1. Introduction

The extraction techniques needed to gather data that are stored in databases behind firewalls are significantly different from browsing web page data on the internet [

1]. The standard tools used to access deep web data are wrappers [

2] and more recently are RESTful APIs [

3]. Word-of-mouth [

4] and web crawlers [

5] also played a significant role in the generation of the resource indices such as MBDL [

6] or Pathguide [

7]. While the compiled resource indices help with the discovery and identification of interesting data sources and analysis tools users need, the process is completely manual, sluggish, and limited. They are slow update and include new resources, and do not serve unique needs users may have. In particular, they do not actively find resources of interest that are not already found and indexed in the resource list.

Linked Open Data (LOD), on the other hand, has emerged as a promising approach to provide interconnected, machine-readable datasets, but its effectiveness is often hampered by issues related to data quality and accessibility. While LOD emphasizes openness, the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) principles [

8] extend this concept, revealing significant gaps in compliance among LOD resources [

9]. Tools such as the FAIR-Checker [

10] have been developed to evaluate and improve FAIRness in LOD; by utilizing standardized metrics and criteria, this tool enhances transparency and reliability in LOD practices. However, widespread adoption of FAIR principles remains a challenge, hindering the full realization of LOD’s potential in supporting scientific inquiry and data-driven research. It is interesting to note that LOD does not imply FAIR, or vice-versa [

11], and both of these concepts are not supported by standards to follow and thus are very hard to achieve. The question that remains open still, how users can find useful and most relevant resources accessible over the open internet?

In this paper we introduce the concept of data foraging and sharing in a community resource ecosystem [

12] that will be curated [

13] and will evolve with time [

14]. We believe the ingredients required to architect such an ecosystem are in place and a careful integration of them is finally possible. We discuss the architecture and functionalities of the proposed system called

SoDa (stands for Solo Data Forager). In SoDa, we integrate three basic subsystems – a resource recommender system, a data access protocol design or wrapper system, a query processing system with the help of a schema matcher to support interoperability, and a curation system for knowledge evolution. We illustrate the functionality of SoDa using an example from life sciences research.

2. Related Research

Powerful data integration systems such as Galaxy [

15] and Taverna [

16] could be limiting for some applications. For example, finding new resources and integrating them into Galaxy tool set requires significant expertise and coordination with the Galaxy developer team, and thus not suitable for ad hoc spur of the moment usage for novel queries – requires planning, coordination and technical knowledge. Taverna, on the other hand, allows user initiated resource integration, but requires resources’ web service compliance. Even when they do, the required tooling is extensive and requires significant preparation and coding know how. In both systems, implementing a scientific inquiry of the form discussed in

Section 3.1 will be extremely difficult, if not impossible, by a biologist who is not computationally savvy, and there are a large number of such biologists.

Recent efforts such as Voyager [

17] for data discovery and integration though a step in the right direction, it does not support many needs that we address in SoDa, some of which are expressed in [

18]. Such deficiencies in the contemporary system that supports an end-to-end data discovery, integration and querying [

19] are leading to custom application developments such as BioBankUniverse [

20] and DZL [

21]. As discussed in ProAb [

22], the landscape of data discovery, scientific inquiry and integration is being reshaped by the emerging LLM technology. New application design platforms will need to support not only complex SQL queries post discovery and integration, they must have to support automatic computation of predictive and other forms of analyses only possible through incorporation of machine learning capabilities with querying engines. The SoDa system we introduce in this paper approaches the science of scientific inquiry from this emerging perspectives.

3. SoDa Architecture

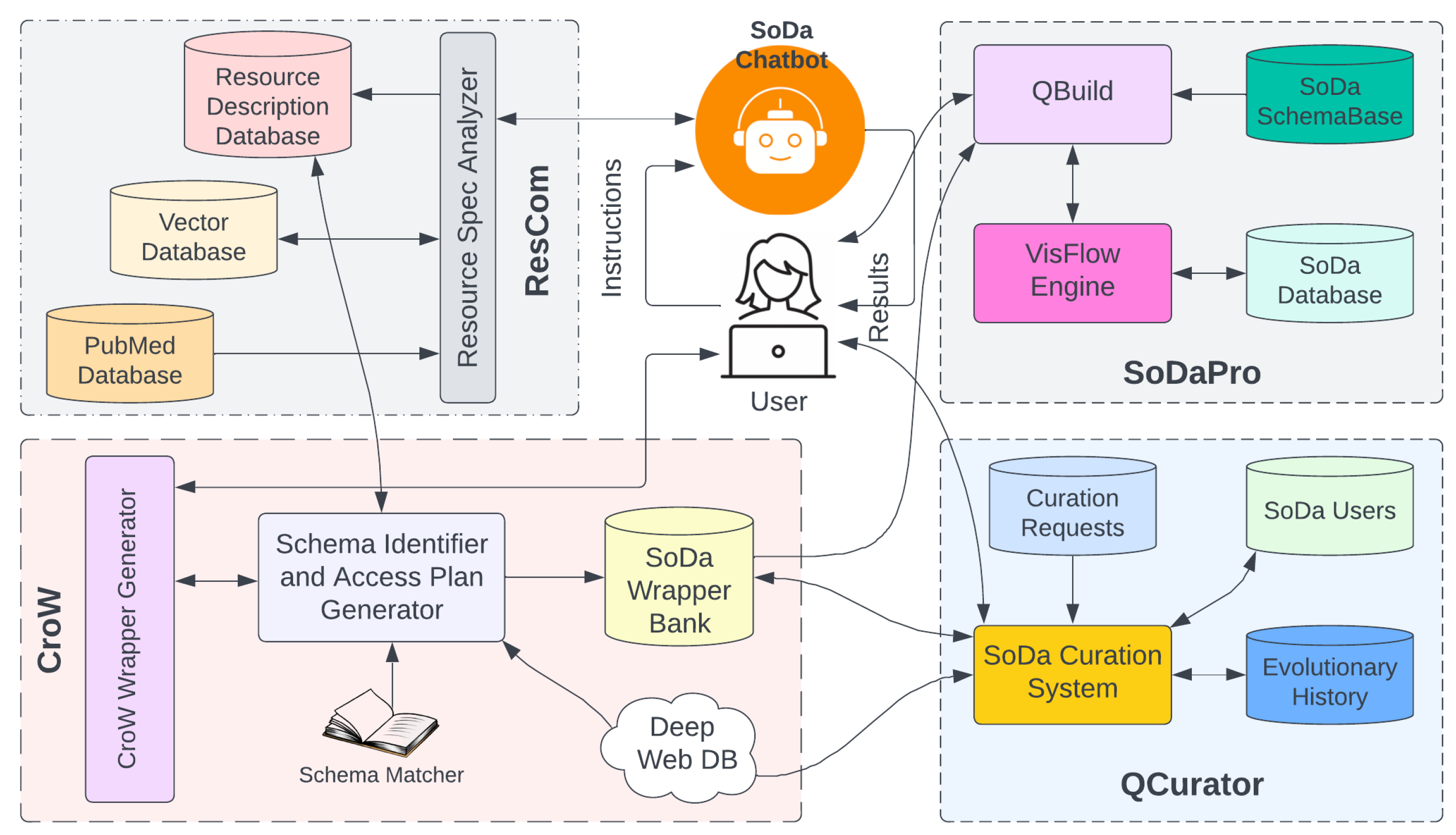

As shown in the conceptual model of SoDa in

Figure 1, it has four major components. In the sections to follow, we will discuss those components briefly. As a preamble to the discussion of the architecture of SoDa, we introduce a potential scientific expedition a biologist might want to do using our cloud-based analysis platform for open science over linked open data.

3.1. Scientific Inquiry

In their quest to establish a definitive link between defects in sperm and male infertility [

23], a biologist might want to follow the steps below once semen samples from both fertile and infertile men are collected and sequenced (among several other steps before and after).

Perform differential expression analysis to identify RNAs that are significantly differentially expressed between fertile and infertile men using commonly used tools such as DESeq2, edgeR, or Limma.

