II. Results

Theorems 1 and 2 were already stated in our previous study [

9] for

. We restate them here

for clarity.

Theorem 1. A quadruplet is the shortest string that allows for more than one ASI .

Proof.

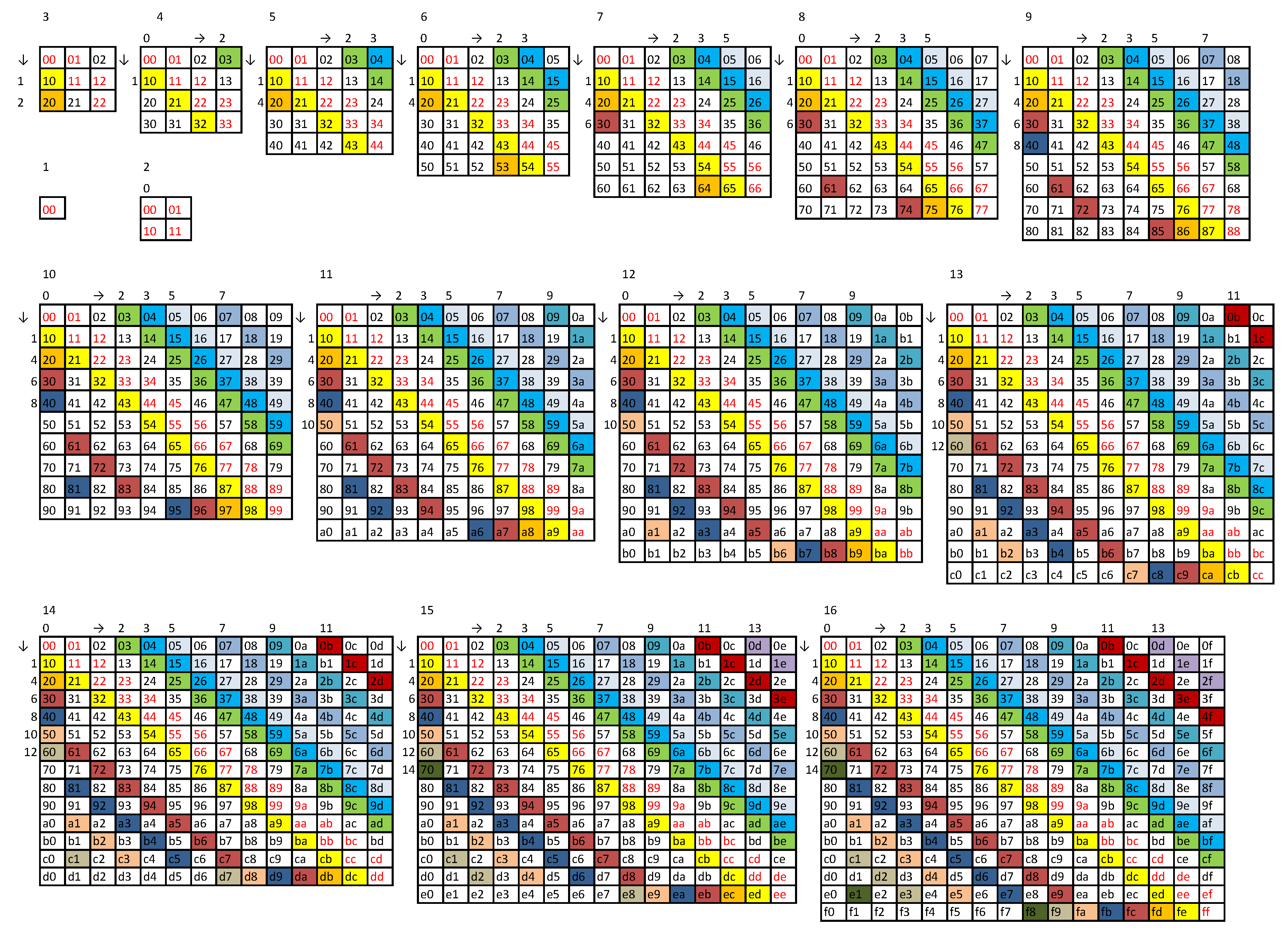

provides available doublets with unit ASI. provides available triplets with ASI equal to two. Only provides quadruplets that include quadruplets with ASI equal to two, that is b quadruplets and quadruplets , while the ASI of the remaining quadruplets is three. □

For example, to assemble the quadruplet , we need to assemble the doublet and reuse it from the first step working ASP , while there is nothing available to reuse, in the case of the quadruplet .

Where the symbol value can be arbitrary, we write * assuming that it is the same within the string. If we allow for the possibility different from *, we write ★. Thus, , for example, is a placeholder for all b strings, while a placeholder for all strings. Furthermore, we consider the degenerate case of just one basic symbol ().

Theorem 2. The minimum ASI as a function of N corresponds to the shortest addition chain for N (OEIS A003313) .

Proof. Strings

for which

,

can be formed in subsequent steps

s by joining the longest string assembled so far with itself until

is reached. Therefore, if

, then

. Only

strings have such ASI if

, including respectively

b and

strings

and the assembly pathway of each of the strings (

2) is unique. At each assembly step, its length doubles.

