Submitted:

05 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Factors Affecting the Quality of the Bakery Product

2.1. Ingredients

2.1.1. Raw Material: Size of Wheat Flour

2.1.2. Water

2.1.3. Salt

2.1.4. Wheat Bran

2.1.5. Flour Improvers

2.2. Mixing

2.2.1. Mixing Speed

2.2.3. Dough Temperature

2.2.2. Mixing Time

2.3. Leavening

2.4. Baking

3. Gluten: Structure-Function Relationship

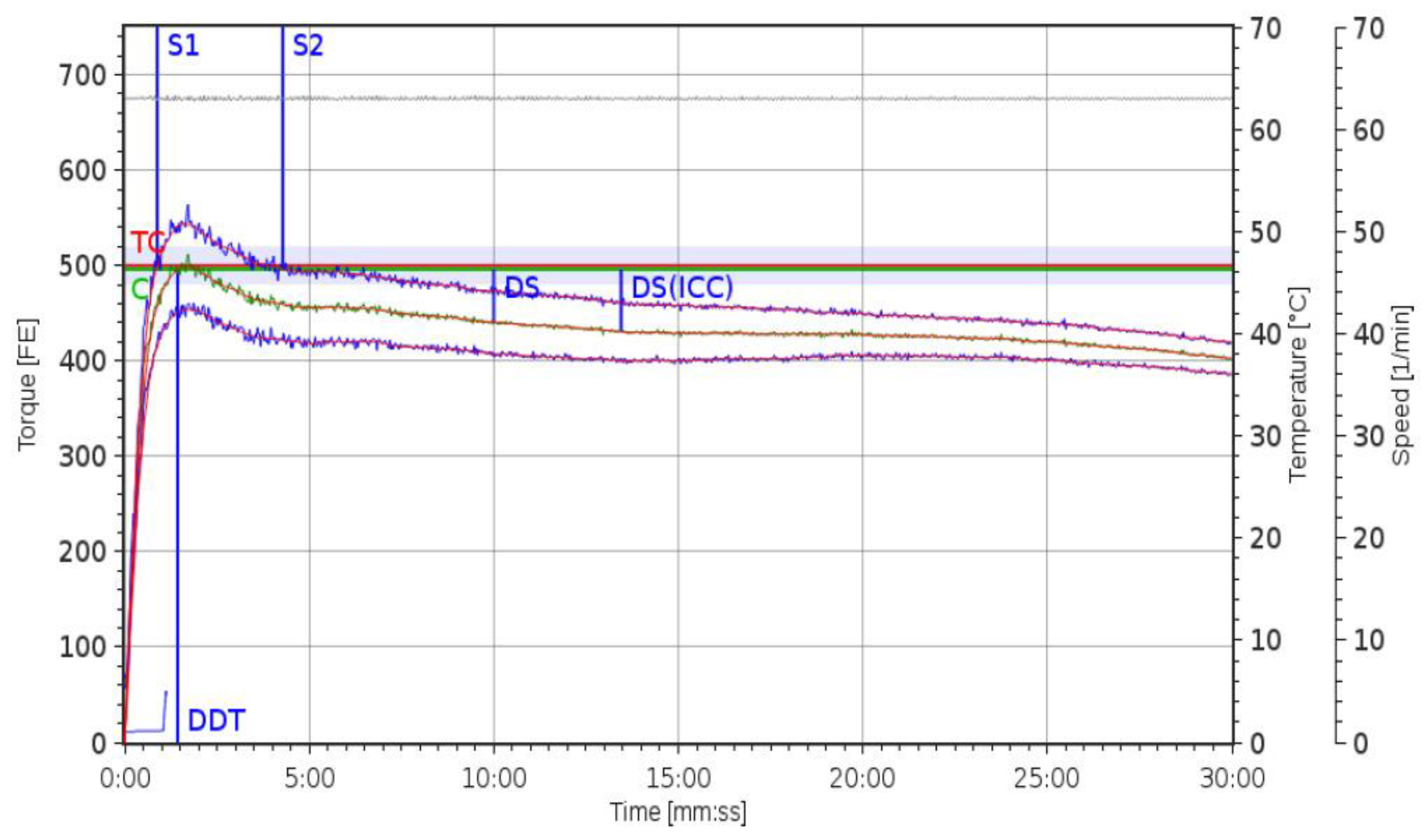

4. Rheological Tests of Wheat Dough

5. Sensory Evaluation

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bread – Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/food/bread-cereal-products/bread/worldwide (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- FAO. Crop prospects and food situation – Quarterly global report No. 2, July 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lai, H. M.; Lin, T. C. Bakery Products: Science and Technology. John Wiley & Sons, 2008, pp. 4-5.

- Breuillet, C.; Yildiz, E.; Cuq, B.; Kokini, J.L. Study of the anomalous capillary bagley factor behaviour of three types of wheat flour doughs at two moisture contents. J Texture Stud 2002, 33, 315–340. [CrossRef]

- Peighambardoust, S.H.; Van Der Goot, A.J.; Van Vliet, T.; Hamer, R.J.; Boom, R.M. Microstructure formation and rheological behaviour of dough under simple shear flow. J Cereal Sci 2006, 43, 183–197. [CrossRef]

- Córdoba, A. Quantitative fit of a model for proving of bread dough and determination of dough properties. J Food Eng 2010, 96, 440–448. [CrossRef]

- Dobraszczyk, B.J.; Morgenstern, M.P. Rheology and the breadmaking process. J Cereal Sci 2003, 38, 229–245.

