Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

04 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Vaccination Procedure

2.2. Cell Suspension Obtainment

2.3. Antibody Staining, Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting

2.4. RNA Isolation and Sequencing

2.5. RNA-seq Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Bone Marrow and Spleen Immune Cell Composition Following Subcutaneous BCG Vaccination

3.2. The Transcriptomic Response of Innate Immune Cells 3 Days Following BCG Vaccination

3.2.1. RNA-seq Data Quality Assessment

3.2.2. Gene Ontology (GO) and Pathway Enrichment Analyses

3.2.3. Transcriptomic Alterations in NK Cells

3.2.4. Transcriptomic Alterations in Monocytes

3.2.5. Transcriptomic Alterations in the Non-Sorted Bone Marrow

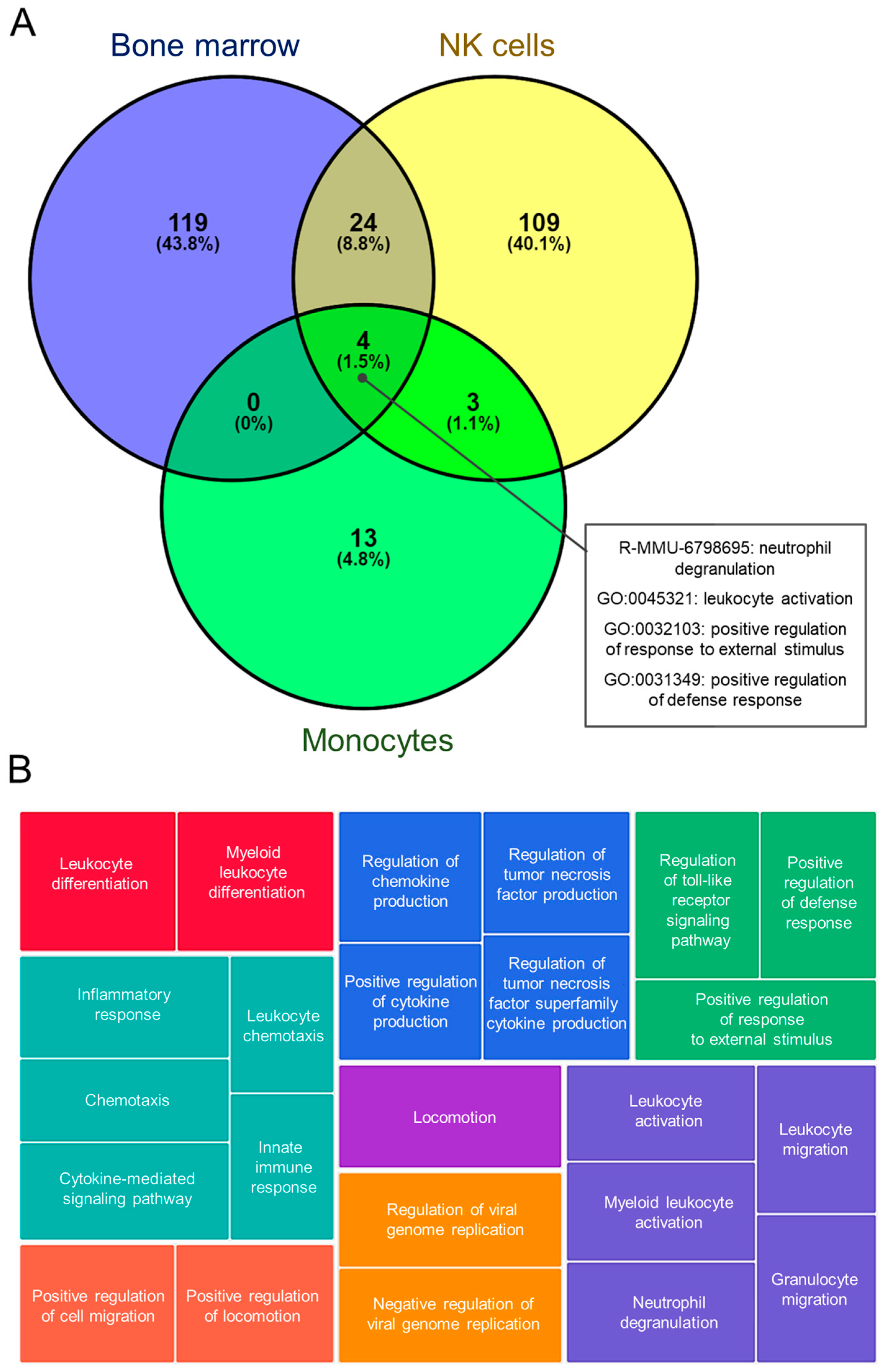

3.2.6. Analysis of Common Altered Processes

3.2.7. Immune Ligand and Receptor Analysis

4. Discussion

Bone Marrow and Spleen Immune Cell Composition

The Early Transcriptomic Response of Innate Immune Cells to BCG Vaccination

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shann, F. The Non-Specific Effects of Vaccines. Arch Dis Child 2010, 95, 662–667. [CrossRef]

