Submitted:

17 October 2024

Posted:

18 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

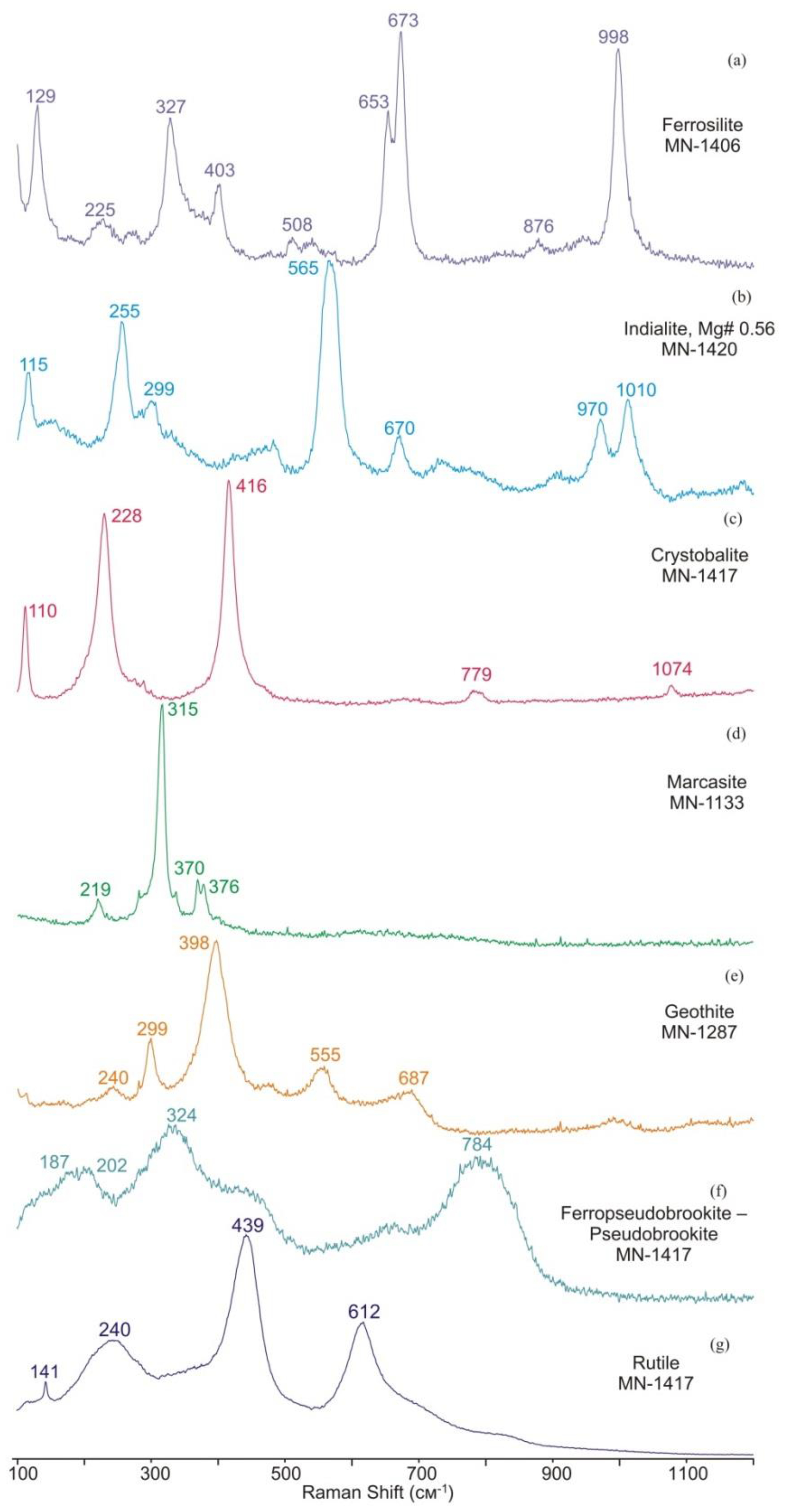

3.1. Identification of Minerals

3.2. Reduced Mineral Assemblages in Rocks of the Nyalga CM Complex

3.3. Reduced Mineral Assemblages in Rocks of the Khamaryn–Khural–Khiid Complex

4. Discussion

4.1. Formation of Melilite-Nepheline Paralava: Conditions and Processes

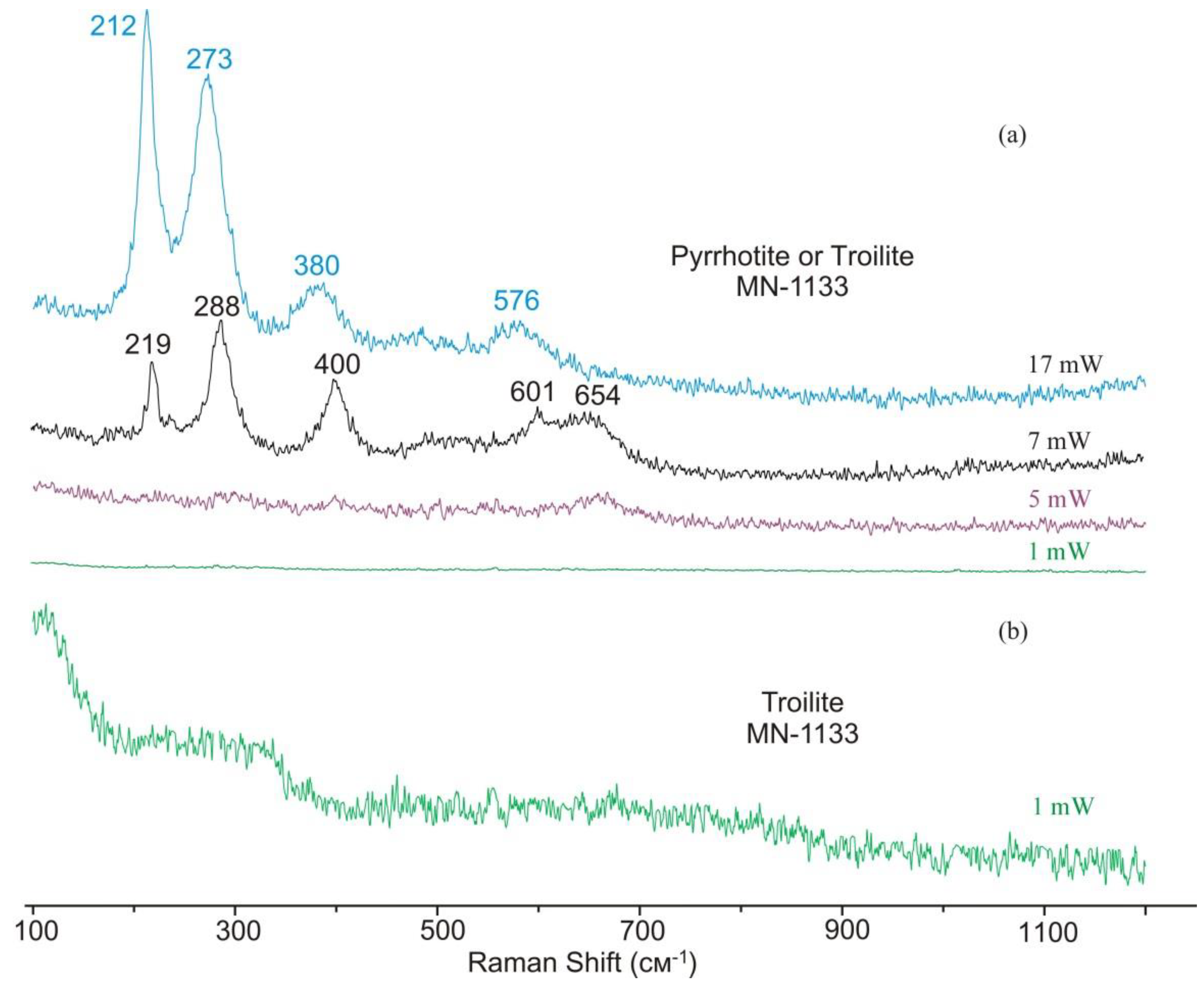

4.3. Troilite with Inclusion of Metallic Iron and Pyrrhotite

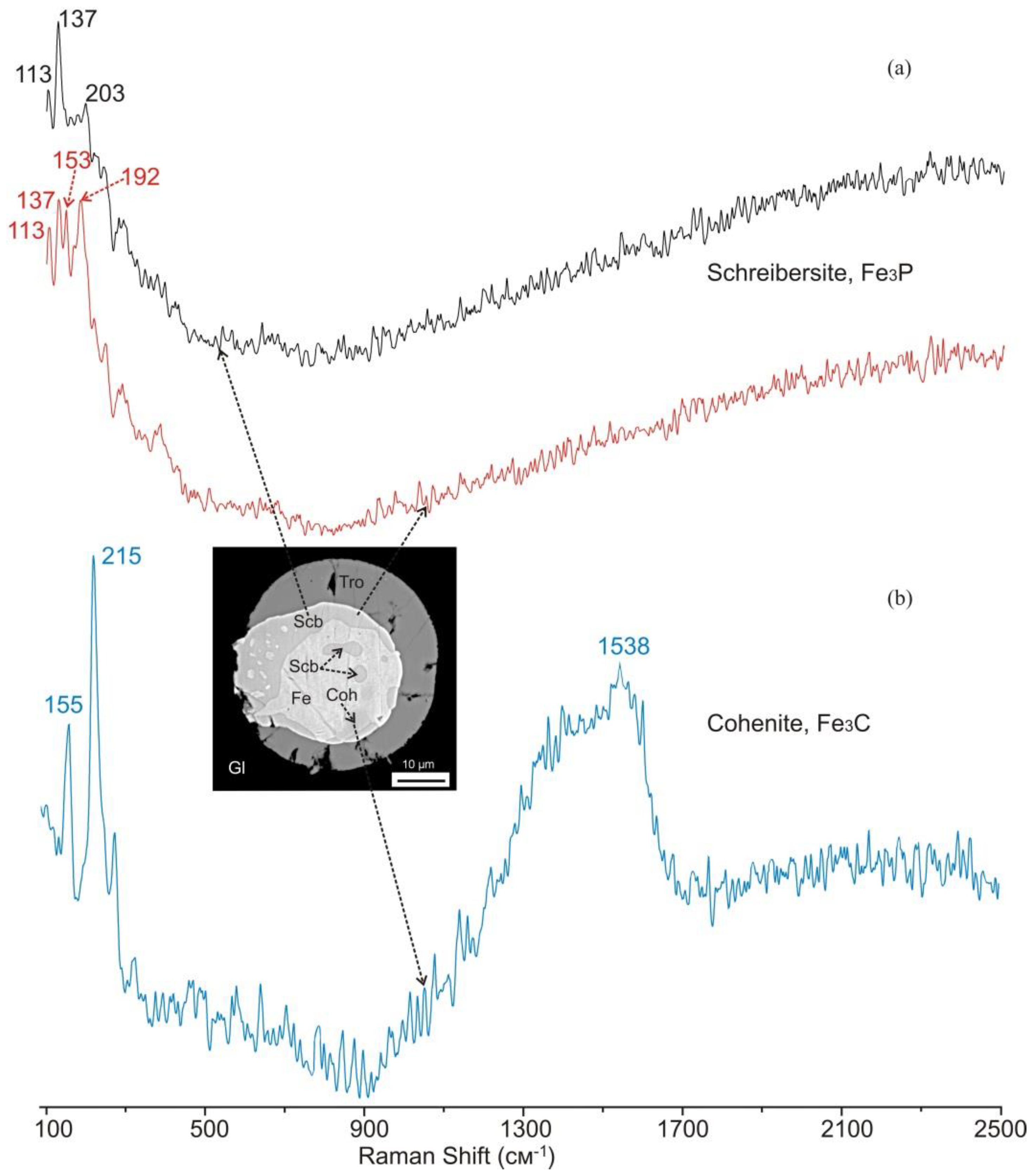

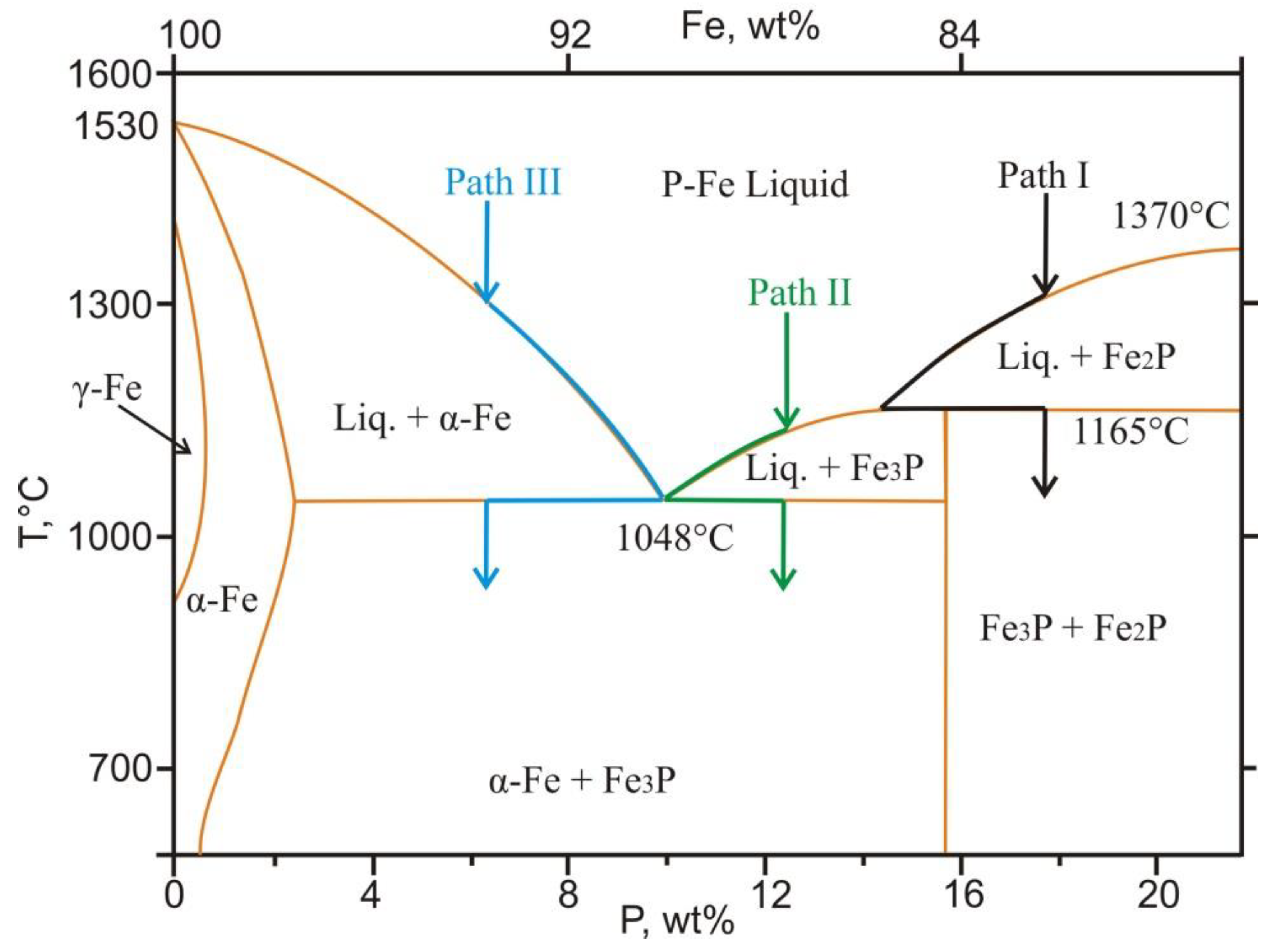

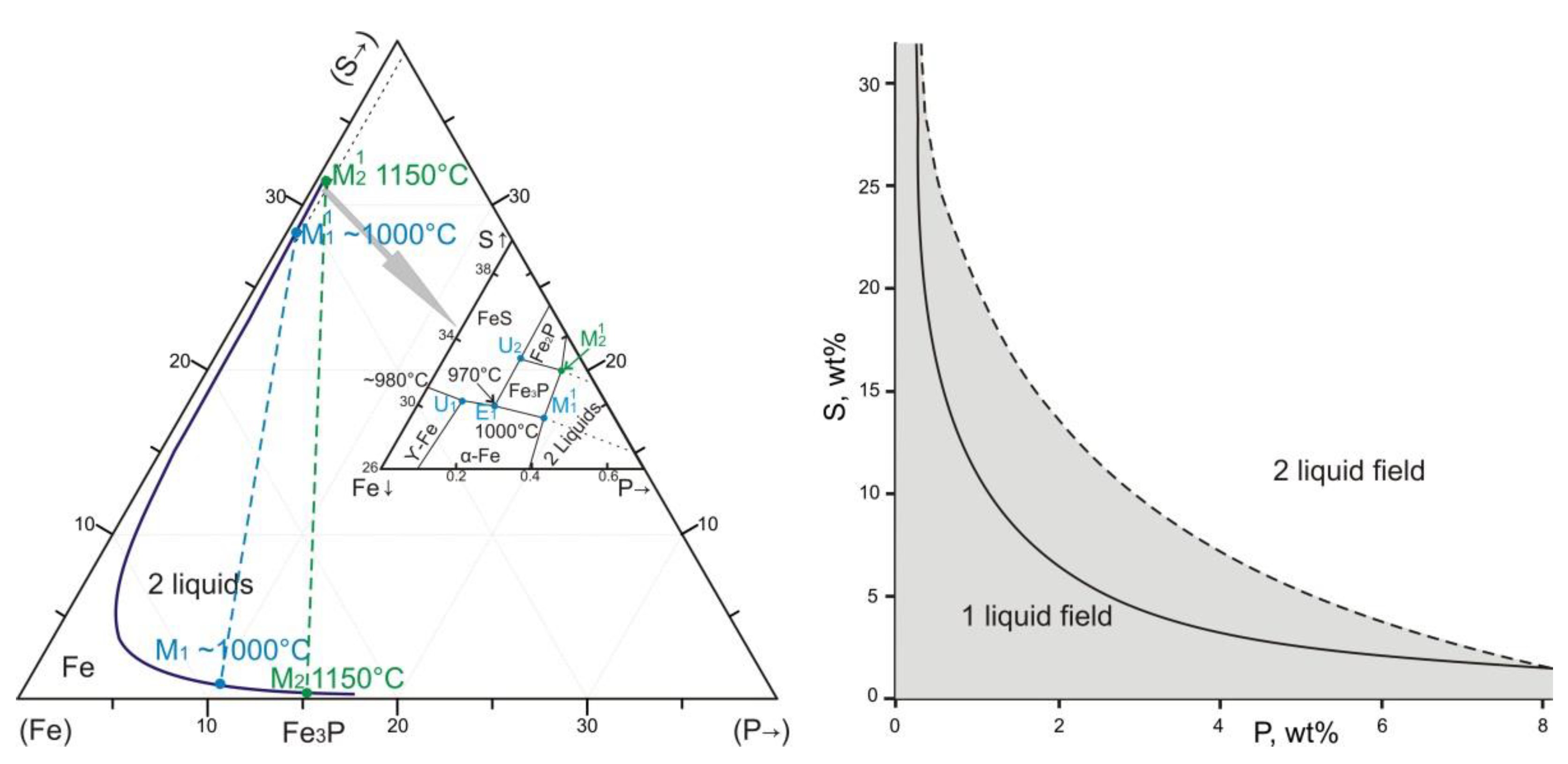

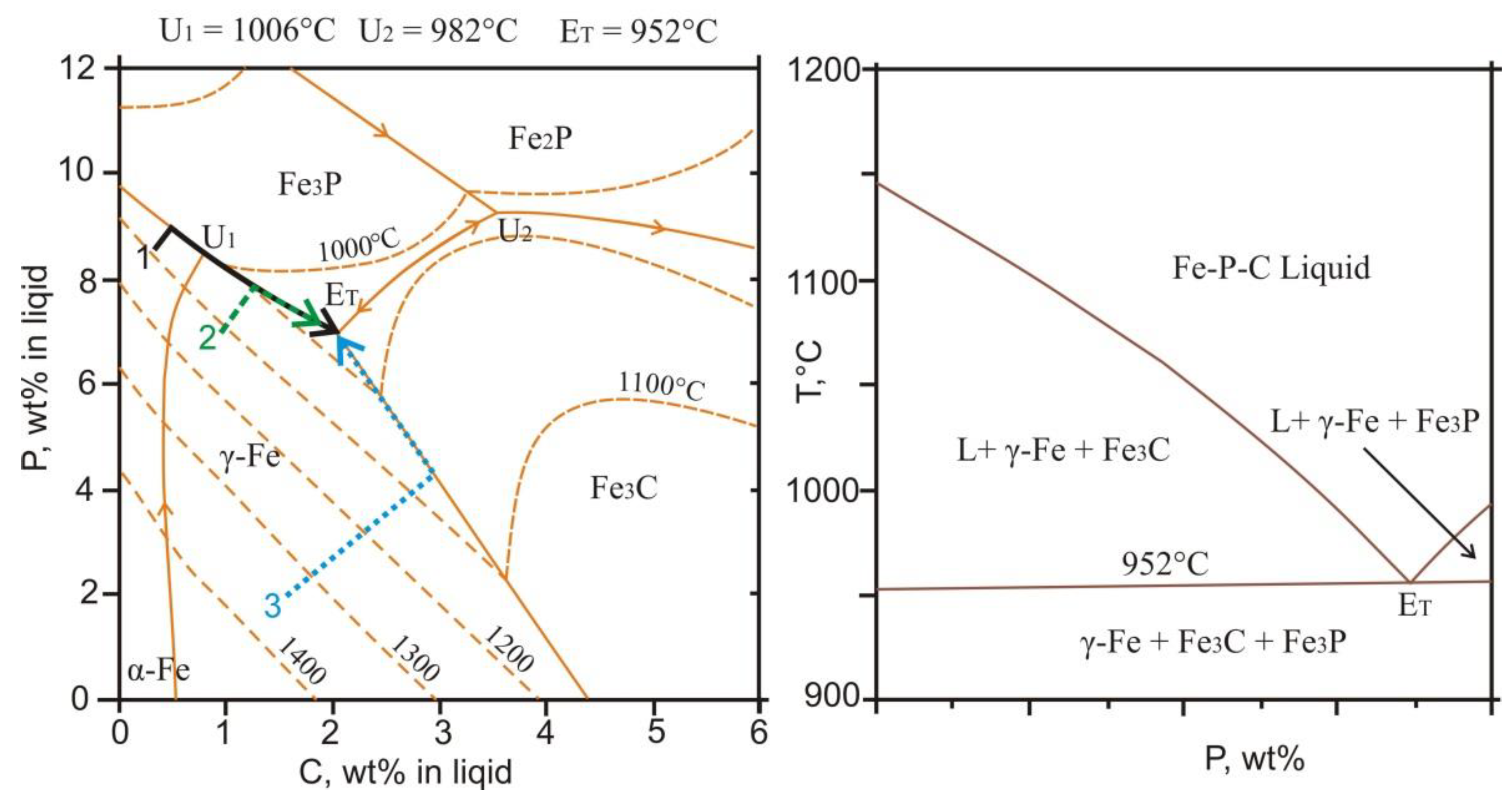

4.4. Mineral Assemblages with Iron Phosphides

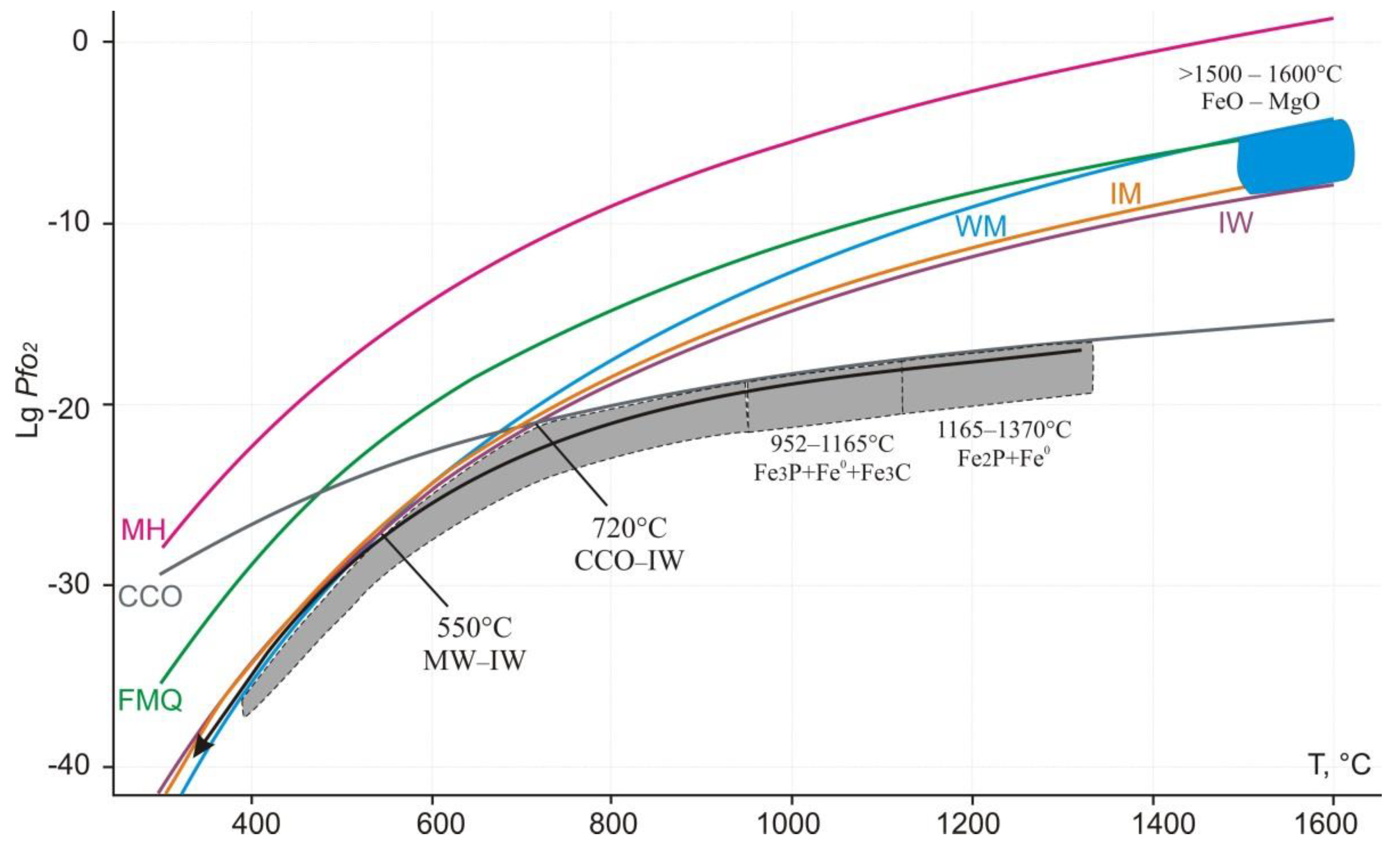

4.5. Formation Conditions of Reduced Mineral Assemblages

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peretyazhko, I.S.; Savina, E.A.; Khromova, E.A. Minerals of the rhönite-kuratite series in paralavas from a new combustion metamorphic complex of Choir–Nyalga Basin (Central Mongolia): Chemistry, mineral assemblages, and formation conditions. Min. Mag. 