1. Introduction

Enhancing agricultural output by safeguarding the environment as major priority for the scientific community (Murata et al., 2021). In recent decades, agriculture production has accelerated meet to increasing food demand, but it has also significantly harmed the global environment (Alvarez et al., 2021). The overuse of chemical fertilisers is a dominant strategy for enhancing crop yields and augmenting the profitability of the agricultural sector (Osorio-Reyes et al., 2023). This method results in considerable environmental problems, including emissions of gas from greenhouse, deprivation of water and soil quality, and loss of biodiversity (Řezbová et al., 2023). Moreover, improper use of chemical fertilisers may pose significant risks to human health (Ward, 2009).

The insistent use of chemical fertilisers may result in the accumulation of detrimental heavy metals and nitrates in the soil (Rashid et al., 2023). This pollution jeopardises soil quality and leads to the bioaccumulation of dangerous substances in food crops, fruits, and vegetables, heightening concerns over potential health risks for consumers (Yousefi and Douna, 2023).

In the next 30 years, the global population is projected to exceed 10 billion. Consequently, food supply must augment by 60% to satisfy anticipated demand in 2050 (Kinge et al. 2022). Food distribution and manufacturing need more efficient and sustainable management to prevent supply shortages. Farmers use organic fertilisers produced from recycled resources such as manure, agricultural waste, and municipal sewage, including human excrement (Ju et al. 2005). The excessive use of pesticides and inorganic fertilisers has led to agricultural land degradation, diminished crop yields, and a rise in serious health issues (Bedair et al. 2022). Consequently, biofertilization requires investigation to ensure the provision of healthy food (Ammar 2022).

Inorganic fertilisers, herbicides, and insecticides have profoundly adversely affected the soil ecosystem. This kind of soil alteration will negatively impact future crop production. To guarantee adequate nutrient absorption, crop output, and resilience to abiotic stress, the use of natural plant biostimulants is advocated as an innovative solution to the issues of sustainable agriculture (Povero et al. 2016). Fertilisers are essential for promoting the growth of high-yield crops. N, P, Ca, Mg, K, Fe, Zn, and Some important elements that most crops need in substantial quantities across various soils (White and Brown 2010).

Researchers have focused on using biofertilizers, which provide several advantages over traditional fertilisers, to alleviate the adverse impacts of chemical fertilisers. Biofertilizers provide a more economical and ecologically sustainable use for chemical fertilisers, as they augment soil fertility, enhance nutrient availability, foster sustainable plant development, and alleviate the adverse environmental effects associated with excessive chemical application (Kumar et al., 2022). Kumar et al. (2022) say that biofertilizers improve soil health, stimulate beneficial microbial activity, and boost sustainable agricultural methods. Formulations originating from photosynthetic organisms, especially microalgae, have garnered considerable interest among various biofertilizers available commercially owing to their exceptional capacity to improve soil fertility and stimulate plant development (Çakirsoy et al., 2022).

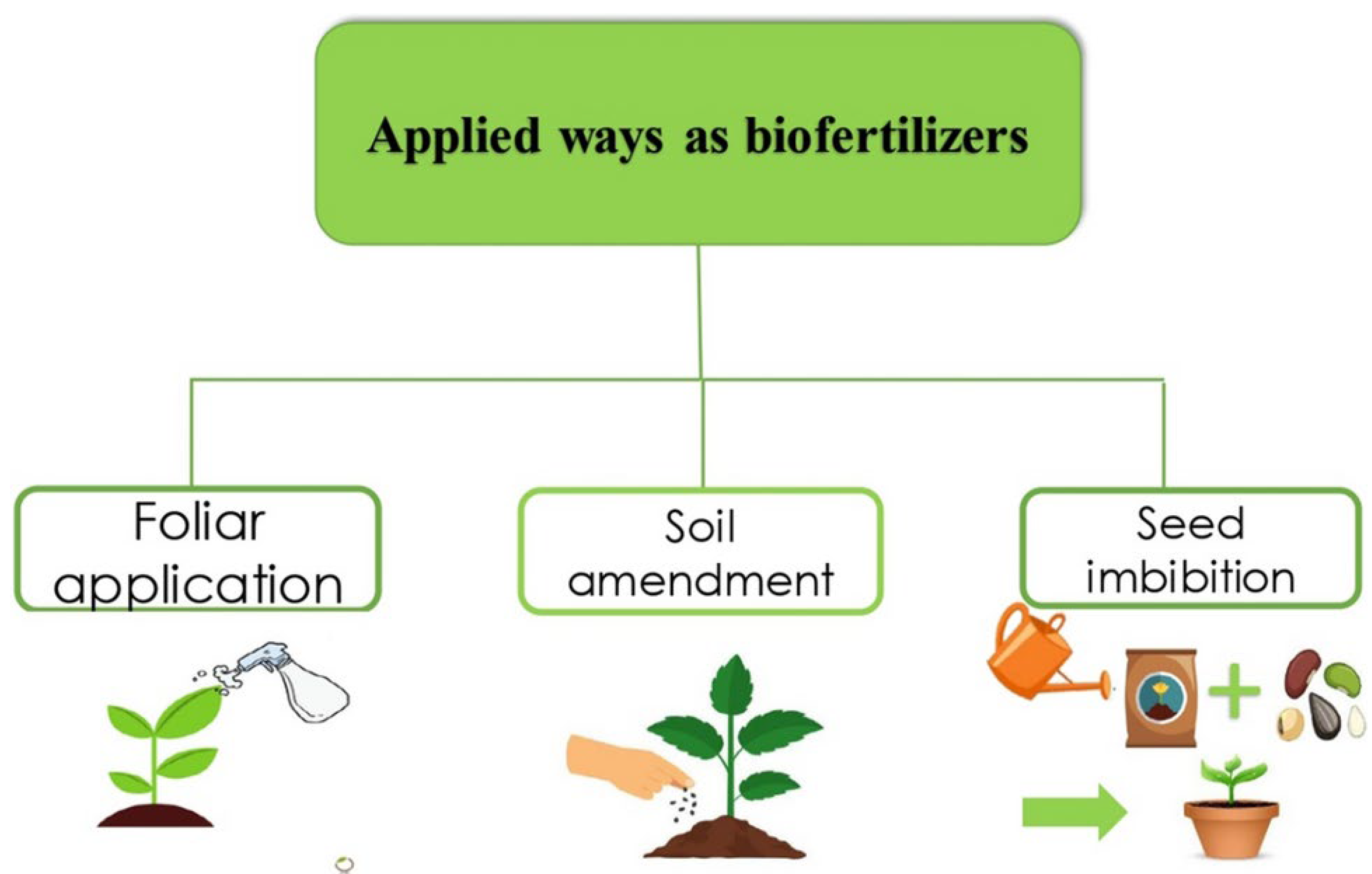

In permaculture, plants are often used to enhance soil fertility. Specific plant residues, such as those from Musa paradisiaca, Coffea arabica, and Lathyrus oleraceus, may be used as soil fertilisers (Singh et al. 2013). Biological fertilizers, which are substances containing microorganisms, enhance soil fertility and stimulate plant development when applied to the soil. Biofertilization is a sustainable agriculture technology that enhances soil nutrient content and, therefore, production. Research indicates that soil microflora may enhance biomass output and soil fertility. It is acknowledged as an appropriate, environmentally sustainable bio-based fertiliser that may be used in agriculture to mitigate pollution. The majority of cyanobacteria has the capability to fix atmospheric nitrogen. Extracts from live organisms may be used as biofertilizers in three distinct methods: foliar application, soil incorporation, or seed imbibition. (

Figure 1).

