Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

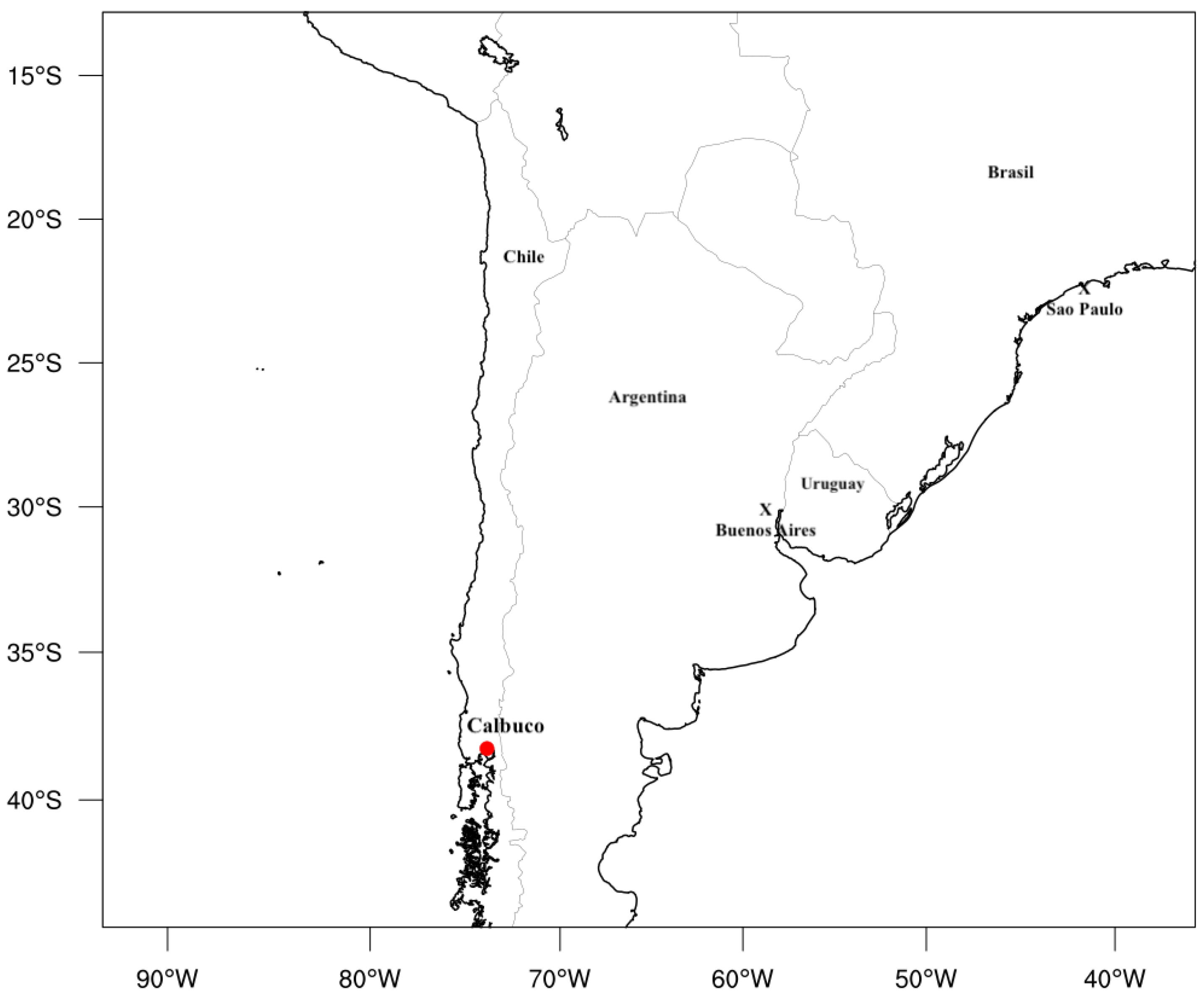

2.1. Description of the Event

| Start Time | Durantion | emiss height | emiss ash rate | emiss SO2 |

| UTC | min | km | kg s-1 | kg h-1 |

| 22/04/2015 - 21:00 | 90 | 16 | ||

| 23/04/2015 - 04:00 | 360 | 17 |

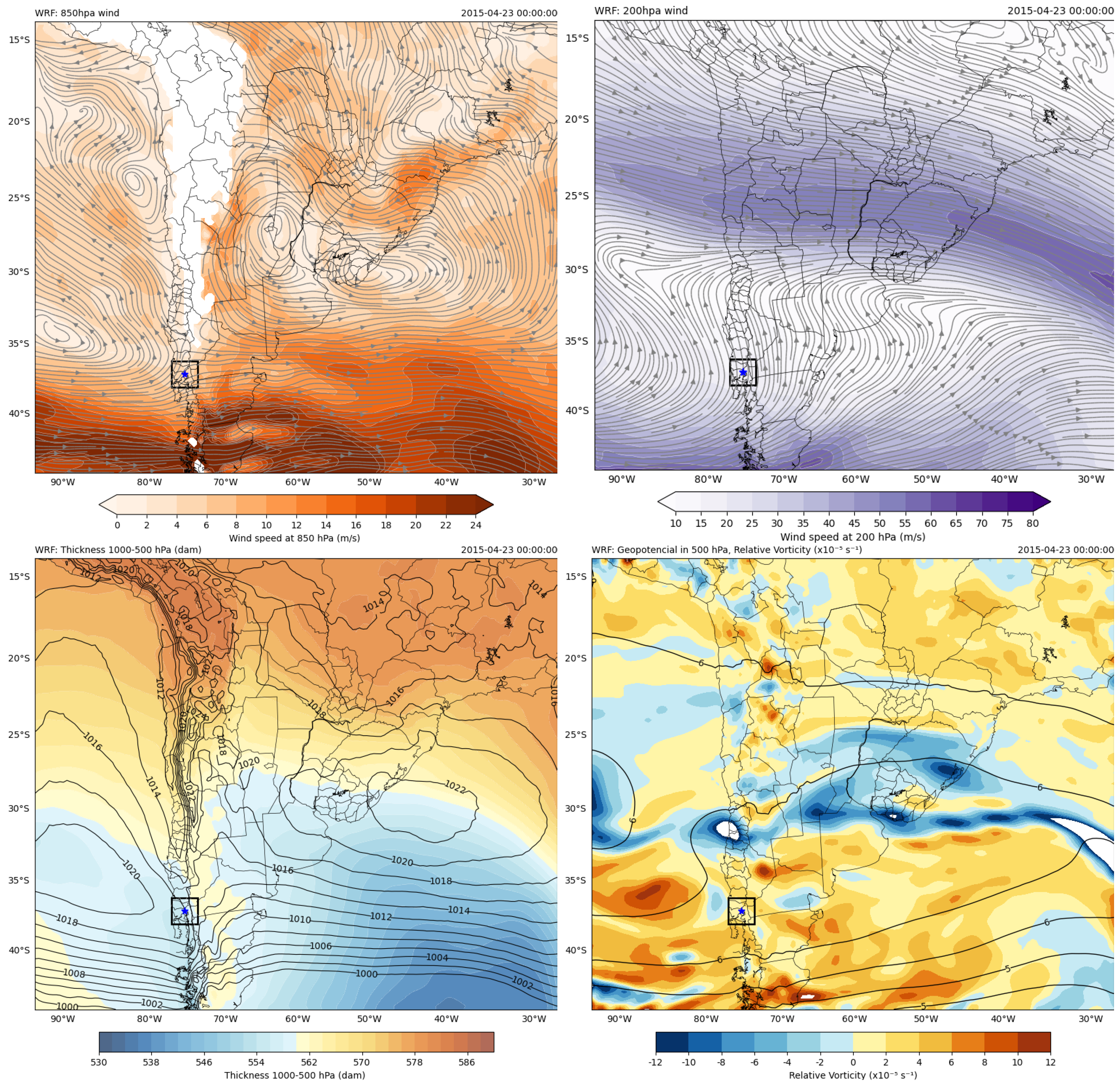

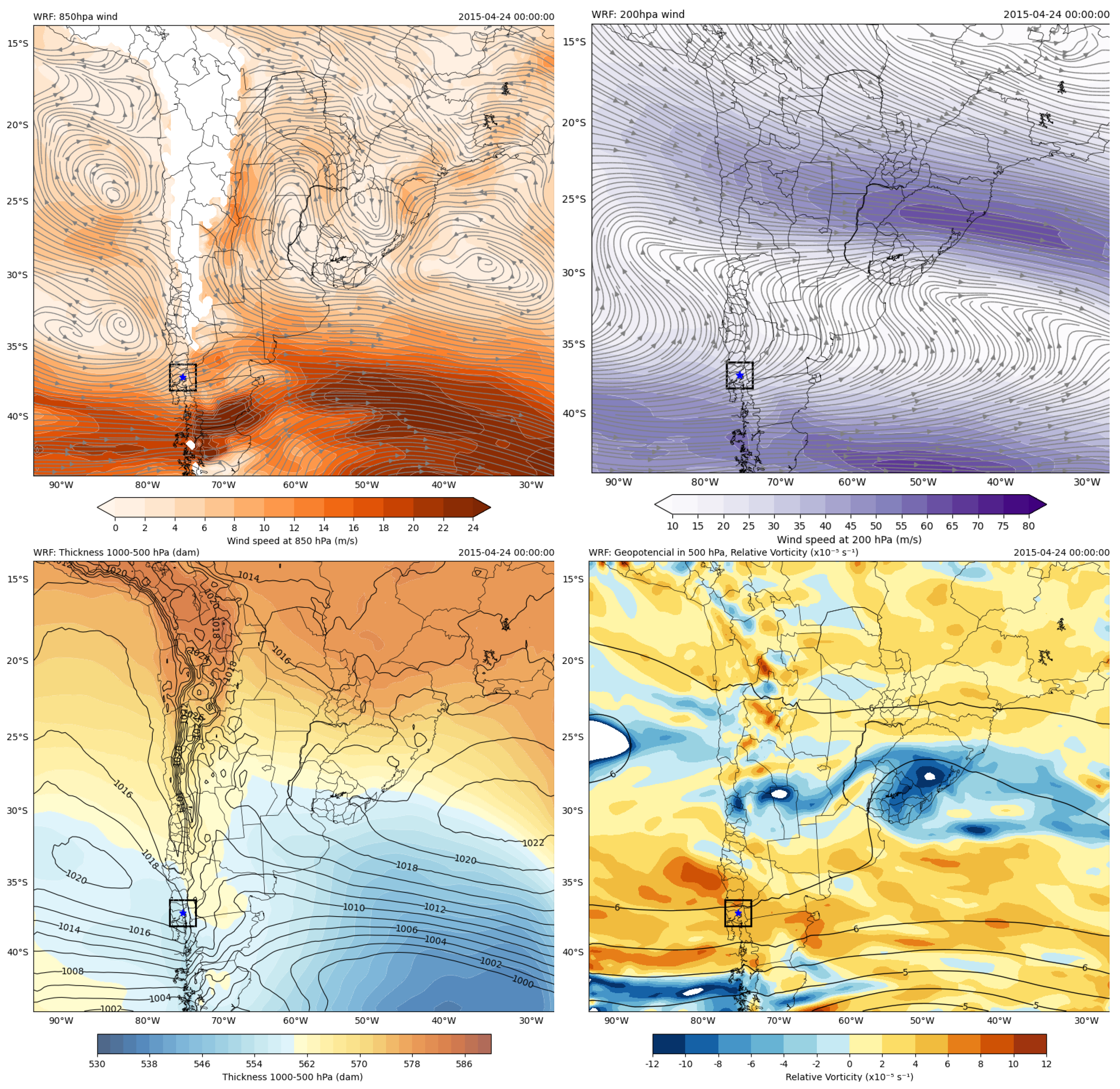

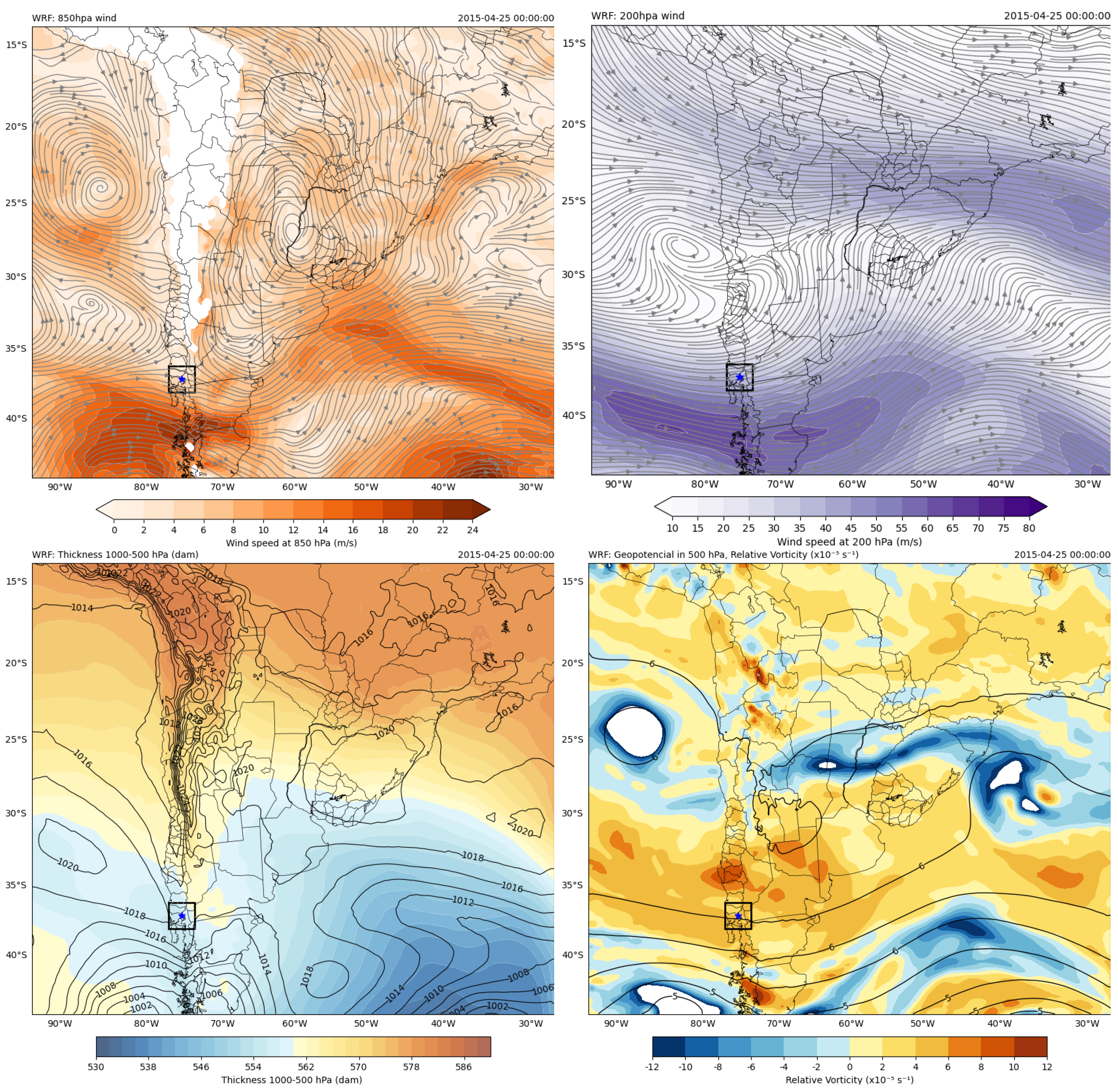

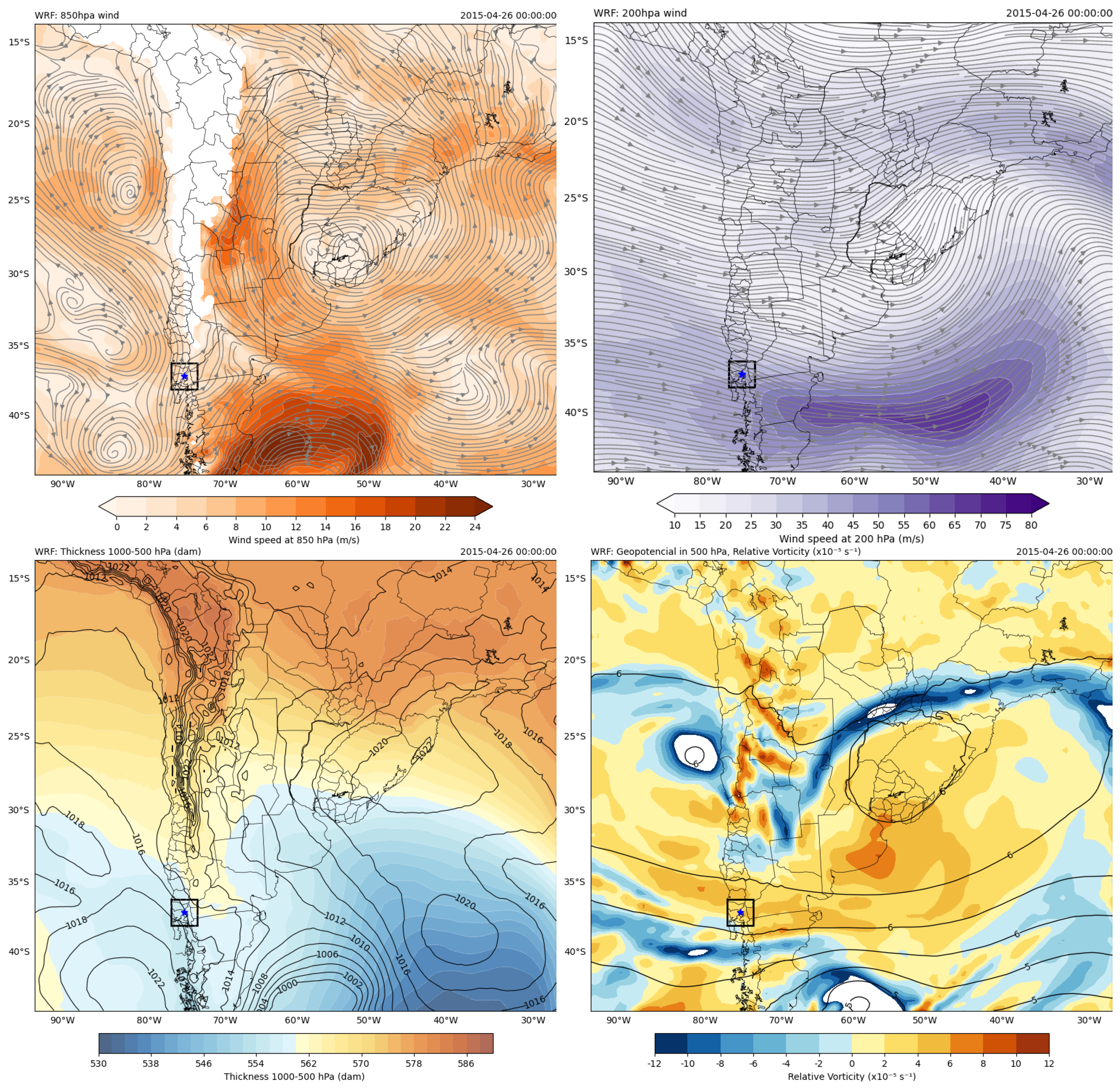

2.2. Synoptic Analysis During the Event

2.3. Orography Influence

2.4. WRF-Chem Model: Setup for Volcanic Emissions

| case | chem_opt | distribution | vash_ # | % total mass |

| GCTS2 | 300 | S2 | 8-10 | 16.5 |

| GCTS1 | 300 | S1 | 8-10 | 2.4 |

