Submitted:

30 October 2024

Posted:

31 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Long Non-Coding RNA (lncRNA)

2.1. Role of lncRNAs in Gene Expression

2.1.1. Chromatin Structure Regulation:

2.1.2. Regulation of Transcription by lncRNA:

2.1.3. Role of lncRNA in Post-Transcriptional Regulation:

2.2. Role of lncRNA in Innate Antiviral Response

2.3. Role of lncRNA In Virus Pathogenesis

2.3.1. LncRNA In Viral Gene Expression:

2.3.2. LncRNA In Viral Replication:

2.3.3. LncRNA In Viral Assembly and Release:

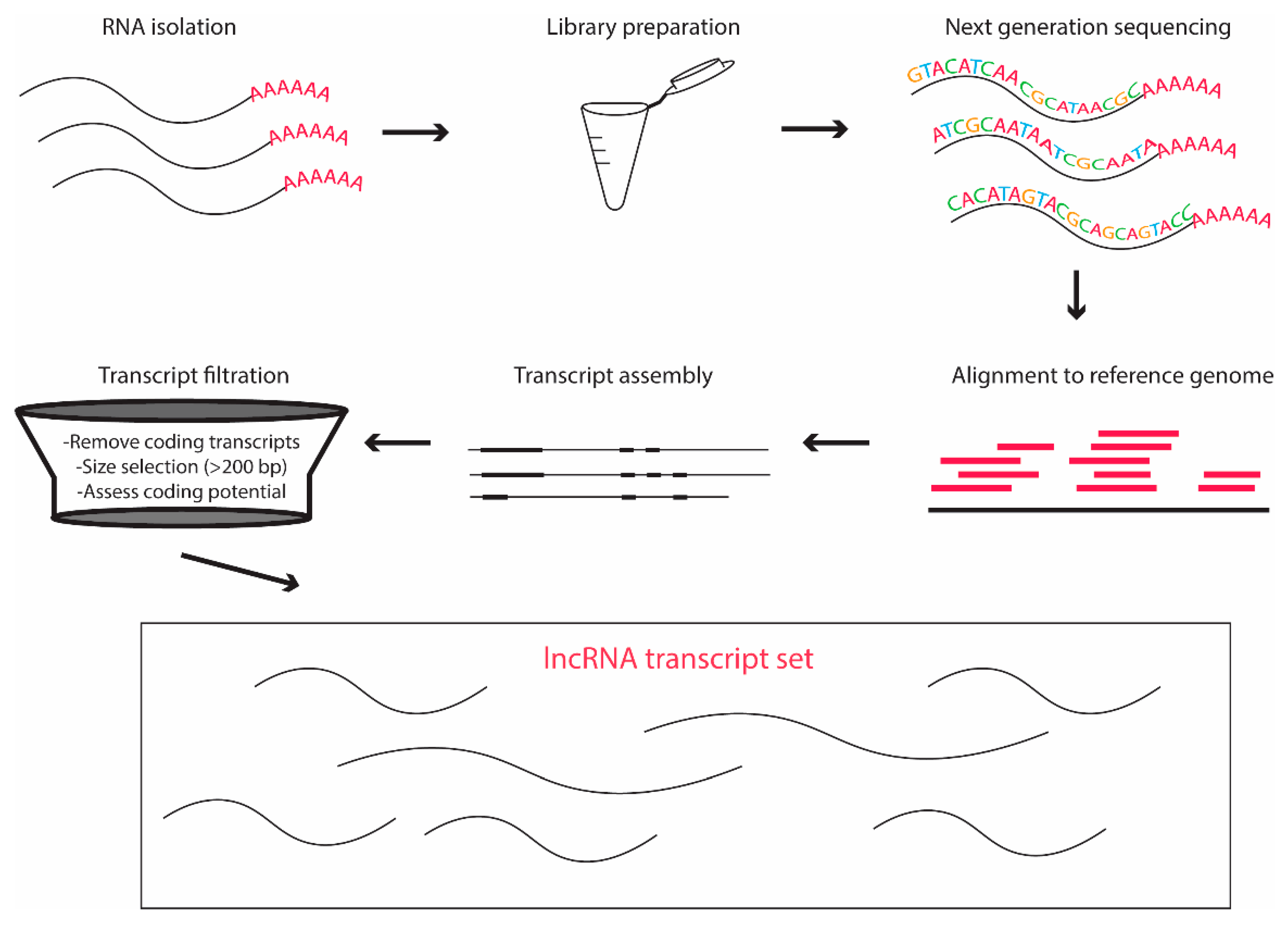

2.4. Methods of Detecting lncRNA

2.4.1. Full- Length cDNA Sequencing:

2.4.2. Chromatin State Maps:

2.4.3. RNA Sequencing:

2.5. Role of lncRNAs in Specific Chicken Viral Diseases

2.5.1. Avian Leucosis:

2.5.2. Marek’s Disease:

2.5.3. Infectious Bursal Disease (Gumboro Disease):

2.5.4. Avian Influenza:

2.5.5. Infectious Bronchitis:

2.5.6. Newcastle Disease:

Conclusion

References

- Funk, A.; Truong, K.; Nagasaki, T.; Torres, S.; Floden, N.; Balmori Melian, E.; Edmonds, J.; Dong, H.; Shi, P.-Y.; Khromykh, A.A. RNA Structures Required for Production of Subgenomic Flavivirus RNA. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 11407–11417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altfeld, M.; Gale, M Jr. Innate immunity against HIV-1 infection. Nat Immunol. 2015, 16, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, H.; Cai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, D.X.; Fang, S. Identification and formation mechanism of a novel noncoding RNA produced by avian infectious bronchitis virus. Virology 2019, 528, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacon, L.D. The National Registry of Genetically Unique Animal Populations: USDA-ADOL Chicken Genetic Lines. National Animal Germplasm Program: East Lansing, MI, USA,2002.

