Kebede & Selvaraj, 2015; Asfaw & Veni, 2015; Ademe, 2015; Tade & Negera, 2017; Pasha & Mintesinot, 2017; Tsige & Singla, 2019; Alemu, 2020) have examined the risk management function in the Ethiopian banking industry. Most of the prior studies focused on the traditional risk management (TRM) approach, the determinant factors of risk management, and its relationship with performance in the context of Ethiopian commercial banks.

From the above studies, only four studies (Ademe, 2015; Gugsa, 2018; Tsige & Singla, 2019; Alemu, 2020) have examined the ERM functions in Ethiopian financial institutions. The result of studies revealed the existence of weak ERM practices. However, the gaps in the ERM practices were not identified comprehensively such as examining the risk assessment reports of the Ethiopian commercial banks.

2. Review of Relevant Literature

Doing business is compounded by uncertainties. These uncertainties might affect the main objectives of companies both positively and negatively (Shad, Lai, Fatt, Klemes & Bokhari, 2019:415). Risk is a key concern for organisations when operating their businesses and the focus given to this issue has become increasing (ISO31000, 2018:1). Khan, Hussain and Mehmood (2016:1886) suggested that, even if it is impossible to fully avoid risks, organisations should manage all type of risk they faced. Historically, risk management was developed to cope with risks that arise in insurance companies and financial institutions, and it was known as traditional risk management (Shad et al., 2019:416). Traditionally, the function of risk management was considered to protect an organisation from loss (Tuten, 2018:1). The approach and focus of silo-based risk management were limited to holistically managing interrelated risks, particularly in complex and global companies exposed to the financial crisis (Florio & Leoni, 2017:57).

The development of risk models and enterprise-wide approaches to risk management promotes the function of risk management to broaden enterprise-wide, across all business lines and different types of risks (Bessis, 2012:43). A new concept named Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) was developed in 1990 to manage a group of risks around all business units using a holistic approach (Shad & Lai, 2015:1; Soomro & Lai, 2017:329; Braumann, 2018:241). This approach is a more integrated approach and involves assessment, quantification, and management of risks in the whole enterprise within all business functions and levels (Florio & Leoni, 2017:57-58). There are various guiding principles for the conceivable adoption of an ERM programme that enable the evaluation of all material risks facing an organisation in a holistic approach. Due to the incorporation of risk management into corporate strategy, ERM should be a top-down process that board of directors is responsible for (Bohnert et al, 2019:236).

In an environment of increased risk complexities, the stakeholders of organisations need a risk management framework that promotes the benefits of efficiency, transparency, and solutions for interrelated risks. ERM can be used as a suitable tool to address these issues (Naik & Prasad, 2021:33). Employing ERM helps to confirm the soundness of reporting events and prevent risks to the reputation of the organisation (Heong et al., 2108:84). Organisations that build a well-integrated ERM process into their strategic directions and day-to-day activities can exhibit greater ability to handle risks within the whole organisation and, as a result, can improve firm value (Prewett & Terry, 2018:17).

The amount of resources and time needed to respond to the risk and the inevitable crisis that might occur due to not implementing the ERM programme far outweigh those needed for prevention. The resources and time required to recover the losses resulting from public trust and confidence is enormous (Brandt, 2018:30). ERM plays a role in corporate governance by managing all corporate risks in an integrated manner and increasing the probability of attaining the strategic and operational objectives of organisations by supporting decision-making (McShane, 2018:137). It is important to consider all risks that affect the firm’s performance to achieve the expected benefits of ERM and facilitate effective operational and strategic decision-making (Lin et al., 2017:346).

Banks are complicated financial firms engaging in intermediation activities with risks such as liquidity risk, credit risk, market risk, interest rate risk, systemic risk, operational risk, as well as performance risk (Udoka & Orok, 2017:69). Dabari, Kwaji, and Ghazali (2017:4) also argued that the banking business is more complex and the measures to mitigate risk exposures have become crucial for their survival. The bankruptcy of large capital institutions following the large-scale financial crisis has severely impacted both the financial sector and the real economy (Kahramanoğlu & Koç, 2016:6). The global financial crisis of 2007-2008 was concluded by the collapse of major financial institutions (Udoka & Orok, 2017:69).

