Submitted:

21 September 2024

Posted:

24 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

References

- Wu C, Hou D, Du C, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for coronavirus disease 2019-related acute respiratory distress syndrome: a cohort study with propensity score analysis. Crit Care. Nov 10 2020;24(1):643. [CrossRef]

- McEwen BS, Wingfield JC. The concept of allostasis in biology and biomedicine. Horm Behav. Jan 2003;43(1):2-15.

- Thornton J. Evolution of vertebrate steroid receptors from an ancestral estrogen receptor by ligand exploitation and serial genome expansions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98 (10):5671-5676.

- Cain DW, Cidlowski JA. Immune regulation by glucocorticoids. Nature reviews Immunology. Apr 2017;17(4):233-247. [CrossRef]

- Psarra AM, Sekeris CE. Glucocorticoid receptors and other nuclear transcription factors in mitochondria and possible functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. May 2009;1787(5):431-6. [CrossRef]

- Meduri GU, Psarra A-M, Amrein K. General Adaptation in Critical Illness 2: The Glucocorticoid Signaling System as a Master Rheostat of Homeostatic Corrections in Concerted Action with Mitochondrial and Essential Micronutrient Support.

- In: Fink G, ed. Handbook of Stress: Stress, Immunology and Inflammation San Diego, Elsevier.; 2024:263-287:chap 23. vol. 5.

- Dejager L, Vandevyver S, Petta I, Libert C. Dominance of the strongest: inflammatory cytokines versus glucocorticoids. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. Feb 2014;25(1):21-33. [CrossRef]

- Selye H. The general adaptation syndrome and the diseases of adaptation. J Clin Endocrinol. 1946;6:117-230.

- Hench PS, Kendall EC, Slocumb CH, Polley HF. Arch Internal Med. 1950;85:545-666.

- Meduri GU, Confalonieri M, Chaudhuri D, Rochwerg B, Meibohm B. Prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in ARDS: pathobiological rationale and pharmacological principles. . In: Fink G, ed. Handbook of Stress: Stress, Immunology and Inflammation Academic Press; 2024:289-323:chap 24. vol. Encyclopedia of Stress.

- Munck A, Guyre PM, Holbrook NJ. Physiological functions of glucocorticoids in stress and their relation to pharmacological actions. Endocr Rev. 1984;5(1):25-44.

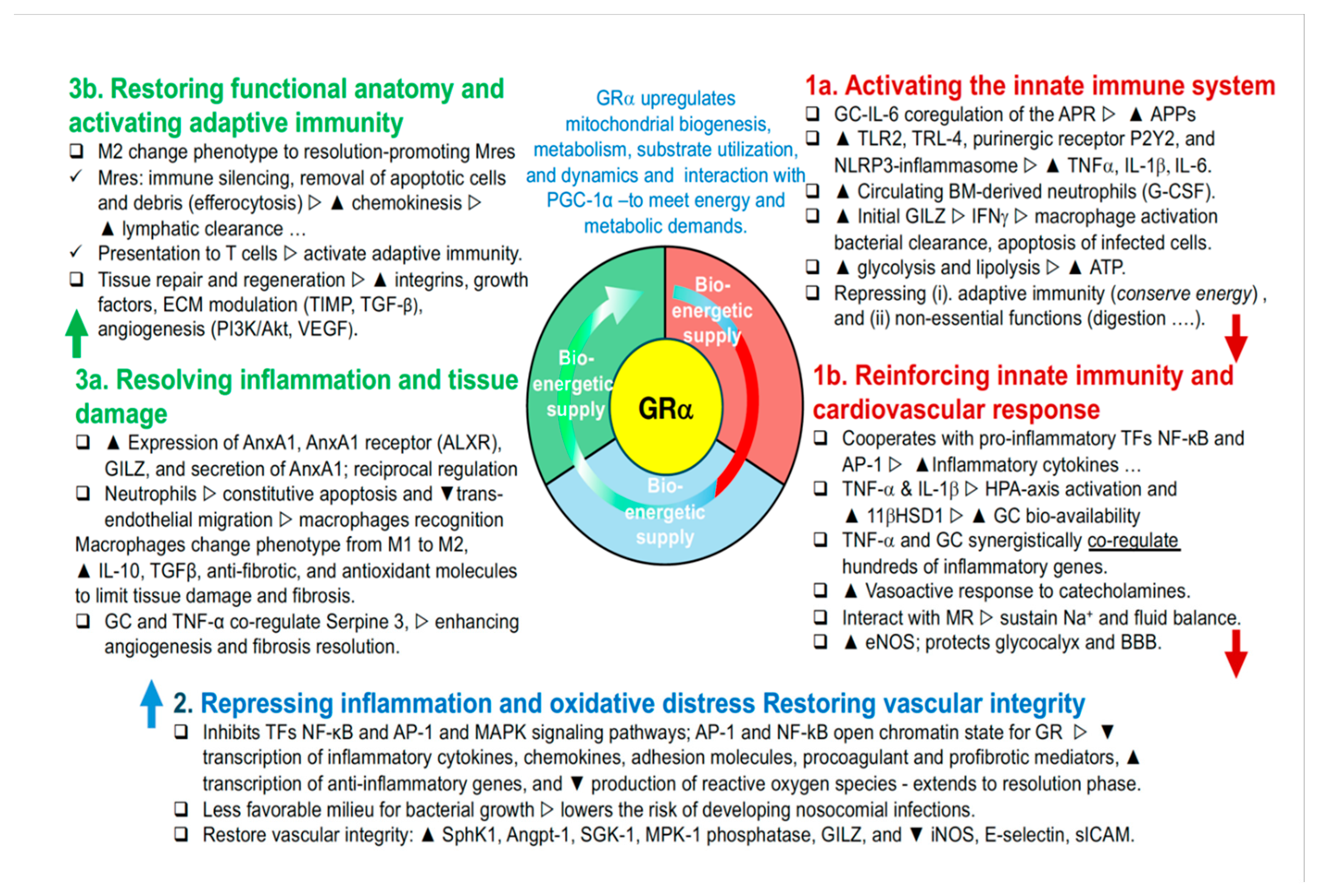

- Busillo JM, Cidlowski JA. The five Rs of glucocorticoid action during inflammation: ready, reinforce, repress, resolve, and restore. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. Mar 2013;24(3):109-19. [CrossRef]

