Submitted:

11 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

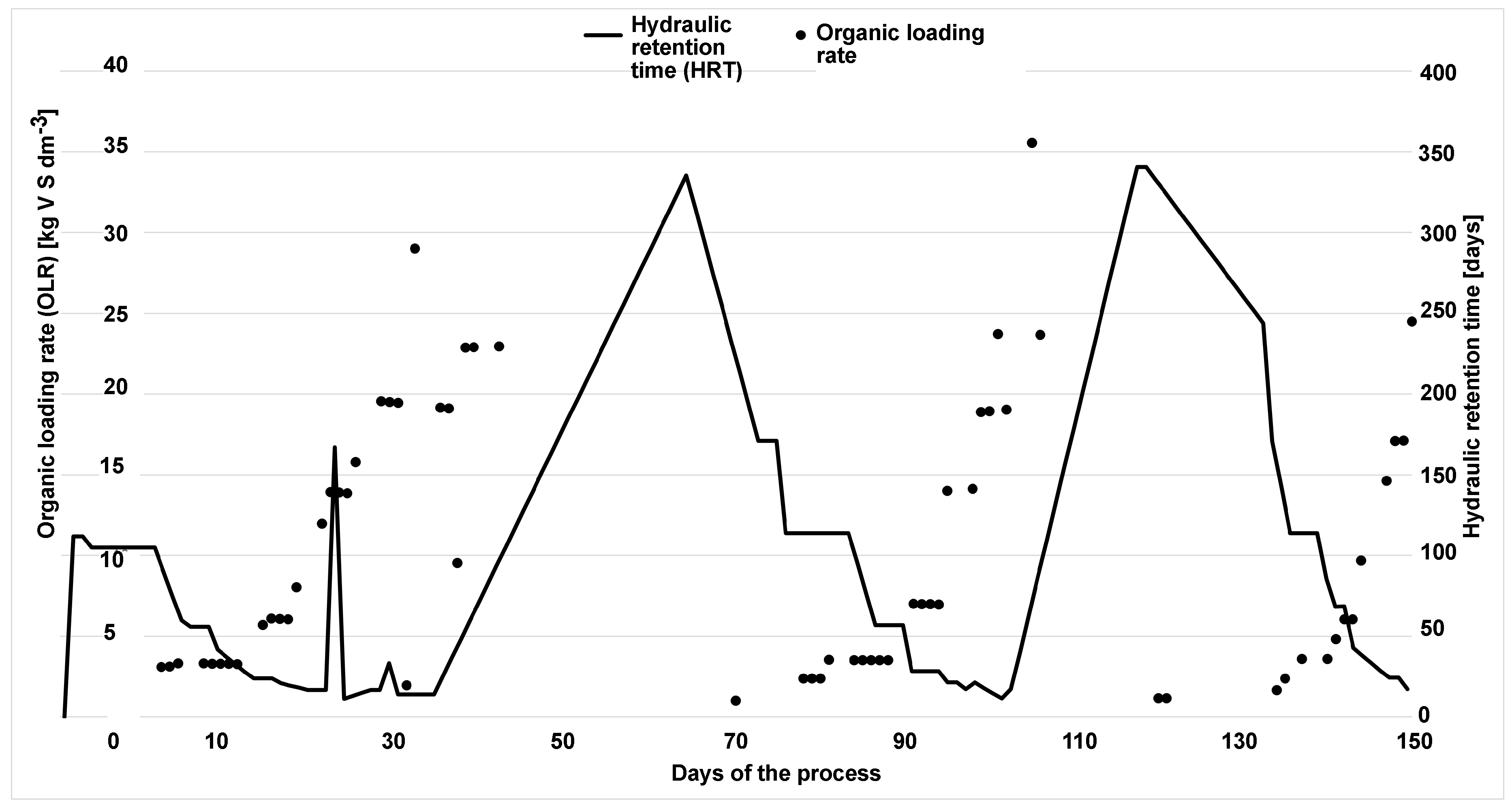

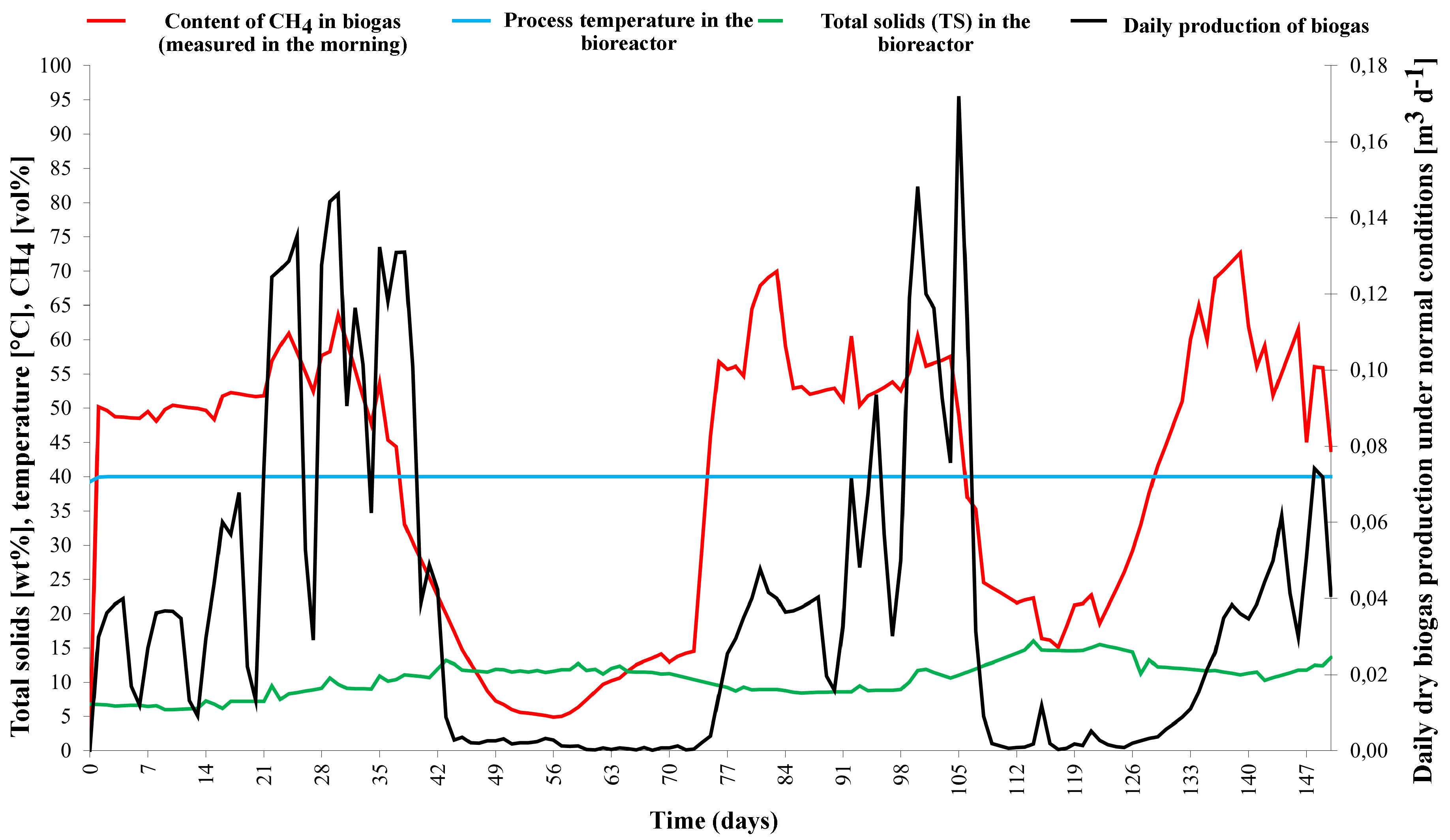

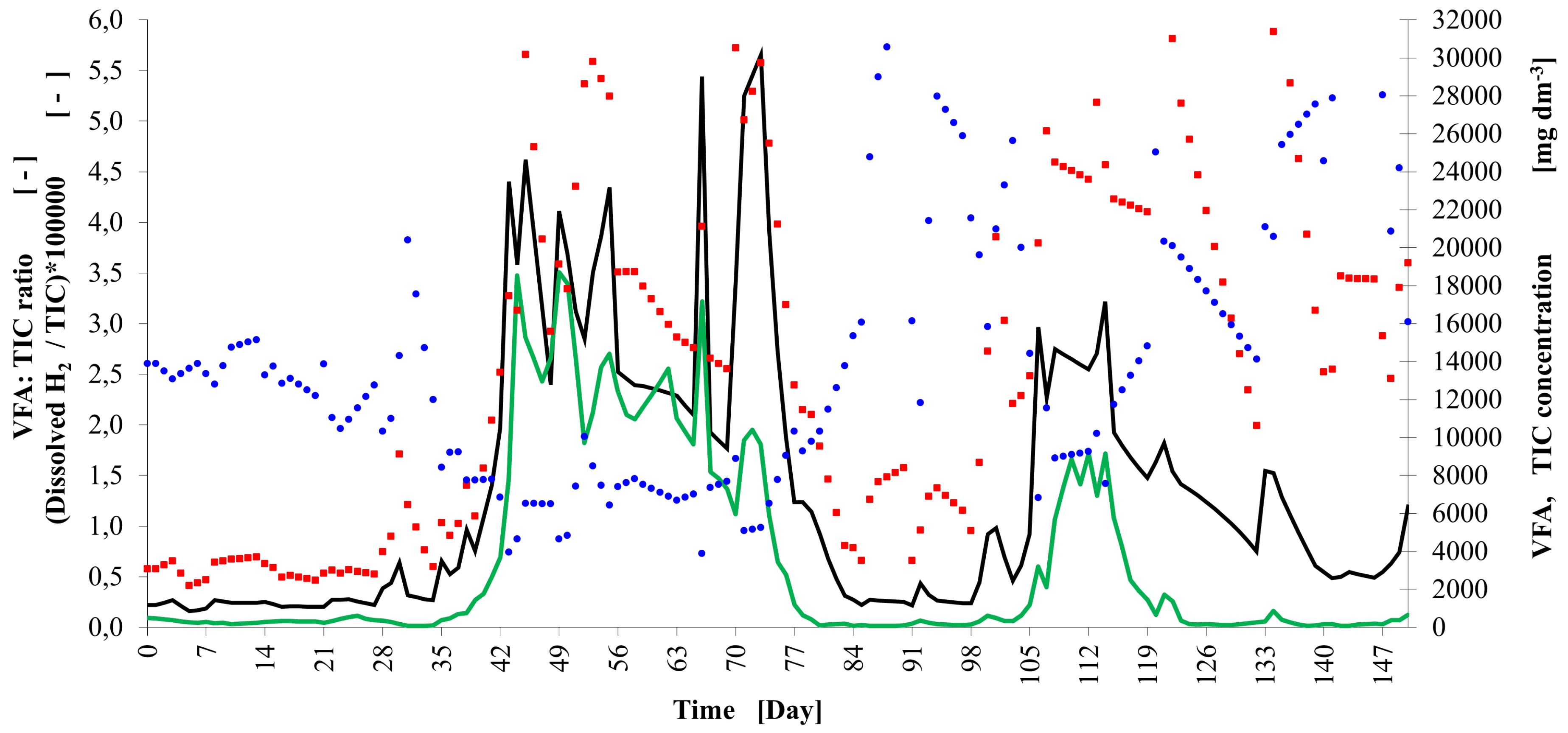

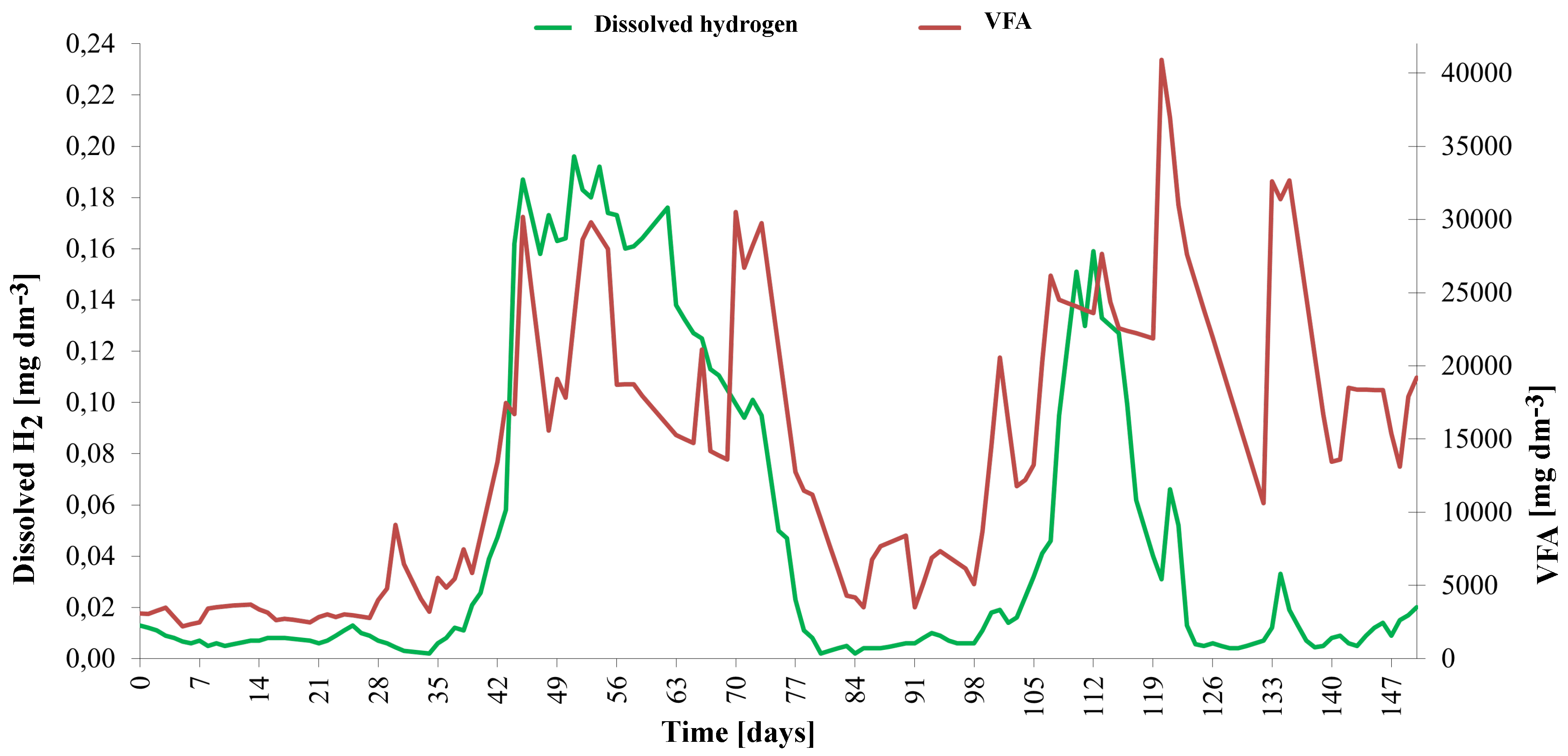

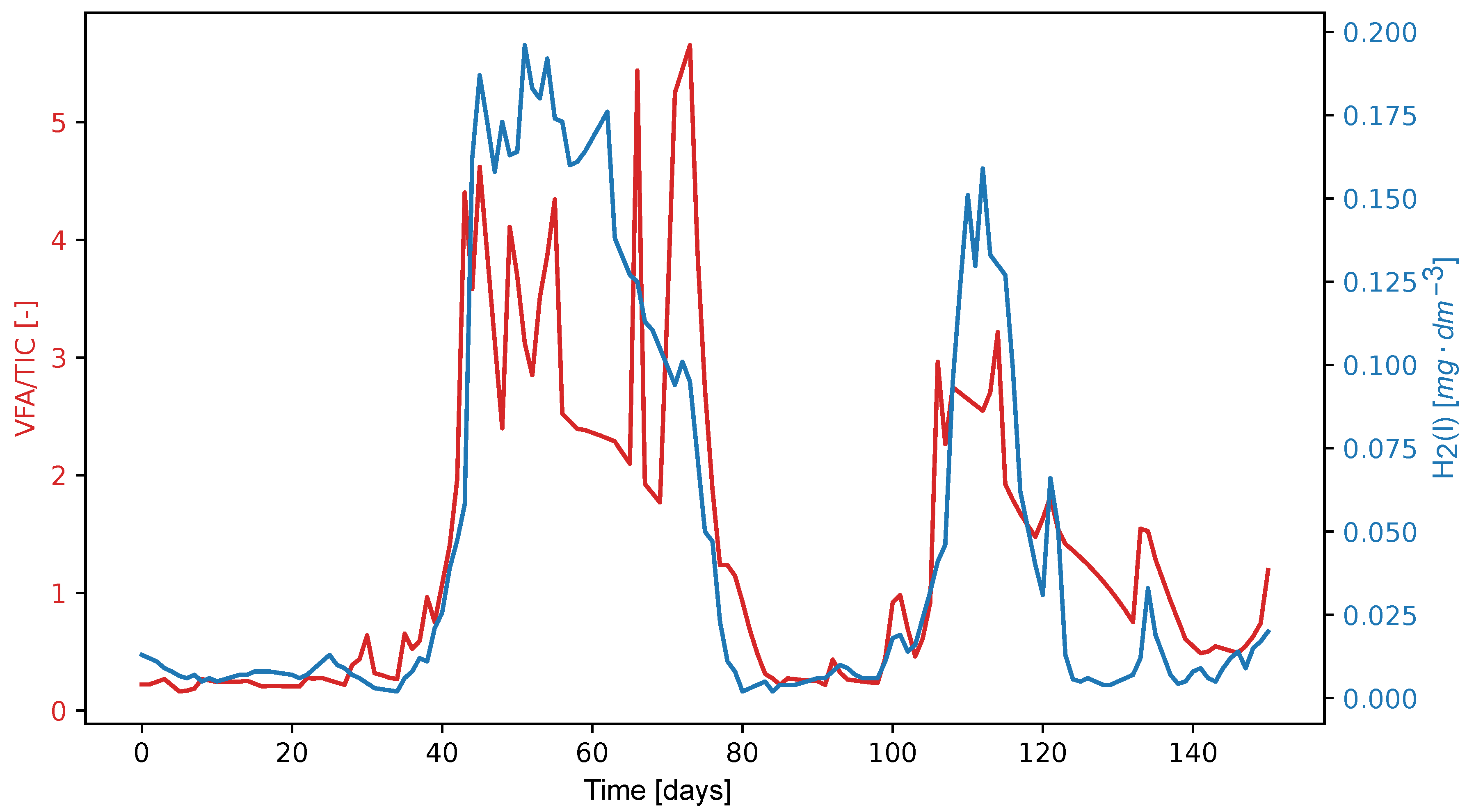

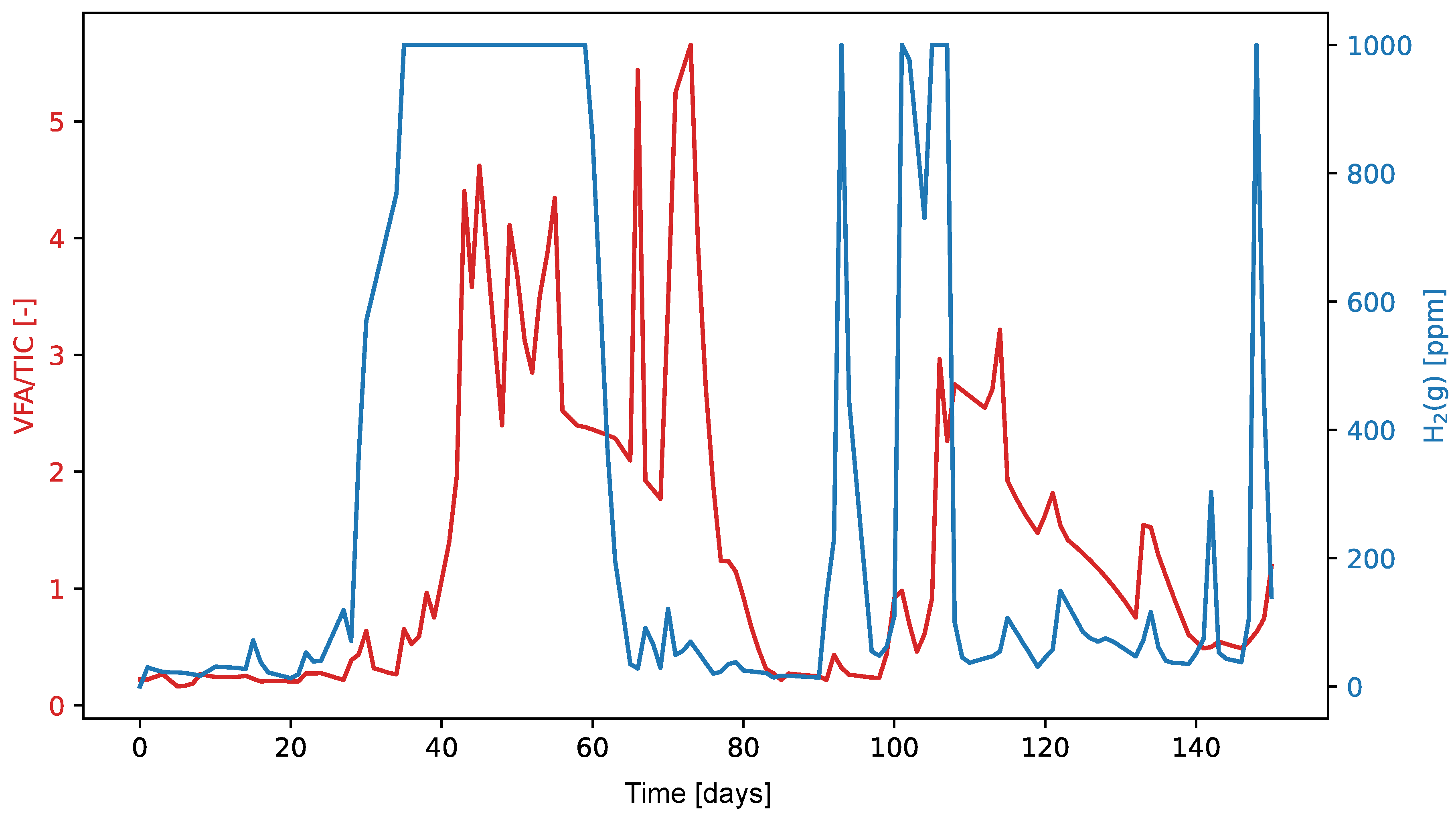

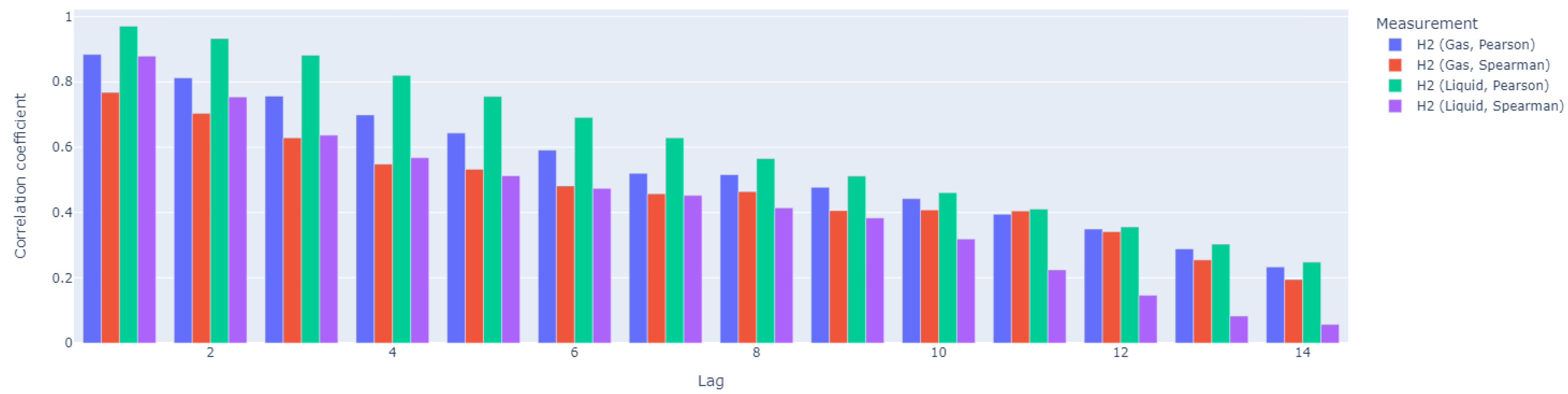

