1. Introduction

ITS is the product of the combination of artificial intelligence and computer-aided instruction, aiming to introduce artificial intelligence, multimedia and network technology into traditional teaching system to improve teaching efficiency and quality. It generates a large amount of learning behavior data all the time, and builds a number of intelligent learning services, including cognitive diagnosis, knowledge tracking, resource recommendation services, based on learners' historical interactive data, to help learners improve learning efficiency. The rapid development of information technology has facilitated the growing popularity of online education, making massive open online courses increasingly popular. Various course platforms are developing rapidly, including Coursera, edX, Udacity, iCourse, and XuetangX, among others. These platforms offer a wide range of courses covering various fields of study. For example, XuetangX states in its introduction that its platform offers over 5,000 high-quality courses across 13 disciplines. However, on such a large-scale course platform, learners often find it challenging to discover courses and resources that correspond to their interests and preferences. Therefore, course recommendation serves as a bridge between learners and course resources. More specifically, course recommendation is a crucial component of online course platforms, which filter the vast amount of course data by recording and analyzing learners' historical learning behavior data, thereby providing learners with courses that align with their interests and preferences.

Compared to recommendations in fields such as e-commerce, social media, and news, course learning demands a considerable investment of time and effort, resulting in sparser interactions between learners and courses. Data sparsity and the cold start problem are critical factors that limit recommendation effectiveness. Given that interactions in course recommendations are even sparser, ensuring effective recommendations becomes more challenging. Providing a personalized learning experience for learners in the context of data sparsity poses a significant challenge.

More specifically, online course recommendation can be described as the system's task of recommending candidate courses that align with learners' interests based on their historical learning activity data, including course information and feedback data from the learning process. Collaborative filtering-based course recommendation has received widespread attention, primarily utilizing the similarity between students [

1] or courses [

2] to recommend relevant courses. These methods are straightforward to implement and offer strong interpretability; however, their efficacy in tackling data sparsity and the cold start issue still needs improvement. With the advancement of deep learning technologies, the integration of modern recommendation systems with deep learning has provided strong momentum for the development of the recommendation field, such as NCF [

3], NFM [

4], leading to a series of methods developed specifically for course recommendation. For example, Hidasi et al. [

5] framed course recommendation as a session-based recommendation task, solving it through a recurrent neural network by gradually feeding courses from the time series into a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) to gather course information from the historical sequence. The final embedding vector was then treated as the user's interest. Subsequently, recommendation systems such as DIEN [

6] ,MAAMF [

7] and DRN [

8] introduced attention mechanisms, reinforcement learning. However, despite the significant contributions of deep learning technologies to enhancing recommendation effectiveness in fields like e-commerce, they have not adequately addressed the intrinsic relationships between courses, limiting their potential for further performance improvement. The utilization of knowledge graphs as supplementary information, combined with classic models such as collaborative filtering [

9], has been shown to effectively integrate multi-source heterogeneous data [

10], leading to a deeper understanding of learners' preference information and demonstrating good recommendation effectiveness [

11,

12]. However, there are still two unresolved challenges in the field of course recommendation: (1) Current research neglects the sequential relationship between the course learners learn. (2) It does not take advantage of the differences in learners' interest in different courses during the knowledge dissemination process.

To tackle the aforementioned issues, we propose an innovative solution called PGDB, specifically designed for course recommendation systems. The method first generates an initial set of course seed collections through the diffusion mechanism of the knowledge graph, and recursively collects multiple knowledge triples related to learners to construct their knowledge background. Next, we employ a relation-aware multi-head attention network to analyze learners' preferences for courses and their relational paths, aiming to accurately distinguish the semantic diversity in different contexts and thereby gain a more comprehensive understanding of learners' needs. Building on this, the temporal preference modeling module uses a BiLSTM to deeply explore the evolution patterns of learners' interests, generating personalized representations relevant to the learners. These representations not only take into account learners' historical preferences but also reflect the dynamics of their interests over time. Finally, the prediction module combines the final representations of learners and courses to output the probabilities of learners selecting candidate courses. Experimental results on real datasets show that the PGDB model greatly outperforms the latest baseline models in recommendation effectiveness, validating the effectiveness and practicality of our approach.

Our contributions include:

This paper presents an innovative end-to-end knowledge-aware hybrid model for course recommendation. The model multiplies head entities with relational paths, then applies a multi-head attention mechanism, followed by multiplication with the tail entities of the current hop after the softmax function. Finally, it concatenates the representations from each hop, enhancing the representation learning capability of both learners and courses;

At the same time, the model fully leverages the advantages of graph neural networks and bi-directional long short-term memory networks, cleverly integrating the two to achieve a fusion of graph networks and temporal networks. This approach better captures the long-term dependencies in graph-structured data, resulting in a more suitable recommendation model;

We utilize the MOOCCube dataset from XuetangX, one of China's largest online course platforms to validate the effectiveness of the proposed model. Experimental results show that our model greatly exceeds the performance of the current state-of-the-art baselines.

In the rest of this article, the work is reviewed in

Section 2. In

Section 3 and

Section 4, we formally define the research question and describe our proposed PGDB approach. In

Section 5, we have carried out a large number of experiments and analyzed the experimental results. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes this paper, and puts forward conclusions and future research directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Course Recommendations

With the rapid development of large-scale online courses, course recommendation has garnered considerable interest in both academia and industry. Generally, course recommendation methods can be categorized into content-based course recommendation, collaborative filtering-based course recommendation, and hybrid approaches. Content-based course recommendation utilizes the characteristics of the courses themselves for recommendations. Apaza et al. [

13] proposed a course recommendation system based on historical performance, using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) to model course content, thereby intelligently recommending online courses to students. Collaborative filtering methods use learners with similar interests or course characteristics as a basis for recommendations. Li et al. [

14] proposed a Bayesian Personalized Ranking Network for course recommendation, which integrates item-based collaborative filtering with Bayesian networks to model learners' preferences based on their historical registered courses in pairs. Xu and Zhou [

15] designed a model that utilizes deep learning to derive multimodal course features, which are then input into a long short-term memory (LSTM) network to infer learners' interest preferences using both explicit and implicit feedback information. Tian et al. [

16] exploratively integrated Multidimensional Item Response Theory (MIRT) into the recommendation model, dynamically updating learners' abilities using an ability tracking model, and cleverly combining learners' ability diagnosis with collaborative filtering-based course recommendation to enhance the effectiveness and interpretability of course recommendations.

