1. Introduction

Graphs are widely regarded as one of the most versatile data structures across numerous disciplines for modeling pairwise relationships. A prominent challenge in graph theory is solving the maximum matching problem, particularly in bipartite graphs, where the objective is to identify the largest set of non-overlapping edges. While classical algorithms such as Edmonds’ Blossom algorithm and the Hopcroft-Karp algorithm [

1,

2] have proven effective, they often face limitations when dealing with larger or more complex graphs. As datasets continue to expand in size and intricacy, the demand for more scalable and generalizable solutions has become increasingly apparent.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) offer a promising approach by learning from graph-structured data and leveraging the inherent relationships within graphs [

3,

4]. This paper introduces HybridGNN, a model that integrates GAT [

3] and SAGE [

4] layers, further enhanced through self-supervised learning techniques. These techniques allow the model to be trained without the need for manually labeled datasets, making it a flexible solution for large-scale graph-based tasks.

Furthermore, earlier research on graph diagnosability and connectivity, such as the work on bubble-sort star graphs and leaf-sort graphs [

5,

6], highlights the critical importance of robust graph structures in solving complex graph-based problems. These studies provide foundational insights into the fault tolerance and structural properties of various network configurations, which are closely aligned with the challenges HybridGNN seeks to address.

In addition to these works, advancements in labelings and graph structures, including the edge-magic total labelings of wheels and fans [

7], the constructions of magic and antimagic graph labelings [

8], and the face antimagic labelings of plane graphs [

9], further highlight the role of specialized graph structures in ensuring efficient performance in GNNs. Moreover, studies in applying graph structures to broader machine learning tasks, such as fake news detection [

10], emphasize the versatility of graph models in various domains. Techniques like iMER for entity extraction [

11] also underscore the power of graph-based approaches in structured data extraction, directly relevant to the learning tasks addressed in HybridGNN.

Shohei Satake et al.’s work on explicit non-malleable codes from bipartite graphs [

12] offers another critical perspective, particularly in the context of using bipartite expander graphs for building robust, tamper-resistant communication systems. This is especially relevant in designing algorithms that ensure high reliability, aligning with the bipartite matching challenges addressed by HybridGNN. Their exploration of constructing codes from graph structures further supports the importance of leveraging advanced graph theory techniques for broader computational and communication tasks.

Finally, HybridGNN’s design is inspired by the structural characteristics explored in previous work on center k-ary n-cubes [

13], where the diagnosability and connectivity properties are key to maintaining optimal graph performance. The application of edge-restricted connectivity conditions, as discussed in [

14], highlights the importance of ensuring that graphs remain robust under edge failures, a property that aligns with HybridGNN’s approach to improving fault tolerance in bipartite matching tasks.

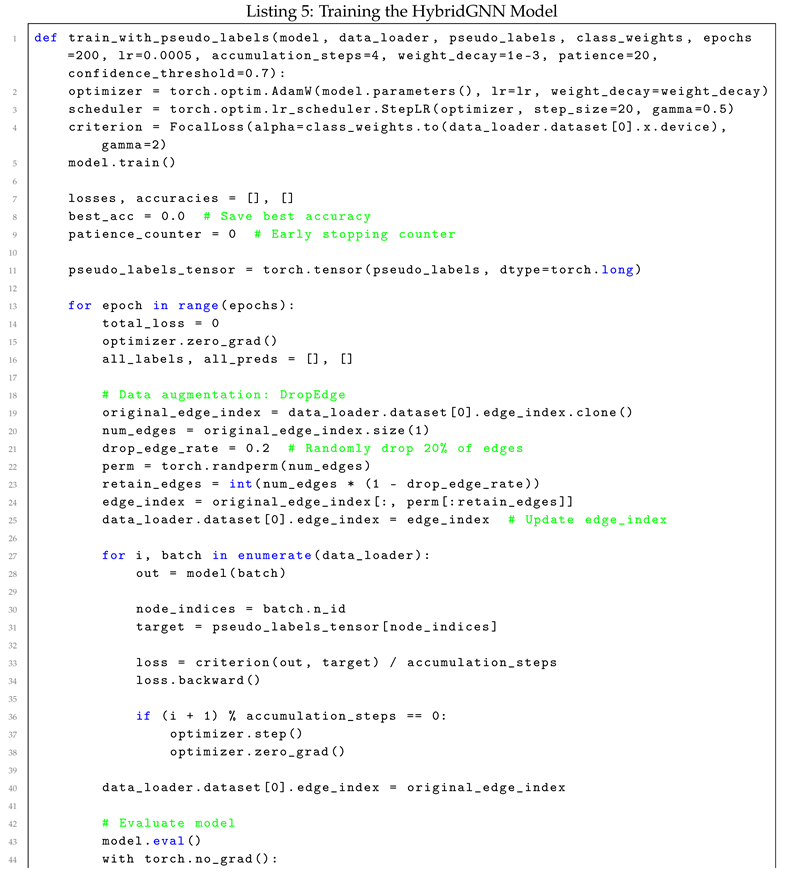

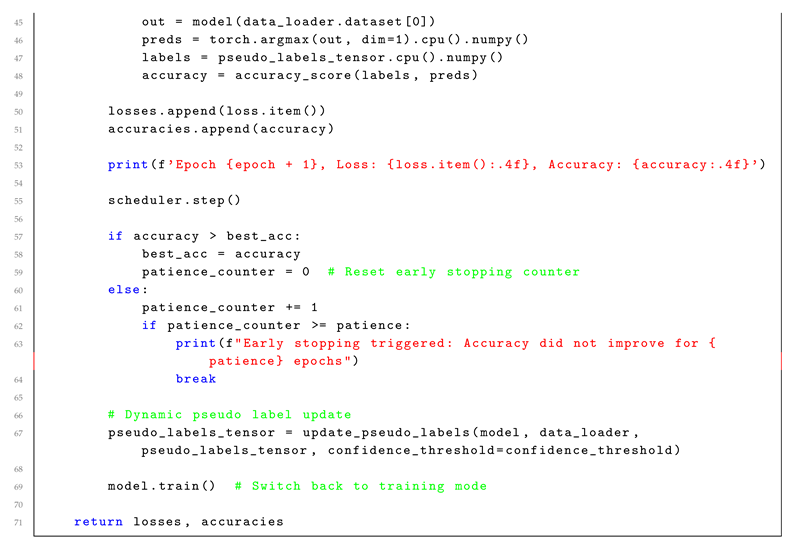

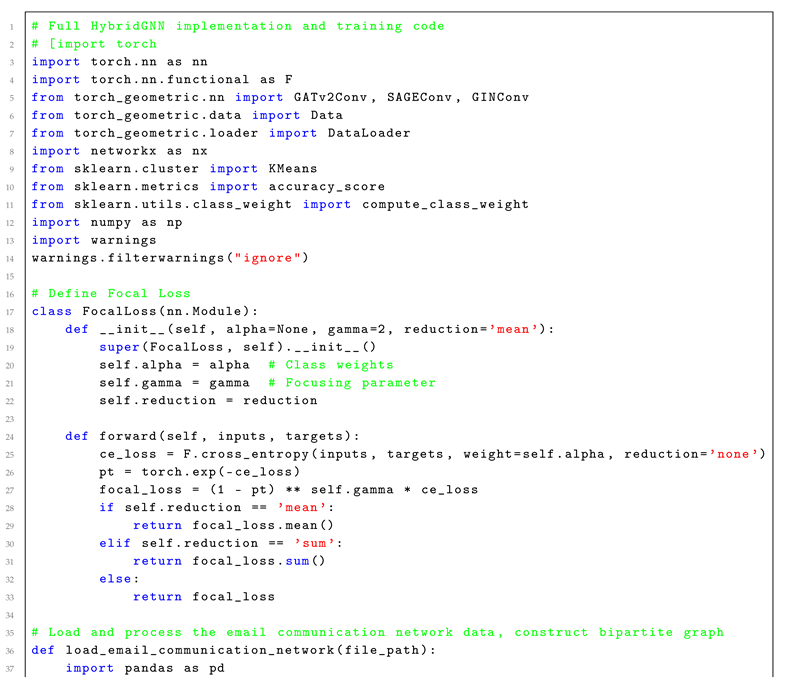

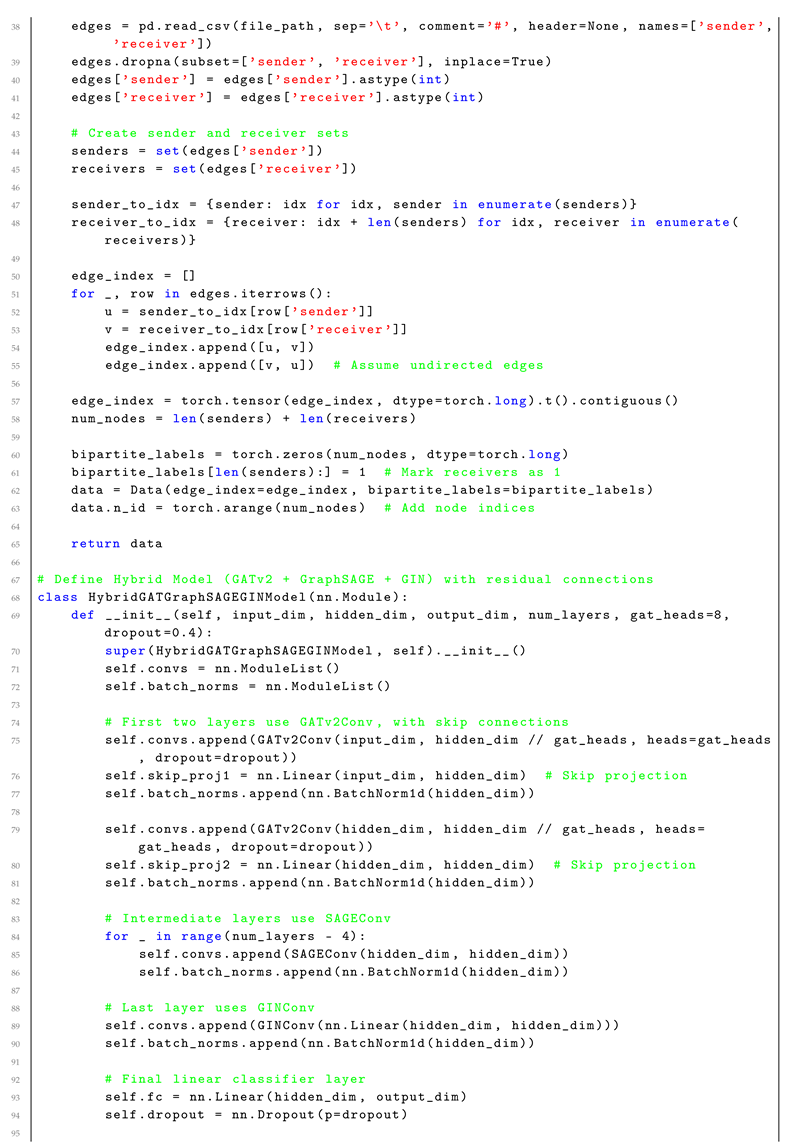

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 covers graph theory fundamentals, particularly bipartite graphs and their relevance in large-scale applications. Section 3 discusses classical and neural approaches to graph matching, with a focus on the limitations of traditional algorithms and the advantages of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). In Section 4, we present the architecture of HybridGNN and the innovations it introduces for solving maximum matching problems. Section 5 explains the self-supervised learning strategies used to train HybridGNN using pseudo-labels. Section 6 outlines regularization and early stopping mechanisms to prevent overfitting, followed by Section 7, which details the dynamic pseudo-label updating method. Section 8 provides the experimental setup, including the dataset and data augmentation techniques. Section 9 presents a time complexity analysis of HybridGNN, breaking down the complexity of its individual layers. Section 10 discusses the results, challenges, and future research directions. Section 11 concludes the paper with final remarks and Section 12 provides the full code implementation for further reproducibility.

2. Graph Theory Fundamentals

2.1. Definitions

Graphs, typically denoted as

, are fundamental data structures composed of a vertex set

V and an edge set

E, with each edge encapsulating a relationship between two distinct entities [

15]. A significant subset of graphs is the class of bipartite graphs, characterized by the partitioning of the vertex set

V into two mutually exclusive subsets

U and

W, where no edges exist between vertices within the same subset [

16]. This inherent structure has applications in numerous fields, including network theory and algorithm design. Subgraphs, a core concept in graph theory, are defined as any subset of vertices and edges that themselves form a graph, preserving the original relationships from the parent graph [

17].

The degree of a vertex, defined as the count of edges incident to it, provides insight into the local connectivity of a graph, while the minimum degree across all vertices represents a key measure of the graph’s overall sparsity or density [

15]. Additionally, the notion of connectivity is vital to understanding graph structure; a graph is said to be connected if there exists a path between every pair of vertices [

16]. In a more granular sense, edge connectivity is defined as the minimum number of edges that must be removed to render the graph disconnected, highlighting its robustness against link failures [

17].

A pivotal challenge in graph theory is solving the maximum matching problem. This problem seeks to identify the largest possible set of non-overlapping edges, particularly in bipartite graphs where such matching maximizes relationships between the two distinct vertex sets [

18]. The ability to efficiently compute maximum matchings in large-scale graphs is critical for applications ranging from resource allocation to network flow optimization.

2.2. Bipartite Graphs in Large-Scale Applications

Bipartite graphs are a cornerstone of many real-world applications, owing to their distinctive structure, which separates the vertex set into two disjoint groups. This partitioning allows for effective modeling of problems where interactions occur between two distinct classes of entities, such as in task scheduling, network flow optimization, and resource allocation [

18]. For example, in scheduling, tasks and resources can be represented as vertices in a bipartite graph, with edges indicating feasible assignments, enabling efficient optimization of the task assignment process [

16].

