1. Introduction

Hormones are a diverse group of molecules that regulate biological processes and functions, such as growth, development, maturation, homeostasis, immune and neuronal response. Endocrine cells form endocrine glands or are dispersed in non-endocrine organs. All they release hormones in blood stream, which interact with their receptors on target cells and thus induce specific reaction throughout the body.

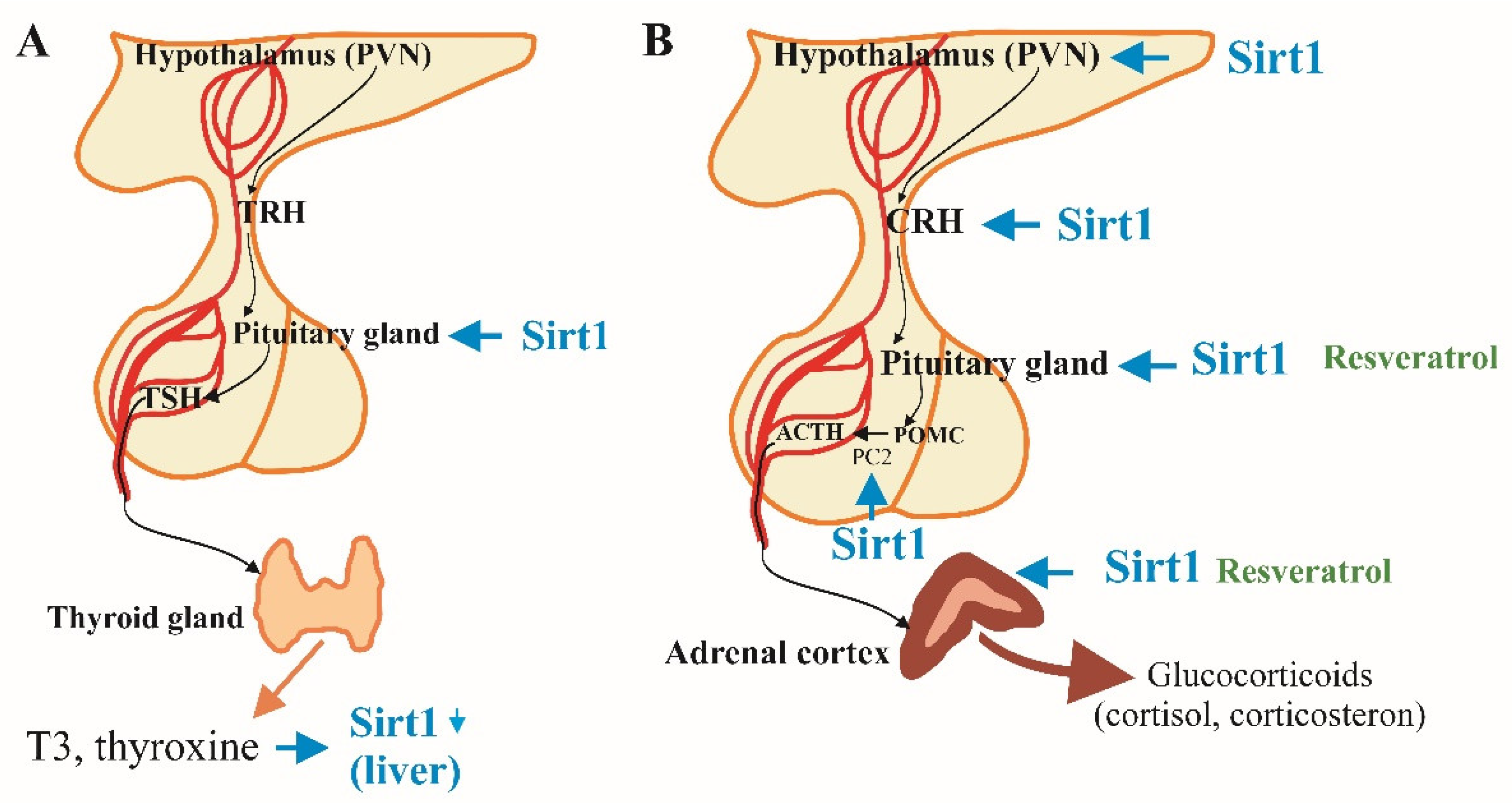

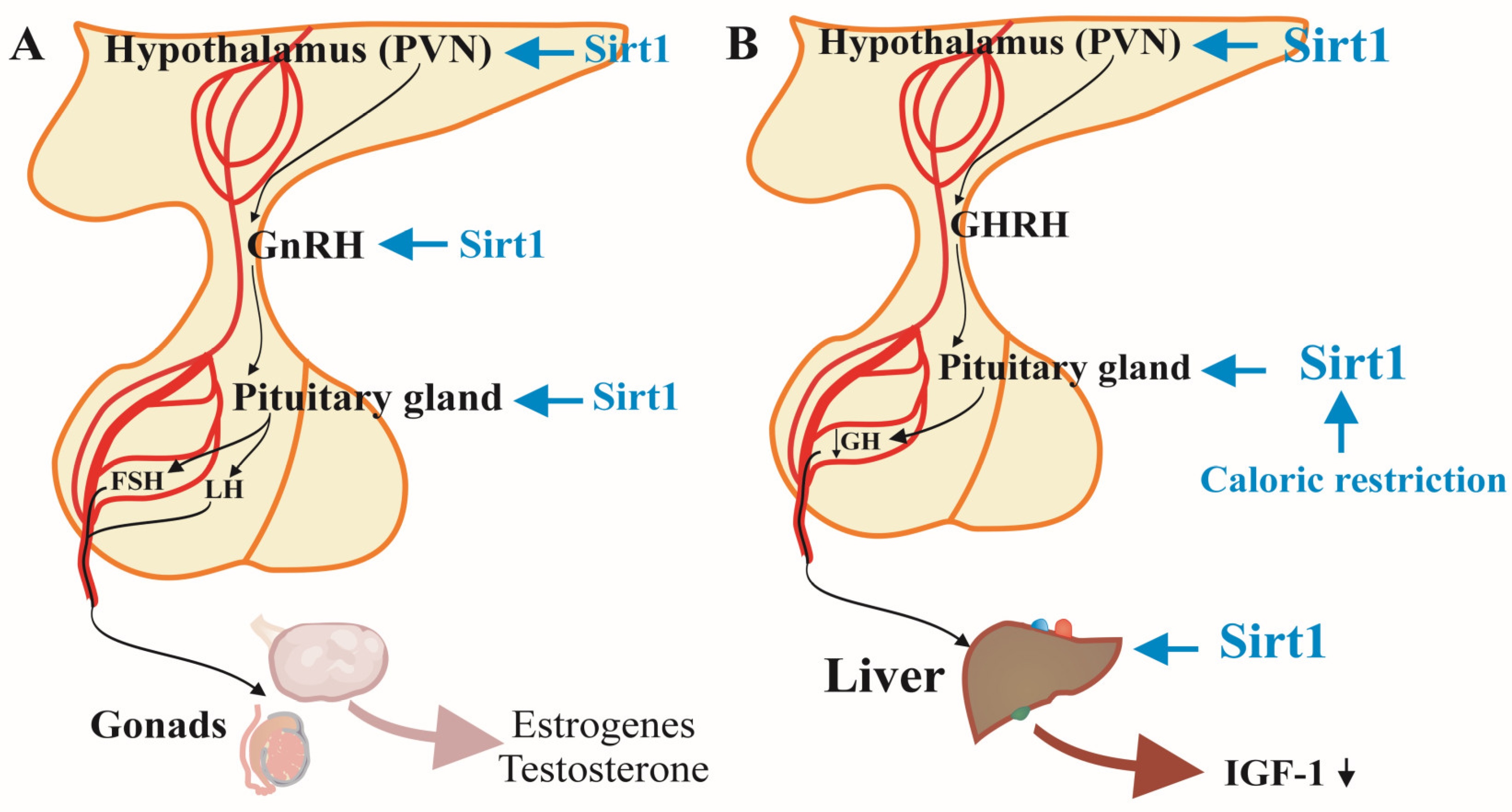

Hypothalamus is the key regulator of hormonal levels either directly via pituitary gland or indirectly by autonomic innervation. Several hormonal axes, initiating from the hypothalamus, play major role in the endocrine function. Different hypothalamic nuclei secrete releasing and inhibiting hormones that regulate the hormonal secretion of pituitary gland, the second participant in these axes. Pituitary tropic hormones downstream activate endocrine secretion of thyroid, adrenal, and gonadal glands, as well as of the liver via growth hormone (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2; [