2. Bacteria as Biofertilizer

Bacterial biofertilizers boost plant growth in several ways (Kumar et al. 2022). This includes the production of plant nutrients or phytohormones for plant absorption, soil chemical mobilisation for nutrient uptake, and plant defence against environmental stress. These processes minimise plant illnesses or death by reducing stresses and increasing pathogen resistance. Multiple plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) have been employed as biofertilizers worldwide for years. They increase agricultural production and soil fertility, perhaps promoting sustainable forestry and agriculture.

Bacterial biofertilizers are growing in popularity as bacterial inoculant technologies improve (Garcia-Gonzalez and Sommerfeld 2016). Study Azotobacter in labs and fields as a biological fertilizer for over an era. Azotobacter fixes nitrogen endophytically in rice rhizospheres and roots, aiding growth. As an endophyte in rice, Azotobacter fixes atmospheric nitrogen in the rhizosphere and produces phytohormones and growth stimulants. Tables 2.1 and 2.2 show that these bacteria fix nitrogen, breakdown insoluble phosphate, and boost plant development (Daniel et al. 2022).

Table 2.1.

Bacteria that fix nitrogen: biological fertilizer.

Table 2.1.

Bacteria that fix nitrogen: biological fertilizer.

| Bacteria |

Examples |

Crops |

Impact |

References |

| Free-living Bacteria |

Azotobacter |

Oryza sativa |

Endorse plant development |

Dar et al., 2021 |

| Symbiotic |

Anabaena azollae |

Oryza sativa |

Increase soil fertility by mounting the microbial pollution in soil |

Abd El-Aal, 2022 |

| Associative symbiotic |

Azospirillum |

Triticum aestivum |

Mitigation of abiotic stresses |

Raffi and Charyulu. 2021 |

Table 2.2.

Microorganisms that solubilize phosphate as a biofertilizer.

Table 2.2.

Microorganisms that solubilize phosphate as a biofertilizer.

| PGPR |

Plants |

Impacts |

References |

| Azotobacter chroococcum |

Triticum aestivum |

Improved results using mutants that solubilize phosphate |

Nosheen et al. (2021) |

| Bacillus megaterium |

Saccharum officinarum |

When sugarcane is grown in pots, yield and yield-related factors are encouraged. |

Chungopast et al. (2021) |

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum |

Glycine max |

lessens the detrimental effects of drought stress on soybean plants’ ability to grow |