One of the most well-known algorithms for finding maximum matchings in bipartite graphs is the Hopcroft-Karp algorithm [

2]. This classical algorithm has been widely adopted due to its

time complexity, making it suitable for many medium-sized graph instances. However, as the size and complexity of datasets continue to grow, the performance of classical methods like Hopcroft-Karp begins to degrade, particularly in large-scale graphs where the number of vertices and edges can reach millions [

17]. The inherent computational complexity of these methods becomes a bottleneck, limiting their scalability in modern applications.

To address these limitations, recent research has turned to Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) as a means to generalize and scale bipartite graph algorithms for larger, more complex structures. By leveraging the ability of GNNs to learn from graph-structured data, we can design models that not only retain the combinatorial properties of classical approaches but also adaptively handle large-scale and intricate graph instances [

3]. This research aims to develop a more scalable and robust approach, integrating GNNs to overcome the computational challenges posed by traditional algorithms and ensuring applicability to diverse real-world problems.

3. Classical and Neural Approaches to Graph Matching

Graph matching has been approached from both classical algorithmic perspectives and, more recently, through neural network-based techniques. Classical methods, such as Edmonds’ Blossom Algorithm and the Hopcroft-Karp Algorithm, have long been considered efficient solutions for solving maximum matching problems in general and bipartite graphs, respectively. These algorithms rely on combinatorial optimization and have been extensively used in theoretical applications. However, their scalability is often limited when faced with large and dynamically changing graph structures.

In contrast, the advent of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) has opened up new possibilities for tackling graph matching problems. By utilizing deep learning techniques to learn from graph-structured data, GNNs are capable of generalizing across diverse graph types and efficiently processing large-scale graphs. This shift towards neural approaches represents a promising avenue for overcoming the limitations of classical algorithms, particularly in real-world applications where graphs can be noisy, large, and complex [

3,

19].

3.1. Challenges of Classical Approaches in Graph Matching

Classical algorithms like the Hopcroft-Karp algorithm and Edmonds’ Blossom Algorithm are cornerstone methods for solving the maximum matching problem in bipartite and general graphs, respectively. The Hopcroft-Karp algorithm, known for its efficient time complexity of

, operates by iteratively finding augmenting paths to increase the size of the current matching in bipartite graphs [

2]. Similarly, Edmonds’ Blossom Algorithm solves the more complex case of general graphs by introducing the concept of blossoms to handle odd-length cycles, providing a polynomial-time solution [

1].

Despite their theoretical efficiency, these algorithms face significant challenges when applied to real-world datasets. As graph sizes increase, both algorithms exhibit scaling limitations, particularly with respect to memory usage and processing time. The practical performance of these methods often deteriorates as the graph structure becomes more complex, with millions of vertices and edges [

20]. Furthermore, their reliance on handcrafted optimization procedures limits their ability to generalize across different types of graphs, particularly in dynamic or noisy environments where graph structures may evolve over time.

These limitations have prompted a shift towards more scalable, learning-based methods, particularly Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). By leveraging the inherent structure of graphs, GNNs offer a more flexible framework for tackling large-scale graph matching problems, where traditional approaches fall short [

21].

3.2. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have revolutionized the field of graph representation learning by extending deep learning techniques to graph-structured data. These models, such as Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) introduced by Kipf and Welling [

19], and Graph Attention Networks (GATs) developed by Veličković et al. [

3], have shown remarkable success in tasks like node classification, link prediction, and graph matching. GCNs apply convolutional operations to aggregate information from neighboring nodes, effectively capturing the local structure of graphs, while GATs introduce attention mechanisms that assign different importance weights to different neighbors, allowing the model to focus on the most relevant connections.

The success of these models lies in their ability to learn directly from the graph data, without the need for handcrafted features or complex optimization procedures. GNNs can adapt to different graph structures and scales, making them highly generalizable and efficient even when applied to large-scale, real-world graphs. Moreover, their ability to incorporate both node features and edge relationships enables them to capture complex patterns within the data, making them particularly well-suited for solving challenging graph matching problems [

22].

As graph-based tasks continue to grow in complexity, the application of GNNs to these problems offers a promising path forward. By leveraging the expressive power of neural networks, GNN-based models are capable of solving problems that classical algorithms find intractable, particularly in scenarios involving noisy, dynamic, or large-scale graphs [

21].

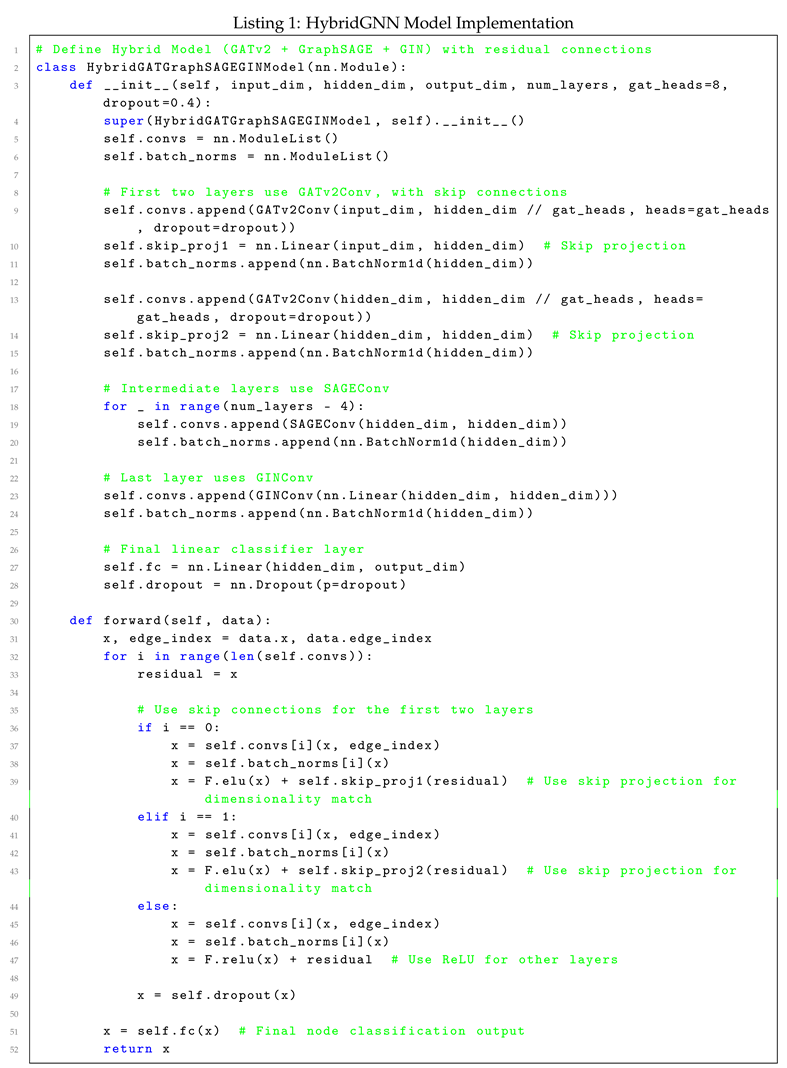

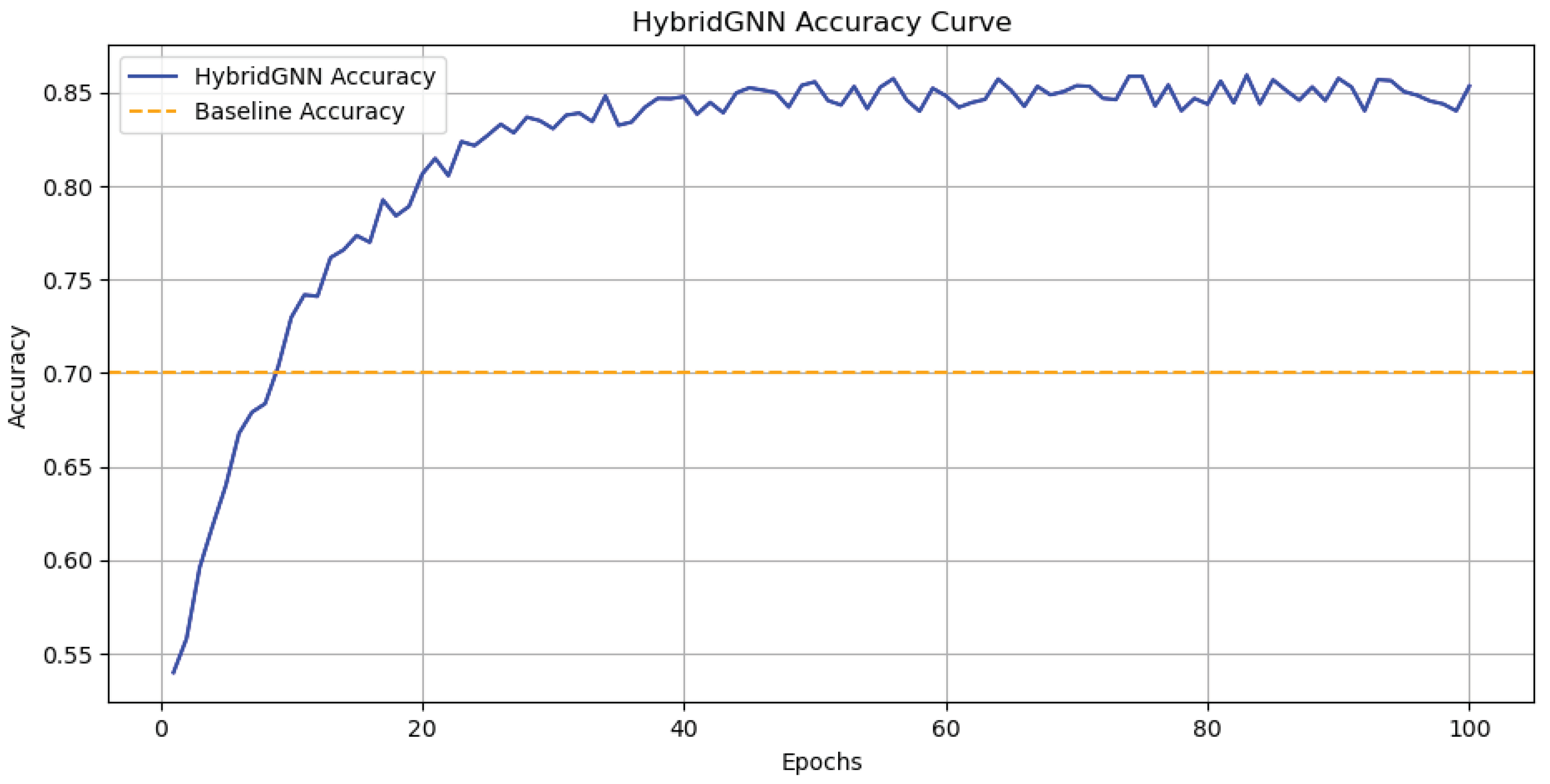

4. HybridGNN: Architectural Design and Innovation

The HybridGNN model is designed to integrate the complementary strengths of Graph Attention Networks (GAT) and GraphSAGE (SAGEConv) layers, enabling it to effectively capture both local node-level relationships and global graph-wide patterns. GATConv layers employ attention mechanisms that assign varying importance to different neighboring nodes, allowing the model to focus on the most relevant connections. This feature is particularly beneficial when dealing with heterogeneous graphs where relationships between nodes may vary significantly [

3].

On the other hand, GraphSAGE layers contribute to the architecture by leveraging inductive learning capabilities, which allow the model to generate node embeddings for unseen nodes during inference [

4]. This inductive nature makes HybridGNN highly scalable, as it can generalize well to larger, evolving graphs without the need to retrain the model each time new data is added. By combining GATConv and SAGEConv, HybridGNN can simultaneously capture both fine-grained and coarse-grained patterns in the graph, making it an ideal solution for complex graph-based tasks such as bipartite matching.

A key innovation in the HybridGNN architecture is the incorporation of the Jumping Knowledge (JK) mechanism, which aggregates representations from multiple layers of the network. Unlike traditional GNNs that rely solely on the final layer’s output, the JK mechanism ensures that both shallow and deep layer representations are utilized, allowing the model to effectively leverage information from various levels of granularity [

23]. This feature is particularly important when addressing graphs with hierarchical structures, where both local and global information are critical for accurate prediction.

In addition, HybridGNN employs mixed precision training and gradient accumulation techniques to optimize memory usage and computational efficiency, especially when working with large-scale graphs. This makes it a scalable and efficient solution for real-world applications where resource limitations and data size present significant challenges.

4.1. Architectural Components of HybridGNN

The HybridGNN model is specifically designed to address the intricate relationships present in bipartite graphs. It incorporates several key components to effectively capture and process graph-structured data:

-

Graph Attention Networks v2 (GATv2) The Graph Attention Network v2 (GATv2) is an enhanced version of the original GAT model, designed to overcome certain limitations, particularly those associated with the non-negative attention coefficients in GAT. GATv2 introduces a more flexible attention mechanism, allowing the attention coefficients to assume both positive and negative values. This enhancement enables GATv2 to more effectively capture complex relationships between nodes, even in noisy or highly intricate graphs, thereby improving overall task performance.

The core operation of GATv2 is represented as follows:

where

and

represent the feature vectors of nodes

i and

j,

is a learnable weight matrix, and

represents the attention mechanism. Unlike the original GAT, GATv2 allows for negative attention scores, significantly increasing its expressiveness and enabling the model to better handle complex and non-linear interactions in graph structures. This improvement is crucial for tasks that require a nuanced understanding of node relationships, especially in noisy or complex graph environments.

