Submitted:

13 September 2024

Posted:

14 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Definition and Causes of IR

3. Diagnosis

4. Effects of Hyperinsulinemia Associated with Insulin Resistance

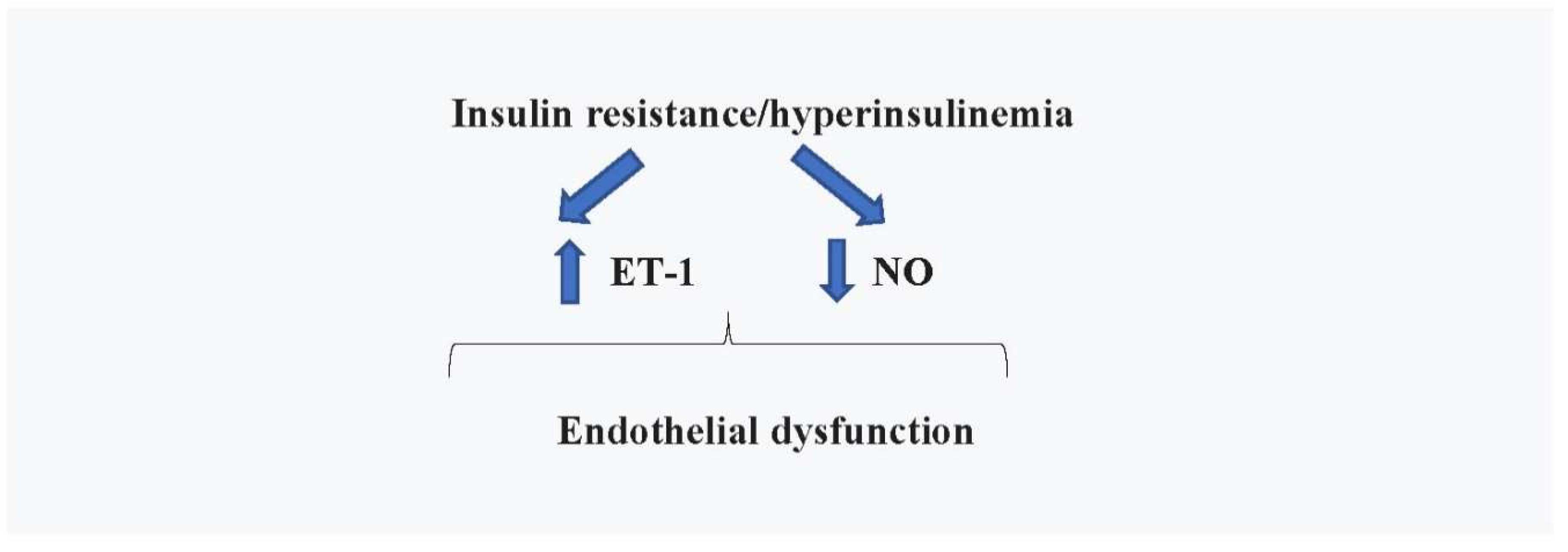

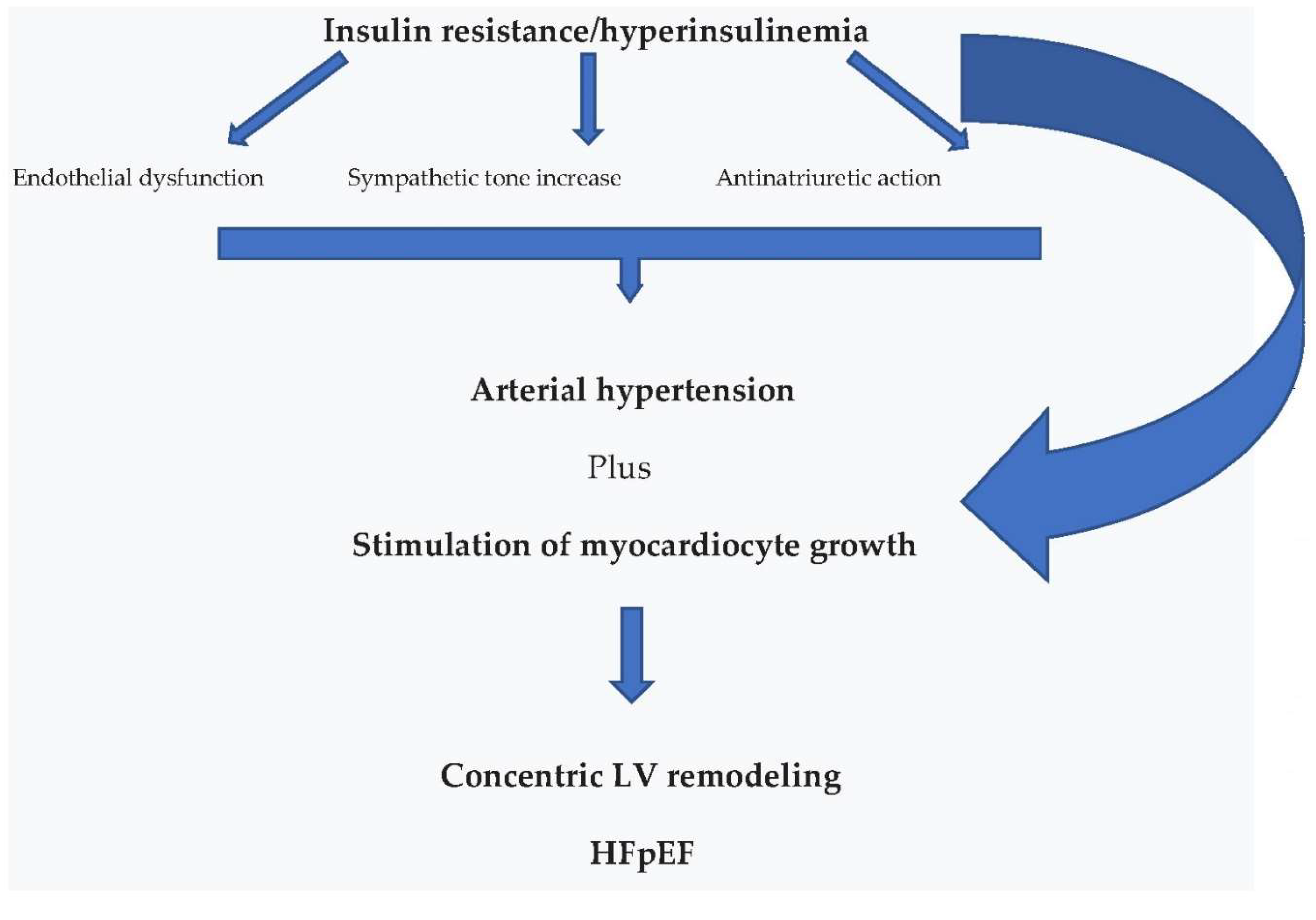

4.1. Cardiovascular Effects

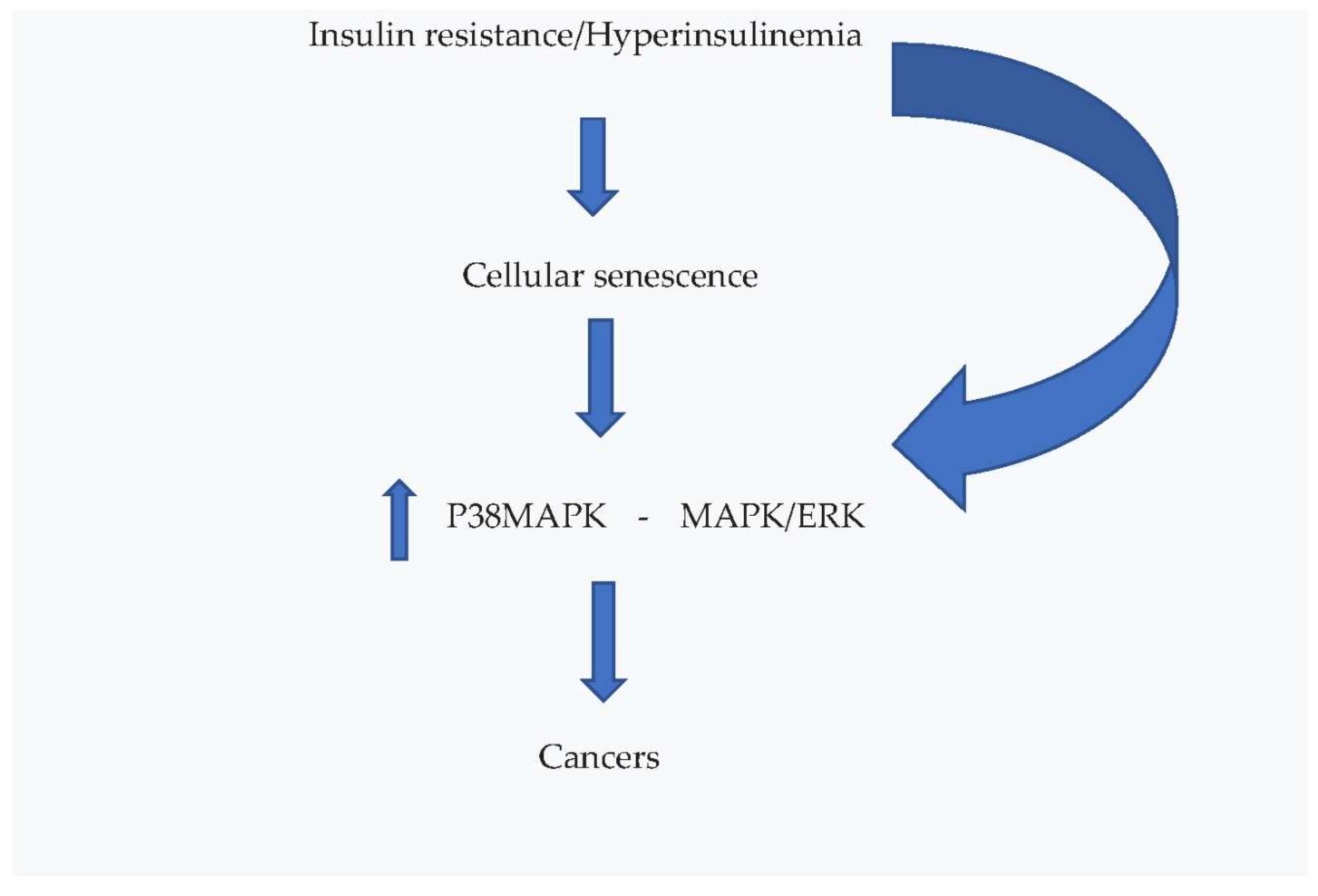

4.2. Effects on Cellular Senescence and Cancer

4.3. Effects on Brain

4.4. Possibilities of Treatment

4.5. Drugs

4.6. Natural Substances

5. Conclusions

References

- World Health Organization. The Top Ten Causes of Death. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Bermudez, V.; Salazar, J.; Martínez, M.S. ; Chávez-Castillo, M, Olivar, L.C.; Calvo, M.J.; Palmar, J.; Bautista, J.; Ramos, E.; Cabrera, M.; Pachano, F.; Rojas, J. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Insulin Resistance in Adults from Maracaibo City, Venezuela. Adv Prev Med. 2016;2016:9405105. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Freeman, A.M.; Pennings, N. Insulin Resistance. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Belfiore, A.; Malaguarnera, R.; Vella, V.; Lawrence, M.C.; Sciacca, L.; Frasca, F.; Morrione, A.; Vigneri, R. Insulin Receptor Isoforms in Physiology and Disease: An Updated View. Endocr Rev. 2017 Oct 1;38(5):379-431. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- NIH National Library of Medicine. Medline Plus, Trusted Health Information for you. Type A Insulin Resistance Syndrome. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/download/genetics/condition/type-a-insulin-resistance-syndrome.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Schernthaner-Reiter, M.H.; Wolf, P.; Vila, G.; Luger, A. The Interaction of Insulin and Pituitary Hormone Syndromes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021 Apr 28;12:626427. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- So, A.; Sakaguchi, K.; Okada, Y.; Morita, Y.; Yamada, T.; Miura, H.; Otowa-Suematsu, N.; Nakamura, T.; Komada, H.; Hirota, Y.; Tamori; Ogawa, W. Relation between HOMA-IR and insulin sensitivity index determined by hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp analysis during treatment with a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor. Endocr J. 2020 ;67(5):501-507. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Rodríguez-Morán, M.; Guerrero-Romero, F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2008 Dec;6(4):299-304. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azarpazhooh, M.R.; Najafi, F.; Darbandi, M.; Kiarasi, S.; Oduyemi, T.; Spence, J.D. Triglyceride/High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Ratio: A Clue to Metabolic Syndrome, Insulin Resistance, and Severe Atherosclerosis. Lipids. 2021 Jul;56(4):405-412. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M.A.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Z.; Jia, G.; Parrish, A.R.; Sowers, J.R. Insulin resistance, cardiovascular stiffening and cardiovascular disease. Metabolism. 2021 Jun;119:154766. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Ning, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, Z. Excess exposure to insulin is the primary cause of insulin resistance and its associated atherosclerosis. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2011 Nov;4(3):154-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landsberg, L. Insulin and the sympathetic nervous system in the pathophysiology of hypertension. Blood Press Suppl. (1996) 1:25–9.