- Meduri GU, Muthiah MP, Carratu P, Eltorky M, Chrousos GP. Nuclear factor-kappaB- and glucocorticoid receptor alpha- mediated mechanisms in the regulation of systemic and pulmonary inflammation during sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Evidence for inflammation-induced target tissue resistance to glucocorticoids. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2005;12(6):321-38. [CrossRef]

- Whirledge SD, Oakley RH, Myers PH, Lydon JP, DeMayo F, Cidlowski JA. Uterine glucocorticoid receptors are critical for fertility in mice through control of embryo implantation and decidualization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112(49):15166-15171.

- Rog-Zielinska EA, Thomson A, Kenyon CJ, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor is required for foetal heart maturation. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(16):3269-3282.

- Bird AD, McDougall AR, Seow B, Hooper SB, Cole TJ. Minireview: glucocorticoid regulation of lung development: lessons learned from conditional GR knockout mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2015;29(2):158-171.

- Oakley RH, Ramamoorthy S, Foley JF, Busada JT, Lu NZ, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoid receptor isoform–specific regulation of development, circadian rhythm, and inflammation in mice. The FASEB Journal. 2018;32(10):5258-5271.

- Meduri GU, Chrousos GA. General Adaptation in Critical Illness: The Glucocorticoid Signaling System as Master Rheostat of Homeostatic Corrections in Concerted Action with Nuclear Factor-kB.

- In: Fink G, ed. Handboo of Stress, Immunology and Inflammation Academic Press; 2024:231-261:chap 22. Handbook of Stress; vol. .

- Meduri GU, Tolley EA, Chrousos GP, Stentz F. Prolonged methylprednisolone treatment suppresses systemic inflammation in patients with unresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome. Evidence for inadequate endogenous glucocorticoid secretion and inflammation-induced immune cell resistance to glucocorticoids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Apr 1 2002;165(7):983-991. [CrossRef]

- Ratman D, Berghe WV, Dejager L, et al. How glucocorticoid receptors modulate the activity of other transcription factors: a scope beyond tethering. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;380(1-2):41-54.

- Rao NA, McCalman MT, Moulos P, et al. Coactivation of GR and NFKB alters the repertoire of their binding sites and target genes. Genome Res. 2011;21(9):1404-1416.

- Biddie SC, John S, Sabo PJ, et al. Transcription factor AP1 potentiates chromatin accessibility and glucocorticoid receptor binding. Mol Cell. 2011;43(1):145-155.

- Lannan EA, Galliher-Beckley AJ, Scoltock AB, Cidlowski JA. Proinflammatory actions of glucocorticoids: glucocorticoids and TNFα coregulate gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology. 2012;153(8):3701-3712.

- Kadiyala V, Sasse SK, Altonsy MO, et al. Cistrome-based cooperation between airway epithelial glucocorticoid receptor and NF-κB orchestrates anti-inflammatory effects. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(24):12673-12687.

- Scheschowitsch K, Leite JA, Assreuy J. New insights in glucocorticoid receptor signaling—more than just a ligand-binding receptor. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:16.

- Carr AC, Maggini S. Vitamin C and immune function. Nutrients. 2017;9(11):1211.

- Hayashi R, Wada H, Ito K, Adcock IM. Effects of glucocorticoids on gene transcription. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;500(1-3):51-62.

- Reichardt HM, Tuckermann JP, Göttlicher M, et al. Repression of inflammatory responses in the absence of DNA binding by the glucocorticoid receptor. The EMBO journal. 2001;

- Barbagallo M, Dominguez L. Magnesium and aging. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(7):832-839.

- Ibs K-H, Rink L. Zinc-altered immune function. The Journal of nutrition. 2003;133(5):1452S-1456S.

- MP R. Selenium and human health. Lancet. 2012;379:1256-1268.

- Lutsenko S. Human copper homeostasis: a network of interconnected pathways. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14(2):211-217.

- Ganz T. Systemic iron homeostasis. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(4):1721-1741.

- Berridge MJ. The inositol trisphosphate/calcium signaling pathway in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(4):1261-1296.

- Meduri GU, Chrousos GP. General Adaptation in Critical Illness: Glucocorticoid Receptor-alpha Master Regulator of Homeostatic Corrections. Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020-April-22 2020;11(161):161. [CrossRef]

- Psarra AM, Sekeris CE. Glucocorticoids induce mitochondrial gene transcription in HepG2 cells: role of the mitochondrial glucocorticoid receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta. Oct 2011;1813(10):1814-21. [CrossRef]

- Karra AG, Sioutopoulou A, Gorgogietas V, Samiotaki M, Panayotou G, Psarra A-MG. Proteomic analysis of the mitochondrial glucocorticoid receptor interacting proteins reveals pyruvate dehydrogenase and mitochondrial 60 kDa heat shock protein as potent binding partners. J Proteomics. 2022;257:104509.

