1. Introduction

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is a secondary prevention multidisciplinary intervention [

1] recommended by current clinical practice guidelines for the long-term management of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) [

2,

3]. The central component of CR is exercise training, currently recommended as class I level of evidence A intervention for its effectiveness in improving cardiovascular (CV) risk profile and quality of life (QoL) and reducing hospitalizations [

4], even in the modern era of acute revascularization and statin therapy [

5].

However, in the last years multiple lines of evidence have questioned the real efficacy of the exercise-based CR when compared to optimal medical treatment with no exercise for important primary endpoints such as recurrent CV events, CV and all-cause mortality [

6,

7,

8]. Given the absence of international consensus on exercise prescription for CR [

9], the large heterogeneity of the formulation of training used in clinical trials [

10], and the lack of detailed description in reporting training protocols [

11], no definitive conclusion can be drawn based on the current scientific literature. In fact, underdosed exercise does not lead to improvements in fitness since the imposed demands of the training stimulus must be sufficiently high in order to elicit the desired adaptations [

12]. Hence erroneous prescription could be the primary reason for the poor effectiveness of the exercise-based CR [

13].

Regarding the modality of exercise used in CR, recently there has been growing interest in resistance training (RT), since over the last decade evidence has been accumulating about its benefit for CR [

14]. Muscle strength is in fact a strong predictive factor for CV, cancer and all-cause mortality both in healthy [

15] and in CAD patients [

16] and a recent meta-analysis showed that adding RT to CR leads to greater improvements in physical fitness and muscle strength in CAD patients [

17]. Moreover, RT represents a unique modality of exercise with benefits included but not limited to the CV system [

18], considering also the recently discovered role of the skeletal muscles tissue as endocrine organ [

19].

If the primary aim to include RT in CR is to improve muscle strength, then an appropriate dose of training should be prescribed, with recent evidence now suggesting that high intensity RT should be preferably administered [

20,

21]. Moreover, when compared to low intensity-high volume, high intensity RT has been proved to be more effective in increasing strength while being safe and holding less CV demands [

22]. If high intensity RT promotes greater strength gains and it’s safe to use in clinical setting, the most relevant question practitioners should ask is how to accurately prescribe it. Previously, the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) has been validated as effective and practical method for prescribing and monitoring aerobic exercise in CR [

23] and recently a new RPE scale based on number of repetitions in reserve (RIR) was developed [

24] and subsequently validated in literature as effective training tool for RT [

25]. Compared to percentage of one-repetition maximum (1RM), RPE-based on RIR load assignment has been proved to be effective, if not more, in increasing muscle strength and hypertrophy [

26,

27]. This subjective method of prescription can be particularly useful for autoregulation and individualization purposes [

28], both important training factors to consider especially in clinical settings with frail patients, and it has never been studied in CR.

Therefore, the purposes of this study were (a) to assess the efficacy in terms of strength adaptations of the RPE-based on RIR for the prescription of RT in CAD patients and (b) to compare it to the percentage of 1RM-based prescription. We hypothesized that the novel RPE scale would be an effective method for prescribing RT in CR and that it would provide similar strength gains compared to the consolidated practice of percentage-based prescription.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population

A total of twenty-one male patients with history of CAD were recruited between October 2022 and June 2023 at the San Raffaele IRCCS rehabilitation facility in Rome. After the recruitment, two patients developed contraindications to exercise training and three were excluded due to non-adherence to the RPs, therefore only sixteen patients completed the RPs (eight per group). Inclusion criteria for the patients were history of CAD, clinical stability with no hospital admissions for heart failure (HF) in the previous six months or modifications to pharmacological therapy in the previous three months, and New York Heart Association (NYAH) functional class I or II. Patients would be excluded if they had unstable angina, uncontrolled hypertension or arrhythmias, exercise test positive for myocardial ischemia or complex arrhythmias, symptomatic valvular or peripheral arterial disease, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, neurologic or orthopedic conditions contraindicating or limiting exercise training.

2.2. Study Design

The study was conducted as a prospective longitudinal randomized trial. Patients were randomly assigned to two RT rehabilitation protocols (RPs) with the same exercise selection, sets, repetitions, and rest periods, but different load prescription method: one group using RPE-based on RIR (RPE group) and the other using percentage of 1RM (%1RM group). A randomization code was developed by a random-number generator software to ensure the randomness of the assignment. The RPs lasted nine weeks with three training sessions per week following a linear periodization model, with exercises involving the major muscle group of the upper and the lower body. Detailed description of the RPs according to the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT) [

29] are illustrated in the Rehabilitation Protocol dedicated section. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local Ethics Committee of IRCCS San Raffaele Roma (protocol number 13/2022). All patients gave written informed consent before entering the study.

