1. Introduction

The garment processing industry, despite witnessing widespread adoption of robotics across various sectors, has been slow to embrace this technological revolution. This reluctance can be attributed primarily to the inherent challenges posed by the highly deformable nature of garments, which frequently assume unpredictable shapes during processing, making it difficult for robots to comprehend, generalize, and respond effectively. While some research endeavors [

1,

2] have ventured into the domain of robotic garment handling and manipulation of deformable objects, they are often limited in scope, addressing specific objects and operations within controlled environments. Consequently, there exists a pressing need for a versatile garment-handling robot capable of accommodating diverse garment types and adapting to varied working conditions, necessitating the development of a specialized vision-based detection model.

Existing literature [

3,

4,

5,

6] has explored vision-based garment handling robots. For instance, [

3] employs an edge detection-based method, which detects wrinkles represented by curvilinear structures and evaluate graspability along the line. The robot will grasp one point and lift one garment in the air, then perform classification and estimate a second point using a trained active random forest to open the garment. However, this second-point-grasping procedure may repeat several times until a garment is fully open, which is time-consuming for an industrial setup. [

4] utilizes a classical segmentation-based approach, which segments garments by pixel appearance and then selects the highest point from a segment using stereo disparity. However, this vision model suffers the same problem as [

3] since the segments lack semantic meanings and the grasping point is random on the garment. Moreover, it is constrained to a strict overhead view with no other objects in the view. [

5,

6] on the other hand, utilizes a learning-based approach, which uses an encoder-decoder network trained on human labeled dataset, directly predicting two grasping points for each defined action from an RGBD image. However, it is also constrained to overhead view and limited to single t-shirt handling.

This study embarks on implementing a vision-based model for garment-handling robots to address these limitations. The envisioned model is designed to recognize the operating environment, establish a world coordinate system, detect garments, identify their types and states, estimate their positions and poses within the virtual coordinate system, and ultimately reconstruct a virtual representation of the real environment. Such a model would greatly aid human operators in understanding and supervising robotic operations in real-world scenarios.

To realize this vision, this research adopts an approach based on object SLAM (simultaneous localization and mapping), which integrates object and plane detection within the framework. This approach leverages 2D instance segmentation for garment detection and employs a hybrid reconstruction method, combining SLAM-based sparse 3D mapping with 3D planes generated from plane detection and garment representations in the form of meshes derived from instance segmentation results. To support the development of segmentation and reconstruction models, datasets of garments are collected and manually annotated. Experimental results showcase the improved performance of these models with the new datasets and demonstrate the feasibility of simultaneous garment and plane detection and reconstruction using the integrated SLAM approach.

The subsequent sections of this article will delve deeper into this research.

Section 2 will provide an overview of related work.

Section 3 will explain the methodologies of the integrated SLAM, while section 4 will present the experimental procedures and outcomes. Discussion of the results and outlines for future improvements will be elaborated in section 5. Finally,

Section 6 will offer a conclusive summary of this work.

2. Related Works

SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping), particularly visual SLAM, is a common method in robotics enabling devices to comprehend their position in unknown environments. It leverages visual data to generate cost-effective information. ORB-SLAM2 [

7], an advancement over ORB-SLAM (Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF SLAM) [

8], efficiently uses camera data for real-time mapping, representing environments via keyframe graphs. The limitations of point-feature-focused SLAM in low-texture environments spurred the development of feature-diverse methods like PlanarSLAM [

9]. CAPE (Cylinder and Plane Extraction) [

10] also exhibits potential in aiding SLAM by feature extractions from depth camera data. To improve environment understanding by incorporating semantic and object-level information, segmentations are added as new feature in SLAM. However, the sparse point cloud typically obtained through SLAM does not provide sufficient support for 3D instance segmentation while dense point map often struggles with loop closure and speed. Thus, using 2D segmentation and subsequently projecting the result to 3D space and utilizing plane features could be advantageous. DSP-SLAM (SLAM with Deep Shape Priors) [

11] is one such method, utilizing ORB-SLAM2 for tracking, mapping, Mask R-CNN [

12] for instance segmentation, and DeepSDF [

13] for object reconstruction. DeepSDF is an example of reconstructing rigid objects using mesh, which represents a 3D shape through a continuous Signed Distance Function (SDF) learned by a deep neural network. These studies provide valuable insights for the research field and for this work.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. System Overview

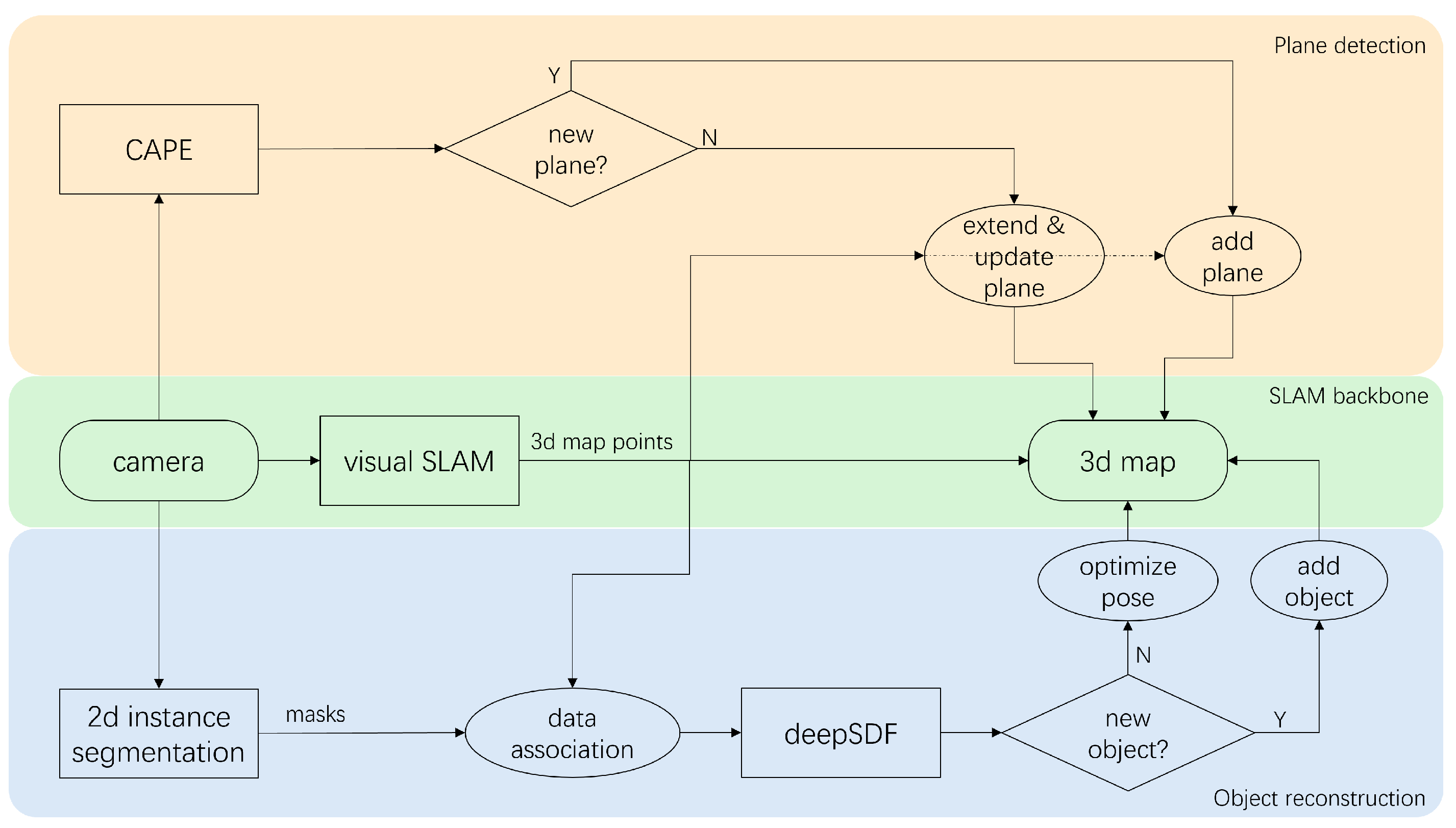

An overview of the integrated SLAM system is as depicted in

Figure 1. The system can be divided into three threads, with ORB-SLAM2 serving as the foundational SLAM backbone. The object thread aiming to detect and reconstruct garments follows the idea of DSP-SLAM, which performs 2D instance segmentation on each keyframe’s RGB image and then reconstruct segmented objects by DeepSDF from the masks inferred and the 3D map points derived from SLAM. Each object will either be associated with exiting objects in the map to update pose or be initialized and added as new object. Simultaneously, in the plane thread that aims to detect and reconstruct important environmental planes such as walls and table surfaces and improve SLAM’s performance in low-textured environment, depth images from each frame are fed into CAPE and detected planes are either associated with existing planes in the map to extend them or added as new entities. In the following subsections, implementation details will be introduced.

3.2. Garment Detection

To develop an instance segmentation model proficient in identifying garments within a particular environment and understanding the condition they are in, a dataset of various garments has been created and manually annotated. In terms of garment type, the focus at this stage is primarily on t-shirts, driven by the fact that one of the main example tasks of our study is the process of t-shirt printing.