- Stensballe, L.G.; Nante, E.; Jensen, I.P.; Kofoed, P.-E.; Poulsen, A.; Jensen, H.; Newport, M.; Marchant, A.; Aaby, P. Acute Lower Respiratory Tract Infections and Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Infants in Guinea-Bissau: A Beneficial Effect of BCG Vaccination for Girls. Vaccine 2005, 23, 1251–1257. [CrossRef]

- Nemes, E.; Geldenhuys, H.; Rozot, V.; Rutkowski, K.T.; Ratangee, F.; Bilek, N.; Mabwe, S.; Makhethe, L.; Erasmus, M.; Toefy, A.; et al. Prevention of M. Tuberculosis Infection with H4:IC31 Vaccine or BCG Revaccination. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 379, 138–149. [CrossRef]

- Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Tsilika, M.; Moorlag, S.; Antonakos, N.; Kotsaki, A.; Domínguez-Andrés, J.; Kyriazopoulou, E.; Gkavogianni, T.; Adami, M.-E.; Damoraki, G.; et al. Activate: Randomized Clinical Trial of BCG Vaccination against Infection in the Elderly. Cell 2020, 183, 315-323.e9. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.C.; Ganguly, R.; Waldman, R.H. Nonspecific Protection of Mice against Influenza Virus Infection by Local or Systemic Immunization with Bacille Calmette-Guerin. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1977, 136, 171–175. [CrossRef]

- Kleinnijenhuis, J.; Quintin, J.; Preijers, F.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Ifrim, D.C.; Saeed, S.; Jacobs, C.; van Loenhout, J.; de Jong, D.; Stunnenberg, H.G.; et al. Bacille Calmette-Guérin Induces NOD2-Dependent Nonspecific Protection from Reinfection via Epigenetic Reprogramming of Monocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 17537–17542. [CrossRef]

- Cirovic, B.; de Bree, L.C.J.; Groh, L.; Blok, B.A.; Chan, J.; van der Velden, W.J.F.M.; Bremmers, M.E.J.; van Crevel, R.; Händler, K.; Picelli, S.; et al. BCG Vaccination in Humans Elicits Trained Immunity via the Hematopoietic Progenitor Compartment. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 322-334.e5. [CrossRef]

- Arts, R.J.W.; Moorlag, S.J.C.F.M.; Novakovic, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.-Y.; Oosting, M.; Kumar, V.; Xavier, R.J.; Wijmenga, C.; Joosten, L.A.B.; et al. BCG Vaccination Protects against Experimental Viral Infection in Humans through the Induction of Cytokines Associated with Trained Immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 89-100.e5. [CrossRef]

- Mulder, W.J.M.; Ochando, J.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Fayad, Z.A.; Netea, M.G. Therapeutic Targeting of Trained Immunity. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019, 18, 553–566. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Lu, S.; Lowrie, D.B.; Fan, X. Trained Immunity: A Yin-Yang Balance. MedComm (Beijing) 2022, 3. [CrossRef]

- Netea, M.G. Training Innate Immunity: The Changing Concept of Immunological Memory in Innate Host Defence. Eur J Clin Invest 2013, 43, 881–884. [CrossRef]

- Kleinnijenhuis, J.; Quintin, J.; Preijers, F.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Jacobs, C.; Xavier, R.J.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; van Crevel, R.; Netea, M.G. BCG-Induced Trained Immunity in NK Cells: Role for Non-Specific Protection to Infection. Clinical Immunology 2014, 155, 213–219. [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Parasa, V.R.; Raffetseder, J.; Martis, M.; Mehta, R.B.; Netea, M.; Lerm, M. Anti-Mycobacterial Activity Correlates with Altered DNA Methylation Pattern in Immune Cells from BCG-Vaccinated Subjects. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 12305. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Saavedra-Avila, N.A.; Tiwari, S.; Porcelli, S.A. A Century of BCG Vaccination: Immune Mechanisms, Animal Models, Non-Traditional Routes and Implications for COVID-19. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.M.; Mills, K.H.G.; Basdeo, S.A. The Effects of Trained Innate Immunity on T Cell Responses; Clinical Implications and Knowledge Gaps for Future Research. Front Immunol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ge, F.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Zheng, B.; Li, W.; Chen, S.; Zheng, X.; Deng, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Mycobacterium Bovis BCG Given at Birth Followed by Inactivated Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine Prevents Vaccine-Enhanced Disease by Promoting Trained Macrophages and Resident Memory T Cells. J Virol 2023, 97. [CrossRef]

