Submitted:

12 October 2024

Posted:

15 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

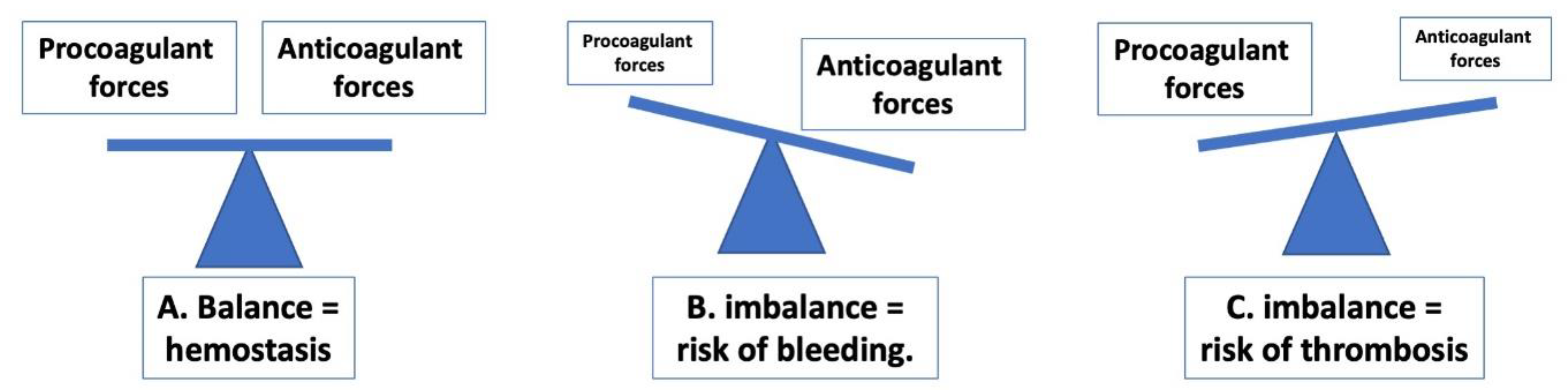

1. Introduction to Hemostasis

2. When hemostasis Fails–Anticoagulant and Procoagulant Therapy

3. A Brief Review of Past Innovative Diagnostic Solutions in Hemostasis

3. Contemporary Innovative Diagnostic Solutions in Hemostasis

3.1. INR Testing

3.2. Hemostasis Instrumentation

3.3. VWF Testing

3.4. Platelet Function Testing

3.5. Viscoelastic Testing

3.6. Other Global Assays of Hemostasis

3.7. Monitoring Hemophilia Treatment

3.8. Diagnosis of TTP and TTP Treatment Monitoring Innovations

3.7. Lupus Anticoagulant Testing

3.8. Anticoagulant Neutralizers

3.9. Harmonization and Standardization

4. Future Innovative Diagnostic Solutions in Hemostasis

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Favaloro EJ, Gosselin RC, Pasalic L, Lippi G. Hemostasis and Thrombosis: An Overview Focusing on Associated Laboratory Testing to Diagnose and Help Manage Related Disorders. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:3-38. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ. Evolution of Hemostasis Testing: A Personal Reflection Covering over 40 Years of History. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2024 Feb;50(1):8-25. [CrossRef]

- Von Clauss A. Gerinnungsphysiologische Schnellmethode zur Bestimmung des Fibrinogens. Acta Haematol. 1957;17:231–237.

- Duncan E, Rodgers S. One-Stage Factor VIII Assays. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1646:247-263. [CrossRef]

- Marlar RA. Laboratory Evaluation of Thrombophilia. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:177-201. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenting PJ, Denis CV, Christophe OD. Von Willebrand factor: how unique structural adaptations support and coordinate its complex function. Blood. 2024 Jul 5:blood.2023023277. [CrossRef]

- Chandran R, Tohit ERM, Stanslas J, Salim N, Mahmood TMT, Rajagopal M. Shifting Paradigms and Arising Concerns in Severe Hemophilia A Treatment. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2024 Jul;50(5):695-713. [CrossRef]

- Moser MM, Schoergenhofer C, Jilma B. Progress in von Willebrand Disease Treatment: Evolution towards Newer Therapies. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2024 Jul;50(5):720-732. [CrossRef]