Sheteiwy et al. (2021) |

| Pantoea agglomerans |

Solanum

lycopersicum

|

Growth improved |

Mei et al. (2021) |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens |

Ipomoea batatas |

Higher yield |

Santana-Fernández et al. (2021) |

| Rhizobium leguminosarum |

Vicia faba |

Increased yield of faba beans |

Fikadu (2022) |

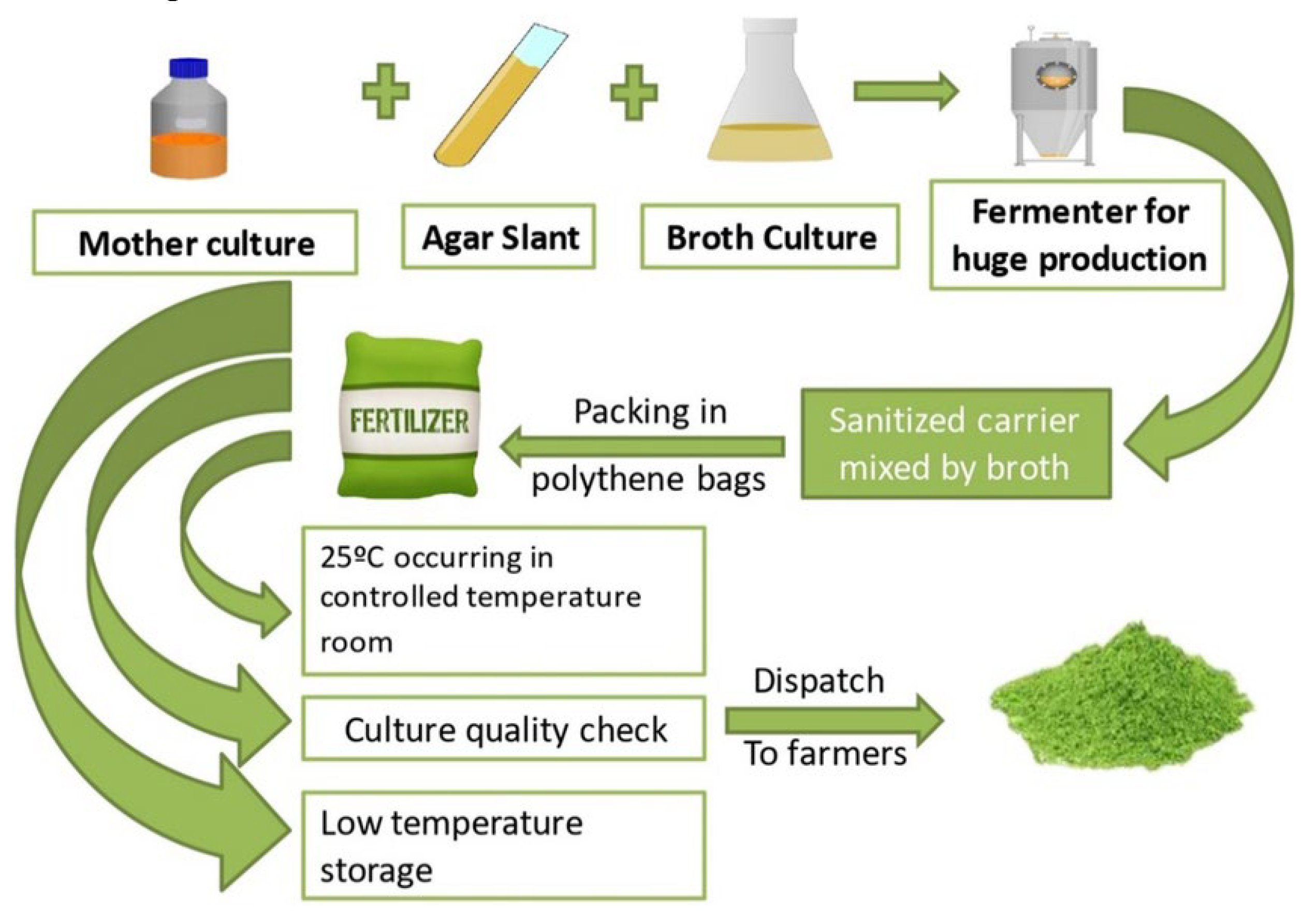

Conversely, cyanobacteria, which comprise a diverse array of creatures, are the most ancient and prolific prokaryote group on the planet. The biomass or extracts of cyanobacteria significantly improved the soil’s chemical and physical characteristics. It is also commonly known that cyanobacteria may produce biologically active chemicals that can be used in phytoremediation of industrial effluent and as an efficient defense against plant diseases (Bedair et al. 2022). As a result, they enhance plant growth and productivity and play a major role in nutrient cycling, phosphorus accessibility, nitrogen-fixation, preservation of the environment, and disease control as natural biofertilizers. Cyanobacteria also convert radiation energy into chemical energy. These biological systems create oxygen through photosynthesis. These species provide us with energy, food, secondary compounds, cosmetics, and medications. Multiple high-value products may be created by growing cyanobacteria on a big scale in an ecologically friendly manner, hence decreasing CO2 levels (Gören-Sağlam, 2021).

Therefore, biofertilizers containing cyanobacteria may eventually replace chemical fertilizers (Bhuyan et al. 2022). Nitrogen-fixing heterocystous filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena azollae lives in the leaf cavities of the eukaryotic water fern Azolla pinnata. Anabaena azollae is grown on synthetic medium like BG-110. Azollae is a valuable bioresource for agriculture, industry, and medicine. Indole acetic acid, gibberellic acid, fatty acids, polysaccharides, and phenolic compounds were extracted from A. azollae. The compounds were microbicidal in vivo and in vitro. Strong nitrogenase activity is a confirmed biofertilization indication for A. azollae. boosted microbial populations boosted dehydrogenase activity and polysaccharide excretion, enhancing soil fertility (Adhikari et al. 2020) (

Figure 2).

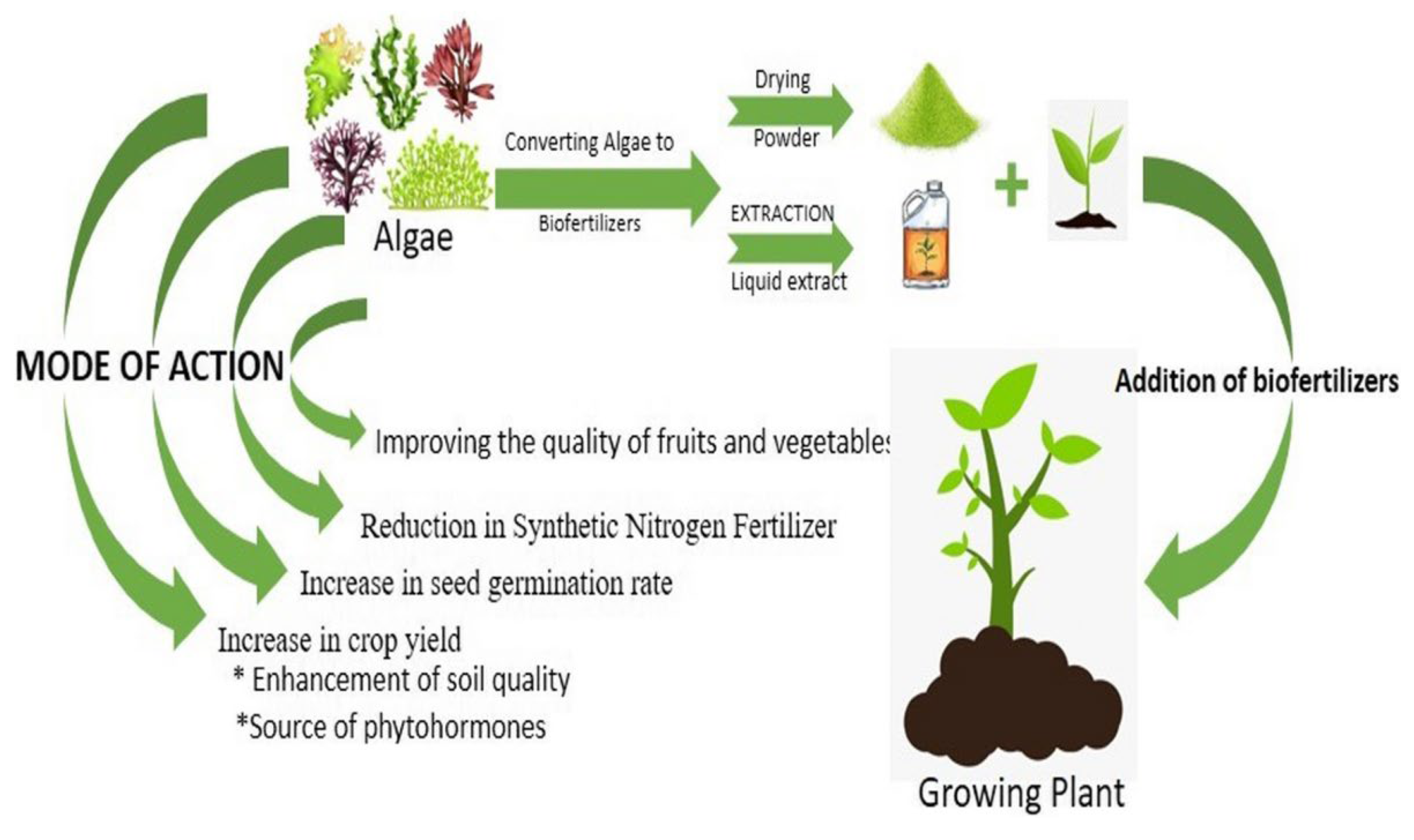

3. Algae as Biofertilizers

Biofertilizers represent the most effective alternatives to synthetic fertilizers. Chatterjee et al. (2017) indicate that algae species possess significant potential for biofertilizer technology, particularly regarding cost-effectiveness and environmental sustainability. The algal process generates substantial byproducts, and its physicochemical properties render it an effective biofertilizer that enhances soil health. Due to its advantages for the environment, technology, and business, algae represent a highly favorable and sought-after bioresource of the twenty-first century (Mahapatra et al. 2018) (

Figure 3).