An addition chain for

having the shortest length

(commonly denoted as

) is defined as a sequence

of integers such that

,

for

. Hence,

and the first step in creating an addition chain for

N is always

, which is an equivalent of saying that the ASI of any doublet is one. The second step in creating an addition chain can be

,

, or

. The

case does not represent the shortest addition chain but the first step, the

one corresponds to assembling a triplet based on the previously assembled doublet, and the

one corresponds to assembling a minimum ASI quadruplet (

2) from this doublet. Maximum ASI quadruplet can be assembled in a third step

, which corresponds to joining a basic symbol to a triplet. Therefore, four is the smallest number achievable in two ways according to Theorem 1.

Thus, finding the shortest addition chain for N corresponds to finding the ASI of a string containing basic symbols and/or doublets and/or triplets containing these doublets for since due to Theorem 1 only they provide the same assembly indices with no internal repetitions. □

The assembly pathways of strings of length are not unique. For example, a string can be assembled in three steps from four working ASPs , , and .

We note in passing that any shortest addition chain for n starts with one, not zero, as zero is the neutral element of addition. For the same reason, two is considered the smallest prime, as one is the neutral element of multiplication. Hence, the fundamental theorem of arithmetic can be thought of as the shortest multiplication chain for n.

Theorem 3. The strings can contain at most two distinct symbols if . Other minimum ASI strings of length can contain at most three distinct symbols if .

Proof. Minimum ASI strings of length are formed by joining the newly assembled string to itself, where a clear or mixed doublet is created in the first step. Minimum ASI strings of other lengths admit a doublet and a triplet containing this doublet and an additional basic symbol.

To formally prove the first part, we can also use mathematical induction on the assembly step

s. If

, then the minimum ASI strings

are doublets of the form

, where

. If

, the string contains one distinct symbol, and if

, the string contains two distinct symbols. In both cases, the string has a form (

2) and the number of distinct symbols does not exceed two. Now assume that for some

, all minimum ASI strings

contain at most two distinct symbols. We must show that

also contains at most two distinct symbols. We construct

by joining two identical minimum ASI strings

with each other. By the inductive hypothesis, each

contains at most two distinct symbols. Therefore, their concatenation also contains at most two distinct symbols. By induction, for all

, the minimum ASI string

contains at most two distinct symbols.

We will now show that other minimum ASI strings of length can contain at most three distinct symbols if . We provide the construction of minimum ASI strings with three symbols. In the first step , we create a doublet where and . Next, we join the existing doublet with a new symbol where . This forms a triplet , introducing a third distinct symbol and further increasing the ASI by 1. We continue assembling by joining the longest string formed so far with itself or with previously formed strings, maintaining the minimal ASI increase.

Assume a contrario that there exists a minimum ASI string of length that contains four or more distinct symbols. But, to incorporate a fourth symbol, at least one additional assembly step is required beyond what is needed for the three symbols. This additional step implies an increase in ASI, which contradicts the minimality of . Thus, Theorem 3 is proven. □

The strings having non-minimum ASI can contain all symbols. For example, the string [

14]

has ASI

and contains all five basic symbols

.

Theorem 4. A string containing the same three doublets has the same ASI as a string containing two pairs of the same doublets, provided that both strings have the same distributions of other repetitions and have the same lengths.

Proof. Without loss of generality (w.l.o.g.), consider the following two strings of the same length

with

and the same distributions of other repetitions (if there are any other repetitions)

where

. Creating a doublet takes one assembly step. Each appending of a doublet to an assembled string counts as another assembly step. Hence, in a general case (i.e., for strings

,

containing also other symbols), the string

requires six additional assembly steps, the same as the string

, which completes the proof. □

Theorem 5. A string containing the same three doublets has the same ASI as a string containing the same two triplets, provided that both strings have the same distributions of other repetitions.

Proof. W.l.o.g. consider the following two strings of the same length

with the same distributions of other repetitions

Creating a triplet takes two assembly steps. Hence, in the general case, the string

requires four additional assembly steps, the same as the string

, which completes the proof. □

Theorem 6. A string containing the same two triplets has the same ASI as a string containing two pairs of the same doublets, provided that both strings have the same distributions of other repetitions and have the same lengths.

Proof. The proof stems from Theorems 4 and 5. □

Theorem 7. A string containing the same two quadruplets of the minimum ASI has the same ASI as a string containing the same three triplets, provided that both strings have the same distributions of other repetitions and have the same lengths.

Proof. W.l.o.g. consider the following two strings of the same length

with the same distributions of other repetitions

Creating such a quadruplet takes two assembly steps. Hence, in a general case, the string

requires five additional assembly steps, the same as the string

, which completes the proof. □

Theorem 8. A string containing the same two quadruplets of the maximum ASI has the same ASI as a string containing a doublet and the same two triplets based on this doublet, provided that both strings have the same distributions of other repetitions.

