1. Introduction

The introduction sThe concept of a green city is increasingly equated with urban sustainability. A green city is an incarnation of a sustainable city[

1]. It integrates the notions of nature in a city, which refers to UGSs (Urban Green Spaces) [

2], as well as the notion of spatial analysis in urban ecology [

3,

4]. However, the notion of climate change also encompasses methods of analysis such as resilience and vulnerability[

5]. As a result, urban sustainability becomes intrinsically linked to the sustainability of urban vegetation.

A sustainable city prioritizes the sustainable management of vegetation cover as a core element of its development. The distribution of vegetation is influenced by local land use patterns[

4,

6,

7], and is vegetation is influenced by local land use patterns [

4,

6,

7] and is also affected by demographic pressure [

8,

9]. Indeed, the urbanisation of the planet is occurring exponentially; the urban population at the global level has increased from 30% in 1950 to 54% in 2014, and from 56% in 2022, it is expected to reach 70% in 2050 [

10]. Urbanisation is more pronounced in southern countries, where it will increase from 18% in 1950 to 56% in 2030. Rapid urbanisation directly influences landscape structure and the distribution of green spaces[

11,

12], [particularly in southern countries, where anthropogenic pressures fragment UGSs to a greater extent, with a negative impact on biodiversity conservation, environmental quality, urban microclimates [

13,

14] and present and future climate resilience [

15,

16,

17].

In sub-Saharan Africa, the rapid growth of the urban population is driving the horizontal expansion of cities, resulting in significant changes to the urban landscape structure [

18]. These transformations are marked by the degradation, or even disappearance, of vegetation cover in favor of buildings that develop chaotically [

19,

20], Consequently, it is undeniable that future urban population growth will further strain urban green spaces (UGSs) [

15].This unregulated urban expansion contributes to the increasing fragmentation of UGSs, exacerbating the climate vulnerability of cities, which in turn is the source of the rise of heat islands and negatively impacts the well-being of urban populations [

21].

Like other West African countries, Togo has not been spared from the phenomenon of population growth. The urban population in Togo increased from 25.2% in 1981 [

22], to 37.4% in 2010 [

23], reaching 42.9% by 2022 [

24]. With its recent special status as an autonomous district, the capital Lomé alone accounts for more than 63% of the country's overall urbanisation rate and Kara is the country's second largest city. This significant demographic pressure has driven the horizontal expansion of built-up areas [

25], leading to a reduction in vegetation cover. Consequently, less attention has been given to the importance of incorporating green spaces into modern buildings.

This has led to the regression of UGSs, and an increase in climatic vulnerability. Moreover, the areas dedicated to reserves, which are made up of green spaces that are resilient to the effects of climate change, are increasingly being encroached upon by construction in Togolese cities, exacerbating issues like flooding [

26,

27].In response to these challenges and aware of the importance of UGSs in the process of urban sustainability, the Togolese government has dedicated two of its six prioritised ODD (ODD 11 and 15) to the conservation and enhancement of green spaces [

30] to achieve its NDP (National Development Plan)[

28] and the PNACC (Togo's National Plan for Adaptation to Climate Change)[

29]. Despite the scope of this theme, studies devoted to the issue of UGSs and their impacts on climate vulnerability in Togolese cities remain insufficient. Indeed, previous studies have addressed the spatiotemporal dynamism of Togolese cities without specifically discussing UGSs [

31]. Other studies have investigated vegetation dynamics in different parts of the country but not in urban areas [

32,

33,

34]; some, such as those by Polorigni et al [

27,

35], have highlighted the crucial importance of UGSs in mitigating global warming in Lomé. Other studies have addressed the issues of vulnerability and resilience to climate change, but only at the regional scale [

36].

For urban planning to align with current realities and effectively address the challenges of sustainable cities while taking into account the indispensable nature of vegetation and its impact on climate vulnerability, decision-makers need to be provided with updated, predictive information on the subject. This study is framed within that context, with the overall objective of assessing the dynamics of urban sprawl in Lomé and Kara in relation to the conservation of UGSs while modelling the degree of their vulnerability to climate change. Specifically, the objectives are (i) to assess the land use dynamics of the sprawl of the cities of Lomé and Kara in relation to the conservation of vegetation cover in 1988, 2000, 2012 and 2022 and (ii) to model the degree of vulnerability of urban land in Lomé and Kara to climate change for in 2022, with projections for the years 2060 and 2100.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The present study was carried out in Lomé and Kara (

Figure 1), the two largest cities in Togo. Lomé, the capital, is located in the extreme southern maritime region, between 1°00' and 1°50' East and between 6°50' and 6°05' North. It is bordered to the south by the Atlantic Ocean, to the west by Ghana, to the north by the Zio prefecture, and to the east by the Zio and Lacs prefectures. The Autonomous District of Greater Lomé comprises the prefectures of Agoè-Nyivé (7 communes) and Golfe (6 communes). Biogeographically, Lomé is in Togo's ecological Zone V and enjoys a subequatorial Guinean climate with two rainy seasons, an average rainfall of 800 mm and an average temperature of 28°C (Direction de la météorologie Nationale, 2020). The soil types found in Lomé are medium marine sand, colluvial and alluvial sand, and sandy clay. Kara, Togo's second-largest city, lies between 9°30' and 10° north latitude and 1° and 1°30' east longitude, more than 400 km north of Lomé. The capital of the Kozah prefecture extends over three of the prefecture's four communes: Kozah 1, Kozah 2 and Kozah 3. Kara is in ecological zone II and has a tropical Sudanian climate with a dry season, a rainy season, and an average rainfall of 1100–1700 mm. Kara's soil formations are mainly composed of basic rock.

2.2. Data Collection

The types of data used in this study include topographic, spatial, ground-truthing, biophysical, climatic, anthropogenic, and climate scenario projection data based on Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs).

Map data for administrative contours and boundaries are taken from Togo's new communal boundaries. Spatial resolution Landsat satellite images (30 m × 30 m) were acquired free of charge by downloading them from

https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov on NASA's USGS platform. These images were used to analyse the land use dynamics of the cities of Lomé and Kara over a 34-year period, divided into two 12-year steps and one 10-year step (

Table 1). The years 1988, 2000, 2012 and 2022 were chosen on the basis of Togolese population censuses and the availability of good-quality GIS and remote sensing images. The 2000 images made up for the absence of a census between 1981 and 2010, enabling us to study the impact of the population explosion on urban vegetation cover. Field verification data were used to validate the classification results by comparing them with actual observations. The modelling data used include explanatory variables that best represent the vulnerability of ecosystem cover units in the cities of Lomé and Kara to climate change. Most of these data were downloaded from the FAO's

https://earthmap.org platform, which was developed by NASA. These thematic variables are soil exposure, slope [

37] soil depth, soil texture[

38], soil type [

39] rainfall, temperature[

40], altitude[

41], demography[

36] and wood pressure[

42]. The Demographic data were obtained from the Fifth General Census of Population and Housing (RGPH-5) of 2022 [

24].

2.3. Data Processing

2.3.1. Satellite Image Processing and Classification

Landsat images were first georeferenced and then subjected to radiometric and atmospheric corrections in QGIS. Next, the bands were merged into multispectral bands, and colour compositions were applied in ENVI 4.3 software., False colors used to better differentiate vegetation, in particular with bands 5, 4, and 3 for 2022, 2012, and 2000 images, and bands 4, 3, and 2 for 1988 images. Following this, an unsupervised classification was performed in ENVI software, identifying 10 classes. Then a supervised classification based on the maximum likelihood algorithm refined the results, relying on training areas (ROI) defined from field knowledge and Google Earth images. Five land-use classes were identified for Lomé and four for Kara. These classes are woody green spaces (W_GS); shrub/herbaceous green spaces S/H_GS; built/bare ground (B/B_G); water bodies (WB) and flood zone (FZ) for Lomé and woody green spaces (W_GS); shrub/herbaceous green spaces S/H_GS; built/bare ground (B/B_G) and water bodies (WB) for Kara, the first two representing vegetation cover. Landsat images from 2022 were used as a model to classify images from 2007, 2000 and 1988 The final stage involved post-classification processes, including validation or evaluation of the classification, enhancement of the classified images, vectorization, and extraction. The classification evaluation was used to assess the relevance and accuracy of the classification. It was carried out using the Pontius matrix [

43], considered more reliable than the Kappa coefficient according to Pontius [

44]. The classified images were enhanced with post-classification algorithms in ENVI software. Finally, the images were vectorized, and the land-use units for Lomé and Kara were extracted and exported to QGIS software for cartographic editing. The classification accuracy was assessed using the Pontius matrix, considered more reliable than the Kappa coefficient according to Pontius.

2.3.2. Assessing the Dynamics of The Spatial Structure of Land-Use Units and the Landscape

For each land-use unit, at the level of each town, the rate of change from year X to year Y was calculated, using the Excel spreadsheet, by the formula:

Where Uy and Ux are the surface areas of the occupancy unit in year X and Y.

This formula makes it possible to carry out a diachronic analysis (progression or regression) and to interpret the landscape transformation of land-use dynamics in the study area [

45].

2.3.3. Processing of Multifactorial Spatial Modelling Data Related to Climate Change

Multifactorial spatial analysis (MSA) was used to project the vulnerability of land use units in the cities of Lomé and Kara to climate change until 2060 and 2100. This approach is based on five steps (

Figure 2) developed for the integration of climate change adaptation into OECD development planning, using pedagogical tools developed by GIZ.

