Submitted:

09 October 2024

Posted:

10 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

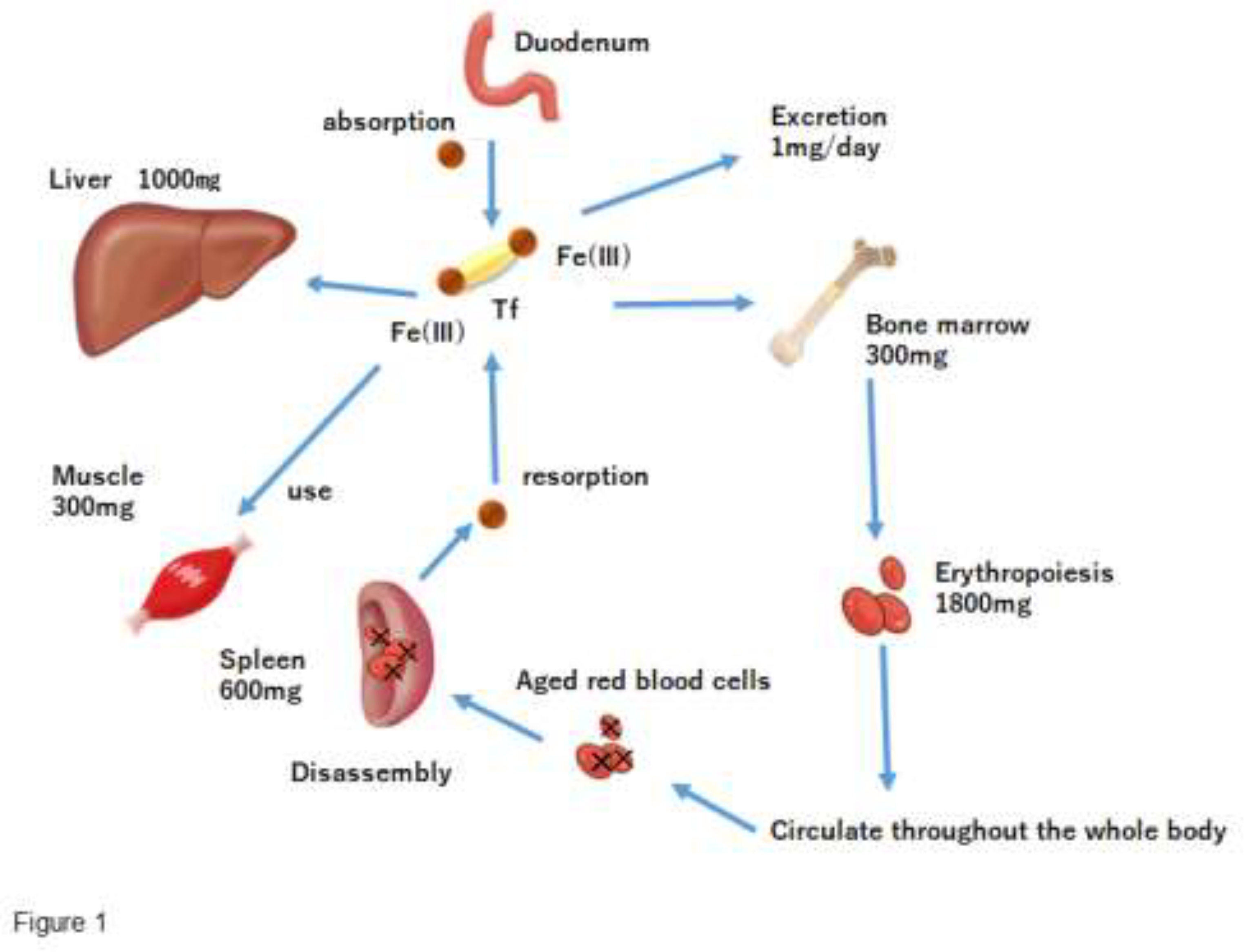

【Iron Distribution in the Body】

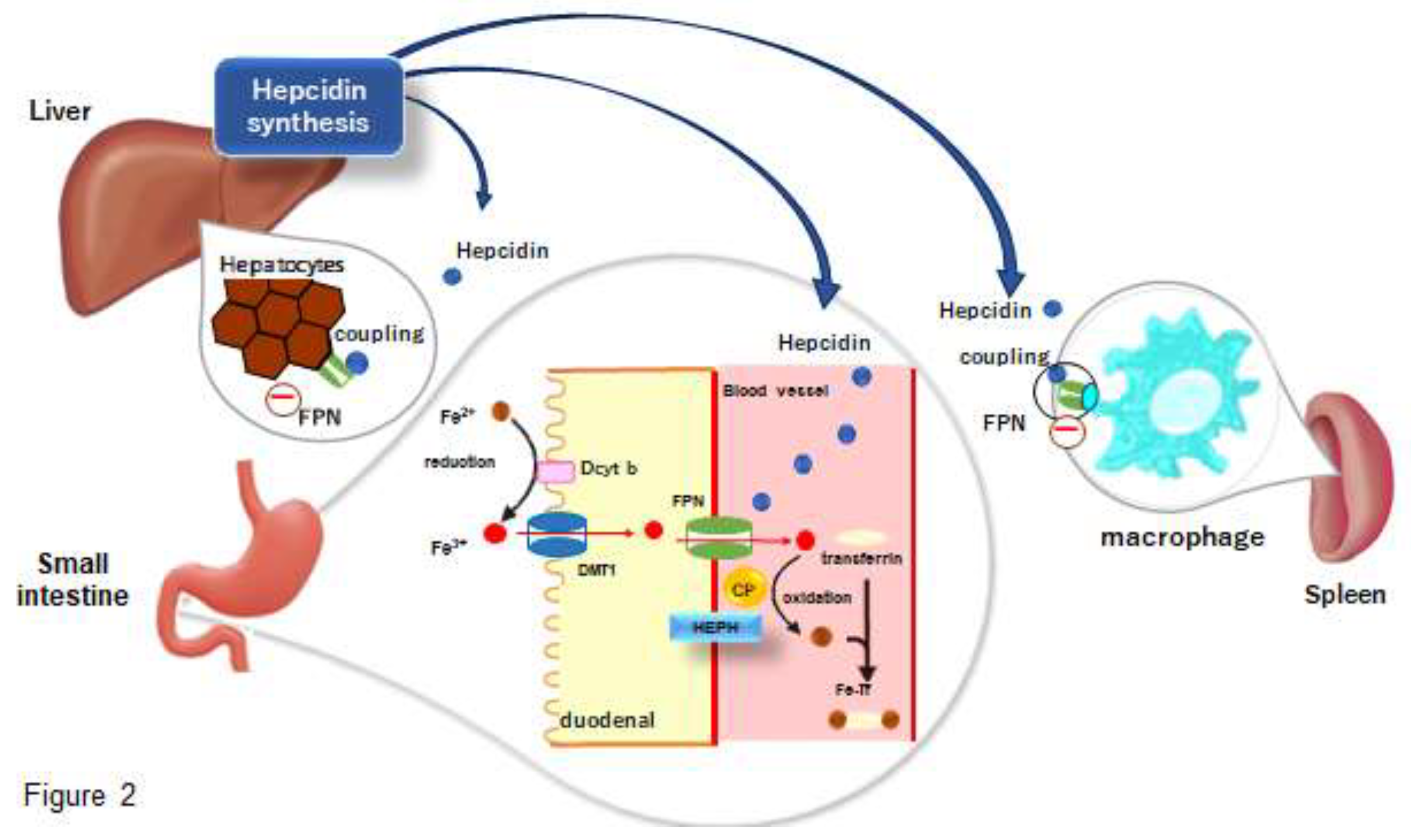

【Iron Deficiency】

【Iron Deficiency in Athletes】

【Exercise and Iron】

【Aerobic Exercise and Iron】

【Resistance Exercise and Iron】

【Nutrition and Exercise】

(1) Diet and Iron

(2) Diet and Nutrients

【Influence of Exercise and Diet Timing on Iron Status in the Body】

【Treatment and Iron】

【Our Latest Developments】

Date Availability Statement

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Muñoz Gómez, M.; Campos Garríguez, A.; García Erce, J.A.; Ramírez Ramírez, G. Fisiopatología del metabolismo del hierro: implicaciones diagnósticas y terapéuticas [Fisiopathology of iron metabolism: diagnostic and therapeutic implications]. Nefrologia : publicacion oficial de la Sociedad Espanola Nefrologia 2005, 25, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andrews, N. C. Disorders of iron metabolism. The New England journal of medicine 1986, 341, 1986–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siah, C.W.; Ombiga, J.; Adams, L.A.; Trinder, D.; Olynyk, J.K. Normal iron metabolism and the pathophysiology of iron overload disorders. The Clinical biochemist. Reviews 2006, 27, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, R.E.; Bacon, B.R. Orchestration of iron homeostasis. The New England journal of medicine 2005, 352, 1741–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, T. Hepcidin, a key regulator of iron metabolism and mediator of anemia of inflammation. Blood 2003, 102, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.L.; Beutler, E. Regulation of hepcidin and iron-overload disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol 2009, 4, 489–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peslova, G.; Petrak, J.; Kuzelova, K.; Hrdy, I.; Halada, P.; Kuchel, P.W.; Soe-Lin, S.; Ponka, P.; Sutak, R.; Becker, E.; et al. Hepcidin, the hormone of iron metabolism, is bound specifically to alpha-2-macroglobulin in blood. Blood 2009, 113, 6225–6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, G.; Bennoun, M.; Devaux, I.; Beaumont, C.; Grandchamp, B.; Kahn, A.; Vaulont, S. Lack of hepcidin gene expression and severe tissue iron overload in upstream stimulatory factor 2 (USF2) knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 8780–8785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunshin, H.; Mackenzie, B.; Berger, U.V.; Gunshin, Y.; Romero, M.F.; Boron, W.F.; Nussberger, S.; Gollan, J.L.; Hediger, M.A. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature 1997, 388, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentze, M.W.; Muckenthaler, M.U.; Galy, B.; Camaschella, C. Two to tango: Regulation of Mammalian iron metabolism. Cell 2010, 142, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayeghi, M.; Latunde-Dada, G.O.; Oakhill, J.S.; Laftah, A.H.; Takeuchi, K.; Halliday, N.; Khan, Y.; Warley, A.; McCann, F.E.; Hider, R.C.; et al. Identification of an intestinal heme transporter. Cell 2005, 122, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffin, S.B.; Woo, C.H.; Roost, K.T.; Price, D.C.; Schmid, R. Intestinal absorption of hemoglobin iron-heme cleavage by mucosal heme oxygenase. J. Clin. Investig. 1974, 54, 1344–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abboud, S.; Haile, D.J. A novel mammalian iron-regulated protein involved in intracellular iron metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 19906–19912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, A.; Brownlie, A.; Zhou, Y.; Shepard, J.; Pratt, S.J.; Moynihan, J.; Paw, B.H.; Drejer, A.; Barut, B.; Zapata, A.; et al. Positional cloning of zebrafish ferroportin1 identifies a conserved vertebrate iron exporter. Nature 2000, 403, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKie, A.T.; Marciani, P.; Rolfs, A.; Brennan, K.; Wehr, K.; Barrow, D.; Miret, S.; Bomford, A.; Peters, T.J.; Farzaneh, F.; et al. A novel duodenal iron-regulated transporter, IREG1, implicated in the basolateral transfer of iron to the circulation. Mol. Cell 2000, 5, 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- Vulpe, C.D.; Kuo, Y.M.; Murphy, T.L.; Cowley, L.; Askwith, C.; Libina, N.; Gitschier, J.; Anderson, G.J. Hephaestin, a ceruloplasmin homologue implicated in intestinal iron transport, is defective in the sla mouse. Nat. Genet. 1999, 21, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Z.L.; Durley, A.P.; Man, T.K.; Gitlin, J.D. Targeted gene disruption reveals an essential role for ceruloplasmin in cellular iron efflux. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 10812–10817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisen PTransferrin receptor 1. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2004, 36, 2137–2143.