- Guiné, R.P.F. Textural properties of bakery products: a review of instrumental and sensory evaluation studies. Appl Sci 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, S.; Bendini, A.; Balestra, F.; Palagano, R.; Rocculi, P.; Gallina Toschi, T. Sensory and instrumental study of taralli, a typical italian bakery product. Eur Food Res Technol 2018, 244, 73–82. [CrossRef]

- Szczesniak, A.S.; Kahn, E.L. Consumer awareness of and attitudes to food texture. J Texture Stud 1971, 3, 280 -295. [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.E.; Rosell, C.M. Relationship between instrumental parameters and sensory characteristics in gluten-free breads. Eur Food Res Technol 2012, 235, 107–117. [CrossRef]

- Lassoued, N.; Delarue, J.; Launay, B.; Michon, C. Baked Product Texture: Correlations between instrumental and sensory characterization using flash profile. J Cereal Sci 2008, 48, 133–143. [CrossRef]

- Joyner, S.H. Explaining food texture through rheology. Curr Opin Food Sci 2018, 21, 7 -14. [CrossRef]

- Tamba-Berehoiu, R.; Popa,C.N.; Vişan L.; Popescu S. Correlations between the quality parameters and the technological parameters of bread processing, important for product marketing. Rom Biotechnol Lett 2014, 19.

- Mollakhalili-Meybodi, N.; Sheidaei, Z.; Khorshidian, N.; Nematollahi, N.; Khanniri, E. Sensory attributes of wheat bread: a review of influential factors. J Food Meas Charact 2023, 2172–2181. [CrossRef]

- Haegens, N. Mixing, Dough Making, and Dough Make up. Bakery Products Science and Technology 2014, Second Edition, 17. [CrossRef]

- Koksel, F.; Scanlon, M.G.; Page, J.H. Food Res Int 2016, 89, 74 – 89. [CrossRef]

- Jerome, R.E.; Singh, S.K.; Dwivedi, M. Process analytical technology for bakery industry: a review. J Food Process Eng 2019, 42, e13143. [CrossRef]

- Farahnaki, A.; Hill, S. The effect of salt, water and temperature on wheat dough rheology. J Text Stud 2007, 38, 499-519. [CrossRef]

- Prabhasankar, P.; Rao, P.H. Effect of different milling methods on chemical composition of whole wheat flour. Eur Food Res Technol 2001, 213, 465-569. [CrossRef]

- Aprodu, I.; Banu, I.; Stoenescu, G.; Ionescu, V. Effect of the industrial milling process on the rheological behavior of different types of wheat flour. St Cerc St 2010, 11, 429-437.

- Choy, A.; Walker, C.; Panozzo, J.; Investigation of wheat milling yield based on grain hardness. Cereal Chem 2015, 92, 544-550. [CrossRef]

- Meneghetti, V.; Pohdorf, R.; Biduski, B.; Zavarese, E.; Gutkoski, L.; Elis, M. Wheat grain storage at moisture milling: control of protein quality and bakery performance. J Food Process Preserv 2019, 43. [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Dhital, S.; Hasjim, J. Effects of grain milling on starch structures and flour/starch properties. Starch 2014, 66, 15-27. [CrossRef]

- Patwa, A.; Kingsly, R.; Dogan, H.; Casada, M. Wheat mill stream properties for discrete element method modelling. American Soc Agric Biol Eng 2014, 57, 891-899. [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Wang, C.; Li, L.; Wang, X. Effects of particle size on the quality attributes of wheat flour made by the milling process. Cereal Chem 2020, 97, 172-182. [CrossRef]

- Bressiani, J.; Oro, T.; Santetti, G.S.; Almeida, J.L.; Bertolin, T.E.; Gómez, M.; Gutkoski, L.C. Properties of whole grain wheat flour and performance in bakery products as a function of particle size. J Cereal Sci 2017, 75, 269–277. [CrossRef]

- Mirza Alizadeh, A.; Peivasteh-Roudsari, L.; Tajdar-Oranj, B.; Beikzadeh, S.; Barani-Bonab, H.; Jazaeri, S. Effect of flour particle size on chemical and rheological properties of wheat flour dough. Iranian J Chem Engin 2022, 41, 682–694. [CrossRef]

- Sakhare, S.D.; Inamdar, A.A.; Soumya, C.; Indrani, D.; Rao, G.V. Effect of flour particle size on microstructural, rheological and physico-sensory characteristics of bread and south indian parotta. J Food Sci Technol 2014, 51, 4108–4113. [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Guan, E.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Bian, K. Effects of wheat flour particle size on flour physicochemical properties and steamed bread quality. Food Sci Nut 2021, 9, 4691-4700. [CrossRef]

- Protonotariou, S.; Batzaki, C.; Yanniotis, S.; Mandala, I. Effect of jet milled whole wheat flour in biscuits properties. L W T 2016, 74, 106 -113.

- Gujral H.S.; Mehta, S.; Samra, I.S.; Goyal, P. Effect of wheat bran, coarse wheat flour, and rice flour on the instrumental texture of cookies. Int J Food Prop 2003, 6, 329 – 340. [CrossRef]

- Sozer, N.; Cicerelli, L.; Heinio, R.L.; Poutanen, K. Effect of wheat bran addition on vitro starch digestibility, physiochemical and sensory properties of biscuits. J Cereal Sci 2014, 60, 105 – 113. [CrossRef]

- Putri, N.A.; Shalihah, I.M.;Widyasna, A.F.;Damayanti, R.P. A review of starch damage on physicochemical properties of flour. Food Sci Technol J 2020, 2, doi: :10.33512/fsj.v2i1.7936.

- Li, E.; Sushil, D.; Jovin, H. Effects of grain milling on starch structures and flour/starch properties. Starch 2014, 66, 15-27. [CrossRef]

- Jukic, M.; Koceva-Komlenic D.; Mastanjevic Kresimir, M.M.; Mirela, L; Popovici, C.; Nakov, G.; Lukinac, J. Influence of damaged starch on the quality parameters of wheat dough and bread. Ukr Food J 2019, 8, 512-521. [CrossRef]

- Memon, A.; Mahar, I.; Memon, R.; Soomro, S.; Harnly, J.; Memon, N.; Bhangar, M.; Luthria, D. Impact of flour particle size on nutrient and phenolic acid composition of commercial wheat varieties. J Food Comp Analysis 2020, 86. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Koksel, F.; Scanlon M.G.; Nickerson M.T. Effects of water, salt, and mixing on the rheological properties of bread dough at large and small deformations: a review. Cereal Chem 2022, 99, 709-723. [CrossRef]

- Luchian, M.I. Influence of water on dough rheology and bread quality. J Food Packag Sci 2013, 2.

