Submitted:

09 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

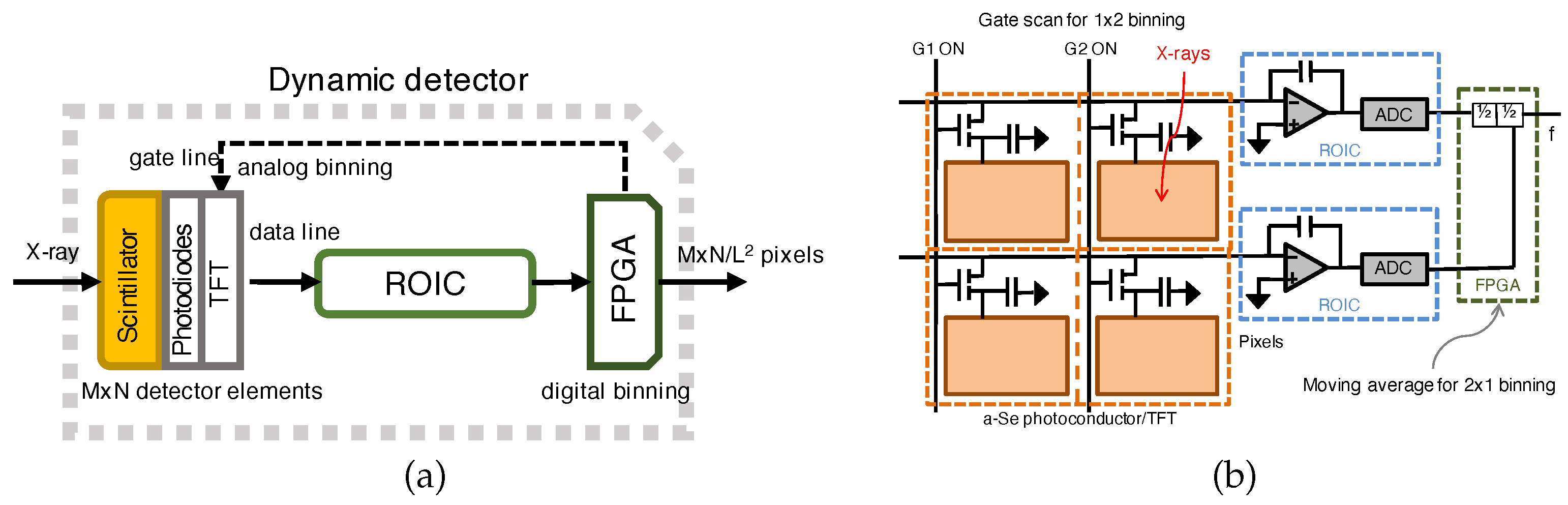

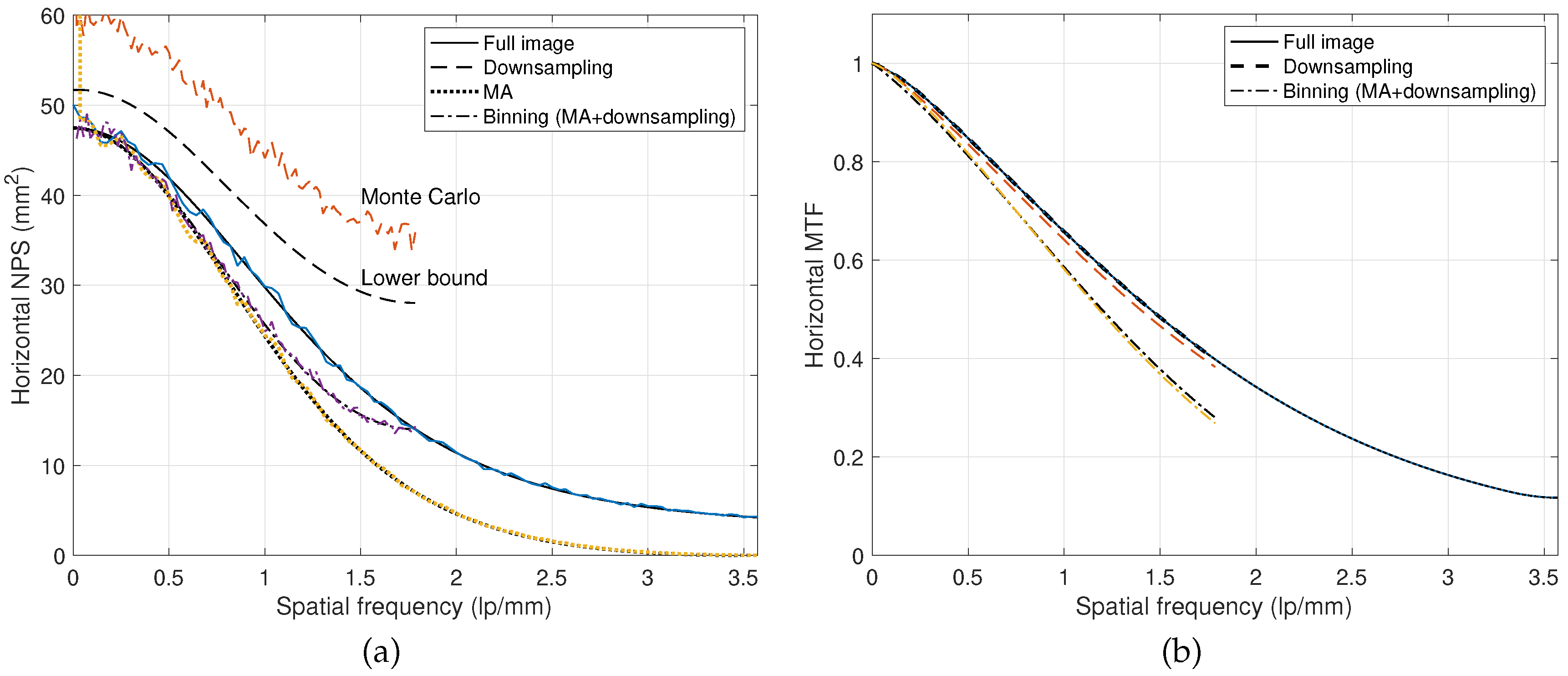

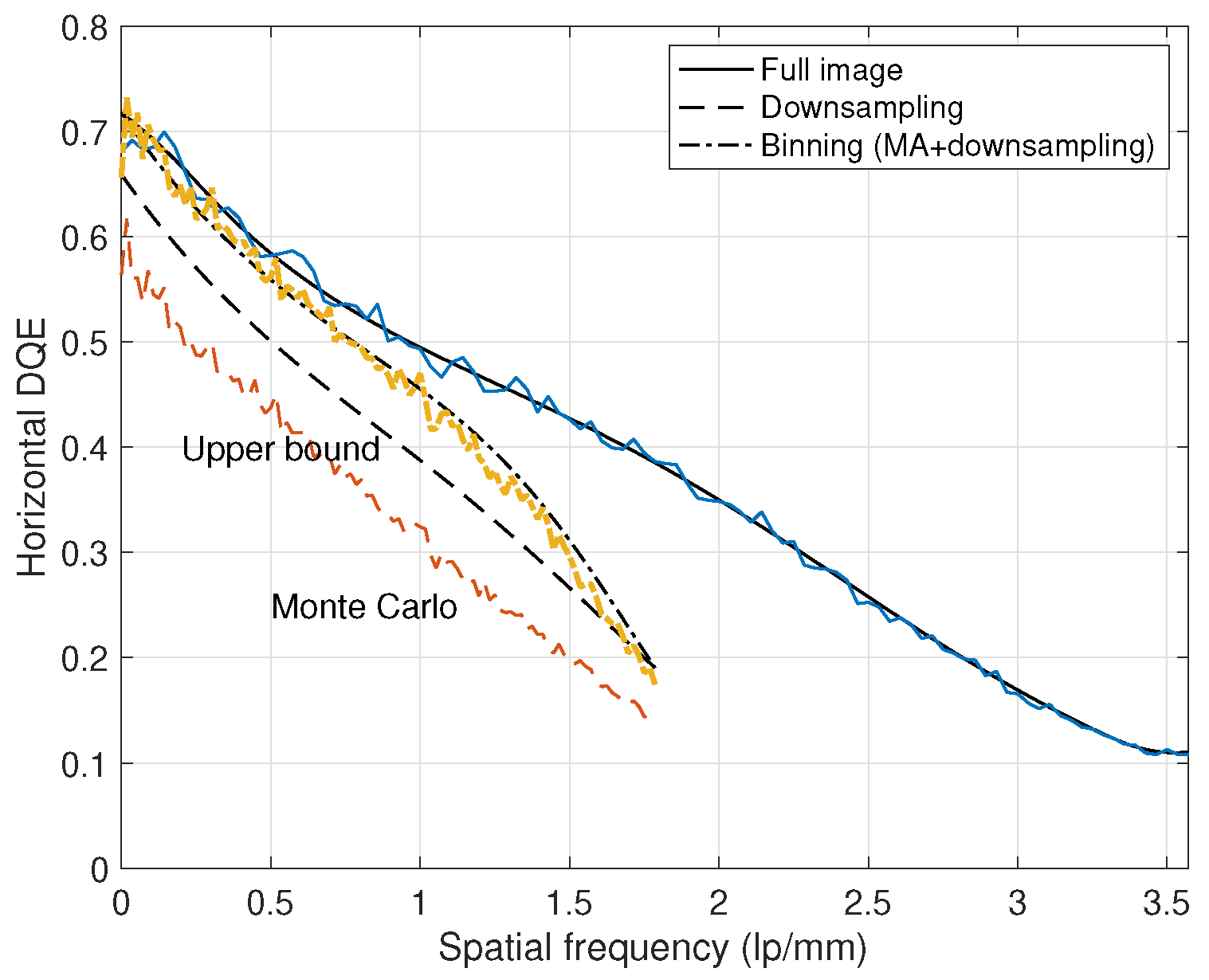

2. Detective Quantum Efficiency in Pixel Binning

2.1. Detective Quantum Efficiency

