Key Points: The concept of biased agonism; whereby a drug preferentially activates beneficial signaling pathways rather than those that cause side effects; has generated enthusiasm for the development of improved opioid painkillers. Although the first rationally designed biased opioid; olicerdine; recently received FDA approval; its clinical profile is similar to that of existing opioids. Nevertheless; retrospective studies characterizing biased signaling of clinically used opioids like buprenorphine suggest that bias optimization may still be a viable strategy for creating novel analgesics that are safer and more effective than morphine.

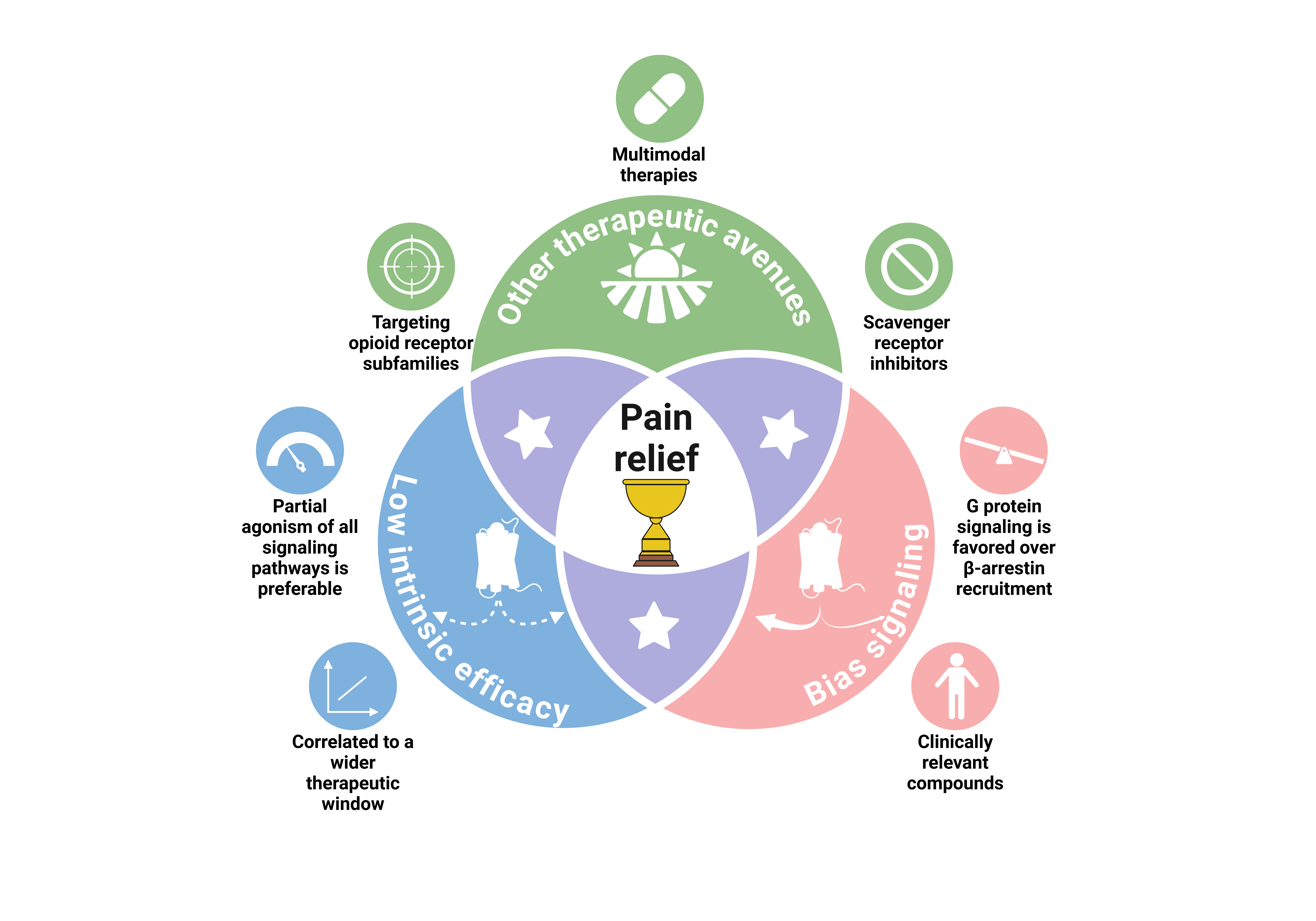

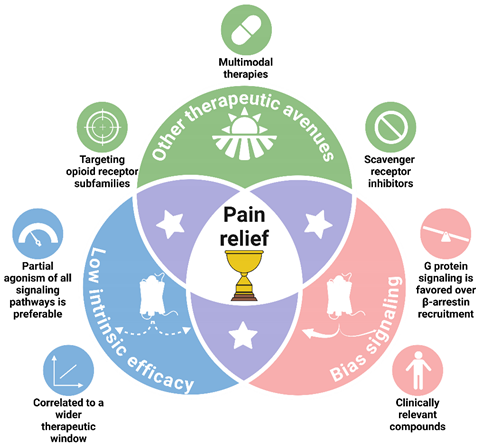

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Chronic pain is a pervasive and debilitating condition that imposes a substantial burden on afflicted individuals, significantly compromising their quality of life and overall well-being. Despite its high prevalence, effective management of chronic pain remains a challenge [

1]. Unsatisfying treatment negatively affects patients’ health and well-being, interfering with essential daily activities [

2]. Extracts of

Papaver somniferum (opium poppy) have been used for thousands of years to relieve pain [

3]. It is only in the 19

th century that morphine was isolated from the plant and characterized as its primary active pharmaceutical ingredient [

4]. To date, opioids, especially morphine, remain the gold standard for the treatment of several types of pain ranging from acute to chronic pain. However, opioid-derived analgesics provide only modest, short-term relief for patients suffering from chronic non-cancer pain, such as neuropathic pain [

5]. Moreover, they are associated with a wide range of adverse effects, such as constipation, respiratory depression, tolerance, hyperalgesia, and abuse liability, which can seriously affect patient adherence to treatment [

6]. Indeed, up to 30% of patients fail to achieve the expected pain relief with morphine, and 70% experience debilitating adverse events [

7]. Despite these drawbacks, morphine remains on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines, as no other effective analgesics provide comparable pain relief [

8]. Over the last 50 years, more than 60 new analgesics have been introduced onto the market. However, most of these are simply new formulations of existing drugs [

7]. In fact, 88% of these new pain medications have showed very limited improvement over existing treatments in terms of efficacy or adverse effects. Over the last decade, their increasing availability and abuse potential have led to the opioid crisis and an epidemic of overdose deaths with serious social and economic consequences [

9,

10]. The modest pain relief, undesirable effects, and overuse/misuse of these addictive drugs pose real dilemmas for healthcare professionals [

11]. This has prompted researchers to further elucidate the mode of action of opioids and to intensify their search for better versions of these analgesics.

2. Understanding Opioid Pharmacology Design Better Analgesic Drugs

Due to the extensive use of morphine, and opioid derivatives for their potent analgesic effects on acute pain, researchers have long been interested in understanding the mechanism of action of opioids, in parallel with advances in ligand and receptor pharmacology. The opioid receptor family comprises four members: δ (DOP), κ (KOP), µ (MOP), and the opioid-related nociceptin (NOP) receptors [

12]. Morphine and its derivatives bind to the µ-opioid receptor and trigger the activation of a signaling cascade downstream of the receptor (

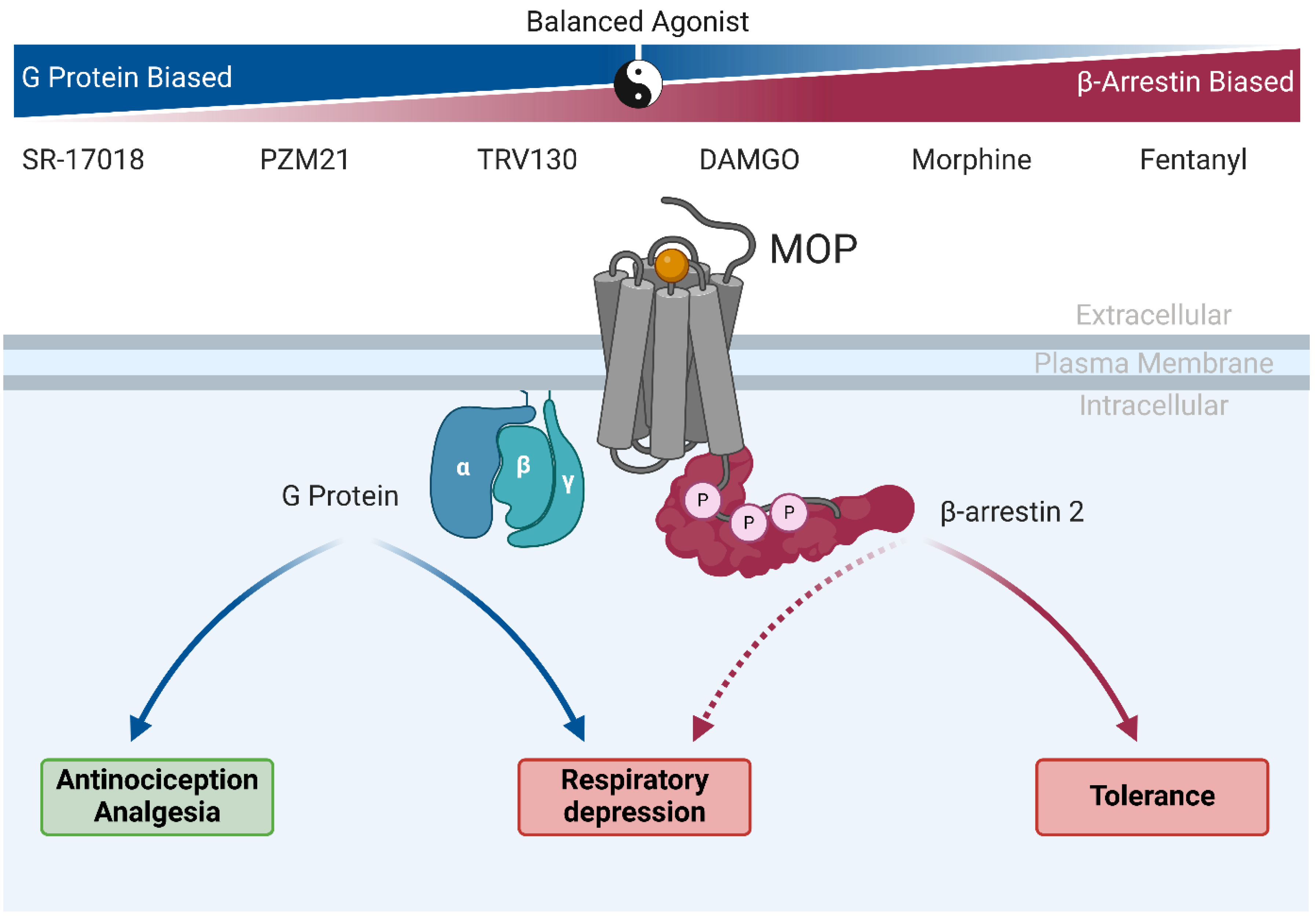

Figure 1) [

13]. It is now widely accepted that all opioid receptors activate pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive G proteins, notably Gα

i/o, which inhibit adenylyl cyclase isoforms and thus reduce intracellular levels of cyclic AMP [

14,

15]. After dissociation of Gα

i, the Gβγ dimer can interact with inwardly rectifying potassium channels (Kir

3) and facilitate potassium efflux [

16,

17]. The Gβγ dimer can also directly interact with voltage-activated Ca

++ channels to reduce calcium entry [

18,

19]. Overall, G protein activation by opioid receptors leads to membrane hyperpolarization and inhibition of neuronal activity [

20]. These receptors are also known to mediate post G protein-dependent signaling events by inducing recruitment of GRKs 2 and 3 and β-arrestins to the C-terminal tail of the receptor, attenuating G protein-signaling and promoting phosphorylation of c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and other mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Recruitment of β-arrestins by MOP agonists drives desensitization and internalization of MOP receptors, thereby fine-tuning analgesic responses mediated by MOP activation.

