Submitted:

07 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

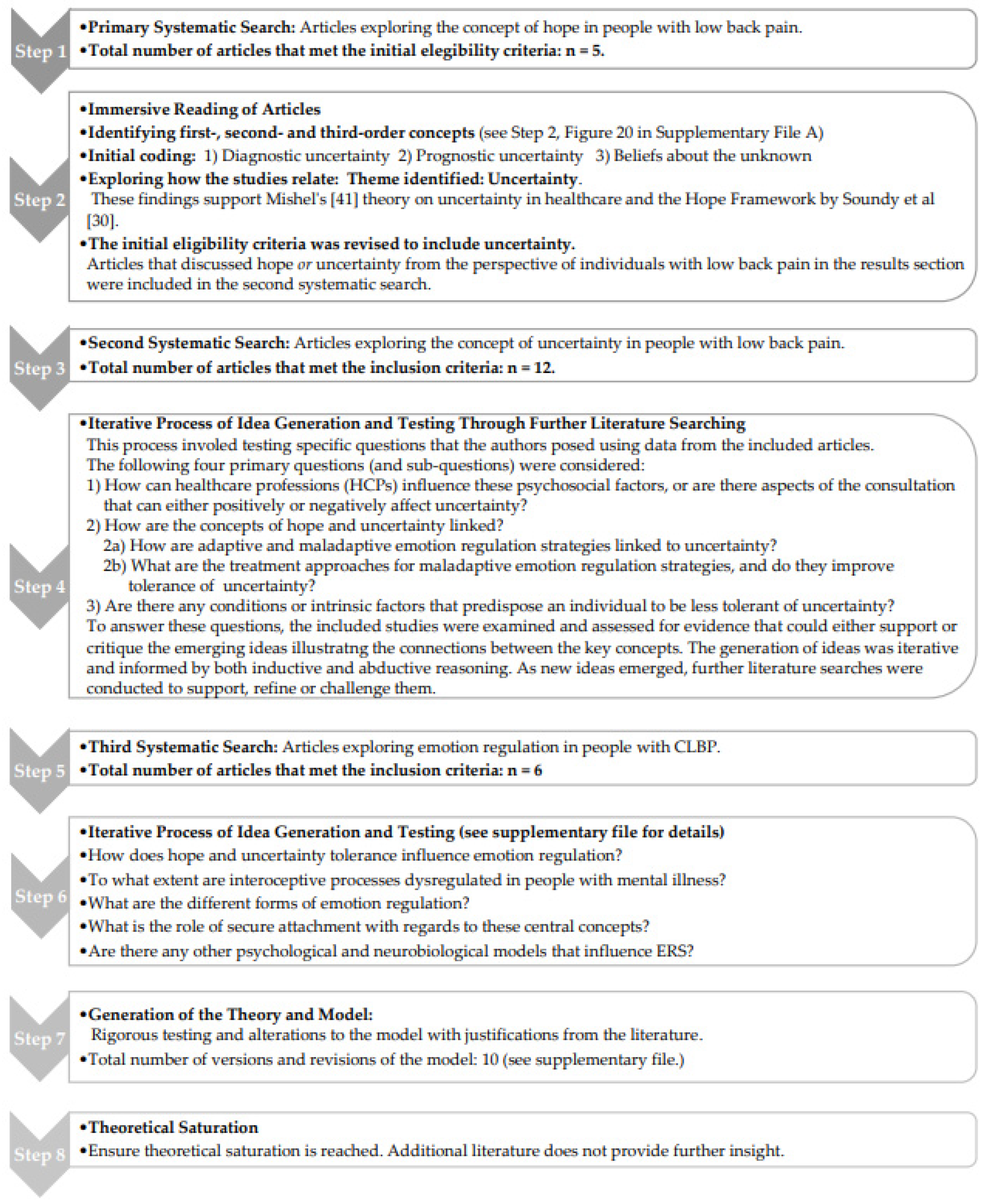

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Initial Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy for Qualitative Literature