- Bamunuarachchi, G.; Pushparaj, S.; Liu, L. Interplay between host non-coding RNAs and influenza viruses. RNA Biol. 2021, 18, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banani, S.F.; Lee, H.O.; Hyman, A.A.; Rosen, M.K. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchereau, J.; Steinman, R.M. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 1998, 392, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniushin, B.F. Methylation of adenine residues in DNA of eukaryotes. Mol. Biol. 2005, 39, 557–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, X.; Wu, H.; Zhu, X.; Guo, X.; Hutchins, A.P.; Luo, Z.; Song, H.; Chen, Y.; Lai, K.; Yin, M.; et al. The p53-induced lincRNA-p21 derails somatic cell reprogramming by sustaining H3K9me3 and CpG methylation at pluripotency gene promoters. Cell Res. 2014, 25, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beermann, J.; Piccoli, M.-T.; Viereck, J.; Thum, T. Non-coding RNAs in Development and Disease: Background, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Approaches. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 1297–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, M.; Puig, I.; Pena, C.; Garcia, J.M.; Alvarez, A.B.; Pena, R.; Bonilla, F.; de Herreros, A.G. A natural antisense transcript regulates Zeb2/Sip1 gene expression during Snail1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 756–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, B.E.; Kamal, M.; Lindblad-Toh, K.; Bekiranov, S.; Bailey, D.K.; Huebert, D.J.; McMahon, S.; Karlsson, E.K.; Kulbokas, E.J.; Gingeras, T.R.; et al. Genomic Maps and Comparative Analysis of Histone Modifications in Human and Mouse. Cell 2005, 120, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonetti, A.; et al. RADICL-seq identifies general and cell type-specific principles of genome-wideRNA–chromatin interactions. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.J.; Hendrich, B.D.; Rupert, J.L.; Lafrenière, R.G.; Xing, Y.; Lawrence, J.; Willard, H.F. The human XIST gene: Analysis of a 17 kb inactive X-specific RNA that contains conserved repeats and is highly localized within the nucleus. Cell 1992, 71, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnside, J.; Ouyang, M.; Anderson, A.; Bernberg, E.; Lu, C.; Meyers, B.C.; Green, P.J.; Markis, M.; Isaacs, G.; Huang, E.; et al. Deep Sequencing of Chicken microRNAs. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 185–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braconi, C.; Kogure, T.; Valeri, N.; Huang, N.; Nuovo, G.; Costinean, S.; Negrini, M.; Miotto, E.; Croce, C.M.; Patel, T. microRNA-29 can regulate expression of the long non-coding RNA gene MEG3 in hepatocellular cancer. Oncogene 2011, 30, 4750–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, C.C.; Pari, G. KSHV PAN RNA Associates with Demethylases UTX and JMJD3 to Activate Lytic Replication through a Physical Interaction with the Virus Genome. PLOS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, C.C.; Tarrant-Elorza, M.; Verma, S.; Purushothaman, P.; Pari, G.S. Regulation of viral and cellular gene expression by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus polyadenylated nuclear RNA. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 5540e5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena, C.; Hur, S. Antiviral Immunity and Circular RNA: No End in Sight. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 163–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnero, E.; Barriocanal, M.; Prior, C.; Pablo Unfried, J.; Segura, V.; Guruceaga, E.; Enguita, M.; Smerdou, C.; Gastaminza, P.; Fortes, P. Long noncoding RNA EGOT negatively affects the antiviral response and favors HCV replication. EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 1013–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carninci, P.; Kasukawa, T.; Katayama, S.; Gough, J.; Frith, M.C.; Maeda, N.; Oyama, R.; Ravasi, T.; Lenhard, B.; Wells, C.; et al. The Transcriptional Landscape of the Mammalian Genome. Science 2005, 309, 1559–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, D.; Elus, M. M.; Cook, J. K. A. Relationship between sequence variation in the S1 spike protein of infectious bronchitis virus and the extent of cross-protection in vivo. Avian pathology 1997, 26, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charley, P.A.; Wilusz, J. Standing your ground to exoribonucleases: Function of Flavivirus long non-coding RNAs. Virus Res. 2015, 212, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, R.; Singh, A.; Singh, P.K.; Teja, E.S.; Varshney, R. Dynamics of Marek’s disease in poultry industry. Pharma Innov. 2021, 10, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumeil, J.; Le Baccon, P.; Wutz, A.; Heard, E. A novel role for Xist RNA in the formation of a repressive nuclear compartment into which genes are recruited when silenced. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 2223–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.G.; Kim, M.V.; Chen, X.; Batista, P.J.; Aoyama, S.; Wilusz, J.E.; Iwasaki, A.; Chang, H.Y. Sensing Self and Foreign Circular RNAs by Intron Identity. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, N.R.; Heikel, G.; Michlewski, G. TRIM25 and its emerging RNA-binding roles in antiviral defense. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2020, 11, e1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Qu, K.; Zhong, F.L.; Artandi, S.E.; Chang, H.Y. Genomic Maps of Long Noncoding RNA Occupancy Reveal Principles of RNA-Chromatin Interactions. Mol. Cell 2011, 44, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, E.M.; Battistini, A. Early IFN type I response: Learning from microbial evasion strategies. Semin. Immunol. 