- Gillard, J.; Blok, B.A.; Garza, D.R.; Venkatasubramanian, P.B.; Simonetti, E.; Eleveld, M.J.; Berbers, G.A.M.; van Gageldonk, P.G.M.; Joosten, I.; de Groot, R.; et al. BCG-Induced Trained Immunity Enhances Acellular Pertussis Vaccination Responses in an Explorative Randomized Clinical Trial. NPJ Vaccines 2022, 7, 21. [CrossRef]

- Kleinnijenhuis, J.; Quintin, J.; Preijers, F.; Benn, C.S.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Jacobs, C.; van Loenhout, J.; Xavier, R.J.; Aaby, P.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; et al. Long-Lasting Effects of BCG Vaccination on Both Heterologous Th1/Th17 Responses and Innate Trained Immunity. J Innate Immun 2014, 6, 152–158. [CrossRef]

- Subiza, J.L.; Palomares, O.; Quinti, I.; Sánchez-Ramón, S. Editorial: Trained Immunity-Based Vaccines. Front Immunol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Théroude, C.; Reverte, M.; Heinonen, T.; Ciarlo, E.; Schrijver, I.T.; Antonakos, N.; Maillard, N.; Pralong, F.; Le Roy, D.; Roger, T. Trained Immunity Confers Prolonged Protection From Listeriosis. Front Immunol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Kleinnijenhuis, J.; Quintin, J.; Preijers, F.; Benn, C.S.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Jacobs, C.; van Loenhout, J.; Xavier, R.J.; Aaby, P.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; et al. Long-Lasting Effects of BCG Vaccination on Both Heterologous Th1/Th17 Responses and Innate Trained Immunity. J Innate Immun 2014, 6, 152–158. [CrossRef]

- Levy, O.; Wynn, J.L. A Prime Time for Trained Immunity: Innate Immune Memory in Newborns and Infants. Neonatology 2014, 105, 136–141. [CrossRef]

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize Analysis Results for Multiple Tools and Samples in a Single Report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnet J 2011, 17, 10–12. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A Fast Spliced Aligner with Low Memory Requirements. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. FeatureCounts: An Efficient General Purpose Program for Assigning Sequence Reads to Genomic Features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.; Domrachev, M.; Lash, A.E. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI Gene Expression and Hybridization Array Data Repository. Nucleic Acids Res 2002, 30, 207–210. [CrossRef]

- Kondratyeva, L.; Kuzmich, A.; Linge, I.; Pleshkan, V.; Rakitina, O.; Kondratieva, S.; Snezhkov, E.; Sass, A.; Alekseenko, I. Early Transcriptomic Response of Innate Immune Cells to Subcutaneous BCG Vaccination of Mice. BMC Res Notes 2024, 17, 253. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A.H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S.K. Metascape Provides a Biologist-Oriented Resource for the Analysis of Systems-Level Datasets. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1523. [CrossRef]

- Supek, F.; Bošnjak, M.; Škunca, N.; Šmuc, T. REVIGO Summarizes and Visualizes Long Lists of Gene Ontology Terms. PLoS One 2011, 6, e21800. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data Available online: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

- Deniset, J.F.; Surewaard, B.G.; Lee, W.-Y.; Kubes, P. Splenic Ly6Ghigh Mature and Ly6Gint Immature Neutrophils Contribute to Eradication of S. Pneumoniae. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2017, 214, 1333–1350. [CrossRef]

- Kratofil, R.M.; Kubes, P.; Deniset, J.F. Monocyte Conversion During Inflammation and Injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017, 37, 35–42. [CrossRef]

- Teh, Y.C.; Ding, J.L.; Ng, L.G.; Chong, S.Z. Capturing the Fantastic Voyage of Monocytes Through Time and Space. Front Immunol 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Brook, B.; Harbeson, D.J.; Shannon, C.P.; Cai, B.; He, D.; Ben-Othman, R.; Francis, F.; Huang, J.; Varankovich, N.; Liu, A.; et al. BCG Vaccination–Induced Emergency Granulopoiesis Provides Rapid Protection from Neonatal Sepsis. Sci Transl Med 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Caldwell, C.C.; Nomellini, V. Distinct Neutrophil Populations in the Spleen During PICS. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 804. [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, C.; Chasson, L.; Luci, C.; Tomasello, E.; Geissmann, F.; Vivier, E.; Walzer, T. The Trafficking of Natural Killer Cells. Immunol Rev 2007, 220, 169–182. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Wei, H.; Sun, R.; Tian, Z.; Peng, H. A Novel Spleen-Resident Immature NK Cell Subset and Its Maturation in a T-Bet-Dependent Manner. J Autoimmun 2019, 105, 102307. [CrossRef]

