Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

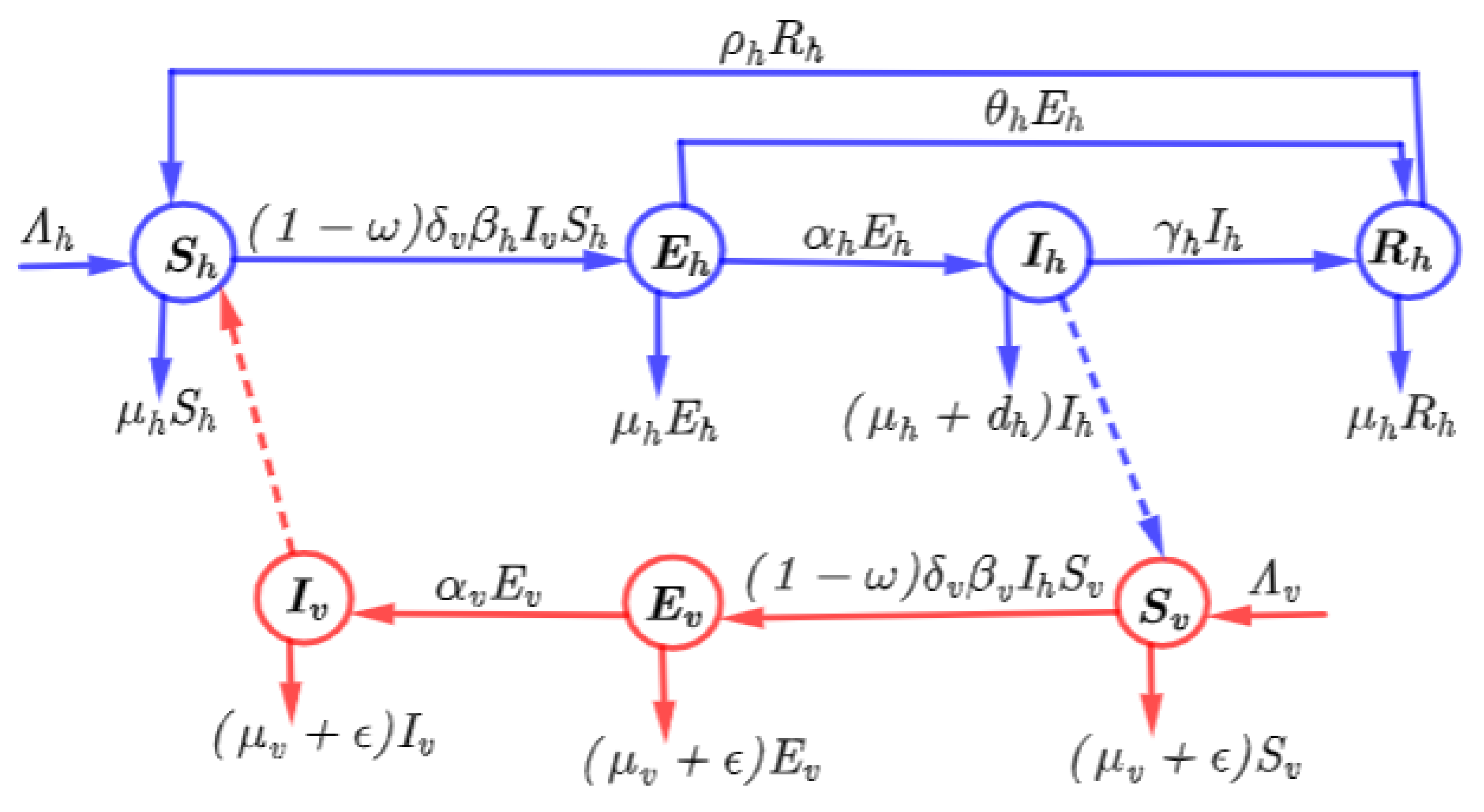

2. Model Formulation

3. Basic Properties

3.1. Positivity Of Solutions

3.2. Boundedness Of Trajectories

4. Basic Reproduction Number and Existence of Equilibria

4.1. Local Stability of the Disease Free Equilibrium Point

4.2. Endemic Equilibrium Point

5. Results and Discussion

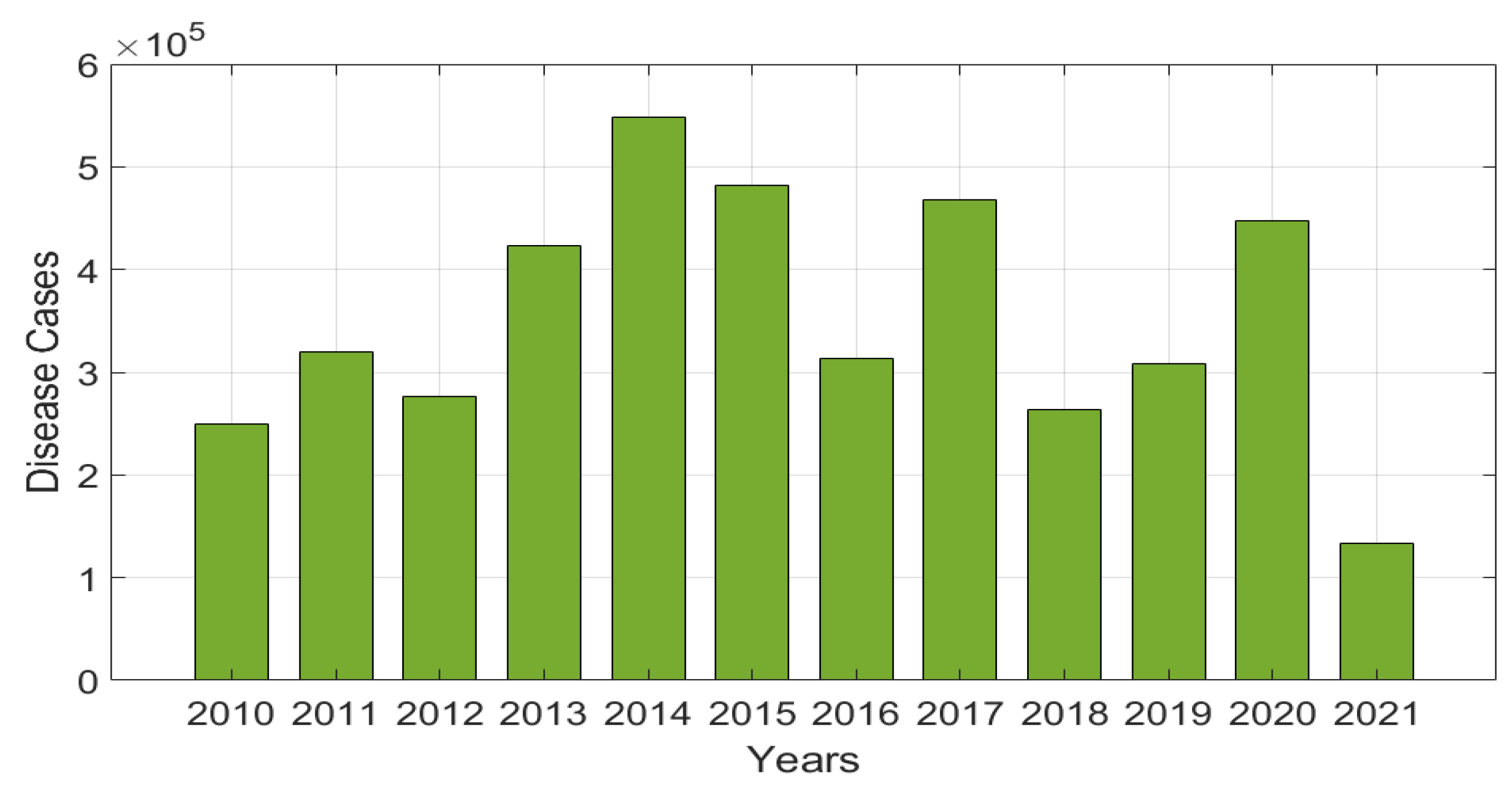

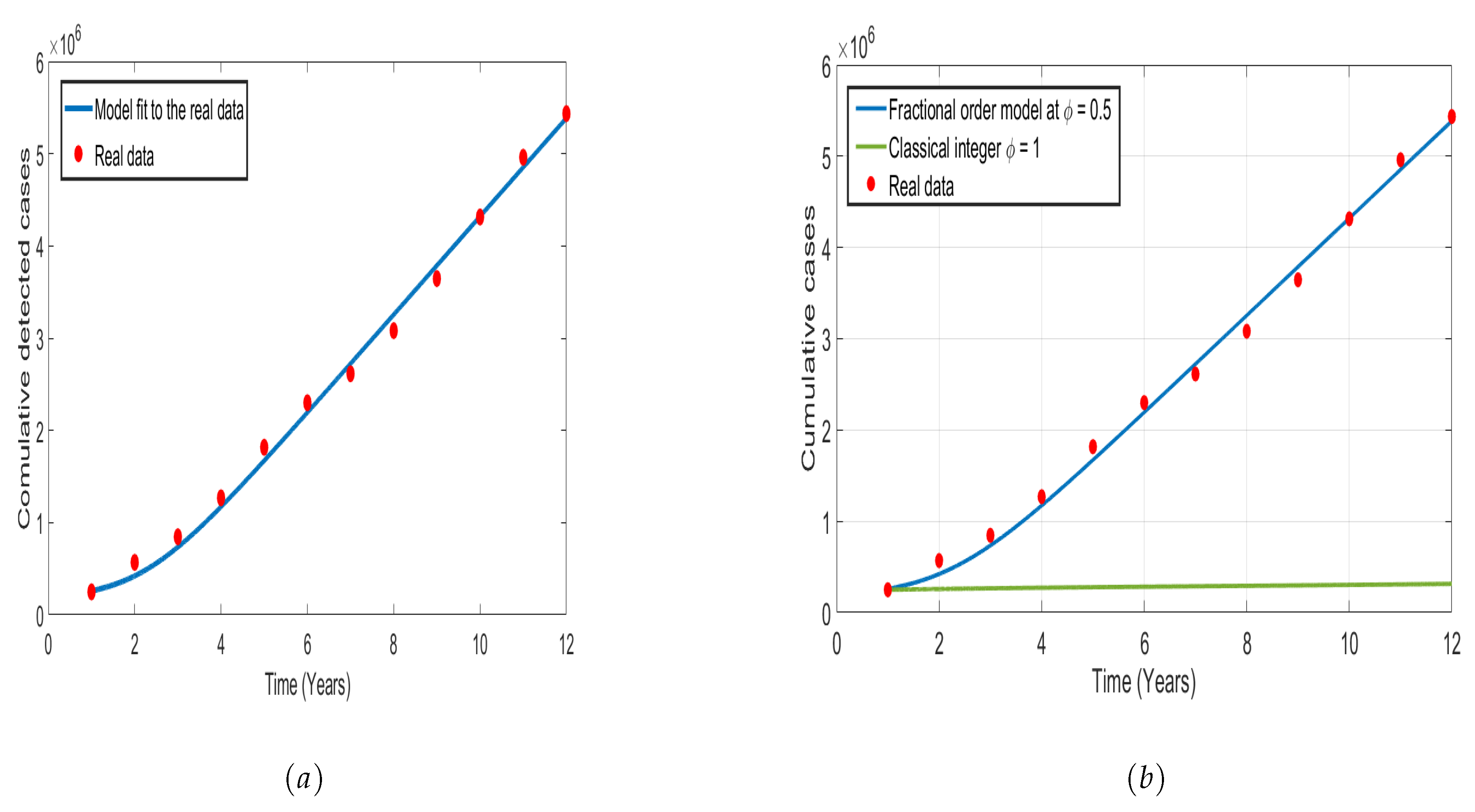

5.1. Model Parameter Estimations

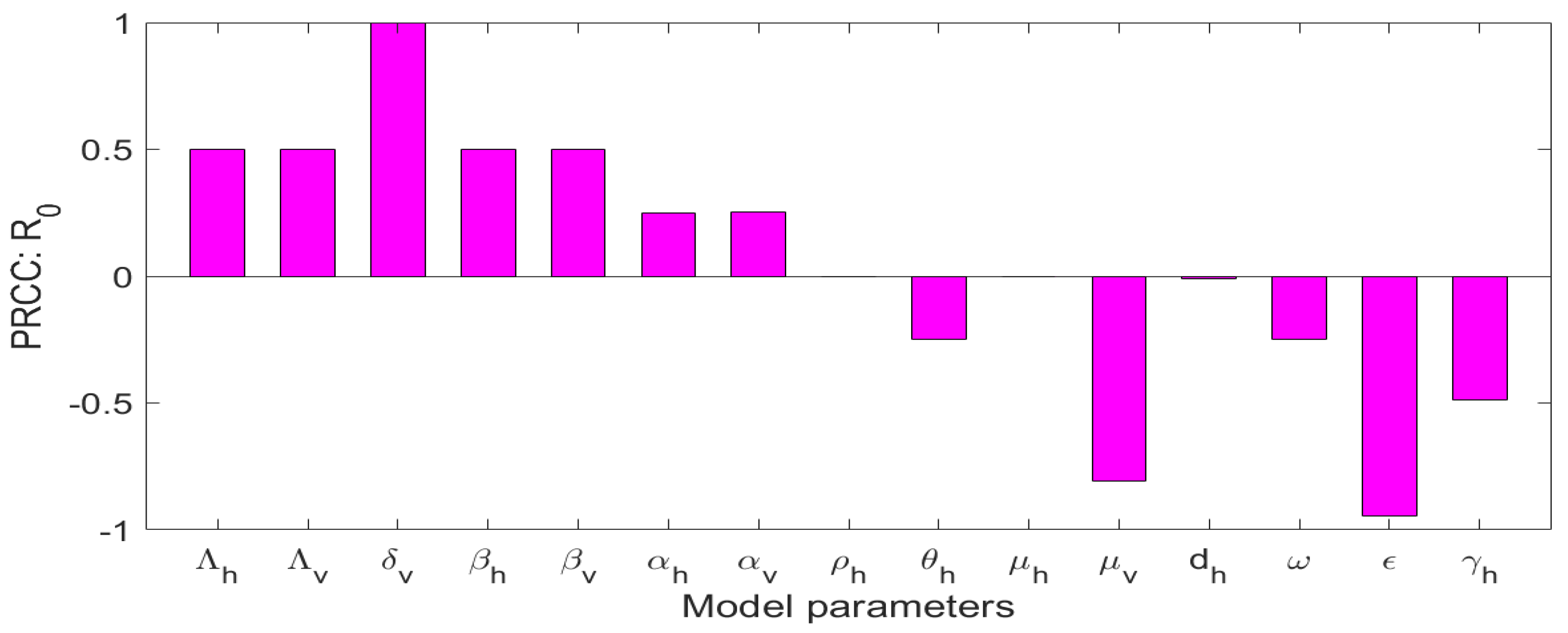

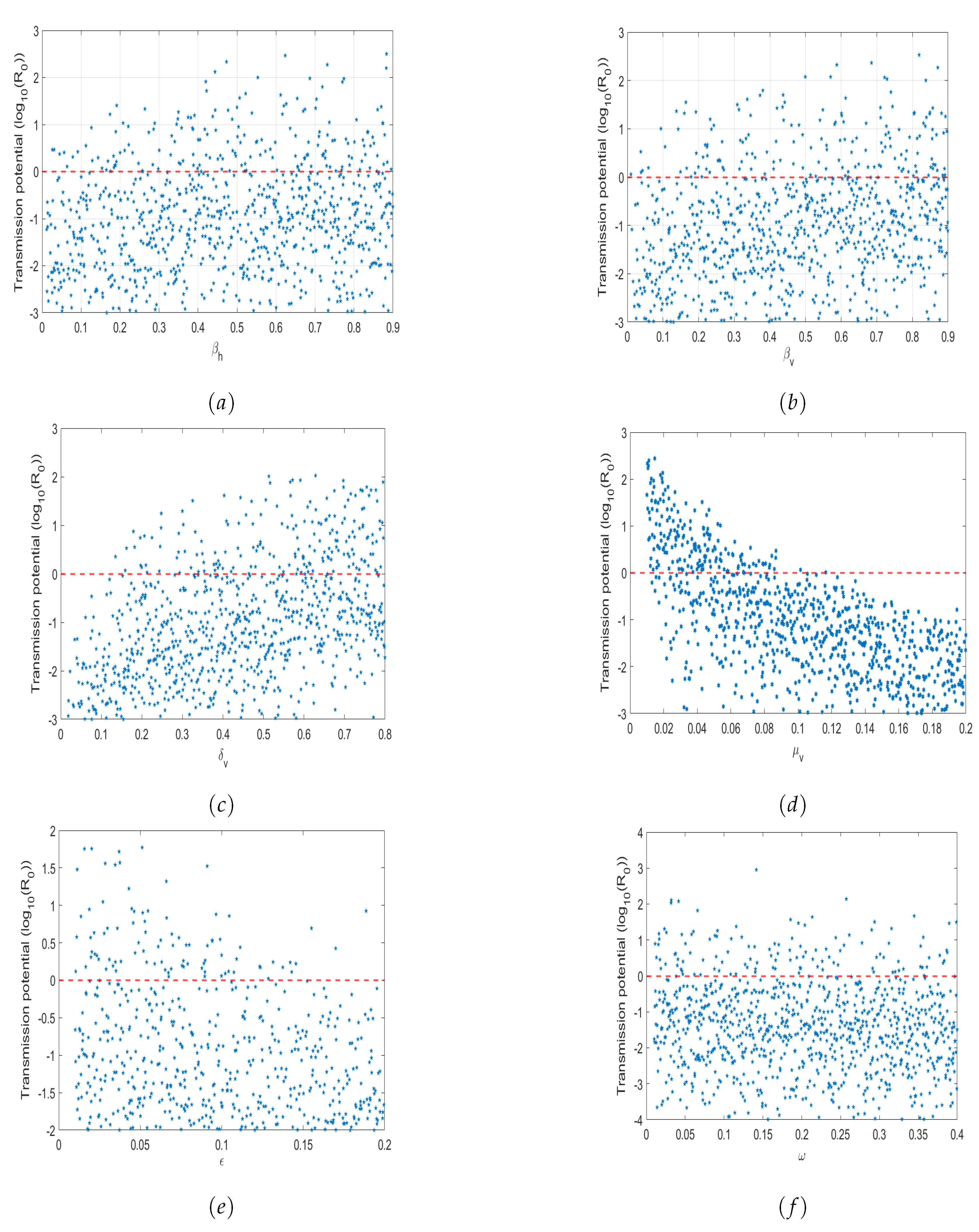