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction Approach

2.5. Quality of Included Articles

2.6. Generalisability of Results and Searching for Conceptual Models That May Assisst Analytical Generalisbility

2.7. Synthesis

3. Results

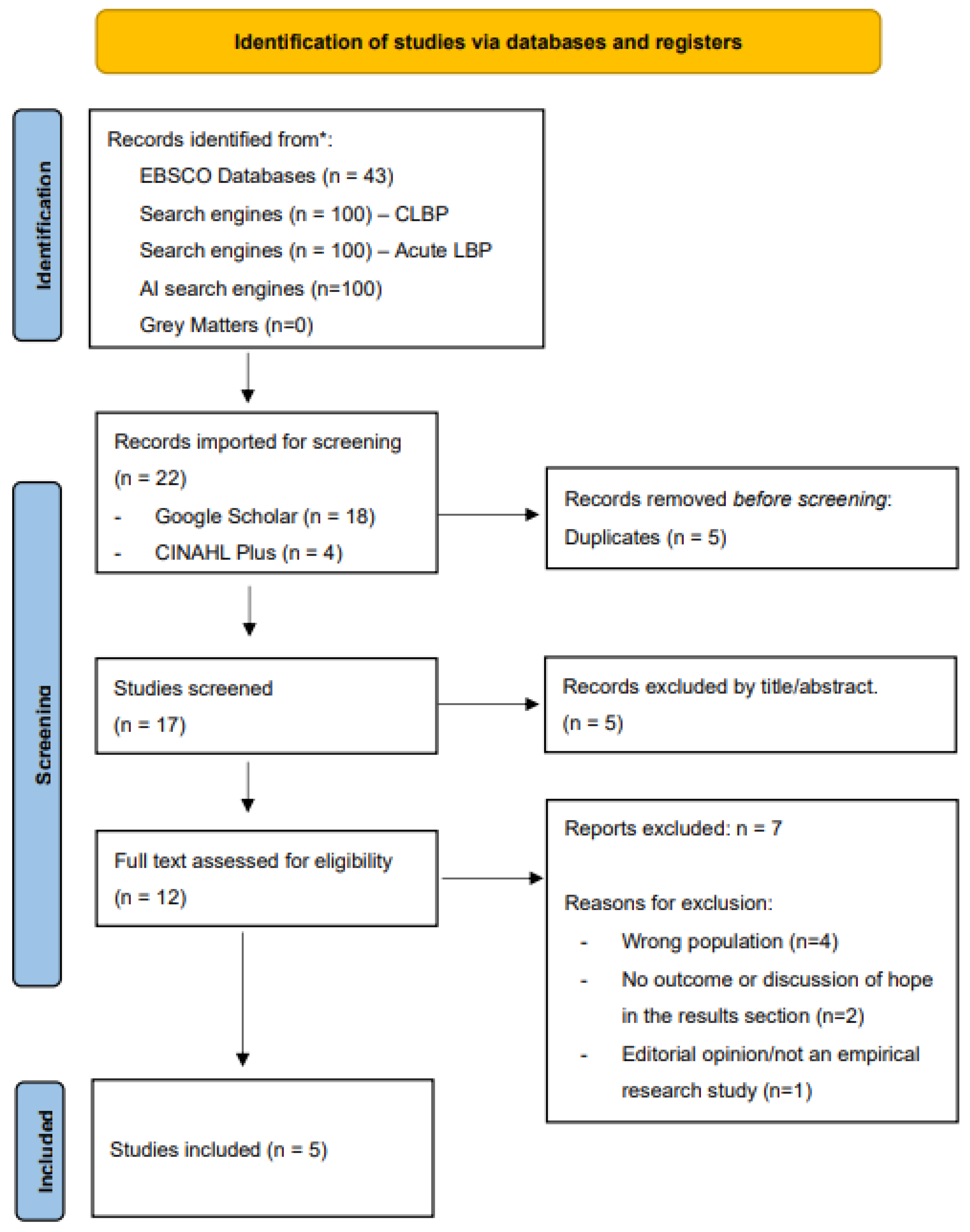

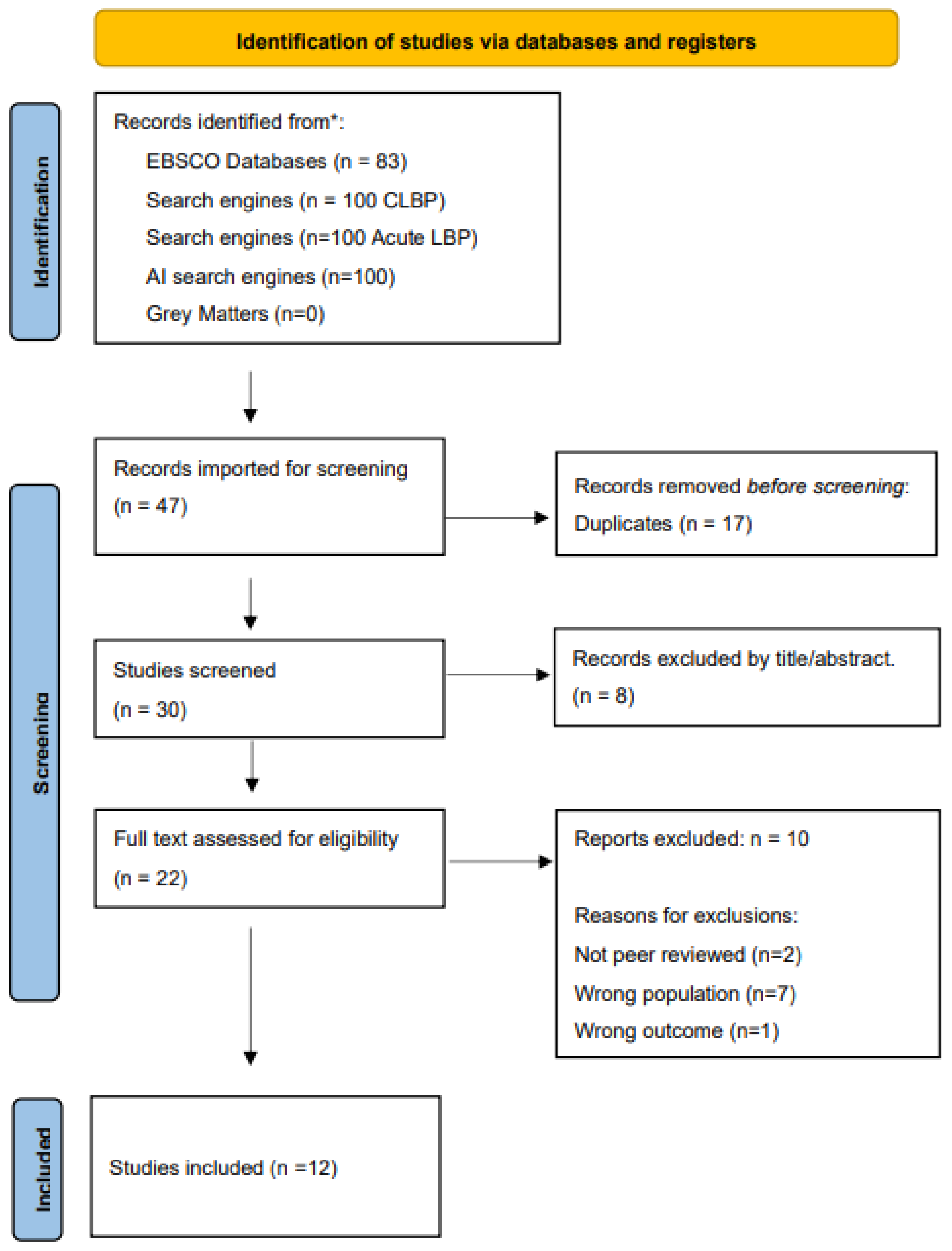

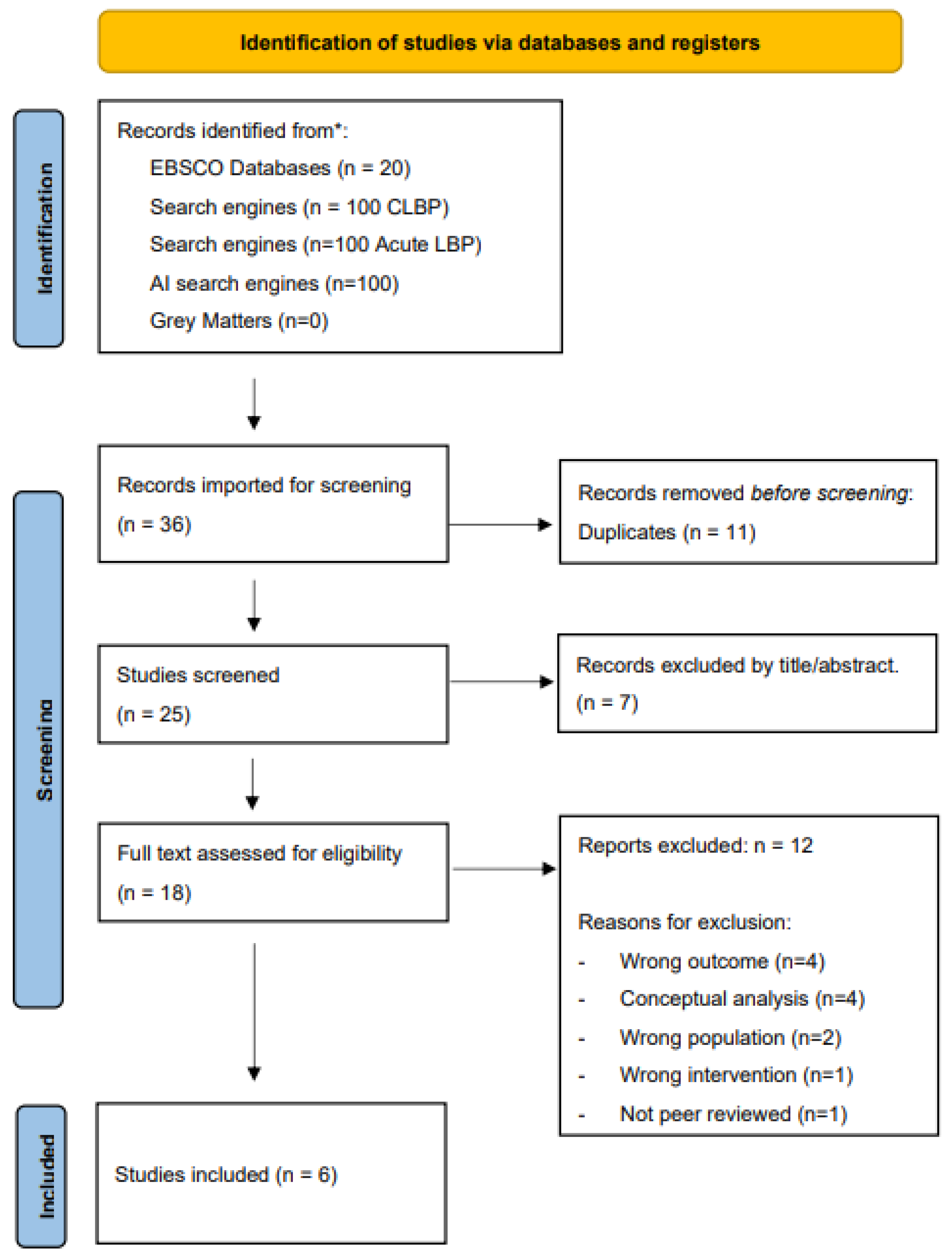

3.1. Search Outputs

| Article | Country | Gender | Age | Ethnicity of sample | Time with condition (LBP) | Methodology |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corbett, M., Foster, N. and Ong, B. (2007) [16] | UK (Keele University) |

Male | 15 | Range: 19-59 years Mean: Not stated. |

Unknown/not reported | 12+ weeks | Semi-Structured Interviews |

| Female | 22 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Madsen et al. (2024) [34] |

Denmark |

Male | 8 | Range: 28-79 years Mean: Not stated. |

Unknown/not reported | Any duration of non-specific LBP – the study did not restrict inclusion based on pain duration, nor specify exact duration for each participant. | Semi-structured Interviews pre- and post-consultation. Setting: Primary Care |

| Female | 10 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Stensland, M. (2021) [31] | USA | Male | 8 | Range: 66-83 years Mean: 56 years |

Non-Hispanic Caucasian |

12+ weeks | Semi structured 1:1 interviews |

| Female | 13 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Toye and Barker (2012) [15] |

UK (Oxford) | Male | 7 | Range: 29-67 years Mean: 52 years |

Unknown/not reported | 3-23 years | Semi-structured interviews (before, after, and 1-year follow-up). |

| Female | 13 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Wojtnya, E., Palt, L. & Popiolek, K. (2015) [43] |

Poland | Male | 78 | Range: Not stated. Mean: 50.45 years |

Unknown/not reported | 1+ year | Cross sectional study |