- Picard M, McManus MJ, Gray JD, et al. Mitochondrial functions modulate neuroendocrine, metabolic, inflammatory, and transcriptional responses to acute psychological stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Dec 1 2015;112(48):E6614-23. [CrossRef]

- Gruys E, Toussaint MJ, Niewold TA, Koopmans SJ. Acute phase reaction and acute phase proteins. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. Nov 2005;6(11):1045-56. [CrossRef]

- Busillo JM, Azzam KM, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoids Sensitize the Innate Immune System through Regulation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. J Biol Chem. Nov 4 2011;286(44):38703-38713. [CrossRef]

- Amrani Y, Panettieri RA, Ramos-Ramirez P, Schaafsma D, Kaczmarek K, Tliba O. Important lessons learned from studies on the pharmacology of glucocorticoids in human airway smooth muscle cells: too much of a good thing may be a problem. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;213:107589.

- Ding Y, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA, Suffredini AF. Dexamethasone enhances ATP-induced inflammatory responses in endothelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. Dec 2010;335(3):693-702. [CrossRef]

- Galon J, Franchimont D, Hiroi N, et al. Gene profiling reveals unknown enhancing and suppressive actions of glucocorticoids on immune cells. Faseb J. Jan 2002;16(1):61-71. [CrossRef]

- Meduri GU, Kanangat S, Bronze M, et al. Effects of methylprednisolone on intracellular bacterial growth. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. Nov 2001;8(6):1156-63. [CrossRef]

- Ayroldi E, Riccardi C. Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ): a new important mediator of glucocorticoid action. Faseb J. 2009;23. [CrossRef]

- Ellouze M, Vigouroux L, Tcherakian C, et al. Overexpression of GILZ in macrophages limits systemic inflammation while increasing bacterial clearance in sepsis in mice. European journal of immunology. 2020;50(4):589-602.

- Ballegeer M, Vandewalle J, Eggermont M, et al. Overexpression of Gilz Protects Mice Against Lethal Septic Peritonitis. Shock. Aug 2019;52(2):208-214. [CrossRef]

- Taves MD, Ashwell JD. Glucocorticoids in T cell development, differentiation and function. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2021;21(4):233-243.

- Oakley RH, Cidlowski JA. The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor: new signaling mechanisms in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. Nov 2013;132(5):1033-44. [CrossRef]

- Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How Do Glucocorticoids Influence Stress Responses? Integrating Permissive, Suppressive, Stimulatory, and Preparative Actions. Endocrine Reviews. 2000;21(1):55-89. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Bouazza Y, Sennoun N, Strub C, et al. Comparative effects of recombinant human activated protein C and dexamethasone in experimental septic shock. Comparative Study.

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. Intensive care medicine. Nov 2011;37(11):1857-64. [CrossRef]

- Limbourg FP, Huang Z, Plumier JC, et al. Rapid nontranscriptional activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase mediates increased cerebral blood flow and stroke protection by corticosteroids. J Clin Invest. Dec 2002;110(11):1729-38. [CrossRef]

- Hafezi-Moghadam A, Simoncini T, Yang Z, et al. Acute cardiovascular protective effects of corticosteroids are mediated by non-transcriptional activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nat Med. May 2002;8(5):473-9. [CrossRef]

- Ehrchen J, Steinmuller L, Barczyk K, et al. Glucocorticoids induce differentiation of a specifically activated, anti-inflammatory subtype of human monocytes. Blood. Feb 1 2007;109(3):1265-74.

- Tanaka S, Couret D, Tran-Dinh A, et al. High-density lipoproteins during sepsis: from bench to bedside. Crit Care. Apr 7 2020;24(1):134. [CrossRef]

- Kim EK, Choi EJ. Pathological roles of MAPK signaling pathways in human diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. Apr 2010;1802(4):396-405. [CrossRef]

- Vandevyver S, Dejager L, Libert C. Comprehensive overview of the structure and regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor. Endocr Rev. Aug 2014;35(4):671-93. [CrossRef]

- Mascellino MT, Delogu G, Pelaia MR, Ponzo R, Parrinello R, Giardina A. Reduced bactericidal activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa of blood neutrophils from patients with early adult respiratory distress syndrome. Journal of medical microbiology. Jan 2001;50(1):49-54.

- Kaufmann I, Briegel J, Schliephake F, et al. Stress doses of hydrocortisone in septic shock: beneficial effects on opsonization-dependent neutrophil functions. Intensive Care Med. Feb 2008;34(2):344-9.

- Keh D BT, Weber-Cartens S, Schulz C, Ahlers O, Bercker S, Volk HD, Doecke WD, Falke KJ, Gerlach H. Immunologic and hemodynamic effects of "low-dose" hydrocortisone in septic shock: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(4):512-20.

- Conway Morris A, Kefala K, Wilkinson TS, et al. C5a mediates peripheral blood neutrophil dysfunction in critically ill patients. Multicenter Study.

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Jul 1 2009;180(1):19-28. [CrossRef]

- Headley AS, Tolley E, Meduri GU. Infections and the inflammatory response in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Chest. May 1997;111(5):1306-21.

- Steinberg KP, Hudson LD, Goodman RB, et al. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids for persistent acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. Apr 20 2006;354(16):1671-84. [CrossRef]

- Meduri GU, Golden E , Freire AX, et al. Methylprednisolone infusion in early severe ARDS: results of a randomized controlled trial. Original Research. Chest. April 2007 2007;131(4):954-963. [CrossRef]

- Roquilly A, Mahe PJ, Seguin P, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with multiple trauma: the randomized controlled HYPOLYTE study. Multicenter Study.

- Randomized Controlled Trial.

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. Mar 23 2011;305(12):1201-9. [CrossRef]

- Meduri GU. Clinical review: a paradigm shift: the bidirectional effect of inflammation on bacterial growth. Clinical implications for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. Feb 2002;6(1):24-9.

- Kanangat S, Meduri GU, Tolley EA, et al. Effects of cytokines and endotoxin on the intracellular growth of bacteria. Infect Immun. Jun 1999;67(6):2834-40.

