1. Introduction

In publicly funded healthcare systems, general practitioners (GPs) are most commonly remunerated through fee-for-service (FFS), capitation (CAP), or fixed salary. Most OECD countries use a mix of different remuneration schemes [

1]. In FFS, GPs receive remuneration based on the level of activity, thereby incentivizing GPs to increase the volume of health services. In CAP systems, GPs receive remuneration according to the number of patients in their care, incentivizing GPs to enrol more patients. In fixed salary systems, GPs receive a salary that is not based on the activity level or number of patients.

Studies show that GPs remunerated by FFS provide a larger volume of health services than GPs working for CAP or fixed salary GPs [

2,

3,

4]. Also, studi es employing quasi-experimental methods reveal that GPs respond to increased incentives in FFS systems by increasing activity [

5,

6,

7]. Within systems with a CAP element, list size is negatively associated with consultation duration. [

8] Studies differ in whether they have found indications of upcoding in health care, i.e. unwarranted use of fees [

9,

10]. In general. GP earnings tend to be higher for men, self-employed GPs, and those working in larger practices [

11,

12], and reports based on Norwegian registry data also show that female GPs have lower earnings than their male counterparts [

13,

14].

There is a large literature on the differences between and the effects of different remuneration types, however, less is known about variation among GPs operating within the same FFS/CAP remuneration scheme. Studies have showed that a significant proportion of the variation in healthcare expenditures among physicians is attributable to physician-specific effects [

15] and that the effect of remuneration scheme is stronger for profit-oriented physicians [

16]. Further, experiments find considerable variations in how physicians balance profit considerations against patients’ health benefits when making medical decisions [

17,

18].

In this paper, we study annual earning differences and differences in earnings per listed patient. Annual earnings, defined as gross revenue, is a result of several factors, including workload and responsiveness to financial incentives. Since workload is closely linked to the number of patients on a GP’s list, earnings differences per list patient capture variations less influenced of workload driven by patient demand. In this paper, we compare high- and low earning GPs based on their annual earnings from FFS and CAP. Our aim is to explore whether these groups differ in earnings per listed patient and, if so, identify which fees contribute to this difference. Additionally, we aim to describe practice variations between high- and low-earning GPs.

2. Institutional Background

In Norway, health care is primarily publicly funded, and the municipalities are responsible for organizing primary care services. 78 % of GPs are self-employed and remunerated by a combination of FFS and CAP [

19], while 22 % are employed by the municipality and receive a fixed salary. The ’Regular general practitioner scheme’ links each patient to a regular GP in a list-based system. All residents have the right to be listed with a specific GP, and approximately 98 percent of the Norwegian population are enrolled on a GP’s list [

19]. As of 2022, there are 5056 GPs with an average list length of 1040 patients. GPs are often the first point of contact, and act as gatekeepers to patients’ access to specialized care, sickness absence certification and other health care services.

The financing of the Norwegian GP FFS/CAP system follows a dual structure. Approximately 30% of the funding are supposed to come from CAP based on the number of listed patents. The remaining 70% is sourced through FFS, reimbursed by The Norwegian Health Economics Administration (HELFO), in addition to co-payments from patients. To receive reimbursement from HELFO and co-payment from patients, GPs utilize fees with standardized rates. The rates are determined in negotiations between the Ministry of Health and Care Service, the Norwegian Medical Association and The Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities. Each fee corresponds to a type of contact (e.g. consultation, e-consultation, home visit), a type of procedure (e.g. laboratory test, talking therapy, prescription renewal) or time used (e.g. fee for prolonged consultation (> 20 min)). When a GP provides a service covered by the fee system, they submit a claim to HELFO specifying the fees for which they claim reimbursement. HELFO processes the claims and reimburses the GP according to established rates. The system is predominantly trust based, although HELFO employs certain automatic controls [

20]. The Norwegian setting is well-suited for investigating earnings variations among GPs, due to available high-quality nationwide registry data on all GPs, their listed patients, and on health services they have claimed reimbursement for.

3. Methods

Data and Variable Definitions

We analyse comprehensive administrative registry data for the year 2021, relying especially on the Norwegian Control and Payment of Health Reimbursement Database (KUHR). This database provides detailed information on all reimbursement claims submitted by Norwegian GPs to HELFO for consultations and procedures performed for their patients. The data we use includes 19 million reimbursement claims with pseudonymised GP and patient identifiers, whether the GP holds a specialisation in family medicine, type of contact (consultation, home visit, simple contact etc.), fees claimed, and date and time for the contact. We merge this dataset with The Norwegian General Practitioner Registry (FLO) with information on GP characteristics (age, gender, number on patient list), patient list characteristics (gender and proportion of listed patients in the age groups “19 years or younger”, “20-66 years”, and “67 years or older”), remuneration type, and whether the GP is as owner of a patient list or a locum.