Use tools like DAVID, Enrichr, or clusterProfiler to perform Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analysis on the differentially expressed RNAs.

Identify biological processes, molecular functions, and pathways that are significantly associated with the differentially expressed RNAs.

There are multiple different levels at which this project could be approached depending on the biologist or their expertise. For example, a more established researcher in fertility research may already have collected sperm samples from both fertile and infertile men, isolated RNA from these sperm samples, identified and quantified the RNA molecules present in the sperm samples using RNA sequencing and learned about the RNA profiles of fertile and infertile men before entering differential expression analysis.

An alternative to come to this stage is to use publicly available data at GEO [

24] or SRA [

25] databases, and start right away. However, the querying abstraction levels could be highly varied. ProAb [

22] explored the interesting possibility of asking this query at the highest possible abstraction level in natural English, likely as follows:

Is there a link between human spermatozoal rna and infertility? Could I establish the link computationally?

and developing a candidate workflow that could be executed fully automatically. However, a cognate research in BioNursery [

26] demonstrated that significant technological and knowledge gaps exist to fully achieve such an approach, and often, substantial human involvements are necessary.

In SoDa, the abstraction levels supported help find relevant data and tools automatically but requires users’ involvement in selecting, isolating and generating a computational information extraction procedure that can be used in automation. Once collected and archived, and once users already have a well articulated computational process in mind, they are able to develop a computational pipeline to implement a scientific inquiry using the smart SoDa GUI as described in the following sections.

3.2. Resource Recommendation

Existing resources in SoDa can be browsed from a searchable index, or a specification in the form of a paragraph for the resource needs can be used as a search key in natural English. For example,

Need to find normalized sperm RNA-seq expression data for differential expression analysis (using DESeq2, edgeR, or Limma).

The Resource ReCommender system ResCom accepts this request suggests a ranked list of databases prioritizing the most relevant at the top. Not only ResCom suggests the databases, it also generates a possible scheme of the table that can be accessed at an internet location, i.e., a URL.

In response to the above request, for example, ResCom will first search for a matching data set in SoDa archive. In SoDa, all table schemes are semantically described in some detail using natural language and their possible usage is also included in these descriptions. These descriptions are stored in SoDa’s vector database for a possible linguistic analysis using a LLM such as ChatGPT to ascertain query relevance.

In the event a table could not be identified, or user requests for an external search, ResCom uses PubMed abstracts as the first level of descriptors of data to find a match. If a sufficient match is found, the list of abstracts are organized in a decreasing order of ranked list and vectorized for semantic matching. Database links found in the abstracts are explored exhaustively using link hoping to identify a database with the closest match and presented to the user for review with two options – accept or search next. The search ultimately ends in a success or failure.

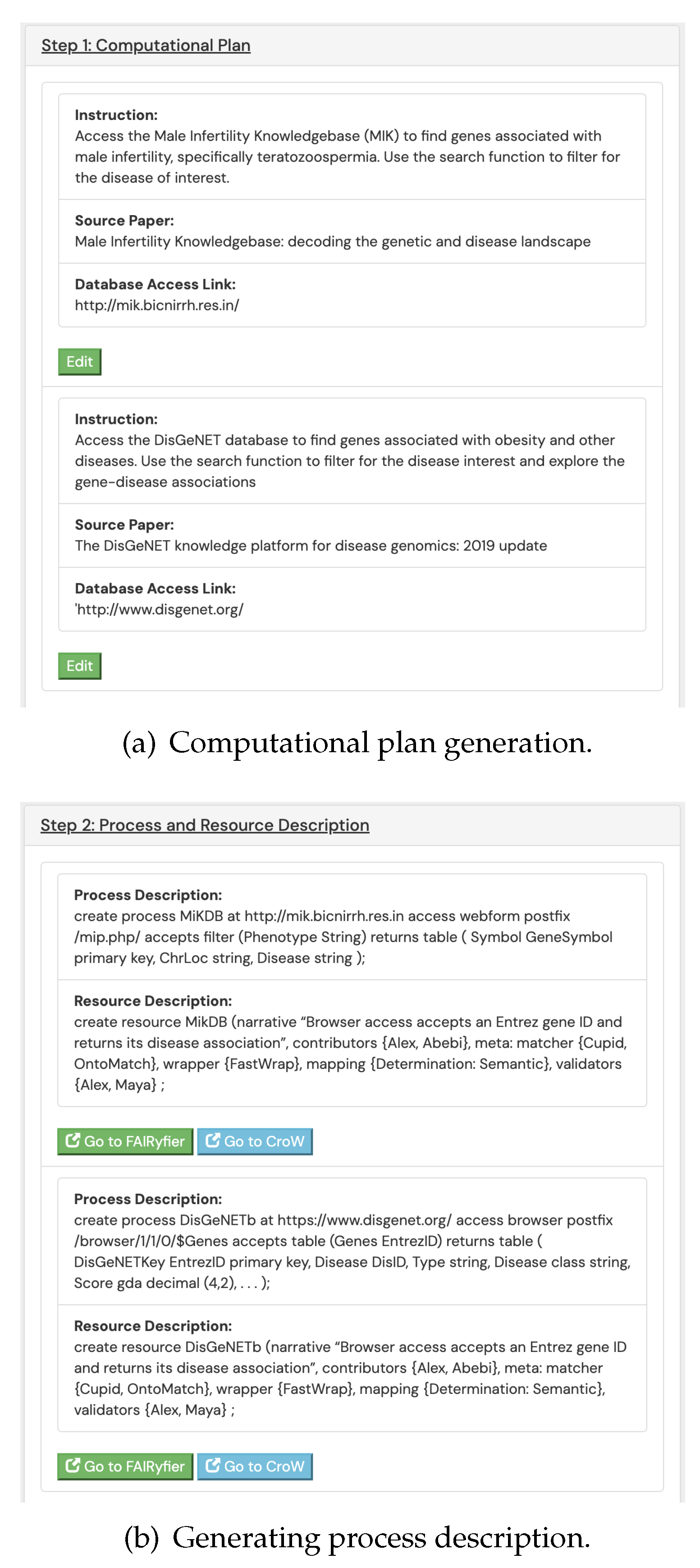

Successful identification process of resources undergo a secondary step. In this step, a machine readable and editable description on the nature and capabilities of the resource is generated (see

Figure 2 showing this process for the resource description generation for the DisGeNET

1 database). The resource description can be used in multiple different ways. But the major use of the descriptions is by the workflow generation system Needle discussed in

Section 3.5. Needle uses resource descriptions to identify schema heterogeneity and schema matchers for their resolution, suitable wrappers for data access, and trust-worthiness of the resource. A crowd computing approach is adopted to ensure accuracy and usefulness of the generated resource description within a community knowledge sharing ecosystem.

3.3. Accessing Resources

Once an external to SoDa resource is identified, a wrapper needs to be generated to facilitate real time online access and ensure successful extraction. In SoDa, resources are of two types – a deep web database

2, or an online analysis tool that returns a table on appropriate submission of input parameters, again likely using forms. In SoDa, the underlying data model is relational, and thus all its operations are conceived using a tabular representation of data although the engine is capable of processing, TXT, CSV, XML, and JSON formatted data.

However, developing an access protocol for such resources is mostly a manual process largely because each one is unique, but follows a simple mathematical relation as follows.

where

is a function (the wrapper generator) that maps a resource

(represented by a URL) into a function

of the form

Thus,

or,

, where

is a URL and

is a table. The access plan we develop is a learned function

from

that would transform an input table

t into a result table

by the resource at the URL

u.