1]). Additionally, hypothalamus secretes neurohormones vasopressin and oxytocin. Sympathetic autonomic neurons that are also under hypothalamic control activate the secretion of adrenalin, noradrenalin and dopamine from adrenal medulla [

1]. Autonomic nervous system regulates other endocrine cells as well.

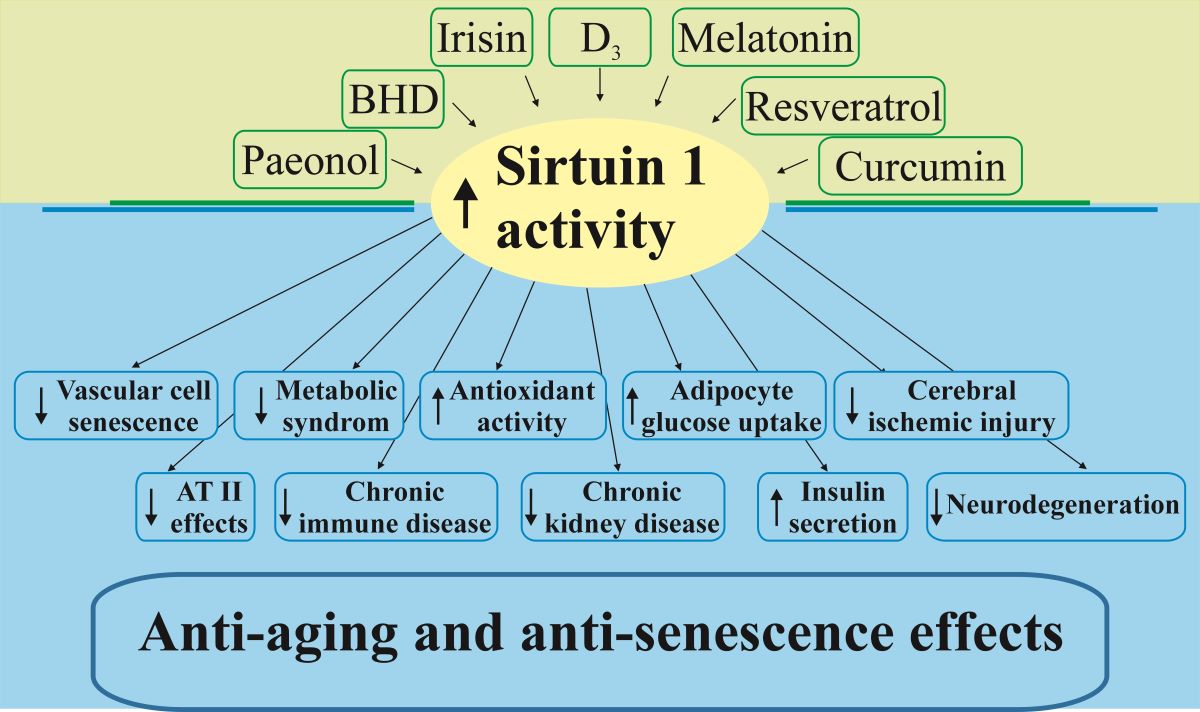

Aging is a process of gradual decline in physiological functions and an increased risk of various diseases, including cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurodegenerative disorders. Hormonal changes play a crucial role in the aging process, impacting homeostasis, metabolism, and overall health. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of sirtuins, particularly Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), in regulating various hormonal pathways that contribute to aging and age-related diseases. SIRT1 is the most important and studied member of the sirtuin family of NAD

+-dependent deacetylases with ADP-ribosyl transferase activity [

2]. SIRT1 is known for its ability to influence cellular homeostasis, stress response, and longevity by regulating the expression of key genes involved in metabolism, inflammation, oxidative stress and hormonal release [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Natural compounds like resveratrol, curcumin, and paeonol have been identified as activators of SIRT1, demonstrating potential therapeutic benefits in combating age-related hormonal imbalances and extending lifespan [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Despite these promising findings, the clinical application of SIRT1 activators is limited by low bioavailability and poor permeability across biological barriers, necessitating innovative delivery strategies.

This review aims to explore the multifaceted role of SIRT1 and some of its activators in hormonal regulation during aging, highlighting their potential for therapeutic interventions to mitigate age-related hormonal dysfunctions and enhance healthy aging.

2. SIRT1, Hypothalamus, and Endocrine Regulations

2.1. SIRT1 and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis

In individuals over the age of 80, thyroid hormone secretion undergoes significant changes, with increased levels of thyrotropin (TSH) and reduced synthesis of triiodothyronine (T3) [

9,

10]. Additionally, the half-life of T3 in blood plasma extends from seven days in younger adults to nine days in the elderly, reflecting age-related alterations in thyroid function [

10]. SIRT1 plays a significant role in the regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis by deacetylating phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase type-1 gamma (PI4P5K1), an enzyme that promotes the release of TSH from thyrotrophic cells in the pituitary gland [

11]. This process is essential for maintaining metabolic homeostasis [

11].

Research using SIRT1 knockout mice demonstrates that the absence of SIRT1 leads to decreased thyroxine (T4) secretion, resulting in weight loss and increased appetite, underscoring the importance of SIRT1 in thyroid hormone regulation [

12]. Interestingly, caloric restriction did not extend lifespan of this SIRT1 deficient mice. Additionally, the activity of the HPT axis affects SIRT1 expression; for instance, thyroxine suppresses SIRT1 expression in the liver of fasting mice, indicating a bidirectional relationship between thyroid hormones and SIRT1 activity (

Figure 1A, 2B) [

13].

2.2. SIRT1 and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis involves a complex signaling cascade that begins with the hypothalamic secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). CRH stimulates the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn prompts the cortex of adrenal glands to produce corticoids, primarily the glucocorticoid cortisol that mediate the stress response [

14,

15]. SIRT1 influences various components of the HPA axis, thereby modulating the body’s response to stress and maintaining homeostasis (

Figure 1B).

SIRT1 is highly expressed in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus, where it plays a critical role in regulating CRH production. Studies have shown that SIRT1 enhances the expression of prohormone convertases 1 and 2 (PC1/2), which are essential for converting the CRH precursor into its active form, thereby facilitating CRH secretion and maintaining the HPA axis activity [

15]. Additionally, SIRT1-activating molecules like resveratrol increases the half-life and activity of the adrenal gland enzyme P450 and thus enhances the cortisol synthesis and release [

16]. In aging, the production of cortisol increases, especially during the morning secretion peaks because the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland become less sensitive to the negative feedback by elevated plasma cortisol. For this reason, the stress-induced cortisol secretion is higher in elderly people. All these factors contribute for the adrenocortical-dependent predisposition to hypertension, hyperglycaemia, immunosuppression and, consequently, to higher risk of malignant, cognitive and other diseases [

10].

