Submitted:

01 October 2024

Posted:

02 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

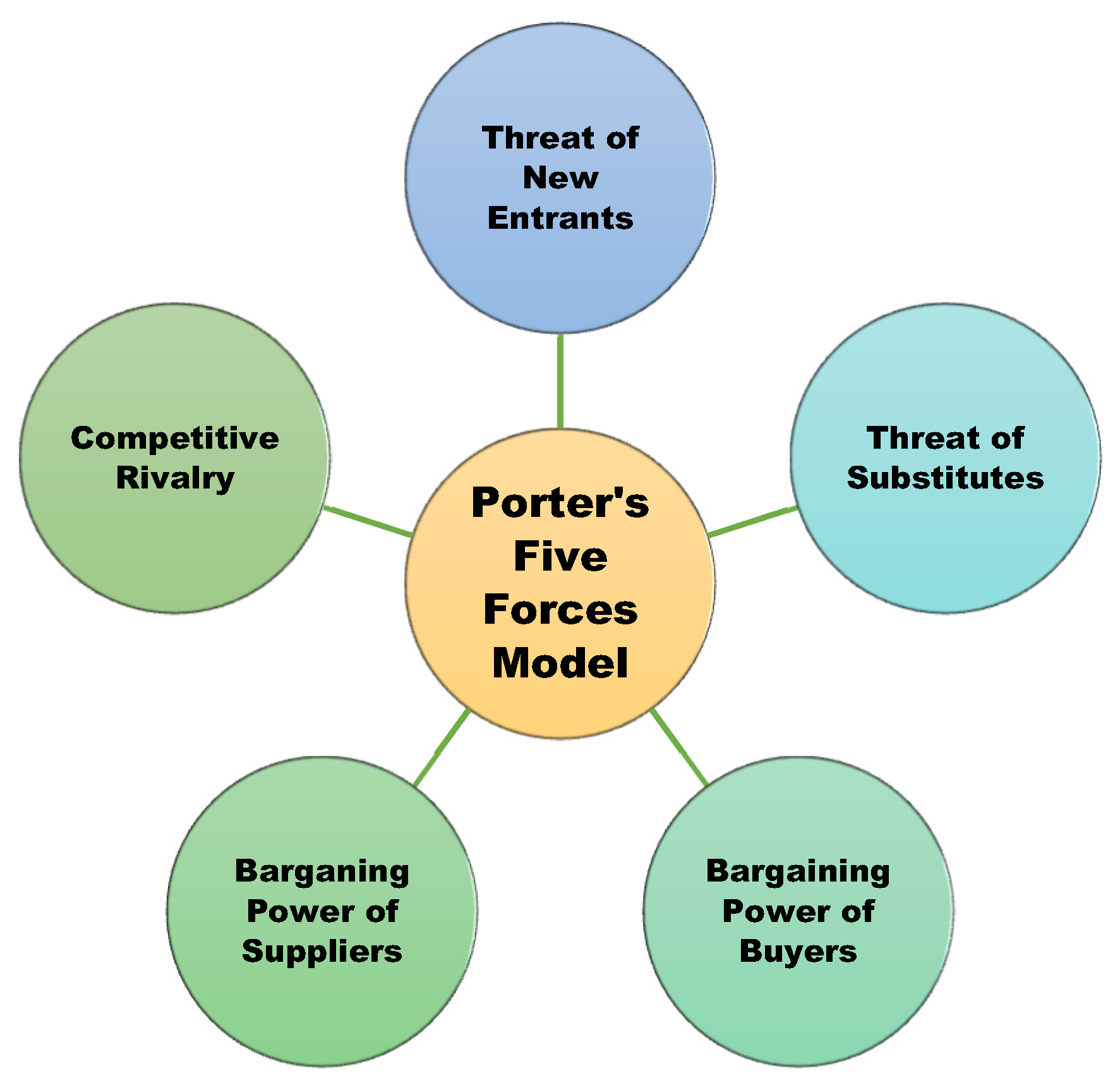

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.1.1. Threat of New Entrants

1.1.2. Threat of New Substitutes

1.1.3. Rivalry amongst Existing Competitors

1.1.4. The Bargaining Power of Buyers

1.1.5. The Bargaining Power of Suppliers

1.2. Research Questions

- How does the bargaining power of suppliers impact the performance of SMEs in various industries?

- What is the effect of buyer bargaining power on the competitive positioning and financial performance of SMEs?

- How do threats from substitute products or services influence innovation and strategic decisions in SMEs?

- To what extent do barriers to entry affect the growth and sustainability of SMEs in competitive markets?

- How does competitive rivalry within the Information Technology (IT) sector influence the strategic responses and performance outcomes of SMEs?

1.3. Research Motivation

- SMEs are critical for economic growth, employment, and innovation in both developed and developing economies. However, they face distinct challenges such as limited resources, market volatility, and competition from larger firms. Thus, understanding the factors influencing their performance is vital for their sustainability and growth. For instance, research on SMEs in Nairobi highlights the significance of cost leadership, differentiation, and focus strategies on driving performance, although findings may be context-specific to the region.

- The Porter’s Five Forces Model, a widely recognized framework for analyzing industry structure and competition. Despite its extensive use in large corporations, its application to SMEs remains underexplored. Given SMEs’ unique characteristics—such as flexibility and resource constraints—this gap presents an opportunity for further study. Existing literature, such as research on Japanese SMEs integrating the Five Forces into business intelligence, offers insights but may not be generalizable to other cultural or industrial contexts.

- The systematic review seeks to fill the gap by synthesizing research on the application of Porter’s Five Forces to SMEs. While studies have focused on specific sectors, such as telecommunications in Kenya and technological innovations in SMEs, the broader impact of competitive forces on SME performance across various industries and regions remains underexplored. Moreover, the growing influence of digital platforms and e-commerce, which are reshaping the competitive landscape for SMEs, has not been adequately addressed. By examining these dynamics, this review aims to provide insights into strategic responses of SMEs and identify best practices to enhance their resilience in an increasingly globalized market. These insights are crucial for shaping business strategies, policy interventions, and future academic research aimed at improving SME performance.

1.4. Research Contribution

- It consolidates literature across various industries to reveal how competitive forces such as the threat of new entrants, bargaining power of suppliers and buyers, the threat of substitutes, and industry rivalry affect SMEs differently compared to larger firms. For example, while research on the apparel industry explores competitive strategies specific to that sector, the findings may not be broadly applicable to other industries.

- This review delves into how technological innovation, digital transformation, and globalization have reshaped competitive forces for SMEs. Studies show that digital platforms and marketing strategies are increasingly influencing SME performance. This review offers new insights into how SMEs adapt their strategies in response to these technological shifts, contributing to their strategic positioning in a rapidly changing market.

- Identifies key gaps in current research, particularly concerning the effects of emerging trends such as digital platforms and e-commerce on SMEs’ competitive strategies. By addressing these contemporary developments, the review not only advances theoretical understanding but also provides practical guidance for SME managers and policymakers. This enhanced perspective helps in better navigating the complex and evolving competitive landscape, offering actionable insights for improving SME performance and strategic positioning in a rapidly changing global market.

1.5. Research Novelty

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility

2.2. Information Sources

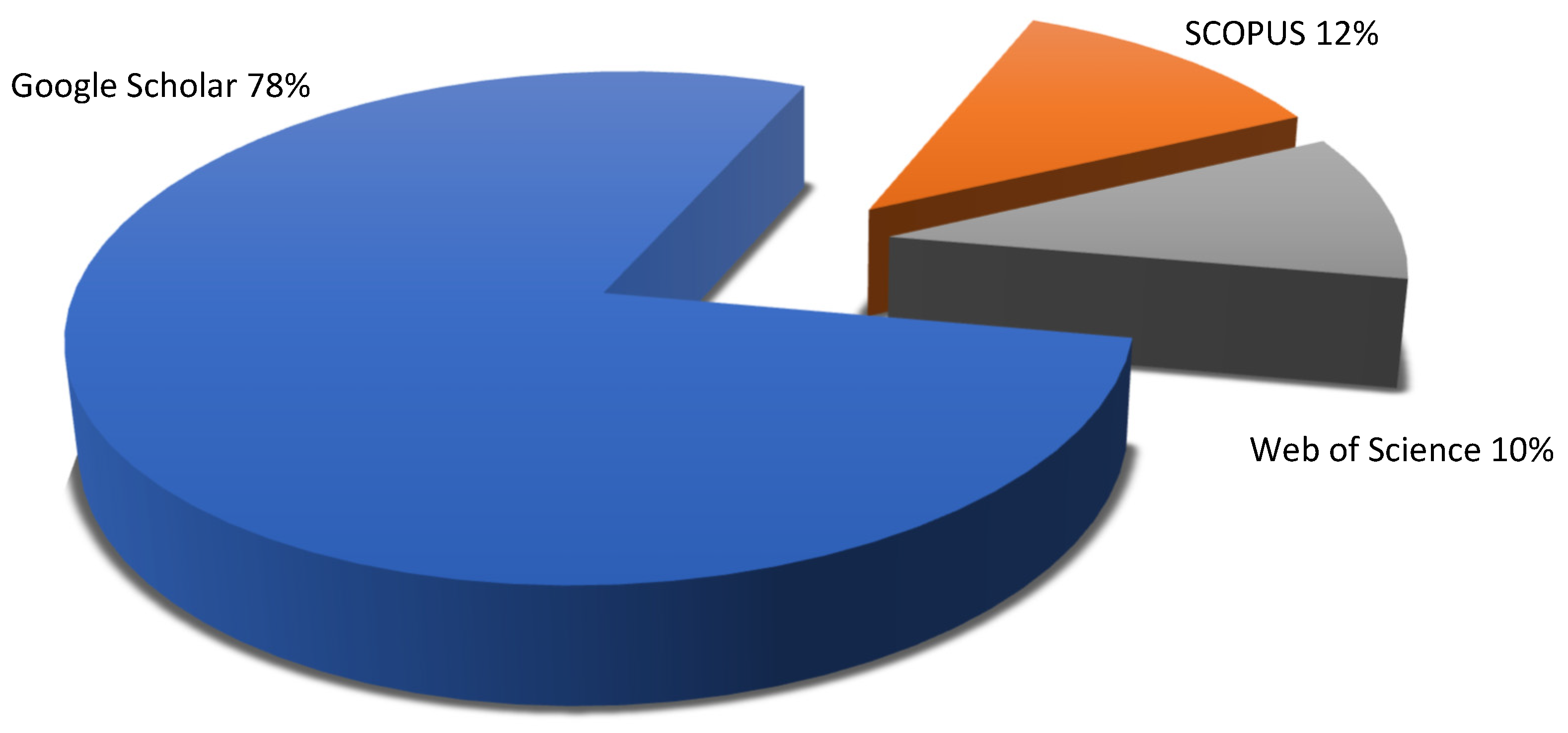

2.3. Search Strategy

| Search Terms& Strategy | Data Bases | Fields | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porter’s Five Forces OR Poter’s Model OR Five Forces Or Five Forces Model | AND | SMEs OR Small and Medium Enterprises OR Small Businesses OR Medium Enterprises |

AND | Performance OR business performance OR competitiveness OR strategic performance OR sustainability | Google Scholar Web of Science SCOPUS |