- Connell NT, Flood VH, Brignardello-Petersen R, Abdul-Kadir R, Arapshian A, Couper S, Grow JM, Kouides P, Laffan M, Lavin M, Leebeek FWG, O'Brien SH, Ozelo MC, Tosetto A, Weyand AC, James PD, Kalot MA, Husainat N, Mustafa RA. ASH ISTH NHF WFH 2021 guidelines on the management of von Willebrand disease. Blood Adv. 2021 Jan 12;5(1):301-325. [CrossRef]

- Hirsh J, de Vries TAC, Eikelboom JW, Bhagirath V, Chan NC. Clinical Studies with Anticoagulants that Have Changed Clinical Practice. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2023 Apr;49(3):242-254.

- Talasaz AH, McGonagle B, HajiQasemi M, Ghelichkhan ZA, Sadeghipour P, Rashedi S, Cuker A, Lech T, Goldhaber SZ, Jennings DL, Piazza G, Bikdeli B. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Interactions between Food or Herbal Products and Oral Anticoagulants: Evidence Review, Practical Recommendations, and Knowledge Gaps. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2024 Sep 17. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ. How to Generate a More Accurate Laboratory-Based International Normalized Ratio: Solutions to Obtaining or Verifying the Mean Normal Prothrombin Time and International Sensitivity Index. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2019 Feb;45(1):10-21. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ, Kershaw G, Mohammed S, Lippi G. How to Optimize Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT) Testing: Solutions to Establishing and Verifying Normal Reference Intervals and Assessing APTT Reagents for Sensitivity to Heparin, Lupus Anticoagulant, and Clotting Factors. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2019 Feb;45(1):22-35. [CrossRef]

- Rodgers S, Duncan E. Chromogenic Factor VIII Assays for Improved Diagnosis of Hemophilia A. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1646:265-276. [CrossRef]

- Platton S, Baker P, Bowyer A, Keenan C, Lawrence C, Lester W, Riddell A, Sutherland M. Guideline for laboratory diagnosis and monitoring of von Willebrand disease: A joint guideline from the United Kingdom Haemophilia Centre Doctors' Organisation and the British Society for Haematology. Br J Haematol. 2024 May;204(5):1714-1731. [CrossRef]

- James PD, Connell NT, Ameer B, Di Paola J, Eikenboom J, Giraud N, Haberichter S, Jacobs-Pratt V, Konkle B, McLintock C, McRae S, R Montgomery R, O'Donnell JS, Scappe N, Sidonio R, Flood VH, Husainat N, Kalot MA, Mustafa RA. ASH ISTH NHF WFH 2021 guidelines on the diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. Blood Adv. 2021 Jan 12;5(1):280-300.

- Favaloro EJ, Pasalic L. Laboratory diagnosis of von Willebrand disease in the age of the new guidelines: considerations based on geography and resources. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2023 Jun 30;7(5):102143. [CrossRef]

- Brown JE, Bosak JO. An ELISA test for the binding of von Willebrand antigen to collagen. Thromb Res. 1986 Aug 1;43(3):303-11. [CrossRef]

- Caron C, Mazurier C, Goudemand J. Large experience with a factor VIII binding assay of plasma von Willebrand factor using commercial reagents. Br J Haematol. 2002 Jun;117(3):716-8. [CrossRef]

- Bonar R, Favaloro EJ. Explaining and reducing the variation in inter-laboratory reported values for International Normalised Ratio. Thromb Res. 2017 Feb;150:22-29. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ, Hamdam S, McDonald J, McVicker W, Ule V. Time to think outside the box? Prothrombin time, international normalised ratio, international sensitivity index, mean normal prothrombin time and measurement of uncertainty: a novel approach to standardisation. Pathology. 2008 Apr;40(3):277-87. [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2005) Procedures for validation of INR and local calibration of PT/INR systems; approved guideline. H54-A, vol. 25, No. 23. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

- Kirkwood TB. Calibration of reference thromboplastins and standardisation of the prothrombin time ratio. Thromb Haemost. 1983;49(3):238-244.

