Submitted:

26 October 2024

Posted:

28 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

II. Background & Related Work

A. Challenges in Manual Bug Reporting

B. Automated Bug Reporting: Prior Work

III. The Need for Automation in Bug Reporting

A. Limitations of Manual Bug Reporting

- 1)

- Inconsistency and Human Error: The manual nature of bug reporting can lead to incomplete or ambiguous reports, making it difficult for developers to diagnose and resolve issues promptly.

- 2)

- Lack of Scalability: With the increasing number of test cases in large-scale CI/CD environments, manual reporting struggles to keep pace with the volume of failures, creating bottlenecks.

- 3)

- Time-Consuming Processes: Collecting logs, screenshots, and system data manually for each bug consumes significant time, delaying the overall development cycle and potentially slowing down releases.

- 4)

- Challenges in Reproducibility: Without standardized procedures for capturing bug scenarios, manually reported bugs are often difficult to replicate, resulting in extended debugging times and inefficiencies.

B. Advantages of Automation

- 1)

- Enhanced Consistency and Accuracy: Automation ensures uniformity in bug reports, capturing all necessary details and reducing the likelihood of human error.

- 2)

- Increased Speed: Automated systems can generate bug reports immediately after a failure is detected, shortening the feedback loop between testing and development teams.

- 3)

- Improved Scalability: Automated tools can handle large volumes of test cases and bug reports without fatigue, enabling them to scale seamlessly with growing software systems.

- 4)

- Comprehensive Data Collection: Automation facilitates the gathering of extensive system metrics, logs, and contextual information, providing richer and more actionable bug reports.

C. Impact on the Software Development Lifecycle

- 1)

- Boosted Developer Efficiency: With more accurate and detailed bug reports, developers can address issues more effectively, improving overall productivity.

- 2)

- Reduced Time-to-Resolution: Faster bug report generation and better data collection can decrease the time required to identify and fix bugs, leading to shorter release cycles.

- 3)

- Optimized Tester Resources: By automating the time-consuming task of manual reporting, testers can focus on expanding and refining test cases, enhancing overall software quality.

- 4)

- Strengthened Collaboration: Automation ensures a seamless flow of information between testers and developers, fostering better communication and a more responsive development approach.