2.3. SIRT1 and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis

The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis involves a complex interplay of hormones that includes gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion from the hypothalamus, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) release from the pituitary, and sex steroid production from the gonads. SIRT1 influences this axis at multiple levels, highlighting its significance in maintaining reproductive health (

Figure 2A). Sex hormones orchestrate multiple processes by binding to specific receptors in many organs. The dramatic changes in sex hormones’ levels that occur naturally during aging expectedly alter the functions of different systems. Such example is the loss of the cardiovascular protective effect of estrogens due to the decreased estrogen secretion in the perimenopausal period in older women [

17]. Age-related changes in estrogen production and estrogen receptors (ER) are related to higher risk of hypertension, extreme salt-sensitivity, increased contractility of vascular smooth muscle and inflammatory pathologies in the kidney in rodents [

17]. Moreover, in human postmenopausal women in opposite to younger adults the beta subtype of ER dominates over the alfa-ER. Such disbalance between the receptor variations is a predisposition for cardiovascular problems [

18]. Moreover, sufficient estrogen levels prevent the hypertension in young females through inhibition of the sympathetic vasoconstrictor pathway [

19] and their postmenopausal drop is another risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. The reduced levels of both androgens and estrogens lead to impaired antioxidant capacity and decreased production of NO in the vascular tissues resulting in pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic changes [

20,

21]. Normal levels of sex hormones have anti-inflammatory effects on adhesive molecules, cytokines and immune cells in the blood vessels. Therefore, their decreased secretion in elderly men and women support pathological conditions like atherosclerosis [

17].

Menopause-induced changes in gonadotropin levels diminish the peak in luteinizing hormone secretion right before ovulation but increase its and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) pulse secretion. Data show a direct negative influence of higher FSH levels on bone density, visceral fat tissue accumulation and cardiovascular system and indirect positive effect of FSH on the bones [

22,

23,

24]. During the postmenopausal life most of the estrogens are produced by peripheral aromatization of androgenic hormones (androstenedione is converted into estrogen and testosterone - into estradiol). Since this reaction occurs predominantly in the fat tissue, obese postmenopausal women usually have higher levels of sex hormones (both estrogens and testosterone) [

10]. While the synthesis of estrogens typically drops during the menopause and remains low after it, the testosterone, produced by the ovarian theca cells sustains the pre-menopausal levels. Post-menopausal women with higher plasma testosterone levels are in a greater risk of coronary heart disease and metabolic syndrome development [

25].

SIRT1 plays a crucial role in the regulation of reproduction through hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (

Figure 2A). In SIRT1-knockout mice models the levels of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secreted by the hypothalamus were reduced and consequently decreased levels of luteinizing, follicle-stimulating and sex hormones and impaired gametogenesis occurred [

26,

27]. Additionally, SIRT1 deacetylation appears to be a common reaction in estrogen and insulin signaling for hormonal regulation of the adipocyte autophagy and fat tissue storage [

28].

Studies in SIRT1-knockout mouse models have demonstrated that the absence of SIRT1 leads to reduced GnRH secretion from the hypothalamus, which subsequently results in lower levels of LH and FSH and impaired sex steroid synthesis, culminating in defective gametogenesis and fertility issues [

29]. SIRT1 is also involved in modulating kisspeptin expression, a neuropeptide that plays a crucial role in stimulating GnRH secretion, thereby influencing the entire reproductive axis [

30,

31]. This regulatory mechanism is vital for maintaining reproductive function and fertility throughout life.

Furthermore, SIRT1 deficiency has been shown to decrease estrogen release leading to atherosclerosis and arterial senescence in mice [

32]. Estrogen is known to exert protective effects on the cardiovascular system, brain, and bones, and SIRT1’s modulation of estrogen signaling may contribute to the observed gender differences in aging and disease susceptibility [

29]. Additionally, SIRT1 has been found to influence energy balance and homeostasis, which involved insulin secretion and sensitivity, glucose and lipid metabolism that are closely linked to reproductive health [

28,

29]. These findings suggest that SIRT1-HPG axis interaction extends beyond reproductive function to encompass broader aspects of health and aging, positioning it as a potential target for therapeutic interventions aimed at mitigating age-related reproductive and metabolic disorders.

2.4. SIRT1 and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Liver Axis

The secretion of growth hormone (GH) from the pituitary gland typically declines every decade of human adult life by approximately 15%, that significantly impacting various physiological functions [

33]. The diminished growth hormone secretion and as a result the lower levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 increase the obesity, visceral fat tissue, as well as the risk of bone and muscle weakness, production of sex hormones, immune and sleep disturbances among elderly individuals [

10,

34]. The absence of SIRT1 expression in mural brains led to hypofunction of the pituitary somatotroph cells, critically low levels of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 and dwarfism phenotype of the mice [

35]. Moreover, in food deficiency, SIRT1 in the liver is reported to hinder the growth hormone-induced production of insulin-like growth factor 1 and thus suppressing the growth of the organism to redirect its resources towards survival mechanisms [

13]. SIRT1 participates in regulating this somatotropic axis, which links the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and liver (

Figure 2B) [

13,

26].

2.5. SIRT1 and Other Hormonal Regulations

The prevalence of type II diabetes increases significantly after the age of 65, largely due to decreased sensitivity of pancreatic beta cells to incretins and insufficient insulin secretion, combined with insulin resistance caused by obesity and reduced physical activity [

36]. In addition, elderly men are more affected by these conditions because of declining testosterone levels and altered metabolic profiles. Increased SIRT1 expression has been shown to reduce oxidative stress and prevent apoptosis in pancreatic beta cells, thereby enhancing their insulin secretion [

37]. Furthermore, during long-term fasting, SIRT1 promotes energy production by facilitating fat oxidation while minimizing gluconeogenesis during shorter fasting periods, conserving energy stores [

37]. SIRT1 also upregulates glucose uptake in response to obestatin, a 23-amino acid peptide hormone derived from the pre-pro-ghrelin transcript, primarily secreted by the stomach mucosa, in murine 3T3-L1 pre-adipocyte cells [

38].

SIRT1 plays a critical role in protecting against diabetes-induced vascular cell senescence and matrix calcification by enhancing DNA repair mechanisms in diabetic vascular smooth muscle cells [

2,

5,

39]. The miRNA-34a, which induces senescence and promotes vascular calcification, has been found to suppress SIRT1 expression and its anti-aging effects in mouse blood vessels [

40,

41]. The antidiabetic drug omarigliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, stimulates SIRT1 expression and enhances its antioxidant activity, offering potential benefits in preventing atherosclerotic changes [

42]. Overall, SIRT1 is regarded as a promising antidiabetic agent due to its beneficial effects on glucose homeostasis.

Low vitamin D3 levels are linked to cardiovascular and cognitive pathologies, as well as certain cancers [

43,

44]. In the elderly, reduced cholecalciferol production in the epidermis impairs calcium absorption and increases the risk of osteoporosis [

45]. Supplementation with the active form of vitamin D3 has been shown to promote myogenic differentiation in C2C12 myoblast cells and prevent myotube atrophy by upregulating SIRT1 expression [

46]. Additionally, vitamin D3-induced SIRT1 expression significantly reduced senescent changes in human aortic endothelial cells exposed to the chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin [

47]. These findings suggest that vitamin D-activated SIRT1 expression may reduce the risk of various pathologies, including metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, immune disorders, and chronic kidney disease [

48].