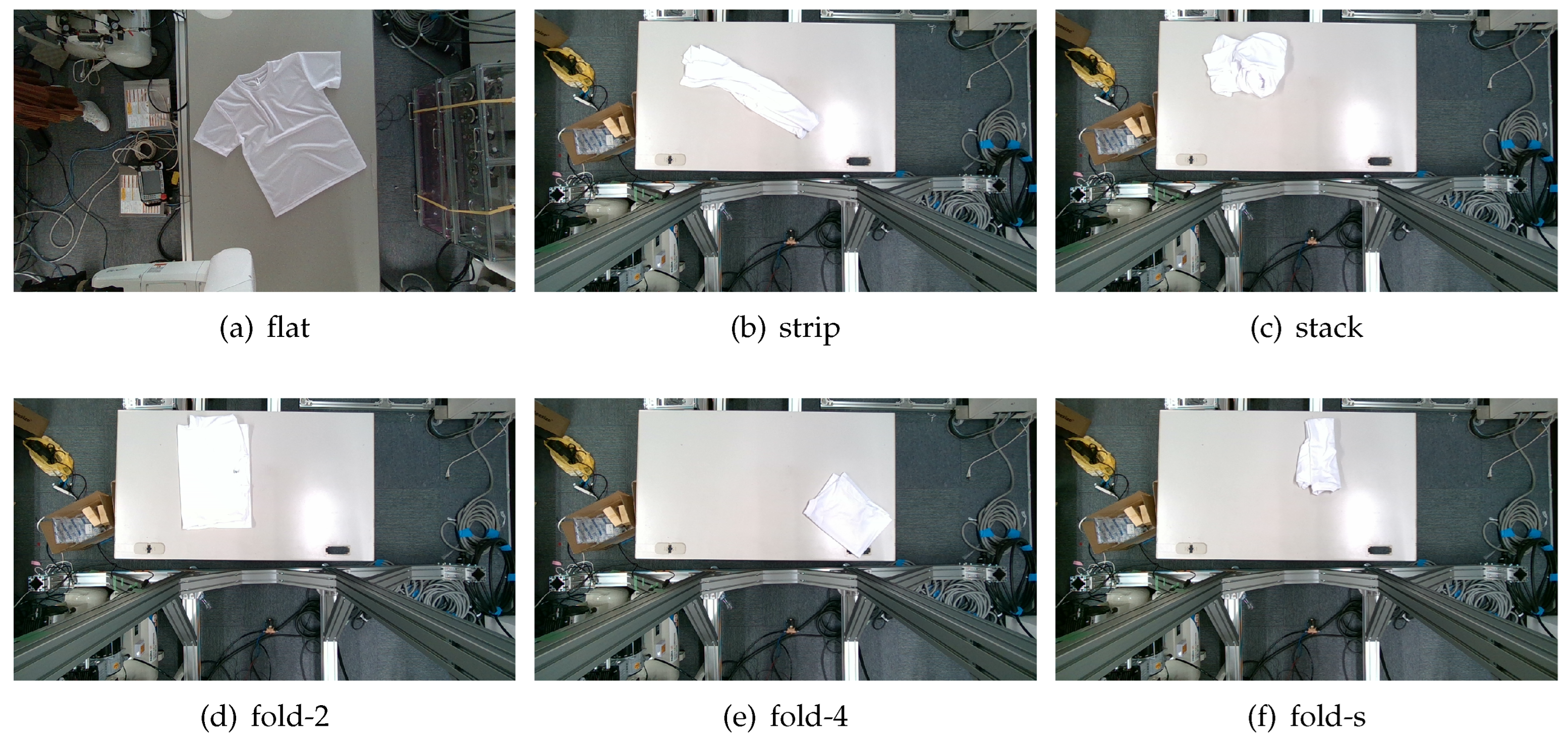

The garments in our study are categorized into six different states based on practical reasoning, as illustrated in

Figure 2, taking into account the most frequent conditions a t-shirt might assume throughout the industrial processing. This classification stems from common real-life actions and observations made at a garment factory:

Flat: This state denotes a t-shirt laid out largely flat on a surface, maintaining its recognizable shape. It may exhibit minor folds, particularly at the corners of the cuff or hem and sleeves.

Strip: In this state, the t-shirt is folded vertically but spread horizontally, assuming a strip-like shape. This can occur either by casually picking up the garment around the collar or both shoulders and then placing and dragging it on the table, or by carefully folding it from the flat state.

Stack: This state occurs when the t-shirt is picked up randomly at one or two points and then casually dropped on the table.

2-fold (or fold-2 as referred to later): Here, the t-shirt is folded once horizontally from the flat state, with the positions of the sleeves being random.

4-fold (or fold-4 as referred to later): In this state, the t-shirt is folded into a square-like shape. This can be achieved either by folding one more time vertically from the 2-fold state, or by folding in the style of a "dress shirt fold" or "military fold."

Strip-fold (or fold-s as referred to later): Here, the t-shirt is folded once more horizontally from the strip state. This mimics the method typically employed when one wishes to fold a t-shirt swiftly and casually.

The orientation of the t-shirt, whether it is front-up or back-up, is not predetermined but random. All the images in this dataset have been manually annotated by outlining each t-shirt segment and assigning a state class using LabelMe [

14].

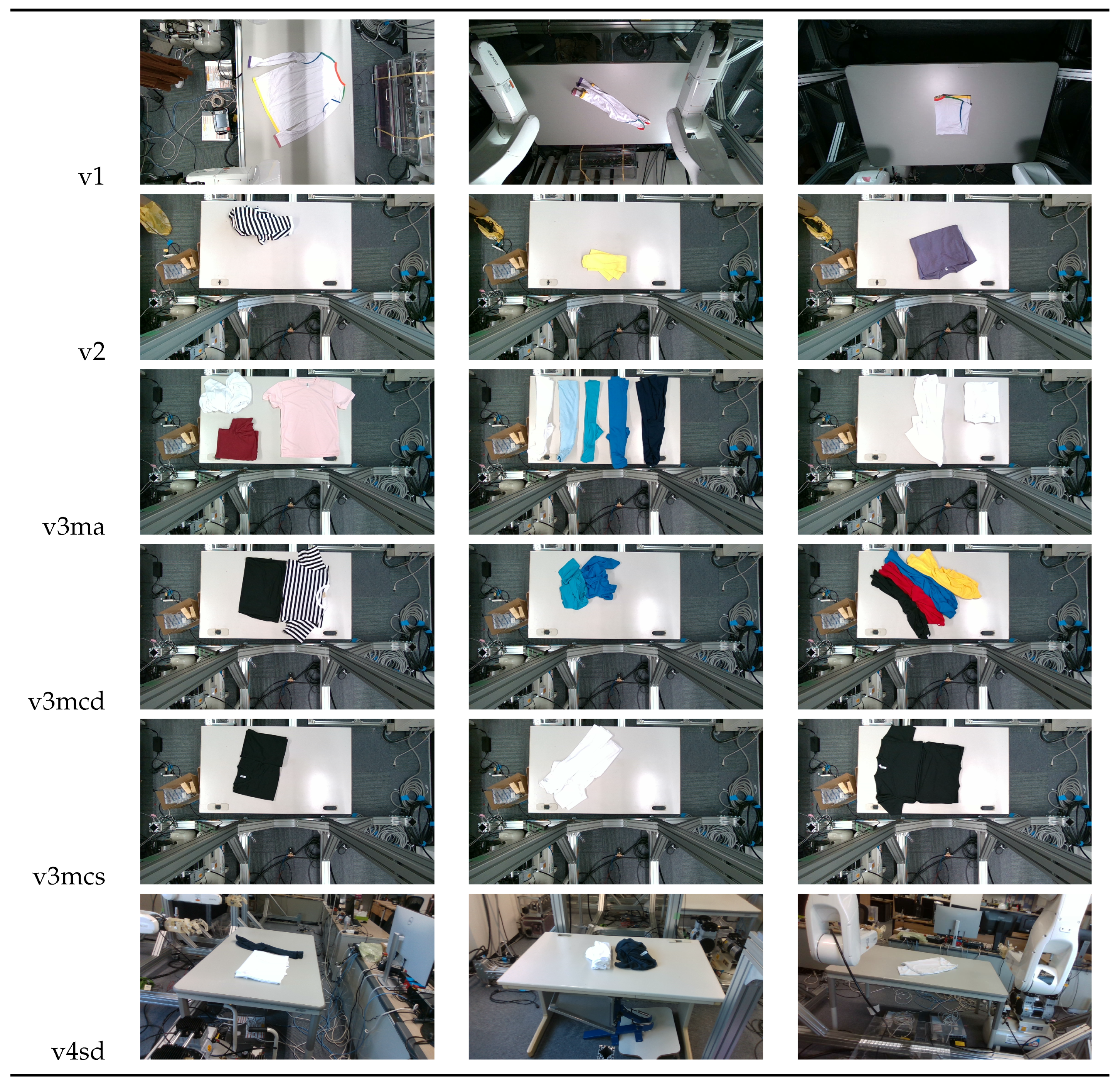

Our study encompasses four different versions of the dataset, each includes a separate set of test sets that emphasize the unique characteristics of the respective datasets:

V1 comprises 200 RGB images of a single t-shirt exhibiting painted sections, inclusive of both long and short-sleeved variants. The camera is strategically positioned above the table, capturing a bird’s-eye view of the garment and the table beneath it.

V2 adds colored and strip-patterned t-shirts. The test set featuring these new images is denoted as v2c in subsequent references.

V3 features multiple t-shirts (ranging from 2 to 6) within the same frame. The general test set featuring v3’s new data is identified as v3m. These images can be further divided into various sets based on the interaction among the t-shirts: (1) v3ma: several t-shirts of identical or differing colors placed separate from each other. (2) v3mcd: numerous t-shirts of varying colors placed adjacent to each other. (3) v3mcs: several t-shirts of the same color positioned right next to each other, with some arranged intentionally to create confusion. V3mcs type is only used for testing purposes, and is not included in the training set.