In the case of MOP, the link between intracellular signaling and the physiological effects of opioids was discovered in the 1990s. First, Raffa,

et al. [

26] used siRNA targeting Gα

i proteins

in vivo and found that knockdown of Gα

i2 blocked the analgesic action of morphine. Later, Bohn,

et al. [

27] showed that in mice lacking β-arrestin 2, the analgesic effect of morphine was enhanced and the adverse effects usually triggered by MOP activation were significantly reduced. They also concluded that the analgesic action of morphine was achieved via a Gα

i protein-dependent mechanism, whereas constipation and respiratory depression were triggered by β-arrestin 2 recruitment [

28]. Tolerance has also been linked to the recruitment of β-arrestin 2 in knockout mice, which showed no decrease in morphine analgesic potency after chronic treatment [

28,

29]. These findings, confirmed by others, significantly shaped the development of opioid ligands towards Gα

i-biased agonists [

30,

31,

32,

33].

Nevertheless, some controversy remains as to the signaling pathways leading to undesired effects; consequently, the perfect dichotomy between the effects triggered by G proteins and β-arrestin 2 may not be as straightforward as originally assumed. Indeed, in a recent international multisite study evaluating the effects of morphine and fentanyl, the authors showed similar levels of respiratory depression and constipation in β-arrestin 2 knockout mice compared to their wildtype littermates [

34]. This study corroborates the effects of morphine- and fentanyl-induced respiratory depression and constipation observed in various phosphorylation-deficient MOP knock-in mice (these mutant receptors showed decreased recruitment of β-arrestin 2 upon activation) [

32,

35,

36]. These findings challenge earlier studies that suggested a clear role for β-arrestin 2 in mediating opioid side effects, such as respiratory depression and constipation. Recent studies have questioned these conclusions by highlighting methodological differences, such as variations in drug delivery methods or compensatory mechanisms in knockout models, which may have confounded earlier results [

37]. Newer approaches using phosphorylation-deficient MOP knock-in mice [

32] or conditional knockouts have provided more nuanced insights into receptor signaling that were not apparent in earlier whole-animal knockout models[

37]. Thus, highlighting additional limitations of whole animal knockouts and genetic strain differences used to decipher pharmacological contributions relevant to human patients [

38].

It is widely accepted that MOP-induced analgesia depends on G protein activation, and that this effect is enhanced in β-arrestin 2 knockout mice [

38]. However, other cellular mechanisms might be responsible for the adverse effects of µ-opioid agonists that cannot be explained by the convenient but overly simple version of biased agonism characterized by a dichotomy between G protein and β-arrestin signaling. Therefore, it underscore the need for more robust methodologies to evaluate biased signaling and its clinical implications.

3. GPCRs: From Simple Switches to Integrated Signaling Processors

The G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family is among the most important classes of druggable targets in the human proteome, with nearly 40% of drugs prescribed across various therapeutic fields acting through the modulation of these proteins [40]. Traditionally, GPCRs were considered as simple toggle switches, turning ‘on’ or ‘off’ pre-selected ensembles of signaling modalities [41]. GPCR activation often leads to the recruitment of multiple membrane and cytosolic proteins, enabling them to engage in multiple signaling pathways. Thus, the classical view of these receptors as simple heterotrimeric G protein activators has been supplanted by their roles as complex modulators of a variety of intracellular signaling pathways [41]. In the late 1990s, a new concept called ligand-directed signaling, subsequently renamed biased signaling or functional selectivity, emerged in the field of GPCRs [43]. This new model is based on the ability of a receptor ligand to modulate (activate or block) only a subset of signaling pathways that are normally activated by endogenous or balanced agonists (

Figure 2). In other words, a biased ligand can induce a distinct receptor conformation that modulates only a specific subset of the signaling repertoire [44]. Of particular interest has been the demonstration that ligands behaving as agonists for a given signaling pathway can act through the same receptor, as antagonists or even inverse agonists on a different pathway in the same cell [44]. As a result, a lack of efficacy for a single pre-selected signaling pathway does not necessarily translate into a lack of receptor activation and concomitant cellular and physiological responses. The concept of biased signaling has brought new opportunities for the development of therapeutics and is rapidly changing the way drugs are screened and selected. Researchers could thus design molecules that would activate only the beneficial signaling pathways leading to the desired pharmacological effects, while avoiding undesirable effects [46]. To design such compounds, it is necessary to understand the receptor-ligand system in detail, and to decipher the relationship between signaling pathways and physiological effects

in vivo [46,47]. Unfortunately, these links are not always obvious, often remain unknown and neglected, and may even be distinct between different cell types, tissues, or species in which the same receptors are expressed. For instance, it has been shown that β-arrestin-biased ligands of dopamine D

2 receptors behave as agonists in cortical regions and as antagonists in the striatum, these region-specific actions being related to the differential expression levels of β-arrestins and G protein-coupled receptor kinases across brain structures [48]. In addition, species differences can significantly influence clinical translation. In this respect, the G protein-biased agonist nalfurafine has been reported to exhibit greater biased signaling to human KOP than its rodent counterpart [49].

The translation from biased agonism in in vitro studies to in vivo efficacy for market release is facing several challenges. These include potential differences in bias profiles between human and animal receptor orthologs, and the need to thoroughly characterize the true efficacies and signaling profiles of biased candidate molecules beyond the simple comparison of G protein- and β-arrestin-dependent pathways. Failure to adequately address these factors during the drug discovery process may contribute to the high attrition rate of new opioid drug candidates in clinical development [50,51]. Interestingly, retrospective analyses of clinically approved opioid drugs for biased signaling can improve understanding of relevant signaling pathways and help future drug development by identifying patterns and mechanisms that can be leveraged to design more effective and safer opioid analgesics.

4. Old Drugs, New Tricks: MOP-Biased Agonists in Clinically Approved Opioids

The concept of biased signaling was not yet known when the majority of opioids currently in clinically use first appeared on the market. Nonetheless, deciphering the signaling effects of these clinically relevant drugs can be helpful in better understanding the beneficial and adverse effects associated with opioids. One of the first reports of biased properties of clinically used opioids was the difference in MOP internalization observed between cells treated with Met-enkephalin and morphine [53]. Met-enkephalin was found to trigger rapid internalization of MOP, whereas morphine did not promote receptor endocytosis. Since these first demonstrations, several studies have revealed the biased properties of MOP ligands [

24,53]. McPherson et al. [54] compared the intrinsic efficacies for G protein activation and β-arrestin 2 recruitment of 22 preclinical and clinical MOP agonists. Although the authors did not calculate bias factors (relative efficacies of a ligand for these two signaling pathways), they described fentanyl and alfentanil, two opioids used in surgical analgesia with a rapid onset, and etorphine, a tranquilizer used in veterinary medicine, as MOP ligands that favor recruitment of β-arrestin 2 [54] (

Table 1). Fentanyl and sufentanil were also assessed in a recent study investigating the functional selectivity of novel MOP ligands, and these two synthetic opioids showed a strong bias towards β-arrestin 2 recruitment compared with DAMGO used here as the reference compound [55]. Interestingly, morphine has been described as a balanced ligand or agonist slightly biased towards β-arrestins (

Table 1).

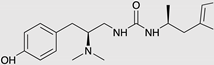

Buprenorphine is a drug used to treat opioid abuse disorders, and has recently been exploited for its analgesic action [57]. Buprenorphine binds to and activates all four opioid receptors, making its pharmacology even more complex. It is a MOP agonist, a KOP and DOP antagonist, and a weak NOP agonist [58]. Moreover, buprenorphine is a biased agonist at the MOP level as it activates Gαi but fails to recruit β-arrestin 2 [54]; it is therefore reasonable to assume that this prescribed drug will exert similar analgesic efficacy to that of morphine and a lower risk of undesired effects [58] (Table 1). Furthermore, owing to its complex pharmacology at opioid receptors, buprenorphine is thought to have a lower abuse potential [60]. Nevertheless, it should be noted that norbuprenorphine, an active degradation metabolite of buprenorphine, presents a very different signaling profile at MOP [58]. Norbuprenorphine is a potent G-protein activator, with morphine-like efficacy and better potency than DAMGO. However, unlike buprenorphine, it strongly recruits β-arrestin 2, with a profile similar to that of DAMGO [54]. Consequently, buprenorphine dosing in patients must be carefully monitored to avoid norbuprenorphine-induced adverse effects [60].

Finally, levorphanol is a non-selective opioid agonist with complex pharmacodynamic properties [61]. Synthesized in the late 1940s as an alternative to morphine, this pan-opioid receptor agonist is also an

n-methyl-

d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist that also acts as a norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) [62]. Often referred to as the “forgotten opioid,” levorphanol is neither known nor prescribed by most physicians [62,63]. It has been revisited, and extensive pharmacological characterization has shown that levorphanol acts as a moderate µ-biased agonist favoring G protein activation at several MOP splice variants [65] (

Table 1). In addition, less respiratory depression was observed with levorphanol than with morphine at a dose 5 fold higher than their analgesic ED

50 [65]. This new classification, combined with its safety profile, could give a new start to this forgotten opioid drug [65,66].

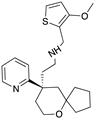

5. Oliceridine, the Prototype MOP-Biased Agonist

Oliceridine, also known as TRV130 or Olinvik™, its commercial name, is a MOP ligand developed by the biotech company Trevena, Inc. (NASDAQ: TRVN, Chesterbrook, PA, USA). This compound is a selective MOP small molecule that was discovered after screening a compound library and a structure-activity relationship study, where it displayed a profile biased towards Gα

i activation (

Table 1) [68]. Oliceridine was then tested

in vivo in mice and rats, and it was noted that oliceridine had similar efficacy to morphine in acute and postoperative pain models. However, due to its lower efficacy in β-arrestin 2 recruitment following MOP activation, oliceridine displayed an increased therapeutic window (range of drug doses providing safe and effective therapy) compared to morphine for assays of constipation and respiratory suppression [68]. These encouraging results, combined with early phase III results prompted Trevena to advance oliceridine through the drug discovery process and file a new drug application in November 2017 to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which was accepted in January 2018 [70,71]. Unfortunately, in October of that year, the FDA’s Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee (AADPAC) voted against approval of oliceridine [72]. The FDA recognized that oliceridine demonstrated statistically significant pain relief compared with placebo, and that some doses had fewer side effects than morphine. However, doses with fewer undesired effects were also less effective than morphine in relieving pain, and therefore, did not support a safer profile [73]. Nevertheless, the FDA agreed that Trevena’s safety database supported a maximum dose of 27 mg per 24 h of oliceridine. The company also agreed to conduct a study to collect the requested QT interval data (the time elapsed between the start of the Q wave and the end of the T wave on the electrocardiogram), as those administered during the new drug application were deemed inadequate for the proposed dosing [74]. The FDA report suggests there is considerable interest in oliceridine as a new analgesic, but more safety data is required before approval.