We define

GP earnings as the gross earnings from all fee reimbursements from HELFO, co-payments from patients and capitation payment per list patient on their patient list in 2021. Fee reimbursements and co-payments are calculated by multiplying the number of times a GP is reimbursed for each specific fee by the fee claim for the given fee as of 1. January 2021. Capitation earnings is calculated according the average capitation rates of 2021 [

21] with 610 NOK for each of the first 1000 list patients and 513 NOK for list patients beyond that.

By using information on date and time of each contact between GPs and their patients we estimate consultation duration as the time difference between the start time a consultation (2AD or 2AE) and its following consultation. The estimation only includes daytime consultations that begin between 09:00 and 14:59 on workdays, and that are followed by another consultation. At the GP level, we exclude days when the GP conducted home visits to patients b efore 15:00, days where 80% or more of the GP’s activity had overlapping start times, and days where 80% or more of the consultations started at standard intervals (e.g., 09:00, 09:10, 09:15, etc.).1

All variables are calculated by first estimating a value for each GP (for example the proportion of listed patients that is female, the number of consultations per list patient or mean consultation duration), and thereby calculating the mean for each group (all self-employed, earning groups among self-employed and GPs with fixed salary).

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health has conducted privacy impact assessment with respect to the data used, and Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics South East Norway have granted exempt from confidentiality (29 October 2020, #118472).

Study Sample

Our main sample includes all GPs with a specialisation2 in general medicine with at least 100 working days3 in 2021 and registered as owners of a patient list (N = 2546). GPs that have worked as both self-employed and as fixed salary GP during 2021 were excluded.