- Fujii T, Kobayashi K, Kaneko M, Osana S, Tsai CT, Ito S, Hata. RGM Family Involved in the Regulation of Hepcidin Expression in Anemia of Chronic Disease. Immuno 2024, 4, 266–285.

- Kawabata, H.; Yang, R.; Hirama, T.; et al. Molecular cloning of transferrin receptor 2. A new member of the transferrin receptor-like family. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 20826–20832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikuta, K.; Zak, O.; Aisen, P. Recycling, degradation and sensitivity to the synergistic anion of transferrin in the receptor-independent route of iron uptake by human hepatoma (HuH-7) cells. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2004, 36, 340–352. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, N. C. Forging a field: the golden age of iron biology. Blood 2008, 112, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, R.E.; Sly, W.S. Hepcidin: a putative iron-regulatory hormone relevant to hereditary hemochromatosis and the anemia of chronic disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2001, 98, 8160–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO 2019. Prevalence of anaemia in women of reproductive age (aged 15–49) (%). Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/prevalence-of-anaemia-in-women-of-reproductive-age-(-).

- Cappellini, M.D.; Musallam, K.M.; Taher, A.T. Iron deficiency anaemia revisited. Journal of internal medicine 2020, 287, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.T.; Manz, D.H.; Torti, F.M.; Torti, S.V. Mitochondria and Iron: current questions. Expert review of hematology 2017, 10, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallman, P. R. Manifestations of iron deficiency. Seminars in hematology 1982, 19, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dallman, P. R. Biochemical basis for the manifestations of iron deficiency. Annual review of nutrition 1986, 6, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scrimshaw, N. S. Functional consequences of iron deficiency in human populations. Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology 1984, 30, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.D.; Lynch, S.R. The liabilities of iron deficiency. Blood 1986, 68, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.; Tobin, B. Iron status and exercise. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2000, 72(2 Suppl), 594S–7S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukaski, H.C. Vitamin and mineral status: effects on physical performance. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.) 2004, 20, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celsing, F.; Ekblom, B. Anemia causes a relative decrease in blood lactate concentration during exercise. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology 1986, 55, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.D.; Brownlie, T. 4th Iron deficiency and reduced work capacity: a critical review of the research to determine a causal relationship. The Journal of nutrition 2001, 131, 676S–690S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, J.G.; Ahlquist, D.A.; McGill, D.B.; Ilstrup, D.M.; Schwartz, S.; Owen, R.A. Gastrointestinal blood loss and anemia in runners. Annals of internal medicine 1984, 100, 843–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.J.; Pate, R.R.; Burgess, W. Foot impact force and intravascular hemolysis during distance running. International journal of sports medicine 1988, 9, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, N.; Fridlund, K.E.; Askew, E.W. Nutrition issues of military women. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 1993, 12, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, M.; Magnusson, B.; Persson, H.; Hallberg, L. Iron losses in sweat. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1986, 43, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Tuttle, M.S.; Powelson, J.; Vaughn, M.B.; Donovan, A.; Ward, D.M.; Ganz, T.; Kaplan, J. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2004, 306, 2090–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin-Ferroportin Interaction Controls Systemic Iron Homeostasis. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, T.; Konomi, A.; Yokoi, K. Iron deficiency without anemia is associated with anger and fatigue in young Japanese women. Biological trace element research 2014, 159, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, M.; Garvican-Lewis, L.A.; Cox, G.R.; Govus, A.; McKay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Peeling, P. Iron considerations for the athlete: a narrative review. European journal of applied physiology 2019, 119, 1463–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recalcati, S.; Minotti, G.; Cairo, G. Iron regulatory proteins: from molecular mechanisms to drug development. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2010, 13, 1593–1616. [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth, E.; Valore, E.V.; Territo, M.; Schiller, G.; Lichtenstein, A.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin, a putative mediator of anemia of inflammation, is a type II acute-phase protein. Blood 2003, 101, 2461–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banzet, S.; Sanchez, H.; Chapot, R.; Bigard, X.; Vaulont, S.; Koulmann, N. Interleukin-6 contributes to hepcidin mRNA increase in response to exercise. Cytokine 2012, 58, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, G.; Goodnough, L.T. Anemia of chronic disease. The New England journal of medicine 2005, 352, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeling, P.; Dawson, B.; Goodman, C.; Landers, G.; Wiegerinck, E.T.; Swinkels, D.W.; Trinder, D. Cumulative effects of consecutive running sessions on hemolysis, inflammation and hepcidin activity. European journal of applied physiology 2009, 106, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeling, P.; Dawson, B.; Goodman, C.; Landers, G.; Wiegerinck, E.T.; Swinkels, D.W.; Trinder, D. Training surface and intensity: inflammation, hemolysis, and hepcidin expression. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 2009, 41, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newlin, M.K.; Williams, S.; McNamara, T.; Tjalsma, H.; Swinkels, D.W.; Haymes, E.M. The effects of acute exercise bouts on hepcidin in women. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism 2012, 22, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronsen, O.; Lea, T.; Bahr, R.; Pedersen, B.K. Enhanced plasma IL-6 and IL-1ra responses to repeated vs. single bouts of prolonged cycling in elite athletes. Journal of applied physiology (ethesda, Md. : 1985) 2002, 92, 2547–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banzet, S.; Sanchez, H.; Chapot, R.; Bigard, X.; Vaulont, S.; Koulmann, N. Interleukin-6 contributes to hepcidin mRNA increase in response to exercise. Cytokine 2012, 58, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means R: The anemia of chronic disorders. Wintrobe’s Clinical Hematology. Lee R et al, eds Williams & Willkins 1999, 1011-1021.