To be able to develop the function

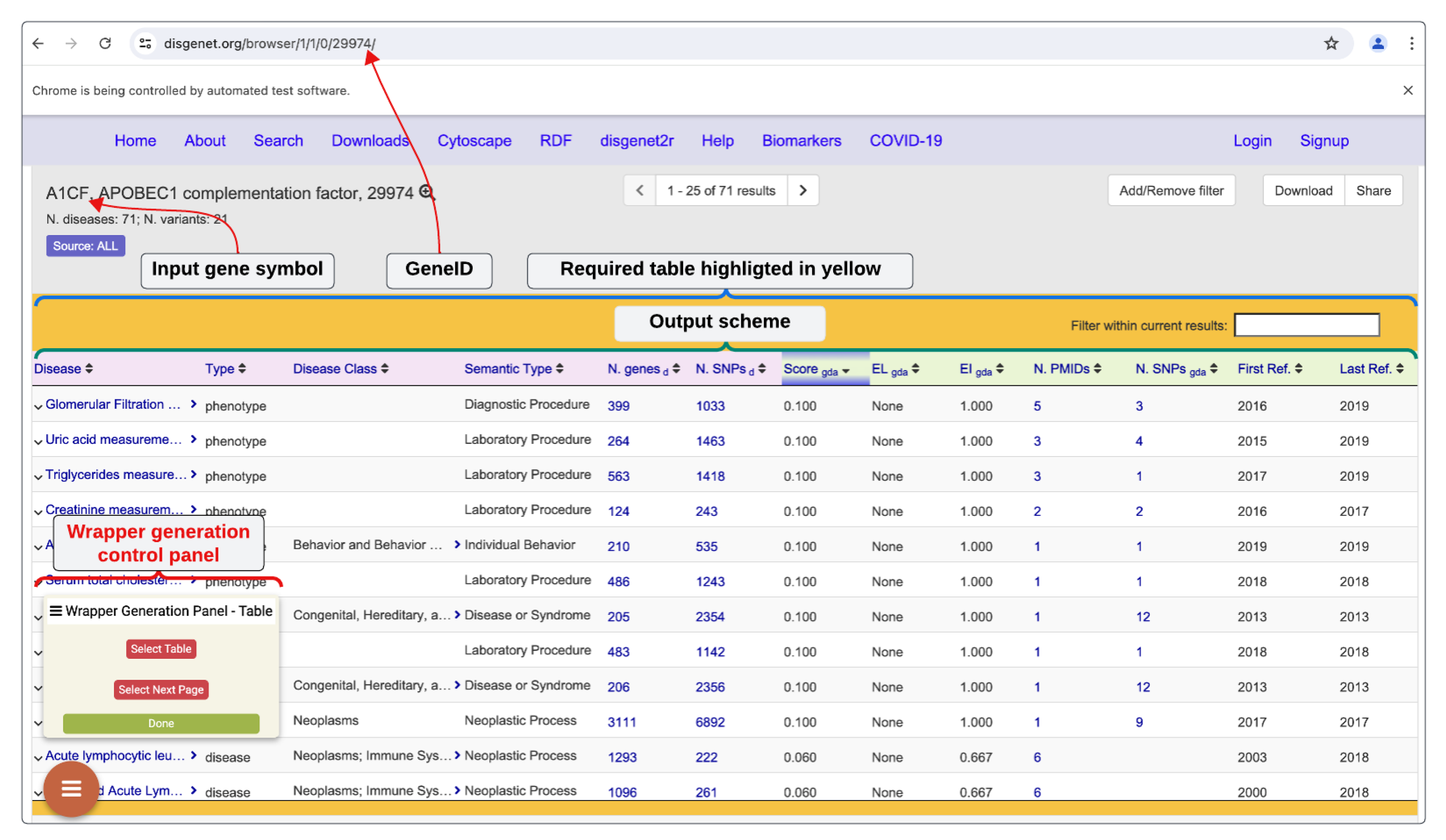

, we use a GUI enabled public wrapper generation system called

CroW (stands for

Crowd

Wrapper Generator). CroW supports visual tools and functions to help users help CroW to learn the form behavior and data layouts so that a formula can be learned using which CroW will be able to recreate the access plan for a site

u when requested by a query in real time (wrapper generation process for the DisGeNET database is shown in

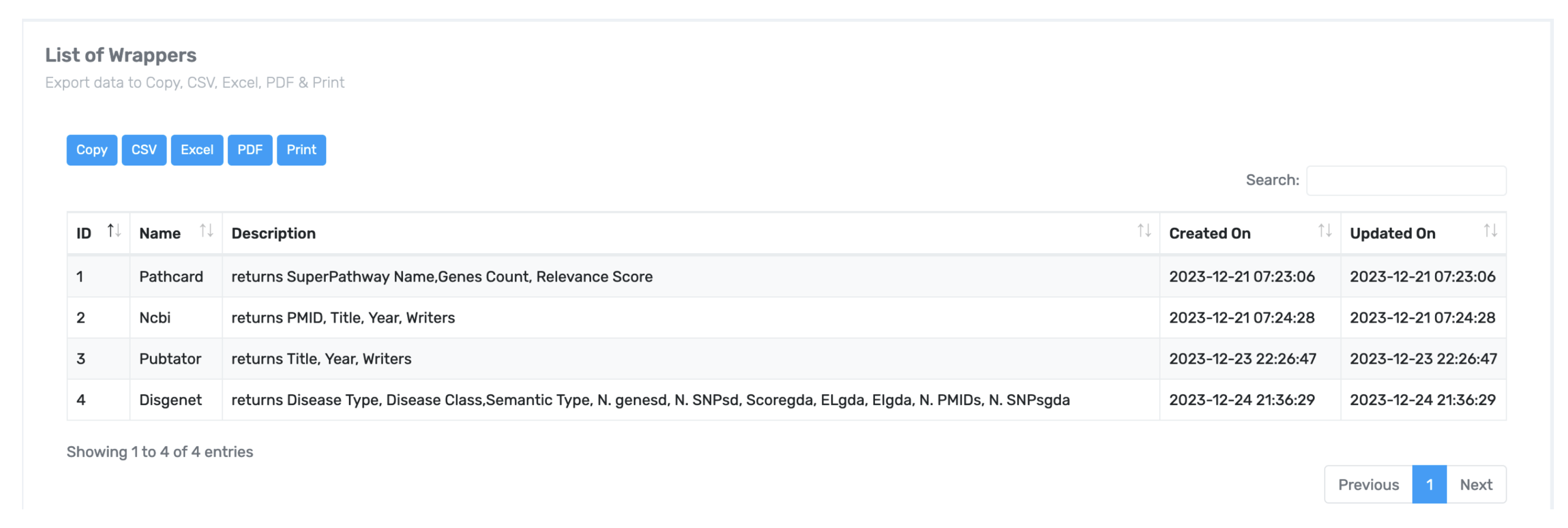

Figure 3). Once a wrapper is generated and tested, it can archived in a searchable wrapper bank for community use, as shown in

Figure 4.

3.4. Application Design

Application design using the in SoDa always involves registered resources in SoDa, and never involves resources SoDa has no access plans generated for. SoDa supports a graphical query builder and allows fairly complex query generation, and computed view materialization, either temporarily or indefinitely. The application designer is called QBuild (stands for Query Builder). Except for the directly stored tables (extensional tables), all references to a table are virtual, which means, a reference to a table on the internet is made through the use of a wrapper available in SoDa wrapper database.

3.4.1. SoDa Query Language

QBuild uses BioFlow query language construct extract [

27] to access the referenced tables in real time and treats the extracted tables as a traditional table in the back end relational database MySQL. The extract statement has the following general form.

extract

using wrapper W, mapper M, filler F

at

submit r

In the extract statement above, the output scheme of is and the input scheme is the scheme of r.

BioFlow approached the deep web resource querying problem declaratively. In this approach, the deep web database at a URL is treated as a black box, to which an input relation is sent and in return an output relation is expected over the schemes and , respectively as part of the syntax above.

The most enabling feature of the extract statement is perhaps its using clause which specifies the set of access tools to be used that hide the details. The wrapper

essentially captures all necessary access details we have discussed in

Section 3.3, including converting returned data by database

d at

into tabular form. However, the schema correspondence necessary between scheme

and with

is established by the mapper

M, and the form filler

F helps construction of the endpoints needed to process each element in the input set. Both BioFlow and SQL play a significant role in QBuild in the construction and execution of user workflow queries.