2.3. Cardiologic Evaluation

Prior the administration of the RPs, all patients underwent a full clinical evaluation consisting of complete medical history, cardiac and chest physical examination, anthropometric measurements, transthoracic echocardiogram (Vivid E95, GE Healthcare, Chicago, Illinois, USA), and maximal exercise test performed on a cycle ergometer (Mortara Instrument, Casalecchio Di Reno, Italy) with a 20x2 incremental protocol (20 Watt increases every 2 minutes). Patients were required to exercise at a speed of 65 revolution per minute (RPM) and the test was terminated when RPM could not be maintained despite increasing effort.

2.4. Strength Testing

Patients’ strength was evaluated by a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist using six repetitions maximum (6RM) tests on all the exercises of the RP according to validated procedures [

30]. This type of test was chosen because it closely matches the repetition scheme used in the RPs (see more in the dedicated section), hence could accurately detect strength changes in this repetition range.

In preparation for the test, the warm-up consisted of one set of ten repetitions with minimal or no load, followed by sets of six repetitions with low load. Weight was then progressively increased from set to set until reaching momentary failure during the sixth repetition, i.e. the inability to complete the concentric phase of the lift despite maximal effort, and the weight used in the previous set was recorded as the 6RM. Patients were allowed to use the Valsalva Maneuver during the tests.

During the tests, the RPE scale based on RIR was shown to the patients, along with verbal aid on how to determine scores. The scale goes from 1 to 10 based on the subjective determination of RIR prior reaching momentary failure, so that a score of 10 indicates the maximum number of repetitions for a given load could be performed, 9 indicates only one more repetition could be performed, 8 indicates only two more repetitions could be performed, etc. as shown in

Table 1.

The 6RM tests were performed with the Biocircuit Wellness System machines (Technogym, Cesena, Italy) on two separated occasion 72 hours apart to accurately determine patients’ strength by avoiding excessive fatigue of multiple tests and to anchor RPE scores to the perceived fatigue and the maximal effort. The first strength test session consisted of leg press, chest press and seated row, while the second of leg extension, shoulder press and lat pulldown. Based on previously reported relationship between percentage of 1RM and multiple repetitions completed [

25], the 6RM results were used to estimate the 1RMs to then calculate the percentage of load for the RP.

2.5. Rehabilitation Protocol

The RPs consisted of nine weeks of RT exercise, as shown in

Table 2. Both groups trained three times per week on non-consecutive days (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday), using the same exercises, sets, repetitions, and rest periods. The only difference between the two RPs was that in the %1RM group the loads were selected as percentage of the estimated 1RMs (e1RMs) based upon the pre-intervention strength tests, while in the RPE group the patients self-selected the loads to reach the RPE targets. RPE scores of both groups were recorded throughout the RPs.

Weeks 0 and 10 were dedicated to pre- and post-intervention strength tests. The actual RPs took place from weeks 1 to 9, following a linear periodization model in which volume decreases over time while intensity increases. Each session consisted of the following exercised in this specific order: leg press, chest press, seated row, leg extension, shoulder press, and lat pulldown. The exercises were performed on the same machines used for the tests (Biocircuit Wellness System, Technogym, Cesena, Italy).

Weeks 1 to 3 were used as introductive weeks for the RPE-group, whereby the physiotherapists assigned the loads to the patients to ensure the correct RPE targets would be reached. Doing so allowed the patients to have time to practice with the RPE scale, as previous research showed that RPE accuracy could take up to three weeks [

31].

After this familiarization period, starting from week 4 patients in the RPE group self-selected all the loads. Specifically, the patients were required to perform the prescribed sets and repetitions with a load that would correspond to the assigned RPE range, meanwhile the therapists would cue them showing the RPE scale based on RIR and the records of previous performance to aid the load selection. If the RPE score would fall outside of the target ranges, adjustments in load were made for the following sets [

32]. Specifically, for every 1 RPE score above or below the target range, loads were decreased or increased by 4% to bring the RPE of subsequent sets closer to the prescribed range as shown in

Table 3.