- Meerts, M.; Cardinaels, R.; Oosterlinck, F.;Courtin, C.M.; Moldenaers, P. The impact of water content and mixing time on the linear and non-linear rheology of wheat flour dough. Food Bioph 2017, 12, 151-163. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.; Ghosal, D.; Mehra, A. Characterization of bread dough: rheological properties and microstructure. J Food Engin 2012, 109,104-113. [CrossRef]

- Pauly, A.; Pareyt, B.; Fierens, E.; Delcour, J.A. Fermentation affects the composition and foaming properties of the aqueous phase of dough from soft wheat flour. Food Hydro 2014, 37, 221-228. [CrossRef]

- Hardt, N.; Boom, R.; van der Goot, A. Wheat dough rheology at low water contents and the influence of xylanases. Food Res Int 2014, 66, 478-484. [CrossRef]

- Letang, C; Piau, M.; Verdier, C. Characterization of wheat flour -water doughs. Part I: Rheometry and microstructure. J Food Eng 1999, 41, 121-132. [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.J.; Chakrabarti- Bell, S. J Food Eng 2013, 115, 371-383. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shuchang, L.; Feng, X.; Ren, F.; Wang, J. Effect of hydrocolloids on gluten proteins, dough, and flour products: a review. Food Res Int 2023, 164, 112292. [CrossRef]

- Linlaud, N.; Puppo, M.; Ferrero, C. Effect of hydrocolloids on water absorption of wheat flour and farinograph and textural characteristics of dough. Cereal Chem 2009, 86, 376-382. [CrossRef]

- Dobraszczyk, B.J.; Salmanowicz, B.P. Comparison of predictions of baking volume using large deformation rheological properties. J Cereal Sci 2008, 47, 292–301. [CrossRef]

- Torbica, A.; Belović, M.; Popović, L. Comparative study of nutritional and technological quality aspects of minor cereals. J Food Sci Technol 2002, 58, 311-322. [CrossRef]

- Lacko-Bartošová, M.; Konvalina, P.; Lacko-Bartošová, L.; Štěrba, Z. Quality evaluation of emmer wheat genotypes based on rheological and Mixolab parameters. Czech J Food Sci 2019, 37, 192-198. [CrossRef]

- Biel, W.; Jaroszewska, A.; Stankowski, S.; Sobplewska, M.; Pacelik, J.K. Comparison of yield, chemical composition and farinograph properties of common and ancient wheat grains. European Food Res Technol 2021, 247, 1525-1538. [CrossRef]

- Sai Manohar, R.; Rao, P.; Haridas Rao, P. Effects of water on the rheological characteristics of biscuit dough and quality of biscuits. Eur Food Res Technol 1999, 209, 281-285. [CrossRef]

- Sangpring, Y.; Fukuoka, M.; Ban, N.; Oishi, H.; Sakai, N. Evaluation of relationship between state of wheat flour-water system and mechanical energy during mixing by colour monitoring and low-field 1h nmr technique. J Food Eng 2017, 211, 7–14. [CrossRef]

- Ștefan, E.-M.; Voicu, G.; Constantin, G.-A.; Ferdeș, M.; Muscalu, G. The effect of water hardness on rheological behaviour of dough. J Engin Stud Research 2015, 21.

- Sana, M.; Sinanai, A.; Xhabiri, G. The water quality of some sources in Albania and their influence on the dough rheology. J Hygien Engi Des 2022, 41, 170-175.

- Yang, Y.; Guan, E.; Zhang, T.; Li, M.; Bian, K. Influence of water addition methods on water mobility characterization and rheological properties of wheat flour dough. J Cereal Sci 2019, 89. [CrossRef]

- Mastromatteo, M.; Guida, M.; Danza, A.; Laverse, J.; Frisullo, P.; Lampignano, V.; Del Nobile, M.A. Rheological, microstructural and sensorial properties of durum wheat bread as affected by dough water content. Food Research International 2013, 51, 458–466. [CrossRef]

- Joossens, J. V., Sasaki, S., & Kesteloot, H. Bread as a source of salt: an international comparison. J Am Coll Nutr 1994, 13, 179-183.

- Preston, K. R. Effects of neutral salts of the lyotropic series on the physical dough properties of a Canadian red spring wheat flour. Cereal Chemistry 1989, 66, 144-148.

- Pasqualone, A.; Caponioa, F.; Pagani, M.A.; Summoa, C.; Paradiso V.M. Effect of salt reduction on quality and acceptability of durum wheat bread. Food Chem 2019, 289, pp. 575-581. [CrossRef]

- Salovaara, H. Effect of partial sodium chloride replacement by other salts on wheat dough rheology and breadmaking. Cereal Chem 1982, 59, 422-426.

- Beck, M.; Jekle, M.; & Becker, T. Impact of sodium chloride on wheat flour dough for yeast-leavened products. II. Baking quality parameters and their relationship. J Sci Food Agr 2012, 92, 299-306.

- Lynch, E. J.; Dal Bello, F.; Sheehan, E. M.; Cashman, K. D.; Arendt, E. K. Fundamental studies on the reduction of salt on dough and bread characteristics. Food Res Int 2009, 42(7), 885-891.

- Silow,C.; Axel,C.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Current status of salt reduction in bread and bakery products – A review. J Cereal Sci 2016, 72, 135-145. [CrossRef]

- Wehrle, K.; Grau, H.; Arendt, E.K. Effects of lactic acid, acetic acid, and table salt on fundamental rheological properties of wheat dough. Cereal Chem 1997, 74, 739-744.