To meet the growing personalized learning needs of learners, hybrid course recommendation methods have become a primary research strategy for addressing current challenges. Researchers are leveraging external knowledge to further enhance recommendation effectiveness, with particular attention given to graph-structured data. Zhu et al. [

17] proposed an offline hybrid course recommendation model that utilizes multi-source heterogeneous data to describe students, courses, and other entities. By employing a random walk-based neural network, the model generates vector representations for students based on relevant data, and finally uses tensor decomposition to learn and predict students' ratings for courses they have not yet taken. Yang and Cai [

18] proposed an end-to-end framework that uses knowledge graphs as an auxiliary information source for collaborative filtering, aiming to enhance the semantic representation of items through knowledge graphs. This framework combines deep matrix factorization models with an improved loss function, applying it to course recommendation. For example, Wang et al. [

19] proposed a hyper-edge-based graph neural network (HGNN) for recommending MOOC courses. Zhang et al. [

20] introduced an efficient course recommendation model called the Knowledge Grouping Aggregation Network (KGAN), which automatically iterates through the course graph to assess learners' latent interests. Additionally, Deng et al. [

21] developed a new online course recommendation method that combines knowledge graphs and deep learning, modeling course information through a course knowledge graph and representing courses using TransD.

However, these existing methods still need improvement in capturing the sequential relationships between the courses learned by learners, and they have not effectively delved into learners' interest preferences during the process of knowledge dissemination. In this paper, we propose a course recommendation method that integrates knowledge graphs and long short-term memory networks, while also emphasizing the importance of knowledge during the dissemination process. This approach better uncovers the relationships between courses and focuses on the transmission of important knowledge, helping to enhance the accuracy of course recommendations.

2.2. Recommendation Method Based on Knowledge Graph

The integration of knowledge graphs with recommendation systems has led to a series of research achievements. Based on different methods of integrating knowledge graphs, we can categorize knowledge-aware recommendation methods into three main types: embedding-based methods, path-based methods, and graph neural network-based methods.

2.2.1. Embedded-Based Methods

Embedding-based methods not only possess task independence but also allow for the flexible integration of knowledge graphs into various recommendation models. These methods primarily train item embeddings by using knowledge graphs as constraints and leverage matrix factorization to achieve click-through rate prediction. For instance, CKE [

9] learns item embeddings participating in the knowledge graph through TransR [

22]. DKN [

23] treats entity embeddings and word embeddings as distinct input channels and utilizes TransD [

24] to generate news embeddings for recommendation based on the knowledge graph. However, the knowledge graph embedding methods (KGE) employed in these models are more suitable for in-graph applications rather than recommendation tasks, resulting in subpar performance of the learned entity embeddings in item recommendation.

2.2.2. Path-Based Methods

Path-based methods infer the relevance between entities using sequences of entities and relationships, based on which recommendation is made. However, compared to embedding-based methods, path-based strategies exhibit task dependence and necessitate domain knowledge to extract paths, which may lead to missing important information paths or introducing irrelevant trivial paths. In the context of course recommendation, constructing meta-paths is significantly simplified. However, as knowledge expands and learning patterns change rapidly, the emergence of new patterns necessitates the reconstruction of meta-paths, which undoubtedly incurs additional overhead. An alternative is to use path selection algorithms to identify important paths, but balancing the optimization of path selection with recommendation objectives remains a significant challenge in practical applications [

25,

26].

2.2.3. Graph Neural Network-Based Methods

Combining multi-hop neighborhood information to represent nodes and graph structures in graph neural networks is a highly effective approach. RippleNet [

27] is an end-to-end framework that seamlessly integrates knowledge graphs into recommendation systems. It simulates the propagation of ripples on a water surface, automatically expanding users' latent interests along the links of the knowledge graph, thereby facilitating the dissemination of user preferences. Multiple "ripples" activated by historical clicks are combined to form a preference distribution for candidate items, which is then used to predict click probabilities.

KGCN [

28] iteratively aggregates neighboring information from nodes through graph convolutional neural networks to generate item representations. Subsequently, the user-item interaction graph is combined with the knowledge graph to form a Unified Knowledge Graph (UKG), which recursively propagates embeddings from neighboring items using an attention mechanism, effectively allocating weights to differentiate the contributions of each neighbor [

29]. Additionally, motivated by the effectiveness of contrastive learning in extracting supervisory signals from data, KGIC focuses on applying contrastive learning in Knowledge Graph Recommendation (KGR), proposing a novel multi-level interactive contrastive learning mechanism that achieves significant recommendation performance [

30].

Recently, Wang et al. proposed a framework called KFGAN, which is based on a knowledge-aware fine-grained attention network aimed at achieving personalized knowledge-aware recommendations. This framework encodes relational paths and relevant entities to capture user preferences and generates detailed knowledge graphs, thereby learning latent semantic information [

31].

However, most current graph neural network-based methods still have room for improvement in capturing the sequential relationships between courses taken by learners, and they have not effectively delved into learners' interest preferences during the knowledge dissemination process. In this paper, we propose a course recommendation method that combines knowledge graphs and long short-term memory networks, focusing on the importance of knowledge during the dissemination process. This method can more effectively uncover the relationships between courses, emphasizing the transmission of important knowledge, thereby helping to enhance the accuracy of course recommendations.

3. Problem Definition

In this section, we briefly introduce the key structural components required for our approach, including the learner-course interaction graph and the course knowledge graph. Following this, we provide a formal statement of the course recommendation problem.

Learner-Course Interaction Graph: In a typical course recommendation scenario, we use

to represent the set of M learners, and

to represent the set of N courses. The interaction between learners and courses is denoted by the matrix

, where learner-course interactions, based on implicit feedback, can be expressed as follows:

When a learner has interacted with a course (e.g., by clicking, browsing, etc.), we set

to indicate that the learner has a behavioral preference for that course. Conversely, if no interaction has occurred,

. It is important to note that

does not necessarily imply that the learner dislikes the course. It could also be due to the vast number of available courses, where the learner has not yet encountered the course, and thus no interaction has taken place.

Course Knowledge Graph: Knowledge graphs store rich factual information in a graph structure, which essentially forms a semantic network of relationships between learners and courses, interweaving complex relationships among learners, courses, and other entities. These relationships can be formalized in the form of triples, i.e., (head entity, relationship, tail entity). Thus, a heterogeneous knowledge graph can be represented as , wheredenotes the existence of a relationship between the head entity and the tail entity , and and represent the sets of entities and relations, respectively. For example, a course recommendation triple (Data Structures, School, Tsinghua University) indicates that Tsinghua University offers a course on data structures. However, there may be cases where different universities offer courses with the same name, such as (Data Structures, School, South China University of Technology), which can cause confusion about the entities associated with the course. Therefore, to effectively align a course with an entity in the knowledge graph, we adopt the set , which helps account for cases where different schools offer courses with the same name, ensuring accuracy and clarity in the correspondence.