The banking sector in developing countries also has witnessed several causes of collapse, such as some banks from Nigeria and Kenya (Dabari et al., 2017:5). The banking industry was primarily affected by these crises, and this situation has increased the interest of banks towards risk management (Kahramanoğlu & Koç, 2016:6). The failures of risk management were mostly considered as one of the main reasons for the global financial crisis (Bates, 2010:23). The adoption of ERM in financial institutions needs to include four fundamental processes to make it integrated and holistic. This comprises the establishment of an ERM strategy, aligning the ERM strategy with a particular threat, identifying all risks facing financial institutions, building risk management infrastructure, and creating an ERM environment (Olayinka et al., 2017:940).

Some researchers have investigated the implementation of ERM functions in financial institutions. Kahramanoğlu and Koç (2016:6) studied the ERM practices in the Turkish banking sector, and the result of the study revealed that most of the banks have allocated budgets for the ERM function, which is an indicator of the banks’ concern with risk management. Similarly, Udoka and Orok (2017:68) investigated the ERM practice in Nigerian banks and the study showed that there are different hindrances that highly affect the degree of acceptance and the level of ERM implementation in Nigerian banks. The government policies on ERM have a significant influence on the level of ERM implementation by Nigerian banks, and the acceptance and implementation of ERM have a positive influence on the performance of the banks. Beasley et al. (2005:521-522) examined the determinants of the stage of ERM implementation at various U.S. and international companies. The study revealed that the stage of ERM implementation is correlated with the type of industries, and it is positively related to the banking industry. Seik, Yu, and Li (2011:7) also investigated the effects of ERM programmes on publicly traded U.S. insurance companies during the financial turmoil. The result of their study revealed that all ERM programmes are not valuable but only well-designed once.

The recent regulatory developments following the financial crisis have increased the relevance of holistic ERM frameworks for financial institutions (Bohnert et al, 2019:234). There are various factors that drive the implementation of ERM. Another strand of literature has identified several variables that are detrimental to the implementation of ERM. The increase of local and international regulatory pressures and internal organisational factors such as the availability of growth opportunities, poor earnings performance, and the anticipated likelihood of financial distress and its implicit and explicit costs make a significant contribution in moving organisations to adopt ERM (Khan et al., 2016:1886). Arnold et al. (2015:2) also noted that the shift of the risk management process from a rudimentary focus to a strategic approach is influenced by various factors involving current marketplace volatility, competition, globalisation, the level of stakeholder aversion to uncertainty, and compliance mandates. To implement the ERM system successfully, it is important to get strong support from the management, create risk awareness across the enterprise, and have the parties participate in the process (Oliveira, Méxas, Meiriño & Drumond, 2019:1015-1016).

The study conducted by Yazid, Razali, and Hussin (2012:80) proposes seven factors that influence an organisation to adopt ERM: the appointment of a CRO, turnover, profitability, leverage, size, international diversification, and institutional ownership. On the other hand, Eckles et al. (2014:247) argued that the adoption of ERM is related to diversification, institutional ownership and stock volatility. Furthermore, Sprcic, Kozul, and Pecina (2015:776) revealed that the maturity level of ERM implementation is mainly related to investment opportunities and firm size. Khan et al. (2016:1887) also identified the variables that encourage organisations to in place ERM as the risk management practice of the company, internal control, and external and internal drivers that force them to enhance the role of corporate governance.

Furthermore, Khan et al. (2016:1888-1891) identified various factors that motivate organisations to implement ERM in a set of external factors and internal factors. The external factors generally comprise the increasing number of local and international regulations. It involves the guidelines and standards of organisations for employing and integrating their risk management practices. The major external factors that motivate organisations to implement ERM are industry consolidation and deregulation, globalisation, and technological progress that create better risk analysis and quantification. In addition, the major internal factors that influence companies to implement ERM are the possibility and the estimated costs of financial distress, the presence of growth prospects and high research and development levels, capital structure and market performance, and corporate governance-related factors.

The development and acceptance of ERM have arisen from a reaction to the speedy growth caused by globalisation and regulatory forces on firms to enhance their risk management practice in a holistic approach. In recent years, its essentiality increased intensely due to continual financial scandals, corporate fraud, growing sophistication of risks and regulatory pressure (Shad et al., 2019:415). Bohnert et al. (2019:238) also documented the five firm characteristics that determine ERM implementation of insurance companies, as firm size, financial leverage, capital opacity, financial slack, and stock price and cash flow volatility.