- Silow, C.; Zannini, E.; Axel, C.; Lynch, K. M.; & Arendt, E. K. Effect of salt reduction on wheat-dough properties and quality characteristics of puff pastry with full and reduced fat content. Food Res Int 2016, 89, 330-337.

- Diler, G.; Le-Bail, A.; Chevallier, S. Salt reduction in sheeted dough: A successful technological approach. Food Res Int 2016, 88, 10-15.

- Pflaum, T.; Konitzer, K.; Hofmann, T.; Koehler, P. Influence of texture on the perception of saltiness in wheat bread. J Agr Food Chem 2013, 61(45), 10649-10658.

- Moreau, L.; Lagrange, J.; Bindzus, W.; Hill, S. Influence of sodium chloride on colour, residual volatiles and acrylamide formation in model systems and breakfast cereals. Int J Food Sci Technol 2009, 44(12), 2407-2416.

- Czuchajowska, Z.; Pomeranz, Y.; Jeffers, H. C. Water activity and moisture content of dough and bread. Cereal Chem 1989, 66(2), 128-132.

- Hemdane, S.; Jacobs, P.; Dornez, E.; Verspreet, J.; Delcour, J.; Courtin, C. Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) bran in bread making: a critical review. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safety 2016, 15. [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, J.C.; Schaber, J.A.; Bhunia, A.K.; Kokini, J.L. Mixing dynamics and molecular interactions of HMW glutenins, LMW glutenins, and gliadins analyzed by fluorescent co-localization and protein network quantification. J Cereal Sci 2019, 89. [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R.; Belton, P.S. What do we really understand about wheat gluten structure and functionality? J of Cereal Sci 2024, 103895.

- Tebben, L.; Shen, Y.; Li, Y. Improvers and functional ingredients in whole wheat bread: a review of their effects on dough properties and bread quality. Trends Food Sci Technol 2018, 81, 10–24. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Gutkoski, L.C.; Bravo-Núñez, Á. Understanding Whole-Wheat Flour and Its Effect in Breads: A Review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2020, 19, 3241–3265. [CrossRef]

- Navrotskyi, S.; Guo, G.; Baenziger, P.S.; Xu, L.; Rose, D.J. impact of wheat bran physical properties and chemical composition on whole grain flour mixing and baking properties. J Cereal Sci 2019, 89. [CrossRef]

- Heiniö,R.L.; Noort, M.W.J.;Katina, K.; Alam, S.A.; Sozer, N.; de Kock, H.L.; Hersleth, M.;Poutanen K. Sensory characteristics of wholegrain and bran-rich cereal foods – A review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2016, 47, 25-38. [CrossRef]

- Skendi,A.; Seni, I.;Varzakas, T.;Alexopoulos, A.;Papageorgiou, M. preliminary investigation into the effect of some bakery improvers in the rheology of bread wheat dough. Biol Life Sci Forum 2021, 6. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Gao, J.; Peixuan Y.; Yang, D. History, mechanism of action, and toxicity: a review of commonly used dough rheology improvers. Critical Rev Food Sci Nutr 2023, 63, 947-963. [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EC) number 1333/2008 on food additives. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2008/1333/oj.

- Baratto, C.M.; Becker, N.B.; Gelinski, J.M.L.N.; Silveira, S.M. Influence of enzymes and ascorbic acid on dough rheology and wheat bread quality. African J Biotechnol 2015, 14. [CrossRef]

- Błaszczak, W.; Sadowska, J.; Rosell, C.M; Fornal, J. Structural changes in the wheat dough and bread with the addition of alpha-amylases. Eur Food Res Technol 2004, 219, 348–354. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Eder, S.; Schubert, S.; Gorgerat, S.; Boschet, E.; Baltensperger, L.; Windhab, E.J. Influence of amylase addition on bread quality and bread stalin. ACS Food Sci Technol, 2021 1 (6), 1143-1150.

- Cappelli, A.; Bettaccini, L.; Cini, E. The kneading process: a systematic review of the effects on dough rheology and resulting bread characteristics, including improvement strategies. Trends Food Sci Technol 2020, 104, 91–101. [CrossRef]

- Mirsaeedghazi, H.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Mohammad, S.; Mousavi, A. rheometric measurement of dough rheological characteristics and factors affecting it. Int J Agric Biol 2008, 1, 112-119. [CrossRef]

- Yazar, G. Wheat flour quality assessment by fundamental non-linear rheological methods: a critical review. Foods 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Chin, N. L.; Martin, P. J. Rheology of bread and other bakery products. Bakery Products Sci Technol 2014, 453–472. [CrossRef]

- Leroy, V.; Pitura, K. M.; Scanlon, M. G.; Page, J. H. The complex shear modulus of dough over a wide frequency range. J Non-Newt Fluid Mechan 2010, 165(9-10), 475-478.

- Yazar, G.; Duvarci, O. C.; Tavman, S.; Kokini, J. L.Effect of mixing on LAOS properties of hard wheat flour dough. J Food Eng 2016, 190, 195-204.

- Horvat, D.; Magdić, D. Šimić, G. Dvojković, K. Drezner, G. The relation between dough rheology and bread crumb properties in winter wheat. Agr Conspectus Sci 2008, 73(1), 9-12.

- Janssen, A. M.; Van Vliet, T.; Vereijken, J. M. Fundamental and empirical rheological behaviour of wheat flour doughs and comparison with bread making performance. J Cereal Sci 1996, 23(1), 43-54.

- Van Bockstaele, F.; De Leyn, I.; Eeckhout, M.;Dewettinck, K. Rheological properties of wheat flour dough and their relationship with bread volume. II. Dynamic oscillation measurements. Cereal Chem 2008, 85(6), 762-768.