2017, 81, 949–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretyazhko, I.S.; Savina, E.A.; Khromova, E.A.; Karmanov, N.S.; Ivanov, A.V. Unique clinkers and paralavas from a new Nyalga combustion metamorphic complex in central Mongolia: Mineralogy, geochemistry, and genesis. Petrology 2018, 26, 181–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savina, E.A.; Peretyazhko, I.S.; Khromova, E.A.; Glushkova, V.E. Melted rocks (clinkers and paralavas) of Khamaryn-Khural-Khiid combustion metamorphic complex in Eastern Mongolia: Mineralogy, geochemistry and genesis. Petrology 2020, 28, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savina, Е.А.; Peretyazhko, I.S. Cristobalite Clinker and Paralavas of Ferroan and Melilite–Nepheline Types in the Khamaryn-Khural–Khiid Combustion Methamorphic Complex, East Mongolia: Formation Conditions and Processes. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2023, 64, 1408–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretyazhko, I.S.; Savina, E.A. Melting processes of pelitic rocks in combustion metamorphic complexes of Mongolia: mineral chemistry, Raman spectroscopy, formation conditions of mullite, silicate spinel, silica polymorphs, and cordierite-group minerals. Geoscience 2023, 13, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretyazhko, I.S.; Savina, E.A.; Khromova, E.A. Low–pressure (> 4 MPa) and high–temperature (> 1250°C) incongruent melting of marly limestone: formation of carbonate melt and melilite–nepheline paralava in the Khamaryn–Khural–Khiid combustion metamorphic complex, East Mongolia. Contrib. Miner. Petrol. 2021, 176, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glushkova, V.E.; Peretyazhko, I.S.; Savina, E.A.; Khromova, E.A. Olivine-group minerals in melilite-nepheline paralava of combustion metamorphic complexes in Mongolia. Zap. Ross. Mineral. Obs. 2023, 1, 61–77. (in Russian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glushkova, V.E.; Peretyazhko, I.S.; Savina, E.A.; Khromova, E.A. Rock-forming minerals in paralava of combustion metamorphic complexes in Mongolia. Zap. Ross. Mineral. Obs. 2023, 4, 65–83. (in Russian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrent’ev, Yu.G.; Karmanov, N.S.; Usova, L.V. Electron probe microanalysis of minerals: Microanalyzer or scanning electron microscope ? Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2015, 56, 1154–1161. (in Russian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretyazhko, I.S. CRYSTAL – applied software for mineralogist, petrologist, and geochemists [in Russian]. Zap. Ross. Mineral. Obs. 1996, 3, 141–148. (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Shendrik, R.Y.; Plechov, P.Y.; Smirnov, S.Z. ArDI – the system of mineral vibrational spectroscopy data processing and analysis. New Data on Minerals 2024, 58, 2–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, B.; Downs, R.T.; Yang, H.; Stone, N. The power of databases: The RRUFF project. In Highlights in Mineralogical Crystallography. Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2016; pp. 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Yi.; Xu Tang, Xu.; Lixin Gu, L.; Yuan, J.; Su, W.; Tian, H.; Luo, H.; Cai, S.; Sridhar Komarneni, S. Thermally induced phase transition of troilite during micro-raman spectroscopy analysis. Iracus 2023, 390, 115299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