4. Microalgae as Biofertilizer

According to Fernandes et al. (2023), microalgae are a varied category of tiny, single-celled creatures that include both eukaryotic and prokaryotic microorganisms. Microalgae are seen to be prospective cell factories because of their ability to photosynthesise, which allows them to effectively convert CO2 into biomass and a variety of products, such as nutrients, biofuels, and numerous high-value chemicals (Sun et al., 2023). Because of these qualities, microalgae are widely used as a valuable biological resource in a variety of industries, such as the food business, the manufacturing of biofuel, the wastewater treatment industry, the cosmetics industry, and the pharmaceutical industry (Khaligh & Asoodeh, 2022). Microalgae are becoming more and more popular in agriculture as biofertilizers because of their high concentration of macro- and micronutrients, bioactive and phytohormones compounds. These interactions between crops and the soil microbiome have a positive biochemical impact on the soil ecosystem (Osorio-Reyes et al., 2023).

Additionally, even in situations with low nutrients, microalgae can thrive and efficiently absorb nitrogen and phosphorus due to their exceptional skills in nutrient recovery for their metabolic activities (De et al., 2019). Conversely, this amazing assemblage of species enriches the soil with organic materials. Microalgae improve the structure, ability to hold onto moisture, and general fertility of the soil by releasing organic chemicals and adding biomass. Furthermore, the development of agricultural products may profit from their ability to create metabolites like phytohormones, polysaccharides, and so on (Guo et al., 2020). Because of their capacity to successfully inhibit or limit the growth of diseases, such as bacteria, nematodes, and fungus, microalgae are often referred to as biocontrol agents or biopesticides (Osorio-Reyes et al., 2023). This is accomplished by producing hydrolytic enzymes and biocidal substances such majuscule and benzoic acids (Renuka et al., 2018).

Microalgae have a lot of promise for application in agriculture, but their broad usage in these contexts is still hampered by a lack of understanding and scattered knowledge about how they affect soil and plants under a variety of situations (Alvarez et al., 2021). This book highlights recent developments and uses of these microorganisms in the agricultural sector, offering a thorough overview of how microalgae might improve crop output in a sustainable manner.

Common examples of photosynthetic microalgae are bacterial blue algae and eukaryotic green algae. Their potential application in contemporary agriculture is considerable, given their ability to enhance soil nutrient levels and increase the absorption of both macro- and micronutrients. In addition to improving soil fertility and quality, microalgae can generate metabolites and hormones that promote plant growth (Guo et al. 2020). Microalgae serve as an essential source of biofertilizers for agricultural practices (Dineshkumar et al. 2019). The classification of extracts generated by microalgae, encompassing bioactive and high-value products, is dependent on their physicochemical properties and biological functions. Microalgae display a variety of beneficial traits. Their use in agriculture has attracted considerable interest because of the bioactive compounds that improve plant production (Bello et al. 2021). Microalgal biofertilizers present a renewable and cost-effective solution for farmers aiming to cultivate nutritious organic crops. They promote an environment free from harmful chemicals, positioning themselves as a viable alternative to traditional chemical fertilisers (Dineshkumar et al. 2020). Cyanobacteria play a significant role in enhancing soil organic matter, acting as a potent biofertilizer with the capability to substitute chemical fertilisers. Crop yield and plant growth are enhanced while also promoting soil health (Maqubela et al. 2009). Additionally, algal biomass contains a wealth of metabolites (Jamal Uddin et al. 2019).

5. Fungi as Biofertilizer

Most important taxonomic groups of heterotrophic and eukaryotic living things on Earth are the fungi family, which also includes puffballs, yeast, mildew, and mold. They have benefits for plant development, agricultural yield, and crop protection (Ahmad et al. 2022).

Biofertilizers are composed of biologically active bacterial and fungal strains that improve, increase, change nutrients from an unusable state to useful form (Rastegari et al. 2020). In addition to their intended variety of traits that promote plant development, beneficial fungi help the plant by generating cell wall lysing enzymes such as glycosidase and cellulases, siderophores, gluconase antagonists, and antibiotics. Auxin, gibberellins, cytokinin, zinc, and potassium are also generated together with the solubilization of micronutrients (phosphorus, potassium, and zinc) (Ahmad et al. 2022).

6. Plant Residues as Biological Fertilizers

Similar to other living things, plants may be utilized as biological fertilizers by processing their leftover components, or plant residues, to create environmentally beneficial, biodegradable fertilizers. Banana peels are among the plant leftovers that are utilized as soil biological fertilizers. Because of its flavor and nutritional benefits, bananas are a widely consumed fruit. Large amounts of by-products generated from banana peels are the end result. Research has demonstrated that the macro- and micronutrient-rich peel and bloom of bananas, as well as their anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative stress qualities, all contribute to excellent health. Due to its advantages, such as improving soil fertility, research is being done on turning banana peels into novel, handcrafted products (Kraithong and Issara 2021). The worldwide biochar project (2012) defines banana peel biochar as “a solid compound generated through the thermo-chemical conversion of biomass in an oxygen-constrained environment” (Comino et al. 2020). Biochar from banana peels is a carbon-rich product. Recent studies have focused a lot of attention on banana peel biochar because of its unique property that improves soil quality (Islam et al. 2019)

(Table 6.1).

Table 6.1.

Higher plant as biological fertilizer.

Table 6.1.

Higher plant as biological fertilizer.

| Applied Plant |

Form of Biofertilizer |

Treated Plants |

Effect |

References |

| Banana Peels |

Biochar |

Ipomoea aquatica |

Increase the amount of K added to the soil, yet plant growth is not much increased |

Islam et al., 2019 |

|

Musa paradisiaca L. |

Powder |

Abelmoschus esculentus |

Elevate K and see a noteworthy rise in fruit count, fresh and dry weight per fruit, root length, leaf area, height, and chlorophyll content. |

el Barnossi et al., 2021 |

| Coffee |

Spent coffee ground |

Brassica sp. |

increases soil fertility, organic matter, seed emergence, and minerals (N, K, P, and Cu). |

Chrysargyris et al., 2021 |

| Peas (pulses food) |

Intercropping |

Cereal crops |

Symbiotic interactions between nodules and rhizobia fix atmospheric nitrogen to replenish soil nitrogen. Pulses reduce greenhouse gas emissions, boost soil organic carbon and water retention, and disrupt cereal disease and weed cycles. |

Powers and Thavarajah, 2019 |

| Pomegranate peel |

Water extract |

Salvia officinalis L |

Increased nutritional value, fresh and dry mass, essential oils, carbs, flavonoids, phenolic compounds, and reduction of free radical scavenging compared to plants treated with chemical fertilizers. |

Abd-Rabbu et al., 2021 |

7. Soil Amendment with Compost and Manure

Manure has been used as a fertiliser and trash disposal on farms for millennia (Kumar et al., 2013). Manure was the main source of nutrients for agricultural soil development before chemical fertilisers (Kumar et al., 2013). Cattle dung has been utilised to increase soil fertility by adding organic matter and improving its physical, chemical, and biological qualities (Indraratne et al., 2009).

