Materials and Methods

This study was overseen by the CBSET Inc., Contract Research Organization’s (Lexington, MA) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and conformed to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals”. CBSET, Inc. is accredited by AAALAC International and is registered with the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

A procedure was performed in 10 Yorkshire swine (40-50kg; Sus scrofa domesticus), where CO2 was sprayed into the gastric lumen by an ancillary administration device, with no hemostatic powder applied.

Animals were fed a liquid diet daily beginning three days before anesthetic induction. The liquid diet consisted of pig chow (#5084 Laboratory Porcine Diet Grower), full-fat yogurt, a high-calorie supplemental drink, whey protein, and amino acid powder. All animals received their last feeding ~20-24 hours before the procedure.

A tiletamine-zolazepam (4-6 mg/kg) intramuscular injection was administered as a pre-anesthetic. An endotracheal tube was placed for ventilatory support and general inhalant anesthesia delivery. Animals were maintained under isoflurane inhalant anesthesia. An intravenous catheter was placed in a marginal ear vein for IV fluid and drug administration.

Vital signs including electrocardiogram (ECG), pulse-oximetry, temperature, respiratory rate, and blood pressure were monitored continuously at regular intervals during the procedure.

A vascular introducer sheath was placed percutaneously into the right femoral artery for invasive blood pressure monitoring and blood sampling.

Heparin was administered intravenously (initial bolus: 50-150 IU/kg; maintenance CRI: 75-200 IU/kg/h) to maintain an ACT between 170 seconds and 300 seconds (ACT measured using Hemochron Elite; ACT+ cartridge).

Mean arterial pressure was maintained between 75 and 85mmHg. Phenylephrine was administered intravenously (CRI: 0.25-20 mcg/kg/min) as needed to modulate the blood pressure.

The abdominal organs were exposed through a midline laparotomy and a ~3mm full-thickness defect was created in the gastric antrum. A foley catheter was inserted through the defect and secured within the gastric lumen by inflating the balloon oriented towards the catheter tip. The defect site was closed and cinched around the Foley catheter using a purse-string suturing pattern. The Foley catheter was attached to a pressure transducer and connected to a single analog channel on a PowerLab Instrument Interface unit to record intragastric pressure readings (

Figure S1A).

Perivascular adipose tissue was carefully dissected away from the external surface of a 1-3 cm segment of the splenic arteriovenous bundle. The exposed vascular segment was positioned within the gastric lumen through an ~1cm gastrotomy. The vascular segment was secured within the stomach by suturing (3-0 Prolene) the gastrotomy margins closed using a continuous suturing pattern. Upon confirmation, an overstitch layer was sutured (3-0 Prolene) in place at the gastrotomy site using a Cushing suture pattern (

Figure S1B).

Perivascular flow probes were positioned both proximal and distal to the gastrotomy site and fixed to the external surface of the gastric wall. Each flow probe was connected to an analog channel on the PowerLab. The midline laparotomy was closed using standard surgical techniques (

Figure S1C).

An Olympus GIF-2TH180 gastroscope was advanced into the stomach. Animals with flow probe implants underwent a series of insufflation and desufflation cycles (flow rate: 1.5 SLPM) before induction of a bleed (pre-puncture;

Figure S2A). Observations of blood flow cessation or degradation were documented. Pressure and flow data were digitally recorded.

A 5.5Fr Rx Needle knife was advanced down the gastroscope’s working channel. The electrosurgical tip was positioned close to the internal segment of the splenic artery. Using an en-face approach, the electrosurgical tip was activated and poked through the arterial wall.

The resulting bleed was scored as a Rating 4 (extreme spurting flow), Rating 3 (spurting flow), Rating 2 (moderate oozing flow), Rating 1 (slow oozing leakage), or Rating 0 (no active blood flow) bleed by the sponsor surgeon (

Figure S4). If the initial injury did not produce a severe bleed, additional punctures were created until a Rating 3 or Rating 4 was scored. Hemostasis (Rating 0) in this model is defined as the absence of visible blood flowing out from the punctured vessel. [

5]

After a Forrest 1a bleed is induced, the procedural steps that follow (post-puncture) depend on the resulting bleed score (

Figure S2B). In addition to obtaining bleed ratings, pressure, and flow data were recorded when possible. Most studies reference the mass of powder applied to a bleed to indicate hemostatic agent efficacy [

6,

9]. To establish an applicable sham control in which gas is used to deliver hemostatic powder to the bleed site, without administering hemostatic powder, a spray time value was used in preference to a spray mass value. An applicable spray time algorithm was generated by averaging the spray time data collected through pilot studies using commercially available hemostatic powders in this model. An average spray (8 seconds), followed by two successive standard deviations (6 seconds, 6 seconds), was determined to be a representative (preclinical) spray algorithm.

In general, the spray algorithm proceeded as follows (

Figure S2B); compressed CO

2 canister (flow rate: 6 SLPM) was sprayed at an active bleed utilizing the prototype hemostatic powder spray device, and if not rated a ‘0’ (i.e., if the bleed has not stopped), additional CO

2 sprays were applied. Following the set sequence of sprays, the stomach was desufflated, and this spray algorithm was repeated. If the bleed stopped, and a bleed score of ‘0’ was achieved, the stomach was desufflated and the bleed was monitored for 10 minutes to confirm acute hemostasis. Hemostasis was defined as “achieved” in this study, when, within 40 minutes of post-puncture insufflation cycles, the bleed ceased for 10 minutes following desufflation. If the total study time persisted past 40 minutes beyond the initial puncture time without achieving hemostasis, the study was terminated. To further challenge this model, a lower spray time algorithm used to maintain low intragastric pressures was 4-2-2 seconds (

Figure S3).

Results

7/10 animals were included in this vessel bleed model pressure study; 4/7 animals underwent high-pressure cycles, and 3/7 animals underwent low-pressure pressure cycles following bleed initiation. Of the 3 excluded animals, 1/3 animals were discounted due to the inability to achieve an F1a bleed and failure to visualize the bleed condition. Two animals were excluded from the overall data set due to the inadvertent severing of the vessel with the electrosurgical tip, which yielded severe and inoperable hemorrhages unrepresentative of clinical bleed cases.