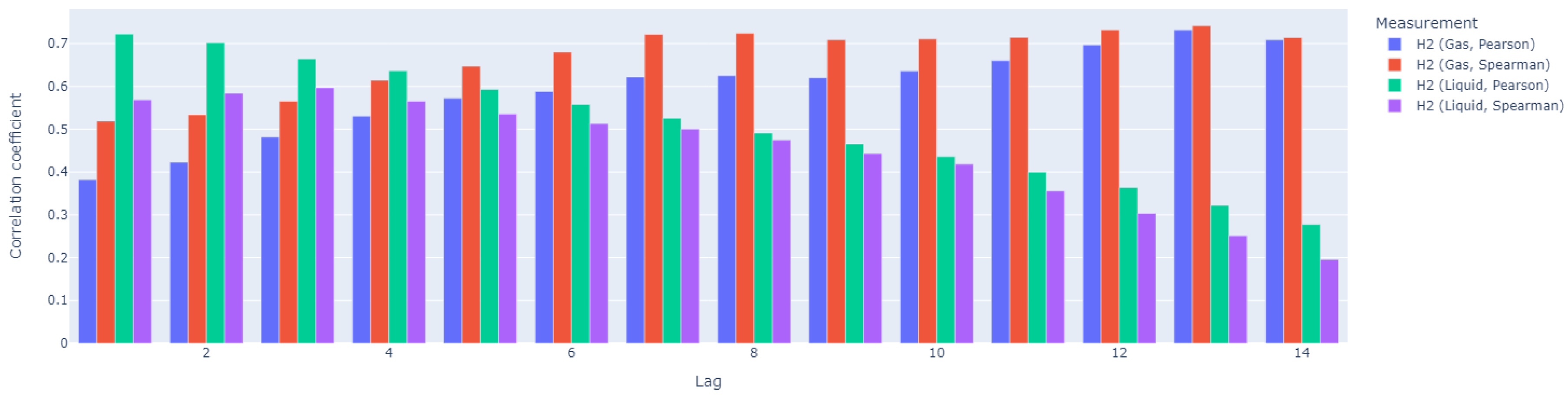

Since dissolved hydrogen is a key factor in maintaining the complex balance between microbial species that enable anaerobic digestion, we tested the ratio of dissolved hydrogen concentration to neutralization capacity as a potential alternative to the traditional VFA/TIC (alternatively FOS/TAC) stability indicator. The anaerobic digestion process was carried out in a Terrafors IS rotary drum bioreactor for 150 days at an average temperature of 40°C and an organic volatile load of 0.092 kgm−3 d−1. Corn silage was dosed on weekdays as the substrate. With a theoretical retention time of 45 days, a biogas production of 0.219 Nm3kgVs−1 with a CH4 content of 31.6 % was achieved. The values of the determined VFA/TIC stability indicator ranged from 0.22 to 5.66, with the highest values obtained when the reactor was overloaded. The dissolved hydrogen concentration ranged 0.005–0.196 mgdm−3. The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.337 and corresponded to a p-value of 0. The Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.468. The amperometric microsensor has proven to be unsuitable for field applications due to its lack of sensitivity and short lifetime. The proposed ratio of dissolved hydrogen concentration to neutralization capacity did not prove to be significantly more effective than the established VFA/TIC indicator.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Anaerobic Digestion