| Female | 72 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Article | Country | Gender | Age | Ethnicity of sample | Time with condition (CLBP) | Methodology |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amja et al. (2021) [44] | Canada |

Male | 10 | Range: 26-67 years Mean: 49.3 years. |

Unknown/not reported | 5+ years (n=16) 1-5 years (n=6) |

Semi-structured interviews (via phone or video call). |

| Female | 12 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Benjaminsson et al. (2007) [45] |

Sweden | Male | 7 | Range: 15-64 years Mean: 36 years. |

15 participants were born in Sweden 1 participant was born in Morocco 1 participant was born in Ethiopia |

Range: 6 months – 30 years. Median duration: 8years. |

Semi-structured interviews |

| Female | 10 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Bowman, J (1994) [46] | USA | Male | 9 | Range: 27-70 years Mean: Not stated. |

Unknown/not reported | All participants had CLBP (>3months), but the exact duration for each participant was not specified. | Semi-structured interviews |

| Female | 6 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Bunzli et al. (2015) [47] | Australia | Male | 11 | Range: 19-64 years Mean: 42 years |

Unknown/not reported | Range: 6 months – 29 years. Median duration: 7years. |

Semi-structured interviews |

| Female | 25 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Costa et al. (2023) [17] |

Australia | Male | 5 | Range: 21-75 years Mean: 42 years |

Caucasian: 9 Latino: 2 Asian: 1 Mixed: 3 |

2-5 years (n=5) >5 years (n=10) |

Semi-structured interviews |

| Female | 10 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Costa et al. (2023) [3] |

Australia | Male | 16 | Range: 19-85 years Mean: Not stated. |

Unknown/not reported | <3 months: 4.6% 3 months to 1 year: 6.1% 13 months to 5 years: 10.8% 6–10 years: 13.9% 11–20 years: 29.2% Over 20 years: 30.8% |

