1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) disease is caused by the acid-fast bacterium,

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (

M. tuberculosis) and is currently the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide due to a single infectious agent. One of the main contributing factors to the burden of the disease is an alarming increase in the number of multidrug-resistant-TB (MDR-TB) cases. Recently, an efficient chemotherapeutic regimen, containing two second-line drugs, namely clofazimine (CFZ) and bedaquiline (BDQ), has been introduced, shortening treatment schedules from 18 - 24 months to 9 - 12 months, also resulting in high treatment success rates (87% - 90% cure rates) [

1,

2,

3,

4].

However, despite these benefits in chemotherapy, CFZ and BDQ have been identified as the two main agents implicated in the development of QT prolongation in patients, which is a risk factor for development of cardiac arrhythmia, leading to cardiac arrest [

2,

3,

5,

6,

7]. Previous studies have shown that both CFZ and BDQ lead to the development of QT prolongation by interfering with K

+ influx of the cardiomyocytes (CMs: cardiac muscle cells) [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], targeting the voltage-gated K

+ channel Kv11.1 (KCNH2: also known as the human Ether-a-go-go-related gene [hERG]) [

7,

13]. In addition to the Kv11.1, the CMs possess several other K

+-uptake transporters, including the Kv1.3 (KCNA3) and the Na

+,K

+-ATPase pump [

9,

10,

14,

15]. However, the effects of both CFZ and BDQ on the activities of these transporters of the cardiac cells have not been reported.

Despite the limited information on the other K

+ transporters of CMs, CFZ and BDQ have been shown to inhibit the Kv1.3 of T lymphocytes [

16] and monocytes [

2,

17,

18,

19]. In addition, CFZ was shown to inhibit the Na

+,K

+-ATPase activity of T lymphocytes [

20]. However, the effects of BDQ on the activity of the Na

+,K

+-ATPase of any type of mammalian cells have not been described.

In the current study, we investigated the effects of both antibiotics on the Na

+,K

+-ATPase activity of isolated CMs, as a potential

in vitro mimic of the mechanism of QT prolongation. The Na

+,K

+-ATPase transporter is a transmembrane, protein complex, found in the cell membranes of all eukaryotic cells [

21]. It is a member of the P-type ATPase class of enzymes, requiring ATP as an energy source for its activity [

22]. Its function is to maintain homeostasis of Na

+ and K

+ ion concentrations, as well as their electrochemical gradients across the plasma membrane [

23], operating as an antiporter, transporting K

+ inwardly in exchange for Na

+ [

24,

25,

26,

27]. It contributes significantly to osmoregulation and maintenance of the resting membrane potential [

27]. Cells use K

+ for maintenance of transmembrane potential (~90 mV) required for activation of various metabolic activities including protein synthesis, osmotic pressure and regulation of pH (acid-base balance) [

28,

29,

30].

In the current study, rat CMs (RCMs) were incubated in the absence and presence of the two antibiotics, individually and in combination. Thereafter, cellular Na+,K+-ATPase activities were determined, followed by measurement of intracellular ATP concentrations, and cellular viability.

2. Results

2.1. Confirmation and Antibiotic Treatments of the RCMs

The sizes and viabilities of the cells were confirmed using the scatter plot generated by the flow cytometer (

Figure 1S). The RCMs were thereafter treated with three concentrations of CFZ and BDQ antibiotics individually, prepared in double dilutions, which were 1.25, 2.5 and 5 mg/L, while the combination assays were treated with mixtures of the two antibiotics prepared at their mid-points (1.25C + 1.25B, 2.5C + 2.5B and 5C + 5B). Based on DMSO being used as a solvent for the antibiotic solutions, two controls were prepared, which included the DMSO-free and DMSO-treated control assays. The antibiotic assays were analysed for determination of the effects of the antibiotics on the Na

+,K

+-ATPase activity, intracellular ATP concentrations and cellular viability. All antibiotic treatment assays were analysed using comparison with the DMSO-treated control system.

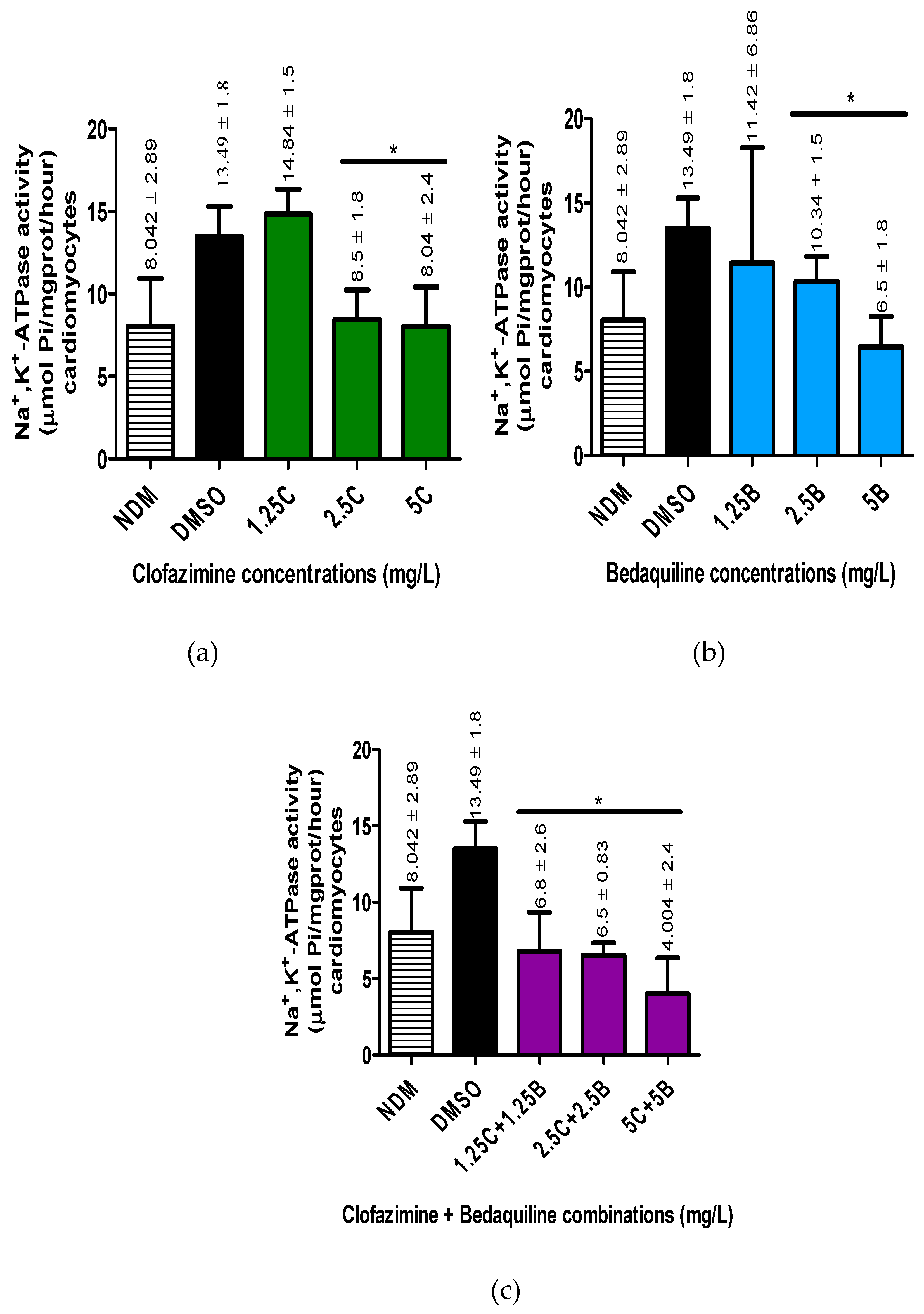

2.2. The Na+,K+-ATPase Activity of the RCMs

The Na

+,K

+-ATPase activity of individual antibiotic-free controls and antibiotic-treated samples were determined following the formula described in the Na

+,K

+-ATPase activity assay kit. All the variables used in the determination of enzyme activity are as shown in

Table S1, Supplementary. The results of the effects of the individual antibiotics on RCM Na

+,K

+-ATPase activity assays are as shown in

Figure 1.