2015, 27, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Feng, M.; Xie, T.; Zhang, X. Long non-coding RNA and MicroRNA profiling provides comprehensive insight into non-coding RNA involved host immune responses in ALV-J-infected chicken primary macrophage. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2019, 100, 103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, A.J.; Eberle, R.; Ehlers, B.; Hayward, G.S.; McGeoch, D.J.; Minson, A.C.; Pellett, P.E.; Roizman, B.; Studdert, M.J.; Thiry, E. The order Herpesvirales. Arch. Virol. 2008, 154, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerr, A. Predicting PPIs. Nature Methods 2012, 9, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, T.; Goujon, C.; Malim, M.H. HIV-1 and interferons: who's interfering with whom? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015, 13, 13–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonkoly, E.; Bata-Csorgo, Z.; Pivarcsi, A.; Polyanka, H.; Kenderessy-Szabo, A.; Molnar, G.; Szentpali, K.; Bari, L.; Megyeri, K.; Mandi, Y.; et al. Identification and Characterization of a Novel, Psoriasis Susceptibility-related Noncoding RNA gene, PRINS. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 24159–24167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, T.; Boumart, I.; Coupeau, D.; Rasschaert, D. Hyperediting by ADAR1 of a new herpesvirus lncRNA during the lytic phase of the oncogenic Marek’s disease virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 2973–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, R.; Delgado, S.; Gas, M.-E.; Carbonell, A.; Molina, D.; Gago, S.; De la Peña, M. Viroids: the minimal non-coding RNAs with autonomous replication. FEBS Lett. 2004, 567, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, P.; Morris, K.V. Long noncoding RNAs in viral infections. Virus Res. 2016, 212, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijlman, G.P.; Funk, A.; Kondratieva, N.; Leung, J.; Torres, S.; van der Aa, L.; Liu, W.J.; Palmenberg, A.C.; Shi, P.-Y.; Hall, R.A.; et al. A Highly Structured, Nuclease-Resistant, Noncoding RNA Produced by Flaviviruses Is Required for Pathogenicity. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 4, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Moreno,M. ;Jarvelin, A.I.; Castello, A. Unconventional RNA-binding proteins step into the virus-host battlefront. WIREs RNA 2018, 9, e1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebert, C.; Kunkel, D.; Grinberg, A.; Pfeifer, K. H19 Imprinting Control Region Methylation Requires an Imprinted Environment Only in the Male Germ Line. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, P.; Wittler, L.; Hendrix, D.; Koch, F.; Währisch, S.; Beisaw, A.; Macura, K.; Bläss, G.; Kellis, M.; Werber, M.; et al. The Tissue-Specific lncRNA Fendrr Is an Essential Regulator of Heart and Body Wall Development in the Mouse. Dev. Cell 2013, 24, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttman, M.; Amit, I.; Garber, M.; French, C.; Lin, M.F.; Feldser, D.; Huarte, M.; Zuk, O.; Carey, B.W.; Cassady, J.P.; et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature 2009, 458, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttman, M.; Russell, P.; Ingolia, N.T.; Weissman, J.S.; Lander, E.S. Ribosome Profiling Provides Evidence that Large Noncoding RNAs Do Not Encode Proteins. Cell 2013, 154, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ding, Y.; Lian, L.; Zhao, C.; Song, J.; Yang, N. Long intergenic non-coding RNA GALMD3 in chicken Marek’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartford, C.C.R.; Lal, A. When Long Noncoding Becomes Protein Coding. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Li, M.; Wei, P.; Mo, M.-L.; Wei, T.-C.; Li, K.-R. Complete Genome Sequence of an Infectious Bronchitis Virus Chimera between Cocirculating Heterotypic Strains. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 13887–13888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Han, B.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chang, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, C.; Yang, N.; Song, J. Linc-GALMD1 Regulates Viral Gene Expression in the Chicken. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintzman, N.D.; Stuart, R.K.; Hon, G.; Fu, Y.; Ching, C.W.; Hawkins, R.D.; Barrera, L.O.; Van Calcar, S.; Qu, C.; Ching, K.A.; et al. Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentze, M.W.; Castello, A.; Schwarzl, T.; Preiss, T. A brave new world of RNA-binding proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezroni, H.; Koppstein, D.; Schwartz, M.G.; Avrutin, A.; Bartel, D.P.; Ulitsky, I. Principles of Long Noncoding RNA Evolution Derived from Direct Comparison of Transcriptomes in 17 Species. Cell Rep. 2015, 11, 1110–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chen, S.; Jia, C.; Xue, S.; Dou, C.; Dai, Z.; Xu, H.; Sun, Z.; Geng, T.; Cui, H. Gene expression profile and long non-coding RNA analysis, using RNA-Seq, in chicken embryonic fibroblast cells infected by avian leukosis virus J. Arch. Virol. 2017, 163, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xu, Y.; Lin, Q.; Guo, W.; Zhao, D.