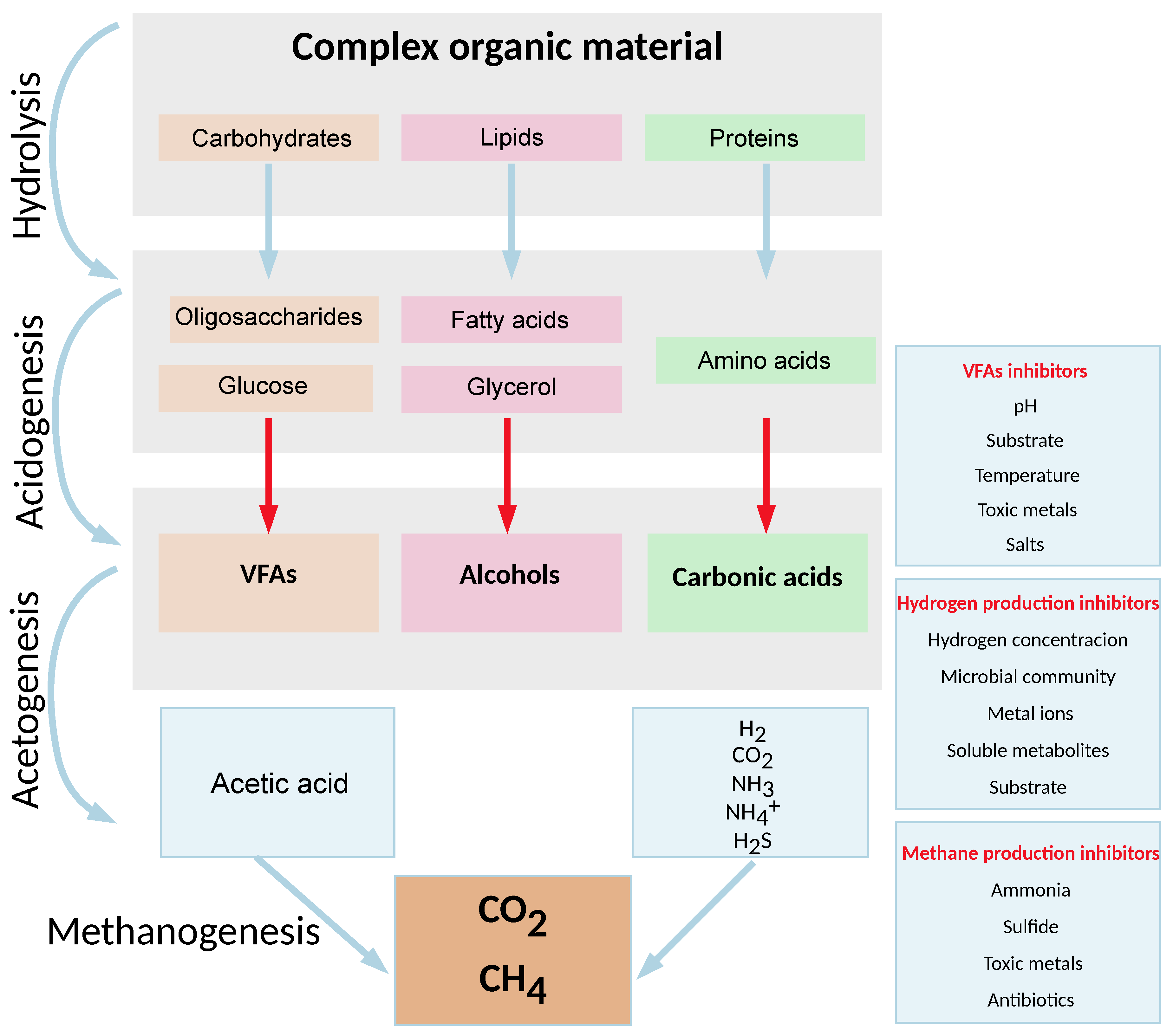

1.1.1. Phases of Anaerobic Digestion

1.2. Sensors

2. Materials and Methods

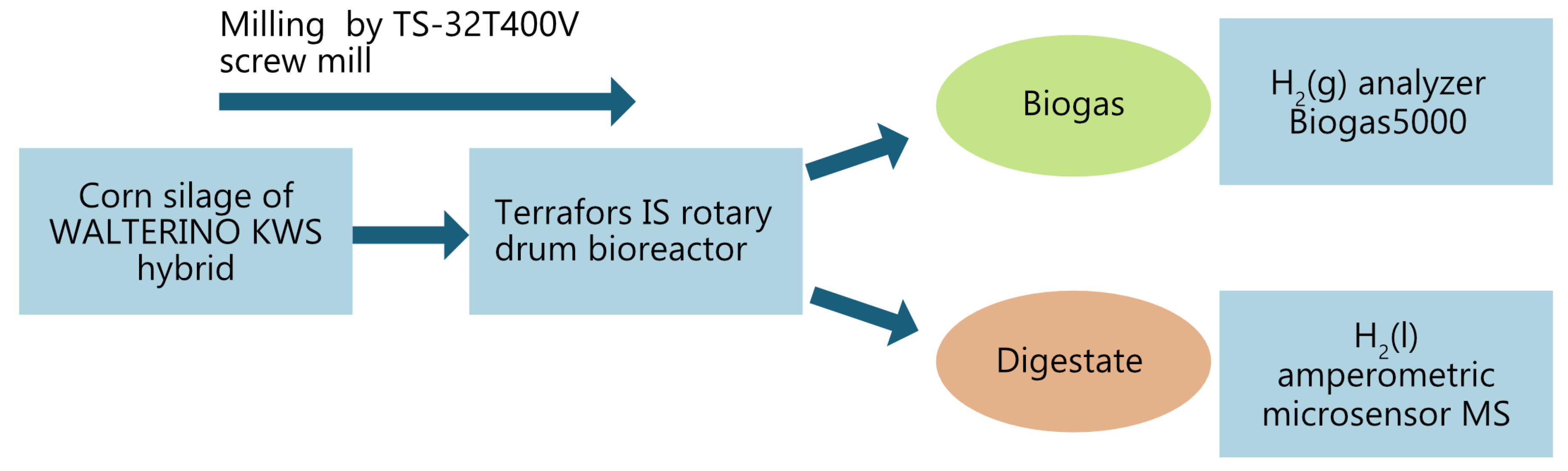

2.1. Substrate Pre-Treatment and Dosing into the Bioreactor

2.2. Monitoring the Experiment Progress

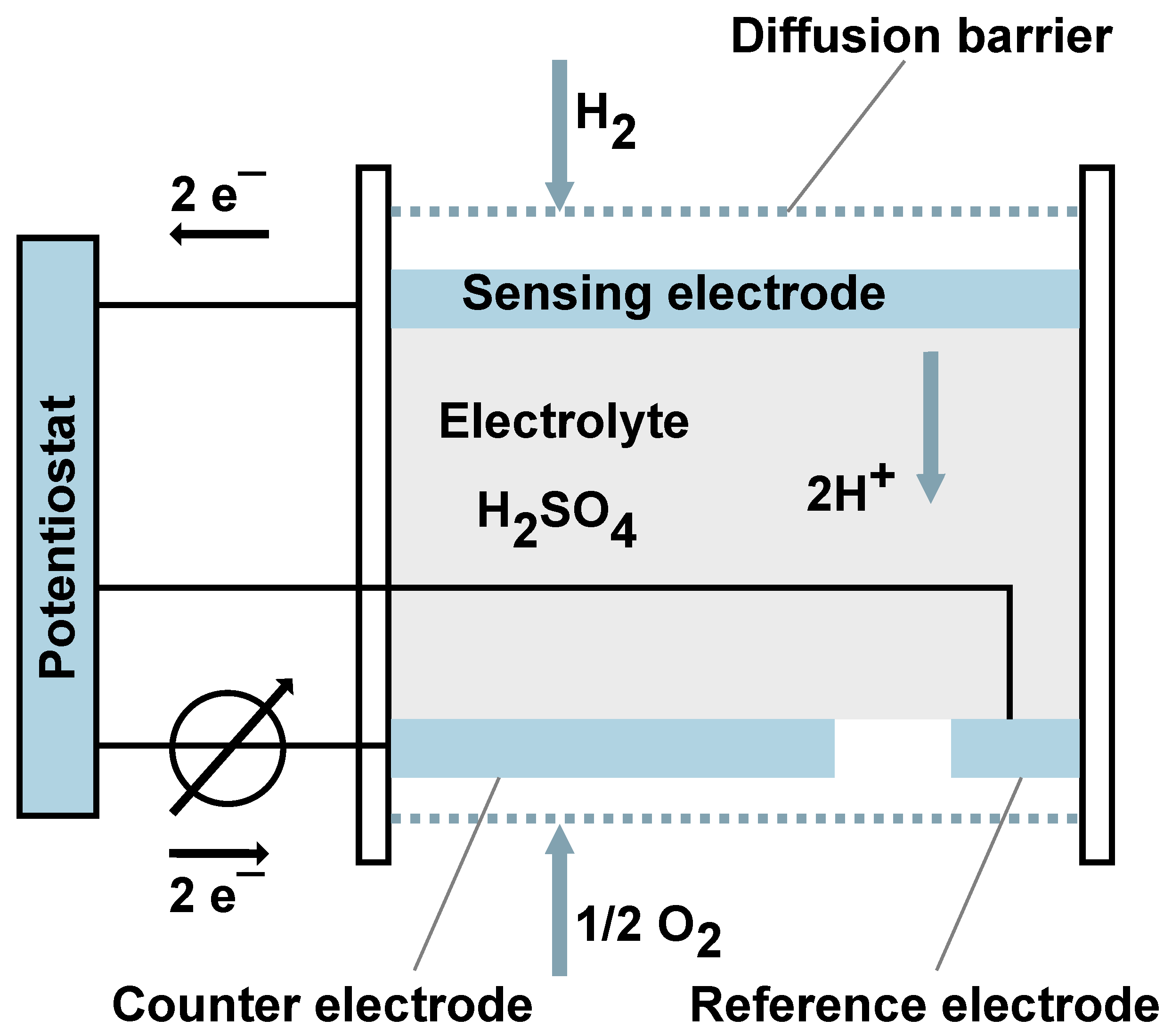

2.3. Measurement of Dissolved Hydrogen

2.4. Determination of Substrate and Digestate Characteristics

2.4.1. Determination of pH

2.4.2. Determination of Total Solids

2.4.3. Determination of Volatile Solids

2.4.4. Determination of Volatile Fatty Acids/Total Inorganic Carbon

| Parameter | Unit | Inoculum | Substrate | Digestate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH- 1 | – | 7.47 | 5.30 | 7.12 |

| TS 2 | wt% | 15.39 | 29.00 | 10.55 |

| VS 3 | wt% TS | 79.43 | 78.53 | 77.35 |

| VFA 4 | m−3 | 3068 | – | 1553–40897 7 |

| TIC 5 | m−3 | 13886 | – | 3881–37475 8 |

| VFA/TIC 6 | – | 0.221 | – | 0.112–5.655 9 |

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FOS | Flüchtige Organische Säuren |

| HRT | Hydraulic retention time |

| OLR | Organic loading rate |

| TAC | Totales Anorganisches Carbonat |

| TS | Total solids |

| TIC | Total inorganic carbon |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| VFA | Volatile fatty acids |

References

- Platošová, D.; Rusín, J.; Platoš, J.; Smutná, K.; Buryjan, R. Case study of anaerobic digestion process stability detected by dissolved hydrogen concentration. Processes 2021, 9, 106. [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, G.; Donoso-Bravo, A.; Jeison, D.; Chamy, R.; Ruíz-Filippi, G.; Wouwer, A.V. A review of the role of hydrogen in past and current modelling approaches to anaerobic digestion processes. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 17713–17722. [CrossRef]

- Strong, G.; Cord-Ruwisch, R. An in situ dissolved-hydrogen probe for monitoring anaerobic digesters under overload conditions. Biotechnology and bioengineering 1995, 45, 63–68. [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, B.; Tommasi, T.; Sanfilippo, S. BioH2 & BioCH4 through anaerobic digestion: from research to full-scale applications; Springer, 2015.