The mean Na+,K+-ATPase activities of the antibiotic-free controls were 8.042 ± 2.89 and 13.49 ± 1.8 µmol Pi/mg prot/hour for the DMSO-untreated and treated controls, respectively, showing an increase in Na+,K+-ATPase activity by treatment of cells with DMSO. The difference in activity between these controls was significant (p = 0.0087).

For antibiotic treatments, both test agents demonstrated inhibitory effects on the activity of Na+,K+-ATPase of the RCMs in a dose-dependent manner. Clofazimine demonstrated inhibitory effects on the Na+,K+-ATPase activity of the RCMs only at the highest concentrations of 2.5 and 5 mg/L, achieving statistically significant differences at both concentrations (p < 0.0043 and < 0.0087, respectively). The inhibitory effects of these two CFZ concentrations resulted in 1.5-fold and 1.75-fold decreases in the Na+,K+-ATPase activity in relation to the controls, respectively. Interestingly, at 1.25 mg/L, CFZ demonstrated an increase in Na+,K+-ATPase activity, which was, however, not statistically significant (p = 0.24).

In the case of BDQ, unlike CFZ, all three concentrations of this agent demonstrated inhibition of RCM Na+,K+-ATPase activity. However, similar to CFZ, BDQ achieved statistically significant inhibitory effects on enzyme activity only at the highest concentrations of 2.5 and 5 mg/L tested (p = 0.0152 and 0.0022, respectively). Exposure of RCMs to these concentrations of BDQ resulted in 1.4-fold and 2.2-fold levels of inhibition of Na+,K+-ATPase activity relative to the controls values, respectively.

Similar to the effects of BDQ, treatment of the RCMs with all of the antibiotic combinations demonstrated inhibitory effects on Na+,K+-ATPase activity, achieving statistical significance at all of combinations tested (p = 0.0022 for all concentrations). The inhibitory effects of these combination sets resulted in 2.1-fold, 2.2-fold and 3.5-fold decreases in activity for 1.25C + 1.25B, 2.5C + 2.5B and 5C + 5B (mg/L) concentrations in relation to the controls, respectively.

In summary, CFZ and BDQ individually and in combination demonstrated dose-response inhibition of the activity of Na+,K+-ATPase of the RCMs. Based on the magnitude of inhibition by the individual antibiotic assays, the highest inhibitory effects were demonstrated by combinations of the two antibiotics, followed by BDQ concentrations while CFZ concentrations demonstrated the least inhibitory effects on enzyme activity.

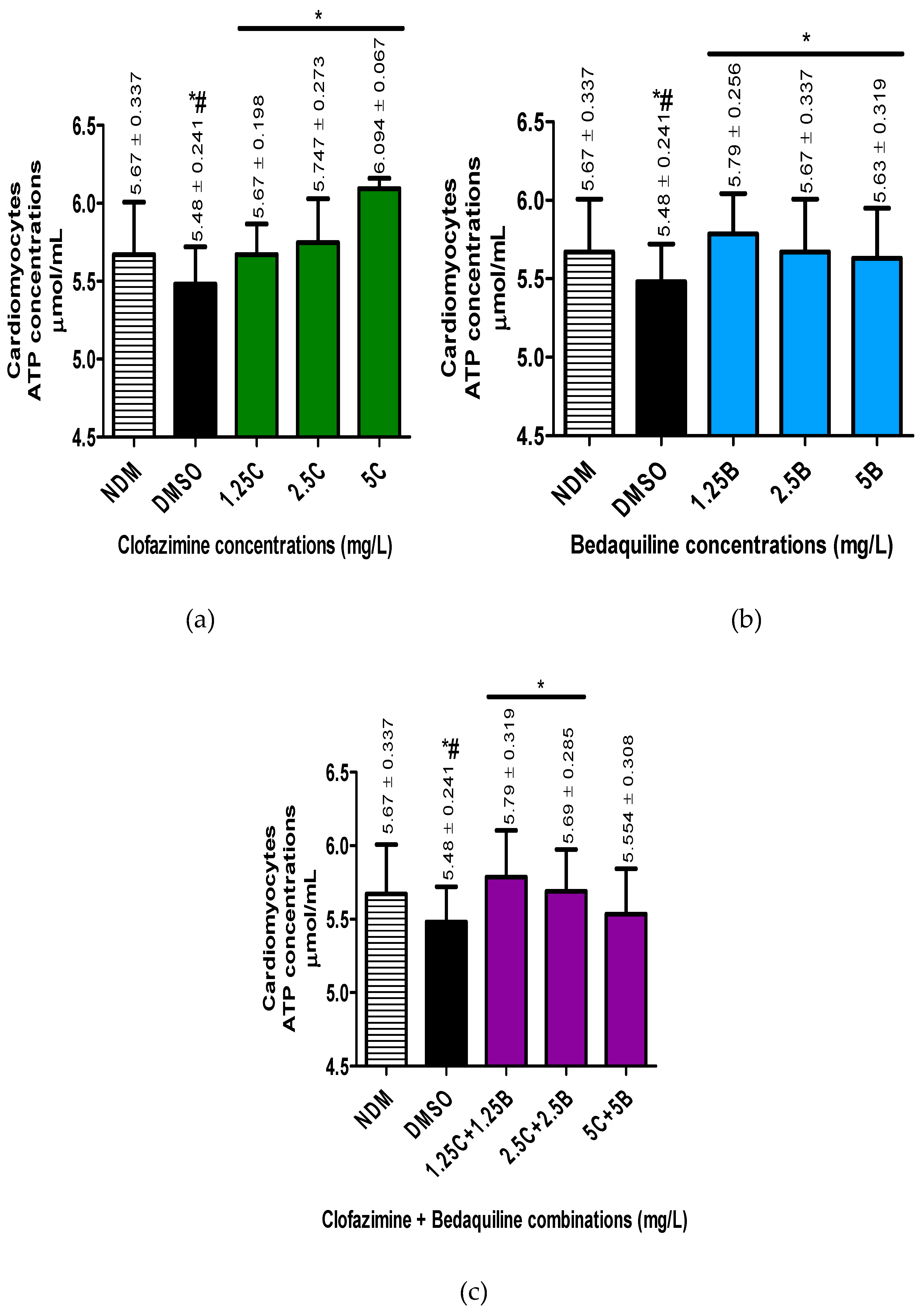

2.3. The Intracellular ATP Concentrations of the RCMs

The concentrations of intracellular ATP in the different samples were determined (µmol/mL) as described in the materials and methods section (

Figure 2).

For the antibiotic-free control systems, the intracellular concentrations of ATP were 5.67 ± 0.337 and 5.48 ± 0.241 µmol/mL, for the DMSO-untreated and treated samples, respectively, showing a decline in ATP concentrations following treatment of cells with DMSO, achieving a statistically significant difference (p = 0.0102).