- Andrews, N. C. Anemia of inflammation: the cytokine-hepcidin link. The Journal of clinical investigation 2004, 113, 1251–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, A.J.; Hennekens, C.H.; Solomon, H.S.; Van Boeckel, B. Exercise-related hematuria. Findings in a group of marathon runners. JAMA 1979, 241, 391–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, J.G.; Ahlquist, D.A.; McGill, D.B.; Ilstrup, D.M.; Schwartz, S.; Owen, R.A. Gastrointestinal blood loss and anemia in runners. Annals of internal medicine 1984, 100, 843–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, M.; Magnusson, B.; Persson, H.; Hallberg, L. Iron losses in sweat. The American journal of clinical nutrition 1986, 43, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehn, L.; Carlmark, B.; Höglund, S. Iron status in athletes involved in intense physical activity. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 1980, 12, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, B.W.; Beard, J.L. Interactions of iron deficiency and exercise training in male Sprague-Dawley rats: ferrokinetics and hematology. The Journal of nutrition 1989, 119, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radomski, M.W.; Sabiston, B.H.; Isoard, P. Development of „sports anemia” in physically fit men after daily sustained submaximal exercise. Aviation, space, and environmental medicine 1980, 51, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas, G.; Chauvet, C.; Viatte, L.; Danan, J.L.; Bigard, X.; Devaux, I.; Beaumont, C.; Kahn, A.; Vaulont, S. The gene encoding the iron regulatory peptide hepcidin is regulated by anemia, hypoxia, and inflammation. The Journal of clinical investigation 2002, 110, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkkiö, M.V.; Jansson, L.T.; Henderson, S.; Refino, C.; Brooks, G.A.; Dallman, P.R. Work performance in the iron-deficient rat: improved endurance with exercise training. The American journal of physiology 1985, 249(3 Pt 1), E306–E311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, W.T.; Brooks, G.A.; Henderson, S.A.; Dallman, P.R. Effects of iron deficiency and training on mitochondrial enzymes in skeletal muscle. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985) 1987, 62, 2442–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagne, C.M.; Walberg-Rankin, J.L.; Ritchey, S.J. Effects of exercise on iron status in mature female rats. Nutr, Res 2014, 14, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming Qian, Z.; Sheng Xiao, D.; Kui Liao, Q.; Ping Ho, K. (2002). Effect of different durations of exercise on transferrin-bound iron uptake by rat erythroblast. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry 2002, 13, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strause, L.; Hegenauer, J.; Saltman, P. Effects of exercise on iron metabolism in rats. Nutr Res 1983, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckman, K.S.; Sherman, A.R. Effects of exercise on iron and copper metabolism in rats. The Journal of nutrition 1981, 111, 1593–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachtigall, D.; Nielsen, P.; Fischer, R.; Engelhardt, R.; Gabbe, E.E. Iron deficiency in distance runners. A reinvestigation using Fe-labelling and non-invasive liver iron quantification. International journal of sports medicine 1996, 17, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, S.; Taylor, W.R.; Duda, G.N.; von Haehling, S.; Reinke, P.; Volk, H.D.; Anker, S.D.; Doehner, W. Absolute and functional iron deficiency in professional athletes during training and recovery. International journal of cardiology 2012, 156, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, P. S. Iron and the endurance athlete. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme 2014, 39, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwabara, A.M.; Tenforde, A.S.; Finnoff, J.T.; Fredericson, M. Iron deficiency in athletes: A narrative review. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation 2022, 14, 620–642. [Google Scholar]