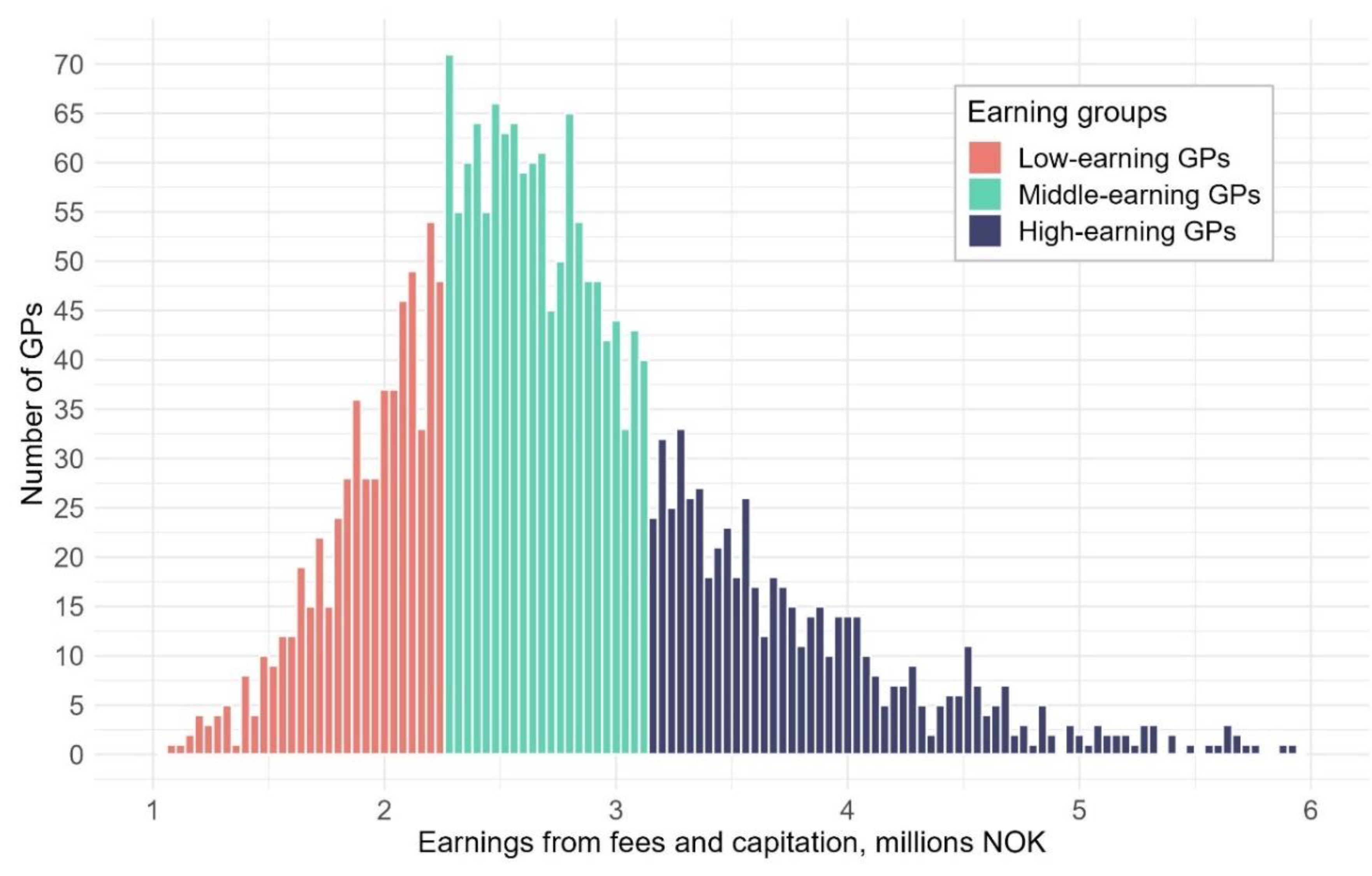

We categorise self-employed GPs into three groups based on their earnings: low earning GPs (1

st earning quartile), high earning GPs (4

th earning quartile) and the middle earning GPs (2nd and 3rd earning quartiles) (illustrated in

Figure 1). As a comparison we also display descriptive statistics for GPs with fixed salary(N=131) as a group of GPs with other financial incentives than self-employed GPs.

Analysis

Our study relies on a descriptive comparison between groups. In

Table 1 we compare GP characteristics, patient list characteristics and annual fee earnings for self-employed GPs (in total and across high-, middle-, and low-earning GPs), as well as GPs on fixed salaries. In

Table 2, we focus on self-employed GPs and decompose the mean earnings per list patient from each fee across the earning groups. It highlights how much each fee contributes to the per patient difference in earnings and ranks specific fees in descending order according to fees where high-earning GPs earn relatively more compared to low-earning GPs. In

Table 3, we examine practice variations across groups by comparing the number of fees registered per patient, GPs average estimated consultation durations and the total consultation minutes in a year per list patient.

We conducted several supplementary analyses to further understand and interpret the results. This includes an analysis of the earnings ratio between CAP and FFS, and all similar analyses conducted in the paper on a sample that have not a specialisation in general medicine. The tables can be found in the supplementary material and will be used in the results and discussion sections.

4. Results

High earning GPs have on average 1488 list patients, 55% more than low earning GPs with 957 list patients on average (

Table 1a). Further, high earning GPs earn 120% more from fee earnings compared low earning GPs (NOK 2 983 551 versus NOK 1 352 675) (

Table 1c). This means that, although more list patients to serve, high earning GPs earn 40% more per patient from fees. More specifically, for each listed patient, high earning GPs earn NOK 2081 annually per list patient from fees, while their low earning colleagues earn NOK 1488. This difference on NOK 593 constitutes a difference in earnings that is unexplained by the number of patients and will be further investigated in this paper.

The earning groups are quite similar in the composition of GPs’ and list patients’ age and gender. The high earning GPs are slightly older than low- and middle earning GPs, with 2 years difference on average. There are small differences in terms of the age and gender composition of the list patients. High earning GPs have marginally more men and people in working age on their lists, while low earning GPs have slightly more female and younger patients. The only characteristic where the groups differed considerably, was the gender of the GP. Only 22% of the high earning GPs are women, while 53% are women in the low earning group.

Fixed salary GPs have fee earnings resembling low earning GPs, with a comparable annual fee earning and fee earning per list patient. . Fixed salary GPs are younger and comprise slightly more women than the average self-employed GPs. Fixed salary GPs’ list patients are remarkably similar to the self-employed GPs’ list patients with regards to both for age and gender composition. Since there are not many GPs that are remunerated by fixed salary when a specialist, they are considerably fewer than the other groups.

There are large variations in earnings generated from fees and capitation among Norwegian GPs (

Figure 1), where 95% of all GPs in our sample have earnings between 1.7M to 4.3M NOK. Low earning GPs earn less than 2.3M NOK, while high earning GPs earn more than 3.16M NOK. On average, GP earnings (fees and CAP) is 2.8M NOK, where 2.1M NOK (74%) is from fees and 0.7M NOK (26%) is from CAP (

Supplementary Table S1). For high earning GPs, fees constitute a larger share of earnings (78%) than for low earning GPs (70%).

Figure note: x-axis represents GPs earnings from CAP and FFS in 2021 (measured in millions), and the y-axis represents the number of GPs within each bar (every 40 000 NOK). Taxes and practice expenses are not included.

Earnings Difference per List Patient

We have showed that high earning GPs also have higher fee earnings per list patient (40% higher) compared to low earning GPs. In this section, we will decompose this difference in fee earnings per list patient between high- and low earning GPs (hereafter referred to as the earnings difference). In

Table 2, we have included the 38 fees that contributes most to the earnings difference. These 38 fees together account for 95 % of the earnings difference. It shows how much each earning group earn from that specific fee per list patient and how much each fee contributes to the earning difference between high- and low earning GPs.