In 2019, Trevena announced the launch of a QT interval study of healthy volunteer for oliceridine with the aim of collecting additional data requested by the FDA prior to the re-submission of the new drug application for this molecule [75]. Trevena also published a clinical safety study showing that, unlike morphine and hydromorphone, no dose adjustment of oliceridine is required in patients with renal dysfunction or mild-to-moderate hepatic impairment. However, dose reduction and careful monitoring should be carried out in patients with severe hepatic dysfunction [76]. In early 2020, Trevena resubmitted a new drug application to the FDA, including data from a multi-dose QT study in healthy volunteer, non-clinical data confirming levels of an inactive metabolite, and drug product validation reports [76,77]. These new data helped convince the FDA of the safety of oliceridine with a maximal dose of 27 mg/day, leading to the approval of oliceridine in August 2020 [79]. The FDA's decision underscored the need for new opioid analgesics with improved safety profiles, especially in hospital settings where intravenous administration is required [80]. This was the first approval of a biased agonist specifically developed for MOP. Unfortunately, although the rational design was initially very elegant, oliceridine has a similar benefit-risk profile to that of other previously approved opioids, with some evidence of a slightly improved respiratory safety profile [80,81]. Following FDA approval, oliceridine was classified as a Schedule II controlled substance by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). This classification reflects its abuse potential, similar to that of other opioids, and requires careful monitoring and control during clinical use [83,84]. Since its approval in the U.S., oliceridine has been introduced to the Chinese market in the first half of 2023 by Jiangsu Nhwa Pharmaceutical, in partnership with Trevena [85].

Follow-up studies have shown that olicerdine induces less respiratory depression than morphine at equianalgesic doses, regardless of age and body mass index, two factors known to exacerbate morphine-induced respiratory depression [85,86]. Furthermore, oliceridine seems to be better tolerated than morphine by patients, reducing the use of rescue antiemetics [87,88]. Ongoing research aims to further elucidate the efficacy and safety of olicerdine in broader clinical settings and explore its potential applications in other pain management paradigms such as acute pain after burn injury [90].

Overall, the approval of oliceridine is an encouraging step forward in pain management, offering a novel approach to opioid analgesia with a potentially improved safety profile. Its development and approval represent a significant milestone in addressing the challenges associated with traditional opioid therapies.

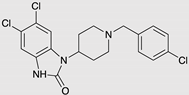

6. MOP-Biased Ligands in Preclinical Development

Although oliceridine was the first specifically designed MOP-biased ligand to enter clinical trials, the search for other MOP ligands has not stopped. Indeed, in recent years, many MOP-biased ligands have been reported to be effective analgesics in preclinical studies (

Figure 3). Among the ligands developed are PZM21 [90] and SR-17018 [55] (

Table 1).

PZM21 is a MOP-selective opioid agonist and KOP antagonist developed after virtual library screening using the MOP crystal structure, followed by a structure-activity relationship study. Like oliceridine, this compound has a structure that is unrelated to other known opioids. Thus, as recently suggested, entirely new molecular entities may exhibit the same primary outcome (i.e., analgesia), but may also be accompanied with by their own range of unwanted effects, such as glial activation and interactions with cytokines, which may affect the immune system’s ability to fight potential infections [91]. PZM21 was described as an antinociceptive compound in acute- and formalin-induced tonic pain tests. At the cellular level, PZM21 was initially reported to activate the Gαi pathway with morphine-like potency and to not trigger β-arrestin 2 recruitment. This new entity is as effective as morphine and exhibits a prolonged duration of action in both hot-plate and tail-flick studies of acute thermal nociception [90,92]. In addition, it causes less constipation than morphine and presents no respiratory suppression or rewarding effects at doses below the maximal effective analgesic dose (equivalent to 10 mg/kg of morphine). In a subsequent study of PZM21 by another research team, it appeared that this compound was as potent as morphine in engaging the Gαi pathway, but also seemed to promote recruitment of β-arrestin 2 [94]. The authors also examined the effects of PZM21 on respiratory suppression using whole-body plethysmography. Their results demonstrated that PZM21 was comparable to morphine in inducing respiratory depression at an equianalgesic dose [94]. The authors even tested a separately synthesized batch of PZM21 to confirm their results. Thus, PZM21 appears to resemble morphine more than a pure G-protein biased agonist. However, a recent study showed that, unlike clinically relevant opioids, PZM21 was unable to induce reward-associated behaviors in conditioned place preference and locomotor sensitization experiments in mice, and in intravenous self-administration in rats [92].

SR-17018 is a MOP agonist from a series of MOP-targeting compounds recently reported to display a wide range of bias factors, from molecules favoring β-arrestin recruitment to ligands with a strong G-protein bias. Here, the authors compared the dose-response curves of their new compounds, including SR-17018, and clinically relevant opioids, such as morphine, fentanyl, and sufentanil, on respiratory depression and analgesia. They found a significant correlation between therapeutic window and bias factor, meaning that the more a ligand is biased towards G protein activation, the safer the compound is with regard to respiratory events [55]. In this study, it is not only the fact that the ligand is a biased agonist, but also the extent to which the ligand is biased, which is relevant for compound safety. SR-17018 showed a >100-fold preference for G proteins over β-arrestin for murine MOP, as well as sustained antinociceptive action in acute thermal pain paradigms in mice. However, unlike morphine and fentanyl, SR-17018 did not induce signs of respiratory depression at the analgesic dose, thus drastically increasing its therapeutic window to nearly 30 times the ED50 for analgesia (for reference, the therapeutic windows of morphine and fentanyl are at 5- and 2-fold the ED50, respectively). In a follow-up study, the authors showed that a 6-day pretreatment with SR-17018 did not impair its own analgesic potency nor that of morphine in an acute thermal pain test, indicating that SR-17018 does not seem to induce tolerance at MOP [94]. This result was confirmed by the fact that [35S]-GTPγS binding was not reduced in the periaqueductal grey membranes from animals subjected to chronic treatment with SR-17018 (whereas a significant decrease in [35S]-GTPγS binding was observed in morphine-treated animals) [94].

Finally, a recent report on the poses of fentanyl, carfentanyl, and lofentanyl in molecular dynamics simulations revealed that residue M1533.36 of MOP is crucial for inducing β-arrestin 2 recruitment after fentanyl stimulation [96]. Moreover, they showed that the n-aniline group of fentanyl and its derivatives were drivers of β-arrestin 2 recruitment at MOP. As a result, newly synthesized analogs without the n-aniline ring exhibited a profile biased towards Gαi activation. Interestingly, a second study revealed that carfentanil, unlike fentanyl, was able to interact with available residues Y1282.64 or I2966.51 via its 4-carbomethoxy moiety [96]. In parallel, they calculated the bias factor of carfentanil and other fentanyl derivatives from bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assays, with carfentanil being the only one to show a significant bias towards β-arrestin 2 recruitment. These new important structural insights may open the way for the development of potent MOP-biased ligands based on the fentanyl chemical scaffold in the near future. Moreover, the recent resolution of MOP bound to different ligands has paved the way for receptor-based virtual screening and possibly AI-assisted drug discovery [12,97,98].

7. MOP-Biased Ligands Versus Low Intrinsic Efficacy Ligands at the µ-Opioid Receptor

Following multiple studies over the past five years, MOP-biased ligands as an avenue for pain therapies were found to be less of a clear solution than originally thought [100]. Herein, work previously carried out to establish a strong correlation between β-arrestin 2 recruitment and debilitating MOP-related side effects was revisited by a consortium of three different laboratories [34]. The main findings of these experiments led to a discrepancy between the original work and current understanding [27]. The role of β-arrestin 2 in side effects has been reconsidered with respect to respiratory depression and is now thought to be dependent on G protein activation [34]. However, G protein activation is still considered the primary signaling pathway relevant for antinociceptive action, and the development of tolerance to analgesic compounds is related to receptor desensitization via β-arrestin 2 recruitment following GRK phosphorylation [32,100]. Hence, the development of biased MOP ligands remains relevant.