- Van Bockstaele, F.; De Leyn, I.; Eeckhout, M.; Dewettinck, K. Rheological properties of wheat flour dough and the relationship with bread volume. I. Creep-recovery measurements. Cereal Chem 2008, 85(6), 753-761.

- Biesiekierski, J.R. What is gluten? J Gastroent Henteropat 2017, 32, 78-81. [CrossRef]

- Canja, C.M.; Lupu, M.; Taulea, G. The influence of mixing time on bread dough quality. Agr Food Engi 2014, 7.

- Peighambardoust, S. H., Fallah, E., Hamer, R. J., & Van Der Goot, A. J. (2010). Aeration of bread dough influenced by different way of processing. J Cereal Sci 2010, 51(1), 89-95.

- Chin, N. L.; Campbell, G. M. Dough aeration and rheology: Part 2. Effects of flour type, mixing speed and total work input on aeration and rheology of bread dough. J Sci Food Agr 2005, 85(13), 2194-2202.

- Campbell, G. M.; Martin, P. J. Bread aeration and dough rheology: An introduction. In Breadmaking 2020 (pp. 325-371). Woodhead Publishing.

- Parenti, O.; Guerrini, L.; Mompin, S.B.; Toldrà, M.; Zanoni, B. The determination of bread dough readiness during mixing of wheat flour: A review of the available methods. J Food Engi 2021, 309. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J. R.; Allen, H. M. (1992). The prediction of bread baking performance using the farinograph and extensograph. J Cereal Sci 1992 , 15(1), 79-89.

- Connelly, R. K.; McIntier, R. L. Rheological properties of yeasted and nonyeasted wheat doughs developed under different mixing conditions. J Sci Food Agr 2008, 88(13), 2309-2323.

- Wilson, A. J.; Morgenstern, M. P.; Kavale, S. Mixing response of a variable speed 125 g laboratory scale mechanical dough development mixer. J Cereal Sci 2001, 34(2), 151-158.

- Wilson, A. J.; Wooding, A. R.; Morgenstern, M. P. Comparison of work input requirement on laboratory-scale and industrial-scale mechanical dough development mixers. Cereal Chem 1997, 74(6), 715-721.

- Torbica, A.; Blažek, K. M.; Belović, M.; Hajnal, E. J. Quality prediction of bread made from composite flours using different parameters of empirical rheology. J Cereal Sci 2019, 89, 102812.

- Pastukhov, A.; Dogan, H. Studying of mixing speed and temperature impacts on rheological properties of wheat flour dough using mixolab; Agronomy Res 2014, 12, 779-786.

- Connelly, R. K.; McIntier, R. L. Rheological properties of yeasted and nonyeasted wheat doughs developed under different mixing conditions. J Sci Food Agr, 2008, 88(13), 2309-2323.

- Hwang, C. H., & Gunasekaran, S. (2001). Determining wheat dough mixing characteristics from power consumption profile of a conventional mixer. Cereal Chemistry, 78(1), 88-92.

- Chin N.L.; Campbell, G.M. Dough aeration and rheology: Part 1. Effects of mixing speed and headspace pressure on mechanical development of bread dough. J Sci Food Agr 2005, 85, 2184-2193. [CrossRef]

- Brabec, D.; Rosenau, S.; Shipman, M. Effect of mixing time and speed on experimental baking and dough testing with a 200 g pin mixer. Cereal Chem 2015, 92(5), 449-454.

- Quayson, E. T.; Marti, A.; Bonomi, F.; Atwell, W.; Seetharaman, K. Structural modification of gluten proteins in strong and weak wheat dough as affected by mixing temperature. Cereal Chem 2016, 93(2), 189-195.

- Muchová, Z.; Žitný, B. New approach to the study of dough mixing processes; Czech J Food Sci 2010, 28, 94-107.

- Başaran, A.; Göçmen, D. The effects of low mixing temperature on dough rheology and bread properties. Eur Food Res Technol 2003, 217, 138–142. [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Domínguez, G.; Vera-Domínguez, M.; Farrera-Rebollo, R.; Arana-Errasquín, R.; Mora-Escobedo, R. Rheological Changes of Dough and Bread Quality Prepared from a Sweet Dough: Effect of Temperature and Mixing Time. Int J Food Prop 2004, 7(2), 165–174. [CrossRef]

- Spies , R .Application of rheology in the bread industry . In Dough Rheology and Baked Product Texture 1990, Edited by: Faridi , H. and Faubion , J.M. 343 – 359 . New York.

- Mani, K.; Trägårdh, C.; Eliasson, A. C.; Lindahl, L. Water content, water soluble fraction, and mixing affect fundamental rheological properties of wheat flour doughs. J Food Sci 1992, 57(5), 1198-1209.

- Wehrle, K., Grau, H., & Arendt, E. K. (1997). Effects of lactic acid, acetic acid, and table salt on fundamental rheological properties of wheat dough. Cereal chemistry, 74(6), 739-744.

- Tronsmo, K. M.; Magnus, E. M.; Baardseth, P.; Schofield, J. D.; Aamodt, A.; Færgestad, E. M. Comparison of small and large deformation rheological properties of wheat dough and gluten. Cereal Chem 2003, 80(5), 587-595.

- Adebowale, O.J.; Alokun – Adesanya, O.A. Dough Mixing Time: Impact on Dough Properties, Bread-Baking Quality andConsumer Acceptability. Fed Polytech Ilaro J Pure Appl Sci 2022, 4(2), 37–43.

- Zheng, H.; Morgenstern, M.P.; Campanella, O.H.; Larsen, N.G. Rheological properties of dough during mechanical dough development. J Cereal Sci 2000, 32, 293-306. [CrossRef]

- Rozyho, R. Effect of process modification in two cycles of dough mixing on physical properties of wheat bread baked from weak flour. Food Bioprocess Technol 2014. [CrossRef]

- Devos, F. Traditional versus modern leavening systems. Cereal Foods World 2018, 63(2).