Title, Abstract Keywords |

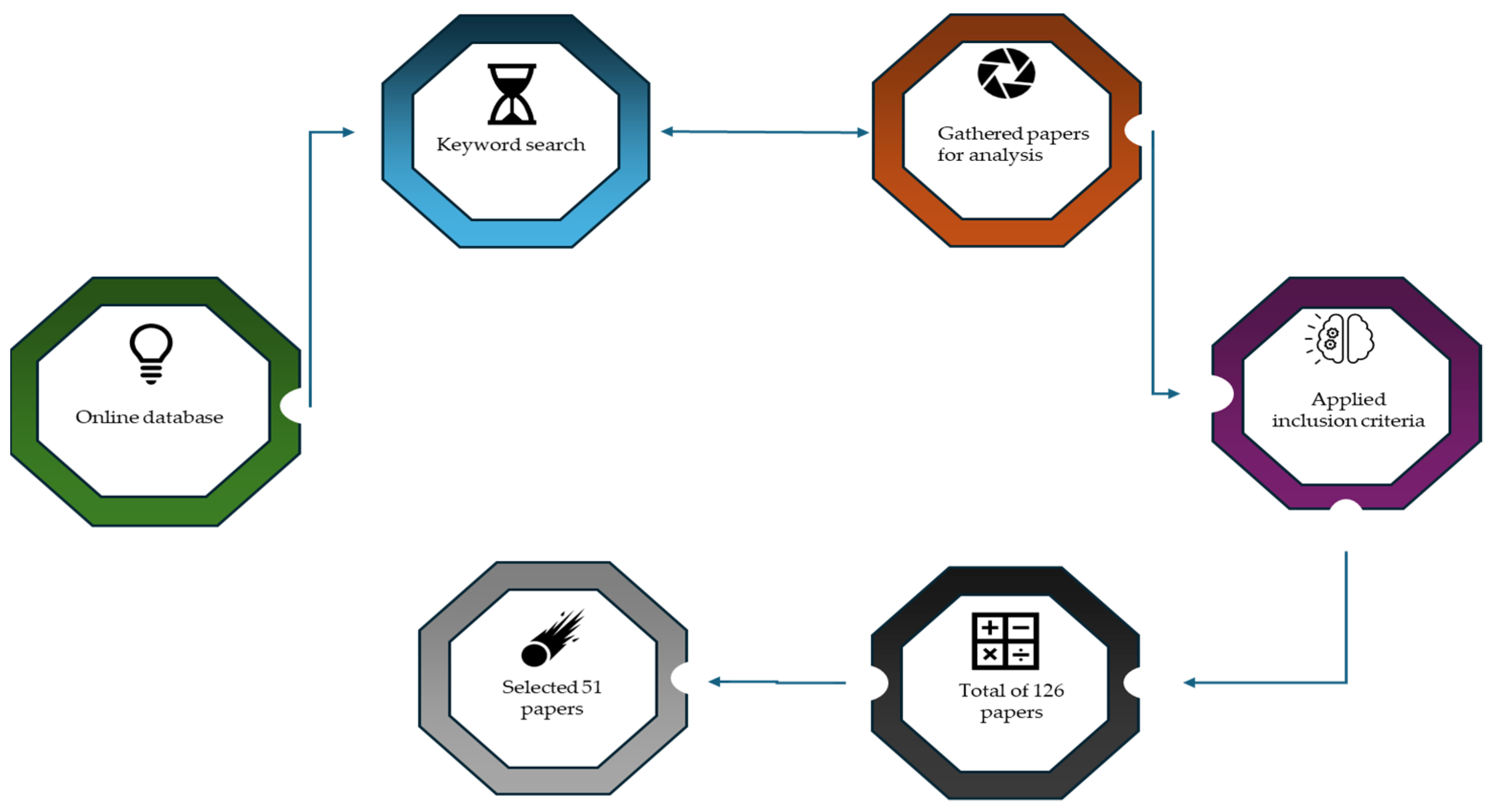

2.4. Selection Process

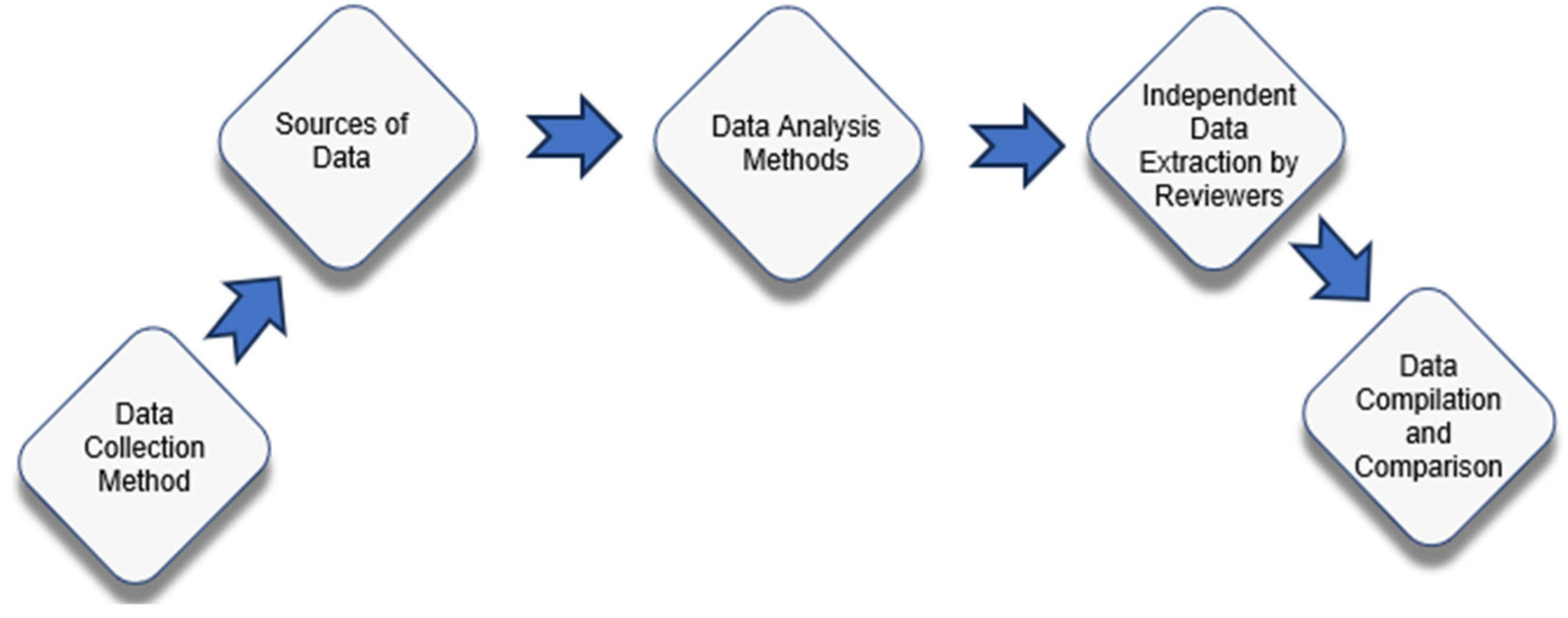

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Data Items

2.7. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.8. Effect Measures

2.9. Synthesis Methods

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

| Study Eligibility and Review | Determined study eligibility using inclusion and exclusion criteria for Five Forces and SMEs. |

| Data Preparation and Consistency | Unified coding of variables between studies for consistent labeling and analysis. |