SIRT1 also interacts with hormones such as irisin, a myokine produced by skeletal muscle fibers during intense exercise, and melatonin, secreted by the pineal gland. Both hormones are potent antioxidants and act as anti-aging agents that help prevent cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders [

6,

49,

50]. Irisin has been shown to reduce microvascular damage in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in rats by upregulating SIRT1 [

51]. Similarly, SIRT1 upregulation mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of melatonin in the aorta and heart of ovariectomized rats [

52], and it prevents vascular smooth muscle loss in a mouse model of thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection [

53].

SIRT1 regulates the activity of angiotensin II (AT-II), a hormone in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system that controls water and salt balance and blood pressure. Resveratrol, a natural SIRT1 activator, downregulates the AT-II type I receptor in vascular smooth muscle cells, thereby mitigating the hypertensive effects of AT-II [

54]. Another study demonstrated that resveratrol inhibited the pro-renin receptor-angiotensin-converting enzyme-AT-II axis in the aging mouse aorta through pathways involving SIRT1 upregulation [

55]. The prevention of pro-senescent changes induced by AT-II in rodent and human vascular smooth muscle cells by PNU-282987 (a selective agonist of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor) also depends on normal SIRT1 expression [

56]. Moreover, fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) has been shown to reduce hypertrophic, apoptotic, and fibrotic changes in mouse hearts induced by AT-II through SIRT1-dependent pathways, highlighting the importance of SIRT1 in cardiovascular health [

57].

Collectively, these findings illustrate the diverse roles of SIRT1 in regulating various hormonal pathways, from glucose metabolism to cardiovascular protection, and its potential as a therapeutic target in age-related diseases.

3. Natural Activators of SIRT1 and Their Use in the Prevention of Aging

3.1. Resveratrol

Resveratrol is a natural polyphenolic compound found in various plants such as grapes (mainly in red grapes and wines, where the more stable trans-resveratrol appears from 1.9 mg/L to 14.3 mg/L [

58]), mulberries, raspberries, blueberries, peanuts and many others, i.e., from 34 families, including at least 100 species, some used for centuries in Chinese and other traditional medicine [

59]. The amount of resveratrol in these numerous sources varies from 8.7 g/kg in the seeds of

Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. var.

papaveraceae (Andrews) Kerner to less than 1 mg/kg for roots of

Smilax scobinicaulis and

Caragana sinica, and seeds of

Vigna umbellata (Thunb.) Ohwi et Ohashi [

59]. Resveratrol exists in cis and trans isoforms, the latter being more stable and potent [

60]. Resveratrol is recognized as a potent activator of SIRT1 that has anticancer, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, antifungal, antimicrobial and gut microbiota protective, metabolic and non-metabolic disease-related effects and anti-aging effects, all of which are associated with the activation of sirtuins, primarily by SIRT1 [

60]. Resveratrol increases SIRT1 expression and activity in various organs, including the liver, adipose tissue, brain, and heart, thereby exerting protective effects against age-related diseases [

8]. Thus, activated SIRT1 signaling enhances the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT), further protecting cells from oxidative damage [

61].

Research has demonstrated that resveratrol can extend lifespan and delay the onset of age-related diseases in various model organisms, including yeast, worms, and flies [

62]. In rodent studies, resveratrol supplementation has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity, reduce adiposity, and enhance glucose metabolism, thereby mitigating the risk of age-related metabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes [

63]. Moreover, resveratrol’s neuroprotective effects, mediated through SIRT1 activation, have been associated with improved cognitive function and reduced neuronal damage in models of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases [

64].

Beyond its direct effects on SIRT1, resveratrol also modulates other signaling pathways involved in aging, such as the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway. AMPK activation, in conjunction with SIRT1, promotes autophagy, a critical process for the removal of damaged cellular components, thereby contributing to cellular rejuvenation and longevity [

65]. Resveratrol’s ability to simultaneously activate SIRT1 and AMPK underscores its potential as a comprehensive anti-aging agent.

Resveratrol is generally recognized as safe for humans but overdoses could turn its effect from antioxidant and protective to prooxidant and harmful [

66]. The mechanism of this change is still not fully clarified but it may be related to oxidative stress, which results from preceding reductive stress and impaired signalling due to ROS depletion [

6]. Thus, like many other nutritional supplements with a positive effect on the life span of many species, resveratrol exerts a hormesis effect (hormetic dose-response relationship) with negative consequences on human health, mainly in cardiovascular, immune and digestive systems, on tumour and non-tumour cells [

67]. Additionally, long-term treatment with resveratrol (0.01 mM for 60 days) has a detrimental effect on a rat thyroid cell line due to inhibition of the expression of thyroid-restricted genes for thyroid peroxidase, thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor, and thyroglobulin, preceded by down-regulation of genes for transcription factors Foxe1, Nkx2-1 and Pax-8, which regulates the expression of the thyroid-specific proteins [

68]. This antithyroid influence is manifested as goitrogenic effect if 25 mg/kg resveratrol is administered intraperitoneally in rats for the same period of 60 days [

68]. Finally, high doses of trans-resveratrol inhibit cytochrome P450 isoenzymes and thus the hepatic elimination of drugs, which along with other food-drug and drug-drug interactions could attenuate the effect of therapy [

66,

69].

3.2. Curcumin as a SIRT1-Activating Anti-Aging Compound

Curcumin, a hydrophobic polyphenolic compound derived from the rhizome of

Curcuma longa (turmeric), has been widely studied for its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer effects [

70,

71,

72,

73,

74]. Curcumin, through its pleiotropic effects, has been shown to be an activator of SIRT1, thereby influencing the aging process and alleviating age-related diseases [

6,

70,

73]. Curcumin also promotes SIRT1-induced autophagy, a process essential for clearing damaged cellular components and maintaining cellular homeostasis, which declines with age [

70,

75]. Through this mechanism, curcumin contributes for reduced accumulation of damaged proteins and organelles, potentially preventing neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s [

75].

Despite its promising effects, the clinical application of curcumin is often limited by its low bioavailability. Innovative delivery methods, such as nanocarriers and liposomes, are being developed to enhance its absorption and efficacy as a SIRT1 activator in aging prevention strategies [

5,

76].

3.3. Paeonol as a SIRT1-Activating Anti-Aging Compound

Paeonol, a phenolic compound extracted from the bark of

Paeonia suffruticosa (Moutan Cortex) Andr., has been widely recognized for its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuroprotective properties [

77,

78]. Paeonol has been shown to bind directly to SIRT1, enhancing its activity and promoting the SIRT1/p53/telomeric repeat-binding factor 2 (TRF2) pathway, which protects against vascular senescence and endothelial dysfunction, both of which are major contributors to cardiovascular aging [

79]. Studies also suggest that paeonol’s SIRT1-mediated effects extend to neuroprotection, as it reduces neuroinflammation and enhances cognitive function [

78,

80].

3.4. Buyang Huanwu Decoction (BHD) as a SIRT1-Activating Anti-Aging Prescription

Buyang Huanwu Decoction (BHD), a traditional Chinese medicine formula composed of seven herbs, increases SIRT1 expression in the brain, which promotes neuronal survival, reduces apoptosis, and enhances neurogenesis in models of cerebral ischemia [

81,

82]. BHD is used for stroke recovery and promoting overall health [

83]. By activating SIRT1, BHD also enhances the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), leading to improved vascularization and blood flow in the brain, which is crucial for preventing neurodegenerative diseases [

84]. Additionally, BHD-induced SIRT1 activation modulates autophagy pathways, promoting the clearance of damaged proteins and reducing oxidative stress, thereby protecting against cellular aging [

82]. Furthermore, BHD has demonstrated anti-ischemic effect due to caveolin-1 dependent mitochondrial quality control [

85]. These findings suggest that BHD may serve as a promising natural prescription for aging prevention and management.