Ethnographic observations. |

| Female | 49 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Fishbain et al. (2010) [48] | USA | Male | 149 | Range: 19-65 years Mean: 39.8 years |

White: 81.8% Black: 7.4% Asian: 0.3% Native American: 3.9% Hispanic: 6.3% Other/Unknown: = 1.8% |

>3months | Quantitative research design involving a retrospective chart review. |

| Female | 192 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Lillrank, A. (2003) [49] | Finland | Male | 0 | Range: 20-66 years Mean: Not stated. |

Unknown/not reported | >3months | Qualitative: Narrative analysis |

| Female | 30 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Makris et al. (2017) [50] | USA | Male |

30 | All >65 Years Mean: 83 years |

Caucasian: 51% African American: 37% Hispanic: 11% Other/multiracial: 10% |

5-10 years 26% >10years 55% |

Semi-structured interviews |

| Female | 63 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Osborn & Smith (1998) [51] |

UK | Male | 3 | Range: 32-53 years Mean: 45 years |

White | 6-18 years | Semi-structured interviews |

| Female | 2 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Serbic et al. (2016) [52] | UK | Male | 129 | All were >18 years. Range not stated. Mean: 49.03 years |

Unknown/not reported | >3months | Cross sectional study |

| Female | 284 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Stewart et al. (2012) [53] |

Canada | Male | 10 | Range: 22-63 years Mean: 47.7 years |

Unknown/not reported | 3-6months | Semi-structured interviews. |

| Female | 8 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Article | Country | Gender | Age | Ethnicity of sample | Time with condition (LBP) | Methodology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gerhart et al. (2020) [54] |

USA | Male | 53 | Range: 18-70 years Mean: 46.3 years |

Caucasian: 80% (n = 84) African American: 15.2% (n = 16) Hispanic: 4.8% (n = 5) |

All participants had LBP for a minimum 6 months. Average duration: 9.04 years |

Cross sectional study |

| Female | 51 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Le Borgne et al. (2017) [55] | France | Male | 120 | Range: 21-61 years. Mean: 41.74 years |

Unknown/not reported | <1year (n=25) 1-5 years (n=107) >5years (n=124) |

Semi-structured interviews |

| Female | 136 | ||||||

| Unknown |

0 | ||||||

| Moldovan et al. (2009) [56] | Romania | Male | 17 | Range: 27-84 years Mean: 50 years |

Unknown/not reported | Acute LBP (n=15) Chronic LBP (n=31) *Chronicity duration was not explicitly stated. |

Cross sectional study |

| Female | 29 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Montano et al. (2025) [57] |

Spain | Male | 15 | Range: 21-64 years Mean: 49.2 years. |

Unknown/not reported | 12-80 weeks Mean duration: 46.5 weeks |

Semi-structured interviews |

| Female | 39 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Thomas et al. (2024) [58] |

USA | Male | 86 | Range: 18-80 years Mean: 44.05 years |

Non-Hispanic Black: n=115 (62.5%) Non-Hispanic White: n=69 (37.5%) |

3 to 6 months: 4.4% 6 months to 1 year: 6.6% 1 to 3 years: 16.9% 3 to 5 years: 18.6% 5 to 10 years: 23.5% 10 to 20 years: 13.0% Over 20 years: 7.1% |

Cross sectional study |

| Female | 97 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

| Yang & Mischkowski (2024) [59] |

USA | Male |

10 | All 18+ years. Range not detailed. Mean: 36.9 years |

Caucasian American: 74.0% African American: 14.0% Asian/Asian American: 2.9% American Indian/Alaskan Native: 0.8% Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander: 0.4% Other race: 7.4% Hispanic/Latino (across all races): 6.6% Non-Hispanic: 93.0% |

>3 months | Cross sectional study |

| Female | 22 | ||||||

| Unknown | 0 | ||||||

Quality Considerations

| Quality scores for originally included empirical studies exploring the concept of hope: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article | (a) Are considerations and information given by the selected articles made sufficiently well so that concepts can be translated? | (b) Do findings provide a context for the culture, environment, and setting? | c) Are the findings relevant and useful given the focus or aims of the analysis now? | d) Do the questions asked or aims from the paper selected align to those sought by the meta-ethnographer? | (e) To what extent do the findings give theoretical insight and context of interpretation made? |

| Corbett, Foster, and Ong(2007) [16] |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Madsen et al., (2024) [34] |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Stensland (2021) [31] |

Yes | Partially – Limited ethnic diversity. Focus was on a specific geographical location/population. | Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Toye and Barker (2012) [15] |

Yes | Yes |

Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Wojtnya, Palt, and Popiolek. (2015) [43] |

Yes | Partially – Cultural context is not deeply explored. |

Yes |

Yes | Moderate - large extent |

|

Quality scores for originally included empirical studies exploring the concept of uncertainty: | |||||

| Amja et al. (2021) [44] | Yes | Yes |

Yes | Yes | To some extent – Focused on living with pain during COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Benjaminsson et al. (2007) [45] | Yes | Partially – Cultural context is not deeply explored. |

Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Bowman (1994) [46] | Yes | Yes |

Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Bunzli et al. (2015) [47] | Yes | Yes |

Yes | Yes | Moderate - large extent |

| Costa et al. (2023) [17] | Yes | Yes |

Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Costa et al. (2023) [3] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Fishbain et al. (2010) [48] | Yes | Yes |

Yes | Yes | Moderate extent |

| Lillrank. (2003) [49] |

Yes | Yes |

Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Makris et al. (2017) [50] |

Yes | Yes |

Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Osborn and Smith. (1998) [51] |

Yes | Yes |

Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Serbic et al. (2016) [52] | Yes | Yes |

Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Stewart et al. (2012) [53] |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate extent – The focus was on returning to work, but the categories of percieved uncertainty are highly relavent and in keeping with our broader findings. |

| Quality scores for originally included empirical studies exploring the concept of emotion regulation: | |||||

| Gerhart et al. (2020) [54] |

Yes | Partially – moderate detail. Does not deeply explore broader sociocultural influences. | Yes | Yes | To some extent |

| Le Borgne et al. (2017) [55] | Yes | Partially – Adequate environmental context provided but ethnic or cultural background not discussed. | Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Moldovan et al. (2009) [56] | Yes | Partially – cultural norms and environmental context is not discussed |

Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Montano et al. (2025) [57] |

Yes | Partially – Cultural references not deeply analysed. | Yes | Yes | Moderate – large extent |

| Thomas et al. (2024) [58] |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

| Yang and Mischkowski (2024) [59] |

Yes | Partially - Sociocultural influences not deeply explored. |

Yes | Yes | To a large extent |

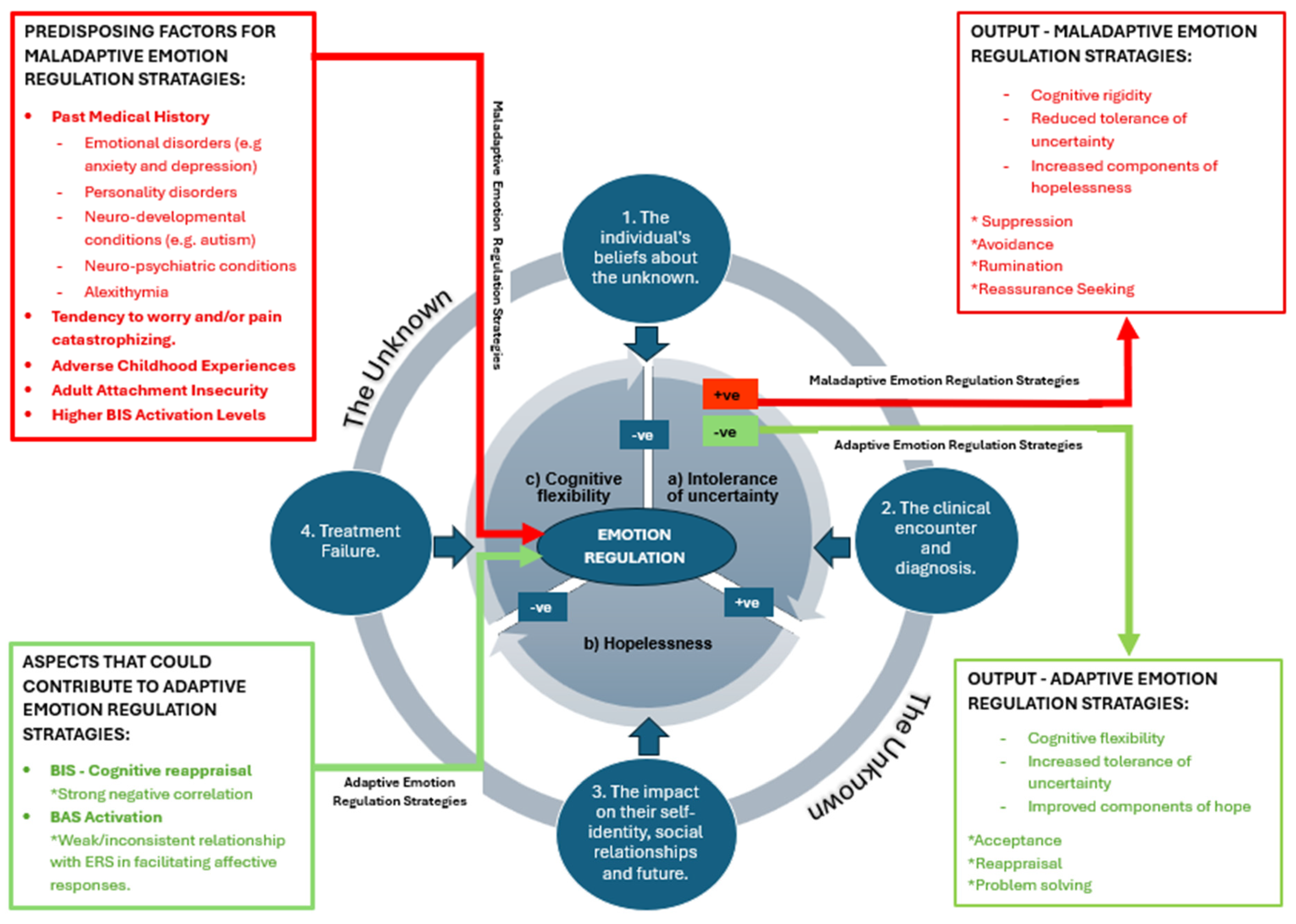

3.4. Proposed Substantive Theory

3.4.1. The Core Inter-Related Processes of Hopelessness, Cognitive Flexibility, and Intolerance of Uncertainty

3.4.1.1. Intolerance of Uncertainty

3.4.1.2. Hopelessness

3.4.1.3. Cognitive Flexibility

3.4.2. Emotional Regulation Strategies That Influence the Core Process of Emotional Regulation

3.4.2.1. Predisposing Factors for Maladaptive ERS

3.4.2.2. Aspects That Could Contribute to an Adaptive ERS

3.4.3. The Outer Rim and Named ‘Unknowns’ Identified by People with CLBP

3.4.3.1. Their Beliefs About the Unknown

3.4.3.2. The Clinical Encounter and Diagnosis

3.4.3.3. The Impact on Self-Identity, Social Relationships, and the Future

3.4.3.4. Treatment Failure

3.4.4. The Model Output and Resultant ERS

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Recommendations

- Building an effective therapeutic relationship, founded on trust, openness, and honesty.

- Conducting a thorough exploration—not only of the patient’s medical history but also sensitively exploring whether they may have been affected by adverse childhood experiences and determining their attachment orientation.

- Exploring the patient’s beliefs about the unknown, including their perceptions of pain, worries or concerns about living with a chronic condition, and gaining a deeper understanding of their self-identities—while remaining open to other possible psychosocial factors not captured in this study.

4.2. Clinical Implications for Screening

- Cognitive Flexibility Scale [92]: A 12-item measure using a 6-point Likert scale to assess an individual’s ability to adapt thinking and consider alternative solutions.

- Model of Emotions, Adaptation and Hope (MEAH) [28]: A 5-item scale designed to identify an individual’s most significant named challenge. It can be administered in approximately 30 seconds. The hope item is particularly useful for identifying experiences of uncertainty, possibility, and hopelessness.

- Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale – Short Form [93]: A 5-item measure that efficiently screens for intolerance of uncertainty.

- Emotion Regulation Questionnaire [94]: A 10-item scale assessing two key strategies—cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression—for clinicians seeking a deeper understanding of emotion regulation.