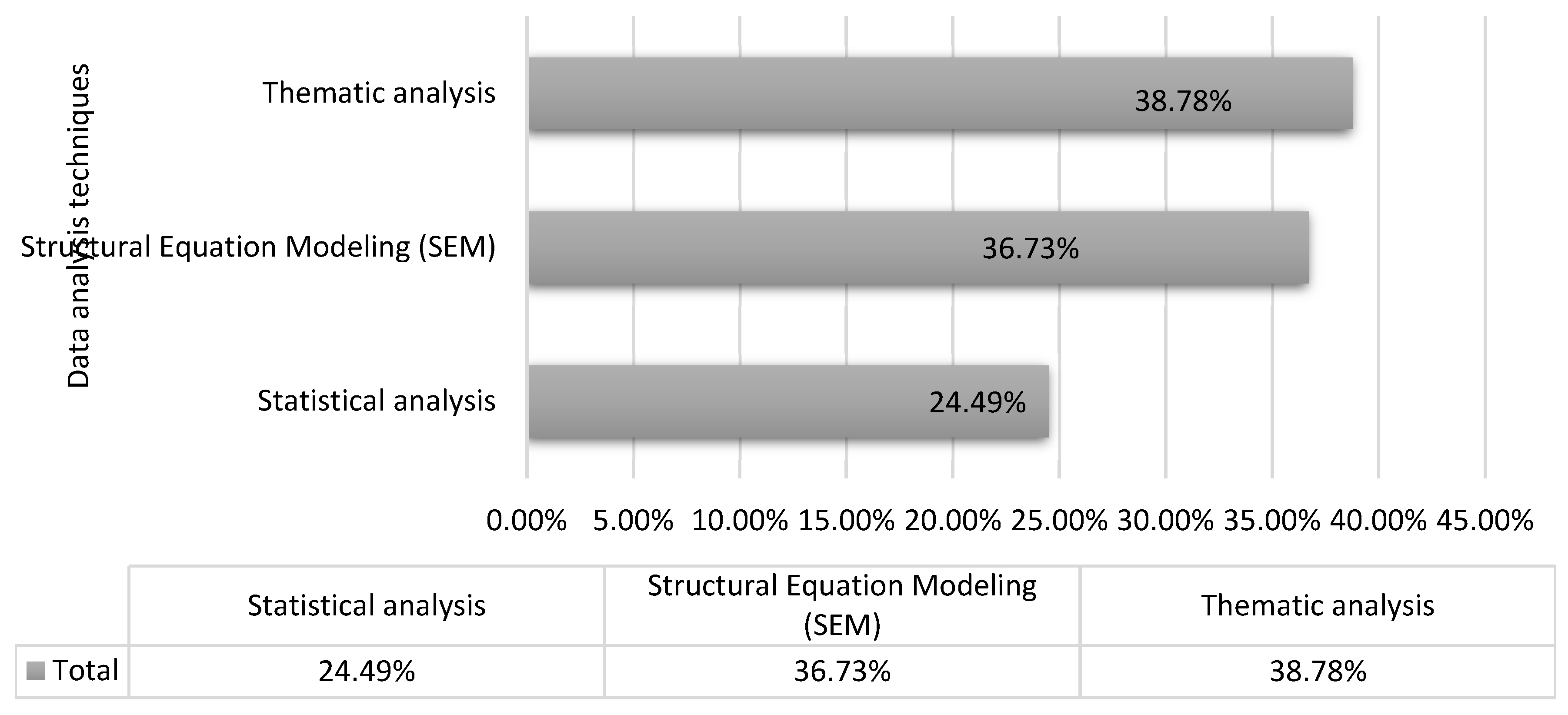

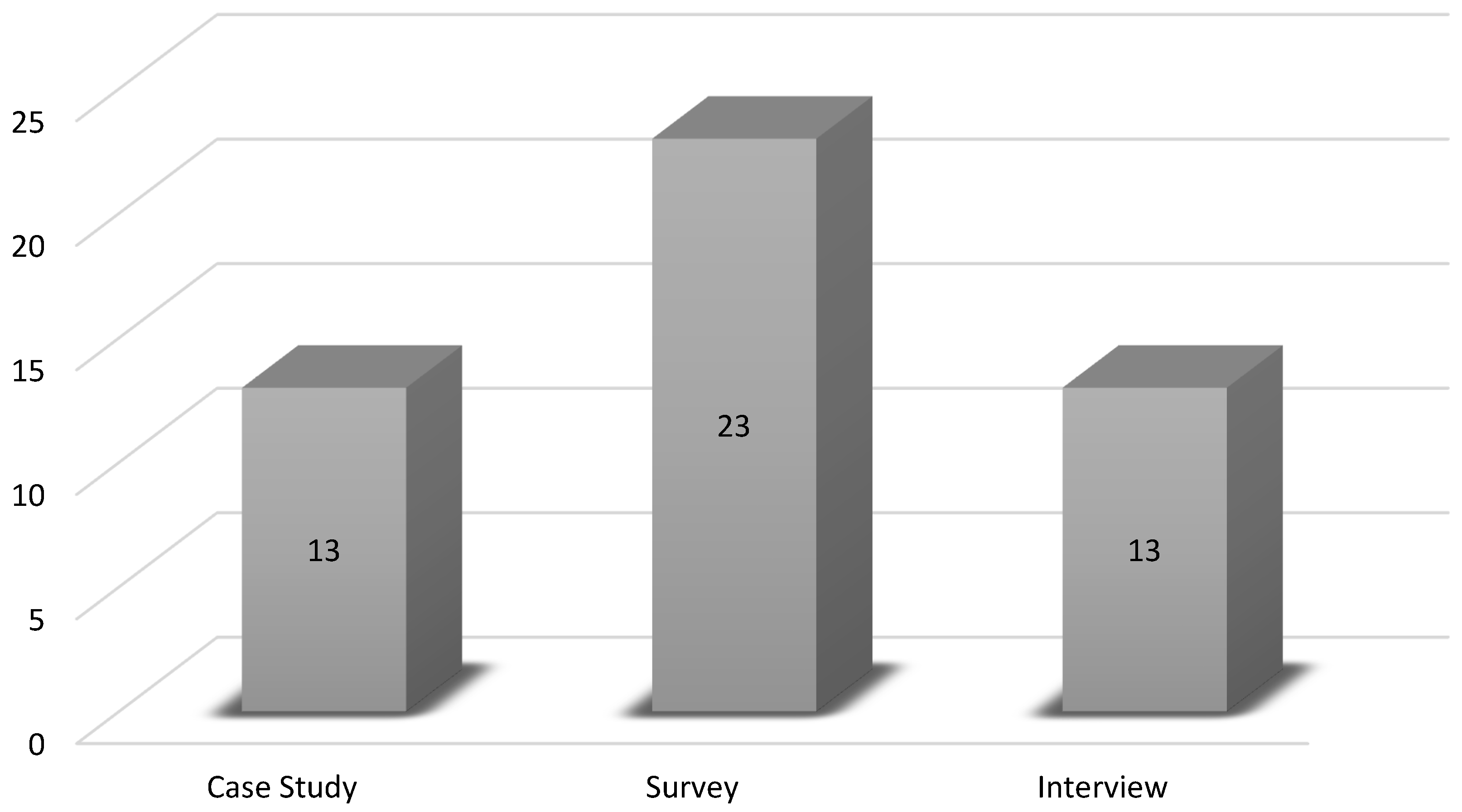

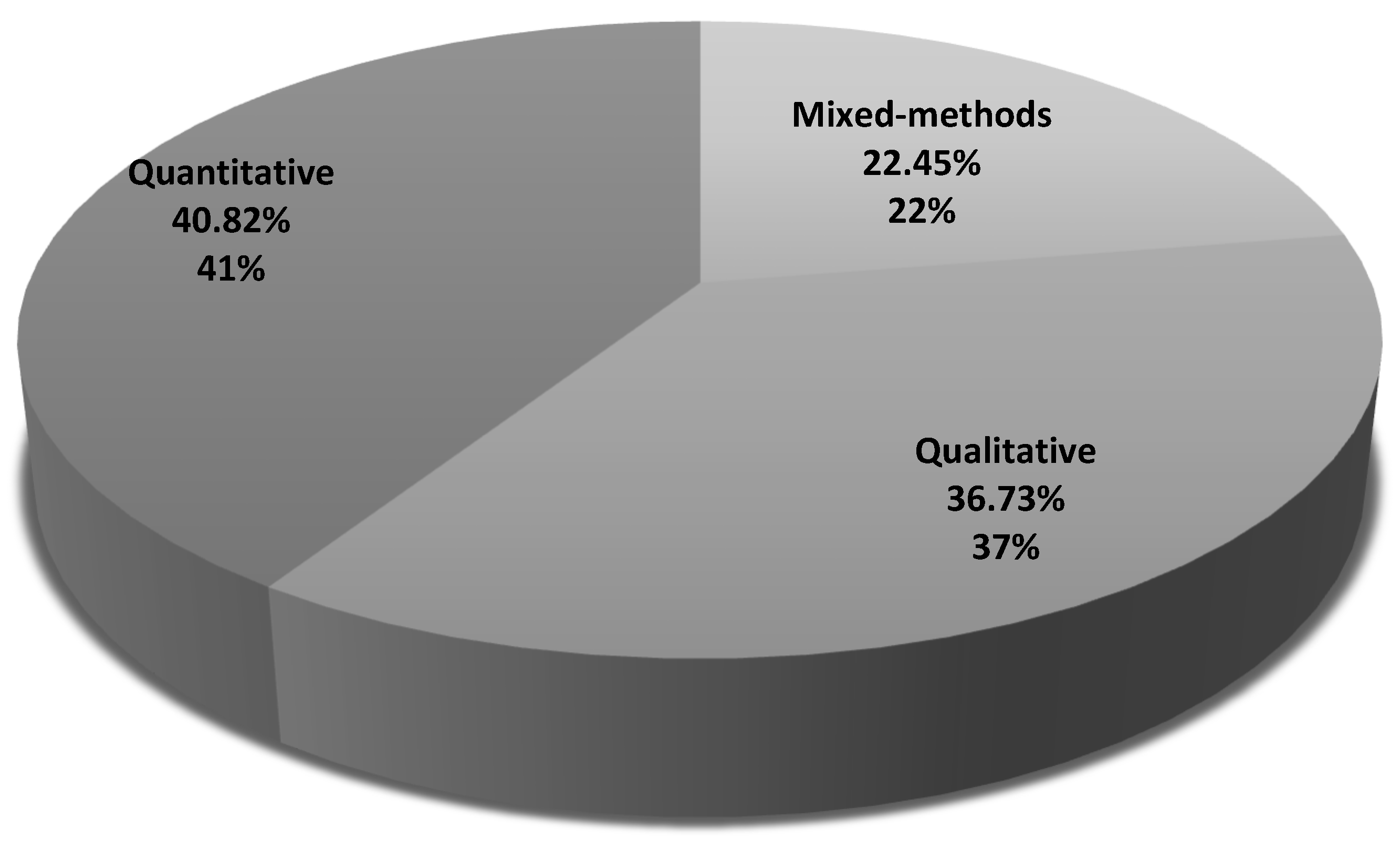

| Data Tabulation and Visualization | Organized study information into data extraction tables. Visualization tools were chosen based on the data types: histograms for frequency distributions, pie charts for comparison between trends and tables. These visualizations were selected to provide clear and intuitive representations of both qualitative and quantitative data, enhancing the understanding of complex relationships between variables. |

| Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis | Thematic analysis was used for qualitative data to identify common themes, while narrative synthesis was applied to non-quantifiable findings. For quantitative data, meta-analysis techniques were employed where appropriate. |

| Heterogeneity Analysis | Subgroup analyses were conducted based on factors such as industry sector, geographical region, and SME size to explore differences across studies. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic, with values above 50% indicating significant heterogeneity, prompting random-effects models. Thresholds for acceptable heterogeneity were defined in line with PRISMA guidelines. |

2.10. Reporting Bias Assessment

2.11. Certainity Assessment

3. Results

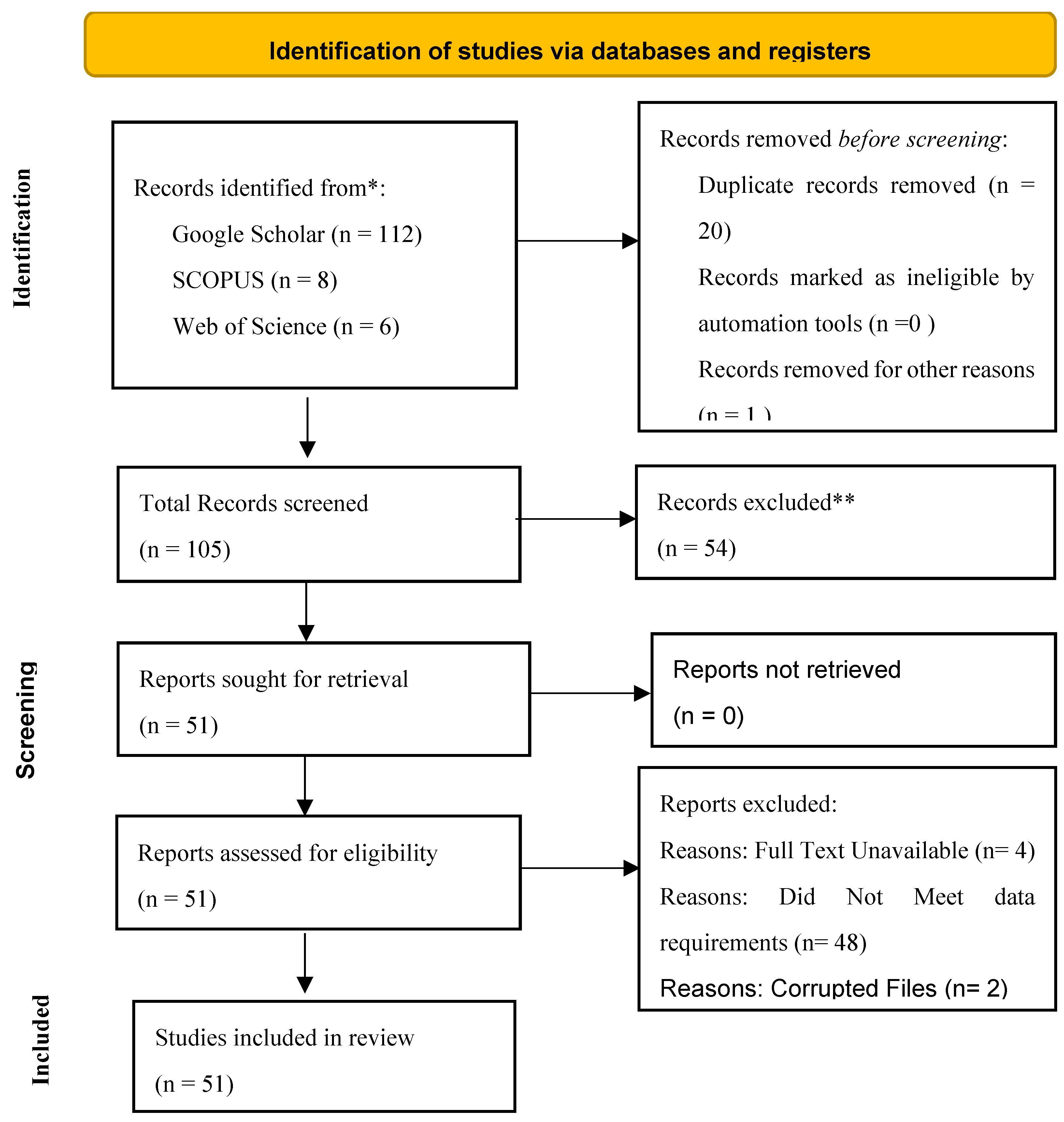

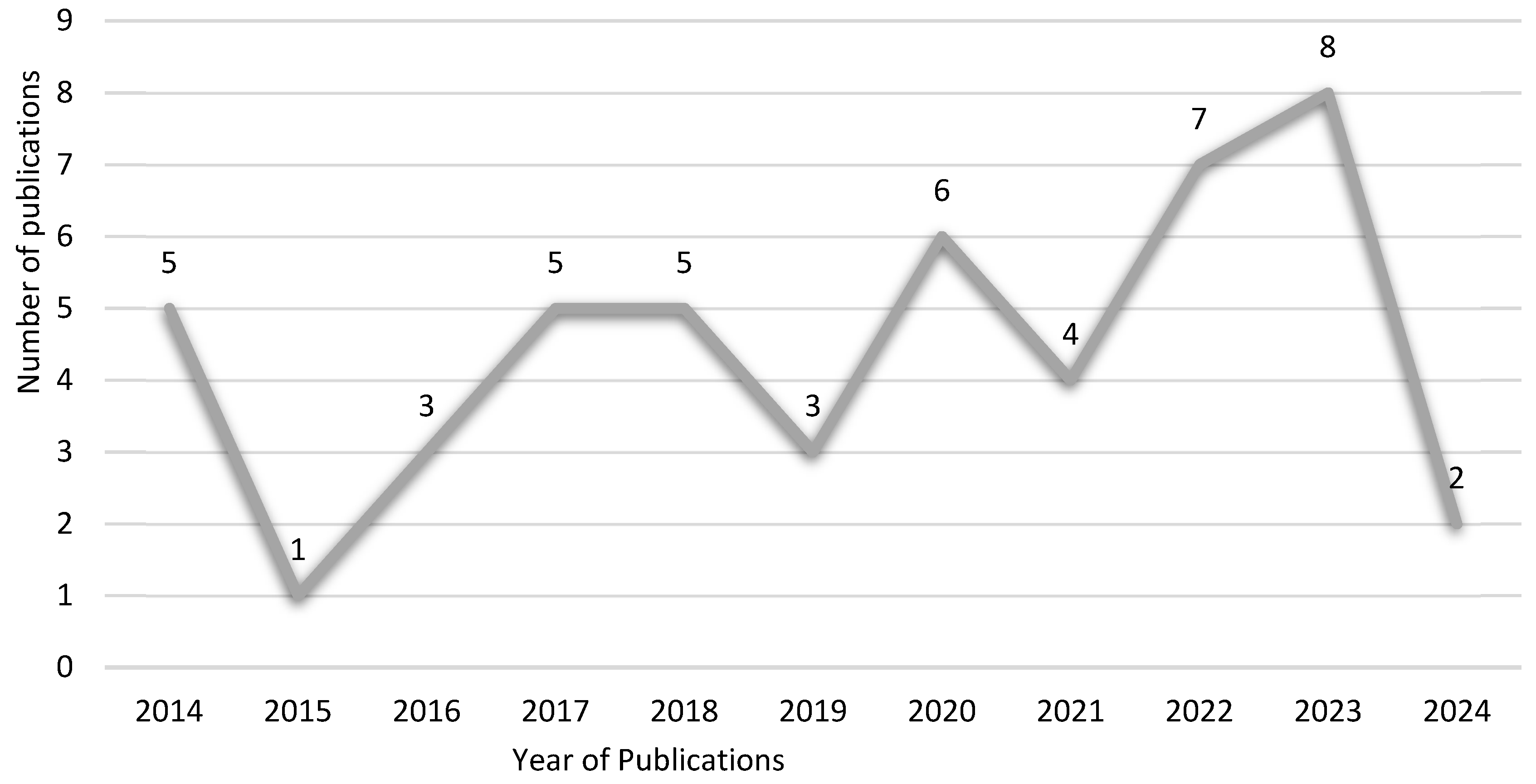

3.1. Results of Study Selection

3.2. Eligible Studies Attributes

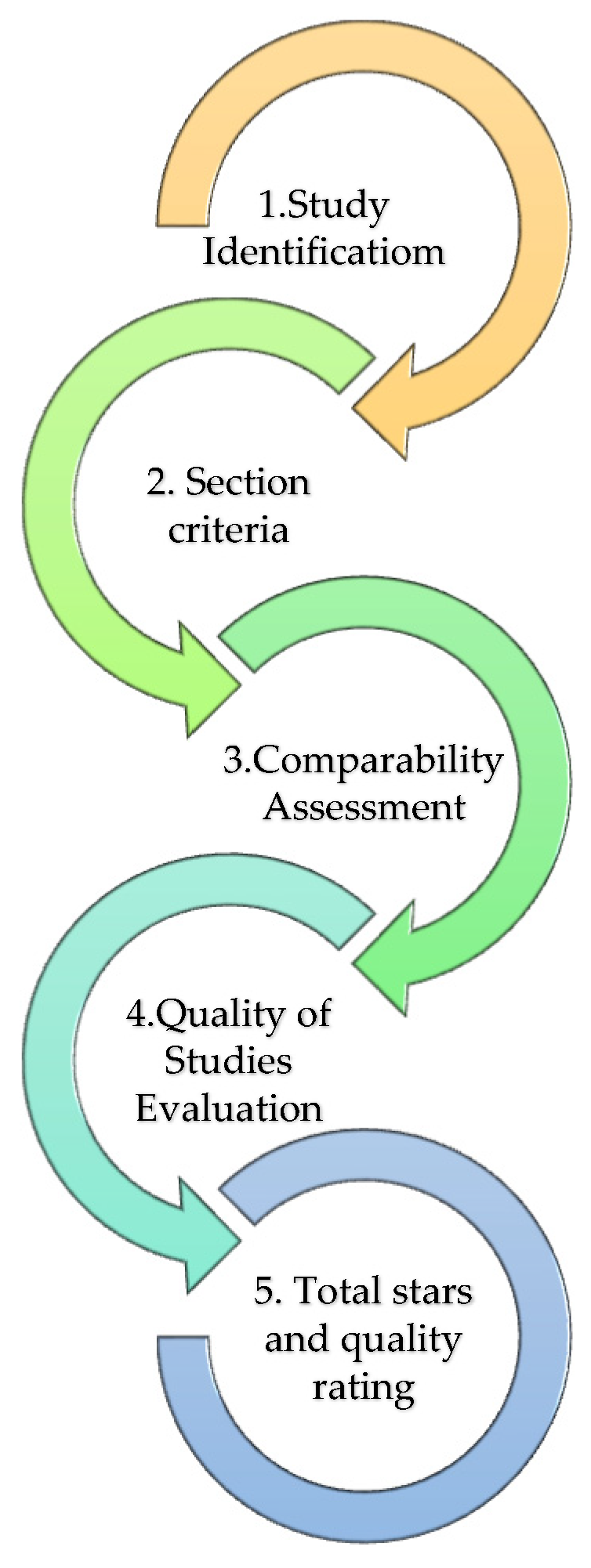

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

| Study ID | Selection (0-4 stars) | Comparability (0-2 stars) | Quality of Studies (0-3 stars) | Total Stars | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [25,26,62,65] | ★★ | ★★ | ★ | 5 | Low Quality |

| [22,28,29,34] | ★★★ | ★★★ | 6 | Moderate Quality |

|

| [23,32,47,56,63,64,73] | ★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | 7 | High Quality |

| [24,30,31,36,40,41,43,44] | ★★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | 8 | High Quality |

| [27,37,38,39,42,45,46,52,53,54,59,60,67,71] | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9 | High Quality |