V4 its test set is referred to as v4sd. Two elements undergo change or addition: (1) camera view: the camera is no longer static over the table’s top. Instead, the images are derived from videos where the camera’s movements mimic a mobile robot, focusing on the operating table with the garments placed on it. (2) A new object class: the operating table is introduced as the 7th class in the detection.

A summary of the four versions of the dataset and their corresponding test sets is provided in

Table 1. Examples of each test set’s data are listed in

Figure 3.

Current 2D instance segmentation models can be broadly divided into two categories - two-stage approaches and one-stage approaches. While the two-stage approaches often deliver superior accuracy, the one-stage approaches distinguish themselves with their rapid detection speeds. Given the necessity for real-time operation and a balanced performance between precision and speed, this study employs four different models for training and testing purposes. Following an evaluation of the test results, a single model is selected. The four candidate models include MASK-RCNN [

12] (employed as a baseline for comparison), YOLACT [

15], SOLOv2 [

16], and SOLOv2-light (serving as a speed-accuracy trade-off comparison for SOLOv2). The models were selected based on the runtime statistics presented in their original research papers.

The selected models utilize RGB images as inputs and generate outputs in the form of bounding boxes

B, represented by the coordinates of diagonal points

, the label of object classes ranging from 0 to 5 or 0 to 6 in the case of dataset v4, and masks

M represented by the coordinates of polygon vertices. For single-stage detectors, bounding boxes are constructed based on the marginal vertices of the masks. The labels and masks are subsequently employed to identify the 3D points associated with the objects, facilitating their reconstruction on the map, a process to be detailed in

Section 3.5. The model parameters are refined and fine-tuned during the training phase.

3.3. Garment Reconstruction

Following the DSP-SLAM [

11] methodology, DeepSDF [

13] is employed as the object reconstruction method. DeepSDF is not only adept at shape reconstruction and completion tasks but also exhibits potent shape interpolation capabilities. This enables it to offer a more flexible reconstruction that adheres to the object’s form with minimal prior knowledge (training data), as opposed to constructing a rigid mesh solely based on prior knowledge and the identified object class.

In the context of this study, DeepSDF generates the SDF value by taking as inputs a shape code z and a 3D query location x.

In order to train a DeepSDF model capable of reconstructing garment meshes in six distinctive states and aligning with the instance segmentation results, a custom garment mesh model dataset is manually crafted. For this process, we employ Blender [

17], a free and open-source 3D computer graphics software toolkit widely used for various purposes. Blender’s parameters are calibrated through a series of experiments to fine-tune aspects such as the appearance and the motion performance, to obtain more realistic characteristics including the garment’s wrinkles.

The resulting dataset comprises 44 garment mesh models in total (4 flat, 12 strip, 9 stack, 4 fold-2, 10 fold-4, 5 fold-s), alongside 4 desk models drawn from ShapeNet v2 [

18]. Sample meshes generated from this dataset are depicted in

Table 2.

3.4. Plane Detection and Reconstruction

In this work, CAPE [

10] is utilized to extract plane features. CAPE’s plane extraction starts from a plane segmentation step done by region growing from randomly sampled points on the depth image. Plane models are subsequently fit to the plane segments. And finally refinement steps are performed to optimize the detected planes. The output planes

of CAPE are represented by a Hesse normal form

, where

denotes the unit normal vector of the plane, and

d denotes the distance from the origin of the coordinate system to the plane, with both pieces of information described in the camera coordinate system.

To determine the plane’s position in the world coordinate system, the transformation matrix

which conveys the transformation from world coordinate system to the current camera coordinate system is required, and it can be obtained during the SLAM process. The plane can thus be represented by

However, Hesse normal form plane

cannot be directly used in the SLAM system — specifically, during the bundle adjustment process — for estimating camera pose due to over-parameterization. In this work, coordinate system transformation is considered to solve this issue. In the Hesse normal form of a plane

,

d can be viewed as a distance or length, while

can be viewed as a unit normal vector that represents the orientation of the plane and this is where the redundancy originates. Spherical coordinate system is leveraged, using two angles

and

to represent a unit vector in the 3D space, with

as the azimuth angle and

as the elevation angle, the Hesse normal form plane

can be reformed into:

Notice that

and

have a limited range of

to circumvent singularity problems.

3.5. SLAM Integration

3.5.1. Object Reconstruction and Association

After the instance segmentation, a bounding box B, a mask M, and a class label C will be assigned to each candidate instance I. And from the SLAM backbone, a set of sparse point observations D is obtained. The task is then to estimate the dense shape z and its 7-dof pose from these. The initial pose is obtained by applying PCA to the sparse point cloud of object and initial shape code . Then z and are refined iteratively as a joint optimization problem.

Two loss terms in terms of energy term [

11] are initially used in this refinement procedure. Surface Consistency Loss

measures 3D points’ alignment with the surface of the reconstructed object, and differentiable SDF Render Loss

calculates a difference between the observed depth and expected depth to align the size.

In order to reconstruct multiple objects, especially in the case where two objects are overlapping in the camera view, the above-mentioned refinement is done for every detected instance. In addition, in the process of calculating the occupancy probability of whether a point is inside, outside, or on an object, every point will be recalculated for the second object even if it’s already calculated to be inside one object in case of occlusion.

However, these would lead to another issue: penetration or collision between reconstructed objects. To mitigate this, a Repulsive Loss

[

19] is introduced into the overall loss function. Penetrations are discerned by the number of times a ray from a point on one object intersects the surface of another object. And Repulsive loss calculates the distances of all the penetrated sampled points to another object. Unfortunately, this loss is still not ideal because of the randomness of objects’ poses and the limited number of rays and sampled points, the projected rays will not always detect existing penetrations. This is to be improved in the future.

The final loss

L is a weighted sum of the Surface Consistency Loss

, the SDF Render Loss

, Repulsive Loss

and a regularization term of shape

z:

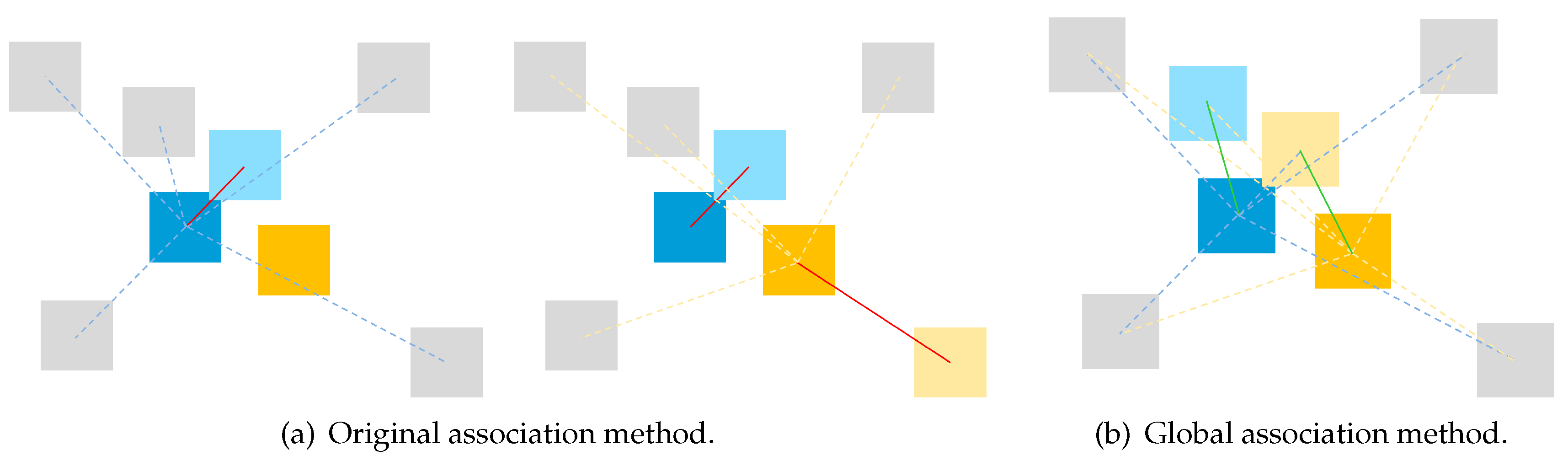

Once detections are reconstructed, they are to be associated with objects in the map. The number of matched feature points

between the detection and the object is the criteria. If

is bigger than a threshold

, then the detection will be considered as an association candidate. In [

11], only the nearest is maintained if one object might also be assigned multiple detection candidates. However, this could lead to incorrect associations in cases where multiple objects are in close proximity and cameras are moving quickly, and when one detection might be the association candidate for multiple objects, as depicted in

Figure 4. To resolve this, a global minimal association distance of all the association candidates is calculated instead.

Detections that are not the association candidates for any existing object will be considered as new object candidates. To mitigate the impact of erroneous detections and outliers, a candidate for a new object will only become a true new object and be added into the map when it is detected in consecutive keyframes.

3.5.2. Plane Matching

The plane feature matching can be done by comparing the angle and distance between the two planes, which can be obtained by calculating from the distance

d, and the normal vector

n or the angles

under the spherical coordinate system. Firstly, the angle between the two planes

are calculated. And only when

, the distance

between the two planes will be calculated. The distance

is calculated by

where

is the

m randomly sampled points from the map plane, and

is the detected plane in the current frame. If

, the detected plane will be considered a match for the map plane.

For the matched planes, new point clouds are built and extended into the matching map planes. The detected planes that are not matched to any existing map plane will be considered as new planes and added into the map. The Voxel grid in PCL library is used to filter the plane point cloud, which helps reduce the number of points and computation cost. The leaf size of voxel grid is set to be 0.05.