For the antibiotic treatments, all antibiotic-treated assays demonstrated an increase in ATP concentrations. Clofazimine demonstrated a dose-response increase in ATP concentrations, reaching peak levels at 5 mg/LCFZ. However, the increase in ATP levels was significantly different at all antibiotic concentrations tested (1.25 - 5 mg/L) (p < 0.05).

Similar to CFZ, BDQ demonstrated dose-response increases in intracellular ATP concentrations, which were significantly different from the controls at all concentrations tested, being maximal at 1.25 mg/L in the case of BDQ.

Similar to the individual antibiotics, combinations of the test antibiotics also demonstrated increased intracellular ATP concentrations. However, in contrast to the individual antibiotics, dose-response increases in ATP concentrations were detected only with the first two antibiotic combination sets, viz. 1.25C + 1.25B and 2.5C + 2.5B mg/L and similar to BDQ, being maximal at 125C + 1.25B mg/L.

These results illustrate that treatment of cells with CFZ and BDQ individually or in combinations resulted in increased in intracellular ATP concentrations, presumably due to inhibition of Na+,K+-ATPase.

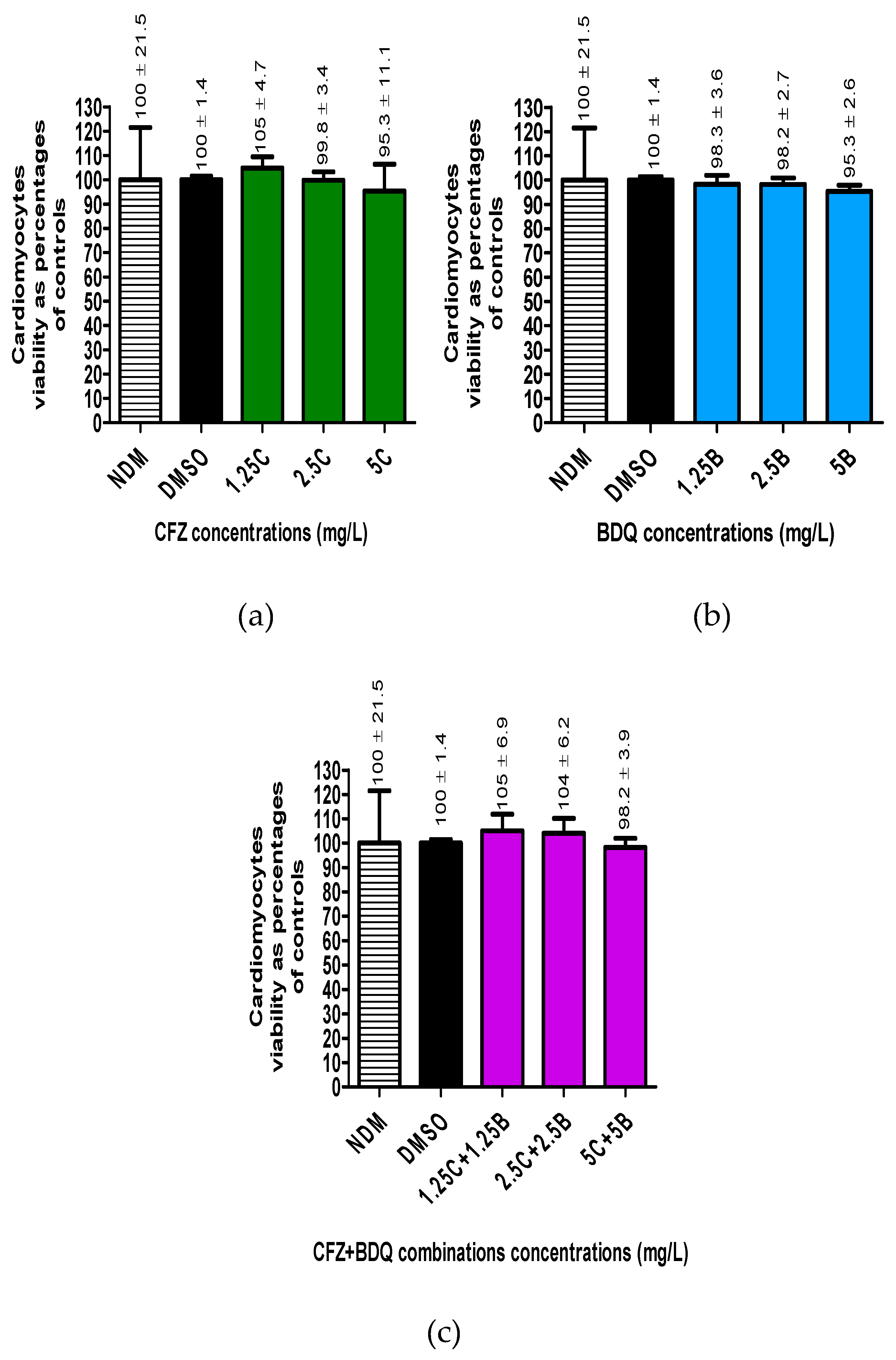

2.4. Viability of the RCMs

Cellular viability for antibiotic-free controls and -treated cells was determined by flow cytometry. The numbers of viable cells in all the assays were determined as a percentage in relation to the DMSO-treated controls (

Figure 3).

The results showed that treatment of cells with DMSO did not significantly change the number of viable cells. Furthermore, treatment of cells with the three antibiotics, either individually or in combinations did not change the number of viable cells, resulting in cellular viabilities ranging between 95% - 100%.

3. Discussion

The application of the multidrug, short course, MDR-TB-treatment regimen has led to several chemotherapeutic successes in the management of MDR-TB patients [

2]. This treatment regimen is administered over a shorter period of 9 - 12 months as opposed to 18 - 24 months with the previous longer MDR-TB treatment regimen. It has also led to improvement in treatment outcomes increasing treatment success rates from 30% - 55% to 87% - 90% [

1,

6]. More importantly, it is associated with low relapse rates in patients [

1,

2,

4,

31].

Despite its beneficial effects, this treatment regimen is also associated with development of adverse events in patients, which differ in severity ranging from mild to fatal [

2]. One of the most severe adverse events is QT prolongation, which leads to fatal cardiac arrhythmia [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Cardiac arrhythmia develops as a result of damage to the cardiac muscle, affecting contraction, resulting in abnormal heart rates [

32,

33]. Among the constituent antibiotics of the MDR-TB, short-course treatment regimen, CFZ and BDQ have been identified as the main antibiotics associated with development of QT prolongation, despite being associated with beneficial therapeutic antimicrobial effects [

2,

13,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

Previous studies have demonstrated that the mechanism of QT prolongation by CFZ and BDQ is via inhibition of K

+ uptake through blockage of the voltage-gated K

+-uptake channel, Kv11.1 of CMs [

13,

42]. However, information on the involvement of these antibiotics on other K

+-uptake transporters of CMs including the Kv1.3 and the Na

+,K

+-ATPase transporters in the mechanisms of QT prolongation has not been described.

In the current study, the potential effects of these antibiotics on the Na

+,K

+-ATPase of the CMs were investigated. Due to challenges in accessing human CMs (HCMs), we used the RCMs in place of the HCMs. The effects of the antibiotics individually and in combination on the Na

+,K

+-ATPase activity of the RCMs were investigated by determining the rates of ATP decomposition by measuring the rate of intracellular Pi release in the absence and presence of the test antibiotics. Based on the utilisation of ATP for the activity of the Na

+,K

+-ATPase pump [

26,

43], the amounts of intracellular ATP were also determined by using a spectrophotometric procedure. Furthermore, the cytotoxic effects of these antibiotics on the RCMs were evaluated by viability determination using PI-based staining flow cytometry.