- Favaloro EJ, Arunachalam S, Chapman K, Pasalic L. Continued Harmonization of the International Normalized Ratio (INR) across a large laboratory network: Evidence of sustained low inter-laboratory variation and bias after a change in instrumentation. Am J Clin Pathol. 2024 Jul 18:aqae090. [CrossRef]

- Jonsson PI, Letertre L, Juliusson SJ, Gudmundsdottir BR, Francis CW, Onundarson PT. During warfarin induction, the Fiix-prothrombin time reflects the anticoagulation level better than the standard prothrombin time. J Thromb Haemost. 2017 Jan;15(1):131-139. [CrossRef]

- Onundarson PT, Palsson R, Witt DM, Gudmundsdottir BR. Replacement of traditional prothrombin time monitoring with the new Fiix prothrombin time increases the efficacy of warfarin without increasing bleeding. A review article. Thromb J. 2021 Oct 15;19(1):72. [CrossRef]

- Austin JH, Stearns CR, Winkler AM, Paciullo CA. Use of the chromogenic factor X assay in patients transitioning from argatroban to warfarin therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2012 Jun;32(6):493-501. [CrossRef]

- Sanfelippo MJ, Zinsmaster W, Scherr DL, Shaw GR. Use of chromogenic assay of factor X to accept or reject INR results in Warfarin treated patients. Clin Med Res. 2009 Sep;7(3):103-5. [CrossRef]

- Pontis A, Delanoe M, Schilliger N, Carlo A, Guéret P, Nédélec-Gac F, Gouin-Thibault I. A performance evaluation of sthemO 301 coagulation analyzer and associated reagents. J Clin Lab Anal. 2023 Jun;37(11-12):e24929. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ, Mohammed S, Patzke J. Laboratory Testing for von Willebrand Factor Antigen (VWF:Ag). Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1646:403-416. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed S, Favaloro EJ. Laboratory Testing for von Willebrand Factor Ristocetin Cofactor (VWF:RCo). Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1646:435-451. [CrossRef]

- Frontroth JP, Favaloro EJ. Ristocetin-Induced Platelet Aggregation (RIPA) and RIPA Mixing Studies. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1646:473-494. [CrossRef]

- Seidizadeh O, Peyvandi F. Laboratory Testing for von Willebrand Factor Activity by a Glycoprotein Ib-Binding Assay (VWF:GPIbR): HemosIL von Willebrand Factor Ristocetin Cofactor Activity on ACL TOP®. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:669-677. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ, Mohammed S, Vong R, Pasalic L. Laboratory Testing for von Willebrand Disease Using a Composite Rapid 3-Test Chemiluminescence-Based von Willebrand Factor Assay Panel. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:647-667. [CrossRef]

- Patzke J, Favaloro EJ. Laboratory Testing for von Willebrand Factor Activity by Glycoprotein Ib Binding Assays (VWF:GPIb). Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1646:453-460. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ, Pasalic L, Curnow J. Monitoring Therapy during Treatment of von Willebrand Disease. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2017 Apr;43(3):338-354. [CrossRef]

- Hvas AM, Favaloro EJ. Platelet Function Analyzed by Light Transmission Aggregometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1646:321-331. [CrossRef]

- Fritsma GA, McGlasson DL. Whole Blood Platelet Aggregometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1646:333-347. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar MK, Hinz C. Assessment of Platelet Function by Automated Light Transmission Aggregometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:611-625. [CrossRef]

- Hsu H, Chan MV, Armstrong PC, Crescente M, Donikian D, Kondo M, Brighton T, Chen V, Chen Q, Connor D, Joseph J, Morel-Kopp MC, Stevenson WS, Ward C, Warner TD, Rabbolini DJ. A pilot study assessing the implementation of 96-well plate-based aggregometry (Optimul) in Australia. Pathology. 2022 Oct;54(6):746-754. [CrossRef]

- Chan MV, Lordkipanidzé M, Warner TD. Assessment of Platelet Function by High-Throughput Screening Light Transmission Aggregometry: Optimul Assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:627-636. [CrossRef]

- Pasalic L. Assessment of Platelet Function in Whole Blood by Flow Cytometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1646:349-367. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jourdi G, Ramström S, Sharma R, Bakchoul T, Lordkipanidzé M; FC-PFT in TP study group. Consensus report on flow cytometry for platelet function testing in thrombocytopenic patients: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2023 Oct;21(10):2941-2952. [CrossRef]