2.5. Description of the Event by AOD from AERDB OMPS-SNPP

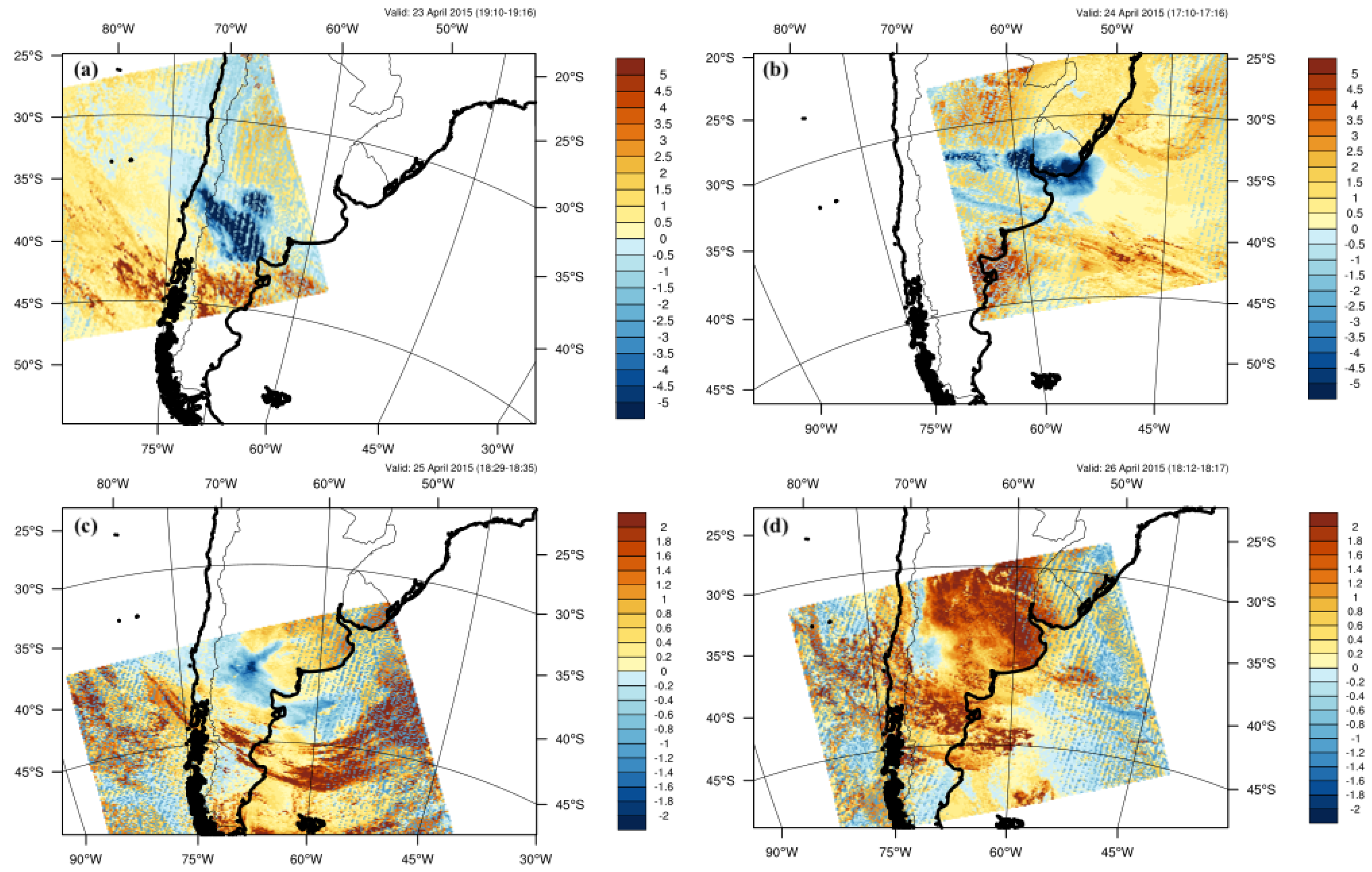

2.6. Description of the Event by the Split Windows Imagery by VIIRS

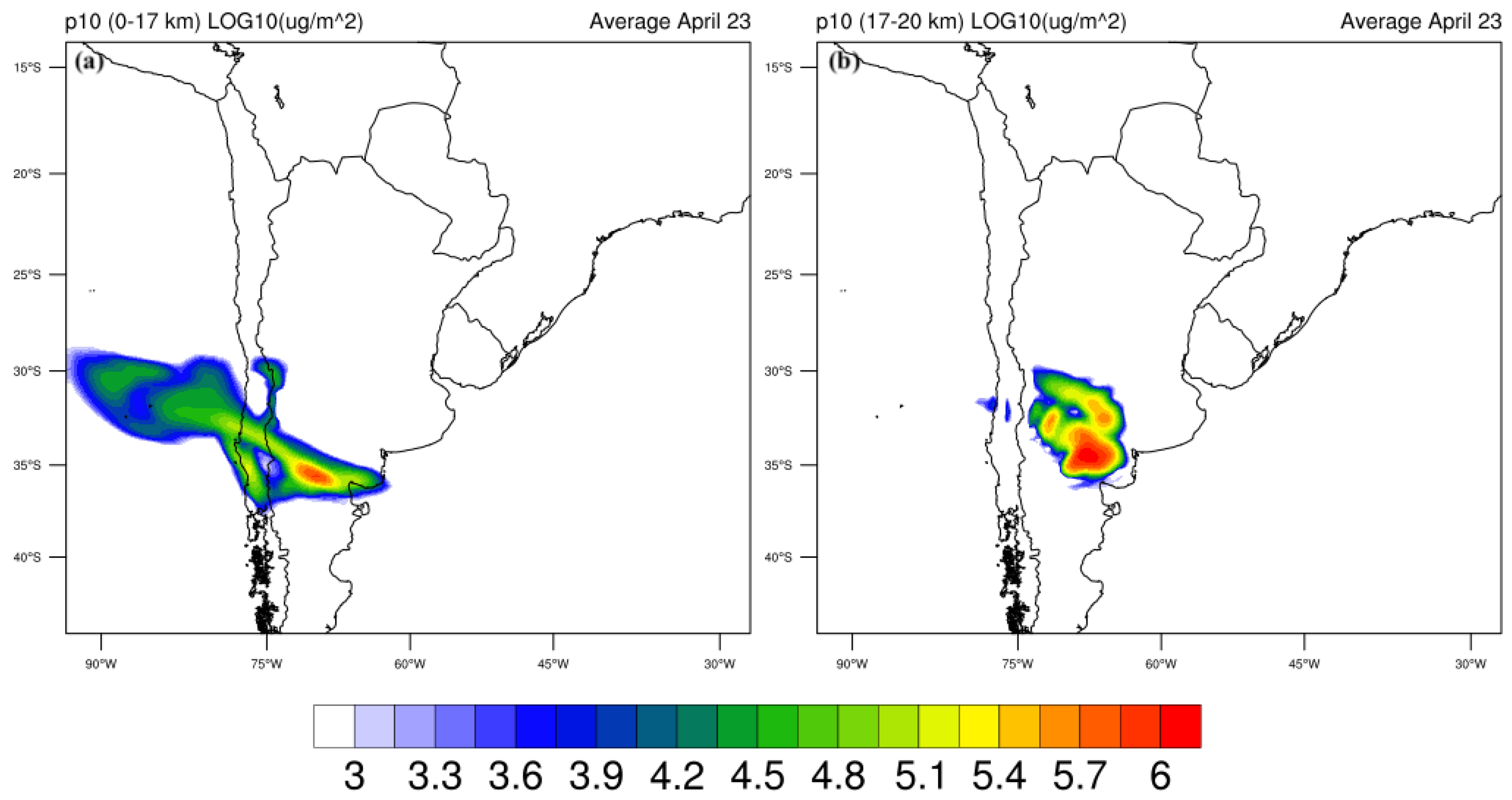

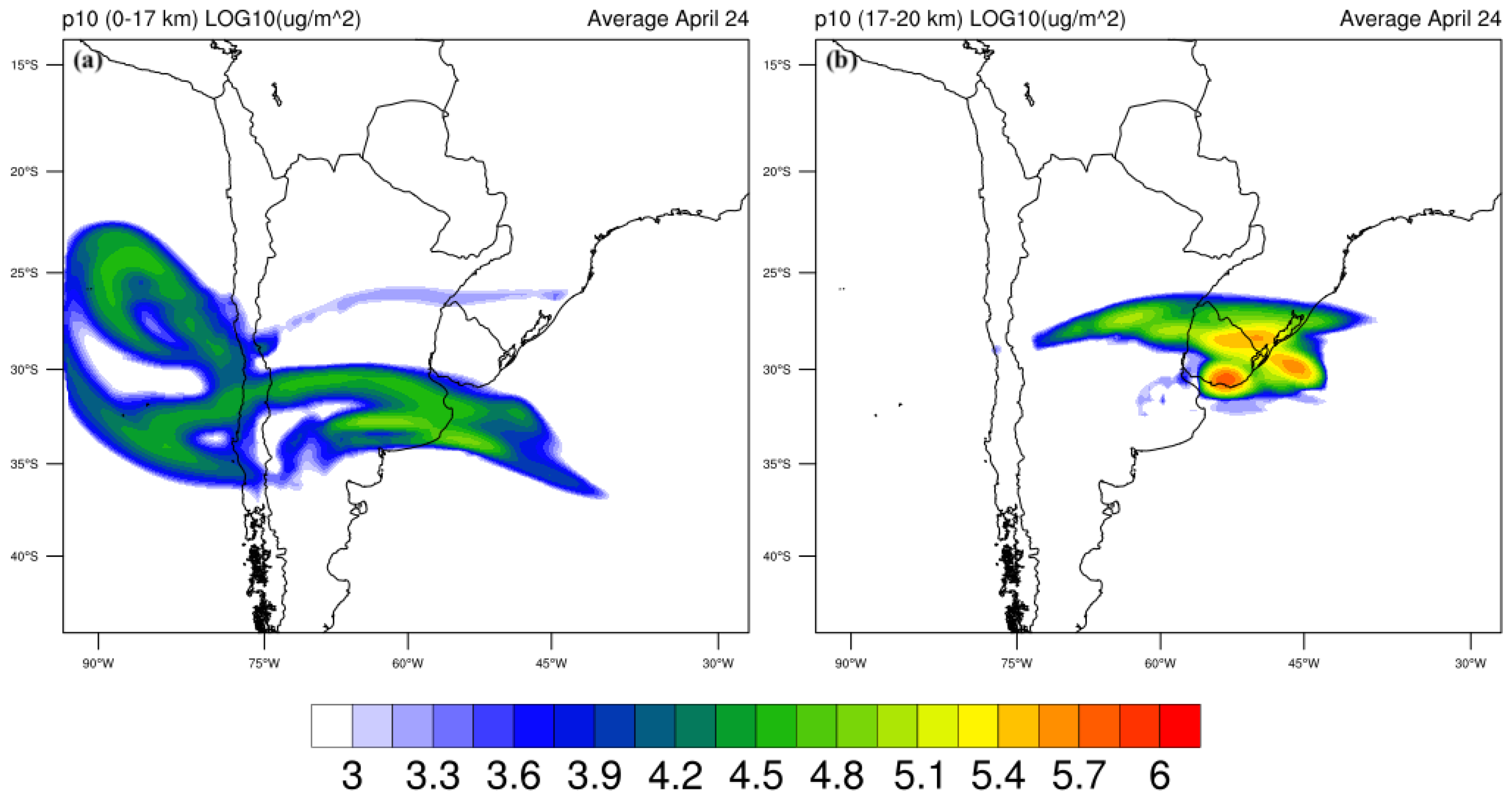

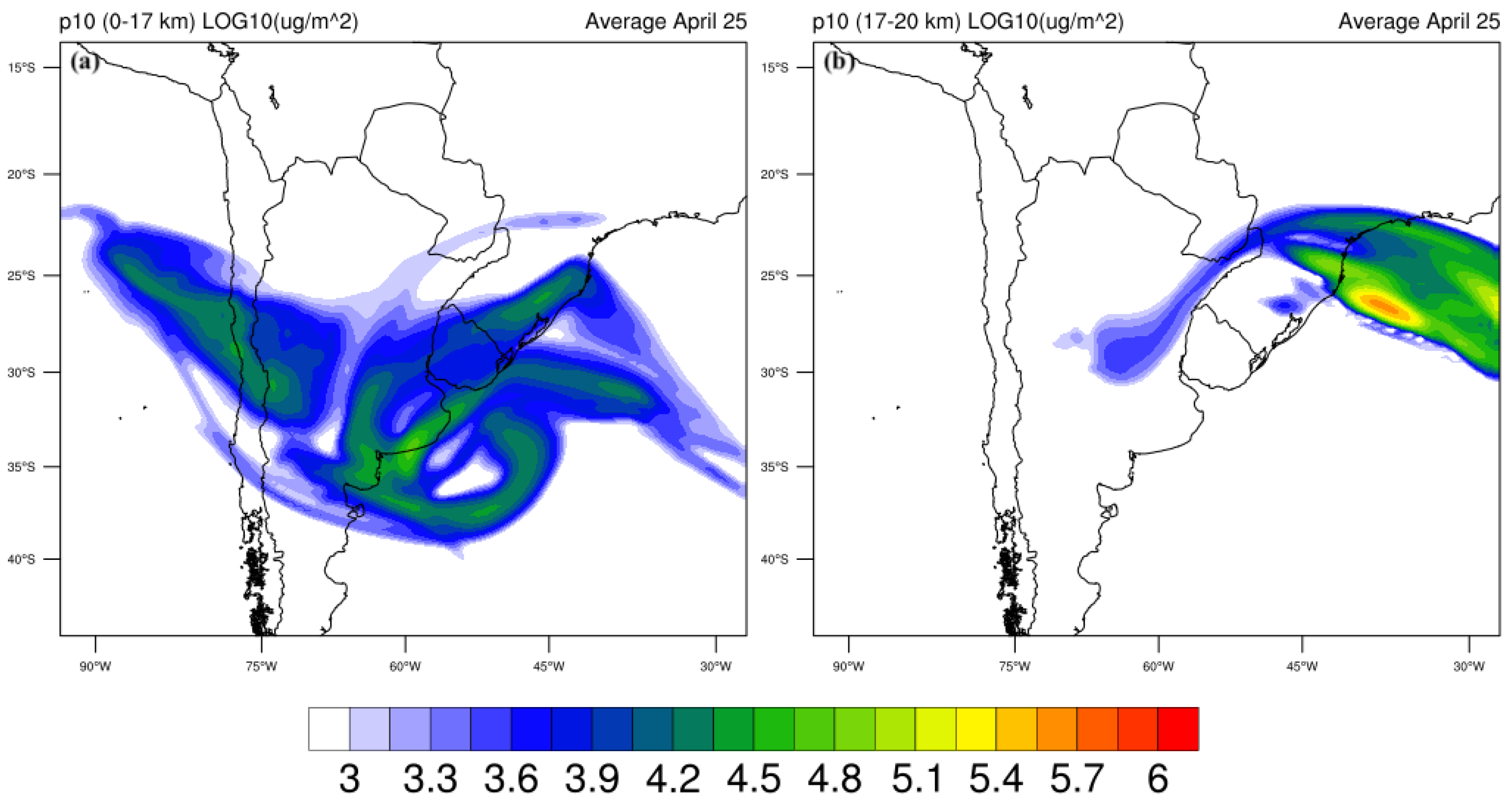

3. Results and Discussion

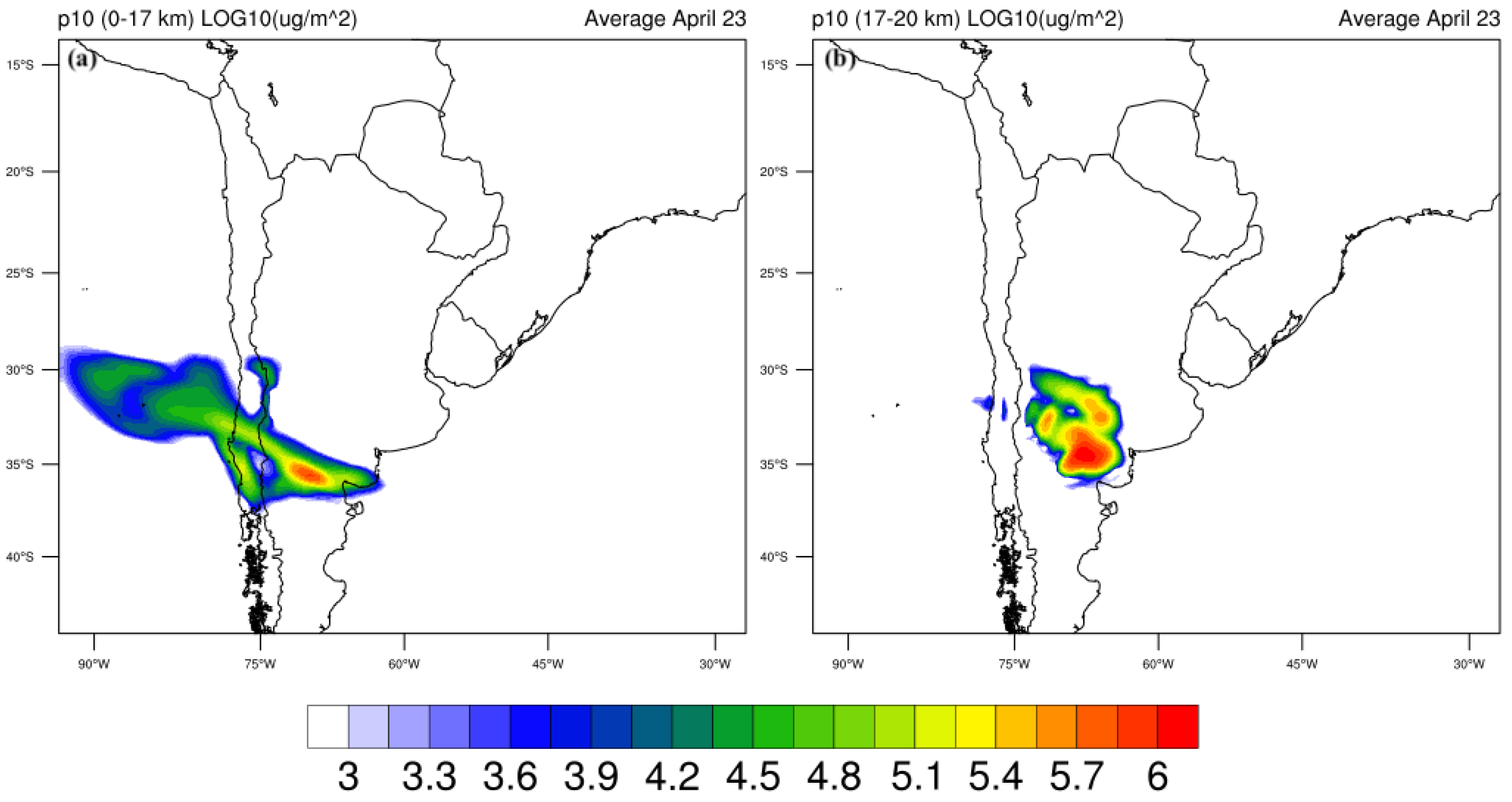

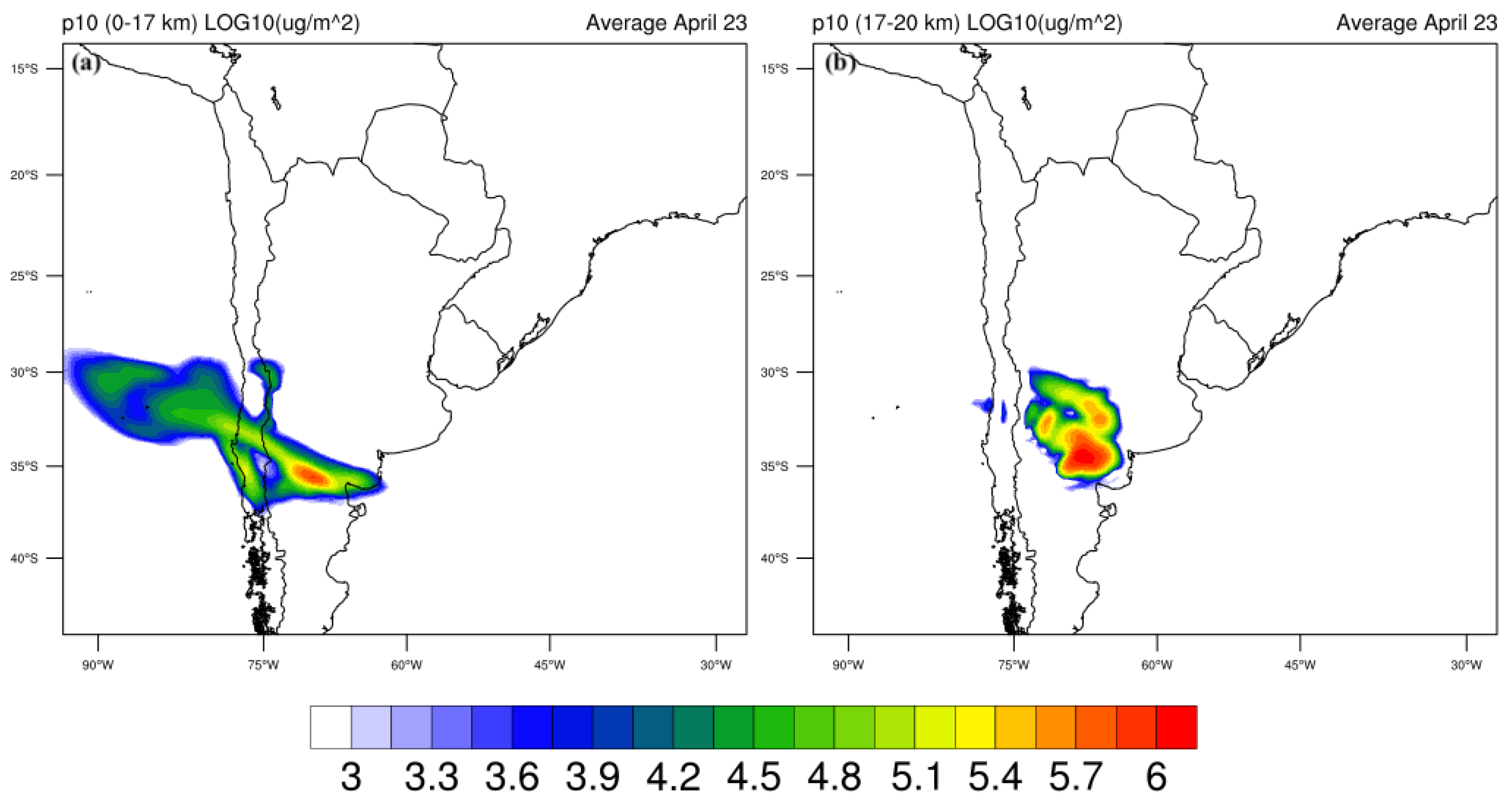

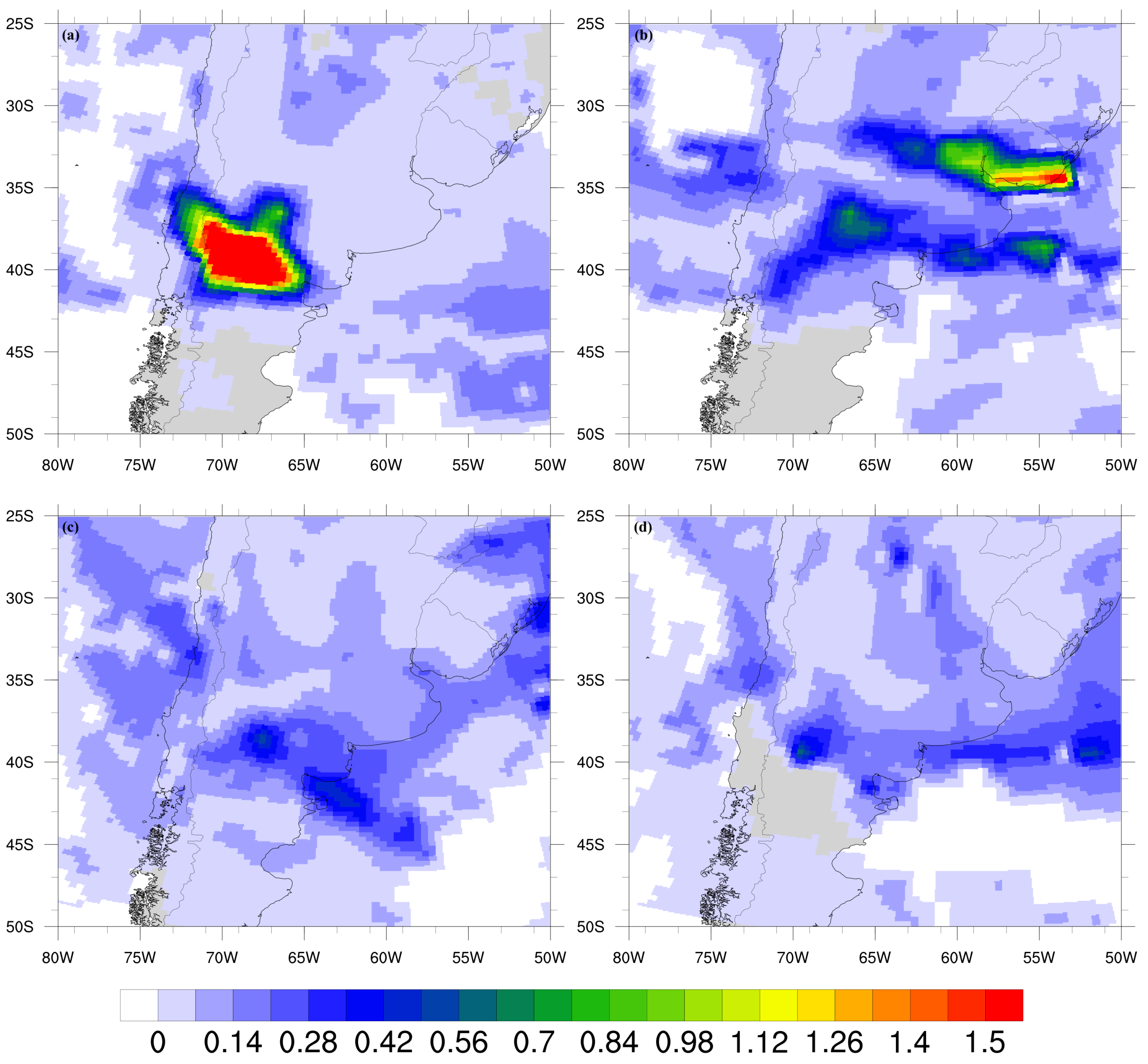

3.1. Comparison with Satellite Data

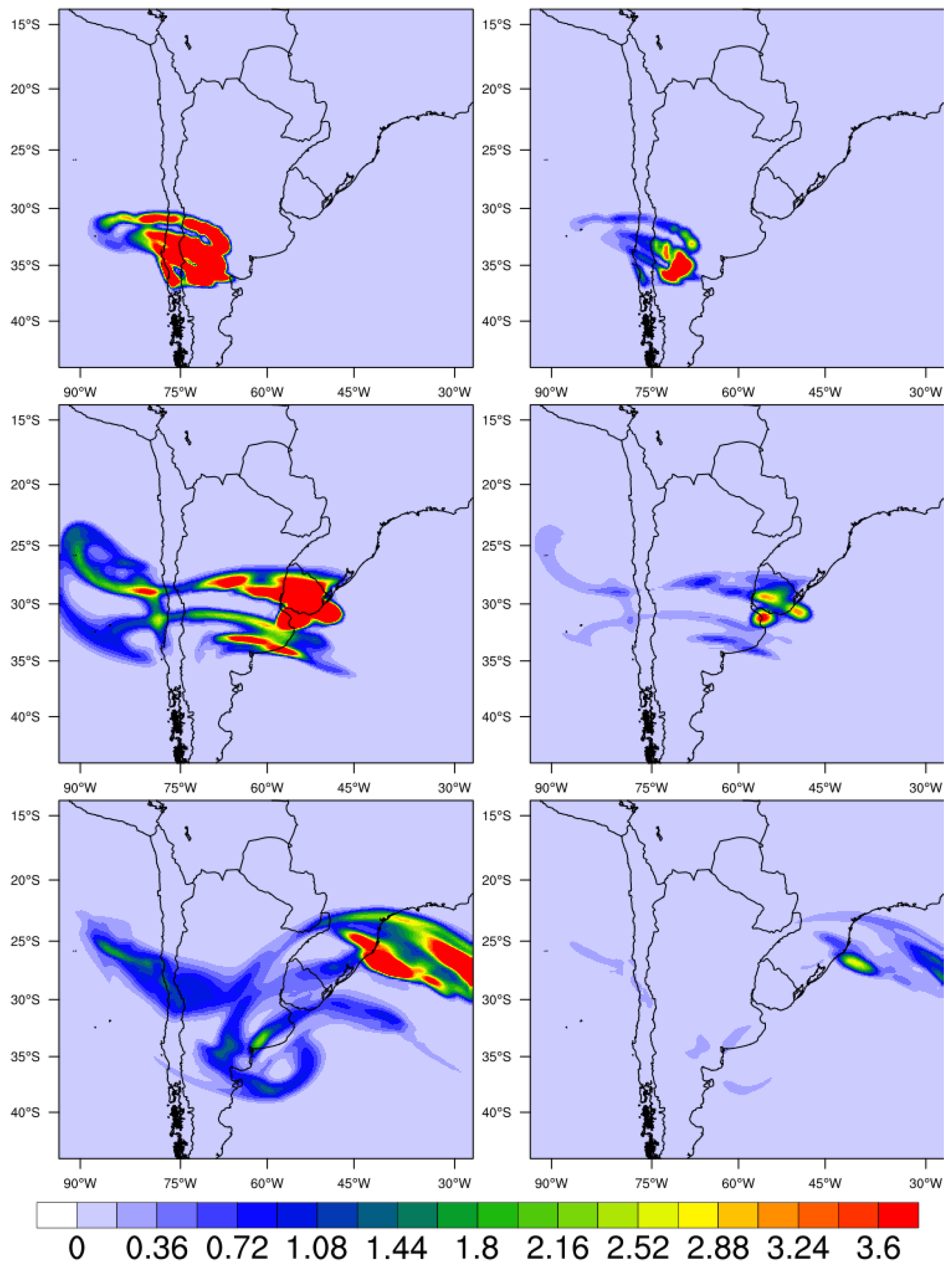

3.1.1. AERDB_D3_VIIRS

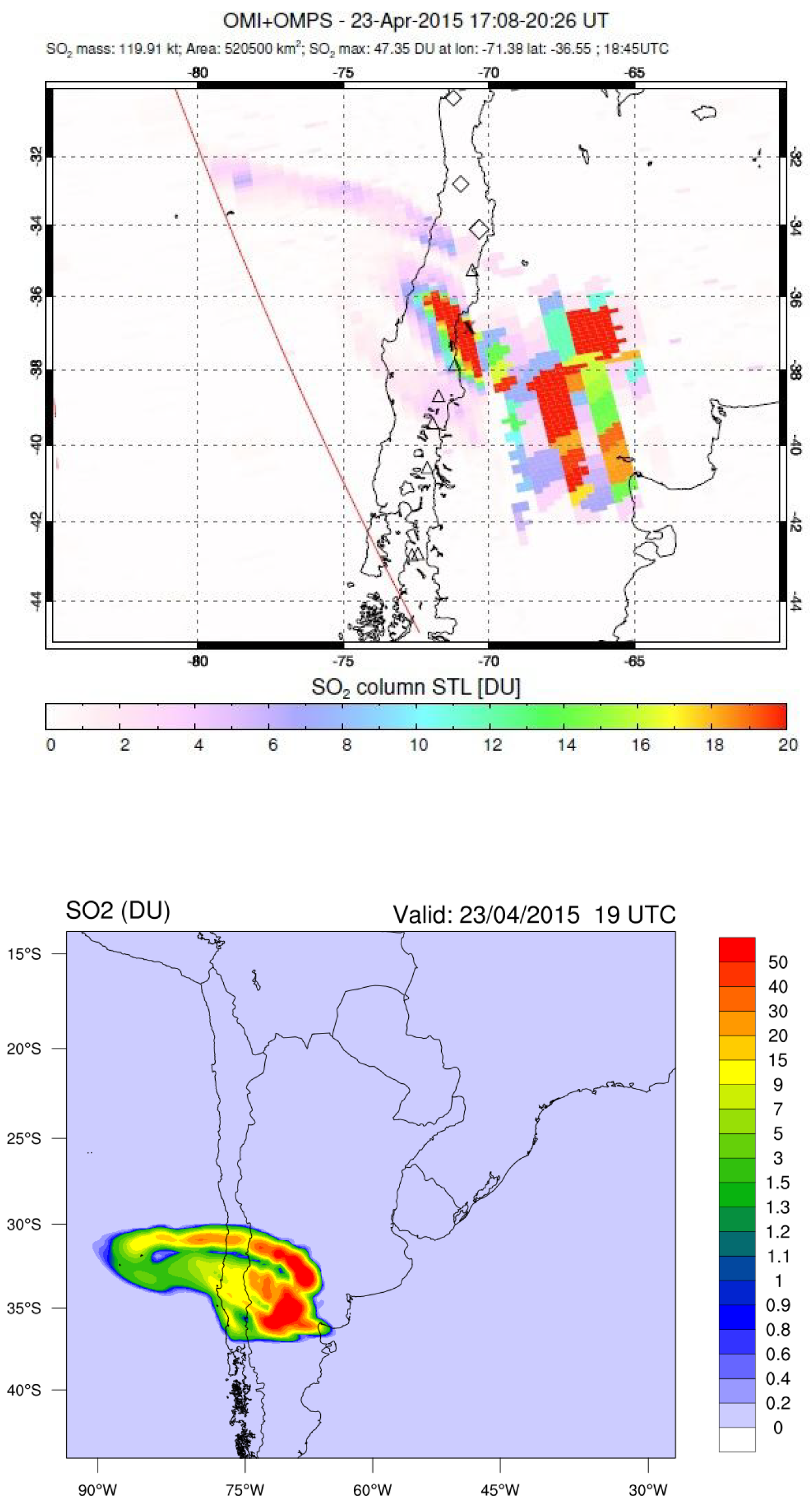

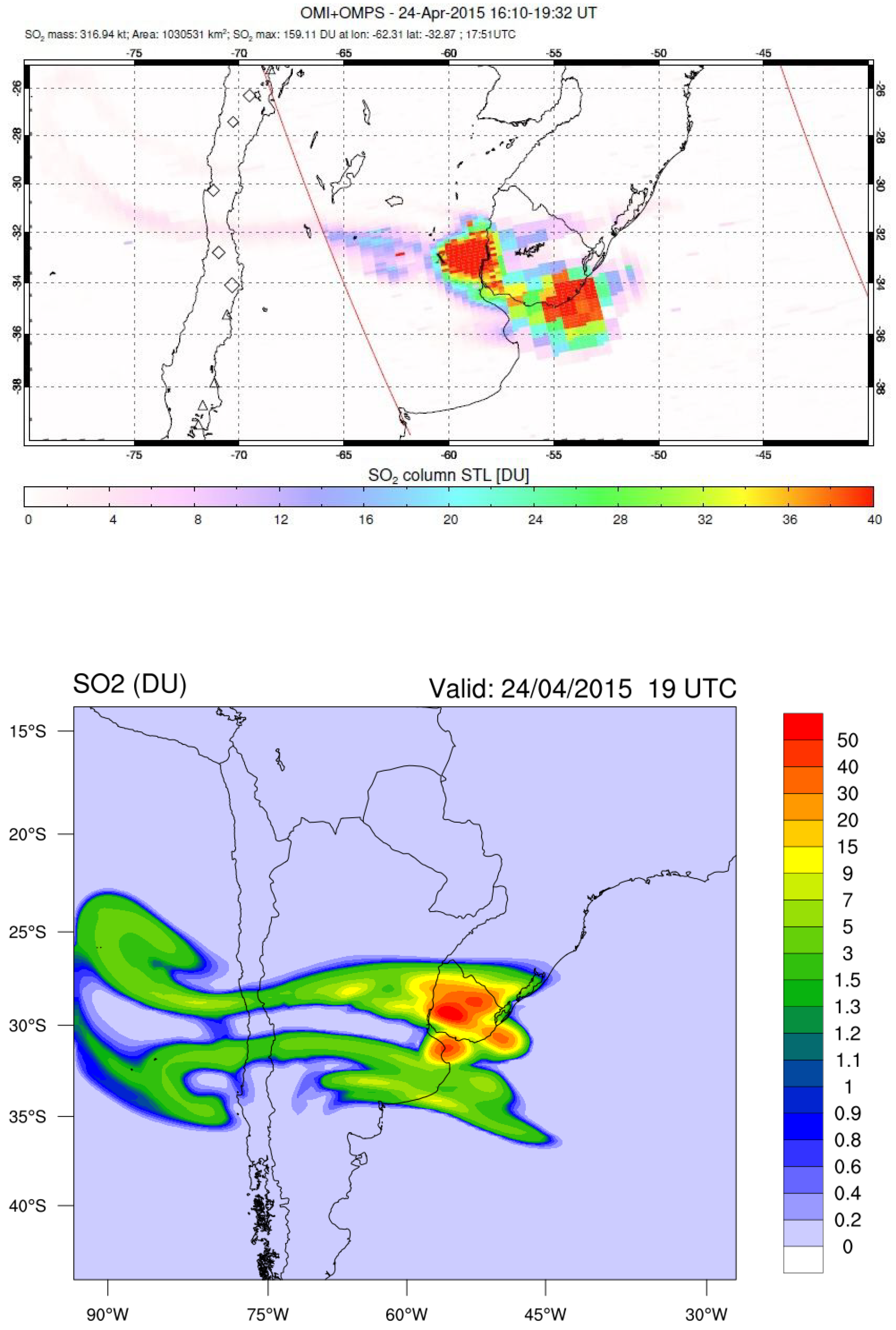

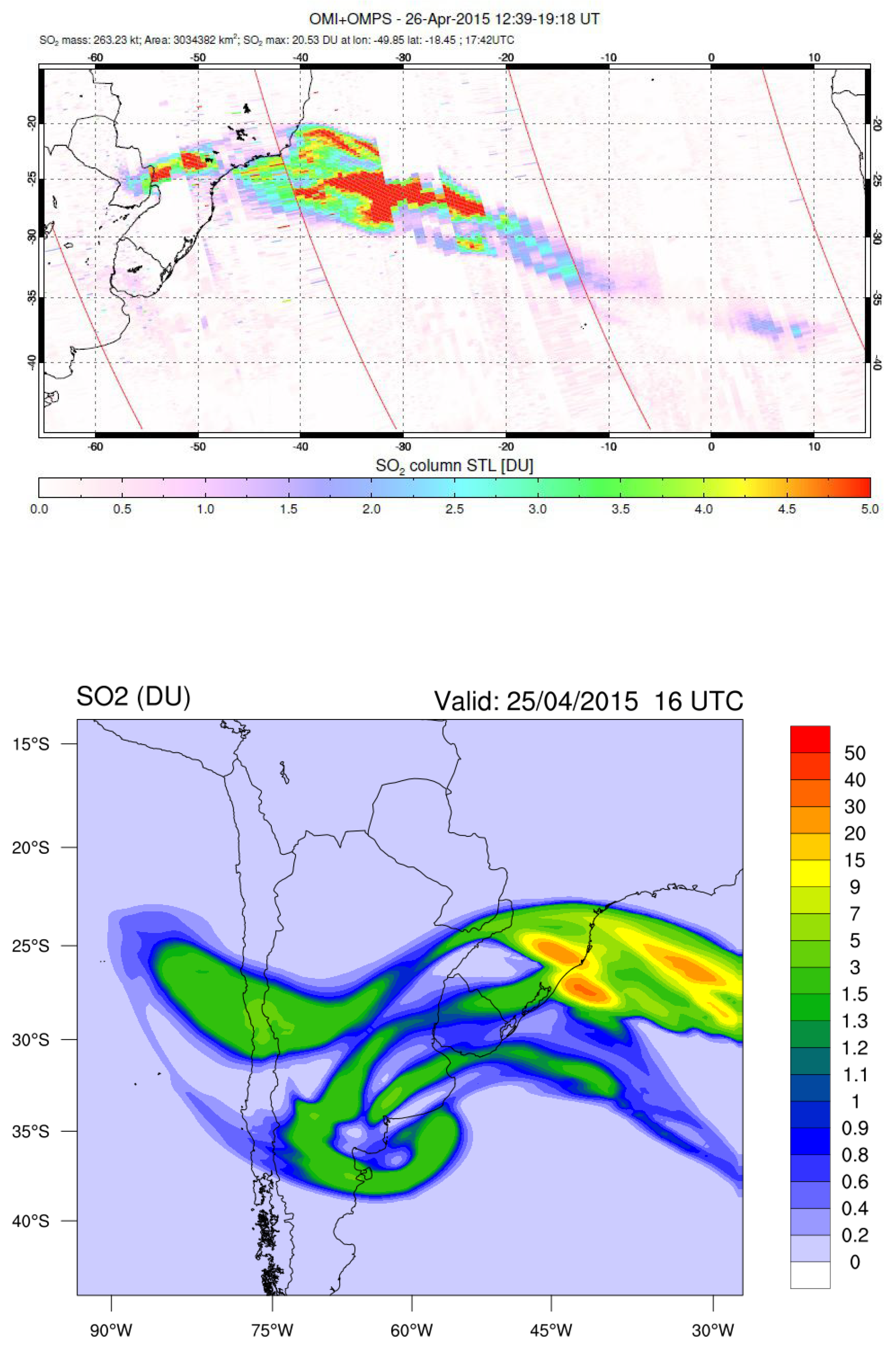

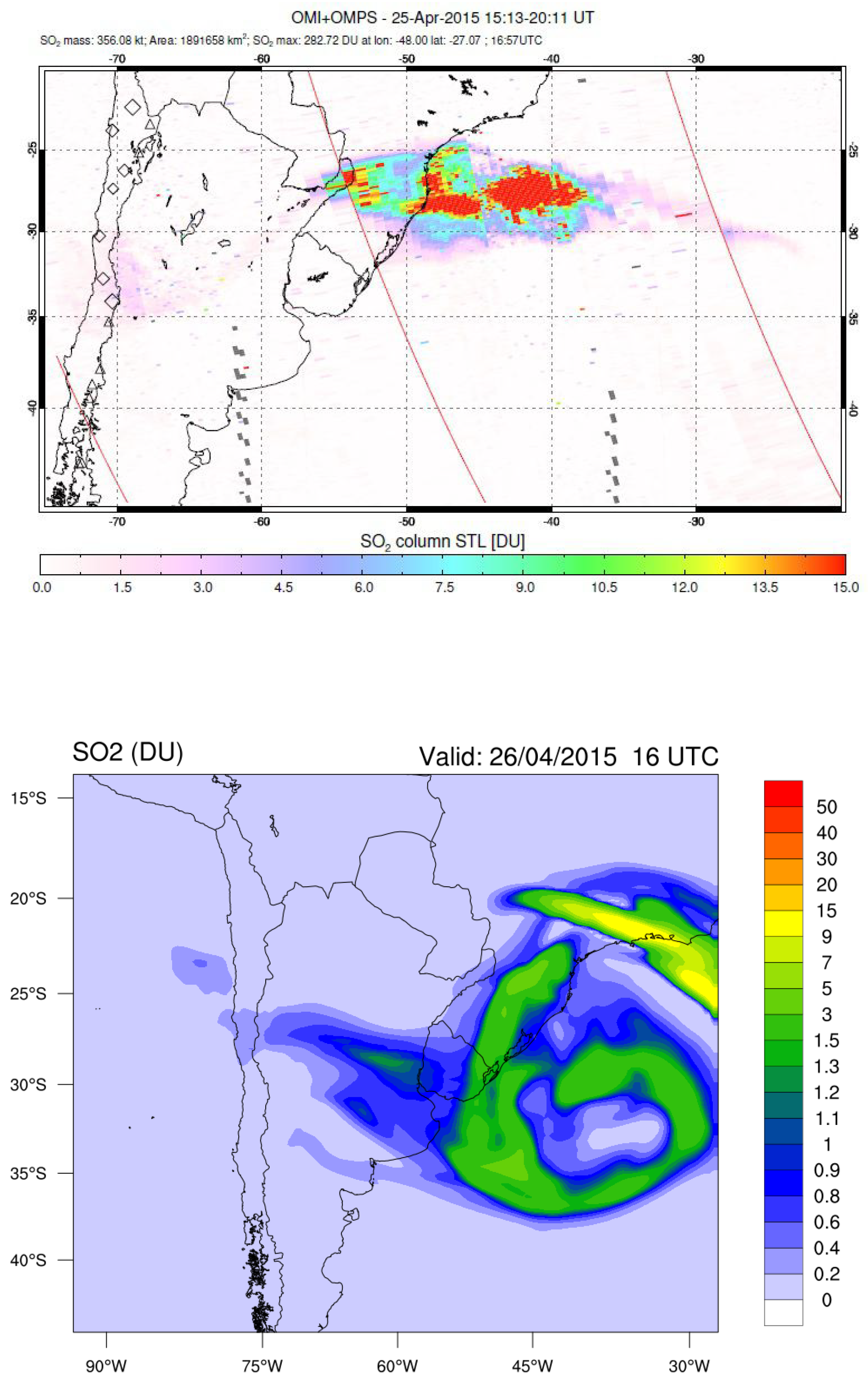

3.1.2. OMI/OMPS

4. Conclusions