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, Y.; Cui, W.; et al. Determination of antiviral action of long non-coding RNA loc107051710 during infectious bursal disease virus infection due to enhancement of interferon production. Virulence 2019, 11, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilott, N.E.; Ponting, C.P. Predicting long non-coding RNAs using RNA sequencing. Methods 2013, 63, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, R.; Kroehling, L.; Khitun, A.; Bailis, W.; Jarret, A.; York, A.G.; Khan, O.M.; Brewer, J.R.; Skadow, M.H.; Duizer, C.; et al. The translation of non-canonical open reading frames controls mucosal immunity. Nature 2018, 564, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Z.; Lin, H.; Zhu, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, W.; Liu, S.; Liu, W.; Ma, Y.; et al. Self-Recognition of an Inducible Host lncRNA by RIG-I Feedback Restricts Innate Immune Response. Cell 2018, 173, 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaujia, R.; Bora, I.; Ratho, R.K.; Thakur, V.; Mohi, G.K.; Thakur, P. Avian influenza revisited: concerns and constraints. VirusDisease 2022, 33, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.A.; Cairns, C.; Jones, M.J.; Bell,A. S.;Salathé, R.M.; Baigent, S.J. Industry-wide surveillance of Marek's disease virus on commercial poultry farms. Avian diseases 2017, 61, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzin, J.J.; Iseka, F.; Wright, J.; Basavappa, M.G.; Clark, M.L.; Ali, M.-A.; Abdel-Hakeem, M.S.; Robertson, T.F.; Mowel, W.K.; Joannas, L.; et al. The long noncoding RNA Morrbid regulates CD8 T cells in response to viral infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 11916–11925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statello, L.; Guo, C.-J.; Chen, L.-L.; Huarte, M. Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Wang, Y.; Tian, K.; Ye, F.; Yin, H.; Zhao, X.; Xu, H.; Huang, Y.; Liu, H.; Hsieh, J.C.F.; et al. Integrated host and viral transcriptome analyses reveal pathology and inflammatory response mechanisms to ALV-J injection in SPF chickens. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latos, P.A.; Pauler, F.M.; Koerner, M.V.; ¸Senergin, H.B.; Hudson, Q.; Stocsits, R.R.; Allhoff, W.; Stricker, S.H.; Klement, R.M.; Warczok, K.E.; et al. Airn Transcriptional Overlap, But Not Its lncRNA Products, Induces Imprinted Igf2r Silencing. Science 2012, 338, 1469–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kopp, F.; Chang, T.-C.; Sataluri, A.; Chen, B.; Sivakumar, S.; Yu, H.; Xie, Y.; Mendell, J.T. Noncoding RNA NORAD Regulates Genomic Stability by Sequestering PUMILIO Proteins. Cell 2015, 164, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.T. Epigenetic Regulation by Long Noncoding RNAs. Science 2012, 338, 1435–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.H.; Liu, S.; Zheng, L.L.; Wu, J.; Sun, W.J.; Wang, Z.L.; et al. Discovery of Protein-lncRNA Interactions by Integrating Large-Scale CLIP-Seq and RNA-Seq Datasets. Front BioengBiotechnol. 2014, 2, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chao, T.C.; Chang, K.Y.; et al. The long noncoding RNA THRIL regulates TNFalpha expression through its interaction with hnRNPL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 1002–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Sun, M.; Ma, C.; Liang, W.; Gao, X.; Wei, L. Long Noncoding RNA NRAV Promotes Respiratory Syncytial Virus Replication by Targeting the MicroRNA miR-509-3p/Rab5c Axis To Regulate Vesicle Transportation. J. Virol. 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, B.; Chen, L.; Gou, L.-T.; Li, H.; Fu, X.-D. GRID-seq reveals the global RNA–chromatin interactome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 940–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Jiang, M.; Liu, L.; Yang, Z.; Ma, Z.; Liu, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cao, X. The long noncoding RNA Lnczc3h7a promotes a TRIM25-mediated RIG-I antiviral innate immune response. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Xia, J.; Zhang, K.; Yang, Q. Genome-wide profiling of chicken dendritic cell response to infectious bursal disease. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ding, C. Roles of LncRNAs in Viral Infections. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Xing, Y.; Cai, H.; Shi, Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y. Identification and analysis of long non-coding RNAs in response to H5N1 influenza viruses in duck (Anas platyrhynchos). BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Lu, J.Y.; Liu, L.; Yin, Y.; Chen, C.; Han, X.; Wu, B.; Xu, R.; Liu, W.; Yan, P.; et al. Divergent lncRNAs Regulate Gene Expression and Lineage Differentiation in Pluripotent Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahanda, M.-L.E.; Ruby, T.; Wittzell, H.; Bed’hom, B.; Chaussé, A.-M.; Morin, V.; Oudin, A.; Chevalier, C.; Young, J.R.; Zoorob, R. Non-coding RNAs revealed during identification of genes involved in chicken immune responses. Immunogenetics 2008, 61, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Han, P.; Ye, W.; et al. The long noncoding RNA NEAT1 exerts anti-hantaviral effects by acting as positive feedback for RIG-I signaling. J Virol. 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Bajic, V.B.; Zhang, Z. On the classification of long non-coding RNAs. RNA Biol. 2013, 10, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Wei, J.; Maarouf, M.; Chen, J.-L. Involvement of Host Non-Coding RNAs in the Pathogenesis of the Influenza Virus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, J.A.; Laprade, L.; Winston, F. Intergenic transcription is required to repress the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SER3 gene. Nature 2004, 429, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martianov, I.; Ramadass, A.; Barros, A.S.; Chow, N.; Akoulitchev, A. Repression of the human dihydrofolate reductase gene by a non-coding interfering transcript. Nature 2007, 445, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFerran, J. B. "Infectious bursal disease." 1993, 51-56.