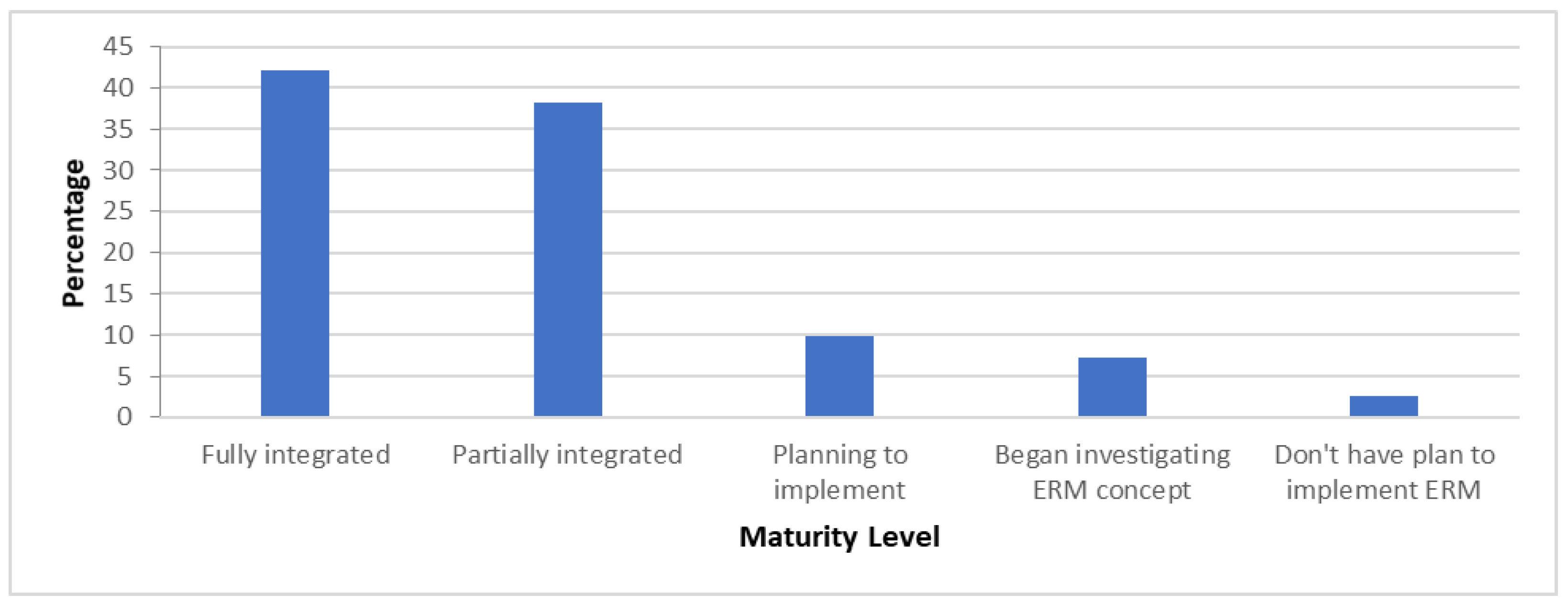

The outcome of ERM depends on the maturity of its implementation. Organisations that engage a mature ERM function realise higher operational performance than those that employ a less mature ERM function. Organisations that have a matured ERM function can achieve better performance (Mardessi & Arab, 2018:445; Farrell & Gallagher, 2019:616). The level of ERM implementation is influenced by different factors (Beasley et al., 2005:521). Various types of ERM implementation stages are defined by different authors.

Yazid et al. (2011:94) developed the level of ERM implementations into three stages: planning to adopt ERM, partial ERM implementers, and complete ERM in place. Similarly, Sprcic et al. (2015:775) also published three ERM indices that help measure the maturity level of ERM development: ERM not developed, ERM moderately developed and ERM highly developed.