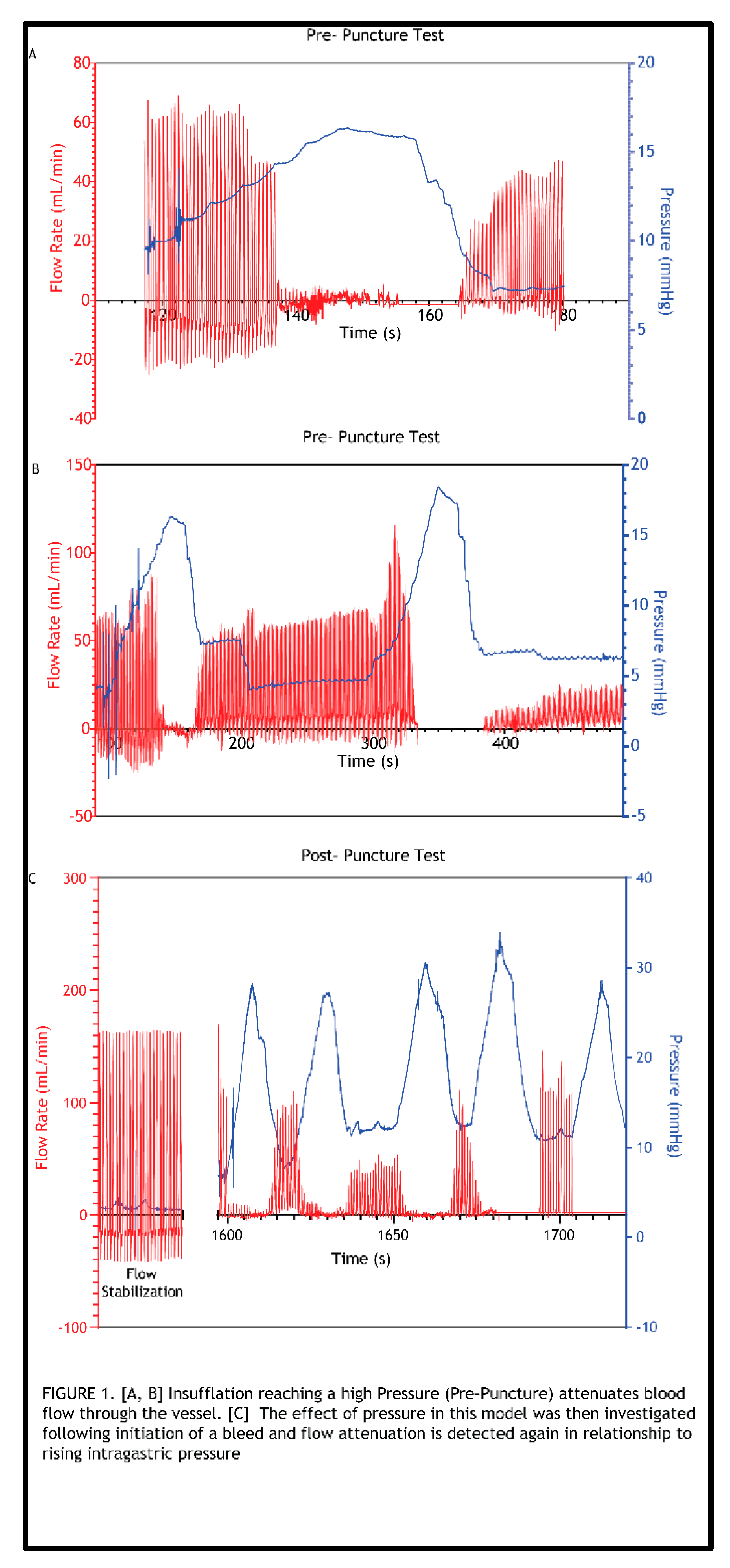

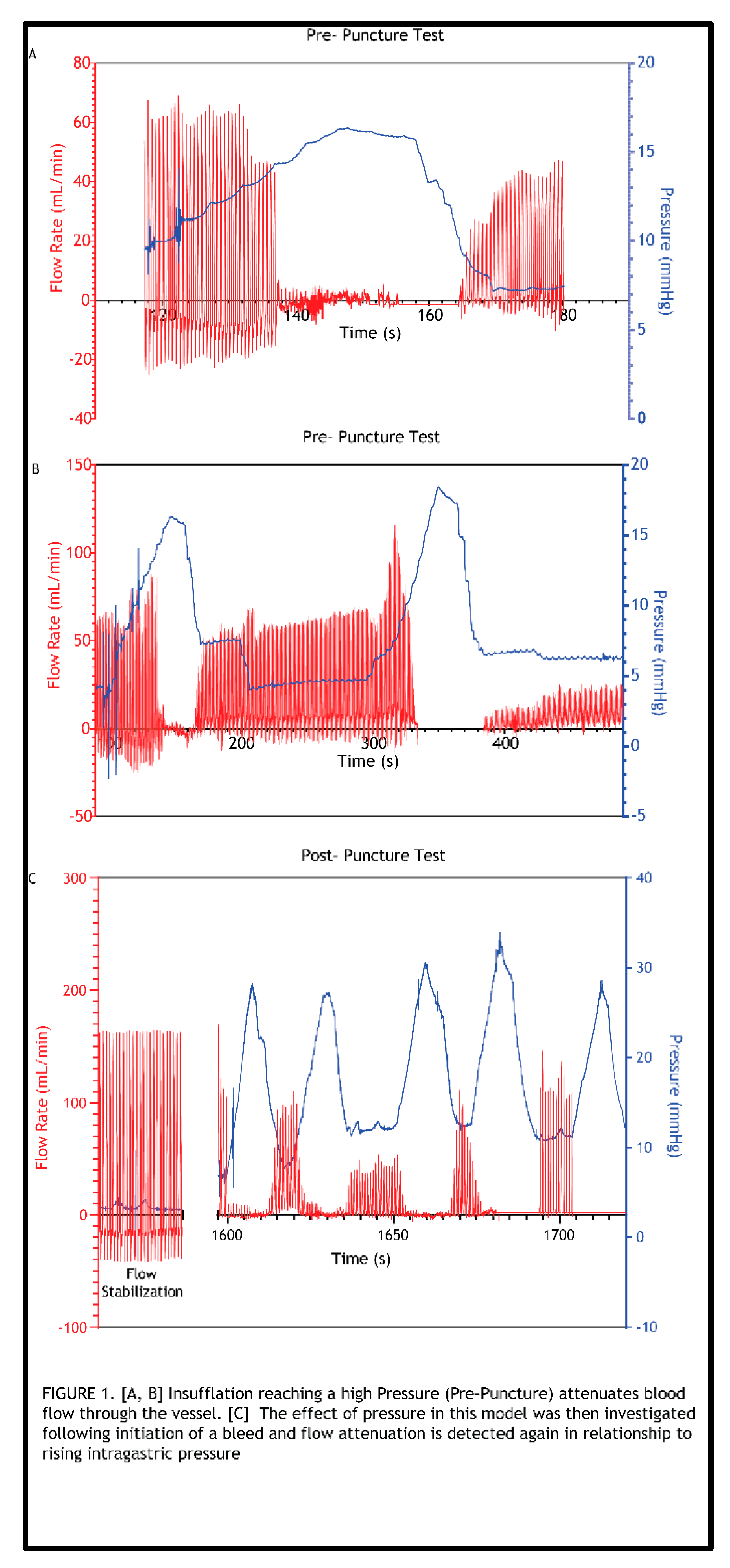

To evaluate the relationship between gastric pressure and vascular flow, and to determine if gastric pressures typically achieved in endoscopic procedures can reduce or stop blood flow through the implanted artery in this model, a series of insufflation and desufflation cycles was first performed before induction of a bleed (

Figure S2A). This was conducted with a pressure sensor sutured within the stomach wall and flow probes attached to the vessel sutured into the stomach (

Figure S1). Delivering these cycles of air into the stomach showed that with increased intragastric pressure there is attenuated vessel blood flow (Figure 1A and 1B). Furthermore, flow magnitude degradation was observed when the flow was restored in the artery post-insufflation cycle. Before proceeding with the puncture (bleed) trial (Figure 1C), a wait time was allotted until the flow was fully restored and stabilized, as measured by the flow probes. A defect was formed by advancing a needle knife through the working channel of the gastroscope. Once confirmed that the resulting bleed was classified as Forrest 1a, pressure cycling was initiated using the pressure cycling pattern outlined in

Figure S2B. Notably, the initial 8-second spray consistently resulted in an immediate bleed interruption (bleed score “0”). Thus, the procedure that resulted consisted of cycles of the 8-second spray followed by desufflation, resulting in the observed 8-second periodicity. In addition, recurring spikes in pressure, which are attributed to CO

2 gas introduced via the spray device, repeatedly reached peak pressures above baseline (insufflation pressure). Attenuation of flow with increased pressure was also observed in this post-puncture (bleed) case. In addition, the amplitude of flow restoration never reached that of the initial flow rate when cycles of pressurization and de-pressurization ensued (Figure 1C). This relationship between pressure and flow was consistently observed across all these initial tests in which representative spray algorithms were applied. Blood flow through the vessel completely ceased until desufflation. 4/4 animals in the study reached hemostasis within the time constraints placed on the bleed study conducted at these higher pressures.