Similar to object association, in order to reduce the number of bad planes and noises, every newly detected plane has to be detected more than times to be added in the map.

3.5.3. Joint Optimization

Keyframe acceptance rules are modified because of the addition of plane features in each frame. The frame that detects a new plane will be considered as a keyframe and will not be removed as bad keyframe in the local mapping thread. In addition, plane features are also considered in the tracking initialization. Other than detecting more than 500 point features, detecting no less than 3 planes and at least 50 points is also considered feasible for initialization. The numbers are given by experiments.

As the baseline method, ORB-SLAM2 uses Bundle Adjustment to optimize the camera pose and the map of points. In this work, the final map consists of a set of camera poses

, map points

, object poses

, and map planes

. And they can be optimized by a joint BA as a least squares optimization problem following the same idea:

where ∑ represents the co-variance matrix, and

,

, and

represents the error equation between the camera pose and the map points, object pose, and map planes respectively. Camera-point error

is the same as the reprojection error in ORB-SLAM2. Camera-object error

follows that of DSP-SLAM. While camera-plane error

follows the same pattern as camera-point error:

where

is the matched map plane in the world coordinated system of plane

in the camera coordinate system.

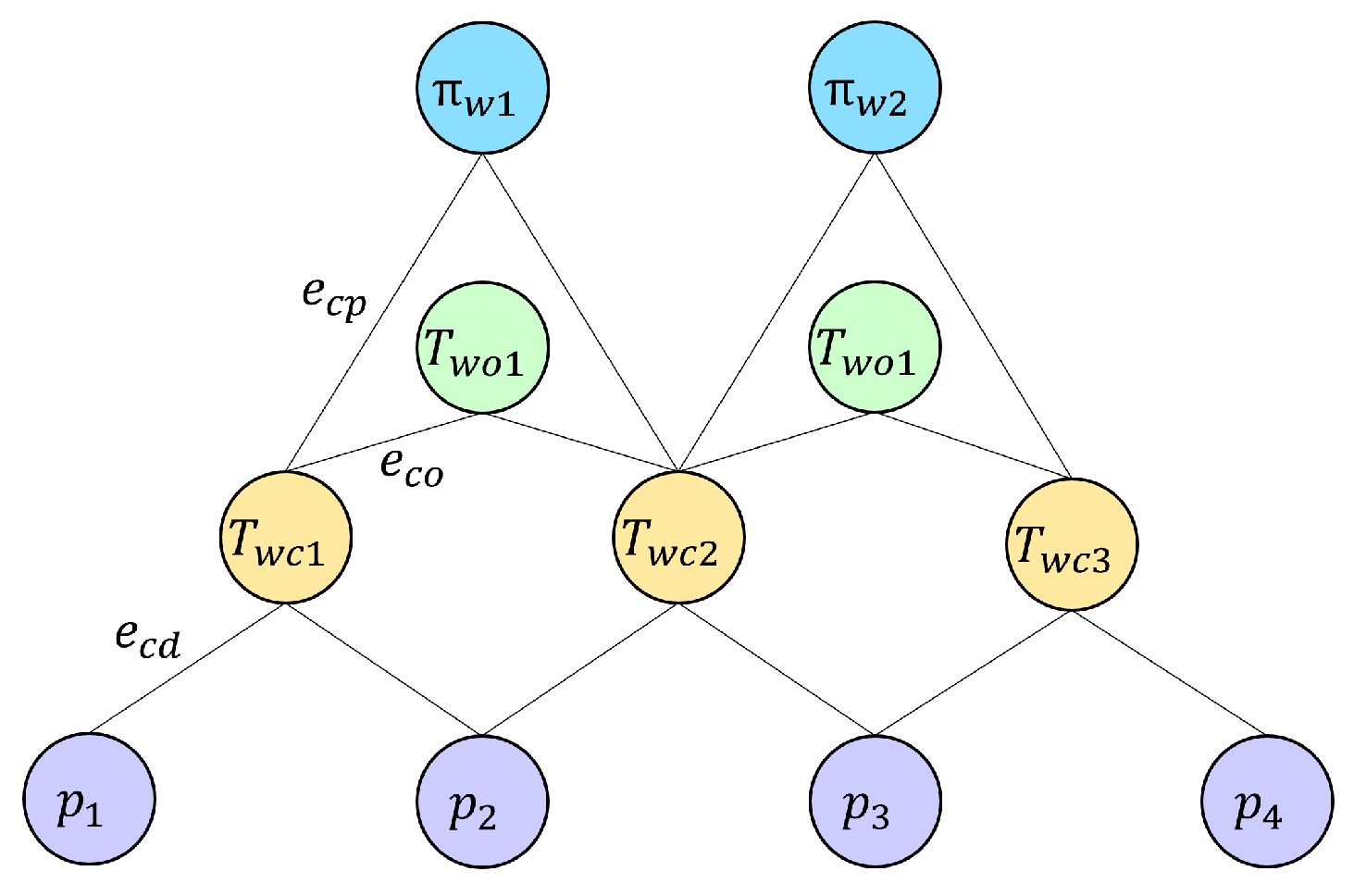

Similar to ORB-SLAM2, this BA problem is constructed as a graph optimization, and both the objects and planes are treated as vertices like the feature points, as dipicted in

Figure 5. The error terms, which can be seen as new pose observations, serve as edges in the graph connecting camera pose vertices to feature point vertices, object pose vertices, or plane vertices.

4. Results

4.1. 2D Garment Recognition

This subsection delves into the experiments conducted using four instance segmentation models (MaskRCNN, YOLACT, SOLOv2, SOLOv2-light) trained on various versions of our collected garment dataset and tested on different test sets emphasizing various features. The underlying expectation was that the custom dataset would enable the models to proficiently recognize garments (t-shirts) and the environment (desk) with diverse attributes. Subsequently, based on the evaluation of segmentation accuracy and inference speed, one model was selected for integration with the SLAM framework. All training and testing processes were performed on an Intel CORE i9 CPU paired with an NVIDIA RTX 3090 laptop GPU.