- Brosolo, G.; Da Porto, A.; Bulfone, L.; Vacca, A.; Bertin, N.; Scandolin, L.; Catena, C.; Sechi, L.A. Insulin Resistance and High Blood Pressure: Mechanistic Insight on the Role of the Kidney. Biomedicines. 2022 Sep 23;10(10):2374. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kianu Phanzu, B.; Nkodila Natuhoyila, A.; Kintoki Vita, E.; M'Buyamba Kabangu, J.R.; Longo-Mbenza, B. Association between insulin resistance and left ventricular hypertrophy in asymptomatic, Black, sub-Saharan African, hypertensive patients: a case-control study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021 Jan 2;21(1):1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ohya, Y.; Abe, I.; Fujii, K.; Ohmori, S.; Onaka, U.; Kobayashi, K.; Fujishima, M. Hyperinsulinemia and left ventricular geometry in a work-site population in Japan. Hypertension. 1996 Mar;27(3 Pt 2):729-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Affuso, F.; Ruvolo, A.; Micillo, F.; Saccà, L.; Fazio, S. Effects of a nutraceutical combination (berberine, red yeast rice and policosanols) on lipid levels and endothelial function randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010 Nov;20(9):656-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucente, C. UPO Aging Project, Università del Piemonte Orientale. La teoria della senescenza cellulare. Dic 3, 2021. https://www.agingproject.uniupo.it/per-i-professionisti/teorie-invecchiamento/teoria-senescenza-cellulare/; accessed on , 2024. 11 July.