Recommendation Task: Given the learner-course interaction matrix and the course knowledge graph , the goal of the recommendation task is to predict the probability that a learner will next click on a course that they have not interacted with. Specifically, we aim to learn a prediction function, where denotes the predicted probability and represents the model parameters of the function .

4. Method

4.1. Symbol Summary

Table 1 presents the basic symbol representations used in this chapter, where the bold symbols with subscripts also have corresponding meanings. The remaining symbols are generated through operations or propagation between these basic symbols.

4.2. Model

Inspired by the graph neural network-based methods model, we treat the courses that a learner has interacted with in the past as starting points, and then iteratively expand through the connections in the knowledge graph. This process progressively uncovers the learner’s latent interest preferences, aiming to predict the preference distribution over candidate courses and subsequently estimate the final click probability. In this section, we will provide a detailed explanation of the proposed model and introduce the primary contributions of this paper.

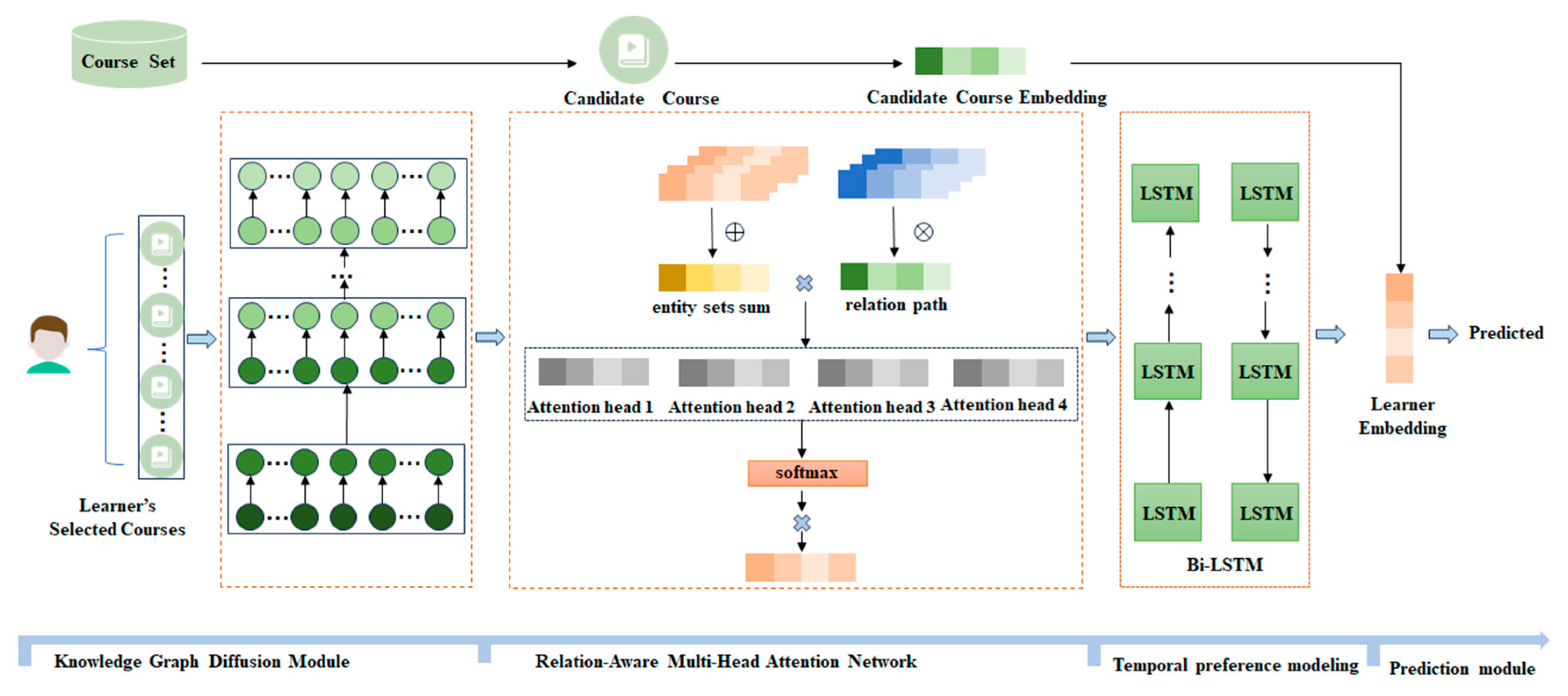

Figure 1 illustrates the workflow of PGDB, which consists of four key components:(1) Knowledge Graph Diffusion Module. This module is primarily responsible for propagating the initial course seed set within the knowledge graph, recursively obtaining the set of h-hop related knowledge triples for learner

.(2) Relation-Aware Multi-Head Attention Network. This component employs a novel knowledge-aware multi-head attention mechanism that analyzes the learner’s preferences for both courses and relational paths. It generates attention weights assigned to the tail entities, capturing the semantic diversity across different contexts. (3) Temporal Preference Modeling. This module concatenates the representations of tail entities across different hop distances, generating a collection of tail entities for different temporal states. A bi-directional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) network is used to capture the evolution of the learner’s interests over time, producing temporally dependent learner representations. (4) Prediction Module. his module leverages the final representations of both the learner and the courses to output the probability that the learner will select a candidate course.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the PGDB model, which makes up of four modules: knowledge graph diffusion module, relation-aware multi-head attention network, temporal preference modeling and prediction module.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the PGDB model, which makes up of four modules: knowledge graph diffusion module, relation-aware multi-head attention network, temporal preference modeling and prediction module.

4.2.1. Knowledge Graph Diffusion Module

The primary goal of the knowledge graph diffusion module is to capture high-order collaborative signals between learners and courses by propagating course entities that the learners have interacted with across the graph. This allows for a more precise depiction of the learner’s latent preferences. The learner’s preferences are partially reflected in the interaction data with courses, and propagating through the paths in the knowledge graph not only reveals intrinsic connections between courses but also further enhances the feature representation of the learner. This module consists of two main parts: first, extracting course entities that learners have interacted with from the interaction graph; and second, performing an iterative propagation process of the course entities within the knowledge graph. Below, we will introduce these two components in detail.