If repetitions were missed due to excessive load, the set was considered a 10 RPE and the load was decreased by an additional 4% for every missed repetition as shown in

Table 4. Within a week, patients had three sessions with the same prescription (sets, repetitions, intensity) to gauge the RPEs correctly to the assigned repetitions. The repetition schemes (sets, repetitions) were the same for three consecutive weeks, as the intensity increased from one week to the other, so patients could learn how to increase and estimate the effort at a given repetition range. Every fourth week the intensity remained constant and repetition schemes changed, so that patients could adapt to the new repetition ranges at the same intensity. Relative intensities in both groups were assign based on previously found relationship between loads, repetitions and RPEs [

25], as shown in Supplemental

Table 1, so that the percentages of 1RMs in the %1RM group would correspond on average to the RPE ranges of the RPE group.

Rest periods were one minute for sets at RPE between 5-7, one minute and a half for sets at RPE between 6-8, and two minutes for sets at RPE between 7-9. As for the strength tests, patients were allowed to use the Valsalva Maneuver, and they were required to complete at least two sessions per week otherwise they would be excluded from the RPs.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS statistical software package (version 20.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA). Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were compared with T-Test, paired for the within group analysis and unpaired for the between groups analysis. The assumption of normality was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk hypothesis test. Categorical variables are expressed as absolute and percentages values and were compared with Chi-square Test. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Sample size was determined by feasibility and patients’ availability, hence no formal a priori power analysis was performed [

33]. Pre- and post-intervention variables with normal distribution were assessed using analysis of covariance (ANOVA), specifically two-way repeated measures ANOVA considering time and load prescription method as predictive variables of strength. Within group Cohen’s d effect size (ES) were calculated using the pooled pre- and post-intervention SD and 0.65 and 0.73 were identify as smallest effect size of interest (SESOI) for the lower and upper body strength respectively, based on Yamamoto et al. meta-analysis [

34]. Between groups ES were calculated as the difference between groups’ mean change scores divided by the pooled SD of both groups’ change scores, as this is the appropriate method to compare results between two groups [

35]. Based on the scale for determining the magnitude of ES in strength training research proposed by Rhea et al. [

36], 0.5 was set as SESOI for the between groups comparison.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Patients baseline anthropometric and clinical characteristic, along with echocardiographic parameters are summarized in

Table 5. Overall, both groups had similar baseline characteristics and no statistically significant differences were found except for basal heart rate, previous smoking habit, use of antiarrhythmics and stroke volume.

3.2. Adherence and Adverse Effects Baseline Characteristics

Adherence to RPs was high with a mean of 24 completed sessions out of 27 (88%), with no statistically significant differences between the two groups (RPE group 88 ± 3% vs %1RM group 89 ± 4%, p = 0.213). Furthermore, for the entire duration of the RPs there were no cardiac alarm symptoms, i.e. shortness of breath, palpitation, chest pain, dizziness, or syncope, and no adverse CV events, such as exercise induced malignant arrhythmias or cardiac ischemia.

3.3. Strength

Table 6 shows groups’ pre-intervention 6RM strength test results for each exercise of the RPs. Baseline strength levels were similar between the two groups, with no statistically significant differences for any of the exercises. At the end of the RPs, statistically significant increments in strength were recorded in both groups compared to baseline results, except for the shoulder press in the %1RM group with an increment approaching the level of significance (p = 0.053), as shown in

Table 7. Within group analysis showed ES greater than the SESOI on all the exercises for the RPE group, with relative percentage change between 19.1% and 24.7% (for the lat pulldown and the seated row respectively), while for the %1RM group the ES for chest press, shoulder press and lat pulldown were below the SESOI.

Table 6 shows groups’ post-intervention 6RM strength test results for each exercise of the RPs. Overall, no statistically significant differences between the two groups were recorded. Between group analysis demonstrated no advantages for one prescription method over the other, with ES below the SESOI. Patients individual change scores are shown in Supplementary Table

S2.