Manure enhances soil structure and adsorption by lowering volumetric density, increasing porosity, infiltration rate, hydraulic conductivity, and aggregate stability (Abbott et al., 2018). Manure improves soil structure and increases nutrient retention, organic matter content, and water retention by adding nutrients such organic nitrogen or ammonia (Mosebi et al., 2015).

The main benefits of manure application on agricultural land are its ability to improve soil qualities such plant nutrient availability, pH, cation-exchange capacity, and water retention. Bicarbonates, organic anions, and basic cations like Ca2+ or Mg2+ in manure may neutralise soil acidity (Abbott et al., 2018). Manure application increases soil organic matter and carbon, which increases soil cation-exchange capacity (CEC) (Abbott et al., 2018). Due to its high organic matter concentration, manure helps regenerate organic matter in damaged regions and releases nutrients gradually (Mosebi et al., 2015). Adding this waste to the soil may increase species richness, abundance, and variety (Abbott et al., 2018). Soil biodiversity reduces pathogen and insect populations, releases allelochemicals, raises pH, and increases soil microbial antagonists like Actinobacteria (Abbott et al., 2018).

Generally, manure compost may enhance the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of soil, similar to other compost varieties. We identify the three categories of attributes that may be referenced (Lazcano et al., 2008):

The physical qualities of manure compost might fluctuate based on the particular combination of organic components used in the composting process. Nonetheless, manure compost has many physical features, including texture, colour, odour, and moisture content.

The chemical characteristics of manure compost significantly influence its efficacy as a fertiliser. The principal chemical features of manure compost are nutritional composition, organic matter, pH level, salinity, and heavy metal concentration.

The biological features of manure compost pertain to microorganisms, including bacteria, fungus, and protozoa, that facilitate the decomposition of organic materials and the release of nutrients. These bacteria may also inhibit plant diseases and enhance soil structure.

Furthermore, regarding the biological qualities of manure, it is noteworthy that manure compost may attract helpful insects, including earthworms, which contribute to enhancing soil structure and fostering healthy plant development.

When used correctly, manure serves as a significant source of plant nutrients and enhances soil quality and production (Lazcano et al., 2008).

The increase in plant output due to manure application is due to the nutrients supplied to the soil, the organic matter, the improved water retention capacity, and the general enhancement of the soil’s physico-chemical properties (Schlegel et al., 2017). The use of organic nitrogen sources, such as bovine manure, has arisen as a strategy to alleviate reductions in crop yield while concurrently improving soil quality (Hariadi et al., 2016). Soils enriched with manure often demonstrate raised pH levels and improved productivity owing to the augmented availability of nitrogen, phosphate, potassium, calcium, and magnesium for vegetation (Abbott et al., 2018). This organic waste contains essential nutrients necessary for plant growth, and its extended use may benefit plants, even at low application rates (Liu et al., 2018).

Compost enhances soil structure, facilitates physical properties such as water retention and aeration, and enriches chemical features by supplying nutrients and modifying soil pH. Compost enhances the biological characteristics of soil by fostering beneficial microbes and increasing soil fertility (Pergola et al., 2018).

The incorporation of compost into soil enhances its characteristics, including organic matter, retention of water and nutrients, penetration, drainage, compacted opposition, durability against erosion, and tolerance to soil-borne pathogens (Xu et al., 2017). Compost derived from manure offers substantial advantages when integrated into the soil, as the organic matter serves as a nutrient reservoirs, improves the nutrient cycle, boosts cation-exchange capacity (CEC) and pH, and improves the physical properties of the soil, including accumulation, flexibility, volume, pores, root penetration, water-holding capacity, and drainage (Rowen et al., 2019).

Compost promotes the proliferation of soil macrofauna, essential for enhancing soil quality. Moreover, compost gradually releases nutrients that plants can absorb, hence enhancing agricultural output (Xu et al., 2017). Compost comprises vital macronutrients (primarily nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) and micronutrients required for plant development, hence enhancing soil fertility (Pergola et al., 2018). Compost enhances microbial activity, hence improving nutrient availability for plants and generating hormone-like substances that may promote crop development (Pergola et al., 2018).

Completed compost comprises highly active microbial communities that can enhance soil biota and microbial community structure, potentially modifying the functions of microorganisms engaged in the biogeochemical cycle, suppressing diseases, promoting plant growth, augmenting nutrient availability, and improving fertiliser use efficiency and plant yield (Abbott et al., 2018). In contrast to chemical fertilisers, manure-based fertilisers may diminish insect proliferation by enhancing the micronutrient composition in plant tissues and/or by augmenting the synthesis of defensive secondary metabolites (Rowen et al., 2019). Establishing appropriate cow manure treatment rates is essential for providing essential nutrients to plants and enhancing soil characteristics (Schlegel et al., 2017).

8. Green Manure

Green manuring is a classic agricultural practice that involves introducing green plant cells into the soil. As a consequence, it boosts soil fertility, promotes biological activity, improves soil health via nutrient mineralization, and lowers agricultural crop production costs. (Asghar, Kataoka, 2022). Furthermore, it improves organic matter and total soil nitrogen concentrations, potentially improving soil physical conditions (Mandal et al., 2003). Increasing the quantity of green manure in the soil boosts natural carbon, while nitrogen may help rice grow more efficiently. As a consequence, green manure may improve soil fertility, increase crop output, and lower the risk of nitrogen loss (Hu et al., 2022).