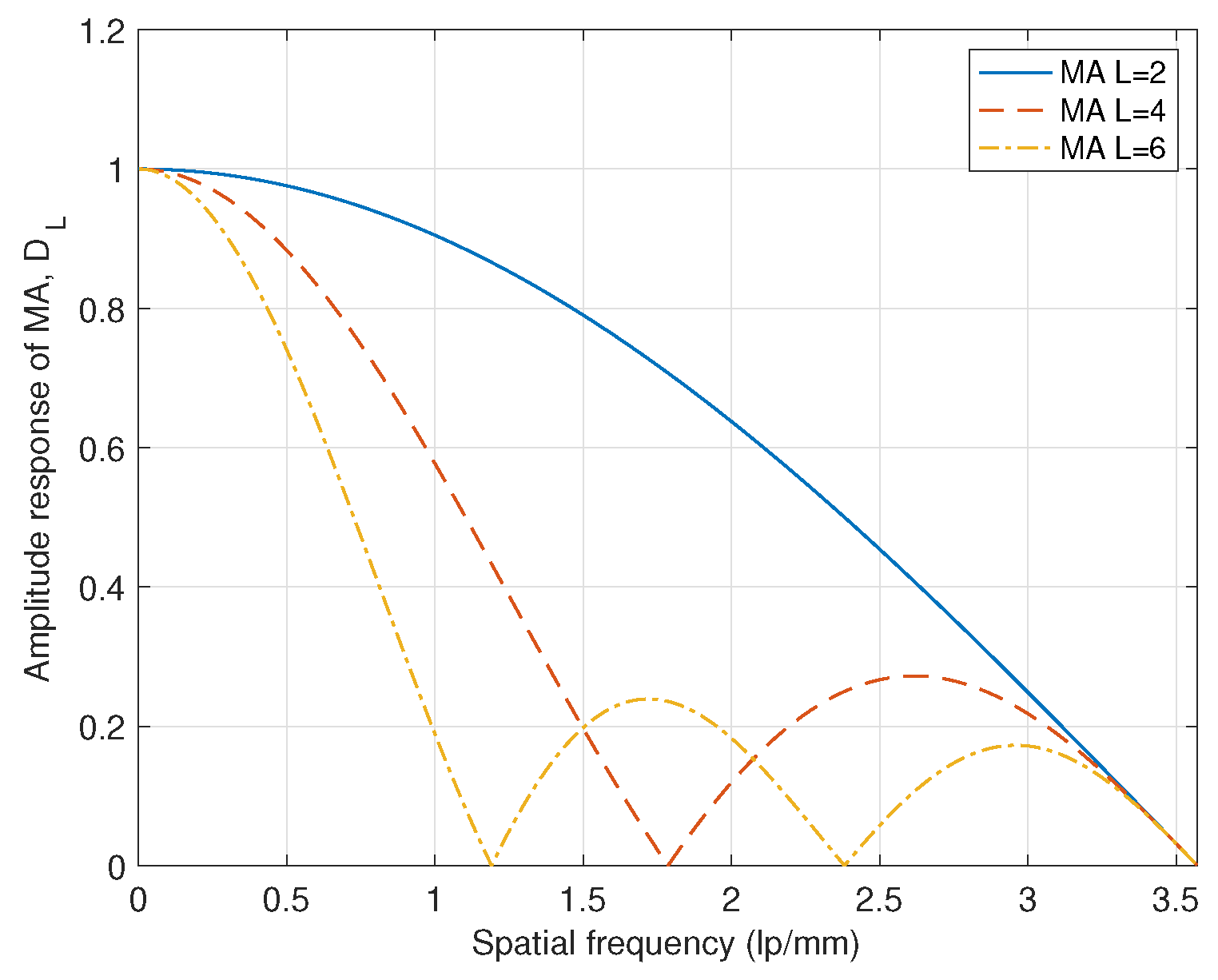

2.2. Moving Average Model for Pixel Binning

3. Simulations and Experimental Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DQE | Detective quantum efficiency |

| LPF | low-pass filter |

| MTF | Modulation transfer function |

| NNPS | Normalized noise power spectrum |

| NPS | Noise power spectrum |

| ROIC | readout integrated circuit |

| SNR | signal-to-noise ratio |

| TFT | Thin-film-transistor |

| C | Detector transfer function |

| Sampling frequency (lp/mm) | |

| P | NPS |

| L-binning NPS | |

| Q | DQE |

| L-binning DQE | |

| T | MTF |

| x, y | Weakly stationary sequences |

| x-ray photons per square meters | |

| Detector gain | |

| Mean of y |

References

- Bushberg, J.T.; Seibert, J.A.; E. M. Leidholdt, J.; Boone, J.M. The Enssential Physics of Medical Imaging, 2nd. ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, 2002.