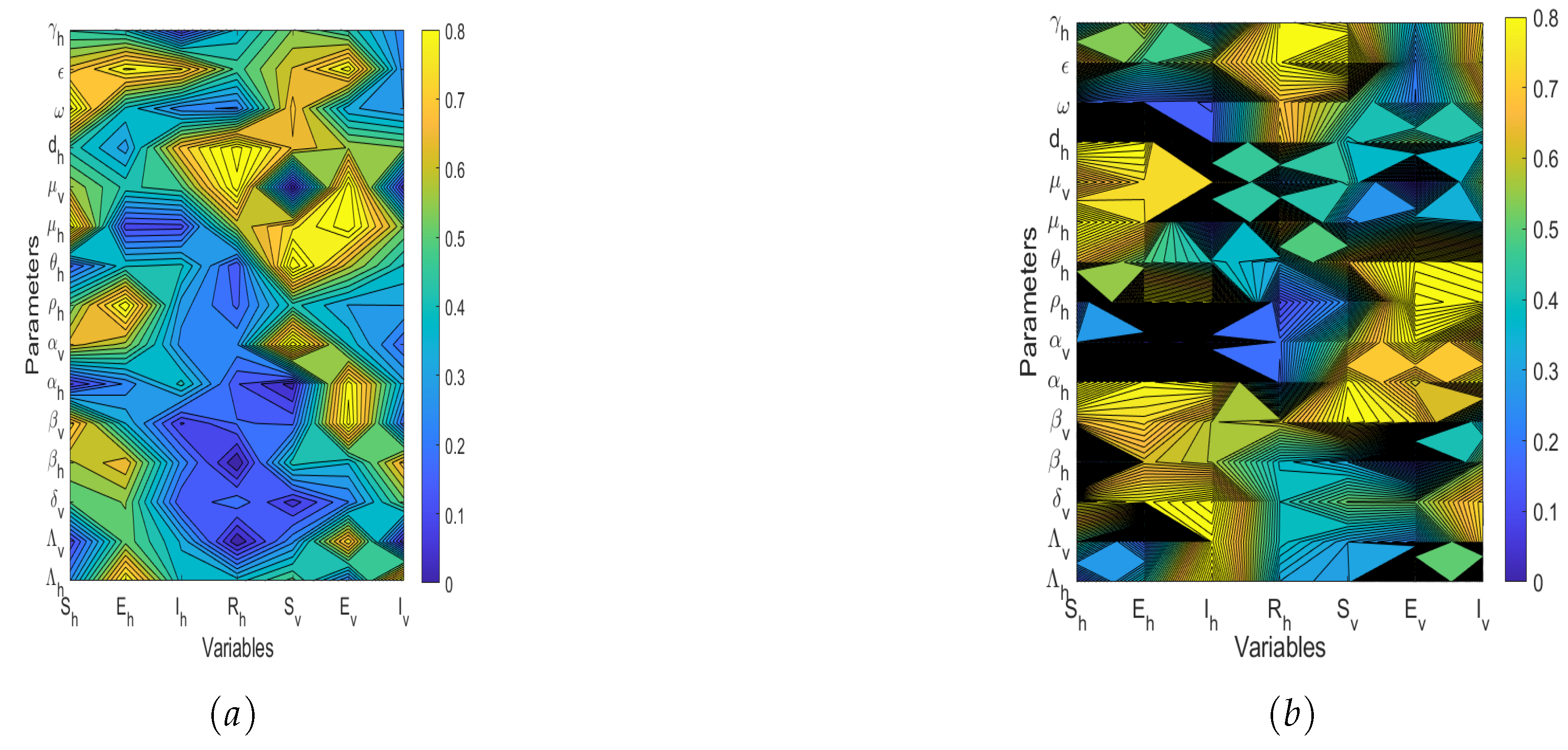

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis

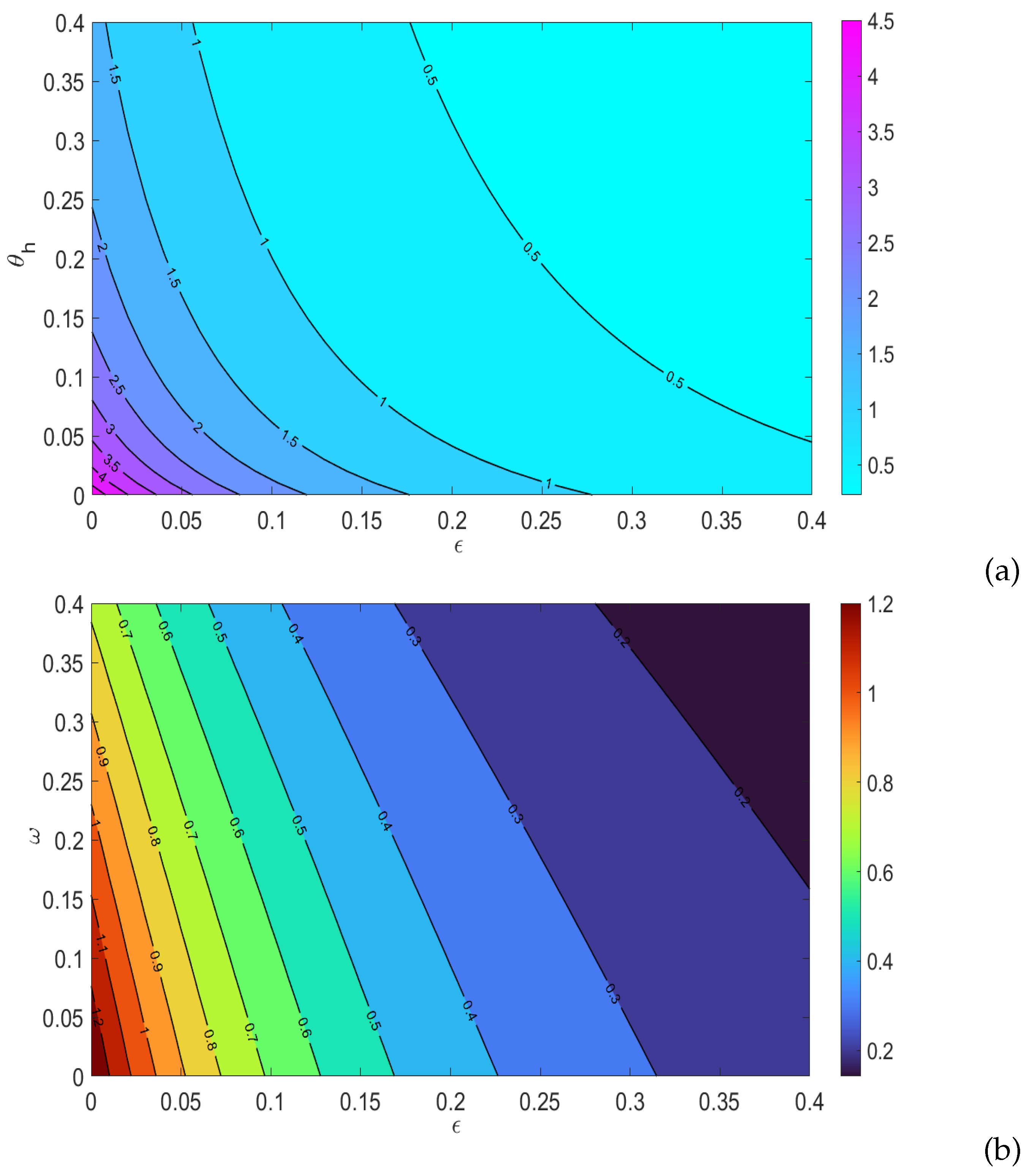

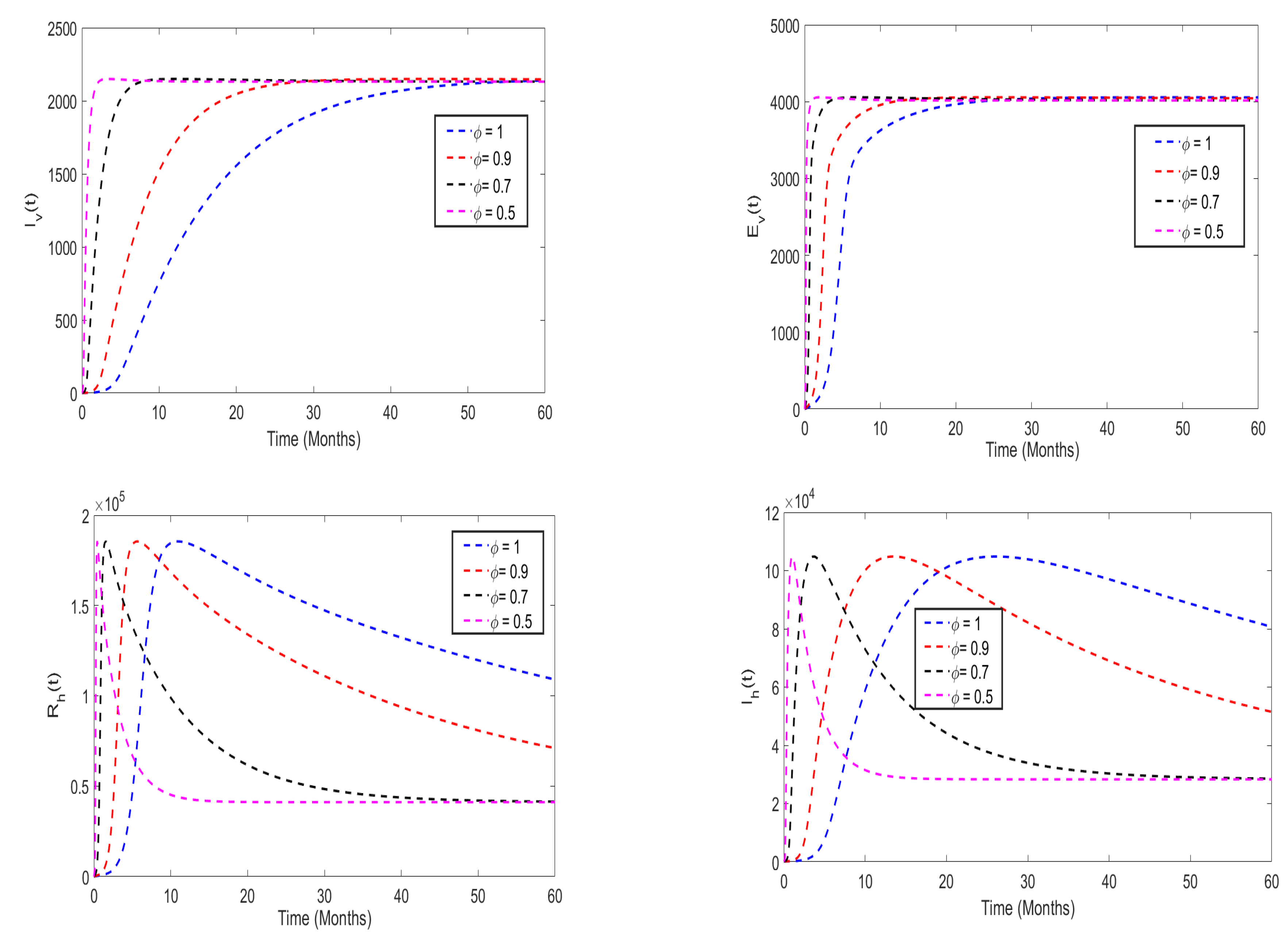

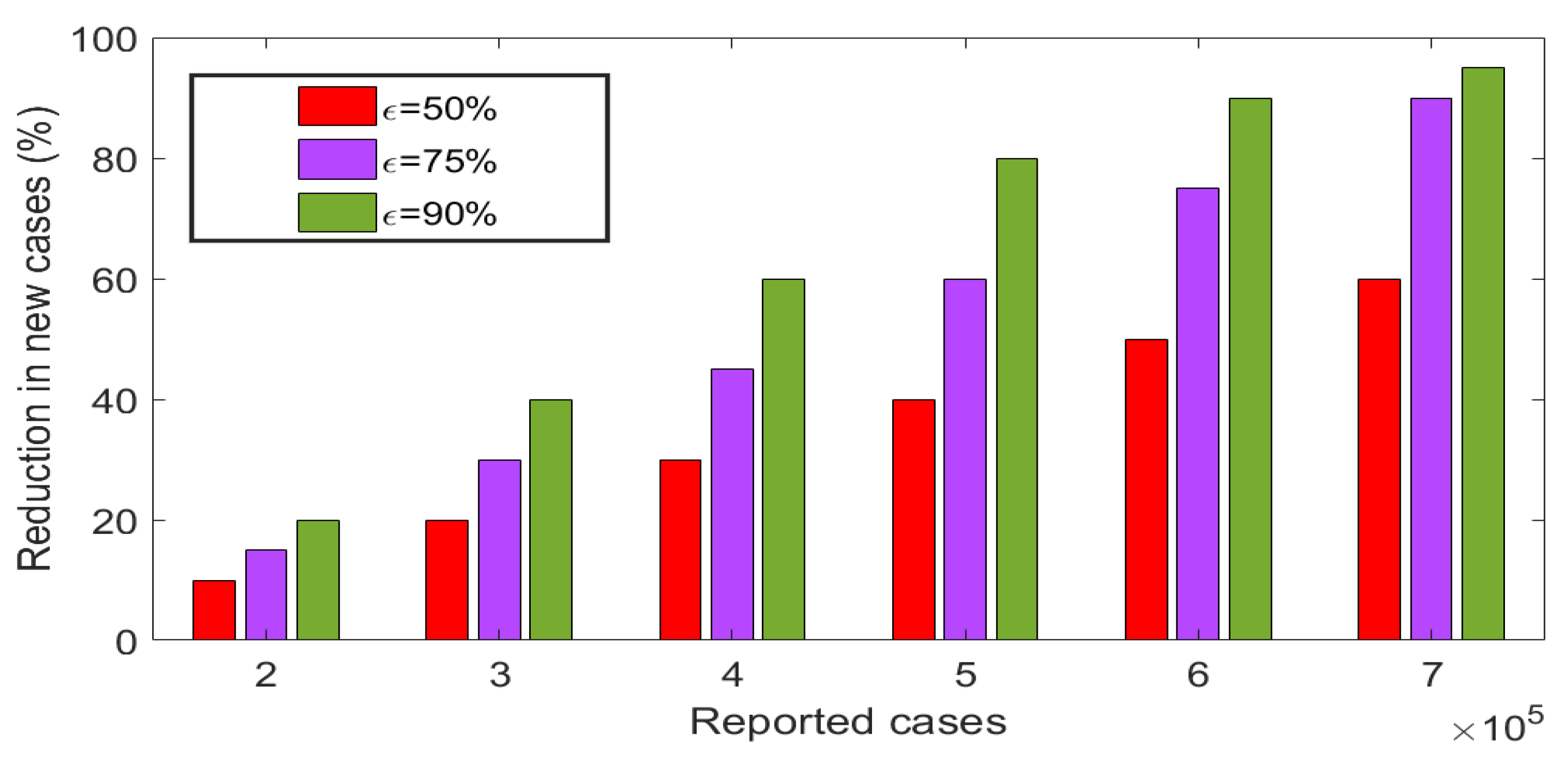

5.3. Effects of insecticides use on the disease dynamics

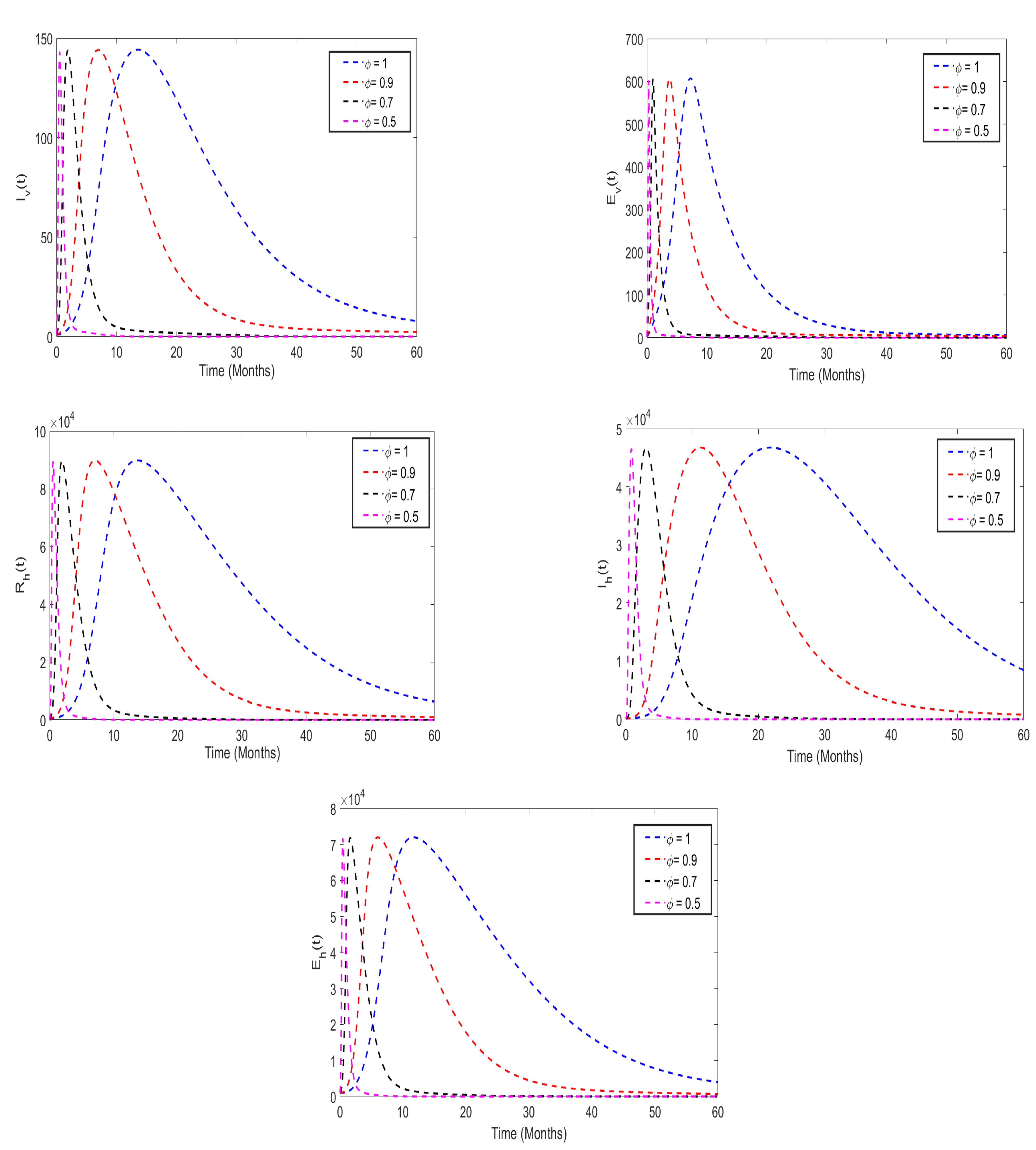

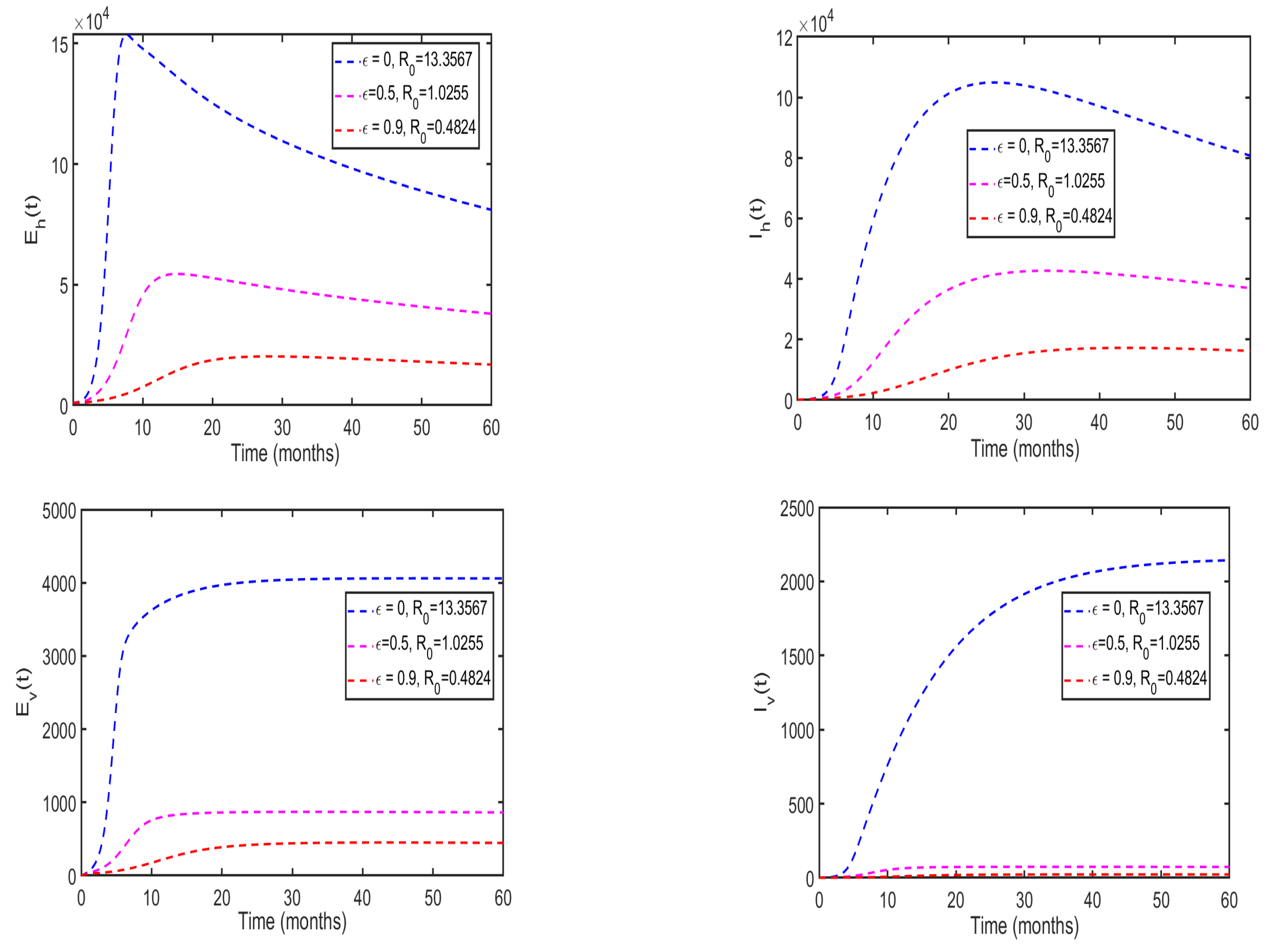

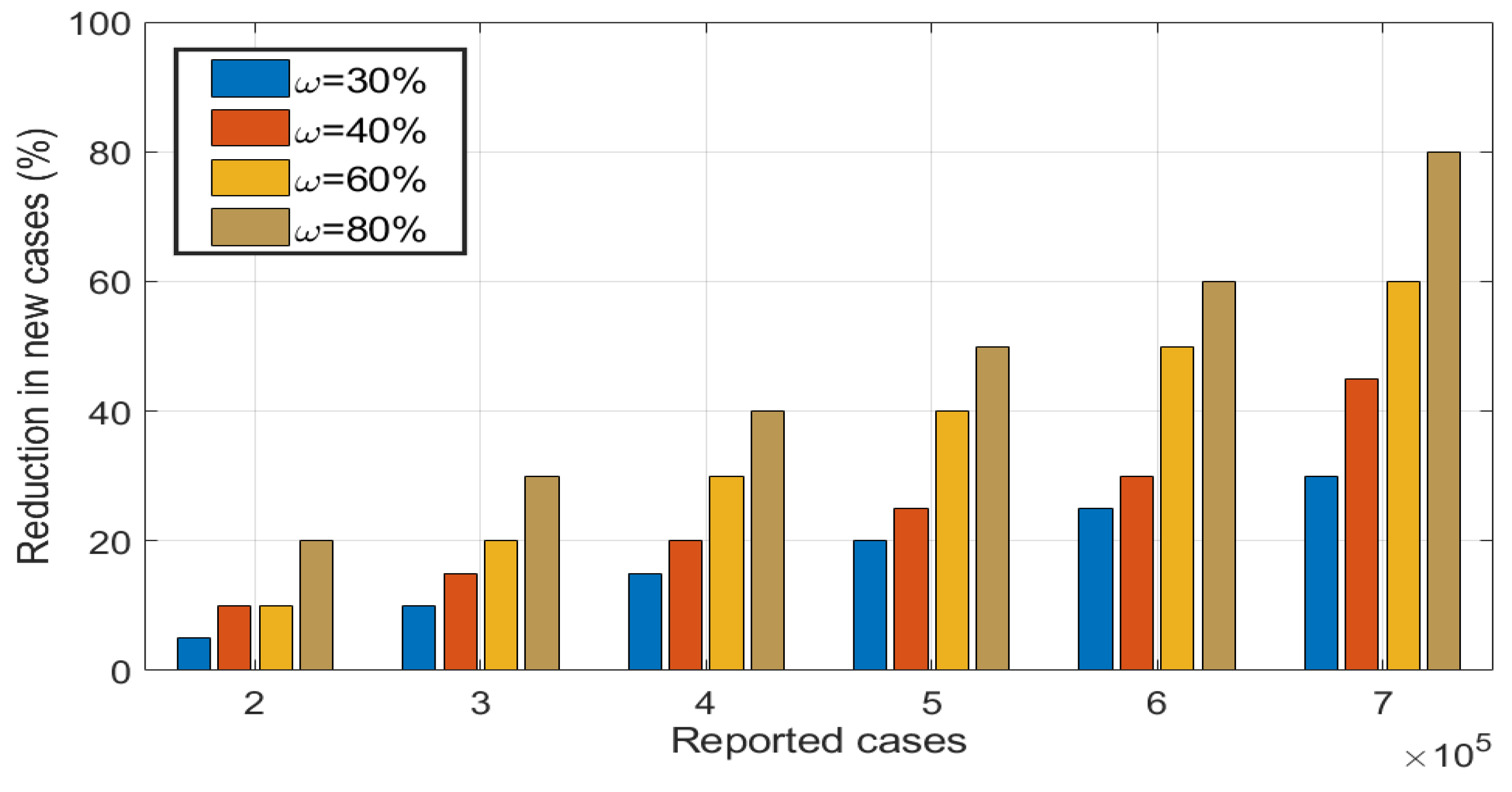

5.4. Effects of health education campaigns on the disease dynamics

6. Concluding Remarks

References

- Singh, Ram and ul Rehman, Attiq, (2022). A fractional-order malaria model with temporary immunity, Mathematical Analysis of Infectious Diseases, 81-101.