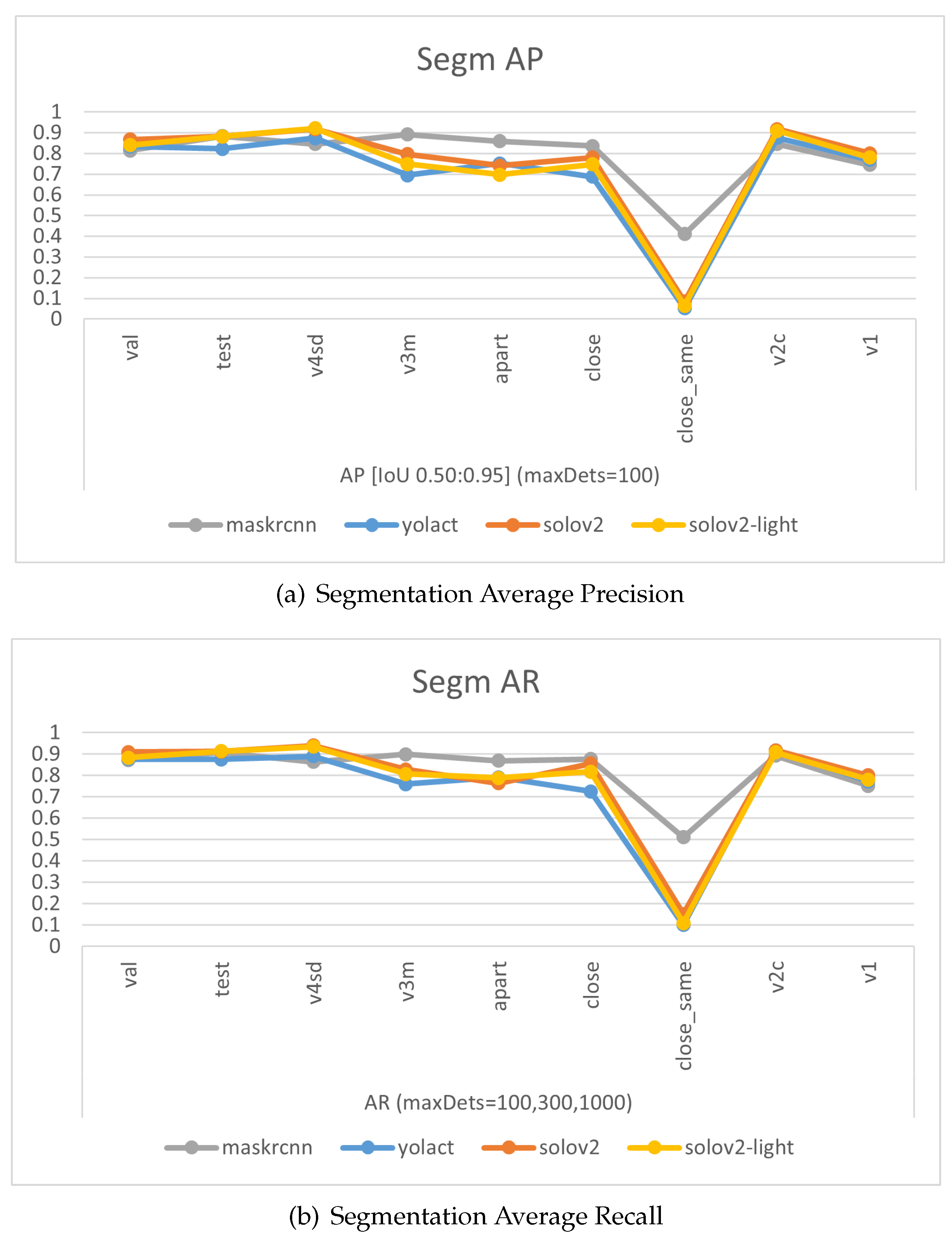

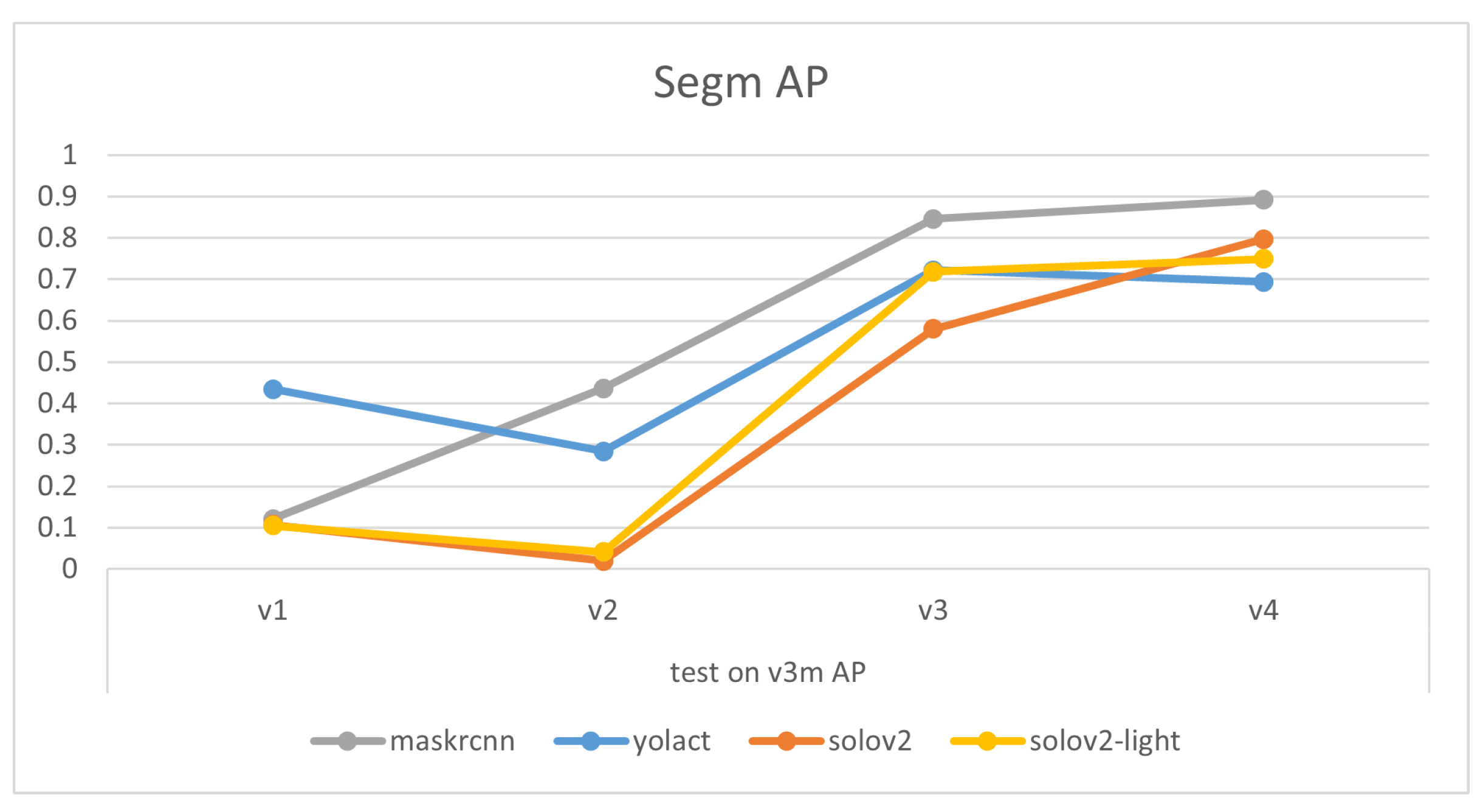

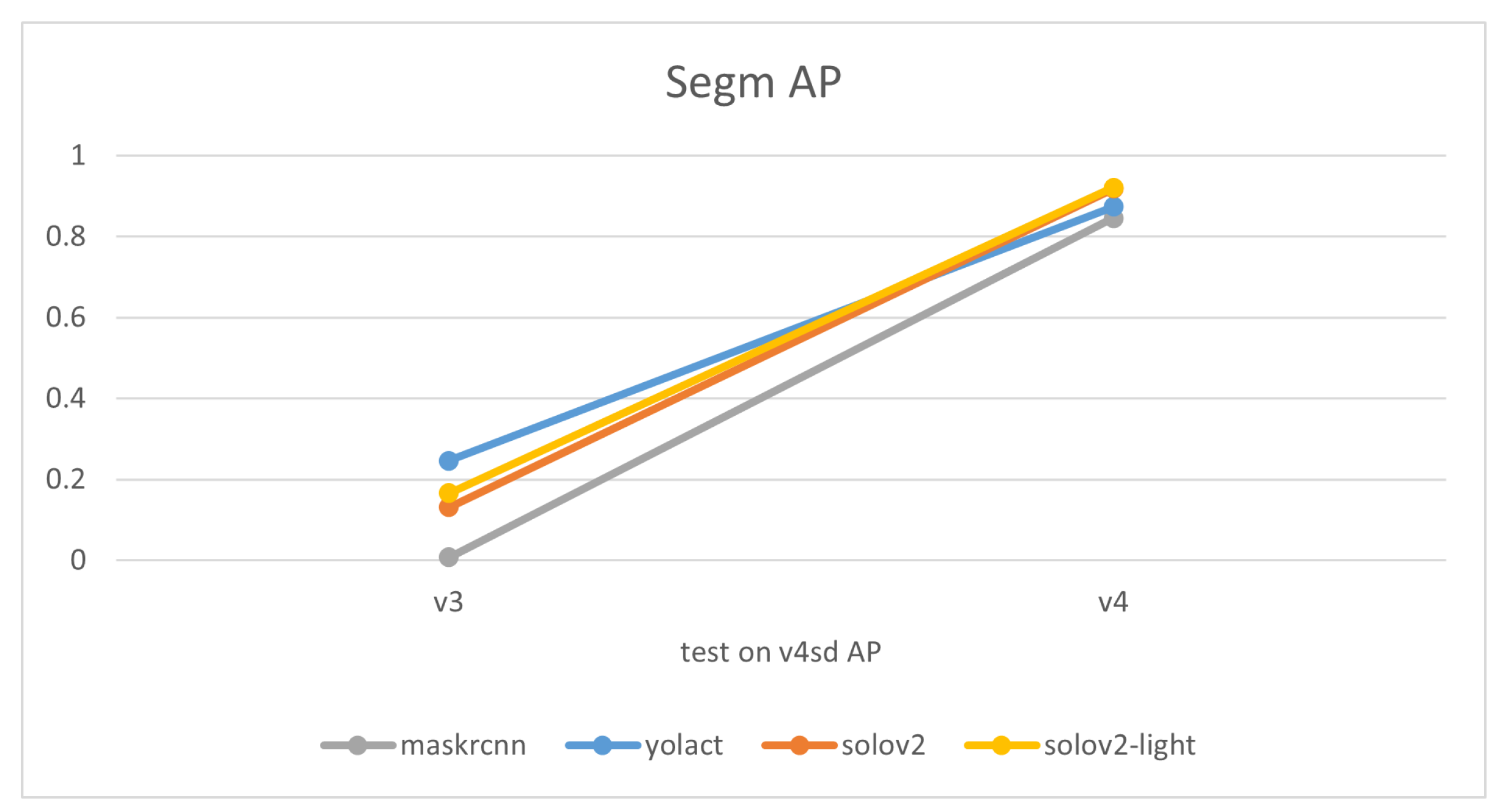

The experimental results of models trained on the final dataset v4 emphasize that overall, as shown in

Figure 6 and

Table 3 and

Table 4, SOLOv2, and SOLOv2-light outshine YOLACT and Mask R-CNN in terms of the precision of their masks. Notably, MASK-RCNN displays superior accuracy over the other three models when it comes to scenarios with multiple garments. Especially in situations where the data are unfamiliar—instances of v3mcs that were not included in the training dataset—MASK-RCNN exhibits a slightly stronger generalization ability. However, for single-garment scenarios, or those involving a shift in viewing angle or the addition of the ’desk’ class, the performance ranks as follows: SOLOv2>=SOLOv2-light>YOLACT>Mask-RCNN. Interestingly, the overall trend of Recall closely mirrors that of Average Precision (AP). This consistency between recall and precision suggests that the trained models are well-balanced, showing similar tendencies in identifying relevant instances (recall) and correctly labelling instances as relevant (precision). It reflects a situation where the model has a good equilibrium between its ability to find all the relevant instances and its ability to minimize the incorrect classification of irrelevant instances, thus demonstrating both effective and reliable performance.