2.3.3.1. Single-Factor Vulnerability Maps

The downloaded data related to each of the 10 variables selected in this study, covering the two cities, were divided into classes taking into account their specificities (thresholding). They were then coded from 1 to 4 according to the degree of vulnerability to Climate change (weighting) as follows. Very high degree of vulnerability (code 1), high degree of vulnerability (code 2; medium degree of vulnerability (code 3) and low degree of vulnerability (code 4)

Indeed, precipitation and temperature variations are the parameters that most determine the effects of climate change. The higher the temperature of a given region, the more vulnerable it is to CC, and the lower its rainfall, the higher its degree of vulnerability to CC. Meteorological data for 2022 were segmented into degrees of sensitivity to CC and then coded. For the demography variable, areas with high human densities are more vulnerable to CC, as the greater the population of an area, the greater the needs and consequently the greater the anthropic pressure on available resources. Population density maps for both cities were created using data from the fifth general population and housing census of 2022 [

24]. These data were categorised into four zones: the very high-density zone, high-density zone, medium-density zone, and low-density zone. Each zone was then assigned a code from 1 (high density zone) to 4 (low density zone), according to its degree of vulnerability to CC.

Concerning land use, a class typology of the 2022 land use units, based on the IPCC classification system, has been established to facilitate the analysis. These classes were coded from 1 (most vulnerable class) to 4 (low vulnerability class) according to their degree of vulnerability (

Table 2). For water erosion risk assessment, data from the slope inclination variable were applied. Data from the slope inclination variable were used to assess vulnerability to water erosion risks. Soil exposure affects evapotranspiration, rainfall and freshness. Soil depth influences water storage capacity and tree root activity. Altitude, soil type and texture influence water storage capacity and tree root activity. NDVI was used to assess wood pressure in each of the two towns. Each of these different variables for each of the two towns was divided into 4 classes and then coded.

2.3.3.2. Multifactorial Vulnerability Maps

Multifactor vulnerability maps were created by combining variables by thematic compatibility within each group. These combinations were performed in QGIS using the intersection interface. The calculated values obtained ranged from 16 (i.e. 4+4+4+4), which includes the series with multifactorial factors for a given group with high vulnerability to CC, and 4 (i.e. 1+1+1+1), which includes the series with multifactorial factors for this group with lower vulnerability to CC. These values are then recoded from 1 to 4 (from the most vulnerable to the least vulnerable) for further processing (GIZ, 2013).

2.3.3.3. Synthetic Vulnerability Map to Climate Change in 2022

The data used to generate the synthetic CC vulnerability map in 2022 included biophysical, climatic and anthropogenic vulnerability maps as well as the thematic land cover map for 2022. These various datasets were combined according to the principle of obtaining the multifactorial maps as previously developed. The resulting data were subsequently reclassified and recoded.

2.3.3.4. Synthetic Vulnerability Map to Climate Change Projected to 2060 and 2100

For the modelling of synthetic vulnerability to climate change projected to 2060 and 2100, the data considered included were variations in temperature, precipitation, and demography at these horizons following the chosen climate scenarios (SSP2_4.5 or SSP5_8.5). The biophysical variables, altitude, texture and NDVI were treated as static indices, as they do not change over time.

Base on the annual urban growth rates of 2.7 % (for the city of Lomé) and 2.3 % (for the remaining cities in Togo, including the city of Kara) and the size of the urban population in 2022 of these two cities (2,188,376 for Greater Lomé and 1582090 for the city of Kara), the populations of these cities were projected for the 2060 and 2100 horizons. Thus, in 2060, the population of the city of Lomé will be estimated at 6,022,805 inhabitants and that of the city of Kara at 3,754,095 inhabitants. In 2100, Lomé will reach 17,483,024 inhabitants, and Kara will reach 9,322,462 inhabitants.

The climate data were projected according to two scenarios, SSP2--4.5 and SSP5--8.5. By 2060, this scenario predicts a temperature increase of +2°C (SSP2-4.5) to +2.4°C (SSP5-8.5) and a decrease in precipitation from 4.62% to 7.05% [

46,

47]. By 2100, according to scenario SSP2-4.5, the global temperature will increase by +2.75°C, and precipitation will increase by 4.62%. In Under the SSP5--8.5 scenario, the planet's temperature will increase by +3.25°C by 2100, and precipitation will decrease by 7.05%[

46,

47].

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Dynamism

3.1.1. Validation of Classifications

For the city of Lomé and the city of Kara, overall, the errors related to the mapping are all less than 5%.

These classification errors are distributed in terms of quantity, exchange and offset for each classified image (

Table 3).

3.1.2. Mapping of Land-Use Land Cover Units in the Cities of Lomé and Kara from 1988, 2000, 2012 and 2022

In the city of Lomé, in 1988, the UGS (85.98%) planted with trees (26571.144 hectares) and shrubs/herbaceous greens spaces (16912.159 hectares) occupied the largest area of the city. This was followed by flood zones, which covered 3,765.601 hectares, and built/bare ground areas, which accounted for 3,142.539 hectares (6.21%). Water bodies occupied the remaining space.

In 2000 (

Table 4), the same trend was observed; in descending order, we distinguished the classes of S/H_GS covering (18576.171 hectares), followed by W_GS (15863.106 hectares), B/BG (13044.618 hectares), and flood zones (2988.666 hectares). From 2012 onwards, B/BG became the predominant land use, making up 46.02% of the city’s area. Green spaces occupied 47.27%, with S/H_GS covering 34.44% and W_GS making up 12.83%. Flood zones accounted for 6.41% of the city’s area. In 2022, the dominance of the landscape by B/BG is more pronounced, as they occupy 55.45% of the capital and extend northwards. Urban green spaces, particularly W_GS, have decreased sharply, by 8.29%, while FZ, which have almost halved, by 3.4% (

Table 4). The proportions of WB have hardly changed over the years (

Figure 3)

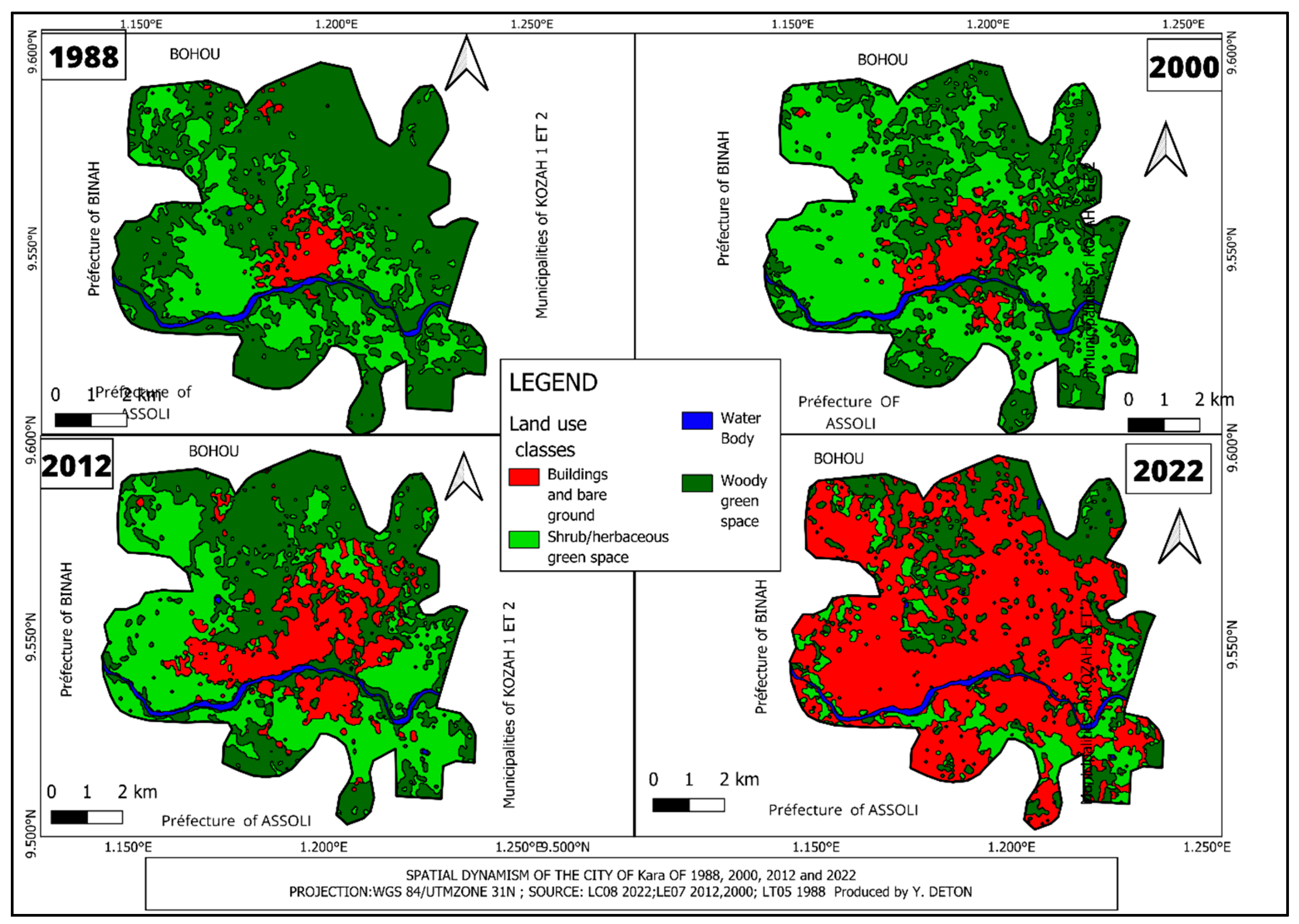

In 1988, the landscape of the city of Kara was dominated by UGSs (65.45% W_GS and 28.54% S/H_GS), which spread across almost the entire city; B/BG represented only 4.37% of the landscape and were located on the bank of the Kara River.