- Davidson S. Monitoring of Antiplatelet Therapy. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:381-402. [CrossRef]

- Kundu SK, Heilmann EJ, Sio R, Garcia C, Davidson RM, Ostgaard RA. Description of an in vitro platelet function analyzer--PFA-100. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1995;21 Suppl 2:106-12. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ, Pasalic L, Lippi G. Towards 50 years of platelet function analyser (PFA) testing. Clin Clin Chem Lab Med. 2023;61(5):851-860. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ. Utility of the platelet function analyser (PFA-100/200) for exclusion or detection of von Willebrand disease: A study 22 years in the making. Thromb Res. 2020 Feb 1;188:17-24. [CrossRef]

- Volod O, Runge A. The TEG 6s System: System Description and Protocol for Measurements. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:735-742. [CrossRef]

- Volod O, Runge A. The TEG 5000 System: System Description and Protocol for Measurements. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:725-733. [CrossRef]

- Volod O, Runge A. Measurement of Blood Viscoelasticity Using Thromboelastography. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:709-724. [CrossRef]

- Volod O, Viola F. The Quantra System: System Description and Protocols for Measurements. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:743-761. [CrossRef]

- Reardon B, Pasalic L, Favaloro, EJ. The Role of Viscoelastic Testing in Assessing Hemostasis: A Challenge to Standard Laboratory Assays? J. Clin. Med. 2024 Jun 20;13(12):3612. [CrossRef]

- Depasse F, Binder NB, Mueller J, Wissel T, Schwers S, Germer M, Hermes B, Turecek PL. Thrombin generation assays are versatile tools in blood coagulation analysis: A review of technical features, and applications from research to laboratory routine. J Thromb Haemost. 2021 Dec;19(12):2907-2917. [CrossRef]

- Kanji R, Leader J, Memtsas V, Gorog DA. Measuring Thrombus Stability at High Shear, Together With Thrombus Formation and Endogenous Fibrinolysis: First Experience Using the Global Thrombosis Test 3 (GTT-3). Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2023 Jan-Dec;29:10760296231181917. [CrossRef]

- Chaireti R, Soutari N, Holmström M, Petrini P, Magnusson M, Ranta S, Pruner I, Antovic JP. Global Hemostatic Methods to Tailor Treatment With Bypassing Agents in Hemophilia A With Inhibitors- A Single-Center, Pilot Study. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2024 Jan-Dec;30:10760296241260053. [CrossRef]

- Antovic A, Svensson E, Lövström B, Illescas VB, Nordin A, Börjesson O, Arnaud L, Bruchfeld A, Gunnarsson I. Venous thromboembolism in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: an underlying prothrombotic condition? Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2020 Oct 16;4(2):rkaa056. [CrossRef]

- Yacoub OA, Duncan EM. Chromogenic Factor VIII Assay for Patients with Hemophilia A and on Emicizumab Therapy. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:597-610. [CrossRef]

- Kershaw G, Dix C. Measuring Emicizumab Levels in the Hemostasis Laboratory. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:589-595. [CrossRef]

- Abraham S, Duncan EM. A Review of Factor VIII and Factor IX Assay Methods for Monitoring Extended Half-Life Products in Hemophilia A and B. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:569-588. [CrossRef]

- Kershaw G. Strategies for Performing Factor Assays in the Presence of Emicizumab or Other Novel/Emerging Hemostatic Agents. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2024 Jun 12. [CrossRef]

- Pruthi RK, Chen D. The Use of Bypassing Treatment Strategies in Hemophilia and Their Effect on Laboratory Testing. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2023 Sep;49(6):651-660. [CrossRef]

- Bowyer AE, Gosselin RC. Factor VIII and Factor IX Activity Measurements for Hemophilia Diagnosis and Related Treatments. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2023 Sep;49(6):609-620. [CrossRef]

- Woods AI, Paiva J, Dos Santos C, Alberto MF, Sánchez-Luceros A. From the Discovery of ADAMTS13 to Current Understanding of Its Role in Health and Disease. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2023 Apr;49(3):284-294. [CrossRef]

- Moore GW, Llusa M, Griffiths M, Binder NB. ADAMTS13 Activity Measurement by ELISA and Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:533-547. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ, Chapman K, Mohammed S, Vong R, Pasalic L. Automated and Rapid ADAMTS13 Testing Using Chemiluminescence: Utility for Identification or Exclusion of TTP and Beyond. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:487-504. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ, Mohammed S, Chapman K, et al. A multicentre laboratory assessment of a new automated chemiluminescent assay for ADAMTS13 activity. J Thromb Haemost 2021; 19(2):417-428.