- Melé, M.; et al. Chromatin environment, transcriptional regulation, and splicing distinguishlincRNAs and mRNAs. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandas, S.S.; Thakur, M.; Gangil, R. A Mini-Review on Immunosuppressive Viral Diseases and their Containment Methods at Commercial Poultry Farms. Veterinary Immunology & Biotechnology 2018, 1, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, T.; Subhash, S.; Vaid, R.; Enroth, S.; Uday, S.; Reinius, B.; Mitra, S.; Mohammed, A.; James, A.R.; Hoberg, E.; et al. MEG3 long noncoding RNA regulates the TGF-β pathway genes through formation of RNA–DNA triplex structures. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.L.; Anderson, J.R.; Kumagai, Y.; Wilusz, C.J.; Akira, S.; Khromykh, A.A.; Wilusz, J. A noncoding RNA produced by arthropod-borne flaviviruses inhibits the cellular exoribonuclease XRN1 and alters host mRNA stability. RNA 2012, 18, 2029–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niehrs, C.; Luke, B. Regulatory R-loops as facilitators of gene expression and genome stability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 167–178 (2020). Tan-Wong, S. M., Dhir, S. & Proudfoot, N. J. R-loops promote antisense transcription across the mammalian genome. Mol. Cell. 2016, 76, 600–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, V.B.; Ovsepian, S.V.; Carrascosa, L.G.; Buske, F.A.; Radulovi´c, V.; Niyazi, M.; Mörtl, S.; Trau, M.; Atkinson, M.J.; Anastasov, N. PARTICLE, a triplex-forming long ncRNA, regulates locus-specific methylation in response to low-dose Irradiation. Cell Rep. 2015, 11, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, J.; Hu, J.; Chen, J. lncRNAs regulate the innate immune response to viral infection. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2015, 7, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang J, Zhu X, Chen Y, et al. NRAV, a long noncoding RNA, modulates antiviral responsesthrough suppression of interferon-stimulated gene transcription. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 16, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli, A.; Valen, E.; Lin, M.F.; Garber, M.; Vastenhouw, N.L.; Levin, J.Z.; Fan, L.; Sandelin, A.; Rinn, J.L.; Regev, A.; et al. Systematic identification of long noncoding RNAs expressed during zebrafish embryogenesis. Genome Res. 2011, 22, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Prasad, M. Host-virus interactions mediated by long non-coding RNAs. Virus Res. 2021, 298, 198402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, C.-Y.; Yedavalli, V.S.R.K.; Jeang, K.-T. NEAT1 Long Noncoding RNA and Paraspeckle Bodies Modulate HIV-1 Posttranscriptional Expression. mBio 2013, 4, e00596–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Chang, G.; Li, Z.; Bi, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, G. Comprehensive Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Competing Endogenous RNA Networks During Avian Leukosis Virus, Subgroup J-Induced Tumorigenesis in Chickens. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redon, S.; Reichenbach, P.; Lingner, J. The non-coding RNA TERRA is a natural ligand and direct inhibitor of human telomerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 5797–5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, R.E.; Rehwinkel, J. RNA degradation in antiviral immunity and autoimmunity. Trends Immunol. 2015, 36, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinn, J.L.; Kertesz, M.; Wang, J.K.; Squazzo, S.L.; Xu, X.; Brugmann, S.A.; Goodnough, L.H.; Helms, J.A.; Farnham, P.J.; Segal, E.; et al. Functional Demarcation of Active and Silent Chromatin Domains in Human HOX Loci by Noncoding RNAs. Cell 2007, 129, 1311–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rom, A.; et al. Regulation of CHD2 expression by the Chaserrlong noncoding RNA gene is essential for viability. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldaña-Meyer, R.; Rodriguez-Hernaez, J.; Escobar, T.; Nishana, M.; Jácome-López, K.; Nora, E.P.; Bruneau, B.G.; Tsirigos, A.; Furlan-Magaril, M.; Skok, J.; et al. RNA Interactions Are Essential for CTCF-Mediated Genome Organization. Mol. Cell 2019, 76, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salerno, D.; Chiodo, L.; Alfano, V.; Floriot, O.; Cottone, G.; Paturel, A.; Pallocca, M.; Plissonnier, M.-L.; Jeddari, S.; Belloni, L.; et al. Hepatitis B protein HBx binds the DLEU2 lncRNA to sustain cccDNA and host cancer-related gene transcription. Gut 2020, 69, 2016–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.M.; Chang, H.Y. Long Noncoding RNAs in Cancer Pathways. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, K.-M.; Mayer, C.; Postepska, A.; Grummt, I. Interaction of noncoding RNA with the rDNA promoter mediates recruitment of DNMT3b and silencing of rRNA genes. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 2264–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheiss,M. ;Thimme, R. Toll like receptor 7 and hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2007, 47, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seila, A.C.; Calabrese, J.M.; Levine, S.S.; Yeo, G.W.; Rahl, P.B.; Flynn, R.A.; Young, R.A.; Sharp, P.A. Divergent Transcription from Active Promoters. Science 2008, 322, 1849–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; Liu, X.; Yan, W.; Wang, M.; Li, H.; Jiang, S.; Wang, S.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yin, R. Long Non-Coding RNA Analysis: Severe Pathogenicity in Chicken Embryonic Visceral Tissues Infected with Highly Virulent Newcastle Disease Virus—A Comparison to the Avirulent Vaccine Virus. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.M.; Kim, I.-J.; Rautenschlein, S.; Yeh, H.-Y. Infectious bursal disease virus of chickens: pathogenesis and immunosuppression. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2000, 24, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirahama, S.; Miki, A.; Kaburaki, T.; Akimitsu, N. Long Non-coding RNAs Involved in Pathogenic Infection. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojic, L.; Niemczyk, M.; Orjalo, A.; Ito, Y.; Ruijter, A.E.M.; Uribe-Lewis, S.; Joseph, N.; Weston, S.; Menon, S.; Odom, D.T.; et al. Transcriptional silencing of long noncoding RNA GNG12-AS1 uncouples its transcriptional and product-related functions. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhakar, S.; Nair, A.J. Marek's disease: The never ending challenge - A review. International Journal of Pharma and Bio Sciences 2013, 4, B6–B11. [Google Scholar]