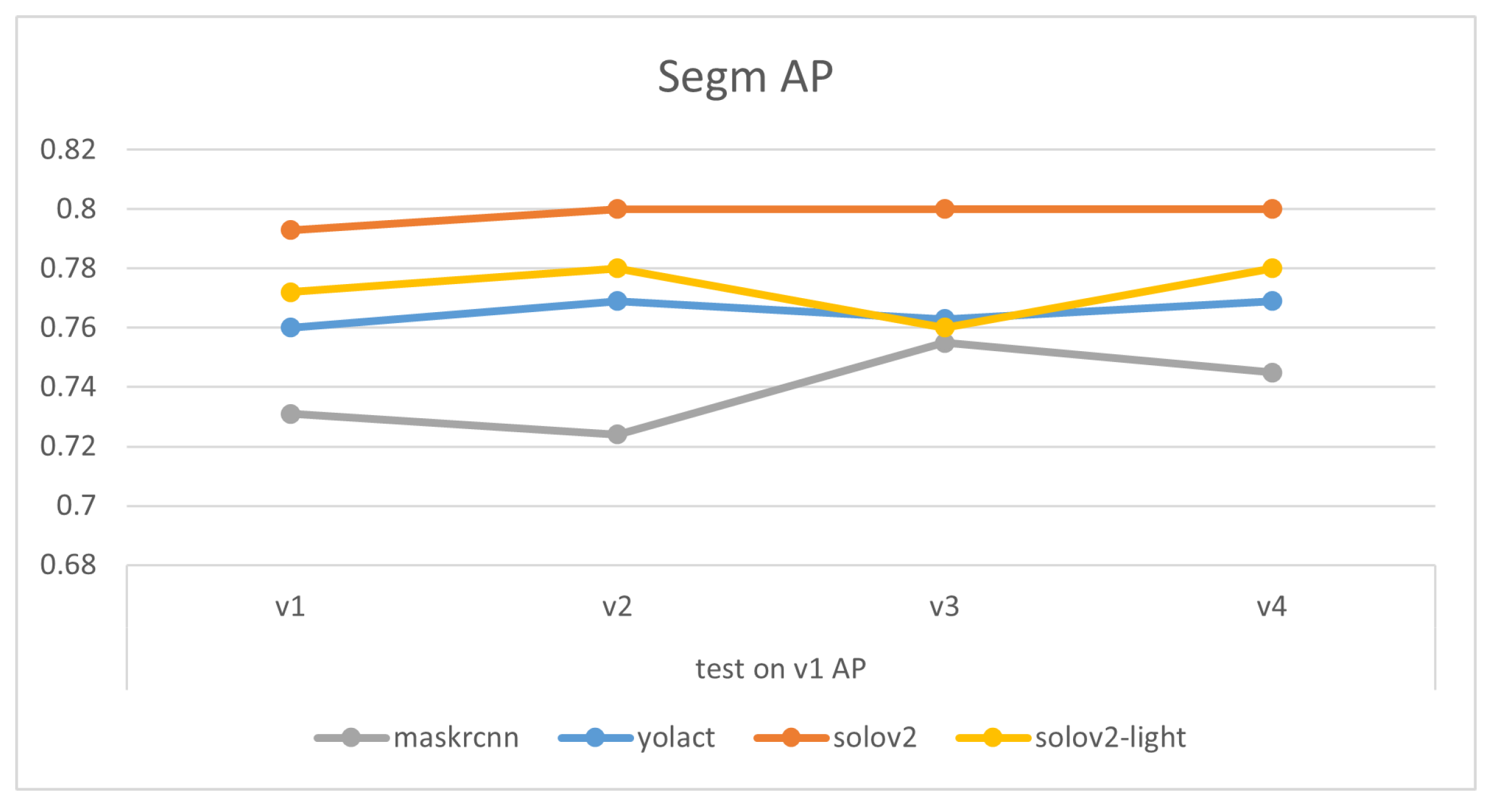

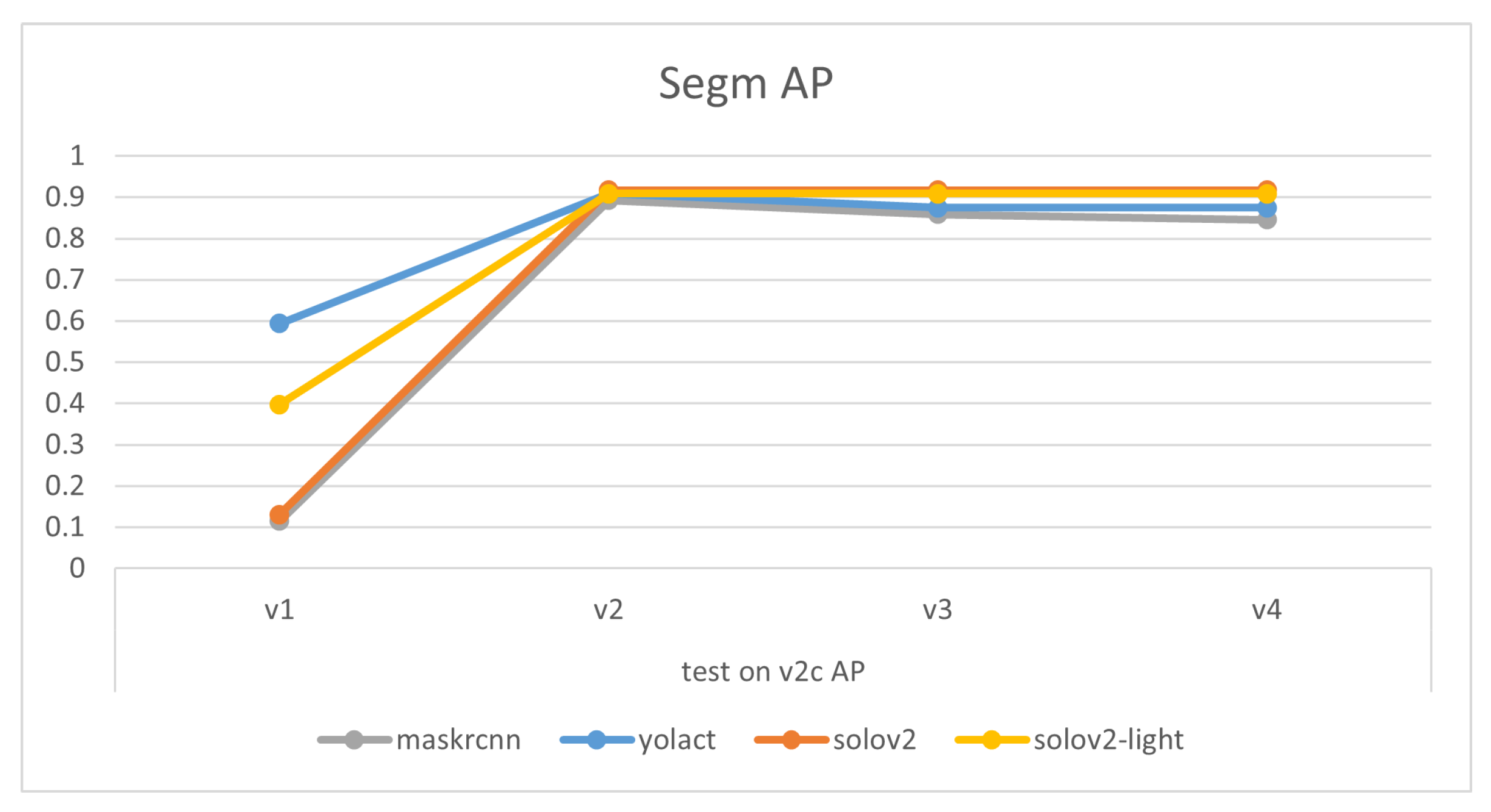

Comparisons of models’ mask precision throughout the addition of new training data, as illustrated in

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, demonstrate that generally the expansion of dataset improves models’ performances. Distinctly, the addition of v4’s new data led to a decrease in the accuracy of YOLACT’s recognition of the v3m dataset. This could be because YOLACT was ‘overfitting’ to multiple objects with similar sizes. On another note, YOLACT has better precision on untrained data type, e.g., tested on v4sd when only trained on v3, which implies that it has better generalization capabilities.

Examples of visualized estimated masks are demonstrated in

Table 5 and

Table 6. It is worth noting that, while SOLOv2 demonstrates satisfactory performance in recognizing and distinguishing multiple objects such as tables and clothing, it faces difficulties in identifying multiple pieces of clothing. Although it maintains the highest mask margin precision for all the test sets, which corresponds to the high AP evaluated, SOLOv2 struggles to tell different garments apart. This may be attributed to its nature as a location-based one-stage method, thereby limiting its capacity to discern multiple similar objects like garments. On the other hand, while YOLACT performs nicely on distinguishing multiple garments, it sometimes struggles with mask boundaries when garments are touching.

The models were also tested with a sequence of RGB images of resolution 1280x720, recorded by an Intel Realsense D435i camera. The camera’s movements were designed to imitate the motion needed to scan the environment, with the operating desk and garments roughly in the center of view. This mimics a real-world scenario, creating conditions for our models that reflect those they would encounter in practical applications. Example results are as presented in

Table 6. Mask-RCNN faces challenges in recognizing the desk, and the masks of garments lack precision as with the dataset. YOLACT, on the other hand, demonstrates an ability to accurately segment both the garments and the desk, despite occasional difficulties with an edge of the desk. SOLOv2 and SOLOv2-light present the most accurate desk masks, but they still struggle to differentiate between separate garments.

Furthermore, the models are tested directly using an Intel Realsense D435i camera to run in real-time. Input RGB frames are with sizes of 1280*720. The example results are as presented in

Table 6. The performances are similar to those of the recorded videos. YOLACT demonstrates a superior balance in the precision of mask margins and the differentiation of individual garments. Interestingly, YOLACT, SOLOv2, and SOLOv2-light are capable of detecting the partially visible second desk in the frame, even though such situations were not included in the training set. However, only YOLACT correctly identifies it as a separate desk; SOLOv2 and SOLOv2-light struggle to differentiate between individual objects and incorrectly perceive it as part of the central desk.

In the context of speed, SOLOv2-light leads the pack for recorded videos, while YOLACT emerges as the fastest when tested with camera real-time, as demonstrated in

Table 7.