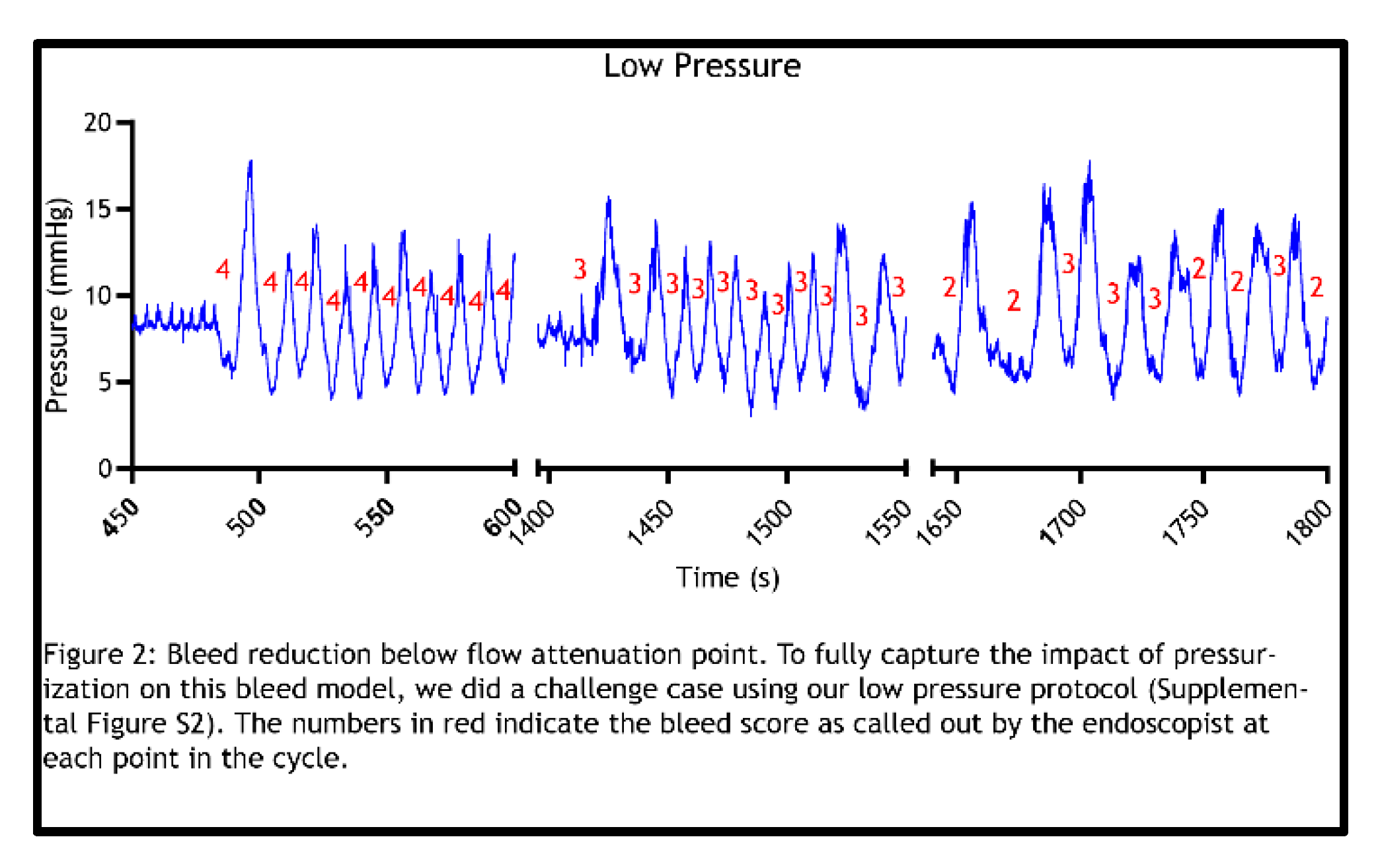

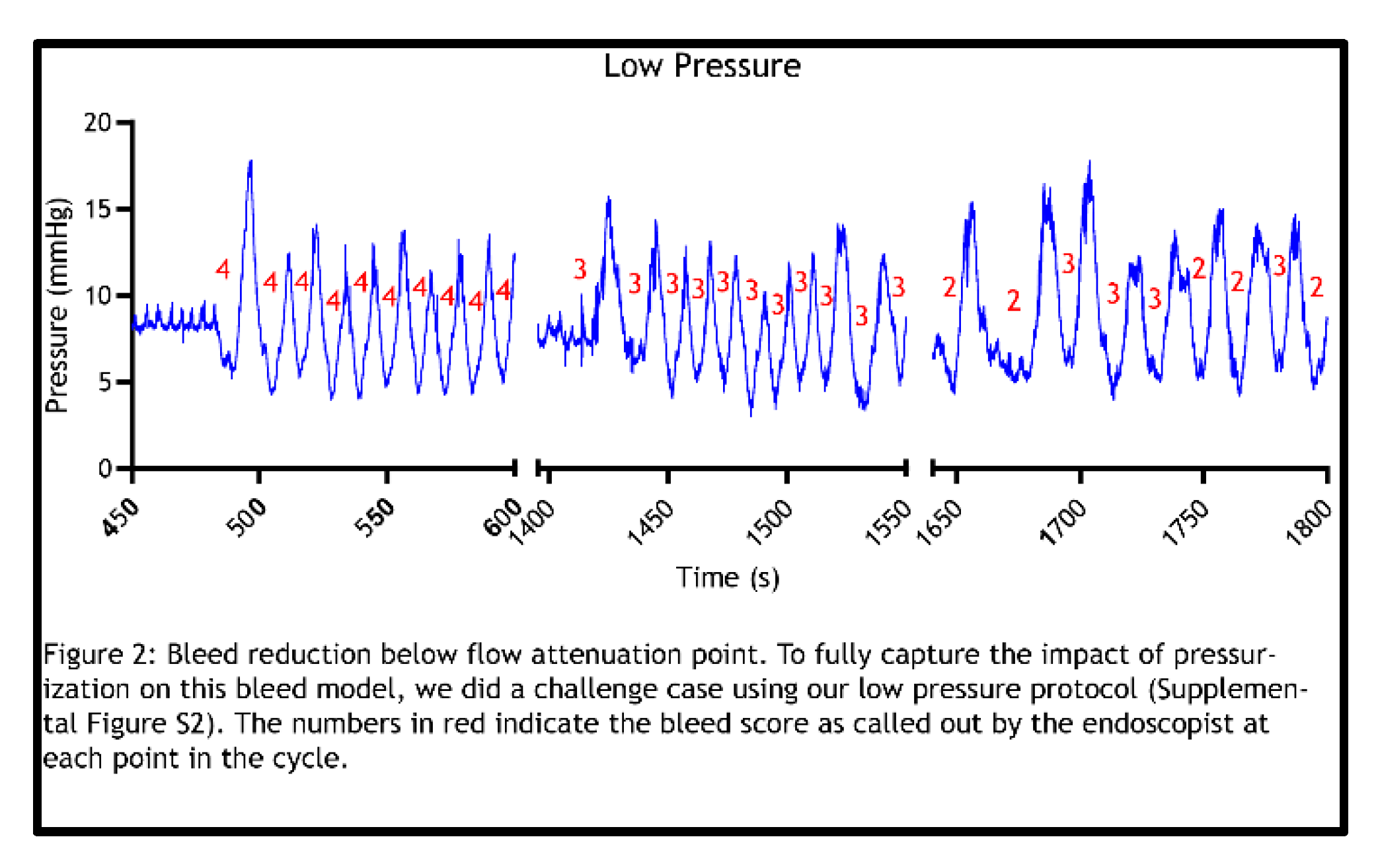

With the observation that pressure cycles representative of those used for spray device material application (pre- and post-puncture) completely attenuate flow, further studies were pursued to determine how blood flow is impacted if the pressurization cycle is conducted using shorter spray times, thereby achieving lower intragastric pressure (

Figure S3). These studies were considered the “Low Pressure” studies and were carried out across 3 animals (Figure 2). Unlike the previous high-pressure cycles, which corresponded with longer spray times, these low-pressure cycles did not demonstrate complete flow stoppage, since bleeds persisted at maximum intragastric pressures, as denoted by the bleed rating scores (> 0) obtained with each pressurization cycle. However, regardless of incomplete flow attenuation at each cycle’s max pressure, flow degradation occurred over time with multiple low-pressure cycles. This degradation in flow with progressing low-pressure cycles was demonstrated by the trending drop-off of bleed rating scores. 3/3 of animals showed a decrease in bleed severity scoring with low-pressure cycling. 1/3 animals in the study reached hemostasis within the time constraints placed on the study at “low pressures”.

