Submitted:

05 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Local Geology: G5 Supersuite

4. Materials and Methods

5. Results

5.1. Castelo Intrusive Complex

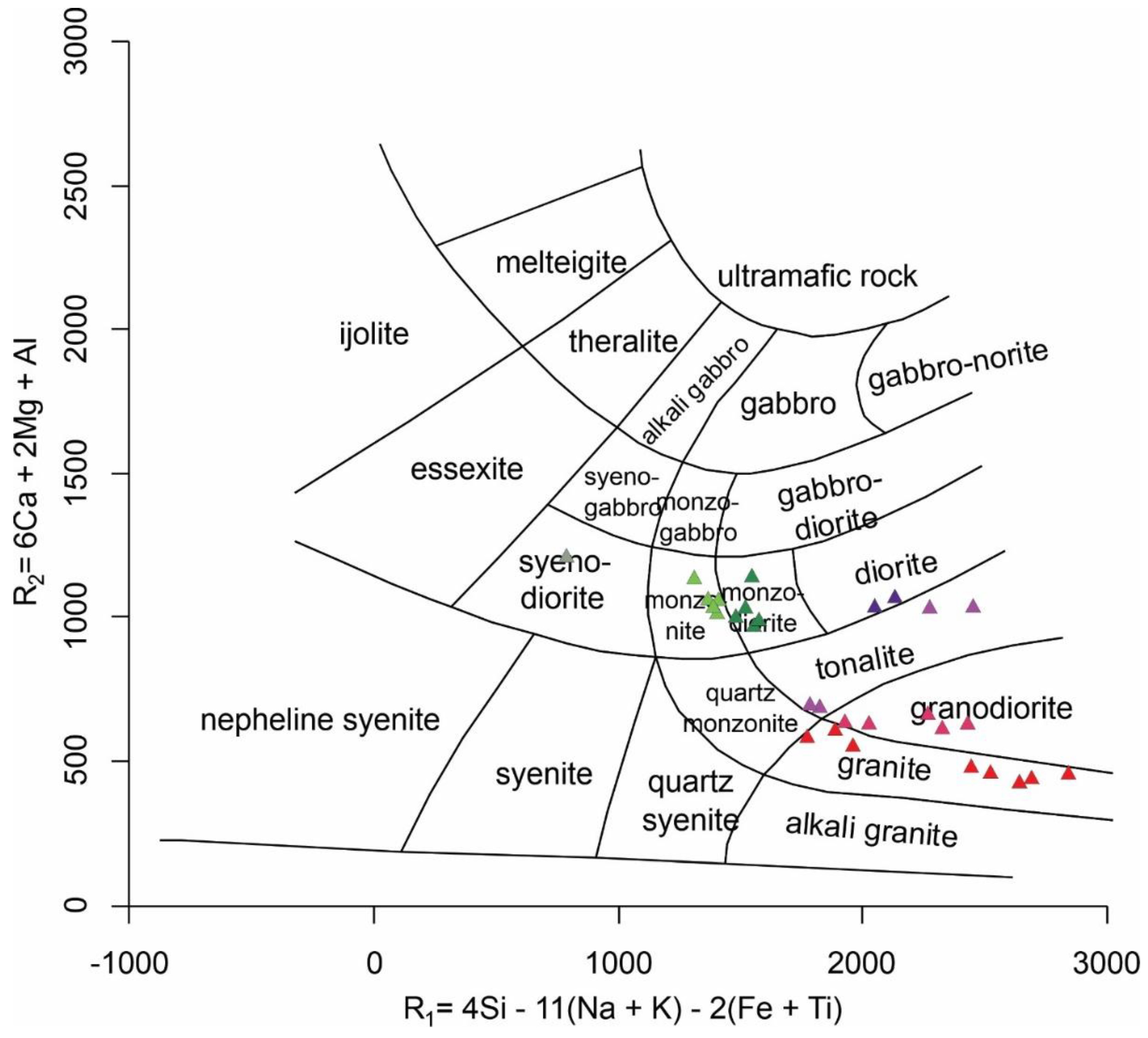

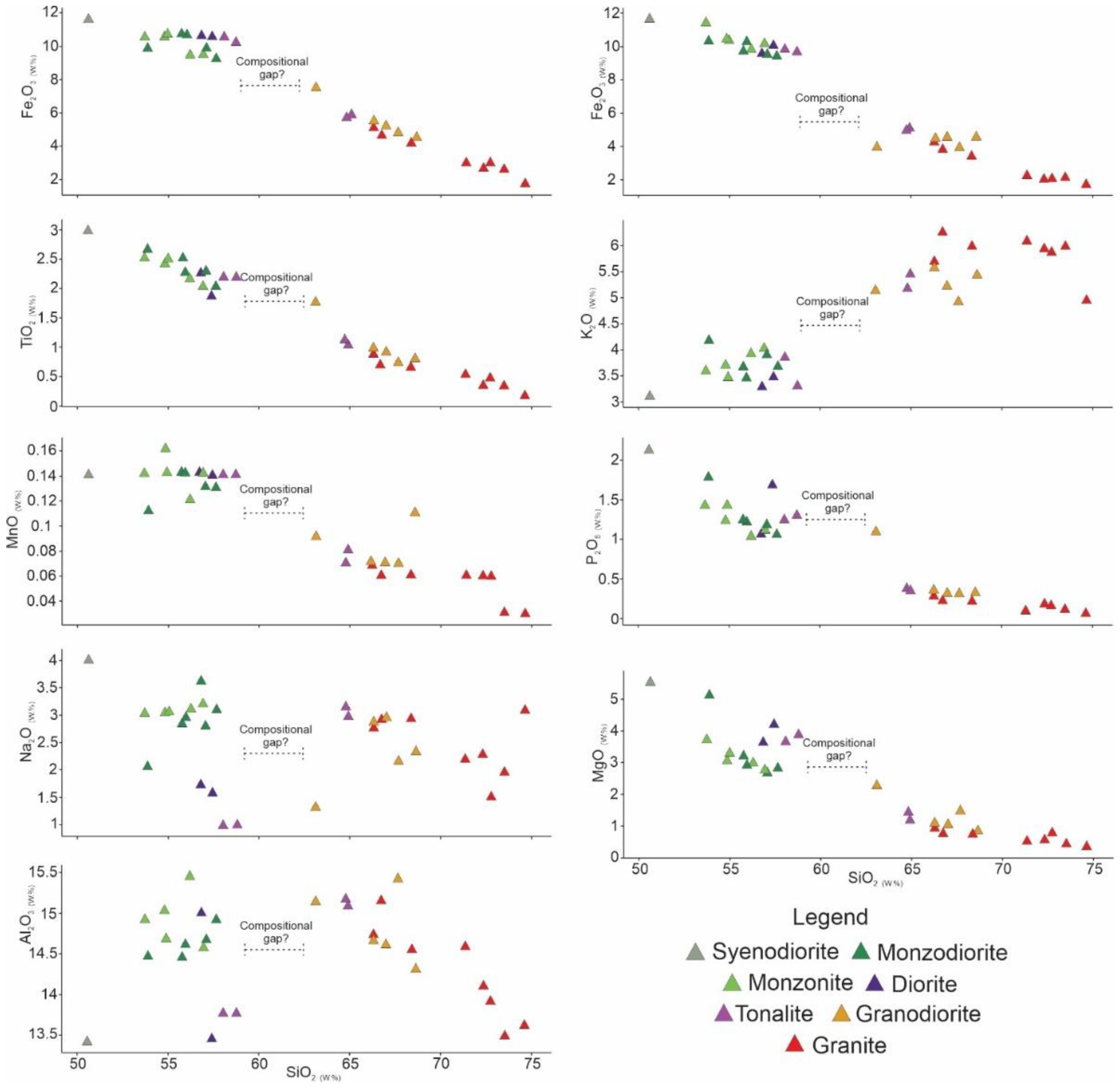

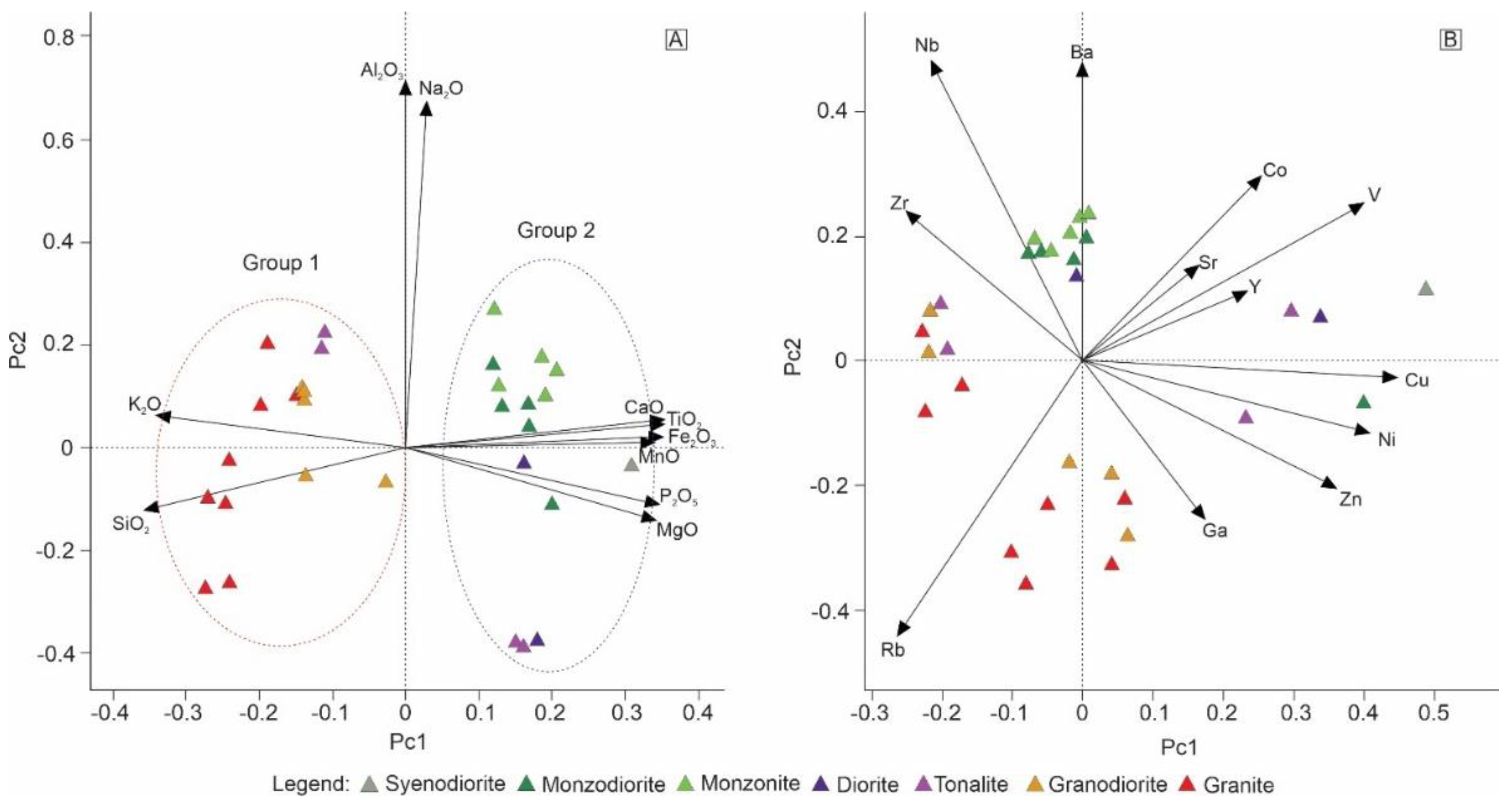

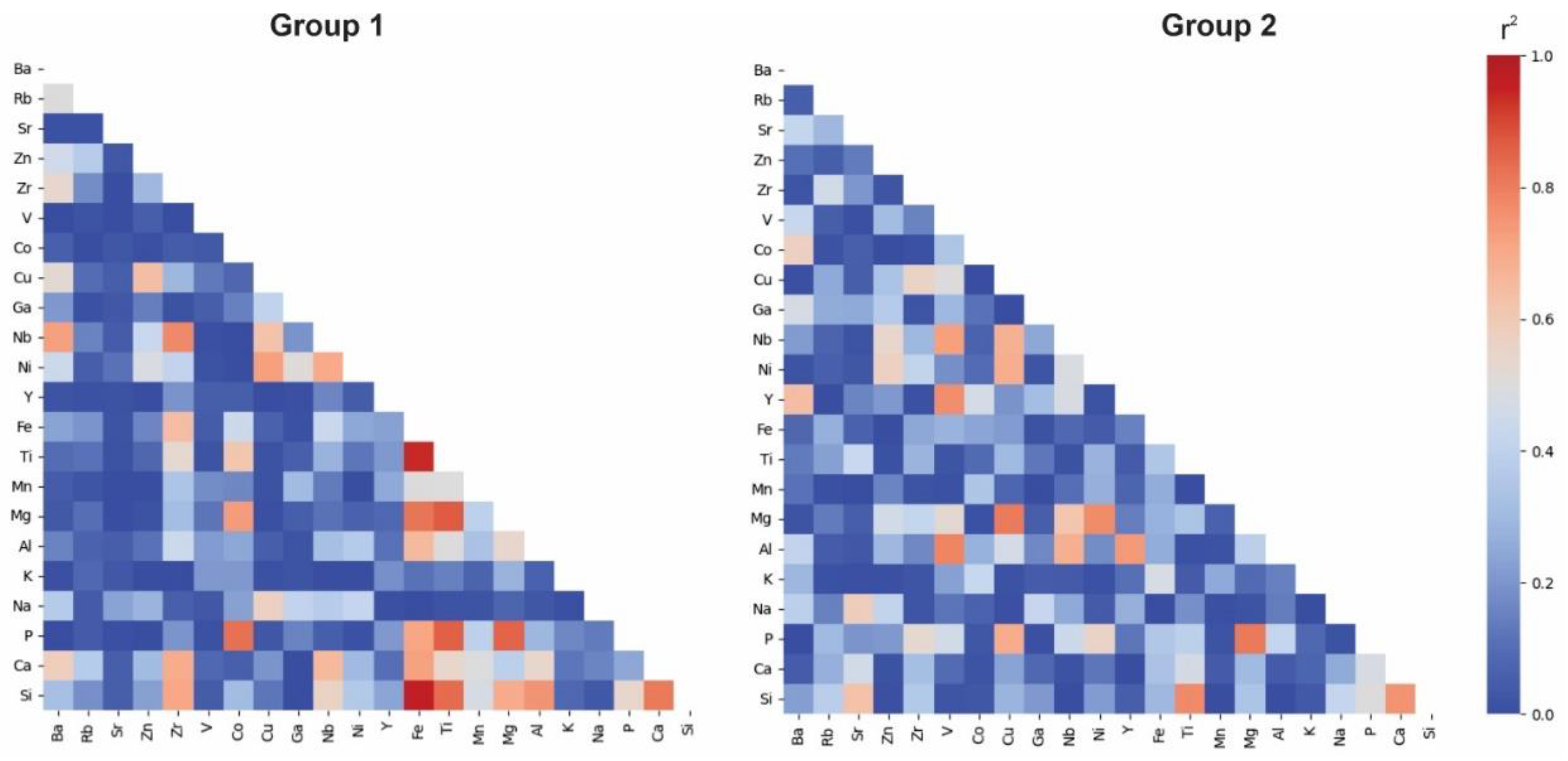

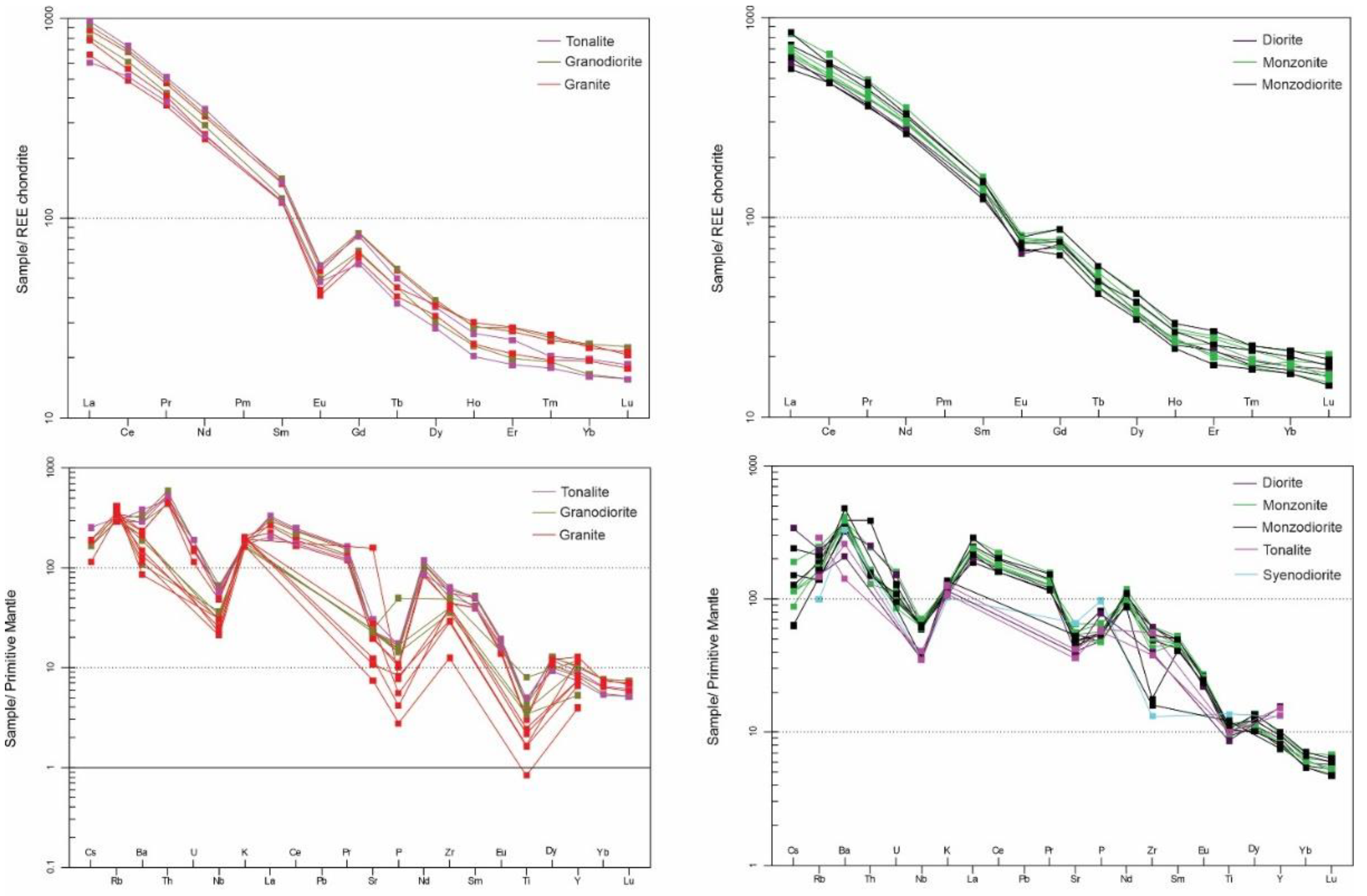

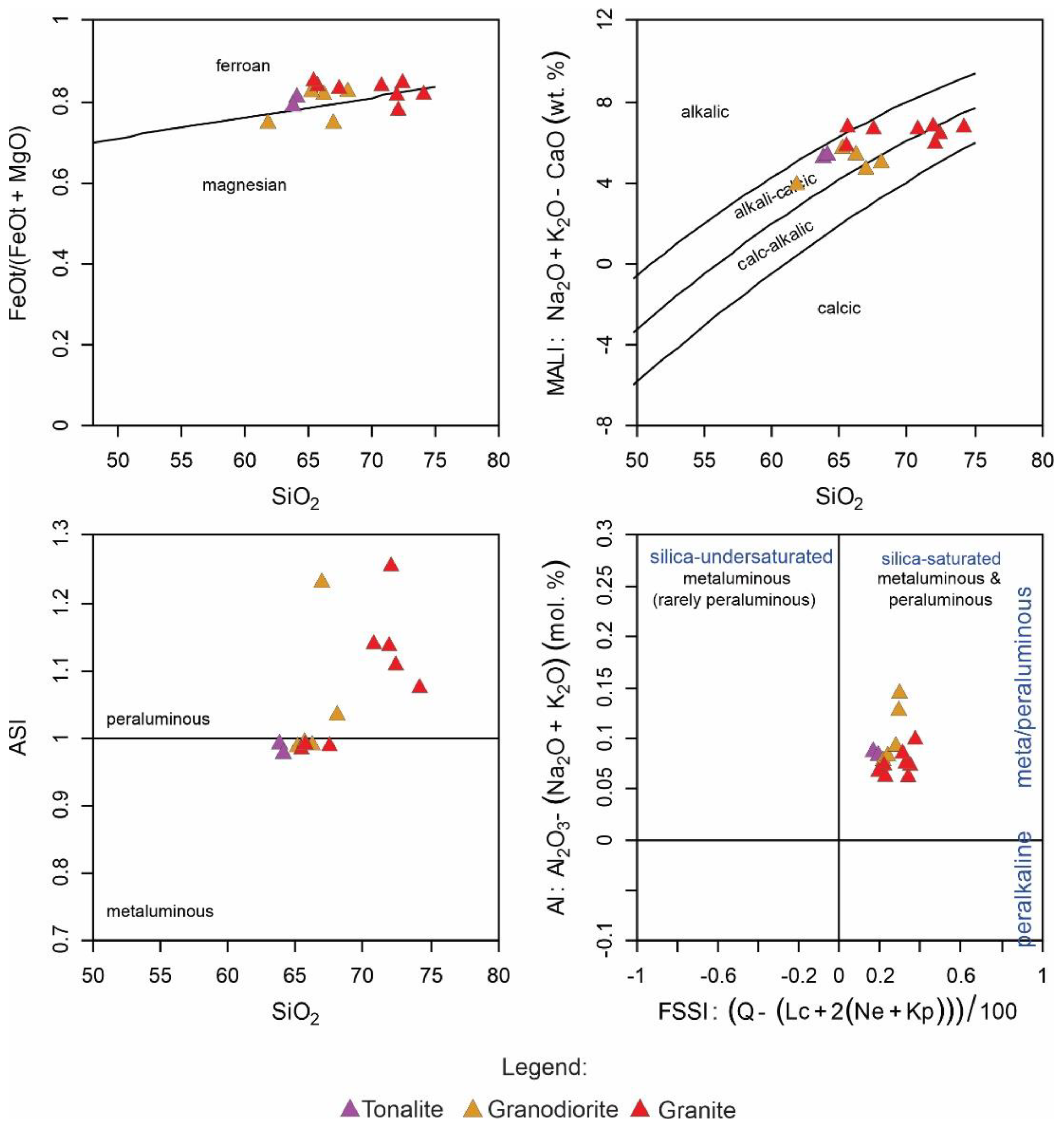

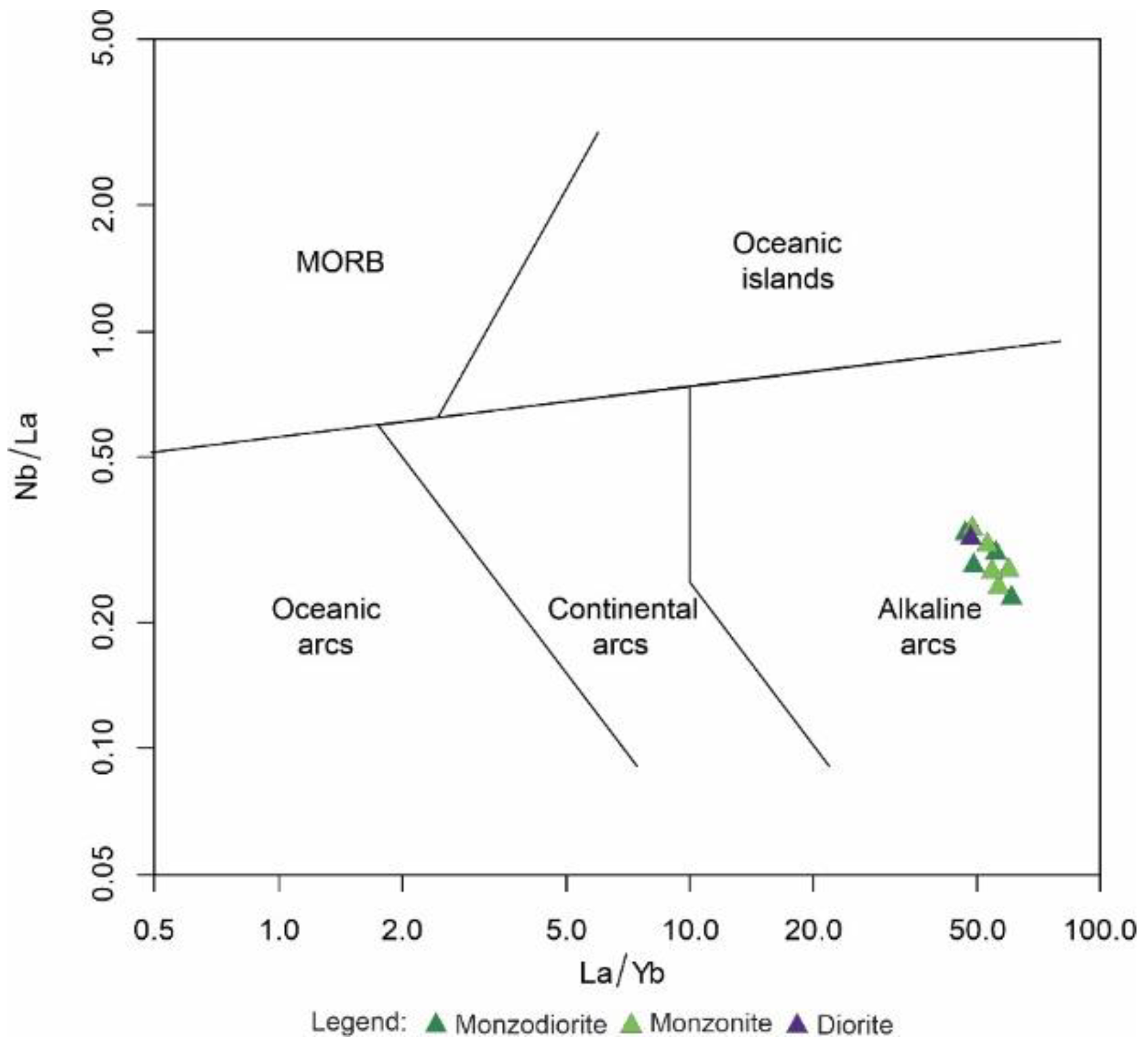

5.2. Lithogeochemical Characteristics

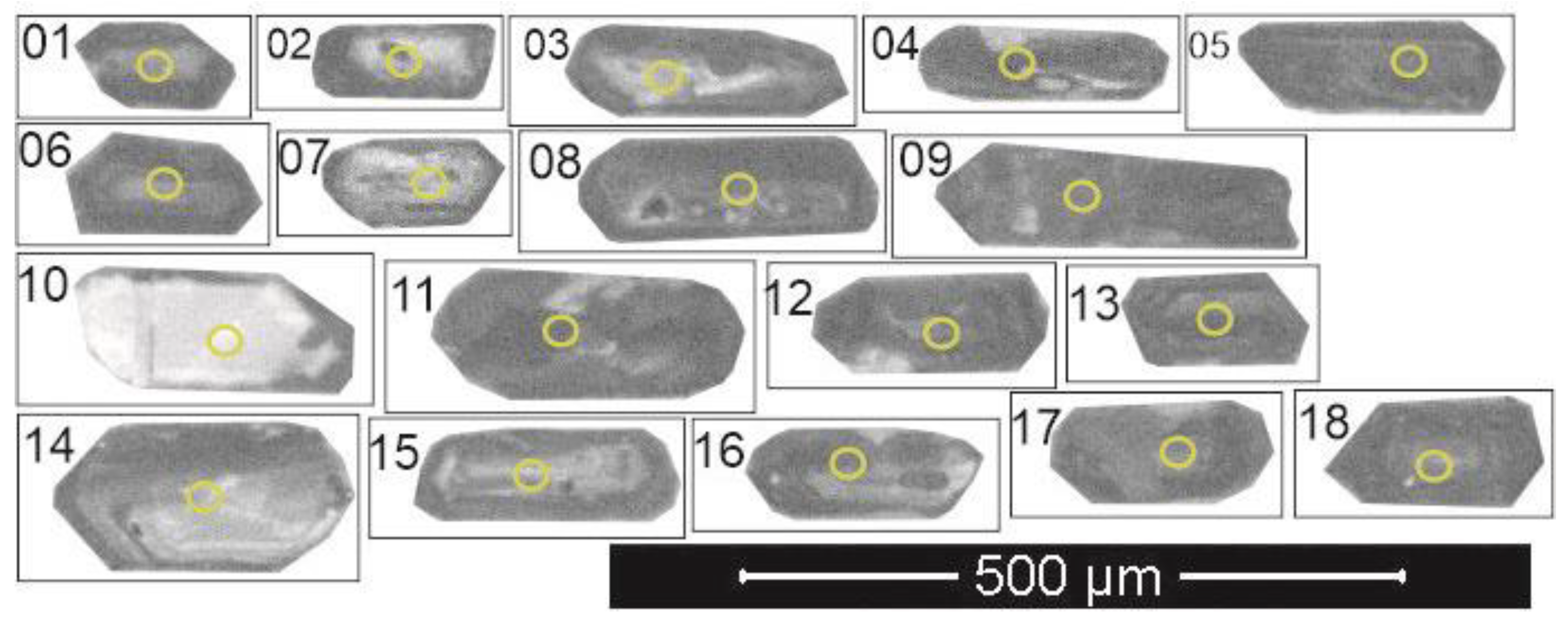