- Singh D, Subhan MO, de Groot R, Vanhoorelbeke K, Zadvydaite A, Dragūnaitė B, Scully M. ADAMTS13 activity testing: evaluation of commercial platforms for diagnosis and monitoring of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2023 Mar 10;7(2):100108.

- Irsara C, Anliker M, Egger AE, Harasser L, Lhotta K, Feistritzer C, Griesmacher A, Loacker L. Evaluation of two fully automated ADAMTS13 activity assays in comparison to manual FRET assay. Int J Lab Hematol. 2023 Oct;45(5):758-765.

- Moore GW, Vetr H, Binder NB. ADAMTS13 Antibody and Inhibitor Assays. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:549-565. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ, Chapman K, Mohammed S, Vong R, Pasalic L. Identification of ADAMTS13 Inhibitors in Acquired TTP. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:505-521. [CrossRef]

- Devreese KMJ, de Groot PG, de Laat B, Erkan D, Favaloro EJ, Mackie I, Martinuzzo M, Ortel TL, Pengo V, Rand JH, Tripodi A, Wahl D, Cohen H. Guidance from the Scientific and Standardization Committee for lupus anticoagulant/antiphospholipid antibodies of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis: Update of the guidelines for lupus anticoagulant detection and interpretation. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Nov;18(11):2828-2839. [CrossRef]

- oore GW, Jones PO, Platton S, Hussain N, White D, Thomas W, Rigano J, Pouplard C, Gray E, Devreese KMJ. International multicenter, multiplatform study to validate Taipan snake venom time as a lupus anticoagulant screening test with ecarin time as the confirmatory test: Communication from the ISTH SSC Subcommittee on Lupus Anticoagulant/Antiphospholipid Antibodies. J Thromb Haemost. 2021 Dec;19(12):3177-3192. [CrossRef]

- Moore GW. Lupus Anticoagulant Testing: Taipan Snake Venom Time with Ecarin Time as Confirmatory Test. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:263-274. [CrossRef]

- Ninivaggi M, de Laat-Kremers R, Tripodi A, Wahl D, Zuily S, Dargaud Y, Ten Cate H, Ignjatović V, Devreese KMJ, de Laat B. Recommendations for the measurement of thrombin generation: Communication from the ISTH SSC Subcommittee on Lupus Anticoagulant/Antiphospholipid Antibodies. J Thromb Haemost. 2021 May;19(5):1372-1378.

- Favaloro EJ, Mohammed S, Curnow J, Pasalic L. Laboratory testing for lupus anticoagulant (LA) in patients taking direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs): potential for false positives and false negatives. Pathology. 2019 Apr;51(3):292-300. [CrossRef]

- Antihepca™-HRRS Heparin Resistant Recalcifying Solution. Available online: https://www.haematex.com/haematex-products/antihepca-hrrs (accessed on 6th October 2024).

- Favaloro EJ, Pasalic L, Lippi G. Oral anticoagulation therapy: an update on usage, costs and associated risks. Pathology. 2020 Oct;52(6):736-741. [CrossRef]

- Frackiewicz A, Kalaska B, Miklosz J, Mogielnicki A. The methods for removal of direct oral anticoagulants and heparins to improve the monitoring of hemostasis: a narrative literature review. Thromb J. 2023 May 19;21(1):58. [CrossRef]

- Exner T, Michalopoulos N, Pearce J, Xavier R, Ahuja M. Simple method for removing DOACs from plasma samples. Thromb Res. 2018 Mar;163:117-122. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ, Pasalic L. Lupus anticoagulant testing during anticoagulation, including direct oral anticoagulants. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022 Mar 15;6(2):e12676. [CrossRef]