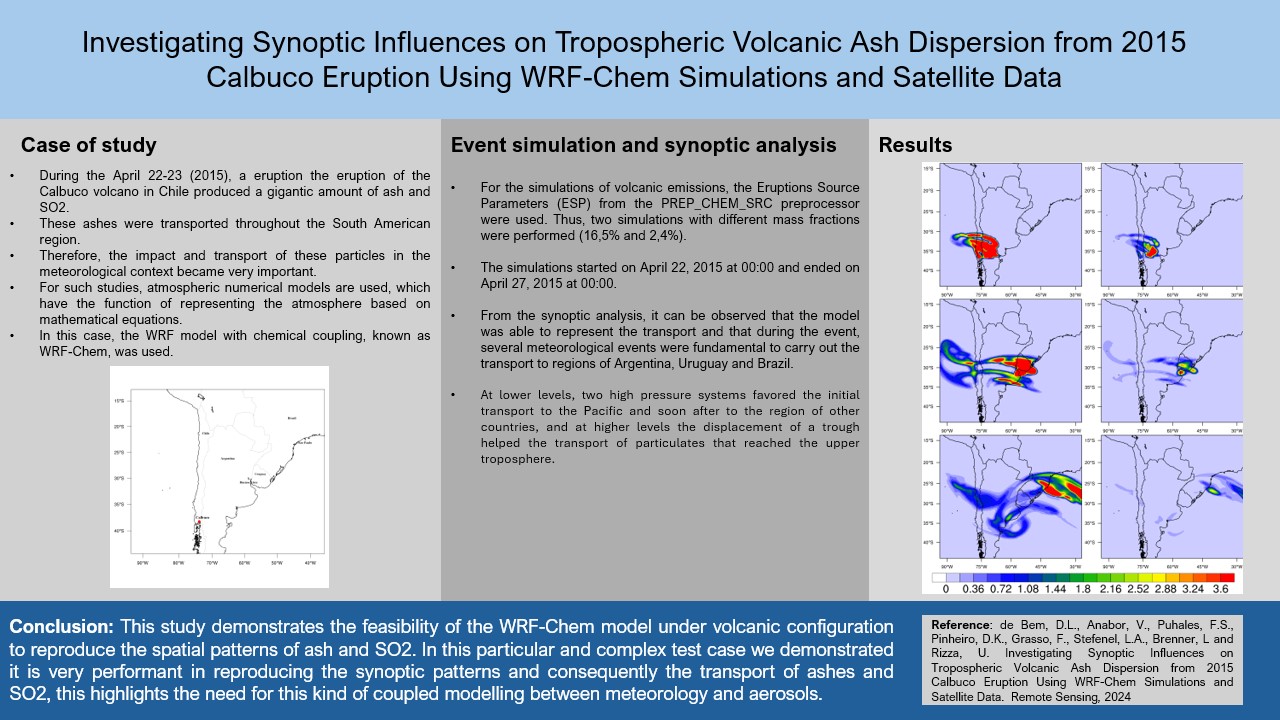

- From the meteorology perspective, the WRF-ARW core of the WRF-Chem model has successively reproduced the synoptic patterns that are responsible for the ash transport. The fine ash from the two massive eruptions of Mount Calbuco contaminated the airspace around the volcano within a radius of about 4000 km in a few days. This is a very important aspect that should be considered, in fact, the complexity of the problem requires an integrated approach consisting of an online coupling between meteorology and aerosols.

- The comparison between model-AOD with the experimental data allows us to select the optimal granulometry distribution (S1) that may be important to utilize in subsequent studies.