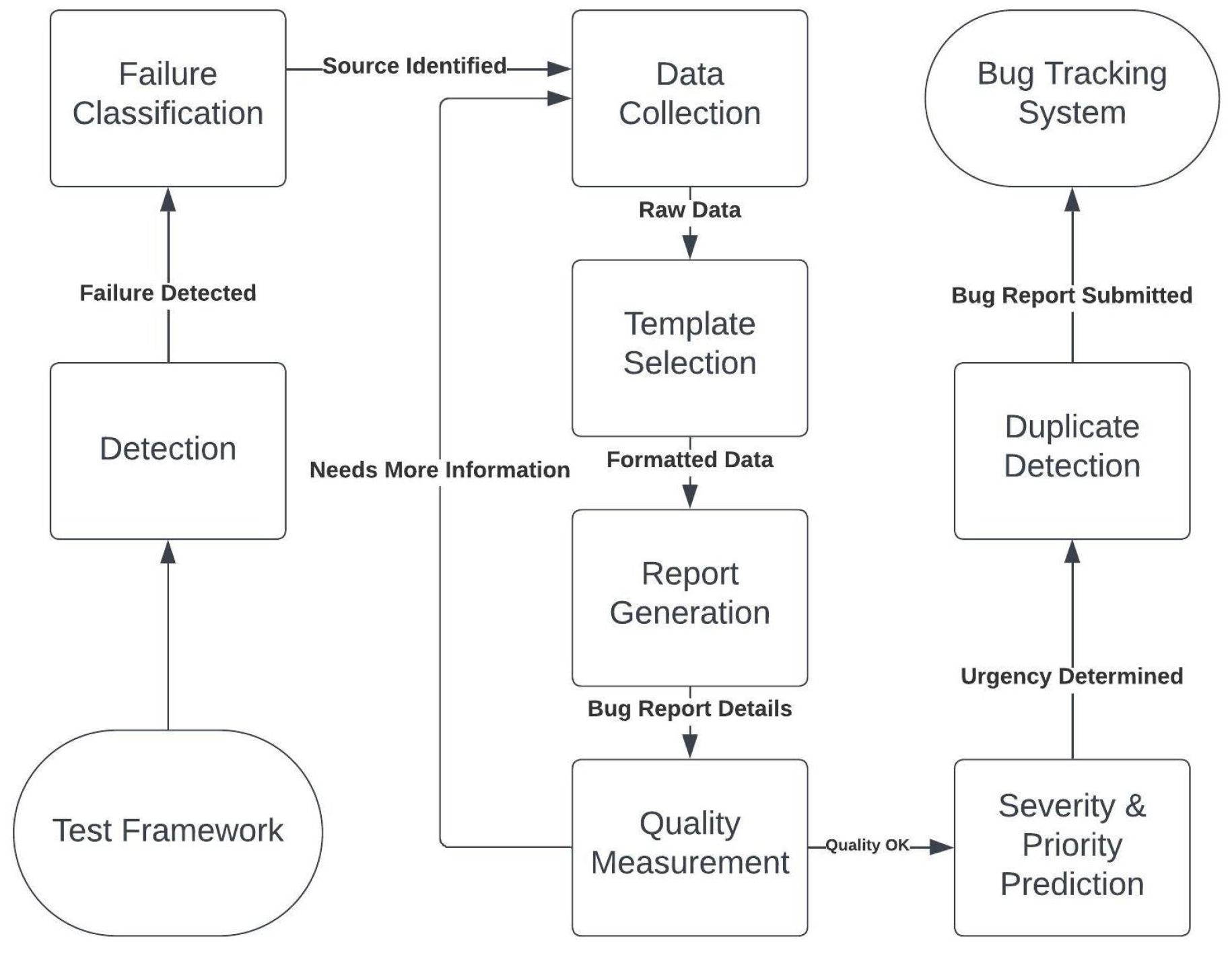

IV. Proposed Tool Architecture

A. Test Failure Detection

1. Techniques and Strategies for Identifying Test Failures

- Assertion Checks: The tool is integrated with testing frameworks to monitor and detect assertion failures as they occur. These failures typically indicate that the software has not met the expected behavior.

- Pattern Recognition: By using machine learning models, the tool can detect patterns indicative of test failures. Over time, these models can be refined to capture subtle issues that may not be detected by traditional checks[10].

- Threshold Detection: The tool can be configured to trigger failure alerts when system performance metrics, such as response time or memory usage, exceed predefined thresholds. This approach enables the detection of performance-related issues that may not manifest as explicit assertion failures[11].

2. Triggers for the Subsequent Reporting Process

- Immediate Triggering: In smaller environments or when handling critical failures, the tool immediately initiates the bug reporting process after detecting a failure. This ensures that urgent issues are reported without delay.

- Batch Processing: or large-scale testing environments, the tool can accumulate multiple failures and process them together. This method is particularly beneficial in large system tests, where processing failures in batches improves efficiency and reduces system overhead.

B. Failure Classification

1. Techniques and Strategies for Failure Classification

- Machine Learning Models: Supervised learning models trained on historical data are used to predict the category of new test failures [12]. These models improve over time as they are exposed to more data, resulting in more accurate classifications.

- Rule-Based Systems: A predefined rule set classifies failures based on specific patterns in error messages or logs. This approach is particularly effective for handling common, well-understood failure types.

- Integration with Testing Frameworks: Many testing frameworks have built-in classification mechanisms, which the tool leverages to provide initial classification insights [13].

- Feedback Loop: Engineers and testers can provide feedback on the tool’s classification decisions. This feedback loop allows the system to continuously improve its classification accuracy over time.

2. Handling Ambiguities and Overlaps

- Confidence Scores: The system assigns confidence scores to classifications. If the score is below a certain threshold, the failure is flagged for manual review to ensure accurate classification.

- Fallback Classifications: When a failure cannot be confidently classified, it is assigned to a general "Miscellaneous" or "Requires Review" category. This prevents unclassified failures from being overlooked.

- Cross-Verification: The system uses multiple classification methods in parallel. If the results of these methods differ, the failure is flagged for manual inspection.

- Continuous Learning: The classification system is periodically retrained on new data to ensure it adapts to evolving software systems and new types of failures[14].

C. Gathering Test Failure Data

1. Techniques and Strategies for Data Collection

- Log Scraper: An automatic scraper collects logs generated immediately before and after the failure. These logs often provide key insights into the sequence of events leading up to the failure.

- System State Snapshots: Capturing the system’s state at the moment of failure is crucial for understanding performance issues or anomalies. This includes metrics like CPU usage, memory consumption, and network performance.