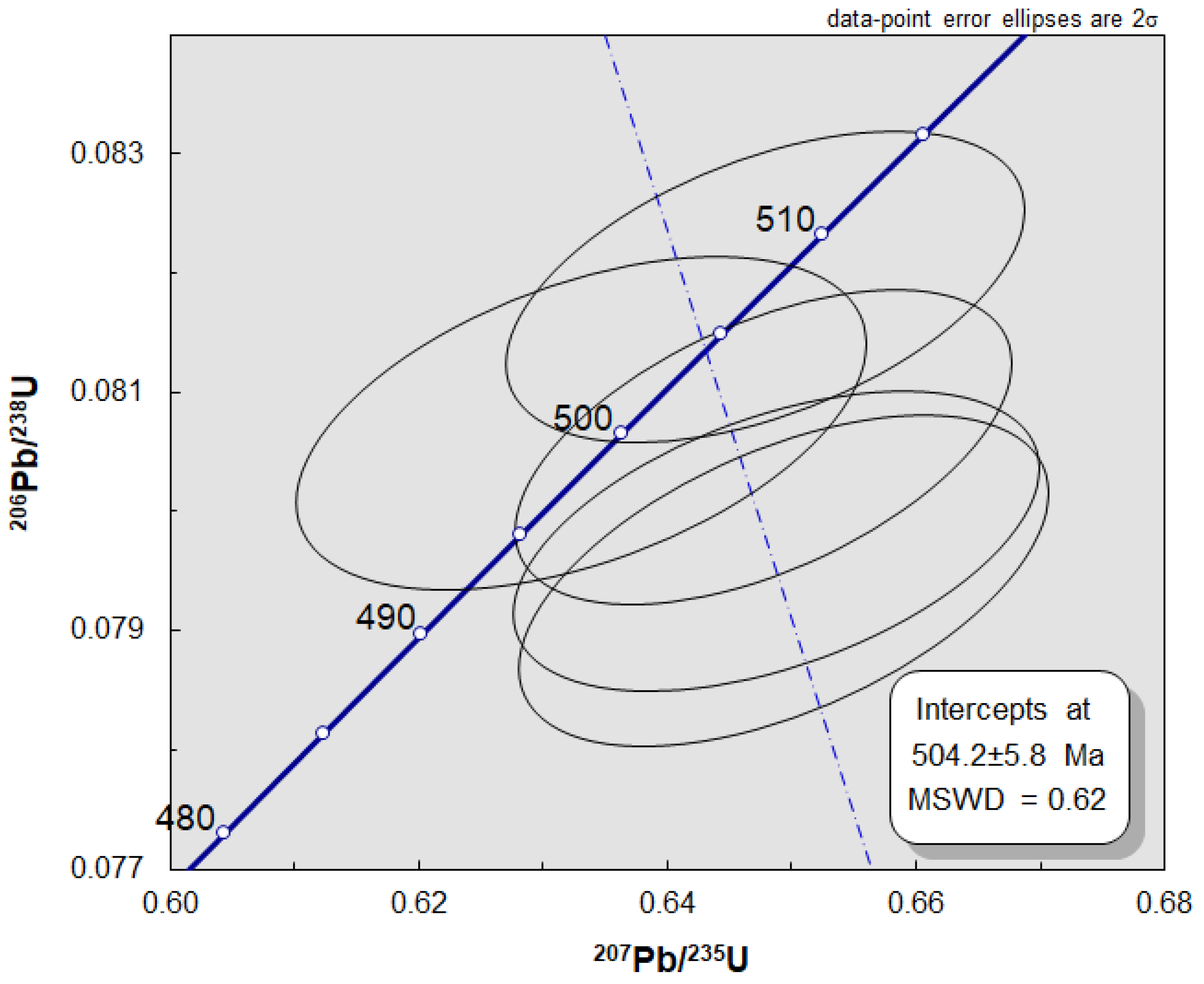

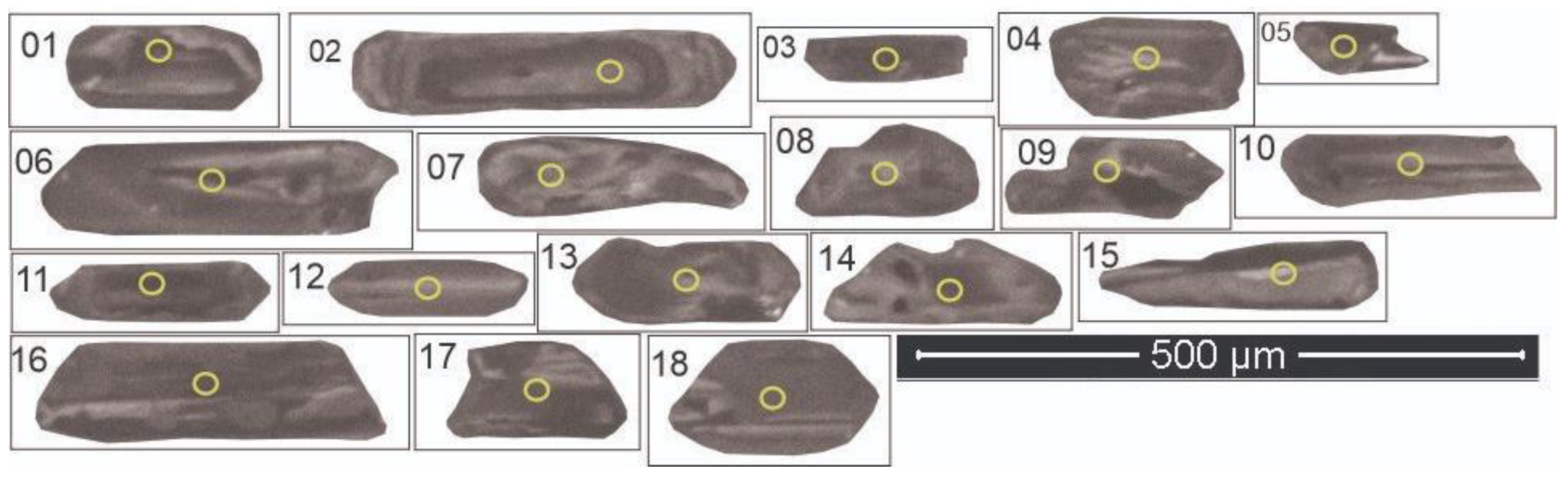

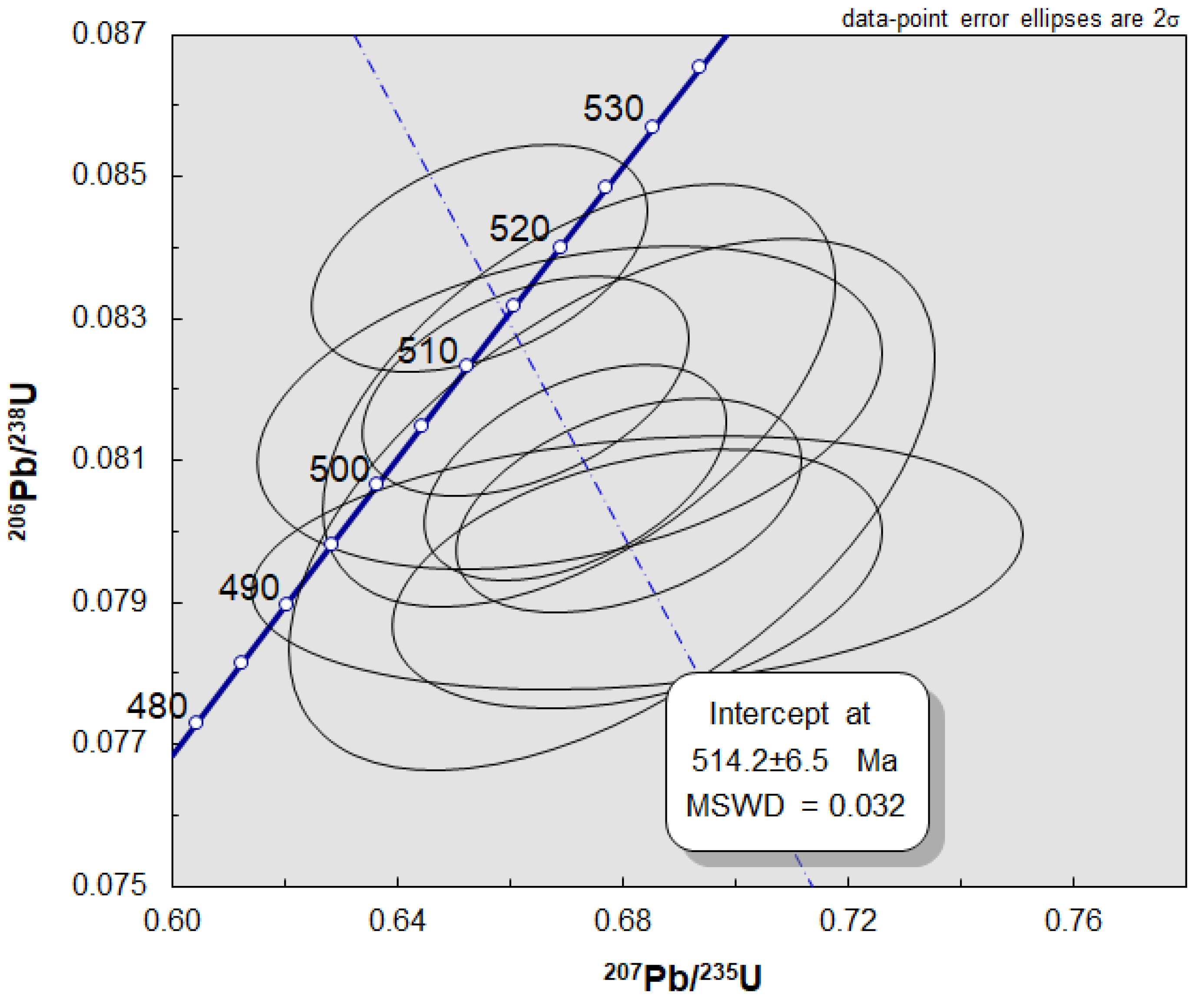

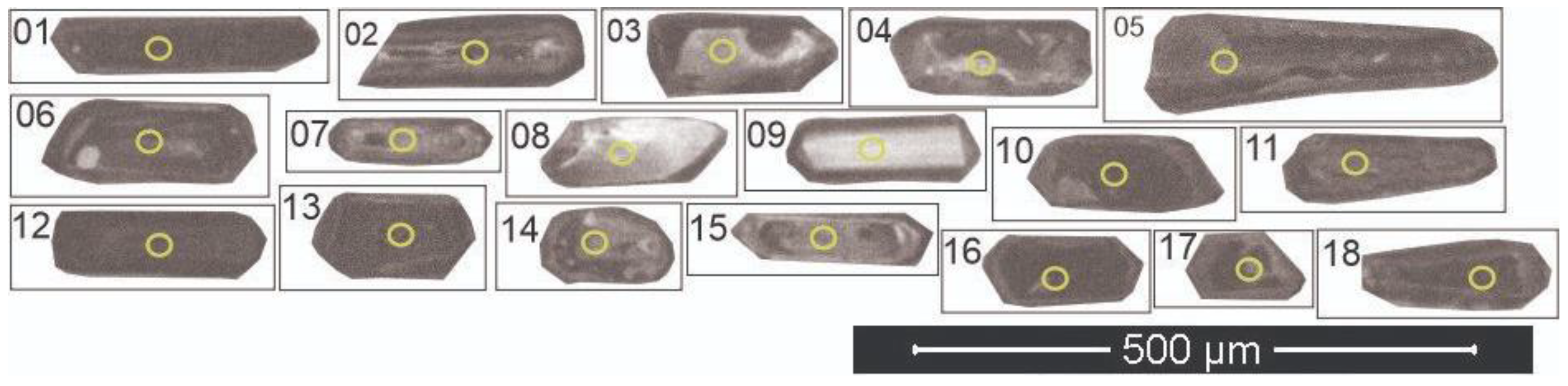

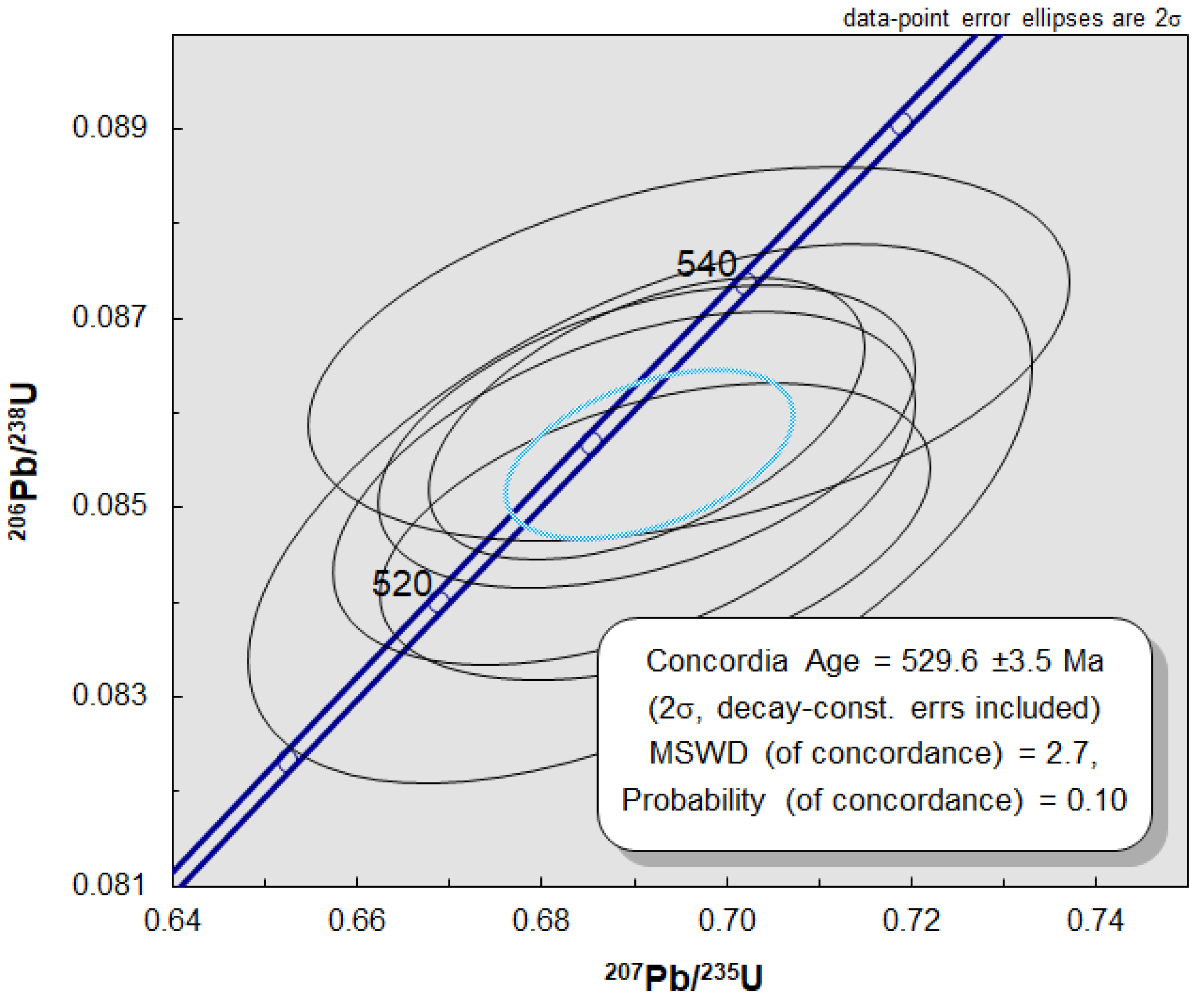

5.3. U-Pb Results

6. Discussions

6.1. Geological Units

6.2. The Mixing Process: Field and Petrographic Evidences

6.3. The Source Evidences

6.4. U-Pb and Lu-Hf Signatures

| SAMPLE | ROCK | U-Pb AGE | MSWD | 176Hf/177Hf | ƐHf (t) | TDM AGES (Ga) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGIL 06 A | Monzogranite | 499 ± 4 | 1.12 | 0.28142 to 0.28268 | +10.7 and -13.2 | 0.75 to 2.11 |

| FGIL 11 A | Monzogranite | 524 ± 5 | 1.4 | 0.28134 to 0.28275 | + 12.6 and – 22.0 | 0.64 to 2.60 |

| FGIL 17 A | Monzogranite | 521 ± 14 | 0.49 | 0.28142 to 0.28300 | +11.3 and -24.0 | 0.72 to 2.71 |

| FGIL 06 B | Qtz-Monzodiorite | 486 ± 12 | 0.43 | 0.28181 to 0.28281 | +12.57 and -22.7 | 0.65 to 2.64 |

| FGIL 06 C | Hololeucocratic dyke | 432 ± 32 | 1.17 | 0.28155 to 0.28281 | +12.7 and -24.0 | 0.64 to 2.71 |

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, S.G., Wang, M.J., Wang, C., Niu, Y.L., 2015. Magmatism during a continental collision, subduction, exhumation and mountain collapse in collisional Orogenic belts and continental net growth: A perspective. Sci. China-Earth Sci. 58, 1284–1304. [CrossRef]

- Bonin, B. 2004. Do coeval mafic and felsic magmas in post-collisional to within-plate regimes necessarily. Imply two contrasting, mantle and crustal, sources? A review. Lithos v.78, p.1 – 24. [CrossRef]

- Liégeois, J.P. 1998. Some words on the post-collisional magmatism – Preface to Special Edition on Post-collisional Magmatism. Lithos, 45: xv-xvii.

- Sklyarov, E.V., Federovskii, V.S. 2006. Magma Mingling: Tectonic and Geodynamic Implications. Geotectonics, Vol. 40, No. 2, pp. 120–134. [CrossRef]

- Perugini, D., Petrelli, M., Poli, G., De Campos, C., Dingwell, D.B., 2010. Recent phlegrean field eruptions' time-scales are inferred from applying a “diffusive fractionation” model of trace elements. Bulletin of Volcanology 72, 431–447.

