Submitted:

07 October 2024

Posted:

08 October 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

| Follow-up (years) |

Type of stroke |

Inc or Mor |

OR/RR (95% CI) |

25(OH)D comparison (ng/mL) |

Reference |

| -- | 1.41 (0.64‒3.13) | (Guo, 2017*) [9] | |||

| -- | 1.19 (0.79‒1.79) | (Leu Agelii, 2017*) [10] | |||

| 1 | inc | 0.42 (0.14‒1.28) | >10 vs. <10 | (Zittermann, 2016) [11] | |

| 1.3 | inc | 0.56 (0.38‒0.84) | >30 vs. <15 | (Anderson, 2010) [12] | |

| 3.1 | inc | 0.54 (0.34‒0.85) | >30 vs. <20 | (Judd, 2016) [13] | |

| 4 | inc | 0.33 (0.15‒0.73) | >30 vs. <10 | (Drechsler, 2010) [14] | |

| 5 | inc | 0.71 (0.40‒1.25) | >20 vs. <20 | (Bolland, 2010) [15] | |

| 6.8 | inc + mor | 0.91 (0.81‒1.02) | per +10 | (Perna, 2013) [16] | |

| 6.8 | inc + mor | 0.76 (0.55‒1.05) | <12 vs. >20 | ||

| 7.6 | inc | 0.60 (0.59‒1.09) | Q4 (27 median) vs. Q1 (12 median) |

(Kuhn, 2013) [17] | |

| 7.6 | inc | 0.65 (0.49‒0.95) | >20 vs. <10 | ||

| 8.0 | inc | 0.93 (0.46‒1.85) | >20 vs. <20 | (Welles, 2014) [18] | |

| 9.3 | I | inc | 0.81 (0.70‒0.94) | >20 vs. <10 | (Afzal, 2017) [19] |

| 10 | inc + mor | 1.00 (0.51‒1.94) | High vs. low tertile | (Marniemi, 2005) [20] | |

| 10 | 0.88 (0.49‒1.61) | Middle vs. low tertile | |||

| 10 | inc | 1.13 (0.80‒1.59) | Fourth vs. first quartile | (Skaaby, 2013[21] | |

| 10.3 | All | inc | 0.56 (0.36‒0.86) | Lowest vs. highest quintile | (Leung, 2017[22] |

| 10.3 | I | 0.55 (0.35‒0.86) | Lowest vs. highest quintile | ||

| 10.6 | inc | 0.91 (0.75‒1.11) | One 25(OH)D SD increase | (Berghout, 2019) [23] | |

| 14.1 | All, W | mor | 0.47 (0.22‒0.99) | >15 vs. <15 | (Michos, 2012) [24] |

| 14.1 | All, B | mor | 1.07 (0.56‒2.04) | >15 vs. <15 | |

| 14.1 | mor | 0.57 (0.31‒1.06) | >15 vs. <15 | ||

| 16 | inc or mor | 0.60 (0.39‒0.91) | >20 vs. <20 | (Schierbeck, 2012) [25] | |

| 19.3 | 0.66 (0.49‒0.89) | >440 vs. <110 IU/day vitamin D |

(Sheerah, 2018*) [26] | ||

| 20 | inc | 0.75 (0.58‒0.94) | >31 vs. <17 | (Schneider, 2015) [27] | |

| 34 | 0.82 (0.68‒0.99) | >4 vs. <1.1 µg/day | (Kojima, 2012*) [28] |

| Country | Patient characteristics | Mean Age (± SD) or range (years) |

BMI (± SD) (kg/m2) |

M, F (%) |

Type of Stroke |

NS | NC | Reference |

| Germany | Left ventricular assist device implants | 62 (37‒81) | 23 ± 3 | 100, 0 | All | 25 | (Zittermann, 2016) [11] | |

| 57 (49‒66) | 26 ± 5 | 85, 15 | 129 | |||||

| USA | Community hospital | 55 ± 21 | NA | 25, 75 | All | 208 | 25,818 | (Anderson, 2010) [12] |

| USA | B and W community-dwelling | I | 536 | 1069 | (Judd, 2016) [13] | |||

| Germany | Diabetic haemodialysis | 66 ± 8 | 60, 40 | All | 89 | 1019 | (Drechsler, 2010) [14] | |

| New Zealand | Healthy community-dwelling | 74 ± 4 | NA | 0, 100 | All | 59 | 1412 | (Bolland, 2010) [15] |

| Germany | Population-based | 65% 50‒65; 35% 65‒74 | 27 ± 5 | 41, 59 | All | 353 | 7356 | (Perna, 2013) [16] |

| Germany | Population-based | 51 | NA | 42, 58 | All | 471 | 1661 | (Kuhn, 2013) [17] |

| USA | Stable CVD disease | 66 ± 11 | 29 | 81, 19 | All | 49 | 897 | (Welles, 2014) [18] |

| Denmark | General population | 58 (48‒68) | 26 ± 3 | 48, 52 | I | 960 | ~115,000 | (Afzal, 2017) [19] |

| Finland | Population-based | 65-99 | NA | 48, 52 | All | 70 | 685 | (Marniemi, 2005) [20] |

| Denmark | General population | 49 (41-73) | 26 | 50, 50 | All | 316 | 8830 | (Skaaby, 2013[21] |