- Integration with Testing Tools: The tool taps into the capabilities of existing testing frameworks, using their built-in plugins to collect detailed and relevant data. This integration ensures that the data collection process is thorough without requiring additional system resources.

2. Handling Varied Data Types

- Dynamic Storage Allocation: The system dynamically allocates storage based on the type of data being collected, ensuring efficient use of resources.

- Data Tagging: Collected data is tagged with metadata to make it easier to categorize and retrieve during the bug report generation phase. This ensures that reports are concise yet informative.

D. Bug Report Template Selection

1. Techniques and Strategies for Template Selection

- Classification-Driven Selection: The template is selected based on the classification of the failure. For example, a UI bug may require a different template than a performance issue [15].

- Severity-Based Templates: High-severity defects are reported using more detailed templates, while lower-severity issues may use simplified versions.

- Contextual Templates: The tool can select templates that are tailored to the context of the defect, such as load testing or UI testing scenarios.

2. Customization and Adaptability

- Dynamic Field Inclusion: Depending on the type of failure, the tool can dynamically include or exclude certain fields from the report.

- User-Defined Templates: Test engineers can modify existing templates or create new ones to fit their specific needs.

- Integration with Bug Tracking Systems: The chosen template is compatible with the bug tracking system being used, ensuring seamless submission.

E. Report Generation

1. Techniques and Strategies for Report Generation

- Data Synthesis: The tool compiles and synthesizes all the data collected during the failure detection and data gathering phases. It ensures that the report is thorough, including key metrics, logs, screenshots, and any relevant system state information.

- Template Application: The selected bug report template is applied to the synthesized data, ensuring that the report follows a standardized format. This allows for consistency across different types of bug reports.

- Visual Enhancements: Screenshots, graphs, or other visual aids are incorporated into the report where appropriate, providing a clearer picture of the defect. These visuals help developers quickly understand the issue without needing to analyze raw data.

- Auto-Population: Certain fields in the report can be automatically populated based on known data from past reports or default values. This speeds up the report generation process and ensures that no crucial fields are left empty [16].

2. Finalizing and Export Options

- Report Preview: The tool offers a preview option, allowing users to review the report before submission. This ensures that all necessary information is included and the report is readable.

- Export Formats: The tool supports multiple export formats (e.g., JSON, XML, YAML) to accommodate the requirements of different bug tracking systems. This flexibility ensures that the report can be seamlessly integrated into the existing workflow of any development team.

- Integration Push: For systems that are fully integrated with bug tracking platforms, the tool can automatically submit the bug report to the relevant tracking system, reducing manual submission steps.

F. Bug Report Quality Measurement

1. Techniques and Strategies for Quality Measurement

- Completeness Checker: The tool automatically checks if all essential fields in the bug report are filled out. If any critical information is missing, the user is prompted to provide the necessary details.

- Relevance Analysis: Using natural language processing (NLP) algorithms, the tool analyzes the content of the bug report to ensure that it is relevant to the identified defect. This prevents the submission of incomplete or irrelevant reports.

- Clarity Assessment: The tool incorporates readability metrics to evaluate whether the report is clear and comprehensible for developers. This reduces confusion and the need for follow-up clarification[17].

- Historical Data Comparison: New reports are compared with historical data to ensure that they are not redundant or inconsistent with past bug reports.

2. Feedback Loop for Quality Enhancement

- Developer Feedback: Developers can provide feedback on the quality and usefulness of the bug reports. This feedback is used to refine the report generation process, ensuring that future reports are more aligned with developer needs.

- Historical Analysis: The tool analyzes historical bug reports to identify common issues in past reports and adjusts the report generation process accordingly.

- Iterative Refinement: Based on the feedback received from developers and historical analysis, the tool iteratively refines the report generation process to produce higher-quality reports over time.

G. Severity and Priority Prediction

1. Techniques and Strategies for Severity and Priority Prediction

- Historical Data Analysis: The tool analyzes previously reported bugs and uses the patterns found in those reports to predict the severity and priority of new bugs.

- Natural Language Processing (NLP): By analyzing the textual descriptions and other fields in the bug report, the tool can predict the severity and priority of the issue based on its impact on the system or users [18].

- Dependency Mapping: The tool maps the bug to its dependencies within the system and assesses its impact on other modules, helping determine its severity. Bugs affecting critical components of the system are given higher priority.

- Real-Time System Impact Analysis: The tool assesses the immediate impact of the bug on live systems or users, further refining the priority prediction for prompt response to high-impact bugs.