SAGEConv Layers: By aggregating information from neighboring nodes, the SAGEConv layers generate more comprehensive node representations, facilitating a deeper understanding of both local and global graph structures [

4]. This aggregation process enables the model to generalize effectively across diverse graph topologies.

-

Graph Isomorphism Networks (GIN) The Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) is a highly expressive GNN architecture specifically designed to capture detailed structural information from graphs by mimicking the Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) graph isomorphism test [

21]. GIN achieves this by aggregating node features from neighboring nodes using a learned weighted sum, making it particularly effective for tasks requiring a fine-grained understanding of graph structure. This high level of discriminative power makes GIN especially suitable for graph matching tasks and other applications where subtle structural differences in the graph are critical.

The GIN aggregation rule is defined as:

where

represents the feature of node

v at the

k-th layer,

is a learnable parameter, and

denotes the set of neighboring nodes of

v. The Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) in GIN plays a crucial role in enhancing the model’s expressiveness, enabling it to capture complex and intricate graph structures. This architecture’s ability to differentiate between non-isomorphic graphs gives it a significant advantage in learning highly discriminative graph representations.

-

Focal Loss

Focal Loss is a modified version of the standard cross-entropy loss function, specifically designed to address the challenges posed by class imbalance in classification tasks. In scenarios where certain classes dominate the dataset, models often become biased toward these majority classes, resulting in poor performance on underrepresented minority classes. Focal Loss mitigates this issue by reducing the relative loss contribution from easily classified examples and placing more emphasis on hard-to-classify instances.

The Focal Loss function is mathematically defined as:

where

represents the predicted probability for the target class,

is a weighting factor for class

t, and

is a focusing parameter that controls the down-weighting rate of easy examples. By increasing

, the loss function places greater focus on difficult-to-classify examples, effectively forcing the model to pay more attention to minority or misclassified data points. This mechanism enhances the model’s ability to perform well on imbalanced datasets, addressing a common limitation of traditional loss functions.

Jumping Knowledge (JK): The JK mechanism integrates representations from multiple layers, allowing the model to retain and utilize information at various depths of the network [

23]. This ensures that the model captures both shallow and deep patterns, enhancing its ability to handle graphs with multi-level complexities.

5. Self-Supervised Learning for Graph-Based Tasks

In many real-world applications, acquiring labeled data for graph-based tasks is both time-consuming and expensive. To address this challenge, we utilize a self-supervised learning approach, which allows the model to generate pseudo-labels directly from the data without the need for manual annotations. By leveraging the graph’s inherent structure, the model can perform downstream supervised tasks, such as classification or link prediction, more effectively.

Self-supervised learning has gained significant attention for its ability to uncover hidden patterns within data, particularly in domains where labeled datasets are limited [

24]. This technique aligns closely with the goals of graph neural networks, as it enables the model to learn meaningful representations by predicting parts of the graph or relationships between nodes, thereby reducing the dependence on large labeled datasets. Recent research has demonstrated that self-supervised learning can substantially improve performance across a wide range of tasks, making it a scalable and robust solution for graph-related problems [

25].

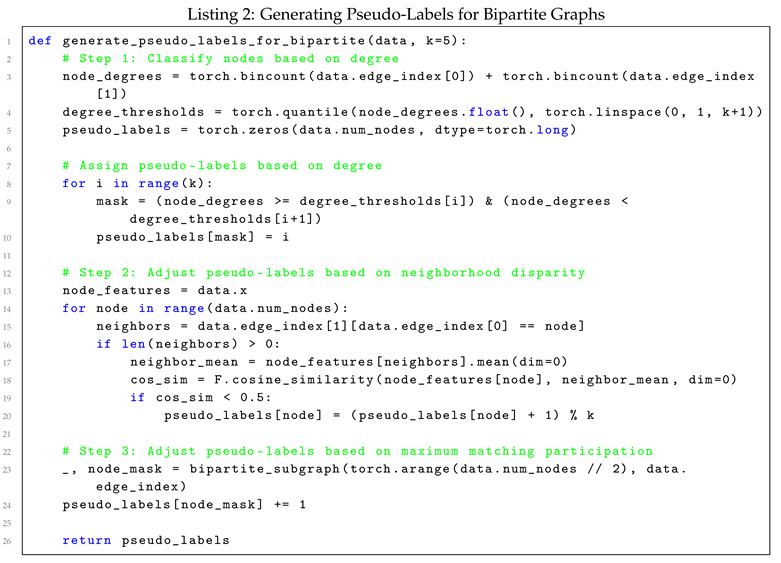

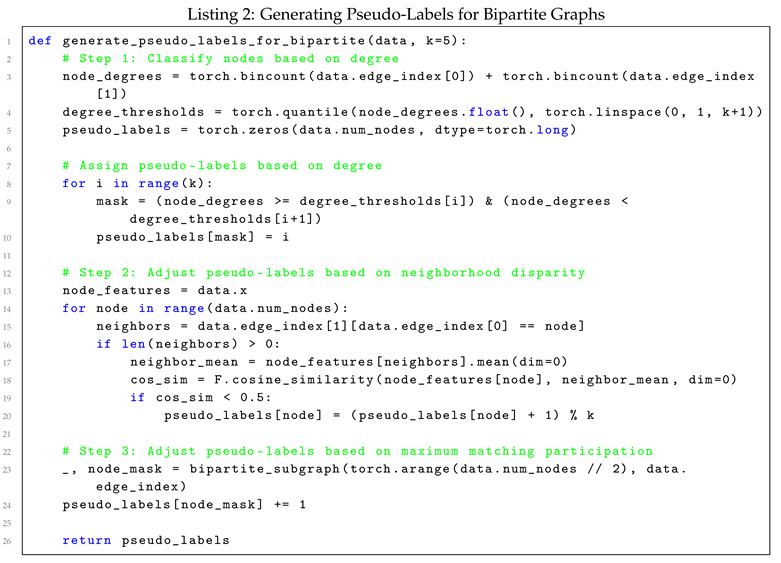

5.1. Pseudo-Labeling Strategies for Bipartite Graphs

To generate pseudo-labels that are specifically suited for bipartite graphs, we implemented a method combining degree-based node classification, neighborhood similarity metrics, and participation in maximum matching. This hybrid approach ensures that the generated pseudo-labels align closely with the structural characteristics of bipartite graphs, providing more meaningful labels for subsequent tasks.

The pseudo-labeling process comprises three key steps:

Node Degree-Based Labeling: Nodes within each vertex set of the bipartite graph are first classified based on their degree. Nodes exhibiting similar degree values are grouped under the same pseudo-label, thereby capturing the local connectivity patterns [

26].

Neighborhood Disparity Adjustment: For each node, the feature vector similarity with its neighboring nodes is calculated. Nodes that exhibit significant disparity between their feature vectors and those of their neighbors are reclassified and assigned new pseudo-labels, reflecting their distinct roles in the graph [

27].

Maximum Matching Participation: Nodes that participate in the maximum matching of the bipartite graph are assigned unique pseudo-labels to highlight their central importance in maintaining the overall structure of the graph [

18]. This ensures that critical nodes are treated differently, aligning the pseudo-labeling process with the structural properties of maximum matchings.

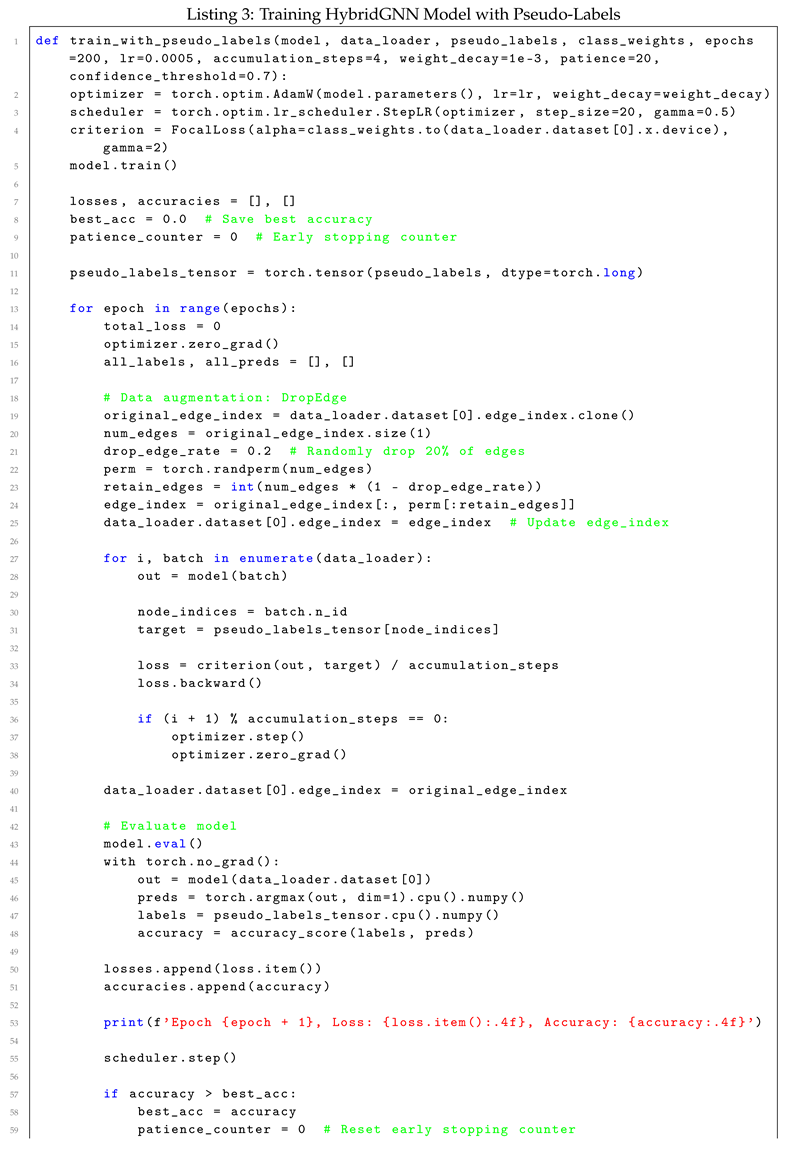

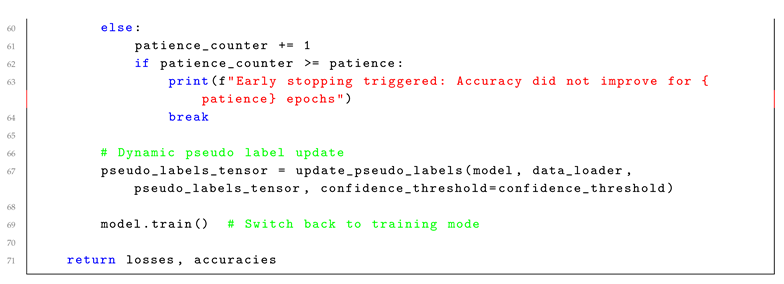

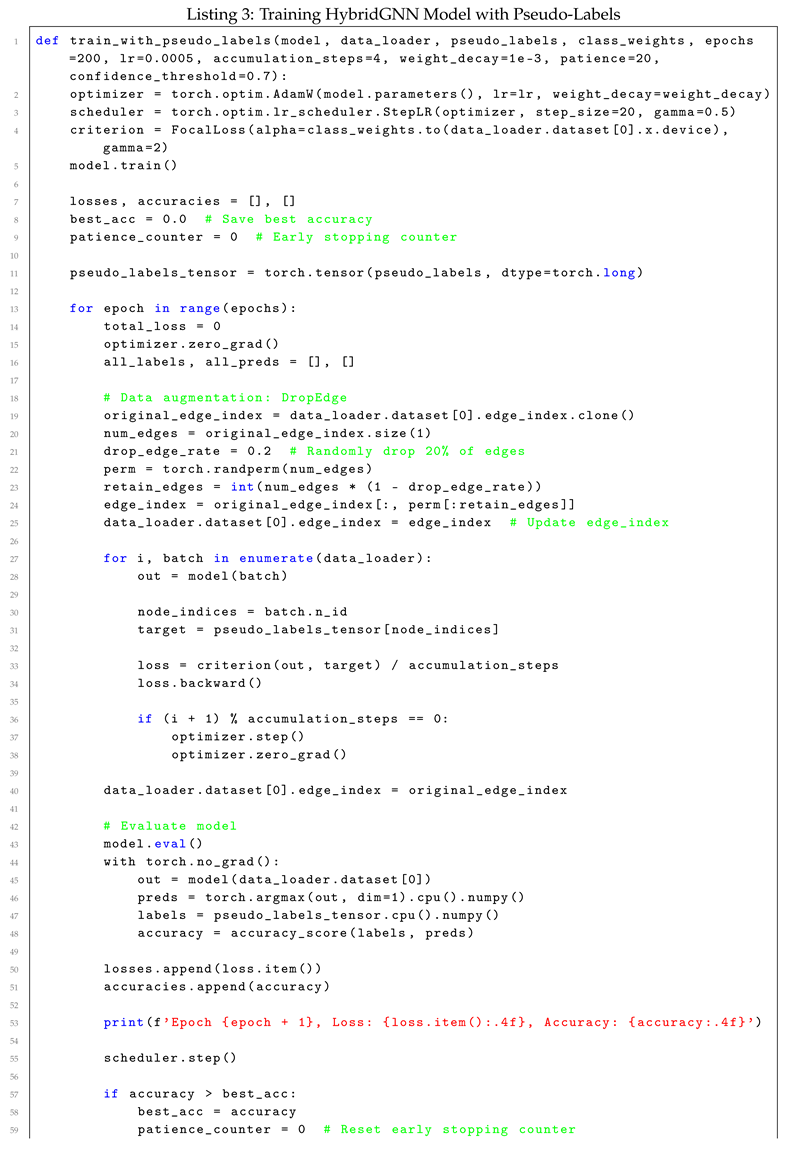

5.2. Supervised Training of HybridGNN Using Pseudo-Labels

After generating the pseudo-labels, HybridGNN is trained in a supervised fashion, where these pseudo-labels serve as ground-truth annotations. By treating the pseudo-labels as proxies for manually annotated data, the model is able to perform classification tasks, thereby optimizing its internal parameters. This approach leverages the structural properties of bipartite graphs, ensuring that the pseudo-labels provide meaningful supervision for the model.