Proof. W.l.o.g. consider the following two strings of the same length

with the same distributions of other repetitions

Creating such a quadruplet takes three assembly steps. Hence, in a general case, the string requires five additional assembly steps, the same as the string , which completes the proof. □

Theorem 9. A string containing the same two doublets and the same two triplets not based on this doublet has the same ASI as a string containing a doublet and the same two triplets based on this doublet, provided that both strings have the same distributions of other repetitions and have the same lengths.

Proof. W.l.o.g. consider the following two strings of the same length

with the same distributions of other repetitions

where

. In a general case, the string

requires seven additional assembly steps, the same as the string

, which completes the proof. □

In general, Theorems 1-9 show that

k copies of a doublet in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

k copies of a triplet in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

k copies of a minimum ASI quadruplet in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

k copies of a maximum ASI quadruplet in a string decrease the ASI of this string at least by ;

where, the phrase "at least" is meant to indicate that other repetitions, such as e.g. doublets forming multiple quadruplets, etc. can further decrease the ASI of the string. This observation allows us to state the following theorem.

Theorem 10.

Each copies of an -plet contained in a string decrease its ASI at least by . That is

where R is the total number of repeated -plets.

Proof. W.l.o.g. consider the following string

containing two copies of an

n-plet

. The

n-plet

can be assembled in at least

steps and appended to the assembled string

in one step. Consider that the ASI of the

n-plet

is

, i.e. the

n-plet does not have any repetitions that can be reused. Then one copy of this

n-plet - as expected - does not decrease the ASI of the string

, as

, while more copies

k decrease it by

. On the other hand, if

then even a single copy of this

n-plet will decrease the ASI of

. □

For example, due to the presence of three copies of a 5-plet

, each with

, in a string

its ASI amounts to

. The relation (

10) provides the upper bound on ASI as it does not describe a situation in which

n-plet for

is assembled based on a doublet also present in one copy in the string. For example, the string

, while

. We note that the maximum ASI decrease is provided by

-plets of the minimum ASI and amounts to

.

Another quantity quantifying the complexity of a string is the assembly depth (ASD) defined [

15] as

where

, and

and

are the ASDs of two substrings

,

of the string

that were joined in step

s. For

, and if there are more assembly pathways with different depths

leading to a string, which happens if at least two independent assembly steps are possible, the minimum pathway depth is the ASD of this string. Hence, the ASD captures the notion of an

independent assembly step.

Theorem 11. If a working ASP contains strings having the same ASD they were assembled in independent assembly steps.

Proof. W.l.o.g. assume

a contrario that the working ASP contains two strings

,

having the same ASD, i.e.,

, that were not assembled in independent assembly steps, i.e., that

was used in the assembly of

along with a basic symbol

c in some previous step

s. Then

which contradicts our assumption and completes the proof. □

In other words, if two strings

,

in the working ASP have the same ASD, their assembly pathways are unrelated to each other; by the defining equation (

13) neither of them could have been used in the assembly pathway of the other. Here, we introduce the following definition, which is also related to the independent assembly step.

Definition 3. We call the number of steps to reach 1 starting from and assigning if is odd and otherwise (OEIS A014701 sequence) the depth index (DPI).

Theorem 12.

The maximum length N of any string that can be assembled with the ASD (13), , satisfies

Proof. Assume a contrario that . Then for , we have which is a contradiction as basic symbols c have unit length . □

Theorem 13.

The minimum ASI-independent ASD as a function of N, , satisfies

where denotes the ceiling function.

Proof.

follows from the relation (

15).

satisfies both the definition (

13) and our hypothesis (

16). Similarly

. Using induction on length

N, assume that for some

, we can assemble a minimum ASD string with ASD (

16). We need to show that for

, we can assemble a string with the ASD satisfying

Since, by definition (

13), the ASD as a function of

N is monotonously nondecreasing and can increase at most by one between

N and

, we have

where we used relations (

16) and (

17). Solving the relation (

18) for

N yields

and completes the proof. □

The ASD does not have to be a monotonously nondecreasing function of the assembly step. For example

Theorem 14. The ASI and the ASD of a minimum ASI string are equal to each other.

Proof. We use mathematical induction on the length

N of the string. For the base case (

), the string consists of a single basic symbol

. Hence, its ASI is

and its ASD

. Therefore,

. Assume now that for all strings of length

less than

N, the ASD equals the minimum ASI, that is

For some integer

s, we construct the minimum ASI string as follows. First, we assemble a doublet from two basic symbols:

Its ASI is

and its ASD is

. Then for each

we have

with the ASI

and the ASD

and we construct

by joining two copies of

The ASI of the string

is equal to

and, similarly, its ASD is equal to

Therefore,

in this case. At any step, we assemble strings (

2). The proof also follows from Theorems 2 and 13. □

Theorem 15. The assembly pathways of strings having the same ASI and ASD cannot contain independent assembly steps.