- Assigning appropriate severity and priority to a bug is crucial for efficient defect management. Automating this process ensures that critical issues are addressed promptly, while less urgent defects are scheduled appropriately.

2. Feedback and Correction Mechanisms

- Prediction Confidence Thresholds: If the confidence level of the tool’s prediction falls below a certain threshold, it triggers a manual review to avoid misclassification.

- User Overrides: Developers or QA engineers can manually adjust the predicted severity and priority of the bug if the tool’s predictions do not align with their assessment.

- Model Retraining: As more bugs are reported and manually adjusted, the tool continually retrains its prediction models, improving its accuracy over time.

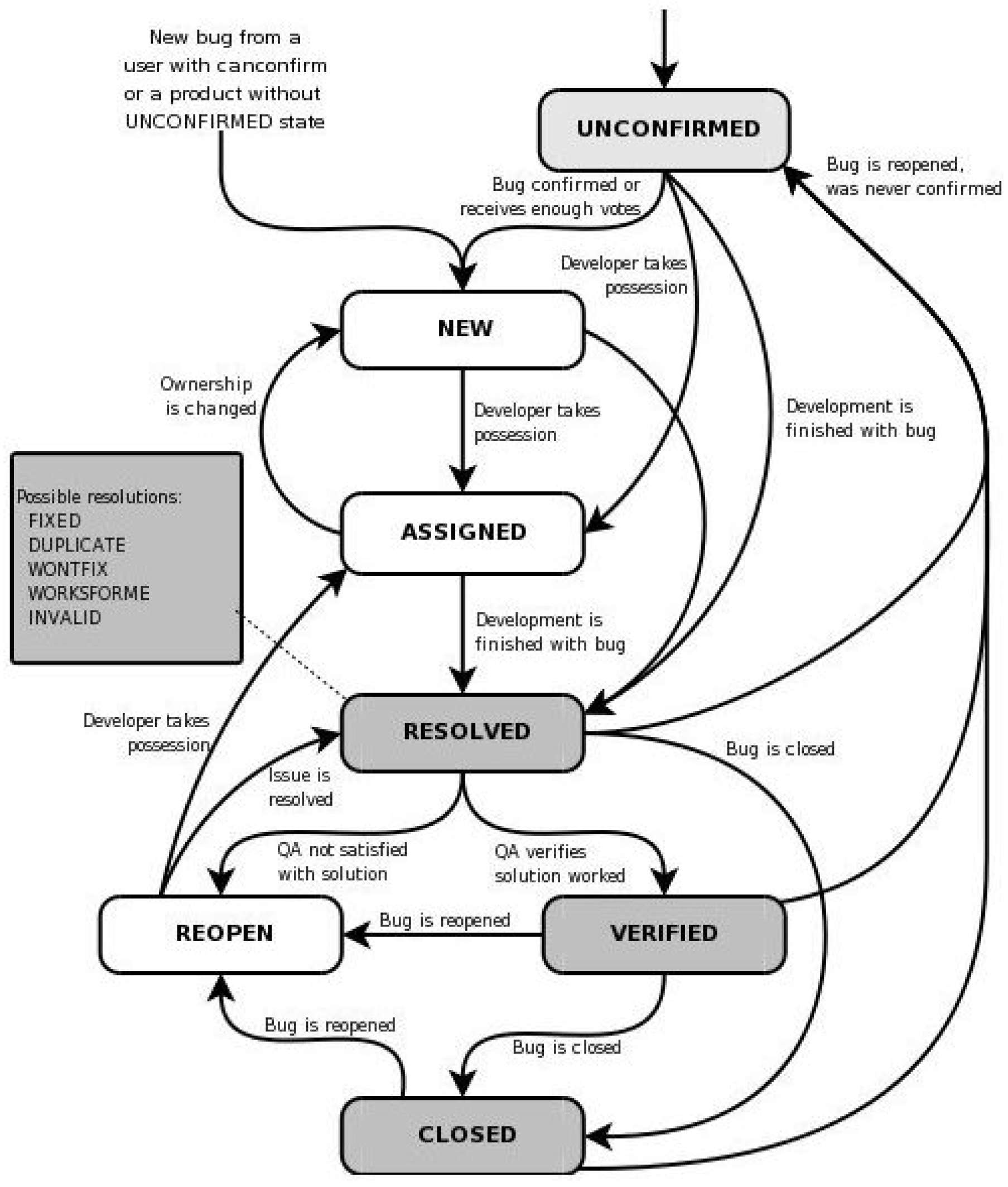

H. Duplicate Bug Detection

1. Techniques and Strategies for Duplicate Bug Detection

- Textual Similarity Algorithms: The tool compares new bug descriptions with existing entries using algorithms such as cosine similarity and text embeddings. This method helps detect textual overlap between reports, identifying potential duplicates[19].