- Kanangat S, Bronze MS, Meduri GU, et al. Enhanced extracellular growth of Staphylococcus aureus in the presence of selected linear peptide fragments of human interleukin (IL)-1beta and IL-1 receptor antagonist. J Infect Dis. Jan 1 2001;183(1):65-69. [CrossRef]

- Sibila O, Luna C, Agustí C, et al. Effects of corticosteroids an animal model of ventilator-associated pneumonia. . abstract. Proceeding of the American Thoracic Society. 2006;3:A 21.

- Vettorazzi S, Bode C, Dejager L, et al. Glucocorticoids limit acute lung inflammation in concert with inflammatory stimuli by induction of SphK1. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7796. [CrossRef]

- Fürst R, Schroeder T, Eilken HM, et al. MAPK phosphatase-1 represents a novel anti-inflammatory target of glucocorticoids in the human endothelium. The FASEB journal. 2007;21(1):74-80.

- Kim H, Lee JM, Park JS, et al. Dexamethasone coordinately regulates angiopoietin-1 and VEGF: a mechanism of glucocorticoid-induced stabilization of blood-brain barrier. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. Jul 18 2008;372(1):243-8. [CrossRef]

- Hahn RT, Hoppstadter J, Hirschfelder K, et al. Downregulation of the glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) promotes vascular inflammation. Atherosclerosis. Jun 2014;234(2):391-400. [CrossRef]

- Chappell D, Jacob M, Hofmann-Kiefer K, et al. Hydrocortisone preserves the vascular barrier by protecting the endothelial glycocalyx. In Vitro.

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. Anesthesiology. Nov 2007;107(5):776-84. [CrossRef]

- Chappell D, Hofmann-Kiefer K, Jacob M, et al. TNF-alpha induced shedding of the endothelial glycocalyx is prevented by hydrocortisone and antithrombin. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. Basic research in cardiology. Jan 2009;104(1):78-89. [CrossRef]

- Aytac HO, Iskit AB, Sayek I. Dexamethasone effects on vascular flow and organ injury in septic mice. J Surg Res. May 15 2014;188(2):496-502. [CrossRef]

- Voiriot G, Oualha M, Pierre A, et al. Chronic critical illness and post-intensive care syndrome: from pathophysiology to clinical challenges. Ann Intensive Care. 2022;12(1):1-14.

- Basil MC, Levy BD. Specialized pro-resolving mediators: endogenous regulators of infection and inflammation. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2016/01/01 2016;16(1):51-67. [CrossRef]

- Vago JP, Tavares LP, Garcia CC, et al. The role and effects of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper in the context of inflammation resolution. J Immunol. May 15 2015;194(10):4940-50. [CrossRef]

- Morioka S, Maueröder C, Ravichandran KS. Living on the edge: efferocytosis at the interface of homeostasis and pathology. Immunity. 2019;50(5):1149-1162.

- Espinasse M-A, Hajage D, Montravers P, et al. Neutrophil expression of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) anti-inflammatory protein is associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome severity. journal article. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6(1):105. [CrossRef]

- Desgeorges T, Caratti G, Mounier R, Tuckermann J, Chazaud B. Glucocorticoids shape macrophage phenotype for tissue repair. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1591.

- Schif-Zuck S, Gross N, Assi S, Rostoker R, Serhan CN, Ariel A. Saturated-efferocytosis generates pro-resolving CD11blow macrophages: Modulation by resolvins and glucocorticoids. European journal of immunology. 2011;41(2):366-379.

- Meduri GU, Schwingshackl A, Hermans G. Prolonged Glucocorticoid Treatment in ARDS: Impact on Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness. Mini Review. Front Pediatr. 2016-August-2 2016;4:69. [CrossRef]

- Wang T-T, Nestel FP, Bourdeau V, et al. Cutting edge: 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. The Journal of Immunology. 2004;173(5):2909-2912.

- Dimitrov V, Barbier C, Ismailova A, et al. Vitamin D-regulated Gene Expression Profiles: Species-specificity and Cell-specific Effects on Metabolism and Immunity. Endocrinology. Feb 1 2021;162(2):bqaa218. [CrossRef]

- Greulich T, Regner W, Branscheidt M, et al. Altered blood levels of vitamin D, cathelicidin and parathyroid hormone in patients with sepsis-a pilot study. Anaesth Intensive Care. Jan 2017;45(1):36-45.

- Ang A, Pullar JM, Currie MJ, Vissers MCM. Vitamin C and immune cell function in inflammation and cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. Oct 19 2018;46(5):1147-1159. [CrossRef]

- Sorice A, Guerriero E, Capone F, Colonna G, Castello G, Costantini SJMrimc. Ascorbic acid: its role in immune system and chronic inflammation diseases. 2014;14(5):444-452.

- Sae-Khow K, Tachaboon S, Wright HL, et al. Defective neutrophil function in patients with sepsis is mostly restored by ex vivo ascorbate incubation. Journal of Inflammation Research. 2020;13:263.

- Kim Y, Kim H, Bae S, et al. Vitamin C is an essential factor on the anti-viral immune responses through the production of interferon-α/β at the initial stage of influenza A virus (H3N2) infection. Immune Netw. 2013;13(2):70-74.

- Combs Jr GF, McClung JP. The vitamins: fundamental aspects in nutrition and health. Edition 5. Chapter 11 Thiamin. Academic press; 2016:298-314.

- Collie JTB, Greaves RF, Jones OAH, Lam Q, Eastwood GM, Bellomo R. Vitamin B1 in critically ill patients: needs and challenges. Clin Chem Lab Med. Oct 26 2017;55(11):1652-1668. [CrossRef]

- Ryan ZC, Craig TA, Folmes CD, et al. 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates mitochondrial oxygen consumption and dynamics in human skeletal muscle cells. 2016;291(3):1514-1528.