- Spinelli, R.; Baboota, R.K.; Gogg, S.; Beguinot, F.; Blüher, M.; Nerstedt, A.; Smith, U. Increased cell senescence in human metabolic disorders. J Clin Invest. 2023 Jun 15;133(12):e169922. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, J.A.M.J.L. Hyperinsulinemia and Its Pivotal Role in Aging, Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jul 21;22(15):7797. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baboota, R.K. ; Spinelli. R.; Erlandsson, M.C.; Brandao, B.B.; Lino, M.; Yang, H.; Mardinoglu, A.; Bokarewa, M.I.; Boucher, J.; Kahn, C.R.; Smith, U. Chronic hyperinsulinemia promotes human hepatocyte senescence. Mol Metab. 2022 Oct;64:101558. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcinotto, A.; Kohli, J.; Zagato, E.; Pellegrini, L.; Demaria, M.; Alimonti, A. Cellular Senescence: Aging, Cancer, and Injury. Physiol Rev. 2019 Apr 1;99(2):1047-1078. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campisi, J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:685-705. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, C.A.; Wang, B.; Demaria, M. Senescence and cancer - role and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022 Oct;19(10):619-636. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alimirah, F.; Pulido, T.; Valdovinos, A.; Alptekin, S. ; Chang E, Jones, E.; Diaz, D.A.; Flores, J.; Velarde, M.C.; Demaria, M.; Davalos, A.R.; Wiley, C.D.; Limba, C.; Desprez, P.Y.; Campisi, J. Cellular Senescence Promotes Skin Carcinogenesis through p38MAPK and p44/42MAPK Signaling. Cancer Res. 2020 Sep 1;80(17):3606-3619. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiefari, E.; Mirabelli, M.; La Vignera, S.; Tanyolaç, S.; Foti, D.P.; Aversa, A.; Brunetti, A. Insulin Resistance and Cancer: In Search for a Causal Link. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Oct 15;22(20):11137. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, M.C.; McKern, N.M.; Ward, C.W. Insulin receptor structure and its implications for the IGF-1 receptor. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007 Dec;17(6):699-705. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, D.H.; LeRoith, D. Obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cancer: The insulin and IGF connection. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2012, 19, F27–F45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Cho, S.I.; Park, H.S. Metabolic syndrome and cancer-related mortality among Korean men and women. Ann Oncol. 2010 Mar;21(3):640-645. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujimoto, T.; Kajio, H.; Sugiyama, T. Association between hyperinsulinemia and increased risk of cancer death in nonobese and obese people: A population-based observational study. Int J Cancer. 2017 Jul 1;141(1):102-111. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, H.M.; Shi, M.; Cheng, A.; Gao, Y.; Chen, G.; Song, X.; So, R.W.L.; Zhang, J.; Herrup, K. Age-related hyperinsulinemia leads to insulin resistance in neurons and cell-cycle-induced senescence. Nat Neurosci. 2019 Nov;22(11):1806-1819. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sędzikowska, A.; Szablewski, L. Insulin and Insulin Resistance in Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Sep 15;22(18):9987. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Cai, W.; Hoover, B.; Kahn, C.R. Insulin action in the brain: cell types, circuits, and diseases. Trends Neurosci. 2022 May;45(5):384-400. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Agrawal, R.; Reno, C.M.; Sharma, S.; Christensen, C.; Huang, Y.; Fisher, S.J. Insulin action in the brain regulates both central and peripheral functions. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Jul 1;321(1):E156-E163. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinridders, A.; Ferris, H.A.; Cai, W.; Kahn, C.R. Insulin action in brain regulates systemic metabolism and brain function. Diabetes. 2014 Jul;63(7):2232-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodner, C.J.; Hom, F.G.; Berrie, M.A. Investigation of the effect of insulin upon regional brain glucose metabolism in the rat in vivo. Endocrinology. 1980 Dec;107(6):1827-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Heide, L.P.; Kamal, A.; Artola, A.; Gispen, W.H.; Ramakers, G.M. Insulin modulates hippocampal activity-dependent synaptic plasticity in a N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor and phosphatidyl-inositol-3-kinase-dependent manner. J Neurochem. 2005 Aug;94(4):1158-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, R.; Haeri, A.; Dargahi, L.; Mohamed, Z.; Ahmadiani, A. Insulin in the brain: sources, localization and functions. Mol Neurobiol. 2013 Feb;47(1):145-71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Di Domenico, F.; Barone, E. Elevated risk of type 2 diabetes for development of Alzheimer disease: a key role for oxidative stress in brain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014 Sep;1842(9):1693-706. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janson, J.; Laedtke, T.; Parisi, J.E.; O'Brien, P.; Petersen, R.C.; Butler, P.C. Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes. 2004 Feb;53(2):474-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Monte, S.M. The Full Spectrum of Alzheimer's Disease Is Rooted in Metabolic Derangements That Drive Type 3 Diabetes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1128:45-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot, K.; Wang, H.Y.; Kazi, H.; Han, L.Y. ; Bakshi. K.P.; Stucky, A.; Fuino, R.L.; Kawaguchi, K.R.; Samoyedny, A.J.; Wilson, R.S.; Arvanitakis, Z.; Schneider, J.A.; Wolf, B.A.; Bennett, D.A.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Arnold, S.E. Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer's disease patients is associated with IGF-1 resistance, IRS-1 dysregulation, and cognitive decline. J Clin Invest. 