The results of the current study showed that both CFZ and BDQ individually and in combination, have inhibitory effects on the activity of the Na+,K+-ATPase of RCMs. However, the degree of inhibition by these antibiotics differed. Clofazimine demonstrated inhibitory effects on the Na+,K+-ATPase activity only at higher concentrations of 2.5 and 5 mg/L, which were also statistically significant. These inhibitory effects of higher concentrations of CFZ on Na+,K+-ATPase activity coincided with statistically significant elevations in cellular ATP concentrations, illustrating decreased utilisation of ATP as a consequence of attenuation of the activity of the Na+,K+-ATPase transporter, highlighting the Na+,K+-ATPase transporter as the highest consumer of cellular ATP. Despite exhibiting this inhibitory effect on Na+,K+-ATPase activity, CFZ did not demonstrate any significant change in cellular viability, demonstrating absence of cytotoxicity, showing that the inhibition in enzymatic activity is not dependent of the number of viable cells.

Unlike CFZ, BDQ demonstrated a dose-related inhibitory effect on the Na+,K+-ATPase of the RCMs at all concentrations tested, indicating that BDQ is more potent than CFZ with respect to inhibition of this enzyme. However, like CFZ, BDQ achieved significant inhibitory effects on the enzyme activity at the highest concentrations of 2.5 and 5 mg/L, which coincided with elevated levels of ATP at all BDQ concentrations tested. However, the ATP concentrations declined somewhat at these highest concentrations of BDQ (2.5 and 5 mg/L), suggesting the simultaneous presence of inhibitory effects of BDQ on ATP synthesis. Despite the defective ATP synthesis coupled with inhibition of Na+,K+-ATPase activity, similar to CFZ, BDQ did not show any significant effect on the cellular viability, demonstrating absence of cytotoxicity on the RCMs in the current experimental settings.

The most potent inhibitory effects of the antibiotics on the Na

+,K

+-ATPase activity of the RCMs were observed with the antibiotic combination assays, which unlike the individual antibiotics, attained statistical significance at all combinations concentrations tested (1.25C + 1.25B to 5C + 5B mg/L). Inhibition of enzymatic activity was associated with increased intracellular ATP levels, which were dose-related, with the highest ATP concentrations being detected at the lowest concentrations of the test antibiotic combinations (1.25C + 1.25B mg/L) declining at higher concentrations of combinations in a dose-dependent manner. The inhibitory effects of the combination assays on the ATP concentrations may be attributable to the presence of BDQ as it demonstrated similar effects of attenuating ATP levels at higher concentrations on the RCMs when operating alone (

Figure 2). Similar to the individual antibiotics, despite a high degree of attenuation of Na

+,K

+-ATPase activity, the inhibitory effects of the antibiotic combinations did not lead to cellular cytotoxicity, possibly insignificant damage to the CMs, even when the antibiotics are used in combination during antimicrobial chemotherapy, although this may differ with prolonged treatment with CFZ and/or BDQ, as opposed to the short incubation times used in the current

in vitro study

The current study is the first to report the inhibitory effects of both CFZ and BDQ individually and in combination on the Na

+,K

+-ATPase of CMs, which is a potential augmentative mechanism of development of QT prolongation. Previous studies have demonstrated that development of prolonged QT intervals [

41,

42,

44] as a result of attenuation of Na

+,K

+-ATPase of the CMs caused by other drugs was associated with cardiotoxicity [

27,

45]. However, in the current study, the inhibition of the Na

+,K

+-ATPase activity in the absence of cytotoxicity may not exclude the involvement of these two antibiotics in cardiotoxicity, but may be due to the experimental design, involving a short 15 min exposure time of the antibiotics to the cells as mentioned above. Additionally, the discrepancy might be as a result of the use of the RCMs which differ in characteristics from HCMs [

46,

47]. Nonetheless, the findings of the current study, highlight attenuation of Na

+,K

+-ATPase activity as a potential novel mechanism by which CFZ and BDQ contribute to development of QT prolongation during anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy, leading to cardiac arrhythmia.

In conclusion, in addition to previous findings, which identified the Kv11.1 K+-uptake channels of the CMs as targets of CFZ and BDQ, the results of the current study have also identified the Na+,K+-ATPase of the CMs as a potential target of these antibiotics, suggesting the inhibitory effects of the antibiotics on the Na+,K+-ATPase as a possible contributor to development of QT prolongation in TB patients. These findings are indicative of possibly shared, as well as distinct, molecular/biochemical mechanisms of CFZ- and BDQ-mediated interference with the activity of Na+,K+-ATPase, in the development of cardiac dysfunction, which remain to be elucidated. These results therefore highlight the necessity of a careful selection of antibiotics in future design of short-course, MDR-TB regimens.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.1.1. Antibiotics and Other Chemicals

The antibiotics investigated in the current study were CFZ and BDQ. Clofazimine was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) while BDQ was obtained from Adooq Bioscience (York, UK). The antibiotics were dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) and used at final concentrations of 1.25 - 5 mg/L, individually and in combination, in all of the experimental assays. The DMSO was used at a final concentration of 0.1% as solvent control in all the control systems.

Unless otherwise stated, all other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Lasec (Cape Town, RSA) and Whitehead Scientific (Cape Town, RSA). Propidium iodide (PI) dye [deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) Prep Stain], used for determining cell viability, was purchased from Beckman Coulter (Brea, CA, USA).

4.1.2. Assay Kits

The assay kits used in the current study include the Na+,K+-ATPase activity kit (Elabscience Biotechnology Inc., Houston, TX, USA) for determination of Na+,K+-ATPase activity, as well as the ATP colorimetric assay kit (Abcam, ab282930) (Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA) for quantification of cellular ATP concentrations.

4.1.3. RCMs and Growth Media

Rat cardiomyocytes (RCMs, were sourced from Lonza Walkersville, Inc., Walkersville, MD, USA). They were cryopreserved and stored at -196 °C in liquid nitrogen.

The RCM growth medium (RCGM) was used for preparation of the RCMs. This was prepared by using the RCGM bullet Kit (200 mL of RCM basal medium (RCBM) and the RCGM SingleQuots kit) (Lonza Biosciences, Walkerville, MD, USA). The RCGM was prepared by mixing the ingredients of the RCGM SingleQuots kit (300 µL of antibiotic mixture: gentamycin sulphate and amphotericin B), 18 mL of horse serum from Equidae and 18 mL of foetal bovine serum) with 200 mL of the RCBM.

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Preparation of the RCMs

A vial containing 1 mL of RCM cells was taken from liquid nitrogen storage and the cells thawed by gentle rubbing of the vial with fingers for approximately two - three minutes. The cells were then transferred into a 15 mL tube and RCGM medium added stepwise and the cell suspension mixed by gently inverting the 15 mL tube. The cell suspension was then incubated at 37 °C for 3.5 h in the presence of 5% CO2. The RCGM medium was removed from the cells by centrifugation at 335 x g, at 4 °C for 10 min and the supernatant thereafter discarded. The cell pellet was resuspended in pre-warmed saline solution (0.9%, NaCl). The characteristics of the cells with respect to size and viability were determined by flow cytometry by mixing 50 µL of cell suspension with 450 µL of propidium iodide and the mixture analysed using a FC500 Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA).