- Tahira, A.C.; Kubrusly, M.S.; Faria, M.F.; Dazzani, B.; Fonseca, R.S.; Maracaja-Coutinho, V.; Verjovski-Almeida, S.; Machado, M.C.; Reis, E.M. Long noncoding intronic RNAs are differentially expressed in primary and metastatic pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cancer 2011, 10, 141–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Innate immunity to virus infection. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 227, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thebault, P.; Boutin, G.; Bhat, W.; Rufiange, A.; Martens, J.; Nourani, A. Transcription Regulation by the Noncoding RNA SRG1 Requires Spt2-Dependent Chromatin Deposition in the Wake of RNA Polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011, 31, 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichon, A.; Perry, R.B.-T.; Stojic, L.; Ulitsky, I. SAM68 is required for regulation of Pumilio by the NORAD long noncoding RNA. Genes Dev. 2018, 32, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilgner, H.; Knowles, D.G.; Johnson, R.; Davis, C.A.; Chakrabortty, S.; Djebali, S.; Curado, J.; Snyder, M.; Gingeras, T.R.; Guigó, R. Deep sequencing of subcellular RNA fractions shows splicing to be predominantly co-transcriptional in the human genome but inefficient for lncRNAs. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1616–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, K.K.; Chan, J.F.; Chen, H.; Li, L.; Yuen, K.-Y. The emergence of influenza A H7N9 in human beings 16 years after influenza A H5N1: a tale of two cities. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisnic, V.J.; Cac, M.B.; Lisnic, B.; Trsan, T.; Mefferd, A.; Das Mukhopadhyay, C.; Cook, C.H.; Jonjic, S.; Trgovcich, J. Dual Analysis of the Murine Cytomegalovirus and Host Cell Transcriptomes Reveal New Aspects of the Virus-Host Cell Interface. PLOS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Berg, T.P.D. Acute infectious bursal disease in poultry: A review. Avian Pathol. 2000, 29, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Werven, F.J.; Neuert, G.; Hendrick, N.; Lardenois, A.; Buratowski, S.; van Oudenaarden, A.; Primig, M.; Amon, A. Transcription of Two Long Noncoding RNAs Mediates Mating-Type Control of Gametogenesis in Budding Yeast. Cell 2012, 150, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velloso, L.A.; Folli, F.; Saad, M.J. TLR4 at the Crossroads of Nutrients, Gut Microbiota, and Metabolic Inflammation. Endocr. Rev. 2015, 36, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, W.; Ben-Yehuda, D.; Hayward, W.S. bic, a Novel Gene Activated by Proviral Insertions in Avian Leukosis Virus-Induced Lymphomas, Is Likely To Function through Its Noncoding RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997, 17, 1490–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagari, A. A review on infectious bursal disease in poultry. Health Econ. Outcome Res. Open Access, 2021, 7, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Bao, Y.; Wu, Z.; et al. Long noncoding RNA EGFR-AS1 promotes cell growth and metastasis via affecting HuR mediated mRNA stability of EGFR in renal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cen, S. Roles of lncRNAs in influenza virus infection. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; et al. Influenza virus exploits an interferon-independent lncRNA to preserve viral RNA synthesis through stabilizing viral RNA polymerase PB1. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 3295–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, F.; Liu, C.Y.; et al. The long noncoding RNA NRF regulates programmed necrosis and myocardial injury during ischemia and reperfusion by targeting miR-873. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 1394–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Feng, W.; et al. Long noncoding RNA TSPOAP1 antisense RNA 1 negatively modulates type I IFN signaling to facilitate influenza A virus replication. J Med Virol. 2019, 94, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; et al. Human Bocavirus 1 Is a Novel Helper for Adeno-associated Virus Replication. J Virol. 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, D.; Li, Q.; Zhou, J.; Guo, F.; Liang, C.; et al. Host Long Noncoding RNA lncRNA-PAAN Regulates the Replication of Influenza A Virus. Viruses 2018, 10, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Gong, C.; Maquat, L.E. Control of myogenesis by rodent SINE-containing lncRNAs. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.C.; Chang, H.Y. Molecular Mechanisms of Long Noncoding RNAs. Mol. Cell. 2011, 43, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P. The Opening of Pandora’s Box: An Emerging Role of Long Noncoding RNA in Viral Infections. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 9, 3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Cao, X. An interferon-independent lncRNA promotes viral replication by modulating cellular metabolism. Science 2017, 358, 1051–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; McLachlan, J.; Zamore, P. D.; Hall, T. M. Modular recognition of RNA by a human Pumiliohomology domain. Cell 2002, 110, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilusz, J.E.; Sunwoo, H.; Spector, D. Long noncoding RNAs: Functional surprises from the RNA world. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 1494–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterling, C.; Koch, M.; Koeppel, M.; Garcia-Alcalde, F.; Karlas, A.; Meyer, T.F. Evidence for a crucial role of a host non-coding RNA in influenza A virus replication. RNA Biol. 2013, 11, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Gralinski, L.; Armour, C.D.; Ferris, M.T.; Thomas, M.J.; Proll, S.; Bradel-Tretheway, B.G.; Korth, M.J.; Castle, J.C.; Biery, M.C.; et al. Unique Signatures of Long Noncoding RNA Expression in Response to Virus Infection and Altered Innate Immune Signaling. mBio 2010, 1, e00206–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, J.F.; Yin, Q.F.; Chen, T.; et al. Human colorectal cancer-specific CCAT1-L lncRNA regulates long-range chromatin interactions at the MYC locus. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu,Y,; Zhong, J. Innate immunity against hepatitis C virus. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016, 42, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao,R. W,; Wang, Y,; Chen, L.L. Cellular functions of long noncoding RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Smith, L.P.; Lawrie, C.H.; Saunders, N.J.; Watson, M.; Nair, V. Differential expression of microRNAs in Marek’s disease virus-transformed T-lymphoma cell lines. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, K.; et al. A short tandem repeat-enriched RNA assembles a nuclear compartment to control alternative splicing and promote cell survival. Mol. Cell. 2013, 72, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Chu, Q.; Xu, T. The long noncoding RNA NARL regulates immune responses via microRNA-mediated NOD1 downregulation in teleost fish. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100414. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang,S. Y.;Jouanguy, E.; Sancho-Shimizu, V.et al. Human Toll-like receptor-dependent induction of interferons in protective immunity to viruses. Immunol Rev. 2007, 220, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, X. Long noncoding RNAs in innate immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016, 13, 138–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, G.; Feng, S.; Han, K.; Han, L.; Han, L. Role of microRNA and long non-coding RNA in Marek's disease tumorigenesis in chicken. Research in Veterinary Science 2021, 135, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lin, L.; et al. The lncRNA MACC1-AS1 promotes gastric cancer cell metabolic plasticity via AMPK/Lin28 mediated mRNA stability of MACC1. Mol Canc. 2018, 17, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Li, X.; Han, B.; Qu, L.; Liu, C.; Song, J.; Lian, L.; Yang, N. Gga-miR-130b- 3p inhibits MSB1 cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and its downregulation in MD tumor is attributed to hypermethylation. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 24187–24198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Li, X.J.; Teng, M.; Dang, L.; Yu, Z.H.; Chi, J.Q.; Su, J.W.; Zhang, G.P.; Luo, J. In vivo expression patterns of microRNAs of Gallid herpesvirus 2 (GaHV-2) during the virus life cycle and development of Marek’s disease lymphomas. Virus Genes 2015, 50, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B. , Qi, F.; Wu, F.et al. Endogenous retrovirus-derived long noncoding RNA enhances innate immune responses via derepressing RELA expression. mBio.