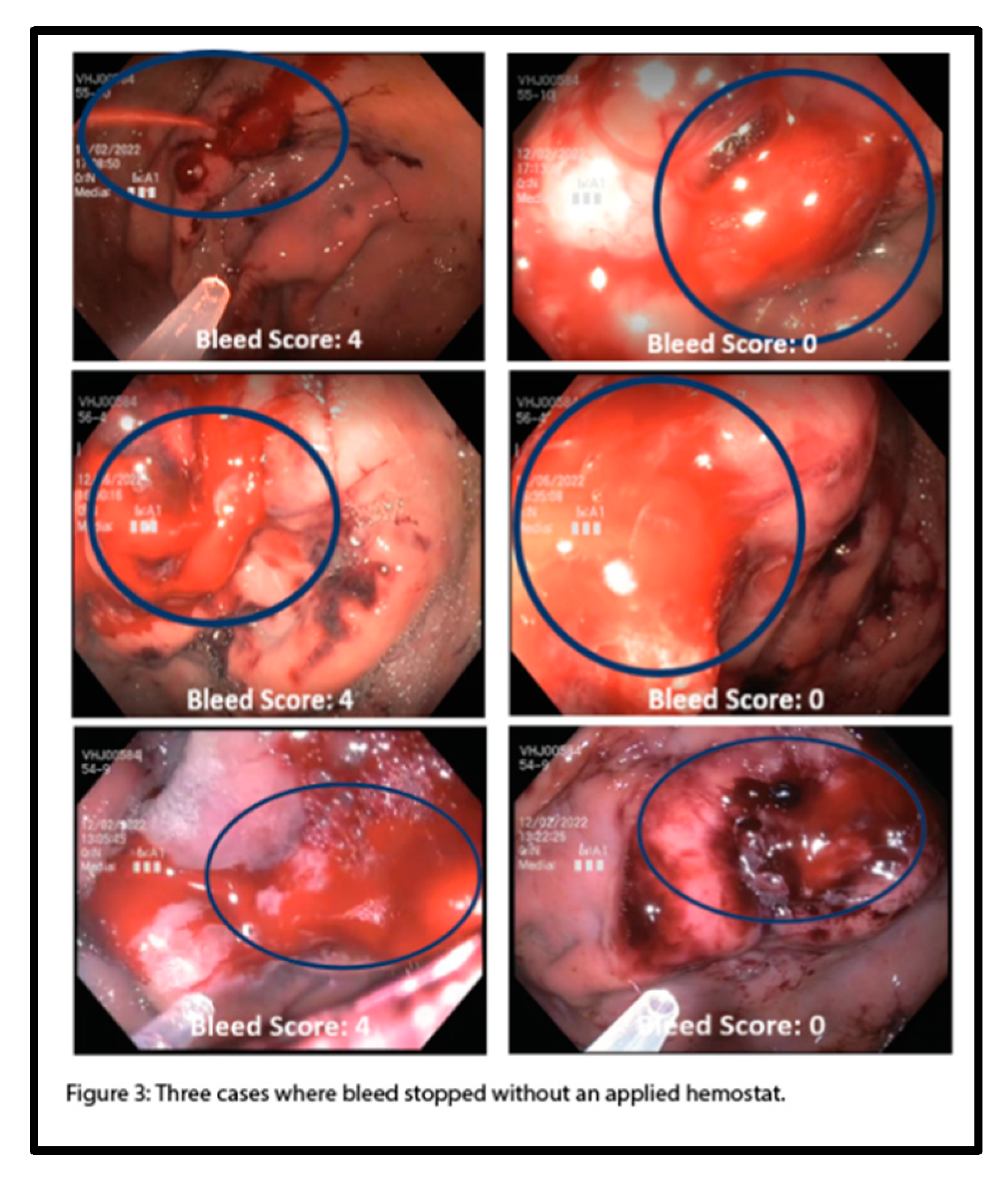

Hemostasis can be achieved as a function of intragastric pressure: Hemostasis was defined as “achieved” in these experiments when, within 40 minutes of post-puncture insufflation cycles, the bleed ceased for 10 minutes following desufflation. In 7 total animals tested, 5 animals achieved hemostasis without any hemostatic application. Images depicting 3 separate cases in which hemostasis was achieved, as assessed by bleed ratings, are shown in Figure 3. Following puncture, bleeds were scored as “4” (F1a), and in these cases, bleeding subsequently ceased (bleed score “0”) after cycles of CO2 were applied without a hemostatic agent.

Discussion

The Giday et al. porcine gastric vessel bleed model, which is widely used to evaluate hemostatic products, is considered the “gold standard” in the field of endoscopy. A primary concern that prompted reevaluation of the Giday et al. model is the nature of the sham control, i.e., the negative (no powder) control required for accurate evaluation and comparison to the endoscopically applied test powders. In the 2011 Giday et al. study, a single pulsatile bleed was created [

3]. The study consisted of 5 treatment animals receiving the hemostatic powder under investigation (TC-325). Giday et al. report that an additional 5 animals were assigned to a sham control group. Animals in this group underwent the gastric bleed procedure and received no endoscopic treatment. 5/5 treatment animals achieved acute hemostasis, while 0/5 sham control animals achieved acute hemostasis. With a clear distinction between both groups, Giday et al. determined that “TC-325 is safe and highly effective in achieving hemostasis in an anticoagulated severe arterial gastrointestinal bleeding animal model” [

3].

Giday et al. then conducted a 2013 GLP study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of Hemospray™ (Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) by employing the same vessel bleed model used in the 2011 Giday et al. study [

6]. The results indicated that 6/6 treatment animals achieved acute hemostasis. The exclusion of a control group was justified by citing the sham control results from the 2011 Giday et al. study [

3]. In a more recent 2021 study, Ali-Mohamad et al. evaluated a self-propelling thrombin powder (SPTP) for managing severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding [

5]. 12/12 treatment sites achieved acute hemostasis. Ali-Mohamad et al. expressed that future studies require a comparative control group that receives no powder.

These vessel bleed model studies describe the use of sham controls where the artery is punctured and allowed to bleed without hemostatic intervention for the duration of a defined observation time but fail to test the impact of the ancillary administration device which pressurizes the gastric lumen. To our knowledge, no studies published to date incorporated a true sham control, i.e., one in which gas is endoscopically delivered through the application catheter without the presence of the test material. Our examination of this previously untested (control) condition allowed for investigation into the effect of clinically relevant intragastric pressures on bleed reduction or hemostasis in this model and led to a comprehensive, critical evaluation of the Giday et al. model.

Following the foundational laws of fluid mechanics, a pressure differential is what drives flow. Since the Giday et al. model is an endoscopic bleed model that involves insufflation and therapeutic application utilizing gas, intragastric pressure fundamentally plays a role in blood flow. Moreover, there is inherent variability of insufflation pressures and bleed volumes achieved during such endoscopic procedures, which can alter pressure, and thus, blood flow rate. The established vessel bleed model, however, does not incorporate quantitative measurement of intragastric pressures. Additionally, while executing this study, the subjective nature of the model’s bleed scoring method, used to measure bleed severity and to determine if/when blood flow slows or stops, also became evident. This model is designed to test hemostatic powders that effectively cover a bleed site. However, our testing suggests that accurate assessment of changes in bleed severity—such as distinguishing between a fully stopped bleed and a slow, oozing one—would be incredibly challenging to achieve by visual detection, especially when the bleeding is concealed beneath the applied material. To explore the model's limitations, we incorporated both pressure and flow rate measurements. By including quantitative data, we eliminated bias in assessing hemostasis and enabled a means for precise quantification of different bleed severity levels (i.e., bleed scoring). Graphical representation of these endpoints clearly illustrated the relationship between intragastric pressure and bleed flow in this model.

One noted modification of the Giday et al. model employed in our study was the use of the splenic artery in place of the gastroepiploic artery. Similar physiological responses occur and apply, regardless of the vessel used. We observed that gastroepiploic bleeds regularly yield less aggressive (F1b) bleeds. These observations are consistent with bleed ratings obtained in previous studies using the Giday et al. model [

6,

7]. Use of the splenic artery predominantly yields aggressive bleeds, supporting its use in this hemostasis model for testing Forrest 1a bleeds.