4.3. Clinical Implications for Therapy

- MEAH-based therapeutic conversations [28]: These can be delivered in 10- or 30-minute formats by trained rehabilitation therapists (training available online in under an hour). The MEAH tool serves as a foundation for exploring emotional adaptation and fostering hope. The extended version may be particularly useful, as it considers social identity, relationships, and meaningful hopes as part of a structured conversation.

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) [67]: Focuses on improving cognitive flexibility and helping individuals accept and embrace feelings and thoughts while committing to action. It is effective in improving social and physical functioning, enhancing mood, and lowering pain.

- Emotional Awareness and Expression Therapy [95]: Helps individuals process and express avoided emotions, particularly those linked to trauma or chronic pain.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) [96]: Offers structured skills training in emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and mindfulness, and has shown effectiveness in chronic pain populations.

4.4. Future Research

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ge L, Pereira MJ, Yap CW, Heng BH. Chronic low back pain and its impact on physical function, mental health, and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study in Singapore. Sci Rep. 2022;12:20040. [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Ibáñez E, Ramírez-Maestre C, López-Martínez AE, Esteve R, Ruiz-Párraga GT, Jensen MP. Behavioral inhibition and activation systems and emotional regulation in individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:394. [CrossRef]

- Costa N, Olson R, Mescouto K, Hodges PW, Dillon M, Evans K, Walsh K, Jensen N, Setchell J. Uncertainty in low back pain care – insights from an ethnographic study. Disabil Rehabil. 2023;45:784–795.

- Hayden JA, Cartwright JL, Riley RD, van Tulder MW. Exercise therapy for chronic low back pain: protocol for an individual participant data meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2012;1:64. [CrossRef]

- Keller A, Hayden J, Bombardier C, van Tulder M. Effect sizes of non-surgical treatments of non-specific low-back pain. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:1776–1788. [CrossRef]

- Moseley GL, Flor H. Targeting cortical representations in the treatment of chronic pain: a review. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012;26:646–652. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management [NG59]. London: NICE; 2016. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59/resources/endorsed-resource-national-pathway-of-care-for-low-back-and-radicular-pain-4486348909 (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Chronic pain (primary and secondary) in over 16s: assessment of all chronic pain and management of chronic primary pain [NG193]. London: NICE; 2021. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng193 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Steffens D, Maher C, Pereira L, Stevens M, Oliveira V, Chapple M, Teixeira-Salmela L, Hancock M. Prevention of low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:199–208. [CrossRef]

- Soundy A, Lim JY. Pain perceptions, suffering and pain behaviours of professional and preprofessional dancers towards pain and injury: a qualitative review. Behav Sci. 2023;13(3):268. [CrossRef]

- Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S, Keefe FJ, Mogil JS, Ringkamp M, Sluka KA, Song XJ, Stevens B, Sullivan MD, Tutelman PR, Ushida T, Vader K; IASP Presidential Task Force. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020 Sep 1;161(9):1976–1982. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Freeston M, Komes J. Revisiting uncertainty as a felt sense of unsafety: The somatic error theory of intolerance of uncertainty. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2023;79:101827. [CrossRef]

- Carleton RN. Into the unknown: a review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. J Anxiety Disord. 2016;39:30–43. [CrossRef]

- Choi JW, So WY, Kim K. The mediating effects of social support on the relationship between uncertainty and quality of life among patients with chronic low back pain: a cross-sectional survey. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10:1805. [CrossRef]

- Toye F, Barker K. “I can’t see any reason for stopping doing anything, but I might have to do it differently” – restoring hope to patients with persistent non-specific low back pain: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:894–903.

- Corbett M, Foster N, Ong B. Living with low back pain: stories of hope and despair. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:1584–1594. [CrossRef]

- Costa N, Butler P, Dillon M, Mescouto K, Olson R, Forbes R, Setchell J. “I felt uncertain about my whole future” – a qualitative investigation of people’s experiences of navigating uncertainty when seeking care for their low back pain. Pain. 2022;164:2749–2758.

- Gross JJ, Feldman-Barrett L. Emotion generation and emotion regulation: one or two depends on your point of view. Emot Rev. 2011;3:8–16. [CrossRef]

- Braunstein LM, Gross JJ, Ochsner KN. Explicit and implicit emotion regulation: a multi-level framework. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2017;12(10):1545–1557. [CrossRef]

- Trudel,. P., Cormier, S. (2024) Intolerance of uncertainty, pain catastrophizing, and symptoms of depression: a comparison between adults with and without chronic pain, Psychology, Health & Medicine, 29:5, 951-963. [CrossRef]

- Clark GI, Rock AJ, Clark LH, Murray-Lyon K. Adult attachment, worry and reassurance seeking: investigating the role of intolerance of uncertainty. Clin Psychol. 2020;24(3):294–305. [CrossRef]

- Carleton RN. The intolerance of uncertainty construct in the context of anxiety disorders: theoretical and practical perspectives. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12:937–947. [CrossRef]

- Sandhu T, Xiao B, Lawson R. Transdiagnostic computations of uncertainty: towards a new lens on intolerance of uncertainty. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2023;148:105123. [CrossRef]

- Ouellet C, Langlois F, Provencher MD, Gosselin P. Intolerance of uncertainty and difficulties in emotion regulation: proposal for an integrative model of generalized anxiety disorder. Eur Rev Appl Psychol. 2019;69:9–18. [CrossRef]

- Mauss IB, Bunge SA, Gross JJ. Automatic emotion regulation. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2007;1(1):146–167. [CrossRef]

- Koechlin H, Coakley R, Schechter N, Werner C, Kossowsky J. The role of emotion regulation in chronic pain: a systematic literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2018;107:38–45. [CrossRef]

- Soundy A, Stubbs B, Freeman P, Roskell C. Factors influencing patients’ hope in stroke and spinal cord injury: a narrative review. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2014;21(5):210–218. [CrossRef]

- Soundy, A. Harnessing hope in managing chronic illness: a guide to therapeutic rehabilitation. 1st ed. London (UK): Routledge; 2025.