- Luo G, Xie ZZ, Liu FY, Zhang GB. Effects of vitamin C on myocardial mitochondrial function and ATP content in hypoxic rats. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao. Jul 1998;19(4):351-5.

- Charoenngam N, Holick MF. Immunologic effects of vitamin D on human health and disease. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):2097.

- Dancer RC, Parekh D, Lax S, et al. Vitamin D deficiency contributes directly to the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Thorax. Jul 2015;70(7):617-24. [CrossRef]

- Tyml K. Vitamin C and microvascular dysfunction in systemic inflammation. Antioxidants. 2017;6(3):49.

- Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Elbers PW, Spoelstra-de Man AM. How to give vitamin C a cautious but fair chance in severe sepsis. Editorial. Chest. 2017;151(6):1199-1200.

- Marik PE. Glucocorticosteroids as Adjunctive Therapy for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Sepsis? Yes, But Not as Monotherapy. Critical care medicine. 2017;45(5):910-911.

- Carr AC, Shaw GM, Natarajan R. Ascorbate-dependent vasopressor synthesis: a rationale for vitamin C administration in severe sepsis and septic shock? Critical Care. 2015;19(1):1-8.

- Mohammed BM, Fisher BJ, Kraskauskas D, et al. Vitamin C: a novel regulator of neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Nutrients. Aug 9 2013;5(8):3131-51. [CrossRef]

- Yadav UC, Kalariya NM, Srivastava SK, Ramana KV. Protective role of benfotiamine, a fat-soluble vitamin B1 analogue, in lipopolysaccharide-induced cytotoxic signals in murine macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med. May 15 2010;48(10):1423-34. [CrossRef]

- Bozic I, Savic D, Laketa D, et al. Benfotiamine attenuates inflammatory response in LPS stimulated BV-2 microglia. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0118372.

- Menezes RR, Godin AM, Rodrigues FF, et al. Thiamine and riboflavin inhibit production of cytokines and increase the anti-inflammatory activity of a corticosteroid in a chronic model of inflammation induced by complete Freund's adjuvant. Pharmacol Rep. Oct 2017;69(5):1036-1043. [CrossRef]

- Bagnoud M, Hoepner R, Pistor M, et al. Vitamin D augments glucocorticosteroid efficacy via inhibition of mTORc1. 2018:33-34.

- Zhang Y, Leung DY, Goleva E. Vitamin D enhances glucocorticoid action in human monocytes: involvement of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and mediator complex subunit 14. J Biol Chem. May 17 2013;288(20):14544-53. [CrossRef]

- Kassel O, Sancono A, Krätzschmar J, Kreft B, Stassen M, Cato AC. Glucocorticoids inhibit MAP kinase via increased expression and decreased degradation of MKP-1. The EMBO journal. Dec 17 2001;20(24):7108-7116. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Leung DY, Richers BN, et al. Vitamin D inhibits monocyte/macrophage proinflammatory cytokine production by targeting MAPK phosphatase-1. J Immunol. Mar 1 2012;188(5):2127-35. [CrossRef]

- Stio M, Martinesi M, Bruni S, et al. The Vitamin D analogue TX 527 blocks NF-kappaB activation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with Crohn's disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. Jan 2007;103(1):51-60. [CrossRef]

- Ojaimi S, Skinner NA, Strauss BJ, Sundararajan V, Woolley I, Visvanathan K. Vitamin D deficiency impacts on expression of toll-like receptor-2 and cytokine profile: a pilot study. J Transl Med. Jul 22 2013;11(1):176. [CrossRef]

- Patak P, Willenberg HS, Bornstein SR. Vitamin C is an important cofactor for both adrenal cortex and adrenal medulla. Endocr Res. 2004;30(4):871-875. [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz A, Andersen LW, Huang DT, et al. Ascorbic acid, corticosteroids, and thiamine in sepsis: a review of the biologic rationale and the present state of clinical evaluation. Crit Care. Oct 29 2018;22(1):283. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto K, Tanaka H, Makino Y, Makino I. Restoration of the glucocorticoid receptor function by the phosphodiester compound of vitamins C and E, EPC-K1 (L-ascorbic acid 2-[3,4-dihydro-2,5,7,8-tetramethyl-2-(4,8,12-trimethyltridecyl)-2H-1-benzopyran-6 -yl hydrogen phosphate] potassium salt), via a redox-dependent mechanism. Biochem Pharmacol. Jul 1 1998;56(1):79-86.

- Chen Y, Luo G, Yuan J, et al. Vitamin C mitigates oxidative stress and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in severe community-acquired pneumonia and LPS-induced macrophages. Mediators Inflamm. 2014:426740. [CrossRef]

- Bowie AG, O’Neill LA. Vitamin C inhibits NF-κB activation by TNF via the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. The Journal of Immunology. 2000;165(12):7180-7188.

- Donnino MW, Andersen LW, Chase M, et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Thiamine as a Metabolic Resuscitator in Septic Shock: A Pilot Study. Critical Care Medicine. Feb 2016;44(2):360-367. [CrossRef]

- Schreiber SN. The transcriptional coactivator PGC-1 [alpha] as a modulator of ERR [alpha] and GR signaling: function in mitochondrial biogenesis. University_of_Basel; 2004.

- Latham CM, Brightwell CR, Keeble AR, et al. Vitamin D Promotes Skeletal Muscle Regeneration and Mitochondrial Health. Front Physiol. 2021;12:463.

- Jain SK, Micinski D. Vitamin D upregulates glutamate cysteine ligase and glutathione reductase, and GSH formation, and decreases ROS and MCP-1 and IL-8 secretion in high-glucose exposed U937 monocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. Jul 19 2013;437(1):7-11. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed BM, Fisher BJ, Kraskauskas D, et al. Vitamin C promotes wound healing through novel pleiotropic mechanisms. Int Wound J. 2016;13(4):572-584.