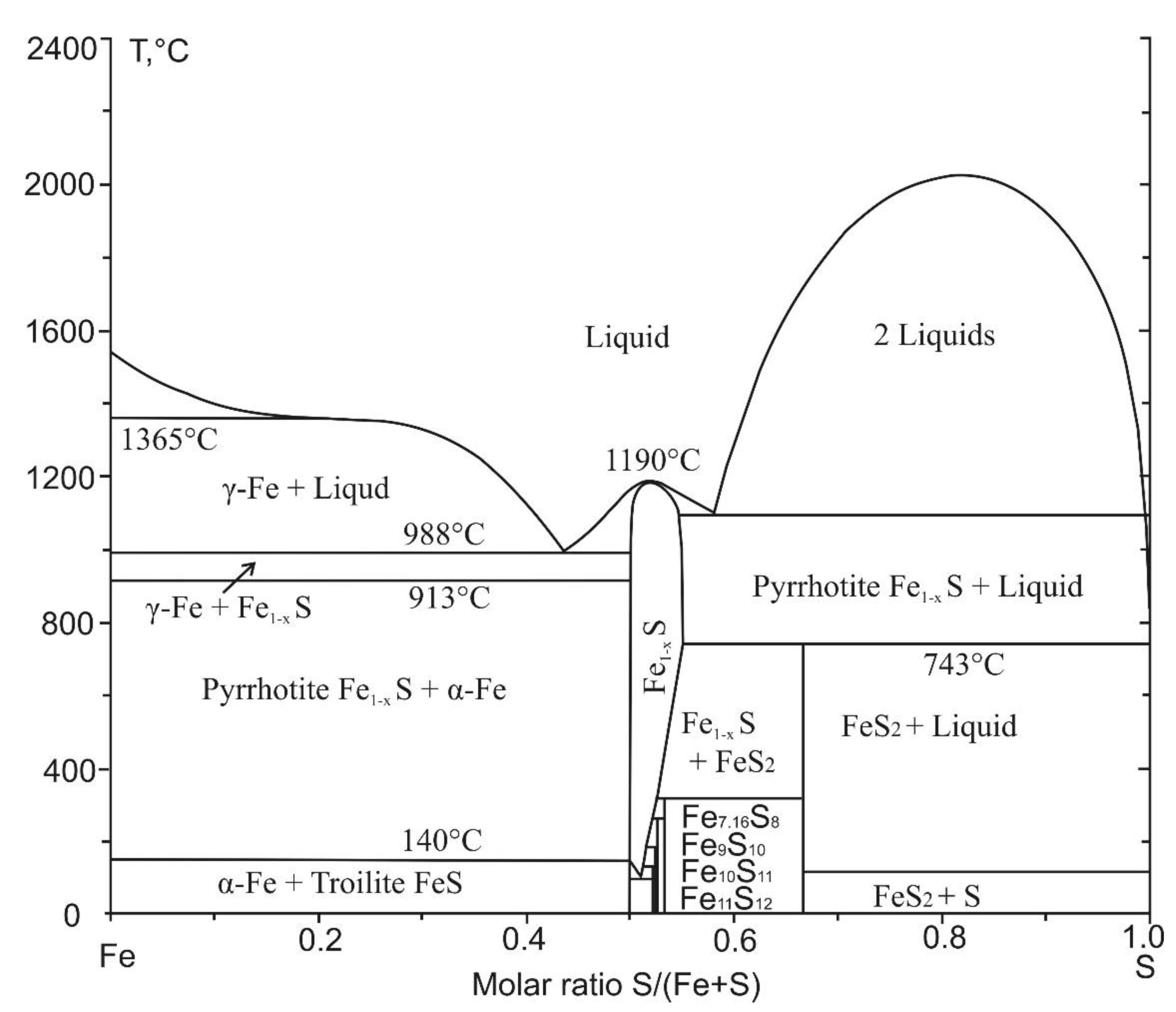

- Walder, P.; Pelton, A.D. Thermodynamic Modeling of the Fe-S System. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2005, 26, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheshin, D.; Decretov, S.A. Critical Assessment and Thermodynamic Modeling of the Fe-O-S System. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2015, 36, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirim, C.; Pasek, M.A.; Sokolov, D.A.; Sidorov, A.N.; Gann, R.D.; Orlando, T.M. Investigation of schreibersite and intrinsic oxidation products from Sikhote-Alin, Seymchan, and Odessa meteorites and Fe3P and Fe2NiP synthetic. Geoch. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 140, 2599–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, X. Fabrication of Fe/Fe3C@porous carbon sheets from biomass and their application for simultaneous reduction and adsorption of uranium(VI) from solution. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2014, 1, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