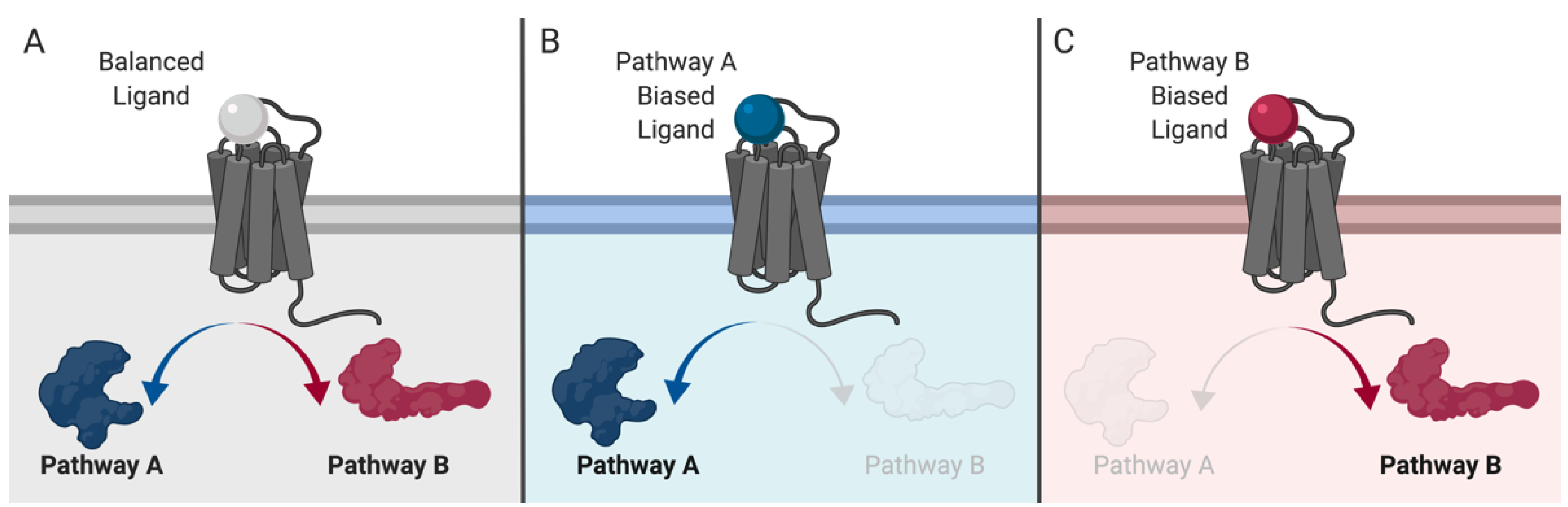

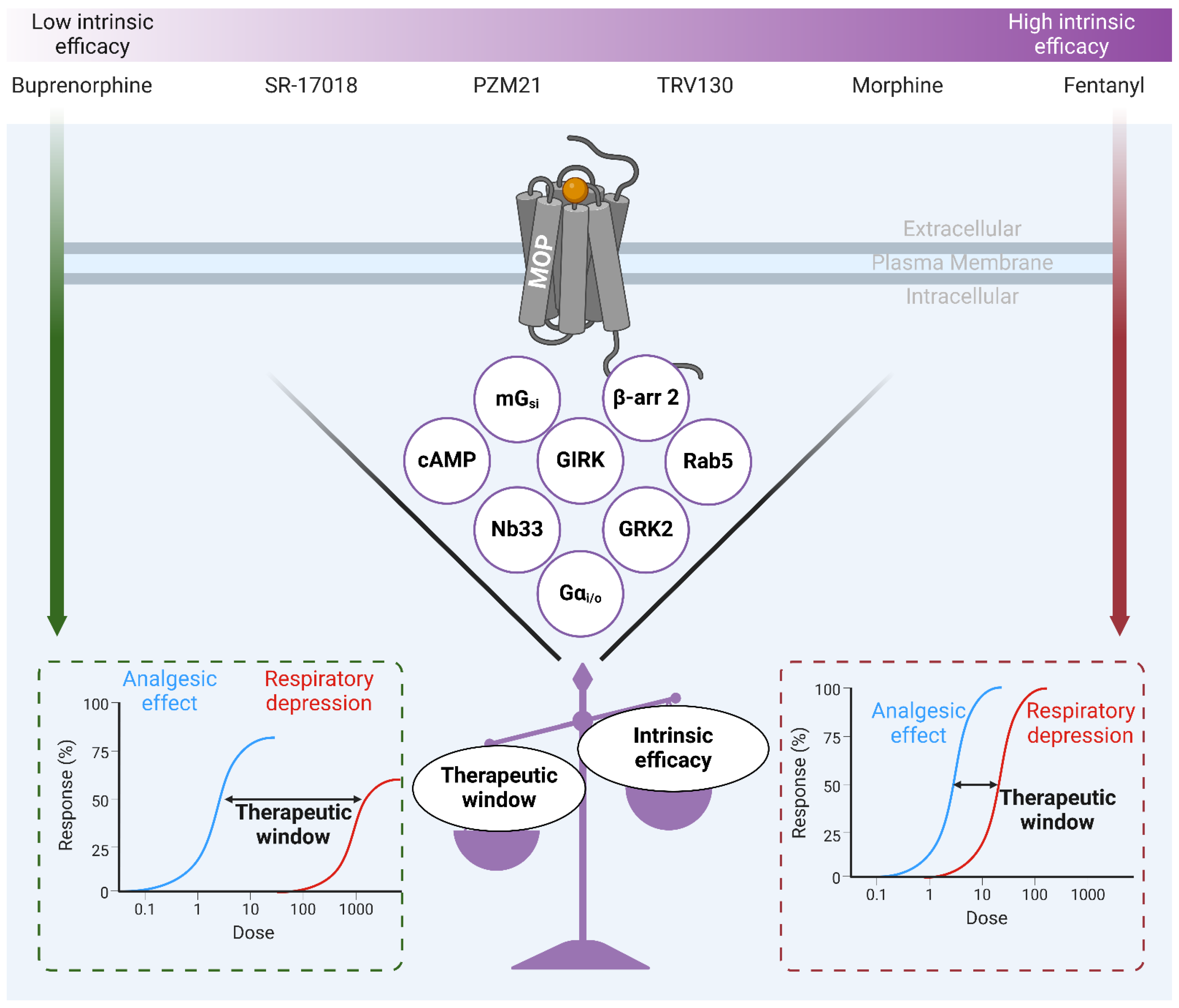

In 2020, Gillis

et al. [101] posited that a low intrinsic efficacy component (

i.e., partial agonism across all signaling pathways) of opioid agonists correlated with a better analgesic effect/side-effect profile. In fact, they hypothesized that the improved safety profiles of biased opioid ligands were due to their low intrinsic efficacy, rather than the bias

per se (

Figure 4). They suggested that these molecules were previously interpreted as biased ligands because the original assessment of bias had been performed using assays in which G protein responses were amplified (

i.e., cAMP accumulation) but β-arrestin recruitment responses were not. They used assays with minimal amplification (recruitment of Nb33 (a biosensor for the active state of MOP [102]), mGsi (modified Gα

i subunit recruited to the receptor upon activation [103]), GRK2 and β-arrestin 2) which may be more relevant in reflecting efficacy. Their findings suggest that TRV130, PZM21, buprenorphine, and SR-17018 are agonists with low intrinsic efficacy rather than biased ligands, and that there is a strong correlation between the efficacy of receptor activation, G protein coupling, and β-arrestin recruitment and improved side-effect profile. Interestingly, the latter study was re-analyzed by Stahl and Bohn [105], and their analysis showed that bias was the main driving force in predicting desirable pharmacological properties. Thus, partial agonism in all signaling pathways may be a determining factor in the development of safer opioid analgesics, but it is certainly not the only one and it should not overshadow all previous research on biased compounds.

8. Abuse Liability and Tolerance of Novel MOP Ligands in the Current Opioid Crisis

The current opioid epidemic is largely related to increased opioid prescribing, misuse, overuse, and abuse. The development of illicit synthetic opioids, more potent than morphine (e.g., carfentanil is 10,000 times more potent than morphine or nitazene compounds which often require multiple doses of naloxone to reverse severe side effects), has also contributed to the higher risk of death from overdose [105,106,107,108,109]. The opioid crisis is particularly visible in North America (predominantly in the U.S. and Canada) and Australia, while European and low-income countries seem less affected [111]. Over the past 20 years, opioid consumption (legal and illegal) in the U.S. has increased almost 15-fold, resulting in over 33,000 opioid-related deaths in 2015 [10,111]. After the U.S., Canada is the country with the highest per capita consumption of prescribed opioids in the world; however, when morphine equivalents dispensed are considered, Canada ranks first [112]. The opioid crisis has prompted the search for analgesics with reduced abuse potential, and it is legitimate to think that biased MOP ligands could be a possible solution to this growing epidemic.

Analgesia has been extensively linked to G-protein activation by MOP, and some of the adverse effects, such as tolerance, have been linked to the recruitment of β-arrestin 2. Although opioid abuse can result in addiction and physical dependence, activation of the reward circuitry by opioids has not yet been positively correlated with a specific cellular signaling pathway. However, there is some evidence indicating that β-arrestin 2 knockout (KO) mice display similar drug addiction withdrawal symptoms to their wild-type littermates [29]. Accordingly, the same research group showed that dopamine, considered a key player in addiction, was released to a greater extent in the striatal region of β-arrestin 2 KO mice following morphine treatment than in WT mice. In addition, β-arrestin 2 KO mice spent more time in the drug chamber during a conditioned place preference assay [114]. Altogether, these results strongly suggest that morphine-induced rewarding effects are not triggered by β-arrestin 2 signaling, but rather by G protein engagement. Thus, the abuse potential of G protein-biased MOP agonists is expected to be as high if not higher than that of other opioids.

The MOP-biased ligand oliceridine was assessed during preclinical development for its morphine-like reward effects. Self-administration in rats showed that oliceridine triggers the same rewarding behaviors as oxycodone, another opioid analgesic with high abuse potential [114]. Intracranial self-stimulation in rats and place conditioning experiments in mice showed that oliceridine has the same abuse potential as other opioid drugs.[115,116] This has also been assessed in a randomized clinical trial involving healthy volunteers who reported a ‘high’ on the drug effects questionnaire, confirming the abuse liability of oliceridine [117].

On the other hand, PZM21 was also assessed for its abuse potential in a conditioned place preference test on mice. In the first report on PZM21, the authors showed that chronic injections of this compound at submaximal doses did not induce place preference. In the same study, the authors also reported that the use of oliceridine alone failed to promote any place preference [90]. Therefore, knowing that oliceridine promotes reward-seeking behavior, the abuse potential of PZM21 could not be established. In another independent study of PZM21, the inability to induce place preference was demonstrated using increasing doses of PZM21. This confirmed the lack of abuse potential of this new entity [92]. However, the chronic administration of PZM21 resulted in signs of physical withdrawal in the naloxone-precipitated jump paradigm [92]. It has not been established whether PZM21’s lack of reward effects is due to its unique biased signaling profile at the MOP or whether this can be ascribed to its antagonistic properties at the KOP or to its atypical chemical structure.

Finally, it was recently reported that the G protein-biased MOP agonist SR-17018 fails to induce analgesic tolerance, but also displays fewer signs of physical dependence than morphine after chronic administration [119]. The authors also showed that administration of SR-17018 reversed signs of withdrawal upon morphine pump removal, with efficacy comparable to that of buprenorphine [119]. Sustained analgesic potency and low dependence liability confer highly desirable properties on SR-17018, prompting further characterization of this promising compound. Importantly, to date, no clinical trials have been conducted to investigate the analgesic properties or safety profiles of SR-17018 and PZM21.

9. Alternatives to Biased Signaling at the µ-Opioid Receptor

Despite decades of pain research, we are faced with the awarness that the initial approaches taken were undoubtedly incorrect. While research has mainly focused on the design of high-affinity MOP ligands, the emergence of other novel avenues has begun to prove some clinical interest. Targeting other members of the opioid receptor family could be an attractive avenue, as most of the debilitating side effects associated with current analgesics are linked to MOP activation. Among these, DOP agonists have shown sustained analgesia; however, their ability to produce seizures has limited their clinical development [120]. However, further carefully designed studies to address why certain DOP agonists are seizurogenic could accelerate the development of novel DOP clinical candidates in the near future [120]. Some evidence has shown that G protein-biased DOP ligands are preferable. For instance, the selective biased DOP small molecule, PN6047, which relieves chronic pain without tolerance or seizures in rodents, recently completed a phase I clinical trial with encouraging results [121,122].

In contrast, selective KOP agonists were initially forgotten due to severe side effects such as sedation, dysphoria, and hallucination [123,124]. To date, no selective KOP agonists has been clinically approved for pain management, but preclinical studies have revealed in recent years that G protein activation is responsible for antinociceptive action, whereas β-arrestin recruitment has been linked to dysphoric effects [125,126,127]. The use of this strategy could enable the development of a KOP agonist with a safer profile. Interestingly, peripherally restricted κ-opioid receptor agonists have also been proposed as a way to avoid the deleterious central-mediated side effects of KOP activation while leading to effective management of visceral pain management [126,129]. For instance, CR665, a peripheral KOP agonist supported by Cara therapeutics, showed promising antinociceptive effects for visceral pain in a 2009 human proof-of-concept clinical study [130]. However, due to its pharmacokinetics properties CR665 have to be administered intravenously thus, slowing its clinical development.

Another alternative to classical opioids is the inhibition of opioid peptide scavenger receptors [128]. The rationale is that while endogenous opioid peptides such as endorphins, enkephalins, and dynorphins can modulate pain on their own, their action is negatively affected by scavenger receptors such as the atypical chemokine receptor 3 (ACKR3, previously known as CXCR7), reducing their availability to canonical opioid receptors [129,130]. Hence, competitive ligands of ACKR3, such as LIH383, could increase the availability of endogenous ligands to classical opioid receptors and enable extended analgesic action [128].

Given the complexity of the nociceptive transmission and development of chronic pain, it is unlikely that a single mechanism of action can provide sustained and effective pain relief. For instance, nociceptive transmission involves several endogenous systems that are modulated and fine-tuned by several receptors, hormones, and neuromodulators. To this end, multimodal therapies have been used as a means of approaching the treatment of chronic pain on a much broader spectrum [131,132]. The concurrent use of two or more drugs (polypharmacy) is common [133,134]. For this reason, a growing number of fixed-dose combinations (two medicines incorporated into a single formulation), such as oxycodone/ibuprofen or tramadol/acetaminophen, are being developed [135,136]. The advantage over polypharmacy lies in improving patient compliance by reducing the pill load. However, many drawbacks such as drug interactions and solubility incompatibility limit some of these combinations [140]. Hence, the development of a single entity that can incorporate both drugs has emerged with co-crystals, such as Seglentis (a co-crystal of the two enantiomers of tramadol and celecoxib), to resolve pharmacokinetic and formulation issues [138]. Interestingly, multiple single agents exerting pain-relieving action through a combination of mechanisms have recently been clinically approved. These include tapentadol (combining opioid and noradrenergic mechanisms) [142], tramadol (combining opioid and monoaminergic mechanisms) [143], buprenorphine, and cebranopadol (dual MOP/NOP actions) [141,142,143]. As a more selective approach, bifunctional compounds, comprising two opioid moieties or an opioid and a non-opioid pharmacophore, have been proposed as being of great interest [144,145,146]. However, to date, these compounds remain in the academic development stage, and none has yet been brought to market.