- Romano, A.; Toraldo, G.; Cavella, S.; Masi, P. Description of leavening of bread dough with mathematical modelling. J Food Eng 2007 , 83 (2), 142-148.

- Bloksma, A. H. Effect of surface tension in the gas-dough interface on the rheological behaviour of dough. Cereal Chem 1981, 58, 481-486.

- Chin, N. L.; Tan; L. H.; Yusof, Y. A.; Rahman, R. A. Relationship between aeration and rheology of breads. J Text Stud 2009, 40(6), 727-738.

- Meerts, M.; Ramirez Cervera, A.; Struyf, N.; Cardinaels, R.; Courtin, C.M.; Moldenaers, P. The effects of yeast metabolites on the rheological behaviour of the dough matrix in fermented wheat flour dough. J Cereal Sci 2018, 82, 183–189. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Ramirez, J., Carrera-Tarela, Y., Carrillo-Navas, H., Vernon-Carter, E. J., & Garcia-Diaz, S. Effect of leavening time on LAOS properties of yeasted wheat dough. Food Hydro 2019, 90, 421-432.

- van der Sman, R.G.M. Thermodynamic description of the chemical leavening in biscuits. Curr Res Food Sci 2021, 4, 191–199. [CrossRef]

- Struyf, N.; Van der Maelen, E.; Hemdane, S.; Verspreet, J.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Courtin, C.M. Bread dough and baker’s yeast: an uplifting synergy. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2017, 16, 850–867. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shehzad, A.; Khan, M. R.; Shabbir, M. A.; Amjid, M. R. Yeast, its types and role in fermentation during bread making process-A. Pakistan J Food Sci 2012, 22(3), 171-179.

- Heitmann, M.; Zannini, E.; Axel, C.; Arendt, E. Correlation of flavour profile to sensory analysis of bread produced with different saccharomyces cerevisiae originating from the baking and beverage industry. Cereal Chem 2017, 94, 746–751. [CrossRef]

- Winters, M.; Panayotides, D.; Bayrak, M.; Rémont, G.; Viejo, C.G.; Liu, D.; Le, B.; Liu, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhang, P.; et al. Defined co-cultures of yeast and bacteria modify the aroma, crumb and sensory properties of bread. J Appl Microbiol 2019, 127, 778–793. [CrossRef]

- Crowley, P.; Schober, T.J.; Clarke, C.I.; Arendt, E.K. The effect of storage time on textural and crumb grain characteristics of sourdough wheat bread. European Food Res Technol 2002, 214, 489–496. [CrossRef]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Portincasa, P.; Montemurro, M.; di Palo, D.M.; Lorusso, M.P.; de Angelis, M.; Bonfrate, L.; Genot, B.; Gobbetti, M. Sourdough fermented breads are more digestible than those started with baker’s yeast alone: an in vivo challenge dissecting distinct gastrointestinal responses. Nutrients 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Gobbetti, M.; Corsetti, A.; Rossi, J. Interaction between lactic acid bacteria and yeasts in sour-dough using a rheofermentometer; World J Microbiol Biotechnol 1995,11,625-630. [CrossRef]

- Siepmann, F.B.; Ripari, V.; Waszczynskyj, N.; Spier, M.R. Overview of sourdough technology: from production to marketing. Food Bioproc Tech 2018, 11, 242–270. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Effect of proofing on the rheology and moisture distribution of corn starch-hydroxypropylmethylcellulose gluten-free dough. Foods 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Jayaram, V.B.; Cuyvers, S.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Delcour, J.A.; Courtin, C.M. Succinic acid in levels produced by yeast (saccharomyces cerevisiae) during fermentation strongly impacts wheat bread dough properties. Food Chem 2014, 151, 421–428. [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghari, M.S.; Ardebili, S.M.S.; Asadi, G.H.; Larijani, K. Effect of sourdough, bakery yeast and sodium bicarbonate on volatile compounds, and sensory evaluation of lavash bread. J Food Process Preserv 2017, 41. [CrossRef]

- Taglieri, I.; Sanmartin, C.; Venturi, F.; Macaluso, M.; Zinnai, A.; Tavarini, S.; Serra, A.; Conte, G.; Flamini, G.; Angelini, L.G. Effect of the leavening agent on the compositional and sensorial characteristics of bread fortified with flaxseed cake. Appl Sci 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, A.; Lupori, L.; Cini, E. Baking Technology: A Systematic review of machines and plants and their effect on final products, including improvement strategies. Trends Food Sci Technol 2021, 115, 275–284. [CrossRef]

- Rouillé, J.; Chiron, H.; Colonna, P.; Della Valle, G.; Lourdin, D. Dough/crumb transition during French bread baking. J Cereal Sci 2010, 52(2), 161-169.de Kock, H.L.; Magano, N.N. Sensory tools for the development of gluten-free bakery foods. J Cereal Sci 2020, 94. [CrossRef]

- Purlis, E. Bread baking: technological considerations based on process modelling and simulation. J Food Eng 2011, 103, 92–102. [CrossRef]

- Lafiandra, D.; Shewry, P.R. Wheat glutenin polymers 2. the role of wheat glutenin subunits in polymer formation and dough quality. J Cereal Sci 2022, 106. [CrossRef]

- Wieser, H. Chemistry of gluten proteins. Food Microbiol 2007, 24, 115–119. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yue, Q.; Liu, C.; Zheng, X.; Hong, J.; Wang, N.; Bian, K. interaction between gliadin/glutenin and starch granules in dough during mixing. LWT 2021, 148. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Jin, Z.; Xu, X. Physicochemical alterations of wheat gluten proteins upon dough formation and frozen storage - a review from gluten, glutenin and gliadin perspectives. Trends Food Sci Technol 2015, 46, 189–198. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Stokes, J. R. Rheology and tribology: Two distinctive regimes of food texture sensation. Trends in Food Sci Technol 2012, 25(1), 4-12.