4.2.2. Antibiotic Reaction Assays

Approximately 3 x 105 cells/ mL were transferred into different 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes. Thereafter, 1 µL of varying stock concentrations of antibiotics (CFZ, BDQ and their combinations) were added to the cells. The antibiotic concentrations were prepared in double dilutions ranging from 1.25 - 5 mg/L for both CFZ and BDQ. For combination assays, the individual antibiotics were mixed at their midpoint concentrations [e.g ½ (1.25 mg/L CFZ) + ½ (1.25 mg/L BDQ)]. In reaction mixtures, the concentrations for each antibiotic or their combinations are shown by a number and symbol C, B or C + B representing CFZ, BDQ individually or their combinations, respectively, such as 1.25C, 1.25B or 1.25C + 1.25B. Two antibiotic-free controls, solvent-free (no DMSO) and DMSO-treated, prepared by adding 1 µL of 100% DMSO yielding 0.1% DMSO, were included. The suspensions were mixed by inverting the tubes and the mixtures incubated at 37 °C for 15 minutes in the presence of 5% CO2. The reactions were stopped by placing the tubes on ice for one min and the contents analysed for Na+,K+-ATPase activity, ATP quantification and cellular viability.

4.2.3. Na+,K+-ATPase Activity

The enzymatic activity of Na

+,K

+-ATPase was determined according to the method of Chen et al. [

48]. Detection of enzymatic activity is based on Na

+,K

+-ATPase-mediated decomposition of ATP to produce ADP and Pi. The amount of Pi is then quantitated and used to calculate the Na

+,K

+-ATPase activity. The ADP and Pi are extracted from the cells as protein constituents.

4.2.3.1. Protein Extraction

Protein samples used for measurement of Na+,K+-ATPase enzymatic activity were extracted from the control and antibiotic-treated RCMs using the vortexing method. Following centrifugation at 335 x g at 4 °C for 10 min, the supernatants were discarded and the pellets vortexed followed by addition of 500 µL saline solution. Approximately 500 µL of beads (2 mm diameter) were added to each cell suspension and the mixtures vortexed for a maximum period of five min, with cooling on ice every two minutes. The cell suspensions were then centrifuged at 335 x g at 4 °C for one minute and approximately 500 µL of the supernatants, containing the protein extracts, were harvested. Protein concentrations of the samples were determined at 280 nm using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) and recorded as mg/mL.

4.2.3.2. Na+,K+-ATPase Activity

The protein extracts were also used for determination of Na+,K+-ATPase activity. The Na+,K+-ATPase reactions were performed using the method based on the colorimetric detection of the released free Pi.

The reaction mixture tubes were incubated at 37 °C for 10 minutes. Thereafter, protein precipitator reagent was added to precipitate the proteins to promote release of free Pi. The tubes were vortexed and centrifuged at 8,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4 °C and the supernatants harvested for colorimetric detection of Pi.

Reaction mixtures for each sample (control and antibiotic treated) were prepared by mixing 20 µL of each sample with 200 µL of chromogenic working solution. Standard reaction mixtures (containing known standard Pi concentrations) were also prepared by mixing individual standards with chromogenic working solutions. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 15 minutes, followed by optical density (OD) measurements at 660 nm using a PowerWavex spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, CA, USA). The optical densities (ODs) of the standard Pi concentrations were used for generation of the standard curve.

The Na+,K+-ATPase activities for each sample were calculated using the following formula:

Na+,K+-ATPase activity (µmol Pi/mg protein/hour) = (ΔA660-b) / a x V1 / (Cpr x V2) / t x f,

where:

y: ODstandard – ODblank (ODblank is the OD value when the standard concentration is 0)

x: The concentration of the standard

a: The slope of the standard curve

ΔA660: ODsample – ODcontrol

V1: The total volume of reaction system (0.25 mL)

V2: The volume of added sample (0.1 mL)

t: The time of enzymatic reaction (1/6 hours)

Cpr: Concentration of protein in sample (mg protein/mL)

f: Dilution factor of sample before tested.

4.2.4. ATP Concentration Determination

Quantification of ATP was determined using the ATP colorimetric assay kit (Abcam, ab282930). The assay is based on phosphorylation of glycerol (transfer of phosphate group to glycerol from ATP) using glycerol kinase, producing ADP and glycerol phosphate. The procedure involves extraction of ATP from lysed cells, followed in this case by deproteinization and ultimately quantification of ATP.

4.2.4.1. ATP Extraction

The control and antibiotic -treated reaction mixtures were centrifuged at 4,833 x g, for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were discarded and the pellets vortexed. Thereafter, 50 μL of ice-cold ATP assay buffer (supplied in the kit) was added and vortexed to lyse the cells, followed by centrifugation of the mixtures at 4,833 x g for 10 min at 4 °C. About 100 µL of each lysate was harvested and transferred into separate 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes. These samples were placed on ice immediately to prevent consumption and utilisation of ATP by enzymes present in the samples. The proteins (and enzymes) were then removed from the supernatant lysates by a deproteinisation procedure performed using a spin column method. A 100 μL volume of the lysate of each sample was transferred immediately onto a spin column (Qiagen RNeasy mini kit, Hilden, DE, Germany), which was placed in a new 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. The tubes were centrifuged immediately at 4,833 x g for 10 min, at 4 °C and the eluates collected.

4.2.4.2. ATP Quantification

The deproteinated samples were thereafter used for ATP assay concentration determination. The concentrations of ATP in the eluate samples were determined using the ATP reaction assay kit following the manufacturers’ instructions, with no modification. Briefly, the deproteinated samples and the standard ATP concentrations samples were used for preparation of reaction mixtures in a 96-well plate to final volumes of 15 µL/ well. The 96-well plate was then incubated for 45 minutes, at room temperature, in the dark and the ODs of the contents of the wells determined at 570 nm. The OD values of the standard concentrations were used to plot the standard curve, which was used to determine the ATP concentrations in samples.

The ATP concentration for each sample was determined using the formula:

where:

B = ATP concentration in the reaction well from standard curve (nmol)

V = the sample volume added into sample wells (µL)

D = the dilution factor

4.2.5. Viability of the RCMs

To determine the cytotoxic potential of the test antibiotics, viability of the cells in the antibiotic-treated and control reaction mixtures (Section 2.2.2) was determined by using the PI staining method. The PI dye binds to the nuclei of lysed cells forming a nuclear-PI complex, which fluoresces, but does not to bind to live cells, which it fails to penetrate.