- Pawar, DD and Patil, WD and Raut, DK, (2021). Analysis of malaria dynamics using its fractional order mathematical model, Journal of applied mathematics & informatics, 2(39), 197-214.

- Gizaw, Ademe Kebede and Deressa, Chernet Tuge, (2024). Analysis of Age-Structured Mathematical Model of Malaria Transmission Dynamics via Classical and ABC Fractional Operators, Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 1(3855146). [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, Priya, (2024). The 2023 WHO World malaria report,The Lancet Microbe, 3(5), e214. [CrossRef]

- Cerilo-Filho, Marcelo and Arouca, Marcelo de L and Medeiros, Estela dos S and Jesus, Myrela and Sampaio, Marrara P and Reis, Nathália F and Silva, José RS and Baptista, Andréa RS and Storti-Melo, Luciane M and Machado, Ricardo LD and others, (2024). Worldwide distribution, symptoms and diagnosis of the coinfections between malaria and arboviral diseases: A systematic review, Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 119, e240015. [CrossRef]

- Klepac, Petra and Hsieh, Jennifer L and Ducker, Camilla L and Assoum, Mohamad and Booth, Mark and Byrne, Isabel and Dodson, Sarity and Martin, Diana L and Turner, C Michael R and van Daalen, Kim R, (2024). Climate change, malaria and neglected tropical diseases: A scoping review, Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, trae02.

- Sugathan, Adarsh and Rao, Shamathmika and Kumar, Nayanatara Arun and Chatterjee, Pratik, (2024). Malaria and Malignancies-A review, Global Biosecurity, 6. [CrossRef]

- Patel, Priya and Bagada, Arti and Vadia, Nasir, (2024). Epidemiology and Current Trends in Malaria, Rising Contagious Diseases: Basics, Management, and Treatments, 261-282.

- van den Driessche P. and Watmough, J, (2002). Reproduction number and subthreshold endemic equilibria for compartment models of disease transmission, Math. Biosci, Vol. 180, Pg. 29-48.

- Ibrahim, Malik Muhammad and Kamran, Muhammad Ahmad and Naeem Mannan, Malik Muhammad and Kim, Sangil and Jung, Il Hyo, (2020). Impact of awareness to control malaria disease: A mathematical modeling approach, Complexity, 1(8657410). [CrossRef]

- Marino, S., Hogue, I.B., Ray, C.J. & Kirschner, D.E. (2008). A methodology for performing global uncertainty and sensitivity analysis in systems biology. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 254(1), 178–196. [CrossRef]

- Z. Shuai, J.A.P. Heesterbeek, and P. van den Driessche, Extending the type reproduction number to infectious disease control targeting contact between types, J. Math. Biol, 67 (2013), 1067-1082. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R and Kumar, K and Dohare, R,2023. Caputo fractional order derivative model of Zika virus transmission dynamics, J. Math. Comput. Sci, Vol. 28, pg. 145-157.

- LaSalle J.P., The Stability of Dynamical Systems, SIAM, Philadelphia, (1976).