3.5. Delivery of SIRT1 Activators

The therapeutic potential of SIRT1 activators, such as resveratrol, curcumin, and paeonol, is often limited by their poor bioavailability, rapid metabolism, and low permeability across biological barriers, including the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [

75]. This limits their use for the prevention of aging and stress of the CNS, and as potential anti-Alzheimer’s and anti-Parkinson’s diseases drugs [

75,

86]. To overcome these challenges, various delivery strategies have been developed to enhance their stability, absorption, and targeted delivery. Nanotechnology-based approaches, such as covalent bonding to nanoparticles, incorporation in liposomes, and lipid-based carriers, have shown promise in improving the bioavailability and targeted delivery of SIRT1 activators [

75,

87,

88]. For example, curcumin-loaded nanostructures improve oral bioavailability and enable effective crossing of the BBB, enhancing neuroprotective effects in models of neurodegenerative diseases [

75,

86]. Similarly, resveratrol encapsulated in nanoparticles and liposomes has demonstrated increased stability and brain-targeted delivery, effectively enhancing its antioxidant and anti-aging properties [

75,

87].

3.6. Nose-to-Brain Delivery of SIRT1 Activators

Of particular interest against age-related neurodegeneration and diseases is the nose-to-brain drug delivery i.e., application of substances and structures on the surface of human nasal olfactory mucosa for further translocation towards different brain areas [

88]. The use of drug carriers ensures drug delivery into the brain stem (basolateral area of pons) using anterograde trans- or paracellular transport via the supporting (sustentacular) cells of the nasal mucosa and the neurons of

N. trigeminus (trigeminal pathway) [

89,

90]. Endocytosis followed by intraneural transport through olfactory sensory neurons or as an alternative alongside olfactory neurons (olfactory pathway) towards the olfactory bulb and further to the cerebrospinal fluid is another mechanism [

87,

88] to bypass the BBB [

89]. The nasal mucosa allows the rapid absorption of drugs, facilitating their transport to the brain regions with minimal systemic exposure [

89,

92]. Promising results were obtained despite the numerous challenges, such as rapid mucociliary clearance in the nasal cavity and pharyngeal drainage, low precision of drug dosing, interindividual variability in the anatomy of the nasal cavities, limited administration volume, low absorption rate of high molecular weight substances and difficulties in targeting specific brain areas, as well as limited applications in allergy or colds [

88,

91].

The neuroprotective effects of resveratrol have been extensively studied for nose-to-brain delivery. When administered intranasally, resveratrol demonstrates enhanced brain targeting, improved bioavailability, and increased SIRT1 activation in neuronal tissues. Studies have shown that resveratrol delivered via the nasal route reduces oxidative stress, modulates inflammatory pathways, and preserves cognitive function in animal models of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases [

93]. Similarly, intranasal curcumin delivery via SIRT1 supports neurogenesis and reducing amyloid-beta accumulation in the brain [

90].

3.7. SIRT1 Activators with Improved Oral Bioavailability

Improving the oral bioavailability of SIRT1 activators is crucial for maximizing their therapeutic potential in aging and age-related diseases. For example, curcumin-loaded nanostructures and modifications such as micelles, liposomes, emulsions, solid lipid and biopolymers nanoparticles improve the oral bioavailability of curcumin, enhance its stability, and improve its therapeutic efficacy against oxidative stress and inflammation [

94,

95]. Similarly, resveratrol encapsulated in nanostructured lipid carriers has demonstrated enhanced intestinal absorption and systemic circulation, thereby amplifying its anti-aging effects [

96].

4. Conclusions

This review highlights the important role of SIRT1 in regulating hormonal pathways, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid, -adrenal, -gonadal, and -liver axes, involved in aging and age-related diseases. Natural SIRT1 activators such as resveratrol, curcumin, paeonol, and Buyang Huanwu Decoction demonstrate promising anti-aging effects through their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties. These compounds enhance SIRT1 activity, contributing to improved mitochondrial function, reduced oxidative stress, and inflammation, optimized metabolism and homeostasis, which are essential for promoting longevity and preventing age-associated disorders.

However, the clinical application of these SIRT1 activators is often limited by challenges related to low bioavailability and poor permeability across the BBB and other biological membranes. Innovative delivery strategies, such as nose-to-brain methods and nanotechnology-based formulations for oral use, are being developed to overcome these barriers, potentially enhancing their therapeutic efficacy. Future research should focus on refining these delivery systems and exploring combination therapies to fully realize the benefits of SIRT1 activators in aging prevention and management. Overall, SIRT1-targeted therapies offer a promising approach for extending health span and improving outcomes in age-related diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.G. and M.M.; validation, M.K.-M., M.M., I.S., H.G.; writing-original draft preparation, M.K.M., I.S., B.P., P.Z., M.M. and H.G.; writing-review and editing, M.K.-M., I.S., H.G.; visualization, I.S.; project administration, H.G.; funding acquisition, P.Z. and B.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union - NextGenerationEU through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project number BG-RRP-2.004-0007-C01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barrett E. J. Organization of Endocrine Control. In: Medical Physiology. Eds. Boron, W.F. and Boupaep, E.L. 2012, Elsevier Publisher, Philadelphia, pp. 1011-1073.

- Kida, Y., Goligorsky, M.S. Sirtuins, Cell Senescence, and Vascular Aging. Can J Cardiol. 2016, 32(5), 634-641. [CrossRef]

- Das, J.K., Banskota, N., Candia, J., Griswold, M.E., Orenduff, M., de Cabo, R., Corcoran, D.L., Das, S.K., De, S., Huffman, K.M., Kraus, V.B,. Kraus, W.E., Martin, C.K., Racette, S.B., Redman, L.M., Schilling, B., Belsky, D.W., Ferrucci, L. Calorie restriction modulates the transcription of genes related to stress response and longevity in human muscle: The CALERIE study. Aging Cell. 2023, 22(12):e13963. [CrossRef]

- Imai, S., Guarente, L. NAD+ and sirtuins in aging and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2014, 24(8):464-71. [CrossRef]

- Sazdova, I.; Hadzi-Petrushev, N.; Keremidarska-Markova, M.; Stojchevski, R.; Sopi, R.; Shileiko, S.; Mitrokhin, V.; Gagov, H.; Avtanski, D.; Lubomirov, L.T.; Mladenov, M. SIRT-associated attenuation of cellular senescence in vascular wall. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2024, 220:111943. [CrossRef]

- Mladenov, M.; Lubomirov L., Grisk O, Avtanski D, Mitrokhin V, Sazdova I, Keremidarska-Markova M, Danailova Y, Nikolaev G, Konakchieva R, Gagov, H. Oxidative Stress, Reductive Stress and Antioxidants in Vascular Pathogenesis and Aging. Antioxidants 2023, 12(5), 1126. doi.org/10.3390/antiox12051126.