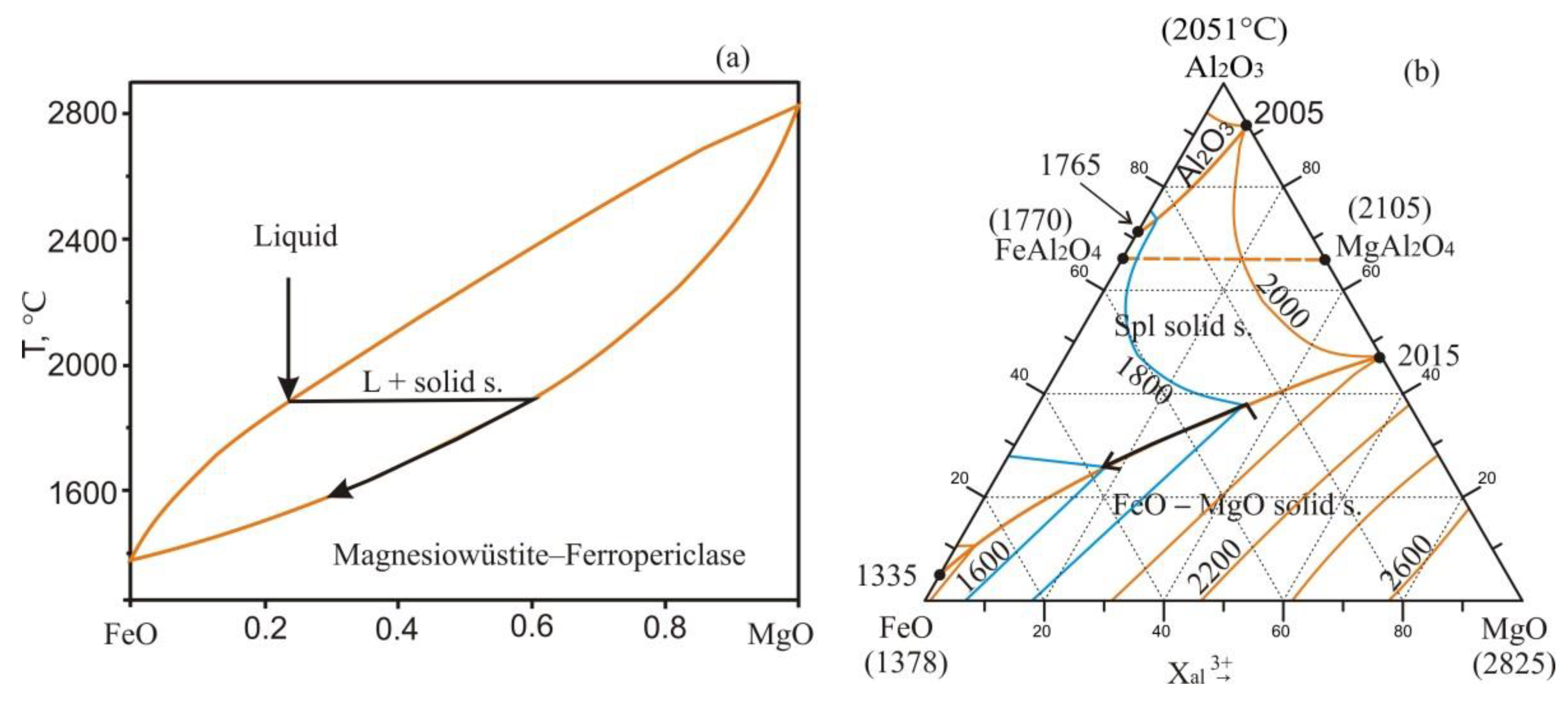

- Bina, C.R. Lower mantle mineralogy and the geophysical perspective. In Ultrahigh Pressure Mineralogy: Physics and Chemistry of the Earth's Deep Interior. Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2019 205–240.

- Kiseeva, E.S.; Korolev, N.; Koemets, I.; Zedgenizov, D.A.; Unitt, R.; McCammon, C.; Aslandukova, A.; Khandarkhaeva, S.; Fedotenko, T.; Glazyrin, K.; Bessas, D.; Aprilis, G.; Chumakov, A.I.; Kagi, H.; Dubrovinsky, L. Subduction-related oxidation of the sublithospheric mantle evidenced by ferropericlase and magnesiowüstite diamond inclusions. Nature Comm. 2021, 13, 7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiocchi, M.; Caucia, F.; Merli, M.; Prella, D.; Ungaretti, L. Crystal-chemical reasons for the immiscibility of periclase and wüstite under lithospheric P, T conditions. Eur. J. Mineral. 2001, 13, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupitsin, A.A.; Yas’ko, S.V.; Bychinsky, V.A.; Peretyazhko, I.S.; Glushkova, V.E. Thermodynamic assessment of the phase diagrams of calcite and CaO–CaCO3 system. Materialia 2024, 34, 102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoilova, O.; Markovets, L. Thermodynamic Modeling of Phase Equilibria in the FeO-MgO-Al2O3 System. Materials Science Forum 2020, 989, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, H.; Pfaff, W. Das system eisen(II)–oxyd–magnesiumoxyd und seine verteilungsgleichgewichte mit flüssigem eisen bei 1520 bis 1750 °C. Arch. Eisenhüttenwes 1961, 32, 741–751. (in German). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheel, R. Gleichgewichte im system CaO–MgO–FeOn bei gegenwart von metallischem eisen, Sprechsaal für Keramik, Glas. Baustoffe 1975, 108, 685–686. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Vereshchagin, O.S.; Khmelnitskaya, M.O.; Murashko, M.N.; Vapnik, Y.; Zaitsev, A.N.; Vlasenko, N.S.; Shilovskikh, V.V.; Britvin, S.N. Reduced mineral assemblages of superficial origin in west-central Jordan. Mineral. Petrol. 2024, 118, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereshchagin, O.S.; Khmelnitskaya, M.O.; Kamaeva, L.V.; Vlasenko, N.S.; Pankin, D.V.; Bocharov, V.N.; Britvin, S.N. Telluric iron assemblages as a source of prebiotic phosphorus on the early Earth: Insights from Disko Island, Greenland. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britvin, S.N.; Murashko, M.N.; Vapnik, Y.; Polekhovsky, Y.S.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Vereshchagin, O.S.; Shilovskikh, V.V.; Krzhizhanovskaya, M.G. Negevite, the pyrite-type NiP2, a new terrestrial phosphide. Am. Mineral. 2020, 105, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britvin, S.N.; Rudashevsky, N.S.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Burns, P.; Polekhovsky, Y.S. Allabogdanite, (Fe,Ni)2P, a new mineral from the Onello meteorite: the occurrence and crystal structure. Am. Mineral. 2002, 87, 1245–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britvin, S.N.; Shilovskikh, V.V.; Pagano, R.; Vlasenko, N.S.; Zaitsev, A.N.; Krzhizhanovskaya, M.G.; Lozhkin, M.S.; Andrey, A.; Zolotarev, A.A.; Gurzhiy, V.V. 2019. Allabogdanite, the high-pressure polymorph of (Fe,Ni)2P, a stishovite-grade indicator of impact processes in the Fe–Ni–P system. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britvin, S.N.; Vapnik, Y.; Polekhovsky, Y.S.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Krzhizhanovkaya, M.G.; Gorelova, L.A.; Vereshchagin, O.S.; Shilovskikh, V.V.; and Zaitsev, A.N. Murashkoite, FeP, a new terrestrial phosphide from pyrometamorphic rocks of the Hatrurim Formation, South Levant. Mineral. Petrol. 2019, 113, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britvin, S.N.; Murashko, M.N.; Vapnik, Ye.; Polekhovsky, Yu.S.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Vereshchagin, O.S.; Vlasenko, N.S.; Shilovskikh, V.V.; Zaitsev, A.N. Zuktamrurite, FeP2, a new mineral, the phosphide analogue of löllingite, FeAs2. Physics and Chemistry of Minerals 2019, 46, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britvin, S.N.; Vereshchagin, O.S.; Shilovskikh, V.V.; Krzhizhanovskaya, M.G.; Gorelova, L.A.; Vlasenko, N.S.; Pakhomova, A.S.; Zaitsev, A.N.; Zolotarev, A.A.; Bykov, M.; Lozhkin, M.S.; Nestola, F. Discovery of terrestrial allabogdanite (Fe,Ni)2P, and the effect of Ni and Mo substitution on the barringerite allabogdanite high-pressure transition. Am. Mineral. 