- Vissers M, Hampton M. The role of oxidants and vitamin C on neutrophil apoptosis and clearance. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32(3):499-501.

| Stage | Description | Key Points | Approximate Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ancient Origins of Steroid Signaling | Evolution of steroid signaling pathways to regulate metabolism and stress responses in early vertebrates. These pathways allowed organisms to manage energy resources and respond to environmental changes. [3] | - Primitive mechanisms for managing energy resources and respond to environmental changes.- Crucial for survival. | ~450-500 million years ago |

| 2. Co-evolution with Immune, Inflammatory, and hemostatic Responses | GR co-evolved with the immune system to regulate inflammation and prevent tissue damage. [4] Hemostasis and inflammatory mechanisms evolved alongside, underscoring their interconnected roles. | - Interaction between GR, NF-kB, AP-1, and hemostasis.- Coordinated response to infection, wounds, and tissue protection. | ~400-450 million years ago |

| 3. Adaptation to Diverse Stressors | GR system evolved to manage a wide range of stressors, including infections, injuries, psychological, and metabolic stress. [50] | - GR as a master regulator.- Integrates signals from various pathways to maintain homeostasis. [50] | ~300-350 million years ago |

| 4. Integration with Mitochondrial Function | GR co-evolved with mitochondrial function, reflecting the role of energy production in stress response. Mitochondria contain glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) [5] | - Mitochondria originated from symbiosis with proteobacteria.- GR-mediated stress response integrated with energy metabolism. MtGRE directly influence mitochondrial gene expression and energy production. | ~1.5–2 billion years ago (mitochondria origin), integration with GR: ~400 million years ago |

| 5. Essential Micronutrients and Antioxidant Systems | GR-mediated corrections rely on micronutrients and antioxidants incorporated into stress responses as organisms evolved more complex diets and metabolic systems. [57] | - Micronutrients provided a survival advantage in environments where oxidative stress and energy demands were high. | ~400 million years ago |

| Organ/System | GRα Regulation |

|---|---|

| Immune System | GRα plays a crucial role in modulating both innate and adaptive immunity by ensuring the immune response is proportionate and controlled. It regulates innate immune cells like macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells, guiding their response to pathogens and injury. In adaptive immunity, GRα regulates T and B cell proliferation, differentiation, and cytokine production, helping maintain immune homeostasis and preventing autoimmunity. GRα upregulates GILZ, which attenuates MAPK/ERK signaling, and Annexin 1, which inhibits neutrophil migration, promotes macrophage-mediated clearance of apoptotic cells, and modulates T and B cell activity. As the immune response progresses, GRα shifts towards repressing pro-inflammatory mediators, promoting the resolution of inflammation and preventing chronic immune activation, thus ensuring a balanced and effective immune response. |

| Lymphatic system | The glucocorticoid receptor (GR) plays a significant role in modulating the function of lymphatic endothelial cells, which are crucial for the integrity and operation of lymphatic vessels. By influencing the permeability and contractility of these vessels, GR affects the flow of lymph, which is essential for the transport of immune cells and antigens throughout the body. Additionally, GR regulates the expression of various transporters and receptors within the lymphatic system, thereby enhancing the efficiency of lymphatic clearance and ensuring effective immune surveillance and response |

| Central Nervous System (CNS) | GRα plays a crucial role in regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, controlling the body's response to stress and helping to restore homeostasis once a threat has passed. In the CNS, GRα modulates neurotransmitter systems, including serotonergic and dopaminergic pathways, influencing mood, cognition, and behavior. It also impacts synaptic transmission by regulating the release and uptake of neurotransmitters, which affects neuronal excitability and synaptic plasticity, further influencing cognitive functions such as memory, attention, and executive function. Additionally, GRα is involved in mood regulation by modulating the activity of brain regions like the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, and it supports brain energy metabolism by regulating glucose availability and utilization. |

|

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) |

GRα regulates the function of the peripheral nervous system by modulating the stress response at the level of peripheral nerves. It influences the sensitivity of peripheral sensory neurons to pain and inflammation, helping to modulate pain perception and inflammatory responses. GRα is also involved in nerve regeneration and repair, influencing the healing process following peripheral nerve injuries by managing inflammation and tissue repair. Additionally, GRα affects the autonomic nervous system, contributing to the regulation of heart rate, blood pressure, and gastrointestinal motility under stress. |

|

Endocrine System |

GRα regulates various endocrine functions by modulating the HPA axis and influencing the production of key hormones such as cortisol, which impacts metabolism, immune response, and stress adaptation. GRα also interacts with other hormones, like insulin, thyroid hormones, and reproductive hormones, ensuring coordinated endocrine responses to stress and maintaining overall hormonal balance. |

| Reproductive System | GRα influences reproductive function by regulating the expression of genes involved in hormone production, ovulation, and pregnancy. It modulates the effects of stress on reproductive health, ensuring that stress responses do not interfere with normal reproductive processes. GRα also plays a role in fetal development by regulating placental function and fetal growth. |

|

Cardiovascular System |

GRα plays a vital role in regulating blood pressure, vascular tone, and overall heart function. It modulates the expression of genes involved in the production of vasodilators, such as endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), essential for maintaining vascular health. GRα also influences glucose uptake, utilization, and storage in the heart, ensuring that cardiac cells have sufficient energy during stress. Additionally, GRα affects cardiac electrophysiology by modulating ion channel function and action potential duration, which is crucial for maintaining normal heart rhythms. |