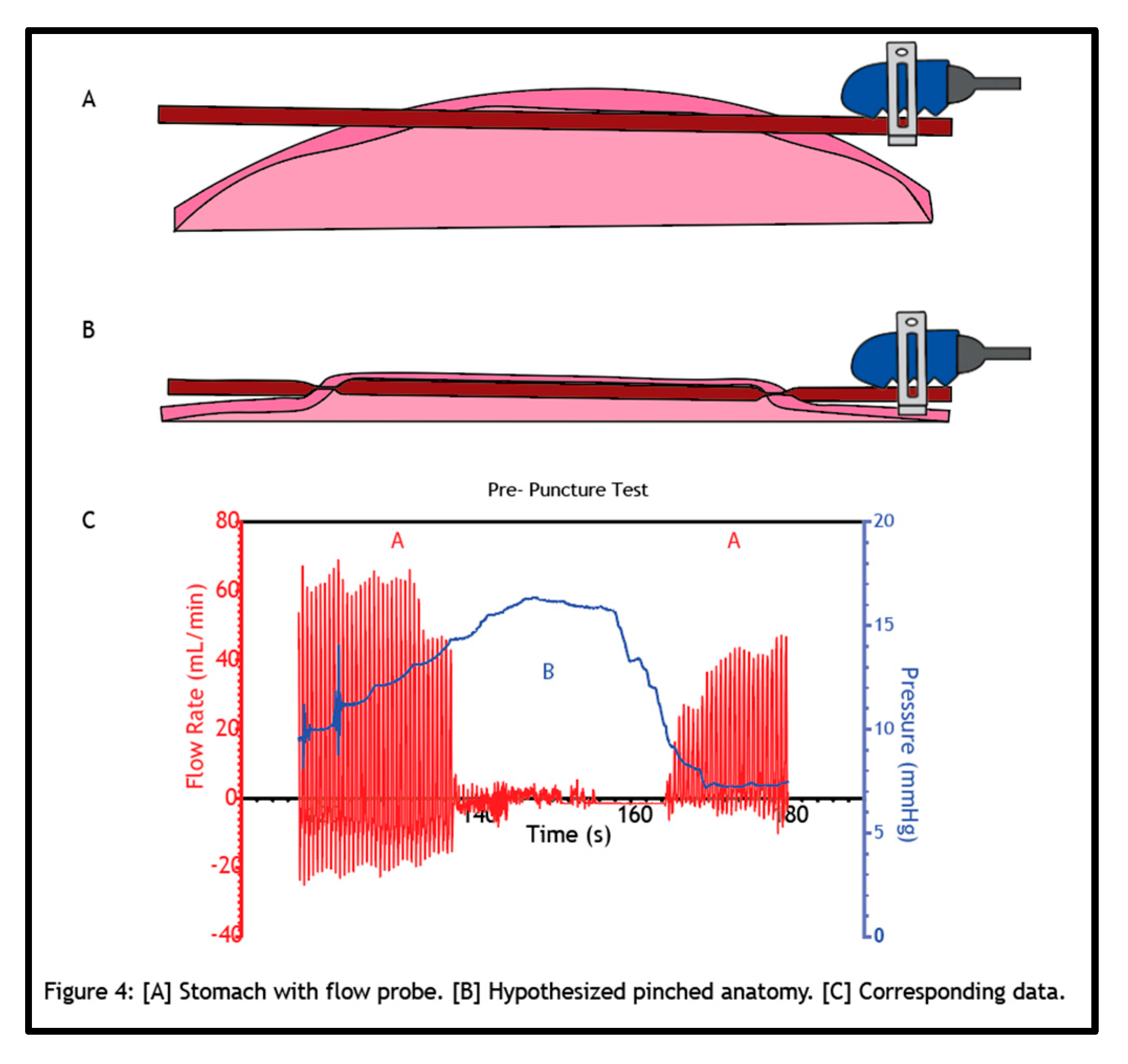

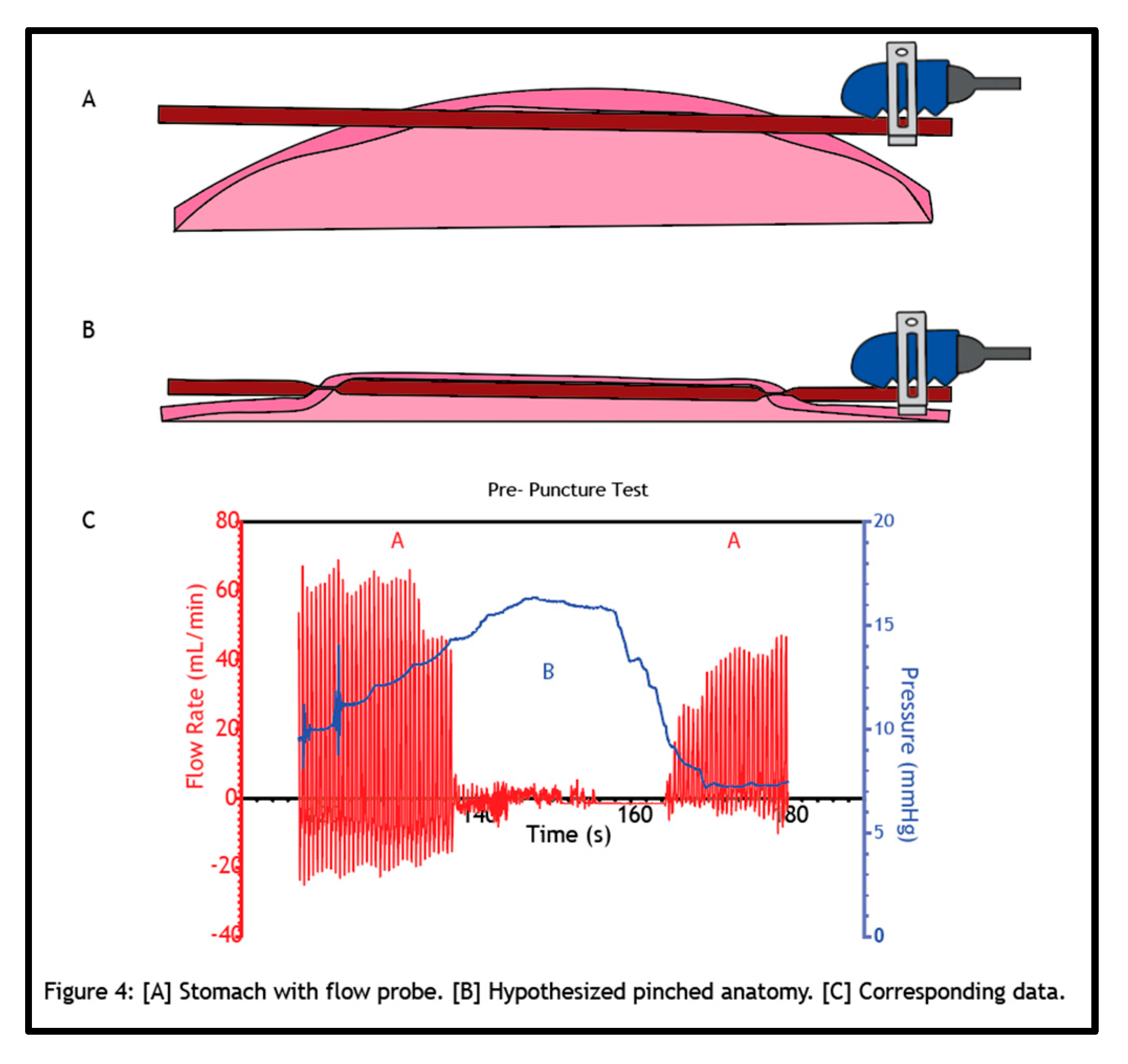

Figure 4 illustrates our hypothesis of what is occurring when pressurizing the stomach in this model. The splenic artery is sutured tightly within the stomach and flow persists without issue following a stabilization period (Figure 4A). When a hemostatic powder is applied, driven by pressurized air, the stomach wall expands, collapsing the artery (Figure 4B). This is similar to how a blood pressure cuff functions. A blood pressure cuff must exceed the pressure within the artery to occlude the vessel. When this happens, flow through the artery stops. As pressure is relieved from the cuff, flow restores slowly, and this flow restoration is what is detected when a blood pressure test is conducted. The same mechanism applies here when the intragastric pressure meets, and further exceeds, that of the splenic artery; the stomach collapses the sutured artery and thus “pinches” the artery. The stomach fundamentally acts as a pressure cuff to completely attenuate blood flow. The relationship between pressure and flow rate in the pre-puncture test as it corresponds to the open and occluded vessel states is illustrated below (Figure 4C).

A vessel “pinch-off point”, i.e., the pressure at which blood flow through the vessel stops, was observed in every animal. We hypothesize that this pinch-off point has greater effects beyond just temporarily impeding blood flow. Mechanical pinching that impedes flow and narrowing within an artery can lead to cascading events. This can result in a sustained decrease or even complete attenuation of flow. One of these events is vasospasm, the narrowing of arteries due to a persistent contraction of the blood vessels. We detected signs of vasospasm occurring on multiple occasions, as flow restoration was diminished after desufflating the stomach (Figure 1B, 1C, and Figure 2). We postulate that mechanical manipulation of the artery can lead to its vasoconstriction, resulting in spasming and reduced blood flow. The effect of physical manipulation of the vessel as a function of surgical implantation, intragastric pressurization cycles, or importantly, the introduction of gas into the system upon application of hemostatic agents, on the flow status of bleeds is a primary concern associated with this vessel bleed model.