- Galetti, V.; Stoffel, N.U.; Sieber, C.; Zeder, C.; Moretti, D.; Zimmermann, M.B. Threshold ferritin and hepcidin concentrations indicating early iron deficiency in young women based on upregulation of iron absorption. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 39, 101052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Zourdos, M.C.; Calleja-González, J.; Córdova, A.; Fernandez-Lázaro, D.; Caballero-García, A. Eleven Weeks of Iron Supplementation Does Not Maintain Iron Status for an Entire Competitive Season in Elite Female Volleyball Players: A Follow-Up Study. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.C.; Mack, G.W.; Wolfe, R.R.; Nadel, E.R. Albumin synthesis after intense intermittent exercise in human subjects. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985) 1998, 84, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamura, K.; Doi, T.; Hamada, K.; Sakurai, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Imaizumi, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Shimizu, S.; Suzuki, M. Effect of amino acid and glucose administration during postexercise recovery on protein kinetics in dogs. The American journal of physiology 1997, 272(6 Pt 1), E1023–E1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmarck, B.; Andersen, J.L.; Olsen, S.; Richter, E.A.; Mizuno, M.; Kjaer, M. Timing of postexercise protein intake is important for muscle hypertrophy with resistance training in elderly humans. The Journal of physiology 2001, 535 (Pt 1), 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenhagen, D.K.; Gresham, J.D.; Carlson, M.G.; Maron, D.J.; Borel, M.J.; Flakoll, P.J. Postexercise nutrient intake timing in humans is critical to recovery of leg glucose and protein homeostasis. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism 2001, 280, E982–E993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, T.; Suzuki, H.; Suzuki, M. Resistance Exercise Increases the Capacity of Heme Biosynthesis More Than Aerobic Exercise in Rats. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2000, 29, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T.; Suzuki, H.; Suzuki, M. Dubbell exercise improves non-anemic iron deficiency in young women without iron supplementation. Health Sci 2000, 16, 236–243. [Google Scholar]