3.5. Results of Syntheses

3.5.1. Study Characteristics and Bias Assessment

3.5.2. Statistical Synthesis Results

3.6. Reporting Biases

3.7. Certainty of Evidence

4. Findings and Recommendations

4.1. Key Findings and Strategic Implications for Business Leaders

| Porter’s Five Forces | Key Findings | Subcategories | Strategic Drivers | Barriers | Opportunities | Strategic Implications for Business Leaders | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry Rivalry | SMEs utilizing differentiation and innovation outperform competitors in competitive markets. | Product Differentiation | Focus on developing unique products/services that offer value to customers. | High competition and market saturation. | Unique offerings can enhance customer loyalty and market share. | Leaders should prioritize continuous innovation and differentiation to remain competitive in high-rivalry industries. | Increased market share, improved brand positioning. |

| Service Innovation | Implement new customer service models or delivery channels to distinguish from competitors. | Limited resources for innovation. | Improved customer satisfaction and retention through superior service. | Invest in service innovations to meet evolving consumer needs and improve the customer experience. | Enhanced customer satisfaction, reduced churn. | ||

| Competitive Pricing | Implement competitive pricing strategies to drive market penetration. | Cost constraints, price wars. | Attract new customers, increase sales volumes. | Leaders should balance pricing with value creation to avoid price wars that can erode profitability. | Sustainable sales growth, price elasticity. | ||

| Threat of New Entrants | Cost leadership helps SMEs create jobs, improve performance, and maintain competitive pricing. | Cost Efficiency | Streamline operations to reduce costs and improve pricing strategies. | High capital requirements, economies of scale. | Low-cost models can act as entry barriers for new competitors. | Focus on cost optimization strategies to protect market share from new entrants. | Improved operational efficiency, lower costs. |

| Barriers to Entry | Invest in proprietary technologies or exclusive partnerships to create barriers for new entrants. | Regulatory hurdles, high capital investments. | Exclusive relationships and proprietary technologies create defensible market positions. | Leaders should strengthen barriers through innovation, intellectual property, and strategic partnerships. | Reduced vulnerability to new competitors. | ||

| Brand Loyalty | Enhance brand equity and customer loyalty to make it harder for new entrants to capture market share. | Difficulty in building brand identity. | Established brands have more control over market dynamics and customer retention. | Strengthen brand positioning through consistent quality and customer engagement. | Increased customer retention, lower acquisition costs. | ||

| Bargaining Power of Suppliers | Digital transformation enhances SME performance by improving productivity and customer experience. | Supply Chain Digitalization | Implement digital tools like ERP and SCM to enhance supply chain visibility and efficiency. | Resistance to change, high implementation costs. | Digital tools can streamline operations and improve supplier relationships. | Invest in digital supply chain solutions to reduce supplier dependency and improve operational resilience. | Streamlined operations, better supplier negotiations. |

| Supplier Relationship Management | Develop strategic partnerships with key suppliers to secure favorable terms and reliable supply. | Supplier dominance in key sectors. | Strong partnerships can lead to better pricing and priority supply. | Foster long-term supplier relationships through collaborative strategies and joint ventures. | Improved supply chain resilience, cost savings. | ||

| Bargaining Power of Buyers | Financial literacy improves SME sustainability and competitive advantage by enabling better decision-making. | Financial Management | Strengthen financial literacy and management to enhance decision-making and profitability. | Lack of access to financial education. | Improved financial management helps in strategic pricing and negotiations with buyers. | Leaders should invest in financial literacy programs for their teams to enhance competitive positioning. | Stronger financial performance, optimized pricing strategies. |

| Customer Relationship Management | Implement AI-driven CRM systems to enhance customer engagement and predict buyer needs. | Complexity of implementing AI systems. | AI-driven insights can improve customer targeting and retention. | Invest in AI technologies to better understand customer preferences and drive loyalty. | Enhanced customer retention, personalized experiences. | ||

| Threat of Substitutes | Differentiation and cost leadership improve market performance, especially in niche markets like Bali’s SMEs. | Product Innovation | Focus on continuous product innovation to stay ahead of substitutes. | High cost of innovation. | Constant product improvements reduce the threat of substitutes. | Leaders should drive R&D efforts to maintain a competitive edge over substitutes. | Increased market share, continuous product lifecycle. |

| Market Research | Conduct regular market research to stay informed of emerging substitutes and market shifts. | Difficulty in tracking market changes in real-time. | Proactive responses to market shifts can reduce the impact of substitutes. | Establish a continuous market research system to monitor competitor activities and substitute trends. | Early identification of market shifts, proactive strategy adjustment. | ||

| Strategic Opportunities Across Forces | Each of Porter’s Five Forces presents both challenges and opportunities for SMEs, depending on the industry context. | - | Leaders must track specific metrics and KPIs to make data-driven decisions. | Resource limitations, fast-changing environments. | Data-driven strategies enable rapid responses to competitive pressures. | Implement KPIs for continuous improvement, focusing on areas such as cost efficiency, customer engagement, and innovation. | Improved agility, better decision-making, stronger market positioning. |

4.2. Decision-Making Framework for Implementation

| Porter’s Force | Key Decision Points | Sub-Decision Points | Technologies to Implement | Evaluation Metrics | Risks to Consider | Strategic Benefits | Long-term Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry Rivalry | Differentiation vs. Cost Leadership | Should SMEs prioritize innovation and differentiation or reduce costs to stay competitive? | AI-driven product customization, digital marketing platforms, ERP systems for cost optimization. | Customer engagement, cost-per-unit, market share. | High cost of technology adoption, risk of overspending on innovation. | Differentiation builds customer loyalty, while cost leadership reduces operational expenses. | Enhanced competitive edge, sustained market position. |

| Product Innovation vs. Process Innovation | Should the focus be on innovating products or optimizing business processes? | Cloud-based R&D systems for product innovation, AI for process automation. | Product development time, process efficiency, time-to-market. | Risk of focusing too much on one area, neglecting other business operations. | Product innovation meets evolving customer needs; process optimization increases efficiency. | Higher profitability and long-term competitiveness. | |

| Threat of New Entrants | Cost Leadership vs. Barriers to Entry | Should SMEs focus on building cost leadership or strengthening barriers to entry through innovation? | AI-driven process automation, blockchain for secure transactions, IoT-based operational efficiency. | Production costs, market entry rates, customer acquisition cost (CAC). | High initial investments in automation and technology. | Cost leadership and innovation discourage new entrants. | Market position security, increased efficiency, lower customer churn. |

| Pricing Strategy vs. Differentiation | Should SMEs focus on lowering prices or differentiating their products to maintain market share? | Dynamic pricing algorithms, CRM systems for personalized marketing. | Pricing elasticity, customer retention rate, sales growth. | Price wars can erode margins if not managed effectively. | Differentiation strengthens brand loyalty while dynamic pricing optimizes revenue streams. | Reduced threat from new competitors, increased customer loyalty. | |

| Bargaining Power of Suppliers | Supply Chain Digitization vs. Supplier Diversification | Should SMEs digitize supply chains or diversify suppliers to reduce supplier power? | AI-driven supply chain management, blockchain for supplier transparency. | Supplier concentration, supply chain efficiency, procurement costs. | Supply chain disruptions, high cost of digitization. | Digital supply chains reduce dependency and increase transparency. | Better supplier relationships, lower costs, increased bargaining power. |

| Long-term Contracts vs. Flexible Supplier Relationships | Should SMEs lock in long-term contracts with suppliers or maintain flexible relationships? | Contract management software, ERP systems for supplier management. | Supplier switching costs, contract performance, supplier dependency. | Risk of inflexible contracts that limit responsiveness to market changes. | Long-term contracts ensure price stability, flexible relationships allow for adaptability. | Enhanced supplier relationships and supply chain resilience. | |

| Bargaining Power of Buyers | Value Creation vs. Price Sensitivity | Should SMEs focus on creating more value or managing buyer price sensitivity? | AI-powered CRM for personalized customer experiences, cloud-based data analytics for market research. | Customer satisfaction scores (CSAT), repeat purchase rates, average order value (AOV). | Over-reliance on a few large buyers can lead to price pressures. | Value creation through innovation strengthens customer loyalty and mitigates buyer power. | Increased customer lifetime value, reduced reliance on price cuts. |

| Customization vs. Standardization | Should SMEs offer highly customized solutions or standardize offerings to appeal to a broader audience? | AI-driven product customization platforms, ERP for standardized product offerings. | Customization lead times, customer satisfaction, operational efficiency. | Risk of overcomplicating operations with too much customization. | Customization increases customer satisfaction, while standardization reduces costs. | Improved customer engagement and profitability. | |

| Threat of Substitutes | Product Development vs. Market Penetration | Should SMEs invest in developing new products or increase market penetration for existing offerings? | AI-driven market research for product development, digital marketing for market expansion. | Rate of product substitution, market share growth, innovation rate. | High R&D costs can reduce short-term profitability. | Product development reduces the threat of substitutes; market penetration increases brand visibility. | Long-term market expansion, reduced risk of losing customers to substitutes. |

| Niche Markets vs. Broad Market Focus | Should SMEs target niche markets to avoid substitutes or expand offerings for a broad market appeal? | AI-powered customer segmentation, data analytics for market targeting. | Market share in niche markets, customer acquisition cost (CAC), product uniqueness. | Focusing too much on niche markets may limit growth potential. | Niche markets reduce exposure to substitute products. | Greater customer loyalty in niche markets, higher profitability in targeted segments. |

4.3. Best Practices for Successful Implementation of Porter’s Five Forces in SMEs

4.4. Metrics and KPIs for Measuring Perfomance

4.5. How Porter’s Five Forces Shape Competitive Dynamics for SMEs in Various Sectors

4.6. Real Case Studies and How They Relate to Proposed Systematic Review

| Case Study | Industry | Application of Porter’s Five Forces | Strategic Improvements | Challenges & Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [28] | Manufacturing | Applied Porter’s Five Forces alongside the 9Ps of marketing mix to assess competition, pricing strategies, and distribution. | Enhanced competitiveness, improved market strategies, stronger supplier relationships, and expanded distribution channels. | Overcame price pressures through enhanced distribution but faced challenges with balancing warranty costs and competitive pricing strategies. |

| [68] | Retail & Manufacturing | Evaluated supplier power through supplier relationships’ impact on cost and quality. Assessed buyer power based on bargaining strength. | Strong supplier relationships reduced cost pressures and improved product quality. | High buyer power meant pricing was heavily influenced by buyers, demanding stringent quality controls and negotiations to maintain profitability. |

| [74] | Manufacturing | Intense rivalry, focusing on low-cost strategies and reactive marketing practices. | Managed to maintain market share with low-cost strategies. | Marketing practices were reactive, limiting the firm’s ability to innovate, and creating a dependency on low-cost strategies that restricted growth opportunities. |

| [75] | Culinary Industry | High competition among existing firms, necessitating product differentiation. | Differentiation in product presentation and services like delivery increased brand uniqueness. | Faced high pressure from competitors with similar offerings, forcing the firm to continuously adapt its services to maintain a competitive edge. |

| [76] | Food Manufacturing | Assessed buyer power based on strength in price negotiation. Evaluated threat of substitutes impacting pricing and competition. | Buyer power drove consistent improvements in quality and forced price competitiveness. | Threat from substitutes increased, requiring ongoing innovation in product offerings and pricing strategies to avoid loss of market share to alternatives. |

| [77] | Medical Equipment | Analyzed competitive environment; Five Forces were indirectly applied. Focused on market dynamics and competitive pressures. | Improved performance through frequent innovation and business model redesigns. | Constant market shifts required continuous adaptation, challenging the company to stay ahead in terms of product development and technology integration. |

| [78] | Clothing Industry | Buyer bargaining power increased due to the rise of online platforms, impacting pricing. | Shift toward e-commerce platforms improved sales reach and online presence. | Sales declined from 2017-2019 due to technological advancements and intense online competition, requiring a realignment of marketing and sales strategies. |

| [79] | Ceramic Manufacturing | Analyzed competitive forces, focusing on buyer and supplier power and industry trends. | Strengthened supplier negotiations and improved product variety to meet market trends. | Faced high pressure from buyers demanding cheaper, colorful products. Innovation was driven by the need to reduce costs and address short product lifecycles. |