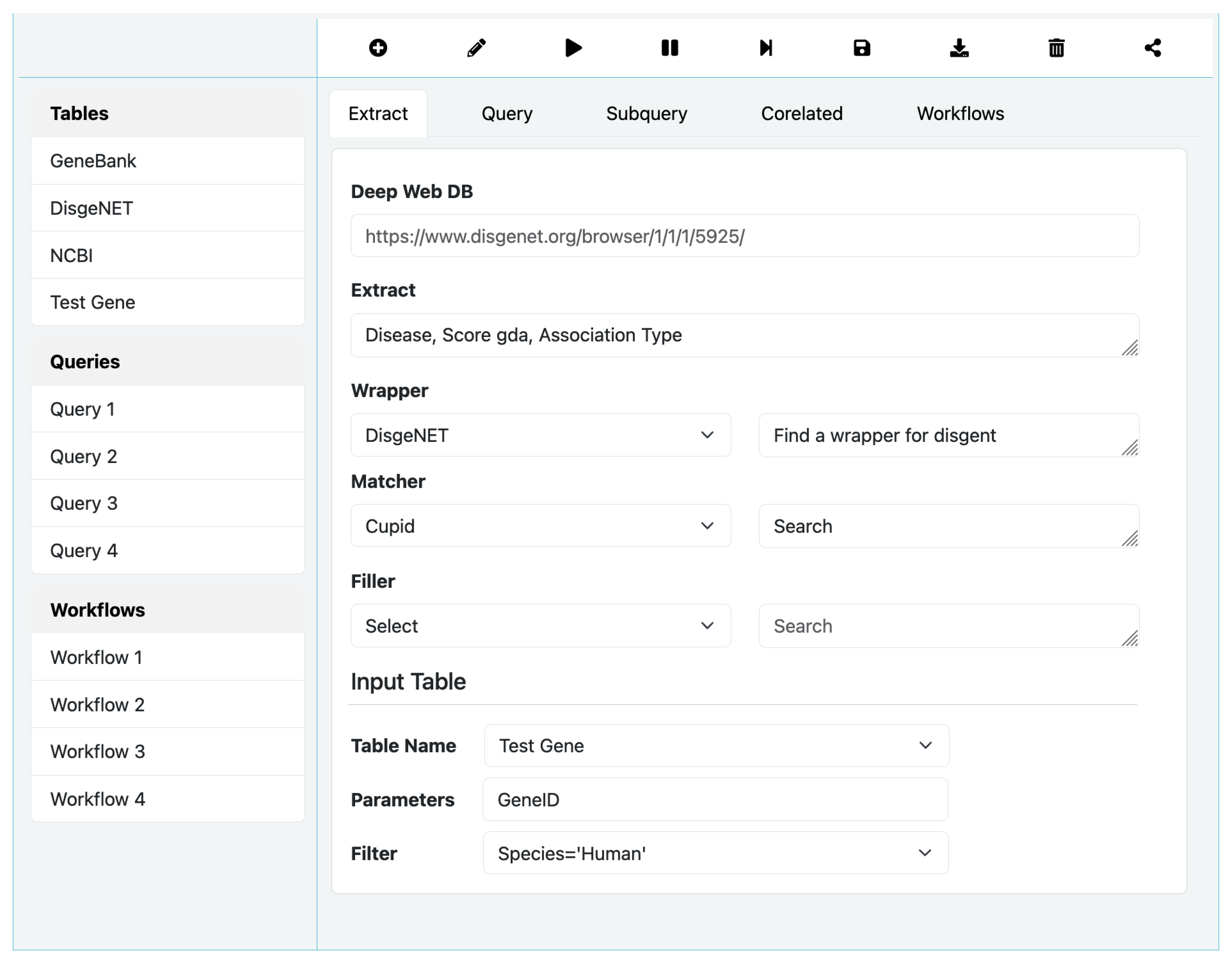

3.4.2. Query Builder Interface

As alluded to earlier, SoDa supports two query constructions – extract statement for deep web data extraction, and select statement for querying tables, and workflow orchestration using a list of these two query types.

Figure 5 shows the main screen of QBuild. We only briefly outline some of its features for the want of space. This interface is rich in features and power compared most contemporary visual SQL query builders, and deserves a more complete discussion which could be found elsewhere.

The top bar above the multi-functional canvas shows function selector radio buttons as icons – Edit, Run, Pause, StepThrough, Save, Retrieve, and Share. When Edit is selected, the three lists Tables, Queries, and Workflows becomes active, and selections Extract, Query, SubQuery, Correlated, and Workflow becomes visible and active as radio buttons. The canvas becomes live and executable using the run button. During execution, the results are shown at the bottom panel, and execution trace is shown at the right panel. When execution stops or paused, the canvas returns to Edit mode.

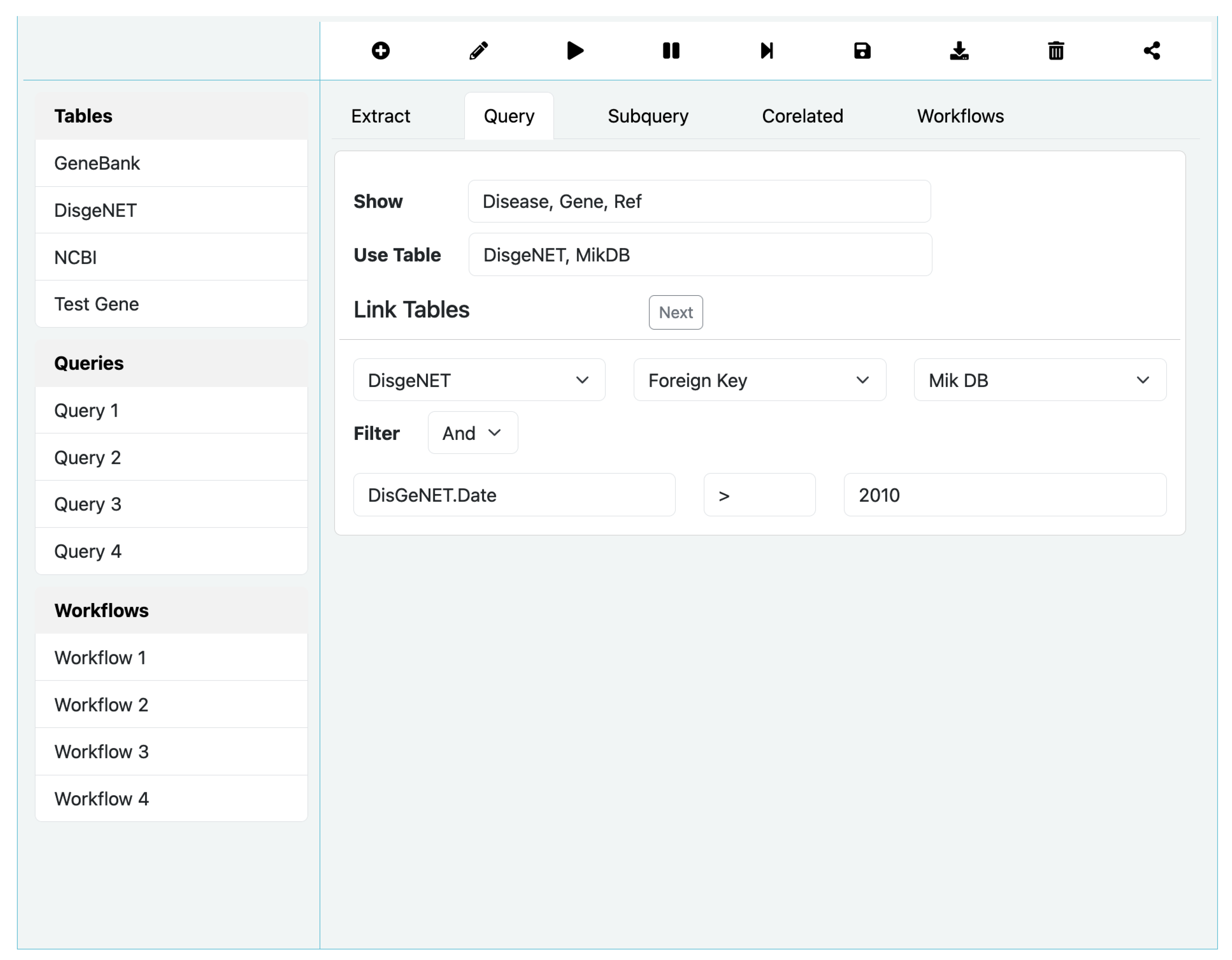

SQL Queries

While writing an Extract query is straightforward with few options, building an SQL query on the other hand is involved and could turn complex. As shown in

Figure 6 for SQL Query option, the process is relatively more complex. In particular, it allows selection of tables from the left bar, and construct complex where clause using the Filter option. The Subquery options allows designating a query to be a subquery of another parent query and correlate it using Correlated option. We omit a full discussion on these options due to space limitation.