| Endothelium | GR plays a key role in endothelial homeostasis by regulating the expression of adhesion molecules and cytokines involved in the inflammatory response, thereby reducing inflammation. It also maintains the integrity of the endothelial barrier and glycocalyx, regulates vascular tone and blood pressure through nitric oxide production, protects against oxidative stress, and promotes angiogenesis and vascular repair. These functions are essential for preserving vascular integrity and preventing diseases like atherosclerosis and hypertension. |

| Lungs | GRα plays a vital role in maintaining lung function by modulating the immune response to inhaled pathogens and allergens, reducing airway inflammation, and preventing excessive immune responses that can lead to tissue damage. It supports the repair of lung tissue following injury or infection, ensuring proper respiratory function. Additionally, GRα exerts bronchodilatory effects by relaxing airway smooth muscle and modulates the expression of genes involved in maintaining smooth muscle tone and producing surfactant, a substance crucial for keeping the airways open and facilitating efficient gas exchange. |

| Kidneys | In the kidneys, GRα is involved in the regulation of electrolyte balance and fluid homeostasis. It influences the expression of sodium channels and transporters in the renal tubules, which helps control the reabsorption of sodium and water. This regulation is essential for maintaining blood pressure and overall fluid balance in the body. |

| Liver | GRα plays a crucial role in maintaining liver health and overall immune homeostasis by regulating the expression of key genes involved in metabolism and immune function. In the liver, GRα modulates glucose metabolism by promoting gluconeogenesis and influencing glycogen storage, ensuring that the body has sufficient energy during periods of stress or inflammation. Additionally, GRα is integral to lipid metabolism, detoxification processes, and bile acid metabolism, all essential for processing lipids, eliminating toxins, and supporting digestive functions. GRα enhances protein synthesis, crucial for producing acute phase proteins and enzymes necessary for immune responses and detoxification. Furthermore, GRα works in concert with IL-6 to coactivate the acute phase response (APR), boosting the liver’s production of proteins that manage inflammation and bolster immune defenses during injury or stress. |

| Gastrointestinal Tract | GRα regulates gastrointestinal function by modulating the immune response within the gut. It helps maintain the integrity of the gut lining by controlling inflammation and promoting the repair of damaged tissues. Additionally, GRα plays a role in regulating the gut microbiome by modulating the local immune environment and inflammatory responses, and influences gut motility and secretion, contributing to the proper digestion and absorption of nutrients. |

| Pancreas | GRα helps regulate insulin production and glucose homeostasis in the pancreas. It modulates the function of pancreatic beta cells, which are responsible for insulin secretion. By balancing the production and release of insulin, GRα helps maintain normal blood glucose levels, particularly during stress or fasting. The GR is expressed in various cell types within the pancreatic islets, including beta cells, alpha cells, and delta cells. Activation of the GR in these cells can affect their function and hormone secretion |

| Adipose Tissue | GRα is involved in lipid metabolism within adipose tissue. It promotes lipolysis, the breakdown of stored triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol, which can then be used as energy sources. GRα also regulates the balance between lipid storage and mobilization, ensuring energy availability during periods of stress or fasting. |

| Muscle | GRα is important for preserving muscle function, especially during stress. It regulates protein breakdown to provide energy through gluconeogenesis while also modulating inflammation to support muscle repair after injury. GRα helps maintain a balance between muscle breakdown and building, ensuring muscle strength and resilience during stress or recovery. |

| Bone | GRα plays a role in maintaining bone health by regulating the balance between bone formation and resorption. It influences the activity of osteoblasts (bone-forming cells) and osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells), ensuring proper bone remodeling and mineral homeostasis, which is crucial for maintaining bone density and structural integrity. |

| Skin | GRα helps maintain skin homeostasis by regulating the skin's inflammatory response. It controls the production of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators, ensuring that the skin's immune responses are appropriate and do not result in excessive inflammation. This is important for protecting the skin from infections and environmental stressors. |

| Cell Type | Brief Description of GRa Role |

|---|---|

| 1. Immune Cells | |

| - T cells | GRa modulates T cell function by inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-2, IFN-γ), promoting the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs), and reducing the proliferation of effector T cells. This results in the suppression of excessive immune responses and maintenance of immune tolerance. |

| - B cells | GRa plays a role in suppressing B cell activation and differentiation into plasma cells, thereby reducing antibody production. It also impacts B cell survival and modulates the production of regulatory cytokines like IL-10, which further influences immune responses. |

|

- Monocytes/ Macrophages |

GRa regulates the transition of monocytes into macrophages and affects their polarization into either pro-inflammatory (M1) or anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotypes. It suppresses the production of inflammatory mediators (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) and enhances phagocytic activity and tissue repair functions. |

| - Dendritic Cells | GRa modulates the maturation and function of dendritic cells (DCs), reducing their ability to present antigens and activate T cells. This leads to a decrease in adaptive immune responses and helps to maintain immune homeostasis, especially during chronic inflammation. |

| - Natural Killer (NK) Cells | GRa influences the cytotoxic activity of NK cells, reducing their ability to target and destroy virus-infected or tumor cells. It also modulates the production of cytokines like IFN-γ, which plays a role in shaping the overall immune response. |

| Eosinophils | GRa suppresses eosinophil activation, reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines involved in allergic responses and asthma. It also decreases eosinophil survival and migration, helping to control inflammation and tissue damage in allergic conditions |

| 2. Non-Immune Cells | |

| - Erythrocytes (Red Blood Cells) | GRa regulates erythropoiesis by influencing the production of erythropoietin and other factors involved in red blood cell maturation. It also impacts hemoglobin synthesis and the capacity of erythrocytes to transport oxygen, particularly under stress conditions. |

| - Platelets | GRa affects platelet function by modulating the expression of surface receptors involved in platelet activation and aggregation. This regulation is crucial in balancing hemostasis and preventing excessive clot formation during inflammation. |