- Satoh, A., Stein, L., Imai, S. The role of mammalian sirtuins in the regulation of metabolism, aging, and longevity. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2011, 206, 125-162. [CrossRef]

- Baur, J. A., Sinclair, D. A. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: The in vivo evidence. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2006, 5(6), 493-506. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.N., Lansdown, A., Witczak, J., Khan, R., Rees, A., Dayan, C.M., Okosieme, O. Age-related variation in thyroid function - a narrative review highlighting important implications for research and clinical practice. Thyroid Res 2023 16(1):7. Erratum in: Thyroid Res. 2023 May 30;16(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13044-023-00163-7. [CrossRef]

- Cappola, A.R., Auchus, R.J., El-Hajj Fuleihan, G., Handelsman, D.J., Kalyani, R.R., McClung, M., Stuenkel, C.A., Thorner, M.O., Verbalis, J.G. Hormones and Aging: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023, 108(8), 1835-1874. [CrossRef]

- Akieda-Asai, S., Zaima, N., Ikegami, K., Kahyo, T., Yao, I., Hatanaka, T., et al. SIRT1 Regulates thyroid-stimulating hormone release by enhancing PIP5Kgamma activity through deacetylation of specific lysine residues in mammals. PloS ONE 2010,, 5(7):e11755. [CrossRef]

- Boily, G., Seifert, E.L., Bevilacqua, L., He, X.H., Sabourin, G., Estey, C., Moffat, C., Crawford, S., Saliba, S., Jardine, K., Xuan, J., Evans, M., Harper, M.E., McBurney, M.W. SIRT1 regulates energy metabolism and response to caloric restriction in mice. PLoS One 2008, 3(3):e1759. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Takahashi, Y. The Essential Role of SIRT1 in Hypothalamic-Pituitary Axis. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9:605. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.M., Vale, W.W. The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006, 8(4):383-95. [CrossRef]

- Toorie, A.M., Cyr, N.E., Steger, J.S., Beckman, R., Farah, G., Nillni, E.A. The nutrient and energy sensor SIRT1 regulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis by altering the production of the prohormone convertase 2 (PC2) essential in the maturation of Corticotropin-releasing Hormone (CRH) from its prohormone in male rats. J Biol Chem. 2016, 291:5844–59. [CrossRef]

- Li, D., Dammer, E.B., Sewer, M.B. Resveratrol stimulates cortisol biosynthesis by activating SIRT-dependent deacetylation of P450scc. Endocrinology. 2012, 153(7):3258-68. [CrossRef]

- Connelly, P.J., Casey, H., Montezano, A.C. et al. Sex steroids receptors, hypertension, and vascular aging. J Hum Hypertens. 2022, 36:120–125. doi: 10.1038/s41371-021-00576-7.

- Ashraf, M.S.; Vongpatanasin, W. Estrogen and hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2006, 8(5), 368-76. [CrossRef]

- Novella, S., Heras, M., Hermenegildo, C., Dantas, A.P. Effects of estrogen on vascular inflammation: a matter of timing. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012, 32(8):2035-42. [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Gómez, X., Novella, S., Pérez-Monzó, I., Garabito, M., Dantas, A.P., Segarra, G., Hermenegildo, C., Medina, P. Decreased bioavailability of nitric oxide in aorta from ovariectomized senescent mice. Role of cyclooxygenase. Exp Gerontol. 2016, 76:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Eleawa, S.M., Sakr, H.F., Hussein, A.M., Assiri, A.S., Bayoumy, N.M., Alkhateeb, M. Effect of testosterone replacement therapy on cardiac performance and oxidative stress in orchidectomized rats. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2013, 209(2):136-47. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.L., Blair, H., Cao, J., Yuen, T., Latif, R., Guo, L., Tourkova, I.L., Li, J., Davies, T.F., Sun, L., Bian, Z., Rosen, C., Zallone, A., New, M.I., Zaidi, M. Blocking antibody to the β-subunit of FSH prevents bone loss by inhibiting bone resorption and stimulating bone synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012, 109(36):14574-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu P, Ji Y, Yuen T, Rendina-Ruedy E, DeMambro VE, et al. Blocking FSH induces thermogenic adipose tissue and reduces body fat. Nature. 2017, 546(7656), 107-112. [CrossRef]

- Samargandy S, Matthews KA, Brooks MM, Barinas-Mitchell E, Magnani JW, Thurston RC, El Khoudary SR. Trajectories of Blood Pressure in Midlife Women: Does Menopause Matter? Circ Res. 2022, 130(3), 312-322. [CrossRef]

- Patel SM, Ratcliffe SJ, Reilly MP, Weinstein R, Bhasin S, Blackman MR, Cauley JA, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Robbins J, Fried LP, Cappola AR. Higher serum testosterone concentration in older women is associated with insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009, 94(12), 4776-4784. [CrossRef]

- Kolthur-Seetharam U, Teerds K, de Rooij DG, Wendling O, McBurney M, Sassone-Corsi P, Davidson I. The histone deacetylase SIRT1 controls male fertility in mice through regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary gonadotropin signaling. Biol Reprod. 2009, 80(2), 384-91. [CrossRef]

- Khawar MB, Liu C, Gao F, Gao H, Liu W, Han T, Wang L, Li G, Jiang H, Li W. SIRT1 regulates testosterone biosynthesis in Leydig cells via modulating autophagy. Protein Cell. 2021, 12(1), 67-75. [CrossRef]

- Tao Z, Cheng Z. Hormonal regulation of metabolism-recent lessons learned from insulin and estrogen. Clin Sci (Lond). 2023, 137(6):415-434. [CrossRef]

- Lu C, Zhao H, Liu Y, Yang Z, Yao H, Liu T, Gou T, Wang L, Zhang J, Tian Y, Yang Y, Zhang H. Novel Role of the SIRT1 in Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases. Int J Biol Sci. 2023, 19(2), 484-501. [CrossRef]

- Ieda N, Assadullah, Minabe S, Ikegami K, Watanabe Y, Sugimoto Y, Sugimoto A, Kawai N, Ishii H, Inoue N, Uenoyama Y, Tsukamura H. GnRH(1-5), a metabolite of gonadotropin-releasing hormone, enhances luteinizing hormone release via activation of kisspeptin neurons in female rats. Endocr J. 2020, 67(4), 409-418. [CrossRef]

- Matuszewska J, Nowacka-Woszuk J, Radziejewska A, Grzęda E, Pruszyńska-Oszmałek E, Dylewski Ł, Chmurzyńska A, Sliwowska JH. Maternal cafeteria diet influences kisspeptin (Kiss1), kisspeptin receptor(Gpr54), and sirtuin (SIRT1) genes, hormonal and metabolic profiles, and reproductive functions in rat offspring in a sex-specific manner†. Biol Reprod. 2023, 109(5), 654-668. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki Y, Ikeda Y, Miyauchi T, Uchikado Y, Akasaki Y, Ohishi M. Estrogen-SIRT1 Axis Plays a Pivotal Role in Protecting Arteries Against Menopause-Induced Senescence and Atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2020, 27(1):47-59. [CrossRef]

- Merriam GR, Hersch EC. Growth hormone (GH)-releasing hormone and GH secretagogues in normal aging: Fountain of Youth or Pool of Tantalus? Clin Interv Aging 2008, 3(1):121–129.

- Clasey JL, Weltman A, Patrie J, Weltman JY, Pezzoli S, Bouchard C, Thorner MO, Hartman ML. Abdominal visceral fat and fasting insulin are important predictors of 24-hour GH release independent of age, gender, and other physiological factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001, 86(8), 3845-3852. [CrossRef]

- Cohen DE, Supinski AM, Bonkowski MS, Donmez G, Guarente LP. Neuronal SIRT1 regulates endocrine and behavioral responses to calorie restriction. Genes Dev. 2009, 23(24), 2812-2817. [CrossRef]

- Chia CW, Egan JM, Ferrucci L. Age-Related Changes in Glucose Metabolism, Hyperglycemia, and Cardiovascular Risk. Circ Res. 2018, 123(7), 886-904. [CrossRef]

- Quiñones M, Al-Massadi O, Fernø J, Nogueiras R. Cross-talk between SIRT1 and endocrine factors: effects on energy homeostasis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014, 397(1-2):42-50. [CrossRef]

- Granata R, Gallo D, Luque RM, Baragli A, Scarlatti F, Grande C, Gesmundo I, Córdoba-Chacón J, Bergandi L, Settanni F, et al. Obestatin regulates adipocyte function and protects against diet-induced insulin resistance and inflammation. FASEB J. 2012, 26(8), 3393-411. [CrossRef]

- Bartoli-Leonard, F, Wilkinson FL, Schiro A, Serracino Inglott F, Alexander MY, Weston R. Loss of SIRT1 in diabetes accelerates DNA damage-induced vascular calcification. Cardiovasc Res. 2021, 117(3), 836-849.

