1. Introduction

Noise-Induced Hearing Loss

According to the 2020 World report on hearing by the World Health Organization [

1], disabling hearing loss affects over 5% of the global population, with SNHL being a major contributor. SNHL can result from various factors, including vascular disorders, viral infections, ototoxic drugs, systemic inflammation, labyrinthine membrane degeneration, and NIHL. Prolonged exposure to loud sounds, typically above 85 dB, leads to permanent hearing loss and related health issues.

NIHL is a very prominent type of SNHL, specifically pronounced among adults.

In Two different conditions have to be separated: acute acoustic trauma caused by e.g., blast exposure and hearing loss as a consequence of chronic noise exposure. this review, we focus on NIHL based on ongoing noise trauma. It is the result of ongoing high levels of occupational, military, and recreational noise to name the most common triggers [

2]. Specifically, young people are at risk of NIHL development due to the increasing use of headphones to enjoy music. Individuals exposed to sound higher than 85 dB for more than 5 hours weekly are prone to suffer permanent hearing damage over time, while adverse, while importantly, the relationship between hearing loss caused by occupational noise and the risk of the different adverse health effects varies, among other things, with the level of frequency [

2]. Taken together, the World Health Organization reports that in sum loud sound exposure is acknowledged to potentially cause NIHL in more than 600 million people worldwide [

1].

This paper will provide an overview of NIHL, its pathophysiology, its impact on membrane transporters, channels, and BLB structures, and the auditory and non-auditory effects of noise impacting on the cardiovascular system. We offer timely solutions for its treatment as well as of its major comorbidity, hypertension, providing potential solutions to this widespread issue. Specifically, As we develop innovative means of prevention and treatment, we take advantage of recent advances in neuromodulation and vector-based approaches, which offer hope for countering autonomic imbalances and overcoming biological barriers like the BLB.

2. Auditory Structures and Functions Impacted by Noise

Ongoing acoustic exposure can induce a level of damage that is accompanied by temporary threshold shift (TTS) or impairments accompanied by permanent threshold shift (PTS). Despite previous assumptions, recurrent episodes of TTS may not be related to PTS in the long term, as it was believed in previous years, because the two conditions are characterized by different pathogenetic mechanisms (for review see [

3]).

2.1. Mechanisms of TTS

TTS is defined by, at least, 10 dB of threshold elevation in one or more frequencies between 2 and 4 kHz. This threshold shift may reach 50 dB [

4]. TTS lasts from minutes to days depending on the pathophysiology of the damage. Low-level TTS is mediated by ion channels that are activated by extracellular ATP [

5]. The relevant ATP receptor P2RX2 is a nonselective cation channel, expressed in cochlear hair cells (HCs) and epithelial cells lining the scala media. Noise stimulates local ATP release in the cochlea, the ATP opens the channels, which then shunt endocochlear current away from the HC transduction channel [

3]).

Higher levels of TTS (up to 50 dB) are due to additional mechanisms such as uncoupling of the outer HC stereocilia from the tectorial membrane [

6] and swelling of the afferent endings underneath the inner HCs, suggestive of excitotoxicity due to the release of excessive glutamate from overstimulated HCs [

3]).

Other evidence suggests that damaging levels of noise lead to metabolic overstimulation and subsequent generation of free radical species [

7,

8]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS).

2.2. Mechanisms of PTS

When exposed to a sufficiently loud and long-lasting noise, the cochlea’s ability to recover gets overwhelmed, leading to irreversible hearing loss. This kind of hearing loss is mainly linked to damage and loss of cochlear HCs, but damage to neurons and other parts of the cochlea can also contribute to PTS [

3]. This damage can directly disrupt the stereocilia [

9], which diminishes or completely stops their function. In severe cases, the damage can even affect the overall structure of the sensory part of the cochlea, disrupting HC and their support cells. This kind of damage can also create a connection between two fluid-filled areas in the cochlea, endolymph, and perilymph, allowing excessive levels of potassium to reach the basal poles of remaining intact HCs, leading to their death. However, damaging levels of noise begin well below the threshold of such frank mechanical damage. The majority of NIHL is caused by damage to HC through biochemical processes that occur within the cells themselves via ROS production as in the case of TTS.

2.3. TTS, PTS, and Free Radical Impact

The cascade of events initiated by ROS induction entails lipid peroxidation within the cochlea, thereby giving rise to the generation of highly noxious metabolic byproducts. While the products of lipid peroxidation alone can induce apoptosis, lipid peroxidation byproducts possessing vasoactive properties, such as isoprostanes, may potentially contribute to a diminished blood supply to the cochlea [

10]. Noise-induced ischemia and subsequent reperfusion might further potentiate the generation of ROS in a positive feedback loop [

3]. Furthermore, ROS-mediated mechanisms encompass the provocation of inflammatory responses, including the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) which themselves hold the capability to inflict damage upon the cochlear structure and function [

11].

3. The Role of Stria Vascularis in NIHL

Recent investigations highlight the role of the stria vascularis (SV), located in the lateral wall of the cochlea, in the pathogenesis of NIHL [

12]. A previous study highlighted that loud noise exposure could lead to a reduced vessel diameter, while concomitantly an increase in vascular permeability in the SV [

13], and increased macromolecular transport was observed that could decrease the endocochlear potential (EP) [

12]. However, the underlying mechanism remains unclear and might however be potentially related to the formation of excess ROS, RNS, release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and ultimately excitotoxicity, as detailed above (com. 1.1.1. - 1.1.3.).