A similar arrangement was observed from 2000--2022 (

Table 5), with 52.96% S/H_GS, 37.31% W_GS and 8.10% B/BG. In 2012, UGSs occupied 80.72% of the city, whereas 17.6% of the B/BG developed northwards on the right bank of the Kara River. The landscape changed radically in 2022, and the proportion of UGSs 36.68% (W_GS 23.16% and S/H_GS 13.52%) has fallen sharply, giving way to B/BG 61.62%. The WB did not significantly vary across the four years: 1.64% in 1988, 1.63% in 2000, 1.68% in 2012 and 1.70% (

Figure 4).

3.1.3. Evolution of Land-Use Land Cover in the Cities of Lomé and Kara

Over the 34 years, between 1988 and 2022, there was a significant increase in the area occupied by B/BG at the expense of green spaces in the city of Lomé. Indeed, over this period, B/BG increased spatially by 23.30% per year. Water bodies also saw a slight increase of 0.26% annually. In contrast, the W_GS, S/H_GS and FZ experienced annual spatial regressions of 2.48%, 0.09% and 1.60%, respectively.

The results shown in

Table 5 enable us to carry out a diachronic analysis of the evolution of land use changes in the city of Lomé. Between 1988 and 2000, the B/BG and S/H_GS classes exhibited an annual spatial increase of 26.26% and 0.82%, while the W_GS, WB and FZ classes experienced annual spatial decrease of 3.36%, 3.66% and 1.72% respectively. From 2000 to 2012, spatial increases were observed for B/BG (6.53%), water (3.79%) and FZ (6.53%), while W_GS and S/H_GS decreased by 4.92% and 0.52%, respectively. In the third period of diachronic analysis (2012 to 2022), B/BG and WB showed an annual spatial increase of 2.05% and 3.34% respectively, while W_GS, S/H_GS and FZ declined annually by 3.54%, 0.57% and 4.69% respectively.

A diachronic analysis of the evolution of LULCs in the city of Kara (

Table 6), shows that between 1988 and 2000, the B/BG and S/H_GS classes recorded an annual spatial progression of 7.12% and 7.13% respectively, in contrast to the W_GS (3.58%) and WB (0.05%) classes, which recorded annual spatial regressions. From 2000 to 2012, only S/H_GS class showed a spatial decrease (2.05%), with the other LULCs increasing. Between 2012 and 2022, in addition to the S/H_GS class (5.51%), the W_GS class (3.6%) also recorded annual spatial regressions. B/BG (20.85%) and WB (0.36%) showed spatial progression during this period. Overall, between 1988 and 2022, the UGSs described by the S/H_GS and W_GS classes recorded annual spatial regressions, while B/BG more than doubled in surface area annually (131.15%). As for WB, their spatial area increased annually by 0.36%.

3.1.4. Spatial dynamics of Land Use Units in Lomé and Kara between 1988 and 2000; 2000 and 2012; 2012 and 2022; 1988 and 2022.

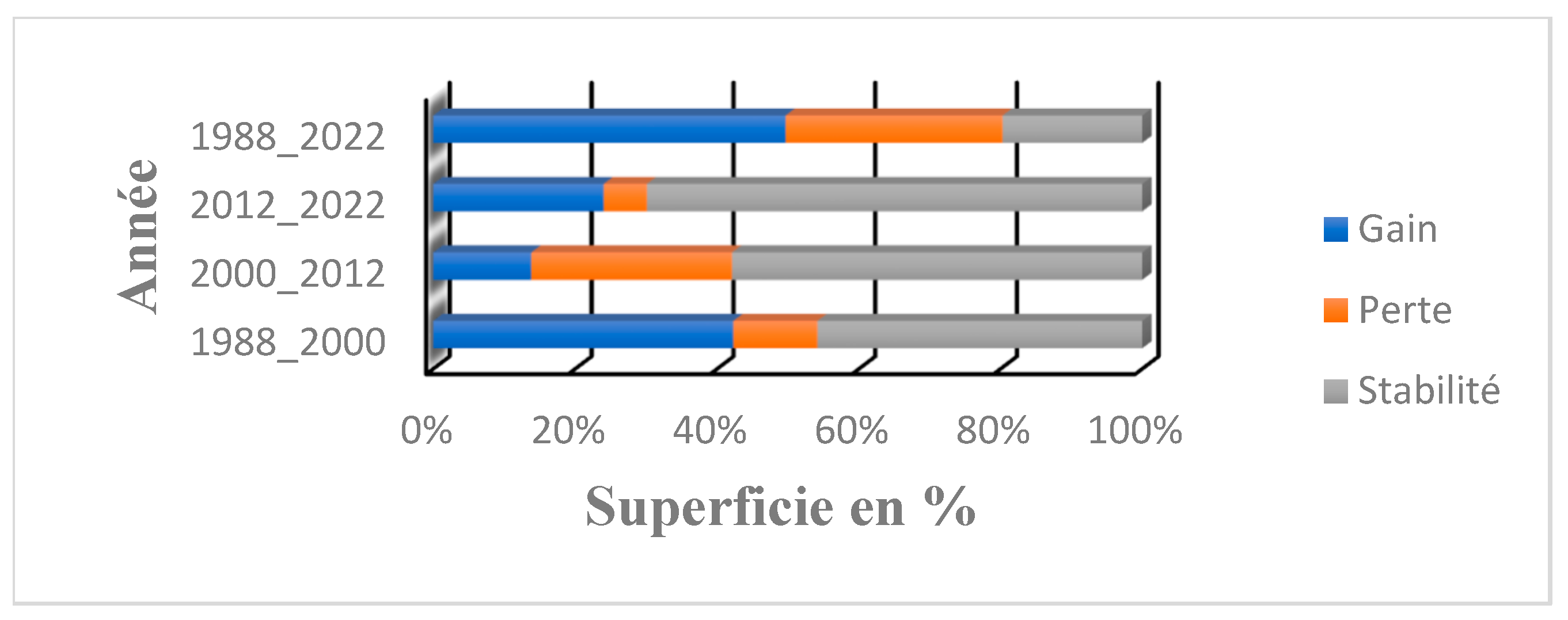

In Lomé, between 1988 and 2000, 29.73% of the city's UGS were degraded. In fact, of the 52.54% of surface area they occupied in 1988, 22.81% remained unchanged, 21.1% were transformed into S/H_GS and 5.61% into B/BG. The surface area of S/H_GS and B/BG increased by 22.63% and 19.66% respectively. FZ and WB remained unchanged. Overall, 45.87% of surface areas remained unchanged.

From 2000--2012, 57.9% of the surface area remained unchanged. The area of W_GS decreased by 22.18%, with 6.95% and 13.17% converted to B/BG and S/H_GS, respectively. On the other hand, all the other land use units experienced increases in surface area, with a maximum of 21.75% for buildings and bare ground. Between 2012 and 2022, 69.92% of the areas representing land occupation units in the city of Kara did not evolve to other classes. The classes representing UGSs, which are W_GS and S/H_GS, declined by 9.37% and 12.81%, respectively, while the extent of bare B/BG increased by 13.58%, with the largest contributions coming from green species (

Table 7).

In general, between 1988 and 2022, 19.72% (or 9973.577 ha) of the surface area remained unchanged, approximately 7.29% for S/H_GS; 6.03% for B/BG; 4.84% for W_GS; 1.41% for WB and FZ; and 0.15% for BW. Significant changes were observed in all land covers. In this case, the UGSs experienced strong deterioration, most pronounced in the W_GS class (47.7%), while the surface areas of the B/BG increased considerably (49.42%) (

Figure 5).