Proof. For the minimum ASI strings of length

, the proof follows from the proof of Theorem 14, as no two assembly steps can be independent. Furthermore, the set of such strings contains the strings

of our previous study [

9], which are constructed by adding

-plet to a

-plet assembled in a previous assembly step. The base case for

describes the assembly of a triplet by joining a symbol to a doublet made in a previous assembly step, so that both the ASI and the ASD of this triplet increase by one. The case for

describes the assembly of a 5-plet or 6-plet, again with unit increase of the ASI and the ASD, and so on. □

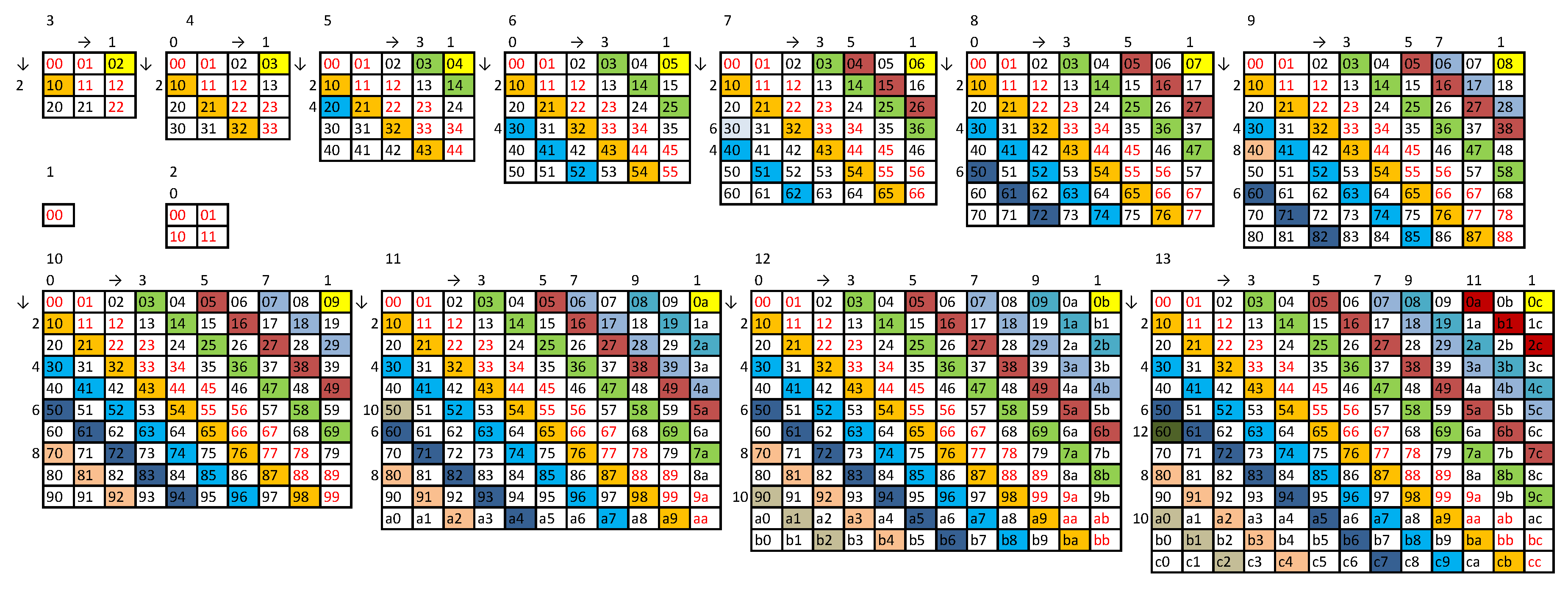

The assembly pathways of other minimum ASI strings can contain independent assembly steps. The first such case occurs for

, where the pathway

results in a string having ma

and

, since both

and

were assembled from the doublet

in two independent assembly steps at the same depth

, which is congruent with Theorem 11.

Theorem 13 considers ASI-independent ASD, neglecting the working ASP, and hence also the AT principles. Similarly, the maximum achievable ASD would be

, as a result of increasing the length of the string by one unit length symbol in

steps. Hence, in general, we cannot consider the ASD apart from the ASI. For example, the ASD of a string

is

as

even though this string can be assembled with three larger pathway depths

. Similarly, the ASD of a string

is

as

However, the non-maximum ASI string

has only two doublets that can be assembled in independent steps. Hence, its ASI-dependent ASD cannot be decreased to

In general, the working ASP that contains a

-plet at the ASD

d can also contain

-plets based on the substrings contained in the working ASP at the ASD

.

Conjecture 16.

Strings [9] of lengths

are minimum ASI strings with assembly pathways devoid of independent assembly steps and the ASI higher than the minimum ASI-independent ASD (

16).

Conjecture 17.

If the DPI equals the minimum ASI of a string , then the ASD of this string equals the minimum ASI-independent ASD (

16)

as a function of N, , that is

Conjecture 18.

If the DPI is larger than the minimum ASI of a string , then the ASD of this string equals its minimum ASI, that is

and the ASD can be achieved in assembly steps.