- Sami, M., Ntaflos, T., Farahat, E.S., Mohamed, H.A., Hauzenberger, C., Ahmed, A.F., 2018. Petrogenesis and geodynamic implications of Ediacaran highly fractionated A type granitoids in the north Arabian-Nubian Shield (Egypt): constraints from whole rock geochemistry and Sr-Nd isotopes. Lithos 304 (307), 329–346. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Zhao, J., Zhang, C., Yu, S., Ye, X., Liu, X. 2022. Paleozoic post-collisional magmatism and high-temperature granulite-facies metamorphism coupling with lithospheric delamination of the East Kunlun Orogenic Belt, NW China. Geoscience Frontiers 13, 101271. [CrossRef]

- Perugini, D., De Campos, C.P., Dingwell, D.B., Dorfman, A., 2013. Relaxation of concentration variance: a new tool to measure chemical element mobility during mixing of magmas. Chemical Geology 335, 8–23. [CrossRef]

- De Campos, C.P. 2015. Chaotic flow patterns from a deep plutonic environment: A case study on natural magma mixing. Pure Applied Geophysics. 172, 1815–1833. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00024-014-0940-6. [CrossRef]

- Gagnevin, D., Daly, J.S., Kronz, A., 2010. Zircon texture and chemical composition as a guide to magmatic processes and mixing in a granitic environment and coeval volcanic system. Contribuitions Mineral Petrology, 159:579–596. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H., Wu, F.Y., Wilde, S.A., Xie, L.W., Yang, Y.H., Liu, X.M. 2007. Tracing magma mixing in granite genesis: in situ U–Pb dating and Hf-isotope analysis of zircons. Contribuitions Mineral Petrology, 153:177–190. [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Campos, C.P.C., Noce, C., Silva, L.C., Novo, T., Roncato, J., Medeiros, S., Castaneda, C., Queiroga, G., Dantas, E., Dussin, I., Alkmim, F., 2011. Late Neoproterozoic-Cambrian granitic magmatism in the Aracuai Orogeny (Brazil), the Eastern Brazilian Pegmatite Province and related mineral resources. In: Sial, A.N., Bettencourt, J.S., De Campos, C.P., Ferreira, V.P. (Eds.), Granite-Related Ore Deposits. Geological Society, Special Publications, London, pp. 25–51.

- Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Deluca, C., Araujo, C., Gradim, C., Lana, C., Dussin, I., Silva, L.C., Babinski, M., 2020. O Orógeno Araçuaí à luz da geocronologia: um tributo a Umberto Cordani. In: Bartorelli, A., Teixeira, W., Brito Neves, B.B. (Eds.), Geocronologia e Evolução Tectônica do Continente Sul-Americano: a contribuição de Umberto Giuseppe Cordani. Solarias Edições Culturais, São Paulo, p. 728p.

- De Campos, C.P., Medeiros, S.R., Mendes, J.C., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Dussin, I., Ludka, I.P., Dantas, E.L., 2016. Cambro-Ordovician magmatism in the Aracuai Belt (SE Brazil): Snapshots from a post-collisional event. Journal of South American Earth Science. 68, 248–268. [CrossRef]

- Macedo, I.M.L., Geraldes, M.C.G., Marques, R.A., Melo, M.G., Tavares, A.D., Martins, M.V.A., Oliveira, H.C., Rodrigues, R.D. 2022. New clues for magma-mixing processes using petrological and geochronological evidence from the Castelo Intrusive Complex, Araçuaí Orogeny (SE Brazil). Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 115, 103758. [CrossRef]

- Alkmin, F.F, Marshak, S, Pedrosa-Soares, A., Peres, G., Cruz, S.C.P, Whittington, A. 2006. Kinematic evolution of the Araçuaí–West Congo Orogeny in Brazil and Africa: Nutcracker tectonics during the Neoproterozoic assembly of Gondwana. Precambrian Research, 149:43 – 63.

- Alkmin, F. F, Kuchenbecker, M, Reis, H. L. S, Pedrosa-Soares, A. C, 2017. The Araçuaí belt.In: Heilbron, M., Cordani, U.G, Alkmim F.F. (Eds.), São Francisco Craton, Eastern Brazil. Regional Geology Reviews, Springer International Publishing Co., pp. 255–276.

- Tedeschi, M., Novo, T., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Dussin, I., Tassinari, T., Silva, L.C., Goncalves, L., Alkmim, F.F., Lana, C., Figueiredo, C., Dantas, E., Medeiros, S., De Campos, C., Corrales, F., Heilbron, M., 2016. The Ediacaran Rio Doce magmatic arc revisited (Aracuai- Ribeira Orogenyic system, SE Brazil). Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 68, 167–186.

- Almeida, F.F.M., Brito Neves, B.B., Carneiro, C.D.R. 2000. The origin and evolution of the South American Plataform. Earth Science Reviews., 50:77-111.

- Heilbron, M.L., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Campos Neto, M.C., Silva, L.C., Trouw, R., Janasi, V.A., 2004. Brasiliano Orogenys in Southeast and South Brazil. Journal Virtual Explorer 17, Paper 4.

- Degler, R., Pedrosa-Soares, A., Novo, T., Tedeschi, M., Silva, L.C., Dussin, I., Lana, C., 2018. Rhyacian-Orosirian isotopic records from the basement of the Aracuai-Ribeira Orogenyic system (SE Brazil): Links in the Congo-Sao Francisco palaeocontinent. Precambrian Research. [CrossRef]

- Corrales F.F.P., Dussin I.A., Heilbron M., Bruno H., Bersan S.A., Valeriano C.M., Pedrosa- Soares A.C., Tedeschi M. 2020. Coeval high Ba-Sr arc-related and OIB Neoproterozoic rocks linking pre-collisional magmatism of the Ribeira and Aracuai Orogenic belts, SE-Brazil, Precambrian Research. [CrossRef]

- Heilbron, M., Valeriano, C.M., Peixoto, C., Tupinambá, M., Neubauer, F., Dussin, I., Corrales, F., Bruno, H., Lobato, M., Almeida, J.C.A., Silva, L.G.E., 2020. Neoproterozoic magmatic arc systems of the central Ribeira belt, SE-Brazil, in the context of the West-Gondwana pre-collisional history: a review. Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 103, 102710 . [CrossRef]

- Santiago, R., Caxito, F. A., Pedrosa-Soares, A., Neves, M.A., Calegari, S.S., Lana, C. 2022. Detrital zircon U–Pb and Lu–Hf constraints on the age, provenance and tectonic setting of arc-related high-grade units of the Araçuaí and Ribeira Orogenys (SE Brazil) transition zone. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 116, 103861. [CrossRef]

- Gradim, C., Roncato, J., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Cordani, U., Dussin, I., Alkmim, F.F., Queiroga, G., Jacobsohn, T., Silva, L.C., Babinski, M., 2014. The hot back-arc zone of the Aracuai Orogeny, Eastern Brazil: From sedimentation to granite generation. Brazilian Journal of Geology. 44, 155–180. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L., Farina, F., Lana, C., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Alkmim, F., Nalini Jr., H.A., 2014. New U-Pb ages and lithochemical attributes of the Ediacaran Rio Doce magmatic arc, Araçuaí confined Orogeny, southeastern Brazil Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 52, 129–148. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L., Alkmim, F.F., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Dussin, I.A., Valeriano, C.M., Lana, C., Tedeschi, M., 2016. Granites of the intracontinental termination of a magmatic arc: an example from the Ediacaran Araçuaí Orogeny, southeastern Brazil. Gondwana Research. 36, 439–458. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L., Alkmim, F.F., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Gonçalves, C.C., Vieira, V., 2018. From the plutonic root to the volcanic roof of a continental magmatic arc: a review of the Neoproterozoic Araçuaí Orogeny, southeastern Brazil. International Journal Earth Science. 107, 337–358. [CrossRef]

- Richter, F., Lana, C., Steven, G., Buick, I., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Alkmim, F.F., Cutts, K., 2016. Sedimentation, metamorphism and granite generation in a back-arc region: Records from the Ediacaran Nova Venecia Complex (Aracuai Orogeny, Southeastern Brazil). Precambrian Research. 272, 78–100.

- Santiago, R., Caxito, F.A., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Neves, M., Dantas, E.L., 2020. Tonian Island Arc Remnants in the Northern Ribeira Orogeny of Western Gondwana: the Caxixe Batholith (Espírito Santo, SE Brazil). Precambrian Research. p. 105944.

- Soares, C.C.V., Queiroga, G., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Gouvêa, L.P., Valeriano, C.M., Melo, M.G., Marques, R.A., Freitas, R.D.A., 2020. The Ediacaran Rio Doce magmatic arc in the Araçuaí – Ribeira boundary sector, southeast Brazil: lithochemistry and isotopic (Sm–Nd and Sr) signatures. Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 102880 . [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, E., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Alkmim, F.F., Dussin, I.A., 2015. A suture-related accretionary wedge formed in the Neoproterozoic Araçuaí Orogeny (SE Brazil) during Western Gondwanaland assembly. Gondwana Research. 27, 878–896. [CrossRef]

- Santiago, R., Caxito, F.A., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Neves, M., Dantas, E.L., Calegari, S.S., Lana, C. 2023. Records of the accretionary, collisional and post-collisional evolution of western Gondwana in the high grade core of the Araçuaí-Ribeira Orogenyic system, SE Brazil. Precambrian Research. 397, 107191. [CrossRef]

- Melo, M.G., Stevens, G., Lana, C., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Frei, D., Alkmim, F.F., Alkmin, L. A., 2017a. Two cryptic anatectic events within a syn-collisional granitoid from the Araçuaí Orogeny (southeastern Brazil): evidence from the polymetamorphic Carlos Chagas batholith. Lithos 277, 51–71. [CrossRef]

- Melo, M.G., Lana, C., Stevens, G., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Gerdes, A., Alkmin, L.A., Nalini Jr., H.A., Alkmim, F.F., 2017b. Assessing the isotopic evolution of S-type granites of the Carlos Chagas Batholith, SE Brazil: clues from U–Pb, Hf isotopes, Ti geothermometry and trace element composition of zircon. Lithos 284–285, 730–750. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, P., Pedrosa-Soares, A., Medeiros-Junior, E., Fonte-Boa, T., Araújo, C., Dussin, I., Queiroga, G., Lana, C., 2018. A-type Medina batholith and post-collisional anatexis in the Araçuaí Orogeny (SE Brazil). Lithos 320–321, 515–536. [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann-Leonardos, C.M., Medeiros, S.R., Mendes, J.C., Ludka, I.P., Moura, J.C., 2002. The architecture of late Orogenyic plutons in the araçuaí-ribeira folded belt, southeast Brazil. Gondwana Res. 5 (2), 381–399. [CrossRef]

- De Campos, C.P., Mendes, J.C., Ludka, I.P., Medeiros, S.R., Moura, J.C., Wallfass, C., 2004. A review of the Brazilian magmatism in southern Espirito Santo, Brazil, with emphasis on postcollisional magmatism. Journal Virtual Explorer 17, 1–35.

- Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Noce, C.M., Wiedemann, C.M., Pinto, C.P., 2001. The Aracuai-West Congo Orogeny in Brazil: An overview of a confined Orogeny formed during Gondwanland assembly. Precambrian Research. 110, 307–323.

- Medeiros, S.R., Wiedemann, C.M., Vriend, S., 2001. Evidence of mingling between contrasting magmas in a deep plutonic environment: the example of Várzea Alegre in the Panafrican/Brasiliano Mobile Belt in Brazil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 73, 99–119.

- Mendes, J.C., Medeiros, S.R., McReath, I., De Campos, C.M.P., 2005. Cambro-ordovician magmatism in SE Brazil: U-Pb and Rb-Sr ages, combined with Sr and Nd isotopic data of charnockitic rocks from the Várzea Alegre complex. Gondwana Research. 8, 337–345. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.C., De Campos, C.M.P., 2012. Norite and charnockites from the Venda Nova Pluton, SE Brazil: intensive parameters and some petrogenetic constraints. Geosciences Frontiers. 3, 789–800. [CrossRef]

- Bayer, P., Schimidt-Thomé, R., Weber-Diefenbach, K., Horn, H.A. Complex concentric granitoid intrusions in the coastal mobile belt, Espírito Santo, Brazil: The Santa Angélica Pluton—An example. Geol. Rundsch. 1987, 76, 357–371. [CrossRef]

- Schimidt-Thomé, R., Weber-Diefenbach, H., 1987. Evidence for froze-in magma mixing in Brasiliano calc-alkaline intrusions: the Santa Angélica pluton, southern Espírito Santo, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Geociencias 17 (4), 498–506.

- Aranda, R.O., Chaves, A.O., Medeiros Júnior, E.B., Venturini Junior, R., 2020. Petrology of the Afonso cláudio intrusive complex: new insights for the cambro-ordovician post-collisional magmatism in the araçuaí-west Congo Orogeny, southeast Brazil. Journal of South American Earth Science. 98, 102465 . [CrossRef]

- Araujo, C., Pedrosa-Soaresa, A., Lana, C., Dussin, I., Queiroga, G., Serrano, P., Medeiros- Junior, E., 2020. Zircon in emplacement borders of post-collisional plutons compared to country rocks: A study on morphology, internal texture, U Th–Pb geochronology and Hf isotopes (Aracuai Orogeny. SE Brazil). Lithos, 352–353, 105252. [CrossRef]

- Duffles Teixeira, P.A., Fernandes, C.M., Mendes, J.C., Medeiros, S.R., Rocha, I.S.A., 2020. U-Pb LA-ICP-MS and geochemical data of the Alto Chapéu Pluton: contributions on bimodal post-collisional magmatism in the Araçuaí belt (SE Brazil). Journal of South American Earth Science, 103, 102724. [CrossRef]

- Melo, M.G., Lana, C., Stevens, G., Hartwig, M.E., Pimenta, M.S., 2020. Deciphering the source of multiple U-Pb ages and complex Hf isotope composition in zircon from post-collisional charnockite-granite associations from the Araçuaí Orogeny (southeastern Brazil). Journal of South American Earth Science, 103, 102792. [CrossRef]

- Bellon, U.D., Souza-Junior, G.F., Temporim, F.A., D’agrella-Filho, M.S., Trindade, R.I.F. 2022. U-Pb geochronology of a reversely zoned pluton: Records of pre-to-post colisional magmatismo of the Araçuaí belt (SE-Brazil)?. Journal of South American Earth Science, V 119 (104045).

- Potratz, G.L., Geraldes, M.C., Medeiros-Junior, E.B., Temporim, F.A., Martins, M.V.A. 2022. A Juvenile Component in the Pre- and Post-Collisional Magmatism in the Transition Zone between the Araçuaí and Ribeira Orogenys (SE Brazil). Minerals, 12: 1378.

- Noce C.M., Teixeira W., Quéméneur J.J.G., Martins V.T.S., Bolzachini, E. 2000. Isotopic signatures of Paleoproterozoic granitoids from southern São Francisco Craton, NE Brazil, and implications for the evolution of the Transamazonian Orogeny. Journal of South American Earth Science, 13: 225-239.

- Martins, V.T.S., Teixeira, W., Noce, C.M., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., 2004. Sr and Nd characteristics of brasiliano/pan-african granitoid plutons of the Araçuaí Orogeny, southeastern Brazil: tectonic implications. Gondwana Res. 7, 75–89. [CrossRef]

- Sollner, H.S., Lammerer, B., Wiedemann-Leonardos, C., 2000. Dating the Araçuaí- ribeira mobile belt of Brazil. In: Sonderheft, Zeitschrift (Ed.), Angwandte Geologie, SH1, pp. 245–255.

- Petitgirard, S., Vauchez, A., Egydio-Silva, M., Bruguier, O., Camps, P., Moni´e, P., Babinsky, M., Mondou, M., 2009. Conflicting structural and geochronological data from the Ibiturana quartz-syenite (SE Brazil): effect of protracted “hot” Orogeny and slow cooling rate? Tectonophysics 477, 174–196. [CrossRef]

- Baltazar, O.F., Zucchetti, M., Oliveira, S.A.M., Scandolara, J., Silva, L.C., 2010. Geologia das Folhas São Gabriel Da Palha e Linhares. Programa Geologia do Brasil. CPRM–Serviço Geológico do Brasil, Belo Horizonte.

- Ulbrich, H. H. G. J., Vlach, S. R. F., Janasi, V. A. 2001 O mapeamento faciológico em rochas ígneas plutônicas. Revista Brasileira de Geociências, v. 31, p. 163-172.

- Jackson, S.E., Pearson, N.J., Griffin, W.L., Belousova, E.A., 2004. Applying laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry to in situ U-Pb zircon geochronology. Chem. Geol. 211 (1–2), 47–69. [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.I., Almeida, B.S., Cardoso, L.M.C., Santos, A.C., Appi, C. Bertotti, A.L., Chemale, F., Tavares Jr, A.D., Martons, M.V.A., Geraldes, M.C. 2019 Isotopic Composition of Lu, Hf, and Yb in GJ-1, 91500 and Mud Tank reference materials measured by LA-ICP-MS: Application of the Lu-Hf geochronology in zircon. Journal of Sedimentary Environments 4 (2): 220-248.

- Streckeisen, A., 1976. To each plutonic rock its proper name. Earth Science Reviews. 12, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Whitney, D.L., Evans, B.W., 2010. Abbreviations for names of rock-forming minerals. Am. Mineral. 95, 185–187. [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, J.D.C., 2013. Caracterização petrográfica e litogeoquímica do Batólito Forno Grande, Castelo, Espírito Santo. Graduation Work Final – Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Alegre, p. 96.

- Meyer, A.P., 2017. Geologia e geoquímica da porção sul do Maciço Castelo-ES. PhD Thesis. Universidade Estadual Paulista, Instituto de Geociências e Ciências Exatas Rio Claro, 143 f.

- De La Roche, H., Leterrier, J., Grande Claude, P., Marchal, M., 1980. A volcanic and plutonics rocks classification using R1–R2 diagrams and major element analyses – Its relationships and current nomenclature. Chemical Geology. 29, 183–221.

- Boynton, W.V., 1984. Cosmochemistry of the rare earth elements, meteorite studies. In: Henderson, P. (Ed.), Rare Earth Element Geochemistry, vol. 1. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 63–114.

- Sun, S.S., McDonough, W.F., 1989. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: implications for mantle composition and processes. In: Saunders, A.D., Norry, M. (Eds.), Magmatism in Ocean Basins, vol. 42. Geological Society of London Special Publications, pp. 313–345. [CrossRef]

- Frost, B.R., Frost, C.D., 2008. A Geochemical classification for feldspathic igneous rocks. J. Petrol. 49, 1955–1969. [CrossRef]

- Hollocher, K., Robinson, P., Walsh, E., and Roberts, D. 2012, Geochemistry of amphibolite-facies volcanic and gabbros of the Støren nappe in extensions west and southwest of Trondheim, Western Gneiss Region, Norway: A key to correlations and paleotectonic settings: American Journal of Science, v. 312, p. 357–416. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. N. DA (Org). 1992. Programa levantamentos geológicos básicos do Brasil. Cachoeiro de Itapemirim. Folha SF.24-V-A-V. Estado do Espírito Santo. Escala 1:100.000., DNPM/CPRM.

- Vieira, V.S., Menezes, R.G., Orgs, 2015. Geologia e Recursos Minerais do Estado do Estado do Espírito Santo: texto explicativo do mapa geológico e de recursos minerais, escala 1:400.000. In: Programa Geologia Do Brasil, CPRM - Serviço Geológico Do Brasil, Belo Horizonte.