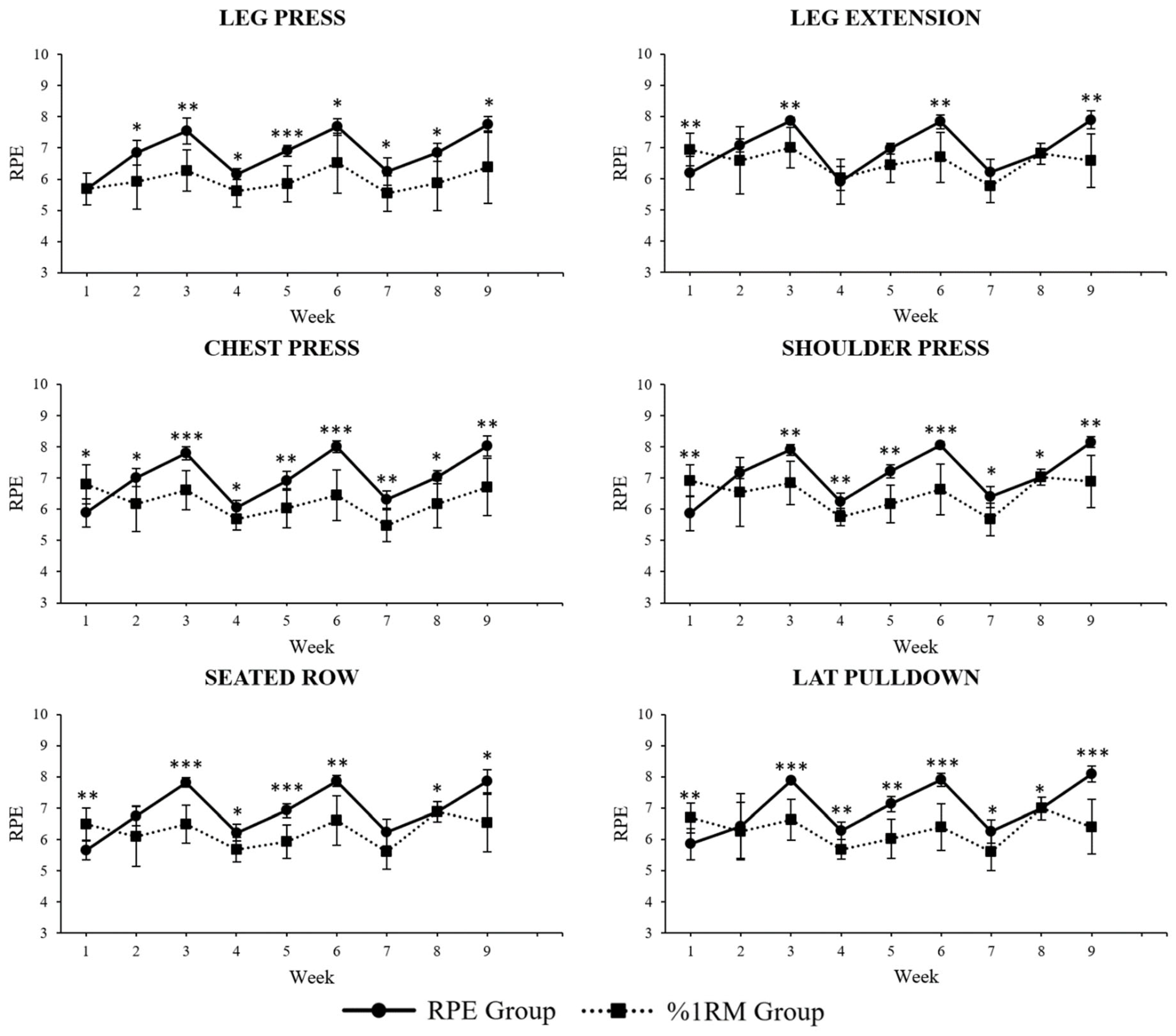

3.4. RPE and Relative Intensity

Figure 1 shows weekly average RPE trends of all the exercises of the RPs for both groups throughout the study. Specifically, for the leg press the average RPE was significantly higher in the RPE group from week 2 to 9; for the chest press it was significantly higher in the %1RM group in week 1, and then significantly higher in the RPE group from week 2 to 9; for the seated row it was significantly higher in the %1RM group in week 1, and then significantly higher in the RPE group from week 3 to 6 and in week 8 and 9; for the leg extension it was significantly lower in the %1RM group in week 1, and significantly higher in the RPE group in week 3, 6 and 9; for the shoulder press it was significantly higher in the %1RM group in week 1 and then significantly higher in the RPE group from week 3 to 9; for the lat pulldown it was significantly higher in the %1RM group in week 1 and then significantly higher in the RPE group from week 3 to 9.