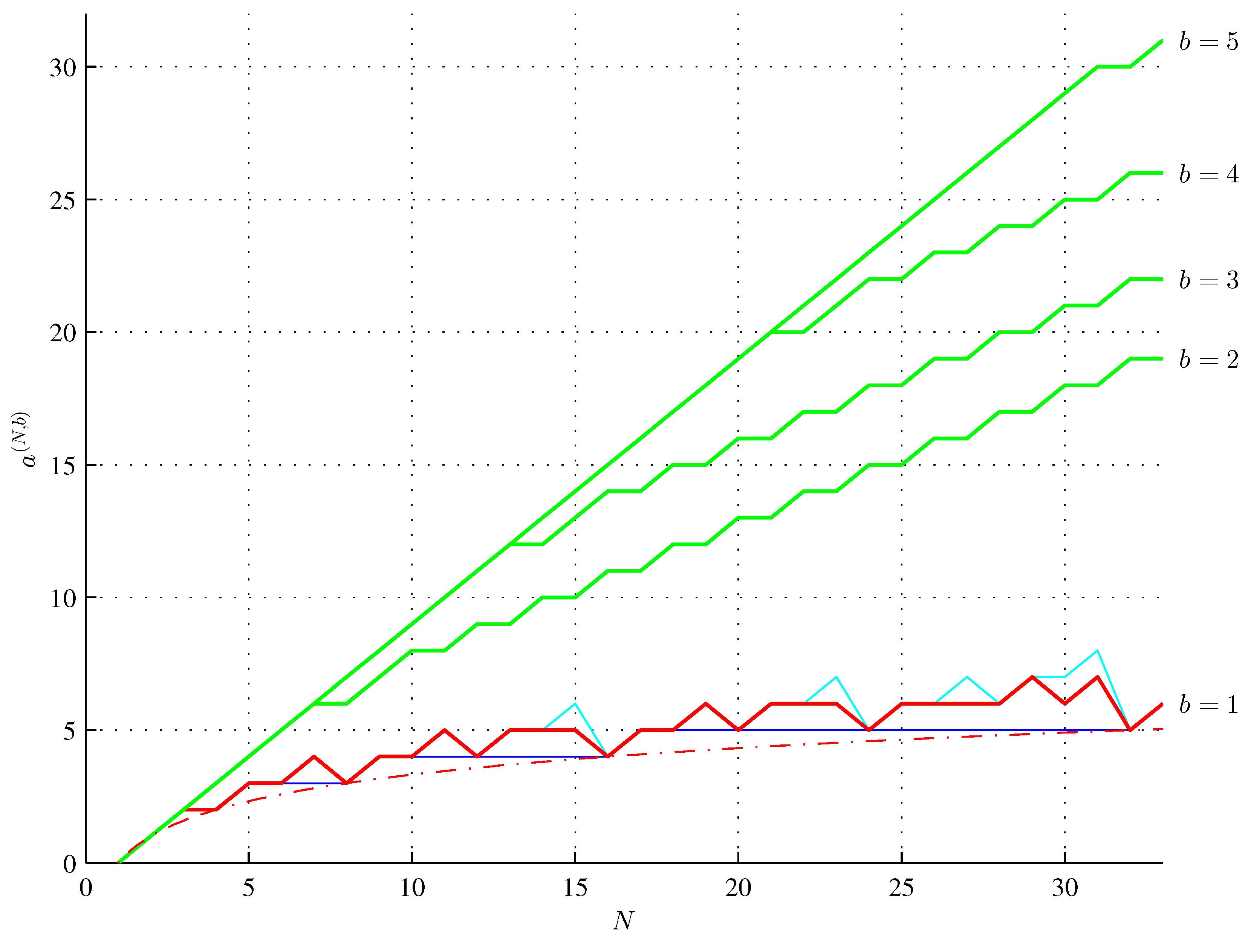

For example, the DPI

is larger than the ASI

. Therefore, the ASD of any string

having this ASI is

, whereas the minimum ASI-independent ASD

can be achieved with a string assembled in six assembly steps, which corresponds to the DPI of

. Certain tuples satisfying the Conjecture 18 are listed in

Table 1 and illustrated in

Figure 1.

In general, Theorems 11-15 show that

the working ASP of minimum ASI strings having ASI equal to DPI cannot contain strings assembled in independent assembly steps,

the working ASPs of other minimum ASI strings can contain at least two such strings, and therefore

the assembly pathway of a maximum ASI string will tend to maximize the number of strings assembled in independent assembly steps in the working ASP, taking into account the saturation of the working ASP as it cannot contain more than distinct n-plets, and hence to minimize the possible ASD.