8.1. Impact of Green Manure on Crop Growth

Green manuring is a sustainable agriculture approach influences plant morphological characteristics. It efficiently enhances growth parameters by providing enough nutrient levels for crop development (Meng et al., 2019). Decomposed sesbania biomass converts inaccessible nutrients into available forms via soil microorganisms in green manure fields, which shows the impact on growth parameters compared to non-green manure fields and creates sustainable soil conditions for increased crop yield (Sandhya et al., 2022). Significantly, green manure soil fertility and provides a chemical fertilizer substitute. Field tests evaluate its effects on soil physio-chemical characteristics and uptake of nitrogen by crops. It also boosts plant productivity for N fertilizer and increases availability of total organic carbon and nitrogen (Song et al., 2022). It generates an extensive root system, which helps in nutrient uptake, resulting in improved plant growth, a higher leaf area index, and more than the conventional method (application of approved fertilizer dosages alone) (Karmakar et al., 2011). Because of the increased biomass and maximum nutrient absorption in rice crops, it also shows a positive influence on plant growth attributes such as plant height, number of tillers, and dry matter accumulation (Puli et al., 2016)

(Table 8.1). It also promotes nutrient absorption in plants and influences rice development indices such as plant height, tiller number, and leaf area index due to its residual actions compared to other methods (Parmar et al., 2020).

Table 8.1.

Effect of green manure on the growth attributes of different crops.

Table 8.1.

Effect of green manure on the growth attributes of different crops.

| Crop |

Growth parameters |

Without Green Manure |

With Green Manure |

References |

| Rice |

Plant Height

Leaf area index |

103.16 cm

4.21/m2

|

107.91 cm

4.39/m2

|

Parmar et al. (2020) |

| Wheat |

Tillers |

261/m2

|

293/m2

|

Sajjad et al. (2018) |

| Maize |

Plant Height

Cob length |

193.2 cm

15.3 cm |

222.2 cm

16.2 cm |

Sandhya et al. (2022) |

| Soyabean |

Leaf area

Number of branches

Plant Height

Length of root

Leaf number |

96.4 cm28

59.2 cm

31.3 cm

31.6 |

126.4 cm2

8.3

60.2 cm

35.06 cm

33.2s |

Egbe et al. (2022) |

Furthermore, green manuring-treated plots exhibit greater biomass (17.89 tons/ha) and a 7.6 percent rise in fertile tillers in wheat crops compared to non-green manuring fields, as soil moisture availability improves, which is a key component in sustainability (Sajjad et al., 2018). However, they also observed that green manure serves the function of increasing enzyme activity, which makes nutrients more accessible, as well as enhancing soil texture, moisture, and other nutrients. Due to an increase in enzyme activity that releases nutrients into the crop, which influence on crop growth attributes such as plant height, number of branches, collar diameter, length of root, number of leaves, and leaf area than other control plots in the cropping system (Egbe et al., 2022).

9. Conclusion

Biofertilizers are one example of a new eco-friendly technology that will be integral to sustainable farming. Biofertilizers improve soil fertility and crop yields due to their higher nutritional content. Biofertilizers may be derived from a wide range of sources. Bacteria (including Nitrobacter, Azotobacter, and Cyanobacter), microalgae and microfungal (including Glomus spp.) are all components of this category. Another option for biofertilizers is the byproducts of microorganisms, such as plants, fungus, or algae. Supporting the principles of sustainable development, microbes and macro-organism leftovers may boost soil fertility without adding toxins, which is great news for the environment and ecosystems. Plus, they’re biodegradable. Green manure is a farming method that has several environmental and agronomic benefits. It is proven to be an effective way to increase crop productivity while reducing the environmental impact of intensive agriculture techniques. It restores soil fertility and increases production potential and sustainability in agricultural systems. Therefore, it is concluded that the incorporation of green manure improves the physical, chemical, and biological properties of the soil. These improvements have an advantageous effect on crop growth and development and ultimately contribute to ensuring long-term sustainable agricultural production for farming communities.

References

- Abbott, L.K.; Macdonald, L.M.; Wong, M.T. F.; Webb, M.J.; Jenkins, S.N.; Farrell, M. Potential roles of biological amendments for profitable grain production–A review. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2018, 256, 34–50. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-Rabbu, H.S.; Wahba, H.E.; Khalid, K.A. Pomegranate peel modifies growth, essential oil and certain chemicals of sage (Salvia officinalis L. ) herb. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2021, 33, 101978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K.; Bhandari, S.; Acharya, S. An overview of azolla in rice production: a review. Reviews in Food and Agriculture 2020, 2, 04–08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K.; Bhandari, S.; Acharya, S. An overview of azolla in rice production: a review. Reviews in Food and Agriculture 2020, 2, 04–08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Saeed, Q.; Shah, S.M. U.; Gondal, M.A.; Mumtaz, S. Environmental sustainability: challenges and approaches. Natural Resources Conservation and Advances for Sustainability 2022, 243–270. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, A.L.; Weyers, S.L.; Goemann, H.M.; Peyton, B.M.; Gardner, R.D. Microalgae, soil and plants: A critical review of microalgae as renewable resources for agriculture. Algal Research 2021, 54, 102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, A.L.; Weyers, S.L.; Goemann, H.M.; Peyton, B.M.; Gardner, R.D. Microalgae, soil and plants: A critical review of microalgae as renewable resources for agriculture. Algal Research 2021, 54, 102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, E.E.; Aioub, A.A.; Elesawy, A.E.; Karkour, A.M.; Mouhamed, M.S.; Amer, A.A.; El-Shershaby, N.A. Algae as Bio-fertilizers: Between current situation and future prospective. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2022, 29, 3083–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, W.; Kataoka, R. Green manure incorporation accelerates enzyme activity, plant growth, and changes in the fungal community of soil. Archives of microbiology 2022, 204, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedair, H.; Ghosh, S.; Abdelsalam, I.M.; Keerio, A.A.; AlKafaas, S.S. Potential implementation of trees to remediate contaminated soil in Egypt. Environmental science and pollution research 2022, 29, 78132–78151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedair, H.; Rady, H.A.; Hussien, A.M.; Pandey, M.; Apollon, W.; AlKafaas, S.S.; Ghosh, S. Pesticide detection in vegetable crops using enzyme inhibition methods: a comprehensive review. Food Analytical Methods 2022, 15, 1979–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.S.; Saadaoui, I.; Ben-Hamadou, R. “Beyond the source of bioenergy”: microalgae in modern agriculture as a biostimulant, biofertilizer, and anti-abiotic stress. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, P.P.; Nayak, R.; Jena, M.; Pradhan, B. Convoluted role of cyanobacteria as biofertilizer: An insight of sustainable agriculture. Vegetos 2023, 36, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakirsoy, I.; Miyamoto, T.; Ohtake, N. Physiology of microalgae and their application to sustainable agriculture: A mini-review. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 1005991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Singh, S.; Agrawal, C.; Yadav, S.; Rai, R.; Rai, L.C. (2017). Role of algae as a biofertilizer. In Algal green chemistry (pp. 189-200). Elsevier.