2012 Apr;122(4):1316-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tramutola, A.; Lanzillotta, C.; Di Domenico, F.; Head, E.; Butterfield, D.A.; Perluigi, M.; Barone, E. Brain insulin resistance triggers early onset Alzheimer disease in Down syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. 2020 Apr;137:104772. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanagh, K.; Day, S.M.; Pait, M.C.; Mortiz, W.R.; Newgard, C.B.; Ilkayeva, O.; Mcclain, D.A.; Macauley, S.L. Type-2-Diabetes Alters CSF but Not Plasma Metabolomic and AD Risk Profiles in Vervet Monkeys. Front Neurosci. 2019 Aug 28;13:843. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, R.; Kravos, N.A.; Jensterle, M.; Janež, A.; Dolžan, V. Metformin and Insulin Resistance: A Review of the Underlying Mechanisms behind Changes in GLUT4-Mediated Glucose Transport. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jan 23;23(3):1264. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannarelli, R.; Aragona, M.; Coppelli, A.; Del Prato, S. Reducing insulin resistance with metformin: the evidence today. Diabetes Metab. 2003 Sep;29(4 Pt 2):6S28-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Z.; Guo, Y. Metformin and Its Benefits for Various Diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020 Apr 16;11:191. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.M.; Bellman, S.M.; Stephenson, M.D.; Lisy, K. Metformin reduces all-cause mortality and diseases of ageing independent of its effect on diabetes control: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2017 Nov;40:31-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halabi, A.; Sen, J.; Huynh, Q.; Marwick, T.H. Metformin treatment in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020 Aug 5;19(1):124. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvatore, T.; Galiero, R.; Caturano, A.; Vetrano, E.; Rinaldi, L.; Coviello, F.; Di Martino, A.; Albanese, G.; Marfella, R.; Sardu, C.; Sasso, F.C. Effects of Metformin in Heart Failure: From Pathophysiological Rationale to Clinical Evidence. Biomolecules. 2021 Dec 4;11(12):1834. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, A.M.; Sabry, N.; Farid, S. Effect of metformin on left ventricular mass and functional parameters in non-diabetic patients: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022 Sep 10;22(1):405. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelsey, M.D.; Nelson, A.J.; Green, J.B.; Granger, C.B. ; Peterson. E.D.; McGuire, D.K.; Pagidipati, N.J. Guidelines for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: JACC Guideline Comparison. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 ;79(18):1849-1857. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, J.; Usman, M.S.; Khan, M.S.; Greene, S.J.; Friede, T.; Vaduganathan, M.; Filippatos, G.; Coats, A.J.S.; Anker, S.D. Efficacy and safety of SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. ESC Heart Fail. 2020 Dec;7(6):3298-3309. Erratum in: ESC Heart Fail. 2021 Jun;8(3):2362. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13338. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Claggett, B.; de Boer, R.A.; DeMets, D. ; Hernandez,A.F.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.S.P.;Martinez, F. et al. DELIVER Trial Committees and Investigators. Dapagliflozin in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2022 Sep 22;387(12):1089-1098. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverii, G.A.; Monami, M.; Mannucci, E. Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021 Apr;23(4):1052-1056. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabel, S.; Hamdani, N.; Luedde, M.; Sossalla, S. SGLT2 Inhibitors and Their Mode of Action in Heart Failure-Has the Mystery Been Unravelled? Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2021 Oct;18(5):315-328. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosokawa, Y.; Ogawa, W. SGLT2 inhibitors for genetic and acquired insulin resistance: Considerations for clinical use. J Diabetes Investig. 2020 Nov;11(6):1431-1433. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarz, K.; Kowalczyk, K.; Cwynar, M.; Czapla, D.; Czarkowski, W.; Kmita, D.; Nowak, A.; Madej, P. The Role of Glp-1 Receptor Agonists in Insulin Resistance with Concomitant Obesity Treatment in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Apr 14;23(8):4334. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, B.; Fan, L.; Yi, N.; Lu, B.; Wang, Q.; Liu, R. GLP-1 Improves Adipocyte Insulin Sensitivity Following Induction of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Front Pharmacol. 2018 Oct 16;9:1168. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, J.P.; Saraiva, F.; Sharma, A.; Vasques-Nóvoa, F.; Angélico-Gonçalves, A.; Leite, A.R.; Borges-Canha, M.; Carvalho, D.; Packer, M.; Zannad, F.; Leite-Moreira, A.; Neves, J.S. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes with and without chronic heart failure: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled outcome trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023 Jun;25(6):1495-1502. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merza, N.; Akram, M.; Mengal, A.; Rashid, A.M.; Mahboob, A.; Faryad, M.; Fatima, Z.; Ahmed, M.; Ansari, S.A. The Safety and Efficacy of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Heart Failure Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023 May;48(5):101602. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodhi, M.; Rezaeianzadeh, R.; Kezouh, A.; Etminan, M. Risk of Gastrointestinal Adverse Events Associated With Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists for Weight Loss. JAMA. 2023 Nov 14;330(18):1795-1797. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European medicines agency. Science Medicines Health. EMA Statement on Ongoing Review of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists. News 11/07/2023 (2023). Available online at: news">https://www.ema.europa.eu>news (accessed March 7, 2024).