- Dokun, A.O.; Kim, S.; Smith, H.R.C.; Kang, H.-S.P.; Chu, D.T.; Yokoyama, W.M. Specific and Nonspecific NK Cell Activation during Virus Infection. Nat Immunol 2001, 2, 951–956. [CrossRef]

- Esin, S.; Batoni, G.; Pardini, M.; Favilli, F.; Bottai, D.; Maisetta, G.; Florio, W.; Vanacore, R.; Wigzell, H.; Campa, M. Functional Characterization of Human Natural Killer Cells Responding to Mycobacterium Bovis Bacille Calmette-Guérin. Immunology 2004, 112, 143–152. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; Suliman, S.; Briel, L.; Veldtsman, H.; Khomba, N.; Africa, H.; Steyn, M.; Snyders, C.I.; van Rensburg, I.C.; Walzl, G.; et al. Newborn Bacille Calmette-Guérin Vaccination Induces Robust Infant Interferon-γ-Expressing Natural Killer Cell Responses to Mycobacteria. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2023, 130, S52–S62. [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Ralph, P.; Moore, M.A.S. Suppression of Spleen Natural Killing Activity Induced by BCG. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1980, 16, 30–38. [CrossRef]

- Netea, M.G.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Latz, E.; Mills, K.H.G.; Natoli, G.; Stunnenberg, H.G.; O’Neill, L.A.J.; Xavier, R.J. Trained Immunity: A Program of Innate Immune Memory in Health and Disease. Science (1979) 2016, 352. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Aguirre-Gamboa, R.; de Bree, L.; Sanz, J.; Dumaine, A.; Joosten, L.; Divangahi, M.; Netea, M.; Barreiro, L. BCG Vaccination Impacts the Epigenetic Landscape of Progenitor Cells in Human Bone Marrow. bioRxiv [Preprint] 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ochando, J.; Mulder, W.J.M.; Madsen, J.C.; Netea, M.G.; Duivenvoorden, R. Trained Immunity — Basic Concepts and Contributions to Immunopathology. Nat Rev Nephrol 2023, 19, 23–37. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, R.B.; Santee, S.; Granger, S.W.; Butrovich, K.; Cheung, T.; Kronenberg, M.; Cheroutre, H.; Ware, C.F. Constitutive Expression of LIGHT on T Cells Leads to Lymphocyte Activation, Inflammation, and Tissue Destruction . The Journal of Immunology 2001, 167, 6330–6337. [CrossRef]

- Shih, D.Q.; Targan, S.R. Immunopathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. World J Gastroenterol 2007, 14, 390. [CrossRef]

- Herro, R.; Antunes, R.D.S.; Aguilera, A.R.; Tamada, K.; Croft, M. The Tumor Necrosis Factor Superfamily Molecule LIGHT Promotes Keratinocyte Activity and Skin Fibrosis. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2015, 135, 2109–2118. [CrossRef]

- Herro, R.; Da Silva Antunes, R.; Aguilera, A.R.; Tamada, K.; Croft, M. Tumor Necrosis Factor Superfamily 14 (LIGHT) Controls Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin to Drive Pulmonary Fibrosis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2015, 136, 757–768. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, T.D.; Wilson, E.B.; Black, E.V.I.; Benest, A. V.; Vaz, C.; Tan, B.; Tanavde, V.M.; Cook, G.P. Licensed Human Natural Killer Cells Aid Dendritic Cell Maturation via TNFSF14/LIGHT. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111. [CrossRef]

- Krause, P.; Zahner, S.P.; Kim, G.; Shaikh, R.B.; Steinberg, M.W.; Kronenberg, M. The Tumor Necrosis Factor Family Member TNFSF14 (LIGHT) Is Required for Resolution of Intestinal Inflammation in Mice. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1752-1762.e4. [CrossRef]