| Hong Kong | Osteoporosis study, Chinese | 63 ± 10 | 37, 63 | All | 244 | 3214 | (Leung, 2017[22] | |

| 63 ± 10 | 37, 63 | I | 205 | 3253 | ||||

| The Netherlands | Population-based | 65 ± 10 | 27 ± 4 | 43, 57 | All | 735 | 8603 | (Berghout, 2019) [23] |

| USA | Population-based, W* | 73 (SE, 1) | 27 (SE, 0.5) | 35, 65 | All | 116 | 4885 | (Michos, 2012) [24] |

| USA | Population-based, B* | 68 (SE, 2) | 28 (SE, 0.8) | 34, 66 | All | 60 | 2920 | (Michos, 2012) [24] |

| Denmark | Osteoporosis study | 50 ± 2 | 25 ± 5 | 0, 100 | All | 89 | 1924 | (Schierbeck, 2012) [25] |

| USA | Population-based | 57 | NA | 43, 57 | All | 804 | 11,354 | (Schneider, 2015) [27] |

| Follow-up (years) |

RR (95% CI) | 25(OH)D comparison (ng/mL) |

Reference |

| 1.0 | 1.85 (1.25‒2.75) | <9 vs. >9 | (de Metrio, 2015) [31] |

| 1.0 | 1.20 (0.72‒2.00) | <12 vs. >12 | (Beska, 2019) [32] |

| 1.25 | 7.24 (0.99‒53.50) | <30 vs. >30 | (Siasos, 2013) [33] |

| 1.5 | 1.61 (1.15‒2.27) | <7.3 vs. >7.3 | (Ng, 2013) [34] |

| 2.2 | 1.30 (1.04‒1.64) | <20 vs. >20 | (Aleksova, 2020) [35] |

| 2.7 | 1.32 (1.07‒1.63) | <12.7; 12.7-21.59; ≥21.6 | (Verdoia, 2021) [36] |

| 5 | 1.2 (0.7‒2.2) | <20 vs. >20 | (Bolland, 2010) [15] |

| 5.8 | 1.84 (1.36‒2.50) | (Gerling, 2016) [37] | |

| 6.7 | 1.36 (0.88‒2.12) | (Yu, 2018) [38] | |

| 7.0 | 1.27 (0.92‒1.75) | (Naesgaard, 2015) [39] | |

| 7.6 | 1.62 (1.11‒2.36) | <15 vs. >15 | (Wang, 2008) [40] |

| 7.7 | 1.77 (1.47‒2.13) | (Lerchbaum, 2012) [41] | |

| 8.0 | 1.11 (0.85‒1.44) | >20 vs. <20 | (Welles, 2014) [18] |

| 8.1 | 0.83 (0.37‒1.86) | Quartiles | (Grandi, 2010) [42] |

| 10 | (Giovannucci, | ||

| 10 | (Marniemi | ||

| 11.9 | 1.94 (1.66‒2.27) | (Degerud, 2018) [43] |

| Country | Patient characteristics |

Mean Age (± SD) or range (years) |

BMI (± SD) (kg/m2) |

M, F (%) |

Type of event | NMCDE | NC | Reference |

| Italy | Acute coronary syndrome | 67 ± 12 | 27 ± 4 | 72, 28 | MACE | 125 | 689 | (de Metrio, 2015) [31] |

| UK | After non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome | 81 ± 5 | 27 ± 5 | 62, 38 | MACE | 76 | 224 | (Beska, 2019) [32] |

| UK | Acute myocardial infarction | 66 ± 13 | NA | 72, 28 | non-fatal MACE | 224 | 1035 | (Ng, 2013) [34] |

| Italy | Myocardial infarction | 67 ± 12 | 27 ± 4 | 71, 29 | all-cause mortality, angina/MI, HF | 391 | 690 | (Aleksova, 2020) [35] |

| Italy | CAD undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention | 68 ± 11 | 28 ± 5 | 73, 27 | MACE | 174 | 531 | (Verdoia, 2021) [36] |

| New Zealand | Healthy community-dwelling | 74 ± 4 | NA | 0, 100 | MI | 52 | 1419 | (Bolland, 2010) [15] |

| Death | (Gerling, 2016) [37] | |||||||

| Death | (Yu, 2018) [38] | |||||||

| Death | (Naesgaard, 2015) [39] | |||||||

| Incident CVD | (Wang, 2008) [40] | |||||||

| Death | (Lerchbaum, 2012) [41] | |||||||

| USA | Stable CVD disease | 66 ± 11 | 29 | 81, 19 | CVD events | 49 | 897 | (Welles, 2014) [18] |