- Carlomagno, G.; Pirozzi, C.; Mercurio, V.; Ruvolo, A.; Fazio, S. Effects of a nutraceutical combination on left ventricular remodeling and vasoreactivity in subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2012 May;22(5):e13-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercurio, V.; Pucci, G.; Bosso, G.; Fazio, V.; Battista, F.; Iannuzzi, A.; Brambilla, N.; Vitalini, C.; D'Amato, M.; Giacovelli, G.; et al. A nutraceutical combination reduces left ventricular mass in subjects with metabolic syndrome and left ventricular hypertrophy: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2020 May;39(5):1379-1384. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.H.; Zeng, X.J.; Li, Y.Y. Efficacy and safety of berberine for congestive heart failure secondary to ischemic or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2003 Jul 15;92(2):173-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Gao, Y.; Yu, S.; Sun, X.; Shen, K. Berberine attenuates Aβ42-induced neuronal damage through regulating circHDAC9/miR-142-5p axis in human neuronal cells. Life Sci. 2020 Jul 1;252:117637. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durairajan, S.S.; Liu, L.F.; Lu, J.H.; Chen, L.L.; Yuan, Q.; Chung, S.K.; Huang, L.; Li, X.S.; Huang, J.D.; Li, M. Berberine ameliorates β-amyloid pathology, gliosis, and cognitive impairment in an Alzheimer's disease transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol Aging. 2012 Dec;33(12):2903-19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Dong, S.; Chen, W.; Li, J.; Luo, E.; Ji, J. Berberine alleviates Alzheimer's disease by regulating the gut microenvironment, restoring the gut barrier and brain-gut axis balance. Phytomedicine. 2024 Jul;129:155624. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, C.; Killick, R.; Lovestone, S. The GSK3 hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2008 Mar;104(6):1433-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellavite, P.; Fazio, S.; Affuso, F. A Descriptive Review of the Action Mechanisms of Berberine, Quercetin and Silymarin on Insulin Resistance/Hyperinsulinemia and Cardiovascular Prevention. Molecules. 2023 Jun 1;28(11):4491. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabirifar, R.; Ghoreshi, Z.A.; Safari, F.; Karimollah, A.; Moradi, A.; Eskandari-Nasab, E. Quercetin protects liver injury induced by bile duct ligation via attenuation of Rac1 and NADPH oxidase1 expression in rats. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2017 Feb;16(1):88-95. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodarahmi, A.; Eshaghian, A.; Safari, F.; Moradi, A. Quercetin Mitigates Hepatic Insulin Resistance in Rats with Bile Duct Ligation Through Modulation of the STAT3/SOCS3/IRS1 Signaling Pathway. J Food Sci. 2019 Oct;84(10):3045-3053. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhai, D.; Zhang, D.; Bai, L.; Yao, R.; Yu, J.; Cheng, W.; Yu, C. Quercetin Decreases Insulin Resistance in a Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Rat Model by Improving Inflammatory Microenvironment. Reprod Sci. 2017 May;24(5):682-690. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorbenko, N.I.; Borikov, O.Y.; Kiprych, T.V.; Ivanova, O.V.; Taran, K.V.; Litvinova, T.S. Quercetin improves myocardial redox status in rats with type 2 diabetes. Endocr Regul. 2021 Sep 13;55(3):142-152. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang,P.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, B.; Shen, X.; Zhang, Z.J.; Qin, D.L.; Tian, J. Quercetin-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside Isolated from Eucommia ulmoides Leaf Relieves Insulin Resistance in HepG2 Cells via the IRS-1/PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β Pathway. Biol Pharm Bull. 2023 Feb 1;46(2):219-229. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.D.; Zhang, D.Y.; Gao, X.J.; Parry, J.; Liu, K.; Liu, B.L.; Wang, M. Quercetin and quercetin-3-O-glucuronide are equally effective in ameliorating endothelial insulin resistance through inhibition of reactive oxygen species-associated inflammation. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013 Jun;57(6):1037-45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald-Ramos, K.; Michán, L.; Martínez-Ibarra, A.; Cerbón, M. Silymarin is an ally against insulin resistance: A review. Ann Hepatol. 2021 Jul-Aug;23:100255. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, T. Silymarin improved diet-induced liver damage and insulin resistance by decreasing inflammation in mice. Pharm Biol. 2016 Dec;54(12):2995-3000. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, B.; Huang, B.; Jing, Y.; Shen, S.; Feng, W.; Wang, W.; Meng, R.; Zhu, D. Silymarin ameliorates the disordered glucose metabolism of mice with diet-induced obesity by activating the hepatic SIRT1 pathway. Cell Signal. 2021 Aug;84:110023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.; Shao, J. SIRT1 regulates adiponectin gene expression through Foxo1-C/enhancer-binding protein alpha transcriptional complex. J Biol Chem. 2006 Dec 29;281(52):39915-24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgarf, A.T.; Mahdy, M.M.; Ali Sabri, N. Effect of Silymarin Supplementation on Glycemic Control, Lipid Profile and Insulin Resistance in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2015;3:812–821.

