Submitted:

04 November 2024

Posted:

05 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Main Text

GLM Workflow of Genomic Sequence Analysis

2.1. Genomic Sequence Representation

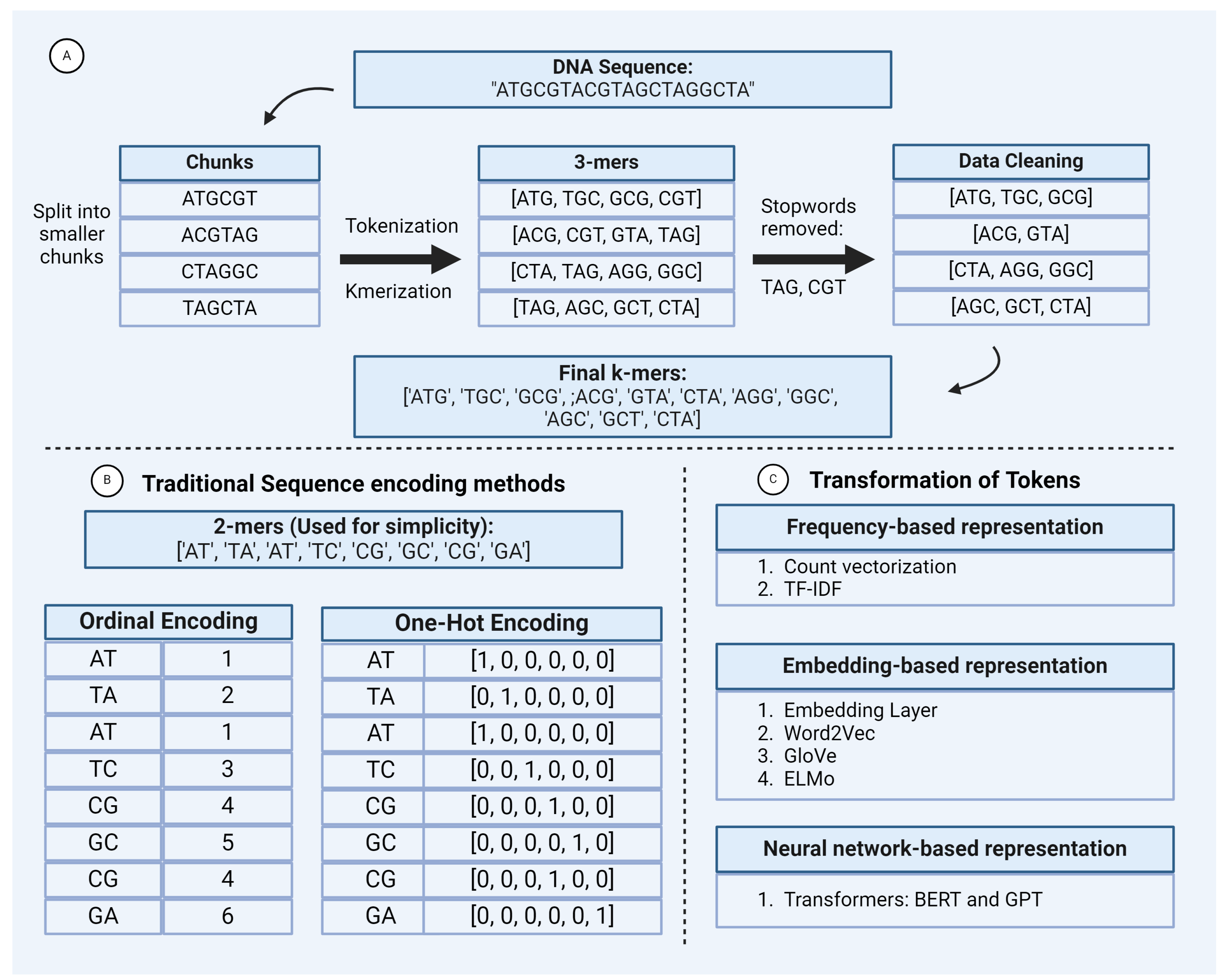

2.1.1. Preprocessing

2.1.2. Sequence Encoding Techniques

2.2. Feature Extraction

2.2.1. Tokenization

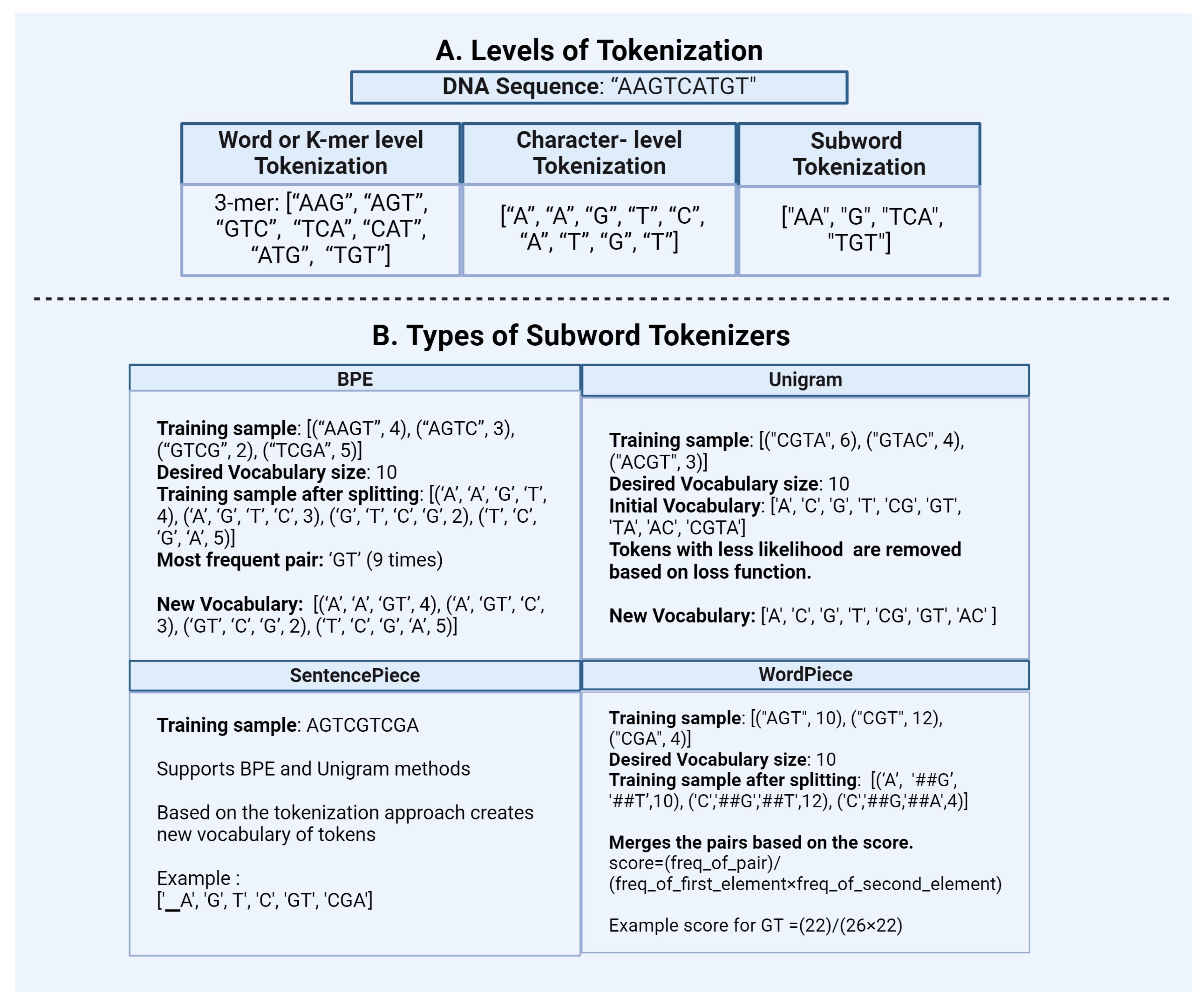

1. Word or K-Mer Level:

2. Character Level:

3. Subword Tokenization:

3.1 Byte Pair Encoding (BPE)

3.2 Unigram

3.3 Specialized subword tokenizer

- SentencePiece: SentencePiece is a modified version of subword units approach. It is an effective and language-independent sub-word tokenizer, owing to its pre-tokenization-free approach. During tokenization, SentencePiece treats the sentences as raw texts and defines a fixed vocabulary size for creating the vocabulary. It then converts all characters into Unicode including whitespaces. This feature helps to handle accurate reverse conversion from detokenized tokens to original ones (lossless tokenization). Using these features, SentencePiece could be easily extended to languages like Japanese and Chinese, which do not use spaces. This feature makes it an effective approach for biological sequences as well. SentencePiece also gives flexibility to choose between BPE and Unigram as subword algorithms which improves the robustness of the entire tokenization approach [Figure 2]. Transformer models like ALBERT, XLNet, and T5 use SentencePiece in conjunction with Unigram.

- WordPiece: WordPiece is a tokenization approach similar to BPE. It has similar merge rules like BPE but differs in the selection of token pairs to be merged. WordPiece starts by creating a vocabulary of tokens from the initial words by splitting the word into each character and appending WordPiece prefix ’##’. It then merges the tokens based on the below scoring formula. According to this formula, the pairs which appear less frequently in the text gets merged than those which appear too frequently. WordPiece was developed by Google to train the BERT model, then it got reused in many other transformer models like DistilBERT, MobileBERT and MPNET.