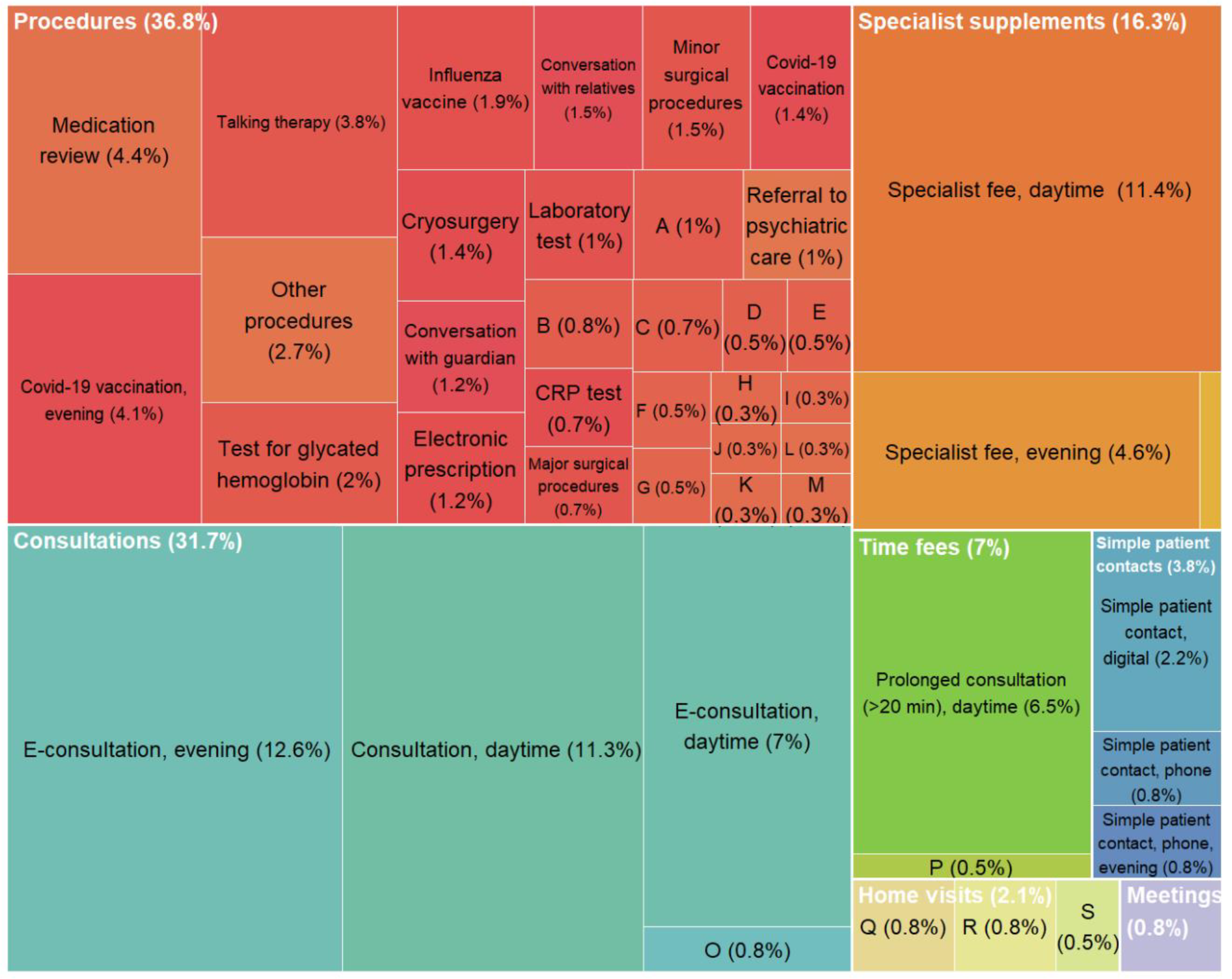

The type of fees that contributes most to the difference, is consultations and related specialist fees.

4 Five of the six most contributing fees are of this type. At the top of the list are evening e-consultations. While this service is neither among the most common nor the most profitable (yielding only 39 NOK per list patient for all self-employed), it contributes the most to the income difference (12.6%) between high- and low-earning GPs. This is due to high-earning GPs using this fee nearly seven times more frequently per patient than low-earning GPs, resulting in an average of 87 NOK versus 13 NOK in fee earnings per list patient. Daytime specialist fee (11.4%), consultation (11.3%) and e-consultation (7%) are the fees that thereafter contributes most. As shown in

Figure 2, consultation fees and specialist fees constitute together 48% of the difference (31.7% and 16.3%). Other fees that have a considerable contribution to the difference are the fee for prolonged consultation (6.5%), medication review (4.4%), evening covid-19 vaccination (4.1%) and talking therapy (3.8 %).