| - Endothelial Progenitor Cells | GRa plays a role in the mobilization and differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), which are essential for vascular repair and regeneration. It also modulates the expression of factors that influence endothelial function and vascular integrity, particularly in response to injury or stress. |

| Temporal Phase |

Factors Affecting GRα Function |

Binding Partners |

Vitamins and Micronutrients Supporting GRα Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Activation Phase | Ligand availability (e.g., cortisol levels), adrenal gland function | Corticosteroid-binding globulin (CBG), Cortisol biosynthetic enzymes | Vitamins: B6, C; Minerals: Sodium |

| Chromatin Remodeling and Gene Accessibility | Chromatin accessibility, histone modifications | Chromatin remodeling complexes, Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) | Vitamins: B9, C; Minerals: Zinc |

| Immediate Post-translational Modifications | Phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitination | Kinases (e.g., MAPK), Phosphatases | Vitamins: B6, C, E; Minerals: Magnesium, Zinc |

| Early Signaling and Interaction Phase | Receptor interactions (MR, ER), cytokine signaling (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) | Estrogen receptors (ER), Mineralocorticoid receptors (MR), NF-κB, AP-1 | Vitamins: C, E; Minerals: Selenium, Zinc; Regulatory processes: Immune signaling |

| Sustained Signaling Phase | Oxidative stress, mitochondrial function | Antioxidant enzymes (e.g., glutathione peroxidase), Mitochondrial transcription factors (e.g., TFAM) | Vitamins: C, E; Minerals: Selenium, Zinc, Magnesium, Iron |

| Long-term Regulation and Maintenance | Epigenetic modifications, gut-brain axis signaling, prolonged cortisol exposure | DNA methyltransferases, Toll-like receptors (TLRs), Hepatic enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4, 11β-HSD1, 11β-HSD2) | Vitamins: B9, B12, D, E; Minerals: Zinc, Magnesium, Iron |

| Homeostatic Phase |

Thiamin | Vitamin D | Vitamin C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reinforce innate immunity | - |

Supports innate and adaptive immune system. ⇑ TLR coreceptor CD14. ⇑ antimicrobial peptides cathelicidin and LL-37. [85] ⇑ neutrophil recruitment, activation, and function. [86] ⇑ antibacterial activity. [87] |

Supports neutrophil anti-bacterial function at hypoxic inflammatory sites. [88] ⇑ neutrophil and macrophage chemotaxis, phagocytic capacity, lysozyme activity for cell elimination, and bacterial killing. [88,89,90] Supports lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation. [88] ⇑ production of type I interferons (IFNs) for anti-viral immune responses against influenza virus infection. [91] |

| Bioenergetic supply | Essential for energy metabolism and carbohydrate breakdown/ATP production [92] Thiamin pyrophosphate is a cofactor for PDH, a-KGDC. [93] |

⇑ mitochondrial number, morphology, physiology, and expression of key mitochondrial proteins, resulting in increased ATP synthesis. [94] | ⇑ ATP synthesis. [95] |

| Vascular integrity | - | Modulate endothelial function (non-genomic up-regulation of eNOS gene expression) and vascular permeability (prevents the formation of intracellular endothelial gaps) via multiple genomic and extra-genomic pathways. [96] Protective effect on the alveolar capillary membrane. [97] |

Improves endothelial permeability, microvascular and macrovascular function. [98] Preserves endothelial barrier integrity [99] in synergy with GC. [100] Cofactor for dopamine and vasopressin. [101] Down regulator of NET formation in sepsis. [90,102] |

| Repress inflammation | Exerts significant anti-inflammatory effects: (i) ⇓ activation of p38-MAPK, (ii) ⇓ degradation of Ik-Ba, and (iii) ⇑ activation and nuclear translocation of NF-kB, ⇓ expression of cytokines and chemokines, iNOS and COX-2. [103] ⇓ nuclear NF-kB/p65 protein level, ⇑ IL-10 synthesis – ⇓ synthesis of iNOS, COX-2, Hsp70, TNF-a, and IL-6. [104] Sinergy with glucocorticoids in inhibiting IL-6 transcription. [105] |

⇑ GR concentration [106] and GC function. [107] ⇓ synthesis of TNF-a and IL-1b. [87] ⇑ GC-mediated MKP-1 ⇒ ⇓ p38 MAPK-mediated inflammatory genes. [107,108,109] ⇑ IkBa expression ⇒ ⇓ NF-kB. [110,111] GR represses Vitamin D inactivator CYP24A1. |

Cofactor for GC synthesis. [112] Improves GR function. [113] Reverses oxidation of the GR. [114] GC facilitate Vit C cellular uptake ⇓ synthesis of TNF-α and IL-6. [115] ⇓ Ik-Ba degradation ⇒ ⇓ NF-kB activation and nuclear translocation. [116] |

| Repress oxidative stress | ⇑ Transketolase a key enzyme for the pentose phosphate pathway and for the synthesis of NADPH with glutathione cycling, an important antioxidant pathway. [117] |

VDR is a GR target for PGC-1a induction a. [118] Protective against ROS production [119] ⇑ Glutathione and glutamate formation ⇒ ⇓ ROS formation. [120] |

General role: electron donation as one of the most potent antioxidants Suppress NADPH oxidase (NOX) pathway. [113] Prevents the depletion of other circulatory antioxidants, such as lipid-soluble vitamin E and glutathione. [99] |

| Resolve and restore anatomical function | - | Restore alveolar epithelial barrier, promoting the proliferation of type 2 epithelial cells, and inhibiting fibroproliferation | ⇑ expression of pro-resolution and wound healing biomarkers, better matrix organization, and collagen deposition consistent with adaptive repair. [121] ⇑ neutrophils apoptosis and clearance from inflammatory sites. [122] ⇑ Collagen synthesis, recycles other antioxidants, improves wound healing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).