- TenHouten, W. The emotions of hope: from optimism to sanguinity, from pessimism to despair. Am Sociol. 2023;54:76–100. [CrossRef]

- Soundy A, Liles C, Stubbs B, Roskell C. Identifying a framework for hope in order to establish the importance of generalised hopes for individuals who have suffered a stroke. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;2014:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Stensland, M. “If you don’t keep going, you’re gonna die”: helplessness and perseverance among older adults living with chronic low back pain. Gerontologist. 2021;61(6):907–916. [CrossRef]

- Katsimigos AM, O’Beirne S, Harmon D. Hope and chronic pain: a systematic review. Ir J Med Sci. 2020;190:307–312. [CrossRef]

- Or DYL, Lam CS, Chen PP, Wong HSS, Lam CWF, Fok YY, Chan SFI, Ho SMY. Hope in the context of chronic musculoskeletal pain: relationships of hope to pain and psychological distress. Pain Rep. 2021;6:e965. [CrossRef]

- Madsen SD, Stochkendahl MJ, Morsø L, Andersen MK, Hvidt EA. Patient perspectives on low back pain treatment in primary care: a qualitative study of hopes, expectations, and experiences. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024;25(1):997. [CrossRef]

- Pinto AM, Geenen R, Wager TD, Lumley MA, Häuser W, Kosek E, Ablin JN, Amris K, Branco J, Buskila D, Castelhano J, CasteloBranco M, Crofford LJ, Fitzcharles MA, LópezSolà M, Luís M, Marques TR, Mease PJ, Palavra F, Rhudy JL, Uddin LQ, Castilho P, Jacobs JWG, da Silva JAP. Emotion regulation and the salience network: a hypothetical integrative model of fibromyalgia. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2023;19(1):44–60. [CrossRef]

- Soundy, A. Social constructivist meta-ethnography: a framework construction. Int J Qual Methods. 2024;23:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Soundy A, Heneghan NR. Meta-ethnography. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2022;15(2):266–286. [CrossRef]

- Charmaz K, Thornberg R. The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18(3):258–269. [CrossRef]

- Campbell R, Pound P, Morgan M, Daker-White G, Britten N, Pill R, Yardley L, Pope C, Donovan J. Evaluating meta-ethnography: systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(43). [CrossRef]

- Lewis J, Ritchie J, Ormston R, Morrell G. Generalising from qualitative research. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, McNaughton Nicholls C, Ormston R, editors. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. 2nd ed. London (UK): Sage Publications Ltd.; 2013.

- Mishel, MH. Uncertainty in illness. J Nurs Scholarsh. 1988;20(4):225–232. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Wojtyna E, Palt L, Popiolek K. From Polyanna syndrome to Eeyore’s Corner? Hope and pain in patients with chronic low back pain. Pol Psychol Bull. 2015;46(1):96–103.

- Amja K, Vigouroux M, Pagé MG, Hovey RB. The experiences of people living with chronic pain during a pandemic: “Crumbling dreams with uncertain futures”. Qual Health Res. 2021 Sep;31(11):2019–28. [CrossRef]

- Benjaminsson O, Biguet G, Arvidsson I, Nilsson-Wikmar L. Recurrent low back pain: relapse from a patient perspective. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39(8):640–645. [CrossRef]

- Bowman JM. Experiencing the chronic pain phenomenon: a study. Rehabil Nurs. 1994 MarApr;19(2):91–5. [CrossRef]

- Bunzli S, Smith A, Schütze R, O’ Sullivan P. Beliefs underlying painrelated fear and how they evolve: a qualitative investigation in people with chronic back pain and high painrelated fear. BMJ Open. 2015 Oct;5(10):e008847. [CrossRef]

- Fishbain DA, Bruns D, Disorbio JM, Lewis JE, Gao J. Exploration of the illness uncertainty concept in acute and chronic pain patients vs community patients. Pain Med. 2010 May;11(5):658–69. [CrossRef]

- Lillrank A. Back pain and the resolution of diagnostic uncertainty in illness narratives. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(6):1045–1054. [CrossRef]

- Makris UE, Higashi RT, Marks EG, Fraenkel L, Gill TM, Friedly JL, Reid MC. Physical, emotional, and social impacts of restricting back pain in older adults: A qualitative study. Pain Med. 2017;18(7):1225–1235. [CrossRef]

- Osborn M, Smith JA. The personal experience of chronic benign lower back pain: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Br J Health Psychol. 1998 Mar;3(1):65–83. [CrossRef]

- Serbic D, Pincus T, Fife-Schaw C, Dawson H. Diagnostic uncertainty, guilt, mood, and disability in back pain. Health Psychol. 2016 Jan;35(1):50–59. [CrossRef]

- Stewart AM, Polak E, Young R, Schultz IZ. Injured workers’ construction of expectations of return to work with subacute back pain: the role of perceived uncertainty. J Occup Rehabil. 2012 Mar;22(1):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Gerhart J, Burns JW, Post KM, Smith DA, Porter LS, Burgess HJ, et al. Relationships of negative emotions and chronic low back pain to functioning, social support, and received validation. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(2):173–179. [CrossRef]

- Le Borgne M, Boudoukha AH, Petit A, Roquelaure Y. Chronic low back pain and the transdiagnostic process: How do cognitive and emotional dysregulations contribute to the intensity of risk factors and pain? Scand J Pain. 2017;17:309–15. [CrossRef]

- Moldovan AR, Onac IA, Vantu M, Szentagotai A, Onac I. Emotional distress, pain catastrophizing and expectancies in patients with low back pain. J Cogn Behav Psychother. 2009;9(1):83–93.

- Montaño JJ, Gervilla E, Jiménez R, Sesé A. From acute to chronic low back pain: the role of negative emotions. Psychol Health Med. 2025 Mar 27;1–14. [CrossRef]

- Thomas JS, Goodin BR. Adverse childhood experiences and chronic low back pain: Recent insights and implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2024;157:105427.

- Yang Q, Mischkowski D. Understanding pain communication: Current evidence and future directions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2024;158:105444.

- Zhou T, Salman D, McGregor AH. Recent clinical practice guidelines for the management of low back pain: a global comparison. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024 May 1;25:344. [CrossRef]

- Neville A, Kopala-Sibley DC, Soltani S, Asmundson GJG, Jordan A, Carleton RN, Yeates KO, Schulte F, Noel M. A longitudinal examination of the interpersonal fear avoidance model of pain: the role of intolerance of uncertainty. Pain. 2021;162(1):152–160.