2021, 106, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britvin, S.N.; Murashko, M.N.; Vapnik, Ye.; Polekhovsky, Yu.S.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Krzhizhanovskaya, M.G.; Vereshchagin, O.S.; Shilovskikh, V.V.; Vlasenko, N.S. Transjordanite, Ni2P, a new terrestrial and meteoritic phosphide, and natural solid solutions barringerite–transjordanite (hexagonal Fe2P–Ni2P). Am. Mineral. 2020, 105, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britvin, S.N.; Murashko, M.N.; Vapnik, Ye.; Polekhovsky, Yu.S.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Vereshchagin, O.S.; Shilovskikh, V.V.; Vlasenko, N.S.; Krzhizhanovskaya, M.G. Halamishite, Ni5P4, a new terrestrial phosphide in the Ni–P system. Physics and Chemistry of Minerals 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britvin, S.N.; Murashko, M.N.; Krzhizhanovskaya, M.G.; Vereshchagin, O.S.; Vapnik, Ye.; Shilovskikh, V.V.; Lozhkin, M.S.; Obolonskaya, E.V. Nazarovite, Ni12P5, a new terrestrial and meteoritic mineral structurally related to nickelphosphide, Ni3P. Am. Mineral. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britvin, S.N.; Murashko, M.N.; Vereshchagin, O.S.; Vapnik, Ye.; Shilovskikh, V.V.; Vlasenko, N.S.; Permyakov, V.V. Expanding the speciation of terrestrial molybdenum: discovery of polekhovskyite, MoNiP2, and insights into the sources of Mo-phosphides in the Dead Sea Transform area. Am. Mineral. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galuskin, E.V.; Kusz, J.; Galuskina, I.O.; Książek, M.; Vapnik, Y.; Zieliński, G. Discovery of terrestrial andreyivanovite, FeCrP, and the effect of Cr and V substitution on the low-pressure barringerite-allabogdanite transition. Am. Mineral. 2023, 108, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dera, P.; Lavina, B.; Borkowski, L.A.; Prakapenka, V.B.; Sutton, S.R.; Rivers, M.L.; Downs, R.T.; Boctor, N.Z.; Prewitt, C.T. Structure and behavior of the barringerite Ni end-member, Ni2P, at deep Earth conditions and implications for natural Fe-Ni phosphides in planetary cores. J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114, B03201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litasov, K.D.; Bekker, T.B.; Sagatov, N.E.; Gavryushkin, P.N.; Krinitsyn, P.G.; Kuper, K.E. (Fe,Ni)2P allabogdanite can be an ambient pressure phase in iron meteorites. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 8956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, S.; Singh, P.; Sarkar, A.; Viswanathan, G.; Kolen’ko, Yu.V.; Mudryk, Y.; Johnson, D.D, .; Kovnir, K. Enhancing Properties with Distortion: A Comparative Study of Two Iron Phosphide Fe2P Polymorphs. Chem. Mat. 2024, 36, 1665–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, J.; Vassilev, G. Thermodynamic Description of Ternary Fe-X-P Systems. Part 1: Fe-Cr-P. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 2014, 35, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.; Drake, M.J. Experimental investigations of trace element fractionation in iron meteorites, II: The influence of sulfur. Geoch. Cosmochim. Acta 1983, 47, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, V. The Fe-P-S System. In Phase Diagrams of Ternary Iron Alloys 1988, 2, 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Chabot, N.L.; Drake, M.J. Crystallization of magmatic iron meteorites: The effects of phosphorus and liquid immiscibility. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 2000, 35, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.H.; Oh, C.S.; Lee, D.N. Thermodynamic Assessment of the Fe-C-P System. Zeitschrift für Metallkunde 2000, 91, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurmann, E.; Hensgen, U.; Schweinichen, J. Melt Equilibrium of the Ternary Systems Fe-C-Si and Fe-C-P. Geissereiforsch. 1984, 36, 121–129. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Sokol, E.V.; Maksimova, N.V.; Nigmatulina, E.N.; Sharygin, V.V.; Kalugin, V.M. (Eds.). Combustion Metamorphism 2005, Izd. SO RAN, Novosibirsk. (in Russian).