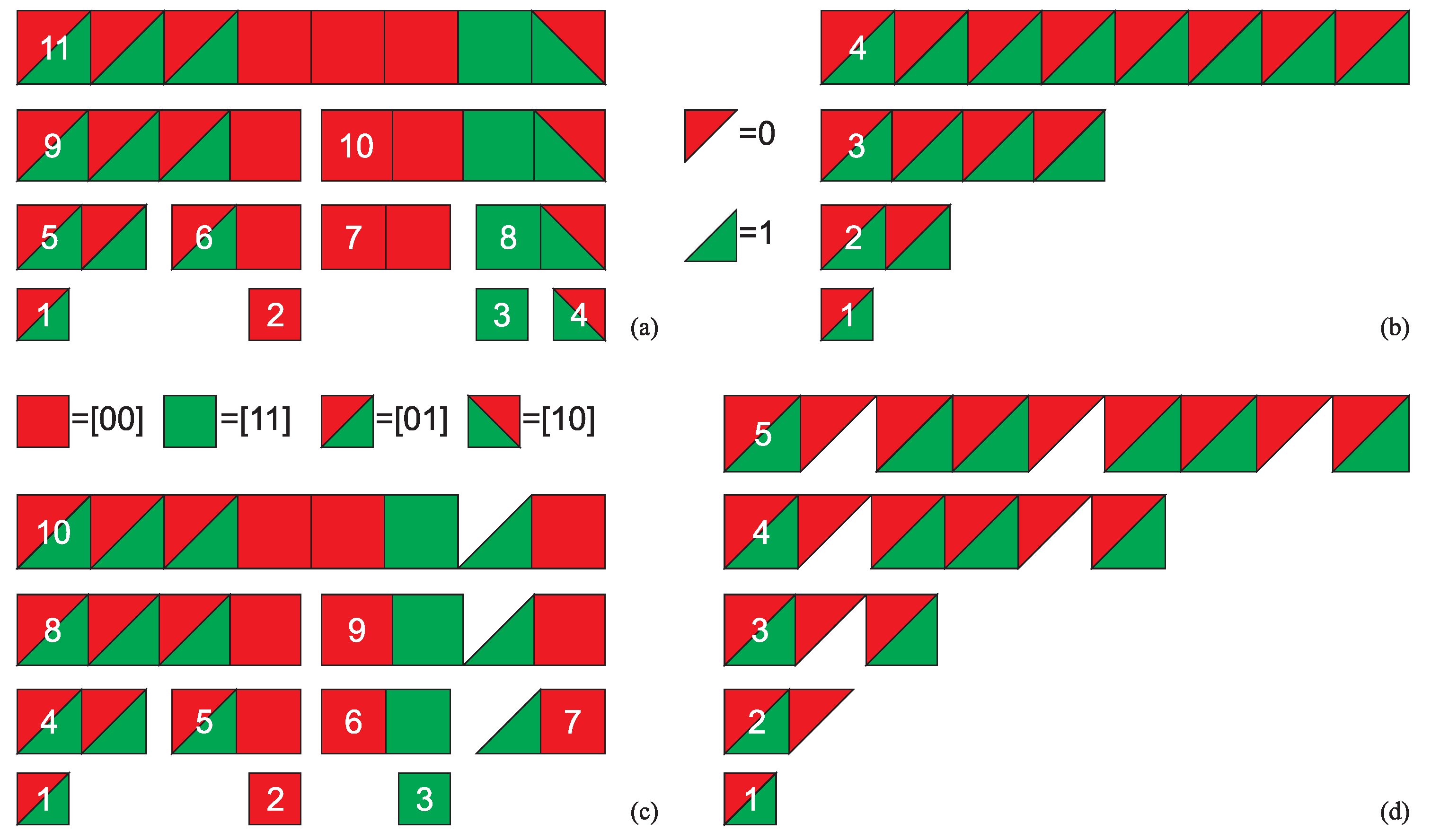

As shown in

Figure 2(c,d), the string

has the ASI

and the ASD

, while the string

has smaller ASI

but larger ASD

. On the other hand, the ASD of the strings

(

A21) and (

2), shown in

Figure 2(a,b), is the same.

Theorem 19.

The ASD of any maximum ASI string , for all b corresponds to the minimum ASI-independent ASD (

16)

of Theorem 13, that is

Proof. Using the property of the ceiling function

valid for

, we have

The non-strict inequality (

35) corresponds to the non-strict inequality (

15) valid for any

N and any ASD. Therefore, we need to prove that the strict inequality

holds for all

strings. Assume, for contradiction, that there exists a maximum ASI string

such that

But this relation does not hold for the maximum ASI string

. □

The seven-bit string is the longest string that can have the maximum ASI

. There are four such bitstrings containing two clear triplets and the starting bit at the end or the ending bit at the start, that is

and their lengths cannot be increased without a repetition of a doublet, which keeps the ASI at the same level

.