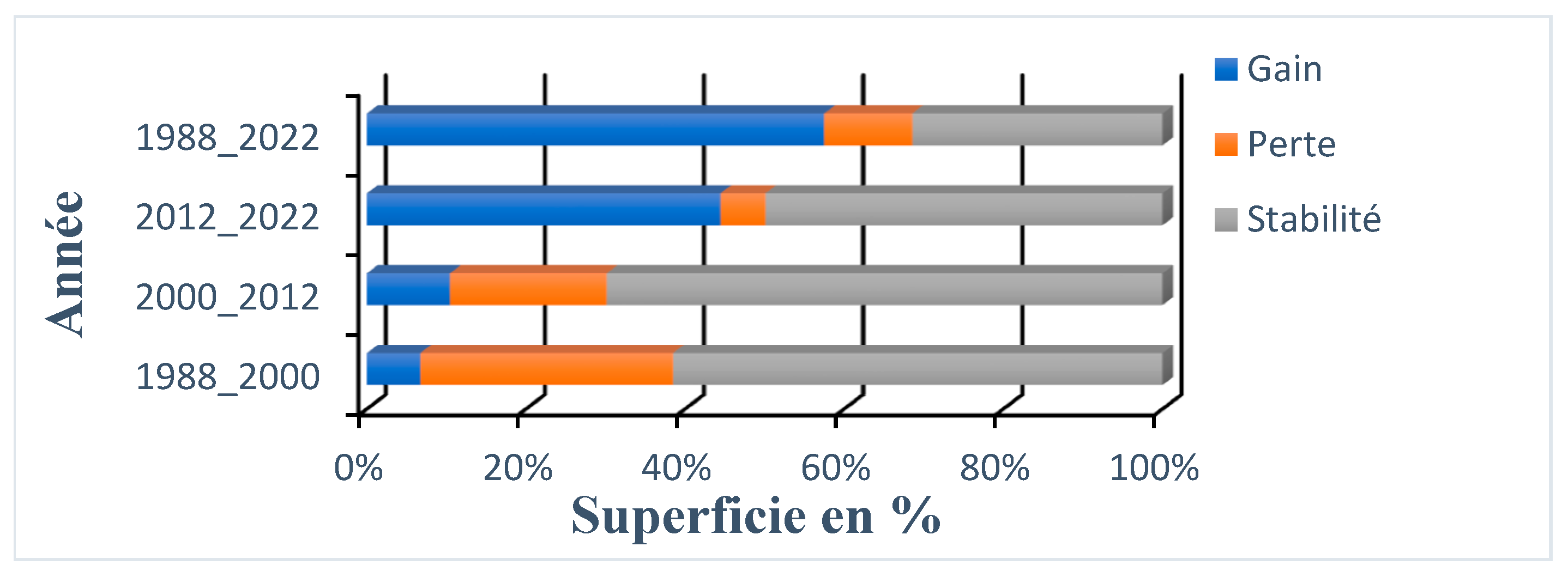

In Kara, the transition matrices of the occupancy units revealed that between 1988 and 2000, 255.11 hectares (3.61%) of the area of B/BG remained unchanged, while their surface area increased by 4.49%.

Arboreal W_GS suffered a 31.76% loss of surface area to the benefit of B/BG (1.63%) and S/H_GS (30.14%). For the S/H_GS, an increase of 30.37% was recorded. From 2000--2012, 69.84% of the spaces remained unchanged. The B/BG increased by 10.33%, with 7.3% coming S/H_GS areas and 3.04% coming from W_GS areas. The extent of W_GS increased from 37.31% to 40.80%. The surface area of S/H_GS decreased by 19.69%, with the largest proportion (12.38%) in W_GS. From 2012 to 2022, the areas of green spaces, S/H_GS and W_GS decreased by 26.49% and 17.97%, respectively, in favour of B/BG, the areas of which increased by 44.47% (

Table 9).

In 33 years, from 1988--2022, 2223,485 hectares, or 31.45% of the area, did not change to other occupation classes. The areas of the classes representing UGSs, which are S/H_GS (23.9%) and W_GS (44.38%), have fallen sharply in favour of B/BG by 22.05% and 35.47%, respectively. The extent of B/BG floors is more than half, i.e., 57.5% (

Figure 6).

3.2. Vulnerability of Land-Use Land Cover Units to Climate Change

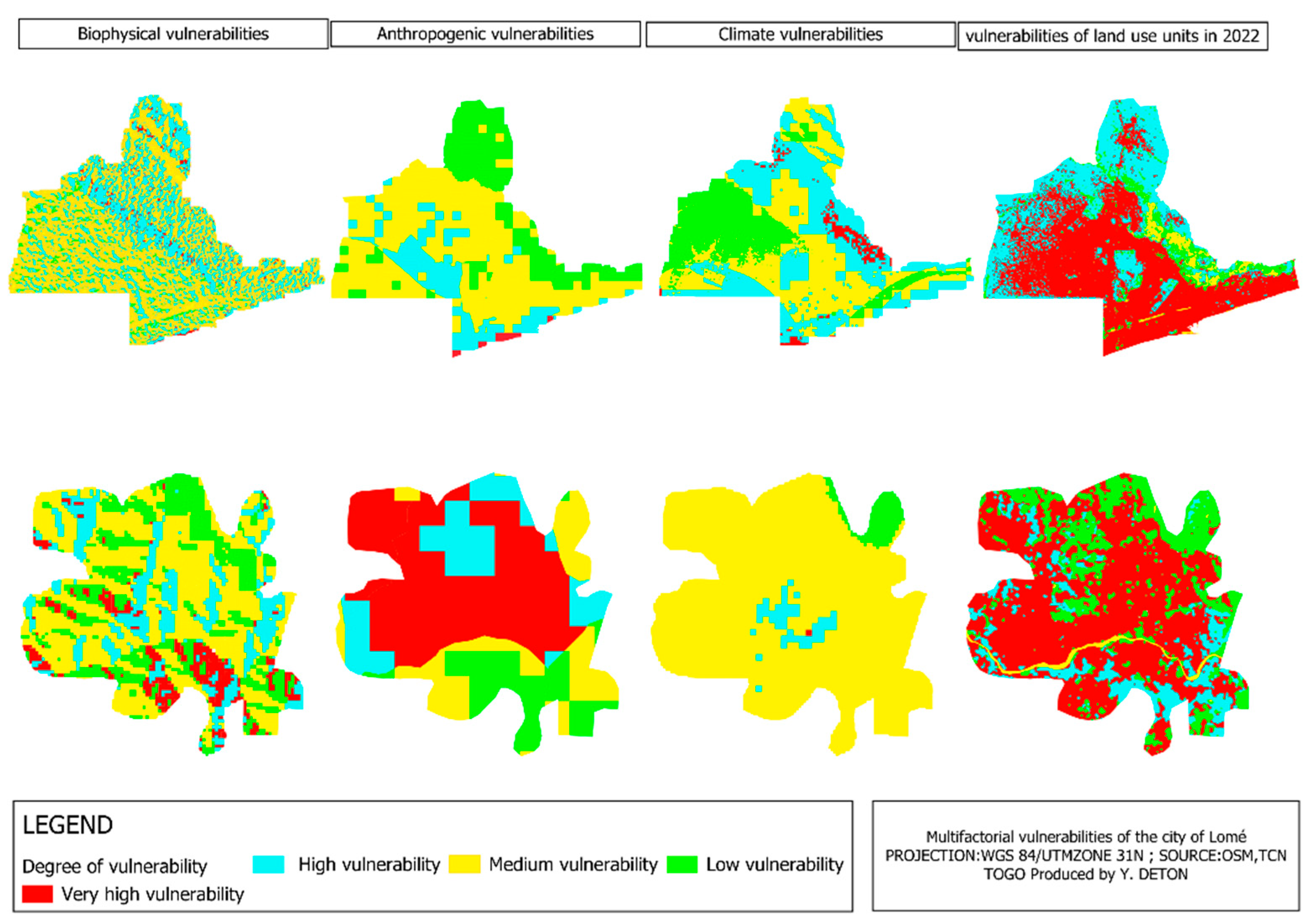

3.2.1. Multifactorial Vulnerability Related to Biophysical, Anthropogenic, Climatic and Land Cover Unit Factors in 2022

In Lomé, vulnerability to biophysical factors is average (47.32%), with 41.22% of areas highly vulnerable, whereas it is average (48.88%) and low (22.98%) in Kara.

In terms of climatic factors, Lomé has similar rates of medium (36.70%) and low (36.26%) vulnerability, whereas Kara is essentially moderately vulnerable (92.65%), with 3.76% very high vulnerability. Concerning anthropogenic factors, 57.9% of Lomé has medium vulnerability, while no vulnerability is concentrated beyond the right bank of the Kara River (

Table 8,

Figure 7).

3.2.2. Synthetic Vulnerability to Climate Change in 2022

In 2022, almost half (49.33% or 24945.44 hectares) of the city of Lomé (

Figure 9) had a moderate vulnerability to climate change, with the largest part being located in buildings and bare ground (24.52%), 22.41% in UGSs and less than 3% in wetlands.

The proportions of land with very high vulnerability and high vulnerability are 11.56% (5846.22 ha) and 22.54% (11399.63 ha), respectively; these areas are located in the largest proportions of buildings/soils (

Table 10). The areas with low vulnerability and therefore resilience to climate change represent only 16.53% or 8384.44 ha of the city and are represented mainly by UGSs. In the city of Kara, land with very high (2.02%) and high vulnerability (57.95%) is located mainly within buildings and soil. Almost a quarter (24.39% or 1724.33 hectares) of the land area shows medium vulnerability to climate change and is found within UGSs as well as land areas with low vulnerability (15.64% or 1105.72 hectares). (

Table 9 and

Figure 8).

3.2.3. Synthetic Vulnerability to Climate Change Projected to 2060 and 2100 for the Cities of Lomé and Kara

The projection models (

Figure 9) for 2060 and 2100 for the cities of Lomé and Kara, according to the SSP4--2.5 and SSP5--8.5 scenarios, reveal that the areas of gradients 4, 6, 7 and 8, as well as those of gradient 9, will show very high and high vulnerability to climate change, respectively. These areas are unable to withstand the effects of climate change. Gradient areas 10, 11 and 12 are the areas with medium climate vulnerability that will be able to maintain their ecosystem services. Areas with Grades 13, 14 and 15 will have low vulnerability to climate change and will be able to maintain their ecosystem services.