- Giles, D.A.; Zahner, S.; Krause, P.; Van Der Gracht, E.; Riffelmacher, T.; Morris, V.; Tumanov, A.; Kronenberg, M. The Tumor Necrosis Factor Superfamily Members TNFSF14 (LIGHT), Lymphotoxin β and Lymphotoxin β Receptor Interact to Regulate Intestinal Inflammation. Front Immunol 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, A.C.; de Labastida Rivera, F.; Haque, A.; Sheel, M.; Zhou, Y.; Amante, F.H.; Bunn, P.T.; Randall, L.M.; Pfeffer, K.; Scheu, S.; et al. Critical Roles for LIGHT and Its Receptors in Generating T Cell-Mediated Immunity during Leishmania Donovani Infection. PLoS Pathog 2011, 7, e1002279. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Song, R.; Wang, Z.; Jing, Z.; Wang, S.; Ma, J. S100A8/A9 in Inflammation. Front Immunol 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, M.; Yoon, S.; Lee, S. Role of Lymphoid Lineage Cells Aberrantly Expressing Alarmins S100A8/A9 in Determining the Severity of COVID-19. Genes Genomics 2023, 45, 337–346. [CrossRef]

- Horst, S.A.; Itzek, A.; Klos, A.; Beineke, A.; Medina, E. Differential Contributions of the Complement Anaphylotoxin Receptors C5aR1 and C5aR2 to the Early Innate Immune Response against Staphylococcus Aureus Infection. Pathogens 2015, 4, 722–738. [CrossRef]

- Gerard, N.P.; Gerard, C. The Chemotactic Receptor for Human C5a Anaphylatoxin. Nature 1991, 349, 614–617. [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wang, L.-H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.-Q.; Chen, H.-T.; Xu, J.-H.; Peng, W.; Lin, G.-W.; Wei, P.-P.; Li, B.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptome Profiling of an Adult Human Cell Atlas of 15 Major Organs. Genome Biol 2020, 21, 294. [CrossRef]

- https://www.Proteinatlas.Org/ENSG00000197405-C5AR1/Single+cell+type/Bone+marrow.

- Woodcock, J.M.; Zacharakis, B.; Plaetinck, G.; Bagley, C.J.; Qiyu, S.; Hercus, T.R.; Tavernier, J.; Lopez, A.F. Three Residues in the Common Beta Chain of the Human GM-CSF, IL-3 and IL-5 Receptors Are Essential for GM-CSF and IL-5 but Not IL-3 High Affinity Binding and Interact with Glu21 of GM-CSF. EMBO J 1994, 13, 5176–5185. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Moczygemba, M.; Huston, D.P. Biology of Common Beta Receptor-Signaling Cytokines: IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003, 112, 653–665; quiz 666. [CrossRef]

| Sample | Total number of paired-end reads, mln | Uniquely Mapped Reads, % | Assigned reads, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 NK-Control | 65 162 324 | 83.7 | 44.2 |

| 2 NK-BCG | 48 924 684 | 72.4 | 39.1 |

| 3 NK-Control | 46 873 566 | 84.6 | 42.5 |

| 4 NK-BCG | 64 495 716 | 58.6 | 28.6 |

| 5 NK-Control | 55 366 344 | 82.9 | 46.5 |

| 6 NK-BCG | 74 519 736 | 85.1 | 43.5 |

| 1 Neutrophils-Control | 62 399 420 | 86.6 | 51.9 |

| 2 Neutrophils -BCG | 40 533 212 | 85.6 | 50.3 |

| 3 Neutrophils-Control | 33 291 886 | 87.5 | 52.4 |

| 4 Neutrophils-BCG | 50 416 772 | 85.2 | 51.8 |

| 5 Neutrophils-Control | 62 632 742 | 85.9 | 49.9 |

| 6 Neutrophils-BCG | 96 455 090 | 74.9 | 45.1 |

| 1 Monocytes-Control | 60 950 058 | 83.2 | 52.5 |

| 2 Monocytes-BCG | 82 245 150 | 80.2 | 50.4 |

| 3 Monocytes-Control | 43 105 930 | 79.2 | 52.2 |

| 4 Monocytes-BCG | 29 940 714 | 82.8 | 51.6 |

| 5 Monocytes-Control | 55 015 316 | 83.6 | 52.7 |

| 6 Monocytes-BCG | 61 669 888 | 83.6 | 49.5 |

| 1 Bone Marrow-Control | 63 168 828 | 40.1 | 21.2 |

| 2 Bone Marrow-BCG | 81 364 514 | 38.8 | 17.8 |

| 3 Bone Marrow-Control | 67 743 872 | 53.5 | 28.5 |

| 4 Bone Marrow-BCG | 65 372 628 | 36.8 | 21.1 |

| 5 Bone Marrow-Control | 66 961 914 | 35.9 | 24.8 |

| 6 Bone Marrow-BCG | 39 376 158 | 42.0 | 18.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).