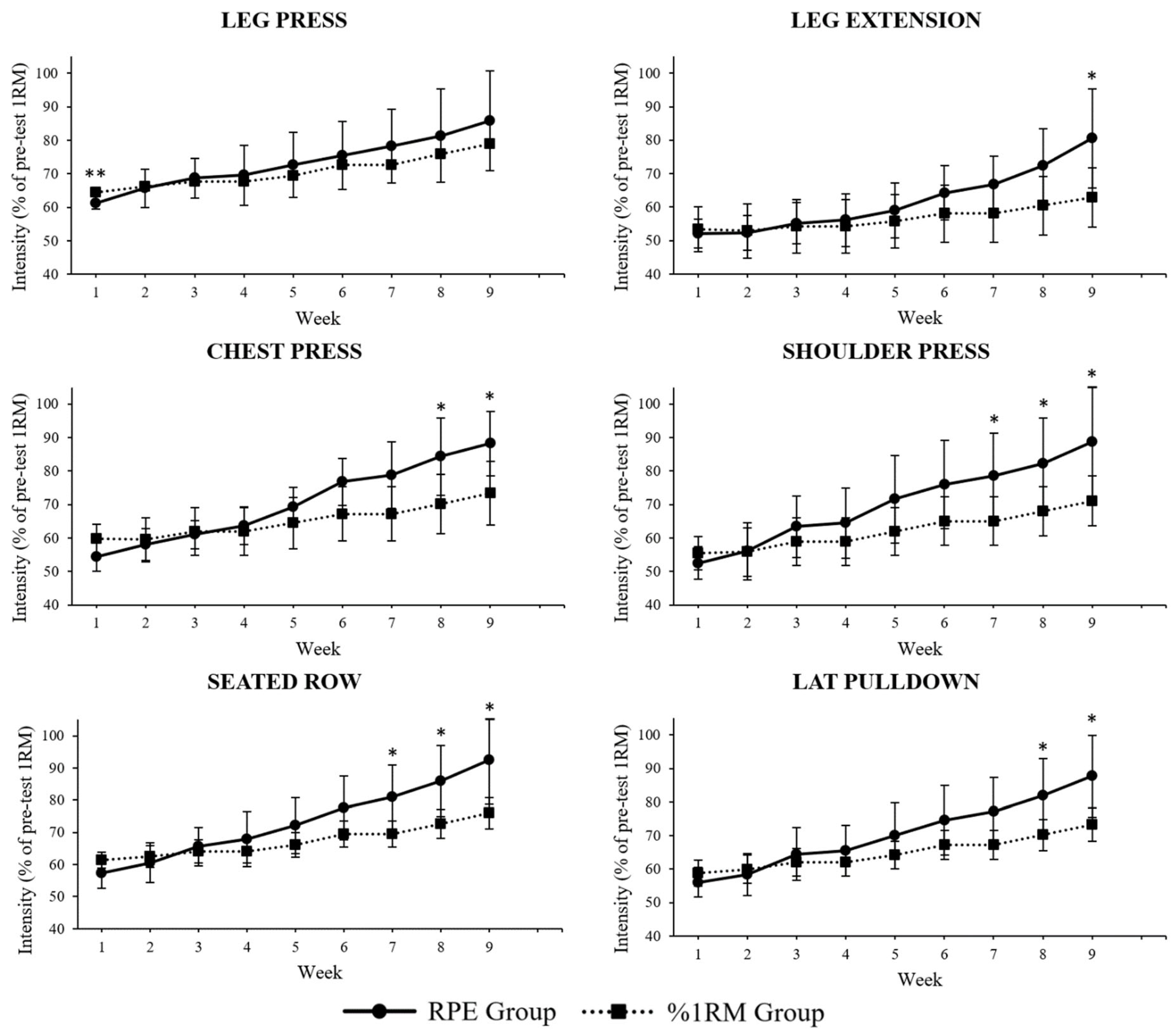

Figure 2 shows weekly average relative intensity trends of all the exercises of the RPs for both groups throughout the study. Relative intensity was defined as the load used in training divided by pre-intervention e1RMs. Specifically, for the leg press the average relative intensity was significantly higher in the %1RM group in week 1; for the chest press was significantly higher in the RPE group in week 8 and 9; for the seated row was significantly higher in the RPE group from week 7 to 9; for the leg extension it was significantly higher in the RPE group in week 9; for the shoulder press it was significantly higher in the RPE group from week 7 to 9; for the lat pulldown it was significantly higher in the RPE group in week 8 and 9.

Table 6 shows groups’ pre-intervention 6RM strength test results for each exercise of the RPs. Baseline strength levels were similar between the two groups, with no statistically significant differences for any of the exercises.