In Lomé, by 2060, under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, approximately 27.3% of the land, or 13,827.50 hectares, will be highly vulnerable and located mainly in urbanised areas. In comparison, only 4.8% of land, mainly urban green spaces, will be slightly vulnerable. The SSP5--8.5 scenario accentuates this trend, with 33.9% of the land showing medium vulnerability and a small percentage of areas showing low vulnerability. By 2100, the SSP5--8.5 scenario accentuated this trend, with 33.9% of the land at medium vulnerability and a small percentage of the area at low vulnerability. By 2100, the SSP2-4.5 projections show an increase in vulnerability, with 41.8% of Lomé's land classified as highly vulnerable. Built-up land and bare soil are the most affected. Although UGSs represent a small percentage of all UGSs, they continue to provide essential ecosystem services, although their resilience capacity is limited (

Figure 10).

In Kara, the situation is similar but with different proportions (

Figure 11). By 2060, under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, 49.56% of the land will be classified as very vulnerable, with only 6.74% being slightly vulnerable, mainly in urban green spaces. Under the SSP5--8.5 scenario, very high vulnerability will reach 69%, with the majority of the land located in urbanised areas and bare soil. By 2100, Kara will experience a dramatic increase in very vulnerable land under SSP2-4.5 (77.4%) and SSP5-8.5 (68.24%).

4. Discussion

Spatial Dynamics of land-Use Forms in the Cities of Lomé and Kara

The results of the supervised classification of Landsat imagery have yielded valid and reliable statistics confirming the robustness of Landsat imagery in monitoring urban sprawl[

18,

21,

33,

48,

49]. The classification results for the cities of Lomé and Kara show good overall accuracy with unconformities. The classified images were validated with misclassification of less than 10% for each year at the level of each of the two cities [

50]. These errors in classification and data accuracy are due mainly to exchange and lag errors for different years and land cover units. These errors have been identified through ground truth data and the use of the Pontius matrix [

43].. The Pontius matrix is more reliable than the kappa coefficient [

44].

Impact of Urbanisation on UGS Reduction

The transformation of land cover units in Lomé and Kara reflects rapid urbanisation trends. Between 1988 and 2022, minor changes in flood zones and water bodies, an intensification of buildings and bare ground, and a significant reduction in green spaces occurred. The drastic reduction in UGSs in the cities of Lomé and Kara in favor of buildings and bare land is corroborated by work carried out in other African cities, notably in Lubumbashi in D.R. Congo, where UGSs are disappearing in favor of bare buildings and soils[

51]; in Bujumbura, Burundi, UGSs halved over 33 years between 1986 and 2019[

49]; and in Sikasso and Bamako, Mali, dense and sparse vegetation decreased from 26.19% to 15.10% and from 21.5% to 5%, respectively, over 30 years[

21]. These changes are driven by population growth and economic and political pressures. Indeed, uncontrolled urbanisation is a widespread trend in developing cities, often amplified by population growth [

52]. In line with the studies of Das et al.[

53], the reduction in tree UGSs and herbaceous UGSs in Lomé and Kara has a negative impact on eco-environmental quality, reflecting the rapid decline in biodiversity and deforestation caused by agricultural and urban expansion[

54].. In Lomé and Kara, this expansion is reflected in the exponential increase in the urban population over the last 34 years from 1988--2022, thus leading to an increase in urban infrastructure. In Lomé, built-up areas and bare land, increased from 6.21% in 1988 to 55.45% in 2022. This trend is in line with the results obtained by Seto [

55] concerning the rapid urbanisation of developing cities, where demographic pressure and economic development lead to rapid urban expansion. In Kara, UGSs were dominant in the landscape but were drastically reduced in favor of built-up areas and bare land, especially in 2022. This evolution reflects similar dynamics of urbanisation and land transformation observed in other African cities, where rural and semirural areas are gradually urbanised. In addition, water resources management in Lomé and Kara has led to an increase in water bodies, to address rising water needs and flood. Fambi [

56] reported that water resource management is crucial for preventing floods and water shortages. However, flood-prone areas in Lomé have decreased due to their conversion to urbanised or agricultural land. Additionally, similar trends of increases in built-up areas and reductions in UGSs are observed in Lomé and Kara during the diachronic analysis of the rates of change in land cover units. These developments corroborate Alberti's studies [

57] on the impacts of urbanisation on natural landscapes.

The results highlight the importance of UGSs in sustainable urban planning and natural resource management.

Impact of UGS Reduction on Urban Vulnerability

In 2022, synthetic vulnerability to climate change in Lomé and Kara highlighted the crucial importance of infrastructure and land use planning for urban resilience [

25]. The predominance of buildings and bare ground considerably reduces their capacity of resilience. Additionally, the dominant rates of medium and low vulnerability to biophysical factors recorded in these two cities often relate to factors such as topography, soil quality [

58] and land use. In addition, the reduction in UGSs, combined with poorly controlled population and infrastructure growth in Lomé and Kara, exacerbates this vulnerability [

59]. In fact, rapid and uncontrolled urbanisation, identified as a major cause of anthropogenic vulnerability in these cities, is also highlighted by the work of Uscategui et al. [

60], which underlines its role in aggravating urban vulnerability.

The projections for 2060 and 2100 indicate a further increase in climate vulnerability in the cities of Lomé and Kara, with the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios showing significant differences between urban and natural areas. Indeed, "shared socioeconomic pathway" (SSP) climate scenarios are projections used to model the future impacts of climate change. SSP2_4.5 represents a moderate development scenario with intermediate climate policies, whereas SSP5_8.5 is a pessimistic scenario with rapid economic development and high use of fossil fuels. Climate projections for 2060 and 2100 revealed increased climate vulnerability Lomé and Kara, with the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios showing notable differences between urban and natural areas. The areas most affected by vulnerability are concentrated in gradients 4 to 8, which are located mainly in the areas representing built-up land and bare soil. These areas are highly vulnerable and unable to maintain their ecosystem services in the face of climate change[

36,

61]. The UGSs represent the least vulnerable areas and have the opportunity to maintain their ecological functions while adapting as ecosystem services. Indeed, both cities will see an increase in land that is highly vulnerable to CC, particularly in areas of buildings and bare soil. Although UGSs are relatively more resilient, their availability is increasingly limited, highlighting the need for conservation policies. In addition to playing a crucial role in mitigating urban climate vulnerability by providing ecosystem services, such as temperature regulation, urban heat island reduction, and improved air quality, UGSs reduce negative climate impacts and are essential for mitigating the effects of the most extreme climate scenarios[

62]. These projection models can be improved by integrating other variables, such as, floods, and urban heat highlighted in Debnath’s work [

63].

5. Conclusions

The study of the spatiotemporal dynamics of urban expansion in Lomé and Kara, concerning the conservation of UGSs and the multifactorial modelling of their vulnerability to climate change, reveals significant trends. The results highlight rapid urban growth characterised by a significant decrease in UGSs while emphasising its negative impact on climate resilience and the importance of UGSs in sustainable urban planning and natural resource management. Hence, policies for the conservation and sustainable management of UGSs are urgently needed to reduce climate vulnerability and ensure the resilience of these cities. Additionally, the preservation and extension of UGSs must be at the heart of urban development plans through reforestation and awareness-raising.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.D.; methodology, Y.D. and B.K.; software, Y.D.; validation, D.M., A.K.G., J.Y, A.A., K.B, and K.A.; formal analysis, Y.D., B.K. and A.M.; investigation, Y.D.; resources, D.M. and A.K.G.; data curation, Y.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.D.; writing—review and editing, Y.D.; D.M. and A.K.G.; visualisation, D.M., A.K.G.; A.A, J.A, B.K., H.K. and A.M.; supervision, D.M. and A.K.G.; project administration, Y.D.; funding acquisition, Y.D.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Regional Centre of Excellence on Sustainable Cities in Africa (CERViDA_DOUNEDON), the Association of African Universities (AUA) and the World Bank.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Regional Centre of Excellence on Sustainable Cities in Africa (CERViDA_DOUNEDON), the Association of African Universities (AAU) and the World Bank for the necessary financial support that facilitated our research leading to these results. We would also like to express our sincere gratitude to Cyprien AHOLOU and Kossiwa ZINSOU Épse KLASSOU for their support and visionary leadership in promoting this Center of Excellence.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hamman P, Anquetin V, Monicolle C (2017) Du « dévelopWBment durable » à la « ville durable » : quels débats aujourd’hui ?Regards croisés à partir de la littérature francophone et anglophone. VertigO 17:. [CrossRef]

- Arnould P, Le Lay YF, Dodane C, Méliani I (2011) Nature in the city: The unlikely biodiversity. Geogr Econ Soc 13:45–68. [CrossRef]

- KoWBcká M, Szatmári D, Rosina K (2017) Analysis of urban green spaces based on sentinel-2A: Case studies from Slovakia†. Land 6:. [CrossRef]

- Weng H, Gao Y, Su X, et al (2021) Spatial-Temporal Changes and Driving Force Analysis of Green. Land 10:537.