For the majority of the 150 relevant fees, and all fees included in

Table 2, high earning GPs earn more per list patient than the low earning GPs. There are six fees for which low earning GPs earn more per patient than high earning GPs. These include fees for simple patient contact, gynaecological examination, and dialogue meeting with social welfare services (

Supplementary Table S2). Fixed salary GPs have lower fee earnings per list patient for most of the fees. The exception to this is fees such as covid-19 vaccination, laboratory test, collaboration meeting and simple patient contact (phone or digital).

Figure note: The figure shows the percent of the fee earnings difference between high-and low earning GPs that can be attributed to main categories and specific fees. The calculations are explained in detail for 2f in

Table 2.

Practice Variation

High earning GPs utilized more procedure fees per listed patient compared to low earning GPs (5.6 versus 3.9 per list patient) (

Table 3a). They also used consultation fees more frequently per list patient, including daytime consultations (2.32 versus 1.9), daytime e-consultations (0.83 versus 0.59), and evening e-consultations (0.28 versus 0.04). Additionally, high earning GPs more often claimed compensation for talking therapy (0.2 versus 0.09) and the fee for prolonged consultations (1.13 versus 0.96) than their low earning counterparts.

Despite that high earning GPs use procedure and consultation fees more frequently, including the fee for prolonged consultation, the average duration of various types of consultations was consistently shorter compared to those of middle- and low earning GPs (

Table 3b). For example, a daytime consultation averaged 15 minutes for high earning GPs, compared to 18 minutes for middle earning GPs and 20 minutes for low earning GPs. This time difference persisted even for more time-intensive consultations, such as those involving talking therapy.

By combining the information on number of consultation fees per listed patient in 2021 (

Table 3a) and the estimated duration on each consultation (

Table 3b) we have also estimated the total consultation minutes in a year per list patient (

Table 3c). Each patient on a high earning GP’s list receives less time in consultations during a year (34.8 minutes) compared to middle- and low earning GPs (35.4 min and 37.9 min).

Fixed salary GPs resemble low earning GPs in their use of fees and consultation duration in a large extent. They use all the fees in

Table 3 slightly less than low earning GPs, and considerably less than middle and high earning GPs. For example, fixed salary GPs use 3.7 procedure fees per patient, while the corresponding value for low, middle, and high earning GPs are 3.9, 4.5 and 5.6. For mean consultation duration and total consultation duration in a year, fixed salary GPs have a comparable duration to low earning GPs, only slightly longer (20.8 min vs. 20 min).

Supplementary Analysis

In addition to the main analyses, we have conducted some supplementary analyses in order better understand how the results may be interpreted.

Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 have been previously referred to, and this section will briefly address the supplementary

Tables S3 and S4 (a-c). In the

Supplementary Table S3, we have developed measures to help determine the extent to which the results can be interpreted as differences in activity or differences in fee usage. These measures can be interpreted as indication of undercharging, subjective interpretation, and overcharging, and are used in the discussion section.

Supplementary Table S4 a-c are corresponding

Tables for

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 with the sample of GPs without specialisation in general medicine. In general, many of the same trends are observed among GPs without specialisation than for GPs with specialisation. However, there are some differences between the two samples. High earning GPs still earn more fee earnings per list patient than low earning GPs (26 %), but the earnings difference is larger when comparing to middle earning GPs (30 %). This means that low earning GPs earn more per list patient than middle earning GPs. There are many of the same fees that make up the difference between high and low earning GPs, with the largest exception of daytime consultation. The low earning GPs without specialisation in general medicine have more daytime consultations per patient than high earning GPs. Middle earning GPs have lowest number of daytime consultations per patient.

5. Discussion

Our results show large variations in GP earnings in Norway. High earning GPs earn 40 % more from fees per listed patient compared to low earning GPs. Around half of this difference can be attributed to that high earners conduct more consultations per patient. However, high earning GPs also spend less time per patient per year, due to a shorter average consultation duration (15 min. versus 20 min.). The remaining half of difference can be attributed to higher utilization of pro cedure fees per patient (5.6 versus 3.9). High earning GPs use almost every procedure fee more frequently compared to their low earning counterparts. The procedure fees that contribute most to the fee earning difference are fees such as prolonged consultation fee (6.5 %), systematic medication review (4.4 %), and talking therapy (3.8 %).

Differences in Activity or Differences in Fee Usage?

We have shown that high and low earning GPs clearly differ in their use of fees. These differences likely reflect, to a large extent, actual differences in

activity level, i.e. the services provided to patients, between the groups. Differences in activity level might be a result of systematics differences in GPs’ treatment preferences or patient list characteristics (health status, behaviour, comorbidities). We cannot measure GPs’ treatment preferences. As regards systematic differences in patient list characteristics, we do not observe large differences between the groups in terms of the patients’ age and sex (

Table 1). There might be other patient list characteristics that we cannot account for here that contribute to the difference.