3.5. Workflow Query Construction

SoDa supports a workflow orchestration interface similar to VisFlow [

27], but somewhat more water downed ways in terms of features and capabilities. In the case of SoDa, workflows involve a successive set of BioFlow/SQL queries written using the QBuild application builder. Users build a query, likely using multiple resources

3 and save the results in a named view, and reuse the view in a later query. While a view can be stored, a workflow cannot be because SoDa only archives data and not the process that created it or its provenance. The query processor of SoDa is a fusion of QBuild and VisFlow workflow system, and together they form the

SoDaPro system in which VisFlow is accessed through QBuild. The Workflow option in

Figure 6 can be used to sequence named queries already built by dragging them from the left bar under the query tab.

Since queries in SoDaPro potentially involves deep web databases, or online tools, that are accessed at query time, the process may fail for various reasons. The reasons include poor construction of the wrappers, failure of the schema matcher to resolve heterogeneity, resource site evolution or modification, logical errors, or simply network errors. All of the preceding causes are non-database operations which largely depend on software or tool applications with non-deterministic behaviors. But when they breakdown, debugging and fixing could be complicated simply because the clues could be hidden inside many moving parts of a query execution apparatus. One less frustrating way to fix such breakage or query errors is to seek help from more experienced or willing users in the community using crowd computing as discussed in

Section 3.7.

3.6. Workflow Meta-Language

While the BioFlow query language discussed in

Section 3.4.1 serves as the main vehicle for query processing, its automatic construction requires additional engineering of meta-information about the internet resources. These meta-information are generated by the

ResCom sub-system in

Figure 1. It uses the FAIRBridge algorithm discussed in

Section 3.4 to generate two specific meta-information –

process description and

resource description expressed in a language similar to

Needle [

26]. We briefly illustrate the idea how Needle helps generate workflows in BioFlow below.

3.6.1. Process Descriptions

Process description of a resource captures how the resource functions behaviorally, i.e., what is the structure of the table it returns, what it needs to compute a table, how the resource can be accessed. Typically, a workflow consists of a series of resources in which information from one resource move to the next, each computed using an extract statement in BioFlow. To aid in the automatic construction of such a workflow node, we introduced the create process statement along the lines of Needle’s create webtable statements as follows. The statement below helps understand the functionalities of the browser-based access of gene-disease association (GDA) in DisGeNET database and captures the three necessary components, i.e., the process identifier, the resource address and its features, and the input and output table schemes.

% process identifier

create process DisGeNETb

% access protocol

at https://www.disgenet.org/

access browser

postfix /browser/1/1/0/$Genes

% input table scheme

accepts table (

Genes EntrezID) (

% output table scheme

DisGeNETKey EntrezID primary key,

Disease DisID,

Type string,

Disease_class string,

Score_gda decimal (4,2),

…

);

From this statement, we are able to reconstruct the URLs

4 of GDA descriptions for a given gene. The

$ sign in the postfix clause indicates substitutions available in the accepts clause. On the other hand, the process description for API access by genes, is constructed as follows in a similar but distinct way. Depending on the access type we like to adopt, an algorithmic construction of retrieval protocol is now possible from either of these statements.

create process DisGeNETa

access API

postfix /gda/gene/

authorization keyK

accepts table (

Genes EntrezID) (

DisGeNETKey EntrezID primary key,

Disease DisID,

Type string,

Disease_class string,

Score_gda decimal (4,2),

…

);

3.6.2. Resource Descriptions

In contrast to process description, a resource description captures what computational tools are appropriate for a resource to function accurately, and how to determine the reliability of the resource so that its candidacy as a trusted information source can be reasoned. Thus, the primary function of the resource description is to help the ResCom system find, assemble and construct executable workflows as the implementation of an admissible scientific inquiry by selecting the most credible components from its knowledgebase. Recall that most of the resource descriptions in SoDa are contributed by a wide range of community members, some with limited domain expertise or credibility as curators. For example, the resource description for the DisGeNET site can be constructed from its process description to complete the knowledge about this internet resource in the following format using FAIRBridge.

% resource identifier

create resource DisGeNETb (

% resource narrative for machine consumption

narrative “This browser access accepts an Entrez

gene ID and returns its disease association",

% process contributors

contributors {Alex, Abebi},

% applicable data integration tools

meta:

matcher {Cupid, OntoMatch},

wrapper {FastWrap},

mapping {Determination Process: Semantic Type},

% process testers and validators

validators {Alex, Maya},

);

The resource description above links the process description DisGeNETb and additionally captures the essential information required for the construction of a credible workflow. In particular, it helps operation by including the list of effective schema matchers, and wrappers. It also lists term mapping exceptions under mappings clause that must be used and thus overrides any mapping decision by any schema mapping algorithm, e.g., the pair Determination Process: Semantic Type under mapping is one such mapping. One of the meta entries also lists the users who validated the accuracy of this resource description.

Using ResCom, we are now also able to generate process descriptions for the MiKDB [

28] database, and MapBase ID mapping system [

29] as follows.

create process MIKDB

at http://mik.bicnirrh.res.in/mip.php

access browser

postfix /mip.php/

accepts filter (

Phenotype String) (

Symbol GeneSymbol primary key,

ChrLoc string,

Disease string

);

and

create process MapBase

at https://www.mapbase.smartdblab.org

access browser (

Symbol GeneSymbol primary key,

GeneID string

);

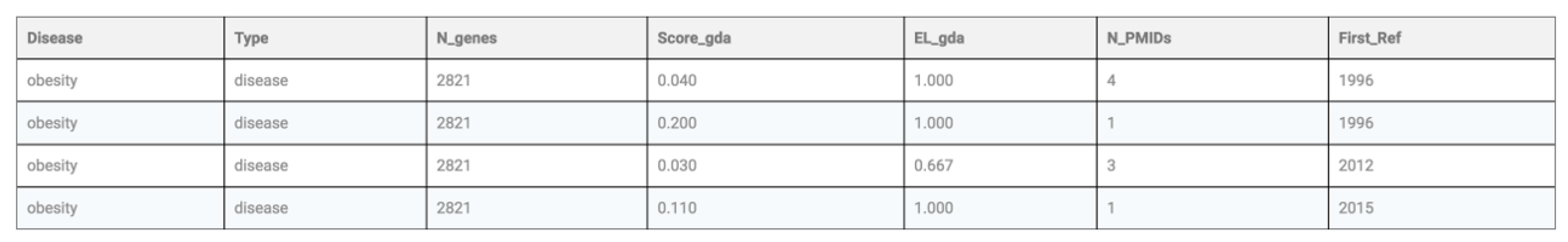

3.6.3. Automated Workflow Construction

To compute the following interesting query

Q: Find all genes implicated in obesity related male infertility using the gene list in the table crrews.