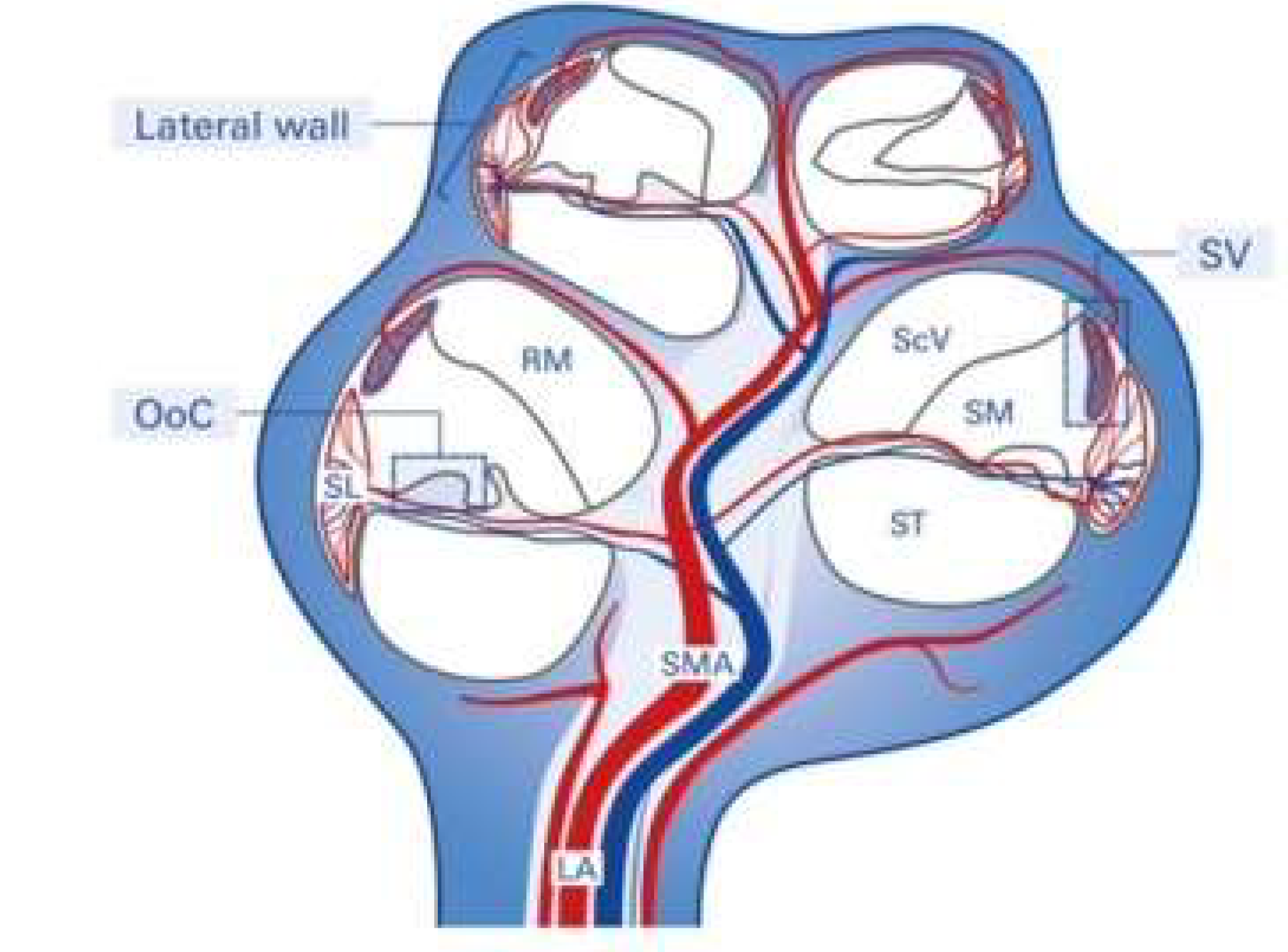

The SV is derived from the spiral modiolar artery supplying the organ of Corti (OoC) and primary auditory neurons (

Figure 1) and is mainly composed of marginal, intermediate, and basal cells and the endothelial cells forming the so-called strial BLB (

Figure 2).

Anatomically, the blood supply to the cochlea comes from the common cochlear artery, which divides into the spiral modiolar artery and the vestibulocochlear artery. The spiral modiolar artery supplies the apical turns of the cochlea, and the cochlear branch of the vestibulocochlear artery supplies the basal turns of the cochlea (

Figure 1). The spiral modiolar artery supplies the OoC and primary auditory neurons of the modiolus and forms the capillaries of the spiral ligament and

stria vascularis in the cochlear lateral wall. Strial capillaries are nonfenestrated with tight junctions between adjacent endothelial cells and a decreasing rate of entry into perilymph from blood by compounds of increasing molecular weight [

14,

15], forming a barrier that separates intrastrial fluids from blood, the BLB. Historically, the concept of the strial BLB in the inner ear originated from the observed difference in the chemical composition of blood and inner ear fluids (

Figure 2).

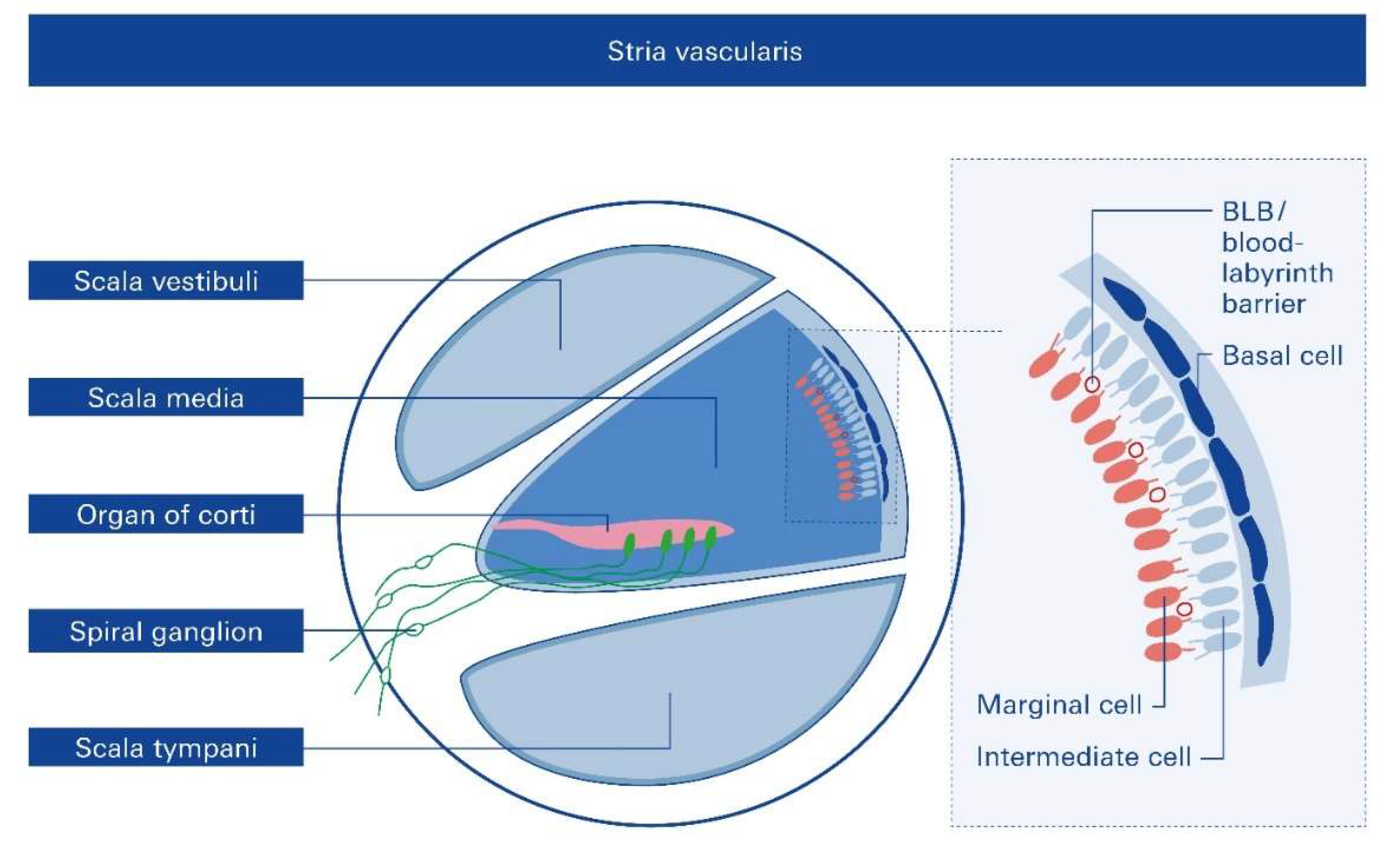

Significant functions of the SV are to i) generate the endocochlear potential (EP), which is essential for an audition, ii) secretion of endolymph, and iii) maintain cochlear homeostasis by controlling ion homeostasis and substance exchanges between blood and the interstitial space in the cochlea at the level of the endothelial BLB (

Figure 2).

4. The Blood-Labyrinth Barrier (BLB) – Functional Contribution to SNHL Pathologies

The strial BLB is a highly specialized network of capillaries tightly controlling the permeability of the capillaries and controlling macromolecular exchange between blood and the interstitial space in the cochlea [

16,

17]. The strial BLB thus maintains cochlear homeostasis and protects the cochlea from blood-borne potentially ototoxic endobiotics and xenobiotics.