4.7. Roadmap for SMEs Businesses and Policy Recommendations

| Industry | Competitive Force | Roadmap Stage | Subcategories | Strategic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telecommunications | Industry Rivalry | Assessment | Market saturation, technological advancements | SMEs in this industry must differentiate through innovation and adopt digital platforms to manage high competition. |

| Threat of New Entrants | Strategy Development | Capital requirements, regulatory barriers | Invest in advanced technologies and develop unique service models to maintain a competitive edge against new market entrants. | |

| Bargaining Power of Suppliers | Planning | Dependence on key suppliers, digital infrastructure | Prioritize building relationships with multiple suppliers and reduce dependency on high-power providers. | |

| Bargaining Power of Buyers | Implementation | Price sensitivity, contract lengths | Develop personalized services and flexible pricing to retain customers in the face of high buyer power. | |

| Threat of Substitutes | Monitoring | Switching costs, availability of alternative technologies | Continuously innovate service offerings to reduce the threat of substitutes in the digital and communication services sector. | |

| Retail | Industry Rivalry | Assessment | High competition, market trends, customer loyalty | Constantly update product lines and enhance customer experience to stay ahead of rivals. |

| Threat of New Entrants | Strategy Development | Low barriers to entry, online retail expansion | Utilize brand differentiation and develop omnichannel strategies to outperform new entrants in both physical and online markets. | |

| Bargaining Power of Suppliers | Planning | Supplier diversity, bulk purchasing | Negotiate long-term contracts and optimize supply chain management to reduce supplier power. | |

| Bargaining Power of Buyers | Implementation | Customer satisfaction, price sensitivity | Use data analytics to understand buyer preferences and offer competitive pricing or loyalty programs to mitigate buyer power. | |

| Threat of Substitutes | Monitoring | Availability of alternative products, shifting consumer trends | Foster product innovation and invest in customer engagement to minimize the risk of substitute products overtaking market share. | |

| Manufacturing | Industry Rivalry | Assessment | Cost structures, production efficiency | Focus on operational excellence and cost leadership to maintain competitiveness in a high-rivalry market. |

| Threat of New Entrants | Strategy Development | High capital investment, specialized machinery | Leverage economies of scale and patents to create significant entry barriers for new competitors. | |

| Bargaining Power of Suppliers | Planning | Raw material dependency, logistical challenges | Diversify supplier base and develop strong contractual terms to limit supplier power. | |

| Bargaining Power of Buyers | Implementation | Customization demands, bulk orders | Offer customizable solutions or bulk pricing options to balance buyer power and ensure profitability. | |

| Threat of Substitutes | Monitoring | Innovations in product alternatives | Stay updated with industry innovations and continuously improve product quality to reduce the appeal of substitute products. | |

| Healthcare | Industry Rivalry | Assessment | Regulatory changes, healthcare demand | Differentiate through service quality and technological integration to remain competitive in a highly regulated environment. |

| Threat of New Entrants | Strategy Development | Healthcare standards, entry regulations | Innovate patient care technologies and adhere to stringent regulations to build competitive barriers for new entrants. | |

| Bargaining Power of Suppliers | Planning | Supplier concentration, critical medical equipment supplies | Develop partnerships with multiple suppliers and engage in long-term contracts to minimize the risk of supply chain disruptions. | |

| Bargaining Power of Buyers | Implementation | Patient service quality, price sensitivity | Enhance the patient experience and offer diverse payment structures to cater to buyer expectations and reduce buyer power. | |

| Threat of Substitutes | Monitoring | Technological advancements in treatment alternatives | Continuously invest in R&D and treatment innovation to stay ahead of emerging substitute technologies. | |

| Tourism | Industry Rivalry | Assessment | Seasonal demand fluctuations, customer experiences | Improve customer service, differentiate offerings, and leverage local experiences to stand out in a crowded market. |

| Threat of New Entrants | Strategy Development | Low capital requirements, increased tourism demand | Establish niche tourism services or exclusive travel experiences to reduce the impact of new entrants. | |

| Bargaining Power of Suppliers | Planning | Hospitality industry supply chains, service costs | Build strong partnerships with local suppliers and use exclusive contracts to manage costs effectively. | |

| Bargaining Power of Buyers | Implementation | Customer loyalty, pricing expectations | Offer tailored vacation packages and experiences to increase customer loyalty and mitigate the power of price-sensitive buyers. | |

| Threat of Substitutes | Monitoring | Alternative travel services, online travel agencies | Continuously enhance service quality and explore new tourism niches to reduce the impact of substitutes like Airbnb or low-cost travel agencies. | |

| Fishing Industry | Industry Rivalry | Assessment | Fish stock depletion, environmental regulations | Implement sustainable fishing practices and environmentally-friendly operations to gain a competitive advantage. |

| Threat of New Entrants | Strategy Development | Sustainability barriers, high equipment costs | Create entry barriers through sustainability certifications and proprietary technology. | |

| Bargaining Power of Suppliers | Planning | Fishing gear suppliers, licensing | Diversify sourcing and build long-term relationships with suppliers to manage costs effectively. | |

| Bargaining Power of Buyers | Implementation | Buyer preference for sustainability, price elasticity | Promote sustainable fishing to attract environmentally-conscious buyers and establish premium pricing. | |

| Threat of Substitutes | Monitoring | Alternative protein sources, aquaculture competition | Innovate within product lines (e.g., new seafood products) to stay ahead of emerging substitutes like plant-based seafood alternatives or farmed fish. | |

| Renewable Energy | Industry Rivalry | Assessment | Energy production technology advancements, government policies | Focus on innovation and partnerships to stay competitive in the fast-growing renewable energy sector. |

| Threat of New Entrants | Strategy Development | Low capital barriers, increasing demand for renewable energy | Build strong relationships with government and private stakeholders to maintain entry barriers through policy or patents. | |

| Bargaining Power of Suppliers | Planning | Solar panel and turbine technology suppliers | Reduce dependency on key suppliers by investing in in-house technology or diversifying supplier base. | |

| Bargaining Power of Buyers | Implementation | Government tenders, corporate energy buyers | Tailor energy production plans to meet corporate sustainability needs and government tenders. | |

| Threat of Substitutes | Monitoring | Fossil fuel alternatives, energy storage solutions | Invest in energy storage technologies to complement renewable energy offerings and reduce the threat of fossil fuel substitutes. |

- RQ1: How does the bargaining power of suppliers impact the performance of SMEs in various industries?

- RQ2: What is the effect of buyer bargaining power on the competitive positioning and financial performance of SMEs?

- RQ3: How do threats from substitute products or services influence innovation and strategic decisions in SMEs?

- RQ4: To what extent do barriers to entry affect the growth and sustainability of SMEs in competitive markets?

- RQ5: How does competitive rivalry within the Information Technology (IT) sector influence the strategic responses and performance outcomes of SMEs?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. Kraus, P. Jones, N. Kailer, A. Weinmann, N. C. Banegas, and N. R. Tierno, “Digital Transformation: an Overview of the Current State of the Art of Research,” SAGE Open, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 1–15, 2021. Available: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/21582440211047576. [CrossRef]

- S. Das, A. Kundu, and A. Bhattacharya, “Technology Adaptation and Survival of SMEs: A Longitudinal Study of Developing Countries,” Technology Innovation Management Review, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 64–72, Jun. 2020. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1369. [CrossRef]

- C. D. Beaumont, D. Berry, and J. Ricketts, “Technology Has Empowered the Consumer, but Marketing Communications Need to Catch-Up: An Approach to Fast-Forward the Future,” Businesses, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 246–272, Jun. 2022. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-7116/2/2/17. [CrossRef]

- L. Blackmore, “Porter’s Five Forces (2024): the Definitive Overview (+ Examples),” Cascade, Dec. 05, 2023. Available: https://www.cascade.app/blog/porters-5-forces.

- W. Kenton, “Understanding the Six Forces Model,” Investopedia, Jul. 05, 2021. Available: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/six-forces-model.asp.

- Lucidity, “Introduction to the Six Forces Model | Resources | Get Lucidity,” getlucidity.com, 2022. Available: https://getlucidity.com/strategy-resources/introduction-to-the-six-forces-model/.

- Turan Paksoy, Mehmet Akif Gunduz, and S. Demir, “Overall competitiveness efficiency: A quantitative approach to the five forces model,” Computers & Industrial Engineering, vol. 182, p. 109422, 2023. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360835223004461. [CrossRef]

- A. Goyal, “A Critical Analysis of Porter’s 5 Forces Model of Competitive Advantage,” ResearchGate, Jul. 2020. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348550277_A_Critical_Analysis_of_Porter.

- C. Masinde Indiatsy, M. Mwangi, E. Mandere, J. Miroga Bichanga, and E. Gongera, “The Application of Porter’s Five Forces Model on Organization Performance: A Case of Cooperative Bank of Kenya Ltd.,” Online), vol. 6, no. 16, 2014, Available: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234625548.pdf.

- S. Avgeropoulos and J. McGee, “Substitute Products,” Wiley Encyclopedia of Management, vol. 12, pp. 1–3, Jan. 2015. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280238256_Substitute_Products. [CrossRef]

- S. Khan, “A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR INTENSITY OF RIVALRY,” Sep. 2015. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317544139_A_CONCEPTUAL_FRAMEWORK_FOR_INTENSITY_OF_RIVALRY.

- N. Milstein, Y. Striet, M. Lavidor, D. Anaki, and I. Gordon, “Rivalry and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Organizational Psychology Review, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 204138662210821, Feb. 2022. Available: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/20413866221082128?casa_token=rK2kDaJ9xxgAAAAA:mgdLStPICetCz19s0yjlb1R2D0OUeImJaXacNVQ8t2QHgwBiZeNWgKkz9YV3KqwFFDiRl05Z133Y. [CrossRef]

- E. Parviziomran and V. Elliot, “The effects of bargaining power on trade credit in a supply network,” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, vol. 29, no. 1, p. 100818, Jan. 2023. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S147840922300002X?ref=pdf_download&fr=RR-2&rr=8c07c547fff60566. [CrossRef]

- F. Takacs, D. Brunner, and K. Frankenberger, “Barriers to a circular economy in small- and medium-sized enterprises and their integration in a sustainable strategic management framework,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 362, p. 132227, Aug. 2022. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652622018327. [CrossRef]

- K. Uhlenbruck, M. Hughes-Morgan, M. A. Hitt, W. J. Ferrier, and R. Brymer, “Rivals’ reactions to mergers and acquisitions,” Strategic Organization, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 40–66, Jul. 2016. Available: https://epublications.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1266&context=mgmt_fac. [CrossRef]

- D. Plekhanov, H. Franke, and T. H. Netland, “Digital transformation: A review and research agenda,” European Management Journal, vol. 41, no. 6, Sep. 2022, Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0263237322001219. [Accessed: Sep. 09, 2024].

- W. Cho, J. F. Ke, and C. Han, “An Empirical Examination of the Use of Bargaining Power and Its Impacts on Supply Chain Financial Performance,” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, vol. 25, no. 4, p. 100550, Oct. 2019. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1478409218303169. [CrossRef]

- H. Badgujar, “Suppliers Bargaining Power | Porter’s Five Forces Analysis,” MaRS Startup Toolkit, 2019. Available: https://learn.marsdd.com/article/bargaining-power-of-suppliers-porters-five-forces/.

- C. H. Glock and T. Kim, “The effect of forward integration on a single-vendor–multi-retailer supply chain under retailer competition,” International Journal of Production Economics, vol. 164, pp. 179–192, Jun. 2015. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.03.009. [CrossRef]

- M. Larry, S. Luis, and F. Johnson, “The 5 Competitive Forces Framework in a technology mediated environment. Do these forces still hold in the industry of the 21 st century?” 2014. Available: https://essay.utwente.nl/66196/1/Johnson_BA_MB.pdf.

- P. C. Verhoef et al., “Digital transformation: a Multidisciplinary Reflection and Research Agenda,” Journal of Business Research, vol. 122, no. 122, pp. 889–901, Jan. 2021. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0148296319305478. [Accessed: Sep. 09, 2024]. [CrossRef]

- P.E. J. Jaya and N. N. Yuliarmi, “FACTORS INFLUENCING COMPETITIVENESS OF SMALL AND MEDIUM INDUSTRY OF BALI: PORTER’S FIVE FORCES ANALYSIS,” Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, vol. 89, no. 5, pp. 45–54, May 2019, [Accessed: Sep. 08, 2024]. [CrossRef]

- J. Jaroslava Kádárová, L. Lachvajderová, and D. Sukopová, “Impact of Digitalization on SME Performance of the EU27: Panel Data Analysis,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 13, pp. 9973–9973, Jun. 2023. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/15/13/9973. [Accessed: Sep. 08, 2024]. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Cravo and C. Piza, “The impact of business-support services on firm performance: a meta-analysis,” Small Business Economics, vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 753–770, Jun. 2018. Available: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11187-018-0065-x. [Accessed: Sep. 08, 2024]. [CrossRef]

- P. Mugo, “PORTER’S FIVE FORCES INFLUENCE ON COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE IN TELECOMMUNICATION INDUSTRY IN KENYA,” European Journal of Business and Strategic Management, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 30, Sep. 2020. Available: https://www.iprjb.org/journals/index.php/EJBSM/article/view/1140. [Accessed: Sep. 08, 2024]. [CrossRef]

- N. N. O’Hara, L. E. Nophale, L. M. O’Hara, C. A. Marra, and J. M. Spiegel, “Tuberculosis testing for healthcare workers in South Africa: A health service analysis using Porter’s Five Forces Framework,” International Journal of Healthcare Management, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 49–56, Jan. 2017. Available: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/20479700.2016.1268814. [Accessed: Sep. 08, 2024]. [CrossRef]

- P. Lumbanraja, R. Dalimunthe, and B. K. Hasibuan, “Application of Porter’s Five Forces to Improve Competitiveness: Case of Featured SMEs in Medan,” Semantic Scholar, 2019. Available: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Application-of-Porter%E2%80%99s-Five-Forces-to-Improve-Case-Lumbanraja-Dalimunthe/d13b0dceed8406d8fa4c270a6cd41a321fa0bcd9?p2df. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Ulkhaq et al., “Formulating a marketing strategy of SME through a combination of 9Ps of marketing mix and Porter’s five forces,” Proceedings of 2018 International Conference on Big Data Technologies - ICBDT ’18, 2018. Available: https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=3226136. [CrossRef]

- A. Abosede, Julius, K. Obasan, Agbolade, O. Alese, and Johnson, “R M B R Strategic Management and Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) Development: A Review of Literature,” International Review of Management and Business Research, vol. 5, no. 1, 2016, Available: https://www.irmbrjournal.com/papers/1460609149.pdf.