- Tanaka, R. Dynamic chest radiography: flat-panel detector (FPD) based functional X-ray imaging. Radiol. Phys. Technol. 2016, 9, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hata, A.; Yamada, Y.; Tanaka, R.; Nishino, M.; Hida, T.; Hino, T.; Ueyama, M.; Yanagawa, M.; Kamitani, T.; Kurosaki, A.; Sanada, S.; Jinzaki, M.; Ishigami, K.; Tomiyama, N.; Honda, H.; Kudoh, S.; Hatabu, H. Dynamic chest x-ray using a flat-panel detector system: technique and applications. Korean Jour. Radiology 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyles, F.; Fitzmaurice, T.; Robinson, R.; Bedi, R.; Burhan, H.; Walshaw, M. Dynamic chest radiography: a state-of-the-art review. Insights into imaging 2023, 14, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, R.C.; Woods, R.E. Digital Image Processing, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: NY, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim, A.V.; Schafer, R.W. Discrete-Time Signal Processing, 3rd. ed.; Pearson Education: NJ, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dowski, E.R.; Cathey, W.T. Modern wavefront-based optical anti-aliasing filter. International Optical Design Conference. Optica Publishing Group, 1998, p. LFB.4. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Yu, F. Characteristic-analysis of optical low pass filter used in digital camera. ICO20: Optical Design and Fabrication. SPIE, 2006, Vol. 6034, p. 60340N. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.L.; Cheung, L.K.; Jeromin, L.S. A new digital detector for projection radiography. SPIE, 1995, Vol. 2432, pp. 237–249. [CrossRef]

- Samei, E.; Flynn, M.J. An experimental comparison of detector performance for direct and indirect digital radiography systems. Med. Phys. 2003, 30, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, H.C.; Hunt, B.R. Digital Image Restoration; Prentice-Hall: NY, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, G.M.; Watts, D.G. Spectral Analysis and Its Applications; Holden-Day: San Francisco, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Papoulis, A. Probability, Random Variables, and Stochastic Processes, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill: NY, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.S. Noise power spectrum measurements in digital imaging with gain nonuniformity correction. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2016, 25, 3712–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S. Measurements of the noise power spectrum for digital x-ray imaging devices. Phys. Med. Biol. 2024, 69, 03TR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainty, J.C.; Shaw, R. Image Science: Principles, Analysis and Evaluation of Photographic-Type Imaging Processes; Academic Press: NY, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- IEC 62220-1-1; Medical Electrical Equipment Characteristics of digital X-ray imaging devices-Part1-1: Determination of the Detective Quantum Efficiency Detectors used in Radiographic Imaging. International Electrotechnical Commission Report: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Zhao, W.; Ristic, G.; Rowlands, J.A. X-ray imaging performance of structured cesium iodide scintillators. Med. Phys. 2004, 31, 2594–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romdhane, M.S.B.; Madisetti, V.K. All-digital oversampled front-end sensors. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 1996, 3, 38–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R.W. Digital signal processing: technology and marketing for audio systems. IEE Colloquium on Digital Audio Signal Processing, 1992, pp. 15/1 – 5/6.

- Kim, D.S.; Kim, E.; Lee, E.; Shin, C.W. 2×2 oversampling in digital radiography imaging for CsI-based scintillator detectors. SPIE, 2017, Vol. 10132, pp. 101323X–1–8. [CrossRef]

- Saramaki, T.; Estola, K.P. Design of linear-phase partly digital anti-aliasing filters. IEEE Int. Conf. Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing,, 1985, pp. 65–68. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Kim, E.; Shin, C.W. Oversampling digital radiography imaging based on the 2×2 moving average filter for mammography detectors. SPIE, 2018, Vol. 10573, pp. 1057362–1–10. [CrossRef]

- Ismailova, E.; Karim, K.; Cunningham, I.A. Apodized-Aperture Pixel Design to Increase High-Frequency DQE and Reduce Noise Aliasing in X-Ray Detectors. SPIE, 2015, Vol. 9412, pp. 94120D1–8. [CrossRef]

- Nano, T.; Esartin, T.; Karim, K.S.; Cunningham, I.A. A novel x-ray detector design with higher DQE and reduced aliasing: Theoretical analysis of x-ray reabsoprtion in detector converter material. SPIE, 2016, Vol. 9783, pp. 978318–1–10. [CrossRef]