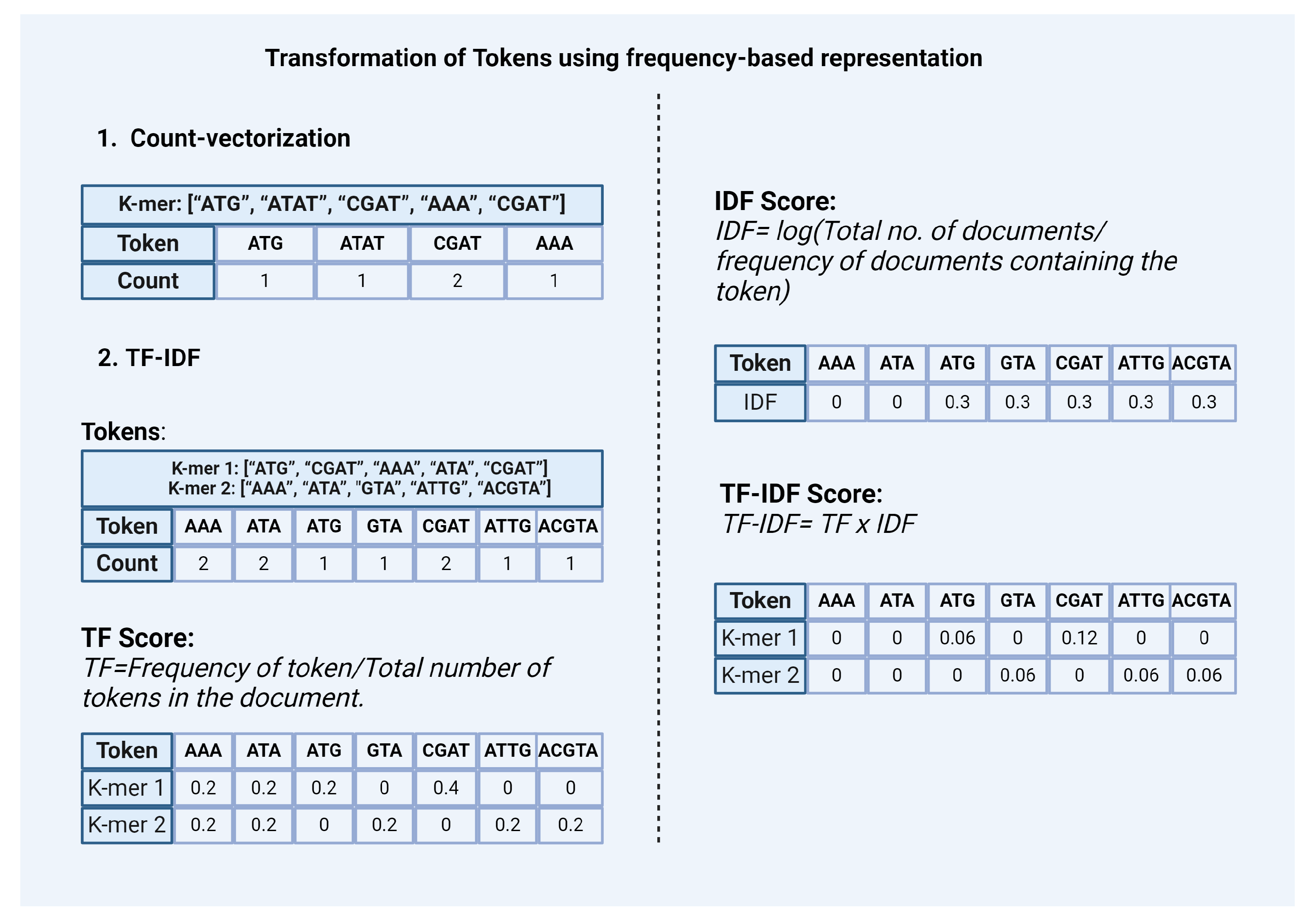

2.2.2. Transforming Tokens Using Frequency-Based Representation

- Count-vectorization: This method counts the number of occurrences of each token and represents it as a vector or matrix [Figure 3]. This method considers high-frequency words as more significant.

-

TF-IDF: In the context of natural language data Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) is a statistic based on the frequency of a token in the document. It is used to analyze the difference between the two documents by the uniqueness of tokens. A higher value of TF-IDF signifies higher importance of the tokens in the corpus while lower values represent lower importance. It is calculated by combining two metrics: Term Frequency (TF) and Inverse Document Frequency (IDF) [Figure 3].Term Frequency (TF) scoreIt is based on the frequency of tokens or words in the document. TF is calculated by dividing the number of occurrences of a token (i) by the total number (N) of tokens in the document (j).TF (i) = frequency (i,j) / N (j)Inverse Document Frequency (IDF) scoreIt is a measure that indicates how commonly a token is used. It can be calculated by dividing the total number (N) of documents (d) by the number of documents containing the token (i).IDF (i) = log (N (d) / frequency (d, i))The final TF-IDF score is calculated by multiplying TF and IDF scores.TF-IDF (i) = TF (i) x IDF (i)Similar to the Countvectorizer method, TF-IDF also gives priority to the tokens that have the highest frequency of occurrence in the document or the corpus. However, these count-based methods fail to capture the semantic relationship between tokens.