- Exner T, Rigano J, Favaloro EJ. The effect of DOACs on laboratory tests and their removal by activated carbon to limit interference in functional assays. Int J Lab Hematol. 2020 Jun;42 Suppl 1:41-48. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ, Mohammed S, Vong R, Pasalic L. Harmonization of Hemostasis Testing Across a Large Laboratory Network: An Example from Australia. Methods Mol Biol. 2023;2663:71-91. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ, Gosselin R, Olson J, Jennings I, Lippi G. Recent initiatives in harmonization of hemostasis practice. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2018 Sep 25;56(10):1608-1619. [CrossRef]

- Exner T, Dangol M, Favaloro EJ. Simplified method for removing DOAC interference in mechanical coagulation test systems – a proof of concept. J Clin Med. 2024 Feb 12;13(4):1042. [CrossRef]

- Nolte CH. Factor XI inhibitors - Rising stars in anti-thrombotic therapy? J Neurol Sci. 2024 Sep 15;464:123157. [CrossRef]

- Connors JM. Factor XI inhibitors: a new class of anticoagulants. Blood Adv. 2024 Oct 8:bloodadvances.2024013852. [CrossRef]

- Nappi F. P2Y12 Receptor Inhibitor for Antiaggregant Therapies: From Molecular Pathway to Clinical Application. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jul 10;25(14):7575. [CrossRef]

- Moser MM, Schoergenhofer C, Jilma B. Progress in von Willebrand Disease Treatment: Evolution towards Newer Therapies. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2024 Jul;50(5):720-732. [CrossRef]

- Harada K, Wenlong W, Shinozawa T. Physiological platelet aggregation assay to mitigate drug-induced thrombocytopenia using a microphysiological system. Sci Rep. 2024 Jun 19;14(1):14109. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Ramasundara SZ, Preketes-Tardiani RE, Cheng V, Lu H, Ju LA. Emerging Microfluidic Approaches for Platelet Mechanobiology and Interplay With Circulatory Systems. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021 Nov 25;8:766513. [CrossRef]

- Yoon I, Han JH, Jeon HJ. Advances in Platelet-Dysfunction Diagnostic Technologies. Biomolecules. 2024 Jun 17;14(6):714. [CrossRef]

- Mangin PH, Neeves KB, Lam WA, Cosemans JMEM, Korin N, Kerrigan SW, Panteleev MA; Subcommittee on Biorheology. In vitro flow-based assay: From simple toward more sophisticated models for mimicking hemostasis and thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2021 Feb;19(2):582-587. [CrossRef]

- Berger JS, Cornwell MG, Xia Y, Muller MA, Smilowitz NR, Newman JD, Schlamp F, Rockman CB, Ruggles KV, Voora D, Hochman JS, Barrett TJ. A Platelet Reactivity ExpreSsion Score derived from patients with peripheral artery disease predicts cardiovascular risk. Nat Commun. 2024 Aug 20;15(1):6902.

- Rashidi HH, Bowers KA, Reyes Gil M. Machine learning in the coagulation and hemostasis arena: an overview and evaluation of methods, review of literature, and future directions. J Thromb Haemost. 2023 Apr;21(4):728-743. [CrossRef]

- Favaloro EJ, Negrini D. Machine learning and coagulation testing: the next big thing in hemostasis investigations? Clin Chem Lab Med. 2021 Mar 3;59(7):1177-1179. [CrossRef]

| Test Abbreviation |

Test | What the test measures | What the test is used for | What else is the test sensitive to? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT | Prothrombin time | Tissue factor (TF) (also called extrinsic) pathway plus common pathway | Assessment of factor deficiency (I, II, V, VII, X). Monitoring of Vitamin K antagonist (VKA; e.g., warfarin) therapy (typically as the INR) Screen for disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) |

Various anticoagulants (e.g., unfractionated heparin [UH] in excess to heparin neutralizer capacity, direct oral anticoagulants [DOACs]) |

| INR | International normalized ratio | Same as PT, but reflective of a normalized ratio | Used to monitor patients on VKA therapy | Same as PT |

| APTT | Activated partial thromboplastin time | Contact factor (also called intrinsic) pathway plus common pathway | Assessment of factor deficiency (I, II, V, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII) Monitoring of UFH therapy Screen for DIC |