- Menghini R, Stöhr R, Federici M. MicroRNAs in vascular aging and atherosclerosis. Ageing Res Rev. 2014, 17:68-78. [CrossRef]

- Raucci A, Macrì F, Castiglione S, Badi I, Vinci MC, Zuccolo E. MicroRNA-34a: the bad guy in age-related vascular diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021, 78(23), 7355-7378. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Wang H, Wu K, Zhang L. Omarigliptin protects against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by ameliorating oxidative stress and inflammation. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2021, 35(12), e22914. [CrossRef]

- Brøndum-Jacobsen P, Nordestgaard BG, Schnohr P, Benn M. 25-hydroxyvitamin D and symptomatic ischemic stroke: an original study and meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2013, 73(1), 38-47. [CrossRef]

- Gandini S, Boniol M, Haukka J, Byrnes G, Cox B, Sneyd MJ, Mullie P, Autier P. Meta-analysis of observational studies of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and colorectal, breast and prostate cancer and colorectal adenoma. Int J Cancer. 2011, 128(6), 1414-24. [CrossRef]

- Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, Brun J, Crouzet B, Arnaud S, Delmas PD, Meunier PJ. Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in elderly women. N Engl J Med. 1992, 327(23), 1637-1642. [CrossRef]

- Talib NF, Zhu Z, Kim KS. Vitamin D3 Exerts Beneficial Effects on C2C12 Myotubes through Activation of the Vitamin D Receptor (VDR)/Sirtuins (SIRT)1/3 Axis. Nutrients. 2023;15(22):4714. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Zhou L, Du B, Liu Y, Xing J, Guo S, Li L, Chen H. Protection against Doxorubicin-Related Cardiotoxicity by Jaceosidin Involves the SIRT1 Signaling Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021, 2021, 9984330. [CrossRef]

- Nemeth Z, Patonai A, Simon-Szabó L, Takács I. Interplay of Vitamin D and SIRT1 in Tissue-Specific Metabolism—Potential Roles in Prevention and Treatment of Non-Communicable Diseases Including Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(7):6154. doi.org/10.3390/ijms24076154.

- Martín Giménez VM, de Las Heras N, Lahera V, Tresguerres JAF, Reiter RJ, Manucha W. Melatonin as an Anti-Aging Therapy for Age-Related Cardiovascular and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 888292. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Wang M, Wang Y. Irisin: A Potentially Fresh Insight into the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Vascular Aging. Aging Dis. 2023. https://doi.org/10.14336/AD.2023.1112.

- Li X, Jamal M, Guo P, Jin Z, Zheng F, Song X, Zhan J, Wu H. Irisin alleviates pulmonary epithelial barrier dysfunction in sepsis-induced acute lung injury via activation of AMPK/SIRT1 pathways. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019, 118, 109363. [CrossRef]

- Arabacı Tamer S, Altınoluk T, Emran M, Korkmaz S, Yüksel RG, Baykal Z, Dur ZS, Levent HN, Ural MA, Yüksel M, Çevik Ö, Ercan F, Yıldırım A, Yeğen BÇ. Melatonin Alleviates Ovariectomy-Induced Cardiovascular Inflammation in Sedentary or Exercised Rats by Upregulating SIRT1. Inflammation 2022, 45(6), 2202-2222. [CrossRef]

- Xia L, Sun C, Zhu H, Zhai M, Zhang L, Jiang L, Hou P, Li J, Li K, Liu Z, Li B, Wang X, Yi W, Liang H, Jin Z, Yang J, Yi D, Liu J, Yu S, Duan W. Melatonin protects against thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection through SIRT1-dependent regulation of oxidative stress and vascular smooth muscle cell loss. J Pineal Res. 2020, 69(1), e12661. [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki R, Ichiki T, Hashimoto T, Inanaga K, Imayama I, Sadoshima J, Sunagawa K. SIRT1, a longevity gene, downregulates angiotensin II type 1 receptor expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008, 28(7), 1263-1269. [CrossRef]

- Kim EN, Kim MY, Lim JH, Kim Y, Shin SJ, Park CW, Kim YS, Chang YS, Yoon HE, Choi BS. The protective effect of resveratrol on vascular aging by modulation of the renin-angiotensin system. Atherosclerosis 2018, 270, 123-131. [CrossRef]

- Li DJ, Huang F, Ni M, Fu H, Zhang LS, Shen FM. α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Relieves Angiotensin II-Induced Senescence in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells by Raising Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide-Dependent SIRT1 Activity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016, 36(8), 1566-1576. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Jamal M, Guo P, Jin Z, Zheng F, Song X, Zhan J, Wu H. Irisin alleviates pulmonary epithelial barrier dysfunction in sepsis-induced acute lung injury via activation of AMPK/SIRT1 pathways. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019, 118, 109363. [CrossRef]

- Stervbo, U., Vang O., Bonnesen C. A review of the content of the putative chemopreventive phytoalexin resveratrol in red wine. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 449-457. [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Liu, J. Resveratrol: a review of plant sources, synthesis, stability, modification and food application. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100(4), 1392-1404. [CrossRef]

- Szymkowiak I, Kucinska M, Murias M. Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea—Resveratrol, Sulfotransferases and Sulfatases—A Long and Turbulent Journey from Intestinal Absorption to Target Cells. Molecules 2023, 28(8), 3297. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y, Takeuchi H, Sonobe Y, Jin S, Wang Y, Horiuchi H, Parajuli B, Kawanokuchi J, Mizuno T, Suzumura A. Sirtuin 1 attenuates oxidative stress via upregulation of superoxide dismutase 2 and catalase in astrocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 2014, 269(1-2), 38-43. [CrossRef]

- Bhullar KS, Hubbard BP. Lifespan and healthspan extension by resveratrol. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1852(6), 1209-1218. [CrossRef]

- Ghavidel F, Hashemy SI, Aliari M, Rajabian A, Tabrizi MH, Atkin SL, Jamialahmadi T, Hosseini H, Sahebkar A. The Effects of Resveratrol Supplementation on the Metabolism of Lipids in Metabolic Disorders. Curr Med Chem. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, Jamieson HA, Lerin C, Kalra A, Prabhu VV, Allard JS, Lopez-Lluch G, Lewis K, Pistell PJ, Poosala S, Becker KG, Boss O, Gwinn D, Wang M, Ramaswamy S, Fishbein KW, Spencer RG, Lakatta EG, Le Couteur D, Shaw RJ, Navas P, Puigserver P, Ingram DK, de Cabo R, Sinclair DA. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature 2006, 444(7117), 337-342. [CrossRef]

- Morselli E, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Criollo A, Maiuri MC, Tavernarakis N, Madeo F, Kroemer G. Autophagy mediates pharmacological lifespan extension by spermidine and resveratrol. Aging (Albany NY) 2009, 1(12), 961-970. [CrossRef]

- Shaito A, Posadino AM, Younes N, Hasan H, Halabi S, Alhababi D, Al-Mohannadi A, Abdel-Rahman WM, Eid AH, Nasrallah GK, Pintus G. Potential Adverse Effects of Resveratrol: A Literature Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21(6), 2084. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese EJ, Nascarella M, Pressman P, Hayes AW, Dhawan G, Kapoor R, Calabrese V, Agathokleous E. Hormesis determines lifespan. Aging Res Rev. 2024, 94:102181. [CrossRef]

- Giuliani C, Iezzi M, Ciolli L, Hysi A, Bucci I, Di Santo S, Rossi C, Zucchelli M, Napolitano G. Resveratrol has anti-thyroid effects both in vitro and in vivo. Food Chem Toxicol. 2017, 107(Pt A), 237-247. [CrossRef]

- Ji S-B, Park S-Y, Bae S, Seo H-J, Kim S-E, Lee G-M, Wu Z, Liu K-H. Comprehensive Investigation of Stereoselective Food Drug Interaction Potential of Resveratrol on Nine P450 and Six UGT Isoforms in Human Liver Microsomes. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13(9):1419.