2.2.3. Transforming Tokens Using Embedding and Neural Network-Based Representations

Non-Contextual

- 1.

-

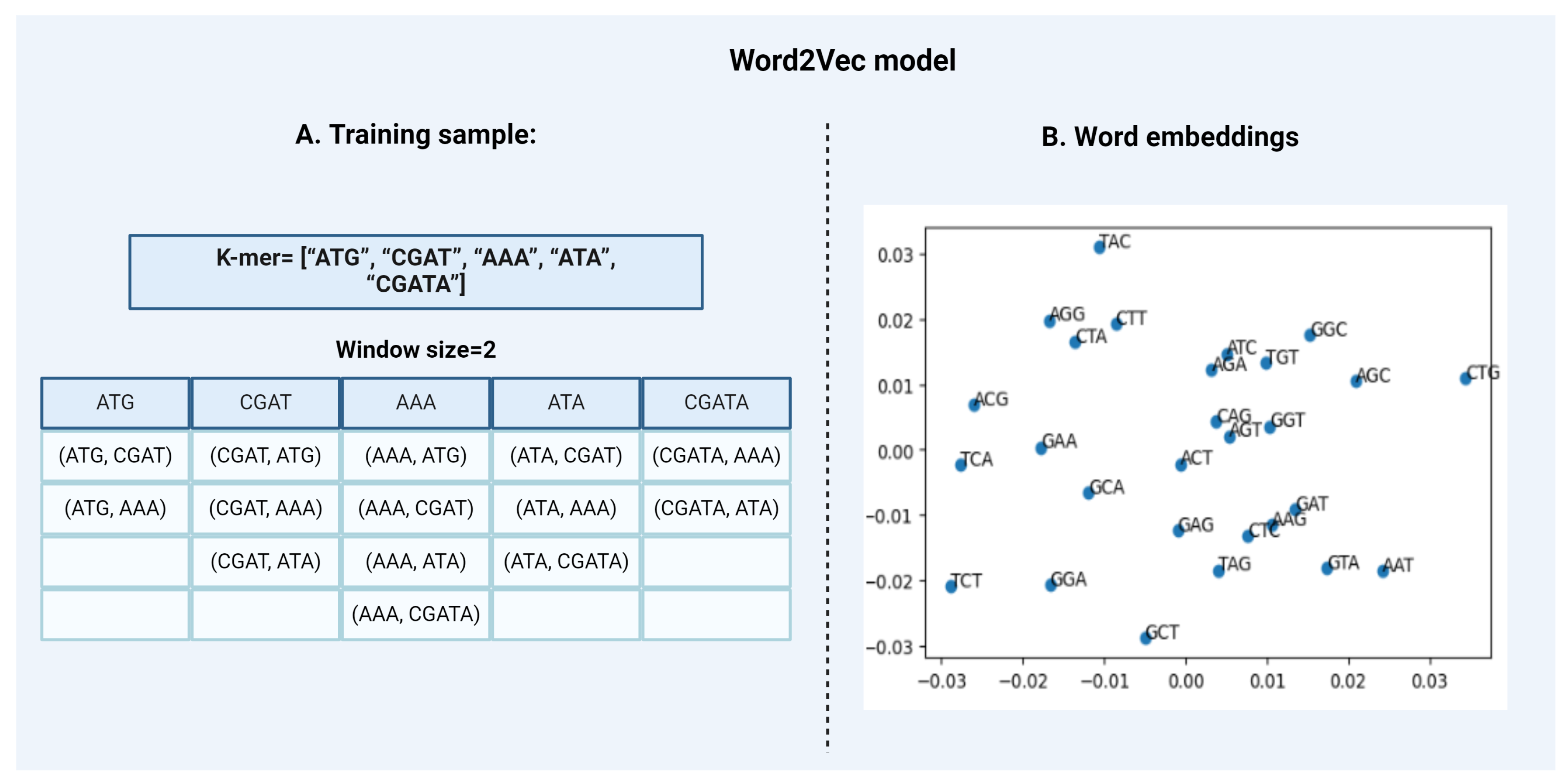

Word2VecWord2Vec is a statistical method that attempts to explain word embedding based on the corpus. It can do that by implementing two strategies:

- Continuous Bag-of-Words, or CBOW model.