Previous research has directly interpreted fee usage as activity level [

2], however, we argue that this is a misconception.

5 The fee system is both trust-based and comprehensive. Therefore, we cannot directly interpret differences in fee usage as differences in actual activity. Whether or not certain fees apply to specific treatments or patient interactions may sometimes be up to the GP’s subjective interpretation. Thus, in certain cases, two GPs providing the same treatment to a patient might claim different fees or a different number of fees. We have created some measures that may indicate in which direction the results may be interpreted (

Supplementary Table S3). This should not be viewed as a conclusive answer, but rather as a first step to an improved understanding.

We suggest three ways in which differences in fee usage may appear. Differences in fee usage may be a consequence of between-group differences in undercharging, i.e., not claiming fees for services that can be reimbursed, overcharging, i.e., unwarranted use of fees, or subjective interpretation, i.e., claiming a fee in cases where it is not obvious whether the fee is applicable or not. Our supplementary analyses show support for the claim that the differences can be interpreted as differences in overcharging of fees and subjective interpretation of fees.

To assess the different ways in which fee usage may explain earnings differences, we have developed measures for each type of difference in fee usage. First, to examine the degree of

undercharging, we compared the number of specialist time fees (2cdd) to the number of standard time fees (2cd). Specialist time fees can only be used when a standard time fee is also used, and therefore we can compare the share of specialist time fees on standard time fees. We found that the low, middle, and high earning GPs used 2cdd approximately 90% of the time, indicating some undercharging, however the differences between the groups are minor (

Supplementary Table S3). Second,

overcharging was examined by estimating the share of consultations where the time fee (2cd) was used for consultations lasting less than 20 minutes. Of all consultations with 2cd, we estimated that 41% of high earning GPs’ consultations lasted shorter, while the corresponding number for low earning GPs was 25%. Although there may exist random errors to this estimate, it indicates that unwarranted use might explain some of the differences between the groups. Last, to assess the importance of

subjective interpretation of fees we calculated the number of times the cryosurgery fee (wart treatment, 111) is repeated when it is used at least once. We chose this because, if repeated, it is regarded as a highly profitable fee. Also, counting the number of warts a patient has, might not be straightforward. We found that high earning GPs repeat the fee 2.07 times, while low earning GPs repeat it 1.38 times on average. Assuming that warts are evenly distributed among the earning groups’ patients, this indicates that subjective interpretation of fees might explain some of the differences between the groups.

How Can this Study Add to the Existing Literature?

We have shown substantial earning differences among GPs remunerated by FFS and CAP, highlighting the importance of studying variation within remuneration systems. In many respects, low earning GPs are similar to the fixed salary GPs that have no (or minor) financial incentives. This indicate that low earning GPs are less responsive to incentives, and that earnings can reflect the degree of responsiveness to incentives. We add to the existing literature [

3,

4,

5] by showing differences in practice style by GPs’ earnings from the FFS/CAP system. By interpreting the difference between high- and low earning GPs as a stronger/weaker response to the incentives, we find that this FFS/CAP system incentivises more list patients, more consultations per patient, more procedures per patient, shorter consultation duration, and less time spent on each patient yearly.

Our study’s findings can contribute to the discussion about the relationship between financial incentives and gatekeeping decisions among GPs. GPs have reported that when they encounter patient requests that they deem unreasonable, it requires a lot more time to reject it, rather than accept it [

22]. Studies have highlighted that shorter consultation duration may weaken GPs gatekeeping role, related to increased sick-listing [

23], prescribing of antibiotics [

24,

25] or addictive drugs [

25]. In addition, studies have found that fee-for-service remuneration also are associated with higher antibiotic prescriptions [

26] and increased sick-listing [

27] compared to fixed salary. We find that high earning GPs have 25 % shorter average daytime consultation duration than low earning GPs (15 vs. 20 min.). If we interpret the results that variation in GP earnings represents a variation in the response to the financial incentives within the FFS/CAP system, this may indicate that the system facilitates poorer conditions for gatekeeping decisions.

Strengths and Limitations

The study’s main strength is the analysis of rich administrative data covering all reimbursements to Norwegian GPs, providing a unique opportunity to explore variation among GPs in their utilization of fees. The advantage of our empirical design, a descriptive study, is that it allows researchers to provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter and serves as a foundation for generating hypotheses to be tested in future research. One of the limitations is that the design cannot empirically establish causal relationships. We cannot empirically distinguish between behaviour that is caused by variation in response to incentives and behaviour that is caused by variation in GPs’ general efficiency. Furthermore, this study has not adjusted for potential confounding variables except for the number of patients. For example, patient complexity can be related to income [

28], but we only know that that patients’ age and sex seems to be similar. Another limitation to the study is that expenses are not included, which means that we don’t know what the GPs actual income are.