Various anticoagulants (e.g., DOACs) |

| TT | Thrombin Time | Measure of fibrinogen clotting activity | Screen for fibrinogen deficiency. Screen for UFH and other anti-II agents (e.g., dabigatran) Screen for DIC |

Various anticoagulants (e.g., lepirudin, bivalirudin) |

| D-D | D-dimer | The fibrin degradation product called D-dimer | Screen for venous thrombosis (e.g., deep vein thrombosis [DVT]; pulmonary thrombosis [PE]). Screen for DIC |

Depending on antibody used in assay, potentially variously sensitive to other fibrin or fibrinogen degradation products |

| Fib or FGN | Fibrinogen | Fibrinogen level (fibrinogen is the major coagulation protein) | Assessment of congenital or acquired fibrinogen deficiencies or abnormalities | Some assays may be affected by very high levels of some anticoagulants (e.g., UFH, dabigatran) |

| Test Abbreviation |

Test | What the test measures | What the test is used for | What else is the test sensitive to? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | Antithrombin | Antithrombin level or activity | Quantitation of antithrombin activity | Depending on how assay is performed (i.e., as based on anti-FXa or anti-FIIa) may be sensitive to various anticoagulants (e.g., DOACs) |

| PC | Protein C | Protein C level or activity | Quantitation of Protein C activity | Clot based assays may be affected by various anticoagulants, including DOACs. |

| PS | Protein S | Protein S level or activity | Quantitation of Protein S level or activity | Clot based assays may be affected by various anticoagulants, including DOACs. |

| LA | Lupus anticoagulant | Presence or absence of LA | To exclude/identify LA for diagnosis of APS or as a cause of APTT prolongation To help determine anticoagulant treatment for inpatient pending discharge |

Various anticoagulants depending on assays/reagents employed |

| Anti-Xa or anti-FXa | Anti-factor Xa | Level of various anticoagulants depending on test set up | To quantify levels of UH, LMWH, direct and indirect anti-FXa agents (e.g., apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, fondaparinux) | Each ‘specific’ anti-FXa assay is variously sensitive to the other anti-FXa agents |

| DTI or dTT | Direct thrombin inhibitor or dilute thrombin time | Level of various anticoagulants depending on test set up | To quantify levels of anti-FIIa agents (e.g., dabigatran) | Each ‘specific’ anti-FIIa assay potentially sensitive to other anti-FIIa agents |

| FII, FV, FVII, FVIII, FIX, FXI, FXII | Factors II, V, VII, VIII, IX, XI, XII | Level and activity of these clotting factors | To quantify these factor levels | All clot-based assays variably sensitive to various clinical anticoagulants |

| VWF | von Willebrand factor | Level and activity of VWF | To quantify VWF and its various activities | Different functional assays tend to be ‘specific’ for a particular VWF activity |

| ADAMTS-13 | ADAMTS-13 | Level and activity of ADAMTS-13 | To quantify ADAMTS-13 activity | May depend on assay |

| PFS | Platelet function studies | Platelet activity | To quality platelet activity or diagnose platelet dysfunction | Depends on assay |

| Test Abbreviation |

Test | What the test measures | What the test is used for | How is the test performed? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VWF:Ag | VWF antigen | Level of VWF | Quantitation of VWF level | Usually, LIA or ELISA; sometimes CLIA |

| RIPA | Ristocetin induced platelet agglutination/ aggregation | Activity of VWF binding to GPIb | Qualification of VWF GPIb binding activity | Platelet agglutination assay, usually on platelet aggregometer |

| VWF:RCo | VWF ristocetin cofactor | Activity of VWF binding to GPIb | Quantitation of VWF GPIb binding activity | Platelet agglutination assay, usually on automated hemostasis analyzer, sometimes on platelet aggregometer. |

| VWF:CB | VWF collagen binding | Activity of VWF binding to collagen (a matrix protein exposed by vascular damage) | Quantitation of VWF collagen binding activity | Usually, ELISA; sometimes CLIA. |

| VWFpp | VWF propeptide | Level of VWF propeptide | To quantify VWF propeptide as a marker of VWF clearance | ELISA |