- Aggarwal BB, Harikumar KB. Potential therapeutic effects of curcumin, the anti-inflammatory agent, against neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases. Int. J Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41(1):40-59. [CrossRef]

- Mladenov, M.; Bogdanov, J.; Bogdanov, B.; Hadzi-Petrushev, N.; Kamkin, A.; Stojchevski, R.; Avtanski, D. Efficacy of the monocarbonyl curcumin analog C66 in the reduction of diabetes-associated cardiovascular and kidney complications. Mol Med. 2022; 28(1), 129. [CrossRef]

- Hadzi-Petrushev, N.; Bogdanov, J.; Krajoska, J.; Ilievska, J.; Bogdanova-Popov, B.; Gjorgievska, E.; Mitrokhin, V.; Sopi, R.; Gagov, H.; Kamkin, A., Mladenov, M. Comparative study of the antioxidant properties of monocarbonyl curcumin analogues C66 and B2BrBC in isoproteranol induced cardiac damage. Life Sci. 2018, 197, 10-18. [CrossRef]

- Stamenkovska, M.; Hadzi-Petrushev, N.; Nikodinovski, A.; Gagov, H.; Atanasova-Panchevska, N.; Mitrokhin, V.; Kamkin, A.; Mladenov, M. Application of curcumine and its derivatives in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases: a review. Int. J. Food Properties 2021, 24(1), 1510-1528.

- Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA, Aggarwal BB. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol Pharm. 2007, 4(6), 807-818. [CrossRef]

- Phukan BC, Roy R, Gahatraj I, Bhattacharya P, Borah A. Therapeutic considerations of bioactive compounds in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: Dissecting the molecular pathways. Phytother Res. 2023, 37(12):5657-5699. [CrossRef]

- Josifovska S, Panov S, Hadzi-Petrushev N, Mitrokhin V, Kamkin A, Stojchevski R, Avtanski D, Mladenov M. Positive Tetrahydrocurcumin-Associated Brain-Related Metabolomic Implications. Molecules 2023, 28(9), 3734. [CrossRef]

- Jin X, Wang J, Xia ZM, Shang CH, Chao QL, Liu YR, Fan HY, Chen DQ, Qiu F, Zhao F. Anti-inflammatory and Anti-oxidative Activities of Paeonol and Its Metabolites Through Blocking MAPK/ERK/p38 Signaling Pathway. Inflammation 2016, 39(1), 434-446. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Li DC, Liu LF. Paeonol: pharmacological effects and mechanisms of action. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 72:413-421. [CrossRef]

- Zhou M, Ma X, Gao M, Wu H, Liu Y, Shi X, Dai M. Paeonol Attenuates Atherosclerosis by Inhibiting Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Senescence via SIRT1/P53/TRF2 Signaling Pathway. Molecules 2024, 29(1), 261. [CrossRef]

- Tseng YT, Hsu YY, Shih YT, Lo YC. Paeonol attenuates microglia-mediated inflammation and oxidative stress-induced neurotoxicity in rat primary microglia and cortical neurons. Shock. 2012, 37(3), 312-318. [CrossRef]

- Long J, Gu C, Zhang Q, Liu J, Huang J, Li Y, Zhang Y, Li R, Ahmed W, Zhang J, Khan AA, Cai H, Hu Y, Chen L. Extracellular vesicles from medicated plasma of Buyang Huanwu decoction-preconditioned neural stem cells accelerate neurological recovery following ischemic stroke. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11:1096329. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Peng D, Zhang SJ, Zhang Y, Wang Q, Guan L. Buyang Huanwu Decoction promotes neurogenesis via sirtuin 1/autophagy pathway in a cerebral ischemia model. Mol Med Rep. 2021, 24(5), 791. [CrossRef]

- Mu Q, Liu P, Hu X, Gao H, Zheng X, Huang H. Neuroprotective effects of Buyang Huanwu decoction on cerebral ischemia-induced neuronal damage. Neural Regen Res. 2014, 9(17):1621-7. [CrossRef]

- Zheng XW, Shan CS, Xu QQ, Wang Y, Shi YH, Wang Y, Zheng GQ. Buyang Huanwu Decoction Targets SIRT1/VEGF Pathway to Promote Angiogenesis After Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 4, 12, 911. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Chen B, Yi J, Tian F, Liu Y, Ouyang Y, Yuan C, Liu B. Buyang Huanwu Decoction alleviates cerebral ischemic injury through modulating caveolin-1-mediated mitochondrial quality control. Front Pharmacol. 2023, 14:1137609. [CrossRef]

- Komorowska J, Wątroba M, Szukiewicz D. Review of beneficial effects of resveratrol in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease. Adv Med Sci. 2020, 65(2), 415-423. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Kiarasi F. Therapeutic effects of resveratrol on epigenetic mechanisms in age-related diseases: A comprehensive review. Phytother Res. 2024, 38(5), 2347-2360. [CrossRef]

- Gänger S, Schindowski K. Tailoring Formulations for Intranasal Nose-to-Brain Delivery: A Review on Architecture, Physico-Chemical Characteristics and Mucociliary Clearance of the Nasal Olfactory Mucosa. Pharmaceutics. 2018, 10(3), 116. [CrossRef]

- Crowe, T.P.; Greenlee MHW, Kanthasamy AG, Hsu WH. Mechanism of intranasal drug delivery directly to the brain. Life Sci. 2018, 195, 44-52. [CrossRef]

- Koo J, Lim C, Oh KT. Recent Advances in Intranasal Administration for Brain-Targeting Delivery: A Comprehensive Review of Lipid-Based Nanoparticles and Stimuli-Responsive Gel Formulations. Int J Nanomedicine. 2024, 19, 1767-1807. [CrossRef]

- Djupesland, P. G. (2013). Nasal drug delivery devices: Characteristics and performance in a clinical perspective. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2013, 3(1), 42-62. [CrossRef]

- Crowe, T.P.; Hsu, W.H. Evaluation of Recent Intranasal Drug Delivery Systems to the Central Nervous System. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 629. [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorso, A.; Gigliobianco, M.R.; Pellitteri, R.; Santonocito, D.; Carbone, C.; Di Martino, P.; Puglisi, G.; Musumeci, T. Optimization of Curcumin Nanocrystals as Promising Strategy for Nose-to-Brain Delivery Application. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 476. [CrossRef]

- Campisi, A.; Sposito, G.; Pellitteri, R.; Santonocito, D.; Bisicchia, J.; Raciti, G.; Russo, C.; Nardiello, P.; Pignatello, R.; Casamenti, F.; et al. Effect of Unloaded and Curcumin-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles on Tissue Transglutaminase Isoforms Expression Levels in an Experimental Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1863. [CrossRef]

- Sanidad KZ, Sukamtoh E, Xiao H, McClements DJ, Zhang G. Curcumin: Recent Advances in the Development of Strategies to Improve Oral Bioavailability. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2019, 10, 597-617. [CrossRef]

- Deepti Pandita, Sandeep Kumar, Neelam Poonia, Viney Lather, Solid lipid nanoparticles enhance oral bioavailability of resveratrol, a natural polyphenol. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 1165-1174. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).