using a set of genes (gene symbols) in a table called

crrews (with scheme

crrews(Symbol), using the MiKDB [

28] and DisGeNET databases, we proceed as follows. We first collect a set of genes (gene symbols) from MiKDB database for a specific phenotype (e.g., teratozoospermia). We then submit those genes (Entrez IDs) to DisGeNET database to find the genes in the set that are also associated with obesity. The technical issue is that MiKDB returns the gene list in the form of Gene Symbols and DisGeNET requires the gene list in the form of Entrez GeneIDs, necessitating and ID conversion step, which we carry out using MapBase. The entire workflow query generated by SoDa is as follows.

select Disease, Type, N_genes, Score_gda, EL_gda, N_PMIDs, First_Ref

from (extract Type, N_genes, Score_gda, EL_gda, N_PMIDs, First_Ref

using matcher S-match wrapper Web-Prospector

from https://www.disgenet.org/browser/1/1/0/

submit (extract GeneID

using matcher S-match wrapper Web-Prospector

from https://www.mapbase.smartdblab.org

submit (with mikgenes as (extract Symbol, Phenotyoe

using matcher S-match wrapper Web-Prospector

from http://mik.bicnirrh.res.in/mip.php

)

select crrews.Symbol

from crrews natural join mikgenes

where Phenotype = "teratozoospermia"

)

)

)

where Disease = ’obesity’ and Score_gda > 0.01;

Execution of this query in SoDa will return the partial table shown in

Figure 7. In the above statement, S-Match [

30] is a schema matcher, and Web-Prospector [

31] is a wrapper. An interesting observation is that SQL’s select statements and BioFlow’s extract statements both uniformly accept each other where a table is expected, and thus allows the nesting as in this query. In the event that the query is needed to be broken down into smaller queries and then strung together, SQL’s create view construct could be used in the usual way.

3.7. Crowd Enabled Curation of Workflows when Pipelines Break

Platforms such as StackOverflow

5 or GitHub

6 have been serving developers with code development projects. LLM based systems such as CoPilot

7 and Amazon Q

8 are offering a more intelligent and faster alternative to the traditional code development and debugging practices. Unfortunately, when the applications, languages and knowledge needed to code and debug are not in the mainstream, such as BioFlow or Needle, such platforms need to be trained with enough data to be of any help. In particular, even a trained LLM will likely need access to the actual resources to be able to offer debugging or even coding assistance [

32,

33].

SoDa’s crowd curation system, called QCurator, takes a more active support approach for error tracing and bug fixing using a crowd computing approach. SoDa users have the option to push a code segment or query to a community discussion board for help. The discussion board has a special notification system which alerts relevant users of an available help request as a ticket. Users may sign up as a participant crowd in the research area or topic of choice. They are able to participate in the discussion to fix problems, fix the errors, execute the code fragments to see if it worked, or opt out, and until they explicitly exit the ticket, it stays active in their notification queue. The ticket is resolved until the user initiated the ticket exits the ticket, or all active participants do so. Note that the ticket is also available for all members of the community in the general discussion board. However, the general discussion board notification goes off only when the initiating user exits the ticket. Finally, the discussion with and solution by the special users are also visible in the general discussion board.

The look and feel of the QCurator discussion board is not much different than the Stack Overflow or GitHub discussion boards, but the difference is more critical when it comes to the notification and debugging approaches. Notifications are owned by the users to whom it is sent specifically, and the notification to the general discussion board is owned by the ticket initiating user. Therefore, all of the owners exit the ticket, it stays active in each of the owners’ dashboards. Finally, every user in the community have access the to discussion board and are able to debug, modify and execute the code fragments on the forum directly from their dashboards.

4. Discussion

Technological limitations play a significant role in the design and functioning of SoDa. Though possible in principle, SoDa’s objective of maintaining a no coding environment makes it difficult to achieve some of its goals fully. We highlight two major issues that SoDa currently are limited in capability to address.

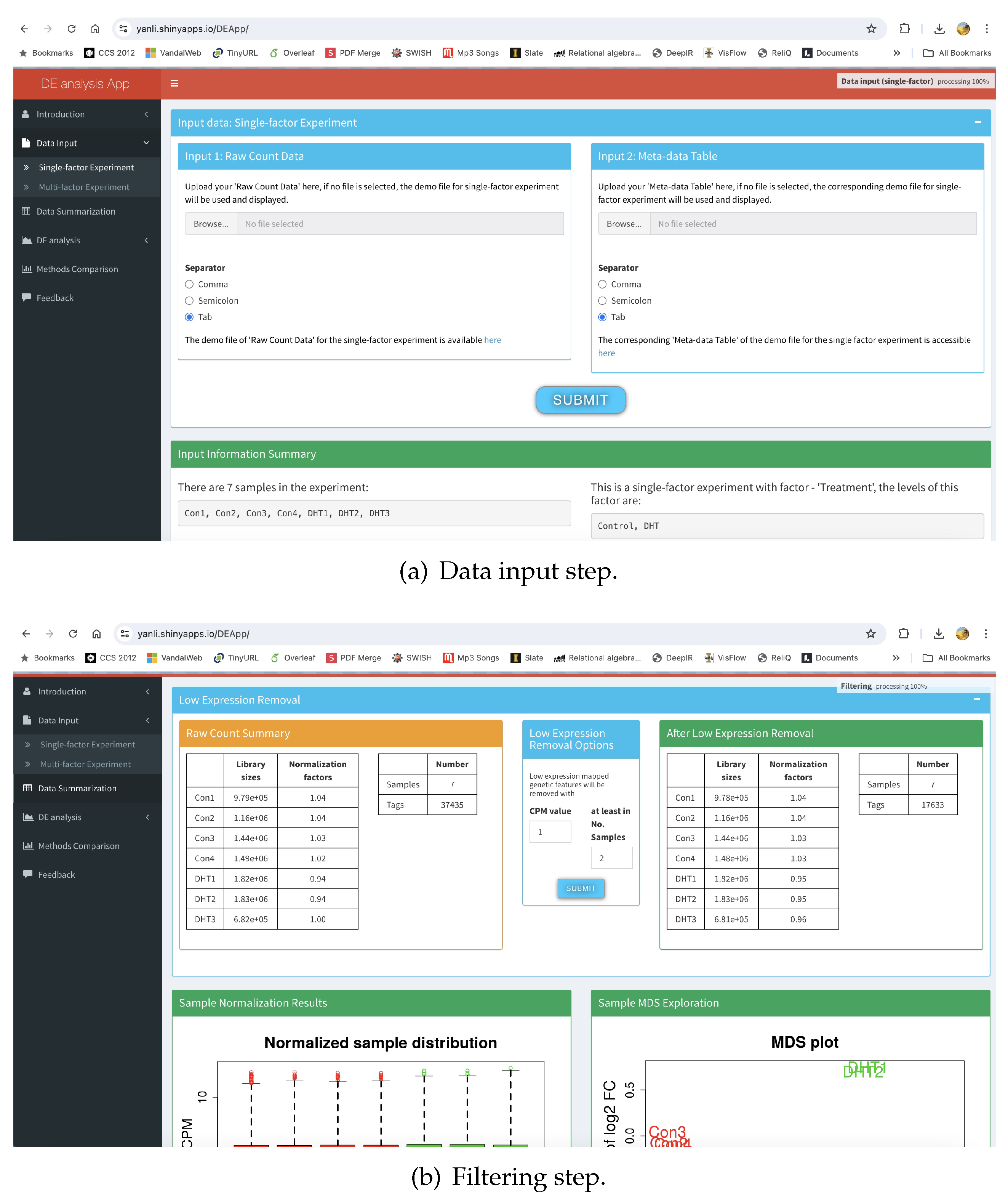

4.1. Complex Wrapper Generation

All internet resource access in SoDa requires an appropriate wrapper from its wrapper bank. As discussed in

Section 3.3, SoDa supports the wrapper generation tool CroW. While complex and innovative wrappers can be constructed using it, CroW currently cannot design wrappers for multi-page forms for a database that uses JavaScript for form design. For example, the online differential expression analyzer DEApp

9 [

34] could be an excellent alternative to expression analyzers DESeq2, edgeR, and Limma available in libraries such as Python or R. However, these libraries are difficult to use in a no code environment. Because even though they are self contained, and relatively easier to identify and codify, or written by CoPilot type coding systems, they still need significant programming experience to incorporate in procedures that can be run on a system such as SoDa.