- The comparison between the SO2 dispersion maps simulated by the model and OMI-OMPS retrievals report a good agreement likely with a little overestimation of the simulated concentration of SO2 mainly caused by the overestimation of the SO2 emission rate.

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Ramaswamy, V.; Collins, W.; Haywood, J.; Lean, J.; Mahowald, N.; Myhre, G.; Naik, V.; Shine, K.P.; Soden, B.; Stenchikov, G.; others. Radiative forcing of climate: The historical evolution of the radiative forcing concept, the forcing agents and their quantification, and applications. Meteorological Monographs 2019, 59, 14–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, R.J.; Schwartz, S.; Hales, J.; Cess, R.D.; Coakley Jr, J.; Hansen, J.; Hofmann, D. Climate forcing by anthropogenic aerosols. Science 1992, 255, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twomey, S. The influence of pollution on the shortwave albedo of clouds. Journal of the atmospheric sciences 1977, 34, 1149–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textor, C.; Graf, H.F.; Timmreck, C.; Robock, A. Emissions from volcanoes. In Emissions of atmospheric trace compounds; Springer, 2004; pp. 269–303. [CrossRef]

- Arghavani, S.; Rose, C.; Banson, S.; Lupascu, A.; Gouhier, M.; Sellegri, K.; Planche, C. The effect of using a new parameterization of nucleation in the WRF-Chem model on new particle formation in a passive volcanic plume. Atmosphere 