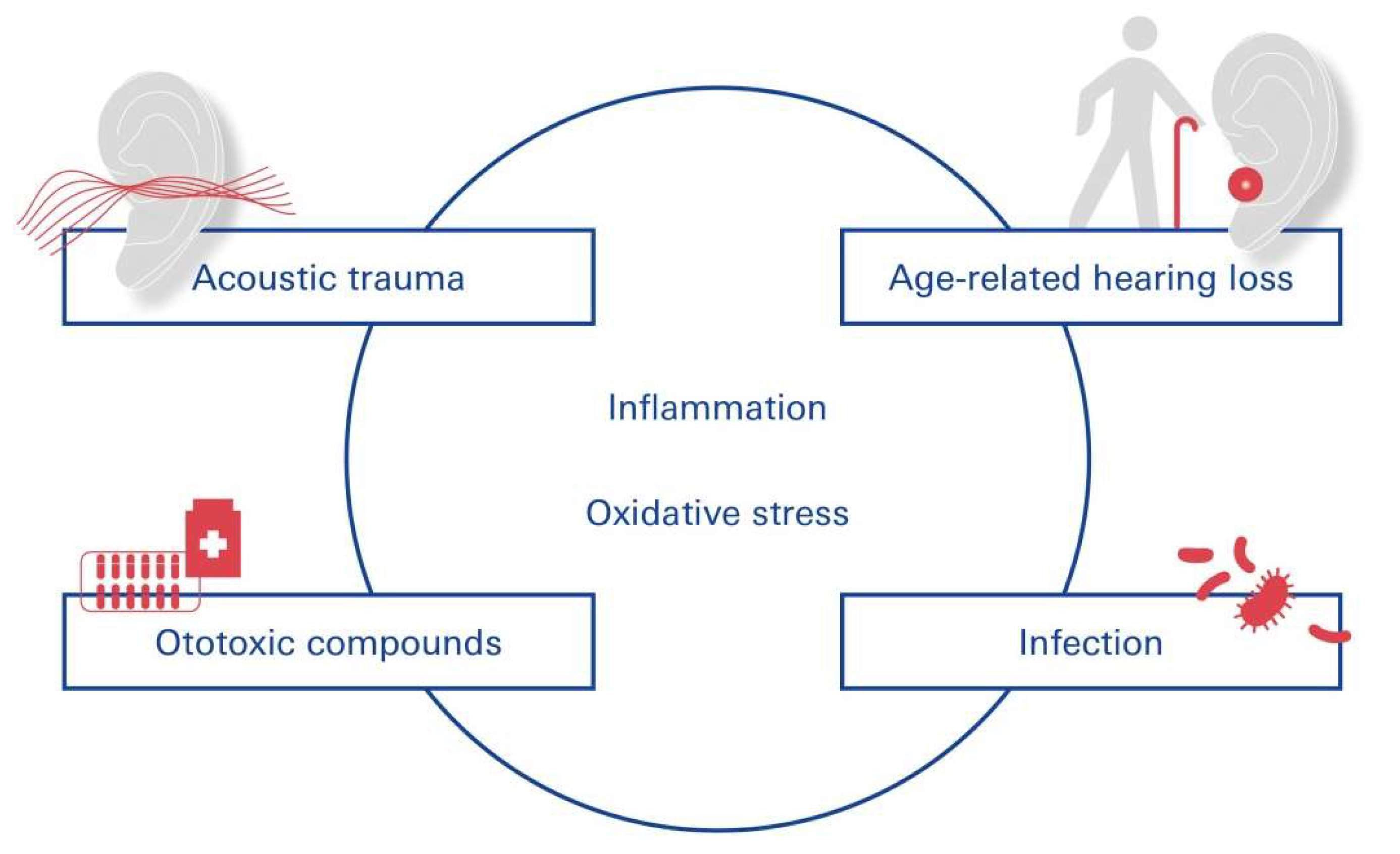

The strial BLB is fundamentally similar to the blood-brain barrier (BBB) that separates brain interstitial fluid from blood (

Figure 1): the BLB separates the inner ear fluid compartments (perilymph and endolymph) from capillaries of the vasculature and is composed of vascular endothelial cells coupled together by tight junctions. The BLB is critical for the maintenance of the inner ear fluid ionic homeostasis and for the prevention of the entry of deleterious substances into the inner ear. Recent studies have implicated loss of the integrity of the BLB in several inner ear pathologies including acoustic trauma, infection, ototoxin-induced hearing loss, and age-related hearing loss (presbycusis).

In this connection, loud sounds affect almost all cochlear cell types and induce inflammation and drug-induced cochleotoxicity. Acoustic trauma [

18] pertains prominently to the several external and intrinsic factors that can profoundly modulate the permeability of the BLB [

19], increasing its permeability and subsequent uptake of drugs indirectly by inducing inflammation and degeneration of sensory cells and auditory neurons (

Figure 3).

Different disease states in comorbidity to NIHL can alter BLB physiology and increase its permeability through inflammation and oxidative stress: cochlear inflammation [

11]. caused by acoustic trauma in turn contributes to the degeneration of cochlear sensory cells.

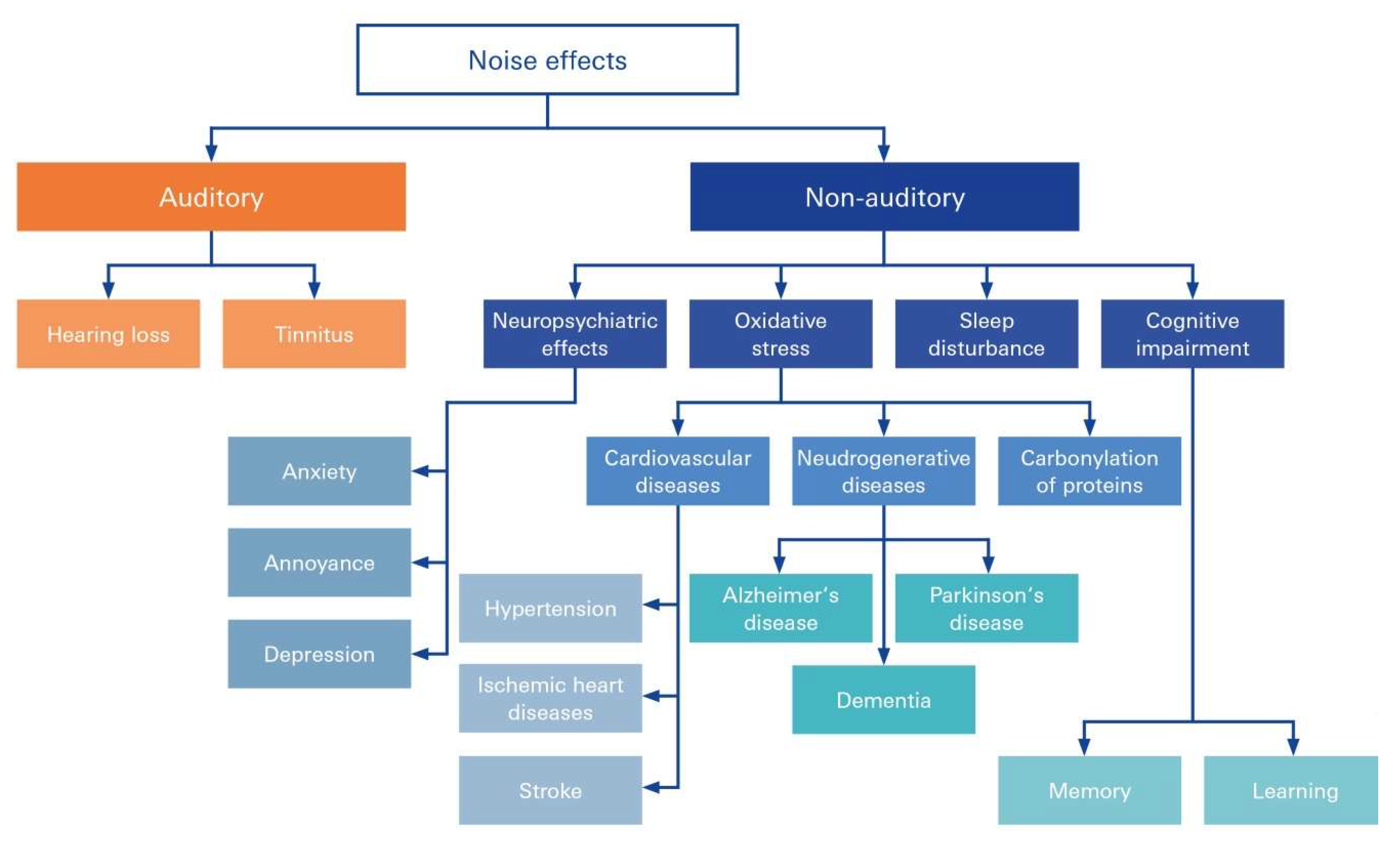

5. Spectrum of NIHL-Associated Disorders

Repeated overexposure to noise at or above 85 dB can cause permanent hearing loss, tinnitus, and difficulty in understanding speech in noise. It is also associated with cardiovascular disease, depression, balance problems, cognitive dysfunction (children), and lower-income [

20]. In case untreated, NIHL has a high propensity to establish fatigue, communication difficulty, social isolation, and stress [

21]. Damage to the SV in NIHL has progressively been recognized to be at the root of many common disorders and syndromic diseases accompanied with NIHL, many of which are cerebro- and cardiovascular disease: Accumulation of noise-induced damage to the inner ear is a key trigger of age-related hearing loss and cognitive decline [

16], tinnitus and even diminished learning and cognitive abilities in children and adolescents [

22] (

Figure 4).