| CVD events | 148 | 977 | (Grandi, 2010) [42] | |||||

| (Giovannucci, | ||||||||

| Death | (Marniemi, 2005) | |||||||

| Death | (Degerud, 2018) [43] |

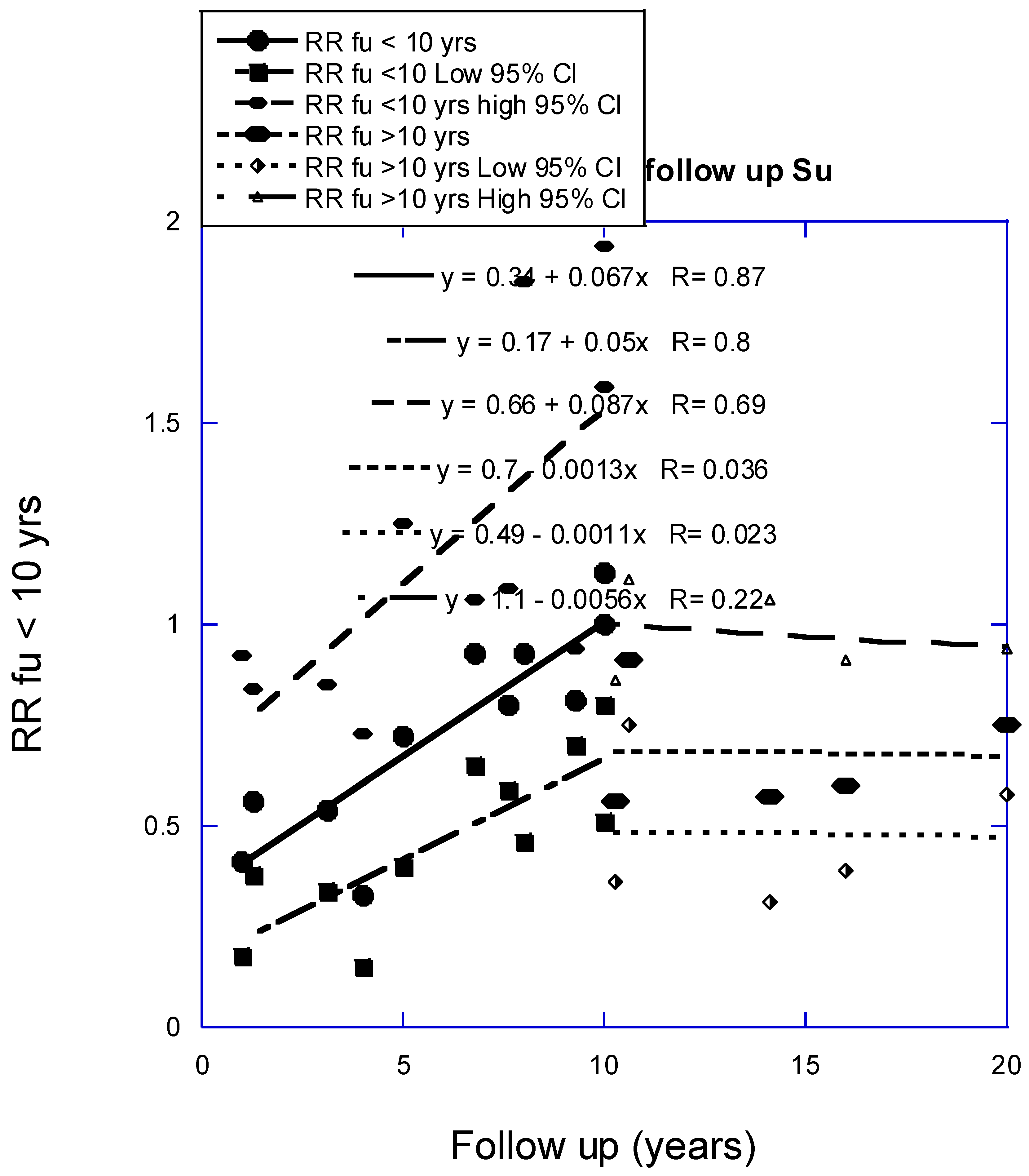

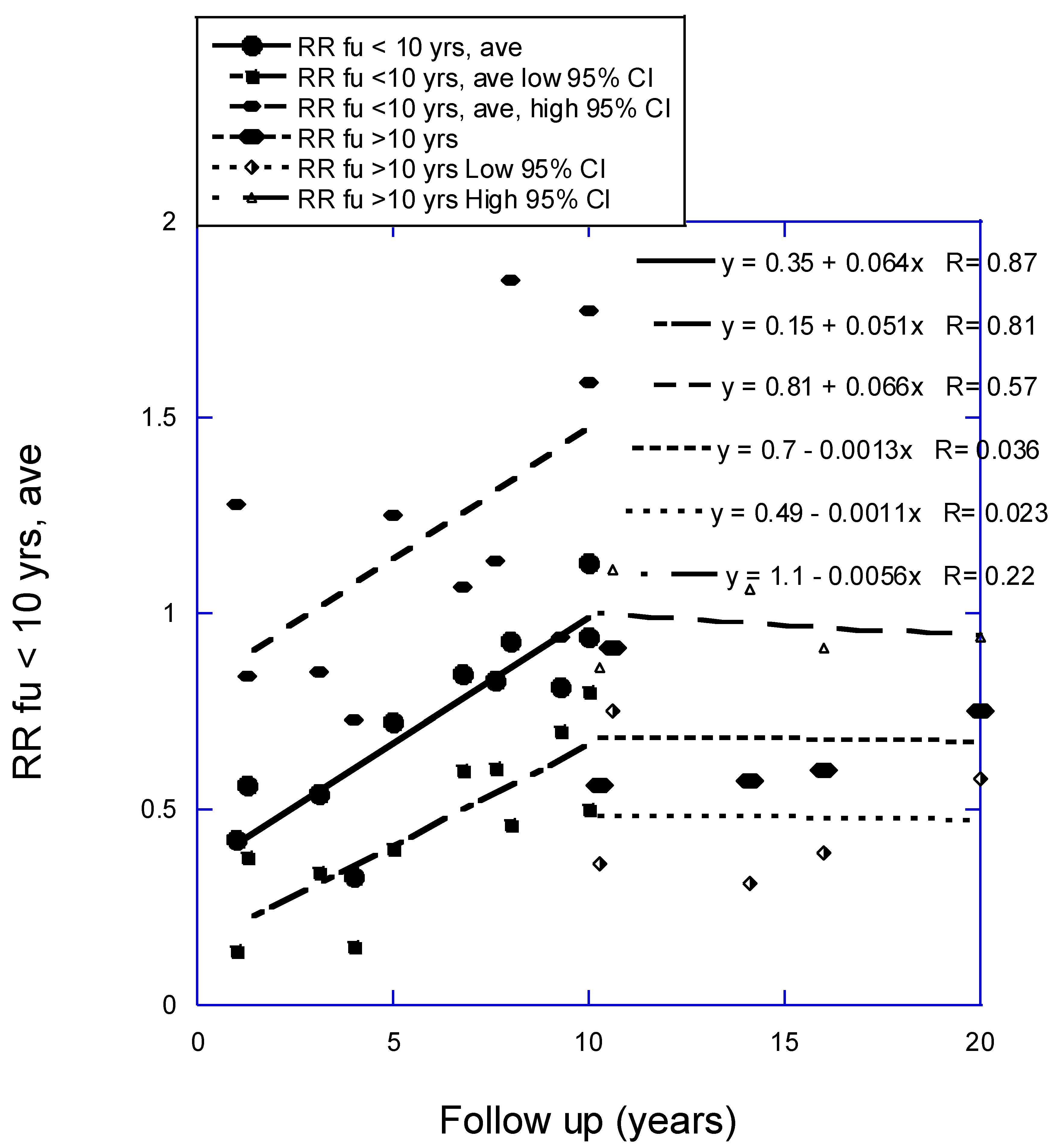

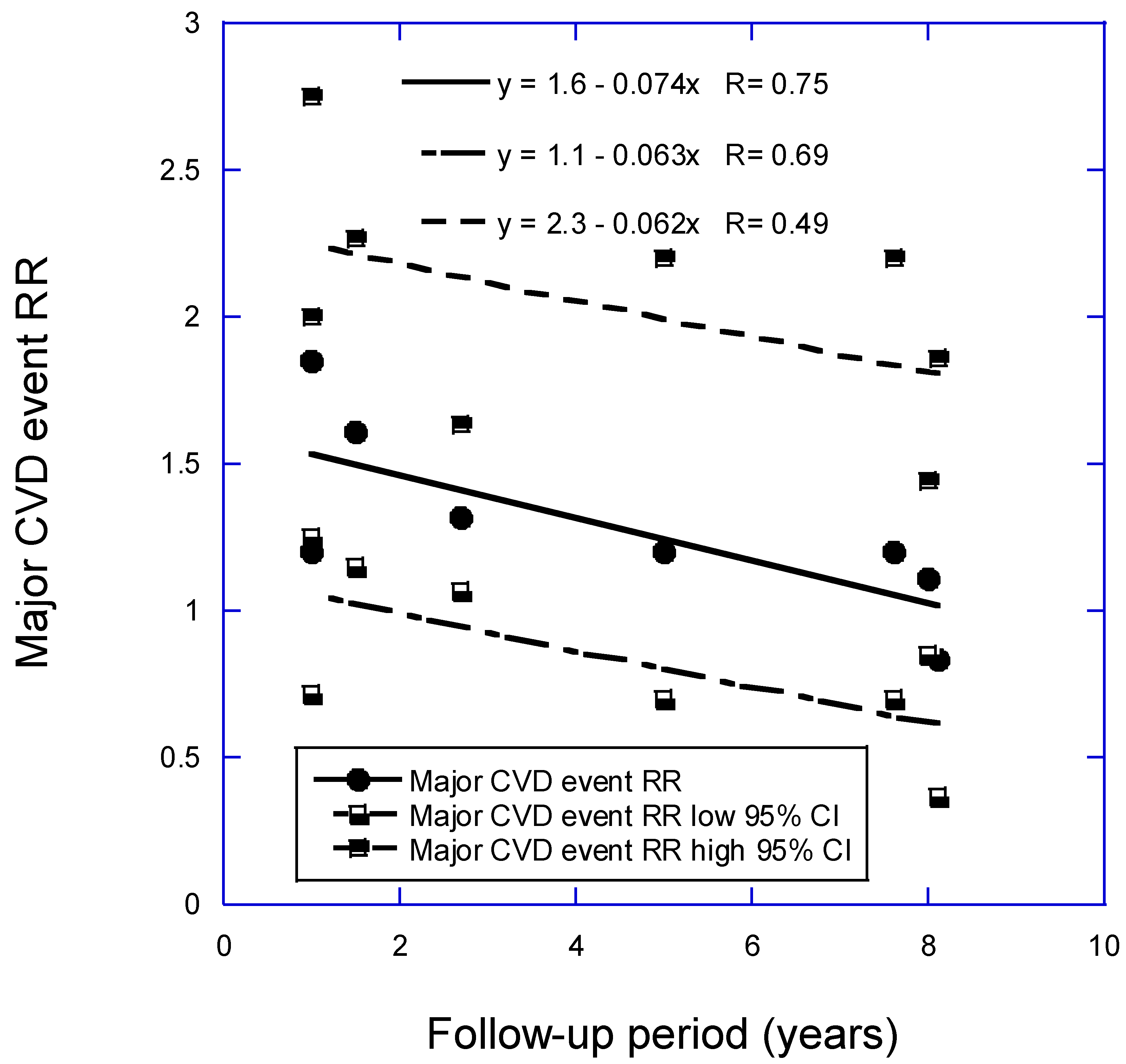

3. Results

4. Discussion

| Topic | Reason |

| Vitamin D mechanisms | (Yarlagadda, 2020) [64] |

| Post-stroke, 25(OH)D at time of stroke | (Marek, 2022) [65] |

| Risk of recurrent stoke | (Vergatti, 2023) [66] |

| Review, association, mechanisms, 25(OH)D, oral intake | (Cui, 2024) [67] |

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clarke, R.; Shipley, M.; Lewington, S.; Youngman, L.; Collins, R.; Marmot, M.; Peto, R. Underestimation of risk associations due to regression dilution in long-term follow-up of prospective studies. Am J Epidemiol 1999, 150, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, W.B. Effect of interval between serum draw and follow-up period on relative risk of cancer incidence with respect to 25-hydroxyvitamin D level: Implications for meta-analyses and setting vitamin D guidelines. Dermatoendocrinol 2011, 3, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B. Effect of follow-up time on the relation between prediagnostic serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and all-cause mortality rate. Dermatoendocrinol 2012, 4, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.L.; Zoltick, E.S.; Weinstein, S.J.; Fedirko, V.; Wang, M.; Cook, N.R.; Eliassen, A.H.; Zeleniuch-Jacquotte, A.; Agnoli, C.; Albanes, D. , et al. Circulating Vitamin D and Colorectal Cancer Risk: An International Pooling Project of 17 Cohorts. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019, 111, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, A.; Grant, W.B. Vitamin D and Cancer: An Historical Overview of the Epidemiology and Mechanisms. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.X.; Wang, H.R.; Meng, W.; Hu, Y.Z.; Sun, H.M.; Feng, Y.X.; Jia, J.J. Association of Vitamin D Levels with Risk of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. J Alzheimers Dis 2024, 98, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Jin, B.; Xia, H.; Zhao, K. Association between Vitamin D and Risk of Stroke: A PRISMA-Compliant Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur Neurol 2021, 84, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Zhao, C.; Li, J.; Li, Y. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the linkage between low vitamin D and the risk as well as the prognosis of stroke. Brain Behav 2024, 14, e3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Cockcroft, J.R.; Elwood, P.C.; Pickering, J.E.; Lovegrove, J.A.; Givens, D.I. Vitamin D intake and risk of CVD and all-cause mortality: evidence from the Caerphilly Prospective Cohort Study. Public Health Nutr 2017, 20, 2744–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu Agelii, M.; Lehtinen-Jacks, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Sundh, V.; Bjorkelund, C.; Lissner, L. Low vitamin D status in relation to cardiovascular disease and mortality in Swedish women - Effect of extended follow-up. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2017, 27, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zittermann, A.; Morshuis, M.; Kuhn, J.; Pilz, S.; Ernst, J.B.; Oezpeker, C.; Dreier, J.; Knabbe, C.; Gummert, J.F.; Milting, H. Vitamin D metabolites and fibroblast growth factor-23 in patients with left ventricular assist device implants: association with stroke and mortality risk. Eur J Nutr 2016, 55, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.L.; May, H.T.; Horne, B.D.; Bair, T.L.; Hall, N.L.; Carlquist, J.F.; Lappe, D.L.; Muhlestein, J.B.; Intermountain Heart Collaborative Study, G. Relation of vitamin D deficiency to cardiovascular risk factors, disease status, and incident events in a general healthcare population. Am J Cardiol 2010, 106, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judd, S.E.; Morgan, C.J.; Panwar, B.; Howard, V.J.; Wadley, V.G.; Jenny, N.S.; Kissela, B.M.; Gutierrez, O.M. Vitamin D deficiency and incident stroke risk in community-living black and white adults. Int J Stroke 2016, 11, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsler, C.; Pilz, S.