- Pontigga, A. Perri, and F. Casagranda, “The Chinese Online Market: opportunities and challenges for Italian SMEs,” 2020. Available: http://dspace.unive.it/bitstream/handle/10579/16580/871739-1231115.pdf?sequence=2.

- Charles and I. Uford, “COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION OF BUSINESS AND FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE OF AMAZON.COM: A THREE-YEAR PERIOD CRITICAL REVIEW OF EXCEPTIONAL SUCCESS,” European Journal of Business, Economics and Accountancy, vol. 11, no. 2056–6018, 2023, Available: https://www.idpublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Full-Paper-COMPARATIVE-ANALYSIS-AND-EVALUATION-OF-BUSINESS-AND-FINANCIAL-PERFORMANCE-OF-AMAZON.com_.pdf. [Accessed: Sep. 08, 2024].

- L. Zheng and K. Iatridis, “Friends or foes? A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of the relationship between eco-innovation and firm performance,” Business Strategy and the Environment, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Annarelli, C. Battistella, F. Nonino, V. Parida, and E. Pessot, “Literature review on digitalization capabilities: Co-citation. analysis of antecedents, conceptualization and consequences,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 166, p. 120635, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. G. Jadhav, S. V. Gaikwad, and D. Bapat, “A systematic literature review: digital marketing and its impact on SMEs,” Journal of Indian Business Research, vol. 15, no. 1, Feb. 2023. Available: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JIBR-05-2022-0129/full/html. [CrossRef]

- G. Wells et al., “The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses,” www.ohri.ca, 2021. Available: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- R. R. H. Petter, L. M. Resende, P. P. de Andrade Júnior, and D. J. Horst, “Systematic review: an analysis model for measuring the coopetitive performance in horizontal cooperation networks mapping the critical success factors and their variables,” The Annals of Regional Science, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 157–178, Aug. 2014. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00168-014-0622-4. [. [CrossRef]

- M. Nadir, S. Alam, M. Ali, and F. R. Rahim, “Financial Literacy as a Supporting Factor for Sustainability MSMEs in Samarinda City,” Advances in economics, business and management research/Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, no. 2352–5428, pp. 487–502, Jan. 2023. Available: https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/icame-7-22/125987458. [CrossRef]

- G. López-Pérez, I. García-Sánchez, and J. L. Gómez, “A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis of eco-innovation on financial performance: Identifying barriers and drivers,” Business Strategy and The Environment, Aug. 2023. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/bse.3550. [CrossRef]

- R. Graña-Alvarez, E. Lopez-Valeiras, M. Gonzalez-Loureiro, and F. Coronado, “Financial literacy in SMEs: A systematic literature review and a framework for further inquiry,” Journal of Small Business Management, vol. 62, no. 5, pp. 1–50, Apr. 2022. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360093607_Financial_literacy_in_SMEs_A_systematic_literature_review_and_a_framework_for_further_inquiry. [CrossRef]

- L. Kellen, K. Kabii, and G. Kinyua, “Managerial Competencies and Business Continuity: A Review of Literature,” International Journal of Education and Research, vol. 11, no. 2, 2023, Available: https://www.ijern.com/journal/2023/February-2023/06.pdf.

- M. Hossain, “Prospects and challenges of digital marketing - a report on Grey Dhaka,” Handle.net, 2023, doi: ID%2018304041. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/10361/18653.

- M. A. Hajar, A. A. Alkahtani, D. N. Ibrahim, M. R. Darun, M. A. Al-Sharafi, and S. K. Tiong, “The Approach of Value Innovation towards Superior Performance, Competitive Advantage, and Sustainable Growth: A Systematic Literature Review,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 18, p. 10131, Sep. 2021. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/18/10131. [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Gemio, C. Cruz-Cázares, and M. J. Parmentier, “Responsible Innovation in SMEs: A Systematic Literature Review for a Conceptual Model,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 24, p. 10232, Dec. 2020. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/24/10232. [CrossRef]

- Chiripanhura and M. Teweldemedhin, “AGRODEP Working Paper 0021 An Analysis of the Fishing Industry in Namibia: The Structure, Performance, Challenges, and Prospects for Growth and Diversification Blessing Chiripanhura Mogos Teweldemedhin,” 2016. Available: http://www.agrodep.org/sites/default/files/AGRODEPWP0021_0.pdf.

- G. K. Rathnayake and C. N. Wickramasinghe, “Systematic Literature Review on Competitive Strategies in Apparel Industries,” Journal of Business and Technology, vol. 6, no. 2, p. 1, Oct. 2022. Available: https://doi.org/10.4038/jbt.v6i2.85. [CrossRef]

- G. Kinoti, “INFLUENCE OF PORTER’S FIVE FORCES ON THE COMPETITIVENESS OF SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED HARDWARE BUSINESSES IN IMENTI SOUTH SUB-COUNTY, MERU COUNTY, KENYA GEOFFREY KINOTI A THESIS SUBMITTED IN THE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE REQUIREMENTS OF DEGREE OF MASTER IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION OF KENYA METHODIST UNIVERSITY,” 2019. Available: http://repository.kemu.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/123456789/796/Geoffrey%20Kinoti.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Sabihaini and J. Prasetio, “COMPETITIVE STRATEGY AND BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT ON SMEs PERFORMANCE IN YOGYAKARTA, INDONESIA,” International Journal of Management (IJM), vol. 11, no. 8, pp. 1370–1378, 2020. Available: http://eprints.upnyk.ac.id/23677/1/IJM_11_08_125.pdf. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Gatimu and J. Amuhaya, “EFFECT OF COMPETITIVE STRATEGIES ON THE PERFORMANCE OF SMEs IN KIAMBU COUNTY, KENYA,” Journal of Business and Strategic Management, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 69–87, Apr. 2022. Available: https://carijournals.org/journals/index.php/JBSM/article/view/846#:~:text=Findings%3A%20The%20findings%20of%20the,Medium%20Enterprises%20in%20Kiambu%20County. [CrossRef]

- N. Andriyansah, G. Ginting, and A. R. Rahim, “Developing the competitive advantage of small and medium enterprises through an ergo-iconic value approach in Indonesia,” International Journal of Applied Economics Finance and Accounting, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 436–444, Oct. 2023. Available: https://onlineacademicpress.com/index.php/IJAEFA/article/view/1196. [CrossRef]

- M. Karikari Appiah, “A simplified model to enhance SMEs’ investment in renewable energy sources in Ghana,” International Journal of Sustainable Energy Planning and Management, vol. 35, pp. 83–96, Sep. 2022. Available: https://doi.org/10.54337/ijsepm.7223. [CrossRef]

- W. Tongdaeng and C. Mahakanjana, “Thai SMEs’ Response in the Digital Economy Age: A Case Study of Community-Based Tourism Policy Implementation,” Social Sciences, vol. 11, no. 4, p. 180, Apr. 2022. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/11/4/180. [CrossRef]

- M. Pervan, M. Curak, and T. Pavic Kramaric, “The Influence of Industry Characteristics and Dynamic Capabilities on Firms’ Profitability,” International Journal of Financial Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 4, Dec. 2017. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7072/6/1/4. [CrossRef]

- M. Awad and A. A. Amro, “The effect of clustering on competitiveness improvement in Hebron A structural equation modeling analysis,” Emerald Insight, Jul. 2023. Available: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JMTM-12-2016-0181/full/pdf?title=the-effect-of-clustering-on-competitiveness-improvement-in-hebron-a-structural-equation-modeling-analysis. [CrossRef]

- T. Tammi, J. Saastamoinen, and H. Reijonen, “Public procurement as a vehicle of innovation – What does the inverted-U relationship between competition and innovativeness tell us?,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 153, no. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S004016251831028X#:~:text=(2005)%20suggest%20that%20an%20inverted,highest%20level%20of%20innovation%20activity., p. 119922, Apr. 2020, . [CrossRef]

- M. Miyamoto, “Application of competitive forces in the business intelligence of Japanese SMEs,” International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 273–287, Dec. 2014. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277818665_Application_of_competitive_forces_in_the_business_intelligence_of_Japanese_SMEs. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Appiah, B. T. Possumah, N. Ahmat, and N. A. Sanusi, “Do Industry Forces Affect Small and Medium Enterprise’s Investment in Downstream Oil and Gas Sector? Empirical Evidence from Ghana,” Journal of African Business, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 42–60, Apr. 2020. Available: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15228916.2020.1752599. [CrossRef]

- N. N. Kerti Yasa, P. G. Sukaatmadja, H. Rahyuda, and I. G. A. K. Giantari, “Effect of Industry Competıtıon and Entrepreneurıal Company to Implementatıon of Dıfferentıatıon Strategy, SME Performance, and Poverty Allevıatıon,” Asia Pacific Management and Business Application, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 14–27, Aug. 2014. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308086390_Effect_of_Industry_Competition_and_Entrepreneurial_Company_to_Implementation_of_Differentiation_Strategy_SME_Performance_and_Poverty_Alleviation. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Utami and D. C. Lantu, “Development Competitiveness Model for Small-Medium Enterprises among the Creative Industry in Bandung,” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 115, pp. 305–323, Feb. 2014. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042814019867. [CrossRef]

- N. D. Nte and N. K. Omede, “Competitive Intelligence and Resilience of Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Developing Economies,” Jurnal Ekonomi Akuntansi dan Manajemen, vol. 20, no. 2, p. 112, Oct. 2021. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.19184/jeam.v20i2.26653. [CrossRef]

- Y. Christianah Olorunshola, “ScholarWorks Small Business Sustainability Strategies in the Maritime Industry in Lagos, Nigeria,” 2019. Available: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=8212&context=dissertations.

- M. M. Makuthu, “INFLUENCE OF BUSINESS STRATEGIES AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS ON THE PERFORMANCE OF TOP 100 SMEs IN KENYA BY MUEMA, MARK MAKUTHU A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 2016,” 2016. Available: http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/11295/97812/Muema_Influence%20of%20business%20strategies%20and%20information%20systems.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- V. N. Njuguna, “Effects of Generic Strategies on Competitive Advantage: Evidence from SMEEs in Nyahururu, Kenya,” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2015. Available: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2630770. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Leonidou, D. Palihawadana, B. Aykol, and P. Christodoulides, “EXPRESS: Effective Sme Import Strategy: Its Drivers, Moderators, and Outcomes,” Journal of International Marketing, vol. 30, no. 1, p. 1069031X2110642, Nov. 2021. Available: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1069031X211064278. [Accessed: Sep. 08, 2024]. [CrossRef]

- M. Rubio-Andrés, J. Linuesa-Langreo, S. Gutiérrez-Broncano, and Miguel Ángel Sastre-Castillo, “How to improve market performance through competitive strategy and innovation in entrepreneurial SMEs,” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, Mar. 2024. Available: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11365-024-00947-9. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. M. Taneo, D. Hadiwidjojo, Sunaryo, and Sudjatno, “THE ROLES OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN MODERATING THE CORRELATION BETWEEN INNOVATION SPEED AND AND THE COMPETITIVENESS OF FOOD SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES (SMES) IN MALANG, INDONESIA,” Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 42–54, Feb. 2017. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314070338_THE_ROLES_OF_LOCAL_GOVERNMENT_IN_MODERATING_THE_CORRELATION_BETWEEN_INNOVATION_SPEED_AND_AND_THE_COMPETITIVENESS_OF_FOOD_SMALL_AND_MEDIUM-SIZED_ENTERPRISES_SMES_IN_MALANG_INDONESIA. [CrossRef]

- H.-T. Yi, D. Oh, and Fortune Edem Amenuvor, “The effect of SMEs’ dynamic capability on operational capabilities and organisational agility,” South African Journal of Business Management, vol. 54, no. 1, p. 14, 2023, Available: https://sajbm.org/index.php/sajbm/article/view/3696/2547.

- J. W. Ong, H. Ismail, and P. F. Yeap, “Competitive advantage and firm performance: the moderating effect of industry forces,” International Journal of Business Performance Management, vol. 19, no. 4, p. 385, 2018. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328158017_Competitive_advantage_and_firm_performance_The_moderating_effect_of_industry_forces. [CrossRef]

- P. Hove and R. Masocha, “Interaction of Technological Marketing and Porter’s Five Competitive Forces on SME Competitiveness in South Africa,” Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, vol. 5, no. 4, Mar. 2014. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289271694_Interaction_of_Technological_Marketing_and_Porter’s_Five_Competitive_Forces_on_SME_Competitiveness_in_South_Africa. [CrossRef]

- O. Sondakh, B. Christiananta, and L. Ellitan, “Scholars Journal of Economics, Business and Management (SJEBM) Analyzing the Industrial Forces of Food Industry SMEs in Surabaya-Indonesia,” Scholars Journal of Economics, Business and Management (SJEBM), 2018. Available: https://www.saspublishers.com/media/articles/SJEBM_53_158-166_c.pdf. [CrossRef]

- S. Omsa, “Five Competitive Forces Model and the Implementation of Porter’s Generic Strategies to Gain Firm Performances,” Science Journal of Business and Management, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 9, 2021. Available: https://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/article/10.11648/j.sjbm.20170501.12. [CrossRef]

- T. Kipruto Bensecilas, A. Kepha, Ombui, and I. Mike, “Influence of the Porter’s Five Forces Model Strategy on Performance of Selected Telecommunication Companies in Kenya,” International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, vol. 6, no. 10, 2016, Available: https://www.ijsrp.org/research-paper-1016/ijsrp-p5877.pdf.