10. The Still Unknown Component for an Ideal Analgesic

Studies using knockout mice have revealed the basic components needed to make a highly desirable opioid analgesic, a selective G protein-biased MOP ligand. This type of molecule has been hypothesized to promote analgesia without major unwanted effects such as respiratory depression and tolerance. However, certain components are still missing. The discrepancies between studies highlight the gaps and challenges that remain when it comes to transposing in vitro bias to in vivo physiology (e.g., variation in stoichiometry between receptors and signaling components or between GRKs and β-arrestins, variable temporal differentiation of agonist signals in cells, location bias, and the involvement of intrinsic pharmacokinetic properties; for an extensive and comprehensive review, see Kenakin (2024) [51]). We need to keep in mind that as we move forward from in vitro to in vivo, we will need to take additional factors into account as interactions and interconnections between co-dependent systems increase [150]. Filling the translational gap between in vitro and in vivo may require radical changes to the process of developing biased molecules in order to refine the choice of molecules and to make better-informed decisions. The use of primary cells from animal models of diseases is often cited as an intermediate approach, but the use of more complex readouts, such as transcriptome analysis, might yield more relevant and structured data for the development of biased ligands [148,149]. This could help explain why some G protein-biased agonists with similar profiles display no rewarding effects and no dependence, whereas others have the same abuse liability as clinically used opioids.

Although oliceridine is the first prospectively designed MOP-biased agonist to receive clinical approval, it has yet to demonstrate clear superiority over standard opioid treatments in terms of safety and efficacy. Nevertheless, retrospective analyses of drugs known for biased signaling, such as buprenorphine and levorphanol, suggest that biased agonism and/or agonists with low intrinsic efficacy remain a promising approach to pursue in the quest for new and improved painkillers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, É.B.-O.; writing–original draft preparation, É.B. and É.B.-O.; writing–review and editing, É.B, R.L.B., T.E.H., P.S., and É.B.-O.; visualization, É.B. and É.B.-O.; supervision, T.E.H., P.S., and É.B-O.; project administration, P.S. and É.B.-O; funding acquisition, P.S. and É.B.-O. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR-IRSC), Foundation scheme grant number FDN-148413, and by the Université de Caen–Normandie “RECITAL International Partnership Laboratory” grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Code Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Press releases from Trevena and PharmNovo as well as minutes of FDA AADPAC meeting and “S

econd Cycle Review and Summary Basis for Approval” of oliceridine are available at

https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/j4wuv.

Acknowledgments

Illustrations of this article were created using Biorender.

Conflicts of Interest

Émile Breault, Rebecca L. Brouillette, Terence E. Hébert, Philippe Sarret, and Élie Besserer-Offroy declare that they have no conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this manuscript. Émile Breault is supported by scholarships from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQ-S). Rebecca L. Brouillette is the recipient of a CIHR doctoral scholarship. Terence E. Hébert holds the Canadian Pacific Chair in Biotechnology. Philippe Sarret is the recipient of a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Neurophysiopharmacology of Chronic Pain and is a member of the FRQ-S-funded Québec Pain Research Network. Élie Besserer-Offroy is the recipient of an Excellence Research Chair in Innovative Theranostics Approaches in Ovarian Cancers (THERANOVCA) funded by Région Normandie and co-funded by the European Union. The funders had no role in the design; writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the manuscript.

References

- Cohen SP, Vase L, Hooten WM. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet. 2021 May 29;397(10289):2082-97. [CrossRef]

- Volkow ND, Blanco C. The changing opioid crisis: development, challenges and opportunities. Mol Psychiatry. 2021 Jan;26(1):218-33. [CrossRef]

- Duarte DF. [Opium and opioids: a brief history.]. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2005 Feb;55(1):135-46.

- Santoro D, Bellinghieri G, Savica V. Development of the concept of pain in history. J Nephrol. 2011 May-Jun;24 Suppl 17:S133-6. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG, Williams KA, Day R, McLachlan AJ. Efficacy, Tolerability, and Dose-Dependent Effects of Opioid Analgesics for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jul 1;176(7):958-68.

- de Leon-Casasola OA. Opioids for chronic pain: new evidence, new strategies, safe prescribing. Am J Med. 2013 Mar;126(3 Suppl 1):S3-11.

- Kissin I. The development of new analgesics over the past 50 years: a lack of real breakthrough drugs. Anesth Analg. 2010 Mar 1;110(3):780-9. [CrossRef]

- WHO Expert Committee. The selection and use of essential medicines: report of the WHO Expert Committee, 2017 (including the 20th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and the 6th WHO Model List of essential Medicines for Children). WHO technical report series ; no 1006. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. p. 604.

- Shipton EA, Shipton EE, Shipton AJ. A Review of the Opioid Epidemic: What Do We Do About It? Pain Ther. 2018 Jun;7(1):23-36.

- Manchikanti L, Helm S, 2nd, Fellows B, Janata JW, Pampati V, Grider JS, et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician. 2012 Jul;15(3 Suppl):ES9-38.

- Webster L, Schmidt WK. Dilemma of Addiction and Respiratory Depression in the Treatment of Pain: A Prototypical Endomorphin as a New Approach. Pain Med. 2019 Jun 5. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Zhuang Y, DiBerto JF, Zhou XE, Schmitz GP, Yuan Q, et al. Structures of the entire human opioid receptor family. Cell. 2023 Jan 19;186(2):413-27 e17. [CrossRef]

- Matthes HW, Maldonado R, Simonin F, Valverde O, Slowe S, Kitchen I, et al. Loss of morphine-induced analgesia, reward effect and withdrawal symptoms in mice lacking the mu-opioid-receptor gene. Nature. 1996 Oct 31;383(6603):819-23.

- Hsia JA, Moss J, Hewlett EL, Vaughan M. ADP-ribosylation of adenylate cyclase by pertussis toxin. Effects on inhibitory agonist binding. J Biol Chem. 1984 Jan 25;259(2):1086-90. [CrossRef]

- Taussig R, Iniguez-Lluhi JA, Gilman AG. Inhibition of adenylyl cyclase by Gi alpha. Science. 1993 Jul 9;261(5118):218-21.

- Ippolito DL, Temkin PA, Rogalski SL, Chavkin C. N-terminal tyrosine residues within the potassium channel Kir3 modulate GTPase activity of Galphai. J Biol Chem. 2002 Sep 6;277(36):32692-6.

- Sadja R, Alagem N, Reuveny E. Gating of GIRK Channels. Neuron. 2003;39(1):9-12. [CrossRef]

- Díaz A, Flórez J, Pazos A, Hurlé MA. Opioid tolerance and supersensitivity induce regional changes in the autoradiographic density of dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channels in the rat central nervous system. Pain. 2000;86(3):227-35. [CrossRef]

- Diaz A, Ruiz F, Florez J, Pazos A, Hurle MA. Regulation of dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca++ channels during opioid tolerance and supersensitivity in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995 Sep;274(3):1538-44. [CrossRef]

- Wickman K, Clapham DE. Ion channel regulation by G proteins. Physiol Rev. 1995 Oct;75(4):865-85. [CrossRef]

- Dang VC, Christie MJ. Mechanisms of rapid opioid receptor desensitization, resensitization and tolerance in brain neurons. Br J Pharmacol. 2012 Mar;165(6):1704-16. [CrossRef]

- Groer CE, Schmid CL, Jaeger AM, Bohn LM. Agonist-directed interactions with specific beta-arrestins determine mu-opioid receptor trafficking, ubiquitination, and dephosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2011 Sep 9;286(36):31731-41.

- Melief EJ, Miyatake M, Bruchas MR, Chavkin C. Ligand-directed c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation disrupts opioid receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jun 22;107(25):11608-13. [CrossRef]

- Whistler JL, Chuang H-h, Chu P, Jan LY, von Zastrow M. Functional Dissociation of μ Opioid Receptor Signaling and Endocytosis. Neuron. 1999;23(4):737-46. [CrossRef]

- Gondin AB, Halls ML, Canals M, Briddon SJ. GRK Mediates mu-Opioid Receptor Plasma Membrane Reorganization. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:104.

- Raffa RB, Martinez RP, Connelly CD. G-protein antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotides and μ-opioid supraspinal antinociception. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1994;258(1-2):R5-R7. [CrossRef]

- Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Peppel K, Caron MG, Lin FT. Enhanced morphine analgesia in mice lacking beta-arrestin 2. Science. 1999 Dec 24;286(5449):2495-8.

- Raehal KM, Walker JK, Bohn LM. Morphine Side Effects in β -Arrestin 2 Knockout Mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005 Sep;314(3):1195-201. [CrossRef]

- Bohn LM, Gainetdinov RR, Lin FT, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Mu-opioid receptor desensitization by beta-arrestin-2 determines morphine tolerance but not dependence. Nature. 2000 Dec 7;408(6813):720-3.

- Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Kieffer BL. Opioid receptor genes inactivated in mice: the highlights. Neuropeptides. 2002 Apr-Jun;36(2-3):62-71. [CrossRef]

- Yang CH, Huang HW, Chen KH, Chen YS, Sheen-Chen SM, Lin CR. Antinociceptive potentiation and attenuation of tolerance by intrathecal beta-arrestin 2 small interfering RNA in rats. Br J Anaesth. 2011 Nov;107(5):774-81.

- Kliewer A, Schmiedel F, Sianati S, Bailey A, Bateman JT, Levitt ES, et al. Phosphorylation-deficient G-protein-biased mu-opioid receptors improve analgesia and diminish tolerance but worsen opioid side effects. Nat Commun. 2019 Jan 21;10(1):367.

- Bull FA, Baptista-Hon DT, Sneddon C, Wright L, Walwyn W, Hales TG. Src Kinase Inhibition Attenuates Morphine Tolerance without Affecting Reinforcement or Psychomotor Stimulation. Anesthesiology. 2017 Nov;127(5):878-89. [CrossRef]

- Kliewer A, Gillis A, Hill R, Schmiedel F, Bailey C, Kelly E, et al. Morphine-induced respiratory depression is independent of beta-arrestin2 signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 2020 Jul;177(13):2923-31.

- Chen YJ, Oldfield S, Butcher AJ, Tobin AB, Saxena K, Gurevich VV, et al. Identification of phosphorylation sites in the COOH-terminal tail of the mu-opioid receptor. J Neurochem. 2013 Jan;124(2):189-99.

- Miess E, Gondin AB, Yousuf A, Steinborn R, Mosslein N, Yang Y, et al. Multisite phosphorylation is required for sustained interaction with GRKs and arrestins during rapid mu-opioid receptor desensitization. Sci Signal. 2018 Jul 17;11(539).

- Bachmutsky I, Wei XP, Durand A, Yackle K. B-arrestin 2 germline knockout does not attenuate opioid respiratory depression. Elife. 2021 May 18;10.

- Gregory KJ. Commentary on "Morphine-induced respiratory depression is independent of beta-arrestin2 signalling". Br J Pharmacol. 2020 Jul;177(13):2904-5.

- Lam H, Maga M, Pradhan A, Evans CJ, Maidment NT, Hales TG, et al. Analgesic tone conferred by constitutively active mu opioid receptors in mice lacking beta-arrestin 2. Mol Pain. 2011 Apr 12;7:24.

- Stone LS, Molliver DC. In search of analgesia: emerging roles of GPCRs in pain. Mol Interv. 2009 Oct;9(5):234-51.