In summary, the performance of the models can be ranked differently depending on the scenario at hand:

Single t-shirt. For the detection of a single clothing item, the models are ranked based on mask precision as follows: SOLOv2 >= SOLOv2-light > YOLACT > Mask-RCNN. The primary distinction in this scenario is the accuracy of mask edges.

Multiple t-shirts. When it comes to detecting multiple clothing items, the rankings shift to: Mask-RCNN > YOLACT >> SOLOv2-light >= SOLOv2, the main distinction lying in the models’ ability to differentiate between different pieces of clothing. Notably, even though SOLOv2 and SOLOv2-light yield the most accurate masks among the four models, they struggle to distinguish different t-shirt pieces in most cases. This discrepancy may contribute to their higher rankings when only considering mask precision on the v3m test set, where the ranking is Mask-RCNN > SOLOv2 > SOLOv2-light > YOLACT.

Shifting view angle. In the context of recognizing objects from various angles and identifying desks, the ranking shifts to SOLOv2-light >= SOLOv2 > YOLACT > Mask-RCNN.

Reference speed. Finally, in terms of inference speed, SOLOv2-light and YOLACT are the fastest, trailed by Mask-RCNN and SOLOv2.

Considering all the results, YOLACT stands out as the model that strikes a good balance in all categories and performs commendably across all the tested scenarios. Hence, YOLACT was chosen for further experimentation and SLAM integration.

4.2. Garment Mesh Reconstruction

DeepSDF were trained and tested on the self-created garment mesh dataset to enable the model of reconstructing garments under various states. The reconstructions were evaluated by Chamfer distance, which was calculated by determining the average Euclidean distance of each point on the reconstructed mesh to its nearest point on the ground truth mesh, and of each point on the ground truth mesh to its nearest point on the reconstructed mesh. The results of the DeepSDF reconstruction are presented in

Table 8 and

Table 9. At present, objects with more pronounced three-dimensional features tend to have better reconstruction results. The hierarchy of reconstruction accuracy appears to follow this order: tables show superior results, followed by stacks, and finally, other flatter garment states. It is worth noting that un-folded sleeves present significant ambiguity and currently occupy a disproportionately large portion of our dataset. Future work could aim at better distribution of garment states in the dataset to address this issue.

4.3. SLAM Integration

This subsection provides an overview of the experiments conducted on open-source datasets and real-time data respectively, to test the feasibility of this integrated SLAM approach. To highlight the impact of integrated plane detection and object reconstruction functions on our system, tests were carried out on versions of the SLAM system: one that integrates only the object reconstruction, and another one that integrates only the plane detection. We will compare and contrast these results to provide a view of the different systems’ performances.

Firstly, only the object reconstruction component was introduced into the SLAM system (akin to DSP-SLAM). Utilizing a MaskRCNN model trained on the COCO dataset [

20], tests were conducted and object reconstruction was performed on the Redwood dataset [

21]. The camera trajectory error was then evaluated on the KITTI dataset [

22]. A Relative Translation Error (RTE) and a Relative Rotation Error (RRE) of 1.41 and 0.22 were achieved, which unfortunately couldn’t outperform ORB-SLAM2’s 1.38 and 0.20.

Subsequently, only the plane detection component was integrated into the SLAM system and comparisons were carried out with ORBSLAM2 using the TUM dataset [

23]. On sequence fr3_cabinet where ORB-SLAM failed to track due to insufficiency of feature points, integrating the plane thread achieved an Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) of 0.0202.

The SLAM systems were then tested using an Intel Realsense D435i camera as the input sensor capturing RGB and depth images with a size of 680*480. The systems ran on a laptop with Intel i9 CPU and a NVIDIA RTX 3090 Laptop GPU. The results show that this SLAM-based approach could successfully detect and reconstruct the garments and large environmental planes, as presented in

Table 10. However, several challenges are evident: the quality of reconstruction, and the execution speed. The reconstructed garments do not always accurately represent their real-world counterparts, and penetrations still occur occasionally. This could be attributed to both the reconstruction loss function and the mesh dataset. Regarding the speed, a decrease can be observed with the addition of each detection model, as demonstrated in

Table 11. Thus, an improved strategy for computing is necessary.

5. Discussion

The results of the instance segmentation analysis demonstrate that with the collected dataset of six garment states, the models exhibit a noteworthy understanding of garment states as well as their shapes and positions. This achievement opens up the possibility of expanding the potential use cases, and can be potentially expanded to other garment types. Additionally, leveraging the information on garment states, the next phase of our research will involve predicting grasping points and estimating garment parts. Utilizing garment states has the potential to significantly optimize robotic actions, reducing task completion time. However, it is important to note that the current models face challenges in distinguishing between multiple garments of the same color when they are stacked together. Addressing this limitation will be a focal point of future research, involving improvements to both the dataset and the model architecture.

The integration of the SLAM approach showcases the feasibility of simultaneous garment and plane detection and reconstruction, offering promising prospects for improving collaboration between human operators and robots in remote scenarios. Nevertheless, there exist notable avenues for enhancing and refining the current SLAM structure. The first concerns the reconstruction loss, where the current amalgamation of Surface Consistency loss, SDF Render loss, and Repulsive loss doesn’t completely prevent instances of object penetration. Introducing additional collision penalization terms could be explored as a means to mitigate this issue effectively.

Secondly, it is observed that one of the key reasons for unsatisfactory reconstructions is suboptimal outcomes from the DeepSDF model. The decrease in trajectory estimation accuracy might also be linked to this. A biased object reconstruction may skew the camera pose away from the correct one, considering that they are optimized jointly. One plausible cause for the subpar DeepSDF reconstruction results may be the quality of the training dataset. On one hand, the mesh representations in the dataset may not accurately reflect the real-world variability of garments. On the other hand, the dataset may be insufficient in terms of size, especially considering that the challenging instances with unfolded sleeves occupy a disproportionately large portion of it. Another potential issue could be the limited number of points extracted from images by SLAM, used as input for DeepSDF, necessitating a significant structural modification.

In terms of computational speed, potential improvements could be achieved through parallel computing, distributing tasks across different CPU cores. Our analysis reveals that GPU usage remains below 30% during processing, indicating that instance segmentation is not the limiting factor. Conversely, CPU computing, primarily reliant on a single core, frequently reaches its maximum capacity during model execution. Future research efforts could thus explore strategies to harness parallel computing to expedite processing times and optimize system performance.

6. Conclusions

This work explored an object SLAM-based method aimed at garment recognition and environment reconstruction for potential robot handling tasks. This methodology is comprehensively detailed in

Section 3, while the experiments conducted and their resultant data are discussed in

Section 4. To facilitate this approach, four distinct versions of a 2D image garment dataset are collected to train four existing instance segmentation models. The evaluation outcomes revealed that YOLACT achieved an optimal balance between segmentation accuracy and processing speed, leading to its usage in the integrated SLAM. Simultaneously, a synthetic garment mesh dataset was generated using the Blender software, which was used to train the DeepSDF model. Despite the robust training, the reconstruction results of the trained DeepSDF model showed limitations when dealing with flatter garments and those presenting complex shapes. Finally, a series of experiments using the integrated SLAM approach were carried out, which included configurations with only the object detection thread, with only the plane detection thread, and with both threads. These tests were conducted on both datasets and using a Realsense camera. The results showed that we could successfully reconstruct multiple garments and planes simultaneously.

Author Contributions

Data curation, Yilin Zhang; Methodology, Yilin Zhang; Supervision, Koichi Hashimoto; Visualization, Yilin Zhang; Writing – original draft, Yilin Zhang; Writing – review & editing, Koichi Hashimoto. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Innovation and Technology Commission of the HKSAR Government under the InnoHK initiative, and by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 21H05298.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Foresti, G.L.; Pellegrino, F.A. Automatic visual recognition of deformable objects for grasping and manipulation. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews) 2004, 34, 325–333. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Y.H. Learning-based fabric folding and box wrapping. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2022, 7, 5703–5710. [CrossRef]

- Willimon, B.; Birchfield, S.; Walker, I. Classification of clothing using interactive perception. 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. IEEE, 2011, pp. 1862–1868.

- Doumanoglou, A.; Stria, J.; Peleka, G.; Mariolis, I.; Petrik, V.; Kargakos, A.; Wagner, L.; Hlaváč, V.; Kim, T.K.; Malassiotis, S. Folding clothes autonomously: A complete pipeline. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2016, 32, 1461–1478. [CrossRef]

- Avigal, Y.; Berscheid, L.; Asfour, T.; Kröger, T.; Goldberg, K. Speedfolding: Learning efficient bimanual folding of garments. 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–8.

- He, C.; Meng, L.; Wang, J.; Meng, M.Q.H. FabricFolding: Learning Efficient Fabric Folding without Expert Demonstrations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.06587 2023.

- Mur-Artal, R.; Tardós, J.D. Orb-slam2: An open-source slam system for monocular, stereo, and rgb-d cameras. IEEE transactions on robotics 2017, 33, 1255–1262. [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM: a versatile and accurate monocular SLAM system. IEEE transactions on robotics 2015, 31, 1147–1163. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yunus, R.; Brasch, N.; Navab, N.; Tombari, F. RGB-D SLAM with structural regularities. 2021 IEEE international conference on Robotics and automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2021, pp. 11581–11587.

- Proença, P.F.; Gao, Y. Fast cylinder and plane extraction from depth cameras for visual odometry. 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2018, pp. 6813–6820.

- Wang, J.; Rünz, M.; Agapito, L. DSP-SLAM: object oriented SLAM with deep shape priors. 2021 International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1362–1371.

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 2961–2969.