A limitation of the study is that the analysis can be sensitive to specifications. For example, how we define the earning groups will affect the results. We have discussed several ways to do it, either hourly earnings on daytime, earning per patient or earning per consultation. We chose total earnings because it is transparent, provides an intuitive interpretation and are highly correlated with hourly earnings on daytime (correlation = 0.79). Also, in

Table 3, measures are sensitive to which denominator we choose. We have chosen per list patient, since it highlights how much services each patient has received. Another way would be to use per consultation as denominator, that would have highlighted how much services the patients got in an average consultation, but not in total.

Implications

From a policy perspective, this study contributes with relevant knowledge that should be taken into consideration when designing remuneration systems. The analysis aligns with former research that an FFS/CAP system incentivise more list patients and increased activity. It does not seem to be a contradiction between the number of list patients and how much services each patient receives. Increased activity can both be seen as increased capacity to provide the necessary services for patients, while also as overprovision of services that are unnecessary. Therefore, by introducing this kind of system, one should weigh the increased capacity against the increased overprovision of unnecessary services.

Some of the fees that contributes most to the difference between high and low earning GPs are fees that can be open for subjective interpretation. A way to reduce the likelihood of overprovision may be to make fees less open for subjective interpretation. However, this study cannot conclude if the system provides more necessary or unnecessary services compared to a fixed salary system.

One of the key elements in the system is how the consultation fee is incentivised. Theoretically, by increasing the consultation fee, relative to the CAP element and to the procedure fees, GPs are incentivised to have many short consultations rather than increasing list size or claiming many procedures. GPs should in some extent be incentivised to have many consultations in order to increase the GP’s availability. However, our study shows that GPs with a high number of consultations see their patients’ less in total. It is not clear whether it is most beneficial for the patient to have several shorter or fewer longer consultations, although longer consultations may favour stricter gatekeeping. However, for policy makers, it is somewhat more expensive with several short consultations. High earning GPs earn 66 NOK more per patient than low earning GPs because of a more frequent use of the consultation.

6. Conclusions

High earning GPs have 55% more listed patients than low earning GPs, yet they earn 40% more from fees per patient (average €178 versus €127). Nearly half of the earnings difference per patient can be attributed to high earning GPs more frequently conducting consultations with patients. Still, patients of high earning GPs receive less time in consultations annually (average 35 versus 38 min), due to high earners’ shorter consultation duration (average 15 versus 20 min). The remaining earning difference comes from higher utilization of procedure fees among high earners (average 5.6 versus 3.9 procedures per patient). Prolonged consultation, medication review, and talking therapy are some of the fees that contribute most to this difference. The findings highlight that considerable earning variations are linked to fee utilization and practice styles among GPs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Notes

| 1 |

The reason for the latter exclusion is that it is likely that the estimation does not captures actual consultation duration, but the largest possible duration or other systematic biases. Although we have tried to exclude the largest possible sources of errors, it still will probably overestimate the consultation duration. However, we do not believe that the overestimation is likely to be large and systematic. |

| 2 |

We have chosen to focus on GPs with specialisation of two reasons. First, there are specific fees that only can be used by GPs with specialisation, and therefore, including both specialised and not-specialised GPs would induce an earnings difference that have low analytical interest. Second, all GPs with a specialization have worked as general practitioners for many years, and differences due to length of experience are minimized. However, we have conducted similar analysis for GPs without specialisation ( supplementary Table S4 a-c), and these results are presented briefly in the end of the result section. |

| 3 |

We define a working day as any weekday with at least five daytime consultations. We choose to include only GPs with more than 100 days in order to balance two considerations: One the one hand, exclude the GPs that have low earnings because they work few days. On the other hand, we wanted to include variations of what can be considered as a normal working load among GPs in order to maintain a high degree of external validity. |

| 4 |

Specialist fees can be used together with consultations, and can therefore be viewed as a part of the earnings from consultations. |

| 5 |

Particularly when comparing remuneration schemes that provides different incentives to use fees, in addition to provide services. |

References

- The Commonwealth Fund. Country Profiles: International Health Care System Profiles [Internett]. 2020 [sitert 21. august 2024]. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.commonwealthfund.

- Brekke KR, Holmås TH, Monstad K, Straume OR. How does the type of remuneration affect physician behavior? Fixed salary versus fee-for-service. Am J Health Econ. 2020, 6, 104–38.

- Chaix-Couturier C, Durand-Zaleski I, Jolly D, Durieux P. Effects of financial incentives on medical practice: results from a systematic review of the literature and methodological issues. Int J Qual Health Care. 1. april 2000, 12, 133–42.

- Gosden T, Forland F, Kristiansen I, Sutton M, Leese B, Giuffrida A, mfl. Capitation, salary, fee-for-service and mixed systems of payment: effects on the behaviour of primary care physicians. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, redaktør. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internett]. 24. juli 2000 [sitert 30. mai 2023];2011(10). Tilgjengelig på:. [CrossRef]

- Brekke KR, Holmås TH, Monstad K, Straume OR. Do treatment decisions depend on physicians’ financial incentives? J Public Econ. november 2017, 155, 74–92.