- Buchheit P, D’Aquino P, Ducourtieux O (2016) Cadres théoriques mobilisant les concepts de résilience et de vulnérabilité. VertigO 16:. [CrossRef]

- Marino D, Barone A, Marucci A, et al (2023) Impact of Land Use Changes on Ecosystem Services Supply: A Meta Analysis of the Italian Context. Land 12:. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Zhang X, Feng Y, et al (2021) Spatiotemporal dynamics of urban green space influenced by rapid urbanisation and land use policies in Shanghai. Forests 12:476. [CrossRef]

- Woldesemayat EM, Genovese PV (2021) Urban green space composition and configuration in functional land use areas in addis ababa, ethiopia, and their relationship with urban form. Land 10:1–21. [CrossRef]

- Hahs AK, McDonnell MJ, McCarthy MA, et al (2009) A global synthesis of plant extinction rates in urban areas. Ecol Lett 12:1165–1173. [CrossRef]

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2018) World Urbanisation ProsWBcts.

- Gupta K, Kumar P, Pathan SK, Sharma KP (2012) Urban Neighborhood Green Index - A measure of green spaces in urban areas. Landsc Urban Plan 105:325–335. [CrossRef]

- Brom P, Engemann K, Breed C, et al (2023) A Decision Support Tool for Green Infrastructure Planning in the Face of Rapid Urbanisation. Land 12: . [CrossRef]

- Kowe P, Mutanga O, Dube T (2021) Advancements in the remote sensing of landscaWB pattern of urban green spaces and vegetation fragmentation. Int J Remote Sens 42:3797–3832. [CrossRef]

- Rahman M, Hasan J (2024) Evaluating the Impact of Green Spaces on Urban Heat Reduction in Rajshahi , Bangladesh Using the InVEST Model. Land 13:. [CrossRef]

- Nero BF (2017) Urban green space dynamics and socioenvironmental inequity: Multiresolution and spatiotemporal data analysis of kumasi, ghana. Int J Remote Sens 38:6993–7020. [CrossRef]

- Wu D, Zhao X, Liang S, et al (2015) Time-lag effects of global vegetation responses to climate change. Glob Chang Biol 21:3520–3531. [CrossRef]

- Afuye GA, Kalumba AM, Busayo ET, Orimoloye IR (2022) A bibliometric review of vegetation response to climate change. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29:18578–18590. [CrossRef]

- Yongsi HBN, Bryant CR (2007) Contribution des SIG à l’analyse du paysage urbain d’une métropole d’Afrique tropicale humide (Yaoundé – Cameroun). Can J Reg Sci 1:133–154.

- Dahani I, Compaore G (2021) VILLE DURABLE : OUAGADOUGOU , CAPITALE DU BURKINA FASO EN AFRIQUE Issaka Dahani , Georges Compaore To cite this version : HAL Id : hal-03359473. Thèse Synth 1:56–75.

- Seth A-O, Kwaku KM, Michael OA, Owusu A (2023) Tragedy of urban green spaces depletion in selected sub-Sahara African major cities. J African Stud Dev 15:46–61. [CrossRef]

- Fomba M, Osunde ZD, Traoré SS, et al (2024) Urban Green Spaces in Bamako and Sikasso, Mali_ Land Use Changes and WBrceptions. Land 13:1–20. [CrossRef]

- Ministère du plan et de l’industrie D de la stastistique (1986) AWBRÇU DES RESULTATS D ’ ENSEMBLE RECENSEMENT GENERAL DE LA POPULATION ET DE L ’ HABITAT A : U TOGO de novembre 1981.

- INSEED (2011) QUATRIÈME RECENSEMENT GÉNÉRAL DE LA POPULATION ET DE L’HABITAT-NOVEMBRE 2010.

- INSEED (2022) Résultats finaux du 5e Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitat (RGPH-5) de novembre 2022.

- FIAWUMOR S (2016) Dynamiques résidentielles dans une ville ouest-africaine : déterminants du statut d’occupation du logement à Lomé (Togo).

- Tchindjang M, Mbevo P, Bopda A (2019) Une Afrique Atlantique avec des villes sous l ’ eau ! Construire des villes côtières sans inondations ? In: CONSTRUIRE LA VILLE PORTUAIRE DE DEMAIN EN AFRIQUE ATLANTIQUE. p 30.

- Polorigni B, Adjonou K, Radji RA (2018) Urban planning and vegetation in Togo : what approaches for the mitigation of global warming in the city of Lomé in a context of climate change ? Int Res J Environ Sci 7:67–73.

- (2022) Plan national de dévelopWBment (pnd) 2018 - 2022 3.

- MERF (2017) Plan National d’Adaptation aux Changements Climatiques du Togo (PNACC).

- Neglo A (2024) intégration des mesures d’adaptation au changement climatique dans la planification du dévelopWBment durable au Togo. Rev Organ Territ 32:210–221. [CrossRef]

- Blakime TH, Adjonou K, Komi K, et al (2024) Dynamics of Built-Up Areas and Challenges of Planning and Development of Urban Zone of Greater Lomé in Togo, West Africa. Land 13:. [CrossRef]

- Bigma B, Woegan YA, Koumantiga D, et al (2021) Cartographie et analyse diachronique des ceintures vertes villageoises de la préfecture de l’avé au Togo (Afrique de l’ouest). In: Dynamiques environnementales.

- M, DOURMA., ATAKPAMA, W., FOLEGA, F. & A (2019) Dynamique spatio-temporelle et structure de la végétation de la forêt classée d’Atakpamé au Togo. Ann L’UNIVERSITE Mar NGOUABI 19:.

- Kombate A, Folega F, Atakpama W, et al (2022) Characterisation of Land-Cover Changes and Forest-Cover Dynamics in Togo between 1985 and 2020 from Landsat Images Using Google Earth Engine. Land 11:. [CrossRef]

- Polorigni B, Adjonou K, Radji RA, Kokou K (2018) Identification of parameters of warming in urban agglomeration of Lomé (Togo), West Africa. nternational Res J Environ Sci 7:1–7.

- Kombate B, Dourma M, Fousseni F, et al (2022) Modélisation spatiale multifactorielle de la vulnérabilité des unités d’occupation du sol face au changement climatique dans la Région Centrale au Togo Modélisation spatiale multifactorielle de la vulnérabilité des unités d’occupation du sol face au chang. Ecosysthèmes et paysages 02:34–52.

- Farr, T. G., Rosen, P. A., CripWBn, R., Duren, R., Hensley, S., Kobrick, M., Paller, M., Rodriguez, E., Roth, L., Seal, D., Shaffer, S., Shimada, J., Umland, J., Werner, M., Oskin, M., Burbank, D., & Alsdorf D (2007) The shuttle radar topography mission. Rev Geophys 45:65–77. [CrossRef]

- Hengl T, Nussbaum M, Wright MN, et al (2018) Random forest as a generic framework for predictive modelling of spatial and spatiotemporal variables. WBerJ 43. [CrossRef]

- FAO et IIASA (2023) Harmonised world soil database version 2.0. Rome and Laxenbourg.

- Fick SE, Hijmans RJ (2017) WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol 37:4302–4315. [CrossRef]

- Reuter HI, Nelson A, Jarvis A (2007) An evaluation of void-filling interpolation methods for SRTM data. Int J Geogr Inf Sci 21:983–1008. [CrossRef]

- Didan, K., Munoz, A. B., Solano, R., & Huete A (2019) MODIS vegetation index user’s guide (MOD13 series).

- Pontius RG, Santacruz A (2014) Quantity, exchange, and shift components of difference in a square contingency table. Int J Remote Sens 35:7543–7554. [CrossRef]

- Pontius RG, Millones M (2011) Death to Kappa: Birth of quantity disagreement and allocation disagreement for accuracy assessment. Int J Remote Sens 32:4407–4429. [CrossRef]

- Kombate B (2021) Dynamique forestiere et variabilite des stocks de carbone dans la region centrale au togo.

- Tebaldi C, Debeire K, Eyring V, et al (2021) Climate model projections from the Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) of CMIP6. Earth Syst Dyn 12:253–293. [CrossRef]

- Lepousez Violene et Aboukrat Maxime (2022) Les Scénarios Ssp : Décryptage Et Recommandations D’Utilisation Pour Une Démarche D’Adaptation Au Changement Climatique. In: Carbone4.

- Vermeiren K, Van Rompaey A, Loopmans M, et al (2012) Urban growth of Kampala, Uganda: Pattern analysis and scenario development. Landsc Urban Plan 106:199–206. [CrossRef]

- Kabanyegeye H, Useni Sikuzani Y, Raoul SAMBIENI K, et al (2021) Trente-trois ans de dynamique spatiale de l’occupation du sol de la ville de Bujumbura, République du Burundi. Afrique Sci 18:203–215.

- Pontius RG, Shusas E, McEachern M (2004) Detecting important categorical land changes while accounting for WBrsistence. Agric Ecosyst Environ 101:251–268. [CrossRef]

- Y.U.Sikuzani, , S.C.Kaleba CN, Khonde, Y .A. Mawana, F.Malaisse J, Bogaert FMK (2017) Vingt-cinq ans de monitoring de la dynamique spatiale des espaces verts en repose à l’urbanisation dans les communes de la ville de Lubumbashi. Tropicultura 35:300–311.