First, the interaction graph clearly presents the interactions between learners and courses in the form of a bipartite graph. Compared to traditional methods that use independent latent vectors to represent learner features, extracting learner representations from the interaction graph can more accurately reflect their interest preferences. Given the interaction matrix between learners and courses, we can extract the courses that the learner has directly interacted with and obtain the learner’s initial seed set through entity alignment.

Second, we continuously expand the seed set outward along the paths of the knowledge graph in deeper layers, exploring the connectivity between nodes in the graph. This propagation of information enriches the feature representations of both the learner and the courses. Therefore, the set of h-hop relevant entities for learner

is defined as:

Here,

represents the hyperparameter for the maximum number of hops in the propagation, and

denotes the current hop number in the propagation. Given the entity set

, the

ripple set for learner

can be obtained as follows:

4.2.2. Relation-Aware Multi-Head Attention Network

Entities in the knowledge graph are connected through relationships. Taking a course from the initial course set as an example, different relational paths can link to various entities, which can enrich the representation of the course and, in turn, reflect the learner's preferences. For instance, using the course "C++ Programming Basics" as the initial course, a two-hop propagation in the knowledge graph reveals that this course is offered by Tsinghua University, which also provides the course "C++ Programming Advanced." In this path, there are two relationships: "offers" and "includes." In another path, the course "C++ Programming Basics" belongs to the Computer Science subject, which also includes the "Java Programming" course. Here, the two-hop relationship is "subject" and "includes." Thus, it is evident that the final recommendation results are influenced by both the head entity and the relational paths. Consequently, it can be observed that project-entity pairs may exhibit different similarities when measured through different relationships. Drawing on existing knowledge-aware preference propagation mechanisms, we propose a relation-aware multi-head attention network that assigns different attention weights to the tail entities, accurately capturing their significance and better reflecting learner preferences.

Given the tuple set

at the

layer, we use

to represent the relational paths propagated to the (h-1)-th layer and

to denote the entity set connected on the relation path

, as denoted below:

Here,

denotes the embedding of the head entity, while

represents the embedding of the current relationship. Additionally, we construct the attention weight

for the tail entity embedding:

Here,

denotes the embedding of the current tail entity (a given candidate course entity in the knowledge graph), and

represents the attention of the head entity towards the tail entity in the relational space, which can be expressed as:

Here,

denotes the operation of the multi-head attention mechanism, which captures diverse features and relationships among the input information by simultaneously focusing on different parts. This approach also mitigates the impact of noise during the propagation process, generating a tail entity embedding representation that integrates information from various contexts.

and

represent the trainable weights and biases. In the following, we employ the softmax function to normalize the coefficients across the entire set of triples, which can be formulated as follows:

Here, denotes the ripple set for learner at the h-th layer.

Ultimately, we concatenate all the extracted knowledge from the hops to form a sequential ripple set, which is defined as follows:

Here,

represents the ripple set representation obtained at each hop, which is specifically expressed by the following formula:

4.2.3. Temporal Preference Modeling

As the ripple set continuously expands outward, there is a possibility of information loss. Each layer of expansion can be viewed as a temporal relationship in the sequence, which aligns with the characteristics of BiLSTM. Therefore, utilizing BiLSTM to consider temporal relationships allows for further updating and refining the learner's feature representation. The Bi-LSTM component is a bidirectional LSTM neural network developed from LSTM, with the specific computation process outlined as follows:

Here,

and

denote the weight matrices,

represents the bias, and

is the sigmoid activation function.

indicates the hidden state representation at the current time step. In this manner, Bi-LSTM network is capable of retaining contextual information through the LSTM units. For the t-th time step, two parallel LSTM layers process the input vector from their respective opposite directions, and then output the sum of the hidden state vectors, which can be described as:

Here,

,

represent the output results from two parallel LSTM layers operating in the forward and reverse directions, respectively.

,

represent the weight parameters for the two parallel LSTM layers that function in the forward and backward directions, respectively, while

denotes the bias term. We store the output at each time step to obtain the final output representation from the Bi-LSTM, denoted as

. Consequently, the learner's final embedding representation can be formally expressed as:

where

denotes the sigmoid activation function.

4.2.4. Prediction Module

We use

and

to denote the feature vector representations of the learner and the course, respectively. Ultimately, we obtain the predicted probability of a learner clicking on a course using the inner product:

4.2.5. Loss Function

We present the following loss function to assist the model in better learning the representation of learner preferences. The loss function for the PGDB model is divided into three components.

First, to facilitate better learning during optimization, we use cross-entropy loss to measure the difference between the predicted probabilities and the true labels:

where

denotes the cross-entropy loss,

,

represent the positive and negative samples of the learner-course pairs, respectively.

Second, we employ a fully connected neural network as the Knowledge Graph Embedding (KGE) loss, which can be expressed as follows:

To alleviate the impact of overfitting and noise in the knowledge graph, we optimize the loss function by incorporating a regularization term, formulated as follows:

Finally, the joint learning objective function is given by:

5. Experiments

5.1. Dataset

In this study, we utilize the MOOCCube dataset as our evaluation dataset. This is shown in

Table 2. MOOCCube [

32] is an open data repository designed for researchers in the fields of large-scale online education, knowledge graphs, and data mining. It encompasses online courses, instructional videos, knowledge concepts, learner course selection information, and video viewing records, as well as a concept graph constructed based on the hierarchical and sequential relationships among knowledge concepts. We randomly selected a three-month subset of behavioral data from January 1, 2018, to April 1, 2018, while preserving the original order of course selections. We adhere to the configurations established in KGAN and KG to validate the applicability of our model to other educational recommendation tasks that exhibit a similar data organizational structure to the course dataset.

5.2. Baselines

To assess our proposed method, we compare it with the following baseline models:

LR [

33]: Linear Regression has been widely employed in classification tasks, playing a significant role in industrial Click-Through Rate (CTR) prediction. This approach utilizes a weighted sum of relevant features as the input to the model.

BPR [

34]: Bayesian Personalized Ranking (BPR) is a traditional collaborative filtering technique that leverages Bayesian methods to optimize the pairwise ranking loss function in recommendation tasks.

FM [

35]: Factorization Machines (FM) are principled models that can account for interactions between features and conveniently integrate any heuristic features. In our experiments, we utilized all available information except for the secondary subjects.

DKN [

23]: The Deep Knowledge-Aware Network introduces knowledge graph representations into recommendations to predict click-through rates. The core of DKN is a multi-channel knowledge-aware convolutional neural network that integrates semantic and knowledge representations while maintaining the alignment between words and entities. In this study, course titles are treated as the textual input for DKN.