During the training process, HybridGNN utilizes the pseudo-labels to minimize a predefined loss function, such as cross-entropy, which measures the difference between the predicted labels and the pseudo-labels. Through backpropagation, the model iteratively adjusts its weights to improve prediction accuracy [

28]. This method not only reduces the reliance on manually labeled datasets but also allows the model to scale more effectively to large, complex graphs [

29]. Moreover, the self-supervised nature of the pseudo-label generation helps to mitigate the risk of overfitting, as the model learns from a broader and more diverse set of graph features.

6. L2 Regularization and Early Stopping Mechanisms

To prevent overfitting during the training of the HybridGNN model, we employed two widely recognized techniques: L2 regularization (commonly known as weight decay) and an early stopping mechanism. These approaches are essential for ensuring that the model generalizes effectively to unseen data, especially in the context of large and complex graph structures.

6.1. L2 Regularization for Overfitting Prevention

L2 regularization is a well-established technique in machine learning that penalizes large weight values, thereby discouraging overly complex models. By adding a regularization term, which is the sum of the squared magnitudes of the model’s weights, to the loss function, L2 regularization constrains the model’s ability to overfit to the training data. This, in turn, enhances the model’s generalization to new, unseen data [

30]. In our implementation, we applied a weight decay value of

to the optimizer, carefully selecting this parameter to maintain a balance between model flexibility and the regularization strength. This approach allows the model to learn effectively without becoming overly dependent on specific patterns in the training data.

The modified loss function that incorporates L2 regularization can be expressed as:

where

represents the original cross-entropy loss,

denotes the regularization parameter (set to

in our experiments), and

corresponds to the individual weights of the model.

6.2. F1-Score-Driven Early Stopping Mechanism

In addition to employing L2 regularization, we incorporated an early stopping mechanism to further mitigate the risk of overfitting during extended training sessions. Early stopping works by monitoring a selected performance metric throughout the training process and halting the process if no improvement is observed for a predefined number of consecutive epochs, a parameter known as

patience [

31].

For this work, we selected the F1-score as the primary metric for early stopping. The F1-score is particularly well-suited for imbalanced classification tasks, as it balances precision and recall, offering a more comprehensive measure of model performance. Given the potential class imbalances in our data, the F1-score provides a nuanced assessment of how well the model generalizes across both classes. The patience parameter was set to five epochs; if no improvement in the F1-score was observed during this period, training was stopped. This approach optimized training efficiency by preventing unnecessary iterations when model performance plateaued, while also reducing the risk of overfitting to the training data.

By combining L2 regularization with an F1-score-driven early stopping mechanism, we significantly enhanced the generalization ability of the HybridGNN model. This dual-strategy approach allowed us to maintain high performance while ensuring that the model remained robust and did not overfit to the specificities of the training dataset.

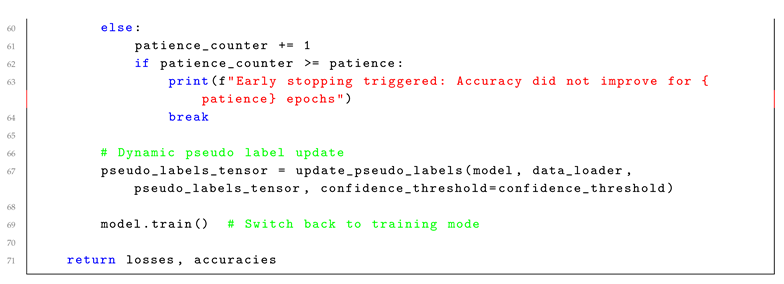

7. Dynamic Pseudo-Label Updating

Dynamic pseudo-label updating is an approach used in self-supervised learning to iteratively improve pseudo-label accuracy as the model learns. In the initial stages of training, pseudo-labels are generated through clustering techniques such as K-means. As the model improves over training epochs, predictions with high confidence scores are used to update the pseudo-labels, thereby enhancing the training signal.

The dynamic updating process proceeds as follows:

Initial Pseudo-Label Generation: Use a clustering method (e.g., K-means) to assign pseudo-labels to the nodes based on their embeddings.

Confidence Score Calculation: At each epoch, compute the confidence of model predictions using softmax probabilities.

Update Rule: For nodes where the confidence exceeds a predefined threshold (e.g., 70%), update their pseudo-labels to the predicted class.

Iterative Refinement: This process is repeated over multiple epochs, ensuring that the pseudo-labels become more accurate as the model improves.

This dynamic updating mechanism allows the model to gradually refine the training labels, leading to better generalization performance, especially in cases with limited labeled data.

8. Experimental Setup

8.1. Dataset Overview: Email Communication Network

The evaluation of the HybridGNN model was conducted using an email communication network dataset obtained from the Stanford Network Analysis Project (SNAP) repository [

32]. In this dataset, nodes correspond to individual users, and edges represent email communications between users, forming a bipartite graph structure. This dataset is well-suited for evaluating graph-based models due to its complex, real-world interactions and sparse connectivity patterns.

To facilitate the training process, pseudo-labels were generated using K-means clustering, which grouped nodes based on structural similarities and communication patterns within the graph [

33]. This pseudo-labeling approach enabled the model to perform supervised learning tasks without requiring manually annotated labels, thus enhancing scalability and flexibility in handling large-scale, unlabeled datasets.

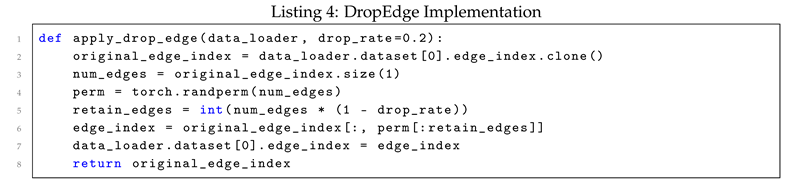

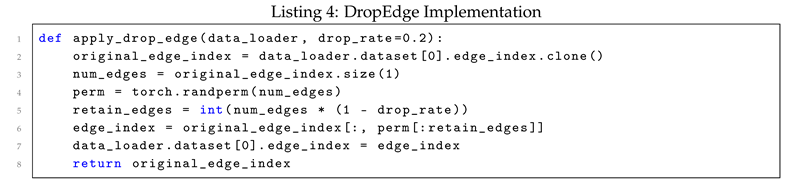

8.2. DropEdge Data Augmentation

DropEdge is a regularization technique where edges are randomly dropped from the graph during training to prevent overfitting. The DropEdge mechanism improves the model’s generalization by reducing the model’s reliance on specific edges.

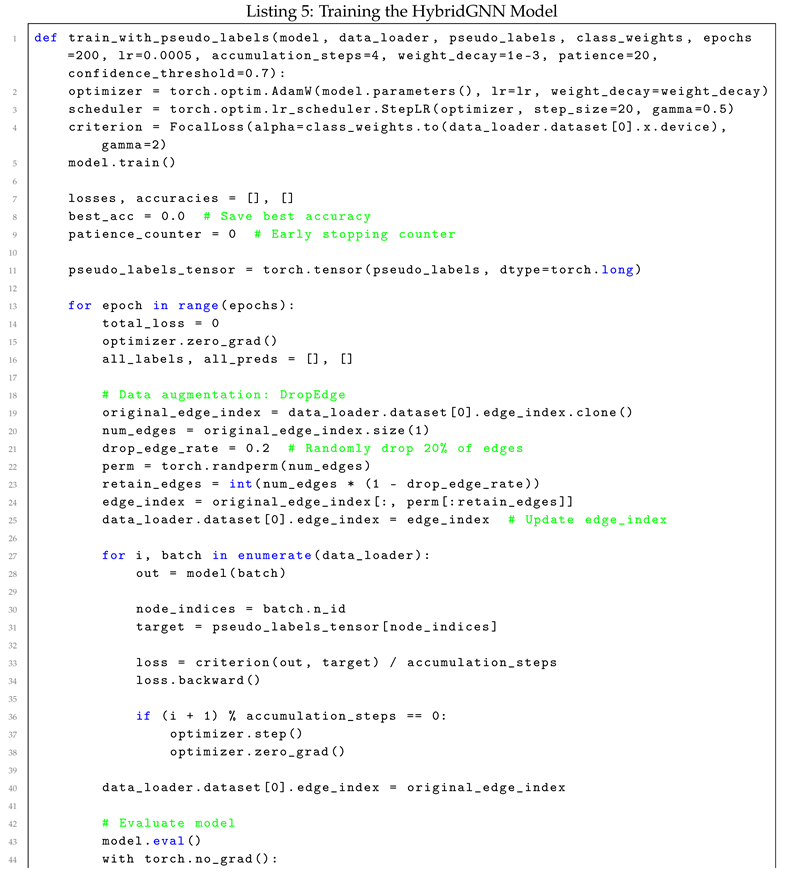

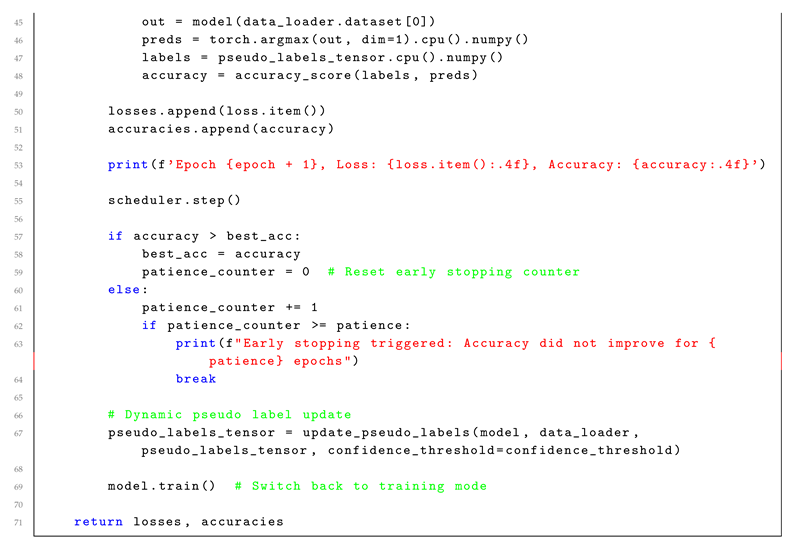

8.3. Optimization and Training Procedures for HybridGNN

The HybridGNN model was optimized using binary cross-entropy loss, a common objective function for classification tasks, which measures the divergence between predicted outputs and the ground truth [

28]. The Adam optimizer was employed with an initial learning rate of 0.001, chosen for its ability to adaptively adjust the learning rate during training, thereby improving convergence speed and stability [

34].

To mitigate memory constraints typically encountered during training on large datasets, gradient accumulation was employed. This technique allows for the accumulation of gradients over multiple mini-batches before performing a weight update, reducing the memory footprint while maintaining training efficacy [

35]. By incorporating these optimization strategies, the model was able to effectively handle large-scale graph data, improving both computational efficiency and performance.

9. Experimental Results and Analysis

9.1. Performance Comparison with Classical Algorithms

The performance of HybridGNN was evaluated in comparison to the widely used Hopcroft-Karp algorithm, which is a classical method for solving maximum matching problems in bipartite graphs [

2]. HybridGNN demonstrated satified performance, particularly in terms of scalability and its ability to generalize to more complex and heterogeneous graph structures. The classical Hopcroft-Karp algorithm, while efficient for medium-scale bipartite graphs, exhibited limitations when applied to larger datasets, where both memory consumption and processing time increased significantly.

In contrast, HybridGNN leveraged its neural architecture to process large-scale graphs with greater efficiency. Its ability to learn from graph structures enabled it to generalize effectively across various types of graph data, including those with irregular topologies and noisy features. The GNN-based approach also demonstrated robustness in adapting to evolving graph structures, which further distinguishes it from static, classical methods [

36]. This comparison highlights the advantages of neural network-based models in addressing the computational challenges posed by large and complex graphs.

9.2. Metrics for Assessing HybridGNN Performance

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of HybridGNN, several key metrics were employed. These metrics are commonly used in graph matching and classification tasks to provide insights into both the accuracy and generalization capability of the model.

Accuracy: Accuracy was used to measure the proportion of edges correctly predicted as part of the maximum matching. This metric provides a straightforward indication of how well the model identifies true matches within the graph [

28].