- Chrysargyris, A.; Antoniou, O.; Xylia, P.; Petropoulos, S.; Tzortzakis, N. The use of spent coffee grounds in growing media for the production of Brassica seedlings in nurseries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 24279–24290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chungopast, S.; Thongjoo, C.; Islam, A.M.; Yeasmin, S. Efficiency of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria to address phosphorus fixation in Takhli soil series: a case of sugarcane cultivation, Thailand. Plant and Soil 2021, 460, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comino, F.; Cervera-Mata, A.; Aranda, V.; Martín-García, J.M.; Delgado, G. Short-term impact of spent coffee grounds over soil organic matter composition and stability in two contrasted Mediterranean agricultural soils. Journal of Soils and Sediments 2020, 20, 1182–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, A.I.; Fadaka, A.O.; Gokul, A.; Bakare, O.O.; Aina, O.; Fisher, S. ; .. & Klein, A. Biofertilizer: the future of food security and food safety. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1220. [Google Scholar]

- Dar, S.A.; Bhat, R.A.; Dervash, M.A.; Dar, Z.A.; Dar, G.H. Azotobacter as biofertilizer for sustainable soil and plant health under saline environmental conditions. Microbiota and Biofertilizers: A Sustainable Continuum for Plant and Soil Health 2021, 231-254. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, M.H. B.; Calijuri, M.L.; Assemany, P.P.; de Siqueira Castro, J.; de Oliveira, A.C. M. Soil application of microalgae for nitrogen recovery: a life-cycle approach. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 211, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dineshkumar, R.; Subramanian, J.; Arumugam, A.; Ahamed Rasheeq, A.; Sampathkumar, P. Exploring the microalgae biofertilizer effect on onion cultivation by field experiment. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dineshkumar, R.; Subramanian, J.; Gopalsamy, J.; Jayasingam, P.; Arumugam, A.; Kannadasan, S.; Sampathkumar, P. The impact of using microalgae as biofertilizer in maize (Zea mays L. ). Waste and Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbe, E.A.; Soupi, N.M. S.; Awo, M.E.; Besong, G.A. Effects of green manure and inorganic fertilizers on the growth, yield and yield components of soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) in the mount Cameroon region. American Journal of Plant Sciences 2022, 13, 702–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Barnossi, A.; Moussaid, F.; Housseini, A.I. Tangerine, banana and pomegranate peels valorisation for sustainable environment: A review. Biotechnology Reports 2021, 29, e00574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, I.; Pinto, R.; Aguiar, R.; Correia, R. Perspective Application of the Circular Economy in the Blue Biotechnology: Microalgae as Sources of Health Promoting Compounds. Glob. J. Nutr. Food Sci 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikadu, O.; Tekele, C.; Chimdessa, T. (2023). The Response of Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.) to Different Strains of Rhizobium Biofertilizer (Rhizobium leguminosarum) at Horro District, Western Oromia, Ethiopia. In Regional Review Workshop on Completed Research Activities (p. 54).

- Garcia-Gonzalez, J.; Sommerfeld, M. Biofertilizer and biostimulant properties of the microalga Acutodesmus dimorphus. Journal of applied phycology 2016, 28, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gören-Sağlam, N. Cyanobacteria as Biofertilizer and Their Effect under Biotic Stress. Plant Growth-Promoting Microbes for Sustainable Biotic and Abiotic Stress Management 2021, 485-504. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Zou, M.; Liu, C.; Hao, J. Microalgae as biofertilizer in modern agriculture. Microalgae biotechnology for food, health and high value products. 2020, 397-411. [CrossRef]

- Hariadi, Y.C.; Nurhayati, A.Y.; Hariyani, P. Biophysical monitoring on the effect on different composition of goat and cow manure on the growth response of maize to support sustainability. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia 2016, 9, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Huang, R.; Liu, G.; Huang, D.; Huan, H. Effects of green manure combined with phosphate fertilizer on movement of soil organic carbon fractions in tropical sown pasture. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indraratne, S.P.; Hao, X.; Chang, C.; Godlinski, F. Rate of soil recovery following termination of long-term cattle manure applications. Geoderma 2009, 150, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Halder, M.; Siddique, M.A.; Razir, S.A. A.; Sikder, S.; Joardar, J.C. Banana peel biochar as alternative source of potassium for plant productivity and sustainable agriculture. International Journal of Recycling of Organic Waste in Agriculture 2019, 8, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshna, A.; Bokado, K. Green Manure for Sustainable Crop Production: A Review. International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 2024, 14, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Zhang, F.; Bao, X.; Römheld, V.; Roelcke, M. Utilization and management of organic wastes in Chinese agriculture: Past, present and perspectives. Science in China Series C: Life Sciences 2005, 48, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmakar, S.; Prakash, S.; Kumar, R.; Agrawal, B.K.; Prasad, D.; Kumar, R. Effect of green manuring and biofertilizers on rice production. ORYZA-An International Journal on Rice 2011, 48, 339–342. [Google Scholar]

- Khaligh, S.F.; Asoodeh, A. Recent advances in the bio-application of microalgae-derived biochemical metabolites and development trends of photobioreactor-based culture systems. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinge, T.R.; Ghosh, S.; Cason, E.D.; Gryzenhout, M. Characterization of the endophytic mycobiome in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) from a single location using illumina sequencing. Agriculture 2022, 12, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraithong, S.; Issara, U. A strategic review on plant by-product from banana harvesting: A potentially bio-based ingredient for approaching novel food and agro-industry sustainability. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences 2021, 20, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.R.; Park, B.J.; Cho, J.Y. Application and environmental risks of livestock manure. Journal of the Korean Society for Applied Biological Chemistry 2013, 56, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sindhu, S.S.; Kumar, R. Biofertilizers: An ecofriendly technology for nutrient recycling and environmental sustainability. Current Research in Microbial Sciences 2022, 3, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano, C.; Gómez-Brandón, M.; Domínguez, J. Comparison of the effectiveness of composting and vermicomposting for the biological stabilization of cattle manure. Chemosphere 2008, 72, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Guo, T.; Chen, Y.; Meng, Q.; Zhu, C.; Huang, H. Physicochemical characteristics of stored cattle manure affect methane emissions by inducing divergence of methanogens that have different interactions with bacteria. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2018, 253, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, D.M.; Chanakya, H.N.; Joshi, N.V.; Ramachandra, T.V.; Murthy, G.S. Algae-based biofertilizers: a biorefinery approach. Microorganisms for Green Revolution: Volume 2: Microbes for Sustainable Agro-ecosystem 2018, 177-196. [CrossRef]

- Mandal, U.K.; Singh, G.; Victor, U.S.; Sharma, K.L. Green manuring: its effect on soil properties and crop growth under rice–wheat cropping system. European Journal of Agronomy 2003, 19, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqubela, M.P.; Mnkeni, P.N. S.; Issa, O.M.; Pardo, M.T.; D’acqui, L.P. Nostoc cyanobacterial inoculation in South African agricultural soils enhances soil structure, fertility, and maize growth. Plant and Soil 2009, 315, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.; Chretien, R.L.; Amaradasa, B.S.; He, Y.; Turner, A.; Lowman, S. Characterization of phosphate solubilizing bacterial endophytes and plant growth promotion in vitro and in greenhouse. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, H. Green manure application improves rice growth and urea nitrogen use efficiency assessed using 15N labeling. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2019, 65, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosebi, P.E.; Truter, W.F.; Madakadze, I.C. (2015). Manure from cattle as fertilizer for soil fertility and growth characteristics of Tall Fescue (Festuca arundinacea) and Smuts Finger grass (Digitaria eriantha).