- Colbeth, R.E.; Allen, M.J.; Day, D.J.; Gilblom, D.L.; Harris, R.A.; Job, I.D.; Klausmeier-Brown, M.E.; Pavkovich, J.M.; Seppi, E.J.; Shapiro, E.G.; Wright, M.D.; Yu, J.M. Flat-panel imaging system for fluoroscopy applications. Medical Imaging 1998: Physics of Medical Imaging. SPIE, 1998, Vol. 3336, pp. 376 – 387. [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, Y.; Wilson, D.L. Quantitative image quality evaluation of pixel-binning in a flat-panel detector for x-ray fluoroscopy. Medical Physics 2004, 31, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, Y.; Wilson, D. Image quality evaluation of flat panel detector binning in x-ray fluoroscopy. IEEE Int. Symp. Biomedical Imag., 2002, pp. 177–180. [CrossRef]

- Proakis, J.G.; Manolakis, D. Digital Signal Processing, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: NY, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, M.S. Periodogram analysis and continuous spectra. Biometrika 1950, 37, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, P.D. The use of fast Fourier transform for the estimation of power spectra: a method based on time averaging over short, modified periodograms. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoustics 1967, 15, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, D.J. Spectrum estimation and harmonic analysis. IEEE Proc. 1982, 70, 1055–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S. High precision noise power spectrum measurements in digital radiography imaging. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, 5461–5471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Lee, E. Estimation of zero-frequency noise power density in digital imaging. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2018, 25, 1755–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S. Measurement of power density at zero frequency with a trend compensation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2020, 68, 1964–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbins III, J.T.; Samei, E.; Ranger, N.T.; Chen, Y. Intercomparison of methods for image quality characterization. II. Noise power spectrum. Med. Phys. 2006, 33, 1466–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S. Convex combination of images from dual-layer detectors for high detective quantum efficiencies. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 70, 1804–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyer, J.A. Spatial frequency response of certain photographic emulsions. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1958, 48, 938–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakos, G.C.; Suryanarayanan, S.; Guntupalli, R.; Odogba, J.; Shah, N.; Vedantham, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Mehta, K.; Sumrain, S.; Patnekar, N.; Moholkar, A.; Kumar, V.; Endorf, R.E. Detective quantum efficiency DQE(0) of CZT semiconductor detectors for digital radiography. IEEE Trans. Instr. Measurement 2004, 53, 1479–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.C.; Kim, H.K.; Henry, J.H.; Cunningham, I.A. A novel method to measure the zero-frequency DQE of a non-linear imaging system. SPIE, 2011, Vol. 7961, pp. 79610C–1–7. [CrossRef]

- IEC 62220-1-2; Medical Electrical Equipment Characteristics of Digital X-ray Imaging Devices-Part1-2: Determination of the Detective Quantum Efficiency Detectors Used in Mammography. International Electrotechnical Commission Report: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- IEC 62220-1-3; Medical Electrical Equipment Characteristics of Digital X-ray Imaging Devices-Part1-3: Determination of the Detective Quantum Efficiency Detectors used in Dynamic Imaging. International Electrotechnical Commission Report: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Kim, D.S.; Lee, E. Signal lag measurements based on temporal correlations. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2021, 28, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Lee, E. Measurement of the lag correction factor in low-dose fluoroscopic imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 2021, 40, 1661–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.; Kim, D.S. Linear lag models and measurements of the lag correction factors. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 49101–49113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Kim, E. Noise power spectrum of the fixed pattern noise in the digital radiography detectors. Med. Phys. 2016, 43, 2765–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.B.; Mangiafico, P.A.; Simoni, P.U. Noise power spectra of images from digital mammography detectors. Med. Phys. 1999, 26, 1279–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, H.; Tsai, D.Y.; Itoh, T.; Doi, K.; Morishita, J.; Ueda, K.; Ohtsuka, A. A simple method for determining the modulation transfer function in digital radiography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 1992, 11, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashita, I.; Maeda, K.; Arimura, H.; Morikawa, K.; Ishida, T. Development of an automated method for evaluation of sharpness of digital radiographs using edge method. SPIE, 2001, Vol. 4320, pp. 331 – 338. [CrossRef]