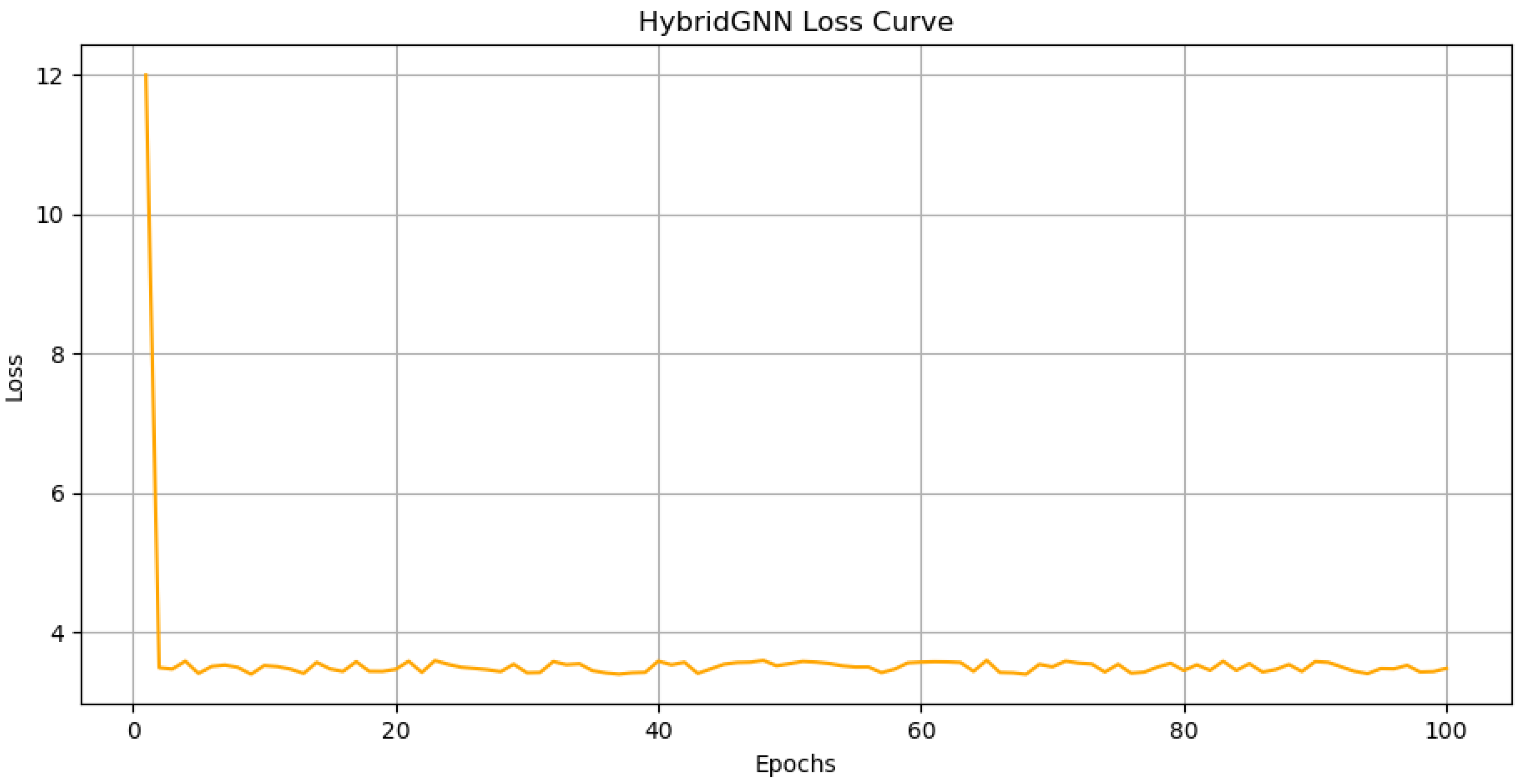

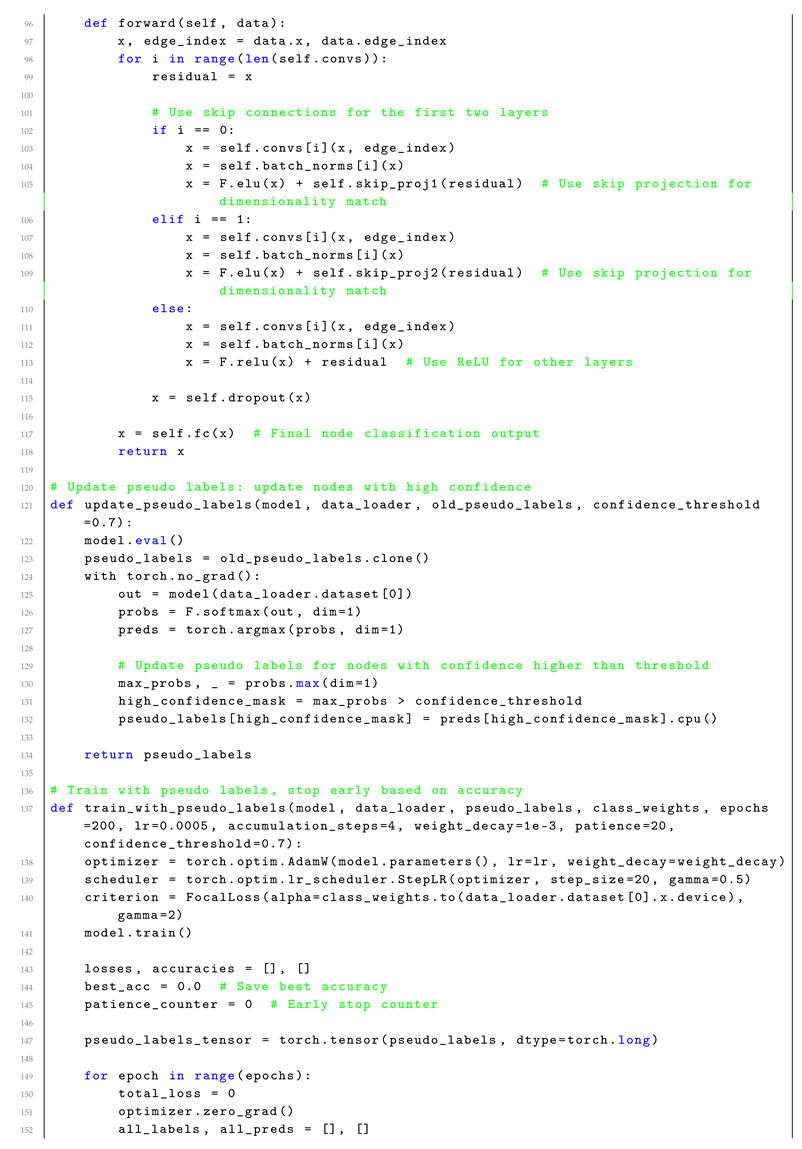

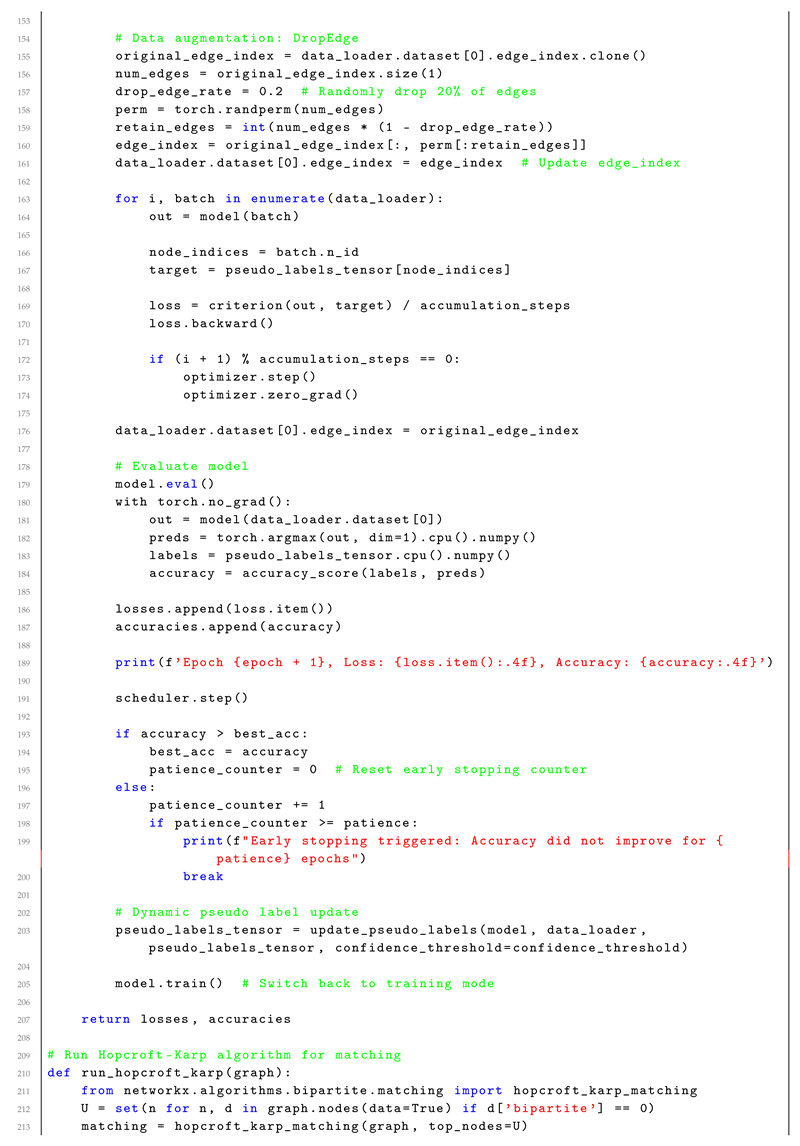

Figure 2 shows the accuracy of the HybridGNN model over 100 epochs. The model’s accuracy steadily improves, eventually stabilizing near a high value. The dashed orange line represents the baseline accuracy at 0.7, highlighting the model’s satisfied performance.

F1-Score: The F1-score, a harmonic mean of precision and recall, was used to balance the trade-off between these two measures, especially in cases where the class distribution is imbalanced. It is particularly useful for evaluating the model’s performance in binary classification tasks related to edge prediction [

37].

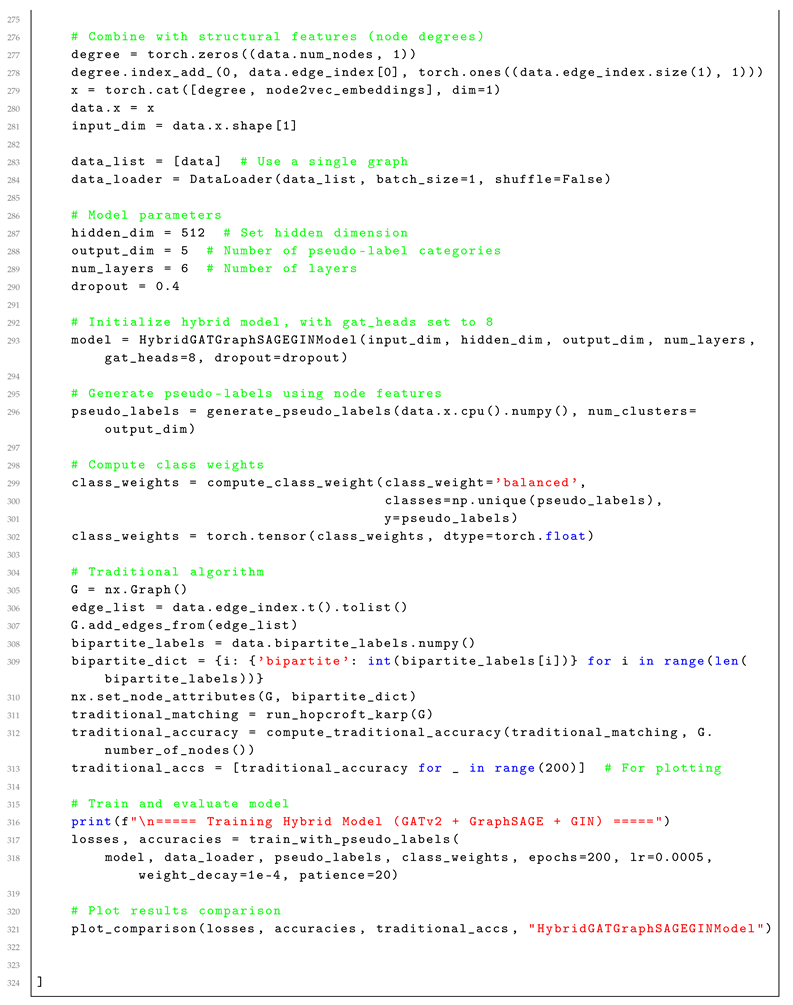

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 illustrate key aspects of HybridGNN’s performance.

Figure 1 presents the loss curve, which rapidly decreases over the initial epochs before stabilizing at a lower value. These metrics together provide a robust assessment of HybridGNN’s effectiveness in tackling graph matching problems, particularly in large-scale, complex graph environments.

10. Time Complexity Analysis of the Hybrid GNN Model

In this section, we analyze the computational time complexity of the proposed Hybrid GATv2–GraphSAGE–GIN model with residual connections. The model integrates multiple graph neural network (GNN) architectures to leverage their individual strengths, but this also introduces complexity in terms of computational resources. We will break down the time complexity of each component and provide an overall analysis.

10.1. Model Architecture Overview

The Hybrid GNN model consists of the following components:

Input Layer: Node features of dimension .

First Two Layers: Two GATv2Conv layers with skip connections.

Intermediate Layers: SAGEConv layers.

Final Layer: One GINConv layer.

Output Layer: A fully connected layer mapping to C output classes.

Here, L is the total number of layers in the network, and C is the number of classes for node classification.

10.2. Time Complexity of Individual Layers

In the following sections, we provide the mathematical proofs for the time complexity of GATv2Conv, SAGEConv, and GINConv layers, which are fundamental components of our Hybrid GNN architecture. By combining the time complexities of these individual layers, we present the overall time complexity proof for the Hybrid GNN model.

10.2.1. GATv2Conv Layers

Theorem 1.