- S. Min and N. Kim, “Competitive imitation strategy for new product-market success,” Australasian Marketing Journal, vol. 31, no. 2, p. 183933492110479, Oct. 2021. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355431879_Competitive_Imitation_Strategy_for_New_Product-Market_Success. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Hussein, “Application of Strategic Planning Tools and Concepts in SMES in Nairobi CBD,” Usiu.ac.ke, 2015, doi: http://erepo.usiu.ac.ke/11732/2769. Available: https://erepo.usiu.ac.ke/handle/11732/2769.

- M. Mashingaidze, M. Bomani, and E. Derera, “Marketing practices for Small and Medium Enterprises: An exploratory study of manufacturing firms in Zimbabwe,” Journal of Contemporary Management, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 482–507, Jan. 2021. Available: https://doi.org/10.35683/jcm20103.114.]. [CrossRef]

- Apriyanti, “Marketing Strategy Using Porter’s Five Force Model Approach: A Case Study of PT M-150 Indonesia,” Open Access Indonesia Journal of Social Sciences, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 192–198, Apr. 2021. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.37275/oaijss.v4i2.47. [CrossRef]

- W. Fauziah, W. Yusoff, L. Chee Jia, Z. Anim, A. Azizan, and Ramin, “Business Strategy of Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs): A Case Study among selected Chinese SMEs in Malaysia,” 2020. Available: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/42955857.pdf.

- Tafur, “Business model and business model sophistication: a case study in a SME,” Handle.net, 2020, doi: http://hdl.handle.net/10234/191884. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/10234/191884.

- M. Kapurubandara, “A Framework to e-Transform sMEs in developing countries,” The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 1–24, Oct. 2009. Available: https://web.archive.org/web/20170829012222id_/http://www.smmeresearch.co.za/SMME%20Research%20General/Reports/e-Business%20strategies%20for%20SMEs.pdf. [CrossRef]

| Ref | Cites | Year | Contributions | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [22] | 43 | 2014 | Reviews the use of cost leadership, differentiation, and focus strategies by SMEs in Nairobi and their impact on performance. | Provides relevant data on MSEs in a developing economy. | Findings limited to Nairobi and small-scale enterprises. |

| [23] | 2 | 2014 | Examines how Japanese SMEs apply Porter’s Five Forces in business intelligence to improve competitiveness. | Focuses on integration of competitive forces into business intelligence practices. | Limited to Japanese SMEs; may not apply to other cultural contexts. |

| [24] | 152 | 2016 | Provides a comprehensive review of strategic management theories and their relevance to SME growth and sustainability. | Summarizes diverse strategies applicable to SMEs, offering a broad theoretical foundation. | Lacks empirical evidence; more of a theoretical review than practical analysis. |

| [25] | 24 | 2017 | Analyses the competitive forces shaping the Kenyan telecommunications sector using Porter’s model | Applies Porter’s Five Forces to a specific industry, providing actionable insights. | Focuses only on one sector, limiting cross-industry application. |

| [26] | 8 | 2020 | Reviews how technological SMEs use an adapted version of Porter’s Five Forces to enhance the strategic accuracy of their innovations | Offers insights into the strategic management of technology-driven SMEs and innovation. | Focuses on technological SMEs, which may not apply to non-tech sectors |

| [27] | 49 | 2020 | Provides a systematic review of literature on responsible innovation in SMEs and proposes a conceptual model for integrating responsible innovation practices. | Offers a comprehensive overview of responsible innovation and practical implications for SMEs. | Focuses on conceptual models rather than empirical data, which may limit practical application. |

| [28] | 252 | 2021 | Analyses co-citation patterns to review the antecedents, conceptualization, and consequences of digitalization capabilities | Provides a detailed analysis of digitalization research trends and key concepts. | May lack practical applications for SMEs specifically; focuses on academic co-citation patterns. |

| [29] | 13 | 2022 | Reviews and meta-analyses the impact of eco-innovation on firm performance, exploring whether eco-innovation is a friend or foe to business success | Provides a comprehensive analysis of eco-innovation’s effects on firm performance, offering insights into its benefits and challenges. | May not focus specifically on SMEs; broad review could dilute applicability to smaller firms. |

| [30] | 2 | 2022 | Reviews various competitive strategies employed in the apparel industry, including cost leadership, differentiation, and innovation. | Offers insights into strategic practices specific to the apparel sector, providing a focused view on industry-specific strategies | Limited to the apparel industry, which may not apply to other sectors. |

| [31] | 16 | 2023 | Analyses Amazon’s business and financial performance over three years, evaluating factors contributing to its exceptional success. | Provides in-depth analysis of Amazon’s performance, offering valuable insights into its strategic success. | Focuses specifically on Amazon, which may limit generalizability to other companies or industries. |

| [32] | 65 | 2023 | Reviews the impact of digital marketing strategies on SME performance, highlighting key trends and outcomes. | Offers insights into how digital marketing affects SMEs, including benefits and challenges. | Focused on digital marketing; may not address other factors influencing SME performance. |

| [33] | 1 | 2023 | Investigates how financial literacy contributes to the sustainability and performance of MSMEs in Samarinda City. | Highlights the role of financial literacy in enhancing MSME sustainability, offering practical implications for business owners. | Focused on MSMEs in a specific geographic location; may not be generalizable to other areas |

| [34] | 8 | 2023 | Reviews literature on the role of managerial competencies in ensuring business continuity and resilience. | Provides a comprehensive overview of essential managerial skills for business continuity. | May lack specific empirical data; primarily theoretical review |

| Proposed Systematic Review | The review advances the understanding of Porter’s Five Forces in SMEs, offering valuable insights into how these forces affect small enterprises differently from large firms. It also identifies gaps in research, particularly in the impact of digital platforms and e-commerce on SME competitiveness, providing direction for future studies and policy recommendations. | This systematic review offers a comprehensive analysis of competitive forces affecting SMEs and provides practical guidance for leaders to enhance business performance. It also highlights how technological innovation and digital transformation reshape competitive dynamics, offering actionable strategies for SMEs to navigate these challenges. | |||

| Criteria | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Topic | Articles focusing on the impact of Porter’s Five Forces on SMEs performance | Articles that do not focus on the impact of Porter’s Five Forces on SMEs performance |

| Research framework | Articles should include methodology for analyzing the Five Forces on SMEs performance | Articles that do not include a methodology for analyzing the Five Forces on SMEs performance |

| Language | Papers written in English | Papers written in other languages |

| Period | Publications between 2014 and 2024. | Publications outside 2014 and 2024. |

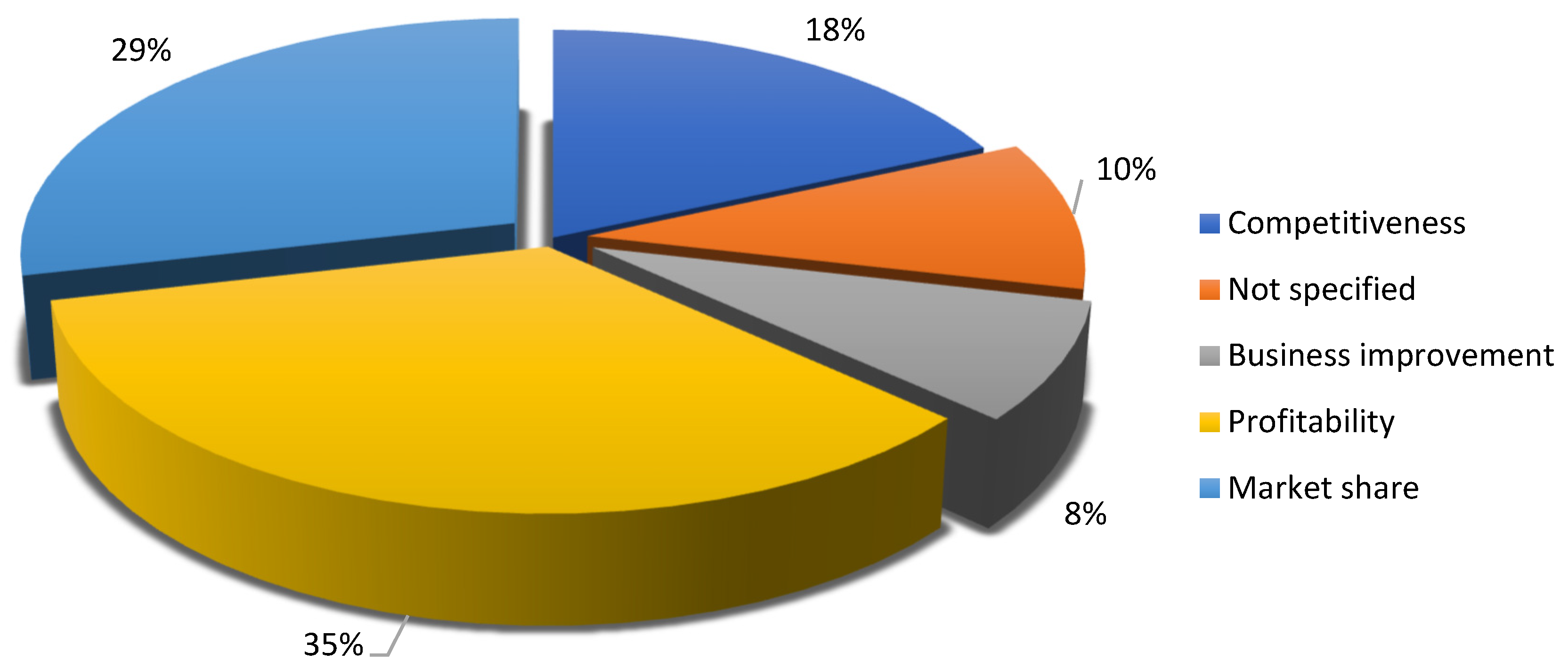

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Profitability | Financial gain and profit margin of the SME |

| Market Share | Total sales in an industry generated by a particular SME |

| Growth Rate | Percentage change in GDP, turnover, or wages from one period to another |

| Innovation | Ability of the SME to introduce new products or services |

| Supplier Concentration | Degree of dependence on a few suppliers (related to Bargaining Power of Suppliers) |

| Supplier Switching Costs | Costs incurred by SMEs when changing suppliers (Bargaining Power of Suppliers) |

| Barriers to Entry | Difficulty for new firms to enter the market (related to Threat of New Entrants) |

| Capital Requirements | Financial investment required to enter the industry (Threat of New Entrants) |

| Product Differentiation | Extent to which products or services differ from competitors (related to Threat of Substitutes) |

| Availability of Substitutes | Presence of alternative products or services in the market (Threat of Substitutes) |

| Competitive Rivalry | Level of competition among existing SMEs in the market (Competitive Rivalry) |

| Number of Competitors | Number of firms operating in the same industry (Competitive Rivalry) |

| Customer Concentration | Degree to which SMEs depend on a few large buyers (Bargaining Power of Buyers) |

| Buyer Price Sensitivity | Extent to which customers are price-sensitive (Bargaining Power of Buyers) |

| Adaptability | Ability to withstand and adjust to environmental changes |

| Sample Size | Number of interviewees, papers analyzed, or companies studied |

| Sample Characteristics | Defining traits of samples used (e.g., SME, employees, CEOs, experts) |