- Rajagopal S, Rajagopal K, Lefkowitz RJ. Teaching old receptors new tricks: biasing seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010 May;9(5):373-86. [CrossRef]

- Audet M, Bouvier M. Restructuring G-protein- coupled receptor activation. Cell. 2012 Sep 28;151(1):14-23. [CrossRef]

- Kenakin T. Functional selectivity and biased receptor signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011 Feb;336(2):296-302. [CrossRef]

- Wootten D, Christopoulos A, Marti-Solano M, Babu MM, Sexton PM. Mechanisms of signalling and biased agonism in G protein-coupled receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018 Oct;19(10):638-53. [CrossRef]

- van der Westhuizen ET, Breton B, Christopoulos A, Bouvier M. Quantification of ligand bias for clinically relevant beta2-adrenergic receptor ligands: implications for drug taxonomy. Mol Pharmacol. 2014 Mar;85(3):492-509.

- Kenakin T, Christopoulos A. Signalling bias in new drug discovery: detection, quantification and therapeutic impact. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013 Mar;12(3):205-16. [CrossRef]

- Besserer-Offroy E, Sarret P. Sending out Biased Signals: an Appropriate Proposition for Pain? Douleur et Analgésie. 2019;32(2):108-10.

- Michel MC, Charlton SJ. Biased Agonism in Drug Discovery-Is It Too Soon to Choose a Path? Mol Pharmacol. 2018 Apr;93(4):259-65.

- Urs NM, Gee SM, Pack TF, McCorvy JD, Evron T, Snyder JC, et al. Distinct cortical and striatal actions of a beta-arrestin-biased dopamine D2 receptor ligand reveal unique antipsychotic-like properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Dec 13;113(50):E8178-E86.

- Schattauer SS, Kuhar JR, Song A, Chavkin C. Nalfurafine is a G-protein biased agonist having significantly greater bias at the human than rodent form of the kappa opioid receptor. Cell Signal. 2017 Apr;32:59-65.

- Kenakin T. Bias translation: The final frontier? Br J Pharmacol. 2024 May;181(9):1345-60.

- Kenakin T. Know your molecule: pharmacological characterization of drug candidates to enhance efficacy and reduce late-stage attrition. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2024 Aug;23(8):626-44. [CrossRef]

- Keith DE, Murray SR, Zaki PA, Chu PC, Lissin DV, Kang L, et al. Morphine activates opioid receptors without causing their rapid internalization. J Biol Chem. 1996 Aug 9;271(32):19021-4.

- Ehrlich AT, Kieffer BL, Darcq E. Current strategies toward safer mu opioid receptor drugs for pain management. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2019 Feb 25:1-12. [CrossRef]

- McPherson J, Rivero G, Baptist M, Llorente J, Al-Sabah S, Krasel C, et al. mu-opioid receptors: correlation of agonist efficacy for signalling with ability to activate internalization. Mol Pharmacol. 2010 Oct;78(4):756-66.

- Schmid CL, Kennedy NM, Ross NC, Lovell KM, Yue Z, Morgenweck J, et al. Bias Factor and Therapeutic Window Correlate to Predict Safer Opioid Analgesics. Cell. 2017 Nov 16;171(5):1165-75 e13. [CrossRef]

- Butler S. Buprenorphine-Clinically useful but often misunderstood. Scand J Pain. 2013 Jul 1;4(3):148-52. [CrossRef]

- Lutfy K, Cowan A. Buprenorphine: a unique drug with complex pharmacology. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2004 Oct;2(4):395-402. [CrossRef]

- Davis MP, Pasternak G, Behm B. Treating Chronic Pain: An Overview of Clinical Studies Centered on the Buprenorphine Option. Drugs. 2018 Aug;78(12):1211-28. [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich AT, Darcq E. Recommending buprenorphine for pain management. Pain Manag. 2019 Jan 1;9(1):13-6. [CrossRef]

- Vlok R, An GH, Binks M, Melhuish T, White L. Sublingual buprenorphine versus intravenous or intramuscular morphine in acute pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Am J Emerg Med. 2019 Mar;37(3):381-6.

- Gudin J, Fudin J, Nalamachu S. Levorphanol use: past, present and future. Postgrad Med. 2016 Jan;128(1):46-53. [CrossRef]

- Prommer E. Levorphanol: the forgotten opioid. Support Care Cancer. 2007 Mar;15(3):259-64. [CrossRef]

- Prommer E. Levorphanol: revisiting an underutilized analgesic. Palliat Care. 2014;8:7-10. [CrossRef]

- Le Rouzic V, Narayan A, Hunkle A, Marrone GF, Lu Z, Majumdar S, et al. Pharmacological Characterization of Levorphanol, a G-Protein Biased Opioid Analgesic. Anesth Analg. 2019 Feb;128(2):365-73. [CrossRef]

- Nair AS, Upputuri O, Mantha SSP, Rayani BK. Levorphanol: Rewinding an Old, Bygone Multimodal Opioid Analgesic! Indian J Palliat Care. 2019 Jul-Sep;25(3):483-4.

- Pham TC, Fudin J, Raffa RB. Is levorphanol a better option than methadone? Pain Med. 2015 Sep;16(9):1673-9.

- Chen X-T, Pitis P, Liu G, Yuan C, Gotchev D, Cowan CL, et al. Structure–Activity Relationships and Discovery of a G Protein Biased μ Opioid Receptor Ligand, [(3-Methoxythiophen-2-yl)methyl]({2-[(9R)-9-(pyridin-2-yl)-6-oxaspiro-[4.5]decan-9-yl]ethyl})amine (TRV130), for the Treatment of Acute Severe Pain. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;56(20):8019-31.

- DeWire SM, Yamashita DS, Rominger DH, Liu G, Cowan CL, Graczyk TM, et al. A G protein-biased ligand at the mu-opioid receptor is potently analgesic with reduced gastrointestinal and respiratory dysfunction compared with morphine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013 Mar;344(3):708-17.

- Trevena Inc. Trevena Announces Submission of New Drug Application to U.S. FDA for Oliceridine Injection. 2017 [cited 2020-03-24]; Available from: https://www.trevena.com/investors/press-releases/detail/127/trevena-announces-submission-of-new-drug-application-to.

- Trevena Inc. Trevena Announces FDA Acceptance for Review of New Drug Application for Oliceridine Injection. 2018 [cited 2020-03-24]; Available from: https://www.trevena.com/investors/press-releases/detail/129/trevena-announces-fda-acceptance-for-review-of-new-drug.

- Trevena Inc. Trevena Announces Oliceridine FDA Advisory Committee Meeting Outcome. 2018 [cited 2020-03-24]; Available from: https://www.trevena.com/investors/press-releases/detail/154/trevena-announces-oliceridine-fda-advisory-committee.

- FDA AADPAC. Transcript for the October 11, 2018 Meeting of the Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee (AADPAC). 2018 [cited 2020-03-24]; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/AnestheticAndAnalgesicDrugProductsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM629602.pdf.

- Trevena Inc. Trevena Announces Receipt of Type A Meeting Minutes and Provides Regulatory Update for Oliceridine. 2019 [cited 2020-03-14]; Available from: https://www.trevena.com/investors/press-releases/detail/160/trevena-announces-receipt-of-type-a-meeting-minutes-and.

- Trevena Inc. Trevena Announces Initiation of Healthy Volunteer Study for Oliceridine. 2019 [cited 2020-05-12]; Available from: https://www.trevena.com/investors/press-releases/detail/5/trevena-announces-initiation-of-healthy-volunteer-study-for.

- Nafziger AN, Arscott KA, Cochrane K, Skobieranda F, Burt DA, Fossler MJ. The Influence of Renal or Hepatic Impairment on the Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Tolerability of Oliceridine. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2019 Nov 7. [CrossRef]

- Trevena Inc. Trevena Resubmits New Drug Application for Oliceridine. 2020 [cited 2020-06-16]; Available from: https://www.trevena.com/investors/press-releases/detail/224/trevena-resubmits-new-drug-application-for-oliceridine.

- Gan TJ, Wase L. Oliceridine, a G protein-selective ligand at the mu-opioid receptor, for the management of moderate to severe acute pain. Drugs Today (Barc). 2020 Apr;56(4):269-86. [CrossRef]

- Trevena Inc. Trevena Announces FDA Approval of OLINVYK™ (oliceridine) injection. 2020 [cited 2024-08-18]; Available from: https://www.trevena.com/investors/press-releases/detail/234/trevena-announces-fda-approval-of-olinvyk-oliceridine-injection.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA Approves New Opioid for Intravenous Use in Hospitals, Other Controlled Clinical Settings. 2020 [cited; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-opioid-intravenous-use-hospitals-other-controlled-clinical-settings.

- Shah A, Shah R, Fahim G, Brust-Sisti LA. A Dive Into Oliceridine and Its Novel Mechanism of Action. Cureus. 2021 Oct;13(10):e19076. [CrossRef]

- Azzam AAH, Lambert DG. Preclinical discovery and development of oliceridine (Olinvyk(R)) for the treatment of post-operative pain. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2022 Mar;17(3):215-23.

- Trevena Inc. Trevena, Inc. Announces DEA Scheduling of OLINVYK™ (oliceridine) injection. 2020 [cited; Available from: https://www.trevena.com/investors/press-releases/detail/244/trevena-inc-announces-dea-scheduling-of-olinvyk-oliceridine-injection.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Second Cycle Review And Summary Basis for Approval - Oliceridine injection (NDA 210-730). 2020 2020-08-07 [cited 210730Orig1s000 ]; Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2020/210730Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf.

- Trevena Inc. Trevena Announces Approval of OLINVYK in China. 2023 [cited 2024-08-18]; Available from: https://www.trevena.com/investors/press-releases/detail/320/trevena-announces-approval-of-olinvyk-in-china.

- Ayad S, Demitrack MA, Burt DA, Michalsky C, Wase L, Fossler MJ, et al. Evaluating the Incidence of Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression Associated with Oliceridine and Morphine as Measured by the Frequency and Average Cumulative Duration of Dosing Interruption in Patients Treated for Acute Postoperative Pain. Clin Drug Investig. 2020 Aug;40(8):755-64. [CrossRef]

- Brzezinski M, Hammer GB, Candiotti KA, Bergese SD, Pan PH, Bourne MH, et al. Low Incidence of Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression Observed with Oliceridine Regardless of Age or Body Mass Index: Exploratory Analysis from a Phase 3 Open-Label Trial in Postsurgical Pain. Pain Ther. 2021 Jun;10(1):457-73. [CrossRef]

- Hammer GB, Khanna AK, Michalsky C, Wase L, Demitrack MA, Little R, et al. Oliceridine Exhibits Improved Tolerability Compared to Morphine at Equianalgesic Conditions: Exploratory Analysis from Two Phase 3 Randomized Placebo and Active Controlled Trials. Pain Ther. 2021 Dec;10(2):1343-53. [CrossRef]

- Beard TL, Michalsky C, Candiotti KA, Rider P, Wase L, Habib AS, et al. Oliceridine is Associated with Reduced Risk of Vomiting and Need for Rescue Antiemetics Compared to Morphine: Exploratory Analysis from Two Phase 3 Randomized Placebo and Active Controlled Trials. Pain Ther. 2021 Jun;10(1):401-13. [CrossRef]

- Hill DM, DeBoer E. State and Future Science of Opioids and Potential of Biased-ligand Technology in the Management of Acute Pain After Burn Injury. J Burn Care Res. 2023 May 2;44(3):524-34. [CrossRef]

- Manglik A, Lin H, Aryal DK, McCorvy JD, Dengler D, Corder G, et al. Structure-based discovery of opioid analgesics with reduced side effects. Nature. 2016 Sep 8;537(7619):185-90. [CrossRef]

- Emery MA, Eitan S. Members of the same pharmacological family are not alike: Different opioids, different consequences, hope for the opioid crisis? Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2019;92:428-49.