2021, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigaridis, K.; Krol, M.; Dentener, F.; Balkanski, Y.; Lathiere, J.; Metzger, S.; Hauglustaine, D.; Kanakidou, M. Change in global aerosol composition since preindustrial times. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2006, 6, 5143–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, M.P.; Thomason, L.W.; Trepte, C.R. Atmospheric effects of the Mt Pinatubo eruption. Nature 1995, 373, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellitto, P.; Podglajen, A.; Belhadji, R.; Boichu, M.; Carboni, E.; Cuesta, J.; Duchamp, C.; Kloss, C.; Siddans, R.; Bègue, N.; others. The unexpected radiative impact of the Hunga Tonga eruption of 15th January 2022. Communications Earth & Environment 2022, 3, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, C.R.; Moreno, H.; López-Escobar, L.; Clavero, J.E.; Lara, L.E.; Naranjo, J.A.; Parada, M.A.; Skewes, M.A. Chilean volcanoes 2007.

- Newhall, C.G.; Self, S. The volcanic explosivity index (VEI) an estimate of explosive magnitude for historical volcanism. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 1982, 87, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ferrán, O. Volcanes de Chile. Instituto Geográfico Militar. Santiago 1995, 635. [Google Scholar]

- Petit-Breuilh, M. Cronologia eruptiva historica de los volcanes Osorno y Calbuco, Andes del Sur (41∘-41∘30’s); Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería, 1999.