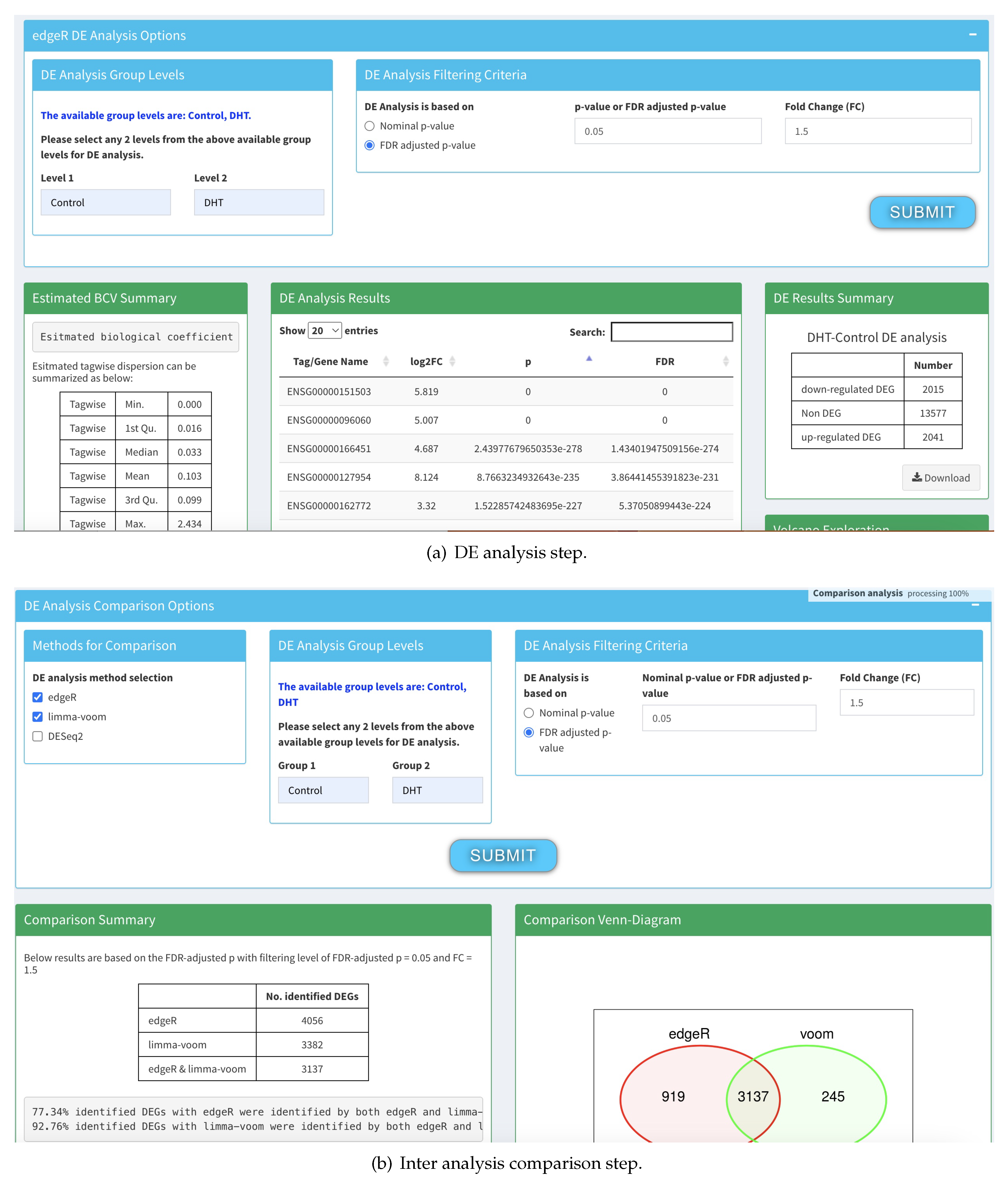

The differential expression analysis in DEApp progresses in four steps – data input (

Figure 8(a)), low expression removal (

Figure 8(b)), DE analysis using libraries such as DESeq2, edgeR, and Limma (

Figure 9(a)), and finally DE analysis comparison (

Figure 9(b)). Though a multi-step process and somewhat complex, the source complication is not how it functions, it is how the interface is designed. In

Figure 8(b), the URL address at the top shows that it did not change from

Figure 8(a), because it si designed using JavaScript that internally changed the form submission parameters it collects from the user. Though CroW is able to design multi-page hopping wrappers, it can do so when the forms are designed using traditional AJAX/JavaScript free technologies. Thus, for now, SoDa only supports inclusion of resources that are either one hop, multi-page designed with AJAX or JavaScript free technologies, or are API based.

4.2. Complex Query Construction

The application design system discussed in

Section 3.4 can be used to design fairly complex BioFlow extract and SQL select queries. The extract statements are regarded as resource access statements and thus are not true querying instruments. Once the resources are accessed and data extracted using extract, they can be queried with the full power of SQL’s select constructs. Typical SQL queries involve sub- and correlated queries, and aggregate functions. While designing query builder GUIs for SQL’s aggregate functions are not too difficult, seamlessly incorporating all these features into the query builder is difficult especially when the users are assumed “naive" and have no true experience in direct complex SQL query writing.

Designing no-code SQL interfaces has a long and winding history [

35,

36]. While there numerous SQL query builders both academic and commercial type, most assume users’ familiarity with complex SQL syntax and semantics, and aims to aid and expedite query building. In particular, they are difficult to use when the query interleaves aggregate functions and correlated subqueries to a too deep level [

37]. Designing a query builder for general public, or biologists, for arbitrary database and intended arbitrary query has its challenges. Recent emergence of LLM based Text2SQL efforts [

38] probably performs better than most no-code interfaces. Our interface too has limitations, but we are currently exploring enhancing our interface with LLM powered SQL query generation by fine tuning an LLM to BioFlow and Needle.

5. Conclusion

The main objective of SoDa is to support biologists to gather data from online resources in a searchable repository so that other biologists could also use the data readily. The search for resources is truly flexible using text analysis of resource needs. As opposed to fully automatic ProAb [

22], SoDa is manual with a human-in-the-loop principle, and offer relatively much lower failure possibilities. The downside is that users must know exactly what they want to compute, but not necessarily how to do it, and thus supports a declarative way of computing internet workflow queries involving heterogeneous resources. The current edition of SoDa is experimental and does not support user data archival for guest users. Future editions of SoDa will support user accounts and allow data archival options along with advanced query building options, likely using LLMs.

Acknowledgments

This Research was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health IDeA grant P20GM103408, a National Science Foundation CSSI grant OAC 2410668, and a US Department of Energy grant DE-0011014.

Notes

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

A database that can only be accessed via query form submission or through an API. |

| 3 |

SoDa treats each of the resources as a table or one that returns a table. |

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

References

- Liu, J.; Lin, L.; Cai, Z.; Wang, J.; Kim, H. Deep web data extraction based on visual information processing. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2024, 15, 1481–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ma, L.; Liu, X. Research on Adaptive Wrapper in Deep Web Data Extraction. IOV 2015, Chengdu, China, December 19-21, 2015. Springer, 2015, Vol. 9502, LNCS, pp. 409–423.

- Bülthoff, F.; Maleshkova, M. RESTful or RESTless - Current State of Today’s Top Web APIs. ESWC 2014, Anissaras, Crete, Greece, May 25-29, 2014; Presutti, V.; Blomqvist, E.; Troncy, R.; Sack, H.; Papadakis, I.; Tordai, A., Eds. Springer, 2014, Vol. 8798, LNCS, pp. 64–74.