RippleNet [

27]: This is an end-to-end framework that inherently integrates knowledge graphs into recommendation systems. It simulates the propagation of ripples on water surfaces to automatically expand users' possible interests along the links of the knowledge graph, thereby facilitating the diffusion of user preferences. Multiple "ripples" activated by historical clicks accumulate to form a preference distribution for candidate items, which is then utilized to predict click probabilities.

KGNN-LS [

36]: This approach proposes a Knowledge-Aware Graph Neural Network with Label Smoothing Regularization, which computes user-specific item embeddings through a trainable function, transforms the knowledge graph into a weighted graph, and applies graph neural networks for personalized computations.

CKAN [

37]: This paper introduces a novel Cooperative Knowledge-Aware Attention Network (CKAN) that explicitly encodes cooperative signals through heterogeneous propagation strategies while distinguishing the contributions of different knowledge neighbors using a knowledge-aware attention mechanism.

KGAN [

20]: A course recommendation model based on Knowledge Group Aggregation Networks, which utilizes a heterogeneous graph iteration that describes the relationships between courses and facts to estimate learners' learning interests, projecting learner behaviors and course graphs into a unified space.

KFGAN [

38]: based on a knowledge-aware fine-grained attention network, achieves consistency and coherence between collaborative filtering and knowledge graph information, draws on graph contrastive learning methods to further uncover latent semantic information within the knowledge graph.

5.3. Implementation Details

The experiments were conducted on a Windows operating system using the PyCharm Community Edition 2022 integrated development environment, with development carried out in Python 3.7. The following libraries were utilized: TensorFlow, NumPy, and Scikit-learn. The hardware configuration comprised a 24-core Intel Core i9-10920X CPU running at 3.5GHz, an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 Ti graphics card, 64GB of RAM, a 1TB solid-state drive, and a 4TB mechanical hard drive. Regarding the dataset partitioning, we divided the dataset into a training set and a testing set in an 8:2 ratio. The model parameters were initialized using the Xavier initialization method, with the number of epochs set to 50 and the batch size configured at 2048. The learning rate and L2 normalization coefficient were set to 2e-2 and 1e-5, respectively, while the knowledge graph embedding weight was set to 1e-2. The model's performance was evaluated in the context of Click-Through Rate (CTR) prediction, utilizing the Area Under the Curve (AUC) and Accuracy (ACC) metrics for evaluation.

5.4. Performance Comparison

Table 3 presents the performance results of the baseline models and the PGDB model.

Along with its variants in the context of Click-Through Rate (CTR) prediction on the MOOCCube dataset. The results indicate that the proposed PGDB model significantly outperforms the baseline models. Specifically, PGDB-s is a variant of PGDB that replaces the multi-head attention mechanism with a self-attention mechanism, while PGDB-g is another variant that substitutes the BiLSTM architecture in PGDB with Gated Recurrent Units (GRU). The following observations can be made from the table:

In prediction tasks, knowledge-aware recommendation models generally outperform classical recommendation models, with the exception of DKN. This may be attributed to the fact that knowledge-aware models effectively utilize knowledge graphs as auxiliary information, alleviating the high sparsity present in the course dataset.

The DKN model underperformed compared to classical models such as BPR and FM in course recommendations. This may be due to the knowledge graph embedding (KGE) method employed by DKN, which is better suited for intra-graph applications rather than recommendation tasks, resulting in suboptimal entity embeddings for item recommendations.

Among classical recommendation models, BPR demonstrated the best performance, as it leverages Bayesian methods to optimize the pairwise ranking loss function in recommendation tasks, facilitating increased attention to high-quality courses by more learners.

Within knowledge-aware recommendation methods, DKN exhibited the poorest performance, indicating that propagation-based approaches are superior to embedding-based methods.

The KGAN and RippleNet models significantly outperformed the CKAN and KGNN-LS models in course recommendations. A possible explanation for this is that the introduction of collaborative information may carry more noise, particularly in the face of the highly sparse nature of course recommendation data.

Compared to these state-of-the-art baselines, PGDB markedly outperforms the latest optimal KGAN and KFGAN models. This suggests that the PGDB model is more effective at uncovering the relationships between courses while emphasizing the transmission of important knowledge, thereby enhancing the accuracy of course recommendations.

Both PGDB and its variants consistently exceeded the performance of all baseline models, demonstrating the competitive advantage of the PGDB model in course recommendation. The superior performance of the PGDB model over PGDB-s highlights the benefits of the multi-head attention mechanism in simultaneously focusing on the transmission of multiple important information sources, which is conducive to performance enhancement. Although GRU is simpler compared to BiLSTM, this simplification may incur some performance loss.

5.5. Hyperparameter Influence

In this section, we will discuss the impact of hyperparameters on model performance.