- Buhr, E.; Gunther-Kohfahl, S.; Neitzel, U. Simple method for modulation transfer function determination of digital imaging detectors from edge images. SPIE, 2003, Vol. 5030, pp. 877–884. [CrossRef]

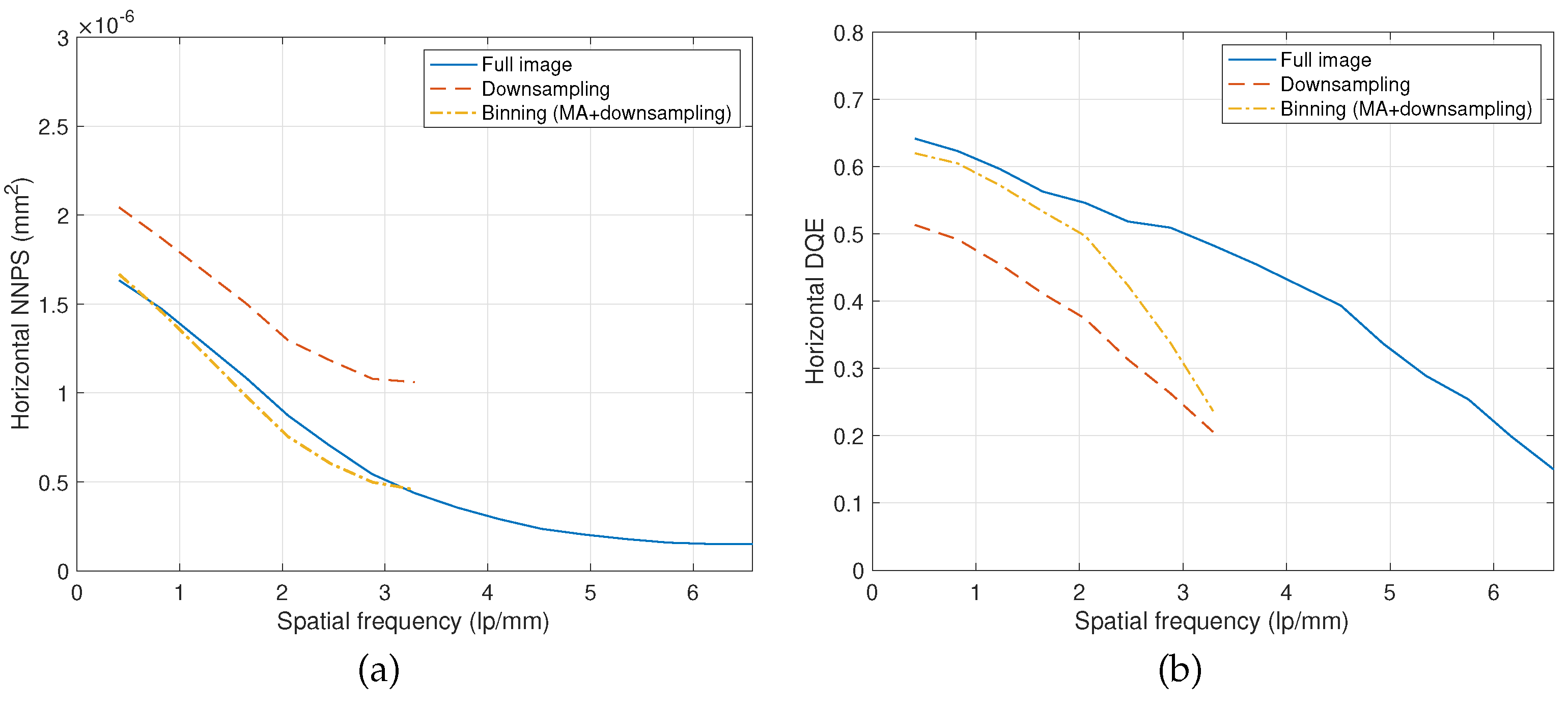

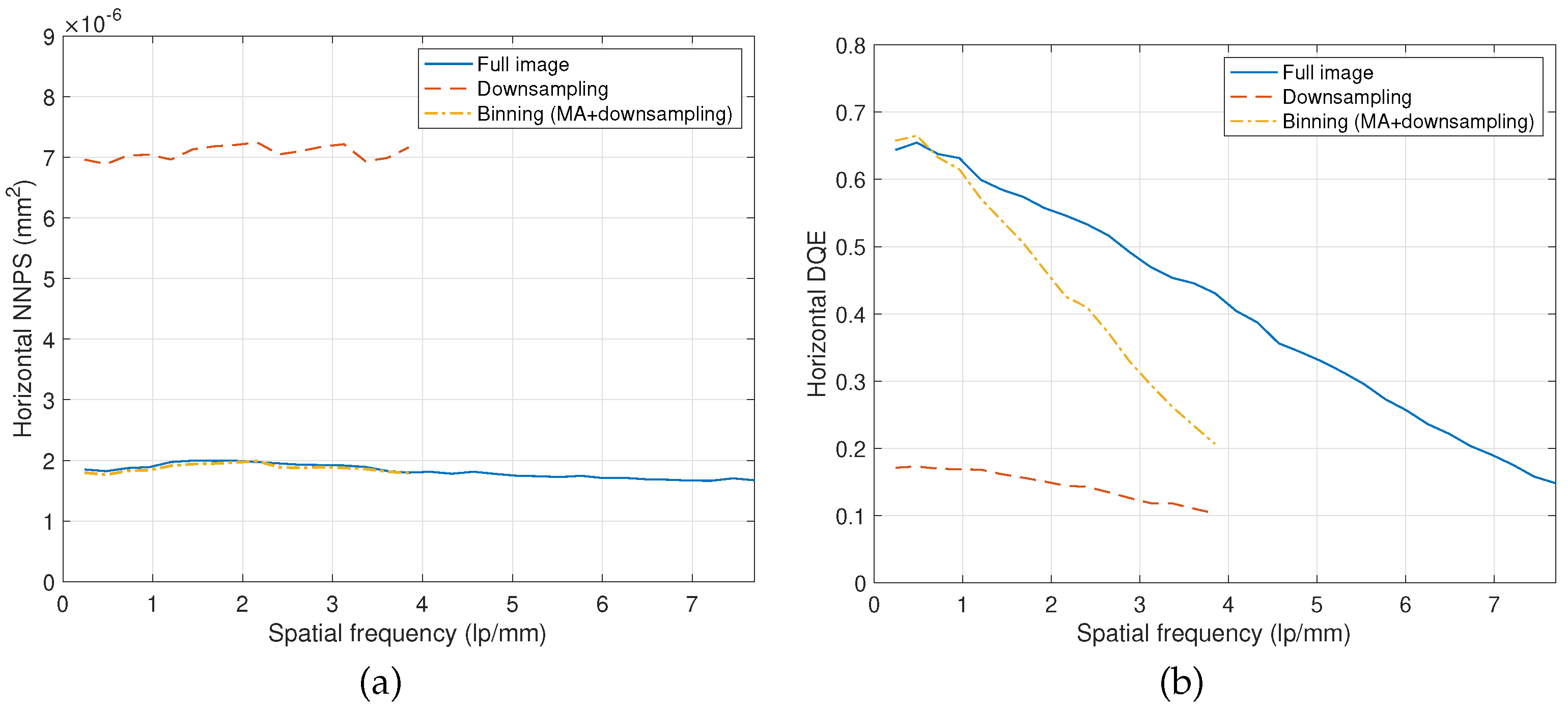

| Conversion | Scintillator | Pixel pitch | Image size | X-ray | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detector | type | or photoconductor | (m) | (pixels) | condition |

| A | Indirect | CsI:Tl (500 m) | 140 | RQA 5 | |

| B | Indirect | CsI:Tl (160 m) | 76 | RQA Mo/Rh | |

| C | Direct | a-Se (380 m) | 65 | RQA W/Rh |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).