- Dong, Y.N.; Karboune, S. A review of bread qualities and current strategies for bread bioprotection: flavour, sensory, rheological, and textural attributes. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2021, 20, 1937–1981. [CrossRef]

- Angioloni A.; Collar, C. Bread crumb quality assessment: a plural physical approach. Europ Food Res Technol 2009, 229, 21-30. [CrossRef]

- Tietze, S.; Jekle, M.; Becker, T. Possibilities to Derive Empirical Dough Characteristics from Fundamental Rheology. Trends Food Sci Technol 2016, 57, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, A. M.; Van Vliet, T.; Vereijken, J. M. Fundamental and empirical rheological behaviour of wheat flour doughs and comparison with bread making performance. J Cereal Sci 1996, 23(1), 43-54.

- Joyner, H. S. Nonlinear (large-amplitude oscillatory shear) rheological properties and their impact on food processing and quality. Annual Rev Food Sci Technol 2021, 12(1), 591-609.

- Wang, Y.; Selomulya, C. Food rheology applications of large amplitude oscillation shear (LAOS). Trends Food Sci Technol 2022, 127, 221–244. [CrossRef]

- Civille, G.V.; Oftedal, K.N. Sensory evaluation techniques - make “good for you” taste “good.” Physiol Behav 2012, 107, 598–605. [CrossRef]

- de Kock, H.L.; Magano, N.N. Sensory tools for the development of gluten-free bakery foods. J Cereal Sci 2020, 94. [CrossRef]

- Pedreschi, F.; León, J.; Mery, D.; Moyano, P. Development of a computer vision system to measure the colour of potato chips. Food Res Int 2006, 39, 1092–1098. [CrossRef]

- Purlis, E. Browning development in bakery products - a review. J Food Eng 2010, 99, 239–249. [CrossRef]

- Cauvain, S. Breadmaking: An overview. In S. Cauvain (Ed.), Breadmaking 2012, (pp. 9–31). Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Ltd.

- Rosell, C. M. The science of doughs and bread quality. In Victor R. Preedy, Ronald Ross Watson & Vinood B. Patel (Eds.), Flour and breads and their fortification in health and disease prevention 2011, (pp. 3–14). London: Academic Press.

- Longin, F.; Beck, H.; Gütler, H.; Heilig, W.; Kleinert, M.; Rapp, M.; Stich, B. Aroma and quality of breads baked from old and modern wheat varieties and their prediction from genomic and flour-based metabolite profiles. Food Res Int 2020, 129, 108748.

- Rapp, M.; Beck, H.; Gütler, H.; Heilig, W.; Starck, N.; Römer, P.; Cuendet, C.; Uhlig, F.; Kurz, H.; Würschum, T.; Longin, C.; Friedrich, H. Spelt: Agronomy, Quality, and Flavor of Its Breads from 30 Varieties Tested across Multiple Environments. Crop Sci 2017, 57(2), 739. [CrossRef]

- Martins, Z.E.; Pinho, O.; Ferreira, I.M.P.L.V.O. Food industry by-products used as functional ingredients of bakery products. Trends Food Sci Technol 2017, 67, 106–128. [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, E.; Ozdal, T.; Gok, I. Investigation of textural, functional, and sensory properties of muffins prepared by adding grape seeds to various flours. J Food Process Preserv 2022, 46. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Rafiq, S.I.; Saini, C.S.; Hossain, S.; Rafiq, S.M. Studies on physico-chemical, functional, textural and sensory properties of flaxseed fortified bakery products. J Food Measur Charact 2024. [CrossRef]

- Belghith-Fendri, L.; Chaari, F.; Kallel, F.; Zouari-Ellouzi, S.; Ghorbel, R.; Besbes, S.; Ellouz-Chaabouni, S.; Ghribi-Aydi, D. Pea and broad bean pods as a natural source of dietary fiber: the impact on texture and sensory properties of cake. J Food Sci 2016, 81, C2360–C2366. [CrossRef]

- Bangar, S.P.; Siroha, A.K. Functional Cereals and Cereal Foods: Properties, Functionality and Applications; Springer International Publishing, 2022; ISBN 9783031056116.

- Tóth, M.; Kaszab, T.; Meretei, A. Texture profile analysis and sensory evaluation of commercially available gluten-free bread samples. Eur Food Res Technol 2022, 248, 1447–1455. [CrossRef]

- Di Cairano, M.; Condelli, N.; Galgano, F.; Caruso, M.C. Experimental gluten-free biscuits with underexploited flours versus commercial products: preference pattern and sensory characterisation by check all that apply questionnaire. Int J Food Sci Technol 2022, 57, 1936–1944. [CrossRef]

- Carson, L.; Sun, X. S. Creep-recovery of bread and correlation to sensory measurements of textural attributes. Cereal Chem 2001, 78(1), 101-104.

- Liu, Z.; Scanlon, M. G. Predicting mechanical properties of bread crumb. Food Biopr proc 2002, 81(3), 224-238.

- Nagy, M.; Meretei, A.; Fekete, A. Bread type characterization by rheological and mechanical properties. In 2007 ASAE Annual Meeting (p. 1). American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers.

- Young, L. S. Applications of texture analysis to dough and bread. In Breadmaking 2012 (pp. 562-579). Woodhead Publishing.

- Szczesniak, A.S. Texture is a sensory property. Food Qual Prefer 2002, 13, 215–225.

- Civille, G. V.; Szczesniak, A. S. Guidelines to training a texture profile panel. J Text Stud 1973, 4(2), 204-223.

- Scheuer, P. M.; Luccio, M. D.; Zibetti, A. W.; de Miranda, M. Z.; de Francisco, A. Relationship between instrumental and sensory texture profile of bread loaves made with whole-wheat flour and fat replacer. J Text Stud 2016, 47(1), 14-23.