Chronic, subjective tinnitus, an auditory phantom sensation in the absence of physical stimuli, can be triggered by a variety of causes that may act synergistically [

23]. However, scientists generally agree that tinnitus is generated within the brain in response to a reduction of auditory nerve fiber input from the cochlea to the brain. By far the major cause of cochlear damage resulting in deafferentiation is environmental noise overexposure [

23,

24]. Of note, besides noise-induced tinnitus [

23] about 64% of patients with NIHL exhibited comorbidities, and the most common condition was hypertension.

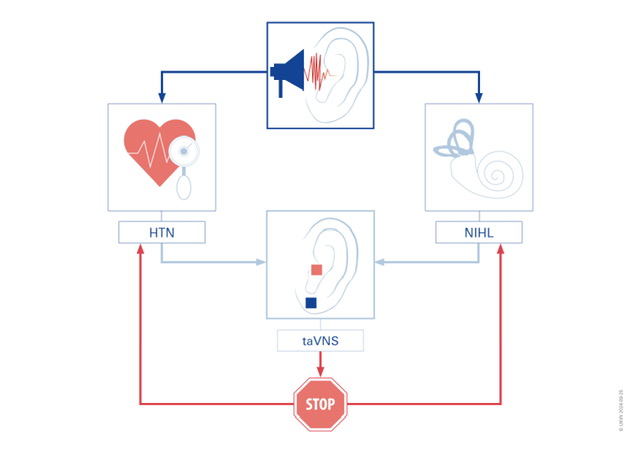

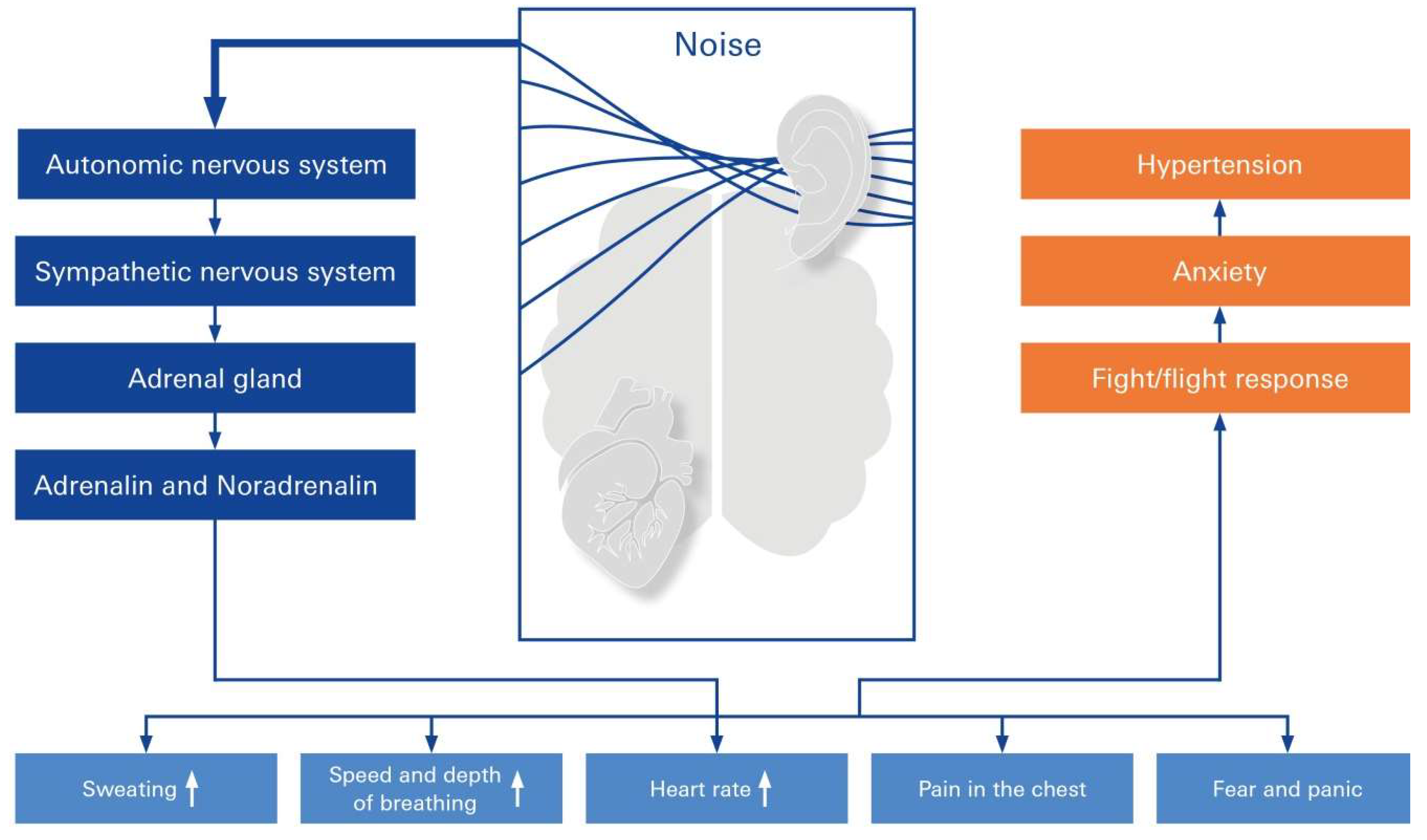

6. Noise above the Permissive Threshold May Beget Autonomic Changes and Hypertension

There was a higher incidence of hypertension among patients with sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL) when compared to 54,946 matched controls [

25]. There is biological plausibility that sustained noise exposure may result in health effects related to stress after acute noise exposure (

Figure 5). Specifically, there appears to be an increased risk of hypertension associated with noise-induced high-frequency hearing loss, and the risk varies by age and work experience [

25]: the presence of elevated noise exposure was associated with an increased risk of hypertension in a meta-analysis of 32 studies involving 264,678 participants. A significant dose-response relationship between noise exposure and hypertension was found [

26].