A 50 μL aliquot of each sample, either the control or various antibiotic-treated systems (Section 2.2.2), was transferred into a 5 mL flow tube and 450 µL of PI reagent (DNA Prep Stain, Beckman Coulter, USA) was added. The mixture in the flow tube was vortexed and inserted immediately into the FC500 Flow Cytometer instrument (Beckman Coulter, USA) and viability determined according to the resultant scatter graph. The dead and live cells were located in different positions on the scatter chart, resulting in positioning of live cells closer to zero on the X-axis, while dead cells were positioned further away from zero in the positive direction.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed on all data using GraphPad Instant 3 Programme (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The results of each series of experiments were expressed as the mean values ± standard deviations. Due to all antibiotic mixtures prepared in DMSO, statistical significance was calculated between antibiotic-treated and DMSO-treated control systems using the Mann-Whitney U-test for comparison of non-parametric data. A P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure 1S: Flow cytometric scatter plot demonstrating the size of the rat cardiomyocytes (RCMs). The RCMs are large cells, with most of them being positioned between 105 and 106 coordinates on the Y-axis and zero and 500 on the X-axis. The majority of the cells are positioned closer to zero on the X-axis showing that they are viable. Figure 2S: The protein concentrations (mg/mL) of antibiotic-free and antibiotic-treated RCMs, extracted using vortex methods, which were used for the Na+,K+-ATPase activity determination, measured using nanodrop mg/mL. Abbreviations: B: bedaquiline; C, clofazimine; DMSO, dimethylsulphoxide; NDM, no DMSO. Figure 3S: The standard curve for inorganic phosphate (Pi) concentrations. The slope of the graph was Y = ax + b with a = 0.4551 ± 0.01140, while b = 0.05283 ± 0.01926. Figure S4: The standard curve for determination of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) concentrations. The slope of the standard curve was y = ax + b = 0.013 ± 0.003x + 0.005 ± 0.0048. Table 1S: The variables used for determination of the Na+,K+-ATPase activity formula

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, R.A, G.T. and M.C.; methodology, K.M., M.V., M.P., H.S., P.M., M.S., N.H., R.A., G.T., M.C.; investigation, K.M., M.C., R.A., M.S., M.P., N.H., M.V., P.M., H.S., G.T.; formal analysis, K.M., H.S., M.P., P.M., N.H., M.V., M.S., G.T., R.A., M.C.; validation, K.M., H.S., M.S., G.T., R.A., M.C.; writing original draft, K.M., M.C., R.A.; writing, review and editing, K.M., M.S., H.S., R.A., M.C.; Supervision, M.C., R.A., M.S., P.M., H.S., G.T. Funding acquisition, M.C., R.A., G.T., M.S., P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Health Laboratory Services Research Trust (NHLSRT), grant No. 94648 and the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) under a Self-Initiated Research (SIR) Grant 2022. Mr KMS Mmakola also received financial assistance from Biomerieux company, South Africa. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee, University of Pretoria, with a specific ethical approval reference Nos.: 545/2017 and 291/2021, under the umbrella project with ethical approval reference No.: 387/2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the datasets generated for this study are included in the article and supplementary material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Van Deun: A.; Maug, A.K.; Salim, M.A.; Das, P.K.; Sarker, M.R.; Daru, P.; Rieder, H.L. Short, highly effective, and inexpensive standardized treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010, 182, 684-692. [CrossRef]

- Cholo, M.C.; Mothiba, M.T.; Fourie, B.; Anderson, R. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic efficacies of the lipophilic antimycobacterial agents clofazimine and bedaquiline. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017, 72, 338-353. [CrossRef]

- Ndjeka, N.; Ismail, N.A. Bedaquiline and clofazimine: Successes and challenges. Lancet Microbe 2020, 1, 139-140. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2021. 2021, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240037021.

- Dooley, K.E.; Rosenkranz, S.L.; Conradie, F.; Moran, L.; Hafner, R.; Von Groote-Bidlingmaier, F.; Lama, J.R.; Shenje, J.; De Los Rios, J.; Comins, K.; Morganroth, J.; Diacon, A.H.; Cramer, Y.S.; Donahue, K.; Maartens, G. QT effects of bedaquiline, delamanid, or both in patients with rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis: A phase 2, open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2021, 21, 975-983. [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Pereiro, J.; Sánchez-Montalvá, A.; Aznar, M.L.; Espiau, M. MDR tuberculosis treatment. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022, 58, 188. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G.; Bern, H.; Chiang, C.Y.; Goodall, R.L.; Nunn, A.J.; Rusen, I.D.; Meredith, S.K. QT prolongation in the STREAM stage 1 Trial. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2022, 26, 334-340. [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, O.; Bhardwaj R.D.; Bernard, S.; Zdunek, S.; Barnabé-Heider, F.; Walsh, S.; Zupicich, J.; Alkass, K.; Buchholz, B.A.; Druid, H.; Jovinge, S.; Frisén, J. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science 2009, 324, 98-102. DOI: 10.1126/science.1164680 .

- Wulff, H.; Castle, N.A.; Pardo, L.A. Voltage-gated potassium channels as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2009, 8, 982-1001. [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.P.; Perrin, M.J.; Heide, J.; Campbell, T.J.; Mann, S.A.; Vandenberg, J.I. Kinetics of drug interaction with the Kv11.1 potassium channel. Mol Pharmacol 2014, 85, 769-776. [CrossRef]

- Borin, D.; Pecorari, I.; Pena, B.;, Sbaizero, O. Novel insights into cardiomyocytes provided by atomic force microscopy. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2018, 73, 4-12. DOI: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.07.003 .

- Liu, X.; Pu, W.; He, L.; Li, Y.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, K.; Huang, X.; Weng, W.; Wang, Q.D.; Shen, L.; Zhong, T.; Sun, K.; Ardehali, R.; He, B.; Zhou, B. Cell proliferation fate mapping reveals regional cardiomyocyte cell-cycle activity in subendocardial muscle of left ventricle. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 57-84. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Jadhav, H.; Shinde, Y.; Jagtap, V.; Girase, R.; Patel, H. Optimizing bedaquiline for cardiotoxicity by structure based virtual screening, DFT analysis and molecular dynamic simulation studies to identify selective MDR-TB inhibitors. In Silico Pharmacol 2021, 9, 23. DOI: 10.1007/s40203-021-00086-x .

- Kang, J.A.; Park, S.H.; Jeong, S.P.; Han, M.H.; Lee, C.R.; Lee, K.M.; Kim, N.; Song, M.R.; Choi, M.; Ye, M.; Jung, G.; Lee, W.W.; Eom, S.H.; Park, C.S.; Park, S.G. Epigenetic regulation of KCNA3-encoding Kv1.3 potassium channel by cereblon contributes to regulation of CD4+ T-cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016, 113, 8771-8776. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Shapiro, J.I. The physiological and clinical importance of sodium potassium ATPase in cardiovascular diseases. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2016, 27, 43-49. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.R.; Pan, F.; Parvez, S.; Fleig, A.; Chong, C.R.; Xu, J.; Dang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, H.; Penner, R.; Liu, J.O. Clofazimine inhibits human Kv1.3 potassium channel by perturbing calcium oscillation in T lymphocytes. PLoS One 2008, 3, 4009-4009. [CrossRef]

- Leanza, L.; Trentin, L.; Becker, K.A.; Frezzato, F.; Zoratti, M.; Semenzato, G.; Gulbins, E.; Szabo, I. Clofazimine, Psora-4 and PAP-1, inhibitors of the potassium channel Kv1.3, as a new and selective therapeutic strategy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia 2013, 27, 1782-1785. [CrossRef]

- Leanza, L.; O’reilly, P.; Doyle, A.; Venturini, E.; Zoratti, M.; Szegezdi, E.; Szabo, I. Correlation between potassium channel expression and sensitivity to drug-induced cell death in tumor cell lines. Curr Pharm Des 2014, 20,189-200. [CrossRef]

- Faouzi, M.; Starkus, J.; Penner, R. State-dependent blocking mechanism of Kv1.3 channels by the antimycobacterial drug clofazimine. Br J Pharmacol 2015, 172, 5161-5173. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.; Smit, M.J. Clofazimine and B669 inhibit the proliferative responses and Na+,K+-adenosine triphosphatase activity of human lymphocytes by a lysophospholipid-dependent mechanism. Biochem Pharmacol 1993, 46, 2029-2038. [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.L.; Yu, Z.L.; Lou, J.C.; Ma, X.C.; Zhang, B. Update on the effects of the sodium pump α1 subunit on human glioblastoma: from the laboratory to the clinic. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2018, 27, 753-763. [CrossRef]