It could be argued that staying below the pressure pinch-off value would be sufficient to justify the continued use of this bleed model. However, our “low-pressure” studies lend a different argument. We observed that even though the vessel is never pinched due to pressure, the bleeding can still stop. Vasoconstriction that occurs in this model upon artery implantation and/or tissue puncture may be intensified by vasospasm as a function of repeated pressure cycling – even if only reaching pressures well below any physical pinch-off point. This could explain the slowing and/or stopping of blood flow observed in the low-pressure tests.

Another potential explanation for intragastric pressure-induced hemostasis is the change in shear that occurs with altering the flow-pressure differential. Pressure drives fluid flow, and as the stomach pressure increases, the pressure differential between the bleed and the stomach decreases. This reduces the flow of blood from the vessel into the stomach. This reduction in flow in turn decreases shear stress experienced at the defect site. This can directly impact platelet activation and adhesion. A pierced vessel wall will attract platelets, but with high shear rates, platelets will have a difficult time adhering and plugging the bleed. Additionally, high shear rates trigger nitric oxide release by the endothelium, which prevents platelet adhesion. When these shear rates decrease due to increased pressure and a decreased pressure differential, there is a reduction in nitric oxide synthesis and an increase in the activation of platelets. Thus, with a decreased pressure differential, reduced flow, and lower shear, platelets have a better chance of plugging, slowing, or stopping a bleed, and contributing to the signaling events that produce a full-fledged fibrin clot.

The likelihood that platelets can play a role in bleed cessation within this model cannot be overstated. This is due to one major challenge with using a porcine bleed model for hemostasis studies; pigs are hypercoagulative [

4,

10,

11,

12]. Bleeding is difficult to induce in swine during endoscopic procedures due to higher coagulation and platelet aggregation levels [

13,

14]. For upper GI ulcer bleed models, pigs are rendered ‘bleeders’ equivalent to non-medicated humans by pretreatment with anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs which are administered before and during the endoscopic procedure [

7]. Thus, hemostatic efficacy is currently being determined using this model, which is inherently hypercoagulative. The potential for false-positive hemostasis justifies confirmation, that in this model, bleeds induced in pigs are not stopping on their own due to platelet plugging or coagulation, even when no hemostatic material is applied (sham control).