| Major components, wt% | |||||||||||||||

| W-P | Tro | Cub | Nng | Fe0 | Kam | Tae | Coh | Fe2P | Fe3P | Fe4P | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| Mg | 57.82* | 28.21* | |||||||||||||

| Mn | 0.41* | 0.56* | 0.35 | 29.11 | |||||||||||

| Fe | 42.21* | 71.90* | 62.63 | 39.59 | 35.14 | 95.05 | 88.32 | 73.25 | 92.99 | 74.90 | 84.64 | 81.03 | 71.29 | 60.91 | 86.00 |

| Ni | 0.98 | 21.08 | 1.48 | 11.74 | 20.39 | 0.76 | |||||||||

| Co | 2.50 | 2.62 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.77 | 1.83 | 2.63 | ||||||||

| Cu | 25.38 | 0.79 | 0.40 | ||||||||||||

| As | 0.44 | 1.27 | |||||||||||||

| P | 0.70 | 0.66 | 23.66 | 15.10 | 15.20 | 14.29 | 14.93 | 10.65 | |||||||

| S | 36.98 | 33.78 | 37.06 | 0.79 | 0.30 | 0.30 | |||||||||

| C | 6.67** | ||||||||||||||

| Total | 100.45 | 100.67 | 99.61 | 100.08 | 101.31 | 96.75 | 100.02 | 98.62 | 99.66 | 99.23 | 100.27 | 98.50 | 99.45 | 99.15 | 97.41 |

| Chemical formula (apfu) ** | |||||||||||||||

| Mg | 0.707 | 0.410 | |||||||||||||

| Mn | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.017 | 0.458 | |||||||||||

| Fe | 0.290 | 0.585 | 0.986 | 1.947 | 0.544 | 0.987 | 0.879 | 0.755 | 3 | 1.901 | 3.006 | 2.931 | 2.593 | 2.221 | 4.059 |

| Ni | 0.046 | 0.062 | 0.207 | 0.051 | 0.406 | 0.707 | 0.034 | ||||||||

| Co | 0.024 | 0.026 | 0.016 | 0.024 | 0.026 | 0.063 | 0.091 | ||||||||

| Cu | 1.097 | 0.007 | 0.004 | ||||||||||||

| As | 0.003 | 0.010 | |||||||||||||

| P | 0.013 | 0.012 | 1.083 | 0.969 | 0.991 | 0.937 | 0.981 | 0.906 | |||||||

| S | 1.014 | 2.893 | 0.999 | 0.014 | |||||||||||

| C | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Sum | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).