- Felippe Gonçalves-De-Albuquerque, C.; Ribeiro Silva, A.; Ignácio Da Silva, C.; Caire Castro-Faria-Neto, H.; Burth, P. Na+/K+ pump and beyond: Na+,K+-ATPase as a modulator of apoptosis and autophagy. Molecules 2017, 22, 578. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D.J.; Bijlani, S.; De Sautu, M.; Spontarelli, K.; Young, V.C.; Gatto, C.; Artigas, P. FXYD protein isoforms differentially modulate human Na+/K+ pump function. J Gen Physiol 2020, 152, e202012660. [CrossRef]

- Rindler, T.N.; Lasko, V.M.; Nieman, M.L.; Okada, M.; Lorenz, J.N.; Lingrel, J.B. Knockout of the Na+,K+-ATPase α2-isoform in cardiac myocytes delays pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013, 304, 1147-1158. [CrossRef]

- Sepp, M.; Sokolova, N.; Jugai, S.; Mandel, M.; Peterson, P.; Vendelin, M. Tight coupling of Na+,K+-ATPase with glycolysis demonstrated in permeabilized rat cardiomyocytes. PLoS One 2014, 9, 994-1013. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ge, N.; Huang, T.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H. Sodium pump alpha-2 subunit (ATP1α2) alleviates cardiomyocyte anoxia-reoxygenation injury via inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress-related apoptosis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2018, 96, 515-520. [CrossRef]

- Bejček, J.; Spiwok, V.; Kmoníčková, E.; Rimpelová, S. Na+/K+-ATPase Revisited: On its mechanism of action, role in cancer, and activity modulation. Molecules 2021, 28, 1905. [CrossRef]

- Parikh, M.; Webb, S.T. Cations: Potassium, calcium, and magnesium. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care and Pain 2012, 12, 195-198. [CrossRef]

- McDonough, A.A.; Youn, J.H. Potassium homeostasis: The knowns, the unknowns, and the health benefits. Physiology (Bethesda) 2017, 32, 100-111. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, R.; Tung, L. Contribution of potassium channels to action potential repolarization of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Br J Pharmacol 2019, 176, 2780-2794. [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Pang, Y.; Jing, W.; Liu, P.; Wu, T.; Cai, C.; Shi, J.; Qin, Z.; Yin, H.; Qiu, C.; Li, C.; Xia, Y.; Chen, W.; Ye, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, G.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Chu, L.; Zhu, M.; Xu, T.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Du, Y.; Wang, J.; Chu, N.; Xu, S. Clofazimine improves clinical outcomes in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Microbiol Infect 2019, 25, 190-195. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhu, W.; Schurig-Briccio, L.A.; Lindert, S.; Shoen, C.; Hitchings, R.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Baig, N.; Zhou, T.; Kim, B.K.; Crick, D.C.; Cynamon, M.; Mccammon, J.A.; Gennis, R.B.; Oldfield, E. Antiinfectives targeting enzymes and the proton motive force. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015, 112, 7073-7082. [CrossRef]

- Pontali, E.; Sotgiu, G.; Tiberi, S.; Ambrosio, L.; Centis, R.; Migliori, G.B. Cardiac safety of bedaquiline: A systematic and critical analysis of the evidence. Eur Respir J 2017, 50, 1701462. [CrossRef]

- Cumberland, M.J.; Riebel, L.L.; Roy, A.; O’shea, C.; Holmes, A.P.; Denning, C.; Kirchhof, P.; Rodriguez, B.; Gehmlich, K. Basic research approaches to evaluate cardiac arrhythmia in heart failure and beyond. Front physiol 2022, 13, 63-66. [CrossRef]

- Desai D.S.; Hajouli S. Arrhythmias. 2023 Jun 5. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024, PMID: 32644349.

- Guglielmetti, L.; Jaspard, M.; Le Dû, D.; Lachâtre, M.; Marigot-Outtandy, D.; Bernard, C.; Veziris, N.; Robert, J.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Caumes, E.; Fréchet-Jachym, M. Long-term outcome and safety of prolonged bedaquiline treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur Respir J 2017, 49, 1601-1679. [CrossRef]

- Ndjeka, N.; Schnippel, K.; Master, I.; Meintjes, G.; Maartens, G.; Romero, R.; Padanilam, X.; Enwerem, M.; Chotoo, S.; Singh, N.; Hughes, J.; Variava, E.; Ferreira, H.; Te Riele, J.; Ismail, N.; Mohr, E.; Bantubani, N.; Conradie, F. High treatment success rate for multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis using a bedaquiline-containing treatment regimen. Eur Respir J 2018, 52, 1801528. [CrossRef]

- Borisov, S.; Danila, E.; Maryandyshev, A.; Dalcolmo, M.; Miliauskas, S.; Kuksa, L.; Manga, S.; Skrahina, A.; Diktanas, S.; Codecasa, L.R.; Aleksa, A.; Bruchfeld, J.; Koleva, A.; Piubello, A.; Udwadia, Z.F.; Akkerman, O.W.; Belilovski, E.; Bernal, E.; Boeree, M.J.; Cadiñanos Loidi, J.; Cai, Q.; Cebrian Gallardo, J.J.; Dara, M.; Davidavičienė, E.; Forsman, L.D.; De Los Rios, J.; Denholm, J.; Drakšienė, J.; Duarte, R.; Elamin, S.E.; Escobar Salinas, N.; Ferrarese, M.; Filippov, A.; Garcia, A.; García-García, J.M.; Gaudiesiute, I.; Gavazova, B.; Gayoso, R.; Gomez Rosso, R.; Gruslys, V.; Gualano, G.; Hoefsloot, W.; Jonsson, J.; Khimova, E.; Kunst, H.; Laniado-Laborín, R.; Li, Y.; Magis-Escurra, C.; Manfrin, V.; Marchese, V.; Martínez Robles, E.; Matteelli, A.; Mazza-Stalder, J.; Moschos, C.; Muñoz-Torrico, M.; Mustafa Hamdan, H.; Nakčerienė, B.; Nicod, L.; Nieto Marcos, M.; Palmero, D.J.; Palmieri, F.;Papavasileiou, A.; Payen, M.C.; Pontarelli, A.; Quirós, S.; Rendon, A.; Saderi, L.; Šmite, A.; Solovic, I.; Souleymane, M.B.; Tadolini, M.; Van Den Boom, M.; Vescovo, M.; Viggiani, P.; Yedilbayev, A.; Zablockis, R.; Zhurkin, D.; Zignol, M., Visca, D.; Spanevello, A.; Caminero, J.A.; Alffenaar, J.W.; Tiberi, S.; Centis, R.; D’ambrosio, L.; Pontali, E.; Sotgiu, G.; Migliori, G.B. Surveillance of adverse events in the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis: First global report. Eur Respir J 2019, 54, 1901522. [CrossRef]

- Kashongwe, I.M.; Mawete, F.; Mbulula, L.; Nsuela, D.J.; Losenga, L.; Anshambi, N.; Aloni, M.; Kaswa, M.; Kayembe, J.M.N.; Umba, P.; Lepira, F.B.; Kashongwe, Z.M. Outcomes and adverse events of pre- and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis patients in Kinshasa, Democratique Republic of the Congo: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 2020, 15, 236-264. [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.Y.; Prieto, A.; Bogati, H.; Sannino, L.; Akai, N.; Marquardt, T. Adverse events using shorter MDR-TB regimens: Outcomes from Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea. Public Health Action. 2021, 11, 2-4. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y; Nakamura, I; Takebayashi, Y; Watanabe, H. A fatal case of repeated ventricular fibrillation due to torsade de pointes following repeated administration of metoclopramide. Clin Case Rep 2022, 10, 6213. [CrossRef]