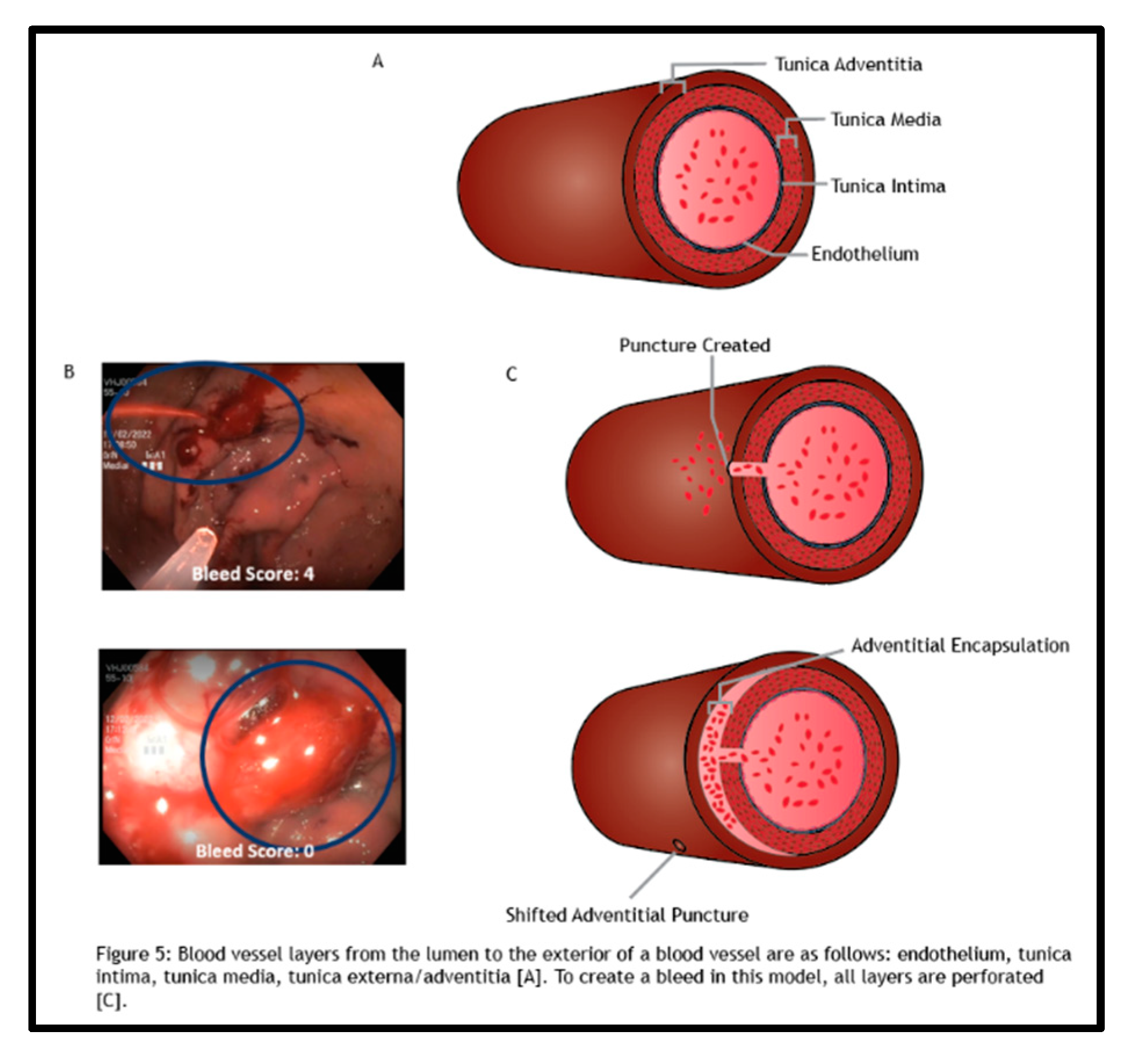

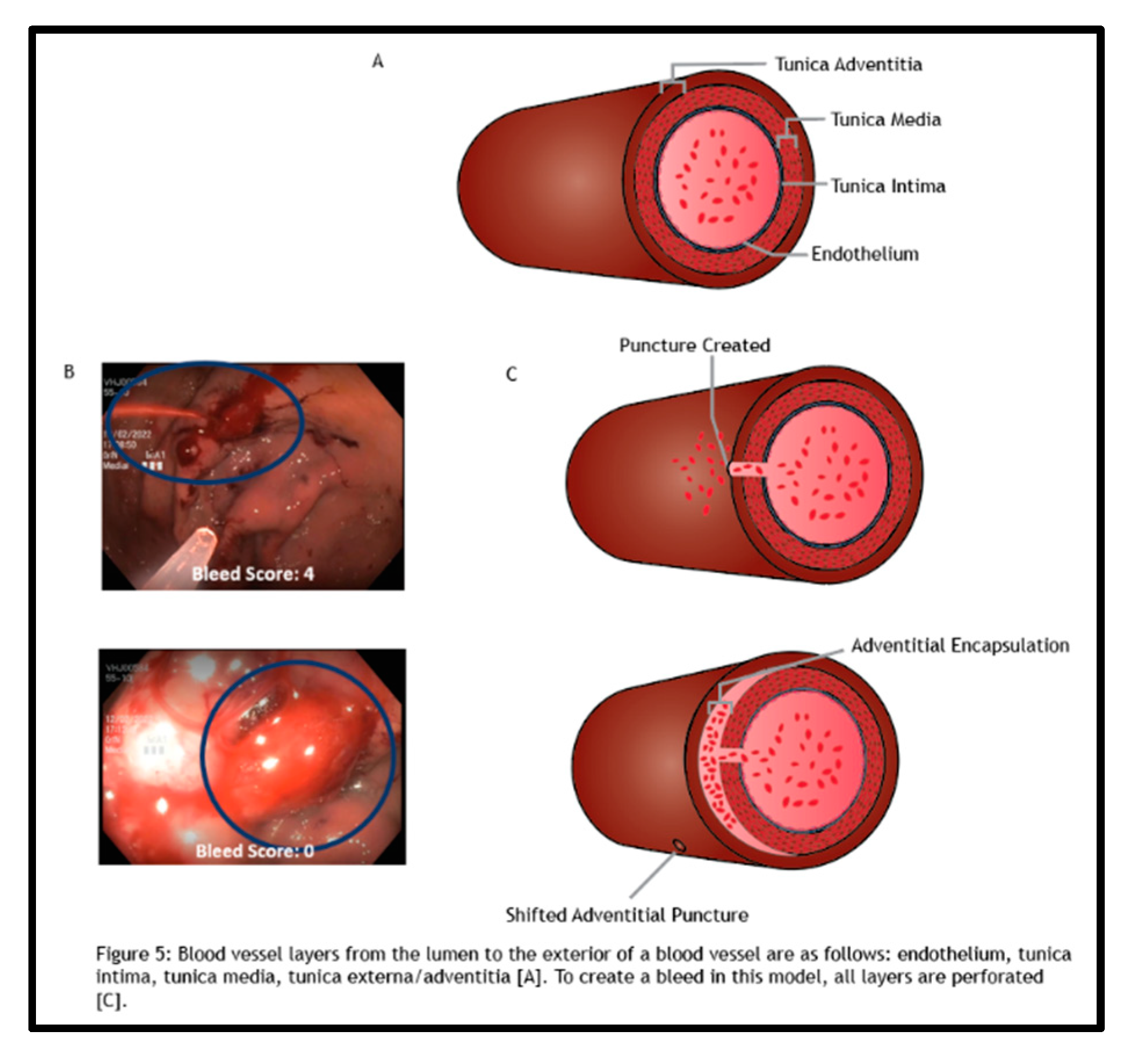

Even if we could keep platelets at bay using antiplatelet therapies while staying below a certain threshold pressure in this model, other confounding factors may be operating. One example detected within this model was adventitial encapsulation. The implanted splenic artery is composed of multiple layers of tissue (Figure 5A). Upon puncture for the creation of the test bleed in this model, all these layers are perforated. However, some bleeds were observed to stop, following extensive swelling of the artery (Figure 5B). This indicates that the outermost layer of the artery, the tunica adventitia, was shifting and encapsulating the bleed site, resulting in a bleed score of “0”, and achieving apparent hemostasis (Figure 5C). This artifactual event has likely occurred in a multitude of animal studies utilizing this model but had yet to be detected due to hemostatic application blocking the view of the test artery and determination of hemostasis using the subjective bleed scoring method.