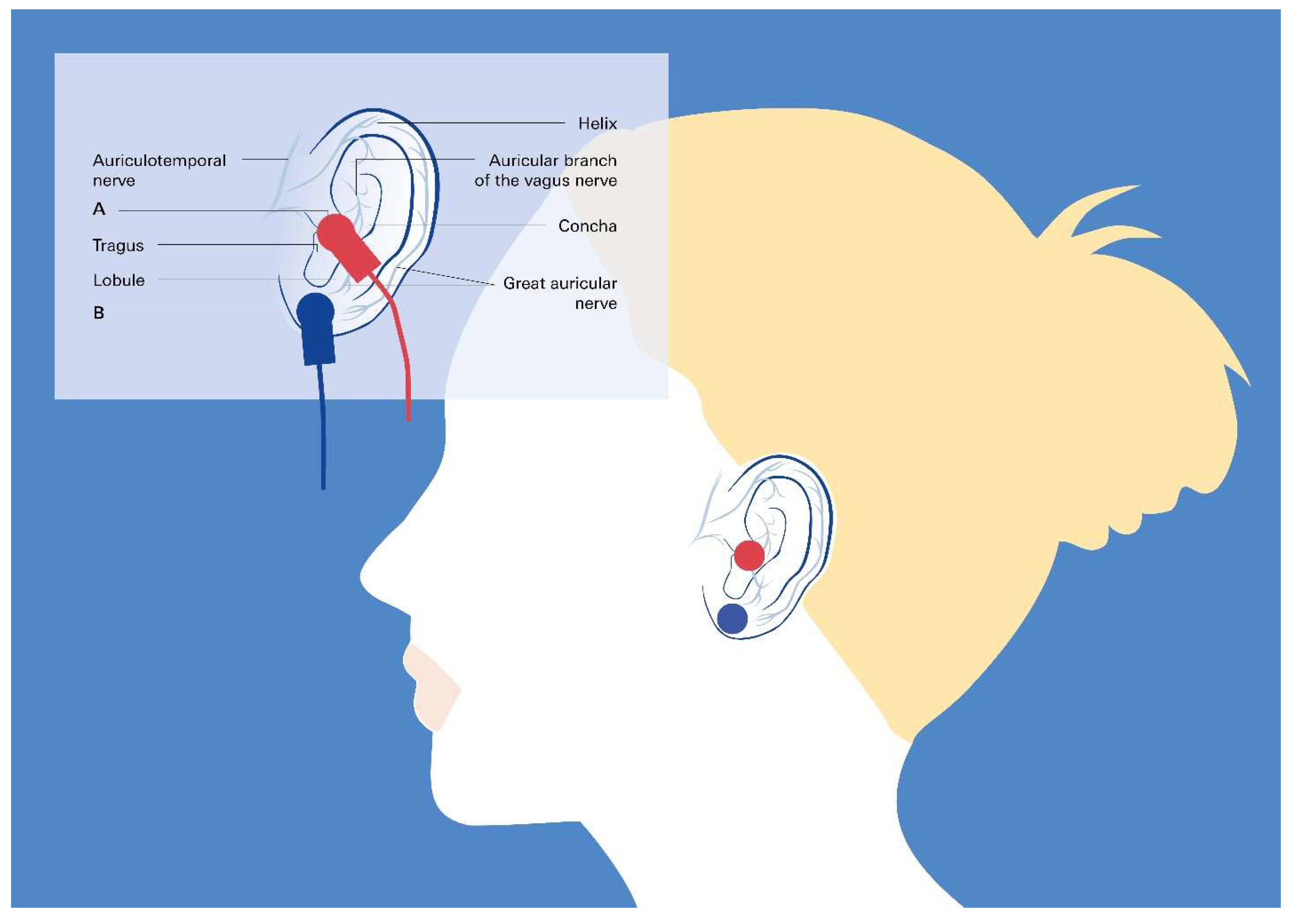

7. A New Method for Preventing and Treating NIHL and Hypertension Using Vagus Nerve Stimulation

It has been consistently demonstrated that noise, be it environmental, leisure-derived, or occupational, above the permissible limit of 85 dB leads to autonomic changes and alterations in blood pressure [

27,

28,

29]. In the following section we provide an incentive for NIHL’s future clinical translation for prevention and therapy by Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS): The use of VNS has become increasingly popular as a prevention and treatment method for a number of clinical conditions, such as migraines, tinnitus, and depression [

30,

31]. Robust approaches have been developed in response to growing scientific knowledge about the vagus nerve (VNS) and insights into the anatomy/conduction and function of the VN. The cutaneous distribution of afferent VN fibers in the auricle, or the auricular branch of the VN (ABVN), is used in the taVNS application. By stimulating the ABVN in the tragus, tVNS is a simple, non-invasive emergency treatment that has become widely used worldwide. It has few side effects [

32]. Recent research on animals addressed tVNS and hypertension. The outcome of this research presents the taVNS as a preventive option for both pathologies, NIHL and hypertension, since these studies clearly show a relationship between tVNS application and an increased HRV and a slower progression of chronic hypertension without altering fibrosis in hypertensive rats.

While there is still the possibility that NIHL may lead to dampening of the vagus nerve, one can imply from the positive results of tVNS treatment on tinnitus conditions obtained so far, that stimulation of the vagus nerve may may have a positive effect on NIHL as well. Hence, vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) may be an emerging therapeutic option to treat and possibly even prevent NIHL. VNS is increasingly being used to treat conditions such as epilepsy, depression, and chronic inflammation, as well as an aid to rehabilitation, and also as a technique for cognitive improvement [

31]. Nonetheless, VNS requires implantation of a device using an invasive technique, which may not be acceptable by many patients [

33]. These limitations led to the development of transcutaneous VNS (tVNS), by stimulating the auricular branch of the vagus nerve at the tragus or the concha of the ear [

32]. This technique is associated with minimal risk, thus opening up the possibility for novel applications even in healthy individuals (

Figure 6).

taVNS in combination with tone therapy has been demonstrated to be an efficient and safe method not show significant side effects. Several preclinical and small cohort clinical studies help foster this assumption to combine taVNS with tones to improve auditory processing, e.g., in patients with tinnitus or possibly NIHL [

31]. Towards acquired hearing loss following noise trauma, one could refer to reports in animals showing that VNS paired with specific tones improved tinnitus in follow-up and was sufficient to reverse the abnormal plasticity of the primary auditory cortex shown to be associated with tinnitus [

34] . On the other hand, pilot clinical studies highlight the feasibility and safety of VNS paired with tones in patients with moderate to severe chronic tinnitus [

35]. These studies combined with reported beneficial effects on hypertension [

36,

37,

38,

39] and heart failure [

40,

41], with minimal, if any, side effects, give sufficient evidence that studies on this topic ought to be extended and moved forward.

Of note, non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation reduces disruption of the BBB which is intimately related to the BLB in a rat model of ischemic stroke [

42], so that a transferable effect to the strial BLB following NIHL can be assumed.

8. Conclusion

Loud sounds, typically above 85 decibels (dB), can lead to permanent hearing loss and hypertension as the most prominent health consequences. As sequelae of noise trauma and stress, we present NIHL and its primary comorbidity, hypertension, and investigate novel preventive measures. A substantial amount of evidence is presented in this paper to demonstrate that taVNS is suitable for developing future NIHL and hypertension treatments, thus providing possible solutions to this widespread issue.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y.F. and T.L.; methodology, C.Y.F., S.St. and V.S..; validation, T.L., S.St. and C.Y.F.; formal analysis, C.Y.F., V.S. and S.St.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S., C.Y.F., S.St. and T.L..; review and editing, V.S., C.Y.F., and S.St.; supervision, funding acquisition and project administration C.Y.F.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants DFG Fo 315/5-1 and investment contribution of foundation Forschung hilft to CYF.

Institutional Review Board Statement

none

Informed Consent Statement

none

Data Availability Statement

N/A

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are extended to Dr. J. Engert and Dr. K. Rak, University hospital Würzburg for helpful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ARHL: age-related hearing loss; BBB: blood-brain barrier; BLB: blood-labyrinth-barrier; EP: endocochlear potential; HC: hair cell; LA: labyrinth artery; NIHL: noise-induced hearing loss; OoC: organ of corti; PTS: permanent threshold shift; RM: Reissner membrane; ScV: scala vestibule; SL: spiral ligament; SMA: spiral modular artery; SM: scala media; SNHL: sensorineural hearing loss; SSNHL: sudden sensorineural hearing loss; ST: scala tympani; SV: stria vascularis; taVNS: transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation; TTS: temporary threshold shift; tVNS: transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation;

References

- Ghadri JR, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, Sharkey S, Dote K, Akashi YJ, et al. International Expert Consensus Document on Takotsubo Syndrome (Part I): Clinical Characteristics, Diagnostic Criteria, and Pathophysiology. European heart journal. 2018;39(22):2032-46. Epub 2018/06/01.

- Sharkey SW, Lesser JR, Maron MS, Maron BJ. Why not just call it tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy: a discussion of nomenclature. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(13):1496-7.

- Song BG, Yang HS, Hwang HK, Kang GH, Park YH, Chun WJ, et al. The impact of stressor patterns on clinical features in patients with tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy: experiences of two tertiary cardiovascular centers. Clin Cardiol. 2012;35(11):E6-13. Epub 20121001.