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B.; Verduijn, M.; Tomaschitz, A.; Krane, V.; Espe, K.; Dekker, F.; Brandenburg, V.; Marz, W. , et al. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with sudden cardiac death, combined cardiovascular events, and mortality in haemodialysis patients. Eur Heart J 2010, 31, 2253–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolland, M.J.; Bacon, C.J.; Horne, A.M.; Mason, B.H.; Ames, R.W.; Wang, T.K.; Grey, A.B.; Gamble, G.D.; Reid, I.R. Vitamin D insufficiency and health outcomes over 5 y in older women. Am J Clin Nutr 2010, 91, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perna, L.; Schottker, B.; Holleczek, B.; Brenner, H. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and incidence of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events: a prospective study with repeated measurements. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013, 98, 4908–4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.; Kaaks, R.; Teucher, B.; Hirche, F.; Dierkes, J.; Weikert, C.; Katzke, V.; Boeing, H.; Stangl, G.I.; Buijsse, B. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and its genetic determinants in relation to incident myocardial infarction and stroke in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC)-Germany study. PLoS One 2013, 8, e69080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welles, C.C.; Whooley, M.A.; Karumanchi, S.A.; Hod, T.; Thadhani, R.; Berg, A.H.; Ix, J.H.; Mukamal, K.J. Vitamin D deficiency and cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease: data from the Heart and Soul Study. Am J Epidemiol 2014, 179, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, S.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Vitamin D, Hypertension, and Ischemic Stroke in 116 655 Individuals From the General Population: A Genetic Study. Hypertension 2017, 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marniemi, J.; Alanen, E.; Impivaara, O.; Seppanen, R.; Hakala, P.; Rajala, T.; Ronnemaa, T. Dietary and serum vitamins and minerals as predictors of myocardial infarction and stroke in elderly subjects. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2005, 15, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaaby, T.; Husemoen, L.L.; Pisinger, C.; Jorgensen, T.; Thuesen, B.H.; Fenger, M.; Linneberg, A. Vitamin D status and incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a general population study. Endocrine 2013, 43, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, R.Y.; Han, Y.; Sing, C.W.; Cheung, B.M.; Wong, I.C.; Tan, K.C.; Kung, A.W.; Cheung, C.L. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and the risk of stroke in Hong Kong Chinese. Thromb Haemost 2017, 117, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghout, B.P.; Fani, L.; Heshmatollah, A.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Ikram, M.A.; Zillikens, M.C.; Ikram, M.K. Vitamin D Status and Risk of Stroke: The Rotterdam Study. Stroke 2019, 50, 2293–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michos, E.D.; Reis, J.P.; Post, W.S.; Lutsey, P.L.; Gottesman, R.F.; Mosley, T.H.; Sharrett, A.R.; Melamed, M.L. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D deficiency is associated with fatal stroke among whites but not blacks: The NHANES-III linked mortality files. Nutrition 2012, 28, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierbeck, L.L.; Rejnmark, L.; Tofteng, C.L.; Stilgren, L.; Eiken, P.; Mosekilde, L.; Kober, L.; Jensen, J.E. Vitamin D deficiency in postmenopausal, healthy women predicts increased cardiovascular events: a 16-year follow-up study. Eur J Endocrinol 2012, 167, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheerah, H.A.; Eshak, E.S.; Cui, R.; Imano, H.; Iso, H.; Tamakoshi, A.; Japan Collaborative Cohort Study, G. Relationship Between Dietary Vitamin D and Deaths From Stroke and Coronary Heart Disease: The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. Stroke 2018, 49, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.L.; Lutsey, P.L.; Selvin, E.; Mosley, T.H.; Sharrett, A.R.; Carson, K.A.; Post, W.S.; Pankow, J.S.; Folsom, A.R.; Gottesman, R.F. , et al. Vitamin D, vitamin D binding protein gene polymorphisms, race and risk of incident stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Eur J Neurol 2015, 22, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, G.; Bell, C.; Abbott, R.D.; Launer, L.; Chen, R.; Motonaga, H.; Ross, G.W.; Curb, J.D.; Masaki, K. Low dietary vitamin D predicts 34-year incident stroke: the Honolulu Heart Program. Stroke 2012, 43, 2163–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, N.C.; Breitling, L.P.; Brenner, H. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Prev Med 2010, 51, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Jie, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Fan, Y. Predictive value of 25-hydroxyvitamin D level in patients with coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 984487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Metrio, M.; Milazzo, V.; Rubino, M.; Cabiati, A.; Moltrasio, M.; Marana, I.; Campodonico, J.; Cosentino, N.; Veglia, F.; Bonomi, A. , et al. Vitamin D plasma levels and in-hospital and 1-year outcomes in acute coronary syndromes: a prospective study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015, 94, e857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beska, B.; Chan, D.; Gu, S.; Qiu, W.; Mossop, H.; Neely, D.; Kunadian, V. The association between vitamin D status and clinical events in high-risk older patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome undergoing invasive management. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0217476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siasos, G.; Tousoulis, D.; Oikonomou, E.; Maniatis, K.; Kioufis, S.; Kokkou, E.; Miliou, A.; Zaromitidou, M.; Kassi, E.; Stefanadis, C. Vitamin D serum levels are associated with cardiovascular outcome in coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol 2013, 168, 4445–4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.L.; Sandhu, J.K.; Squire, I.B.; Davies, J.E.; Jones, D.J. Vitamin D and prognosis in acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2013, 168, 2341–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksova, A.; Ferro, F.; Gagno, G.; Padoan, L.; Saro, R.; Santon, D.; Stenner, E.; Barbati, G.; Cappelletto, C.; Rossi, M. , et al. Diabetes Mellitus and Vitamin D Deficiency:Comparable Effect on Survival and a DeadlyAssociation after a Myocardial Infarction. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdoia, M.; Nardin, M.; Rolla, R.; Negro, F.; Gioscia, R.; Afifeh, A.M.S.; Viglione, F.; Suryapranata, H.; Marcolongo, M.; De Luca, G. , et al. Prognostic impact of Vitamin D deficiency in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur J Intern Med 2021, 83, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerling, M.E.; James, M.T.; Wilton, S.B.; Naugler, C.; Southern, D.A.; Galbraith, P.D.; Knudtson, M.; de Koning, L. Serum Total 25-OH Vitamin D Adds Little Prognostic Value in Patients Undergoing Coronary Catheterization. J Am Heart Assoc 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Xue, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, G.; Ling, W. Serum Bioavailable and Free 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels, but Not Its Total Level, Are Associated With the Risk of Mortality in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. Circ Res 2018, 123, 996–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naesgaard, P.A.; Ponitz, V.; Aarsetoey, H.; Brugger-Andersen, T.; Grundt, H.; Harris, W.S.; Staines, H.; Nilsen, D.W. Prognostic utility of vitamin D in acute coronary syndrome patients in coastal Norway. Dis Markers 2015, 2015, 283178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.J.; Pencina, M.J.; Booth, S.L.; Jacques, P.F.; Ingelsson, E.; Lanier, K.; Benjamin, E.J.; D'Agostino, R.B.; Wolf, M.; Vasan, R.S. Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2008, 117, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerchbaum, E.; Pilz, S.; Boehm, B.O.; Grammer, T.B.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B.; Marz, W. Combination of low free testosterone and low vitamin D predicts mortality in older men referred for coronary angiography. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012, 77, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandi, N.C.; Breitling, L.P.; Vossen, C.Y.; Hahmann, H.; Wusten, B.; Marz, W.; Rothenbacher, D.; Brenner, H. Serum vitamin D and risk of secondary cardiovascular disease events in patients with stable coronary heart disease. Am Heart J 2010, 159, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degerud, E.; Nygard, O.; de Vogel, S.; Hoff, R.; Svingen, G.F.T.; Pedersen, E.R.; Nilsen, D.W.T.; Nordrehaug, J.E.; Midttun, O.; Ueland, P.M. , et al. Plasma 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Mortality in Patients With Suspected Stable Angina Pectoris. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018, 103, 1161–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Fu, K.; Xue, W.; Teng, W.; Tian, L. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D level, vitamin D intake, and risk of stroke: A dose-response meta-analysis. Clin Nutr 2020, 39, 2025–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, M.; Tehrani, F.R.; Simbar, M.; Bidhendi Yarandi, R.; Minooee, S.; Hollis, B.W.; Hosseinpanah, F. Effectiveness of Prenatal Vitamin D Deficiency Screening and Treatment Program: A Stratified Randomized Field Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018, 103, 2936–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Hu, J.; Huo, X.; Miao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, F. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on cognitive function and blood Abeta-related biomarkers in older adults with Alzheimer's disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2019, 90, 1347–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamilian, H.; Amirani, E.; Milajerdi, A.; Kolahdooz, F.; Mirzaei, H.; Zaroudi, M.; Ghaderi, A.; Asemi, Z. The effects of vitamin D supplementation on mental health, and biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in patients with psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2019, 94, 109651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellekkatt, F.; Menon, V.; Rajappa, M.; Sahoo, J. Effect of adjunctive single dose parenteral Vitamin D supplementation in major depressive disorder with concurrent vitamin D deficiency: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res 2020, 129, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, A.; Rasouli-Azad, M.; Farhadi, M.H.; Mirhosseini, N.; Motmaen, M.; Pishyareh, E.; Omidi, A.; Asemi, Z. Exploring the Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Cognitive Functions and Mental Health Status in Subjects Under Methadone Maintenance Treatment. J Addict Med 2020, 14, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, M.; Fiedler, N.; Pop, L.C.; Schneider, S.J.; Schlussel, Y.; Sukumar, D.; Hao, L.; Shapses, S.A. Three Doses of Vitamin D and Cognitive Outcomes in Older Women: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2020, 75, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalcraft, J.R.; Cardinal, L.M.; Wechsler, P.J.; Hollis, B.W.; Gerow, K.G.; Alexander, B.M.; Keith, J.F.; Larson-Meyer, D.E. Vitamin D Synthesis Following a Single Bout of Sun Exposure in Older and Younger Men and Women. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooney, M.R.; Harnack, L.; Michos, E.D.; Ogilvie, R.P.; Sempos, C.T.; Lutsey, P.L. Trends in Use of High-Dose Vitamin D Supplements Exceeding 1000 or 4000 International Units Daily, 1999-2014. JAMA 2017, 317, 2448–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhabeeb, H.; Kord-Varkaneh, H.; Tan, S.C.; Gaman, M.A.; Otayf, B.Y.; Qadri, A.A.; Alomar, O.; Salem, H.; Al-Badawi, I.A.; Abu-Zaid, A. The influence of omega-3 supplementation on vitamin D levels in humans: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 3116–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelsen, O. The relationship between ultraviolet radiation exposure and vitamin D status. Nutrients 2010, 2, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, F.L.; Steur, M.; Allen, N.E.; Appleby, P.N.