- Park, J.J.; Florence, P.; Straub, J.; Newcombe, R.; Lovegrove, S. Deepsdf: Learning continuous signed distance functions for shape representation. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 165–174.

- Torralba, A.; Russell, B.C.; Yuen, J. Labelme: Online image annotation and applications. Proceedings of the IEEE 2010, 98, 1467–1484. [CrossRef]

- Bolya, D.; Zhou, C.; Xiao, F.; Lee, Y.J. Yolact: Real-time instance segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 9157–9166.

- Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Kong, T.; Li, L.; Shen, C. Solov2: Dynamic and fast instance segmentation. Advances in Neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 17721–17732.

- blender.org.

- Chang, A.X.; Funkhouser, T.; Guibas, L.; Hanrahan, P.; Huang, Q.; Li, Z.; Savarese, S.; Savva, M.; Song, S.; Su, H.; Xiao, J.; Yi, L.; Yu, F. ShapeNet: An Information-Rich 3D Model Repository. Technical Report arXiv:1512.03012 [cs.GR], Stanford University — Princeton University — Toyota Technological Institute at Chicago, 2015.

- Hasson, Y.; Varol, G.; Tzionas, D.; Kalevatykh, I.; Black, M.J.; Laptev, I.; Schmid, C. Learning joint reconstruction of hands and manipulated objects. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 11807–11816.

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6-12, 2014, Proceedings, Part V 13. Springer, 2014, pp. 740–755.

- Choi, S.; Zhou, Q.Y.; Miller, S.; Koltun, V. A large dataset of object scans. arXiv preprint arXiv:1602.02481 2016.

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Stiller, C.; Urtasun, R. Vision meets robotics: The kitti dataset. The International Journal of Robotics Research 2013, 32, 1231–1237. [CrossRef]

- Sturm, J.; Engelhard, N.; Endres, F.; Burgard, W.; Cremers, D. A benchmark for the evaluation of RGB-D SLAM systems. 2012 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems. IEEE, 2012, pp. 573–580.

Figure 1.

Work flow of the integrated SLAM. The SLAM backbone detects feature points and reconstruct a 3D map of sparse points. The object reconstruction thread detects garments and desks and reconstructs them by DeepSDF [

13] in the map. The plane detection thread detects and reconstructs planes using CAPE [

10] and matches them to the map.

Figure 1.

Work flow of the integrated SLAM. The SLAM backbone detects feature points and reconstruct a 3D map of sparse points. The object reconstruction thread detects garments and desks and reconstructs them by DeepSDF [

13] in the map. The plane detection thread detects and reconstructs planes using CAPE [

10] and matches them to the map.

Figure 2.

Examples of the 6 garment states.

Figure 2.

Examples of the 6 garment states.

Figure 3.

Examples images from different version’s dataset.

Figure 3.

Examples images from different version’s dataset.

Figure 4.

Comparison of a potential false association case with the correct result by the global association method. In situations where two objects, A and B, are in close proximity, B’s true match might be misidentified as A’s closest candidate by the original method, leading to its removal from B’s candidate list. A global association method, however, could correctly associates the objects.

Figure 4.

Comparison of a potential false association case with the correct result by the global association method. In situations where two objects, A and B, are in close proximity, B’s true match might be misidentified as A’s closest candidate by the original method, leading to its removal from B’s candidate list. A global association method, however, could correctly associates the objects.

Figure 5.

Illustration of graph optimization. Orange vertices represent camera poses, purple vertices represent feature points, green vertices represent object poses, and blue vertices represent planes. The edges connecting these vertices represent the error terms to be optimized.

Figure 5.

Illustration of graph optimization. Orange vertices represent camera poses, purple vertices represent feature points, green vertices represent object poses, and blue vertices represent planes. The edges connecting these vertices represent the error terms to be optimized.

Figure 6.

Charts of Average Precision (AP) and Average Recall (AR) evaluated on different test sets for the four models.

Figure 6.

Charts of Average Precision (AP) and Average Recall (AR) evaluated on different test sets for the four models.

Figure 7.

Variations of models’ performances trained on different datasets, tested on v1.

Figure 7.

Variations of models’ performances trained on different datasets, tested on v1.

Figure 8.

Variations of models’ performances trained on different datasets, tested on v2c.

Figure 8.

Variations of models’ performances trained on different datasets, tested on v2c.

Figure 9.

Variations of models’ performances trained on different datasets, tested on v3m.

Figure 9.

Variations of models’ performances trained on different datasets, tested on v3m.

Figure 10.

Variations of models’ performances trained on different datasets, tested on v4sd.

Figure 10.

Variations of models’ performances trained on different datasets, tested on v4sd.

Table 1.

Summary of the four versions’ dataset. The numbers represent how many RGB images there are in the set.

Table 1.

Summary of the four versions’ dataset. The numbers represent how many RGB images there are in the set.

| |

Features |

Size (number of images) |

| |

top view only |

multiple colors |

multiple t-shirts |

including desk class |

train |

validation |

test |

all |

| v1 |

∘ |

|

|

|

180 |

10 |

10 |

200 |

| v2 |

∘ |

∘ |

|

|

419 |

23 |

23 |

465 |

| v3 |

∘ |

∘ |

∘ |

|

614 |

34 |

34 |

682 |

| v4 |

|

∘ |

∘ |

∘ |

774 |

43 |

43 |

860 |

Table 2.

Examples of the 6 garment states from created garment mesh dataset.

Table 3.

Average Precision of masks on different test sets of the four models. Mask-RCNN demonstrates better results on multiple t-shirts, while SOLOv2 and light are better on single t-shirt.

Table 3.

Average Precision of masks on different test sets of the four models. Mask-RCNN demonstrates better results on multiple t-shirts, while SOLOv2 and light are better on single t-shirt.

| segmentation |

AP [IoU 0.50:0.95] (maxDets=100) |

| |

val |

test |

v1 |

v2c |

v3m |

v3m-a |

v3m-cd |

v3m-cs |

v4sd |

| Mask-RCNN [12] |

0.814 |

0.883 |

0.745 |

0.846 |

0.892 |

0.859 |

0.836 |

0.410 |

0.846 |

| YOLACT [15] |

0.833 |

0.822 |

0.769 |

0.875 |

0.694 |

0.751 |

0.688 |

0.052 |

0.874 |

| SOLOv2 [16] |

0.867 |

0.882 |

0.800 |

0.917 |

0.797 |

0.741 |

0.780 |

0.084 |

0.918 |

| SOLOv2-light [16] |

0.840 |

0.882 |

0.780 |

0.909 |

0.749 |

0.698 |

0.747 |

0.064 |

0.921 |

Table 4.

Average Recall of masks on different test sets of the four models. The patterns are similar to those of Average Precision, demonstrating that the training and the models are well-balanced in finding more relevant instances and reducing more irrelevant instances.

Table 4.

Average Recall of masks on different test sets of the four models. The patterns are similar to those of Average Precision, demonstrating that the training and the models are well-balanced in finding more relevant instances and reducing more irrelevant instances.

| segmentation |

AR (maxDets=100,300,1000) |

| |

val |

test |

v1 |

v2c |

v3m |

v3m-a |

v3m-cd |

v3m-cs |

v4sd |

| Mask-RCNN [12] |

0.872 |

0.908 |

0.752 |

0.892 |

0.899 |

0.869 |

0.877 |

0.511 |

0.864 |

| YOLACT [15] |

0.877 |

0.875 |

0.773 |

0.917 |

0.759 |

0.791 |

0.725 |

0.1 |

0.890 |

| SOLOv2 [16] |

0.910 |

0.912 |

0.800 |

0.917 |

0.828 |

0.764 |

0.855 |

0.152 |

0.940 |

| SOLOv2-light [16] |

0.883 |

0.913 |

0.780 |

0.908 |

0.807 |

0.789 |

0.818 |

0.109 |

0.934 |

Table 5.

Examples of visualized results on test set v1, v2c, v3ma, and v3mcd.

Table 6.

Examples of visualized results on test set v3mcs and v4sd, on a recorded sequence, and directly from a real-time camera input.

Table 7.

Inference speed of the four models running on self-recorded sequences or with a Realsense D435i camera, evaluated by frames per second (FPS).

Table 7.

Inference speed of the four models running on self-recorded sequences or with a Realsense D435i camera, evaluated by frames per second (FPS).

| |

Mask-RCNN |

YOLACT |

SOLOv2 |

SOLOv2-light |

| sequence |

4.62 |

5.54 |

4.29 |

6.00 |

| camera |

2.67 |

4.40 |

1.63 |

3.41 |

Table 8.

Evaluation of reconstructed objects of each class using the Chamfer Distance metric. A smaller Chamfer distance indicates a more accurate reconstruction.

Table 8.

Evaluation of reconstructed objects of each class using the Chamfer Distance metric. A smaller Chamfer distance indicates a more accurate reconstruction.

| |

flat |

strip |

stack |

fold-2 |

fold-4 |

fold-s |

desk |

| Chamfer distance |

0.005761 |

0.000670 |

0.000051 |

0.000156 |

0.000100 |

0.000084 |

0.000166 |

Table 9.

Example visualizations of the reconstructed mesh from DeepSDF.

Table 10.

Visualizations of the integrated SLAM running with a Realsense D435i camera.

Table 11.

Speed of each model evaluated by frames per second (FPS) with comparison to their original models.

Table 11.

Speed of each model evaluated by frames per second (FPS) with comparison to their original models.

| CAPE [10] |

300 |

YOLACT |

4.40 |

|

|

| with only plane thread |

1.77 |

with only object thread |

0.69 |

with both integrated |

0.54 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).