- Murata, M.M.; Ito Morioka, L.R.; Da Silva Marques, J.B.; Bosso, A.; Suguimoto, H.H. What do patents tell us about microalgae in agriculture? AMB Express 2021, 11, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosheen, S.; Ajmal, I.; Song, Y. Microbes as biofertilizers, a potential approach for sustainable crop production. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Reyes, J.G.; Valenzuela-Amaro, H.M.; Pizaña-Aranda, J.J. P.; Ramírez-Gamboa, D.; Meléndez-Sánchez, E.R.; López-Arellanes, M.E. ; .. & Martínez-Ruiz, M. Microalgae-based biotechnology as alternative biofertilizers for soil enhancement and carbon footprint reduction: Advantages and implications. Marine Drugs 2023, 21, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar, S.K.; Thanki, J.D.; Gudadhe, N.N.; Pisal, R.R.; Naik, J. Effect of different summer green manures on growth and yield of succeeding kharif rice under integrated nutrient management. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2020, 9, 128–130. [Google Scholar]

- Pergola, M.; Piccolo, A.; Palese, A.M.; Ingrao, C.; Di Meo, V.; Celano, G. A combined assessment of the energy, economic and environmental issues associated with on-farm manure composting processes: Two case studies in South of Italy. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 172, 3969–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povero, G.; Mejia, J.F.; Di Tommaso, D.; Piaggesi, A.; Warrior, P. A systematic approach to discover and characterize natural plant biostimulants. Frontiers in plant science 2016, 7, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.E.; Thavarajah, D. Checking agriculture’s pulse: field pea (Pisum sativum L. ), sustainability, and phosphorus use efficiency. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10, 1489. [Google Scholar]

- Puli, M.R.; Prasad, P.R. K.; Babu, P.R.; Jayalakshmi, M.; Burla, S.R. Effect of organic and inorganic sources of nutrients on rice crop. ORYZA-An International Journal on Rice 2016, 53, 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Raffi, M.M.; Charyulu, P.B. B. N. (2021). Azospirillum-biofertilizer for sustainable cereal crop production: current status. Recent developments in applied microbiology and biochemistry.

- Rashid, A.; Schutte, B.J.; Ulery, A.; Deyholos, M.K.; Sanogo, S.; Lehnhoff, E.A.; Beck, L. Heavy metal contamination in agricultural soil: environmental pollutants affecting crop health. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renuka, N.; Guldhe, A.; Prasanna, R.; Singh, P.; Bux, F. Microalgae as multi-functional options in modern agriculture: current trends, prospects and challenges. Biotechnology advances 2018, 36, 1255–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Řezbová, H.; Slaboch, J.; Mach, J. Emissions from managed agricultural soils in context of consumption of inorganic nitrogen fertilisers in selected EU Countries. Agronomy 2023, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowen, E.; Tooker, J.F.; Blubaugh, C.K. Managing fertility with animal waste to promote arthropod pest suppression. Biological Control 2019, 134, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhya Rani, Y.; Jamuna, P.; Triveni, U.; Patro, T.S. S. K.; Anuradha, N. Effect of in situ incorporation of legume green manure crops on nutrient bioavailability, productivity and uptake of maize. Journal of Plant Nutrition 2022, 45, 1004–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Fernández, A.; Beovides-García, Y.; Simó-González, J.E.; Pérez-Peñaranda, M.C.; López-Torres, J.; Rayas-Cabrera, A. ;... & Basail-Pérez, M. (2021). Effect of a Pseudomonas fluorescens-based biofertilizer on sweet potato yield components. Asian Journal of Applied Sciences (ISSN: 2321–0893), 9.

- Schlegel, A.J.; Assefa, Y.; Bond, H.D.; Haag, L.A.; Stone, L.R. Changes in soil nutrients after 10 years of cattle manure and swine effluent application. Soil and Tillage Research 2017, 172, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheteiwy, M.S.; Ali, D.F. I.; Xiong, Y.C.; Brestic, M.; Skalicky, M.; Hamoud, Y.A. ; .. & El-Sawah, A.M. Physiological and biochemical responses of soybean plants inoculated with Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Bradyrhizobium under drought stress. BMC plant biology 2021, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Bisht, I.S. (Eds.) . (2013). Genetic and genomic resources of grain legume improvement. Newnes.

- Song, S.; Li, L.; Yin, Q.; Nie, L. Effect of in situ incorporation of three types of green manure on soil quality, grain yield and 2-acetyl-1-pyrrolline content in tropical region. Crop and Environment 2022, 1, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Chen, H.; Sun, L.; Wang, Q. Converting carbon dioxide to high value-added products: Microalgae-based green biomanufacturing. GCB Bioenergy 2023, 15, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangarajan, R.; Bolan, N.S.; Tian, G.; Naidu, R.; Kunhikrishnan, A. Role of organic amendment application on greenhouse gas emission from soil. Science of the Total Environment 2013, 465, 72–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, A.F. M. J.; Rakibuzzaman, M.; Wasin, E.W.; Husna, M.A.; Mahato, A.K. Foliar application of Spirulina and Oscillatoria on growth and yield of okra as bio-fertilizer. Journal of Bioscience and Agriculture Research 2019, 22, 1840–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.H. Too much of a good thing? Nitrate from nitrogen fertilizers and cancer. Reviews on environmental health 2009, 24, 357–363. [Google Scholar]

- White, P.J.; Brown, P. Plant nutrition for sustainable development and global health. Annals of botany 2010, 105, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Mou, B. Short-term effects of composted cattle manure or cotton burr on growth, physiology, and phytochemical of spinach. HortScience 2016, 51, 1517–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, H.; Douna, B.K. Risk of nitrate residues in food products and drinking water. Asian Pacific Journal of Environment and Cancer 2023, 6, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).