- Ebrahimpour-Koujan, S.; Gargari, B.P.; Mobasseri, M.; Valizadeh, H.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M. Lower glycemic indices and lipid profile among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients who received novel dose of Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. (silymarin) extract supplement: A Triple-blinded randomized controlled clinical trial. Phytomedicine. 2018 ;44:39-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memon, A.; Siddiqui, S.S.; Ata, M.A.; Shaikh, K.R.; Soomro, U.A.; Shaikh, S. Silymarin improves glycemic control through reduction of insulin resistance in newly diagnosed patients of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Professional Med J 2022; 29(3):362-366. [CrossRef]

- Ravari, S.S.; Talaei, B.; Gharib, Z. The effects of silymarin on type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Med. 2021;26:100368.

- Xiao, F.; Gao, F.; Zhou, S.; Wang, L. The therapeutic effects of silymarin for patients with glucose/lipid metabolic dysfunction: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Oct 2;99(40):e22249. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirhadi, E.; Rezaee, M.; Malaekeh-Nikouei, B. Nano strategies for berberine delivery, a natural alkaloid of Berberis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018 Aug;104:465-473. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piatti, P.M.; Monti, L.D.; Valsecchi, G.; Magni, F.; Setola, E.; Marchesi, F.; Galli-Kienle, M.; Pozza, G.; Alberti, K.G. Long-term oral L-arginine administration improves peripheral and hepatic insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2001 May;24(5):875-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, A.X.; Aylor, K.; Barrett, E.J. Nitric oxide directly promotes vascular endothelial insulin transport. Diabetes. 2013 Dec;62(12):4030-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miczke, A.; Suliburska, J.; Pupek-Musialik, D.; Ostrowska, L.; Jabłecka, A.; Krejpcio, Z.; Skrypnik, D.; Bogdański, P. Effect of L-arginine supplementation on insulin resistance and serum adiponectin concentration in rats with fat diet. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015 Jul 15;8(7):10358-66. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lucotti, P.; Setola, E.; Monti, L.D.; Galluccio, E.; Costa, S.; Sandoli, E.P.; Fermo, I.; Rabaiotti, G.; Gatti, R.; Piatti, P. Beneficial effects of a long-term oral L-arginine treatment added to a hypocaloric diet and exercise training program in obese, insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Nov;291(5):E906-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonscher, K.R.; Chowanadisai, W.; Rucker, R.B. Pyrroloquinoline-Quinone Is More Than an Antioxidant: A Vitamin-like Accessory Factor Important in Health and Disease Prevention. Biomolecules. 2021 Sep.

- Grahame Hardie, D. AMP-activated protein kinase: a key regulator of energy balance with many roles in human disease. J Intern Med. 2014 Dec;276(6):543-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akagawa, M.; Nakano, M.; Ikemoto, K. Recent progress in studies on the health benefits of pyrroloquinoline quinone. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2016;80(1):13-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercurio, V.; Carlomagno, G.; Fazio, V.; Fazio, S. Insulin resistance: Is it time for primary prevention? World J Cardiol. 2012 Jan 26;4(1):1-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).