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: an integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. p. 46–76.

- Wu Q, Xu L, Wan J, Yu Z, Lei Y. Intolerance of uncertainty affects the behavioral and neural mechanisms of higher generalization. Cereb Cortex. 2024 Apr;34(4):bhae153. [CrossRef]

- Leite A, Araujo G, Rolim C, Castelo S, Beilfuss M, Leao M, Castro T, Hartmann S. Hope theory and its relation to depression: a systematic review. Psychol Cogn Neurosci. 2019;2:e1014.

- Lynch, W. Images of hope: imagination as healer of the hopeless. 1st ed. Baltimore: Helicon Press; 1965.

- Vlaeyen, J. W., and Linton, S. J. (2012). Fear-avoidance model of chronic musculoskeletal pain: 12 years on. Pain 153, 1144–1147. [CrossRef]

- Demirtas AS, Yildiz B. Hopelessness and perceived stress: the mediating role of cognitive flexibility and intolerance of uncertainty. Dusunen Adam J Psychiatr Neurol Sci. 2019;32(3):259–67. [CrossRef]

- Ma TW, Yuen ASK, Yang Z. The efficacy of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Pain. 2023;38(2):85–96.

- World Health Organisation (2023). WHO guideline for non-surgical management of chronic primary low back pain in adults in primary and community care settings. World Health Organisation, Geneve. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240081789.

- Sahib A, Chen J, Cardenas D, Calear AL. Intolerance of uncertainty and emotion regulation: a meta-analytic and systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2023;101:102270. [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick S, Dixon-Gordon KL, Turner CJ, Chen SX, Chapman A. Emotion dysregulation in personality disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2023;25(5):223–231. [CrossRef]

- Mehling WE, Krause N. Are difficulties perceiving and expressing emotions associated with low-back pain? The relationship between lack of emotional awareness (alexithymia) and 12-month prevalence of low-back pain in 1180 urban public transit operators. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58(1):73–81. [CrossRef]

- White LK, McDermott JM, Degnan KA, Henderson HA, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition and anxiety: the moderating roles of inhibitory control and attention shifting. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2011 Jul;39(5):735-47. [CrossRef]

- Jensen MP, Solé E, Castarlenas E, Racine M, Roy R, Miró J, et al. Behavioral inhibition, maladaptive pain cognitions, and function in patients with chronic pain. Scand J Pain. 2017 Oct;17(1):41–48. [CrossRef]

- Pang J, Tang X, Li H, Hu Q, Cui H, Zhang L, Li W, Zhu Z, Wang J, Li C. Altered interoceptive processing in generalized anxiety disorder—a heartbeat-evoked potential research. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:616.

- Hong RY, Cheung MWL. The structure of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression and anxiety: evidence for a common core etiologic process based on a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;3(6):892–912. [CrossRef]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy. In: Ramachaudran VS, editor. Encyclopedia of human behavior. Vol. 4. New York: Academic Press; 1994. p. 71–81.

- Carroll LJ, Lis A, Weiser S, Torti J. How well do you expect to recover, and what does recovery mean, anyway? Qualitative study of expectations after a musculoskeletal injury. Phys Ther. 2016;96(6):797–807. [CrossRef]

- Spink A, Wagner I, Orrock P. Common reported barriers and facilitators for self-management in adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2021;56:102433. [CrossRef]

- Abdolghaderi M, Kafi S, Saberi A, Ariaporan S. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on hope and pain beliefs of patients with chronic low back pain. Caspian J Neurol Sci. 2018;4(12):18–23. [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.B., Aboalghasimi, S., Akbari, B. and Nadirinabi, B. The Effectiveness of Cognitive Therapy on Hope and Pain Management in Women with Chronic Pain. PCNM Journal. 2022, 12, pp. 18-23.

- Buchman DZ, Ho A, Goldberg DS. Investigating trust, expertise, and epistemic injustice in chronic pain. J Bioeth Inq. 2017;14(1):31–42. [CrossRef]

- Darlow B, Dowell A, Baxter GD, Mathieson F, Perry M, Dean S. The enduring impact of what clinicians say to people with low back pain. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(6):527–34.

- Serbic D, Pincus T. Diagnostic uncertainty and recall bias in chronic low back pain. Pain. 2014;155(8):1540–46. [CrossRef]

- Costa N, Olson R, Dillon M, Mescouto K, Butler P, Forbes R, Setchell J. Navigating uncertainty in low back pain care through an ethic of openness: learning from a post-critical analysis. Health. 2025;71(2):104–110.

- Mishel MH, Mu B. Reconceptualization of the uncertainty in illness. J Nurs Scholarsh. 1990;22(4):256–62. [CrossRef]

- Lian OS, Nettleton S, Wifstad Å, Dowrick C. Negotiating uncertainty in clinical encounters: a narrative exploration of naturally occurring primary care consultations. Soc Sci Med. 2021 Dec;291:114467. [CrossRef]

- Costa N, Mescouto K, Dillon M, Olson R, Butler P, Forbes R, Setchell J. The ubiquity of uncertainty in low back pain care. Soc Sci Med. 2022 Nov;313:115422. [CrossRef]

- Costa N, Olson R, Dillon M, Mescouto K, Butler P, Forbes R, Setchell J. Navigating uncertainty in low back pain care through an ethic of openness: learning from a post-critical analysis. Health. 2025;71(2):104–110.

- Mackintosh N, Armstrong N. Understanding and managing uncertainty in healthcare: revisiting and advancing sociological contributions. Sociol Health Illn. 2020 Jan;42(1):1–20. [CrossRef]

- Mol, A. The logic of care: Health and the problem of patient choice. London (UK): Taylor & Francis Group; 2008.

- Martin MM, Rubin RB. A new measure of cognitive flexibility. Psychol Rep. 1995;76:623-6.

- Bottesi G, Noventa S, Freeston MH, Ghisi M. A short-form version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale: Initial development of the IUS-5 [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(2):348-62. [CrossRef]

- Lumley MA, Schubiner H. Emotional awareness and expression therapy for chronic pain: Rationale, principles and techniques, evidence, and critical review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2019;21(7):1-8.

- Norman-Nott N, Briggs NE, Hesam-Shariati N, et al. Online dialectical behavioral therapy for emotion dysregulation in people with chronic pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(5):e256908. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).