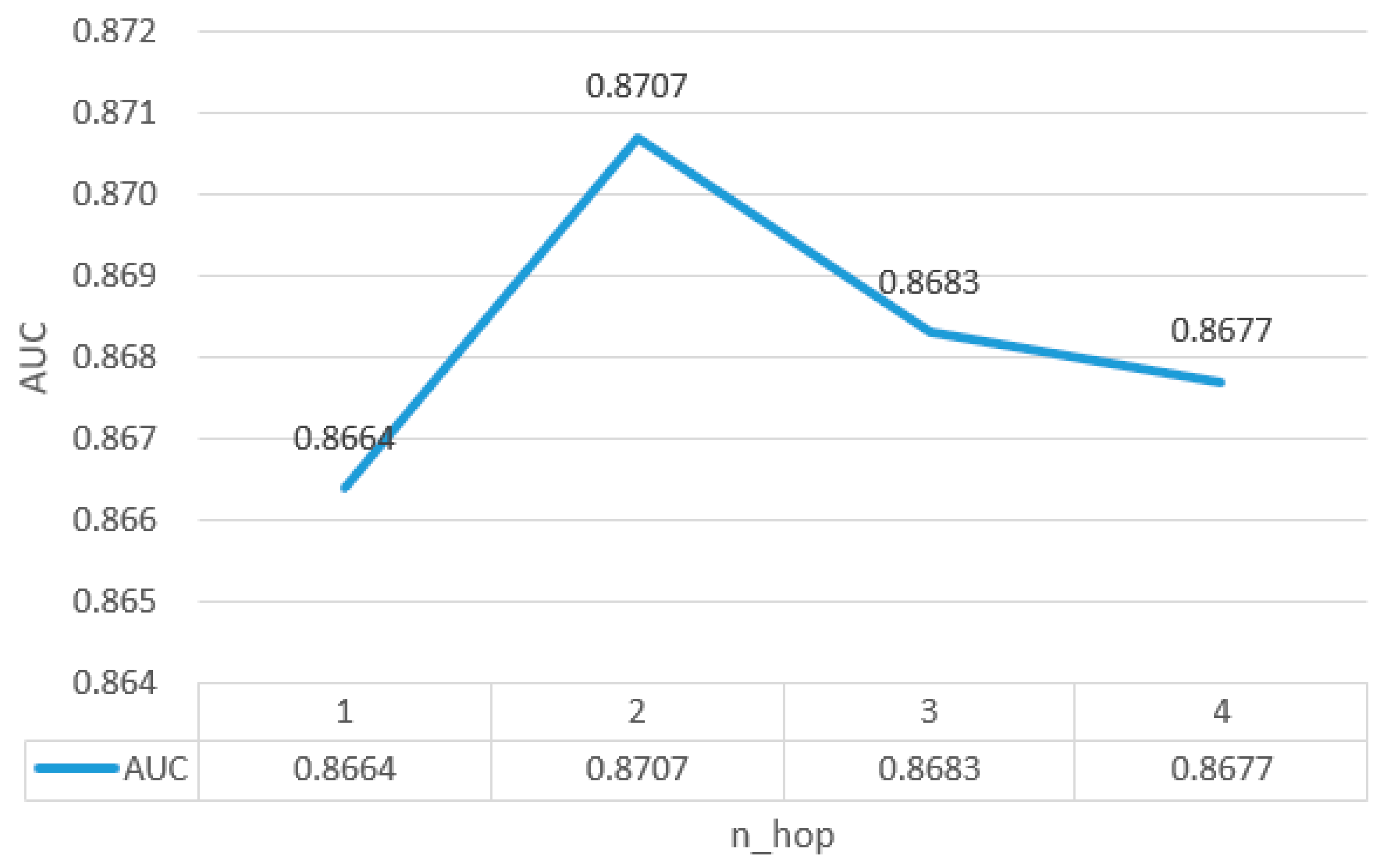

Figure 2.

Depth of course graph layer n_hop.

Figure 2.

Depth of course graph layer n_hop.

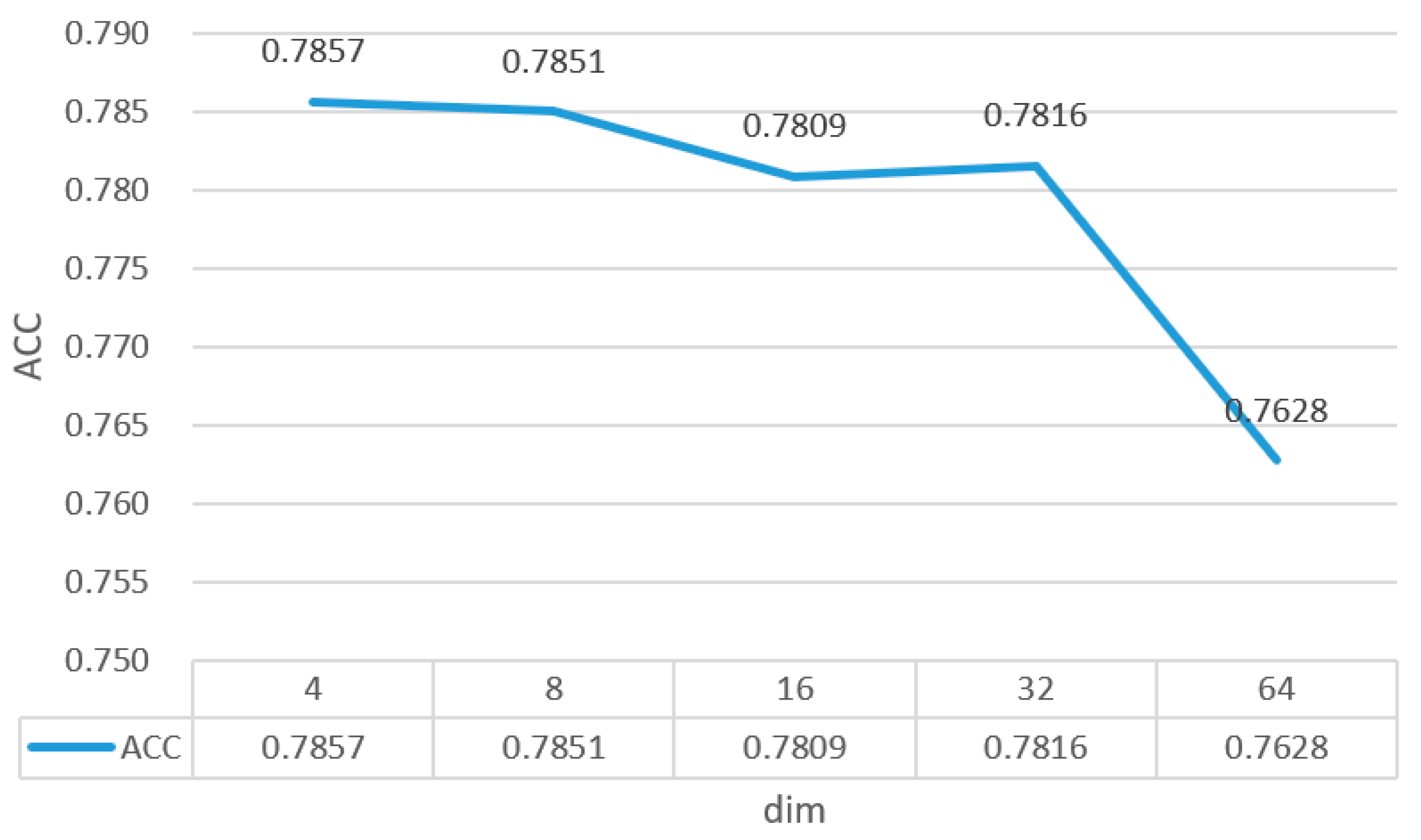

5.5.1. Number of Embedding Layers

In this section, we discuss the impact of the embedding dimensions of entities and relations on model performance. From the graph, it is evident that as the dimensions increase, the model's performance continuously declines. The PGDB model exhibits a gradual decrease in performance during the intermediate stages; however, as the embedding dimensions continue to rise, a significant deterioration in performance occurs. When the dimensions become excessively large, it may lead to overfitting. Therefore, an appropriate embedding dimension is crucial for effectively encoding the features of entities and relations.

Figure 3.