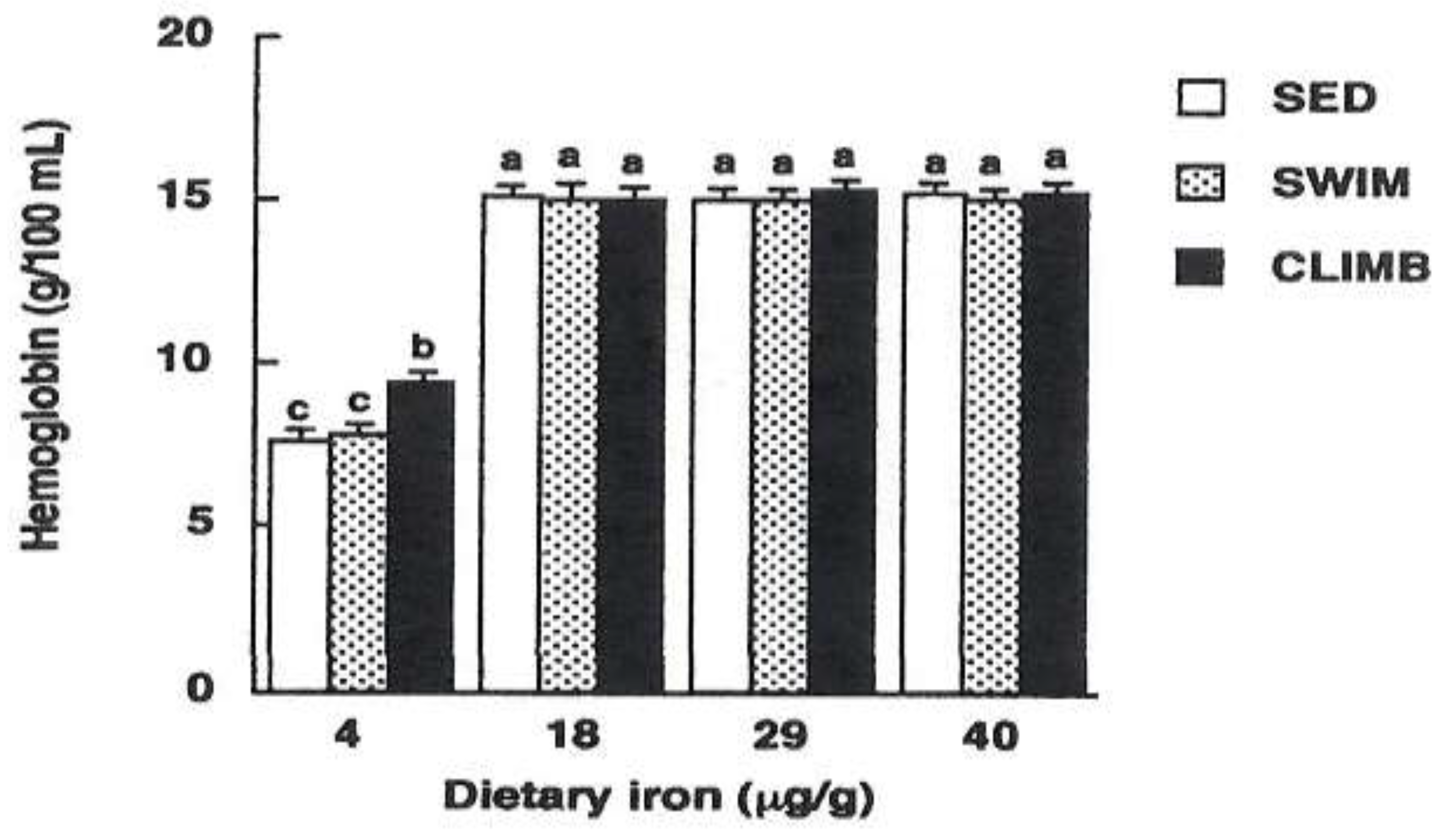

- Matsuo, T.; Kang, H.S.; Suzuki, H.; Suzuki, M. Voluntary resistance exercise improves blood hemoglobin concentration in severely iron-deficient rats. Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology 2002, 48, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T. Effects of resistance exercise on iron metabolism in iron-adequate or iron-deficient rats. The Korean Joumal of Exercise Nutrition 2004, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, T.; Matsuo, T.; Okamura, K. Effects of resistance exercise on iron absorption and balance in iron-deficient rats. Biological trace element research 2014, 161, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T.; Asai, T.; Matsuo, T.; Okamura, K. Effect of resistance exercise on iron status in moderately iron-deficient rats. Biological trace element research 2011, 144, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