- Kudla L, Bugno R, Skupio U, Wiktorowska L, Solecki W, Wojtas A, et al. Functional characterization of a novel opioid, PZM21, and its influence on behavioural responses to morphine. Br J Pharmacol. 2019 Jul 26.

- Hill R, Disney A, Conibear A, Sutcliffe K, Dewey W, Husbands S, et al. The novel mu-opioid receptor agonist PZM21 depresses respiration and induces tolerance to antinociception. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 Jul;175(13):2653-61.

- Grim TW, Acevedo-Canabal A, Bohn LM. Toward Directing Opioid Receptor Signaling to Refine Opioid Therapeutics. Biol Psychiatry. 2020 Jan 1;87(1):15-21. [CrossRef]

- de Waal PW, Shi J, You E, Wang X, Melcher K, Jiang Y, et al. Molecular mechanisms of fentanyl mediated beta-arrestin biased signaling. PLoS Comput Biol. 2020 Apr;16(4):e1007394.

- Ramos-Gonzalez N, Groom S, Sutcliffe KJ, Bancroft S, Bailey CP, Sessions RB, et al. Carfentanil is a beta-arrestin-biased agonist at the mu opioid receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2023 Sep;180(18):2341-60.

- Huang W, Manglik A, Venkatakrishnan AJ, Laeremans T, Feinberg EN, Sanborn AL, et al. Structural insights into micro-opioid receptor activation. Nature. 2015 Aug 20;524(7565):315-21.

- Zhuang Y, Wang Y, He B, He X, Zhou XE, Guo S, et al. Molecular recognition of morphine and fentanyl by the human mu-opioid receptor. Cell. 2022 Nov 10;185(23):4361-75 e19.

- Kelly E, Conibear A, Henderson G. Biased Agonism: Lessons from Studies of Opioid Receptor Agonists. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2023 Jan 20;63:491-515. [CrossRef]

- Kise R, Inoue A. GPCR signaling bias: an emerging framework for opioid drug development. J Biochem. 2024 Mar 25;175(4):367-76. [CrossRef]

- Gillis A, Gondin AB, Kliewer A, Sanchez J, Lim HD, Alamein C, et al. Low intrinsic efficacy for G protein activation can explain the improved side effect profiles of new opioid agonists. Sci Signal. 2020 Mar 31;13(625). [CrossRef]

- Stoeber M, Jullie D, Lobingier BT, Laeremans T, Steyaert J, Schiller PW, et al. A Genetically Encoded Biosensor Reveals Location Bias of Opioid Drug Action. Neuron. 2018 Jun 6;98(5):963-76 e5. [CrossRef]

- Wan Q, Okashah N, Inoue A, Nehme R, Carpenter B, Tate CG, et al. Mini G protein probes for active G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in live cells. J Biol Chem. 2018 May 11;293(19):7466-73. [CrossRef]

- Stahl EL, Bohn LM. Low Intrinsic Efficacy Alone Cannot Explain the Improved Side Effect Profiles of New Opioid Agonists. Biochemistry. 2022 Sep 20;61(18):1923-35. [CrossRef]

- Clark DJ, Schumacher MA. America's Opioid Epidemic: Supply and Demand Considerations. Anesth Analg. 2017 Nov;125(5):1667-74. [CrossRef]

- Killeen N, Lakes R, Webster M, Killoran S, McNamara S, Kavanagh P, et al. The emergence of nitazenes on the Irish heroin market and national preparation for possible future outbreaks. Addiction. 2024 Sep;119(9):1657-8. [CrossRef]

- Kozell LB, Eshleman AJ, Wolfrum KM, Swanson TL, Bloom SH, Benware S, et al. Pharmacologic Characterization of Substituted Nitazenes at mu, kappa, and Delta Opioid Receptors Suggests High Potential for Toxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2024 Apr 18;389(2):219-28.

- Bendjilali-Sabiani JJ, Eiden C, Lestienne M, Cherki S, Gautre D, Van den Broek T, et al. Isotonitazene, a synthetic opioid from an emerging family: The nitazenes. Therapie. 2024 May 28. [CrossRef]

- Amaducci A, Aldy K, Campleman SL, Li S, Meyn A, Abston S, et al. Naloxone Use in Novel Potent Opioid and Fentanyl Overdoses in Emergency Department Patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Aug 1;6(8):e2331264. [CrossRef]

- Hauser W, Schug S, Furlan AD. The opioid epidemic and national guidelines for opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain: a perspective from different continents. Pain Rep. 2017 May;2(3):e599. [CrossRef]

- Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Dec 30;65(50-51):1445-52.

- Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, Buckley DN, Wang L, Couban RJ, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ. 2017 May 8;189(18):E659-E66. [CrossRef]

- Bohn LM, Gainetdinov RR, Sotnikova TD, Medvedev IO, Lefkowitz RJ, Dykstra LA, et al. Enhanced Rewarding Properties of Morphine, but not Cocaine, in βarrestin-2 Knock-Out Mice. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(32):10265-73. [CrossRef]

- Zamarripa CA, Edwards SR, Qureshi HN, Yi JN, Blough BE, Freeman KB. The G-protein biased mu-opioid agonist, TRV130, produces reinforcing and antinociceptive effects that are comparable to oxycodone in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018 Nov 1;192:158-62.

- Altarifi AA, David B, Muchhala KH, Blough BE, Akbarali H, Negus SS. Effects of acute and repeated treatment with the biased mu opioid receptor agonist TRV130 (oliceridine) on measures of antinociception, gastrointestinal function, and abuse liability in rodents. J Psychopharmacol. 2017 Jun;31(6):730-9. [CrossRef]

- Liang DY, Li WW, Nwaneshiudu C, Irvine KA, Clark JD. Pharmacological Characters of Oliceridine, a mu-Opioid Receptor G-Protein[FIGURE DASH]Biased Ligand in Mice. Anesth Analg. 2018 Jul 21.

- Soergel DG, Subach RA, Burnham N, Lark MW, James IE, Sadler BM, et al. Biased agonism of the mu-opioid receptor by TRV130 increases analgesia and reduces on-target adverse effects versus morphine: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy volunteers. Pain. 2014 Sep;155(9):1829-35.

- Grim TW, Schmid CL, Stahl EL, Pantouli F, Ho JH, Acevedo-Canabal A, et al. A G protein signaling-biased agonist at the mu-opioid receptor reverses morphine tolerance while preventing morphine withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020 Jan;45(2):416-25.

- Quirion B, Bergeron F, Blais V, Gendron L. The Delta-Opioid Receptor; a Target for the Treatment of Pain. Front Mol Neurosci. 2020;13:52. [CrossRef]

- Blaine AT, van Rijn RM. Receptor expression and signaling properties in the brain, and structural ligand motifs that contribute to delta opioid receptor agonist-induced seizures. Neuropharmacology. 2023 Jul 1;232:109526.

- Conibear AE, Asghar J, Hill R, Henderson G, Borbely E, Tekus V, et al. A Novel G Protein-Biased Agonist at the delta Opioid Receptor with Analgesic Efficacy in Models of Chronic Pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2020 Feb;372(2):224-36.

- PharmNovo A. PharmNovo announces positive Phase I results for neuropathic pain management drug PN6047. 2024 [cited 2024-08-18]; Available from: https://www.mediconvillage.se/pharmnovo-announces-positive-phase-i-results-for-neuropathic-pain-management-drug-pn6047/.

- Cayir S, Zhornitsky S, Barzegary A, Sotomayor-Carreno E, Sarfo-Ansah W, Funaro MC, et al. A review of the kappa opioid receptor system in opioid use. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2024 Jul;162:105713. [CrossRef]

- Santino F, Gentilucci L. Design of kappa-Opioid Receptor Agonists for the Development of Potential Treatments of Pain with Reduced Side Effects. Molecules. 2023 Jan 1;28(1).

- Dalefield ML, Scouller B, Bibi R, Kivell BM. The Kappa Opioid Receptor: A Promising Therapeutic Target for Multiple Pathologies. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:837671. [CrossRef]

- Mores KL, Cummins BR, Cassell RJ, van Rijn RM. A Review of the Therapeutic Potential of Recently Developed G Protein-Biased Kappa Agonists. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:407. [CrossRef]

- Valentino RJ, Volkow ND. Untangling the complexity of opioid receptor function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018 Dec;43(13):2514-20. [CrossRef]

- Cahill CM, Lueptow L, Kim H, Shusharla R, Bishop A, Evans CJ. Kappa Opioid Signaling at the Crossroads of Chronic Pain and Opioid Addiction. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2022;271:315-50.

- Arendt-Nielsen L, Olesen AE, Staahl C, Menzaghi F, Kell S, Wong GY, et al. Analgesic efficacy of peripheral kappa-opioid receptor agonist CR665 compared to oxycodone in a multi-modal, multi-tissue experimental human pain model: selective effect on visceral pain. Anesthesiology. 2009 Sep;111(3):616-24.

- Meyrath M, Szpakowska M, Zeiner J, Massotte L, Merz MP, Benkel T, et al. The atypical chemokine receptor ACKR3/CXCR7 is a broad-spectrum scavenger for opioid peptides. Nat Commun. 2020 Jun 19;11(1):3033.

- Gach-Janczak K, Biernat M, Kuczer M, Adamska-Bartlomiejczyk A, Kluczyk A. Analgesic Peptides: From Natural Diversity to Rational Design. Molecules. 2024 Mar 29;29(7). [CrossRef]

- Palmer CB, Meyrath M, Canals M, Kostenis E, Chevigne A, Szpakowska M. Atypical opioid receptors: unconventional biology and therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol Ther. 2022 May;233:108014. [CrossRef]

- O'Neill A, Lirk P. Multimodal Analgesia. Anesthesiol Clin. 2022 Sep;40(3):455-68.

- Young A, Buvanendran A. Recent advances in multimodal analgesia. Anesthesiol Clin. 2012 Mar;30(1):91-100. [CrossRef]

- Giummarra MJ, Gibson SJ, Allen AR, Pichler AS, Arnold CA. Polypharmacy and chronic pain: harm exposure is not all about the opioids. Pain Med. 2015 Mar;16(3):472-9. [CrossRef]

- Arumugam S, Lau CS, Chamberlain RS. Use of preoperative gabapentin significantly reduces postoperative opioid consumption: a meta-analysis. J Pain Res. 2016;9:631-40. [CrossRef]

- Pergolizzi JV, Jr., van de Laar M, Langford R, Mellinghoff HU, Merchante IM, Nalamachu S, et al. Tramadol/paracetamol fixed-dose combination in the treatment of moderate to severe pain. J Pain Res. 2012;5:327-46. [CrossRef]

- Pergolizzi J, Varrassi G, LeQuang JAK, Breve F, Magnusson P. Fixed Dose Versus Loose Dose: Analgesic Combinations. Cureus. 2023 Jan;15(1):e33320. [CrossRef]

- Frantz S. The trouble with making combination drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006 Nov;5(11):881-2.