- Clemens J, Gottlieb JD. Do Physicians’ Financial Incentives Affect Medical Treatment and Patient Health? Am Econ Rev. april 2014, 104, 1320–49.

- Kantarevic J, Kralj B, Weinkauf D. Income effects and physician labour supply: evidence from the threshold system in Ontario. Can J Econ Can Déconomique. 2008, 41, 1262–84.

- Van Den Berg MJ, De Bakker DH, Westert GP, Van Der Zee J, Groenewegen PP. Do list size and remuneration affect GPs’ decisions about how they provide consultations? BMC Health Serv Res. desember 2009, 9, 39.

- O’Halloran J, Oxholm AS, Pedersen LB, Gyrd-Hansen D. Going the extra mile? General practitioners’ upcoding of fees for home visits. Health Econ. 2024, 33, 197–203.

- Brunt, CS. CPT fee differentials and visit upcoding under Medicare Part B. Health Econ. 2011, 20, 831–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng TC, Scott A, Jeon S, Kalb G, Humphreys J, Joyce C. WHAT FACTORS INFLUENCE THE EARNINGS OF GENERAL PRACTITIONERS AND MEDICAL SPECIALISTS? EVIDENCE FROM THE MEDICINE IN AUSTRALIA: BALANCING EMPLOYMENT AND LIFE SURVEY. Health Econ. november 2012, 21, 1300–17.

- Morris S, Goudie R, Sutton M, Gravelle H, Elliott R, Hole AR, mfl. Determinants of general practitioners’ wages in England. Health Econ. 2011, 20, 147–60.

- Claus G, Hove IH. Fastlegers inntekter og kostnader 2020. SSB. 2020.

- Hoff EH, Kraft KB, Østby KA, Mykletun A. Arbeidsmengde, konsultasjonstid og utilsiktede effekter av takstsystemet. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of Public Health; 2023.

- Grytten J, Sørensen R. Practice variation and physician-specific effects. J Health Econ. mai 2003, 22, 403–18.

- Brekke KR, Holmås TH, Monstad K, Straume OR. How Does the Type of Remuneration Affect Physician Behavior? Fixed Salary versus Fee-for-Service. Am J Health Econ. 2020, 6, 104–38.

- Godager G, Wiesen D. Profit or patients’ health benefit? Exploring the heterogeneity in physician altruism. J Health Econ. 1. desember 2013, 32, 1105–16.

- Brosig-Koch J, Hennig-Schmidt H, Kairies-Schwarz N, Wiesen D. The Effects of Introducing Mixed Payment Systems for Physicians: Experimental Evidence. Health Econ. 2017, 26, 243–62.

- Pedersen K, Godager G, Tyrihjell J, Værnø S, Gundersen M, Iversen T, mfl. Evaluering av handlingsplan for allmennlegetjenesten 2020-2024, Evalueringsrapport 2 [Internett]. Oslo; 2023 [sitert 1. juni 2023]. Report No.: 2. Tilgjengelig på: https://osloeconomics.no/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/HPA-evalueringsrapport-II-2023.

- Helfo - for helseaktører [Internett]. [sitert 2. april 2024]. HELFO. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.helfo.

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health. Nærmere om basistilskudd, grunntilskudd og utjamningstilskudd [Internett]. [sitert 8. oktober 2024]. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.helsedirektoratet. 2021.

- Kraft KB, Hoff EH, Nylenna M, Moe CF, Mykletun A, Østby K. Time is money: general practitioners’ reflections on the fee-for-service system. BMC Health Serv Res. 15. april 2024, 24, 472.

- Hoff EH, Kraft KB, Moe CF, Nylenna M, Østby KA, Mykletun A. The cost of saying no: general practitioners’ gatekeeping role in sickness absence certification. BMC Public Health. 12. februar 2024, 24, 439.

- Linder JA, Singer DE, Stafford RS. Association between antibiotic prescribing and visit duration in adults with upper respiratory tract infections. Clin Ther. 1. september 2003, 25, 2419–30.

- Neprash HT, Mulcahy JF, Cross DA, Gaugler JE, Golberstein E, Ganguli I. Association of Primary Care Visit Length With Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing. JAMA Health Forum. 10. mars 2023, 4, e230052.

- Hutchinson JM, Foley RN. Method of physician remuneration and rates of antibiotic prescription. Canadian Medical Association. 1999, 160, 1013–7.

- Markussen S, Røed K. The market for paid sick leave. J Health Econ. september 2017, 55, 244–61.

- Olsen, KR. Patient complexity and GPS’ income under mixed remuneration. Health Econ. 2012, 21, 619–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).