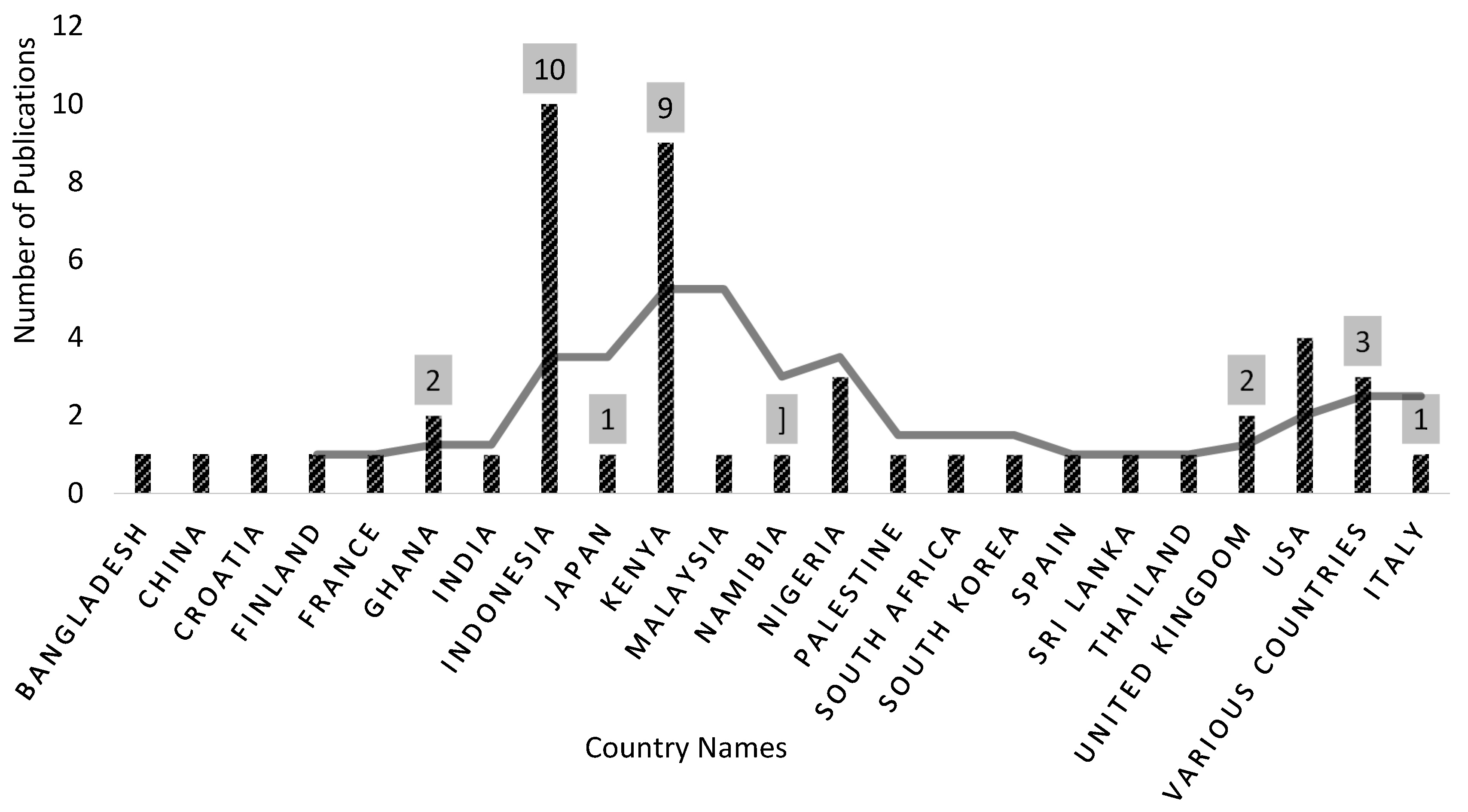

| Geographical Location | Location of where the studies were conducted |

| Economic Context | Status of countries studied (developing or developed) |

| Quality Assessment (QA) | Research Quality Assessment Questions |

|---|---|

| QA1 | Is the research question clearly stated? |

| QA2 | Does the research clearly specify the data collection methods? |

| QA3 | Was the sampling technique appropriate and clearly described and was the sample size sufficient? |

| QA4 | Does the research have a clear research methodology? |

| QA5 | Do the research findings contribute to existing literature on the topic of the impact of porter’s five forces model on SMEs? |

| Published Year | Conference Paper | Dissertation | Journal Article |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 2015 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2016 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 2017 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 2018 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 2019 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 2020 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| 2021 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 2022 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 2023 | 2 | 0 | 8 |

| 2024 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Ref | Competitive Forces | Business Performance | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| [36] | Bargaining power of suppliers | Firm performance, job creation, growth rate, profitability | The study found that digitalization significantly enhances SME performance, particularly in value-added growth and employment, within the EU27, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| [37] | Threat of new entrants | Firm performance, job creation | The study provides the effectiveness of various support programs and highlighting which interventions are most successful in improving SME performance |

| [38] | All Porter’s Five Forces | Employee experience, company recommendations | The study highlights that Porter’s Five Forces model helps managers in the telecommunication sector identify competitive strengths and weaknesses, with a call for further research to integrate additional factors influencing industry performance. |

| [39] | All Porter’s Five Forces | Employee experience, company recommendations | The study reveals that most SMEs in Medan are unaware of the Five Forces Analysis Model and its benefits, highlighting the need for academic support to help SMEs utilize the model to improve competitiveness. |

| [40] | All Porter’s Five Forces | Relationship with partners, Pricing strategy |

The study combines the 9Ps of marketing mix with Porter’s Five Forces to formulate a competitive strategy for SME Gandhis Manes, recommending future research to include SWOT analysis for better strategy formulation. |

| [41] | All Porter’s Five Forces | Employee experience, company recommendations | The paper highlights how SMEs can leverage their flexibility and focus on high-quality goods, particularly in Italy, to succeed in global markets by adapting to globalization trends and utilizing digitalization for competitive advantage. |

| [42] | Industry rivalry |

Continuous excellence, industry leadership |

The paper analyses Amazon’s exceptional business and financial performance over the past three years, highlighting its superior growth, profitability, and strategic advantages compared to Walmart. |

| [43] | Bargaining of suppliers |

Improved financial literacy, business sustainability |

The paper concludes that financial literacy, socialization, and daily accounting systems are critical strategies for enhancing MSME sustainability and competitiveness. |

| [44] | All Porters five forces | Improved financial literacy, business sustainability | Highlights how value innovation complements traditional competitive strategies as outlined in Porter’s Five Forces |

| [45] | All Porter’s Five Forces |

Employee experience, company recommendations |

The paper highlights how digital marketing helps businesses target niche markets, build trust with customers, and grow their reach, but emphasizes the need for improved training and adaptation to platforms like Instagram and TikTok for future success. |

| [46] | All Porter’s Five Forces |

Sustainable Growth |

This paper can serve as a foundational piece for understanding how Porter’s Five Forces model applies to SMEs in different contexts, and it can offer practical insights for enhancing competitiveness in similar settings. |

| [47] | Industry rivalry |

Market share, profitability, growth rate | The paper examines the structure, performance, and challenges of Namibia’s fishery sector, emphasizing the need for balanced value addition, sustainable stock management, market diversification, and improved policy coordination. |

| [48] | All Porter’s Five Forces |

Market share, profitability, growth rate | The study finds that hardware SMEs in Imenti South Sub- County, Meru County, experience significant competitive rivalry and price sensitivity, but the threat of new entrants, bargaining power of buyers and suppliers, and threat of substitute products have limited impact on their competitiveness. |

| [49] | Industry rivalry |

Market share achievement |

Competitive strategies (cost, differentiation, and innovation) significantly improve SME performance in Yogyakarta, while alliance strategy and environmental dynamism do not, and competitive pressure negatively impacts performance. |

| [50] | All Porter’s Five Forces |

Competitive performance |

In Kiambu County, SMEs effectively utilize Porter’s generic strategies, particularly differentiation, which has the strongest positive impact on performance, confirming the strategic practices’ link to superior performance. |

| [51] | All Porter’s Five Forces |

Enhanced competition and innovation | Implementing ergonomic service values (EISV) in SMEs enhances innovation and performance by improving service marketing, product values, and firm positioning, aligning with Porter’s competitive advantage theory. |

| [52] | All Porter’s Five Forces |

Market Response, Managerial Understanding |

The competency analysis of community-based tourism (CBT) using Porter’s Five Forces revealed that market competition, the threat of new entrants, substitutes, and varying bargaining powers of suppliers and customers significantly impact the survival and growth of CBT SMEs, with capital and marketing strategy being crucial for competitive advantage. |

| [53] | Industry rivalry, Bargaining power of buyers | Market Response, Managerial Understanding | The study found that industry characteristics negatively affect firm performance while dynamic capabilities, such as sensing and seizing opportunities, positively impact performance, emphasizing the need for Croatian manufacturing SMEs to adapt and invest in these capabilities. |

| [54] | Porter’s Five Forces, Inverted-U Relationship | Variability in innovation orientation by SME group and competition levels | The study empirically supports the inverted-U relationship between competition and innovation in public procurement, revealing that while low competition increases innovation, high competition decreases it, with variations across different SME groups. |

| [55] | All Porter’s Five Forces |

Competitive pressure, Technological development | The study finds that while IT and business strategies in Japanese SMEs are significantly influenced by primary value chain activities, the Porter’s Five Forces model shows mixed effects on IT strategy, with only threat of new entrants and buyer power positively impacting it. |

| [56] | All Porter’s Five Forces |

High earnings, employment opportunities, improvement in infrastructure, service extension |

The study finds that in Ghana’s downstream oil and gas sector, SMEs’ investment behaviour is influenced by the threat of entry, competitive rivalry, power of suppliers, and power of buyers, but not by the threat of substitutes, aligning with Porter’s Five Forces model. |

| [57] | All Porter’s Five Forces |

Performance improvements, contribution to poverty alleviation | The study concludes that increased industry competition and higher entrepreneurial activity drive SMEs in Bali to implement differentiation strategies, which in turn improve performance and reduce poverty. |

| [58] | Industry rivalry |

Competitiveness includes potential (internal capability, external environment, owner and company characteristics), process (operation and growth strategies), and performance (financial and non-financial). |

The study outlines the dimensions of competitiveness in SMEs—potential, process, and performance—and provides recommendations for enhancing SME competitiveness through passion, innovation, growth strategies, and government support, while emphasizing the role of mediators in providing training and access to resources. |

| [59] | Industry rivalry |

Enhanced business survival, Improved customer service |

The paper identifies ten key issues for small business sustainability beyond five years, including finance, government policy, flexibility, and customer retention, and emphasizes the importance of understanding these challenges and developing strategies to enhance long-term survival. |

| [60] | Threat of new entry |

Enhanced investment strategies, Improved participation in renewable energy sector |

The paper develops a simplified “RBV-Plus 5” model integrating RBV theory and Porter’s 5 Forces to explain SMEs’ investment behaviour in Ghana’s renewable energy sector, highlighting the significant influence of competitive resources and industry forces on investment decisions. |

| [61] | Threat of new entry |

Enhanced competitive advantage, improved productivity |

The study emphasizes that narrowing the gap between business and IT professionals is crucial for SMEs in Kenya to achieve positive growth, as knowledgeable staff and well-implemented business strategies and information systems significantly enhance firm performance. |

| [62] | Industry Rivalry |

Competitive Advantage, Enhanced Financial Performance |

The study highlights how SME importers’ use of dynamic capabilities, both generic and import-specific, enhances import strategy effectiveness, leading to competitive advantages in product differentiation and cost reduction, particularly in volatile global markets, thus improving financial performance. |

| [63] | Industry Rivalry |

Positive correlation between innovation speed and competitiveness; Enhanced by local government roles | The study concludes that innovation speed, supported by local government initiatives, significantly enhances the competitiveness of food SMEs in Malang, leading to higher profitability and productivity in a highly competitive market with short product life cycles. |

| [64] | All Porter’s Five Forces |

Organizational Structure, Entrepreneurial Orientation |

This study demonstrates that while SME dynamic capabilities positively impact non-financial performance in volatile environments, organizational inertia moderates this effect, weakening the relationship with both financial and non-financial outcomes. |

| [65] | Power of Buyers, Power of Suppliers, Threat of Rivalries | Improvement in firm performance based on strategy implementation | The study concludes that differentiation and focus strategies positively impact financial and market performance in the wooden furniture industry, while cost leadership strategy has no significant effect. |

| [66] | All Porter’s Five Forces |

Moderate Performance, High Industry Rivalry | The study highlights that Porter’s Five Forces framework significantly affects the performance of telecommunication firms in Kenya, while also demonstrating that strategic imitation, when managed effectively, can provide a competitive edge and product differentiation in new market entries. |

| [67] | Industry rivalry |

Superior performance through competitive imitation, Differentiation of new products, Successful mobilization of existing entry resources | This study demonstrates that competitive imitation, when strategically applied during new product development, can provide firms with a superior market edge and product differentiation, especially by leveraging existing resources and learning from competitors. |

| [68] | All Porter’s Five Forces | Competitiveness, Productivity |

This study highlights the importance of implementing Porter’s five forces and generic strategies, such as cost leadership, product differentiation, and focus, to enhance the competitiveness of small and medium industries (SMIs) in Bali, contributing to economic growth and job creation. |

| [69] | All Porter’s Five Forces | Employment generation, poverty reduction, local capacity building |

The study concludes that the use of strategic planning tools, such as financial analysis, SWOT, PEST, and Porter’s five forces, positively influences the performance of SMEs in Kenya, despite challenges like inadequate training and resistance to change. |

| Ref. | QA1 | QA2 | QA3 | QA4 | QA5 | Total | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [23,24,27,29,36,37,42,44,47,48,49,52,54,55,56,59,60,66,67,68,69,70,72] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 100 |

| [22] | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4.5 | 90 |

| [25] | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 | 50 |

| [26,28]; | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4.5 | 90 |

| [30,32,50,57,58,61,62,63,64,71] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 90 |

| [31] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 80 |

| [33] | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 80 |

| [34] | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 60 |

| [38,39,40,43,45,46,53] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 4.5 | 90 |

| [41] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 80 |

| [50] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 90 |

| [51] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 4.5 | 90 |

| [65] | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 80 |

| Best Practice | Description | Strategic Rationale | Technologies/Tools to Support Implementation | Expected Outcomes | Challenges | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Industry Analysis | Conduct detailed market and industry research to identify key players (competitors, suppliers, buyers). | Helps SMEs understand their competitive landscape and identify areas of opportunity or threat. | Market analysis tools, competitor analysis platforms (e.g., SEMrush, SWOT analysis tools). | Clear understanding of competitive dynamics, identification of threats/opportunities. | High cost and time involved in detailed analysis. | Use automated market analysis tools to streamline research and ensure accuracy. |

| Strategic Differentiation | Focus on product differentiation to stand out in highly competitive markets (Industry Rivalry). | Differentiation helps SMEs avoid price wars and compete on quality and innovation rather than cost. | AI-driven product customization, customer feedback platforms for continuous improvement. | Increased customer loyalty, improved market share. | Difficulty in maintaining innovation pace, high R&D costs. | Regularly collect customer feedback and invest in incremental innovations. |

| Building Barriers to Entry | Use cost leadership and innovation to create barriers that deter new entrants (Threat of New Entrants). | Establishes a competitive edge by lowering costs and offering innovative products. | Automation tools, cloud computing, IoT for operational efficiency, blockchain for security. | Reduced risk of new competitors, sustained market position. | Significant upfront investments in technology. | Focus on scalable technologies that provide long-term savings. |