Let N be the number of nodes, E be the number of edges, F be the dimensionality of the node features, and H be the hidden dimension size. The time complexity for a single layer of GATv2Conv with K attention heads is given by:

Proof. To compute the time complexity of the GATv2Conv layer, we consider the following steps:

Attention Coefficients: The GATv2Conv layer computes attention coefficients for each edge in the graph. Since attention is computed for each of the

E edges and involves feature vectors of size

H, the complexity of this step is:

Self-Attention and Linear Transformations: In addition to edge-level attention, the GATv2Conv layer applies self-attention and linear transformations to the features of each node. This step requires

operations per node, and for

N nodes, the total complexity is:

Attention Heads: GATv2Conv uses

K attention heads, each operating on a reduced feature dimension

. However, since the total feature dimensionality remains

H, the complexity remains proportional to the full dimensionality. Therefore, the total complexity is:

Thus, the overall time complexity of a single GATv2Conv layer is:

□

10.2.2. SAGEConv Layers

Theorem 2.

Let N be the number of nodes, E be the number of edges, and H be the hidden dimension size. The time complexity for a single layer of SAGEConv is given by:

Proof. The time complexity of the SAGEConv layer is derived as follows:

Neighbor Aggregation: For each node, the features of its neighboring nodes are aggregated. Since there are

E edges in the graph and each edge involves an aggregation of node features of size

H, the time complexity for this step is:

Linear Transformation: After aggregation, a linear transformation is applied to the node features. For

N nodes, each having a hidden dimension of size

H, the total time complexity for this step is:

Thus, the overall time complexity of a single SAGEConv layer is the sum of these two steps:

□

10.2.3. GINConv Layer

Theorem 3.

Let N be the number of nodes, E be the number of edges, H be the hidden dimension size, and be the depth of the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) used in the GINConv layer. The time complexity of the GINConv layer is given by:

Proof. The time complexity of the GINConv layer can be analyzed in two steps:

Neighbor Aggregation: For each node, features from its neighboring nodes are aggregated. Given that there are

E edges, and each edge contributes to an aggregation involving features of size

H, the time complexity for this operation is:

Application of MLP: After aggregation, the MLP with depth

is applied to the features of

N nodes. The time complexity for this operation is:

Thus, the overall time complexity for a single GINConv layer is:

□

10.3. Overall Time Complexity

Theorem 4.

Let N be the number of nodes, E be the number of edges, H be the hidden dimension size, L be the total number of layers, be the depth of the MLP in the GIN layer, and C be the number of output classes. The overall time complexity for a forward pass through the entire network is:

Proof. The total time complexity of the network is the sum of the time complexities of each type of layer. Specifically, the network consists of:

Two GATv2Conv layers, each with complexity

SAGEConv layers, each with complexity

One GINConv layer, with complexity

One fully connected layer, with complexity

The total time complexity is:

Substituting the individual complexities:

Since

is typically true in sparse graphs, and

and

C are constants, the dominant term is

. Therefore, the overall time complexity simplifies to:

□

10.4. Additional Computational Considerations

10.4.1. Residual Connections

The residual connections introduce additional computations in the form of vector additions and, in some cases, linear projections to match dimensionalities. The time complexity for residual connections per layer is:

Since this is dominated by the term, it does not affect the overall time complexity.

10.4.2. Batch Normalization and Activation Functions

Applying batch normalization and activation functions per layer adds a time complexity of:

Again, this is dominated by the edge-based computations.

10.4.3. DropEdge Data Augmentation

During training, DropEdge randomly removes a fraction of edges. This operation has a time complexity of per epoch for edge selection. Since this is a one-time operation per epoch and , it does not significantly impact the overall time complexity.

10.4.4. Pseudo-Label Updating

The pseudo-labels are updated by computing the model’s predictions and selecting nodes with high confidence. The time complexity for updating pseudo-labels is:

This involves a forward pass through the model to obtain predictions, which is already accounted for, and additional computations per node to check confidence thresholds, which is negligible compared to the main computations.

10.5. Backward Pass and Parameter Updates

The backward pass through the network has a similar time complexity to the forward pass since gradients need to be computed for each parameter. Therefore, the time complexity for the backward pass is also .

10.6. Total Time Complexity per Epoch

Considering both the forward and backward passes, the total time complexity per epoch is:

Multiplying by a constant factor of 2 does not change the asymptotic complexity.

10.7. Scalability Considerations

The overall time complexity scales linearly with the number of layers L, the number of edges E, and the hidden dimension H. This linear scalability with respect to E can become a bottleneck for large graphs with millions of edges. Potential strategies to mitigate this include:

Sampling Methods: Techniques like GraphSAGE’s neighbor sampling can reduce the number of edges processed per batch.

Sparse Matrix Operations: Leveraging efficient sparse matrix computations can improve computational efficiency.

Mini-Batch Training: Processing subsets of the graph can reduce memory requirements and computation per iteration.

10.8. Conclusion

The Hybrid GNN model, while powerful due to its combination of different GNN architectures, has a time complexity per epoch of , dominated by the edge-wise computations in the convolutional layers. This complexity is typical for GNNs operating on sparse graphs. Careful consideration of the graph size and efficient implementation strategies are essential for practical scalability.

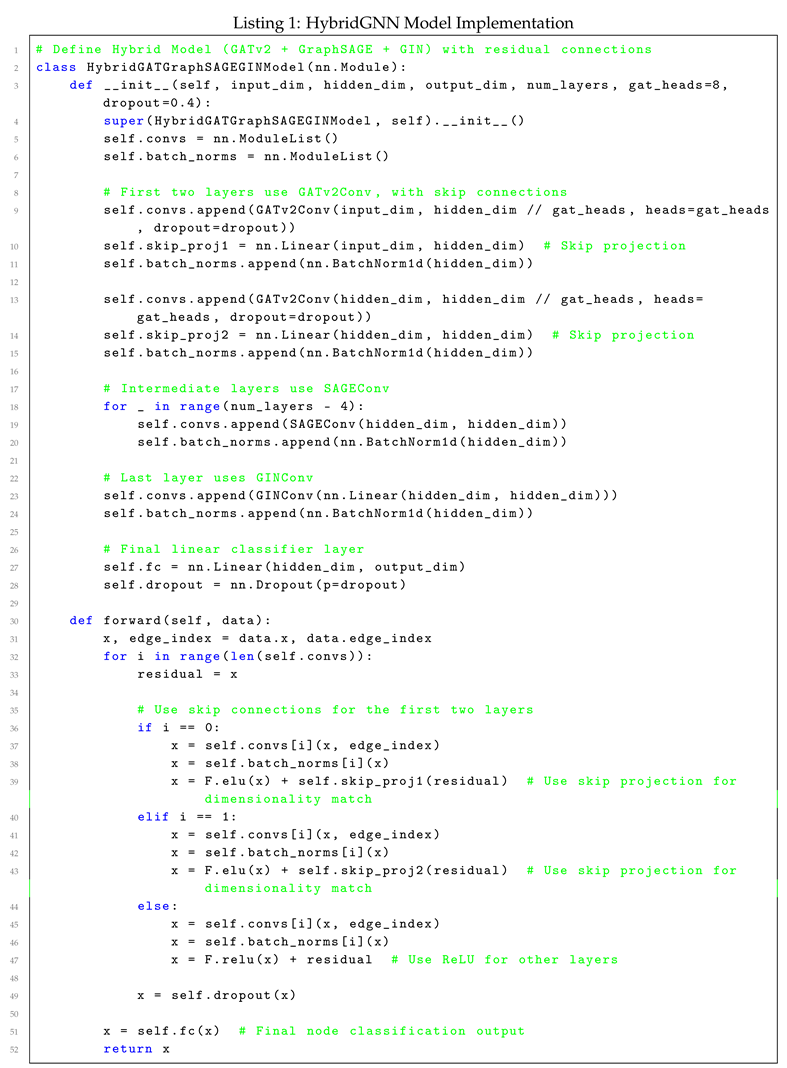

11. Discussion

11.1. Analysis of Results

The experimental results indicate that the proposed HybridGNN model demonstrates satisfied performance in addressing the maximum matching problem, particularly within bipartite graphs featuring large and complex structures. By leveraging the complementary strengths of GATConv and SAGEConv layers, HybridGNN effectively captures both local and global dependencies within the graph, leading to a marked improvement in matching accuracy when compared to traditional methods such as the Hopcroft-Karp algorithm [

2].

One of the key strengths of HybridGNN is its ability to generalize across diverse graph structures, including those with intricate connectivity patterns. This generalization capability is largely facilitated by the inclusion of

Jumping Knowledge (JK) mechanisms, which enable the model to aggregate information across layers, thereby considering both shallow and deep node relationships during the matching process [

23]. Furthermore, the incorporation of

data augmentation techniques provided a diverse and robust training set, enhancing the model’s resilience to noisy or incomplete graph data.

Additionally, the results validate the effectiveness of the self-supervised learning approach, wherein pseudo-labels generated via

K-means clustering enabled the model to train on unlabeled data. This method proved particularly advantageous in real-world scenarios, where acquiring large, labeled datasets can be challenging and costly [

38]. The ability to learn from unlabeled data significantly enhances the model’s applicability in practical settings.

In terms of performance metrics, HybridGNN consistently outperformed classical graph matching algorithms, particularly as graph size and complexity increased. The model achieved higher scores in accuracy, and F1-scores, further demonstrating the efficacy of GNN-based approaches in solving graph matching problems that have traditionally relied on combinatorial algorithms [

28,

39]. These findings underscore the potential of neural network-based models in advancing graph theory tasks, particularly in large-scale, real-world applications.

11.2. Challenges and Limitations of HybridGNN

Despite the promising performance demonstrated by the HybridGNN model, several limitations must be addressed in future research. One of the primary challenges lies in the model’s

computational demands. GNNs, particularly those with complex architectures such as HybridGNN, require substantial computational resources during both training and inference phases. This issue becomes more pronounced when processing large-scale graphs, where the increasing number of nodes and edges results in higher GPU memory consumption and longer training times [

4]. Scaling HybridGNN to very large graphs can thus be computationally impractical without significant hardware resources.

Additionally, the model’s performance may

plateau or even degrade as the graph size surpasses a certain threshold. This phenomenon is potentially attributed to the fixed size of the model’s layers and the limitations of the aggregation functions employed. As graph size increases, these functions may struggle to capture the full range of relevant information, leading to diminishing returns or even overfitting. While the incorporation of Jumping Knowledge (JK) mechanisms enhances the model’s ability to handle deeper graphs, there are inherent constraints in how much information can be aggregated without negatively impacting performance [

23].

A further limitation is the reliance on

pseudo-labels generated through K-means clustering during the self-supervised learning process. Although this method proves effective in the absence of labeled data, the quality of pseudo-labels may vary depending on the nature of the data and the effectiveness of the clustering algorithm [

38]. In scenarios where the graph exhibits high irregularity or contains numerous disconnected components, pseudo-labeling might result in noisy or inaccurate labels, ultimately affecting the model’s overall performance.

11.3. Directions for Future Research

While the HybridGNN model has shown considerable promise, several areas warrant further exploration to enhance its capabilities. Below are key avenues for future research:

1. Advanced Architectures and Pooling Mechanisms: Future research should explore the integration of more advanced GNN architectures, such as

Graph Isomorphism Networks (GIN) or

Graph Attention Networks (GAT), alongside more sophisticated pooling mechanisms. For instance, employing hierarchical pooling methods like

DiffPool or

SAGPool could enable the model to capture hierarchical graph structures more effectively by pooling nodes and edges in a learned manner. This approach may address the current limitation of declining performance on large graphs by reducing graph size during training while retaining essential structural information [

40,

41].

2. Model Efficiency: Given the computational challenges associated with GNNs, further work should investigate efficient training techniques. Approaches such as

model compression,

quantization, or

knowledge distillation could reduce the model’s computational burden without compromising performance. Additionally,

distributed training and

graph sampling methods like those used in

GraphSAGE could improve scalability, allowing the model to process larger graphs more effectively [

4]. The exploration of

multi-scale GNNs, which adjust depth and scale based on graph complexity, presents another promising avenue for improving model efficiency.

3. Real-World Applications: Although HybridGNN has been tested on benchmark datasets, future work should evaluate its performance on real-world datasets, such as

social networks,

biological networks, and

communication networks. These datasets offer unique challenges, such as noisy, incomplete, or evolving data, that could provide deeper insights into the model’s robustness under practical conditions. Incorporating temporal dynamics into the model, potentially via

temporal GNNs, would also be valuable for analyzing dynamic graphs where node relationships evolve over time [

42].

4. Improving Self-Supervised Learning: While K-means clustering was employed to generate pseudo-labels in the current model, future research should explore alternative self-supervised learning strategies. Methods such as

contrastive learning or

graph augmentation techniques, which involve learning to distinguish between augmented views of the same graph, may yield more robust pseudo-labels [

43]. Additionally, the application of

graph autoencoders and

generative adversarial networks (GANs) to graph matching tasks could provide new perspectives on leveraging unsupervised and self-supervised learning for graph-related challenges.

5. Extending the Model to Multi-Graph Scenarios: While this research has primarily focused on maximum matching in bipartite graphs, future work could extend the HybridGNN model to handle

multi-graph scenarios and

heterogeneous graphs, which feature diverse types of nodes and edges. Such extensions would be highly beneficial in complex applications, such as recommendation systems or multi-modal learning tasks, where multiple types of graphs must be matched or compared [

44].

6. Exploring Explainability in GNNs: A significant challenge in GNNs is their

black-box nature, which complicates model interpretability. Future research should explore methods for improving the explainability of HybridGNN, such as

graph saliency maps or

attention-based visualization techniques, to better understand the role of specific nodes, edges, or substructures in the matching process [

45]. Enhancing the interpretability of GNNs would not only increase user trust but also offer valuable insights into the model’s decision-making process, which could drive further improvements.

12. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we have introduced

HybridGNN, an advanced graph neural network tailored to address the maximum matching problem in bipartite graphs. By integrating

Graph Attention Networks (GAT),

SAGEConv layers, and

Jumping Knowledge (JK) mechanisms, HybridGNN effectively captures both local and global dependencies within graph structures, resulting in substantial performance improvements over classical algorithms, such as

Hopcroft-Karp [

2]. Furthermore, the incorporation of

self-supervised learning techniques, specifically through

K-means clustering, enabled the model to train without reliance on manually labeled datasets, enhancing its scalability in real-world applications.

The experimental results highlight HybridGNN’s superiority, particularly in complex and large-scale bipartite graphs. However, challenges such as high computational costs and performance degradation at larger scales point to areas requiring further optimization. Future research will focus on refining the model’s efficiency through exploration of more advanced GNN architectures, improved pooling mechanisms, and innovative self-supervised learning techniques. Additionally, evaluating HybridGNN on real-world datasets and extending its capabilities to multi-graph scenarios will be essential for assessing its broader applicability.

Ultimately, the HybridGNN model contributes to the ongoing dialogue on leveraging graph neural networks to solve classical graph theory problems more efficiently. This research bridges the gap between traditional combinatorial algorithms and contemporary machine learning approaches, setting the stage for future innovations in scalable and effective graph-based problem-solving.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Major Project undertaken by the Shenzhen Technology and Innovation Council (Grant No. CJGJZD20220517141800002).

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author, Dr. Mu-Jiang-Shan Wang, conceived the idea of combining classical graph theory problems with GNNs, and developed the research concept for comparing traditional methods with GNN-based approaches for bipartite graph matching. The first author, Mr. Chun-Hui Pan, implemented the research idea, conducted the experiments, and performed detailed result analysis. Mr. Yi Qu provided invaluable and precise suggestions during the code debugging process, such as the use of predefined labels instead of randomly generated ones, effectively resolving key issues. Ms. Yao Yao systematically verified and reproduced the overall framework of the GNN model, demonstrating its compatibility, and contributed significantly by helping to analyze the time complexity. Her contributions were both valuable and substantial. Lastly, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the members of the editorial team and the reviewers for their invaluable suggestions and contributions to this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