- Batstone, D.J.; Virdis, B. The role of anaerobic digestion in the emerging energy economy. Current opinion in biotechnology 2014, 27, 142–149. [CrossRef]

- Richard, E.N.; Hilonga, A.; Machunda, R.L.; Njau, K.N. A review on strategies to optimize metabolic stages of anaerobic digestion of municipal solid wastes towards enhanced resources recovery. Sustainable Environment Research 2019, 29, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Qiu, Y.; Ren, L.; Jiang, B. Microbial characteristics in anaerobic digestion process of food waste for methane production–A review. Bioresource technology 2018, 248, 29–36. [CrossRef]

- Menzel, T.; Neubauer, P.; Junne, S. Role of microbial hydrolysis in anaerobic digestion. Energies 2020, 13, 5555. [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, S.; Lingam, Y.; Mohan, S.V. Understanding acidogenesis towards green hydrogen and volatile fatty acid production–critical analysis and circular economy perspective. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 464, 141550. [CrossRef]

- Müller, V.; Frerichs, J. Acetogenic bacteria. eLS 2013.

- Bundhoo, M.Z.; Mohee, R. Inhibition of dark fermentative bio-hydrogen production: a review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 6713–6733. [CrossRef]

- Zappi, A.; Hernandez, R.; Holmes, W. A review of hydrogen production from anaerobic digestion. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2021, 18, 4075–4090.

- Cazier, E.A.; Trably, E.; Steyer, J.P.; Escudié, R. Biomass hydrolysis inhibition at high hydrogen partial pressure in solid-state anaerobic digestion. Bioresource technology 2015, 190, 106–113. [CrossRef]

- Anukam, A.; Mohammadi, A.; Naqvi, M.; Granström, K. A review of the chemistry of anaerobic digestion: Methods of accelerating and optimizing process efficiency. Processes 2019, 7, 504. [CrossRef]

- Saady, N.M.C. Homoacetogenesis during hydrogen production by mixed cultures dark fermentation: unresolved challenge. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 13172–13191. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.M.; Wright, M.M. Anaerobic digestion fundamentals, challenges, and technological advances. Physical Sciences Reviews 2023, 8, 2819–2837. [CrossRef]

- Ahring, B.K. Perspectives for anaerobic digestion. Biomethanation i 2003, pp. 1–30.

- Meegoda, J.N.; Li, B.; Patel, K.; Wang, L.B. A review of the processes, parameters, and optimization of anaerobic digestion. International journal of environmental research and public health 2018, 15, 2224.

- Laiq Ur Rehman, M.; Iqbal, A.; Chang, C.C.; Li, W.; Ju, M. Anaerobic digestion. Water Environment Research 2019, 91, 1253–1271.

- Harirchi, S.; Wainaina, S.; Sar, T.; Nojoumi, S.A.; Parchami, M.; Parchami, M.; Varjani, S.; Khanal, S.K.; Wong, J.; Awasthi, M.K.; et al. Microbiological insights into anaerobic digestion for biogas, hydrogen or volatile fatty acids (VFAs): a review. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 6521–6557. [CrossRef]

- Wainaina, S.; Lukitawesa.; Kumar Awasthi, M.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Bioengineering of anaerobic digestion for volatile fatty acids, hydrogen or methane production: a critical review. Bioengineered 2019, 10, 437–458. [CrossRef]

- Huck, C.; Poghossian, A.; Wagner, P.; Schöning, M.J. Combined amperometric/field-effect sensor for the detection of dissolved hydrogen. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2013, 187, 168–173. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Compton, R.G. Amperometric gas detection: A review. International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2014, 9, 7152–7181.

- Hübert, T.; Boon-Brett, L.; Black, G.; Banach, U. Hydrogen sensors–a review. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2011, 157, 329–352.

- Chang, S.; Stetter, J.; Cha, C. Amperometric gas sensors. Talanta 1993, 40, 461–477.

- Dobrovol’skii, Y.A.; Leonova, L.; Ukshe, A.; Levchenko, A.; Baranov, A.; Vasil’ev, A. Portable sensors for hydrogen analysis. Russian Journal of General Chemistry 2007, 77, 797–806.

- Kriksunov, L.B.; Macdonald, D.D. Amperometric hydrogen sensor for high-temperature water. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 1996, 32, 57–60. [CrossRef]

- Fuksa, P.; Hakl, J.; Míchal, P.; Hrevušová, Z.; Šantrůček, J.; Tlustoš, P. Effect of silage maize plant density and plant parts on biogas production and composition. Biomass and Bioenergy 2020, 142, 105770. [CrossRef]

- 2012, E.. Sludge, treated biowaste and soil. Determination of pH, 2012.

- 2012, E.. Sludges, Treated Biowaste, Soils and Wastes—Calculation of the Total Solids Content after Determination of the Drying Residue or Water Content, 2012.

- 2012, E.. Sludge, treated biowaste, soil and waste-Determination of loss on ignition, 2012.

- Liu, X.; André, L.; Mercier-Huat, M.; Grosmaître, J.M.; Pauss, A.; Ribeiro, T. Accurate estimation of bicarbonate and acetic acid concentrations with wider ranges in anaerobic media using classical FOS/TAC titration method. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 11843. [CrossRef]

- Raposo, F.; De la Rubia, M.; Fernández-Cegrí, V.; Borja, R. Anaerobic digestion of solid organic substrates in batch mode: an overview relating to methane yields and experimental procedures. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 2012, 16, 861–877.

- Borja, R.; Rincón, B.; Raposo, F.; Domınguez, J.; Millán, F.; Martın, A. Mesophilic anaerobic digestion in a fluidised-bed reactor of wastewater from the production of protein isolates from chickpea flour. Process Biochemistry 2004, 39, 1913–1921. [CrossRef]

- Cord-Ruwisch, R.; Mercz, T.I.; Hoh, C.Y.; Strong, G.E. Dissolved hydrogen concentration as an on-line control parameter for the automated operation and optimization of anaerobic digesters. Biotechnology and bioengineering 1997, 56, 626–634.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).