- Gascon N, Almansa C, Merlos M, Miguel Vela J, Encina G, Morte A, et al. Co-crystal of tramadol-celecoxib: preclinical and clinical evaluation of a novel analgesic. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019 May;28(5):399-409. [CrossRef]

- Caputi FF, Nicora M, Simeone R, Candeletti S, Romualdi P. Tapentadol: an analgesic that differs from classic opioids due to its noradrenergic mechanism of action. Minerva Med. 2019 Feb;110(1):62-78. [CrossRef]

- Barakat A. Revisiting Tramadol: A Multi-Modal Agent for Pain Management. CNS Drugs. 2019 May;33(5):481-501. [CrossRef]

- Cannella N, Lunerti V, Shen Q, Li H, Benvenuti F, Soverchia L, et al. Cebranopadol, a novel long-acting opioid agonist with low abuse liability, to treat opioid use disorder: Preclinical evidence of efficacy. Neuropharmacology. 2024 Oct 1;257:110048. [CrossRef]

- Kiguchi N, Ding H, Ko MC. Therapeutic potentials of NOP and MOP receptor coactivation for the treatment of pain and opioid abuse. J Neurosci Res. 2022 Jan;100(1):191-202. [CrossRef]

- Sanam M, Ashraf S, Saeed M, Khalid A, Abdalla AN, Qureshi U, et al. Cebranopadol: An Assessment for Its Biased Activation Potential at the Mu Opioid Receptor by DFT, Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamic Simulation Studies. ChemistrySelect. 2023;8(37). [CrossRef]

- Kleczkowska P, Lipkowski AW, Tourwe D, Ballet S. Hybrid opioid/non-opioid ligands in pain research. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(42):7435-50. [CrossRef]

- Breault E, Desgagne M, Neve J, Cote J, Barlow TMA, Ballet S, et al. Multitarget ligands that comprise opioid/nonopioid pharmacophores for pain management: Current state of the science. Pharmacol Res. 2024 Nov;209:107408. [CrossRef]

- Smith MT, Kong D, Kuo A, Imam MZ, Williams CM. Multitargeted Opioid Ligand Discovery as a Strategy to Retain Analgesia and Reduce Opioid-Related Adverse Effects. J Med Chem. 2023 Mar 23;66(6):3746-84. [CrossRef]

- Kenakin T. Biased Receptor Signaling in Drug Discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2019 Apr;71(2):267-315. [CrossRef]

- Luttrell LM, Maudsley S, Gesty-Palmer D. Translating in vitro ligand bias into in vivo efficacy. Cell Signal. 2018 Jan;41:46-55. [CrossRef]

- Walker CS, Sundrum T, Hay DL. PACAP receptor pharmacology and agonist bias: analysis in primary neurons and glia from the trigeminal ganglia and transfected cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2014 Mar;171(6):1521-33. [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich AT, Semache M, Gross F, Da Fonte DF, Runtz L, Colley C, et al. Biased Signaling of the Mu Opioid Receptor Revealed in Native Neurons. iScience. 2019 Apr 26;14:47-57. [CrossRef]

- Rivero G, Llorente J, McPherson J, Cooke A, Mundell SJ, McArdle CA, et al. Endomorphin-2: a biased agonist at the mu-opioid receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2012 Aug;82(2):178-88.

- Kelly E. Efficacy and ligand bias at the mu-opioid receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2013 Aug;169(7):1430-46.

- Pedersen MF, Wrobel TM, Marcher-Rorsted E, Pedersen DS, Moller TC, Gabriele F, et al. Biased agonism of clinically approved mu-opioid receptor agonists and TRV130 is not controlled by binding and signaling kinetics. Neuropharmacology. 2019 Jul 24:107718.

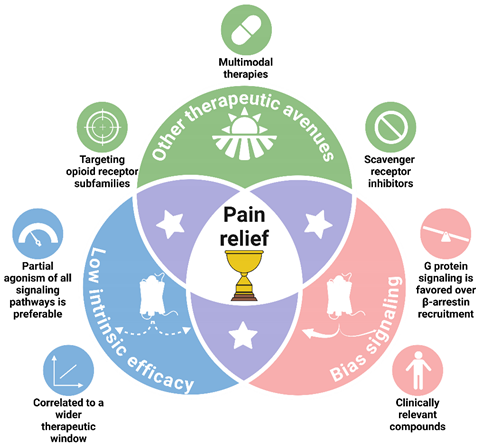

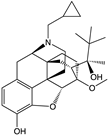

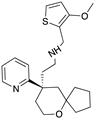

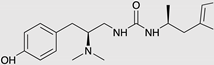

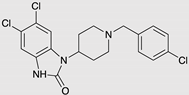

Figure 1.

µ-opioid receptor signaling. Upon activation of the µ-opioid receptor (MOP), the heterotrimeric G-protein dissociates into active Ga and Gbg subunits. The Gαi subunit inhibits adenylyl cyclase, thereby decreasing intracellular cAMP levels. The Gβγ dimer activates inwardly rectifying potassium channels (Kir), promoting K+ efflux out of the cell, and inhibits voltage-gated Ca++ channels, slowing down the entry of Ca++ into the cytosol, resulting in cell hyperpolarization and reduced neuronal excitability. The C-terminal tail of the opioid receptor is phosphorylated by G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRK) 2 and 3, and β-arrestins are then recruited to MOP, leading to receptor desensitization and internalization. β-arrestins also serve as scaffolding proteins for the activation of secondary signaling cascades, such as the MAP kinases ERK1/2 and JNK.

Figure 1.

µ-opioid receptor signaling. Upon activation of the µ-opioid receptor (MOP), the heterotrimeric G-protein dissociates into active Ga and Gbg subunits. The Gαi subunit inhibits adenylyl cyclase, thereby decreasing intracellular cAMP levels. The Gβγ dimer activates inwardly rectifying potassium channels (Kir), promoting K+ efflux out of the cell, and inhibits voltage-gated Ca++ channels, slowing down the entry of Ca++ into the cytosol, resulting in cell hyperpolarization and reduced neuronal excitability. The C-terminal tail of the opioid receptor is phosphorylated by G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRK) 2 and 3, and β-arrestins are then recruited to MOP, leading to receptor desensitization and internalization. β-arrestins also serve as scaffolding proteins for the activation of secondary signaling cascades, such as the MAP kinases ERK1/2 and JNK.

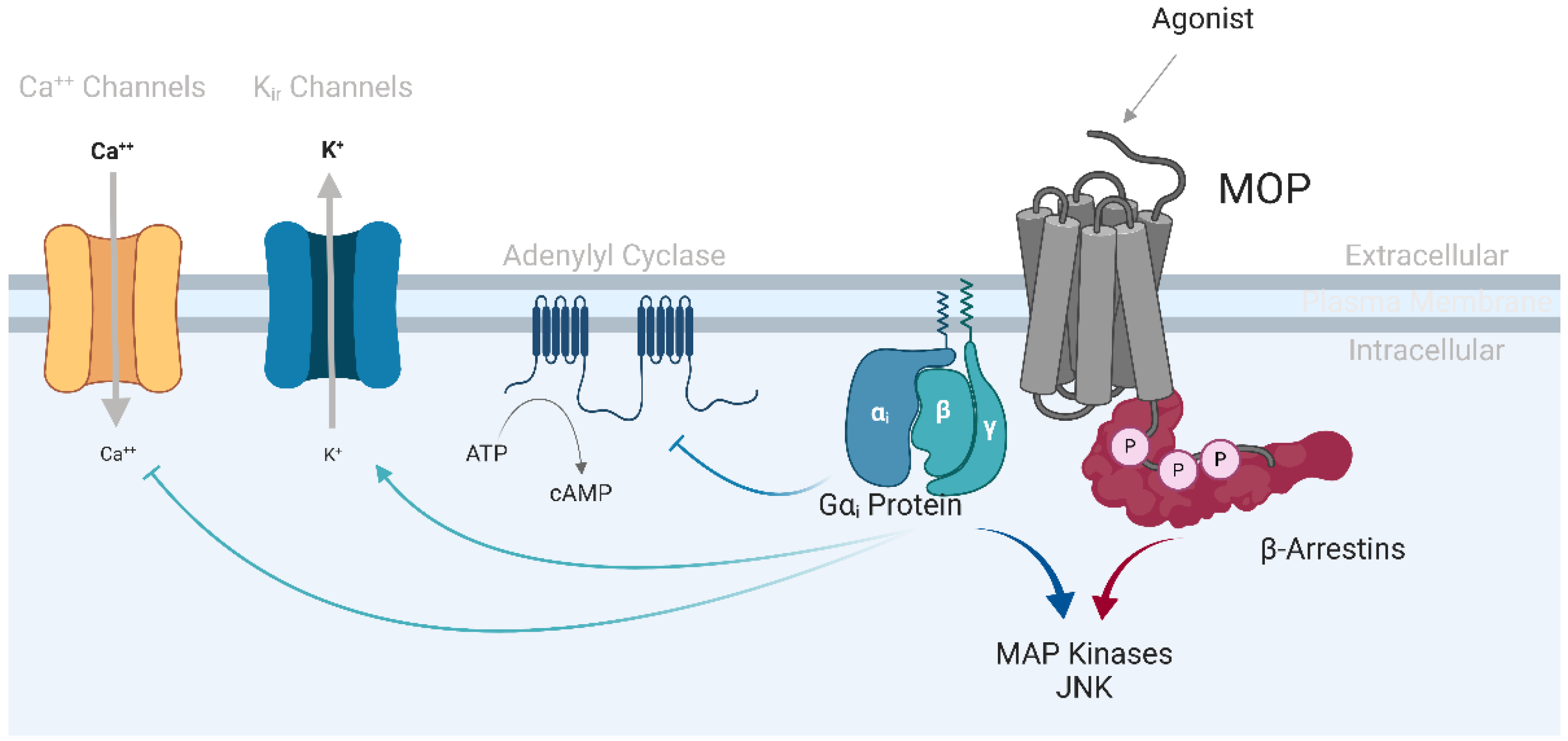

Figure 2.

The concept of biased signaling. (A) A balanced ligand triggers activation of all signaling proteins coupled to a given GPCR (Pathways A and B). (B-C) Biased agonists, on the other hand, activate only a subset of the receptor’s signaling repertoire. (B) A pathway A-biased ligand favors the recruitment of pathway A signaling partners over the activation of pathway B proteins. (C) Similarly, a biased ligand favoring pathway B triggers activation of the pathway B signaling cascade rather than recruitment of pathway A proteins.

Figure 2.

The concept of biased signaling. (A) A balanced ligand triggers activation of all signaling proteins coupled to a given GPCR (Pathways A and B). (B-C) Biased agonists, on the other hand, activate only a subset of the receptor’s signaling repertoire. (B) A pathway A-biased ligand favors the recruitment of pathway A signaling partners over the activation of pathway B proteins. (C) Similarly, a biased ligand favoring pathway B triggers activation of the pathway B signaling cascade rather than recruitment of pathway A proteins.

Figure 3.

Biased agonism at the µ-opioid receptor. MOP-induced Gαi activation is responsible for the antinociceptive and analgesic effects of µ-agonists, while unwanted effects are, in part, related to β-arrestin 2 recruitment following MOP activation. Consequently, MOP ligands favoring β-arrestin 2 recruitment over G protein activation, such as fentanyl, produce more undesirable effects than G protein-favoring ligands, such as PZM21 or TRV130. These effects include tolerance and may include respiratory suppression. G protein-biased agonists are of greater therapeutic interest due to their increased analgesic profile, but they can also lead to respiratory depression.

Figure 3.

Biased agonism at the µ-opioid receptor. MOP-induced Gαi activation is responsible for the antinociceptive and analgesic effects of µ-agonists, while unwanted effects are, in part, related to β-arrestin 2 recruitment following MOP activation. Consequently, MOP ligands favoring β-arrestin 2 recruitment over G protein activation, such as fentanyl, produce more undesirable effects than G protein-favoring ligands, such as PZM21 or TRV130. These effects include tolerance and may include respiratory suppression. G protein-biased agonists are of greater therapeutic interest due to their increased analgesic profile, but they can also lead to respiratory depression.

Figure 4.