- Olona, A.; Hateley, C.; Guerrero, A.; Ko, J.H.; Johnson, M.R.; Anand, P.K.; Thomas, D.; Gil, J.; Behmoaras, J. Cardiac glycosides cause cytotoxicity in human macrophages and ameliorate white adipose tissue homeostasis. Br J Pharmacol 2022, 179, 1874-1886. [CrossRef]

- Laursen, M.; Gregersen, J.L.; Yatime, L.; Nissen, P.; Fedosova, N.U. Structures and characterization of digoxin- and bufalin-bound Na+,K+-ATPase compared with the ouabain-bound complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015, 112, 1755-1760. [CrossRef]

- Pott, A.; Bock, S.; Berger, I.M.; Frese, K.; Dahme, T.; Keßler, M.; Rinné, S.; Decher, N.; Just, S.; Rottbauer, W. Mutation of the Na+,K+-ATPase ATP1a1a.1 causes QT interval prolongation and bradycardia in zebrafish. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2018, 20, 42-52. [CrossRef]

- Shattock, M.J.; Ottolia, M.; Bers, D.M.; Blaustein, M.P.; Boguslavskyi, A.; Bossuyt, J.; Bridge, J.H.; Chen-Izu, Y.; Clancy, C.E.; Edwards, A.; Goldhaber, J.; Kaplan, J.; Lingrel, J.B.; Pavlovic, D.; Philipson, K.; Sipido, K.R.; Xie, Z.J. Na+/Ca2+ exchange and Na+,K+-ATPase in the heart. Physiol J 2015, 593, 1361-1382. [CrossRef]

- Liess, C.; Radda, G.K.; Clarke, K. Measurement of cardiomyocyte diameter in the isolated rat heart using diffusion-weighted H-MRS: changes with ischaemia. Proc Intl Sot Mag Reson Med 2000, 8, 468-468, https://cds.ismrm.org/ismrm-2000/PDF2/0468.pdf.

- Kadota, S.; Pabon, L.; Reinecke, H.; Murry, C.E. In vivo maturation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in neonatal and adult rat hearts. Stem Cell Reports 2017, 8, 278-289. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; Yang, M.; Xin, G.; Cui, W.; Xie, Z.; Silverstein, R.L. Cardiotonic steroids stimulate macrophage inflammatory responses through a pathway involving CD36, TLR4 and Na+,K+-ATPase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017, 37, 1462-1469. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The Na+,K+-ATPase activities (µmol Pi/mg prot/hour) of the RCMs treated with varying concentrations of a) CFZ and b) BDQ alone and c) in combination. Statistical significance, representing p ≤ 0.05, is shown by *. The P value representing statistical difference between NDM and DMSO antibiotic-free controls is denoted by #. The p value determined between the NDM and DMSO-treated controls was 0.0087. For the antibiotic treatment assays the p values were: for CFZ = 0.24, 0.0043 and 0.0087 for 1.25C, 2.5C and 5C; for BDQ = > 0.99, 0.0152 and 0.0022 for 1.25B, 2.5B and 5B; for CFZ and BDQ combinations = 0.0022 for all combinations. Abbreviations: B, bedaquiline; C, clofazimine; DMSO, dimethylsulphoxide; NDM, no DMSO; Na+,K+-ATPase, sodium, potassium-adenosine triphosphatase; RCMs, rat cardiomyocytes.

Figure 1.

The Na+,K+-ATPase activities (µmol Pi/mg prot/hour) of the RCMs treated with varying concentrations of a) CFZ and b) BDQ alone and c) in combination. Statistical significance, representing p ≤ 0.05, is shown by *. The P value representing statistical difference between NDM and DMSO antibiotic-free controls is denoted by #. The p value determined between the NDM and DMSO-treated controls was 0.0087. For the antibiotic treatment assays the p values were: for CFZ = 0.24, 0.0043 and 0.0087 for 1.25C, 2.5C and 5C; for BDQ = > 0.99, 0.0152 and 0.0022 for 1.25B, 2.5B and 5B; for CFZ and BDQ combinations = 0.0022 for all combinations. Abbreviations: B, bedaquiline; C, clofazimine; DMSO, dimethylsulphoxide; NDM, no DMSO; Na+,K+-ATPase, sodium, potassium-adenosine triphosphatase; RCMs, rat cardiomyocytes.

Figure 2.

Intracellular ATP concentrations in the RCMs treated with various concentrations of a) CFZ and b) BDQ alone and c) in combination. Statistical significance, representing p ≤ 0.05, is shown by *. The p value representing the statistical difference between NDM and DMSO antibiotic-free controls is denoted by #. The P value determined for a statistically significant difference the between the NDM and DMSO-treated controls was 0.0102. For the antibiotic treatment assays these p values were: for CFZ = 0.0101, 0.0161and 0.0022* for 1.25C, 2.5C and 5C; for BDQ = 0.0065, 0.0241 and 0.0125 for 1.25B, 2.5B and 5B; for CFZ and BDQ combinations = 0.0022, 0.0299 and 0.292 for 1.25C + 1.25B, 2.5C + 2.5B and 5C + 5B, combinations, respectively. Abbreviations: ATP, adenosine triphosphate; B, bedaquiline; C, clofazimine; DMSO, dimethylsulphoxide; NDM, no DMSO.

Figure 2.

Intracellular ATP concentrations in the RCMs treated with various concentrations of a) CFZ and b) BDQ alone and c) in combination. Statistical significance, representing p ≤ 0.05, is shown by *. The p value representing the statistical difference between NDM and DMSO antibiotic-free controls is denoted by #. The P value determined for a statistically significant difference the between the NDM and DMSO-treated controls was 0.0102. For the antibiotic treatment assays these p values were: for CFZ = 0.0101, 0.0161and 0.0022* for 1.25C, 2.5C and 5C; for BDQ = 0.0065, 0.0241 and 0.0125 for 1.25B, 2.5B and 5B; for CFZ and BDQ combinations = 0.0022, 0.0299 and 0.292 for 1.25C + 1.25B, 2.5C + 2.5B and 5C + 5B, combinations, respectively. Abbreviations: ATP, adenosine triphosphate; B, bedaquiline; C, clofazimine; DMSO, dimethylsulphoxide; NDM, no DMSO.

Figure 3.

Viability determinations of the RCMs treated with various concentrations of a) CFZ and b) BDQ alone and c) in combination. Statistical significance, representing p ≤ 0.05, is shown by *. No statistical difference was shown between the DMSO treated controls and the antibiotic treated assays. Abbreviations: B, bedaquiline; BDQ, bedaquiline; C, clofazimine; CFZ, clofazimine; DMSO, dimethylsulphoxide; NDM, no DMSO.

Figure 3.

Viability determinations of the RCMs treated with various concentrations of a) CFZ and b) BDQ alone and c) in combination. Statistical significance, representing p ≤ 0.05, is shown by *. No statistical difference was shown between the DMSO treated controls and the antibiotic treated assays. Abbreviations: B, bedaquiline; BDQ, bedaquiline; C, clofazimine; CFZ, clofazimine; DMSO, dimethylsulphoxide; NDM, no DMSO.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).