- Lyon AR, Bossone E, Schneider B, Sechtem U, Citro R, Underwood SR, et al. Current state of knowledge on Takotsubo syndrome: a Position Statement from the Taskforce on Takotsubo Syndrome of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(1):8-27. Epub 20151109.

- Elgendy AY, Elgendy IY, Mansoor H, Mahmoud AN. Clinical presentations and outcomes of Takotsubo syndrome in the setting of subarachnoid hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European heart journal Acute cardiovascular care. 2018;7(3):236-45. Epub 2016/11/18.

- Eitel I, von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F, Bernhardt P, Carbone I, Muellerleile K, Aldrovandi A, et al. Clinical characteristics and cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings in stress (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy. Jama. 2011;306(3):277-86.

- Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, Napp LC, Bataiosu DR, Jaguszewski M, et al. Clinical Features and Outcomes of Takotsubo (Stress) Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):929-38.

- Ghadri JR, Cammann VL, Napp LC, Jurisic S, Diekmann J, Bataiosu DR, et al. Differences in the Clinical Profile and Outcomes of Typical and Atypical Takotsubo Syndrome: Data From the International Takotsubo Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(3):335-40.

- Couch LS, Fiedler J, Chick G, Clayton R, Dries E, Wienecke LM, et al. Circulating microRNAs predispose to takotsubo syndrome following high-dose adrenaline exposure. Cardiovasc Res. 2022;118(7):1758-70.

- Jaguszewski M, Osipova J, Ghadri JR, Napp LC, Widera C, Franke J, et al. A signature of circulating microRNAs differentiates takotsubo cardiomyopathy from acute myocardial infarction. European heart journal. 2014;35(15):999-1006. Epub 2013/09/21.

- Nagai M, Shityakov S, Smetak M, Hunkler H, Bär C, Schlegel N, et al. Blood Biomarkers in Takotsubo Syndrome Point to an Emerging Role for Inflammaging in Endothelial Pathophysiology. Biomolecules. 2023;2023:995.

- Frank N, Nagai M, Förster C. Exploration of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation as a treatment option for adjuvant cancer and heart failure therapy. Exploration of Neuroprotective Therapy. 2023:363-97.

- Nagai M, Shityakov S, Smetak M, Hunkler HJ, Bar C, Schlegel N, et al. Blood Biomarkers in Takotsubo Syndrome Point to an Emerging Role for Inflammaging in Endothelial Pathophysiology. Biomolecules. 2023;13(6). Epub 2023/06/28.

- Ittner C, Burek M, Stork S, Nagai M, Forster CY. Increased Catecholamine Levels and Inflammatory Mediators Alter Barrier Properties of Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells in vitro. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2020;7:73. Epub 2020/05/21. [CrossRef]

- Karnati S, Garikapati V, Liebisch G, Van Veldhoven PP, Spengler B, Schmitz G, et al. Quantitative lipidomic analysis of mouse lung during postnatal development by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. PloS one. 2018;13(9):e0203464. Epub 2018/09/08.

- Nagai M, Dote K, Kato M, Sasaki S, Oda N, Kagawa E, et al. The Insular Cortex and Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23(6):879-88.

- Templin C, Hanggi J, Klein C, Topka MS, Hiestand T, Levinson RA, et al. Altered limbic and autonomic processing supports brain-heart axis in Takotsubo syndrome. European heart journal. 2019;40(15):1183-7. Epub 2019/03/05.

- Nagai M, Kishi K, Kato S. Insular cortex and neuropsychiatric disorders: a review of recent literature. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(6):387-94. Epub 20070409.

- George MS, Ketter TA, Parekh PI, Horwitz B, Herscovitch P, Post RM. Brain activity during transient sadness and happiness in healthy women. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(3):341-51.

- Reiman EM, Lane RD, Ahern GL, Schwartz GE, Davidson RJ, Friston KJ, et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of externally and internally generated human emotion. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(7):918-25.

- Damasio AR, Grabowski TJ, Bechara A, Damasio H, Ponto LL, Parvizi J, et al. Subcortical and cortical brain activity during the feeling of self-generated emotions. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(10):1049-56.

- Gu X, Hof PR, Friston KJ, Fan J. Anterior insular cortex and emotional awareness. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521(15):3371-88.

- Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(6):397-409.

- Béjean S, Sultan-Taïeb H. Modeling the economic burden of diseases imputable to stress at work. Eur J Health Econ. 2005;6(1):16-23.

- de Kloet ER, Joëls M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(6):463-75.

- Romier C, Bernassau JM, Cambillau C, Darbon H. Solution structure of human corticotropin releasing factor by 1H NMR and distance geometry with restrained molecular dynamics. Protein Eng. 1993;6(2):149-56.

- Trainer PJ, Faria M, Newell-Price J, Browne P, Kopelman P, Coy DH, et al. A comparison of the effects of human and ovine corticotropin-releasing hormone on the pituitary-adrenal axis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(2):412-7.

- Hillhouse EW, Grammatopoulos DK. The molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of the biological activity of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptors: implications for physiology and pathophysiology. Endocr Rev. 2006;27(3):260-86. Epub 20060216.

- Henckens MJ, Deussing JM, Chen A. Region-specific roles of the corticotropin-releasing factor-urocortin system in stress. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17(10):636-51. Epub 20160902.

- Carrasco GA, Van de Kar LD. Neuroendocrine pharmacology of stress. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463(1-3):235-72.

- McEwen BS, Sapolsky RM. Stress and cognitive function. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5(2):205-16.

- McEwen, BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(3):171-9.

- De Kloet ER, Derijk R. Signaling pathways in brain involved in predisposition and pathogenesis of stress-related disease: genetic and kinetic factors affecting the MR/GR balance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1032:14-34.

- Joëls M, Karst H, Alfarez D, Heine VM, Qin Y, van Riel E, et al. Effects of chronic stress on structure and cell function in rat hippocampus and hypothalamus. Stress. 2004;7(4):221-31.

- Willner, P. Chronic mild stress (CMS) revisited: consistency and behavioural-neurobiological concordance in the effects of CMS. Neuropsychobiology. 2005;52(2):90-110. Epub 20050719.

- Malta MB, Martins J, Novaes LS, Dos Santos NB, Sita L, Camarini R, et al. Norepinephrine and Glucocorticoids Modulate Chronic Unpredictable Stress-Induced Increase in the Type 2 CRF and Glucocorticoid Receptors in Brain Structures Related to the HPA Axis Activation. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58(10):4871-85. Epub 20210702.

- Allen AP, Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G. Biological and psychological markers of stress in humans: focus on the Trier Social Stress Test. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2014;38:94-124. Epub 2013/11/19.

- Wallstrom S, Ulin K, Maatta S, Omerovic E, Ekman I. Impact of long-term stress in Takotsubo syndrome: Experience of patients. European journal of cardiovascular nursing. 2016;15(7):522-8. Epub 2015/11/18.

- Chan C, Elliott J, Troughton R, Frampton C, Smyth D, Crozier I, et al. Acute myocardial infarction and stress cardiomyopathy following the Christchurch earthquakes. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68504. Epub 20130702.

- Sharkey SW, Windenburg DC, Lesser JR, Maron MS, Hauser RG, Lesser JN, et al. Natural history and expansive clinical profile of stress (tako-tsubo) cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(4):333-41.

- Tagawa M, Nakamura Y, Ishiguro M, Satoh K, Chinushi M, Kodama M, et al. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning developing after the Central Niigata Prefecture Earthquake: two case reports. J Cardiol. 2006;48(3):153-8.

- Ghadri JR, Sarcon A, Diekmann J, Bataiosu DR, Cammann VL, Jurisic S, et al. Happy heart syndrome: role of positive emotional stress in takotsubo syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(37):2823-9. Epub 20160302.

- Scheitz JF, Mochmann HC, Witzenbichler B, Fiebach JB, Audebert HJ, Nolte CH. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy following ischemic stroke: a cause of troponin elevation. J Neurol. 2012;259(1):188-90. Epub 20110618.