- Issue Metadata Comparison: The tool cross-references key attributes like module name, reported version, and affected system components to identify similarities between bug reports and detect duplicates.

- Machine Learning Approaches: Classifiers trained on previously identified duplicate pairs help the tool forecast potential duplicates for new bug entries, improving detection accuracy.

- Cluster Analysis: The tool groups similar bugs based on specific attributes, then checks for duplicates within those clusters, increasing detection precision[20].

2. Integration with Existing Bug Databases

- API Utilization: By integrating with the bug tracking system’s API, the tool can fetch real-time data on existing bug reports, allowing it to detect duplicates as new reports are submitted.

- Incremental Data Fetching: To reduce system overhead, the tool performs incremental checks rather than scanning the entire bug database every time, ensuring efficiency.

V. Conclusion

A. Limitations and Future Work

References

- N. Bettenburg, S. Just, A. Schrooter, C. Weiss, R. Premraj, and T. Zimmermann, “What makes a good bug report?” in Proceedings of the 16th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering, 2008, pp. 308–318. [CrossRef]

- W. Zou, D. Lo, Z. Chen, X. Xia, Y. Feng, and B. Xu, “How practitioners perceive automated bug report management techniques,” IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, vol. 46, no. 8, pp. 836–862, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, M. Yan, W. Sun, X. Liu, and Y. Wu, “A first look at bug report templates on github,” Journal of Systems and Software, vol. 202, p. 111709, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Zeller, “Yesterday, my program worked. today, it does not. why?” ACM SIGSOFT Software Engineering Notes, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 253–267, 1999. [CrossRef]

- T. Menzies and A. Marcus, “Automated severity assessment of software defect reports,” in IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance, Beijing, China, 2008. [CrossRef]

- N. Jalbert and W. Weimer, “Automated duplicate detection for bug tracking systems,” in IEEE International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN), Anchorage, AK, USA, 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. Patil and A. Jadon, “Auto-labelling of bug report using natural language processing,” in IEEE 8th International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT), 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Rastkar, G. C. Murphy, and G. Murray, “Automatic summarization of bug reports,” IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, vol. 40, no. 4, pp. 366–380, 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Qamar, E. Sülün, and E. Tüzün, “Taxonomy of bug tracking process smells: Perceptions of practitioners and an empirical analysis,” Information and Software Technology, vol. 150, p. 106972, 06 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Chigurupati, R. Thibaux, and N. Lassar, “Predicting hardware failure using machine learning,” in 2016 Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS), 2016, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- C. Landin, J. Liu, and S. Tahvili, “A dynamic threshold-based approach for detecting the test limits,” in ICSEA 2021, 2021, p. 81.

- J. Kahles, J. Törrönen, T. Huuhtanen, and A. Jung, “Automating root cause analysis via machine learning in agile software testing environments,” in 2019 12th IEEE Conference on Software Testing, Validation and Verification (ICST), 2019, pp. 379–390. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Jones and M. J. Harrold, “Empirical evaluation of the tarantula automatic fault-localization technique,” in Proceedings of the 20th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering, 2005, pp. 273–282. [CrossRef]

- S. Jadon and A. Jadon, “An overview of deep learning architectures in few-shot learning domain,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2008.06365, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Song and O. Chaparro, “Bee: A tool for structuring and analyzing bug reports,” in Proceedings of the 28th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, 2020, pp. 1551–1555. [CrossRef]

- T. Brown et al., “Language models are few-shot learners,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, 2020, pp. 1877–1901.

- A. Jadon and A. Patil, “A comprehensive survey of evaluation techniques for recommendation systems,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.16015, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Lamkanfi, S. Demeyer, E. Giger, and B. Goethals, “Predicting the severity of a reported bug,” in 2010 7th IEEE Working Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR 2010), 2010, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- A. Patil, K. Han, and A. Jadon, “A comparative analysis of text embedding models for bug report semantic similarity,” in 2024 11th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN). IEEE, 2024, pp. 262–267. [CrossRef]

- A. Deshmukh and F. Shull, “Clustering techniques for improved duplicate bug report detection,” Empirical Software Engineering, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 458–479, 2020.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).