Embedding dimension dim.

Figure 3.

Embedding dimension dim.

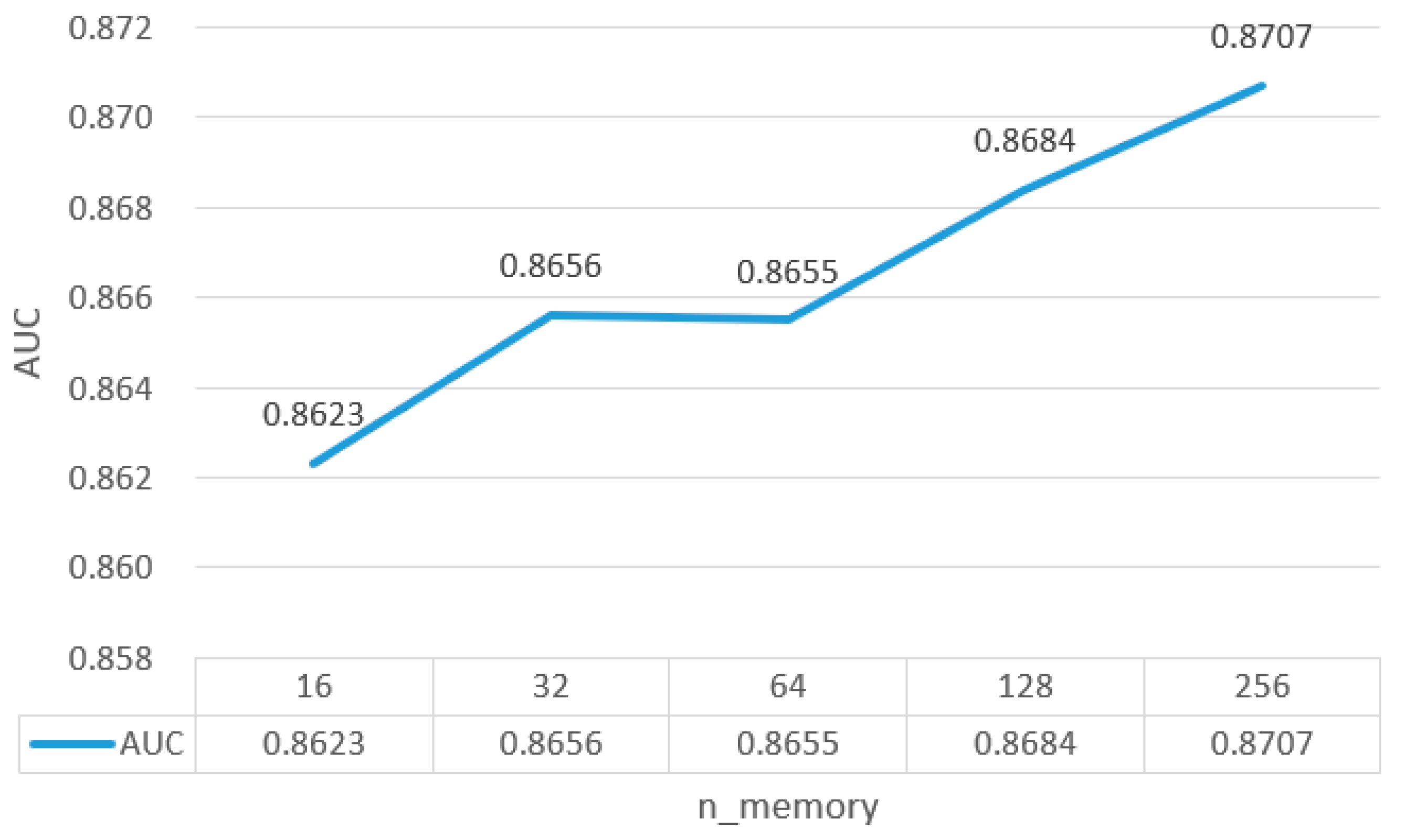

5.5.2. Rejoin Propagation Triplet Sizes

From the

Figure 4, it is evident that as the size of the triples increases, the model's performance continuously improves. However, due to the limitations of the experimental hardware, it is not feasible to further increase the triple size. Additionally, the training time for the model noticeably increases with the addition of more triples. Under the current hardware conditions, a triple size of 256 yields optimal performance, indicating that this size effectively captures the most relevant connection features of the entities. This configuration allows for better encoding of user characteristics while simultaneously mitigating the impact of noise.

Figure 4.

Rejoin propagation triplet sizes.

Figure 4.

Rejoin propagation triplet sizes.

In this section, we demonstrate the formidable competitiveness of our proposed model, PGDB and its variants, in click-through rate prediction through a comparison with baseline models. We also explore the impact of various hyperparameters on model performance, ultimately identifying the optimal hyperparameter combinations through extensive experimental studies. Each hyperparameter has a significant influence on the model, but we will not discuss them individually. As a specialized recommendation scenario, course recommendation inherits advanced technologies from the recommendation field. However, it faces certain challenges due to the increased sparsity of data compared to typical recommendation scenarios and the existence of sequential relationships between courses. Additionally, learner preference information is influenced by the learners' backgrounds, such as their majors, which may lead to heightened interest in specific series of courses.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes an end-to-end course recommendation model, PGDB, which seamlessly integrates bidirectional long short-term memory networks with knowledge graphs. PGDB accomplishes the course recommendation task through a knowledge graph diffusion module, a relation-aware attention network, and a temporal preference modeling and prediction module. This approach effectively alleviates the sparsity issue in course recommendations, better captures the sequential relationships between courses learned by students, and more thoroughly explores the varying interests of learners in different courses during the knowledge dissemination process. Experimental results demonstrate that PGDB has a significant advantage in CTR prediction tasks compared to the latest baseline models. Future research could focus on several directions: First, this study employs uniform neighbor sampling, which applies the same sampling strategy for nodes with many neighbors and those with very few neighbors, potentially hindering the extraction of representative features from neighbor nodes. Using a hierarchical sampling strategy might effectively improve the feature representation of nodes. Secondly, in data processing, we utilized the learner-course interaction matrix. However, during online learning, the lack of a good supervision strategy has led to high dropout rates. Future work could incorporate dropout rate data to gain better insights into the course learning situations of learners.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D., Q.L.; methodology, C.D.; software, Q.C., Y.X.; validation, C.D., B.H. and X.W.; formal analysis, Y.X., C.D.; investigation, C.D.; resources, Y.X., B.H., X.W.; data curation, Y.X., B.H., X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.C., C.D.; writing—review and editing, C.D.; visualization, C.D.; supervision, Q.C.; project administration, C.D.; funding acquisition, C.D., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Education of the People’ s Republic of China (Grant No. 20YJC880024), the Key Laboratory of Intelligent Education Technology and Application of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. jykf22029),Zhejiang Province educational science and planning research project (2023SCG369),University-Industry Collaborative Education Program(220906424035704).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Herlocker J L, Konstan J A, Borchers A; et al. An Algorithmic Framework for Performing Collaborative Filtering[J]. SIGIR Forum, 2017, 51, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick P, Iacovou N, Suchak M, et al. GroupLens: An Open Architecture for Collaborative Filtering of Netnews[C]. Acm Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 1994.