Beasley et al. (2005:527) also proposed five stages of ERM implementation: (1) no plans exist to implement ERM; (2) investigating ERM but no decision has been made yet; (3) planning to implement ERM; (4) partial ERM is in place, and (5) complete ERM is in place. Likewise, Beasley et al. (2015:228) have identified five stages of ERM growth as very immature, developing, evolving, mature, and robust. Very immature firms have no plans to implement ERM and no ERM process is in place. Developing is when companies are presently studying the ERM concepts but have not yet decided to implement them. Evolving is when firms have no formal ERM process but plan to put one in place. Mature ERM is when organisations implement a partial ERM process but all risk areas are not addressed, and robust ERM is when organisations implement a complete formal ERM process. Based on the above two proposals, the first three steps are when organisations are not implementing the ERM process, and the last two steps are when companies are implementing the ERM processes.

Similar to the above developments, Oliva (2016:66) proposed five maturity levels of ERM implementation: insufficient, contingency, structured, participative, and systemic ERM. Insufficient ERM is when firms with little understanding have no conceptual or physical structure dedicated to enterprise risks and no structured approach to adopting risk management practices. Contingency ERM includes organisations that have an awareness of risks that can affect them, and they roughly apply risk management methods, tools, and techniques. In the contingency stage, risk management is centralised, and the overall participation of employees is low. At the structured ERM stage, organisations have a greater level of process related to ERM and use more intense risk management methods, tools, and techniques. Participative ERM includes organisations that have high awareness and structure about ERM processes and centralised risk management functions. This level of ERM is conducted with the involvement of most employees, and communication is a fundamental part of the risk management function.

Based on Oliva’s (2016:78) explanation, the highest matured level of ERM is systemic ERM. At this level, organisations involve structured, conscious, and transparent ERM. To enhance their risk management, these organisations drew support from research institutions, partners, and consulting firms. Furthermore, their risk assessment function includes assessing the risk environments beyond their sovereignty.

Different from the above approaches, Ahmad, Ng, and McManus (2014: 544) identified six stages of the ERM implementation measurement instrument. The proposed stages are: not considering ERM, rejecting the ERM concept, currently investigating the concept of ERM but have not made decisions yet, no formal ERM process in place but have plans to implement one, partial ERM process in place, and complete ERM process in place. The stages starting from one to four are taken as non-adopted, but stages five and six are considered as ERM adopters. Stage five shows partial employment of ERM, but stage six exhibits a complete ERM implementation.

In addition, Olive (2016:78) has proposed three parameters to assess the maturity level of ERM implementation. These are (1) the transparency in the communication of potential risks; (2) risk assessment in the environment of value; and (3) the participation of external agents in risk management. Ahmad et al. (2014:545) noted that the integration of ERM with corporate strategy planning and decision-making processes demonstrates the full or complete implementation of ERM functions. Organisations with a medium degree of ERM maturity have an ERM function with a high level of structure and use techniques with a higher decentralisation (Oliva, 2016:78).

A well-designed ERM programme resulted in better performance, while weak ERM programmes are destructive since their implementation is incomplete and the overall programme is not integrated with the business strategic planning processes (Seik, Yu & Li, 2011:7). There is a higher gap between the current stage of ERM implementation and the expected future maturity level of banks ERM functions. This creates a higher need for ERM infrastructure to facilitate the enhancement of ERM capabilities over time (Dabari et al., 2017:5). In placing formal risk management policies and providing training on risk management for key business unit managers and senior executives, promote firms to establish a mature ERM function (Beasley et al., 2015:221). Beasley et al. (2015:221) also noted that more mature ERM functions might be developed by forming a management-level risk committee, including the senior executives that can deliver direction to business unit managers for assessing the influence of risk events.

Despite the importance of risk management growing, there is a lack of information on the maturity level of ERM implementation in the banking sector, mainly in developing economies (Oyede et al., 2019:2). Lundqvist and Vilhelmsson (2018:127) examined the association between level of ERM implementation and default risk with the 78 world largest banks. The results of the study revealed that the maturity level of ERM implementation is adversely associated with the level of default risk. Seik, Yu, and Li (2011:7) also investigated the effects of ERM programmes on publicly traded U.S. insurance companies during the financial turmoil. The result of their study revealed that all ERM programmes are not valuable but only well-designed once. Companies that established quality ERM programmes had higher profitability and lower stock volatility compared with weak-ERM performers and non-ERM peers. Dabari et al. (2017:13) also examined the adoption of ERM in Nigerian banks, and the results of the study revealed that the Nigerien banks have completely in-place ERM. The study also showed that human resource competency, internal audit effectiveness, and top management commitment also have a positive relationship with the maturity level of ERM in Nigerian banks.