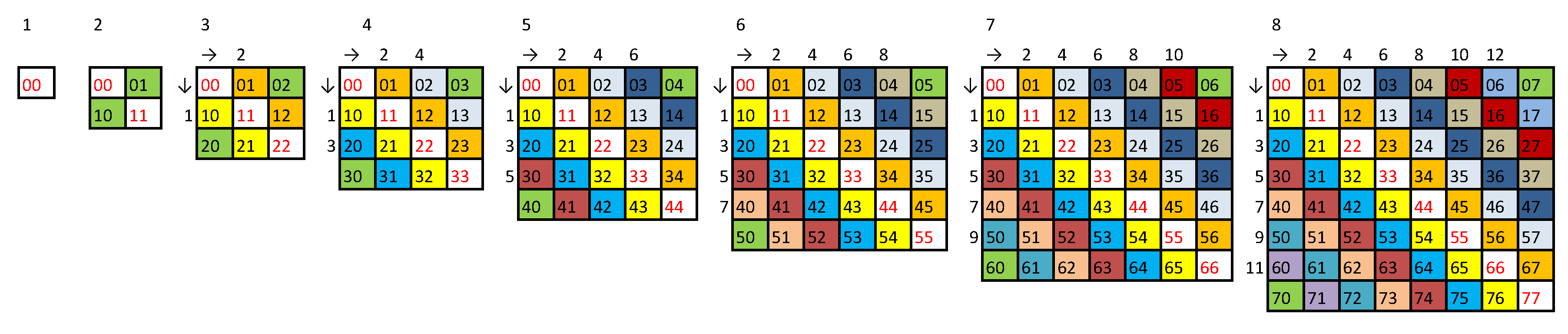

This observation and Theorem 2 motivated us to develop a general method to construct the longest possible string having the maximum ASI , as a function of the radix b. We denote the length of this string by or , and we call this string a string.

After a few groping try-outs, we eventually reached two stable methods (cf. Appendices, Methods A and B). In both methods, we start with an initial balanced string of length

containing

b clear triplets ordered as

The doublets that can be inserted into the initial string (

38) can be arranged in a

matrix

where the crossed out entries on a diagonal cannot be reused, as they would create repetitions in this string. If we assume that we shall not insert doublets between the clear triplets of the string (

38), we can also cross out the entries in the first superdiagonal of the matrix (

39). The strings of odd lengths generated by these general methods are not only the longest but also the most balanced. This can be stated in the following theorem.

Theorem 20.

The longest length of a string that has the ASI of is given by

(OEIS A353887) and this string is nearly balanced, that is

where is the number of occurrences of all but one symbol within the string, and its Shannon entropy is

The proof of Theorem 20 is given in

Appendix D. A

string must contain all clear triplets and all doublets and if it is generated by Method A or B it is terminated with 0 and has a form

Although the case for

is degenerate, as no information can be conveyed using only one symbol (

in this case), nothing precludes the assembly of such defunct strings and the formula (

40) yields the correct result; the string

is the longest string with

by Theorem 1, as for

the upper and the lower bound on the ASI are the same,

(OEIS

A003313). This is the only case where the maximum ASI is not a monotonically nondecreasing function of

N.

For

, only two doublets can be introduced without repetitions into the initial string (

38), leading to twelve unique strings of length

Finally, we have to multiply the cardinality of this set by

to account for permutations. For example, the first string

, is equivalent to five strings

,

,

,

, and

. Hence, there are seventy-two different strings of length

.

Subsequently, we considered other strings of length with the maximum ASI for .

Theorem 21.

For all and the longest length of a string that has the ASI of is given by

The proof of Theorem 21 is given in

Appendix E. This result disproves our upper bound Conjecture 1 for

stated in our previous study [

9]. If the strings of Theorem 21 are based on strings generated by Method A or B, for

they owe their properties to the following distributions of symbols

For the strings of the form (

46) the fractions in the Shannon entropy are

where

,

if

and

,

otherwise, as

is inserted into

,

into

and

or

otherwise. This leads to Shannon entropy

of any

string having length

, for

.