- Continuous Skip-Gram Model.

CBOW is a representation of text that describes the occurrence of words within a document. This model is only concerned with whether known words occur in the document, not where in the document. We convert a corpus of text of variable-length (unstructured data) into a fixed-length vector which is structured and well-defined and thus preferred by NLP Algorithms. The CBOW model learns the embedding by predicting the current word based on its semantics or context. The continuous skip-gram model on the other hand, learns by predicting the surrounding words given a current word. Both models are focused on learning about words given their local usage context, where the context is defined by a predefined window of neighboring words. For Example, a window size of 2, means that for every word, we’ll consider the 2 words behind and the 2 words after it [Figure 4]. The Skip-Gram model works well with small-scale data, and better represents rare words or phrases. However, the CBOW model trains faster than Skip-Gram and better represents high-frequency words, thus giving a slightly better accuracy. The key benefit of the approach is that high-quality word embeddings can be learned efficiently i.e. with low space and time complexity, allowing larger embeddings to be learned from large-scale data. DNA2vec is the DNA equivalent of Word2vec i.e. it is used specifically for applying the Word2vec approach to DNA sequences. It is used to transform tokens of variable length k-mers preferably 3 to 8 using the skip-gram model approach and thus captures efficient information of the sequences [18]. Another example is the kmer2vec model which is more focused on embedding fixed-length k-mers, typically between 3 to 6 to capture sequence relationships. This model is useful for tasks that require uniform k-mer lengths such as identifying specific patterns within genomic sequences [21]. - 2.

-

Global Vectors for Word Representation (GloVe)The GloVe model is an extension of the Word2vec model for efficiently learning word vectors. Word2Vec only captures the local context of words. GloVe considers the entire corpus and creates a large matrix from the words in the corpus. The matrix has the words as the rows and their occurrence frequency as the columns for a corpus of text. For large matrices, we factorize the matrix to create a smaller matrix. GloVe combines the advantages of two-word vector learning methods: matrix factorization and local context window methods like Skip-gram which reduces the computational cost of training the model. The resulting word embeddings are different and improved. Word tokens with similar semantic meanings or similar contexts are placed together, for example, ‘queen’ and ‘women’. Being an extension to Word2vec, GloVe can be used for the representation of biological sequences as well. In a recent study, the GloVe model was integrated into a hybrid machine-learning model to classify gene mutations in cancer [1].

Contextual

-

Embeddings from Language Models (ELMo)ELMo are another way to convert a corpus of text into vectors or embeddings. ELMo word vectors are calculated by using a two-layer bidirectional language (biLM) model. Each layer has 2 passes, a forward pass, and a backward pass. It first converts the words into vectors. These vectors act as inputs to the first layer of the biLM model. The forward pass extracts and stores the information about the word in vector form and the context before it. The backward pass extracts and stores the information about the word and the context (other words) after it. This information contributes to the formation of intermediate word vectors which act as an input to the second layer of biLM. The final representation is done by the weighted sum of the initial word vectors and the two intermediate word vectors formed by the two layers. Recent studies use ELMo-based models to create embeddings for downstream tasks like protein structure prediction [9] [23].

-

TransformersTransformers are a type of neural network architecture used for NLP tasks. Transformers make use of an attention mechanism i.e. when a transformer looks at a piece of data, like a DNA sequence, it doesn’t just focus on one part. It pays attention to all the different parts at the same time. This helps it understand how everything fits together and find important patterns or relationships between tokens in the corpus of data for generating embeddings. A transformer model uses self-attention mechanisms to relate different positions within a single sequence. This allows each position in the sequence to attend to all other positions in the sequence, enabling the model to capture contextual information more effectively than traditional models.BERTBERT rely on this attention mechanism. In contrast to traditional (uni)directional models that read sequences from either the left or the right, transformers, including BERT use a bidirectional approach by using MLM in which tokens are masked at different intervals and models use preceding and succeeding tokens to predict the hidden tokens. BERT is an encoder-only transformer model. It takes input sequences and transforms them into fixed-size representations that capture important features. Word2vec or GloVe models generate a single-word embedding representation for each word in the vocabulary, whereas BERT will form a contextualized embedding that takes into account the context for each occurrence of a given word and will be different for each word according to the sentence. This enables BERT to provide more nuanced and accurate representations. This feature can be useful for tasks like classification and understanding genomic sequences that can have messages read in both directions and function via both short and long-range interactions. In genomics, DNABERT is a specialized adaptation of BERT for DNA sequences [11]. It is pre-trained on short sections of genomic data, learning patterns, and relationships. A newer version of DNABERT, DNABERT-2, uses BPE and other techniques to improve performance [33]. GenomicBERT uses unigram empirical tokenization to handle longer genomic sequences effectively and BERT attention mechanism to capture contextual relationships across large-scale biological datasets [4]. Other models like BioBERT, focusing on biomedical literature are leveraged to extract meaningful information from a vast biomedical text corpus [13,30]. Similarly, ClinicalBERT is employed in medical decision-making by analyzing clinical notes [10].Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPT)GPT are a type of transformer model but follows a different architecture than BERT. GPT models are based on a decoder-only framework. A decoder takes the representations generated from an encoder and uses these to generate predictions. GPT is trained using tasks like Autoregressive Language Modelling (ALM), where the model sees a series of sequences and predicts the next sequence. It will be suitable for tasks involving sequence prediction and understanding directional sequences in genomics. Numerous models inspired by GPT such as DNAGPT [31], BioGPT [15], GeneGPT [12], and ScGPT [6], are being pre-trained on genomic sequences and biomedical literature. These models are then employed in various specialised tasks like gene sequence recognition and protein sequence prediction. For example, DNAGPT has been specifically designed for DNA sequence tasks, while BioGPT focuses on generating biomedical text that can be adapted for genomic applications.