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J. Plasma concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in meat eaters, fish eaters, vegetarians and vegans: results from the EPIC-Oxford study. Public Health Nutr 2011, 14, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorde, R.; Sneve, M.; Emaus, N.; Figenschau, Y.; Grimnes, G. Cross-sectional and longitudinal relation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and body mass index: the Tromso study. Eur J Nutr 2010, 49, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorde, R.; Sneve, M.; Hutchinson, M.; Emaus, N.; Figenschau, Y.; Grimnes, G. Tracking of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels during 14 years in a population-based study and during 12 months in an intervention study. Am J Epidemiol 2010, 171, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maghfour, J.; Boothby-Shoemaker, W.; Lim, H.W. Evaluating the USA population's interest in sunscreen: a Google Trends analysis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2022, 47, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, L.T.N.; Tan, V.V.; Moon, J.Y.; Chae, M.; Park, D.; Lee, Y.-C. Recent Trends of Sunscreen Cosmetic: An Update Review. Cosmetics 2019, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hypponen, E.; Power, C. Hypovitaminosis D in British adults at age 45 y: nationwide cohort study of dietary and lifestyle predictors. Am J Clin Nutr 2007, 85, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, M.H.; Bi, C.; Garber, C.C.; Kaufman, H.W.; Liu, D.; Caston-Balderrama, A.; Zhang, K.; Clarke, N.; Xie, M.; Reitz, R.E. , et al. Temporal relationship between vitamin D status and parathyroid hormone in the United States. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0118108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Lopez, F.R.; Chedraui, P.; Pilz, S. Vitamin D supplementation after the menopause. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2020, 11, 2042018820931291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikonen, H.; Lumme, J.; Seppala, J.; Pesonen, P.; Piltonen, T.; Jarvelin, M.R.; Herzig, K.H.; Miettunen, J.; Niinimaki, M.; Palaniswamy, S. , et al. The determinants and longitudinal changes in vitamin D status in middle-age: a Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 study. Eur J Nutr 2021, 60, 4541–4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarlagadda, K.; Ma, N.; Dore, S. Vitamin D and Stroke: Effects on Incidence, Severity, and Outcome and the Potential Benefits of Supplementation. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, K.; Cichon, N.; Saluk-Bijak, J.; Bijak, M.; Miller, E. The Role of Vitamin D in Stroke Prevention and the Effects of Its Supplementation for Post-Stroke Rehabilitation: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergatti, A.; Abate, V.; Zarrella, A.F.; Manganelli, F.; Tozza, S.; Iodice, R.; De Filippo, G.; D'Elia, L.; Strazzullo, P.; Rendina, D. 25-Hydroxy-Vitamin D and Risk of Recurrent Stroke: A Dose Response Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, P.; Hou, H.; Song, B.; Xia, Z.; Xu, Y. Vitamin D and ischemic stroke - Association, mechanisms, and therapeutics. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 96, 102244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudy, M.; Krakowski, G.; Ghahramani, M.; Ruzieh, M.; Foy, A.J. Vitamin D supplementation, cardiac events and stroke: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2020, 28, 100537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P. Guidelines for optimizing design and analysis of clinical studies of nutrient effects. Nutr Rev 2014, 72, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Boucher, B.J.; Bhattoa, H.P.; Lahore, H. Why vitamin D clinical trials should be based on 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2018, 177, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, S.; Trummer, C.; Theiler-Schwetz, V.; Grubler, M.R.; Verheyen, N.D.; Odler, B.; Karras, S.N.; Zittermann, A.; Marz, W. Critical Appraisal of Large Vitamin D Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, W.B.; Boucher, B.J.; Al Anouti, F.; Pilz, S. Comparing the Evidence from Observational Studies and Randomized Controlled Trials for Nonskeletal Health Effects of Vitamin D. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participants | Duration (weeks) |