4. Discussion

The purposes of this study were to assess the efficacy of the RPE-based on RIR as prescription method for RT in CAD patients undergoing CR and to compare it to the standardized practice of percentage of 1RM. In line with our hypothesis, the recently developed RPE scale based on RIR proved to be an effective and practical tool for the prescription of RT intensity in CR settings. The RPE group showed in fact statistically significant increases in strength across all the administered exercises of the RP, with relative percentage changes between 19.1% and 24.7%, and relevant ES compared to pre-intervention strength tests. Furthermore, RPE-based on RIR demonstrated similar efficacy in terms of strength gains compared to percentage of 1RM prescription method, with post-intervention strength tests showing no statistically significant differences and trivial ES for all the exercises of the RPs between the two groups.

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the RPE-based on RIR in clinical settings and outside the strength and conditioning research field [

37]. The rationale to include RPE in training derives from the intrinsic variability of physical performance, which is subject to variations due to factors such as nutrition, sleep, and stressors, among others [

38]. Daily fluctuations in performance can be observed especially in subjects with chronic conditions under multiple pharmacological treatments, such as CAD patients. These fluctuations can occur during the initial strength tests, thereby affecting the results and consequently the training plan.

Moreover, even if the initial tests accurately reflect individual’s strength levels, they will not account for the progress or the rate at which they occur [

39]. This can be observed in the relative intensity differences between the two groups towards the end of RPs, with statistically significant differences in week 7 to 9 for the shoulder press and the seated row, in week 8 and 9 for the chest press and the lat pulldown, and in week 8 for the leg extension. Patients in the RPE group likely trained at higher intensities during the last weeks because they weren’t limited by the pre-planned loads based on the initial strength tests, as they were allowed to increase the training intensity based on their current performance, while patients in the %1RM group may have trained with percentages not representative of their actual strength.

The higher relative intensities and RPE scores in the RPE group could also explain why this group saw statistically significant increases and relevant ES on all the exercise, meanwhile the %1RM group saw no statistically significant increments in the shoulder press and only trivial ES for the chest press, shoulder press, and lat pulldown, despite no differences in training load (defines as sets x reps x load) were identified for the entire duration of the study. These results are in line with the current literature showing that RT programs with high loads are superior in inducing muscle strength gains when compared to low loads [

40,

41]. Also, despite the common practice of calculating the number of repetitions allowed at given percentage of 1RM from textbook tables [

30], these charts have recently been questioned [

42] since there is high inter-individual variation in the number of repetitions that can be performed at the given percentage [

43]. Therefore, considering all the variables affecting strength in clinical settings, prescribing RT intensity with RPE-based on RIR could be more accurate than percentages in these scenarios, especially if, like the RP proposed in this study, multiple sets with low number of repetitions and close to muscle failure are used, since previous research demonstrated that these factors can improve the accuracy of the RIR prediction [

44]. Moreover, the two methods are not mutually exclusive and could be used in adjunctions for a more individualized prescription.

Since percentage-based loading can set unrealistic expectations for practitioners and patients alike, autoregulation can be implemented to overcome these limitations. Defined as the process of adjusting the training program over time based on individual’s current performance [

45], autoregulation proved to be as effective as standardized percentage-base loading for strength improvements in a recent meta-analysis [

28], and this study is the first exploring its applicability in clinical settings.

The present has several limitations. Firstly, due to the limited availability of patients meeting the inclusion criteria during the time of recruitment, our analysis was limited to a small sample size, hence larger clinical trials are necessary to confirm the current findings. Secondly, due to the high prevalence of CAD males subjects in cardiac rehabilitation facilities, the analyzed sample includes only men, therefore it is not possible to extend the results of the current study to female subjects as well. Regarding the RPs, the percentages and the respective RPEs used for loads prescription are derived from e1RMs and not actual measured 1RMs, since 1RM testing would have been impractical in patients uncustomed to RT. Moreover, the relationship between loads, repetitions and RPEs, used to develop the RPs and to ensure the patients would train at the same intensities, is based on a single study conducted on healthy young subjects performing the barbell back squat [

25]. Thus, it is possible the same relationship does not subsist in CAD patients performing different exercises. Uncontrolled diet represents another variable that needs to be considered, since calories and protein intakes are major contributors of skeletal muscle hypertrophy, which is closely related to muscle strength. Lastly, QoL assessments and measurements of cardiorespiratory fitness were not conducted to focus the analysis on the training variables and the individual results.

5. Conclusion

In this study the novel RPE scale based on RIR proved to be an effective method for the prescription of RT exercise in CR of CAD patients, showing similar efficacy to the standardized practice of percentages of 1RM-based training. Further research is needed to confirm and extend the results of the present study.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This work was supported by funding of the Italian Ministry of Health [Ricerca corrente].