- Modi S, Baig W. Radiotherapy-induced Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2009;21(4):361-2. Epub 20090218.

- S YH, Settergren M, Henareh L. Sepsis-induced myocardial depression and takotsubo syndrome. Acute Card Care. 2014;16(3):102-9. Epub 20140623.

- Brezina P, Isler CM. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 Pt 2):450-2.

- Riera M, Llompart-Pou JA, Carrillo A, Blanco C. Head injury and inverted Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. J Trauma. 2010;68(1):E13-5.

- Stöllberger C, Wegner C, Finsterer J. Seizure-associated Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Epilepsia. 2011;52(11):e160-7. Epub 20110721.

- Hjalmarsson C, Oras J, Redfors B. A case of intracerebral hemorrhage and apical ballooning: An important differential diagnosis in ST-segment elevation. Int J Cardiol. 2015;186:90-2. Epub 20150318.

- Murakami T, Yoshikawa T, Maekawa Y, Ueda T, Isogai T, Sakata K, et al. Gender Differences in Patients with Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy: Multi-Center Registry from Tokyo CCU Network. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0136655. Epub 20150828.

- Krishnamoorthy P, Garg J, Sharma A, Palaniswamy C, Shah N, Lanier G, et al. Gender Differences and Predictors of Mortality in Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy: Analysis from the National Inpatient Sample 2009-2010 Database. Cardiology. 2015;132(2):131-6. Epub 20150707.

- Yoshizawa M, Itoh T, Morino Y, Taniai S, Ishibashi Y, Komatsu T, et al. Gender Differences in the Circadian and Seasonal Variations in Patients with Takotsubo Syndrome: A Multicenter Registry at Eight University Hospitals in East Japan. Intern Med. 2021;60(17):2749-55. Epub 20210322.

- Angelini P, Tobis JM. Is high-dose catecholamine administration in small animals an appropriate model for takotsubo syndrome? Circ J. 2015;79(4):897. Epub 20150305.

- Duma D, Collins JB, Chou JW, Cidlowski JA. Sexually dimorphic actions of glucocorticoids provide a link to inflammatory diseases with gender differences in prevalence. Sci Signal. 2010;3(143):ra74. Epub 20101012.

- Lindheim SR, Legro RS, Bernstein L, Stanczyk FZ, Vijod MA, Presser SC, et al. Behavioral stress responses in premenopausal and postmenopausal women and the effects of estrogen. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167(6):1831-6.

- Kudielka BM, Schmidt-Reinwald AK, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C. Psychological and endocrine responses to psychosocial stress and dexamethasone/corticotropin-releasing hormone in healthy postmenopausal women and young controls: the impact of age and a two-week estradiol treatment. Neuroendocrinology. 1999;70(6):422-30.

- Ueyama T, Hano T, Kasamatsu K, Yamamoto K, Tsuruo Y, Nishio I. Estrogen attenuates the emotional stress-induced cardiac responses in the animal model of Tako-tsubo (Ampulla) cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;42 Suppl 1:S117-9.

- Ueyama T, Ishikura F, Matsuda A, Asanuma T, Ueda K, Ichinose M, et al. Chronic estrogen supplementation following ovariectomy improves the emotional stress-induced cardiovascular responses by indirect action on the nervous system and by direct action on the heart. Circ J. 2007;71(4):565-73.

- Rivera CM, Grossardt BR, Rhodes DJ, Brown RD, Jr., Roger VL, Melton LJ, 3rd, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality after early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause. 2009;16(1):15-23.

- Brenner R, Weilenmann D, Maeder MT, Jörg L, Bluzaite I, Rickli H, et al. Clinical characteristics, sex hormones, and long-term follow-up in Swiss postmenopausal women presenting with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol. 2012;35(6):340-7. Epub 20120409.

- Zhao D, Guallar E, Ouyang P, Subramanya V, Vaidya D, Ndumele CE, et al. Endogenous Sex Hormones and Incident Cardiovascular Disease in Post-Menopausal Women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(22):2555-66.

- Barros RP, Machado UF, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptors: new players in diabetes mellitus. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12(9):425-31. Epub 20060804.

- Zhu Y, Bian Z, Lu P, Karas RH, Bao L, Cox D, et al. Abnormal vascular function and hypertension in mice deficient in estrogen receptor beta. Science. 2002;295(5554):505-8.

- Komesaroff PA, Esler MD, Sudhir K. Estrogen supplementation attenuates glucocorticoid and catecholamine responses to mental stress in perimenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(2):606-10.

- Sung BH, Ching M, Izzo JL, Jr., Dandona P, Wilson MF. Estrogen improves abnormal norepinephrine-induced vasoconstriction in postmenopausal women. J Hypertens. 1999;17(4):523-8.

- Sader MA, Celermajer DS. Endothelial function, vascular reactivity and gender differences in the cardiovascular system. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53(3):597-604.

- Forster C, Kietz S, Hultenby K, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Characterization of the ERbeta-/-mouse heart. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(39):14234-9. Epub 2004/09/18.

- Dimberg U, Petterson M. Facial reactions to happy and angry facial expressions: evidence for right hemisphere dominance. Psychophysiology. 2000;37(5):693-6.

- Drača, S. A possible relationship between Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and female sex steroid-related modulation of functional cerebral asymmetry. Med Hypotheses. 2015;84(3):238-40. Epub 20150114.

- Singh K, Carson K, Shah R, Sawhney G, Singh B, Parsaik A, et al. Meta-analysis of clinical correlates of acute mortality in takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(8):1420-8. Epub 20140201.

- Pelliccia F, Parodi G, Greco C, Antoniucci D, Brenner R, Bossone E, et al. Comorbidities frequency in Takotsubo syndrome: an international collaborative systematic review including 1109 patients. Am J Med. 2015;128(6):654.e11-9. Epub 20150204.

- Pelliccia F, Sinagra G, Elliott P, Parodi G, Basso C, Camici PG. Takotsubo: One, no one and one hundred thousand diseases. Int J Cardiol. 2018;261:35.

- Jänig, W. The Integrative Action of the Autonomic Nervous System: Neurobiology of Homeostasis. UK: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

- Li Y, Jiang W, Li ZZ, Zhang C, Huang C, Yang J, et al. Repetitive restraint stress changes spleen immune cell subsets through glucocorticoid receptor or β-adrenergic receptor in a stage dependent manner. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;495(1):1108-14. Epub 20171123.

- Duma D, Jewell CM, Cidlowski JA. Multiple glucocorticoid receptor isoforms and mechanisms of post-translational modification. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;102(1-5):11-21. Epub 20061027.

- Rhen T, Cidlowski JA. Antiinflammatory action of glucocorticoids--new mechanisms for old drugs. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1711-23.

- Nagai M, Forster CY, Dote K. Sex Hormone-Specific Neuroanatomy of Takotsubo Syndrome: Is the Insular Cortex a Moderator? Biomolecules. 2022;12(1). Epub 2022/01/22.

- Walsh CP, Bovbjerg DH, Marsland AL. Glucocorticoid resistance and β2-adrenergic receptor signaling pathways promote peripheral pro-inflammatory conditions associated with chronic psychological stress: A systematic review across species. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;128:117-35. Epub 20210608.

- Walsh CP, Ewing LJ, Cleary JL, Vaisleib AD, Farrell CH, Wright AGC, et al. Development of glucocorticoid resistance over one year among mothers of children newly diagnosed with cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;69:364-73. Epub 20171218.

- Capitanio JP, Mendoza SP, Lerche NW, Mason WA. Social stress results in altered glucocorticoid regulation and shorter survival in simian acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(8):4714-9.

- Cole SW, Mendoza SP, Capitanio JP. Social stress desensitizes lymphocytes to regulation by endogenous glucocorticoids: insights from in vivo cell trafficking dynamics in rhesus macaques. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(6):591-7. Epub 20090624.