Condition | Intervention | Outcomes | Reference |

| Meta-analysis of nine clinical trials, China and Iran | 8‒52 | Mental health | 50,000 IU per week or two weeks or higher single dose | Beck Depression Inventory, weighted mean difference, -3.9 (95% CI, -5.2‒ -2.7) | [47] |

| 46 patients, India Baseline 25(OH)D: N/A |

12 | Major depressive disorder | usual treatment or usual treatment plus 3 million IU vitamin D | Significantly greater improvement in depression score with vitamin D than placebo; also quality of life. | [48] |

| 64 patients under methadone maintenance treatment, Iran. Baseline 25(OH)D: 14 ± 4 ng/mL |

24 | Cognitive function | 50,000 IU or placebo every two weeks | Vitamin D treatment resulted in significant improvement in Iowa Gambling Task, Verbal Fluency Test, Reverse Digit Span, and visual working memory. | [49] |

| 42 women, USA mean age 58 ± 6 years, BMI, 30.0 ± 3.5 kg/m2, Baseline 25(OH)D: 23 ± 6 ng/mL |

52 | Cognitive outcome | 600, 2000, or 4000 IU/d vitamin D3 | 2000 IU/d group had improved visual and working memory and learning; the 4000 IU/d group had slower attention reaction time | [50] |

| Reason | Reference | |

| Decline with age due to reduced production from solar UVB | [51] | |

| Increased awareness of the overall benefits of vitamin D | [52] | |

| Change amount of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation | [53] | |

| Change geographic location | [54] | |

| Retire from work | ||

| Change in diet with reduced meat, fish consumption | [55] | |

| Change in body mass | [56] | |

| Change in physical activity | [57] | |

| Change in use of sunscreen/sunblock, clothing when in sunlight | [58] | |

| Increased use of sunscreen in cosmetics | [59] | |

| Season | [60,61] | |

| Increased vitamin D supplementation after menopause | [62] | |

| Vitamin D fortification of food instituted country wide | [63] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).