- Kouidere, Abdelfatah and El Bhih, Amine and Minifi, Issam and Balatif, Omar and Adnaoui, Khalid, (2024). Optimal control problem for mathematical modeling of Zika virus transmission using fractional order derivatives, Frontiers in Applied Mathematics and Statistics, Vol. 10, Pg. 1376507. [CrossRef]

- White, Lisa J and Maude, Richard J and Pongtavornpinyo, Wirichada and Saralamba, Sompob and Aguas, Ricardo and Van Effelterre, Thierry and Day, Nicholas PJ and White, Nicholas J, (2009). The role of simple mathematical models in malaria elimination strategy design, Malaria journal, 8, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Rakkiyappan, R and Latha, V Preethi and Rihan, Fathalla A, (2019). A Fractional-Order Model for Zika Virus Infection with Multiple Delays, Wiley Online Library, Vol. 1, Pg. 4178073. [CrossRef]

- Lashari, Abid Ali and Aly, Shaban and Hattaf, Khalid and Zaman, Gul and Jung, Il Hyo and Li, Xue-Zhi, (2012). Presentation of malaria epidemics using multiple optimal controls, Journal of Applied mathematics, 1(946504). [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Mohammad Sharif and Higazy, M and Kabir, KM Ariful, (2022).Modeling the epidemic control measures in overcoming COVID-19 outbreaks: A fractional-order derivative approach, Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, Vol. 155, Pg 111636. [CrossRef]

- Rakkiyappan, R and Latha, V Preethi and Rihan, Fathalla A, (2019). A Fractional-Order Model for Zika Virus Infection with Multiple Delays, Complexity, Vol. 1, Pg. 4178073. [CrossRef]

- Lusekelo, Eva and Helikumi, Mlyashimbi and Kuznetsov, Dmitry and Mushayabasa, Steady, (2023). Dynamic modelling and optimal control analysis of a fractional order chikungunya disease model with temperature effects, Results in Control and Optimization, Vol. 10, Pg.100206. [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, Behzad and Atangana, Abdon, (2020). A new application of fractional Atangana–Baleanu derivatives: Designing ABC-fractional masks in image processing, Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 542, 123516. [CrossRef]

- Helikumi, Mlyashimbi and Lolika, Paride O, (2022). Global dynamics of fractional-order model for malaria disease transmission, Asian Research Journal of Mathematics, 18 (9), 82-110. [CrossRef]

- Helikumi, Mlyashimbi and Eustace, Gideon and Mushayabasa, Steady (2022). Dynamics of a Fractional-Order Chikungunya Model with Asymptomatic Infectious Class, Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, Vol.1, pg. 5118382. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Naveen and Singh, Ram and Singh, Jagdev and Castillo, Oscar, (2021). Modeling assumptions, optimal control strategies and mitigation through vaccination to zika virus, Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, Vol.150, Pg. 111137. [CrossRef]

- Iheonu, NO and Nwajeri, UK and Omame, A (2023). A non-integer order model for Zika and Dengue co-dynamics with cross-enhancement, Healthcare Analytics, Vol.4, pg.100276. [CrossRef]

- Momoh, Abdulfatai A and Fügenschuh, Armin (2018). Optimal control of intervention strategies and cost effectiveness analysis for a Zika virus model, Operations Research for Health Care, Vol. 18, Pg. 99-111. [CrossRef]

- Nisar, Kottakkaran Sooppy and Farman, Muhammad and Abdel-Aty, Mahmoud and Ravichandran, Chokalingam, (2024). A review of fractional order epidemic models for life sciences problems: Past, present and future, Alexandria Engineering Journal, Vol. 95, Pg. 283-305. [CrossRef]

- Kimulu, Ancent Makau, (2023). Numerical Investigation of HIV/AIDS Dynamics Among the Truckers and the Local Community at Malaba and Busia Border Stops, American Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, 13(1), 6-16.

- Tesla, Blanka and Demakovsky, Leah R and Mordecai, Erin A and Ryan, Sadie J and Bonds, Matthew H and Ngonghala, Calistus N and Brindley, Melinda A and Murdock, Courtney C, (2018). Temperature drives Zika virus transmission: Evidence from empirical and mathematical models, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Vol. 285, Pg. 20180795. [CrossRef]

- Maity, Sunil and Sarathi Mandal, Partha, (2024). The effect of demographic stochasticity on Zika virus transmission dynamics: Probability of disease extinction, sensitivity analysis, and mean first passage time,Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, Vol. 34, Pg. 3.

- Song, Byung-Hak and Yun, Sang-Im and Woolley, Michael and Lee, Young-Min, (2017). Zika virus: History, epidemiology, transmission, and clinical presentation,Journal of neuroimmunology, Vol. 308, Pg. 50-64.

- Atokolo, William and Mbah Christopher Ezike, Godwin, (2020). Modeling the control of zika virus vector population using the sterile insect technology, Journal of Applied Mathematics,Vol.2020, 1(6350134).

- Saad-Roy, CM and Van den Driessche, P and Ma, Junling, (2016). Estimation of Zika virus prevalence by appearance of microcephaly, BMC Infectious Diseases, Vol. 16, Pg. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Kimulu, Ancent M and Mutuku, Winifred N and Mwalili, Samuel M and Malonza, David and Oke, Abayomi Samuel, (2022). Male circumcision: A means to reduce HIV transmission between truckers and female sex workers in Kenya, Male circumcision: A means to reduce HIV transmission between truckers and female sex workers in Kenya, 3(1), 50-59. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, Carla MA and Machado, JA Tenreiro, (2013). Fractional model for malaria transmission under control strategies, Computers & Mathematics with Applications, 5(65), 908-916. [CrossRef]

- Abioye, Adesoye Idowu and Peter, Olumuyiwa James and Ogunseye, Hammed Abiodun and Oguntolu, Festus Abiodun and Ayoola, Tawakalt Abosede and Oladapo, Asimiyu Olalekan (2023). A fractional-order mathematical model for malaria and COVID-19 co-infection dynamics, Healthcare Analytics, 4(100210). [CrossRef]

- Helikumi, Mlyashimbi and Lolika, Paride O, (2022). A note on fractional-order model for cholera disease transmission with control strategies, Commun. Math. Biol. Neurosci, Article-ID. [CrossRef]

- Saadeh, Rania and Abdoon, Mohamed A and Qazza, Ahmad and Berir, Mohammed and Guma, Fathelrhman EL and Al-Kuleab, Naseam and Degoot, Abdoelnaser M, (2024). Mathematical modeling and stability analysis of the novel fractional model in the Caputo derivative operator: A case study, Heliyon, 5(10),. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Pushpendra and Baleanu, Dumitru and Erturk, Vedat Suat and Inc, Mustafa and Govindaraj, V, (2022). A delayed plant disease model with Caputo fractional derivatives, title=A delayed plant disease model with Caputo fractional derivatives, Advances in Continuous and Discrete Models, 1(11).

- ul Rehman, Attiq and Singh, Ram and Abdeljawad, Thabet and Okyere, Eric and Guran, Liliana, (2021). Modeling, analysis and numerical solution to malaria fractional model with temporary immunity and relapse, Advances in Difference Equations, 1(390). [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Definition | Value | Units | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| disease transmission from mosquito to human | 0.001 | [16,18] | ||

| disease transmission from human to mosquito | 0.0001 | [16,18] | ||

| natural mortality rate of human | [16,18] | |||

| natural mortality rate of vector | [16,18] | |||

| progression rate of human from incubation to infectious | 1/17 | [10,18] | ||

| progression rate of vector from incubation to infectious | 1/18 | [10,18] | ||

| progression rate of human from infectious to recovered class | [10] | |||

| new recruitment of human | 10 | [16,18] | ||

| new recruitment of Aedes mosquito | 50 | [10] | ||

| progression rate of exposed human to recovered class | fitted | |||

| Rate of use of insecticides | fitted | |||

| Proportion of human progress to infectious class | fitted | |||

| Rate of mosquito biting on human | 3 | [10] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).