| VWF:FVIIIB | VWF factor VIII binding | Activity of VWF binding to FVIII | Quantitation of VWF FVIII binding activity | ELISA |

| VWF:GPIbR | VWF GPIb recombinant | Activity of VWF binding to recombinant GPIb | Quantitation of VWF GPIb binding activity | Usually, latex agglutination assay on automated hemostasis analyzer, sometimes CLIA. |

| VWF:GPIbM | VWF GPIb (recombinant) mutant | Activity of VWF binding to recombinant mutated GPIb | Quantitation of VWF GPIb binding activity | Usually, latex agglutination assay on automated hemostasis analyzer, sometimes ELISA. |

| Test / Parameter |

Anti-FXa DOACs | Anti-FIIa DOACs (dabigatran) | VKAs | Heparins (UH/LMWH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT/INR Depends on: |

- / ↑ / ↑↑ DOAC, [DOAC], reagent |

- / ↑ [DOAC], reagent |

↑ / ↑↑ / ↑↑↑ [VKA], reagent |

- / ↑ heparin type, [heparin], presence of neutralizers |

| APTT Depends on: |

- / ↑ DOAC, [DOAC], reagent |

↑ / ↑↑ [DOAC], reagent |

↑ / ↑↑ [VKA], reagent |

↑ / ↑↑ / ↑↑↑ heparin type, [heparin], reagent |

| TT Depends on: |

- | ↑↑↑ | - | ↑ / ↑↑ / ↑↑↑ heparin type, [heparin], reagent |

| D-D | - | - | - | - |

| Fib Depends on: |

- / ↓ [DOAC], reagent |

- / ↓ [DOAC], reagent |

- | - / ↓ heparin type, [heparin], reagent |

| Anti-FXa assays Depends on: |

↑ / ↑↑/ ↑↑↑ [DOAC] |

- | - | ↑ / ↑↑/ ↑↑↑ [heparin] |

| Factor assays Depends on: |

↓ / ↓↓ [DOAC] |

↓ / ↓↓ [DOAC] |

↓ / ↓↓ Factor type, [VKA] |

- ( / ↓ ) heparin type, [heparin] |

| PC, PS Depends on: |

- / ↑ [DOAC], reagent |

- / ↑ [DOAC], reagent |

↓ / ↓↓ [VKA] |

- ( / ↓ ) heparin type, [heparin], reagent |

| AT Depends on: |

- / ↑ [DOAC], reagent |

- / ↑ [DOAC], reagent |

- |

- / ↑ heparin type, [heparin], reagent |

| APCR Depends on: |

- / ↑ [DOAC], reagent |

- / ↑ [DOAC], reagent |

- / ↑ [VKA], reagent |

- / ↑ heparin type, [heparin], reagent |

| LA Depends on: |

- / ↓ / ↑ / ↑↑ DOAC type/ [DOAC], reagent |

↑ / ↑↑ [DOAC], reagent |

- / ↓ / ↑ / ↑↑ [VKA], reagent |

- / ↑ heparin type, [heparin], reagent, presence of heparin neutralizers |

| VWF, Platelet function |

- | - | - | - |

| TGA Depends on: |

↓ / ↓↓/ ↓↓↓ DOAC type/ [DOAC], reagent |

↓ / ↓↓/ ↓↓↓ [DOAC], reagent |

↓ / ↓↓/ ↓↓↓ [VKA], reagent |

↓ / ↓↓/ ↓↓↓ heparin type, [heparin], reagent |

| VEA | ↑ / ↑↑ [DOAC], reagent, system |

↑ / ↑↑ [DOAC], reagent, system |

- / ↑ [VKA], reagent, system |

- / ↑ heparin type, [heparin], reagent, system |

| Monitor or measure with: | Specific anti-FXa assays | Specific anti-FIIa assay (e.g., direct thrombin inhibitor [DTI) assay. Ecarin based assays |

PT/INR | APTT, anti-FXa assay |

| Neutralize with: | Activated charcoal (e.g., DOAC-Stop) | Activated charcoal (e.g., DOAC-Stop) | - (mixing studies) | polybrene, hepzyme |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).