| Aspect | Ordinal Encoding | One-hot encoding | Word embedding | BERT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoding form | Each token is assigned an integer value. | Each token is represented by a vector (matrix). | Tokens that have the same meaning have similar representations. Each token is represented by real-valued vectors. | BERT provides contextualized embedding by taking into account the context of each token occurrence. |

| Semantic relationship | Does not capture the relationship between tokens. | Does not capture the relationship between tokens. | Captures the relationship between tokens. | It captures the relationship between tokens. |

| Categorical variables preferred | Suitable for ordinal variables but not for nominal. | Suitable for both nominal and ordinal variables. | Suitable for both nominal and ordinal variables. | Suitable for both nominal and ordinal variables. |

| Memory consumption and training time | Lower memory usage but may not scale well with large datasets. | High memory consumption due to large dimensions. | More efficient in terms of memory than one-hot encoding. | High memory consumption but scales with more data for better accuracy. |

| Handling OOV (Out of Vocabulary) words | Can not handle OOV words. | Can not handle OOV words. | Struggles with OOV words. | Efficiently handles OOV words with the help of modern tokenizers. |

| Tokenization Approach | Method | Pros | Cons | Reversibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character Tokenization | Splits the data into a set of characters. | Handles OOV words by breaking them into characters. Also, it has a limited size of vocabulary since it contains only a unique set of characters. | It doesn’t capture the semantic relationship between the tokens. | Non-reversible |

| Word Tokenization | Splits the data into tokens using a certain delimiter. | Large amounts of text can be easily tokenized without using complex computation. | Fails at handling Out of Vocabulary (OOV) words. Furthermore, doesn’t scale well with big datasets as it generates a huge amount of vocabulary. | Reversible |

| K-mer based Tokenization | The data is split into fragments of desired k-length. | Computationally less expensive method to generate tokens for genomic sequences. | Does not capture the relationship between the tokens and generates a larger vocabulary. | Non-reversible |

| Subword Tokenization | Splits the data into subwords (or n-gram characters). The most frequently used tokens are given unique IDs and the less frequent tokens are split into subwords. | Transformer-based models use this algorithm for preparing vocabulary. Has a decent vocabulary size. It does capture the semantic relationship between the tokens. | Increases computational cost while reducing the model interpretability. | Non-reversible |

| Method name | Type of Model | Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Byte pair encoding (BPE) | Frequency-based | Initially developed as a compression algorithm, found applicability in sub-word tokenization using frequency-based merge rules. |

| WordPiece | Score-based | Select tokens based on a scoring mechanism to create an effective tokenizer model. |

| Unigram | Probability and loss function based | By quantifying a loss function, iteratively removes less efficient tokens from a larger vocabulary based on their probabilities to build a fixed size vocabulary. |

| SentencePiece | Data-driven tokenization | Does not require pre-tokenization and is language independent. Provides flexible integration with BPE, Wordpiece, and Unigram methods |

ML Applications in Genomics

1. Classification

2. Prediction

3. Language Generation

Functional Annotation

3. Conclusion

4. List of Abbreviations

- EHR: Electronic Health Record

- GLM: Genome Language Modeling

- ML: Machine Learning

- BERT: Bidirectional encoder representations from transformers

- NLP: Natural Language Processing

- NER: Named Entity Recognition

- NSP: Next Sentence Prediction

- MLM: Masked Language Modeling

- LLMs: Large Language Models

- DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid

- RNA: Ribonucleic acid

- OOV: Out-of-vocabulary

- BPE: Byte Pair Encoding

- TF-IDF: Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency

- CBOW: Continuous Bag-of-Words

- GloVe: Global Vectors for Word Representation

- ELMo: Embeddings from Language Models

- biLM: bidirectional Language Model

- GPT: Generative Pre-trained Transformers

- ALM: Autoregressive Language Modelling

- RF: Random Forest

- CNN: Convolutional Neural Network

- RNNs: Recurrent Neural Networks

- LSTM: Long Short-Term Memory

- RFCN: Residual Fully Connected Neural Network

- BLAST: Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

5. Declarations

- Funding: S.T acknowledges AISRF EMCR fellowship from Australian Academy of Science. N.V acknowledges scholarship (RRITFS and STEM) from RMIT University, Melbourne. N.T acknowledges APBioNet for the support to present GLM research at the International Conference on Bioinformatics (INCOB) 2023 in Australia.

- Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests

- Acknowledgements: We thank Tyrone Chen for helpful discussions and advise on the content.

- Authors’ contributions: N.T.:Writing-Original Draft Preparation N.V.:Writing- Reviewing and Editing S.T.:Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Original draft preparation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Supervision.

- Ethics approval and consent to participate: ’Not applicable’

- Consent for publication: ’Not applicable’

- Availability of data and materials: ’Not applicable’

- Clinical trial number: ’Not Applicable’

| Method name | Method type | Tokenizer strategy | Language restriction | Reversibility | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional word splitting | Rule-based tokenization | Separates words based on space and/or punctuation. | Space-separated languages | True | Natural Language |

| Conventional sentence splitting | Rule-based tokenization | Separates sentences based on full stops. | Full-stop separated languages | True | Natural Language |

| Penn TreeBank | Rule-based tokenization | Separates contracted words. | Use of contracted words in the language | True | Natural Language |

| TweetTokeniser | Rule-based tokenization | Separates audio streams in the form of string into small tokens based on space and/or punctuation. | Space-separated languages | False | Natural Language |

| MWET (Multi-Word Expression) | Rule-based tokenization | Processes tokenized set and merges MWE into single tokens. | Needs predefined tokens. | True | Natural Language |

| TextBlob | Rule-based tokenization | Separates text into tokens based on space, punctuation, and/or tabs. | None | True | Natural Language |

| spaCy | Rule-based tokenization | Separates text(various languages) into words based on space. | Space-separated languages | True | Natural Language |

| GenSim | Rule-based tokenization | Separates text based on space and/or punctuation. | Contracted words | True | Natural Language |

| Keras tokenizer | Rule-based tokenization | Separates text into integer sequence or vector that has a coefficient for each token | None | False | Natural Language |

| Moses | Rule-based tokenization | Separates text based on spaces. | Space-separated languages | True | Natural Language |

| MeCab | Sequence segmentation | Segments sentences into their parts of speech. | None | False | Natural Language |

| KyTea | Sequence segmentation | Segments sentences into their parts of speech and pronunciation tags. | None | False | Natural Language |

| Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) | Sequence segmentation (requires pre-tokenized input) | Recodes sequences into a standardized format by frequency. | None | False | Natural Language |

| Wordpiece | Sequence segmentation (requires pre-tokenized input) | Recodes sequences into a standardized format by likelihood. Variant of BPE | None | False | Natural Language |

| Unigram | Sequence segmentation (requires pre-tokenized input) | Recodes sequences into a standardized format by likelihood, producing a set of tokens and their probabilities. Variant of BPE | None | False | Natural Language |

| SentencePiece | Data-driven tokenization | Empirically derives tokens by sequence segmentation with BPE or its variants i.e. WordPiece, Unigram. | None | True | Natural Language |

| k-mers | Rule-based tokenization | Sequence data is split into tokens of fixed length | None | False | Biology |

| Khmer | Rule-based tokenization | Sequences are arbitrarily split into subsequences. | None | False | Biology |

| Tab | Rule-based tokenization | Separates text based on tabs between them. | Tab-separated text | True | Natural Language |

References

- Aburass S, Dorgham O, Al Shaqsi J (2024) A hybrid machine learning model for classifying gene mutations in cancer using lstm, bilstm, cnn, gru, and glove. Systems and Soft Computing 6:200110.

- Asgari E, Mofrad MR (2015) Continuous distributed representation of biological sequences for deep proteomics and genomics. PloS one 10(11):e0141287.

- Bhandari N, Khare S, Walambe R, et al (2021) Comparison of machine learning and deep learning techniques in promoter prediction across diverse species. PeerJ Computer Science 7:e365.

- Chen T, Tyagi N, Chauhan S, et al (2023) genomicbert and data-free deep-learning model evaluation. bioRxiv pp 2023–05.

- Chen W, Lei TY, Jin DC, et al (2014) Pseknc: a flexible web server for generating pseudo k-tuple nucleotide composition. Analytical biochemistry 456:53–60.

- Cui H, Wang C, Maan H, et al (2024) scgpt: toward building a foundation model for single-cell multi-omics using generative ai. Nature Methods pp 1–11.