- He X, Liao L, Zhang H, et al. Neural Collaborative Filtering[C]. Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, 2017: 173–182.

- He X, Chua T-S. Neural Factorization Machines for Sparse Predictive Analytics[C]. Proceedings of the 40th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2017: 355–364.

- Hidasi B, Karatzoglou A, Baltrunas L, et al. Session-based Recommendations with Recurrent Neural Networks[J]. CoRR, 2015, abs/1511.06939.

- Zhou G, Mou N, Fan Y, et al. Deep interest evolution network for click-through rate prediction[C]. Proceedings of the Thirty-Third AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirty-First Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Ninth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, 2019: Article 729.

- Duan C, Sun J, Li K; et al. A dual-attention autoencoder network for efficient recommendation system[J]. Electronics, 2021, 10, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng G, Zhang F, Zheng Z, et al. DRN: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Framework for News Recommendation[C]. Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference, 2018: 167–176.

- Zhang F, Yuan N J, Lian D, et al. Collaborative Knowledge Base Embedding for Recommender Systems[C]. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2016: 353–362.

- Zhao N, Long Z, Wang J; et al. AGRE: A knowledge graph recommendation algorithm based on multiple paths embeddings RNN encoder[J]. Knowl. Based Syst., 2022, 259, 110078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Ma W, Jiang Y, et al. A MOOCs Recommender System Based on User's Knowledge Background[C]. Knowledge Science, Engineering and Management, 2021.

- Gao C, Zheng Y, Li N; et al. A Survey of Graph Neural Networks for Recommender Systems: Challenges, Methods, and Directions[J]. ACM Trans. Recomm. Syst., 2023, 1, Article 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaza R G, Cervantes E V V, Quispe L V C, et al. Online Courses Recommendation based on LDA[C]. Symposium on Information Management and Big Data, 2014.

- Li X, Li X, Tang J, et al. Improving Deep Item-Based Collaborative Filtering with Bayesian Personalized Ranking for MOOC Course Recommendation[C]. Knowledge Science, Engineering and Management: 13th International Conference, KSEM 2020, Hangzhou, China, August 28–30, 2020, Proceedings, Part I, 2020: 247–258.

- Xu W, Zhou Y. Course video recommendation with multimodal information in online learning platforms: A deep learning framework[J]. Br. J. Educ. Technol., 2020, 51, 1734–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian X, Liu F. Capacity Tracing-Enhanced Course Recommendation in MOOCs[J]. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 2021, 14, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Lu H, Qiu P; et al. Heterogeneous teaching evaluation network based offline course recommendation with graph learning and tensor factorization[J]. Neurocomputing, 2020, 415, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang S, Cai X. Bilateral knowledge graph enhanced online course recommendation[J]. Information Systems, 2022, 107, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Ma W, Guo L; et al. HGNN: Hyperedge-based graph neural network for MOOC Course Recommendation[J]. Inf. Process. Manage., 2022, 59, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Shen X, Yi B; et al. KGAN: Knowledge Grouping Aggregation Network for course recommendation in MOOCs[J]. Expert Syst. Appl., 2023, 211, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng W, Zhu P, Chen H; et al. Knowledge-aware sequence modelling with deep learning for online course recommendation[J]. Inf. Process. Manage., 2023, 60, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin Y, Liu Z, Sun M, et al. Learning entity and relation embeddings for knowledge graph completion[C]. Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2015: 2181–2187.

- Wang H, Zhang F, Xie X, et al. DKN: Deep Knowledge-Aware Network for News Recommendation[J]. Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference, 2018.

- Ji G, He S, Xu L, et al. Knowledge Graph Embedding via Dynamic Mapping Matrix[C]. Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2015.

- Sun Z, Yang J, Zhang J, et al. Recurrent knowledge graph embedding for effective recommendation[C]. Proceedings of the 12th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, 2018: 297–305.

- Wang X, Wang D, Xu C, et al. Explainable reasoning over knowledge graphs for recommendation[C]. Proceedings of the Thirty-Third AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirty-First Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Ninth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, 2019: Article 653.

- Wang H, Zhang F, Wang J, et al. RippleNet: Propagating User Preferences on the Knowledge Graph for Recommender Systems[C]. Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, 2018: 417–426.

- Wang H, Zhao M, Xie X, et al. Knowledge Graph Convolutional Networks for Recommender Systems[C]. The World Wide Web Conference, 2019: 3307–3313.

- Wang X, He X, Cao Y, et al. KGAT: Knowledge Graph Attention Network for Recommendation[C]. Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2019: 950–958.

- Zou D, Wei W, Wang Z, et al. Improving Knowledge-aware Recommendation with Multi-level Interactive Contrastive Learning[C]. Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, 2022: 2817–2826.

- Zhang Z, Zhang L, Yang D; et al. KRAN: Knowledge Refining Attention Network for Recommendation[J]. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data, 2021, 16, Article 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu J, Luo G, Xiao T, et al. MOOCCube: A Large-scale Data Repository for NLP Applications in MOOCs[C]. Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020.

- Seber G A, Lee A J. Linear regression analysis[M]. John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

- Rendle S, Freudenthaler C, Gantner Z, et al. BPR: Bayesian personalized ranking from implicit feedback[C]. Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, 2009: 452–461.

- Rendle, S. Factorization Machines with libFM[J]. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol., 2012, 3, Article 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Zhang F, Zhang M, et al. Knowledge-aware Graph Neural Networks with Label Smoothness Regularization for Recommender Systems[C]. Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2019: 968–977.

- Wang Z, Lin G, Tan H, et al. CKAN: Collaborative Knowledge-aware Attentive Network for Recommender Systems[C]. Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2020: 219–228.

- Wang W, Shen X, Yi B, et al. Knowledge-aware fine-grained attention networks with refined knowledge graph embedding for personalized recommendation, Expert Systems with Applications, Volume 249, Part B, 2024, 12810.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).