- Rodrigues, T.; Benevenuto, F.; Cha, M.; Gummadi, P.K.; Almeida, V.A.F. On word-of-mouth based discovery of the web. ACM SIGCOMM IMC ’11, Berlin, Germany, November 2-, 2011. ACM, 2011, pp. 381–396.

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, E. A New Architecture of an Intelligent Agent-Based Crawler for Domain-Specific Deep Web Databases. WI 2012, Macau, China, December 4-7, 2012. IEEE Computer Society, 2012, pp. 656–663.

- Burks, C. Molecular Biology Database List. Nucleic acids research 1999, 27 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, G.D.; Cary, M.P.; Sander, C. Pathguide: a Pathway Resource List. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; others. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific data 2016, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattyn, F.; Wulbrecht, B.; Knecht, K.; Constandt, H. Assessment of FAIRness of Open Data Sources in Life Sciences. (SWAT4LS 2017), Rome, Italy, December 4-7, 2017. CEUR-WS.org, 2017, Vol. 2042.

- Gaignard, A.; Rosnet, T.; De Lamotte, F.; Lefort, V.; Devignes, M.D. FAIR-Checker: supporting digital resource findability and reuse with Knowledge Graphs and Semantic Web standards. J. Biomedical Semantics 2023, 14, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soiland-Reyes, S.; Goble, C.; Groth, P. Evaluating FAIR Digital Object and Linked Data as distributed object systems. PeerJ Computer Science 2024, 10, e1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wandl-Vogt, E.; Ostojic, D.; Piringer, B.; Rainer, H.; Zsaytseva, K. Designing Collaborative Ecosystems and community organization: Introducing the multidisciplinary portal on "Biodiversity and Linguistic Diversity: A Collaborative Knowledge Discovery Environment". DH 2017, Montréal, Canada, August 8-11, 2017. (ADHO), 2017.

- Antonazzo, G.; Urbano, J.; Marygold, S.J.; Millburn, G.H.; Brown, N.H. Building a pipeline to solicit expert knowledge from the community to aid gene summary curation. Database J. Biol. Databases Curation 2020, 2020, baz152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gendarmi, D.; Abbattista, F.; Lanubile, F. Fostering Knowledge Evolution through Community-based Participation. (CKC 2007)@(WWW2007) Banff, Canada, May 8, 2007. CEUR-WS.org, 2007, Vol. 273.

- Jalili, V.; Afgan, E.; Gu, Q.; Clements, D.; Blankenberg, D.J.; Goecks, J.; Taylor, J.; Nekrutenko, A. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2020 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W395–W402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damkliang, K.; Tandayya, P. Middleware for running and debugging Taverna workflows utilising RESTful web services. Int. J. Simul. Process. Model. 2020, 15, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatu, A.; Paton, N.W.; Douthwaite, M.; Freitas, A. Voyager: Data Discovery and Integration for Onboarding in Data Science. EDBT 2022, Edinburgh, UK, March 29 - April 1, 2022. OpenProceedings.org, 2022, pp. 2:537–2:548.

- Diepenbroek, M. The Application of Semantic Resources and Technologies for the Discovery and Integration of Geo- and Biosciences Data (invited paper). The Bolzano Summer of Knowledge @ FOIS 2021, and ICBO 2021, Bolzano, Italy, September 11-18, 2021. CEUR-WS.org, 2021, Vol. 2969.

- Ouzzani, M.; Tang, N.; Fernandez, R.C. Data civilizer: end-to-end support for data discovery, integration, and cleaning. In Making Databases Work: the Pragmatic Wisdom of Michael Stonebraker; Brodie, M.L., Ed.; ACM / Morgan & Claypool, 2019; Vol. 22, ACM Books, pp. 291–300.

- Pang, C.; Kelpin, F.D.L.; van Enckevort, D.; Eklund, N.; Silander, K.; Hendriksen, D.; de Haan, M.; Jetten, J.; de Boer, T.; Charbon, B.; Holub, P.; Hillege, H.L.; Swertz, M.A. BiobankUniverse: automatic matchmaking between datasets for biobank data discovery and integration. Bioinform. 2017, 33, 3627–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, R.W.; Stöhr, M.R.; Ruppert, C.; Günther, A. Data Discovery for Integration of Heterogeneous Medical Datasets in the German Center for Lung Research (DZL). (GMDS e.V.) 2018 in Osnabrück, Germany, 2-6 September 2018, GMDS 2018. IOS Press, 2018, Vol. 253, pp. 65–69.

- Jamil, H.M. Smart Science Needs Linked Open Data with a Dash of Large Language Models and Extended Relations. aiDM@SIGMOD 2024, Santiago, Chile, 14 June 2024. ACM, 2024, pp. 1:1–1:11.

- Burl, R.B.; Clough, S.; Sendler, E.; Estill, M.; Krawetz, S.A. Sperm RNA elements as markers of health. Systems Biology in Reproductive Medicine 2018, 64, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clough, E.; Barrett, T.; Wilhite, S.E.; Ledoux, P.; Evangelista, C.; Kim, I.F.; Tomashevsky, M.; Marshall, K.A.; Phillippy, K.H.; Sherman, P.M.; Lee, H.; Zhang, N.; Serova, N.; Wagner, L.; Zalunin, V.; Kochergin, A.; Soboleva, A. NCBI GEO: archive for gene expression and epigenomics data sets: 23-year update. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 52, D138–D144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, K.; Shutov, O.; Lapoint, R.; Kimelman, M.; Brister, J.R.; O’Sullivan, C. The Sequence Read Archive: a decade more of explosive growth. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 50, D387–D390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamil, H.; Krawetz, S.A.; Gow, A. Knowledge Synthesis using Large Language Models for a Computational Biology Workflow Ecosystem. SAC 2024, Avila, Spain, April 8-12, 2024. ACM, 2024, pp. 523–530.

- Mou, X.; Jamil, H.M. Visual Life Sciences Workflow Design Using Distributed and Heterogeneous Resources. IEEE/ACM TCBB 2020, 17, 1459–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, S.; Mahale, S.D. Male Infertility Knowledgebase: decoding the genetic and disease landscape. Database 2021, 2021, baab049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, H.M. Improving Integration Effectiveness of ID Mapping Based Biological Record Linkage. IEEE ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2015, 12, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giunchiglia, F.; Autayeu, A.; Pane, J. S-Match: An open source framework for matching lightweight ontologies. Semantic Web 2012, 3, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, S.; Staab, S.; Rojas, I. Web-Prospector - An Automatic, Site-Wide Wrapper Induction Approach for Scientific Deep-Web Databases. BTW, 2009, pp. 87–106.

- Sakib, F.A.; Khan, S.H.; Karim, A.H.M.R. Extending the Frontier of ChatGPT: Code Generation and Debugging. CoRR 2023, abs/2307.08260, [2307.08260]. [CrossRef]

- Saben, C.; Chandrasekar, P. Enabling BLV Developers with LLM-driven Code Debugging. CoRR 2024, abs/2401.16654.

- Li, Y.; Andrade, J. DEApp: an interactive web interface for differential expression analysis of next generation sequence data. Source Code for Biology and Medicine 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedema, D.; Fletcher, G. SQLVis: Visual Query Representations for Supporting SQL Learners. IEEE VL/HCC 2021, St Louis, MO, USA, October 10-13, 2021. IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–9.

- Murakawa, T.; Nakagawa, M. Graphical Expression of SQL Statements Using Clamshell Diagram. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2010, 93-D, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipalus, T. The effects of database complexity on SQL query formulation. J. Syst. Softw. 2020, 165, 110576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hui, B.; Qu, G.; Yang, J.; Li, B.; Li, B.; Wang, B.; Qin, B.; Geng, R.; Huo, N.; Zhou, X.; Ma, C.; Li, G.; Chang, K.C.; Huang, F.; Cheng, R.; Li, Y. Can LLM Already Serve as A Database Interface? A BIg Bench for Large-Scale Database Grounded Text-to-SQLs. NeurIPS 2023, New Orleans, LA, USA, December 10 - 16, 2023, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).