- Zuckerman, B.; Ulitsky, I. Predictive models of subcellular localization of long RNAs. RNA 2019, 25, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LncRNA | Influenza strain | Mechanism | Subcellular localization | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRAV | A/WSN/1933 (H1N1) | Suppresses the initial transcription of a number of important ISGs, including MxA, IFITM3, OASL, IFIT2, and IFIT3. | Nucleus | Ouyang et al. (2014) |

| TSPOAP1-AS1 | A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1) | OASL, ISG20, IFIT1, IFITM1, and other anti-IAV ISGs are negatively regulated, which suppresses IAV-triggered type I IFN signalling. | Nucleus | WangQet al. (2019) |

| Lnc-Lsm3b | Blocks the overproduction of type Ά IFNs and inhibits RIG-I activation by competing with viral RNAs for the binding of RIG-I monomers. | Cytoplasm | Jiang et al. (2018) | |

| IPAN | A/WSN/1933 (H1N1) | Enhances the stability of the viral PB1 by forming an association that promotes IAV transcription and replication. | Cytoplasm/ Nucleus Cytoplasm/ Nucleus | Wang et al. (2019) |

| LncRNA-PAAN | A/WSN/1933 (H1N1) | Increases viral RNA polymerase activity by facilitating the assembly of the RdRp complex. | Nucleus Nucleus | Wang J et al. (2018) |

| LncRNA-ACOD1 | A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1) | Increases Increases the synthesis of metabolites and the catalytic activity of GOT2. | Cytoplasm Cytoplasm | Wang P et al. (2017) |

| VIN | A/WSN/1933 (H1N1) | Unknown Unknown | Nucleus Nucleus | Winterling et al. (2014) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).