- Daga, R.; Guevara, S.R.; Poire, D.G.; Arribére, M. Characterization of tephras dispersed by the recent eruptions of volcanoes Calbuco (1961), Chaitén (2008) and Cordón Caulle Complex (1960 and 2011), in Northern Patagonia. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 2014, 49, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bègue, N.; Vignelles, D.; Berthet, G.; Portafaix, T.; Payen, G.; Jégou, F.; Bencherif, H.; Jumelet, J.; Vernier, J.P.; Lurton, T.; others. Long-range transport of stratospheric aerosols in the Southern Hemisphere following the 2015 Calbuco eruption. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2017, 17, 15019–15036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JS Lopes, F.; Silva, J.J.; Antuna Marrero, J.C.; Taha, G.; Landulfo, E. Synergetic aerosol layer observation after the 2015 calbuco volcanic eruption event. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eaton, A.R.; Amigo, Á.; Bertin, D.; Mastin, L.G.; Giacosa, R.E.; González, J.; Valderrama, O.; Fontijn, K.; Behnke, S.A. Volcanic lightning and plume behavior reveal evolving hazards during the April 2015 eruption of Calbuco volcano, Chile. Geophysical Research Letters 2016, 43, 3563–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.; Morgavi, D.; Arzilli, F.; Daga, R.; Caselli, A.; Reckziegel, F.; Viramonte, J.; Díaz-Alvarado, J.; Polacci, M.; Burton, M.; others. Eruption dynamics of the 22–23 April 2015 Calbuco Volcano (Southern Chile): Analyses of tephra fall deposits. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 2016, 317, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, F.S.; Corradini, S.; Mereu, L.; Kylling, A.; Montopoli, M.; Cimini, D.; Merucci, L.; Stelitano, D. Multisatellite multisensor observations of a Sub-Plinian volcanic eruption: the 2015 Calbuco explosive event in Chile. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2018, 56, 2597–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastin, L.G.; Van Eaton, A.R. Comparing simulations of umbrella-cloud growth and ash transport with observations from Pinatubo, Kelud, and Calbuco volcanoes. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaiger, H.F.; Denlinger, R.P.; Mastin, L.G. Ash3d: A finite-volume, conservative numerical model for ash transport and tephra deposition. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castorina, G.; Semprebello, A.; Gattuso, A.; Salerno, G.; Sellitto, P.; Italiano, F.; Rizza, U. Modelling Paroxysmal and Mild-Strombolian Eruptive Plumes at Stromboli and Mt. Etna on 28 August 2019. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuefer, M.; Freitas, S.; Grell, G.; Webley, P.; Peckham, S.; McKeen, S.; Egan, S. Inclusion of ash and SO 2 emissions from volcanic eruptions in WRF-Chem: Development and some applications. Geoscientific Model Development 2013, 6, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenchikov, G.; Ukhov, A.; Osipov, S. Modeling of Instantaneous and Adjusted Radiative Forcing of the 2022 Hunga Volcano Explosion. Technical report, Copernicus Meetings, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fast, J.D.; Gustafson Jr, W.I.; Easter, R.C.; Zaveri, R.A.; Barnard, J.C.; Chapman, E.G.; Grell, G.A.; Peckham, S.E. Evolution of ozone, particulates, and aerosol direct radiative forcing in the vicinity of Houston using a fully coupled meteorology-chemistry-aerosol model. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2006, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenchikov, G.; Lahoti, N.; Diner, D.J.; Kahn, R.; Lioy, P.J.; Georgopoulos, P.G. Multiscale plume transport from the collapse of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. Environmental Fluid Mechanics 2006, 6, 425–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seluchi, M.E.; Marengo, J.A. Tropical–midlatitude exchange of air masses during summer and winter in South America: Climatic aspects and examples of intense events. International Journal of Climatology: A Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2000, 20, 1167–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Seluchi, M.E. Tropical mid-latitude exchange of air masses in South America. Part I: Some climatic aspects. Trabajo presentado en el VIII Congreso Latinoamericano e Ibérico de Meteorología y X Congresso Brasileiro de Meteorologia, Brasilia, Brasil, 1998.

- Gan, M.A.; Rao, V.B. The influence of the Andes Cordillera on transient disturbances. Monthly Weather Review 1994, 122, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seluchi, M.E.; Garreaud, R.; Norte, F.A.; Saulo, A.C. Influence of the subtropical Andes on baroclinic disturbances: A cold front case study. Monthly Weather Review 2006, 134, 3317–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyamurty, P.; Dos Santos, R.P.; Lems, M.A.M. On the stationary trough generated by the Andes. Monthly Weather Review 1980, 108, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivy, D.J.; Solomon, S.; Kinnison, D.; Mills, M.J.; Schmidt, A.; Neely III, R.R. The influence of the Calbuco eruption on the 2015 Antarctic ozone hole in a fully coupled chemistry-climate model. Geophysical Research Letters 2017, 44, 2556–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, N.A. The general circulation of the atmosphere: A numerical experiment. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 1956, 82, 123–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, H.R.; Hodges, K.I.; Gan, M.A.; Ferreira, N.J. A new perspective of the climatological features of upper-level cut-off lows in the Southern Hemisphere. Climate Dynamics 2017, 48, 541–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, G.J.; Uccellini, L.W. Diagnosing coupled jet-streak circulations for a northern plains snow band from the operational nested-grid model. Weather and forecasting 1992, 7, 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccellini, L.W.; Kocin, P.J. The interaction of jet streak circulations during heavy snow events along the east coast of the United States. Weather and Forecasting 1987, 2, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzilli, F.; Morgavi, D.; Petrelli, M.; Polacci, M.; Burton, M.; Di Genova, D.; Spina, L.; La Spina, G.; Hartley, M.E.; Romero, J.E.; others. The unexpected explosive sub-Plinian eruption of Calbuco volcano (22–23 April 2015; southern Chile): Triggering mechanism implications. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 2019, 378, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seluchi, M.E.; Norte, F.A.; Satyamurty, P.; Chou, S.C. Analysis of three situations of the foehn effect over the Andes (zonda wind) using the Eta–CPTEC regional model. Weather and forecasting 2003, 18, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grell, G.A.; Peckham, S.E.; Schmitz, R.; McKeen, S.A.; Frost, G.; Skamarock, W.C.; Eder, B. Fully coupled “online” chemistry within the WRF model. Atmospheric environment 2005, 39, 6957–6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.; Rood, R.B.; Lin, S.J.; Müller, J.F.; Thompson, A.M. Atmospheric sulfur cycle simulated in the global model GOCART: Model description and global properties. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2000, 105, 24671–24687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastin, L.G.; Guffanti, M.; Servranckx, R.; Webley, P.; Barsotti, S.; Dean, K.; Durant, A.; Ewert, J.W.; Neri, A.; Rose, W.I.; others. A multidisciplinary effort to assign realistic source parameters to models of volcanic ash-cloud transport and dispersion during eruptions. Journal of volcanology and Geothermal Research 2009, 186, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensen, T.; Stuefer, M.; Webley, P.; Grell, G.; Freitas, S. Qualitative comparison of Mount Redoubt 2009 volcanic clouds using the PUFF and WRF-Chem dispersion models and satellite remote sensing data. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 2013, 259, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scollo, S.; Del Carlo, P.; Coltelli, M. Tephra fallout of 2001 Etna flank eruption: Analysis of the deposit and plume dispersion. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 2007, 160, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, W.I.; Durant, A.J. Fine ash content of explosive eruptions. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 2009, 186, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, S.R.; Longo, K.M.; Alonso, M.a.; Pirre, M.; Marécal, V.; Grell, G.; Stockler, R.; Mello, R.; Sánchez Gácita, M. PREP-CHEM-SRC–1.0: a preprocessor of trace gas and aerosol emission fields for regional and global atmospheric chemistry models. Geoscientific Model Development 2011, 4, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- for Environmental Prediction/National Weather Service/NOAA/US Department of Commerce, N.C. NCEP GDAS/FNL 0.25 degree global tropospheric analyses and forecast grids, research data archive at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Computational and Information Systems Laboratory 2015. [CrossRef]

- Sparks, R.S.J.; Bursik, M.; Carey, S.; Gilbert, J.; Glaze, L.; Sigurdsson, H.; Woods, A. Volcanic plumes; John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 1997.

- Olson, J.B.; Kenyon, J.S.; Angevine, W.; Brown, J.M.; Pagowski, M.; Sušelj, K.; others. A description of the MYNN-EDMF scheme and the coupling to other components in WRF–ARW 2019. [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.B.; Smirnova, T.; Kenyon, J.S.; Turner, D.D.; Brown, J.M.; Zheng, W.; Green, B.W. A description of the MYNN surface-layer scheme 2021. [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, T.G.; Brown, J.M.; Benjamin, S.G.; Kenyon, J.S. Modifications to the rapid update cycle land surface model (RUC LSM) available in the weather research and forecasting (WRF) model. Monthly weather review 2016, 144, 1851–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, M.; Niino, H. An improved Mellor–Yamada level-3 model with condensation physics: Its design and verification. Boundary-layer meteorology 2004, 112, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, H.; Thompson, G.; Tatarskii, V. Impact of cloud microphysics on the development of trailing stratiform precipitation in a simulated squall line: Comparison of one-and two-moment schemes. Monthly weather review 2009, 137, 991–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, H.; Milbrandt, J.A.; Bryan, G.H.; Ikeda, K.; Tessendorf, S.A.; Thompson, G. Parameterization of cloud microphysics based on the prediction of bulk ice particle properties. Part II: Case study comparisons with observations and other schemes. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 2015, 72, 312–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, N.; Jeong, M.J.; Bettenhausen, C.; Sayer, A.; Hansell, R.; Seftor, C.; Huang, J.; Tsay, S.C. Enhanced Deep Blue aerosol retrieval algorithm: The second generation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2013, 118, 9296–9315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Y.; Tanré, D.; Remer, L.A.; Vermote, E.; Chu, A.; Holben, B. Operational remote sensing of tropospheric aerosol over land from EOS moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 1997, 102, 17051–17067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, A.M.; Hsu, N.C.; Bettenhausen, C.; Holz, R.E.; Lee, J.; Quinn, G.; Veglio, P. Cross-calibration of S-NPP VIIRS moderate-resolution reflective solar bands against MODIS Aqua over dark water scenes. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2017, 10, 1425–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, A. Infrared radiative transfer calculations for volcanic ash clouds. Geophysical research letters 1989, 16, 1293–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, A.; Hsu, N.; Lee, J.; Bettenhausen, C.; Kim, W.; Smirnov, A. Satellite Ocean Aerosol Retrieval (SOAR) algorithm extension to S-NPP VIIRS as part of the “Deep Blue” aerosol project. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2018, 123, 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 |

| var | Size bins | S0 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S8 | S9 |

| vash_1 | 1-2 mm | 22.0 | 24.0 | 22.0 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 0.0 |

| vash_2 | 0.5-1 mm | 5.0 | 25.0 | 5.0 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 0.0 |

| vash_3 | 0.25-0.5 mm | 4.0 | 20.0 | 4.0 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 0.0 |

| vash_4 | 125-250 µm | 5.0 | 12.0 | 5.0 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 9.0 |

| vash_5 | 62.5-125 µm | 24.5 | 9.0 | 24.5 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 22.0 |

| vash_6 | 31.25-62.5 µm | 12.0 | 4.3 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 23.0 |

| vash_7 | 15.625-31.25 µm | 11.0 | 3.3 | 11.0 | 16.3 | 16.3 | 21.0 |

| vash_8 | 7.8125-15.625 µm | 8.0 | 1.3 | 8.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 18.0 |

| vash_9 | 3.9065-7.8125 µm | 5.0 | 0.6 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 7.0 |

| vash_10 | <3.9065 µm | 3.0 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 0.0 |

| day | granule time |

| 23 | 19:10 - 19:16 |

| 24 | 17:10 - 17:16 |

| 25 | 18:29 - 18:36 |

| 26 | 18:12 - 18:17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).