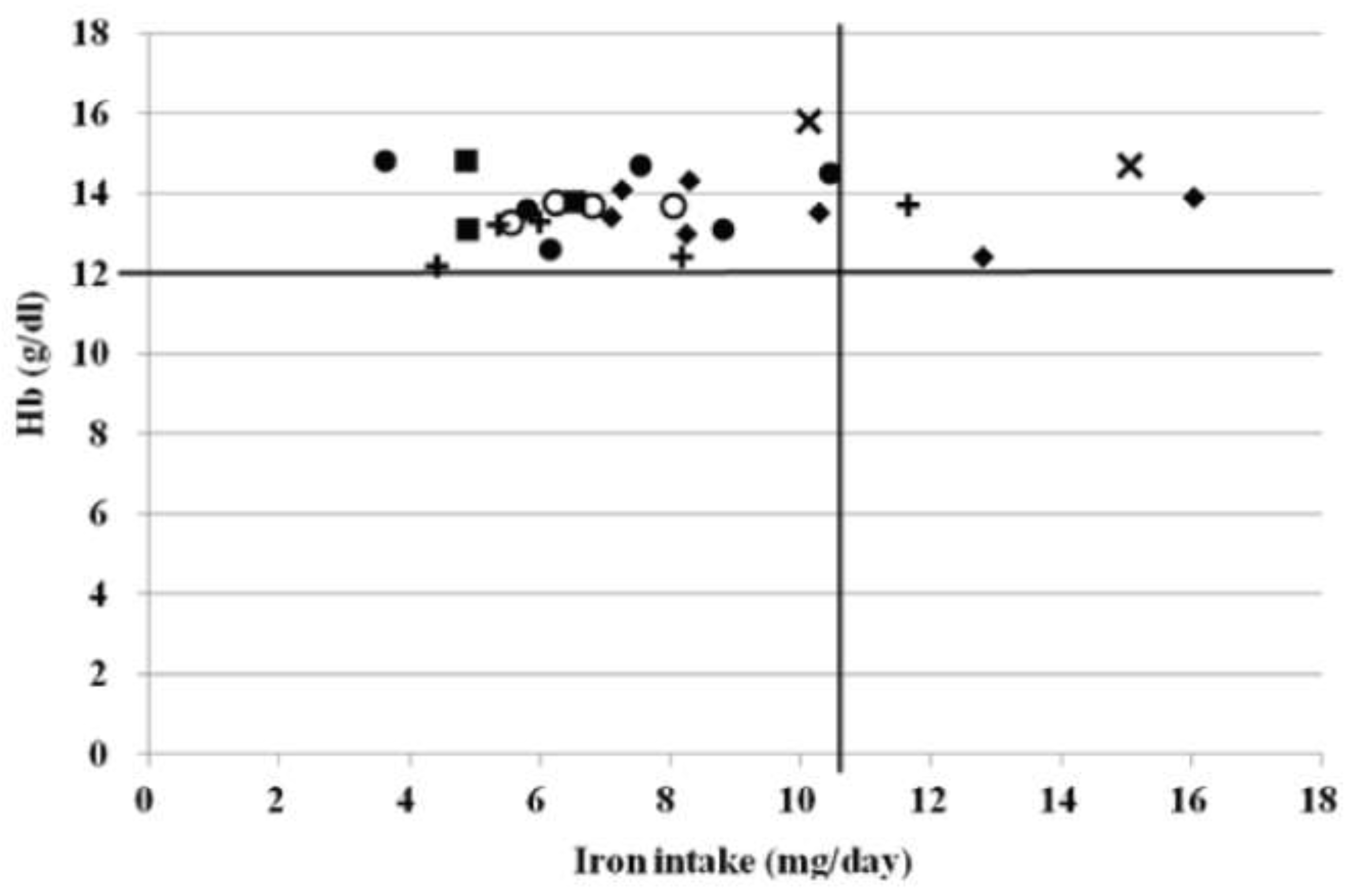

- Fujii, T.; Okumura, Y.; Maeshima, E.; Okamura, K. Dietary Iron Intake and Hemoglobin Concentration in College Athletes in Different Sports. Int J Sports Exerc Med 2015, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, M.; Ishikawa, T.K.; Tatsuta, W.; Katsuragi, C.; et al. Resting energy expenditure can be assessed by fat-free mass in female athletes regardless of body size. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyle, R.M.; Weaver, C.M.; Sedlock, D.A.; Rajaram, S.; Martin, B.; Melby, C.L. Iron status in exercising women: the effect of oral iron therapy vs increased consumption of muscle foods. The American journal of clinical nutrition 1992, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetens, I.; Bendtsen, K.M.; Henriksen, M.; Ersbøll, A.K.; Milman, N. The impact of a meat- versus a vegetable-based diet on iron status in women of childbearing age with small iron stores. European journal of nutrition 2007, 46, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, S.; Taylor, W.R.; Duda, G.N.; von Haehling, S.; Reinke, P.; Volk, H.D.; Anker, S.D.; Doehner, W. Absolute and functional iron deficiency in professional athletes during training and recovery. International journal of cardiology 2012, 156, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clenin, G.; Cordes, M.; Huber, A.; Schumacher, Y.O.; Noack, P.; Scales, J.; Kriemler, S. Iron deficiency in sports—Definition, influence on performance and therapy. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2015, 145, w14196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, R.; Sanchez-Oliver, A.J.; Mata-Ordonez, F.; Feria-Madueno, A.; Grimaldi-Puyana, M.; Lopez-Samanes, A.; Perez-Lopez, A. Effects of an Acute Exercise Bout on Serum Hepcidin Levels. Nutrients 2018, 10, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ems, T.; St Lucia, K.; Huecker, M.R. Biochemistry, Iron Absorption. In StatPearls; Ineligible Companies: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Deldicque, L.; Francaux, M. Recommendations for Healthy Nutrition in Female Endurance Runners: An Update. Frontiers in nutrition 2015, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.K.A.; Pyne, D.B.; Burke, L.M.; Peeling, P. Iron Metabolism: Interactions with Energy and Carbohydrate Availability. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, N.; Ishibashi, A.; Iwata, A.; Yatsutani, H.; Badenhorst, C.; Goto, K. Influence of an energy deficient and low carbohydrate acute dietary manipulation on iron regulation in young females. Physiol. Rep. 2022, 10, e15351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, L. M. Ketogenic low-CHO, high-fat diet: the future of elite endurance sport? The Journal of physiology 2021, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steensberg, A.; Febbraio, M.A.; Osada, T.; Schjerling, P.; van Hall, G.; Saltin, B.; Pedersen, B.K. Interleukin-6 production in contracting human skeletal muscle is influenced by pre-exercise muscle glycogen content. J. Physiol 2001, 537, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badenhorst, C.E.; Black, K.E.; O’Brien, W.J. Hepcidin as a Prospective Individualized Biomarker for Individuals at Risk of Low Energy Availability. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism 2019, 29, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badenhorst, C.E.; Dawson, B.; Cox, G.R.; Laarakkers, C.M.; Swinkels, D.W.; Peeling, P. Acute dietary carbohydrate manipulation and the subsequent inflammatory and hepcidin responses to exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 115, 2521–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, S.A.; Dallman, P.R.; Brooks, G.A. Glucose turnover and oxidation are increased in the iron-deficient anemic rat. The American journal of physiology 1986, 250(4 Pt 1), E414–E421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, A.; Kojima, C.; Tanabe, Y.; Iwayama, K.; Hiroyama, T.; Tsuji, T.; Kamei, A.; Goto, K.; Takahashi, H. Effect of low energy availability during three consecutive days of endurance training on iron metabolism in male long distance runners. Physiol. Rep. 2020, 8, e14494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statuta, S.M.; Asif, I.M.; Drezner, J.A. Relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). British journal of sports medicine 2017, 51, 1570–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, A. B. Low energy availability in the marathon and other endurance sports. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 2007, 37, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkus, D.L.; Murray-Kolb, L.E.; De Souza, M.J. The Unexplored Crossroads of the Female Athlete Triad and Iron Deficiency: A Narrative Review. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 2017, 47, 1721–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papillard-Marechal, S.; Sznajder, M.; Hurtado-Nedelec, M.; Alibay, Y.; Martin-Schmitt, C.; Dehoux, M.; Westerman, M.; Beaumont, C.; Chevallier, B.; Puy, H.; et al. Iron metabolism in patients with anorexia nervosa: elevated serum hepcidin concentrations in the absence of inflammation. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2012, 95, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, M.L.; Burke, L.M.; Stellingwerff, T.; Sundgot-Borgen, J. Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport: The Tip of an Iceberg. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism 2018, 28, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennigar, S.R.; McClung, J.P.; Hatch-McChesney, A.; Allen, J.T.; Wilson, M.A.; Carrigan, C.T.; Murphy, N.E.; Teien, H.K.; Martini, S.; Gwin, J.A.; et al. Energy deficit increases hepcidin and exacerbates declines in dietary iron absorption following strenuous physical activity: a randomized-controlled cross-over trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2021, 113, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barney, D.E.; Ippolito, J.R.; Berryman, C.E.; Hennigar, S.R. A Prolonged Bout of Running Increases Hepcidin and Decreases Dietary Iron Absorption in Trained Female and Male Runners. The Journal of nutrition 2022, 152, 2039–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.C.; Anson, J.M.; Dziedzic, C.E.; Mcdonald, W.A.; Pyne, D.B. Iron monitoring of male and female rugby seven players over an international season. The Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness 2018, 58, 1490–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T.; Matsuo, T.; Okamura, K. The effects of resistance exercise and post-exercise meal timing on the iron status in iron-deficient rats. Biological trace element research 2012, 147, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, R.; Moretti, D.; McKay, A.K.A.; Laarakkers, C.M.; Vanswelm, R.; Trinder, D.; Cox, G.R.; Zimmerman, M.B.; Sim, M.; Goodman, C.; et al. The Impact of Morning versus Afternoon Exercise on Iron Absorption in Athletes. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 2019, 51, 2147–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigham, D.E.; Beard, J.L.; Krimmel, R.S.; Kenney, W.L. Changes in iron status during competitive season in female collegiate swimmers. Nutrition 1993, 9, 418–422. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, P. S. Iron and the endurance athlete. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme 2014, 39, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S.; Matsuo, T. Effects of 4 weeks iron supplementation on haematological and immunological status in elite female soccer players. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition 2004, 13, 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz, A.; Lubas, A.; Fiedor, P.; Fiedor, M.; Niemczyk, S. AFETY AND EFFICACY OF INTRAVENOUS ADMINISTRATION OF IRON PREPARATIONS. Acta poloniae pharmaceutica 2017, 74, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Low, M.S.; Speedy, J.; Styles, C.E.; De-Regil, L.M.; Pasricha, S.R. Daily iron supplementation for improving anaemia, iron status and health in menstruating women. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2016, 4, CD009747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallon, K.E. Utility of hematological and iron-related screening in elite athletes. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2004, 14, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, M.; Garvican-Lewis, L.A.; Cox, G.R.; Govus, A.; McKay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Peeling, P. Iron considerations for the athlete: A narrative review. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 119, 1463–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenberg, R.E.; Gustafson, S. Iron as an ergogenic aid: Ironclad evidence? Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2007, 6, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, A.; Reikvam, H. Iron Status and Physical Performance in Athletes. Life (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 13, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvican-Lewis, L.A.; Vuong, V.L.; Govus, A.D.; Peeling, P.; Jung, G.; Nemeth, E.; Hughes, D.; Lovell, G.; Eichner, D.; Gore, C.J. Intravenous Iron Does Not Augment the Hemoglobin Mass Response to Simulated Hypoxia. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc 2018, 50, 1669–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrisch, J.R.; Cancado, R.D. Intravenous ferric carboxymaltose for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia. Rev. Bras. Hematol. Hemoter 2015, 37, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girelli, D.; Ugolini, S.; Busti, F.; Marchi, G.; Castagna, A. Modern iron replacement therapy: Clinical and pathophysiological insights. Int. J. Hematol 2018, 107, 16–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraenkel, P.G. Understanding anemia of chronic disease. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Progra. 2015, 2015, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Babitt, J.L. Hepcidin regulation in the anemia of inflammation. Curr. Opin. Hematol 2016, 23, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, A.; Nai, A.; Silvestri, L.; Camaschella, C. Hepcidin and Anemia: A Tight Relationship. Front. Physiol 2019, 10, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babitt, J.L.; Huang, F.W.; Wrighting, D.M.; Xia, Y.; Sidis, Y.; Samad, T.A.; Campagna, J.A.; Chung, R.T.; Schneyer, A.L.; Woolf, C.J.; et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling by hemojuvelin regulates hepcidin expression. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corradini, E.; Babitt, J.L.; Lin, H.Y. The RGM/DRAGON family of BMP co-receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2009, 20, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulos, B., Jr.; Corradini, E.; Xia, Y.; Faasse, S.A.; Chen, S.; Grgurevic, L.; Knutson, M.D.; Pietrangelo, A.; Vukicevic, S.; Lin, H.Y.; et al. BMP6 is a key endogenous regulator of hepcidin expression and iron metabolism. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meynard, D.; Kautz, L.; Darnaud, V.; Canonne-Hergaux, F.; Coppin, H.; Roth, M.P. Lack of the bone morphogenetic protein BMP6 induces massive iron overload. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, P.P.; Sierra, A.; Macchi, P.; Deitinghoff, L.; Andersen, J.S.; Mann, M.; Flad, M.; Hornberger, M.R.; Stahl, B.; Bonhoeffer, F.; et al. RGM is a repulsive guidance molecule for retinal axons. Nature 2002, 419, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, K.; Fujitani, M.; Yasuda, Y.; Doya, H.; Saito, T.; Yamagishi, S.; Mueller, B.K.; Yamashita, T. RGMa inhibition promotes axonal growth and recovery after spinal cord injury. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 173, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, T.A.; Srinivasan, A.; Karchewski, L.A.; Jeong, S.J.; Campagna, J.A.; Ji, R.R.; Fabrizio, D.A.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, H.Y.; Bell, E.; et al. DRAGON: A member of the repulsive guidance molecule-related family of neuronal- and muscle-expressed membrane proteins is regulated by DRG11 and has neuronal adhesive properties. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 2027–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).