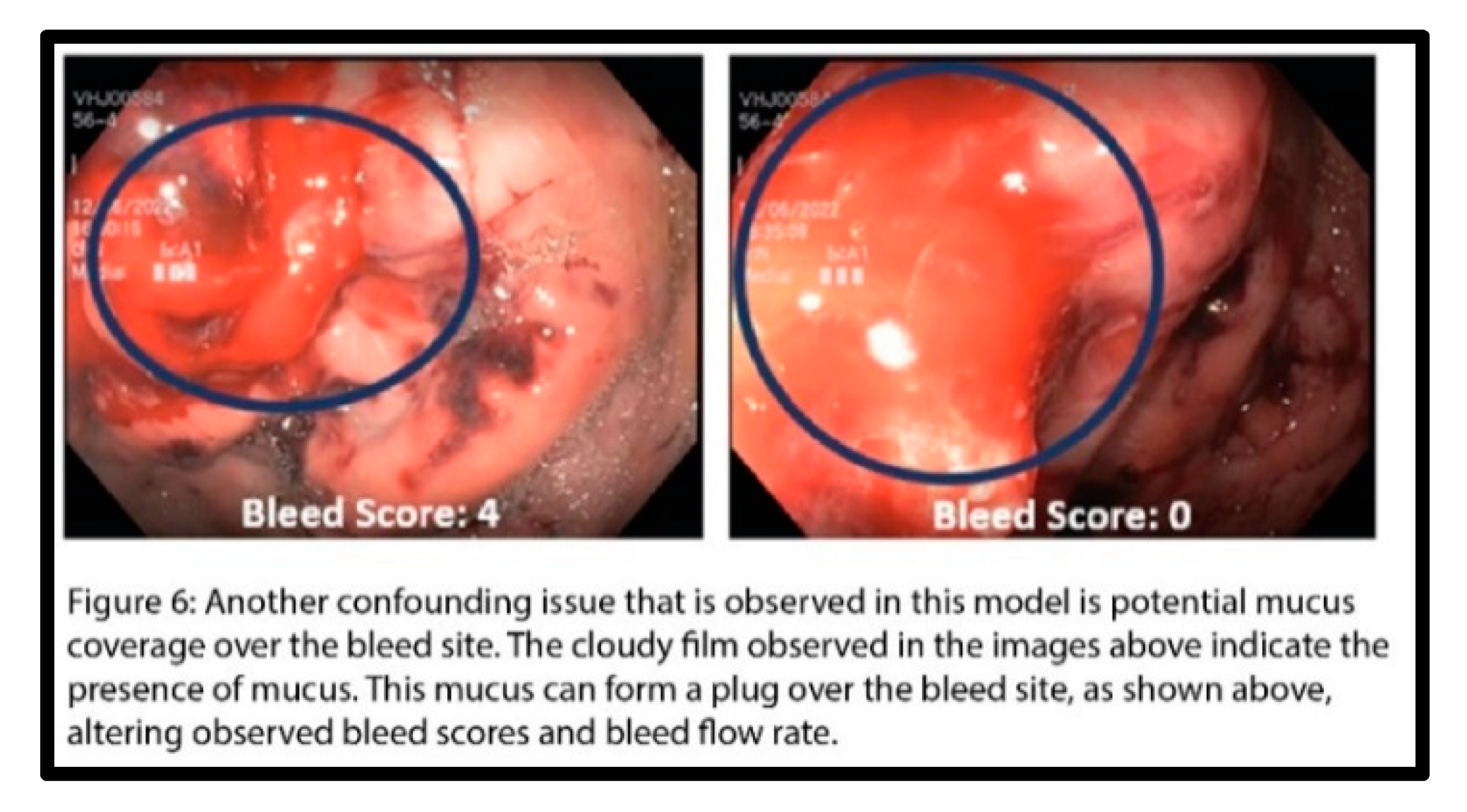

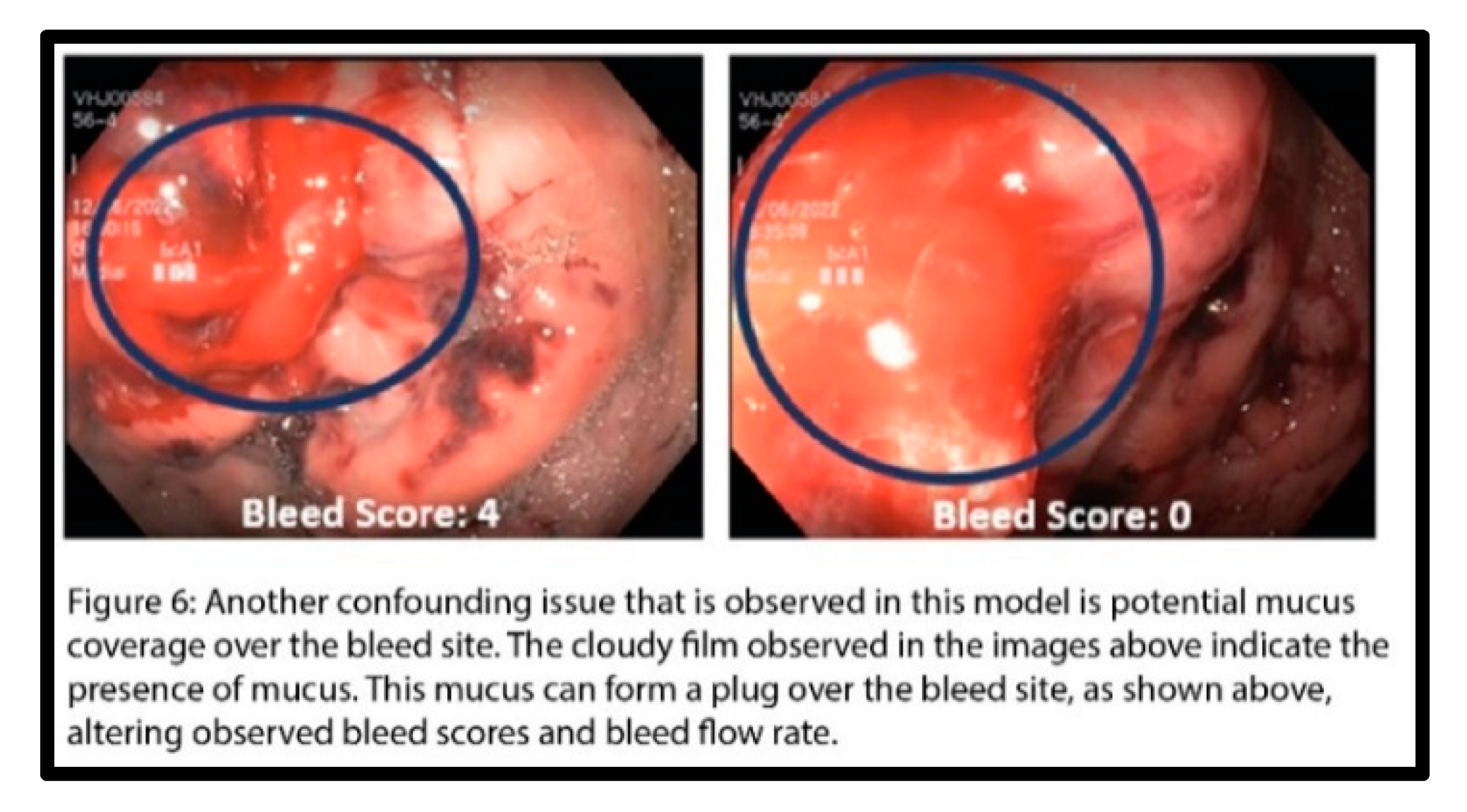

One last mode potentially leading to confounding data in this model is the impact of mucus. Figure 6 shows the formation of a substantial mucus plug over the defect site. This mucus plug was observed to both decrease and deflect the flow of the bleed, leading to hemostasis. As a result, the bleed rating would be skewed, leading to a false assumption of achieved hemostasis. This mucosal artifact would be easily overlooked when applying a test hemostatic agent in this model, which would obfuscate the defect site from view, with its hemostatic efficacy going unchallenged.

Interestingly, this model’s failure mode as a function of intragastric pressure was further reinforced by an observation made in one test animal. Acute hemostasis was achieved and maintained out to the defined 40-minute observation window. However, after an hour, the bleed reinitiated. There are a few different scenarios that might explain this occurrence. One might be that the pressure-induced mechanical manipulation of the vessel, which had stopped the bleed, could have been reversed by vasorelaxation that occurs over time, restoring the bleed. It is also possible that the bleed could have been reinstated after time if the platelet plug that had formed lost integrity with restoration of blood flow and increased shear. In addition, reinitiation of a bleed due to changing conditions following artifactual adventitial encapsulation-induced hemostasis, e.g. rupture of the adventitia, or fluctuations in anti-thrombotic drug regimens over time also could have occurred. This unexplained re-bleed event, following achieved hemostasis, although occurring outside the boundary of the defined study, suggests yet another example of how inherent pressure-dependent effects may compromise this model.

If an endoscopic resection model that simulates diffuse, low severity (F1b) ulcer bleeds were to be used as an alternative to this F1a vessel bleed model, the pressure effect would most likely also invalidate its use. Although no true sham controls have yet been included in F1b bleed studies to date, and further inquiry into established endoscopic F1b bleed models is warranted, it can be rationalized that the intragastric pressure effect observed in the vessel bleed model would be exacerbated in an endoscopic model simulating diffuse capillary bleeds. Capillary intraluminal pressure is very low (~2mmHg), much lower than that of arteries. With minimal CO2 application, i.e., at pressures commonly achieved in any endoscopic procedure that involves insufflation, intragastric pressure would reach and further exceed the low intraluminal pressures of capillaries, causing the diffuse F1b ulcer bleeds to stop. Thus, the pressure effect identified using this vessel bleed model also implicates established in vivo endoscopic bleed models currently used for efficacy testing of hemostats indicated for lower grade (F1b) bleeds.

When comparing the gastric vessel bleed model vs. a true ulcer bleed model, it should also be noted that the interaction between the test material and the surgically implanted vessel does not simulate therapeutic application in the true disease state, i.e., the hemostatic material-mucosal/submucosal tissue interaction that would occur in an ulcer bleed scenario. The vessel bleed model may prove adequate for testing the material application by devices in an endoscopic training environment and any mechanical mechanisms of acute hemostasis in the case of F1a bleeds. However, the lack of physiological relevance of the vessel bleed model for testing hemostatic powder efficacy in terms of material exposure to ulcer bleeds, ulcer tissue, and/or any biological hemostatic mechanisms of action that may be at play should be considered.

Some of these concerns echo those addressed in a recent review of porcine hemostasis models, bringing to light specific limitations of these bleed models and underscoring the complexity of animal models altogether [

8]. We acknowledge that a lot of the limitations in this model are challenging to work around. For example, having multiple cycles of insufflation is an inherent part of using this model for testing hemostatic powder, as insufflation is always required, and powder is applied using CO

2/gas for such endoscopic procedures. If quantitative flow and pressure data could always be collected when using this model, it would be an improvement over its current state and its subjective bleed scoring method used for assessing hemostasis. This study also still implicates risk in employing an F1b bleed model as an alternative, since intragastric pressure always plays a critical role. Additionally, the hypercoagulative nature of pigs and the required dosing of anti-coagulative and anti-platelet therapies, while challenging, must be considered for all studies and also if attempting to apply the Giday et al. vessel bleed model for chronic studies and the evaluation of hemostatic therapies for the prevention of re-bleeds. Moreover, the effects of anesthesia (isoflurane) plus blood pressure medication (phenylephrine) on this hemostasis model are yet undetermined since phenylephrine acts as a vasoconstrictor and isoflurane as a vasodilator. The combination of these confounding factors – intragastric pressure, resulting vasospasm, hypercoagulation, the surgical drug regimen, and the many additional factors that go uncontrolled in a complex in vivo model are not easily remedied. Undeniably, these aspects represent common “clinical” UGIB scenarios. However, these factors certainly confound hemostasis models when the aim of the model is to measure hemostatic efficacy or determine a material’s mechanism of action, instead of the model being used solely as a clinical training module for the simulation of real-life bleeds.

Together, these multiple constraints of the current state porcine gastric vessel bleed model underscore that there is an urgent need to develop more robust bleed models for accurate testing of endoscopic hemostatic devices. Benchtop studies using test methods developed to specifically parse out hemostatic properties can allow for mechanism of action studies, material characterization, and down selection, before testing hemostats In Vivo. Although investigation into alternative animal models for testing endoscopic bleed therapies was out of the scope of this study, the requirement for an appropriate sham control arm in any animal study became evident. We recommend future hemostatic testing of prototype therapies indicated for gastric bleeds be conducted outside of a pressurized environment and not directly atop arteries. While study criteria often dictate that evaluation of device performance is carried out in “clinically relevant environments”, sufficing to match the target anatomy does not ensure a scientifically sound in vivo model. Often, as demonstrated in this study, risk factors that lead to “clinical irrelevance” can still ensue. We propose that an appropriate substitute for this model could be a liver biopsy bleed or femoral bleed model for testing hemostatic agents [

16,

17,

18]. This would allow for a test environment that is not impacted by pressure or other confounding variables described throughout this paper. Additionally, in the case of the liver biopsy bleed model, this would provide for numerous test bleeds within one animal, reducing animal use. This is contrary to the gastric vessel bleed model, which allows for only one test bleed per porcine vessel.

In this study, testing the effect of endoscopically delivered gas via the application catheter without the accompanying hemostatic material allowed for critical evaluation of the established vessel bleed model. Multiple routes leading to false positive hemostasis were discovered. Future iterations of this model, which should include the incorporation of appropriate sham controls, should be vetted to avert the influence of the many potential confounding factors, as well as any issues not yet discovered by way of this limited 7-animal study. This study was critical to the realization that a modified version of the porcine gastric vessel bleed model, in its current state, or an alternative model, should be developed to accurately assess the safety and efficacy of endoscopic hemostatic therapies targeting UGIB.