- Du J, Jia P, Dai Y, et al (2019) Gene2vec: distributed representation of genes based on co-expression. BMC genomics 20:7–15.

- Ejigu GF, Jung J (2020) Review on the computational genome annotation of sequences obtained by next-generation sequencing. Biology 9(9):295.

- Heinzinger M, Elnaggar A, Wang Y, et al (2019) Modeling aspects of the language of life through transfer-learning protein sequences. BMC bioinformatics 20:1–17.

- Huang K, Altosaar J, Ranganath R (2019) Clinicalbert: Modeling clinical notes and predicting hospital readmission. arXiv preprint arXiv:190405342.

- Ji Y, Zhou Z, Liu H, et al (2021) Dnabert: pre-trained bidirectional encoder representations from transformers model for dna-language in genome. Bioinformatics 37(15):2112–2120.

- Jin Q, Yang Y, Chen Q, et al (2024) Genegpt: Augmenting large language models with domain tools for improved access to biomedical information. Bioinformatics 40(2):btae075.

- Lee J, Yoon W, Kim S, et al (2020) Biobert: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 36(4):1234–1240.

- Liu D, Xu C, He W, et al (2021) Autogenome: an automl tool for genomic research. Artificial Intelligence in the Life Sciences 1:100017.

- Luo R, Sun L, Xia Y, et al (2022) Biogpt: generative pre-trained transformer for biomedical text generation and mining. Briefings in bioinformatics 23(6):bbac409.

- Mao Y, Zhang L, Zhang Z, et al (2019) Operon identification by combining cluster analysis, genetic algorithms, and next sentence prediction models. Nucleic Acids Research 47(13):e85.

- Mu X, Wang Y, Duan M, et al (2021) A novel position-specific encoding algorithm (seqpose) of nucleotide sequences and its application for detecting enhancers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22(6):3079.

- Ng P (2017) dna2vec: Consistent vector representations of variable-length k-mers. arXiv preprint arXiv:170106279.

- Potdar K, Pardawala TS, Pai CD (2017) A comparative study of categorical variable encoding techniques for neural network classifiers. International journal of computer applications 175(4):7–9.

- Pourmirzaei M, Esmaili F, Pourmirzaei M, et al (2024) Prot2token: A multi-task framework for protein language processing using autoregressive language modeling. bioRxiv pp 2024–05.

- Ren R, Yin C, S.-T. Yau S (2022) kmer2vec: A novel method for comparing dna sequences by word2vec embedding. Journal of Computational Biology 29(9):1001–1021.

- Sanabria M, Hirsch J, Joubert PM, et al (2024) Dna language model grover learns sequence context in the human genome. Nature Machine Intelligence pp 1–13.

- Sharma S, Daniel Jr R (2019) Bioflair: Pretrained pooled contextualized embeddings for biomedical sequence labeling tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:190805760.

- Tahmid MT, Shahgir HS, Mahbub S, et al (2024) Birna-bert allows efficient rna language modeling with adaptive tokenization. bioRxiv pp 2024–07.

- Wade KE, Chen L, Deng C, et al (2024) Investigating alignment-free machine learning methods for HIV-1 subtype classification. Bioinformatics Advances 4(1):vbae108. https://doi.org/#1, URL https://doi.org/10.1093/bioadv/vbae108.

- Wahab A, Tayara H, Xuan Z, et al (2021) Dna sequences performs as natural language processing by exploiting deep learning algorithm for the identification of n4-methylcytosine. Scientific reports 11(1):212.

- Wang H, Liu H, Huang T, et al (2022) Emdlp: Ensemble multiscale deep learning model for rna methylation site prediction. BMC bioinformatics 23(1):221.

- Wu F, Yang R, Zhang C, et al (2021) A deep learning framework combined with word embedding to identify dna replication origins. Scientific reports 11(1):844.

- Yang KK, Wu Z, Bedbrook CN, et al (2018) Learned protein embeddings for machine learning. Bioinformatics 34(15):2642–2648.

- Yu X, Hu W, Lu S, et al (2019) Biobert based named entity recognition in electronic medical record. In: 2019 10th international conference on information technology in medicine and education (ITME), IEEE, pp 49–52.

- Zhang D, Zhang W, He B, et al (2023) Dnagpt: a generalized pretrained tool for multiple dna sequence analysis tasks. bioRxiv pp 2023–07.

- Zhang L, Li G, Li X, et al (2021) Edlm6apred: ensemble deep learning approach for mrna m6a site prediction. BMC bioinformatics 22(1):288.

- Zhou Z, Ji Y, Li W, et al (2023) Dnabert-2: Efficient foundation model and benchmark for multi-species genome. arXiv preprint arXiv:230615006.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).