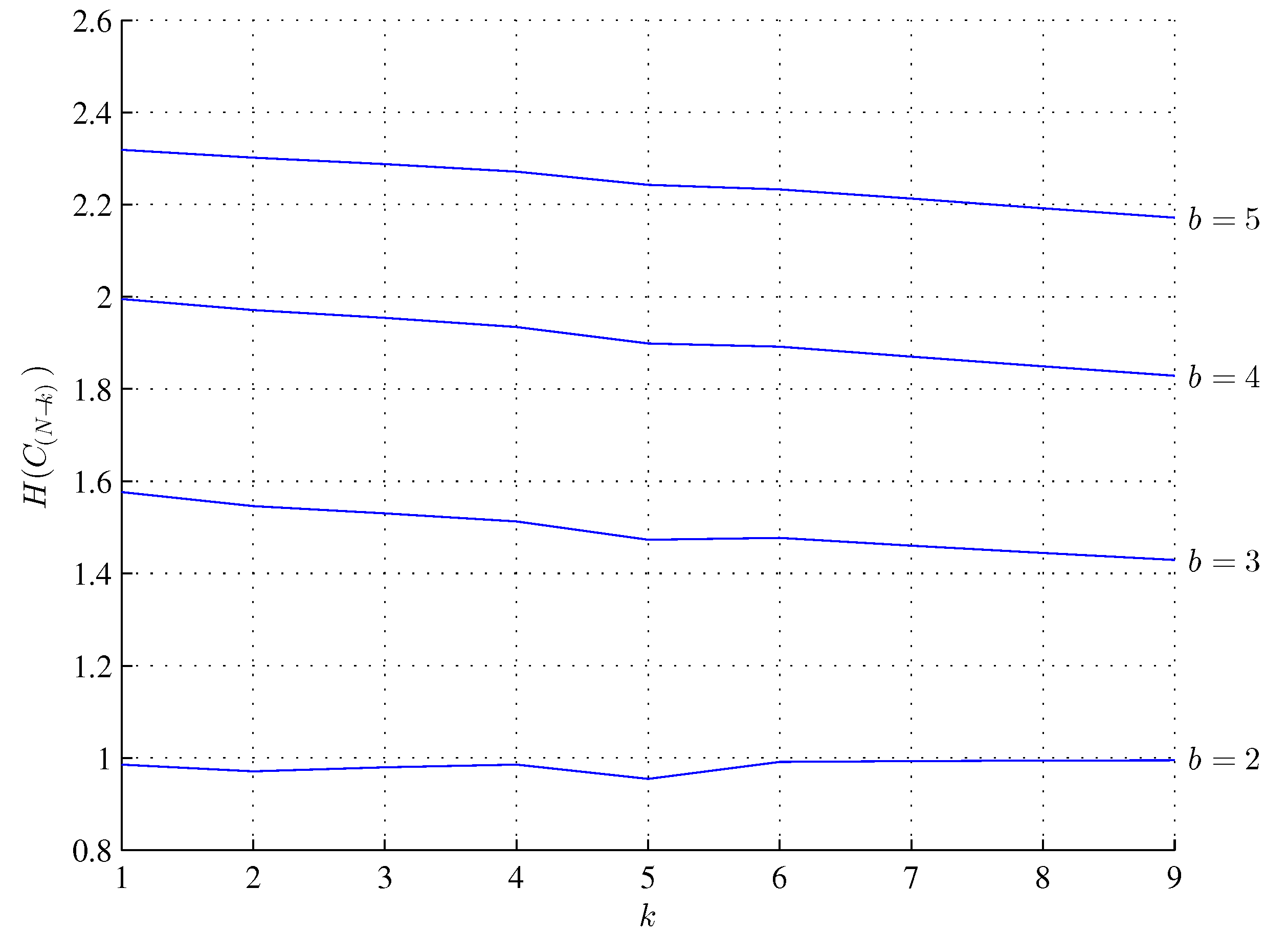

The entropies (

42) and (

48) are shown in

Figure 3. Radix

is the smallest one at which the entropy (

48) is a monotonically decreasing function of

k. For

there is a local entropy minimum for

and for

an additional local entropy minimum for

. Perhaps, the entropy (

48) has other local entropy minima for

and for

.

Conjecture 22.

If and then

or equivalently

where

In other words, if , then ASI increases by one, where N increases by two ( are triangular numbers, OEIS A000217).

First, we note that maximum ASI must rise. If it were constant for

, then at some even larger

N it would inevitably become lower than the minimum ASI bound 2 which also rises, and this would be a contradiction. W.l.o.g. we aim to prove this conjecture for

. We note that inserting any doublet into a

string (

A19) at any position creates a triplet. Using the equation (

10) of Theorem 10 we have

for any step

s if only

. Now, assume that

,

and

,

. Then

The proof of the Conjecture 22 must show the conditions for the equations (

52) and (

53) to hold. We note that the assumption used in the equation (

53) is valid only for

and

. The bounds of Theorems 20 and 21 and Conjecture 22 are illustrated in

Figure 1.

The results thus far led us to a simple method of determining the ASI of a maximum ASI and a minimum ASD string and strengthened our Conjectures 3 and 4 stated in the previous study [

9]. The method is based on unique

-plets and powers of two, as shown in

Table 2. First, a maximum ASI string is sequenced, every two symbols to find the number

of unique adjoining doublets

. In particular, a

string (

A3) or (

A4) contain the maximum of

unique adjoining doublets, a

string (

A13) contains the maximum of

unique adjoining doublets, and so on. In general, a

string contains the maximum of

unique adjoining doublets, where

is given by the relations (

40) or (

45), which is independent of

k.

Subsequently, these doublets form unique adjoining quadruplets, quadruplets form unique adjoining octuples, and so on depending on the length of the string N and the radix b, as there can be at most unique -plets. The columns "last " indicate if the assembled string should be terminated with a single substring of length in descending order. The empty fields in the respective columns for indicate that a given substring can be interpreted as either a "regular" single substring or a last substring if . Furthermore, each step and all last steps are tantamount to one ASD level.

For example, the

string (

A20) of length

for

can be assembled as

Similarly, the

string (

A3) of length

for

can be assembled, as shown in

Table 2 as

Furthermore, for

the method produces the DPI (OEIS

A014701). For example, the string of length

can be assembled in six steps as

where obviously

. However, this is the

exception for

as the ASI of this string is five if it is assembled using doublet

and triplet

.

We further note that the method illustrated in

Table 2 cannot be used to construct the maximum ASI string. For example, both the following two distributions of doublets for

satisfy the distributions of

Table 2. However, only the left one correctly reflects the maximum ASI of the assembled string.

as the right one can be assembled in four steps with

. Similarly, only the top distribution of doublets below correctly reflects the maximum ASI of the assembled string for

as the bottom one can be assembled in six steps with

. Furthermore, this method tends to exaggerate the estimated maximum ASI value, that is,

where

is the ASI of a string

determined by the method illustrated in

Table 2. For example, the first six strings below contain four unique doublets instead of the required three. Therefore

Further research should consider researching the formula equivalent to (

40) that captures a quadruplet repetition, similarly as

captures a doublet repetition.