- Callejo, M.J. Present situation on the descriptive sensory analysis of bread. J Sensory Stud 2011, 26, 255-268. [CrossRef]

| Ingredients / Processing parameters | Limits | Technological effect | Sensory effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle size of wheat flour | <125 μm | ↑ dough development time; ↑ dough stability; ↓ resistance to extension. |

soft texture; ↑ sensory characteristics. |

[28] |

| >150 μm | ↓ dough development time; ↑ water absorption level; ↑ resistance to extension. |

dense crumb grain; ↓ overall sensory quality. |

[28,29] | |

| Water | From 44% to 34% | ↑peak time; ↑ dough consistency; ↑G’ and G”. |

compact crumb with small bubbles; ↑ crust firmness. | [43,57] |

| ≈ 74% | ↓ dough consistency; ↓ G’ and G”. |

↓ loaf volume; Irregular crumb structure with large bubble. |

[57] | |

| Salt | 0% | ↓ dough strength; ↓ dough stability; |

tasteless; ↑ yeasty and sourdough-like flavours. |

[61,67] |

| 1-2% | ↑peak time; ↓ water adsorption; ↑ dough stability. |

↑ darker colour crust; ↓ floury and yeasty flavours. |

[61,68,69] | |

| Wheat bran | From 0 to 12% | ↑ dough development time; ↓ stability time; ↑weakening degree; ↑ water absorption of dough. |

↑crumb firmness ↓specific volume ↑dark crumb ↓ overall acceptability |

[71,76] |

| Ascorbic acid | 50-70 ppm | ↑dough strength; ↑ dough elasticity of the dough. |

↑ hardness; ↓ handfeel; ↓ texture; ↓ mouthfeel. |

[81] |

| L-cysteine hydrochloride | -- | ↓ resistance to extension; ↓ extensograph area; ↑ extensibility. |

↓ hardness; ↓ texture; ↓ chewiness. |

[81] |

| α-amylase | -- | ↓ dough stability; ↓ Mixograph peak height. |

↓ bread hardness; ↑ bread volume; ↑ crumb structure. |

[74,82,83] |

| Mixing speed | High (i.e 200 rpm) |

↓dough stability; ↑ dough consistency; ↑peak time. |

↑ loaf volume; ↑ crumb texture. |

[53,84,104] |

| Low (i.e 63 rpm) |

↓ dough consistency; | ↓ loaf volume | [53,84,104] | |

| Dough temperature |

17°C | ↑ water absorption level; ↑ dough development time; ↑ dough consistency. |

↑ crumb texture; ↑ loaf volume. |

[84,98] |

| 30°C | ↓ dough consistency; ↓ water absorption time. |

↓ loaf volume | [84,98] | |

| Mixing time | overmixing | ↓ dough consistency; slack and sticky dough. |

↓ loaf volume | [95,101] |

| undermixing | ↑ dough consistency; ↓ leavening ability. |

↓ loaf volume | [95,101] | |

| ↑: increase; ↓: reduction | ||||

| Leavening agent |

Compounds produced |

Technological effect |

Sensory effect |

References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae spp.) |

CO2 Ethanol organic acid glycerol |

ethanol, succinic acid, glutathione alter the structure of the gluten network; ↑ softening effect on dough. |

Differences in the genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains play a major role in the change of the aroma profiles | [128,129] | |

| Sourdough (Saccharomyces cerevisiae spp. + Lactic acid bacteria) |

CO2 ; ethanol; organic acid; glycerol helps to produce enzymes such as maltase, invertase and zymase |

↓elastic and firm dough; ↑ bread-specific volume; ↓ crumb firmness over time; ↑dough expansion during fermentation. |

Bread aroma profiles and crumb structure are more distinctive, due to sour aromas produced, and preferred by sensory panels produced | [131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138] | |

| ↑: increase; ↓: reduction | |||||

| Tests | Advantages | Drawbacks | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature of | Empirical | Mixograph; | Easy; robust; capable, | The sample geometry is | [7,86] |

| method | Alveograph; | do not require technically | variable and not | ||

| Extensograph; | trained personnel | well-defined; | |||

| Farinograph; | the stress and strain states | ||||

| Mixolab; | are uncontrolled, complex | ||||

| Rheofermentograph | and non-uniform | ||||

| Fundamental | Small deformation dynamic shear | One type of deformation is | Complex instrumentation; | [7,86] | |

| oscillation; | applied, | expensive, time-consuming; | |||

| small and large deformation shear | scientific instruments; | difficult to maintain in an | |||

| creep and stress relaxation; | small number of samples | industrial environment and | |||

| large deformation extensional | required | require high levels of tech- | |||

| measurements; | nical skill | ||||

| flow viscometry | |||||

| Deformation | Small ampli- | Linear deformation, | Understanding molecular | Little relationship with | [7,86] |

| applied | tude oscilla- | analyzes the linear viscoelastic | interactions and micro- | end-use performance; | |

| tory shear | response by observing the strain | structure; | not being appropriate in | ||

| (SAOS) | and frequency dependence of the | material structural proper- | practical processing situa- | ||

| elastic modulus (g′) and viscous | ties under a relatively ex- | tions due to the rates at | |||

| modulus (g″) at small strains | tended range of conditions | which the test can be used | |||

| Large ampli- | Non linear deformation; | Provide structure of com- | Requiring complex compu- | [7,86,153] | |

| tude oscilla- | capillary flow; | plex food in real-time; | tation with data processing | ||

| tory shear | lubricated squeezing flow; | Differentiate different | software | ||

| (LAOS) | Stress relaxation, | types of wheat flours, | |||

| Stress growth, | Characterise the viscoelas- | ||||

| Creep and creep recovery, | tic properties of flour; | ||||

| Large amplitude oscillatory shear | dough is mainly exposed | ||||

| tests | to large deformations | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).