- Y. A.Twumasi C, Merem JB, Namwamba, et al (2020) Degradation of Urban Green Spaces in Lagos, Nigeria: Evidence from Satellite and Demographic Data. Adv Remote Sens 09:33–52. [CrossRef]

- Das M, Mandal A, Das A, et al (2024) Urban dynamics and its impact on habitat and eco-environmental quality along urban‒rural gradient in an urban agglomeration (India). Environ Challenges 14:100824. [CrossRef]

- Oura RK (2012) Extension urbaine et protection naturelle : La difficile expérience d’Abidjan. VertigO 12:. [CrossRef]

- K. C.Seto, M. Fragkias, B. Güneralp MKR (2011) Lasp-1 Regulates Podosome Function. PLoS One 6:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Komlan Fambi, Massabalo Ayah MLB (2024) Etude hydrologique et hydraulique du bassin versant d ’ assainissement urbain du quartier Adidoadin de la commune Golfe 5 à Lomé (Togo): Proposition pour une gestion pérenne des eaux pluviales Hydrological and hydraulic study of the urban drainage catch. ESI Prepr 612–632. [CrossRef]

- Alberti M (2005) The effects of urban patterns on ecosystem function. Int Reg Sci Rev 28:168–192. [CrossRef]

- EBLIN SG, YAO AB, ANOH KA, SORO N (2017) CARTOGRAPHIE DE LA VULNÉRABILITÉ MULTIFACTORIELLE AUX RISQUES D’ÉROSION HYDRIQUE DES SOLS DE LA RÉGION D’ADIAKÉ, SUD-EST CÔTIER DE LA CÔTE D’IVOIRE. Rev Ivoir Sci Technol 30:197–216.

- Yang J, Sun J, Ge Q, Li X (2017) Assessing the impacts of urbanisation-associated green space on urban land surface temWBrature: A case study of Dalian, China. Urban For Urban Green 22:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Angarita Uscategui PN, Gallardo Amaya RJ, Oliva Gonzalez AO (2019) Analysis of urban vulnerability before natural and anthropogenic hazards: Case study, human settlement Colinas de la provincia, municipality of Ocaña, Colombia. J Phys Conf Ser 1257:. [CrossRef]

- Grantham HS, Duncan A, Evans TD, et al (2020) Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity. Nat Commun 11:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Mabon L, Shih WY (2021) Urban greenspace as a climate change adaptation strategy for subtropical Asian cities: A comparative study across cities in three countries. Glob Environ Chang 68:102248. [CrossRef]

- Debnath R, WBttit C, van Delden H, WBrez P (2024) Collaborative modelling for goal-oriented scenario planning: A resilience planning case study in the context of greater Sydney. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 100:104205. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Map of the study environment: cities of Lomé and Kara.

Figure 1.

Map of the study environment: cities of Lomé and Kara.

Figure 2.

Conceptual diagram of the Multifactorial spatial analysis (MSA), Source: GIZ, 2013.

Figure 2.

Conceptual diagram of the Multifactorial spatial analysis (MSA), Source: GIZ, 2013.

Figure 3.

Dynamics of land cover units in the city of Lomé in 1988, 2000, 2012 and 2022.

Figure 3.

Dynamics of land cover units in the city of Lomé in 1988, 2000, 2012 and 2022.

Figure 4.

Dynamics of land-use land cover units in the city of Kara in 1988, 2000, 2012 and 2022.

Figure 4.

Dynamics of land-use land cover units in the city of Kara in 1988, 2000, 2012 and 2022.

Figure 5.

Overall changes in land use units between the different dates.

Figure 5.

Overall changes in land use units between the different dates.

Figure 6.

Overall changes in land use land cover units between the different dates.

Figure 6.

Overall changes in land use land cover units between the different dates.

Figure 7.

Vulnerability of land in the cities of Lomé and Kara as a function of biophysical, anthropogenic, and climatic factors and land cover units.

Figure 7.

Vulnerability of land in the cities of Lomé and Kara as a function of biophysical, anthropogenic, and climatic factors and land cover units.

Figure 8.

Vulnerability of the LULC in 2022 of cities of Lomé and Kara to climate change.

Figure 8.

Vulnerability of the LULC in 2022 of cities of Lomé and Kara to climate change.

Figure 9.

Models of land vulnerability in the cities of Lomé and Kara by 2060 and 2100 according to SSP2-4.5 and SSP5_8.5.

Figure 9.

Models of land vulnerability in the cities of Lomé and Kara by 2060 and 2100 according to SSP2-4.5 and SSP5_8.5.

Figure 10.

Degree of vulnerability of the land in the city of Lomé by 2060 and 2100 according to SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5.

Figure 10.

Degree of vulnerability of the land in the city of Lomé by 2060 and 2100 according to SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5.

Figure 11.

Degree of vulnerability of the land in the city of Lomé by 2060 and 2100 according to SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5.

Figure 11.

Degree of vulnerability of the land in the city of Lomé by 2060 and 2100 according to SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Landsat images from 1988_2000_2012_2022.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Landsat images from 1988_2000_2012_2022.

| Scene years and locations |

Satellite image types |

Scene reference |

Acquisition date |

Résolution |

| Path |

Row |

| 1988_Lomé |

Landsat 4 TM |

192 |

056 |

1988-02-12 |

30 m |

| 1988_Kara |

Landsat 5 TM |

193 |

053 |

1988-12-11 |

30 m |

| 2000_Lomé |

Landsat 7 ETM |

192 |

056 |

2000-12-13 |

30 m |

| 2000_Kara |

Landsat 7 ETM |

193 |

053 |

2000-12-04 |

30 m |

| 2012_Lomé |

Landsat 7 ETM |

192 |

056 |

2012-01-13 |

30 m |

| 2012_Kara |

Landsat 7 ETM |

193 |

053 |

2012-12-21 |

30 m |

| 2022_Lomé |

Landsat 9 OLI_TIRS |

192 |

056 |

2022-01-24 |

30 m |

| 2022_Kara |

Landsat 9 OLI_TIRS |

193 |

053 |

2022-02-16 |

30 m |

Table 2.

Land use coding matrix.

Table 2.

Land use coding matrix.

| Cities |

LULC |

IPCC Classification |

CC Vulnerability |

Assigned Code |

| Lomé |

Buildings and bare floors |

built-up area |

Very High |

1 |

| shrub/herbaceous green space |

Cultivated land |

High |

2 |

| Water bodies |

Wet zone |

average |

3 |

| Flood zones |

| Woody green space |

Forestland |

Low |

4 |

| Kara |

Buildings and bare floors |

built-up area |

Very High |

1 |

| shrub/herbaceous green space |

Cultivated land |

High |

2 |

| Water bodies |

Wet zone |

average |

3 |

| Woody green space |

Forestland |

Low |

4 |

Table 3.

Overall classification discrepancies for Lomé and Kara images.

Table 3.

Overall classification discrepancies for Lomé and Kara images.

| |

Lomé |

Kara |

| Years |

Quantity |

Exchange |

Shift |

Quantity |

Exchange |

Shift |

| 1988 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

| 2000 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

| 2012 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

| 2022 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

Table 4.

Surface area and percentage of land use units in the city of Lomé.

Table 4.

Surface area and percentage of land use units in the city of Lomé.

| Years |

Area 1988 |

Surface area 2000 |

Surface area 2012 |

Surface area 2022 |

| LULC |

In ha |

In % |

In ha |

In % |

In ha |

In % |

In ha |

In % |

| Buildings and bare ground (B/BG) |

3142,539 |

6,21 |

13044,618 |

25,79 |

23273,601 |

46,02 |

28042,658 |

55,45 |

|

shrub/herbaceousgreen space (S/H_GS)

|

16912,159 |

33,44 |

18576,171 |

36,73 |

17419,708 |

34,44 |

16419,617 |

32,47 |

| Woody green space (W_GS) |

26571,144 |

52,54 |

15863,106 |

31,36 |

6490,331 |

12,83 |

4192,969 |

8,29 |

| Water bodies (WB) |

184,504 |

0,36 |

103,386 |

0,20 |

150,449 |

0,30 |

200,742 |

0,40 |

| Flood zones (FZ) |

3765,601 |

7,45 |

2988,666 |

5,91 |

3241,858 |

6,41 |

1719,961 |

3,40 |

| Total |

50575,947 |

100 |

50575,947 |

100 |

50575,947 |

100 |

50575,947 |

100 |

Table 5.

Area and percentage of land Use Land cover units in the city of Kara.

Table 5.

Area and percentage of land Use Land cover units in the city of Kara.

| Years |

Area 1988 |

Surface area 2000 |

Surface area 2012 |

Surface area 2022 |

| LULC |

In ha |

In % |

In ha |

In % |

In ha |

In % |

In ha |

In % |

| Buildings and bare ground (B/BG) |

308,649 |

4,37 |

572,325 |

8,10 |

1244,151 |

17,60 |

4356,71 |

61,62 |

| Woody green space (W_GS) |

4627,316 |

65,45 |

2637,949 |

37,31 |

2884,744 |

40,80 |

1637,358 |

23,16 |

| shrub/herbaceous green space (S/H_GS) |

2018,063 |

28,54 |

3744,325 |

52,96 |

2822,452 |

39,92 |

955,813 |

13,52 |

| Water bodies (WB) |

115,791 |

1,64 |

115,13 |

1,63 |

118,472 |

1,68 |

119,938 |

1,70 |

| Total |

7069,819 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

7069,819 |

100 |

7069,819 |

100 |

Table 6.