Authors’ Contributions

AG, GC developed the design of the study. AG, EG, VD, DDB, SV, AF, AM, and CG contributed to the data collection. Data analysis was performed by AG, GC, and FI, as well as the interpretation of the results. MV and BS contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Dec-laration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of San Raffaele IRCCS of Rome (protocol code 13/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been also obtained from the patients to publish this paper

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ambrosetti M, Abreu A, Corrà U, et al. Secondary prevention through comprehensive cardiovascular rehabilitation: From knowledge to implementation. 2020 update. A position paper from the Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. Published online 2021. [CrossRef]

- Neumann FJ, Sechtem U, Banning AP, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. Published online 2020. [CrossRef]

- Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. Published online 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dibben G, Faulkner J, Oldridge N, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online 2021. [CrossRef]

- Salzwedel A, Jensen K, Rauch B, et al. Effectiveness of comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation in coronary artery disease patients treated according to contemporary evidence based medicine: Update of the Cardiac Rehabilitation Outcome Study (CROS-II). Eur J Prev Cardiol. Published online 2020. [CrossRef]

- West RR, Jones DA, Henderson AH. Rehabilitation after myocardial infarction trial (RAMIT): Multi-centre randomised controlled trial of comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation in patients following acute myocardial infarction. Heart. Published online 2012. [CrossRef]

- Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, et al. Exercise-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation for Coronary Heart Disease Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. Published online 2016. [CrossRef]

- Powell R, McGregor G, Ennis S, Kimani PK, Underwood M. Is exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation effective? A systematic review and meta-Analysis to re-examine the evidence. BMJ Open. Published online 2018. [CrossRef]

- Price KJ, Gordon BA, Bird SR, Benson AC. A review of guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation exercise programmes: Is there an international consensus? Eur J Prev Cardiol. Published online 2016. [CrossRef]

- Fidalgo ASF, Farinatti P, Borges JP, de Paula T, Monteiro W. Institutional Guidelines for Resistance Exercise Training in Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review. Sport Med. Published online 2019. [CrossRef]

- Hansford HJ, Wewege MA, Cashin AG, et al. If exercise is medicine, why don’t we know the dose? An overview of systematic reviews assessing reporting quality of exercise interventions in health and disease. Br J Sports Med. Published online 2022:bjsports-2021-104977. [CrossRef]

- Santiago de Araújo Pio C, Marzolini S, Pakosh M, Grace SL. Effect of Cardiac Rehabilitation Dose on Mortality and Morbidity: A Systematic Review and Meta-regression Analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. Published online 2017. [CrossRef]

- Khushhal A, Nichols S, Carroll S, Abt G, Ingle L. Characterising the application of the “progressive overload” principle of exercise training within cardiac rehabilitation: A United Kingdom-based community programme. PLoS One. Published online 2020. [CrossRef]

- Giuliano C, Karahalios A, Neil C, Allen J, Levinger I. The effects of resistance training on muscle strength, quality of life and aerobic capacity in patients with chronic heart failure — A meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. Published online 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz JR, Sui X, Lobelo F, et al. Association between muscular strength and mortality in men: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. Published online 2008. [CrossRef]

- Kamiya K, Masuda T, Tanaka S, et al. Quadriceps Strength as a Predictor of Mortality in Coronary Artery Disease. Am J Med. Published online 2015. [CrossRef]

- Hollings M, Mavros Y, Freeston J, Fiatarone Singh M. The effect of progressive resistance training on aerobic fitness and strength in adults with coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Prev Cardiol. Published online 2017. [CrossRef]

- Maestroni L, Read P, Bishop C, et al. The Benefits of Strength Training on Musculoskeletal System Health: Practical Applications for Interdisciplinary Care. Sport Med. Published online 2020. [CrossRef]

- Severinsen MCK, Pedersen BK. Muscle–Organ Crosstalk: The Emerging Roles of Myokines. Endocr Rev. Published online 2020. [CrossRef]

- Raymond MJ, Bramley-Tzerefos RE, Jeffs KJ, Winter A, Holland AE. Systematic review of high-intensity progressive resistance strength training of the lower limb compared with other intensities of strength training in older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Published online 2013. [CrossRef]

- Borde R, Hortobágyi T, Granacher U. Dose–Response Relationships of Resistance Training in Healthy Old Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sport Med. Published online 2015. [CrossRef]

- Hansen D, Abreu A, Doherty P, Völler H. Dynamic strength training intensity in cardiovascular rehabilitation: is it time to reconsider clinical practice? A systematic review. Eur J Prev Cardiol. Published online 2019. [CrossRef]

- Iellamo F, Manzi V, Caminiti G, et al. Validation of rate of perceived exertion-based exercise training in patients with heart failure: Insights from autonomic nervous system adaptations. Int J Cardiol. Published online 2014. [CrossRef]

- Tuchscherer M. The Reactive Training Manual: Developing Your Own Custom Training Program for Powerlifting.; 2008.