The global financial crisis of 2008/09 exhibited that the risk management of various enterprises was weak. Consequently, financial regulators promote ERM to support the risk management of organisations and show that they are taking actions to enhance risk management. Following that, the ERM practice was expected to be widely initiated, implemented, and mature; nevertheless, the progress has been unsatisfactory. Some firms started and failed; some are still ready to try it; and several of those who begin are striving and undertaking only a few activities (Fraser & Simkins, 2016:690). Even implementing ERM has improved shareholders’ value with the adoption of a holistic risk management approach related to extensive costs. These include the hiring of CROs, instituting a board risk committee, building a risk culture all over the enterprise, and outspreading exertions about public relations. However, firms that implement ERM can improve their shareholders’ value since the benefits exceed the cost of ERM adoption (Bohnert et al., 2019:237). Arnold et al., (2015:4-5) also noted that ERM is mostly troubled by a shortage of systems-level integration needed to get information simply and mitigate risks within the entire organisation. Without the integration of systems and data, the top management is not able to take a holistic view of risk management for risks faced by enterprises.

The regulatory bodies of various developed countries pressuring institutions to enhance their risk management functions and risk disclosure practices. Some of the regulatory pressures are the UK Corporate Governance Code, the Dutch Corporate Governance Code, the NYSE Corporate Governance Rules, and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) in the U.S. These codes are practiced on publicly listed companies and request firms establish an effective risk management system (Paape & Spekle, 2012:538).

The literature related to ERM has shown progress in developed economies; however, there is a remarkable lack of literature in developing economies that investigated the influence of ERM on the performance of financial institutions (Olayinka et al., 2017:938). In recent years, various organisations from developing countries have begun to adopt a holistic and an integrated approach to risk management (Anton, 2018: 151). ERM has a different influence on organisations from developing and developed countries due to the variation in financial systems and regulations (Chen et al., 2020:10). The interest in studying risk management has shown a growing trend all over the world as a result of various economic conditions. These economic conditions have shown that the frequent global financial crisis underlined the essential of the risk management function (Olayinka et al., 2017:937).

The 2008 financial crisis, which overwhelmed the entire financial world, had a spillover influence on the financial systems of emerging economies. The regulatory institutions to safeguard the financial institutions have to ensure that all organisations in the institution implement ERM as soon as possible and carry out to confirm strict compliance with the ERM framework. The implementation of ERM in developing countries is also significantly associated with the financial performance of organisations similar to those in developed economies (Olayinka et al., 2017:937-938).

In the process of financial intermediation, banks are exposed to financial and non-financial risks. These risks are interrelated, and the risk occurrence in either area can influence the magnitude of other risks (Attarwala & Balasubramaniam 2015:10). The three (3) major risks that face all banks are credit risk, liquidity risk, and operational risk (Elbadry, 2018:123). The types of risks to which organisations are exposed can be classified as financial and operational risks (Bessis, 2012:26-27; Attarwala & Balasubramaniam, 2015:10). The financial risks consist of liquidity risk, credit risk, mismatch risk, foreign exchange risk, interest rate risk, and solvency risk. However, risks can also be classified as hazard, financial, operational, and strategic risks (McShane, 2018:137).