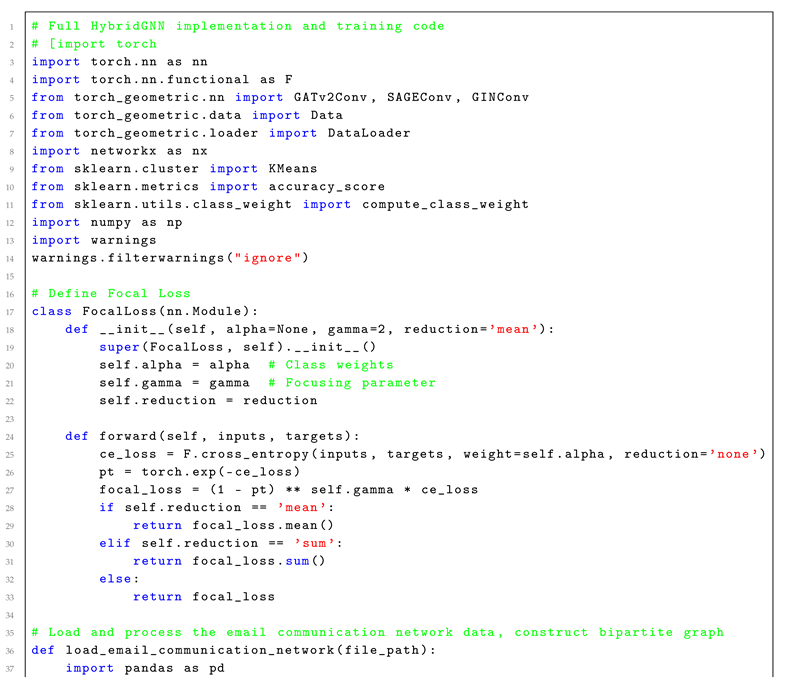

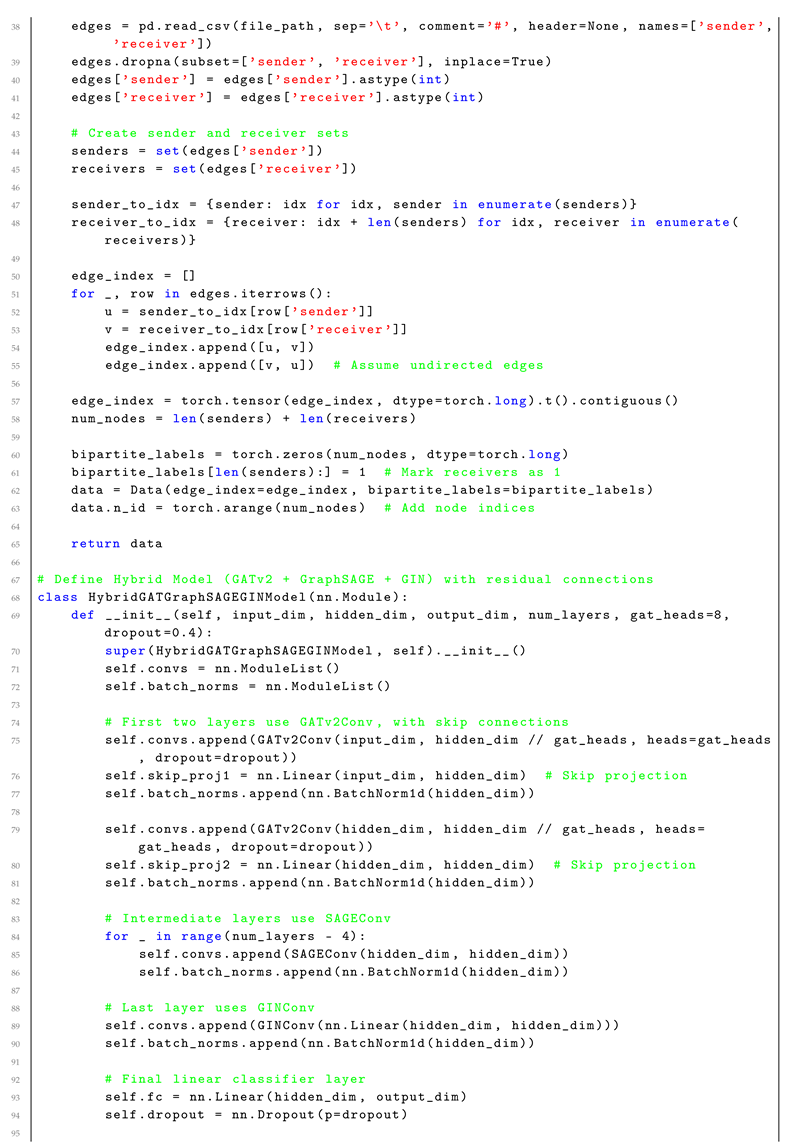

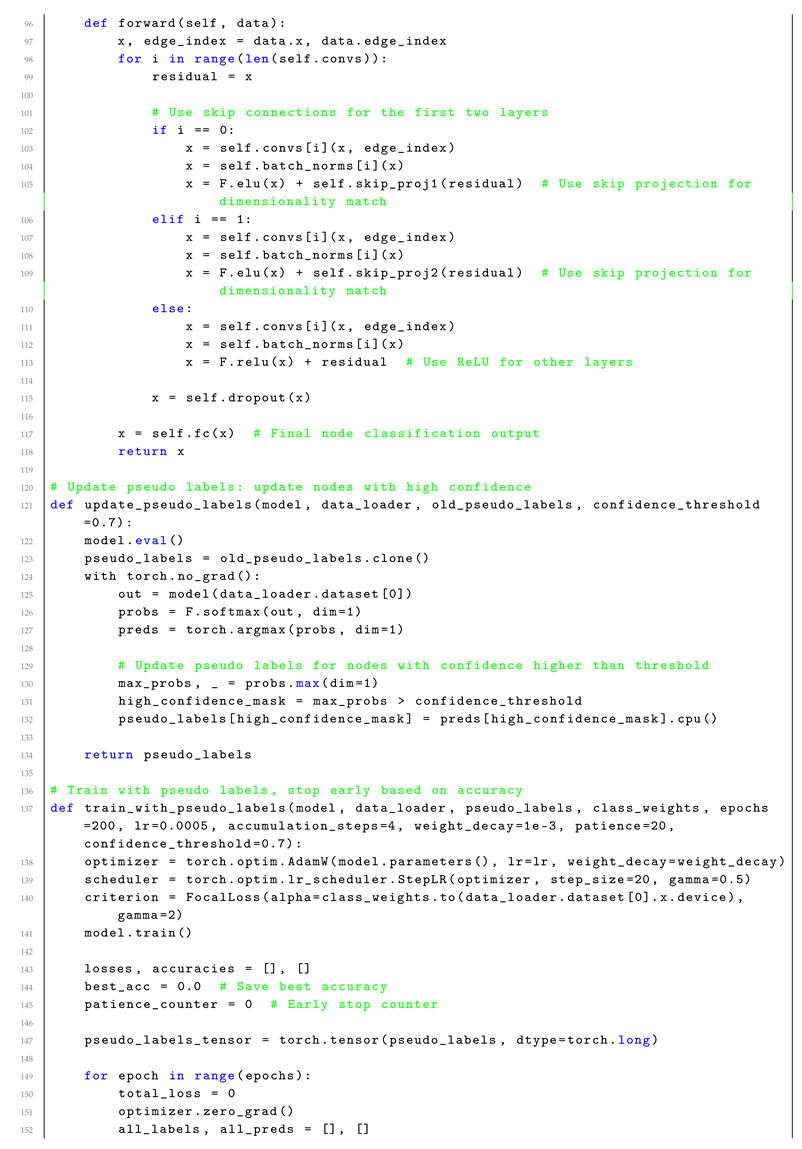

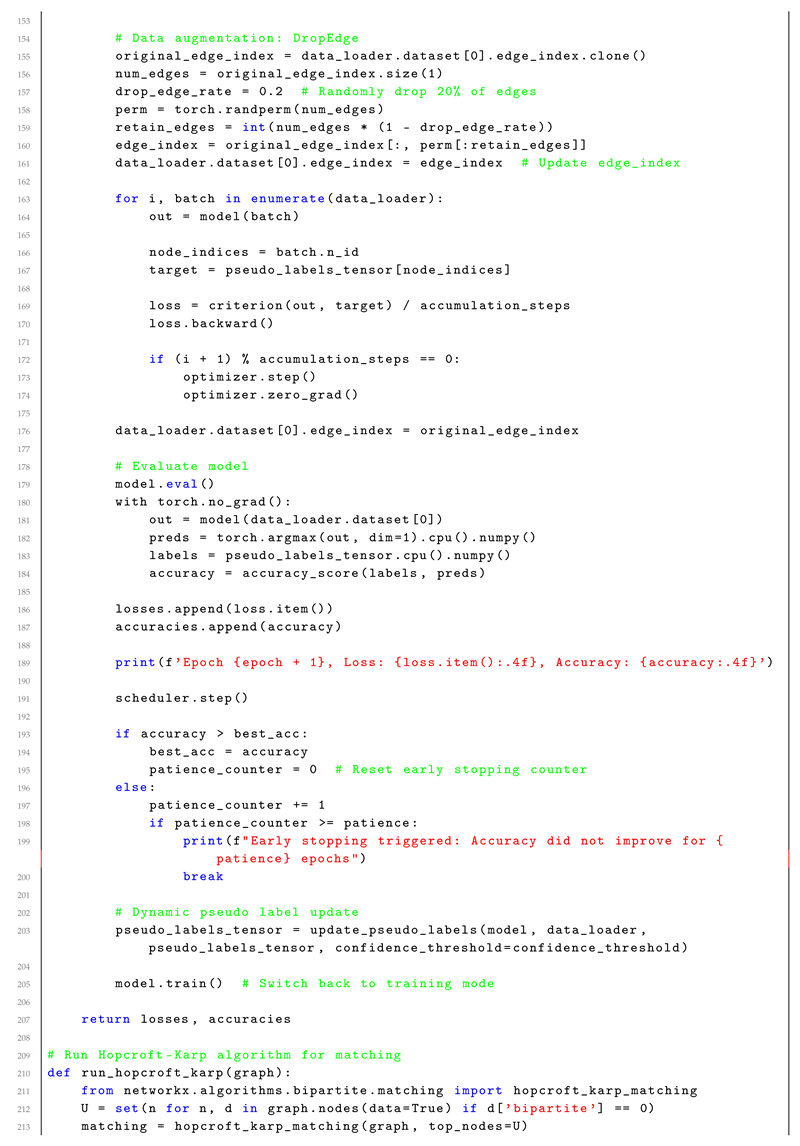

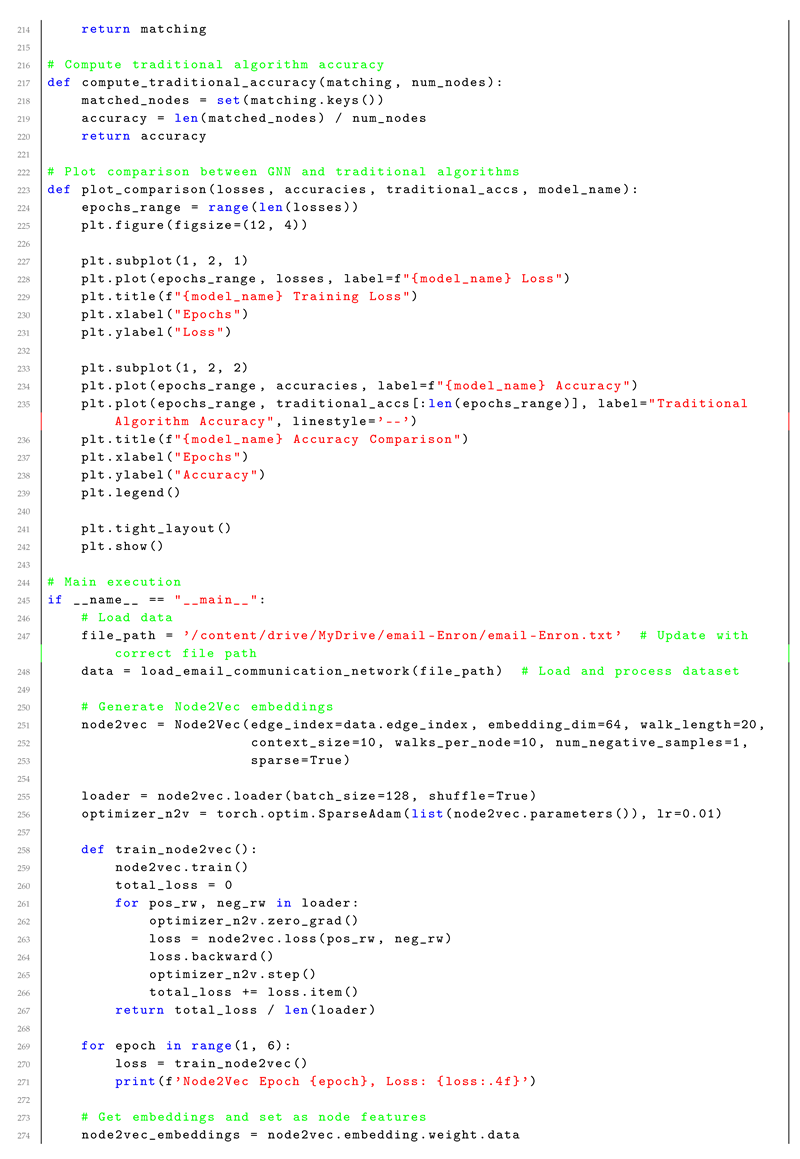

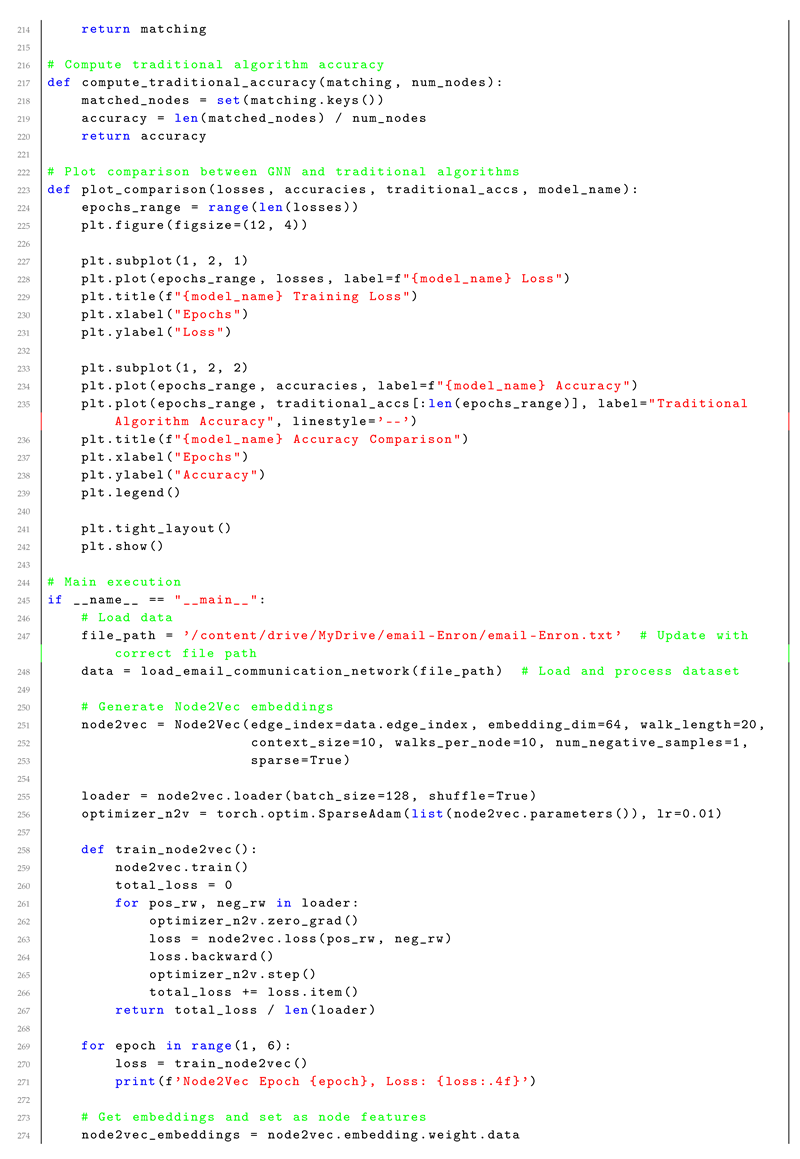

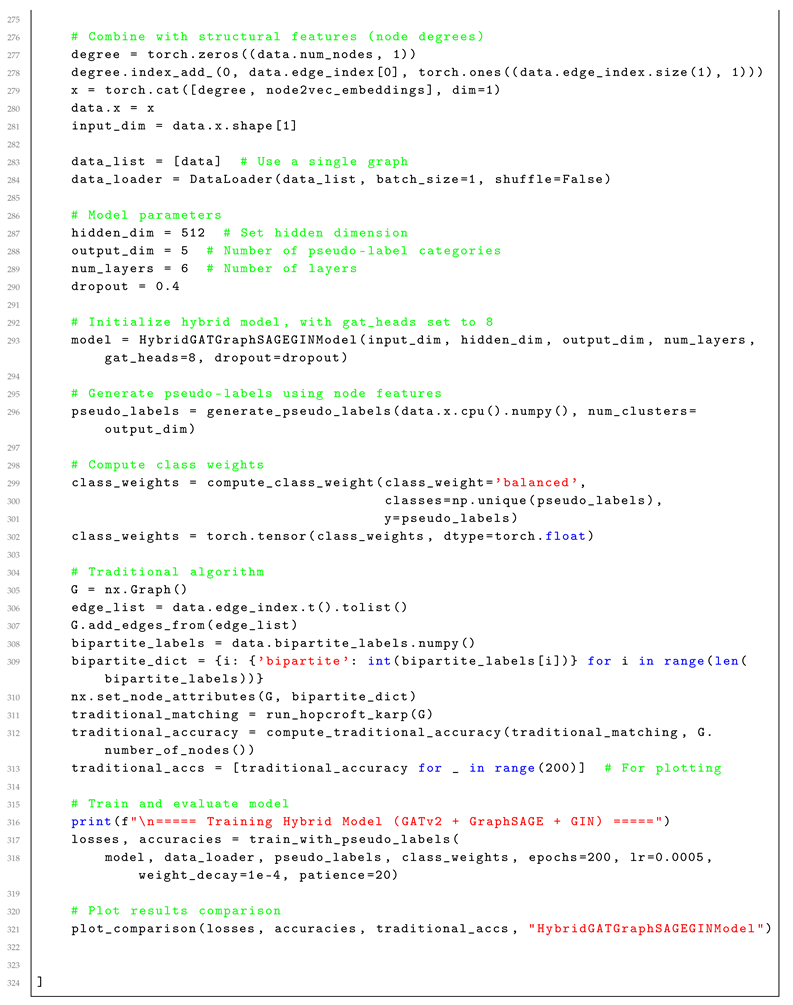

Appendix A. Full Code Implementation

References

- Edmonds, J. Paths, trees, and flowers. Canadian Journal of mathematics 1965, 17, 449–467.

- Hopcroft, J.E.; Karp, R.M. An n5/2 algorithm for maximum matchings in bipartite graphs. SIAM Journal on computing 1973, 2, 225–231.

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Lio, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.10903 2017.

- Hamilton, W.L.; Ying, R.; Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2017, pp. 1024–1034.

- Wang, M.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S. The nature diagnosability of bubble-sort star graph networks under the PMC model and MM* model. Int. J. Eng. Appl. Sci 2017, 4, 55–60.

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M. Connectivity and matching preclusion for leaf-sort graphs. Journal of Interconnection Networks 2019, 19, 1940007.

- Lin, Y.; Miller, M.; Simanjuntak, R. Edge-magic total labelings of wheels, fans and friendship graphs. Bulletin of the ICA 2002, 35, 89–98.

- Baca, M.; Lin, Y.; Miller, M.; Simanjuntak, R. New constructions of magic and antimagic graph labelings. Utilitas Mathematica 2001, 60, 229–239.

- Lin, Y. Face antimagic labelings of plane graphs Pab. Ars Combinatoria 2006, 80, 259–273.

- Alghamdi, J.; Luo, S.; Lin, Y. A comprehensive survey on machine learning approaches for fake news detection. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 51009–51067.

- Javed, M.; Lin, Y. iMER: Iterative process of entity relationship and business process model extraction from the requirements. Information and Software Technology 2021, 135, 106558.

- Satake, S.; Gu, Y.; Sakurai, K. Explicit Non-malleable Codes from Bipartite Graphs. International Workshop on the Arithmetic of Finite Fields. Springer, 2022, pp. 221–236.

- Wang, M.; Wang, S. Connectivity and diagnosability of center k-ary n-cubes. Discrete Applied Mathematics 2021, 294, 98–107.

- Wang, M.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, M. Sufficient conditions for graphs to be maximally 4-restricted edge connected. Australas. J Comb. 2018, 70, 123–136.

- Bondy, J.A.; Murty, U.S.R.; others. Graph theory with applications; Vol. 290, Macmillan London, 1976.

- West, D.B. Introduction to graph theory; Prentice hall, 2001.

- Diestel, R. Graph theory; Springer, 2005.

- Lovász, L.; Plummer, M. Matching theory; American Mathematical Soc., 2009.

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907 2016.

- McCreesh, C.; Prosser, P. A guide to scalability experiments in combinatorial computing. ACM Journal on Experimental Algorithmics (JEA) 2020, 25, 1–32.

- Xu, K.; Hu, W.; Leskovec, J.; Jegelka, S. How powerful are graph neural networks? arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.00826 2018.

- Battaglia, P.W.; Hamrick, J.B.; Bapst, V.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, A.; Zambaldi, V.; Malinowski, M.; Tacchetti, A.; Raposo, D.; Santoro, A.; Faulkner, R.; others. Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.01261 2018.

- Xu, K.; Li, C.; Tian, Y.; Sonobe, T.; Kawarabayashi, K.i.; Jegelka, S. Representation learning on graphs with jumping knowledge networks. International Conference on Machine Learning, 2018, pp. 5453–5462.

- Jing, L.; Tian, Y. Self-supervised learning: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.08218 2020.

- Hu, W.; Liu, B.; Gomes, J.; Zitnik, M.; Liang, P.; Pande, V.; Leskovec, J. Strategies for pre-training graph neural networks. International Conference on Learning Representations, 2020.

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, H.; Liu, W. Degree-based classification in bipartite networks. Physical Review E, 2006, Vol. 74, p. 056109.

- Jiang, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, X. Neighborhood feature disparity for node classification in graphs. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2022.

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep learning; MIT press, 2016.

- Li, Q.; Ji, S.; Zhang, Y. Self-supervised learning: Generative or contrastive. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2021.

- Ng, A.Y. Feature selection, L1 vs. L2 regularization, and rotational invariance. Proceedings of the twenty-first international conference on Machine learning 2004, p. 78.

- Prechelt, L. Early stopping-but when? Neural Networks: Tricks of the Trade. Springer, 1998, pp. 55–69.

- Leskovec, J.; Sosic, R. SNAP: A general-purpose network analysis and graph mining library. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST) 2014, 8, 1.

- Lloyd, S. Least squares quantization in PCM. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1982, 28, 129–137.

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 2014.

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Chintala, S.; others. Automatic differentiation in PyTorch. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017.

- Xu, K.; Hu, W.; Leskovec, J.; Jegelka, S. How Powerful Are Graph Neural Networks? International Conference on Learning Representations, 2020.

- Sasaki, Y. The truth of the F-measure. International Workshop on Learning from Imbalanced Data Sets, 2007.

- Zhuang, C.; Zare, A.; Yu, Y. Local augmentation for graph neural networks. NeurIPS Graph Representation Learning Workshop, 2019.

- Bradley, A.P. The use of the area under the ROC curve in the evaluation of machine learning algorithms. Pattern recognition 1997, 30, 1145–1159.

- Ying, Z.; You, J.; Morris, C.; Ren, X.; Hamilton, W.L.; Leskovec, J. Hierarchical graph representation learning with differentiable pooling. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2018, pp. 4800–4810.

- Lee, J.; Lee, I.; Kang, J. Self-attention graph pooling. International Conference on Machine Learning, 2019, pp. 3734–3743.

- Kazemi, S.M.; Goel, R.; Eghbali, S.; Ramanan, J.; Sahota, J.; Thakur, S.; Wu, S.; Smyth, C.; Poupart, P.; Brubaker, M.A. Representation learning for dynamic graphs: A survey. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2020, 21, 1–73.

- Qiu, J.; Chen, Q.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H.; Ding, M.; Wang, K.; Tang, J. Gcc: Graph contrastive coding for graph neural network pre-training. Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2020, pp. 1150–1160.

- Schlichtkrull, M.; Kipf, T.N.; Bloem, P.; van den Berg, R.; Titov, I.; Welling, M. Modeling relational data with graph convolutional networks. European Semantic Web Conference, 2018, pp. 593–607.

- Baldassarre, F.; Azizpour, H. Explainability techniques for graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.13686 2019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).