- Zourdos MC, Klemp A, Dolan C, et al. Novel Resistance Training-Specific Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale Measuring Repetitions in Reserve. J Strength Cond Res. Published online 2016. [CrossRef]

- Helms ER, Byrnes RK, Cooke DM, et al. RPE vs. Percentage 1RM loading in periodized programs matched for sets and repetitions. Front Physiol. Published online 2018. [CrossRef]

- Graham T, Cleather DJ. Autoregulation by “Repetitions in Reserve” Leads to Greater Improvements in Strength Over a 12-Week Training Program Than Fixed Loading. J Strength Cond Res. Published online 2019. [CrossRef]

- Hickmott LM, Chilibeck PD, Shaw KA, Butcher SJ. The Effect of Load and Volume Autoregulation on Muscular Strength and Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sport Med - Open. 2022;8(1). [CrossRef]

- Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT): Explanation and Elaboration Statement. Br J Sports Med. Published online 2016. [CrossRef]

- Haff GG, Triplett NT, eds. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. 4th ed. Human Kinetics; 2015.

- Helms ER, Brown SR, Cross MR, Storey A, Cronin J, Zourdos MC. Self-rated accuracy of rating of perceived exertion-based load prescription in powerlifters. J Strength Cond Res. Published online 2017. [CrossRef]

- Helms ER, Cross MR, Brown SR, Storey A, Cronin J, Zourdos MC. Rating of perceived exertion as a method of volume autoregulation within a periodized program. J Strength Cond Res. Published online 2018. [CrossRef]

- Lakens D. Sample Size Justification. Collabra Psychol. Published online 2022. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto S, Hotta K, Ota E, Mori R, Matsunaga A. Effects of resistance training on muscle strength, exercise capacity, and mobility in middle-aged and elderly patients with coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. J Cardiol. Published online 2016. [CrossRef]

- Dankel SJ, Mouser JG, Mattocks KT, et al. The widespread misuse of effect sizes. J Sci Med Sport. Published online 2017. [CrossRef]

- Rhea MR. Determining the magnitude of treatment effects in strength training research through the use of the effect size. J Strength Cond Res. Published online 2004. [CrossRef]

- Fairman CM, Zourdos MC, Helms ER, Focht BC. A Scientific Rationale to Improve Resistance Training Prescription in Exercise Oncology. Sport Med. Published online 2017. [CrossRef]

- Helms ER, Cronin J, Storey A, Zourdos MC. Application of the Repetitions in Reserve-Based Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale for Resistance Training. Strength Cond J. Published online 2016. [CrossRef]

- Timmons JA. Variability in training-induced skeletal muscle adaptation. J Appl Physiol. Published online 2011. [CrossRef]

- Lopez P, Radaelli R, Taaffe DR, et al. Resistance Training Load Effects on Muscle Hypertrophy and Strength Gain: Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Published online 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lacio M, Vieira JG, Trybulski R, et al. Effects of resistance training performed with different loads in untrained and trained male adult individuals on maximal strength and muscle hypertrophy: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Published online 2021. [CrossRef]

- Nuzzo JL, Pinto MD, Nosaka K, Steele J. Maximal Number of Repetitions at Percentages of the One Repetition Maximum: A Meta-Regression and Moderator Analysis of Sex, Age, Training Status, and Exercise. Sport Med. 2023;(Table 1). [CrossRef]

- Richens B, Cleather DJ. The relationship between the number of repetitions performed at given intensities is different in endurance and strength trained athletes. Biol Sport. Published online 2014. [CrossRef]

- Halperin I, Malleron T, Har-Nir I, et al. Accuracy in Predicting Repetitions to Task Failure in Resistance Exercise: A Scoping Review and Exploratory Meta-analysis. Sport Med. Published online 2022. [CrossRef]

- Greig L, Stephens Hemingway BH, Aspe RR, Coop\er K, Comfort P, Swinton PA. Autoregulation in Resistance Training: Addressing the Inconsistencies. Sport Med. Published online 2020. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).