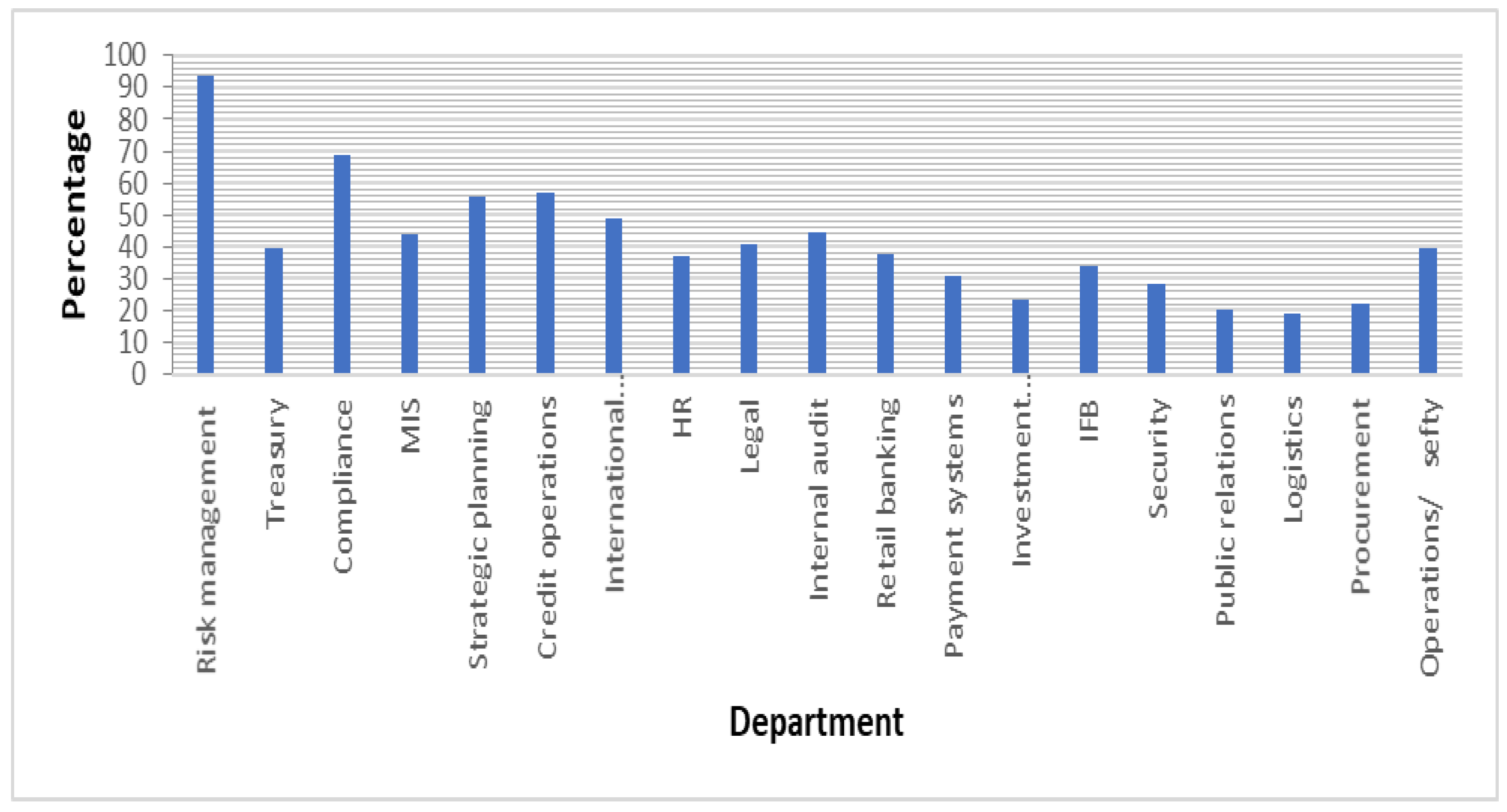

In less monetised countries such as Ethiopia, banks dominate the financial sector. The major financial institutions in Ethiopia are banks, contributing significantly to the economic growth and development of the country (Tade & Negera, 2017:47). In Ethiopia, commercial banks are playing a fundamental role as financial intermediaries for the economic growth and development of the country by transferring idle funds from depositors to borrowers for investment (Kossa & Pasha, 2016:89). The status of risk management practices in Ethiopian banks showed that risk management programmes and strategies are not documented as required and risk management documents are not reviewed regularly.

Ademe (2015) has investigated ERM practices in Ethiopian private banks. The study revealed that the ERM practice of Ethiopian banks is in the infant stage. In addition, most Ethiopian banks either do not establish the risk management programme needed by NBE at all or fail to establish a comprehensive risk management programme. Alemu (2020) also examined the ERM function in Ethiopian banks. The study found that almost all Ethiopian commercial banks do not have adequate awareness of enterprise level risk management practices. The study also found that the major challenges facing banks to manage their enterprise-level risks are a weak tone at the top and less attention from top management, the absence of workable environments, the absence of qualified staff, and the absence of advanced risk management software. The study conducted by Tsige and Singla (2019:5289) also revealed that the implementation of ERM in Ethiopian financial institutions is low and it is in the infant stage and these financial institutions have a less developed ERM practice compared with the international organisations.