- Cole SW, Capitanio JP, Chun K, Arevalo JM, Ma J, Cacioppo JT. Myeloid differentiation architecture of leukocyte transcriptome dynamics in perceived social isolation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(49):15142-7. Epub 20151123.

- Oakley RH, Cidlowski JA. The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor: new signaling mechanisms in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(5):1033-44. Epub 20130929.

- Gonzalez Ramirez C, Villavicencio Queijeiro A, Jimenez Morales S, Barcenas Lopez D, Hidalgo Miranda A, Ruiz Chow A, et al. The NR3C1 gene expression is a potential surrogate biomarker for risk and diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry research. 2020;284:112797. Epub 2020/01/27.

- Ueyama T, Kasamatsu K, Hano T, Yamamoto K, Tsuruo Y, Nishio I. Emotional stress induces transient left ventricular hypocontraction in the rat via activation of cardiac adrenoceptors: a possible animal model of ‘tako-tsubo’ cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2002;66(7):712-3.

- Kume T, Kawamoto T, Okura H, Toyota E, Neishi Y, Watanabe N, et al. Local release of catecholamines from the hearts of patients with tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction. Circ J. 2008;72(1):106-8.

- Ortak J, Khattab K, Barantke M, Wiegand UK, Bänsch D, Ince H, et al. Evolution of cardiac autonomic nervous activity indices in patients presenting with transient left ventricular apical ballooning. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009;32 Suppl 1:S21-5.

- Vaccaro A, Despas F, Delmas C, Lairez O, Lambert E, Lambert G, et al. Direct evidences for sympathetic hyperactivity and baroreflex impairment in Tako Tsubo cardiopathy. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e93278. Epub 20140325.

- Pelliccia F, Kaski JC, Crea F, Camici PG. Pathophysiology of Takotsubo Syndrome. Circulation. 2017;135(24):2426-41.

- Ferrucci L, Semba RD, Guralnik JM, Ershler WB, Bandinelli S, Patel KV, et al. Proinflammatory state, hepcidin, and anemia in older persons. Blood. 2010;115(18):3810-6. Epub 20100115.

- Cohen HJ, Pieper CF, Harris T, Rao KM, Currie MS. The association of plasma IL-6 levels with functional disability in community-dwelling elderly. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52(4):M201-8. [CrossRef]

- Newman AB, Sanders JL, Kizer JR, Boudreau RM, Odden MC, Zeki Al Hazzouri A, et al. Trajectories of function and biomarkers with age: the CHS All Stars Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(4):1135-45. Epub 20160606.

- Gerli R, Monti D, Bistoni O, Mazzone AM, Peri G, Cossarizza A, et al. Chemokines, sTNF-Rs and sCD30 serum levels in healthy aged people and centenarians. Mech Ageing Dev. 2000;121(1-3):37-46. [CrossRef]

- Pallauf K, Rimbach G. Autophagy, polyphenols and healthy ageing. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(1):237-52. Epub 20120406.

- Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Kauppinen A. Inflammaging: disturbed interplay between autophagy and inflammasomes. Aging (Albany NY). 2012;4(3):166-75.

- O’Donovan A, Pantell MS, Puterman E, Dhabhar FS, Blackburn EH, Yaffe K, et al. Cumulative inflammatory load is associated with short leukocyte telomere length in the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19687. Epub 20110513.

- Shiels PG, McGlynn LM, MacIntyre A, Johnson PC, Batty GD, Burns H, et al. Accelerated telomere attrition is associated with relative household income, diet and inflammation in the pSoBid cohort. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e22521. Epub 20110727.

- Aviv A, Valdes A, Gardner JP, Swaminathan R, Kimura M, Spector TD. Menopause modifies the association of leukocyte telomere length with insulin resistance and inflammation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(2):635-40. Epub 20051122.

- Houben JM, Moonen HJ, van Schooten FJ, Hageman GJ. Telomere length assessment: biomarker of chronic oxidative stress? Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44(3):235-46. Epub 20071010.

Figure 1.

Structure and blood supply of the cochlea. The spiral modiolar artery supplies the OoC of the modiolus and forms the capillaries of the spiral ligament and stria vascularis in the cochlear lateral wall. SMA = spiral modular artery, SL = spiral ligament, SV = Stria vascularis, OoC = organ of corti, ScV = Scala vestibuli, SM = Scala media, ST = Scala tympani, RM = Reissner membrane, LA = labyrinthinth artery.

Figure 1.

Structure and blood supply of the cochlea. The spiral modiolar artery supplies the OoC of the modiolus and forms the capillaries of the spiral ligament and stria vascularis in the cochlear lateral wall. SMA = spiral modular artery, SL = spiral ligament, SV = Stria vascularis, OoC = organ of corti, ScV = Scala vestibuli, SM = Scala media, ST = Scala tympani, RM = Reissner membrane, LA = labyrinthinth artery.

Figure 2.

Cross section of one cochlea turn and rough structure of the stria vascularis, SV. Structural and functional damage to the SV mediated by noise trauma, specifically to the endothelial blood-labyrinth barrier, BLB, causes hearing loss, but the underlying mechanisms remain mostly unclear.

Figure 2.

Cross section of one cochlea turn and rough structure of the stria vascularis, SV. Structural and functional damage to the SV mediated by noise trauma, specifically to the endothelial blood-labyrinth barrier, BLB, causes hearing loss, but the underlying mechanisms remain mostly unclear.

Figure 3.

SNHL - functional contribution of the BLB. Pathogenes leading SNHL include vascular disorders, viral infections, noise trauma, ototoxic drug exposure, and age-related degeneration of the labyrinthine membrane.

Figure 3.

SNHL - functional contribution of the BLB. Pathogenes leading SNHL include vascular disorders, viral infections, noise trauma, ototoxic drug exposure, and age-related degeneration of the labyrinthine membrane.

Figure 4.

auditory and non-auditory effects of noise overexposure. Noise is in everyday life and can lead to both auditory and non-auditory adverse health effects, including hearing loss, tinnitus, neuropsychiatric effects, and cognitive impairment; and secondary to triggered circuit conditions like e.g., cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disease, and hypertension.

Figure 4.

auditory and non-auditory effects of noise overexposure. Noise is in everyday life and can lead to both auditory and non-auditory adverse health effects, including hearing loss, tinnitus, neuropsychiatric effects, and cognitive impairment; and secondary to triggered circuit conditions like e.g., cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disease, and hypertension.

Figure 5.

stress-response elicited by elevated noise. Pathways of elevated noise action leading to hypertension through mental stress, autonomic nervous system change sympathetic imbalance, anxiety, and neurohormonal mechanisms. The elevated risk factors noise exposure because of a primary rudimentary stress reaction, mediated either by activation of the sympathetic nervous system or the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis resulting in fight/ flight response, anxiety, and hypertension.

Figure 5.

stress-response elicited by elevated noise. Pathways of elevated noise action leading to hypertension through mental stress, autonomic nervous system change sympathetic imbalance, anxiety, and neurohormonal mechanisms. The elevated risk factors noise exposure because of a primary rudimentary stress reaction, mediated either by activation of the sympathetic nervous system or the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis resulting in fight/ flight response, anxiety, and hypertension.

Figure 6.

Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation targeting the auricular branch of the vagus nerve: taVNS. Non-invasive taVNS delivery systems rely on the cutaneous distribution of vagal fibers, at the external ear (auricular branch of the vagus nerve) [

43] as detailed in the insert

. Red circles in the main image and clamps in the insert, respectively, represent the best anatomical sites for

A active left tragus stimulation by the taVNS device,

B blue circles and clamps represent sham control stimulation sites, respectively.

Figure 6.

Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation targeting the auricular branch of the vagus nerve: taVNS. Non-invasive taVNS delivery systems rely on the cutaneous distribution of vagal fibers, at the external ear (auricular branch of the vagus nerve) [

43] as detailed in the insert

. Red circles in the main image and clamps in the insert, respectively, represent the best anatomical sites for

A active left tragus stimulation by the taVNS device,

B blue circles and clamps represent sham control stimulation sites, respectively.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).