- Zhang, J., Wang, T., Castro, A., Zhang, L., Shi, X., Thong, Y., Zhang, Z., Guo, L., Yang, Q., Iaccheri, L, M. 2016. Multiple Mixing and Hybridization from Magma Source to Final Emplacement in the Permian Yamatu Pluton, the Northern Alxa Block, China. Journal of Petrology, 2016, Vol. 57, No. 5, 933–980. [CrossRef]

- Grogan, S.E., Reavy, R.J. 2002. Disequilibrium textures in the Leinster Granite Complex, SE Ireland: evidence for acid-acid magma mixing. Mineralogical Magazine, Vol. 66(6), pp. 929–939. [CrossRef]

- Alves, A., Janasi, V.A., Pereira, G.S., Prado, F.A., Munoz, P.R.M. 2021. Unravelling the hidden evidences of magma mixing processes via combination of in situ Sr isotopes and trace elements analyses on plagioclase crystals. Lithos, 404-405 (106435). [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.S., Conceição, H., Soares, H.S., Fernandes, D.M., Rosa, M.L.S. 2022. Magmatic processes recorded in plagioclase crystals of the Rio Jacaré Batholith, Sergipano Orogenyic System, Northeast Brazil. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 118 (103942).

- Hibbard, M.J., 1995. Petrography to Petrogenesis. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, p. 587p.

- Vernon, R. H. 1983. Restitc, xenoliths and microgranitoid enclaves in granites. Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Walts, 116: 77-103.

- Barbarin, B., 2005. Mafic magmatic enclaves and mafic rocks associated with some granitoids of the central Sierra Nevada batholith, California: nature, origin, and relations with the hosts. Lithos 80, 155–177. [CrossRef]

- Barbarin, B., Didier, J., 1992. Genesis and evolution of mafic microgranular enclaves through various types of interaction between coexisting felsic and mafic magmas. Earth Environments Science Transact. Royal Society Edinburgh 83, 145–153. [CrossRef]

- Zorpi, M.J., Coulon, C., Orsini, J.B., Cocirta, C., 1989. Magma mingling, zoning and emplacement in calc-alkaline granitoid plutons. Tectonophysics 157, 315–329. [CrossRef]

- Vernon, R.H.1984. Microgranitoid enclaves in granites: Globules of hybrid magma quenched in a plutonic environment: Nature, v. 309, p. 438–439.

- Vernon, R.H. 1991. Crystallization and hybridism in micro granitoid enclave magmas: Microstructural evidence: Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 95, p. 17, 849–17, 859.

- Chappell, B. W., White, A. J. R., Wyborn, D. 1987. The importance of residual source material (restite) in granite petrogenesis. Journal of Petrology, 28, 1111-38. [CrossRef]

- Chappell, B.W., White, A.J.R., 1992. I-type and S-type granites in the Lachlan Fold Belt. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences 83, 1–26.

- Zhang, S. H., Zhao, Y. 2017. Cogenetic origin of mafic microgranular enclaves in calc-alkaline granitoids: The Permian plutons in the northern North China Block. Geosphere, v. 13, no. 2, p. 482–517. [CrossRef]

- Flood, R.H., Vernon, R.H. 1988. Microstructural evidence of orders of crystallization in granitoid rocks. Lithos, 21, 237-245. [CrossRef]

- Elangovan, R., Krishna, K., Vishwakarma, N., Hari, K. R., and Mohan, M. R. (2017). Interaction of coeval felsic and mafic magmas from the Kanker granite, Pithora region, Bastar Craton, Central India. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 126:92. [CrossRef]

- Slaby, E., Gotze, J., Worner, G., Simon, K., Wrzalik, R., Smigielski, M., 2008. K-feldspar phenocrysts in microgranular magmatic enclaves: cathodoluminescence and geochemical study of crystal growth as a marker of magma mingling dynamics. Lithos 105, 85–97. [CrossRef]

- Renjith, ML., Charan, S.N., Subbarao, D.V., Babu, E.V.S.S.K., Rajashekhar, V.B. 2014. Grain to outcrop-scale frozen moments of dynamic magma mixing in the syenite magma chamber, Yelagiri Alkaline Complex, South India. Geoscience Frontiers, (5) 801-820.

- Kumar, S., Rino, V., Pal, A.B. 2004. Field evidence of magma mixing from microgranular enclaves hosted in Palaeoproterozoic Malanjkhand granitoids, central India. Gondwana Research, 7(2), 539-548. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, L.A., Sparks, R. S. J. 1984. Origin of some mixed-magma and net-veined ring intrusions. Journal of the Geological Society, 141 (1): 171–182. doi: . [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, M.J.1981. The magma mixing origin of mantled feldspars: Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, v. 76, p. 158–170.

- Barbarin, B. 1990. Plagioclase xenocrysts and mafic magmatic enclaves in some granitoids of the Sierra Nevada batholith, California. Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 95, p. 17.747–17.756. [CrossRef]

- Janoušek, V., Braithwaite, C.J.R., Bowes, D.R., Gerdes, A. 2004. Magma-mixing in the genesis of Hercynian calc-alkaline granitoids: an integrated petrographic and geochemical study of the Sávaza intrusion, Central Bohemian Pluton, Czech Republic. Lithos, 78, 67–99.

- Dománska-Siuda, J., Słaby, E., Szuszkiewicz, A., 2019. Ambiguous isotopic and geochemical signatures resulting from limited melt interactions in a seemingly composite pluton: a case study from the Strzegom–Sobótka Massif (Sudetes, Poland). Int. J. Earth Sci. 108, 931–962. [CrossRef]

- Baxter, S., Feely, M., 2002. Magma mixing and mingling textures in granitoids: examples from the Galway Granite, Connemara, Ireland. Mineral. Petrol. 76, 63–74. [CrossRef]

- Perugini, D., Poli, G. 2005. Viscous fingering during replenishment of felsic magma chambers by continuous inputs of mafic magmas: field evidence and fluid-mechanics experiments. Geology 33:5–8. [CrossRef]

- Perugini, D., De Campos, C.P., Dingwell, D.B., Petrelli, M., Poli, G. 2008. Trace element mobility during magma mixing: preliminary experimental results. Chem Geol 256:146–157. [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, M., Perugini, D., Poli, G. 2011. Transition to Chaos and implications for Time-scales of Magma Hybridization during mixing processes in Magma chambers. Lithos 125:211–220. [CrossRef]

- Morgavi, D., Perugini, D., De Campos, C.P., Ertl-Ingrisch, W., Dingwell, D.B. 2013. Time evolution of chemical exchanges during mixing of rhyolitic and basaltic melts. Contrib Mineral Petrology, 166(2):615–638. [CrossRef]

- De Campos, C.P., Perugini, D., Ertel-Ingrisch, W., Dingwell, D.B., Poli, G. 2011. Enhancement of Magma mixing efficiency by Chaotic Dynamics: an experimental study. Contrib Mineral Petr 161:863–88. [CrossRef]

- Kemp, A.I.S., Hawkesworth, C.J., Foster, G.L., Paterson, B.A., Woodhead, J.D., Hergt, J. M., Gray, C.M., Whitehouse, M.J., 2007. Magmatic and crustal differentiation history of granitic rocks from Hf-O isotopes in zircon. Science 315, 980–983. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.S., Matzel, J.E.P., Miller, C.F., Burgess, S.D., Miller, R.B., 2007. Zircon growth and recycling during the assembly of large, composite arc plutons. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 167, 282–299. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.C., Wiedemann, C.M., McReath, I., 2002. Norito e Charnoenderbitos da Borda do Maciço Intrusivo de Venda Nova, Espírito Santo, vol. 25. Anuário do Instituto de Geociências, pp. 99–124.

- Onken, C. T., Eberhard-Schmid, J., Hauser, L., Marioni, S., Galli, A., Janasi, V. A., & Schmidt, M. W. 2024: Timing and origin of the post-collisional Venda Nova and Várzea Alegre Plutons from the Araçuaí belt, Espírito Santo, Brazil. Lithos, 107677. [CrossRef]

- Noce, C.M., Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Silva, L.C., Armstrong, R., Piuzana, D. 2007. Evolution of polycyclic basement complexes in the Araçuaí Orogeny, based on U-Pb SHRIMP data: Implications for Brazil-Africa links in Paleoproterozoic time. Precambrian Res. 159, 60–78. [CrossRef]

- Lana, C., Mazoz, A., Narduzzi, F., Cutts, K., Fonseca, M., 2020. Paleoproterozoic sources for Cordilleran-type Neoproterozoic granitoids from the Araçuaí Orogeny (SE Brazil): constraints from Hf isotope zircon composition. Lithos, 105815. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.H., Mendes, J., Carvalho, M., Coelho, V., Medeiros, S., Valeriano, C. 2023. Petrogenesis of Estrela is granitoid and implications for the evolution of the Rio Doce magmatic arc: Araçuaí-Ribeira Orogenyic system, SE Brazil. 126.104337.10.1016/j.jsames.2023.104337. [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, C.A., Heilbron, M., Ragatky, D., Armstrong, R., Dantas, E., Valeriano, C.M., Simonetti, A., 2017. Tectonic evolution of the Juvenile Tonian Serra da Prata magmatic arc in the Ribeira belt, SE Brazil: implications for early West Gondwana amalgamation. Precambrian Res. 302, 221–254. [CrossRef]

| Rock Ttype | Main Mineralogy | Accessory Mineralogy |

|---|---|---|

| Monzogranite | Qtz+Kfs+Pl+Bt | Opq+Ttn+Ap+Zrn+Aln+Hbl |

| Granodiorite | Qtz+Kfs+Pl+Bt+Hbl | Opq+Ttn+Ap+Zrn |

| Quartz-Monzodiorite | Qtz+Kfs+Pl+Bt+Hbl | Opq+Ttn+Ap |

| Diorite | Pl+Bt+Hbl | Qtz+Kfs+Opq+Ttn+Ap |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).