Annual rate of change in Lomé's land-use Land cover units.

Table 6.

Annual rate of change in Lomé's land-use Land cover units.

| |

Annual rate of change in % |

| |

Lomé |

|

Kara |

| LULC |

1988_2000 |

2000_2012 |

2012_2022 |

1988_2022 |

LULC |

1988_2000 |

2000_2012 |

2012_2022 |

1988_2022 |

| B/BG |

26,26 |

6,53 |

2,05 |

23,3 |

B/BG |

7,12 |

9,78 |

20,85 |

131,15 |

| S/H_GS |

0,82 |

-0,52 |

-0,57 |

-0,09 |

W_GS |

-3,58 |

0,78 |

-3,6 |

-6,46 |

| W_GS |

-3,36 |

-4,92 |

-3,54 |

-2,48 |

S/H_GS |

7,13 |

-2,05 |

-5,51 |

-5,26 |

| WB |

-3,66 |

3,79 |

3,34 |

0,26 |

WB |

-0,05 |

0,24 |

0,1 |

0,36 |

| FZ |

-1,72 |

0,71 |

-4,69 |

-1,6 |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 7.

LULC transition matrix for the city of Lomé between 1988 and 2000; 2000 and 2012; 2012 and 2022; 1988 and 2022.

Table 7.

LULC transition matrix for the city of Lomé between 1988 and 2000; 2000 and 2012; 2012 and 2022; 1988 and 2022.

| |

Year2000 |

|

Year2012 |

| LULC |

B/BG |

S/H_GS |

WB |

W_GS |

WA |

Total |

LULC |

B/BG |

S/H_GS |

WB |

W_GS |

WA |

Total |

| Year 1988 |

B/BG |

6,13 |

0,02 |

0,04 |

0,03 |

0,00 |

6,21 |

Year 2000

|

BBG |

24,27 |

0,69 |

0,18 |

0,65 |

0,00 |

25,79 |

| S/H_GS |

13,76 |

14,10 |

0,00 |

5,36 |

0,22 |

33,44 |

H_GS |

14,76 |

20,00 |

0,00 |

1,97 |

0,00 |

36,73 |

| WB |

0,20 |

0,00 |

0,15 |

0,01 |

0,00 |

0,36 |

WB |

0,03 |

0,01 |

0,10 |

0,06 |

0,00 |

0,20 |

| W_GS |

5,61 |

21,10 |

0,01 |

22,81 |

3,01 |

52,54 |

W_GS |

6,95 |

13,17 |

0,01 |

9,18 |

2,06 |

31,36 |

| WA |

0,10 |

1,51 |

0,00 |

3,15 |

2,68 |

7,45 |

WA |

0,01 |

0,58 |

0,00 |

0,97 |

4,35 |

5,91 |

| Total |

25,79 |

36,73 |

0,20 |

31,36 |

5,91 |

100 |

Total |

46,02 |

34,44 |

0,30 |

12,83 |

6,41 |

100 |

| |

Year 2022

|

|

Year 2022

|

| LULC |

BBG |

H_GS |

WB |

W_GS |

WA |

Total |

LULC |

BBG |

H_GS |

WB |

W_GS |

WA |

Total |

| Year 2012 |

B/BG |

41,86 |

3,36 |

0,08 |

0,72 |

0,00 |

46,02 |

Year 1988

|

B/BG |

6,03 |

0,01 |

0,07 |

0,10 |

0,00 |

6,21 |

| S/H_GS |

11,29 |

21,63 |

0,04 |

1,46 |

0,03 |

34,44 |

S/H_GS |

24,33 |

7,29 |

0,07 |

1,58 |

0,16 |

33,44 |

| WB |

0,12 |

0,00 |

0,16 |

0,02 |

0,00 |

0,30 |

WB |

0,18 |

0,00 |

0,15 |

0,03 |

0,01 |

0,36 |

| W_GS |

2,07 |

6,62 |

0,13 |

3,46 |

0,55 |

12,83 |

W_GS |

23,38 |

22,38 |

0,10 |

4,84 |

1,83 |

52,54 |

| WA |

0,10 |

0,87 |

0,00 |

2,63 |

2,81 |

6,41 |

WA |

1,52 |

2,78 |

0,00 |

1,73 |

1,41 |

7,45 |

| Total |

55,45 |

32,47 |

0,40 |

8,29 |

3,40 |

100 |

Total |

55,45 |

32,47 |

0,40 |

8,29 |

3,40 |

100 |

Table 8.

Transition matrix of LULCs in the city of Kara between 1988 and 2000, 2000 and 2012, 2012 and 2022, and 1988 and 2022.

Table 8.

Transition matrix of LULCs in the city of Kara between 1988 and 2000, 2000 and 2012, 2012 and 2022, and 1988 and 2022.

| |

Year 2000

|

Year 2012

|

| LULC |

BBG |

H_GS |

WB |

W_GS |

Total |

Year 2000

|

LULC |

BBG |

H_GS |

WB |

W_GS |

Total |

|

| Year 1988

|

BBG |

3,61 |

0,24 |

0,00 |

0,52 |

4,37 |

BBG |

7,27 |

0,07 |

0,00 |

0,76 |

8,10 |

|

| H_GS |

2,86 |

22,59 |

0,00 |

3,10 |

28,54 |

H_GS |

7,30 |

33,27 |

0,02 |

12,38 |

52,96 |

|

| WB |

0,00 |

0,00 |

1,63 |

0,01 |

1,64 |

WB |

0,00 |

0,00 |

1,63 |

0,00 |

1,63 |

|

| W_GS |

1,63 |

30,14 |

0,00 |

33,69 |

65,45 |

W_GS |

3,04 |

6,58 |

0,03 |

27,67 |

37,31 |

|

| Total |

8,10 |

52,96 |

1,63 |

37,31 |

100 |

Total |

17,60 |

39,92 |

1,68 |

40,80 |

100 |

|

| |

Year 2022

|

Year 2022

|

| LULC |

BBG |

H_GS |

WB |

W_GS |

Total |

Year 1988

|

LULC |

BBG |

H_GS |

WB |

W_GS |

Total |

|

| Year 2012

|

BBG |

17,15 |

0,06 |

0,00 |

0,39 |

17,60 |

BBG |

4,11 |

0,03 |

0,00 |

0,23 |

4,37 |

|

| H_GS |

26,49 |

10,89 |

0,00 |

2,54 |

39,92 |

H_GS |

22,05 |

4,64 |

0,01 |

1,85 |

28,54 |

|

| WB |

0,01 |

0,00 |

1,64 |

0,02 |

1,68 |

WB |

0,00 |

0,00 |

1,63 |

0,01 |

1,64 |

|

| W_GS |

17,97 |

2,57 |

0,05 |

20,21 |

40,80 |

W_GS |

35,47 |

8,85 |

0,06 |

21,07 |

65,45 |

|

| Total |

61,62 |

13,52 |

1,70 |

23,16 |

100 |

Total |

61,62 |

13,52 |

1,70 |

23,16 |

100 |

|

Table 9.

Degree of vulnerability of land in the cities of Lomé and Kara as a function of biophysical, climatic and anthropogenic factors.

Table 9.

Degree of vulnerability of land in the cities of Lomé and Kara as a function of biophysical, climatic and anthropogenic factors.

| Degree of vulnerability |

Biophysical vulnerability |

Climatic vulnerability |

Anthropogenic vulnerability |

| Surface area in % |

|---|

| Lomé |

Kara |

Lomé |

Kara |

Lomé |

Kara |

| Very high vulnerability |

3,53 |

9,62 |

3,6 |

0,08 |

0,91 |

49,61 |

| High vulnerability |

41,22 |

18,52 |

36,28 |

3,68 |

16,81 |

17,88 |

| average vulnerability |

47,32 |

48,88 |

36,7 |

92,65 |

57,9 |

18,53 |

| Low vulnerability |

7,93 |

22,98 |

23,42 |

3,59 |

24,38 |

13,98 |

| Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Table 10.

Degree of vulnerability of LULCs in the cities of Lomé and Kara in 2022.

Table 10.

Degree of vulnerability of LULCs in the cities of Lomé and Kara in 2022.

| |

Very high vulnerability |

High vulnerability |

Average vulnerability |

low vulnerability |

Total |

| Surface area in % |

| |

Lomé |

Kara |

Lomé |

Kara |

Lomé |

Kara |

Lomé |

Kara |

Lomé |

Kara |

| B/BG |

10,9 |

2,02 |

17,97 |

53,45 |

24,52 |

6,15 |

2,05 |

0 |

55,45 |

61,62 |

| UGSs (W_GS and S/H_GS) |

0,63 |

0 |

4,29 |

4,49 |

22,41 |

17,04 |

13,43 |

15,15 |

40,76 |

36,68 |

| Wet Zone (FZ et WB) |

0,03 |

0 |

0,28 |

0,01 |

2,4 |

1,2 |

1,1 |

0,49 |

3,8 |

1,7 |

| Total |

11,56 |

2,02 |

22,54 |

57,95 |

49,33 |

24,39 |

16,53 |

15,64 |

100 |

100 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).